Abstract

Objective

To investigate recent respiratory and influenza-like illnesses (ILIs) in acute myocardial infarction patients compared with patients hospitalised for acute non-vascular surgical conditions during the second wave of the 2009 influenza A H1N1 pandemic.

Design

Case–control study.

Setting

Coronary care unit, acute cardiology and acute surgical admission wards in a major teaching hospital in London, UK.

Participants

134 participants (70 cases and 64 controls) aged ≥40 years hospitalised for acute myocardial infarction and acute surgical conditions between 21 September 2009 and 28 February 2010, frequency-matched for gender, 5-year age-band and admission week.

Primary exposure

ILI (defined as feeling feverish with either a cough or sore throat) within the last month.

Secondary exposures

Acute respiratory illness within the last month not meeting ILI criteria; nasopharyngeal and throat swab positive for influenza virus.

Results

29 of 134 (21.6%) participants reported respiratory illness within the last month, of whom 13 (9.7%) had illnesses meeting ILI criteria. The most frequently reported category for timing of respiratory symptom onset was 8–14 days before admission (31% of illnesses). Cases were more likely than controls to report ILI—adjusted OR 3.17 (95% CI 0.61 to 16.47)—as well as other key respiratory symptoms, and were less likely to have received influenza vaccination—adjusted OR 0.46 (95% CI 0.19 to 1.12)—although the differences were not statistically significant. No swabs were positive for influenza virus.

Conclusions

Point estimates suggested that recent ILI was more common in patients hospitalised with acute myocardial infarction than with acute surgical conditions during the second wave of the influenza A H1N1 pandemic, and influenza vaccination was associated with cardioprotection, although the findings were not statistically significant. The study was underpowered, partly because the age groups typically affected by acute myocardial infarction had low rates of infection with the pandemic influenza strain compared with seasonal influenza.

Keywords: Public health

Article summary.

Article focus

Seasonal influenza can trigger cardiovascular complications, but the cardiac effects of the 2009 influenza pandemic are less clear.

We aimed to investigate recent influenza-like illness (ILI) in patients hospitalised with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and surgical conditions during the 2009 influenza pandemic in London.

Key messages

In total, 14.3% of patients hospitalised with AMI (cases) reported recent ILI compared with 4.7% of patients hospitalised for acute surgical conditions (controls).

Cases were more likely than controls to report a range of recent respiratory symptoms and less likely to have received influenza vaccination, although the differences were not statistically significant.

The median age of cases with AMI was 63.6 years, whereas the majority of people infected with pandemic influenza strain nationally were young.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study was underpowered to detect an effect, partly due to low infection rates with the pandemic influenza virus in age-groups typically affected by AMI, but it will inform the design of future similar studies.

Introduction

Seasonal influenza can trigger cardiovascular complications and deaths in vulnerable populations, especially the elderly and those with underlying medical conditions.1 Evidence to support the hypothesis that seasonal influenza may trigger acute myocardial infarction (AMI) comes from a range of observational studies incorporating the effects of different circulating influenza strains and subtypes.2 In a pandemic situation, however, when there is global spread of a novel influenza strain, the clinical and demographic profiles of those affected may change dramatically.

The most recent influenza pandemic was caused by an influenza A H1N1 strain (H1N1pdm09) that emerged in Mexico and the USA in April 2009.3 4 The UK experienced several waves of infection with this novel strain—a first wave occurred in spring and summer 2009 followed by a second wave in the winter of 2009/2010 and a postpandemic wave in winter 2010/2011.5 Initial evidence from the first wave in the UK suggested that typical illnesses were mild and affected mainly children and young people.6 The average age of cases increased over subsequent waves of the pandemic,7 but it is unclear how this affected clinical illness profiles. Vaccination coverage did not reach high levels until the postpandemic season.

There have been reports of myocarditis, myocardial injury and left-ventricular systolic dysfunction, which may be reversible, in patients with severe H1N1pdm09.8 9 It has been suggested that H1N1pdm09 was associated with higher rates of extrapulmonary complications than seasonal influenza,10 but this is difficult to compare as surveillance of severe influenza-related disease was greatly enhanced during the pandemic. A recent mathematical modelling study estimated that globally there were 83 300 cardiovascular deaths associated with the first 12 months of H1N1pdm09 circulation in adults aged >17 years,11 but the contribution of myocardial infarction deaths to this figure is unknown.

In this study, we aimed to investigate whether patients hospitalised for AMI during the winter wave of the influenza A H1N1 pandemic were more likely than surgical patients to have experienced recent influenza-like illness (ILI) or acute respiratory illness, or to have concurrent PCR positive influenza or evidence of influenza A IgA antibodies in sera.

Methods

Setting, design and participants

This was an observational case–control study carried out in hospital inpatients at the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust between 21 September 2009 and 28 February 2010. Cases were patients aged ≥40 years who had experienced an AMI (defined as a rise in troponin T with ischaemic symptoms and/or typical ECG changes, or by angiographic evidence of acute coronary artery thrombosis during primary percutaneous coronary intervention). Controls were patients aged ≥40 years admitted with an acute surgical condition such as appendicitis, bowel or urinary obstruction and no history of myocardial infarction within the past month. These patients were chosen as controls because their admissions were considered unlikely to be influenced by recent ILI. Cases and controls were frequency matched for gender, age-group in 5-year age-bands and week of admission. All were English-speaking and able to provide written informed consent. The study size was based on numbers of eligible patients hospitalised during the influenza circulation period.

Exposures

The main exposure was recent ILI, defined as a history of feeling feverish with either a cough or sore throat within the last month. We also used the exposure recent acute respiratory infection to capture a history of respiratory illness within the last month with any of the following symptoms—fever, chills, dry cough, productive cough, myalgia, rhinorrhoea, blocked nose, sore throat, wheeze, earache and fatigue—that did not meet the criteria for ILI. Additional exposures were nasopharyngeal and throat swabs testing positive for influenza by real-time PCR, the presence of IgA antibodies to influenza A in serum samples and self-reported influenza vaccination status.

Data sources and measurement

We used a questionnaire to investigate recent respiratory and ILI as well as to capture data on demographics, medical history and influenza vaccination status. Information on influenza vaccination status was collected as ‘vaccinated this year (from September 2009)’, ‘vaccinated last year (September 2008—August 2009)’, ‘vaccinated 2–5 years ago’, ‘vaccinated >5 years ago’ and ‘never vaccinated’. Vaccination status was then recategorised as a binary variable comprising ‘vaccinated this year’ and ‘unvaccinated’, which included all other categories, to recognise that vaccinations in previous seasons would not protect against the new circulating pandemic influenza strain. Medical records were reviewed for details of the current admission and to confirm data on potential confounding factors. Combined nasopharyngeal and throat swabs were taken from each participant, placed in viral transport medium and transported to the laboratory for storage at −80°C. Samples were tested for the presence of influenza virus RNA using a validated in-house real-time PCR with a lower limit of detection of one RNA copy per reaction, as previously described.12 A single serum sample was taken for quantification of IgA antibodies to influenza A as a marker of recent exposure (as IgA levels peak at around 2 weeks after exposure and reach the baseline by around 4–6 weeks). Serum samples were centrifuged, frozen at −80°C and batch tested using a commercially available ELISA for influenza A IgA (Biosupply UK, cat no. RE56501). Antibody concentrations were initially explored as a continuous variable, then categorised into ‘positive’ (>12 U/ml), ‘equivocal’ (8–12 U/ml) and ‘negative’ (>8 U/ml) categories based on standard laboratory thresholds. Equivocal results were dropped for analyses.

Statistical methods

All analyses were carried out using Stata (Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, Texas, USA: StataCorp LP). Baseline comparability between cases and controls was assessed with χ² tests. Characteristics of participants with and without missing data were also compared using χ² tests to assess any risk of bias associated with missing data. We used multivariable logistic regression analysis to investigate associations between recent ILI or acute respiratory illness exposures and case/control status, controlling for the frequency-matching factors age-group, gender and month of admission and influenza vaccination status as an a priori confounder (all models) as well as for other potential confounding factors. An additional multivariable model in which influenza vaccination status was the main exposure was generated using the same approach. Potential confounders were examined using a backward-stepwise approach whereby factors independently associated with both exposure and outcome were included in models and likelihood ratio tests used to assess the effect of removing each one sequentially. If p values from likelihood ratio tests were <0.1, then factors were retained in the model.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

In total, 134 participants were recruited, who comprised 70 cases from 106 approached (acceptance rate 66%) and 64 controls from 95 approached (acceptance rate 67%). Reasons for non-participation included lack of time, unwillingness to experience additional procedures and feeling tired or unwell. The median age of participants was 63.6 years (IQR 53.3–72.6), of whom 21% were women. Cases were more likely to be of Asian or Asian British ethnicity (p=0.016), to have a previous history of myocardial infarction (p=0.04) or a family history of myocardial infarction (p<0.001) than controls. Of the 70 patients hospitalised for AMI, 48 (68.5%) met criteria for ST-elevation myocardial infarction, 17 (24.3%) had a non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction and in 5 (7.1%) cases the subtype of myocardial infarction was unspecified. Control patients were admitted with a range of acute non-vascular surgical presentations that included colorectal, urological and orthopaedic conditions (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants (n=134)

| Characteristic | Category | Cases (n=70) | Controls (n=64) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||||

| 40–49 | 8 (11.4) | 13 (20.3) | 0.61 | |

| 50–59 | 19 (27.1) | 18 (28.1) | ||

| 60–69 | 19 (27.1) | 15 (23.4) | ||

| 70–79 | 17 (24.3) | 11 (17.2) | ||

| 80+ | 7 (10.0) | 7 (10.9) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 13 (18.6) | 15 (23.4) | 0.49 | |

| Male | 57 (81.4) | 49 (76.6) | ||

| Admission month | ||||

| September | 8 (11.4) | 7 (10.9) | 0.92 | |

| October | 12 (17.1) | 15 (23.4) | ||

| November | 15 (21.4) | 14 (21.9) | ||

| December | 10 (14.3) | 10 (15.6) | ||

| January | 14 (20.0) | 11 (17.2) | ||

| February | 11 (15.7) | 7 (10.9) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Asian or Asian British | 18 (25.7) | 6 (9.4) | 0.03 | |

| Black or Black British | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Mixed | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | ||

| White | 50 (71.4) | 57 (89.1) | ||

| BMI category | ||||

| 18.5–24.9 | 20 (30.8) | 23 (39.0) | 0.41 | |

| 25.0–29.9 | 36 (55.4) | 24 (40.7) | ||

| 30.0–39.9 | 8 (12.3) | 10 (17.0) | ||

| 40.0–max | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3.4) | ||

| Smoker | ||||

| No never | 22 (31.4) | 23 (35.9) | 0.77 | |

| Yes current | 27 (38.6) | 21 (32.8) | ||

| Yes ex | 21 (30.0) | 20 (31.3) | ||

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypercholesterolaemia* | 34 (48.6) | 28 (43.8) | 0.58 | |

| Diabetes | 14 (20.0) | 12 (18.8) | 0.86 | |

| Hypertension | 37 (52.9) | 26 (40.6) | 0.16 | |

| AMI | 14 (20.0) | 5 (7.8) | 0.04 | |

| Stroke | 1 (1.4) | 4 (6.3) | 0.14 | |

| Family history | ||||

| AMI | 43 (61.4) | 19 (29.7) | <0.001 | |

| Stroke | 5 (7.1) | 6 (9.4) | 0.64 | |

| Influenza vaccination status† | ||||

| Vaccinated | 30 (42.9) | 29 (45.3) | 0.78 |

*28 cases (40%) and 25 controls (39%) with hypercholesterolaemia reported current statin use.

†‘Vaccinated’ refers to receiving influenza vaccination in the current vaccination year (since September 2009).

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; BMI, body mass index.

Timing of participants’ admissions in relation to national influenza circulation

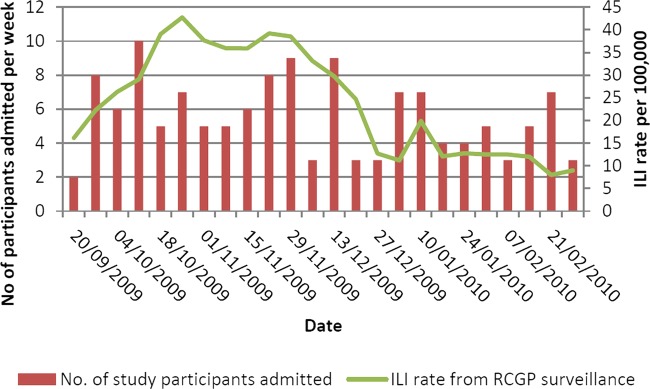

A comparison of study participants’ dates of admission with national rates of general practitioner (GP) consultations for ILI based on RCGP surveillance data is shown in figure 1. The peak week for ILI consultations in England was week 43 (ending 25 October 2009) when the rate was 42.8/100 000. This was also the peak week for influenza virus circulation according to data from virological sentinel surveillance schemes, when the proportion of positive samples reached 41.2%. Our recruitment period spanned this period of peak influenza circulation.

Figure 1.

Number of study participants admitted by influenza surveillance week compared with weekly influenza-like illness rates per 100 000 based on national RCGP surveillance data.

Recent respiratory and ILI

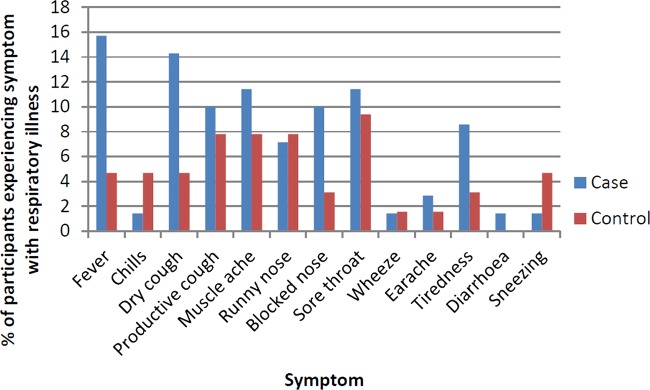

Seventeen cases (24.3%) and 12 controls (18.8%) reported respiratory illness in the month preceding hospital admission. Thirteen illnesses—reported by 10 cases (14.3%) and 3 controls (4.7%)—met criteria for ILI (defined as feeling feverish with a cough and/or sore throat). The most frequently reported category for the timing of respiratory symptom onset was 8–14 days before admission (31% of illnesses). Four to seven days were the most frequently reported category for length of illness (37.9% of illnesses). Symptom profiles of participants reporting recent respiratory illness are shown in figure 2. No swabs tested positive for influenza virus nucleic acid. Serum samples were available on 113 of 134 participants (84.3%). There were no significant differences in characteristics of participants with and without missing serum samples (data not shown). Twenty-five cases (43.1%) and 28 controls (50.9%) tested positive for serum influenza A IgA antibodies. Sixty-two per cent of participants who were seropositive had received influenza vaccination during the study period compared with 31% of seronegative participants. Overall, 44% of participants were vaccinated. The proportion of participants recruited in each month who were vaccinated increased from 0% in September 2009 to 29.6% in October 2009, 44.8% in November 2009, 55% in December 2009, 72% in January 2010 and was 50% in February 2010.

Figure 2.

Percentage of cases (n=70) and controls (n=64) reporting various symptoms during respiratory illness.

Cases were more likely to have reported ILI than controls—adjusted OR 3.17 (95% CI 0.61 to 16.47)—as well as other key respiratory illness symptoms, although differences were not statistically significant. Results from this logistic regression analysis are summarised in table 2. There was also a trend towards a protective effect of influenza vaccination against myocardial infarction—adjusted OR 0.46 (95% CI 0.19 to 1.12)—after controlling for age group, gender, month of admission and personal history of AMI.

Table 2.

ORs for the association between acute myocardial infarction and various respiratory illness exposure variables, unadjusted and adjusted

| Exposure variable | Prevalence—cases, n (%) | Prevalence—controls, n (%) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory illness | 17 (24.3) | 12 (18.8) | 1.39 (0.60 to 3.19) | 1.39 (0.56 to 3.47) |

| Influenza-like illness | 10 (14.3) | 3 (4.7) | 3.39 (0.89 to 12.92) | 3.17 (0.61 to 16.47) |

| Fever | 11 (15.7) | 4 (6.3) | 2.80 (0.84 to 9.28) | 2.42 (0.54 to 10.98) |

| Cough | 21 (30.0) | 10 (15.6) | 2.31 (0.99 to 5.40) | 2.04 (0.76 to 5.47) |

| Sore throat | 10 (14.3) | 8 (12.5) | 1.17 (0.43 to 3.17) | 1.43 (0.44 to 4.69) |

| Muscle ache | 8 (11.4) | 5 (7.8) | 1.52 (0.47 to 4.92) | 2.29 (0.59 to 8.92) |

| Influenza A IgA antibodies† | 25 (46.3) | 28 (54.9) | 0.71 (0.33 to 1.53) | 0.82 (0.34 to 2.00) |

*Adjustments were made for age-group, gender, month of admission and influenza vaccination status (all exposures), family history of myocardial infarction (exposures 2, 3, 4 and 5) and personal history of myocardial infarction (exposures 2, 3, 4 and 5).

†Note that n=105 (54 cases and 51 controls) for influenza antibodies where eight equivocal results were excluded, compared with n=134 (70 cases and 64 controls) for all other exposures.

Discussion

The study was supportive of the hypothesis that recent respiratory illnesses and, in particular, ILIs occurring during the second wave of the influenza A H1N1 pandemic were more common in patients hospitalised with AMI than with acute surgical conditions. Influenza vaccination was also associated with protection against myocardial infarction, although differences were not statistically significant. While we had hypothesised that more adults would be infected during the second pandemic wave due to the expected upward shift in age distribution of infections, the national rates of ILI remained low,5 especially in age groups typically affected by AMI. The study was therefore underpowered to detect an effect, partly due to the limited numbers of infections among participants.

Using self-reported recent respiratory illness and ILI as exposures introduced the possibility of reporting or recall bias. Nonetheless, this method allows greater sensitivity to detect recent respiratory symptoms than relying on reports of medically attended illnesses, which comprise only a small minority of influenza cases.13 As cases and controls were frequency matched in the week of admission, external factors such as media coverage of the influenza pandemic should not have had a differential effect on respiratory illness reporting. We chose to test both nasopharyngeal and throat swabs to increase the sensitivity of virus detection. It was perhaps unsurprising, however, that none of the nasopharyngeal and throat swabs were positive for influenza virus given (1) the low rates of infection in this age-group5 and (2) that the majority of viral shedding in influenza occurs in the first 2–3 days after symptom onset,14 whereas most of the reported respiratory symptoms in study participants occurred 8–14 days before admission. Based on our findings, it seems unlikely that any delayed cardiac effect of influenza is linked to ongoing or prolonged virus replication or shedding in the respiratory tract. Influenza serology is difficult to interpret in vaccinated participants as it not possible to distinguish antibody rises caused by infection from those caused by vaccination. Validation of the IgA assay used suggests that it has acceptable sensitivity and specificity to detect recent seasonal influenza A infection,15 but its effect with the pandemic strain H1N1pdm09 is unclear. It has previously been noted that serological studies carried out during the 2009 influenza pandemic were severely hampered by crossreactivity both with the vaccine and with the seasonal influenza strains.7

Previous observational studies using large electronic primary care databases have found an association between GP consultation for acute respiratory infection in the previous month and risk of AMI.16–18 Although studies were conducted over different time periods, they encompassed the effect of varying seasonal influenza strains. In the present study, we controlled for important potential confounders such as influenza vaccination status, and showed that statin use was equally prevalent in cases and controls. We did not, however, have complete data on other drugs that have been hypothesised to have immune-regulatory effects (such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, metformin, glitazones and fibrates). If these agents reduce the likelihood of people experiencing ILI, and were more commonly used in cases than controls, they could potentially have confounded the relationship between ILI and AMI. It was reassuring, however, that our results were consistent with those obtained in our recent self-controlled case series study—a design that implicitly controls for fixed confounders. In this study, we used linked primary care and cardiac disease registry records from 3927 patients from 2003–2009, which also included acute respiratory infection consultations occurring during the first wave of H1N1pdm09 circulation.19 We found an incidence ratio for AMI of 4.19 (95% CI 3.18 to 5.53) in the first 1–3 days after acute respiratory infection, with the risk falling to baseline after 28 days.19 Elderly people and those consulting for an infection judged most likely to be due to influenza were at greatest risk. During the 2009 influenza, pandemic people with underlying cardiovascular disease were much more likely to be hospitalised13 and to die20 from a range of causes attributable to pandemic influenza. Although most deaths from H1N1pdm09 occurred in younger people, this was partly a function of the age distribution of infections: in the UK, the case death rate in the elderly was much higher than in younger age-groups,5 but overall, the numbers of deaths were small as few elderly people were infected.

Various biological mechanisms are proposed to underlie a relationship between influenza or acute respiratory infection and myocardial infarction.21 Acute respiratory infections may result in a host of acute inflammatory and haemostatic effects leading to systemic inflammation, altered plasma viscosity, coagulability and haemodynamic changes22 as well as promoting local endothelial dysfunction, coronary inflammation and plaque rupture.23 Immobility associated with bedrest and dehydration might potentiate these processes.

In conclusion, this study suggests that recent ILI occurring during the 2009 influenza pandemic was more common in AMI patients. Taken in the context of previous work, this helps to support the hypothesis that, as with other influenza strains, H1N1pdm09 could potentially trigger AMI in vulnerable groups. It is likely, however, that the effect is not specific to influenza and could have also been caused by other viruses circulating at the time. The population impact of H1N1pdm09 on rates of hospitalisations and deaths from myocardial infarction is also likely to have been relatively low given the mismatch between the ages of those typically affected by H1N1pdm09 and acute coronary events as well as the relatively mild clinical effects of this influenza strain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients who agreed to participate in this study and nurses on the cardiology and surgical wards at the Royal Free Hospital who helped to identify potential participants. We acknowledge Mauli Patel at the Royal Free Virology Laboratory who kindly processed, stored and tested samples.

Footnotes

Contributors: CW-G conceived and designed the study, recruited participants, collected and analysed data and wrote the manuscript. AMG, GH, RDR, LS and ACH assisted with the study design. AMG provided laboratory resources. CW-G, AMG, RDR, LS and ACH interpreted the results. AMG, GH, RDR, LS and ACH critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. LS and ACH provided supervision. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was funded by a Medical Research Council Clinical Research Training Fellowship for CWG, grant number G0800689. LS is supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship in Clinical Science, grant number 098504/Z/12/Z.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Royal Free Hospital & Medical School Research Ethics Committee (reference number 09/H0720/91).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Cox NJ, Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet 1999;354:1277–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warren-Gash C, Smeeth L, Hayward AC. Influenza as a trigger for acute myocardial infarction or death from cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2009;9:601–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), et al. Swine influenza A (H1N1) infection in two children—Southern California, March-April 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009;58:400–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), et al. Outbreak of swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus infection—Mexico, March-April 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009;58:467–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Health Protection Agency Epidemiological report of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 in the United Kingdom: London, April 2009—May 2010, 2010

- 6.McLean E, Pebody RG, Campbell C, et al. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza in the UK: clinical and epidemiological findings from the first few hundred (FF100) cases. Epidemiol Infect 2010;138:1531–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lagacé-Wiens PRS, Rubinstein E, Gumel A. Influenza epidemiology—past, present, and future. Crit Care Med 2010;38:e1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chacko B, Peter JV, Pichamuthu K, et al. Cardiac manifestations in patients with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus infection needing intensive care. J Crit Care 2012;27:106.e1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin SS, Hollingsworth CL, Norfolk SG, et al. Reversible cardiac dysfunction associated with pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1). Chest 2010;137:1195–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee N, Chan PKS, Lui GCY, et al. Complications and outcomes of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in hospitalized adults: how do they differ from those in seasonal influenza? J Infect Dis 2011;203:1739–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawood FS, Iuliano AD, Reed C, et al. Estimated global mortality associated with the first 12 months of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus circulation: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:687–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khanom AB, Velvin C, Hawrami K, et al. Performance of a nurse-led paediatric point of care service for respiratory syncytial virus testing in secondary care. J Infect 2011;62:52–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell CNJ, Mytton OT, McLean EM, et al. Hospitalization in two waves of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in England. Epidemiol Infect 2010;139:1560–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau LLH, Cowling BJ, Fang VJ, et al. Viral shedding and clinical illness in naturally acquired influenza virus infections. J Infect Dis 2010;201:1509–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothbarth PH, Groen J, Bohnen AM, et al. J Virol Methods 78:163–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smeeth L, Thomas SL, Hall AJ, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2611–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clayton TC, Thompson M, Meade TW. Recent respiratory infection and risk of cardiovascular disease: case-control study through a general practice database. Eur Heart J 2008;29:96–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meier CR, Jick SS, Derby LE, et al. Acute respiratory-tract infections and risk of first-time acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 1998;351:1467–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warren-Gash C, Hayward AC, Hemingway H, et al. Influenza infection and risk of acute myocardial infarction in England and Wales: a CALIBER self-controlled case series study. J Infect Dis 2012;206:1652–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mytton OT, Rutter PD, Mak M, et al. Mortality due to pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza in England: a comparison of the first and second waves. Epidemiol Infect 2012;140:1533–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bazaz R, Marriott HM, Francis SE, et al. Mechanistic links between acute respiratory tract infections and acute coronary syndromes. J Infect 2013;66:1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harskamp RE, Van Ginkel MW. Acute respiratory tract infections: a potential trigger for the acute coronary syndrome. Ann Med 2008;40:121–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vallance P, Collier J, Bhagat K. Infection, inflammation, and infarction: does acute endothelial dysfunction provide a link? Lancet 1997;349:1391–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.