Abstract

Objectives

Ascertain the extent of differences between men and women in dispensed drugs since there is a lack of comprehensive overviews on sex differences in the use of prescription drugs.

Design

Cross-sectional population database analysis.

Methods

Data on all dispensed drugs in 2010 to the entire Swedish population (9.3 million inhabitants) were obtained from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register. All pharmacological groups with ambulatory care prescribing accounting for >75% of the total volume in Defined Daily Doses and a prevalence of >1% were included in the analysis. Crude and age-adjusted differences in prevalence and incidence were calculated as risk ratios (RRs) of women/men.

Results

In all, 2.8 million men (59%) and 3.6 million women (76%) were dispensed at least one prescribed drug during 2010. Women were dispensed more drugs in all age groups except among children under the age of 10. The largest sex difference in prevalence in absolute numbers was found for antibiotics that were more common in women, 265.5 patients (PAT)/1000 women and 191.3 PAT/1000 men, respectively. This was followed by thyroid therapy (65.7 PAT/1000 women and 13.1 PAT/1000 men) and antidepressants (106.6 PAT/1000 women and 55.4 PAT/1000 men). Age-adjusted relative sex differences in prevalence were found in 48 of the 50 identified pharmacological groups. The pharmacological groups with the largest relative differences of dispensed drugs were systemic antimycotics (RR 6.6 CI 6.4 to 6.7), drugs for osteoporosis (RR 4.9 CI 4.9 to 5.0) and thyroid therapy (RR 4.5 CI 4.4 to 4.5), which were dispensed to women to a higher degree. Antigout agents (RR 0.4 CI 0.4 to 0.4), psychostimulants (RR 0.6 CI 0.6 to 0.6) and ACE inhibitors (RR 0.7 CI 0.7 to 0.7) were dispensed to men to a larger proportion.

Conclusions

Substantial differences in the prevalence and incidence of dispensed drugs were found between men and women. Some differences may be rational and desirable and related to differences between the sexes in the incidence or prevalence of disease or by biological differences. Other differences are more difficult to explain on medical grounds and may indicate unequal treatment.

Keywords: Epidemiology, General Medicine (see Internal Medicine), Public Health

Article summary.

Article focus

To use drug dispensing data to analyse drug utilisation in men and women in a whole country.

To identify areas of potential discrepancies in drugs dispensed to men and women.

To review the existing literature for explanations for differences in drug use between men and women.

To raise awareness about the differences in drug use between men and women which may not be rational.

Key messages

Differences in men and women in the prevalence and incidence of dispensed drugs were found in Sweden overall, and in 48 of 50 pharmacological groups.

Many sex differences found in our study may be explained by sex differences in morbidity or biology. Other differences are hard to explain on medical grounds and may indicate unequal treatment.

There are few studies analysing the rationale of the observed sex differences.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A strength of this study is the complete coverage including all dispensed prescription drugs to the entire Swedish population regardless of patient co-payment.

Another strength is the data source using dispensed drugs which is likely to provide a more accurate picture of actual drug consumption than data on prescriptions collected from medical records.

A limitation is that information on the diagnoses or conditions the drugs were prescribed for was not included. The study also lacked information on whether the patients actually used the dispensed drugs or not, a problem shared with most clinical trials and studies on drug utilisation.

Introduction

Drug therapy plays an important role in preserving people's health and improving their quality of life. Consequently, drugs are the most important treatment options for most diseases and the majority of medical consultations result in a prescription.1 Furthermore, pharmaceuticals also constitute a significant proportion of healthcare spending, increasing more rapidly than other healthcare components in many countries.2 3 In Sweden, pharmaceuticals accounted for 12.6% of the total healthcare expenditure in 2010,4 but the growth has been moderated after the implementation of major reforms.5

Rational drug use implies that ‘patients receive medications appropriate to their clinical needs, in doses that meet their own individual requirements, for an adequate period of time, and at the lowest cost to them and the community’.6 Individual requirements indicate that severity of disease, comorbidity, renal function and age should be considered in addition to sex and gender. While it is evident that biological differences, commonly referred to as ‘sex differences’, should be considered when prescribing medicines, it is unclear to what extent sociocultural differences, commonly referred to as ‘gender differences’, should be considered by the prescribing physician. Sex differences in drug use have been demonstrated in several therapeutic areas.7–11 However, there is a lack of both comprehensive overviews on sex and gender differences of drug use in entire populations and especially studies analysing the rationale behind the observed differences. Variations in morbidity may explain some differences, whereas other differences may indicate inequities and underuse or overuse of certain drugs in men or women.

WHO defines ‘drug utilisation’ as ‘the marketing, distribution, prescription, and use of drugs in a society, with special emphasis on the medical, social, and economic consequences’.12 Drug utilisation data can be derived from different levels in the medication use process: sales data from the manufacturers to wholesalers, the dispensing data at pharmacies or patient consumption surveys.13 14 The use of dispensed prescriptions as a measure of drug exposure has many advantages since it eliminates recall bias and improves the accuracy of the information on drug use.13 15 In 2005, a national registry on dispensed drugs to the entire Swedish population was established.16 It contains complete data (>99% coverage) with unique identifiers of all prescribed drugs dispensed to the entire Swedish population of 9.3 million inhabitants, and may offer a good opportunity to study sex differences in drug use.

The aim of this study was to describe and analyse differences in the prevalence and incidence between men and women of drugs dispensed to the Swedish population. The findings may subsequently be used to plan future studies to address differences suggesting inequity in treatment approaches.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study analysing sex differences in the prevalence and incidence of drugs dispensed in ambulatory care in Sweden in 2010, overall and within different pharmacological groups. Data were collected from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register.16

The period prevalence was defined as the proportion of the population in the country dispensed ≥1 prescription in 2010 and measured by the number of patients exposed per 1000 inhabitants (PAT/TIN). Incidence was defined as the proportion of the population having at least one prescription dispensed in a pharmacy in 2010 after a 1-year wash-out period with no drug dispensed and was measured by the number of patients per 1000 person-years (PAT/1000 PYs).

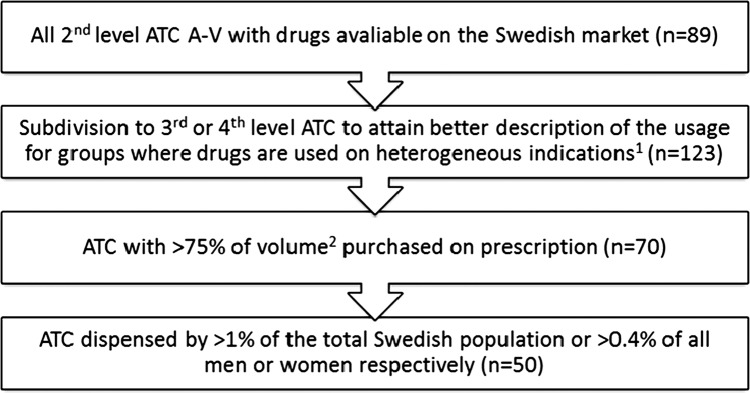

Pharmacological groups were selected by using the following procedure:

All 89 Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) second level groups with drugs available on the Swedish market17 18 were identified.

In large ATC groups and ATC groups with drugs used for multiple heterogeneous indications, that is, cardiac therapy (C01), agents acting on the renin–angiotensin system (C09), sex hormones (G03), urologicals (G04), analgesics (N02), psycholeptics (N05), psychoanaleptics (N06), ophthalmologicals (S01), a subdivision was done to the ATC third or fourth level to attain a more clinically relevant description of the utilisation.

ATC groups with less than 75% of the total sales volume in the country purchased on prescription were excluded since sex distribution was not possible to collect for those purchased over-the-counter or used in inpatient care. Volume was measured in the technical unit numbers of Defined Daily Doses (DDDs), except for eight pharmacological groups for which there were no DDDs assigned.18 For these groups, packages were used as a volume measure. Calculations of the proportion of the total volume dispensed as prescriptions in ambulatory care were based on aggregated volume data from all Swedish pharmacies.

For the identified ATC groups at various hierarchical levels, groups that were dispensed to less than 1% of the total Swedish population or to less than 0.4% of men or women, respectively, were excluded to avoid random variation due to small numbers.

Crude and age-adjusted values were calculated. Age standardisation was performed by direct standardisation, where the Swedish population on 31 December 2009 (4 649 014 men and 4 691 668 women19) was used as the standard population. In the calculations, 5-year age groups were used. Differences between the sexes were calculated as a risk ratio (RR) of women/men with 95% CI. All analyses were performed in Microsoft Excel 2007 and SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) using descriptive statistical methods.

Results

In 2010, the total volume of drugs dispensed in Sweden was 5.8 billion DDD, corresponding to 1715 DDD/1000 inhabitants daily. The total expenditures were 35.6 billion Swedish Kronor (SEK; 100 SEK=8.96 GBP, September 2012). Drugs prescribed in ambulatory care, and thus included in the study, accounted for 88% of the total volume and 72% of the total expenditures on drugs in the country.

In all, 2.8 million men (59%) and 3.6 million women (76%) were dispensed at least one prescribed drug during 2010. The older the patient, the higher the likelihood was of being dispensed drugs. Women were in general dispensed more prescription drugs in all age groups except among children under the age of 10, even when hormonal contraceptives were excluded (table 1).

Table 1.

Proportions of the Swedish population dispensed at least one prescribed drug in 2010, by age and sex

| Age group | Men (%) | Women (%) | Women, hormonal contraceptives (G03A) excluded (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–4 | 68 | 64 | 64 |

| 5–9 | 45 | 43 | 43 |

| 10–14 | 39 | 45 | 44 |

| 15–19 | 42 | 77 | 62 |

| 20–24 | 39 | 77 | 60 |

| 25–29 | 42 | 74 | 62 |

| 30–34 | 46 | 73 | 65 |

| 35–39 | 50 | 73 | 66 |

| 40–44 | 53 | 73 | 67 |

| 45–49 | 58 | 74 | 71 |

| 50–54 | 64 | 78 | 77 |

| 55–59 | 72 | 82 | 82 |

| 60–64 | 79 | 85 | 85 |

| 65–69 | 84 | 88 | 88 |

| 70–74 | 89 | 92 | 92 |

| 75–79 | 93 | 94 | 94 |

| 80–84 | 95 | 96 | 96 |

| 85–89 | 96 | 96 | 96 |

| 90+ | 97 | 99 | 99 |

| Total | 59 | 76 | 71 |

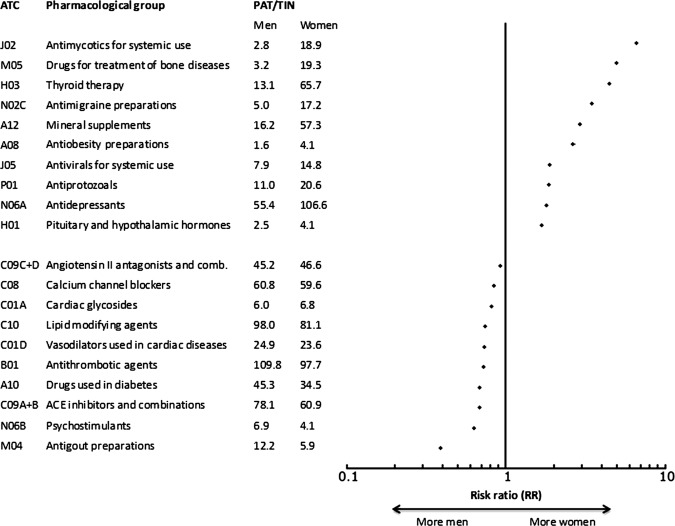

Crude sex differences in prevalence were found in 48 of the 50 pharmacological ATC groups included (figure 1, table 2). After age adjustment, sex differences remained in 48 ATC groups. Concerning drugs for glaucoma (S01E) and endocrine drugs (L02), the sex differences disappeared after age adjustment, while the opposite was seen for angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) (C09C+D) and calcium channel blockers (C08), which were more common in men after age adjustment. β blocking agents (C07) and cardiac glycosides (C01A) were more common in women before age adjustment, but were found to be more common in men after adjustment. The large differences in drugs for treatment of bone diseases such as osteoporosis (M05), thyroid therapy (H03), mineral supplements (A12) and antidementia drugs (N06D) diminished after age adjustment, even though they still were more common in women after adjustment (table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the selection of pharmacological groups included in the specific analyses on sex and gender differences in different therapeutic areas. 1Cardiac therapy (C01), agents acting on the renin–angiotensin system (C09), sex hormones (G03), urologicals (G04), analgesics (N02), psycholeptics (N05), psychoanaleptics (N06) and ophthalmologicals (S01). 2Volume was measured in Defined Daily Doses (DDDs), except for eight ATC groups without any assigned DDD values where packages were used instead.

Table 2.

Sex differences in prevalence of drug therapy in Sweden in 2010 by pharmacological group

| ATC | Pharmacological group | PAT/TIN |

RR (95% CI) | Age-adjusted RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Women/men | Women/men | ||

| J02 | Antimycotics for systemic use | 2.75 | 18.90 | 6.87 (6.74 to 7.00) | 6.56 (6.44 to 6.68) |

| M05 | Drugs for treatment of bone diseases | 3.19 | 19.28 | 6.04 (5.94 to 6.14) | 4.95 (4.87 to 5.03) |

| H03 | Thyroid therapy | 13.12 | 65.67 | 5.00 (4.96 to 5.05) | 4.46 (4.42 to 4.50) |

| N02C | Antimigraine Preparations | 5.03 | 17.24 | 3.43 (3.38 to 3.48) | 3.44 (3.39 to 3.49) |

| A12 | Mineral supplements | 16.19 | 57.29 | 3.54 (3.51 to 3.57) | 2.90 (2.88 to 2.92) |

| A08 | Antiobesity preparations | 1.59 | 4.13 | 2.60 (2.53 to 2.67) | 2.62 (2.55 to 2.69) |

| J05 | Antivirals for systemic use | 7.85 | 14.79 | 1.88 (1.86 to 1.91) | 1.86 (1.84 to 1.89) |

| P01 | Antiprotozoals | 11.00 | 20.55 | 1.87 (1.85 to 1.89) | 1.85 (1.83 to 1.87) |

| N06A | Antidepressants | 55.35 | 106.60 | 1.93 (1.92 to 1.93) | 1.79 (1.78 to 1.80) |

| H01 | Pituitary and hypothalamic hormones and analogues | 2.46 | 4.08 | 1.66 (1.62 to 1.70) | 1.66 (1.63 to 1.70) |

| N05B | Anxiolytics | 39.39 | 70.01 | 1.78 (1.77 to 1.79) | 1.60 (1.59 to 1.61) |

| N05C | Hypnotics and sedatives | 58.35 | 103.83 | 1.78 (1.77 to 1.79) | 1.56 (1.56 to 1.57) |

| M03 | Muscle relaxants | 6.38 | 9.98 | 1.56 (1.54 to 1.59) | 1.53 (1.51 to 1.56) |

| B03 | Antianaemic preparations | 40.35 | 73.24 | 1.82 (1.81 to 1.83) | 1.48 (1.47 to 1.49) |

| J01 | Antibacterials for systemic use | 191.26 | 265.58 | 1.39 (1.39 to 1.39) | 1.36 (1.36 to 1.36) |

| L04 | Immunosuppressants | 7.32 | 10.05 | 1.37 (1.35 to 1.39) | 1.33 (1.31 to 1.35) |

| G04BD | Urinary antispasmodics | 6.12 | 9.61 | 1.57 (1.55 to 1.60) | 1.33 (1.31 to 1.35) |

| A02 | Drugs for acid related disorders | 70.08 | 101.87 | 1.45 (1.45 to 1.46) | 1.31 (1.31 to 1.32) |

| H02 | Corticosteroids for systemic use | 37.17 | 51.98 | 1.40 (1.39 to 1.41) | 1.30 (1.30 to 1.31) |

| S01B | Anti-inflammatory agents | 12.72 | 18.95 | 1.49 (1.47 to 1.50) | 1.30 (1.29 to 1.31) |

| A07 | Antidiarrhoeals, intestinal anti-inflammatory/anti-infective agents | 13.77 | 19.35 | 1.40 (1.39 to 1.42) | 1.29 (1.28 to 1.30) |

| N02A | Opioids | 66.90 | 92.97 | 1.39 (1.38 to 1.40) | 1.27 (1.27 to 1.28) |

| C03 | Diuretics | 59.48 | 92.83 | 1.56 (1.55 to 1.57) | 1.24 (1.24 to 1.25) |

| S02 | Otologicals | 4.54 | 5.71 | 1.26 (1.24 to 1.28) | 1.23 (1.21 to 1.25) |

| R03 | Drugs for obstructive airway diseases | 71.79 | 88.80 | 1.24 (1.23 to 1.24) | 1.20 (1.20 to 1.21) |

| S03 | Ophthalmological and otological preparations | 23.31 | 28.38 | 1.22 (1.21 to 1.23) | 1.18 (1.17 to 1.19) |

| N03 | Antiepileptics | 18.22 | 22.08 | 1.21 (1.20 to 1.22) | 1.15 (1.14 to 1.16) |

| N05A | Antipsychotics | 13.59 | 16.51 | 1.21 (1.20 to 1.23) | 1.11 (1.09 to 1.12) |

| N06D | Antidementia drugs | 3.38 | 5.41 | 1.60 (1.57 to 1.63) | 1.10 (1.07 to 1.12) |

| N04 | Anti-Parkinson drugs | 6.83 | 8.49 | 1.24 (1.22 to 1.26) | 1.06 (1.05 to 1.08) |

| S01E | Antiglaucoma preparations and miotics | 13.57 | 18.49 | 1.36 (1.35 to 1.38) | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.03) |

| L02 | Endocrine therapy | 6.34 | 7.60 | 1.20 (1.18 to 1.22) | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.97) |

| C07 | β blocking agents | 97.82 | 107.57 | 1.10 (1.10 to 1.10) | 0.94 (0.93 to 0.94) |

| C09C+D | Angiotensin II antagonists and combinations | 45.16 | 46.56 | 1.03 (1.02 to 1.04) | 0.91 (0.91 to 0.92) |

| C08 | Calcium channel blockers | 60.84 | 59.61 | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) | 0.84 (0.84 to 0.84) |

| C01A | Cardiac glycosides | 6.01 | 6.83 | 1.14 (1.12 to 1.16) | 0.81 (0.79 to 0.82) |

| C10 | Lipid modifying agents | 98.03 | 81.05 | 0.83 (0.82 to 0.83) | 0.74 (0.73 to 0.74) |

| C01D | Vasodilators used in cardiac diseases | 24.94 | 23.61 | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.95) | 0.73 (0.72 to 0.73) |

| B01 | Antithrombotic agents | 109.81 | 97.68 | 0.89 (0.89 to 0.89) | 0.72 (0.72 to 0.73) |

| A10 | Drugs used in diabetes | 45.27 | 34.48 | 0.76 (0.76 to 0.77) | 0.68 (0.68 to 0.69) |

| C09A+B | ACE-inhibitors and combinations | 78.14 | 60.90 | 0.78 (0.78 to 0.78) | 0.68 (0.67 to 0.68) |

| N06B | Psychostimulants | 6.94 | 4.11 | 0.59 (0.58 to 0.60) | 0.62 (0.61 to 0.64) |

| M04 | Antigout preparations | 12.24 | 5.91 | 0.48 (0.48 to 0.49) | 0.38 (0.38 to 0.39) |

Crude and age-adjusted relative differences for included ATC groups. The following pharmacological groups are not presented in the table due to sex-specific indications; G02 Other gynaecologicals (dispensed to 9.79 PAT/1000 women and 0.20 PAT/1000 men), G03A Hormonal contraceptives (dispensed to 132.05 PAT/1000 women and 0.08 PAT/1000 men), G03C Estrogens (dispensed to 69.62 PAT/1000 women and 0.08 PAT/1000 men), G03D Progestogens (dispensed to 15.90 PAT/1000 women and 0.03 PAT/1000 men), G03F Progestogens and Estrogens in combination (dispensed to 12.26 PAT/1000 women and 0.00 PAT/1000 men), G04C Drugs used in benign prostatic hypertrophy (dispensed to 0.25 PAT/1000 women and 26.23 PAT/1000 men) and G04BE Drugs used in erectile dysfunction (dispensed to 25.38 PAT/1000 men and 0.07 PAT/1000 women).

The relative differences were calculated with women as the numerator and men as the denominator. The table is sorted starting with the group with the largest age-adjusted sex difference. PAT/TIN=number of patients (men or women) per 1000 individuals. N=4 649 014 men and 4 691 668 women.

ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical; RR, risk ratio.

The pharmacological groups with the largest relative differences more commonly being dispensed to women were antimycotics for systemic use (RR 6.6), drugs for osteoporosis (RR 4.9) and thyroid therapy (RR 4.5), while a larger proportion of men were dispensed antigout preparations (RR 0.4), psychostimulants (0.6) and ACE-inhibitors (RR 0.7) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pharmacological groups with the highest age-adjusted relative differences in prevalence in 2010.

The largest sex difference in absolute numbers was found for systemic antibacterials (J01) that were more common in women, 265.5 PAT/1000 women and 191.3 PAT/1000 men, respectively. This was followed by thyroid therapy (H03), 65.7 PAT/1000 women and 13.1 PAT/1000 men, and antidepressants (N06A), 106.6 PAT/1000 women and 55.4 PAT/1000 men.

The incidence showed a similar pattern as the prevalence pattern (table 3). However, the sex differences were substantially higher for endocrine therapy (L02) and urinary antispasmodic agents (G04BD). Before age adjustment, 40 pharmacological groups were more frequently dispensed to women and eight groups to men. After age adjustment, sex differences remained in 36 and 11 ATC groups for women and men, respectively. In only one pharmacological group, drugs for treatment of bone diseases (M05), the sex difference diminished substantially after age adjustment.

Table 3.

Sex differences in incidence of drug therapy in Sweden in 2010 by pharmacological group

| ATC | Pharmacological group | PAT/1000 PYs |

RR (95% CI) | Age-adjusted RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Women/men | Women/men | ||

| J02 | Antimycotics for systemic use | 2.28 | 13.23 | 5.80 (5.68 to 5.92) | 5.49 (5.38 to 5.60) |

| H03 | Thyroid therapy | 1.55 | 5.77 | 3.72 (3.62 to 3.81) | 3.49 (3.40 to 3.58) |

| M05 | Drugs for treatment of bone diseases | 0.97 | 3.98 | 4.11 (3.98 to 4.24) | 3.49 (3.38 to 3.60) |

| N02C | Antimigraine preparations | 1.89 | 4.99 | 2.64 (2.57 to 2.70) | 2.67 (2.61 to 2.74) |

| A08 | Antiobesity preparations | 0.55 | 1.41 | 2.57 (2.45 to 2.69) | 2.60 (2.48 to 2.72) |

| H01 | Pituitary and hypothalamic hormones and analogues | 0.99 | 2.45 | 2.47 (2.38 to 2.55) | 2.48 (2.40 to 2.57) |

| A12 | Mineral supplements | 5.82 | 14.85 | 2.55 (2.52 to 2.59) | 2.21 (2.18 to 2.24) |

| J05 | Antivirals for systemic use | 4.60 | 8.53 | 1.85 (1.82 to 1.89) | 1.80 (1.77 to 1.83) |

| P01 | Antiprotozoals | 9.38 | 16.83 | 1.80 (1.77 to 1.82) | 1.79 (1.76 to 1.81) |

| B03 | Antianaemic preparations | 12.28 | 23.72 | 1.93 (1.91 to 1.95) | 1.70 (1.68 to 1.72) |

| N06A | Antidepressants | 15.35 | 24.71 | 1.61 (1.59 to 1.62) | 1.52 (1.51 to 1.54) |

| L02 | Endocrine therapy | 1.37 | 2.43 | 1.78 (1.73 to 1.84) | 1.52 (1.48 to 1.56) |

| N05B | Anxiolytics | 17.90 | 28.41 | 1.59 (1.57 to 1.60) | 1.47 (1.46 to 1.48) |

| M03 | Muscle relaxants | 4.50 | 6.67 | 1.48 (1.46 to 1.51) | 1.46 (1.44 to 1.49) |

| A07 | Antidiarrhoeals, intestinal anti-inflammatory/antiinfective agents | 6.68 | 10.27 | 1.39 (1.37 to 1.41) | 1.39 (1.37 to 1.41) |

| A02 | Drugs for acid related disorders | 25.47 | 37.35 | 1.47 (1.46 to 1.48) | 1.38 (1.37 to 1.39) |

| N05C | Hypnotics and sedatives | 18.90 | 26.94 | 1.43 (1.41 to 1.44) | 1.32 (1.31 to 1.34) |

| S01B | Anti-inflammatory agents | 9.27 | 13.71 | 1.48 (1.46 to 1.50) | 1.29 (1.27 to 1.31) |

| H02 | Corticosteroids for systemic use | 21.36 | 28.28 | 1.32 (1.31 to 1.33) | 1.27 (1.26 to 1.28) |

| N03 | Antiepileptics | 4.76 | 6.29 | 1.32 (1.30 to 1.35) | 1.25 (1.22 to 1.27) |

| L04 | Immunosuppressants | 1.43 | 1.80 | 1.26 (1.22 to 1.30) | 1.23 (1.20 to 1.27) |

| J01 | Antibacterials for systemic use | 126.14 | 153.73 | 1.22 (1.21 to 1.22) | 1.21 (1.20 to 1.21) |

| R03 | Drugs for obstructive airway diseases | 27.19 | 32.11 | 1.18 (1.17 to 1.19) | 1.19 (1.18 to 1.20) |

| N04 | Anti-Parkinson drugs | 1.67 | 2.26 | 1.35 (1.31 to 1.39) | 1.19 (1.15 to 1.22) |

| S02 | Otologicals | 3.39 | 4.04 | 1.19 (1.17 to 1.22) | 1.17 (1.14 to 1.19) |

| N02A | Opioids | 39.55 | 48.30 | 1.22 (1.21 to 1.23) | 1.14 (1.14 to 1.15) |

| C03 | Diuretics | 10.63 | 14.35 | 1.35 (1.33 to 1.37) | 1.14 (1.13 to 1.15) |

| S03 | Ophthalmological and otological preparations | 18.43 | 21.41 | 1.16 (1.15 to 1.17) | 1.14 (1.13 to 1.15) |

| G04BD | Urinary antispasmodics | 2.63 | 3.33 | 1.27 (1.24 to 1.30) | 1.10 (1.08 to 1.13) |

| N05A | Antipsychotics | 3.27 | 4.03 | 1.23 (1.21 to 1.26) | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.10) |

| N06D | Antidementia drugs | 0.91 | 1.38 | 1.52 (1.46 to 1.58) | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.11) |

| B01 | Antithrombotic agents | 15.05 | 17.48 | 1.16. (1.15 to 1.7) | 1.05 (1.04 to 1.06) |

| C07 | β blocking agents | 12.16 | 13.61 | 1.12 (1.11 to 1.13) | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.03) |

| S01E | Antiglaucoma preparations and miotics | 1.90 | 2.15 | 1.13 (1.10 to 1.16) | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.98) |

| C09C+D | Angiotensin II antagonists and combinations | 6.18 | 6.42 | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.05) | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.96) |

| C08 | Calcium channel blockers | 10.35 | 10.72 | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.05) | 0.93 (0.92 to 0.94) |

| C01A | Cardiac glycosides | 1.09 | 1.24 | 1.14 (1.10 to 1.18) | 0.86 (0.82 to 0.89) |

| C09A+B | ACE-inhibitors and combinations | 14.28 | 13.11 | 0.92 (0.91 to 0.93) | 0.83 (0.82 to 0.84) |

| C10 | Lipid modifying agents | 13.01 | 11.28 | 0.87 (0.86 to 0.88) | 0.81 (0.80 to 0.82) |

| A10 | Drugs used in diabetes | 4.83 | 3.79 | 0.79 (0.77 to 0.80) | 0.73 (0.72 to 0.75) |

| N06B | Psychostimulants | 2.36 | 1.57 | 0.67 (0.65 to 0.69) | 0.70 (0.68 to 0.72) |

| C01D | Vasodilators used in cardiac diseases | 8.34 | 6.93 | 0.83 (0.82 to 0.84) | 0.69 (0.68 to 0.70) |

| M04 | Antigout preparations | 2.71 | 1.44 | 0.53 (0.51 to 0.55) | 0.44 (0.42 to 0.45) |

Crude and age-adjusted relative differences for included ATC groups. The following pharmacological groups were excluded from the table due to sex-specific indications; G02 Other gynaecologicals (dispensed to 5.33 PAT/1000 PYs in women and 0.03 PAT/1000 PYs in men), G03A Hormonal contraceptives (dispensed to 42.09 PAT/1000 PYs in women and 0.04 PAT/1000 PYs in men), G03C Estrogens (dispensed to 16.44 PAT/1000 PYs in women and 0.03 PAT/1000 PYs in men), G03D Progestogens (dispensed to 11.20 PAT/1000 PYs in women and 0.01 PAT/1000 PYs in men), G03F Progestogens and estrogens in combination (dispensed to 2.56 PAT/1000 PYs in women and 0.00 PAT/1000 PYs in men), G04C Drugs used in benign prostatic hypertrophy (dispensed to 0.20 PAT/1000 PYs in women and 7.34 PAT/1000 PYs in men) and G04BE Drugs used in erectile dysfunction (dispensed to 0.03 PAT/1000 PYs in women and 10.16 PAT/1000 PYs in men).

The relative differences were calculated with women as the numerator and men as the denominator. The table is sorted starting with the group with the largest age-adjusted sex difference. PAT/1000 PYs=number of patients (men or women) per 1000 patient-years. N=4 649 014 men and 4 691 668 women.

ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical; RR, risk ratio.

Discussion

This study of all dispensed prescription drugs in Sweden shows substantial differences between men and women. It is obvious that some of these differences may be explained by variations in disease prevalence, severity of disease, pathophysiology, diagnostics and treatment response or by other biological differences such as those induced by pregnancy and/or lactation. However, it is also evident that other differences lack a rational medical explanation.

Throughout their lifespan, women have more contact with the healthcare system,20–22 which may provide them with an extra opportunity for detecting disease and receiving prescriptions. In the premenopausal years, a woman's need for contraceptives, pregnancy and childbirth and, in the perimenopausal and postmenopausal period, screening programmes for breast and cervical cancers and gynaecological disorders require healthcare consultations.22 Also, chronic disabling diseases associated with a chronic need for medication, such as musculoskeletal disorders, are more common in women than men.20 From a gender perspective, studies have shown that men are less prone to seek preventive healthcare.21

Some differences between the sexes are expected. The higher proportion of women dispensed antimycotics could partly be explained by gynaecological infections such as vaginitis. Also, the 4.5 times higher proportion of dispensed thyroid therapy corresponds to a four times higher prevalence of impaired thyroid function in women.23 The sex difference in the proportion of dispensed drugs for migraine could be explained by a 2–3 times higher prevalence of migraine among women.24 Men were dispensed more psychostimulants, corresponding to a higher prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder25 and autism.26

The largest sex difference in absolute numbers was observed for antibiotics, more commonly dispensed to women. A common reason for prescribing antibiotics in primary care is urinary tract infection, which is more prevalent in women.27 An overdiagnosis of this condition in women has, however, been reported, which could potentially explain some of the higher number of women being dispensed these drugs.28 Women were dispensed more antiobesity drugs than men in spite of obesity being more common in men.29 30 Also, more women than men undergo obesity surgery.31 There are reasons to believe that the sociocultural pressure to be slim is higher for women and studies have shown that women are more dissatisfied with their weight and their body than men.32 33 This could explain the prescription pattern.

In the cardiovascular field, several differences in the dispensation of prescribed drugs were found. ACE inhibitors, primarily used for the treatment of heart failure and hypertension, with the same prevalence in both sexes, were more commonly dispensed to men. This may be due to the higher frequency of coughing as an adverse event in women.34 However, the alternative treatment ARB was dispensed to women and men to the same extent. Our findings may therefore indicate an underuse of renin–angiotensin agents in women. Lipid lowering drugs were also dispensed more frequently to men. The higher proportion in men may be explained by the higher prevalence of ischaemic heart disease. However, studies have shown that these drugs are underused for secondary prevention in women.35–38 Reasons for this could be that women not only suffer more from myalgia as an adverse reaction39 but also that women are older and have more comorbidity when suffering from cardiovascular disease, thus receiving less intensive secondary preventive medication.

Men were dispensed more anticoagulants. The most common indication for anticoagulants is atrial fibrillation, a condition more commonly found in men but carrying a higher risk of fatal complications like embolic stroke for women.40 Underuse of anticoagulants in women with atrial fibrillation has been shown in earlier studies.37 38 41–44 Men were also dispensed antiarrhythmic drugs to a higher degree than women. This may be appropriate as women have a higher risk of the fatal arrhythmia ‘torsade de pointe-ventricular tachycardia’ induced by some antiarrhythmics like sotalol and quinidine.45

The main strength of this study is the complete coverage of all dispensed prescription drugs to the entire Swedish population. This provides a population-based overview of drug use difficult to acquire in many other health systems.15 Although it is important to recognise that filling a prescription does not necessarily imply that the drugs are taken, we have no reason to believe that misclassification of drug use should be more prevalent in one sex. Furthermore, data on dispensed drugs are closer to the actual intake than data on prescribed drugs, and it is free from the recall bias common in patient reported data.46 The most important limitation is the lack of information on patient characteristics and clinical data to assess the rationale behind the observed differences. Moreover, it is important to emphasise that gender differences may only be hypothesised from these data.

In conclusion, in this large study we found substantial differences in drugs dispensed to men and women. In an attempt to explain these sex differences, we searched the literature. Some sex disparities could be explained by the differences in the prevalence of disease or frequency of adverse reactions. Less medically justified explanations were also identified, such as overestimation of risk versus benefit in women compared with men. We also found suggestions that gender aspects such as societal acceptance of overweight in women compared with men may be involved. More research and a greater awareness of the influence of sex and gender in health and disease are needed to ensure rational drug use in both men and women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Katarina Baatz, The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare for extracting and processing data. We thank Dr Gunilla Ringbäck Weitoft, The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare for valuable discussions about the study design. We thank Nina Johnston, Centre for Gender Medicine and Brian Godman, Clinical Pharmacology, both at Karolinska Institutet, for help in revising the manuscript. We also thank the expert groups of the regional Drug and Therapeutics Committee in Stockholm County Council for clinical comments on the study findings.

Footnotes

Contributors: Everyone listed as an author fulfils all three of the ICMJE guidelines for authorship. KS-G conceived the idea of the study and was together with DL, BW and MvE responsible for the design of the study. DL and BW were responsible for undertaking data analysis and producing the tables and graphs. DL, BW, MvE, KS-G and UB provided input for the data analysis. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by DL and then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision. DL was responsible for the acquisition of the data, and DL, BW, MvE, KSG and UB contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study was funded by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR) within the Sustainable Equality Project (HÅJ) no. SKL 08/2254, Stockholm County Council, and the Centre for Gender Medicine (Erica Lederhausen Foundation), Karolinska Institutet.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the regional Ethics Committee at Karolinska Institutet, Sweden. Ref. no. 2010/788–31/5.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Proposals for data sharing should be sent to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Wilson A, McDonald P, Hayes L, et al. Health promotion in the general practice consultation: a minute makes a difference. BMJ 1992;304:227–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorpe KE. The rise in health care spending and what to do about it. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:1436–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zuvekas SH, Cohen JW. Prescription drugs and the changing concentration of health care expenditures. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:249–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Health Data 2012—Frequently Requested Data.

- 5.Wettermark B, Godman B, Andersson K, et al. Recent national and regional drug reforms in Sweden: implications for pharmaceutical companies in Europe. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:537–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization The rational use of drugs. WHO Report of the Conference of Experts, Nairobi. 1985

- 7.Campbell CI, Weisner C, Leresche L, et al. Age and gender trends in long-term opioid analgesic use for noncancer pain. Am J Public Health 2010;100:2541–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnell K, Fastbom J. Gender and use of hypnotics or sedatives in old age: a nationwide register-based study. Int J Clin Pharm 2011;33:788–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston N, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Lagerqvist B. Are we using cardiovascular medications and coronary angiography appropriately in men and women with chest pain? Eur Heart J 2011;32:1331–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klungel OH, de Boer A, Paes AH, et al. Sex differences in antihypertensive drug use: determinants of the choice of medication for hypertension. J Hypertens 1998;16:1545–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stock SA, Stollenwerk B, Redaelli M, et al. Sex differences in treatment patterns of six chronic diseases: an analysis from the German statutory health insurance. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:343–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization (WHO) The selection of essential drugs. Geneva, Switzerland, 1977. Technical Report Series No. 615

- 13.Wettermark B, Vlahovic-Palcevski V, Salvesen Blix H, et al. In: Hartzema AG, Tilson HH, Chan KA, eds. Drug Utilization Research. Pharmacoepidemiology and therapeutic risk assessment. Cincinatti, USA: Harwey Whitney Books, 2008:159–95 [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO International Working Group for Drug Statistics Methodology, WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Utilization Research and Clinical Pharmacological Services Introduction to drug utilization research. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 15.West SL, Savitz DA, Koch G, et al. Recall accuracy for prescription medications: self-report compared with database information. Am J Epidemiol 1995;142:1103–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, et al. The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register—opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:726–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LIF. Swedish Physician's Desk Reference (FASS) Available at: http://www.fass.se (accessed 4 Nov 2011)

- 18.WHO Collaborating Center for Drug Statistics Methodology Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment, 2012. Oslo, 2011

- 19.Statistics Sweden. Population statistics for Sweden 1960–2010. [Befolkningsstatistik i sammandrag 1960-2010]. Stockholm, 2011.

- 20.Brooks PM. The burden of musculoskeletal disease—a global perspective. Clin Rheumatol 2006;25:778–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinkhasov RM, Wong J, Kashanian J, et al. Are men shortchanged on health? Perspective on health care utilization and health risk behavior in men and women in the United States. Int J Clin Pract 2010;64:475–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaidya V, Partha G, Karmakar M. Gender differences in utilization of preventive care services in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:140–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjoro T, Holmen J, Kruger O, et al. Prevalence of thyroid disease, thyroid dysfunction and thyroid peroxidase antibodies in a large, unselected population. The Health Study of Nord-Trondelag (HUNT). Eur J Endocrinol 2000;143:639–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roy J, Stewart WF. Estimation of age-specific incidence rates from cross-sectional survey data. Stat Med 2010;29:588–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaub M, Carlson CL. Gender differences in ADHD: a meta-analysis and critical review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36:1036–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baird G, Simonoff E, Pickles A, et al. Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). Lancet 2006;368:210–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dielubanza EJ, Schaeffer AJ. Urinary tract infections in women. Med Clin North Am 2011;95:27–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmiemann G, Kniehl E, Gebhardt K, et al. The diagnosis of urinary tract infection: a systematic review. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010;107:361–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neovius M, Janson A, Rossner S. Prevalence of obesity in Sweden. Obes Rev 2006;7:1–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States—gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev 2007;29:6–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lestner ESH, Sundberg L, Håkansson A, et al. Report specialised obesity treatment [Rapport Specialicerad obesitasbehandling]. Stockholm: Avdelningen för somatisk specialistvård, Hälso- och sjukvårdsförvaltningen, Stockholms läns landsting, Stockholm, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivarsson T, Svalander P, Litlere O, et al. Weight concerns, body image, depression and anxiety in Swedish adolescents. Eat Behav 2006;7:161–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waaddegaard M, Petersen T. Dieting and desire for weight loss among adolescents in Denmark: a questionnaire survey. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2002;10:329–46 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mackay FJ, Pearce GL, Mann RD. Cough and angiotensin II receptor antagonists: cause or confounding? Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999;47:111–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho L, Hoogwerf B, Huang J, et al. Gender differences in utilization of effective cardiovascular secondary prevention: a Cleveland clinic prevention database study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:515–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kapral MK, Degani N, Hall R, et al. Gender differences in stroke care and outcomes in Ontario. Womens Health Issues 2011;21:171–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stramba-Badiale M. Women and research on cardiovascular diseases in Europe: a report from the European Heart Health Strategy (EuroHeart) project. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1677–81D [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wettermark B, Persson A, von Euler M. Secondary prevention in a large stroke population: a study of patients’ purchase of recommended drugs. Stroke 2008;39:2880–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kosek E. Fibromyalgia. In: Schenck-Gustafsson KDP, Pfaff DW, Pisetsky DS, eds. Handbook of clinical gender medicine. Basel: Karger, 2012:164–68 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lip GY, Halperin JL. Improving stroke risk stratification in atrial fibrillation. Am J Med 2010;123:484–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Carlo A, Lamassa M, Baldereschi M, et al. Sex differences in the clinical presentation, resource use, and 3-month outcome of acute stroke in Europe: data from a multicenter multinational hospital-based registry. Stroke 2003;34:1114–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY. Evaluation of risk stratification schemes for ischaemic stroke and bleeding in 182 678 patients with atrial fibrillation: the Swedish Atrial Fibrillation cohort study. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1500–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Insulander P, Vallin H. Arrhythmias. In: Schenck-Gustafsson KDP, Pfaff DW, Pisetsky DS, eds. Handbook of clinical gender medicine. Basel: Karger, 2012:229–36 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reid JM, Dai D, Gubitz GJ, et al. Gender differences in stroke examined in a 10-year cohort of patients admitted to a Canadian teaching hospital. Stroke 2008;39:1090–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Makkar RR, Fromm BS, Steinman RT, et al. Female gender as a risk factor for torsades de pointes associated with cardiovascular drugs. JAMA 1993;270:2590–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coughlin SS. Recall bias in epidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol 1990;43:87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.