Abstract

Objective

To describe breastfeeding practices in rural China using globally recommended indicators and to compare them with practices in neighbouring countries and large emerging economies.

Methods

A community-based, cross-sectional survey of 2354 children younger than 2 years in 26 poor, rural counties in 12 central and western provinces was conducted. Associations between indicators of infant and young child feeding and socioeconomic, demographic and health service variables were explored and rates were compared with the most recent data from China and other nations.

Findings

Overall, 98.3% of infants had been breastfed. However, only 59.4% had initiated breastfeeding early (i.e. within 1 hour of birth); only 55.5% and 9.4% had continued breastfeeding for 1 and 2 years, respectively, and only 28.7% of infants younger than 6 months had been exclusively breastfed. Early initiation of breastfeeding was positively associated with at least five antenatal clinic visits (adjusted odds ratio, aOR: 3.48; P < 0.001) and negatively associated with delivery by Caesarean (aOR: 0.53; P < 0.001) or in a referral-level facility (aOR: 0.6; P = 0.014). Exclusive breastfeeding among children younger than 6 months was positively associated with delivery in a referral-level facility (aOR: 2.22; P < 0.05). Breastfeeding was not associated with maternal age or education, ethnicity or household wealth. Surveyed rates of exclusive and continued breastfeeding were mostly lower than in other nations.

Conclusion

Despite efforts to promote breastfeeding in China, rates are very low. A commitment to improve infant and young child feeding is needed to reduce mortality and morbidity.

Résumé

Objectif

Décrire les pratiques d'allaitement maternel dans la Chine rurale en utilisant des indicateurs recommandés au niveau mondial et en les comparant avec les usages des pays voisins et des grandes économies émergentes.

Méthodes

Une étude transversale a été menée, sur base communautaire, auprès de 2354 enfants âgés de moins de 2 ans, répartis dans 26 comtés ruraux pauvres de 12 provinces du centre et de l'ouest du pays. Les corrélations entre les indicateurs d'allaitement infantile et du jeune enfant et les variables socio-économiques, démographiques et des services de santé ont été explorées et les taux ont été comparés avec les données les plus récentes en provenance de Chine et d'autres pays.

Résultats

Dans l'ensemble, 98,3% des nourrissons avaient été nourris au sein. Cependant, seulement 59,4% avaient bénéficié d'un allaitement précoce (c’est-à-dire au cours de la première heure après la naissance), seuls 55,5% et 9,4% avaient poursuivi l'allaitement maternel pendant respectivement 1 et 2 ans et seulement 28,7% des nourrissons âgés de moins de 6 mois avaient été exclusivement nourris au sein. L'initiation précoce de l'allaitement maternel a été positivement corrélée à au moins cinq consultations prénatales (odds ratio ajusté ORa: 3,48; P<0,001) et négativement corrélée à la naissance par césarienne (ORa: 0,53; P<0,001) ou en hôpital d’aiguillage (ORa: 0,6; P=0,014). L'allaitement maternel exclusif chez les enfants âgés de moins de 6 mois a été associé positivement à une naissance dans un hôpital d’aiguillage (ORa: 2,22; P<0,05). L'allaitement n'a pas été associé à l'âge ni à l'éducation de la mère, ni même à l'ethnicité ou au niveau de richesse du foyer. L’étude a révélé des taux d'allaitement exclusif et continu généralement plus faibles que dans d'autres pays.

Conclusion

Malgré les efforts pour promouvoir l'allaitement maternel en Chine, les taux restent très faibles. Un engagement visant à améliorer l'alimentation du nourrisson et du jeune enfant est nécessaire afin de réduire le taux de mortalité et de morbidité dans cette catégorie de la population.

Resumen

Objetivo

Describir las prácticas de lactancia en las zonas rurales de China por medio de los indicadores recomendados a nivel internacional y compararlas con las prácticas de los países vecinos y de las grandes economías emergentes.

Métodos

Se llevó a cabo una encuesta transversal comunitaria de 2354 niños menores de 2 años en 26 condados rurales pobres de 12 provincias del centro y oeste del país. Se investigaron las relaciones entre los indicadores de la alimentación de lactantes y niños pequeños y las variables socioeconómicas, demográficas y del sistema sanitario, y se compararon los índices con los datos más recientes tanto de China como de otros países.

Resultados

En general, el 98,3% de los niños había sido amamantado. Sin embargo, solo el 59,4% inició la lactancia pronto (esto es, una hora tras el nacimiento); solo el 55,5% y el 9,4% había continuado con la lactancia durante 1 y 2 años, respectivamente, y solo el 28,7% de los lactantes menores de 6 meses había sido amamantado de forma exclusiva. El comienzo temprano de la lactancia estuvo relacionado de forma positiva con al menos cinco visitas clínicas prenatales (coeficiente de posibilidades ajustado, CPa: 3,48; P < 0,001) y relacionado de forma negativa con partos por cesárea (CPa: 0,53; P <0,001) o en un centro de derivación (CPa: 0,6; P = 0,014). La lactancia exclusiva entre los niños menores de 6 meses estuvo asociada de forma positiva con un parto en un centro de derivación (CPa: 2,22; P < 0,05). La lactancia no estuvo asociada con la edad o la educación de la madre, la etnia o la riqueza del hogar. Los índices medidos de lactancia exclusiva y continuada fueron en la mayoría de casos inferiores que los de otras naciones.

Conclusión A pesar de los esfuerzos para promover la lactancia en China, los índices son muy bajos. Con objeto de reducir la mortalidad y la morbilidad, es necesario un compromiso para mejorar la alimentación de lactantes y niños pequeños.

ملخص

الغرض

وصف ممارسات الرضاعة الطبيعية في المناطق الريفية في الصين باستخدام المؤشرات الموصى بها عالمياً ومقارنتها بالممارسات في البلدان المجاورة والاقتصادات الناشئة الكبرى.

الطريقة

تم إجراء دراسة استقصائية مجتمعية متعددة القطاعات على 2354 طفلاً أصغر من سنتين في 26 مقاطعة ريفية فقيرة في 12 إقليماً في وسط وغرب الصين. وتم استعراض الارتباطات بين مؤشرات تغذية الرضع وصغار الأطفال والمتغيرات الاجتماعية والاقتصادية والديمغرافية ومتغيرات الخدمة الصحية وتم مقارنة المعدلات بأحدث البيانات الواردة من الصين وغيرها من البلدان.

النتائج

بشكل عام، كانت نسبة الأطفال الذين رضعوا رضاعة طبيعية 98.3 %، غير أن 59.4 % منهم فقط بدأوا الرضاعة الطبيعية مبكراً (في غضون الساعة الأولى من الولادة)؛ وواصل 55.5 % و 9.4 % فقط الرضاعة الطبيعية لمدة سنة وسنتين، على التوالي، ورضعت نسبة 28.7 % فقط من الرضع الذين تقل أعمارهم عن 6 أشهر رضاعة طبيعية على نحو حصري. وارتبط البدء المبكر في الرضاعة الطبيعية إيجابياً بخمس زيارات سريرية قبل الولادة على الأقل (نسبة الاحتمال المصححة: 3.48 ؛ الاحتمال < 0.001 ) وارتبط سلبياً بالولادة القيصرية (نسبة الاحتمال المصححة: 0.53 ؛ الاحتمال < 0.001 ) أو في مرفق من مرافق مستوى الإحالة (نسبة الاحتمال المصححة: 0.6 ؛ الاحتمال = 0.014 ). وارتبطت الرضاعة الطبيعية الحصرية بين الأطفال الذين تقل أعمارهم عن 6 أشهر إيجابياً بالولادة في مرفق من مرافق مستوى الإحالة (نسبة الاحتمال المصححة: 2.22 ؛ الاحتمال < 0.05 ). ولم ترتبط الرضاعة الطبيعية بسن الأم أو تعليمها أو أصلها العرقي أو ثروة أسرتها. وكانت معدلات الرضاعة الطبيعية الحصرية والمستمرة التي خضعت للدراسة الاستقصائية أقل عن نظيراتها في غيرها من البلدان.

الاستنتاج

برغم جهود تعزيز الرضاعة الطبيعية في الصين، إلا أن المعدلات منخفضة للغاية. وينبغي الالتزام بتحسين تغذية الرضع وصغار الأطفال لتقليل معدل الوفيات والمراضة.

摘要

目的

使用全球推荐的指标描述中国农村的母乳喂养实践,并将其与邻国和大型新兴经济体的实践进行比较。

方法

对12 个中西部省份贫穷乡村的2354 名2 岁以下儿童开展以社区为基础的横断面调查。探讨婴幼儿喂养和社会经济、人口和卫生服务因素之间的关联,并将比例与来自中国和其他国家的最新数据进行比较。

结果

总体而言,98.3%的婴儿接受母乳喂养。然而,新生儿早开奶率只有59.4%(即在出生后的1小时内);分别只有55.5%和9.4%的婴儿持续接受母乳喂养到1 至2 岁,6 个月以下的婴儿纯母乳喂养率只有28.7%。早开奶与至少五次产前检查呈正相关(调整后的优势比,aOR:3.48;P < 0.001),与剖宫产(aOR:0.53;P<0.001)或在县级及以上医疗机构中分娩(aOR:0.6;P = 0.014)呈负相关。6 个月以下婴儿纯母乳喂养与在县级及以上医疗机构中分娩呈正相关(aOR:2.22;P = 0.05)。母乳喂养与产妇年龄或教育、民族或家庭财富无关联。调查的纯母乳喂养率和持续母乳喂养率大多低于其他国家。

结论

尽管中国努力促进母乳喂养,但是比例仍非常低。需要努力改善婴幼儿喂养,降低死亡率和发病率。

Резюме

Цель

Описать практику грудного вскармливания в сельских районах Китая, используя всемирно рекомендованные индикаторы, и сравнить их с практикой в соседних странах и крупных странах с переходной экономикой.

Методы

Было проведено перекрестное обследование на уровне общины 2354 детей в возрасте до двух лет в 26 бедных сельских районах в 12 центральных и западных провинциях. Изучались связи между показателями грудного вскармливания новорожденных и детей раннего возраста с социально-экономическими, демографическими и медицинскими переменными, и сравнивались показатели с последними данными, полученными из Китая и других стран.

Результаты

Всего на грудном вскармливании находилось 98,3% детей. Однако, только 59,4% детей получали ранее грудное вскармливание (т.е. в течение одного часа после родов); только 55,5% и 9,4% продолжали получать грудное молоко в течение одного и двух лет соответственно, и всего 28,7% младенцев в возрасте до 6 месяцев находились исключительно на грудном вскармливании. Ранее начало грудного вскармливания показало положительную статистическую связь, по крайней мере, с пятью посещениями клиники дородового наблюдения (скорректированный относительный риск, сОР: 3,48; P < 0,001) и показало отрицательную статистическую связь с родоразрешением путем кесарева сечения (сОР: 0,53; P < 0,001) или в лечебно-диагностическом центре (сОР: 0,6; P = 0,014). Исключительно грудное вскармливание среди младенцев в возрасте до 6 месяцев показало положительную статистическую связь с родоразрешением в лечебно-диагностическом центре (сОР: 2,22; P < 0,05). Грудное вскармливание не показало статистической связи с возрастом или образованием матери, этнической принадлежностью или благосостоянием семьи. Исследованные показатели исключительного и длительного грудного вскармливания были преимущественно ниже, чем в других странах.

Вывод

Несмотря на усилия по пропаганде грудного вскармливания в Китае показатели остаются низкими. Необходимы меры по улучшению грудного вскармливания новорожденных и детей раннего возраста для сокращения уровней смертности и заболеваемости.

Introduction

In 2010, China had the world’s fifth largest number of deaths among children younger than 5 years, despite child mortality rates in the country having fallen steadily over the last two decades.1–4 Consequently, the timing and causes of death in children in China are different from those in countries where large numbers of children perish early in life. Globally, around two thirds of deaths in children younger than 5 years are caused by infection5 and an estimated 35% are associated with poor nutrition.6,7 By contrast, only 21.4% of comparable deaths in China in 2008 were infection-related: 16.5% were due to pneumonia; 3%, to diarrhoea and 1.9%, to neonatal sepsis.2 However, child mortality rates are much higher in poor western provinces, where infectious diseases are more common:2 the rate in children younger than 5 years in the poorest counties is more than six times higher than in large cities.8 Children are more likely to die from pneumonia and diarrhoea in the western part of China.2,4

Breastfeeding has been shown to reduce child mortality and morbidity, especially from infectious diseases.6,9–11 It may be possible, then, to reduce infection-associated child mortality and morbidity in poor rural areas in China by promoting good infant and young child feeding practices, particularly breastfeeding, and by discouraging the inappropriate use of breast-milk substitutes. Moreover, infant and young child feeding practices may be associated with the long-term incidence of noncommunicable diseases in both developing and developed countries, regardless of socioeconomic status.12,13 Thus, improving breastfeeding practices may help reduce the future incidence of noncommunicable diseases both in China and elsewhere.

Currently, few data are available on infant and young child feeding practices in China. The aim of this study, therefore, was to describe these practices and associated variables by surveying a large geographical area in China’s central and western provinces. Our survey was the first in the country to include the full range of globally recommended breastfeeding indicators,11 enabling comparisons to be made between China and other countries. We also examined differences in infant and young child feeding practices between China and neighbouring countries in the context of increased consumption of breast-milk substitutes and rising noncommunicable disease rates.

Methods

We conducted a community-based, cross-sectional survey of infant and young child feeding practices in 26 counties, with a total population 11 000 000, in 12 central and western provinces of China: Chongqing, Gansu, Guangxi, Guizhou, Inner Mongolia, Jiangxi, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Sichuan, Tibet and Xinjiang. The counties were selected by staff at the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the Chinese Ministry of Health as being representative of poor rural counties on the basis of their level of socioeconomic development and measures of maternal and child health. Child mortality was as high as 65 per 1000 live births in these counties, compared with a national rural average of 34 per 1000 live births in 2009, and the per capita gross domestic product ranged from 150 to 2210 United States dollars (US$), as calculated using the 2009 conversion rate from renminbi, compared with the national average of US$ 3680. The survey was conducted by Peking University School of Public Health and UNICEF staff working with local health authorities and was approved by Peking University’s ethics committee.

Data collection

A multistage sampling technique was used to select townships and villages in the 26 counties. First, all townships in each county were ranked by hospital delivery rate in 2009 and divided into three approximately equal strata; one township was then randomly selected from each stratum, except in sparsely populated Tibet, in which two townships were selected from two equal strata in each county. Within the selected townships, villages were ranked by their distance from the nearest main town and were divided into three almost equal strata; one village was then randomly selected from each stratum. Finally, approximately 20 children younger than 5 years were selected in each village. In total, 4368 children were sampled from 209 villages in 75 townships.

The overall purpose of the survey was to assess child health, perinatal care and associated demographic and socioeconomic factors in households with a child younger than 5 years. This report focuses on breastfeeding indicators, variables associated with breastfeeding, and complementary feeding among children younger than 2 years. In families with more than one child younger than 5 years, only the youngest was surveyed. Consequently, the sample was weighted towards younger children: 2577 were less than 2 years old. After excluding 330 children left behind by mothers who migrated and hence could not breastfeed them and after weighting for sampling probability, the final data set comprised 2354 children younger than 2 years (Appendix A and Appendix B, both available at: http://www.unicefchina.org/en/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=show&catid=214&id=1512).

Interviews with mothers and caregivers were conducted between July and September 2010 by local health workers trained and supervised by UNICEF and Peking University staff. Interviewers used a structured questionnaire developed from published indicators of infant and young child feeding practices (Appendix C; available at: http://www.unicefchina.org/en/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=show&catid=214&id=1512) and UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey.11,14 Child nutrition practices were assessed using 24-hour dietary recall in accordance with the relevant World Health Organization (WHO) module.15 The questionnaire was pretested and adjusted before data collection and oral informed consent was sought before each interview. The research team monitored data collection for quality control.

Survey data included demographic and socioeconomic variables for each child and mother or caregiver and information on care-seeking practices. Household wealth was categorized using the ownership of electrical appliances: poor households had 0 to 2 appliances; medium-wealth households had 3; and the least poor households had 4 or more.16–18 We also surveyed the indicators of infant and young child feeding listed in Table 1,11,14 which include early initiation of breastfeeding (i.e. within 1 hour of birth), exclusive breastfeeding among children younger than 6 months, continued breastfeeding for 1 and 2 years after birth and age-appropriate breastfeeding, as defined in Appendix C. In addition, we surveyed the early introduction of complementary feeding, defined in Appendix C as giving any soft, semisolid or solid food to an infant before the age of 6 months, regardless of breastfeeding. The rates of five indicators of infant and young child feeding observed in the survey were compared with the most recent data available on corresponding national rates in most of China’s near neighbours, as well as Brazil and South Africa.19

Table 1. Feeding practices in children younger than 2 years in 26 counties in central and western China, 2010.

| Feeding practicea | Children fed as described |

|

|---|---|---|

| No. | %b (95% CI) | |

| Breastfed at some time | 2354 | 98.3 (97.6–99.0) |

| Breastfeeding initiated early (within 1 hour of birth) | 2354 | 59.4 (54.2–64.6) |

| Exclusively breastfed (child younger than 6 months) | 490 | 28.7 (15.0–42.3) |

| Predominantly breastfed (child younger than 6 months) | 490 | 68.8 (61.8–75.1) |

| Continued breastfeeding at 1 year | 356 | 55.5 (45.2–65.8) |

| Continued breastfeeding at 2 years | 366 | 9.4 (6.0–14.4) |

| Age-appropriate breastfeeding | 2354 | 42.2 (38.7–45.8) |

| Median duration of breastfeeding, months | 2924c | 15.0 (NA) |

| Timely introduction of complementary foodsd | 419 | 89.7 (86.1–93.2) |

| Non-breastfed children (aged 6–23 months) who received at least two milk feedingse | 897 | 69.8 (64.6–75.1) |

| Early introduction of soft, semisolid or solid food | 490 | 18.7 (13.2–24.2) |

CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable.

a The feeding practice indicators are fully described in Appendix C (available at: http://www.unicefchina.org/en/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=show&catid=214&id=1512).

b Figures in this column are all percentages unless otherwise stated.

c The figure includes some older children who continued to breastfeed beyond 2 years of age.

d The recommended age for starting complementary feeding is 6 to 8 months.

e The frequency of milk feeding on the day before the survey was recorded.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using Stata 11 (StataCorp. LP, College Station, United States of America) and took into account any unequal sampling probabilities, clustering and stratification in the study design (Appendix A and Appendix B). Point estimates of indicators are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Design-based F testing was used to assess associations between the early initiation of breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding among children younger than 6 months and survey variables. Univariate analysis was performed to identify associations with these two breastfeeding indicators and crude odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were derived using the Wald test. In addition, multivariate logistic regression analysis was carried out: the initial model included fixed “a priori” variables that were assumed to be associated with the early initiation of breastfeeding or exclusive breastfeeding among children younger than 6 months and other variables that were found to be associated with breastfeeding in the univariate analysis (i.e. P ≤ 0.1). The fixed variables were retained throughout the analysis but other variables were excluded one by one according to their P-values: only those with P ≤ 0.10 were retained in the final model. The strength of each association was expressed as an adjusted OR (aOR).

Since missing data and “don’t know” answers were relatively infrequent, except for maternal age, maternal education and antenatal clinic attendance in cases where maternal information was not available, we recoded them as null values and included them in both numerators and denominators, as recommended.15

Results

Table 2 shows the demographic, socioeconomic and clinical characteristics of the 2354 children younger than 2 years included in the analysis. The male to female ratio was 1.4:1 and 53.3% were first-born children. More than a quarter were of minority ethnicity, the national minority proportion being 8.5% in 2010.20 The number of mothers younger and older than 25 years was nearly equal; only 5.7% were younger than 20 years. In addition, 71.4% had completed 9 years of education. Over 80% of mothers had attended an antenatal clinic five or more times. Among the children, 97.3% were delivered at a health-care facility and 23.8% were delivered by Caesarean section: the rate was 30.4% in county, referral-level facilities and 14.8% in first-level township hospitals (P < 0.01; data not shown).

Table 2. Social, demographic and clinical characteristics of children and caregivers surveyed in central and western China, 2010.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Children (n = 2354) | |

| Age, months | |

| < 6 | 491 (20.8) |

| 6–11 | 797 (33.9) |

| 12–17 | 522 (22.2) |

| 18–23 | 544 (23.1) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1375 (58.4) |

| Female | 979 (41.6) |

| Elder sibling | |

| Yes | 1101 (46.7) |

| No | 1254 (53.3) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Han Chinese | 1756 (74.6) |

| Minority | 598 (25.4) |

| Household wealth | |

| Poorest | 386 (16.4) |

| Medium | 780 (33.1) |

| Least poor |

1188 (50.5) |

| Mothers and caregiversa | |

| Age, years (n = 2158)a | |

| < 20 | 122 (5.7) |

| 21–25 | 913 (42.3) |

| 26–30 | 622 (28.8) |

| > 31 | 501 (23.2) |

| Maternal education (n = 2158)a | |

| None | 111 (5.2) |

| Primary school | 507 (23.5) |

| Junior school | 1338 (62.0) |

| Senior high school and above | 202 (9.4) |

| Maternal antenatal clinic visits (n = 2158)a | |

| 0–4 | 407 (18.9) |

| ≥ 5 | 1750 (81.1) |

| Place of delivery (n = 2158)a | |

| County- or higher-level hospital | 1230 (52.3) |

| Township-level hospital | 1024 (43.5) |

| Private hospital | 36 (1.5) |

| Home, clinic or other | 64 (2.7) |

| Delivery method (n = 2293)a | |

| Vaginal | 1746 (76.2) |

| Caesarean section | 547 (23.8) |

a For some children, information was available only from caregivers and, therefore, data on some maternal factors were incomplete.

Breastfeeding indicators

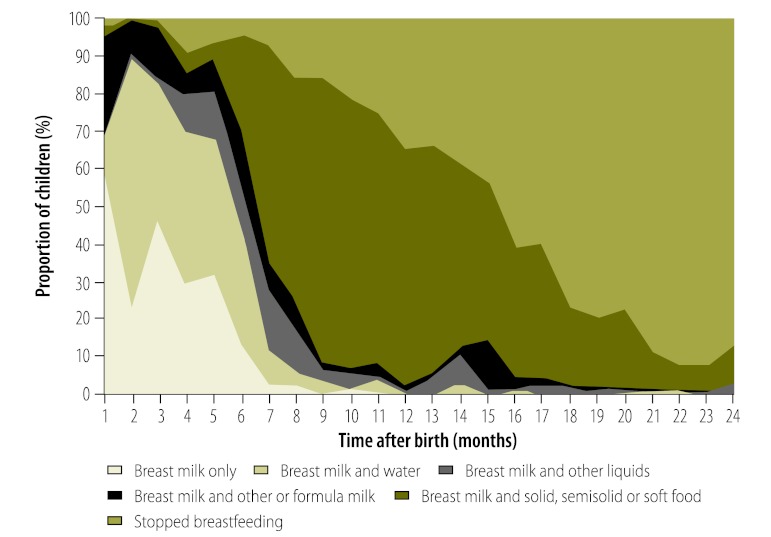

Overall, 98.3% of the infants and young children surveyed had been breastfed at some time and 59.4% of mothers had initiated breastfeeding early (e.g. within 1 hour of birth) (Table 1). The rates of exclusive breastfeeding among children younger than 6 months, continued breastfeeding at 1 and 2 years of age and age-appropriate breastfeeding were all low. Fig. 1 shows infant and young child feeding practices during the first 2 years of life. The rate of exclusive breastfeeding was only 58.3% among newborn infants (aged 0 to 27 days); it declined further to 29.1% in those aged 3 to 4 months and to 13.6% in those aged 5 to 6 months. The most common reason for non-exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months, except during the first month, was giving water. The second most common reason was using breast-milk substitutes. Around 40% of newborn infants were given something other than breast milk: 27.1% received other milk; 9.4%, water; and 3.0%, soft, semisolid or solid food (Appendix D, available at: http://www.unicefchina.org/en/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=show&catid=214&id=1512).

Fig. 1.

Feeding practices in children aged less than 2 years in 26 counties in central and western China, 2010

Generally, the introduction of complementary feeding was timely: 89.7% of infants aged 6 to 8 months, the recommended age for starting complementary feeding (Appendix C),11 had consumed soft, semisolid or solid food in the 24 hours before the survey (Table 1). However, although only 18.7% of infants younger than 6 months had commenced complementary feeding, the sharp increase from 12.2% in infants aged 4 to 5 months to 41% among those aged 5 to 6 months suggests that many started earlier than recommended.

Variables associated with breastfeeding

Table 3 presents the results of the univariate and multivariate analyses of variables associated with the early initiation of breastfeeding and Table 4, the results for exclusive breastfeeding among children younger than 6 months. Univariate analysis indicated that the early initiation of breastfeeding was positively associated with poverty, minority ethnicity and maternal attendance at an antenatal clinic five or more times, and negatively associated with Caesarean section and delivery at a county-level or private hospital (rather than a township-level hospital). Early initiation was not associated with sex, the existence of elder siblings, maternal age or maternal education. After adjustment for other variables, multivariate analysis showed that the early initiation of breastfeeding remained negatively associated with delivery at a county or higher-level referral hospital (OR: 0.6) and delivery by Caesarean section (OR: 0.53) and positively associated with attending an antenatal clinic five or more times (OR: 3.48).

Table 3. Associations between survey variables and early initiation of breastfeeding in 26 counties in central and western China, 2010.

| Variablea | No. (%) initiated breastfeeding early | Univariate analysis, cOR (95% CI) | Multivariate analysis, aOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child’s sex | |||

| Male | 816 (59.4) | 0.99 (0.77–1.28) | ND |

| Female | 583 (59.5) | 1 (NA) | ND |

| Child has elder sibling | |||

| Yes | 636 (57.8) | 0.88 (0.63–1.23) | ND |

| No | 763 (60.9) | 1 (NA) | ND |

| Maternal age, years (n = 2158) | |||

| < 25 | 660 (63.8) | 1 (NA) | ND |

| 26–30 | 370 (59.5) | 0.84 (0.64–1.09) | ND |

| > 31 | 292 (58.3) | 0.79 (0.57–1.11) | ND |

| Maternal education (n = 2158) | |||

| None or primary school | 379 (61.2) | 0.83 (0.46–1.49) | ND |

| Junior school | 811 (60.6) | 0.81 (0.48–1.36) | ND |

| Senior high school or above | 133 (65.5) | 1 (NA) | ND |

| Household wealth | |||

| Poor | 271 (70.2) | 1.6 (1.06–2.41) | 1.48 (0.92–2.39) |

| Medium | 420 (53.8) | 0.79 (0.54–1.16) | 0.77 (0.52–1.14) |

| Least poor | 708 (59.6) | 1 (NA) | 1 (NA) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Han Chinese | 999 (56.9) | 1 (NA) | 1 (NA) |

| Minority | 400 (66.8) | 1.52 (0.95–2.45) | 1.46 (0.88–2.41) |

| Place of deliveryb | |||

| County- or higher-level hospital | 659 (53.5) | 0.55 (0.39–0.77) | 0.6 (0.41–0.9) |

| Township-level hospital | 695 (67.8) | 1 (NA) | 1 (NA) |

| Private hospital, home or other | 46 (45.5) | 0.4 (0.2–0.79) | 0.57 (0.13–2.52) |

| Maternal antenatal clinic visits (n = 2158)b | |||

| 0–4 | 156 (38.4) | 1 (NA) | 1 (NA) |

| ≥ 5 | 1165 (66.6) | 3.2 (2.05–4.99) | 3.48 (2.23–5.43) |

| Delivery methodb | |||

| Caesarean section | 261 (47.7) | 0.52 (0.75–0.36) | 0.53 (0.37–0.75) |

| Vaginal | 1110 (63.6) | 1 (NA) | 1 (NA) |

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; cOR, crude odds ratio; NA, not applicable; ND, not determined.

a There were 2354 survey respondents, except where otherwise stated.

b A priori variables in the regression model.

Table 4. Associations between survey variables and exclusive breastfeeding among children aged less than 6 months in 26 counties in central and western China, 2010.

| Variablea | No. (%) aged less than 6 months and exclusively breastfed | Univariate analysis, cOR (95% CI) | Multivariate analysis, aOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child’s sex | |||

| Male | 96 (32.6) | 1.65 (1.08–2.50) | 1.66 (0.96–2.86) |

| Female | 44 (22.7) | 1 (NA) | 1 (NA) |

| Child has elder sibling | |||

| Yes | 58 (24.1) | 0.64 (0.33–1.26) | ND |

| No | 83 (33.1) | 1 (NA) | ND |

| Maternal age, years | |||

| < 25 | 79 (32.8) | 1 (NA) | ND |

| 26–30 | 34 (25.4) | 0.7 (0.28–1.72) | ND |

| > 31 | 23 (23.9) | 0.64 (0.28–1.5) | ND |

| Maternal educationb | |||

| None or primary school | 32 (27.6) | 0.44 (0.05–3.8) | 0.39 (0.07–2.19) |

| Junior school | 74 (25.5) | 0.39 (0.06–2.63) | 0.34 (0.08–1.51) |

| Senior high school or above | 30 (46.7) | 1 (NA) | 1 (NA) |

| Household wealthb | |||

| Poor | 32 (35.4) | 1.24 (0.29–5.23) | 1.24 (0.41–3.75) |

| Medium | 35 (21.9) | 0.63 (0.13–3.15) | 0.84 (0.2–3.46) |

| Least poor | 74 (30.7) | 1 (NA) | 1 (NA) |

| Ethnicityb | |||

| Han Chinese | 109 (29.6) | 1 (NA) | 1 (NA) |

| Minority | 31 (25.9) | 0.83 (0.28–2.47) | 0.65 (0.23–1.82) |

| Place of delivery | |||

| County- or higher-level hospital | 86 (38.3) | 2.32(1.23–4.38) | 2.22 (1.01–4.92) |

| Township-level hospital | 54 (21.1) | 1 (NA) | 1 (NA) |

| Private hospital, home or other | 1 (8.1) | 0.33 (0.05–2.03) | 0.44 (0.06–3.19) |

| Maternal antenatal clinic visits (n = 2158)b | |||

| 0–4 | 19 (23.5) | 1 (NA) | 1 (NA) |

| ≥ 5 | 116 (30) | 1.4 (0.49–3.95) | 1.59 (0.52–4.85) |

| Delivery method | |||

| Caesarean section | 35 (28.5) | 1 (NA) | ND |

| Vaginal | 105 (29.2) | 1.04 (0.51–2.1) | ND |

| Child’s age (change per month) b | NA | 0.75 (0.62–0.89) | 0.77 (0.64–0.94) |

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; cOR, crude odds ratio; NA, not applicable; ND, not determined.

a There were 490 survey respondents, except where otherwise stated.

b A priori variables in the regression model.

Univariate analysis indicated that exclusive breastfeeding among children younger than 6 months was associated with only three variables: there were positive associations with male sex and delivery at a county or higher-level referral hospital and a negative association with the child’s age. After adjustment for other variables, multivariate analysis showed that exclusive breastfeeding among children younger than 6 months remained positively associated with delivery at a county or higher-level referral hospital (OR: 2.22) and negatively associated with the child’s age (OR: 0.77).

Comparisons with selected countries

Table 5 shows the rates of five indicators of infant and young child feeding from our survey, from China’s most recent national survey21 and from the most recent, large-scale surveys in most of China’s neighbouring countries plus Brazil and South Africa. In our survey, breastfeeding was initiated early in 59% of infants, which is slightly above the median of 57% for Asia and 48% for the BRICS countries (i.e. Brazil, the Russian Federation, India, China and South Africa). However, both nationally and in the 12 provinces covered by this survey, exclusive breastfeeding was less common than in most other countries included in Table 5 and rates of continued breastfeeding at 12 to 15 months and 20 to 23 months were well below those in virtually all countries except Brazil, for which the rate at 12 to 15 months was lower than in our survey.

Table 5. Infant and young child feeding practices in China, neighbouring countries, Brazil and South Africa, 2003–2010.

| Country | Survey year | Initiated breastfeeding early (%) | Aged less than 6 months and exclusively breastfed (%) | Solids introduced at age 6–8 months (%) | Still breastfed at age 12–15 months (%) | Still breastfed at age 20–23 months (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China (12 provinces in present survey) | 2010 | 59 | 29 | 90 | 56 | 9 |

| China (national survey) | 2008 | 41 | 16 and 30a | 43b | 37 | ND |

| South-eastern Asia | ||||||

| Cambodia | 2010 | 65 | 74 | 82 | 83 | 43 |

| Lao People's Democratic Republic | 2006 | 30 | 26 | 70 | 82 | 48 |

| Myanmar | 2009–2010 | 76 | 24 | 81 | 91 | 65 |

| Thailand | 2009 | 50c | 15 | ND | ND | ND |

| Viet Nam | 2006 | 58 | 17 | 70 | 78 | 23 |

| South Asia | ||||||

| Bangladesh | 2007 | 43 | 43 | 74 | 95 | 91 |

| Bhutan | 2010 | 59 | 49 | 67 | 93 | 66 |

| India | 2005–2006 | 41c | 46 | 57 | 88 | 77 |

| Nepal | 2006 | 35 | 53 | 75 | 98 | 95 |

| Pakistan | 2006–2007 | 29 | 37 | 36 | 79 | 55 |

| Central and northern Asia | ||||||

| Democratic People's Republic of Korea | 2004 | 18c | 65 | 31 | 67 | 37 |

| Kazakhstan | 2006 | 64 | 17 | 39 | 57 | 16 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 2006 | 65 | 32 | 49 | 68 | 26 |

| Mongolia | 2005 | 81c | 57 | 57 | 82 | 65 |

| Tajikistan | 2004–2005 | 57c | 25 | 15 | 75 | 34 |

| Asia, median | NA | 57 | 37 | 67 | 82 | 52 |

| Other BRICSd nations | ||||||

| Brazil | 2006 | 43 | 40 | 70 | 50 | 25 |

| South Africa | 2003 | 61 | 8 | 49 | 66 | 31 |

| BRICS nations excluding China and the Russian Federation,e median | NA | 48 | 31 | 59 | 68 | 44 |

NA, not applicable; ND, not determined.

a The rate was 16% in urban areas and 30% in rural areas.

b The Chinese National Health Services Survey used an older, narrower definition of complementary feeding, which resulted in a lower figure for this measure.

c Data on the early initiation of breastfeeding were not derived from the same survey that provided data on the other four indicators. The alternative surveys were carried out in: 2009 in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea; 2007 to 2008 in India: 2008 in Mongolia; 2009 in Tajikistan; and 2005 to 2006 in Thailand.

d The BRICS nations comprise Brazil, the Russian Federation, India, China and South Africa.

e Data were not available for the Russian Federation.

Discussion

This study identified major concerns with infant and young child feeding practices in 26 poor rural counties in central and western China. The exclusive breastfeeding rate dropped precipitously during the first 6 months of life and became one of the lowest in the region. Breast-milk substitutes were frequently introduced early, followed soon after by water and non-milk liquids and, by around 4 months, various foods. The rate of continued breastfeeding at 1 year was much lower than in most neighbouring countries; the rate at 2 years was easily the lowest. Only the rate of early initiation of breastfeeding was encouraging.

We found that the rate of early initiation of breastfeeding in our rural sample was higher than in the 2008 national survey21 and we observed positive associations between early breastfeeding and attendance at an antenatal clinic and delivery in a township-level hospital, both of which suggest that the recent increase in use of these facilities in China has had additional benefits.22 The reason for the negative association between early breastfeeding and delivery at a county-level hospital may be that early breastfeeding was not prioritized in these hospitals or that the infants born in them were sicker and smaller than average or came from wealthier families who give formula early. However, our experience suggests that breast-milk substitutes are often promoted at county hospitals. The negative association between the early initiation of breastfeeding and Caesarean section, which is being performed ever more frequently in China,23 has been observed elsewhere:24 it may be related to the postoperative positioning of the mother, poor pain relief, slow lactogenesis25 or increased use of breast-milk substitutes. Spinal anaesthesia, which is in common use in China,26 should enable early breastfeeding if pain relief is adequate.

Our findings on exclusive breastfeeding are very similar to the most recent comparable data from rural China,21 particularly from Xinjiang in the far west in 2003 to 200427 and Zhejiang on the east coast in 2004 to 2005.28 Possibly because exclusive breastfeeding was infrequent after the first month, we found only one variable associated with exclusive breastfeeding among children younger than 6 months: delivery at a county-level hospital. Unlike other studies,29 ours showed no association with Caesarean section. In China, the most common reasons for ceasing exclusive breastfeeding are the perceived insufficiency of breast milk, traditional beliefs, maternal or child illness and maternal employment.27, 30–32 Marketing of breast-milk substitutes may also be a factor.33 In addition, the early introduction of complementary feeding has an ancient history in China34 and related traditional beliefs are very influential in less developed areas and in areas with large minority ethnic populations.35–37

The exclusive breastfeeding rates observed in our survey, in the 2008 national survey and in the Xinjiang and Zhejiang surveys indicate that there has been no improvement over time. This lack of progress has occurred even though, in 2007, the Chinese Ministry of Health adopted the WHO recommendation that exclusive breastfeeding should continue for 6 months38 and started using WHO’s definition of exclusive breastfeeding (previously it used the “predominant” breastfeeding indicator).11 Moreover, government policy that notionally banned the promotion of breast-milk substitutes39 has had little impact: consumption in China increased almost threefold between 2003 and 2008 and could double again by 2013,40,41 possibly due to laissez-faire regulation of breast-milk substitute advertising. There are signs, however, that educated urban women are becoming more aware of the benefits of breastfeeding.41

In 2008, it was estimated that, globally, suboptimal breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life accounted for 10 to 15% of deaths in children younger than 5 years and 10% of the disease burden.6 Moreover, the survey data we obtained show that breastfeeding practices are poor in many countries in Asia and in some large nations in other parts of the world, suggesting that there are widespread misconceptions about the benefits. Our survey showed that many infants and young children started complementary feeding early. In China, breast-milk substitutes are not of good quality and, in poor rural areas, they may be contaminated or diluted.42,43 Moreover, the weaning diet in rural China is known to be low in nutrient content.44 Poor-quality complementary feeding can increase the risk of undernutrition, infectious disease and death45 and a nutrient-poor, calorie-rich diet may be associated with a higher risk of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes in later life.12 Consequently, inappropriate infant and young child feeding in rural China places many infants at risk of early illness and death and may increase their risk of developing noncommunicable diseases. In addition to being more affordable, breastfeeding and appropriate complementary feeding could reduce the risk of noncommunicable diseases at least as effectively as mid-life dietary and lifestyle changes or drug treatment.12

Our analysis has several limitations. First, because the survey was cross-sectional, the observed associations with breastfeeding indicators may not be causal. Second, our survey participants lived in poor rural areas where the proportion of ethnic minorities was relatively high. Hence, our findings may not be generalizable to all of China. However, there is evidence that, globally, infant and young child feeding practices may be better among the poor than the rich46 and, in China, that breastfeeding is less common in urban than in rural areas.21,28 Third, since we excluded from the analysis children left behind by mothers who had migrated, our estimate of the breastfeeding rate may be higher than the true population rate. Fourth, the sampling strategy may have influenced the observed gender ratio. In rural China, families whose first born is a girl are permitted a second child and couples tend to continue having children until they have a boy. Thus, our selection of the youngest child in the household could have favoured the selection of males. Moreover, mothers may be more reluctant to register female children. The male to female ratio of 1.4:1 we observed is higher than the national average, which is 1.19:1 for infants and 1.24:1 for children aged 1 to 4 years, but it is not unusual for some rural areas.47 We considered using a life table to weight the sample but no appropriate data exist, particularly given the current high mobility of China’s rural population.

In the mid-1990s, China promoted breastfeeding by designating over 7000 hospitals “baby-friendly”. However, we recently observed that breast-milk substitutes are promoted in many of these facilities. It appears that this initiative and associated community measures had little effect on infant and young child feeding practices. In 2010, the Chinese Ministry of Health re-launched the baby-friendly hospital initiative but, unfortunately, some related activities are partly sponsored by, or involve, companies associated with breast-milk substitutes.

To prevent death and disability due to infectious diseases in childhood and to provide the best foundation for the prevention of noncommunicable diseases, China must focus on promoting breastfeeding throughout the nation. Although high- and mid-level government support is not yet widespread, some national champions are emerging.48 All sections of the community should be involved: appropriate infant and young child feeding practices should be encouraged, especially at antenatal clinics; health professionals and the community in general should be informed about the indications for, and the management of, Caesarean section; there should be strict limits on the use of breast-milk substitutes in health facilities; misconceptions about breast milk should be corrected; mothers should be advised against the early introduction of water, other liquids and complementary feeding; and exaggerated claims for the benefits of breast-milk substitutes and the promotion of substitutes by health-care workers should be actively challenged. In addition, the inappropriate marketing of breast-milk substitutes should be controlled with much stronger regulation and employers should support breastfeeding among women re-entering the workforce. Finally, the revitalised baby-friendly hospital initiative should be implemented consistently and appropriate performance indicators established.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the kind assistance of the provincial, county and township health bureaux in the surveyed locations. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and are not intended to represent the perspectives of their parent institutions.

Funding:

This research was funded by UNICEF China.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.The state of the world's children New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2012. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/sowc/ [accessed 13 February 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudan I, Chan KY, Zhang JS, Theodoratou E, Feng XL, Salomon JA, et al. WHO/UNICEF’s Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group (CHERG) Causes of deaths in children younger than 5 years in China in 2008. Lancet. 2010;375:1083–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lozano R, Lopez AD, Atkinson C, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Murray CJ, Population Health Metrics Research Consortium (PHMRC) Performance of physician-certified verbal autopsies: multisite validation study using clinical diagnostic gold standards. Popul Health Metr. 2011;9:32. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Zhu J, He C, Li X, Miao L, Liang J. Geographical disparities of infant mortality in rural China. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97:F285–90. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, Lawn JE, et al. Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of WHO and UNICEF Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet. 2012;379:2151–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, et al. Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371:243–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, Lawn JE, Rudan I, Bassani DG, et al. Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of WHO and UNICEF Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1969–87. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng XL, Guo S, Yang Q, Xu L, Zhu J, Guo Y. Regional disparities in child mortality within China 1996–2004: epidemiological profile and health care coverage. Environ Health Prev Med. 2011;16:209–16. doi: 10.1007/s12199-010-0187-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edmond KM, Zandoh C, Quigley MA, Amenga-Etego S, Owusu-Agyei S, Kirkwood BR. Delayed breastfeeding initiation increases risk of neonatal mortality. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e380–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, Cousens S, Dewey K, Giugliani E, et al. Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet. 2008;371:417–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61693-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington D.C., USA. (Part I - definitions). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horta B, Bahl R, Martines J, Victora CG. Evidence on the long-term effects of breastfeeding: systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.The World Bank Human Development Unit. Toward a healthy and harmonious life in China: stemming the rising tide of non-communicable diseases Washington: The World Bank; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.United Nations Children’s Fund [Internet]. Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys - round 4. New York: UNICEF; 2010. Available from: http://www.childinfo.org/mics4.html [accessed 13 February 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington D.C., USA. (Part II - measurement). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filmer D, Kinnon S. Assessing asset indices Washington: The World Bank; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutstein S, Johnson K. DHS comparative reports no. 6: the DHS wealth index Calverton: ORC Macro; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Shi L, Wang J, Wang Y. An infant and child feeding index is associated with child nutritional status in rural China. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:247–52. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Statistics by area: child nutrition statistical tables [Internet]. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2012. Available from: http://www.childinfo.org/breastfeeding_tables.php [accessed 21 November 2012].

- 20.National Bureau of Statistics [Internet]. Communiqué of the sixth national census data in 2010. Beijing: National Bureau of Statistics; 2011. Chinese. Available from: http://www.stats.gov.cn/zgrkpc/dlc/yw/t20110428_402722384.htm [accessed 21 February 2013].

- 21.Ministry of Health report on China's fourth national health services survey (2008). Beijing: Centre for Health Statistics and Information; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng Q, Xu L, Zhang Y, Qian J, Cai M, Xin Y, et al. Trends in access to health services and financial protection in China between 2003 and 2011: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;379:805–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng XL, Xu L, Guo Y, Ronsmans C. Factors influencing rising caesarean section rates in China between 1988 and 2008. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:30–9, 39A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.090399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chin AC, Myers L, Magnus JH. Race, education, and breastfeeding initiation in Louisiana, 2000–2004. J Hum Lact. 2008;24:175–85. doi: 10.1177/0890334408316074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang BS, Zhou LF, Zhu LP, Gao XL, Gao ES. [Prospective observational study on the effects of caesarean section on breastfeeding] Chin J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;41:246–8. Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng J. Anesthesia method in caesarean section. Lab Clin Med [Jian Yan Yi Xue Yu Lin Chuang] 2011;8:83–5. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu F, Binns C, Wu J, Yihan R, Zhao Y, Lee A. Infant feeding practices in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:198–202. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007246750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu L, Zhao Y, Binns CW, Lee AH, Xie X. A cohort study of infant feeding practices in city, suburban and rural areas in Zhejiang Province, PR China. Int Breastfeed J. 2009;4 doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang BS, Zhou LF, Zhu LP, Gao XL, Gao ES. [Prospective observational study on the effects of caesarean section on breastfeeding] Chin J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;41:246–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu F, Binns C, Yu P, Bai Y. Determinants of breastfeeding initiation in Xinjiang, PR China, 2003–2004. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:257–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gui F. Reasons for stopping breastfeeding. J North Sichuan Med Coll. 2002;17:52–3. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang H, Li M, Yang DL, Wen LM, Hunter C, He GS, et al. Awareness, intention, and needs regarding breastfeeding: findings from first-time mothers in Shanghai, China. Breastfeeding Med. 2012;7:526–34. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2011.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sobel HL, Iellamo A, Raya RR, Padilla AA, Olivé JM, Nyunt-U S. Is unimpeded marketing for breast milk substitutes responsible for the decline in breastfeeding in the Philippines? An exploratory survey and focus group analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:1445–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ping-Chen H. To nurse the young: breastfeeding and infant feeding in late Imperial China. J Fam Hist. 1995;20:217–38. doi: 10.1177/036319909502000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen N, Hu Y. Community breastfeeding survey from 1993 to 1996. China Health Edu. 1998;14:25–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han J, Li J. Breastfeeding in Xiaoshan rural areas in 1996. Zhejiang Prev Med. 1999;8:35–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang F, Xu H, Mei P. Breastfeeding status and influencing factors in four to six month old infants in Hubei province. Maternal Child Health Care China. 2000;15:624–6. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 39.On the issuance of marketing of breastmilk substitutes management approach] Beijing: State Council; 1995. Chinese. Available from: http://www.people.com.cn/item/flfgk/gwyfg/1995/236001199502.html [accessed 13 February 2013].

- 40.Global pathfinder report - baby food Ottowa: Agriculture and Agric-Food Canada; 2011.

- 41.Baby food in China London: Euromonitor International; 2012. Available from: http://www.euromonitor.com/baby-food-in-china/report [accessed 22 November 2012].

- 42.National infant formula milk powder production Beijing: General Administration of Quality Supervision Inspection and Quarantine; 2006. Chinese. Available from: http://society.people.com.cn/GB/8217/54993/54994/4832734.html [accessed 13 February 2013].

- 43.Chen JS. A worldwide food safety concern in 2008–melamine-contaminated infant formula in China caused urinary tract stone in 290,000 children in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122:243–4. doi: 10.3901/JME.2009.07.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen CM, He W, Chang SY.[Changes in the attributable factors of child growth] Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 200635765–8.Chinese [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X, Wang Y, Kang C. Feeding practices in 105 counties of rural China. Child Care Health Dev. 2005;31:417–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2005.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barros FC, Victora C, Scherpbier RW, Gwatkin D. Health and nutrition of children: equity and social determinants. In: Erik Blas E, Kurup AS, editors. Equity, social determinants and public health programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 49–76. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu WX, Lu L, Hesketh T. China’s excess males, sex selective abortion, and one child policy: analysis of data from 2005 national intercensus survey. BMJ. 2009;338:b1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.China Radio Network. Yang Lan: China's breastfeeding rate is low, less than 20% of the rate of exclusive breastfeeding 2012. Chinese. Available from: http://tv.cnr.cn/kgb/201203/t20120313_509281034.html [accessed 21 February 2013].