Abstract

Objective

To assess how changes in socioeconomic and public health determinants may have contributed to the reduction in stunting prevalence seen among Cambodian children from 2000 to 2010.

Methods

A nationally representative sample of 10 366 children younger than 5 years was obtained from pooled data of cross-sectional surveys conducted in Cambodia in 2000, 2005, and 2010. The authors used a multivariate hierarchical logistic model to examine the association between the prevalence of childhood stunting over time and certain determinants. They estimated those changes in the prevalence of stunting in 2010 that could have been achieved through further improvements in public health indicators.

Findings

Child stunting was associated with the child’s sex and age, type of birth, maternal height, maternal body mass index, previous birth intervals, number of household members, household wealth index score, access to improved sanitation facilities, presence of diarrhoea, parents’ education, maternal tobacco use and mother’s birth during the Khmer Rouge famine. The reduction in stunting prevalence during the past decade was attributable to improvements in household wealth, sanitation, parental education, birth spacing and maternal tobacco use. The prevalence of stunting would have been further reduced by scaling up the coverage of improved sanitation facilities, extending birth intervals, and eradicating maternal tobacco use.

Conclusion

Child stunting in Cambodia has decreased owing to socioeconomic development and public health improvements. Effective policy interventions for sanitation, birth spacing and maternal tobacco use, as well as equitable economic growth and education, are the keys to further improvement in child nutrition.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluer comment les changements dans les déterminants socio-économiques et de santé publique peuvent avoir contribué à la réduction de la prévalence du retard de croissance chez les enfants cambodgiens de 2000 à 2010.

Méthodes

Un échantillon national représentatif de 10 366 enfants de moins de 5 ans a été obtenu à partir de données recueillies lors d'enquêtes transversales effectuées au Cambodge en 2000, 2005 et 2010. Les auteurs ont utilisé un modèle multivarié logistique hiérarchique pour examiner l'association entre la prévalence du retard de croissance infantile au fil du temps et certains déterminants. Ils ont évalué les changements de prévalence du retard de croissance en 2010, qui auraient pu être obtenus grâce à des améliorations continues des indicateurs de santé publique.

Résultats

Le retard de croissance des enfants a été associé au sexe de l'enfant et à l'âge, au type de naissance, à la taille de la mère, à l'indice de masse corporelle de la mère, aux intervalles par rapport à la naissance précédente, au nombre de membres du foyer, au score de l'indice de richesse du ménage, à l'accès à des installations sanitaires améliorées, à la présence de diarrhées, à l'éducation des parents, au tabagisme de la mère et à la naissance de la mère pendant la famine des Khmers rouges. La réduction de la prévalence du retard de croissance au cours de la dernière décennie peut être attribuée à l'amélioration de la richesse des foyers, à la couverture santé, à l'éducation parentale, à l'espacement des naissances et à la baisse du tabagisme maternel. La prévalence du retard de croissance aurait pu être davantage réduite en intensifiant la couverture des services de santé améliorés, le rallongement des intervalles entre les naissances et l'élimination du tabagisme maternel.

Conclusion

Le retard de croissance des enfants au Cambodge a diminué en raison du développement socio-économique et de l'amélioration de la santé publique. Des interventions politiques efficaces en matière de couverture sanitaire, d'espacement des naissances et de tabagisme maternel, ainsi que la croissance économique équitable et l'éducation sont les clés d'une amélioration continue de la nutrition de l'enfant.

Resumen

Objetivo

Evaluar cómo los cambios en los factores determinantes socioeconómicos y relativos a la salud pública pueden haber contribuido en la disminución de la prevalencia del retraso en el crecimiento entre niños camboyanos observada entre 2000 y 2010.

Métodos

Se obtuvo una muestra representativa a nivel nacional de 10 366 niños menores de 5 años a partir de los datos recogidos de las encuestas transversales realizadas en Camboya en 2000, 2005 y 2010. Los autores emplearon un modelo logístico jerárquico multivariado para estudiar la relación entre la prevalencia del retraso en el crecimiento infantil en el tiempo y ciertos factores determinantes. Estimaron los cambios en la prevalencia del retraso en el crecimiento en 2010 que pudieron haberse logrado mediante las mejoras posteriores en los indicadores de salud pública.

Resultados

Se relacionó el retraso en el crecimiento del niño con los siguientes factores: el sexo y la edad del niño, el tipo de nacimiento, la altura y el índice de masa corporal de la madre, el intervalo entre partos previos, el número de miembros en el hogar, la puntuación sobre el índice de riqueza, el acceso a los servicios sanitarios mejorados, la presencia de diarrea, la educación de los progenitores, el tabaquismo materno, así como el nacimiento de la madre durante la hambruna de Khmer Rouge. La disminución de la prevalencia del retraso en el crecimiento en la última década se atribuyó a las mejoras en: la economía familiar, la sanidad, la educación de los progenitores, el espaciamiento entre partos, así como el tabaquismo materno. La prevalencia del retraso en el crecimiento podría haberse reducido más mediante la ampliación de la cobertura de servicios mejorados, el aumento de los intervalos entre partos y la erradicación del consumo de tabaco por parte de la madre.

Conclusión

El retraso en el crecimiento entre niños de Camboya ha disminuido gracias al desarrollo socioeconómico y a las mejoras en la salud pública. Las intervenciones políticas efectivas, el espaciamiento entre partos, el tabaquismo materno, así como la igualdad tanto en la educación como en el crecimiento económico son los factores clave para que la nutrición infantil continúe mejorando.

ملخص

الغرض

تقييم مدى إسهام التغيرات في المحددات الاجتماعية والاقتصادية ومحددات الصحة العمومية في خفض انتشار التقزم الذي لوحظ بين الأطفال في كمبوديا في الفترة من 2000 إلى 2010.

الطريقة

تم الحصول على عينة تمثيلية على الصعيد الوطني تتألف من 10366 طفلاً تقل أعمارهم عن 5 سنوات من البيانات المجمعة للدراسات الاستقصائية متعددة القطاعات التي أجريت في كمبوديا في أعوام 2000 و2005 و2010. واستخدم المؤلفون نموذجاً لوجيستياً هرمياً متعدد المتغيرات لدراسة العلاقة بين انتشار التقزم في مرحلة الطفولة على مدار الوقت وبعض المحددات. وقاموا بتقييم دور تلك التغيرات في انتشار التقزم في عام 2010 التي كان من الممكن تحقيقها من خلال مواصلة التحسينات في مؤشرات الصحة العمومية.

النتائج

ارتبط تقزم الأطفال بجنس الطفل وعمره ونمط الولادة وطول الأم ومنسب كتلة الجسم للأم والفترات الفاصلة بين الولادات السابقة وعدد أفراد الأسرة ودرجة مؤشر الثروة للأسرة وإتاحة مرافق الإصحاح المحسنة ووجود الإسهال وتثقيف الوالدين وتعاطي الأم للتبغ وولادة الأم أثناء فترة مجاعة الخمير الحمر. ويُعزى الانخفاض في انتشار التقزم خلال العقد المنصرم إلى التحسينات في ثروة الأسرة والإصحاح وتثقيف الوالدين والمباعدة بين الولادات وتعاطي الأم للتبغ. ويمكن زيادة خفض انتشار التقزم من خلال تعجيل تغطية مرافق الإصحاح المحسنة وإطالة الفترات الفاصلة بين الولادات واستئصال تعاطي الأم للتبغ.

الاستنتاج

انخفض تقزم الأطفال في كمبوديا بفضل التنمية الاجتماعية والاقتصادية والتحسينات التي شهدتها الصحة العمومية. وكانت التدخلات السياسية الفعالة من أجل الإصحاح والمباعدة بين الولادات وتعاطي الأم للتبغ بالإضافة إلى العدالة في النمو الاقتصادي والتعليم العناصر الرئيسية لمواصلة التحسينات في مجال تغذية الطفل.

摘要

目的

评估社会经济和公众健康决定因素的变化对降低2000 至2010 年柬埔寨儿童发育迟缓发病率可能有何种贡献。

方法

从2000、2005 年和2010 年进行的横断面调查的汇总数据中获取未满5 岁的10366 名儿童的全国代表性样本。作者采用多元层次逻辑模型考查儿童发育迟缓发病率与时间以及某些决定因素之间的关联。他们对在2010 年通过进一步改善公众健康指标可能实现的发育障碍发病率的变化进行估计。

结果

儿童发育迟缓的相关因素有:儿童的性别和年龄、出生类型、产妇身高、产妇身体质量指标、之前的出生时间间隔、家庭成员人数、家庭财富指数得分、卫生设施更好的普及、出现腹泻情况、父母的教育程度、孕产妇吸烟与否以及母亲是否出生在红色高棉饥荒期间。在过去的十年中,发育迟缓发病率减少得益于家庭财富、卫生、父母教育程度、生育间隔和产妇吸烟方面的改善。通过逐步扩大改进的卫生设施的覆盖范围、延长生育间隔并根除产妇吸烟,可进一步降低发育迟缓的发病率。

结论

由于社会经济的发展和公共健康的改善,柬埔寨的儿童发育迟缓发病率下降。环境卫生、生育间隔和产妇吸烟的有效政策干预措施以及公平的经济增长和教育是进一步改善儿童营养的关键所在。

Резюме

Цель

Оценить, как изменения в социально-экономической и общественной детерминантах здоровья способствовали сокращению отставания в росте, наблюдаемого среди камбоджийских детей с 2000 по 2010 годы.

Методы

Из объединенных данных перекрестных опросов, проведенных в Камбодже в 2000, 2005 и 2010 годах, были получены данные национальной репрезентативной выборки из 10 366 детей в возрасте до 5 лет. Авторы использовали многомерную иерархическую логистическую модель для изучения распространенности задержки роста у детей с течением времени и в зависимости от определенных детерминант. Они оценили изменения в распространенности задержки роста детей в 2010 г., которые могли быть достигнуты за счет улучшения показателей здоровья населения.

Результаты

При анализе отставания ребенка в росте рассматривались такие параметры, как пол и возраст ребенка, тип рождения, рост и индекс массы тела матери, предыдущие интервалы между родами, количество членов семьи, уровень благосостояния домохозяйства, наличие улучшенных санитарных условий, наличие диареи, образование родителей, употребление матерью табака и рождение матери во время голода при восстании «Красных кхмеров». Сокращение задержки в росте в течение последнего десятилетия было связано с улучшениями в сфере благосостояния домашних хозяйств, санитарных условий, образования родителей, интервала между родами и снижения употребления табака матерями. Распространенность задержки в росте можно еще более сократить путем расширенного охвата улучшенными средствами санитарии, увеличения интервалов между родами и искоренения употребления табака матерями.

Вывод

Распространенность задержки роста у детей в Камбодже снизилась вследствие социально-экономического развития и улучшения общественного здравоохранения. Эффективные меры в области санитарии, увеличение интервала между родами и сокращение употребления табака матерями, а также равный доступ к возможностям экономического роста и образования являются ключевыми условиями для обеспечения дальнейшего улучшения питания детей.

Introduction

Improving the nutritional status of children is a priority in child health. The global burden of undernutrition among children is enormous. Worldwide, more than 300 million children younger than 5 years are estimated to be chronically undernourished.1 Nutritional insufficiency is one of the most important factors contributing to illness among children in the world. In 2010, it accounted for 3.4% of the total global burden of disease.2 To reduce the burden of child undernutrition, it is important to implement appropriate policies and interventions targeting determinants such as education, economic status and empowerment of women.3

Cambodia has experienced rapid socioeconomic development during its democratic transition towards an open market economy since the international peace agreements were signed in 1991.4 Driven by strong economic activity in a period of peace and political stability, the country’s gross domestic product grew by an annual average of 9% during the 2000s5 and was continuing to grow by more than 6% annually in the early 2010s.6 However, nearly one third of the population still lives below the poverty line5 and many children suffer from hunger and poor health. Although mortality among Cambodian children under 5 years of age decreased at an accelerated rate during the 2000s, the decrease is not sufficient to achieve Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 4, which calls for a two-third reduction from 1990 to 2015.7 The nutritional status of Cambodian children has been one of the poorest in the world since at least the mid-1980s.1 Cambodia is not likely to meet MDG 1, which seeks to halve the proportion of people experiencing hunger,1 even though the prevalence of stunting among children younger than 5 years dropped from 50% in 2000 to 40% in 2010.8

Stunting is generally used as an indicator of long-term chronic nutritional deficiency. Child stunting has been extensively studied in developing countries, including Bangladesh,9 Brazil,10 Indonesia,9 Kenya11 and Mozambique.12 In Cambodia, several studies have analysed data from the Cambodian Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) conducted in 2000 and 2005 to explore the factors influencing child stunting. These studies have shown stunting was more common among Cambodian children who lived in poorer households,13 or whose mothers had little education14 or smoked tobacco.15 Another study also showed the absence of an association between child stunting among Cambodian children and mothers’ compliance with recommended breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices.16 However, no study has extended the analysis to include the Cambodian 2010 DHS, which covers data for the period of rapid economic growth, or examined how certain potential contributing factors may have affected the decline in stunting prevalence.

The present study aimed to explore what measures will further reduce child stunting in Cambodia, where many people still live in poverty despite rapid economic growth. Using pooled data from three Cambodian DHSs conducted in the period from 2000 to 2010, we investigated improvements in child stunting over the past decade to highlight areas in which effective policy intervention could further reduce stunting prevalence. This information will help policy-makers to organize effective programmes across various sectors to accelerate improvements in the nutrition and health of children in Cambodia.

Methods

Data sources

We pooled data for children less than 5 years of age from the Cambodian DHS conducted in 2000, 2005 and 2010. In each survey, a nationally representative sample of households was obtained through multistage cluster sampling. The methods were detailed elsewhere.8,17,18 To summarize, in 2000 the sampling frame was 600 villages; in 2005 it was all of Cambodia’s 13 505 villages and in 2010 it was 28 764 enumeration areas. Provinces and groups of provinces were stratified into urban and rural areas. In the first stage, villages or census enumeration areas were selected, and, in 2000, a fixed number of segments or enumeration areas were further retained from each of the selected villages. Subsequently, a fixed number of households was selected from each of the selected clusters. All women of reproductive age (15–49 years) who were members of a sampled household or who had slept there the night before the survey were eligible for an interview. The DHS collected anthropometric data for women and for all children younger than 5 years from a 50% subsample of households. Trained personnel measured the recumbent length of children aged less than 24 months and the standing height of older children.8,17,18 Children were included in the study if they had no missing values for anthropometric measurements or other relevant variables. The final sample was composed of 10 366 children (3395 in 2000, 3418 in 2005 and 3553 in 2010).

To assess the chronic nutritional status of children, we used height-for-age z-scores following the Child Growth Standards of the World Health Organization (WHO).19 The height-for-age z-score, as defined by WHO, expresses a child’s height in terms of the number of standard deviations above or below the median height of healthy children in the same age group or in a reference group. We classified children as being stunted if they had a height-for-age z-score of less than −2.

Statistical analysis

To explore factors that may have contributed to the reduction in child stunting during the past 10 years, we conducted a two-step analysis: (i) we examined the association between stunting in individual children and various socioeconomic characteristics and public health determinants, and (ii) we quantified the extent to which a change in each associated determinant decreased the prevalence of child stunting.

In the first part of the analysis, we used multivariate hierarchical logistic regression to model the stunting of children as a function of their socioeconomic characteristics. In this pooled analysis, we included survey year as a fixed effect and adjusted for any correlation among mothers having several children because 41.3% of the sample had siblings aged less than 5 years. We used only covariates that could be consistently measured across the three surveys, which were: the child’s sex; the child’s age in months (continuous variable); type of birth (single or multiple); initiation of breastfeeding within 1 hour of birth (dichotomous variable); preceding birth interval; maternal height (in centimeters squared); maternal body mass index (a proxy for maternal nutritional status); maternal and paternal educational level; maternal use of tobacco at the time of the survey (dichotomous variable); type of residence (urban or rural); number of household members; household wealth status score; access to improved sources of water during the rainy season; access to improved sanitation facilities; the occurrence of diarrhoea in the two weeks preceding the survey; and mother’s birth during the 1975–1978 Khmer Rouge regime (as an indicator variable). In constructing the indicators on water and sanitation, we followed the classifications proposed by the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation (run by WHO and the United Nation’s Children Fund).20 The wealth index scores originally provided by the Cambodian DHS were estimated separately and were not comparable across survey years. Therefore, to compute household wealth index scores on a single common scale across surveys, we pooled data sets for 42 077 households (12 195 in 2000, 14 224 in 2005 and 15 658 in 2010) and conducted a principal component analysis on household possession of 12 durable assets and housing materials.

To measure the relative contribution of different factors to the decline in the prevalence of child stunting between 2000 and 2010, we computed a base value for stunting prevalence by using β coefficients estimated from the regression and the mean values of the explanatory variables in 2000. We then changed the value of each variable to its mean in 2010 while keeping all other covariates constant at their 2000 mean levels. We took any difference from the base value to be the effect of each factor on stunting prevalence. The contributions were not mutually exclusive across factors because the change in means over time could be correlated, particularly with wealth. We used the same approach to estimate the changes in the stunting prevalence in 2010 that would have been achieved by counterfactual improvements in socioeconomic status and public health, as represented by sanitation, spacing between births, smoking prevalence, infection and maternal nutrition. We took into account the complex sampling method (i.e. stratification, clustering and sample weights) in estimating summary statistics for the variables at the population level. We used Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, United States of America) for all statistical analyses.

Results

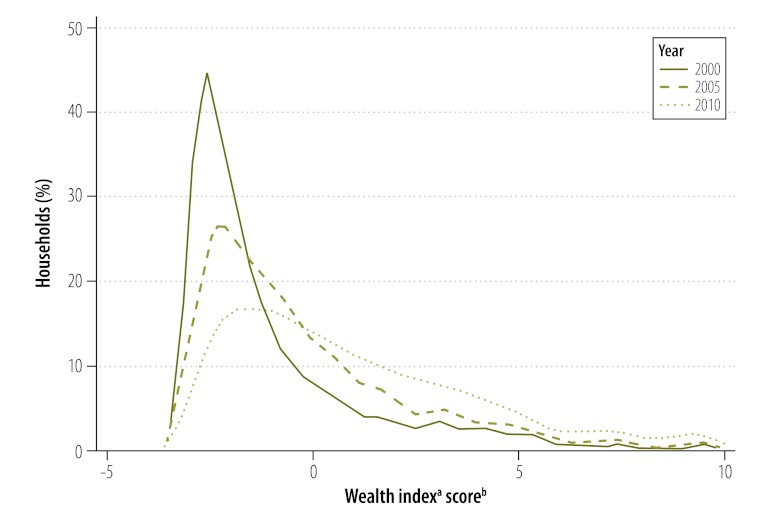

The prevalence of stunting in the study population decreased from 49.3% (95% confidence interval, CI: 47.1–51.5) in 2000 to 39.0% (95% CI: 36.7–41.2) in 2010. Broken down by age group, in 2000 the stunting prevalence was 35.6% (95% CI: 32.7–38.7) among children aged 0–23 months and 57.8% (95% CI: 55.1–60.5) among those aged 24–59 months; in 2010 it was 27.5% (95% CI: 24.7–30.4) and 46.7% (95% CI: 43.8–49.6), respectively. Table 1 lists the point estimates and 95% CIs for the explanatory variables at the national level by survey year. A substantial increase was observed in several public health variables, including early initiation of breastfeeding, improved sources of drinking water and improved sanitation facilities. Fig. 1 illustrates trends in the distribution of household wealth index scores across survey years. The fraction of wealthier households increased over time, while the distribution was still skewed to the right, with the majority of households below the mean value and a long tail at the higher end of the distribution in 2010.

Table 1. Characteristics of children included in the analysis, by year, based on data obtained from the Cambodia Demographic and Health Surveys of 2000, 2005 and 2010.

| Characteristic | Value (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 (n = 3395) | 2005 (n = 3418) | 2010 (n = 3553) | |

| Male sex (%) | 51.2 (49.1–53.3) | 48.8 (46.7–51.0) | 51.3 (49.2–53.4) |

| Age (months) | 29.9 (29.3–30.5) | 29.6 (28.9–30.2) | 29.5 (28.9–30.1) |

| Rural residence (%) | 85.6 (84.2–86.9) | 86.4 (84.2–88.4) | 84.5 (82.7–86.0) |

| Multiple birth (%) | 1.6 (1.0–2.4) | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 0.9 (0.6–1.6) |

| Breastfed within 1 hour of birth (%) | 10.6 (9.3–12.0) | 36.6 (34.3–39.0) | 64.4 (61.8–67.0) |

| Preceding birth interval (%) | |||

| None (first birth) | 18.6 (17.1–20.3) | 26.9 (25.1–28.7) | 34.0 (32.0–36.0) |

| < 18 months | 5.5 (4.7–6.4) | 4.9 (4.1–5.7) | 3.8 (3.1–4.7) |

| 18–23 months | 10.1 (9.1–11.3) | 8.2 (7.1–9.4) | 6.4 (5.4–7.5) |

| 24–29 months | 15.3 (14.1–16.7) | 11.0 (9.9–12.2) | 9.4 (8.2–10.7) |

| 30–35 months | 12.4 (11.2–13.7) | 10.6 (9.4–12.0) | 7.6 (6.4–8.9) |

| ≥ 36 months | 38.1 (36.0–40.1) | 38.5 (36.4–40.6) | 38.9 (36.7–41.0) |

| Average no. of household members | 6.3 (6.2–6.4) | 5.8 (5.7–6.0) | 5.7 (5.6–5.8) |

| Improved drinking water source in dry season (%) | 41.1 (37.5–44.7) | 71.0 (67.8–74.1) | 75.4 (72.0–78.5) |

| Improved sanitation facility (%) | 4.5 (3.6–5.6) | 16.5 (14.3–19.0) | 28.6 (26.0–31.3) |

| Diarrhoea in past 2 weeks (%) | 20.4 (18.6–22.4) | 19.3 (17.4–21.3) | 15.7 (13.9–17.7) |

| Paternal education (%) | |||

| None | 17.6 (15.5–19.8) | 14.6 (12.6–16.8) | 11.3 (9.7–13.1) |

| Incomplete primary | 42.9 (40.4–45.4) | 42.9 (40.4–45.3) | 37.5 (35.1–39.9) |

| Complete primary | 7.9 (6.7–9.3) | 7.3 (6.0–8.8) | 8.4 (7.0–10.0) |

| Incomplete secondary | 30.8 (28.3–33.3) | 29.7 (27.3–32.2) | 34.0 (31.6–36.6) |

| Complete secondary or higher | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 5.6 (4.5–6.9) | 8.8 (7.5–10.2) |

| Maternal education (%) | |||

| None | 32.4 (29.9–34.9) | 23.8 (21.5–26.3) | 18.9 (16.7–21.2) |

| Incomplete primary | 49.5 (46.9–52.2) | 51.8 (49.2–54.4) | 47.5 (44.8–50.2) |

| Complete primary | 4.2 (3.3–5.3) | 6.8 (5.7–8.1) | 9.1 (7.6–10.9) |

| Incomplete secondary | 13.1 (11.4–15.0) | 15.7 (13.6–18.0) | 20.8 (18.7–23.2) |

| Complete secondary or higher | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 1.9 (1.2–3.0) | 3.7 (2.8–4.8) |

| Maternal use of tobaccoa (%) | 14.3 (12.4–16.5) | 12.4 (10.6–14.4) | 6.6 (5.1–8.4) |

| Maternal height (cm) | 153.1 (152.8–153.3) | 152.6 (152.3–152.8) | 152.7 (152.4–153.0) |

| Maternal BMI (%) | |||

| < 18.5 kg/m2 | 19.9 (18.0–21.9) | 19.4 (17.4–21.5) | 17.8 (16.1–19.6) |

| 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 74.9 (72.9–76.9) | 72.5 (70.0–74.8) | 72.7 (70.4–74.8) |

| ≥ 25.0 kg/m2 | 5.2 (4.3–6.4) | 8.1 (6.8–9.7) | 9.5 (8.2–11.1) |

| Mother born in 1975–1978 (%) | 12.3 (10.8–14.0) | 15.8 (14.1–17.6) | 9.3 (8.0–10.8) |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval.

a At the time of the survey.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of household wealth index scores, by year, estimated from Cambodian Demographic and Health Survey data for 2000, 2005 and 2010

a The index value is the first component score estimated from the principal component analysis of wealth indicators. It has a mean of 0 across the three surveys and equals the sum of values for standardized asset indicators, weighted by first factor coefficient scores.35

b The assets used to estimate the wealth index scores were main material of the floor and roof, main fuel used for cooking, electricity, radio, television, refrigerator, bicycle, motorcycle, car, wardrobe and boat with a motor.

After adjustment for other confounding factors, child stunting showed a statistically significant association with a child’s sex and age, type of birth, maternal height, a maternal body mass index of < 18.5 kg/m2, preceding birth interval (except for firstborn children), number of household members, household wealth index scores, improved sanitation facilities, maternal and paternal educational level, maternal use of tobacco at the time of the survey, episode of diarrhoea in the child in the two weeks immediately before the survey, and mother’s birth during the Khmer Rouge regime (Table 2).

Table 2. Variables associated with child stunting, based on data from the Cambodian Demographic and Health Surveys of 2000, 2005 and 2010.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 1.1057 (1.0122–1.2078) |

| Female | 1 |

| Age (months) | 1.0307 (1.0278–1.0336) |

| Residence | |

| Urban | 1 |

| Rural | 0.9212 (0.7916–1.0719) |

| Type of birth | |

| Single | 1 |

| Multiple | 1.9075 (1.2865–2.8283) |

| Breastfeeding initiation | |

| < 1 hour of birth | 0.9587 (0.8612–1.0672) |

| ≥ 1 hour after birth | 1 |

| Preceding birth interval | |

| None (first birth) | 1.0677 (0.9495–1.2006) |

| < 18 months | 1.4763 (1.2031–1.8117) |

| 18–23 months | 1.4272 (1.2109–1.6821) |

| 24–29 months | 1.3103 (1.1341–1.5139) |

| 30–35 months | 1.1931 (1.0196–1.3962) |

| ≥ 36 months | 1 |

| Household wealth index score | 0.9040a (0.8768–0.9321) |

| No. of household members | 1.0286b (1.0067–1.0509) |

| Drinking water source in dry season | |

| Not improved | 1 |

| Improved | 1.0341 (0.9318–1.1476) |

| Sanitation facility | |

| Not improved | 1 |

| Improved | 0.8145 (0.6902–0.9612) |

| Diarrhoea in past 2 weeks | |

| No | 1 |

| Yes | 1.2209 (1.0857–1.3731) |

| Paternal education | |

| None | 1.5865 (1.1764–2.1396) |

| Incomplete primary | 1.6730 (1.2678–2.2076) |

| Complete primary | 1.5575 (1.1430–2.1222) |

| Incomplete secondary | 1.4380 (1.1028–1.8750) |

| Complete secondary or higher | 1 |

| Maternal education | |

| None | 2.0173 (1.2795–3.1803) |

| Incomplete primary | 1.8252 (1.1691–2.8497) |

| Complete primary | 1.9221 (1.2028–3.0715) |

| Incomplete secondary | 1.8579 (1.1966–2.8845) |

| Complete secondary or higher | 1 |

| Maternal use of tobaccoc | |

| No | 1 |

| Yes | 1.2607 (1.0936–1.4532) |

| Maternal height | 1.0471 (1.0353–1.0591) |

| Maternal height squared | 0.9996 (0.9995–0.9997) |

| Maternal body mass index | |

| < 18.5 kg/m2 | 1.2283 (1.0924–1.3811) |

| 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 1 |

| ≥ 25.0 kg/m2 | 0.8468 (0.7105–1.0092) |

| Maternal birth cohort | |

| 1975–1978d | 1.1683 (1.0212–1.3365) |

| Other years | 1 |

| Survey year | |

| 2000 | 1.0863 (0.8996–1.3117) |

| 2005 | 0.9437 (0.7910–1.1259) |

| 2010 | 1 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

a A 1-point increase in household wealth index scores results in a 10% decrease in the odds of stunting.

b A 1-person increase in the number of household members results in a 3% increase in the odds of stunting.

c At the time of the survey.

d Period of the Khmer Rouge regime.

Table 3 shows the extent to which various factors contributed to the decrease in child stunting prevalence between 2000 and 2010. Of all the independent variables included in the model, increased household wealth index score was the one that made the largest contribution, followed by increased access to improved sanitation facilities, improved maternal and paternal educational level, longer interval between preceding birth and birth of surveyed child and decreased prevalence of maternal tobacco use.

Table 3. Estimated contribution of each explanatory variable, in percentage points, to the stunting prevalence among children younger than 5 years from 2000 to 2010, based on data from the Cambodian Demographic and Health Surveys of 2000–2010.

| Explanatory variable | Contributiona (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Increased household wealth index score | −4.34 (−5.68 to −2.97) |

| Improved sanitation facilities | −1.23 (−2.24 to −0.29) |

| Improved paternal education | −1.06 (−1.66 to −0.49) |

| Longer preceding birth interval | −0.86 (−1.33 to −0.38) |

| Improved maternal education | −0.67 (−1.33 to −0.04) |

| Decreased prevalence of maternal use of tobacco | −0.45 (−0.73 to −0.17) |

| Decreased average no. of household members | −0.42 (−0.75 to −0.09) |

| Increased average maternal BMI | −0.29 (−0.47 to −0.10) |

| Decreased incidence of diarrhoea in past 2 weeks | −0.24 (−0.38 to −0.10) |

| Decrease in multiple births | −0.10 (−0.17 to −0.04) |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval.

a Negative values indicate a contribution towards a decreased rate.

The prevalence of child stunting in 2010 would have been 3.4 percentage points (95% CI: 0.8–6.1) higher if the coverage of improved sanitation facilities had extended to all households; 1.8 percentage points (95% CI: 1.1–2.4) higher if the interval between the birth of every surveyed child and that of the preceding child had been at least 36 months, and 0.4 percentage points (95% CI: 0.1–0.6) if maternal tobacco use had been eradicated.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify the contribution made by various factors to the decrease in the prevalence of stunting among Cambodian children less than 5 years of age during the 2000s, a period of peace and rapid economic growth. We found that increased household wealth made the largest contribution, followed by improvements in sanitation facilities, parental education and birth spacing and by a decrease in maternal tobacco use.

It is widely accepted that when economies grow and poverty is reduced, child nutrition improves owing to greater access to food, improved maternal and child care and better public health services.21 However, the evidence surrounding the relationship between improvements in the economy and childhood nutrition is inconclusive.22,23 Findings have been heterogeneous, perhaps because of differences in study design and unobserved confounders, such as the policies and circumstances that exist in individual countries. In this regard, our study contributes to the evidence that economic growth exerts a positive influence on child nutrition. It also points to what previous studies have shown, namely, that economic development alone is not enough to improve the nutritional status of children. Equitable income allocation and investment in public health and education programmes are needed to promote a nourishing diet and to keep children healthy.1,22,23 In our study, substantial economic disparity between households was observed: a large fraction of households ranked low on the nationwide wealth scale. Equitable economic growth is needed to attain sustained reductions in the prevalence of child stunting in Cambodia.

The other major determinants in our model contributed in approximately equal measure to the reduction in stunting prevalence. The rate of access to improved sanitation facilities increased from less than 10% to more than 25% between 2000 and 2010. This affected the prevalence of stunting, particularly among children aged 24–59 months (results not shown), perhaps because hygienic toilets prevent young children growing out of diapers from coming into contact with faeces and hence reduce the risk of infections transmitted by the faecal-oral route. 24-26 Since more than 70% of Cambodian children still live in households without improved sanitary facilities, strengthening strategies to increase the provision of hygienic toilets is essential for the health of preschool children.

Although formal education has improved gradually in Cambodia, there is substantial room for further advances which would in turn lead to further reductions in child stunting. Currently, most parents of children under 5 years of age in Cambodia have never enrolled in secondary education. Our finding of an association between maternal and paternal educational level and childhood stunting is consistent with the results of other studies conducted in developing countries, including Cambodia.9,12-14 Moreover, our additional analyses suggest that maternal educational level is inversely associated with stunting in children aged 24–59 months (results not shown). Educated parents may be better equipped to offer their children good care than parents of low educational attainment. It is important that the Cambodian government pursue policies aimed at improving access to education among the poor in Cambodia.

According to our findings, an increase in preceding birth interval made a modest contribution to the decreased prevalence of stunting in Cambodian children. The progress observed in birth spacing in Cambodia is reflected in the substantial decline in child mortality in the country during the past 10 years. A short interval between births can have an adverse effect on child nutrition by causing intrauterine growth retardation or undermining the quality of child care.27

A reduction in the maternal use of tobacco also made a small contribution to the drop in stunting prevalence in Cambodia in the past decade. In our study, maternal smoking and tobacco chewing was significantly associated with child stunting at the individual level, as shown by previous studies in developing countries.9,15,28 The use of tobacco can cause growth retardation in utero29 and divert money away from food and towards tobacco, particularly among the poor.30 Child growth in Cambodia can be improved by increasing public awareness about the dangers of tobacco use and implementing interventions to combat the notion, propagated primarily by older women smokers, that smoking reduces stress during pregnancy.31

Like previous studies in developing countries, ours detected an association between maternal height and child stunting.32,33 Short maternal stature is associated with intrauterine growth retardation and low birth weight, which are in turn predictors of infant death and impaired child growth.2 Moreover, birth of the mother during the Khmer Rouge famine of 1975–1978 also showed a positive association with stunting in the offspring. This suggests the presence of a transgenerational link in which exposure to hunger during the Khmer Rouge regime influences a mother’s stature, which predicts, in turn, the growth of her child. A previous study also showed that intrauterine exposure to the Dutch famine of 1944–1945 was associated with shorter offspring length at birth.34 Further research is needed to explore the life-course effects on child growth of maternal exposure in utero to risk factors present during the Cambodian famine.

The present study has several limitations. First, it did not address causal effects, since it was based on data from cross-sectional surveys. Second, children who died before the survey were not included in the sample, although some may have been severely undernourished. Third, a few key variables could not be included in the model because of differences in survey design and questions. For example, exclusive breastfeeding was excluded from the model because, since the Cambodian DHS only includes questions about current breastfeeding, no information on the early diet of children older than 6 months was available. However, our subgroup analysis of children younger than 6 months suggests the absence of a statistically significant association exists between exclusive breastfeeding and early postnatal stunting (results not shown). This is consistent with previous findings.16 Similarly, we were unable to include complementary feeding status in the model because the list of food items was different across the surveys. However, our sub-group analysis in children aged 6–23 months suggests that less frequent feedings are not associated with stunting (results not shown). Acute respiratory infection was also excluded from our model because the 2000 DHS included no question about the presence of a cough in connection with a respiratory problem. Although these variables were missing from the analysis, our model did consider all those covariates linked to child stunting that were treated homogeneously across the three surveys.

In conclusion, the decrease in the prevalence of stunting among Cambodian children between 2000 and 2010 was partly attributable to improvements in household wealth and in some public health measures. Further reductions in the prevalence of child stunting could be attained through more equitable economic growth, greater access to hygienic toilets and improved educational opportunities. Interventions addressing birth spacing and tobacco use are also needed. Policy-makers need to prioritize these measures and effectively coordinate multisectoral programmes to improve the diet of Cambodian children.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by the Grant-In-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, grant number H21-Chikyukibo-Ippan-002.

Yuki Irie and Nayu Ikeda contributed equally to the authorship of this paper.Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Stevens GA, Finucane MM, Paciorek CJ, Flaxman SR, White RA, Donner AJ, et al. Nutrition Impact Model Study Group (Child Growth) Trends in mild, moderate, and severe stunting and underweight, and progress towards MDG 1 in 141 developing countries: a systematic analysis of population representative data. Lancet. 2012;380:824–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60647-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, Cousens S, Dewey K, Giugliani E, et al. Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet. 2008;371:417–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61693-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharing growth: equity and development in Cambodia Washington: The World Bank; 2007. Available from: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTCAMBODIA/Resources/293755-1181597206916/E&D_Full-Report.pdf [accessed 12 February 2013].

- 5.World development indicators 2012 Washington: The World Bank; 2012. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/news/world-development-indicators-2012-now-available [accessed 12 February 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World dataBank [Internet]. Washington: The World Bank; 2013. Available from: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/home.aspx [accessed 12 February 2013].

- 7.Lozano R, Wang H, Foreman KJ, Rajaratnam JK, Naghavi M, Marcus JR, et al. Progress towards Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 on maternal and child mortality: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;378:1139–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61337-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Phnom Penh & Calverton: National Institute of Statistics & ICF Macro; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semba RD, de Pee S, Sun K, Sari M, Akhter N, Bloem MW. Effect of parental formal education on risk of child stunting in Indonesia and Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2008;371:322–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monteiro CA, Benicio MH, Conde WL, Konno S, Lovadino AL, Barros AJD, et al. Narrowing socioeconomic inequality in child stunting: the Brazilian experience, 1974–2007. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:305–11. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.069195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masibo PK, Makoka D. Trends and determinants of undernutrition among young Kenyan children: Kenya Demographic and Health Survey; 1993, 1998, 2003 and 2008–2009. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:1715–27. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012002856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burchi F. Child nutrition in Mozambique in 2003: the role of mother’s schooling and nutrition knowledge. Econ Hum Biol. 2010;8:331–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong R, Mishra V. Effect of wealth inequality on chronic under-nutrition in Cambodian children. J Health Popul Nutr. 2006;24:89–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller JE, Rodgers YV. Mother's education and children's nutritional status: new evidence from Cambodia. Asian Dev Rev. 2009;26:131–65. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kyu HH, Georgiades K, Boyle MH. Maternal smoking, biofuel smoke exposure and child height-for-age in seven developing countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1342–50. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marriott BP, White AJ, Hadden L, Davies JC, Wallingford JC. How well are infant and young child World Health Organization (WHO) feeding indicators associated with growth outcomes? An example from Cambodia. Matern Child Nutr. 2010;6:358–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Phnom Penh & Calverton: National Institute of Statistics & ICF Macro; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey 2000. Phnom Penh & Calverton: National Institute of Statistics & ICF Macro; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO Child Growth Standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: methods and development Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Progress on drinking water and sanitation: 2012 update New York: United Nations Children’s Fund & World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith Lisa C, Haddad L. How potent is economic growth in reducing undernutrition? What are the pathways of impact? New cross-country evidence. Econ Dev Cult Change. 2002;51:55–76. doi: 10.1086/345313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haddad L, Alderman H, Appleton S, Song L, Yohannes Y. Reducing child malnutrition: How far does income growth take us? World Bank Econ Rev. 2003;17:107–31. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhg012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subramanyam MA, Kawachi I, Berkman LF, Subramanian SV. Is economic growth associated with reduction in child undernutrition in India? PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Water, sanitation & hygiene: strategy overview Seattle: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; 2012. Available from: http://www.gatesfoundation.org/watersanitationhygiene/Documents/wsh-strategy-overview.pdf [accessed 12 February 2013].

- 25.Humphrey JH. Child undernutrition, tropical enteropathy, toilets and handwashing. Lancet. 2009;374:1032–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60950-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mara D, Lane J, Scott B, Trouba D. Sanitation and health. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dewey KG, Cohen RJ. Does birth spacing affect maternal or child nutritional status? A systematic literature review. Matern Child Nutr. 2007;3:151–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Best CM, Sun K, de Pee S, Bloem MW, Stallkamp G, Semba RD. Parental tobacco use is associated with increased risk of child malnutrition in Bangladesh. Nutrition. 2007;23:731–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strauss RS. Effects of the intrauterine environment on childhood growth. Br Med Bull. 1997;53:81–95. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Block S, Webb P. Up in smoke: Tobacco use, expenditure on food, and child malnutrition in developing countries. Econ Dev Cult Change. 2009;58:1–23. doi: 10.1086/605207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh PN, Yel D, Sin S, Khieng S, Lopez J, Job J, et al. Tobacco use among adults in Cambodia: evidence for a tobacco epidemic among women. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:905–12. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.058917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozaltin E, Hill K, Subramanian SV. Association of maternal stature with offspring mortality, underweight and stunting in low- to middle-income countries. JAMA. 2010;303:1507–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subramanian SV, Ackerson LK, Davey Smith G, John NA. Association of maternal height with child mortality, anthropometric failure, and anemia in India. JAMA. 2009;301:1691–701. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Painter RC, Osmond C, Gluckman P, Hanson M, Phillips DI, Roseboom TJ. Transgenerational effects of prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine on neonatal adiposity and health in later life. BJOG. 2008;115:1243–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rutstein SO, Johnson K. The DHS wealth index Calverton: ORC Macro; 2004 (DHS Comparative Reports No. 6). [Google Scholar]