Abstract

It has long been appreciated that the apoptotic activity of TNFα is context-dependent, and requires inhibition of NFκB signaling or de novo protein synthesis to be manifested in most normal cells in culture. Recent studies have uncovered an unexpected pro-apoptotic synergism between TNF cytokines and the CCN family of extracellular matrix proteins, which are dynamically expressed at sites of injury repair and inflammation. The presence of CCN1, CCN2, or CCN3 allows TNFα to induce apoptosis with high efficacy without perturbation of NFκB signaling or de novo protein synthesis, thus converting TNFα from a proliferation-promoting protein into an apoptotic inducer. CCN proteins also enhance the cytotoxicity of other TNF family cytokines including LTα, FasL, and TRAIL. CCN proteins synergize with TNF cytokines through binding to integrin α6β1 and the heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) syndecan-4 to induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation. Knockin mice that express a CCN1 mutant defective for binding α6β1-HSPG are severely blunted in TNFα- and Fas-mediated apoptosis, indicating that CCN1 is a physiologic regulator of these processes. Thus, CCN proteins in the extracellular matrix microenvironment can provide the contextual cues for the cytotoxicity of TNFα and related cytokines, and profoundly influence their activity.

Keywords: inflammation, apoptosis, TNF, FasL, TRAIL, CYR61, CTGF, NOV

INTRODUCTION

Extensive analysis of the apoptotic activity of TNFα has revealed elegant details in its apoptotic pathway, and expression of TNFα is required for or strongly implicated in apoptosis in certain contexts in vivo [1-3]. Yet TNFα by itself is unable to induce apoptosis in normal cells in culture, but requires the blockade of de novo protein synthesis or NFκB signaling to be cytotoxic [4,5]. How might TNFα induce apoptosis in vivo? Here we present evidence that the extracellular matrix (ECM) microenvironment, specifically the presence of the CCN family of matricellular proteins, can dictate the cytotoxicity of TNFα and related cytokines.

The CCN family of extracellular matrix proteins

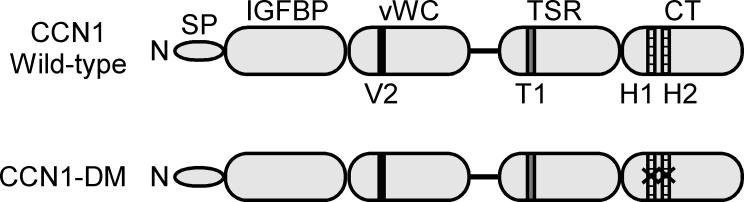

The CCN family of ECM proteins consists of six structurally conserved members in vertebrates, and is named after the first three members identified: Cyr61 (cysteine rich 61, CCN1), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF, CCN2), and nephroblastoma overexpressed (Nov, CCN3)[6-8]. CCN proteins share a similar modular structure, characterized by an N-terminal secretory peptide followed by structural domains with homologies to insulin-like growth factor binding proteins (IGFBP), von Willebrand factor type C repeat (vWC), thrombospondin type I repeat (TSR), and a C-terminal domain (CT) that contains a “cysteine knot” motif found in some growth factors (Fig. 1). These dynamically expressed proteins regulate diverse aspects of cellular behavior, including cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, survival, and differentiation in many cell types. As such, CCNs are recognized as “matricellular” proteins to draw distinction from classical ECM proteins whose primary roles are critical for the structural integrity of tissues [9,10]. Like other ECM cell adhesion molecules, CCNs function through direct binding to integrin receptors, utilizing cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) as co-receptors in some contexts [6].

Figure 1. A schematic diagram of CCN1 protein structure.

At the N-terminus (N) of CCN1 is a secretory signal peptide, followed by four modular domains with sequence homologies to insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP), von Willebrand factor type C repeat (vWC), thrombospondin type 1 repeat (TSR), and a C-terminal domain (CT) that contains a cysteine knot motif. All other CCN proteins share the same domain structure except CCN5, which lacks the CT domain. The receptor binding sites identified in CCN1 are: V2, an αvβ3 integrin binding site in the vWC domain [51]; T1, an α6β1 integrin binding site in the TSR domain [52]; and H1 and H2, binding sites for α6β1 and HSPGs in the CT domain [20]. The CCN1-DM mutant protein is disrupted in the H1 and H2 sites, thereby abrogating α6β1-HSPGs-dependent activities while preserving αvβ3-dependent angiogenic functions [21].

Accumulating evidence indicate that CCN proteins regulate the development of the cardiovascular and skeletal systems during embryogenesis, and participate in wound healing and tissue repair in adults [6-8]. Correspondingly, targeted disruptions of Ccn1 and Ccn2 in mice result in embryonic and peri-natal lethality due to cardiovascular and skeletal defects, respectively [11-13], although Ccn3-null mice are viable and exhibit only modest and transient skeletal phenotypes [14]. In adults, CCNs are highly induced at sites of injury repair and inflammation where TNF cytokines are often co-expressed, providing the opportunity for their interaction.

CCN proteins and TNF cytokines synergize to induce apoptosis in vitro and in vivo

TNFα is a potent activator of the NFκB pathway, which drives the expression of many pro-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic genes, thereby promoting cell survival. Paradoxically, TNFα can also activate a powerful apoptotic pathway if NFκB signaling or de novo protein synthesis is blocked [4,5]. Indeed, mice that are deficient in NFκB signaling die in utero from TNF-dependent apoptosis of liver cells [15]. Thus, the apoptotic activity of TNFα is thought to be contextual, subject to sensitizing viral infection or IFN-γ that perturbs NFκB signaling or protein synthesis. LTα binds the same receptors as TNFα and is thought to act similarly. In contrast, FasL and TRAIL are weak inducers of NFκB and do not require inhibition of NFκB signaling to induce apoptosis, but their cytotoxicity is nevertheless regulated by environmental factors.

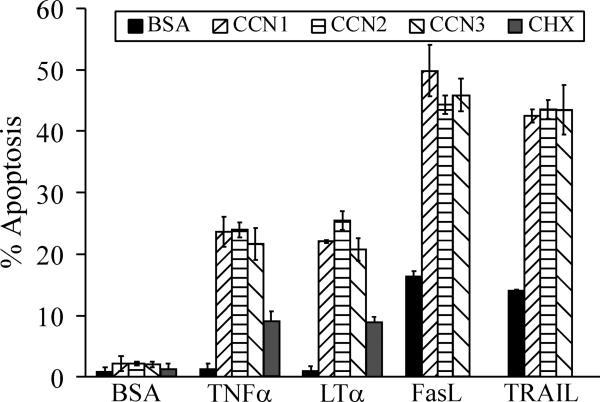

Our recent studies showed that the extracellular matrix microenvironment, as reflected by the presence of the dynamically expressed CCN proteins, can profoundly regulate TNF cytokine cytotoxicity. The matricellular proteins CCN1, CCN2, or CCN3, either in a soluble form or as cell adhesion substrates, enable TNFα and LTα to induce apoptosis and enhance the cytotoxic effects of FasL and TRAIL without perturbation of NFκB signaling or protein synthesis, leading to rapid apoptosis [16-18]. Whereas TNFα and LTα did not induce cell death on their own, each of the three CCN proteins enables them to induce apoptosis in ~25% of cells, more than 2-fold higher than the presence of 10 μg/ml cycloheximide within 4-6 hrs (Fig. 2), further suggesting that CCNs work through a mechanism distinct from inhibition of protein synthesis. These activities appear unique to CCN proteins and are not found in other ECM proteins tested, including collagen, fibronectin, laminin, and vitronectin [16]. Thus, although TNFα alone promotes cell proliferation in fibroblasts by inducing the expression of PDGF [19], the presence of CCN proteins can unmask its apoptotic activity and turn it into a cytotoxic factor.

Figure 2. Apoptotic synergism between the CCN and TNF protein families.

Normal human skin fibroblasts were serum-starved overnight before being treated for 6 hours at 37°C with serum-free media containing purified recombinant CCN1, CCN2, or CCN3 proteins (5 μg/ml each), with or without TNFα (10 ng/ml), LTα (10 ng/ml), FasL (50 ng/ml), or TRAIL (20 ng/ml). Where indicated, cycloheximide (CHX, 10 μg/ml) was added to cells 15 min. prior to addition of TNFα. Apoptotic cells were scored by DAPI-staining as described [16].

Since Ccn1- and Ccn2-null mice suffer pre- and peri-natal lethality, respectively, these animal models are not suitable for studying the effects of CCNs on TNF cytokine functions in vivo. To circumvent this problem, we created knockin mice in which the genomic Ccn1 was replaced by an allele that encodes a mutant CCN1, DM, which is disrupted in the two α6β1-HSPG binding sites in the CT domain (Fig. 1), leaving the other integrin binding sites in CCN1 intact [20,21]. The CCN1-DM mutant protein is unable to synergize with TNFα or FasL to promote fibroblast apoptosis [16,17], but is fully active in mediating integrin αvβ3-dependent angiogenic activities [21]. In contrast to Ccn1-null mice, Ccn1dm/dm mice are viable, fertile, and without any apparent abnormality [16]. CCN1/TNFα syngerism was first tested in Ccn1dm/dm mice by a subcutaneous injection of a bolus (50 μl) of high concentration TNFα (0.5 μM), which rapidly induced cutaneous apoptosis at the injection site. Consistent with the notion that CCN1 is critical for TNFα cytotoxicity, the number of apoptotic cells in Ccn1dm/dm mice was reduced by >60% compared to wild-type mice [16].

We further tested the Ccn1dm/dm mice in three different models of toxin-induced hepatitis to examine TNF cytokine-mediated apoptosis in vivo. First, intravenous delivery of the plant lectin concanavalin A activates inflammatory cells in the liver, inducing hepatocyte apoptosis in a TNFα-dependent process that is abrogated by neutralizing antibodies against TNFα or genetic ablation of TNFR1 or TNFR2 [22,23]. Second, tail vein injection of the agonistic anti-Fas monoclonal antibody Jo2 activates the Fas receptor and leads to massive hepatocyte apoptosis that is completely Fas-dependent [24]. Finally, intragastric administration of ethanol gavage mimics binge drinking and leads to FasL-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis that is prevented by neutralizing antibodies against FasL [25]. In all three experimental models, Ccn1dm/dm mice consistently show >60% reduction in hepatocyte apoptosis compared to wild-type mice [16,17]. These results support the notion that CCN1 is a physiologic regulator of TNFα- and Fas-mediated apoptosis in vivo, and that its interaction with α6β1/HSPGs is critical for this activity. Thus, the extracellular matrix microenvironment, specifically the presence of CCN1, can profoundly affect the cytotoxicity of TNF cytokines. These results do not exclude the participation of other factors such as IFNγ, which can also regulate TNF cytotoxicity in certain contexts [26].

ROS mediates signaling cross-talk between CCNs and TNFα or FasL

Upon TNFα treatment, activated TNFR1 recruits the adaptor protein TRADD through its intracellular death domain, leading to the recruitment of RIP and TRAF2 to form a complex (complex I) that is critical for activation of NFκB and the stress kinase JNK. This signaling complex subsequently dissociates from TNFR1 and recruits FADD and procaspases-8/10 to form complex II, which triggers the activation of the caspase cascade and apoptosis [2,5]. However, the anti-apoptotic c-FLIP, which exists in the cell and is also induced by NFκB, can compete with procaspases-8/10 for binding to complex II and thereby prevent caspase activation by TNFα [27,28]. Since JNK can phosphorylate the ubiquitin ligase ITCH, which targets c-FLIP for proteosome degradation, a sustained level of activated JNK leads to elimination of c-FLIP and allows the apoptotic pathway to proceed [29]. However, TNFα-activated JNK in normal cells is rapidly inactivated by MAPK phosphatases, which are also induced by NFκB [30], thus protecting c-FLIP from JNK-mediated degradation. MAPK phosphatases are, in turn, sensitive to the redox state in the cell, and are inactivated by cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) through oxidation of the critical cysteine residues in their active sites [31]. NFκB also induces anti-oxidant proteins, including Mn++-superoxide dismutase and ferritin heavy chain, which reduce cellular ROS levels [32,33]. Thus, NFκB suppresses the apoptotic activities of TNFα in normal cells by inducing de novo synthesis of c-FLIP, MAPK phosphatases, and anti-oxidant proteins, all of which serve to limit JNK activity and therefore apoptosis.

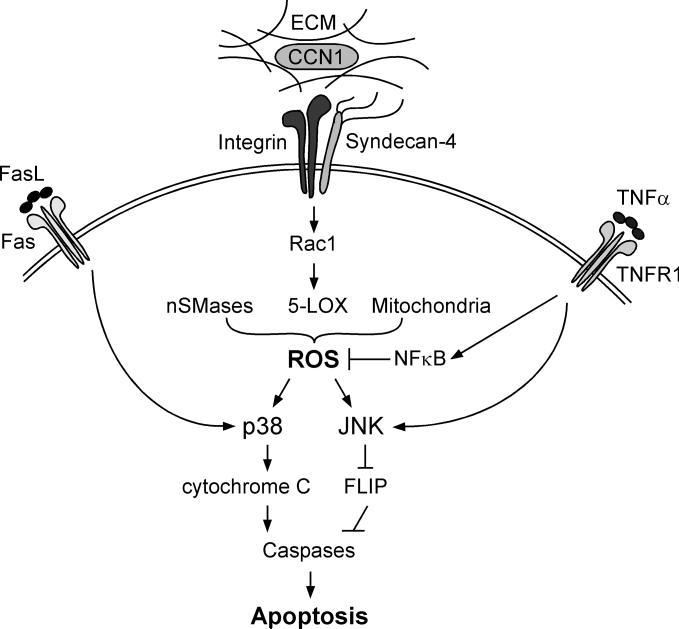

CCN proteins cross talk with TNF signaling by inducing a high level of ROS, apparently sufficient to override the anti-apoptotic effects of NFκB, without inhibiting NFκB activity [16,17]. CCN1-induced ROS allow TNFα-induced JNK activation to be sustained despite NFκB function, leading to JNK-dependent apoptosis [16]. ROS are also critical for CCN1/FasL synergism, where they trigger the hyperactivation of p38 MAPK, Bax activation and mitochondrial localization, leading to cytochrome c release and apoptosis [17].

Mechanistically, CCN1 induces ROS generation through binding to integrins αvβ5, α6β1, and the HSPG syndecan-4 [16], leading to activation of the small GTPase RAC1 [34]. RAC1 regulates ROS generation through multiple mechanisms, including 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX), certain isoforms of NADPH oxidase (NOX), and the mitochondria [35,36]. In CCN1/TNFα synergism, RAC1-dependent ROS generated through 5-LOX and mitchondria are critical [16]. Although TNFα induces ROS generation through a NOX-dependent mechanism [16,37], this pathway of ROS generation is not required for CCN/TNFα synergism [16]. CCN1 also induces neutral sphingomyelinase 1 (nSMase1) activity [17], which leads to the production of the lipid second messenger ceramide and the generation of ROS [38]. Studies using chemical inhibitor and siRNA showed that nSMase1-dependent generation of ROS is critical for p38 hyperactivation in CCN1/FasL syngerism [17]. Thus, CCN1 is able to induce high level of ROS through multiple pathways that override the antioxidant effects of NFκB.

Future Prospects

Our recent studies unravel a novel mechanism by which the tissue microenvironment directs or reinforces the apoptotic activity of TNF cytokines. In what biological contexts is this pro-apoptotic CCN/TNF synergism important? We have shown that CCN1 is critical for TNFα and FasL-mediated apoptosis in the liver, suggesting that CCNs may participate in hepatocyte injury in a diverse array of liver diseases in which TNF cytokines play a role. For example, TNFα and FasL levels are elevated in hepatic diseases in which apoptosis is induced by toxin exposure, alcohol abuse, and microbial infection. Accordingly, inhibition of TNFα and FasL by means of neutralizing antibodies, soluble decoy receptors, or genetic disruption resulted in reduction of hepatocyte cell death [22,25,39-45]. TNFα and FasL are also critical in cardiomyocyte apoptosis after cardiac ischemia and infarction, conditions where overexpression of CCN1 and CCN2 has been observed, suggesting that CCN/TNF apoptotic synergism may be important in cardiac injury as well [46-50]. Beyond apoptosis, CCNs may also regulate other aspects of TNF cytokine function. These possibilities are currently under investigation.

Figure 3. Pro-apoptotic signaling cross-talk between CCN1 and TNFα and FasL.

The matricellular protein CCN1 binds to integrins αvβ5, and α6β1, and the HSPG syndecan-4 to generate a high level of ROS through several mechanisms involving nSMases, 5-LOX, and the mitochondria [16,17]. The level of CCN1-induced ROS is sufficient to override the anti-apoptotic effects of NFκB by enhancing and maintaining the activation of JNK, which targets c-FLIP for degradation and allows activation of caspases-8/10, leading to apoptosis. In the presence of FasL, CCN1-induced ROS allows the hyperactivation of p38MAPK, which promotes Bax activation and cytochrome c release.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (CA46565, GM78492, and HL81390) to L.F.L.

Reference List

- 1.Aggarwal BB. Signalling pathways of the TNF superfamily: a double-edged sword. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:745–756. doi: 10.1038/nri1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertazza L, Mocellin S. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) biology and cell death. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2736–2743. doi: 10.2741/2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balkwill F. Tumour necrosis factor and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:361–371. doi: 10.1038/nrc2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varfolomeev EE, Ashkenazi A. Tumor necrosis factor: an apoptosis JuNKie? Cell. 2004;116:491–497. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muppidi JR, Tschopp J, Siegel RM. Life and death decisions: secondary complexes and lipid rafts in TNF receptor family signal transduction. Immunity. 2004;21:461–465. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C-C, Lau LF. Functions and Mechanisms of Action of CCN Matricellular Proteins. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009;41:771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holbourn KP, Acharya KR, Perbal B. The CCN family of proteins: structure-function relationships. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008;33:461–473. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leask A, Abraham DJ. All in the CCN family: essential matricellular signaling modulators emerge from the bunker. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:4803–4810. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bornstein P, Sage EH. Matricellular proteins: extracellular modulators of cell function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002;14:608–616. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau LF, Lam SC. The CCN family of angiogenic regulators: the integrin connection. Exp. Cell Res. 1999;248:44–57. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mo FE, Muntean AG, Chen CC, Stolz DB, Watkins SC, Lau LF. CYR61 (CCN1) Is Essential for Placental Development and Vascular Integrity. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:8709–8720. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8709-8720.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mo F-E, Lau LF. The matricellular protein CCN1 is essential for cardiac development. Circulation Research. 2006;99:961–969. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000248426.35019.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivkovic S, Popoff SN, Safadi FF, Zhao M, Stephenson RC, Yoon BS, Daluiski A, Segarini P, Lyons KM. Connective tissue growth factor is an essential regulator of skeletal development. Development. 2003;130:2791. doi: 10.1242/dev.00505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canalis E, Smerdel-Ramoya A, Durant D, Economides AN, Beamer WG, Zanotti S. Nephroblastoma Overexpressed (Nov) Inactivation Sensitizes Osteoblasts to Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2, But Nov Is Dispensable for Skeletal Homeostasis. Endocrinology. 2009 doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karin M, Lin A. NF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and death. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:221–227. doi: 10.1038/ni0302-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen C-C, Young JL, Monzon RI, Chen N, Todorovic V, Lau LF. Cytotoxicity of TNFα is regulated by Integrin-Mediated Matrix Signaling. EMBO J. 2007;26:1257–1267. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juric V, Chen CC, Lau LF. Fas-Mediated Apoptosis is Regulated by the Extracellular Matrix Protein CCN1 (CYR61) in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;29:3266–3279. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00064-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franzen CA, Chen CC, Todorovic V, Juric V, Monzon RI, Lau LF. The Matrix Protein CCN1 is Critical for Prostate Carcinoma Cell Proliferation and TRAIL-Induced Apoptosis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2009;7:1045–1055. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Battegay EJ, Raines EW, Colbert T, Ross R. TNF-alpha stimulation of fibroblast proliferation. Dependence on platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) secretion and alteration of PDGF receptor expression. J. Immunol. 1995;154:6040–6047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen N, Chen CC, Lau LF. Adhesion of human skin fibroblasts to Cyr61 is mediated through integrin α6β1 and cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:24953–24961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leu S-J, Chen N, Chen C-C, Todorovic V, Bai T, Juric V, Liu Y, Yan G, Lam SCT, Lau LF. Targeted mutagenesis of the matricellular protein CCN1 (CYR61): selective inactivation of integrin α6β1-heparan sulfate proteoglycan coreceptor-mediated cellular activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:44177–44187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407850200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trautwein C, Rakemann T, Brenner DA, Streetz K, Licato L, Manns MP, Tiegs G. Concanavalin A-induced liver cell damage: activation of intracellular pathways triggered by tumor necrosis factor in mice. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1035–1045. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolf D, Hallmann R, Sass G, Sixt M, Kusters S, Fregien B, Trautwein C, Tiegs G. TNF-alpha-induced expression of adhesion molecules in the liver is under the control of TNFR1--relevance for concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. J. Immunol. 2001;166:1300–1307. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogasawara J, Watanabe-Fukunaga R, Adachi M, Matsuzawa A, Kasugai T, Kitamura Y, Itoh N, Suda T, Nagata S. Lethal effect of the anti-Fas antibody in mice. Nature. 1993;364:806–809. doi: 10.1038/364806a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou Z, Sun X, Kang YJ. Ethanol-induced apoptosis in mouse liver: Fas- and cytochrome c-mediated caspase-3 activation pathway. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;159:329–338. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61699-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kusters S, Gantner F, Kunstle G, Tiegs G. Interferon gamma plays a critical role in T cell-dependent liver injury in mice initiated by concanavalin A. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:462–471. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Micheau O, Lens S, Gaide O, Alevizopoulos K, Tschopp J. NF-kappaB signals induce the expression of c-FLIP. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;21:5299–5305. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.16.5299-5305.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thome M, Tschopp J. Regulation of lymphocyte proliferation and death by FLIP. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2001;1:50–58. doi: 10.1038/35095508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang L, Kamata H, Solinas G, Luo JL, Maeda S, Venuprasad K, Liu YC, Karin M. The E3 ubiquitin ligase itch couples JNK activation to TNFalpha-induced cell death by inducing c-FLIP(L) turnover. Cell. 2006;124:601–613. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z, Cao N, Nantajit D, Fan M, Liu Y, Li JJ. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 represses c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-mediated apoptosis via NF-kappaB regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:21011–21023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802229200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meng TC, Fukada T, Tonks NK. Reversible oxidation and inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases in vivo. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:387–399. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00445-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pham CG, Bubici C, Zazzeroni F, Papa S, Jones J, Alvarez K, Jayawardena S, De Smaele E, Cong R, Beaumont C, et al. Ferritin heavy chain upregulation by NF-kappaB inhibits TNFalpha-induced apoptosis by suppressing reactive oxygen species. Cell. 2004;119:529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rui T, Kvietys PR. NFkappaB and AP-1 differentially contribute to the induction of Mn-SOD and eNOS during the development of oxidant tolerance. FASEB J. 2005;19:1908–1910. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4028fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen C-C, Chen N, Lau LF. The angiogenic factors Cyr61 and CTGF induce adhesive signaling in primary human skin fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:10443–10452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiarugi P, Pani G, Giannoni E, Taddei L, Colavitti R, Raugei G, Symons M, Borrello S, Galeotti T, Ramponi G. Reactive oxygen species as essential mediators of cell adhesion: the oxidative inhibition of a FAK tyrosine phosphatase is required for cell adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:933–944. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Werner E, Werb Z. Integrins engage mitochondrial function for signal transduction by a mechanism dependent on Rho GTPases. J. Cell Biol. 2002;158:357–368. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim YS, Morgan MJ, Choksi S, Liu ZG. TNF-induced activation of the Nox1 NADPH oxidase and its role in the induction of necrotic cell death. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:675–687. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Won JS, Singh I. Sphingolipid signaling and redox regulation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;40:1875–1888. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leist M, Gantner F, Jilg S, Wendel A. Activation of the 55 kDa TNF receptor is necessary and sufficient for TNF-induced liver failure, hepatocyte apoptosis, and nitrite release. J. Immunol. 1995;154:1307–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Czaja MJ, Xu J, Alt E. Prevention of carbon tetrachloride-induced rat liver injury by soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1849–1854. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iimuro Y, Gallucci RM, Luster MI, Kono H, Thurman RG. Antibodies to tumor necrosis factor alfa attenuate hepatic necrosis and inflammation caused by chronic exposure to ethanol in the rat. Hepatology. 1997;26:1530–1537. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsuji H, Harada A, Mukaida N, Nakanuma Y, Bluethmann H, Kaneko S, Yamakawa K, Nakamura SI, Kobayashi KI, Matsushima K. Tumor necrosis factor receptor p55 is essential for intrahepatic granuloma formation and hepatocellular apoptosis in a murine model of bacterium-induced fulminant hepatitis. Infect. Immun. 1997;65:1892–1898. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1892-1898.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sudo K, Yamada Y, Moriwaki H, Saito K, Seishima M. Lack of tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1 inhibits liver fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride in mice. Cytokine. 2005;29:236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shibata H, Yoshioka Y, Ohkawa A, Abe Y, Nomura T, Mukai Y, Nakagawa S, Taniai M, Ohta T, Mayumi T, et al. The therapeutic effect of TNFR1-selective antagonistic mutant TNF-alpha in murine hepatitis models. Cytokine. 2008;44:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ronco MT, Frances DE, Ingaramo PI, Quiroga AD, Alvarez ML, Pisani GB, Revelli SS, Carnovale CE. Tumor necrosis factor alpha induced by Trypanosoma cruzi infection mediates inflammation and cell death in the liver of infected mice. Cytokine. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sugano M, Hata T, Tsuchida K, Suematsu N, Oyama J, Satoh S, Makino N. Local delivery of soluble TNF-alpha receptor 1 gene reduces infarct size following ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2004;266:127–132. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000049149.03964.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee P, Sata M, Lefer DJ, Factor SM, Walsh K, Kitsis RN. Fas pathway is a critical mediator of cardiac myocyte death and MI during ischemia-reperfusion in vivo. Am. J. Physiol Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003;284:H456–H463. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00777.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y, Takemura G, Kosai K, Takahashi T, Okada H, Miyata S, Yuge K, Nagano S, Esaki M, Khai NC, et al. Critical roles for the Fas/Fas ligand system in postinfarction ventricular remodeling and heart failure. Circ. Res. 2004;95:627–636. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141528.54850.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Kaminski K, Kaminska A, Fuchs M, Klein G, Podewski E, Grote K, Kiian I, Wollert KC, Hilfiker A, et al. Regulation of proangiogenic factor CCN1 in cardiac muscle: impact of ischemia, pressure overload, and neurohumoral activation. Circulation. 2004;109:2227–2233. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127952.90508.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM, Feijen A, Korving J, Korchynskyi O, Larsson J, Karlsson S, ten Dijke P, Lyons KM, Goldschmeding R, Doevendans P, et al. Connective tissue growth factor expression and Smad signaling during mouse heart development and myocardial infarction. Dev. Dyn. 2004;231:542–550. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen N, Leu S-J, Todorovic V, Lam SCT, Lau LF. Identification of a novel integrin αvβ3 binding site in CCN1 (CYR61) critical for pro-angiogenic activities in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol. Chem. 2004;279:44166–44176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leu S-J, Liu Y, Chen N, Chen CC, Lam SC, Lau LF. Identification of a novel integrin α6β1 binding site in the angiogenic Inducer CCN1 (CYR61). J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:33801–33808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]