Abstract

Here we report a case of sudden, unilateral, painless visual loss in a middle-aged patient. A 45-year-old gentleman with no known past medical history presented with acute painless left visual impairment. Clinically, he was found to have a left optic neuropathy associated with a swollen and hyperemic left optic disc. The right optic disc was noted to be small and crowded, and both optic discs were noted to have irregular margins. Humphrey perimetry revealed a constricted visual field in the left eye. Fundus autofluorescence imaging revealed autofluorescence, and B-scan ultrasonography showed hyperreflectivity within both nerve heads. Blood investigations for underlying ischemic and inflammatory markers revealed evidence of hyperlipidemia but were otherwise normal. A diagnosis of left nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAAION) was made, with associated optic disc drusen and hyperlipidemia. NAAION typically occurs in eyes with small, structurally crowded optic discs. The coexistence of optic disc drusen and vascular risk factors may further augment the risk of developing NAAION.

Keywords: optic disc drusen, ischemic optic neuropathy, painless visual loss

Introduction

Although largely asymptomatic, optic disc drusen may occasionally be associated with vascular complications, including nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAAION).1–3 NAAION is one of the commonest causes of acute visual loss in the elderly population, and is typically found in association with vascular disorders, such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.4–6 NAAION may occasionally present as a complication of optic disc drusen. In a relatively young patient with no known ischemic risk factors, investigations for underlying systemic disorders are required. We report a case of NAAION in a relatively young patient with bilateral optic disc drusen and undiagnosed hyperlipidemia.

Case report

A 45-year-old Indonesian businessman, who was a nonsmoker with an unremarkable past medical history, presented with a history of sudden painless visual loss in the left eye that had occurred 2 weeks prior. The visual loss occurred while he was at work and was experienced as a sudden constriction in the visual field of the left eye. He consulted an ophthalmologist and was commenced on oral mecobalamin and a reducing dose of oral methylprednisolone over a 2-week period with no improvement in vision. He was on no regular medication and had no history of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor use. A routine health check performed 3 months prior was reportedly normal.

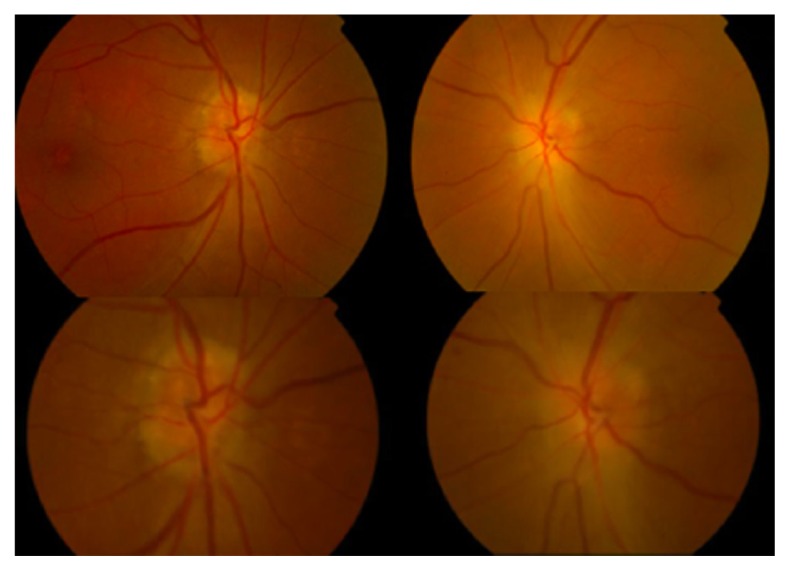

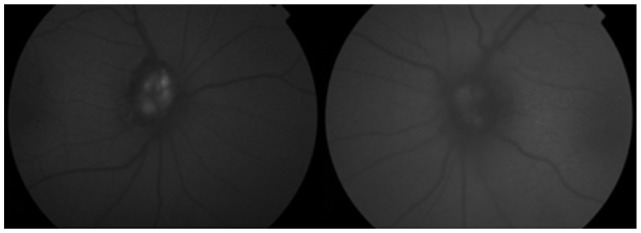

On examination, best-corrected visual acuity was 6/7.5 and 6/9 in the right and left eye, respectively. Ishihara color plate testing was full in either eye. There was no red desaturation between the eyes, but light brightness perception in the left eye was decreased at 80% compared with 100% in the right eye. A left relative afferent pupillary defect was present. The left optic disc was noted to be diffusely swollen and hyperemic; the right optic disc was small, with a cup-disc ratio of 0.1. Both optic discs were noted to have irregular margins (Figure 1). Anterior segment examination was unremarkable and intraocular pressures were normal bilaterally.

Figure 1.

Fundus photograph showing swollen and hyperemic left optic disc with small and crowded right optic disc.

Note: Both optic discs have irregular margins.

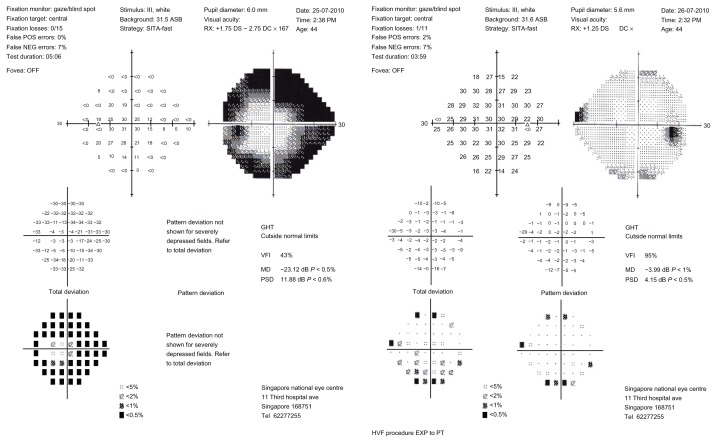

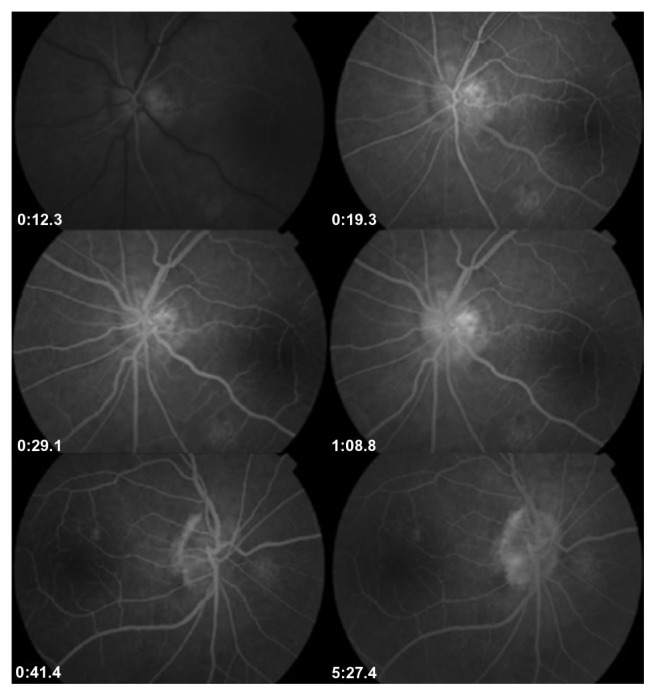

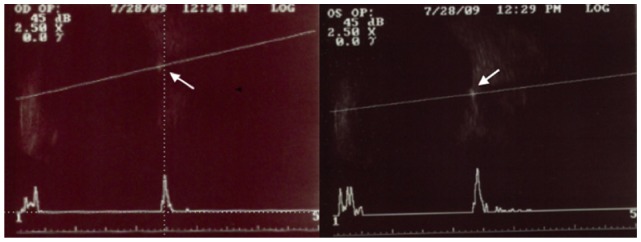

Humphrey static perimetry revealed a constricted visual field in the left eye (Figure 2). Fundus photography using an autofluorescence filter showed autofluorescence of both optic nerve heads (Figure 3). Fundus fluorescein angiography confirmed the absence of any retinal vascular pathology, as well as the presence of dye leakage over the left optic disc consistent with left optic disc edema (Figure 4). B-scan ultrasonography showed the presence of hyperreflectivity within both optic nerve heads (Figure 5). Laboratory studies, including complete blood count, fasting glucose, fasting homocysteine, venereal diseases reference laboratory test, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibody and extractable nuclear antigens, were normal apart from fasting lipids, which showed hyperlipidemia. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the anterior visual pathway was normal.

Figure 2.

Humphrey visual field, 24-2 SITA-FAST protocol of patient’s right and left eyes, demonstrating a constricted visual field in the left eye.

Figure 3.

Autofluorescence of both optic discs.

Figure 4.

Fundus fluorescein angiography showing absence of any vascular or macular pathology, and the presence of left optic disc edema with leakage of dye.

Figure 5.

B-scan ultrasonography of the right (OD) and left (OS) eye, demonstrating high reflectivity of drusen within both optic discs.

A diagnosis of left NAAION was made. The patient was commenced on aspirin and simvastatin as well as gutt. brimonidine twice daily in both eyes.

Discussion

NAAION is presumed to be due to compromise of the microcirculation within the optic nerve head, in which the presence of a small structurally “crowded” optic disc contributes to the ensuing ischemia.7,8 Systemic associations include hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking.4 The mean age at which NAAION occurs is approximately 60 years.5,6 Visual loss is typically noted upon awakening in the morning, and this is possibly related to nocturnal systemic hypotension.4,9 Visual loss may be static or may progressively worsen over weeks before stabilizing.10 The optic disc appears edematous and usually hyperemic, and by 4–8 weeks, appears atrophic. The optic disc in the contralateral eye is typically small, with a small “disc at risk”.11

There is no proven treatment for NAAION. Recently applied modalities such as hyperbaric oxygen12 and optic nerve sheath decompression surgery13 have shown no beneficial effects. A recent large, nonrandomized controlled study suggested that oral steroids might be helpful for acute NAAION.14 Other recently proposed interventions are intravitreal injections of corticosteroids and antivascular endothelial growth factor agents.15 Aspirin has a proven effect in reducing the incidence of stroke, but its role in reducing the risk of NAAION in the fellow eye is still unclear.16

Optic disc drusen are acellular, calcified deposits within the optic nerve head. Population studies have reported a prevalence of 0.34%–2%.4,17 Optic disc drusen are bilateral in 75%–86% of cases but are usually asymmetric.18 There is no gender bias and no association with refractive error.19 However, there is an association with small optic discs with abnormal vasculature.20–23 The pathophysiology of optic disc drusen has not been proven, but most theories suggest that it is an end-product of the metabolic abnormalities associated with intra-axonal mitochondrial damage from disrupted ganglion cell axonal transport.1,21 Ancillary testing to confirm optic disc drusen include B-scan ultrasonography, which shows the optic nerve head to be elevated with high reflectivity due to the presence of calcium. Similarly, computed tomography scans may demonstrate a bright signal at the junction of the posterior globe and optic nerve. Exposed optic disc drusen and some buried optic disc drusen show autofluorescence on fluorescein filter fundus photography.24 Optical coherence tomography25 and scanning laser ophthalmoscopy26 may give supporting evidence of the presence of optic disc drusen.

Optic disc drusen are often an incidental finding during routine eye examination. While asymptomatic in most cases, transient visual obscuration may occur in patients with optic disc drusen due to transient ischemia of the optic nerve head as a result of increased tissue pressure.27 Although impairment of visual acuity as a result of optic disc drusen is rare, slowly progressive visual field loss (enlarged blind spot, arcuate defects, peripheral depression) may occur as a direct consequence of axonal compression, but is often unnoticed by the patient.28–30 Occasionally, a more acute visual loss may occur, sometimes involving the central vision.31 This may be the result of local vascular complications such as central retinal artery and vein occlusion,32,33 and NAAION,1–3 which can occur in the absence of any associated vascular disorder.28,34 These complications have been postulated to be due to the compressive effect of drusen on the blood vessels.27,34 In addition, both NAAION and optic disc drusen have been associated with a small scleral canal that leads to axonal crowding and secondary vascular compromise.

A case series by Purvin et al35 found that NAAION in patients with optic disc drusen tended to occur at a younger age compared with patients who have NAAION which is not associated with optic disc drusen.5,6 A 12-year-old child with bilateral optic disc drusen was reported to suffer unilateral visual loss due to NAAION.36 Purvin et al also reported that patients with optic disc drusen and NAAION were more likely to have preceding episodes of transient visual obscuration, as well as a better visual outcome compared with patients having NAAION without optic disc drusen.35 However, the pattern of visual field loss and the prevalence of underlying vascular disorders were similar in patients with and without optic disc drusen.35 Therefore, it is still important to investigate for underlying vascular disorders in a patient with NAAION and optic disc drusen. Coexistent hyperlipidemia was found to be present in our patient, which could have increased the risk of microcirculatory compromise.

Conclusion

The risk of developing NAAION is likely to be increased in a patient with optic disc drusen occurring in a small, structurally crowded optic disc and with underlying hyperlipidemia.

Footnotes

Disclosure

No author has a financial or proprietary interest in any material or method mentioned in this work.

References

- 1.Gittinger JJ, Lessell S, Bondar RL. Ischemic optic neuropathy associated with optic disc drusen. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1984;4:79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liew SC, Mitchell P. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in a patient with optic disc drusen. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1999;27:157–160. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1606.1999.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman WD, Dorrell ED. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy associated with disc drusen. J Neuroophthalmol. 1996;16:7–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold AC. Pathogenesis of nonarteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2003;23:157–163. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200306000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boghen DR, Glaser JS. Ischaemic optic neuropathy: the clinical profile and natural history. Brain. 1975;98:689–708. doi: 10.1093/brain/98.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Repka MX, Savino PJ, Schatz NJ, Sergott RC. Clinical profile and long-term implications of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96:478–483. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77911-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayreh SS. Acute ischemic disorders of the optic nerve: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations and management. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 1996;9:407–442. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berde RM. Optic disc risk factors for non-arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116:759–764. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buono LM, Foroozan R, Sergott RC, Savino PJ. Nonarteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13:357–361. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200212000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold AC, Hepler RS. Natural history of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol. 1994;14:66–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luneau K, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Ischaemic optic neuropathies. Neurologist. 2008;14:341–354. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e318177394b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnold AC, Hepler RS, Lieber M, Alexander JM. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for nonarteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122:535–541. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ischaemic Optic Neuropathy Decompression Trial Research Group. Ischaemic Optic Neuropathy Decompression Trial. Twenty-four month update. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:793–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB. Non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:734–742. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelman SE. Intravitreal triamcimolone or bevacizumab for nonarteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy: do they merit further study? J Neuroophthalmol. 2007;27:161–163. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e31814a61ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck RW, Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Tan ES, Moke PS. Aspirin therapy in nonarteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123:212–217. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman AH, Gartner S, Modi SS. Drusen of the optic disc: a retrospective study in cadaver eyes. Br J Ophthalmol. 1975;59:413–421. doi: 10.1136/bjo.59.8.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arbabi EM, Fearnley TE, Carrim ZI. Drusen and the misleading optic disc. Pract Neurol. 2010;10:27–30. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.200089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg MA, Savino PJ, Glaser JS. A clinical analysis of pseudopapilloedema. I. Population, laterality, acuity, refractive error, ophthalmoscopic characteristics, and coincident disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97:65–70. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1979.01020010005001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.You QS, Xu L, Wang YX, Jonas JB. Prevalence of optic disc drusen in an adult Chinese population: the Beijing Eye Study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:227–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mullie MA, Sanders MD. Scleral canal size and optic nerve head drusen. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99:356–359. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(85)90369-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spencer WH. Drusen of the optic disc and aberrant axoplasmic transport. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;85:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76658-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonas JB, Gusek GC, Guggenmoos-Holzmann I, Naumann GO. Optic nerve head drusen associated with abnormally small optic discs. Int Ophthalmol. 1987;11:79–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00136734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mustonen E, Nieminen H. Optic disc drusen – a photographic study. I. Autofluorescence pictures and fluorescein angiography. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1982;60:849–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1982.tb00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roh S, Noecker RJ, Scheman JS, Hedges TR, 3rd, Weiter JJ, Mattoz C. Effect of optic nerve head drusen on nerve fiber layer thickness. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:878–885. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)95031-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haynes RJ, Manivannan A, Walker S, Dharp PF, Forrester JV. Imaging of optic nerve head drusen with the scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:654–657. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.8.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadun AA, Currie JN, Lessell S. Transient visual obscuration with elevated optic discs. Ann Neurol. 1984;16:489–494. doi: 10.1002/ana.410160410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Auw-Haedrich C, Staubach F, Witschel H. Optic disk drusen. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47:515–532. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(02)00357-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lansche RK, Rucker CW. Progression of defects in visual fields produced by hyaline bodies in optic discs. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;59:413–421. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1957.00940010127011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mustonen E. Pseudopapilloedema with and without verified optic drusen: a clinical analysis I. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1983;61:1037–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1983.tb01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck RW, Corbett JJ, Thompson HS, Sergott RC. Decreased visual acuity from optic disc drusen. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103:1155–1159. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1985.01050080067022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newman NJ, Lessell S, Brandt EM. Bilateral central retinal artery occlusions, disk drusen and migraine. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;107:236–240. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chern S, Magargal LE, Annesley WH. Central retinal vein occlusion associated with drusen of the optic disc. Ann Ophthalmol. 1991;23:66–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lam BL, Morais CG, Jr, Pasol J. Drusen of the optic disc. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8:404–408. doi: 10.1007/s11910-008-0062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Purvin V, King R, Kawasaki A, Yee R. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in eyes with optic disc drusen. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:48–53. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nanji AA, Klein KS, Pelak VS, Repka MX. Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in a child with optic disk drusen. J AAPOS. 2012;16:207–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]