Abstract

Polymeric microparticles have been widely investigated as platforms for delivery of drugs, vaccines, and imaging contrast agents, and are increasingly used in a variety of clinical applications. Microparticles activate the inflammasome complex and induce the processing and secretion of IL-1β, a key innate immune cytokine. Recent work suggests that while receptors are clearly important for particle phagocytosis, other physical characteristics especially shape, play an important role in the way microparticles activate cells. We examined the role of particle surface texturing not only on uptake efficiency but also on the subsequent immune cell activation of the inflammasome. Using a method based on emulsion processing of amphiphilic block copolymers, we prepared microparticles with similar overall sizes and surface chemistries, but having either smooth or highly micro-textured surfaces. In vivo, textured (budding) particles induced more rapid neutrophil recruitment to the injection site. In vitro, budding particles were more readily phagocytosed than smooth particles and induced more lipid raft recruitment to the phagosome. Remarkably, budding particles also induced stronger IL-1β secretion than smooth particles, through activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. These findings demonstrate a pronounced role of particle surface topography in immune cell activation suggesting that shape is a major determinant of inflammasome activation.

INTRODUCTION

The human immune system is poised to recognize and respond to foreign particulate substances including pollen, bacteria, fungal spores, and inorganic substances. The initial step to immune cell activation for most particulate materials is phagocytosis, a receptor-mediated, actin-dependent process carried out by a specialized subset of cells termed ‘professional phagocytes’, including neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells (1). Phagocytosis can occur through association with one of several different cell surface proteins, including complement receptors, Fc-receptors, scavenger receptors, and pathogen-specific receptors, like TLRs, mannose receptors, and lectins (2, 3). Phagocytosis by immune cells can also be utilized for a variety of therapeutic applications including vaccine adjuvants and drug delivery, using particulate material like alum and polymeric microparticles, as reviewed in (4–6).

Although the process of phagocytosis has been extensively studied (3, 7–14), the physical and chemical characteristics that determine the response elicited by different particles remains unclear. Recent pioneering work from Mitragotri’s group (15) and subsequent studies (16–19), have demonstrated that the shape of a polymer microparticle has a dramatic effect on phagocytosis. Specifically, the local curvature of the particle surface that is first encountered by the phagocyte dictates whether the actin cup necessary to engulf the particle can be formed (15, 17), and thus whether the particle is internalized. This suggests that immune cells use surface curvature as a locally accessible proxy for overall particle dimension. Other work has demonstrated that for spherical microparticles, size plays a role in uptake efficiency, with maximal phagocytosis for particle diameters of 1–3 μm (19–21). These findings were not dependent on the receptor used to initially mediate attachment or internalization, pointing to a highly universal role of particle geometry in phagocytic uptake.

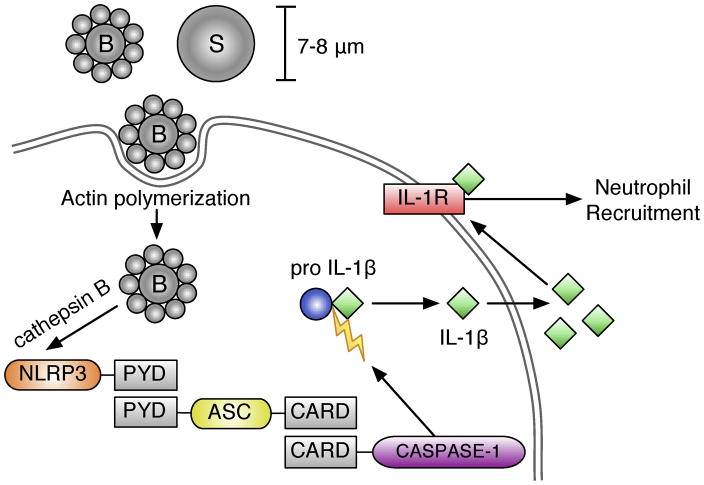

Following phagocytosis, particulate material such as alum, silica, asbestos, monosodium urate crystals, cobalt/chromium metal alloys, and titanium particles are known to activate nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, leucine rich repeat and pyrin domain containing protein 3 (NLRP3)4, a NOD-like receptor protein located in the cytosol of macrophages (22–29). The process of NLRP3 inflammasome activation involves a conformational change in NLRP3 into its active form, which then associates with its adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (ASC) (30) through Pyrin domain interactions. This complex leads to the recruitment of pro-Caspase-1 through Caspase-recruitment domain interactions (31–33). Pro-Caspase-1 is then cleaved into its active form, Caspase-1 (CASP1). Active CASP1 cleaves pro-IL-1β into its active, secreted form, IL-1β. IL-1 is a potent inflammatory cytokine, important for functions including macrophage and neutrophil recruitment, as well as T cell activation (34, 35).

While a striking correlation between geometry and engulfment rate has been established for “simple” particle shapes (i.e., spheres, ellipsoids, discs) (15–19, 28), the potential to use more complex particle shapes to engineer the phagocytic response remains largely untapped. Furthermore, questions of how particle geometry dictates the immune response following phagocytosis, such as IL-1β release, have not been addressed. Our understanding of these effects remains fairly limited, primarily because until recently, methods did not exist to produce uniform microparticles with controlled surface chemistry and systematically varying shapes.

Here, we take advantage of a recently developed route to prepare polymeric microparticles with complex but well-controlled surface topographies, based on emulsion processing of amphiphilic block copolymers (36, 37). This provides a simple platform to compare the response of phagocytes to particles of similar overall size and surface chemistry, but where the particle surfaces are either smooth or densely covered with micro-scale protrusions (which we refer to as textured or ‘budding’ particles). In this way we can assess the role of shape independent of receptor interaction with particles based on their surface chemistry. Since phagocytes respond to local surface curvature (15–19, 28) we anticipated that the regions of high curvature on the budding particles should substantially alter the immune response. We examined the acute inflammatory response to polymeric microparticles via neutrophil recruitment in an in vivo mouse peritonitis model. We further analyzed the mechanism of this response using mouse macrophages to compare the ability of smooth and budding particles to be phagocytosed, activate immune cells, activate the inflammasome, and induce IL-1β cytokine release.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microparticle preparation

Generation of solvent-in-water emulsion droplets of well-controlled sizes via flow-focusing, and conversion to particle suspensions were conducted as previously described (37). The resulting suspensions of polystyrene-block-poly(ethylene oxide) (PS-PEO) microparticles were dialyzed against deionized water for 2–3 days to remove glycerol and residual chloroform, then centrifuged and resuspended in fresh deionized water 5–8 times to remove excess and weakly adsorbed poly(vinyl alcohol) surfactant. Budding and spherical particles were approximately 7–8 μm in diameter. Stock solution concentrations of particles were approximately 1.45 × 107 particles/mL.

PEO functionalization of small particles

PEO-coated particles with diameters of 0.5 and 1.0 μm were prepared by modifying carboxyl-functionalized PS particles (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) with amino-PEO (α-aminoethyl, ω-methoxy PEO, 10 kDa; Nanocs, New York, NY). Briefly, PS-COOH particles (0.86 μmol COOH groups, in 500 μL) were allowed to react with 6 μmol of N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), and 9.5 μmol of N-hydroxylsuccinimide (NHS) in an aqueous 100 mM 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer (pH 6.0) at 4°C. Solutions of EDC and NHS were freshly prepared. After 1 h at room temperature, activated PS particles were washed twice with an MES solution (pH 6.0) via centrifugation and redispersion. Next, an excess of amino-PEO (1.29 μmol) in 2.58 mL of PBS (pH 7.2) was added, followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature and then washing twice with PBS via centrifugation and redispersion. Successful functionalization was confirmed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy on a sample of particles deposited on a silicon wafer. The particles were stored in aqueous suspension at 4°C until use. EDC, MES, and PBS were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The stock solution concentrations of the small spherical particles were approximately 1 × 1011 particles/mL.

Electron Microscopy

Microparticle morphologies were observed by scanning electron microscopy (ScEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). For ScEM, a droplet of aqueous dispersion of particles was allowed to dry on a clean silicon wafer, followed by coating with a thin layer of gold. Samples were imaged using a JEOL 6320 FXV ScEM at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. For TEM, a droplet of particle dispersion was allowed to dry on a copper grid coated with a carbon film (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and imaged with a JEOL 2000 FX electron microscope operated at 200 kV.

Cell culture

Immortalized mouse macrophages from WT, NLRP3-deficient, ASC-deficient, and Caspase1-deficient mice were generously provided by K. Fitzgerald and E. Latz (University of Massachusetts Medical School), and were generated as previously described (22) using a J2 recombinant retrovirus carrying v-myc and v-raf(mil) oncogenes. Cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were plated in GM-CSF (1 ng/mL; eBioscience)-containing media for 18 h prior to stimulations.

Cell Stimulations

Mouse macrophages (4 – 5 × 105) were primed for 3 h with LPS (100 ng/mL – Sigma) to up-regulate pro-IL-1β expression or left unprimed (Media), then stimulated with microparticles (budding, spherical, or small particles) at given particle-to-cell ratios (particle number:cell number), 130 μg/ml alum (Thermo Scientific), 5 μM nigericin (Sigma), or transfected with 400 ng of poly(dA:dT) (Sigma) using GeneJuice (EMD Chemicals) for an additional 6 h or 18 h. Where indicated, cells were treated with 50μM CA-074-Me (EMD Millipore), 250 nM Latrunculin A (Sigma), or 1 μM Cytochalasin D (Sigma). Secreted IL-1β was measured using ELISA (R&D Systems) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Confocal Microscopy

Cells were cultured on glass-bottom 35 mm tissue-culture dishes (MatTek) in complete medium. Where indicated, cells were stained with LysoTracker Green, Hoechst 34580, and Alexa488-CTxB from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Images were taken on a Leica SP2 AOBS confocal laser-scanning microscope with a 63x objective, using Leica Confocal Software. Multicolor images were acquired by sequential scanning with only one laser active per scan to avoid cross-excitation. Overall brightness and contrast of images were optimized using Adobe Photoshop CS3.

Mice injections

C57BL/6 (WT), IL-1R-knockout (IL-1R KO), and CASP1KO mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). NLRP3KO mice were provided by K. Fitzgerald (University of Massachusetts Medical School). Mice were injected i.p. with sterile PBS (400 μl), 4% thioglycollate (1 mL), or 2 × 106 microparticles (approx. 450μg). Mice were sacrificed by isoflurane inhalation followed by cervical dislocation. Peritoneal exudate cells (PECs) were isolated 6 or 16 h after injections as previously described (29). All mouse strains, age and sex-matched with appropriate controls, were bred and maintained at the University of Massachusetts Medical School animal facility. Experiments involving live animals were in accordance with guidelines set forth by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Department of Animal Medicine and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Flow cytometric analysis

Neutrophils in PECs were enumerated as previously described (29). Data were acquired by DIVA (BD Biosciences) and were analyzed with FlowJo 8.8.6 software (Tree Star Inc.).

Statistical Analysis

An unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to determine statistical significance of independent experiments where two groups were compared When more than two groups were compared, ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s correction for post test comparisons was used. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant with 95% confidence intervals. Statistics were performed using GraphPad (Prism v5.0d) software.

RESULTS

Preparation of budding particles

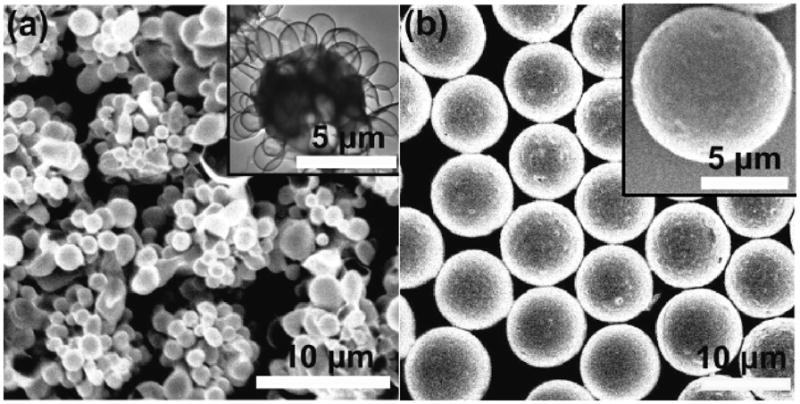

PS-PEO particles are an excellent model system as PS-PEO has been well studied in the context of generation of textured particles (37). There have also been several studies examining the use of PS and PS-PEO particles as therapeutic agents (15, 38, 39). Therefore, to study the role of surface texturing on the immune response, we prepared polymer microparticles consisting of PS-PEO diblock copolymer (38 and 11 kg/mol number-average molecular weights Mn, respectively) blended with PS homopolymer (Mn = 12.4 kg/mol). Initially, the polymers are dissolved in chloroform, then emulsified in water using a microfluidic flow-focusing device to provide droplets of uniform size (37). Removal of the organic solvent by evaporation subsequently yields solid polymer microparticles of phagocytosable size (7–8 μm diameter). As shown in Fig. 1, by adjusting the mass ratio of PS-PEO:PS the morphology of the particles can be changed from ‘budding’ particles (100: 0, Fig. 1 A), that are densely coated with vesicular protrusions of 1–2 μm diameter, to smooth spherical particles (20: 80, Fig. 1 B). Due to the interfacial activity of PS-PEO, the surfaces of both types of particles are coated with a similar “brush” layer of PEO, as well as residual poly(vinyl alcohol) used to stabilize the emulsion droplets.

Figure 1. Images of budding and spherical microparticles.

ScEM and TEM (inset images) images of budding (A) and spherical (B) particles generated. Scale bars = 10 μm and 5 μm (inset images).

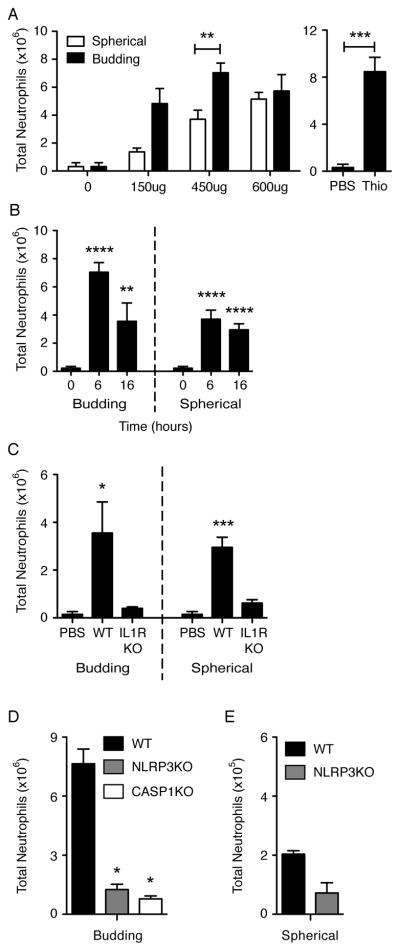

Budding particles stimulate a more robust neutrophil response at early time points in vivo

We first compared the in vivo immune response to budding particles versus spherical particles. Previous studies have shown that intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of particulates (e.g., monosodium urate crystals or titanium particles) lead to an increase in neutrophil recruitment (23, 29). To determine whether our polymer microparticles induced a similar increase in neutrophil recruitment, wild-type (WT) mice were first injected i.p. with budding or spherical particles at 3 different doses: approximately 6.7 × 105, 2 × 106, and 2.7 × 106 particles (150 μg, 450 μg, and 600 μg, respectively) and lavage of the peritoneal cavity was analyzed for neutrophil influx 6 h later. We found that the 450 μg dose of budding particles induced significantly higher neutrophil recruitment (Ly6G+, 7/4+ cells) over spherical particles (Fig. 2 A, P < 0.01, budding versus spherical). In fact, 450 μg budding particles induced neutrophil recruitment at levels similar to injection with the positive control, thioglycollate (Fig. 2 A, P < 0.001, PBS versus Thio). Next, we compared the neutrophil recruitment to 450 μg particles at 6 or 16 h after injection. Both budding and spherical particles induced a significant neutrophil response over PBS-carrier only at 6h (P < 0.0001, both) and 16h (P < 0.01, budding; P < 0.0001, spherical) (Fig. 2 B). Budding particles exhibited significantly higher levels of neutrophil recruitment than spherical particles at 6 h but only slightly higher levels at 16 h when compared to spherical particles (Fig. 2 A, B).

Figure 2. Particle-induced neutrophil recruitment depends on surface curvature and requires IL-1R and NLRP3 inflammasome-associated signaling.

Flow cytometric analysis on peritoneal neutrophil (Ly6G+, 7/4+ cells) recruitment at 6 h (A, D, E), 16 h (C), or at given times (B) after microparticle injections at varying doses as indicated (A) or at a fixed dose of 2 × 106 particles; approx. 450 μg (B, C, D, E) in WT (C57BL/6), IL-1RKO, NLRP3KO, or CASP1KO mice. Graphs show mean + SEM of total number of mice indicated below, performed in 2–3 independent experiments. Y-axis scales are (x106) (A-D) or (x105) (E). Number of mice: (A) PBS (0), n=4; 150ug, n=2; 450ug, n=6 (Spher) and 8 (Bud); 600ug, n=2 (Spher) and 3 (Bud); Thio, n=3. (B) 0, n=9; 6B, n=8; 6S, n=6; 16B, n=5; 16S, n=5. (C) PBS, n=5; WT, n=5; KO, n=3. (D) n=2. Significance values are shown as Budding versus Spherical or Thio versus PBS (A), particle versus PBS injections (B), PBS versus particle injections (C), or KO versus WT (D). ****, P < 0.0001; *** P < 0.001; ** P < 0.01; * P < 0.05.

Microparticle-induced neutrophil recruitment involves IL-1 associated signaling

The IL-1R is required for neutrophil recruitment following exposure to stimulants/particulates in mice (22, 23, 29, 40). To determine whether the IL-1R was required for microparticle-induced neutrophil influx, IL-1R KO mice and WT mice were injected with budding or spherical particles for 16 h and compared to PBS alone injections. As predicted, IL-1R KO mice did not recruit neutrophils in response to particles over PBS alone, whereas WT mice exhibited a significant increase over PBS (Fig. 2 C, P < 0.05, budding; P < 0.001, spherical).

NLRP3 inflammasome is critical for microparticle-induced neutrophil recruitment

The NLRP3 inflammasome plays a role in the response to particulate materials (22–29) through IL-1R and IL-1β secretion. To determine if components of the NLRP3 inflammasome were required for particle-induced neutrophil recruitment, we examined peritoneal neutrophil recruitment to budding particles in NLRP3 KO and CASP1 KO mice and to spherical particles in NLRP3 KO mice 6 h following particle injections. When budding particles were injected, we found that the NLRP3 KO and CASP1 KO mice exhibited significantly blunted neutrophil recruitment, compared to WT controls in response to budding particles (Fig. 2 D, P < 0.05, WT versus all KOs). Again, spherical particles induced substantially less neutrophil recruitment than budding particles (Fig. 2E). The neutrophil response to spherical particles was also inhibited in NLRP3 KO compared to WT mice, although trending did not reach statistical significance with a P value of 0.0674.

Budding particles stimulate more IL-1β than spherical particles

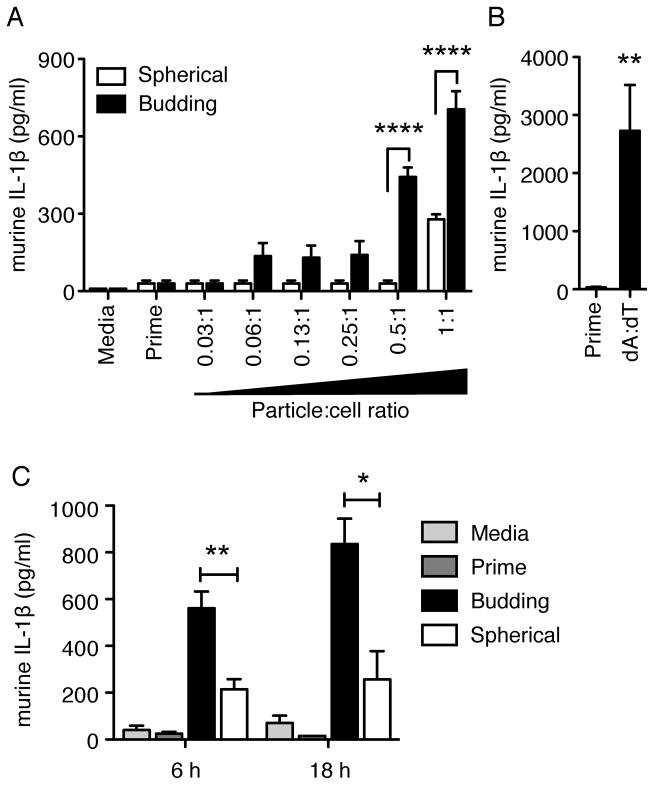

To determine if the observed IL-1R- and NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent neutrophil influx in vivo exhibited similar characteristics in vitro, we analyzed the IL-1β inflammasome response of murine macrophages to microparticles. Immortalized macrophages from WT mice were primed for 3 h with LPS to induce up-regulation of pro-IL-1β transcription, then incubated with budding or spherical microparticles for 6 h to induce pro-IL-1β processing to mature IL-1β. Levels of mature, secreted IL-1β were measured via ELISA using cell supernatants. As predicted by the neutrophil recruitment studies, budding particles were able to induce significantly higher levels of IL-1β secretion (Fig. 3 A, black bars, P < 0.0001, 0.5:1 and 1:1) compared to spherical particles (Fig. 3 A, white bars). WT macrophages responded to both types of microparticles in a dose-dependent manner with significantly higher levels of secreted IL-1β compared to priming alone at the 1:1 particle:cell ratio (4.5 × 105 particles) for both types of particles as well as the 0.5:1 particle:cell ratio (2.25 × 105 particles) for budding particles (Fig. 3 A). As a positive control, macrophages were transfected with synthetic double-stranded DNA, poly-dA:dT (dA:dT). WT macrophages produced a significant amount of IL-1β in response to dA:dT stimulation (Fig. 3 B, P < 0.01). As negative controls, supernatants from macrophages that received media or an LPS prime alone did not exhibit an increase in IL-1β production. Levels of NLRP3-independent cytokine IL-6 were equivalent for all samples (Supplemental Fig. 1 A). Since the neutrophil response seen with budding particles was similar to spherical particles at 16 h in vivo, we also examined the in vitro kinetics of the IL-1β response to microparticles. Unlike neutrophil recruitment, budding particles stimulated higher levels of IL-1β at all time points compared to spherical particles (Fig. 3 C, P < 0.01, 6 h; P < 0.05, 16 h).

Figure 3. Particle-induced IL-1β cytokine secretion is dependent on surface curvature.

Secreted IL-1β levels from WT immortalized mouse macrophages. Cells were incubated with media alone (media) or primed with LPS for 3h (prime), then stimulated with budding or spherical particles with increasing particle-to-cell ratios (particle number:cell number; 1:1, ~100μg) (A) or transfected with 400 ng poly dA:dT (B) for 6 h. Kinetics of IL-1β secretion from 100 μg budding or spherical particles (C). Cytokine levels are reported as mean + SEM and are representative of two independent experiments performed in duplicate. Significance values are shown as budding versus spherical (A, C), or Prime versus dA:dT (B). ****, P < 0.0001; **, P < 0.01; * P< 0.05.

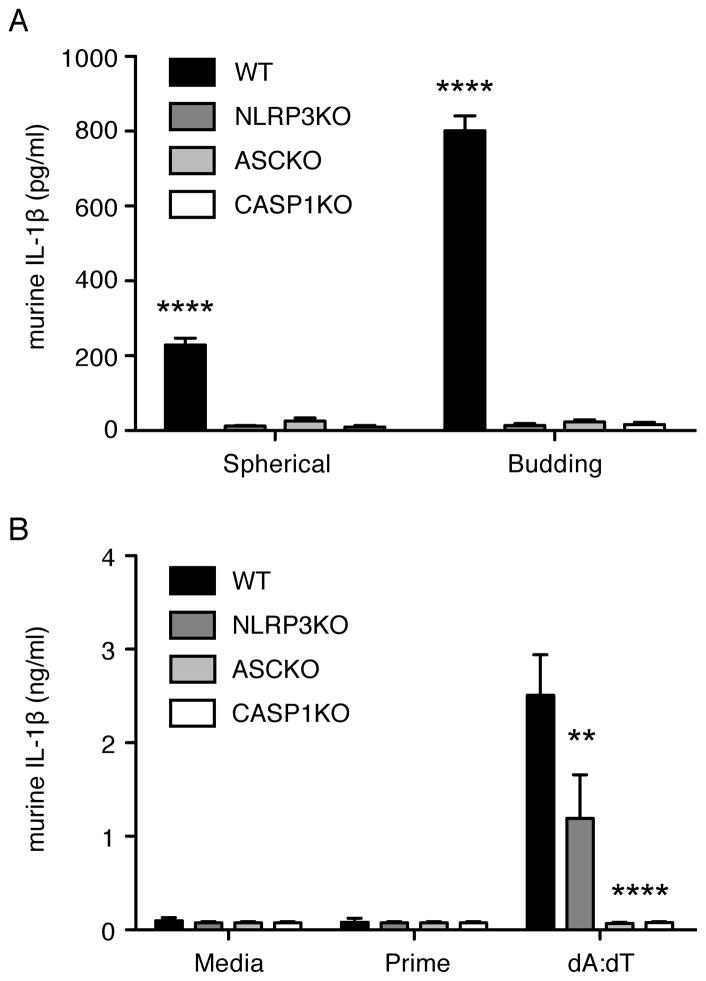

Microparticle-induced IL-1β production requires the NLRP3 inflammasome

In order to further determine if the NLRP3 inflammasome signaling complex was involved in the IL-1β response to microparticles in macrophages, immortalized macrophages generated from NLRP3 KO, ASC KO, and CASP1 KO mice were analyzed for IL-1β production in response to microparticle stimulation. Supernatants from NLRP3 KO, ASC KO, and CASP1 KO macrophages each exhibited undetectable levels of secreted IL-β in response to budding and spherical microparticles while IL-1β secretion from WT macrophages was readily detected (Fig. 4 A, P < 0.0001, WT versus all KOs). As expected, NLRP3 KO macrophages could respond to dA:dT similar to WT cells, while ASC KO and CASP1 KO macrophages could not (Fig. 4 B, P < 0.01, NLRP3 versus WT; P < 0.0001, ASC/CASP1 KO versus WT). WT and deficient cells also produced equivalent levels of the inflammasome-independent cytokine, IL-6 (Supplemental Fig. 1 B), following LPS stimulation.

Figure 4. Particle-induced IL-1β cytokine release requires the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Secreted IL-1β levels from immortalized mouse macrophages from WT, NLRP3 KO, ASC KO, and CASP1 KO mice that were primed for 3 h with LPS (Prime) then stimulated with 4.5 × 105 (1:1 particle:cell ratio) spherical or budding microparticles for 6 h (A) or transfected with poly dA:dT (B). Cytokine levels are reported as mean + SEM and are representative of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Significance values are shown as WT versus KO. ****, P < 0.0001; **, P< 0.01.

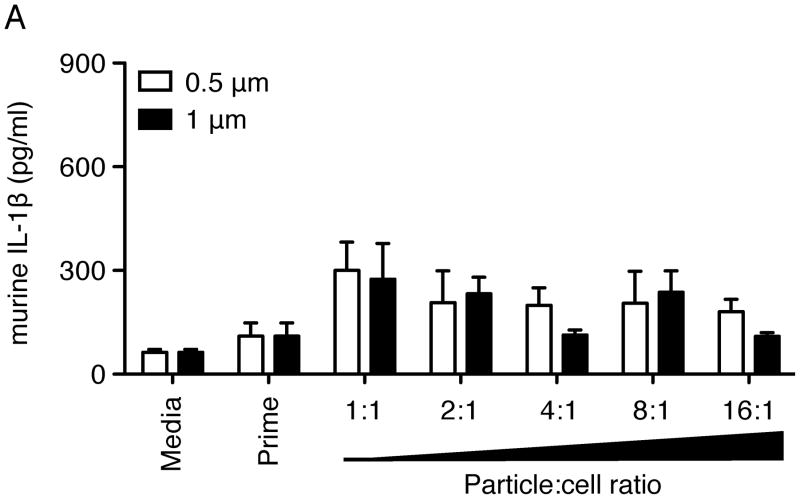

Small, spherical particles do not induce significant IL-1β secretion

Studies have shown that particles within the range of 1–3 μm in diameter exhibit the highest phagocytic rates when incubated with macrophages (19–21). The ‘buds’ on the budding particles are approximately 1–2 μm in diameter. In order to determine if the presence of these small ‘buds’ is responsible for the increased IL-1β secretion exhibited by budding particles when compared to spherical particles, we also tested the response to smaller spherical particles with diameters of 0.5 μm and 1 μm, the surfaces of which were also coated with PEO. These smaller spherical particles were incubated with WT immortalized macrophages and assayed for IL-1β secretion. Unlike the budding particles, these small (bud-sized) spherical particles did not induce a significant amount of IL-1β secretion above prime-only background values (Fig. 5), even at high particle-to-cell ratios. All samples exhibited similar levels of NLRP3 independent cytokine IL6 (Supplemental Fig. 1C) following LPS prime. Of note, uncoated 0.5 μm and 1 μm PS particles were also unable to induce significant IL-1β secretion over prime-only levels (data not shown).

Figure 5. Small spherical particles do not induce IL-1β secretion.

Secreted IL-1β levels from WT immortalized mouse macrophages. Cells were incubated with media alone (media) or primed with LPS for 3 h (prime), then stimulated with small spherical particles (0.5 μm or 1 μm diameter) for 6 h with increasing particle-to-cell ratios (particle number:cell number; 1:1, ~100 μg). Cytokine levels are reported as mean + SEM and are representative of two independent experiments performed in duplicate.

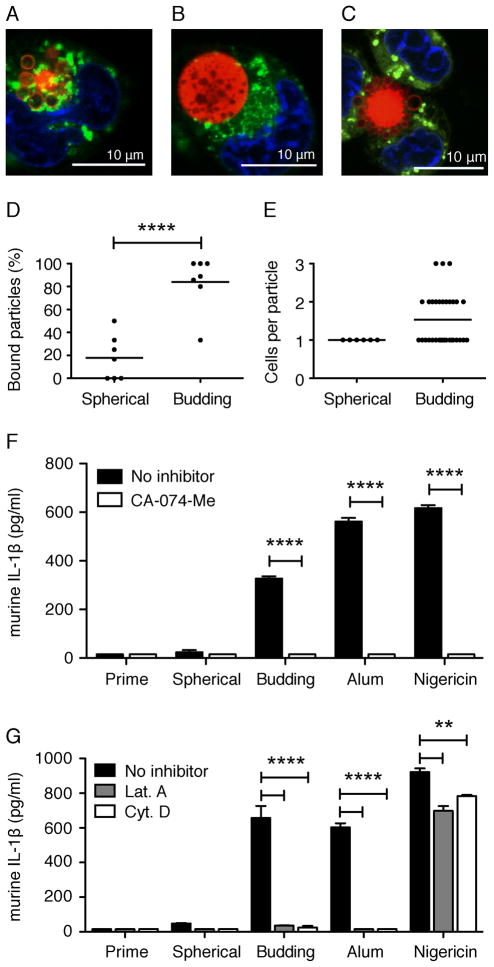

Budding particles are more likely to be associated with and internalized in mouse macrophages than spherical particles

Since inflammasome activation of IL-1β release generally involves phagocytosis of the stimulant, we examined the ability of macrophages to attach to and internalize spherical and budding particles. To visualize phagocytosis of microparticles, immortalized macrophages from WT mice were incubated for 6 h with budding or spherical microparticles containing a fluorescent dye, Vibrant DiI. Using confocal microscopy, we found that a significantly higher percentage of budding particles (>85%) bound to or internalized in macrophages (Fig. 6A, C, D) when compared to spherical particles, where only approximately 20% were bound or internalized (Fig. 6B, D, P<0.0001, budding versus spherical). We also found that budding particles were associated with more macrophages on a per particle basis, with the majority of budding particles associated with 2–3 macrophages each. In other words, a single budding particle was often associated with more than one macrophage at a time (Fig. 6 C, E). In contrast, a single spherical particle only associated with a single macrophage (Fig. 6 B, E). This data is trending towards significance with a P-value of 0.0632. As internal controls, the total number of cells per field of view and number of particles per field of view were very similar between spherical and budding particles, while the absolute number of bound budding particles was still significantly higher than bound spherical particles (Supplemental Fig. 2A–C, P < 0.01, bound budding versus spherical).

Figure 6. Particle phagocytosis: Budding particles associate with more macrophages than spherical particles.

Confocal microscopy images of macrophage-associated budding (A,C) and spherical (B) particles following a 3 h prime with LPS and 6 h incubation with particles. Lysosomes were visualized with LysoTracker Green. Nuclei were visualized with Hoechst 34580 (blue). Scale bars = 10 μm. Images were taken with a x63 objective. Percent of and average (line) particles bound to macrophages per field of view (D). Total and average (indicated by line) number of macrophages associated with a single particle per field of view (E). Analysis was performed on seven independent fields of view per particle type. Secreted IL-1β from WT immortalized macrophages stimulated for 6 h (F) or 18 h (G) with 100μg budding or spherical particles, 130 μg/ml alum, or 5 μM nigericin in the presence (white bars) or absence (black bars) of 50 μM CA-074-Me (F), 250 nM Latrunculin A (Lat. A), or 1 μM Cytochalasin D (Cyt. D) (G). Cytokine levels are reported as mean + SEM and are representative of two independent experiments performed in duplicate. Significance values are shown as budding versus spherical particles (D) or untreated versus treated cells (F, G). ****, P < 0.0001; **, P< 0.01.

Optimal inflammasome activation in response to silica crystals, alum, amyloid-β, and titanium requires uptake through actin polymerization and release of cathepsin B following lysosomal destabilization (22, 29, 41). To determine whether actin polymerization and cathepsin B are required for inflammasome activation and subsequent IL-1β production in response to microparticles, WT immortalized mouse macrophageswere treated with the cathepsin B inhibitor CA-074-Me or actin inhibitors Latrunculin A (Lat. A) and Cytochalasin D (Cyt. D). Supernatants from cells pre-treated with CA-074- Me had substantially lower levels of IL-1β following a 6 h microparticle stimulation compared to untreated cells (Fig. 6 F, P < 0.0001, untreated versus treated). Additionally, cells pre-treated with Lat. A or Cyt. D exhibited a complete loss of IL-1β following an 18 h microparticle stimulation (Fig. 6 G, P < 0.0001, untreated versus treated). As expected, alum induced IL-1β requires both cathepsin B and actin (Fig. 6 F, G, P < 0.0001, untreated versus treated, all), whereas nigericin, a potassium ionophore known to induce IL-1β through potassium efflux, lysosomal destabilization and cathepsin B release (42), requires cathepsin B but does not require actin polymerization (Fig. 6 F, G, P < 0.0001, CA-074-Me treatment and P < 0.01, Lat. A and Cyt. D treatments). Furthermore, macrophages that were transfected with double-stranded DNA, poly-dA:dT (dA:dT), which induces mature IL-1β production in a NLRP3-independent manner (43), were unaffected by cathepsin B inhibition (data not shown).

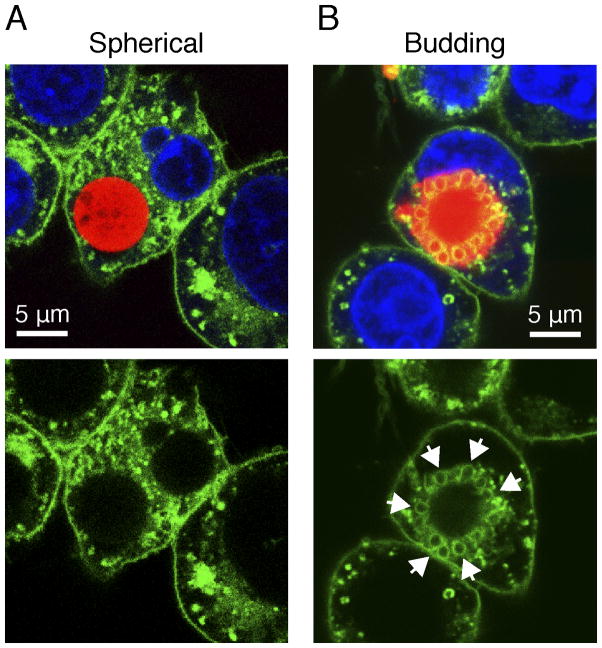

Budding particles localize with lipid raft components

Recruitment of lipid rafts plays an important role in phagocytosis and inflammatory cytokine secretion by anchoring scavenger receptors, innate immune receptors (such as CD14 and Dectin-1) during activation of downstream kinases (44–46). Additionally, we have previously shown that uptake of antibody-bound membrane proteins can internalize via clathrin through the endosomal pathway (47). In order to further elucidate the mechanisms involved in particle internalization, WT macrophages were stained with fluorescent cholera toxin subunit B (CTxB), which binds to GM1 gangliosides on the cell surface, as a marker for lipid rafts. Cells were then incubated with fluorescent particles for 6 h. We found that the surface of budding particles highly localized with CTxB (arrows), whereas spherical particles did not (Fig. 7). Overall, our studies identify an important role for surface texturing in microparticle phagocytosis and NLRP3 activation, ultimately leading to neutrophil recruitment (illustrated in Fig. 8).

Figure 7. Internalized budding particles localize with lipid raft components.

Confocal microscopy images of macrophage-associated spherical (A) and budding (B) particles. Cells were incubated with particles for 6 h, then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min prior to visualization. Lipid rafts were visualized with CTxB-Alexa 488 (green). Nuclei were visualized with Hoechst 34580 (blue). Arrows indicate localization of lipid rafts with particle. Images are representative of two independent experiments. Scale bars = 5 μm. Images were taken with a x63 objective.

Figure 8. Particle-induced inflammasome activation and neutrophil recruitment.

Particle internalization, via actin polymerization, triggers the release of cathepsin B from lysosomes, which together activate NLRP3. Activated NLRP3 recruits ASC through PYD domain interactions. This complex triggers recruitment and cleavage of activated caspase-1 through caspase activation and recruitment domain (also known as CARD) interactions. This inflammasome complex then cleaves pro-IL-1β into its active, secreted form IL-1β, which can trigger downstream IL- 1 associated signaling, including neutrophil recruitment, through activation of the IL-1R.

DISCUSSION

This study illustrates a significant role for surface texturing in polymer microparticle-induced inflammasome stimulation, both in vivo and in vitro independent of the chemical composition of the particle (Figure 8). The use of macrophage cell lines allowed us to interrogate the potential pathways triggered by particles and revealed roles for NLRP3, ASC, CASP1, and IL-1R and suggest that budding particles induce a significantly greater inflammasome response than spherical particles. These observations have been validated in vivo using neutrophil recruitment, confirming the importance of these pathways in vivo and supporting our hypothesis that surface texture is an important determinant of inflammasome activation by particles.

We, and others, have demonstrated a critical role for IL-1-associated signaling in neutrophil responses following injections of particulate stimuli (22, 23, 29, 40). Here we show that IL-1R KO mice exhibit a diminished neutrophil response following microparticle injections, further implicating IL-1 signaling in the innate immune response to budding and spherical polymer microparticles. Furthermore, we verify that this response also requires a functional NLRP3 inflammasome, as NLRP3 KO and CASP1 KO mice were unable to recruit a significant amount of neutrophils following particle injections. It is possible that sensors in addition to NLRP3 may play a role in particle induced neutrophil recruitment and this may account for the lack of a complete abolition of neutrophil recruitment in KO mice. However, regardless of whether NLRP3 is the only inflammasome receptor or one of several inflammasome receptors that are triggered by particles, these studies clearly demonstrate that the downstream ASC and CASP1 pathways and the IL-1R pathway are very important for neutrophil responses to budding and spherical particles.

We determined that although there is some variation in the amount of IL-1β detected in macrophage supernatants, spherical particles consistently and reproducibly induced significantly less IL-1β then budding particles in every experiment in side-by-side comparisons. Particle IL-1β induction also occurs through activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome-signaling complex, similar to that seen with other particulate stimuli (22–29). Our kinetic studies in vitro also indicate that budding particles induced an early peak and continued high IL-1β secretion over time, whereas spherical particles induced lower IL-1β secretion levels that remained relatively constant. In vivo, it is unclear why spherical particles appear to “catch up” with budding particles for neutrophil recruitment at later time points. There is likely a complex interplay between a variety of signals in vivo, including the magnitude of inflammasome activation for IL-1β secretion, levels of IL-1β produced, IL-1β-driven neutrophil recruitment and adherence of activated neutrophils to peritoneal tissues and/or pyroptosis/necrosis of highly activated neutrophils.

Budding particles also induced a more rapid phagocytic response in vitro and were more readily taken up by macrophages than spherical particles, again suggesting that the shape of the particle affects the kinetics of the innate immune response. Our studies revealed that large (7–8 μm) polymer particles are efficiently associated with and phagocytosed by macrophages. We also noted higher concentrations of lysosomes surrounding the engulfed budding particles suggesting that the budding particles trigger a stronger cellular response. Our findings corroborate recent studies indicating that macrophages are more likely to internalize particles if they contain regions of high positive surface curvature (15–19). Budding particles are presumably phagocytosed more efficiently because they contain higher local surface curvature compared to spherical particles of the same overall dimensions.

While particle uptake is an important parameter for drug delivery, triggering of inflammatory responses may not require complete uptake of the particle. In fact, pathogenic crystals of uric acid, silica, beta-amyloid or cholesterol have all been shown to trigger inflammasome activation and IL-1β release by a “frustrated phagocytosis” mechanism (22, 41). The current view is that macrophages attempting to engulf large crystals form a phagolysosome around the crystal. However, in the process of engulfing very large crystals the lysosomal membranes are ruptured, thus releasing enzymes into the cytosol that trigger cytosolic inflammasomes as a result. Our data showing multiple cells associated with a single budding particle is consistent with this proposed mechanism. However, whether budding particles are completely phagocytosed or partially phagocytosed by several cells, it is still clear that actin polymerization and cathepsin B release is necessary for IL-1β induction, as inhibitors to either completely abolish the particle induced IL-1β response.

In addition to triggering a stronger cellular response, it’s possible that budding particles internalize through a different mechanism of phagocytosis than spherical particles. The process of phagocytosis can occur through one of several different cell surface proteins, including complement receptors, Fc-receptors, pathogen-specific receptors, and scavenger receptors (2, 3). Studies have indicated that scavenger receptors and caveolae/lipid rafts are involved in the internalization of a variety of therapeutic agents (48), bacteria (8, 49), and artificial particles like latex, TiO2, silica and polystyrene particles (9–11, 50). Using CTxB as a marker for lipid rafts, our findings indicate that particles with high surface curvature (budding particles) recruit lipid rafts during internalization, while particles with lower surface curvature (spherical particles) do not. These findings suggest that particles can potentially be tailored to internalize through a specific phagocytosis pathway, based on surface curvature.

Several studies have reported that small particles induce the highest amount of IL-1β from immune cells (19–21, 28). One possibility for the increased phagocytosis and increased IL-1β production seen with budding particles compared to spherical particles is that the 1–2 μm diameter ‘buds’ mimic smaller particles. However, our findings indicate that small, spherical particles in the 0.5-1 μm diameter range do not induce significant IL-1β secretion (whether PEO-derivatized or not). It is clear that the immune response to particles with textured surfaces is more complicated than predicted by models based on size alone. The combination of regions of high positive and negative surface curvatures to form the more complex surfaces of the budding particles is apparently responsible for induction of high levels of IL-1β.

These findings also clearly demonstrate that not all phagocytes are created equal, a concept that becomes clear when comparing studies on particle stimulation. For example, Sharp et al. have suggested that particles in the range of 0.5–1 μm in diameter induce the highest amount of IL-1β in dendritic cells (28). Other studies have shown that particles of 1–3 μm in diameter exhibited the highest phagocytic rates when incubated with J774 mouse macrophages (19), rat alveolar macrophages (20), and peritoneal mouse macrophages (21). We have demonstrated that immortalized mouse macrophages, which have been used for inflammasome activation studies to a variety of particulate material (22, 29), appear to respond differently (and very weakly) to small, spherical particles when compared to the response from murine dendritic cells, peritoneal macrophages, and rat alveolar macrophages.

Overall, the data presented in this report have broad implications for the future development of vaccine adjuvants and therapeutic delivery agents, as variation in surface curvature will modulate the resultant immune response. We suggest that larger biodegradable particles with low surface curvature and no complex surface structures would be ideal for use as delivery vehicles, as they exhibit a low level of uptake and induce a slow immune response, and thus, may exhibit a broader biodistribution, ideal for delivery of therapeutic agents. On the other hand, we suggest that particles with high surface curvature and complex surface structure would be ideal for use as vaccine adjuvants, as they are more efficiently phagocytosed in cells and induce a more robust immune response. Thus both the chemical composition-dependent receptor engagement and surface texture-dependent inflammasome activation are key elements determining the uptake and immune activation potential of particles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Melvin Chan and Megan Munroe for technical assistance and Melanie Trombly for critical review of this manuscript. We would also like to thank Katherine Fitzgerald and Eicke Latz for immortalized macrophages.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grant P01 AI083215-01 to EKJ and NSF grants CBET-0741885 and CBET-0931616 to RCH. Core resources supported by the Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center grant DK32520 were also used.

Abbreviations: NLRP3, Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, leucine rich repeat and pyrin domain containing protein 3; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein; CASP1, Caspase-1; PS-PEO, polystyrene-block-poly(ethylene oxide); ScEM, scanning electron microscopy; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; IL-1R, IL-1 receptor; CTxB, cholera toxin subunit B

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors express no competing financial interests for this work.

References

- 1.Rabinovitch M. Professional and non-professional phagocytes: an introduction. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:85–87. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)88955-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Underhill DM, Ozinsky A. Phagocytosis of microbes: complexity in action. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:825–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.103001.114744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aderem A, Underhill DM. Mechanisms of phagocytosis in macrophages. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:593–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Hagan DT, Valiante NM. Recent advances in the discovery and delivery of vaccine adjuvants. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:727–735. doi: 10.1038/nrd1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Hagan DT, Singh M, Ulmer JB. Microparticle-based technologies for vaccines. Methods. 2006;40:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mundargi RC, V, Babu R, Rangaswamy V, Patel P, Aminabhavi TM. Nano/micro technologies for delivering macromolecular therapeutics using poly(D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) and its derivatives. J Control Release. 2008;125:193–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janeway C. Immunobiology: the immune system in health and disease. Garland Science; New York: 2005. pp. 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elomaa O, Kangas M, Sahlberg C, Tuukkanen J, Sormunen R, Liakka A, Thesleff I, Kraal G, Tryggvason K. Cloning of a novel bacteria-binding receptor structurally related to scavenger receptors and expressed in a subset of macrophages. Cell. 1995;80:603–609. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90514-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palecanda A, Paulauskis J, Al-Mutairi E, Imrich A, Qin G, Suzuki H, Kodama T, Tryggvason K, Koziel H, Kobzik L. Role of the scavenger receptor MARCO in alveolar macrophage binding of unopsonized environmental particles. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1497–1506. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton RF, Jr, Thakur SA, Mayfair JK, Holian A. MARCO mediates silica uptake and toxicity in alveolar macrophages from C57BL/6 mice. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34218–34226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanno S, Furuyama A, Hirano S. A murine scavenger receptor MARCO recognizes polystyrene nanoparticles. Toxicol Sci. 2007;97:398–406. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ip WK, Takahashi K, Moore KJ, Stuart LM, Ezekowitz RA. Mannose-binding lectin enhances Toll-like receptors 2 and 6 signaling from the phagosome. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:169–181. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charriere GM, Ip WE, Dejardin S, Boyer L, Sokolovska A, Cappillino MP, Cherayil BJ, Podolsky DK, Kobayashi KS, Silverman N, Lacy-Hulbert A, Stuart LM. Identification of Drosophila Yin and PEPT2 as evolutionarily conserved phagosome-associated muramyl dipeptide transporters. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:20147–20154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.115584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ip WK, Sokolovska A, Charriere GM, Boyer L, Dejardin S, Cappillino MP, Yantosca LM, Takahashi K, Moore KJ, Lacy-Hulbert A, Stuart LM. Phagocytosis and phagosome acidification are required for pathogen processing and MyD88-dependent responses to Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:7071–7081. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Champion JA, Mitragotri S. Role of target geometry in phagocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4930–4934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600997103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Champion JA, Mitragotri S. Shape induced inhibition of phagocytosis of polymer particles. Pharm Res. 2009;26:244–249. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9626-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Zon JS, Tzircotis G, Caron E, Howard M. A mechanical bottleneck explains the variation in cup growth during Fc gamma R phagocytosis. Molecular Systems Biology. 2009;5:298. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Decuzzi P, Godin B, Tanaka T, Lee SY, Chiappini C, Liu X, Ferrari M. Size and shape effects in the biodistribution of intravascularly injected particles. Journal of Controlled Release. 2010;141:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doshi N, Mitragotri S. Macrophages Recognize Size and Shape of Their Targets. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Champion JA, Walker A, Mitragotri S. Role of particle size in phagocytosis of polymeric microspheres. Pharm Res. 2008;25:1815–1821. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9562-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tabata Y, Ikada Y. Effect of the size and surface charge of polymer microspheres on their phagocytosis by macrophage. Biomaterials. 1988;9:356–362. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(88)90033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:847–856. doi: 10.1038/ni.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen CJ, Shi Y, Hearn A, Fitzgerald K, Golenbock D, Reed G, Akira S, Rock KL. MyD88-dependent IL-1 receptor signaling is essential for gouty inflammation stimulated by monosodium urate crystals. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2262–2271. doi: 10.1172/JCI28075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caicedo MS, Desai R, McAllister K, Reddy A, Jacobs JJ, Hallab NJ. Soluble and particulate Co-Cr-Mo alloy implant metals activate the inflammasome danger signaling pathway in human macrophages: A novel mechanism for implant debris reactivity. J Orthop Res. 2008;27:847–854. doi: 10.1002/jor.20826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Willingham SB, Ting JP, Re F. Cutting edge: inflammasome activation by alum and alum’s adjuvant effect are mediated by NLRP3. J Immunol. 2008;181:17–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisenbarth SC, Colegio OR, O’Connor W, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA. Crucial role for the Nalp3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature. 2008;453:1122–1126. doi: 10.1038/nature06939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharp FA, Ruane D, Claass B, Creagh E, Harris J, Malyala P, Singh M, O’Hagan DT, Petrilli V, Tschopp J, O’Neill LA, Lavelle EC. Uptake of particulate vaccine adjuvants by dendritic cells activates the NALP3 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:870–875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804897106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.St Pierre CA, Chan M, Iwakura Y, Ayers DC, Kurt-Jones EA, Finberg RW. Periprosthetic osteolysis: Characterizing the innate immune response to titanium wear-particles. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:1418–1424. doi: 10.1002/jor.21149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masumoto J, Taniguchi S, Ayukawa K, Sarvotham H, Kishino T, Niikawa N, Hidaka E, Katsuyama T, Higuchi T, Sagara J. ASC, a novel 22-kDa protein, aggregates during apoptosis of human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33835–33838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mariathasan S, Newton K, Monack DM, Vucic D, French DM, Lee WP, Roose-Girma M, Erickson S, Dixit VM. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature. 2004;430:213–218. doi: 10.1038/nature02664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mariathasan S, Monack DM. Inflammasome adaptors and sensors: intracellular regulators of infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:31–40. doi: 10.1038/nri1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinon F, Tschopp J. NLRs join TLRs as innate sensors of pathogens. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Curtsinger JM, Schmidt CS, Mondino A, Lins DC, Kedl RM, Jenkins MK, Mescher MF. Inflammatory cytokines provide a third signal for activation of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:3256–3262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pape KA, Khoruts A, Mondino A, Jenkins MK. Inflammatory cytokines enhance the in vivo clonal expansion and differentiation of antigen-activated CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:591–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pisani E, Ringard C, Nicolas V, Raphael E, Rosilio V, Moine L, Fattal E, Tsapis N. Tuning microcapsules surface morphology using blends of homo- and copolymers of PLGA and PLGA-PEG. Soft Matter. 2009;5:3054–3060. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu J, Hayward RC. Hierarchically structured microparticles formed by interfacial instabilities of emulsion droplets containing amphiphilic block copolymers. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:2113–2116. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harper GR, Davis SS, Davies MC, Norman ME, Tadros TF, Taylor DC, Irving MP, Waters JA, Watts JF. Influence of surface coverage with poly(ethylene oxide) on attachment of sterically stabilized microspheres to rat Kupffer cells in vitro. Biomaterials. 1995;16:427–439. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)98815-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunn SE, Brindley A, Davis SS, Davies MC, Illum L. Polystyrene-poly (ethylene glycol) (PS-PEG2000) particles as model systems for site specific drug delivery. 2. The effect of PEG surface density on the in vitro cell interaction and in vivo biodistribution. Pharmaceutical Research. 1994;11:1016–1022. doi: 10.1023/a:1018939521589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen CJ, Kono H, Golenbock D, Reed G, Akira S, Rock KL. Identification of a key pathway required for the sterile inflammatory response triggered by dying cells. Nat Med. 2007;13:851–856. doi: 10.1038/nm1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halle A, Hornung V, Petzold GC, Stewart CR, Monks BG, Reinheckel T, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Moore KJ, Golenbock DT. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:857–865. doi: 10.1038/ni.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hentze H, Lin XY, Choi MS, Porter AG. Critical role for cathepsin B in mediating caspase-1-dependent interleukin-18 maturation and caspase-1-independent necrosis triggered by the microbial toxin nigericin. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:956–968. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muruve DA, Petrilli V, Zaiss AK, White LR, Clark SA, Ross PJ, Parks RJ, Tschopp J. The inflammasome recognizes cytosolic microbial and host DNA and triggers an innate immune response. Nature. 2008;452:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature06664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goodridge HS, Reyes CN, Becker CA, Katsumoto TR, Ma J, Wolf AJ, Bose N, Chan AS, Magee AS, Danielson ME, Weiss A, Vasilakos JP, Underhill DM. Activation of the innate immune receptor Dectin-1 upon formation of a ‘phagocytic synapse’. Nature. 2011;472:471–475. doi: 10.1038/nature10071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Solomon KR, Kurt-Jones EA, Saladino RA, Stack AM, Dunn IF, Ferretti M, Golenbock D, Fleisher GR, Finberg RW. Heterotrimeric G proteins physically associated with the lipopolysaccharide receptor CD14 modulate both in vivo and in vitro responses to lipopolysaccharide. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1998;102:2019–2027. doi: 10.1172/JCI4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmitz G, Orso E. CD14 signalling in lipid rafts: new ligands and co-receptors. Current opinion in lipidology. 2002;13:513–521. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.St Pierre CA, Leonard D, Corvera S, Kurt-Jones EA, Finberg RW. Antibodies to cell surface proteins redirect intracellular trafficking pathways. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2011.05.011. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Unruh TL, Li H, Mutch CM, Shariat N, Grigoriou L, Sanyal R, Brown CB, Deans JP. Cholesterol depletion inhibits src family kinase-dependent calcium mobilization and apoptosis induced by rituximab crosslinking. Immunology. 2005;116:223–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naroeni A, Porte F. Role of cholesterol and the ganglioside GM(1) in entry and short-term survival of Brucella suis in murine macrophages. Infection and immunity. 2002;70:1640–1644. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.3.1640-1644.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagao G, Ishii K, Hirota K, Makino K, Terada H. Role of lipid rafts in phagocytic uptake of polystyrene latex microspheres by macrophages. Anticancer research. 2010;30:3167–3176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.