Abstract

Objective

Functional impairment resulting from a stroke frequently requires the care of a family caregiver, often the spouse. This change in the relationship can be stressful for the couple. Thus, this study examined the longitudinal, dyadic relationship between caregivers’ and stroke survivors’ mutuality and caregivers’ and stroke survivors’ perceived stress.

Method

This secondary data analysis of 159 stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers utilized a cross-lagged, mixed models analysis with the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) to examine the dyadic relationship between mutuality and perceived stress over the first year post discharge from inpatient rehabilitation.

Results

Caregivers’ mutuality showed an actor effect (β = −3.82, p < .0001) but not a partner effect. Thus, caregivers’ mutuality influenced one’s own perceived stress but not the stroke survivors’ perceived stress. Stroke survivors’ perceived stress showed a partner effect and affected caregivers’ perceived stress (β=.13, p=.047). Caregivers’ perceived stress did not show a partner effect and did not significantly affect stroke survivors’ perceived stress.

Conclusion

These findings highlight the interpersonal nature of stress in the context of caregiving for a spouse. Caregivers are especially influenced by perceived stress in the spousal relationship. Couples should be encouraged to focus on positive aspects of the caregiving relationship to mitigate stress.

Keywords: stroke, caregiving, perceived stress, mutuality, dyadic analysis

Introduction

When illness strikes a relationship it not only affects the person with the illness but their spouse as well (Acitelli & Badr, 2005). This is especially the case with stroke as the spouse often becomes the primary caregiver (Han & Haley, 1999). The change in role from spouse to spousal caregiver can have varied effects on the stroke survivor, the caregiver, and on their marital relationship (Coombs, 2007; Draper & Brocklehurst, 2007; Forsberg-Warleby, Moller, Blomstrand, 2001; Visser-Meily et al., 2006).

Worldwide, approximately 30.7 million people are living with stroke and 9 million more occur every year. Those who are fortunate enough to live through a stroke often face serious, long term disability (Fisher & Norrving, 2011). Due to the significant physical and cognitive impairments that stroke survivors face, many stroke survivors are unable to care for themselves in the weeks, months, and possibly years following their stroke. Many stroke survivors are discharged into the care of a family member, often their spouse or committed partner. Spousal caregivers usually provide the bulk of the patient’s care which can result in significant physical and emotional strain (Visser-Meily et al., 2006).

Following a stroke, stroke survivors, and their caregivers, may be suddenly forced to adapt to physical and cognitive impairments (Fisher & Norrving, 2011); these changes can be very stressful for both stroke survivors and their loved ones who are thrust unprepared into a caregiving role (Haley et al., 2009; Ostwald, Bernal, Cron, & Godwin, 2009). Brain-injuries, such as stroke, have been shown to significantly affect the psychological well-being of patient’s family members (Holmes & Deb, 2003). A study of caregivers of stroke survivors found caregivers to report self-identified stressors in three main domains: stroke-related behavior and impairment, living and working environment, and caregiver’s physical and psychological well-being (Williams, 1994). A qualitative study of caregivers of stroke survivors found caregiver distress to begin soon after the initiation of caregiving and to last for more than a year after the stroke. In addition, they found caregivers to report psychological distress 2.5 times more than non-caregivers (Simon, Kumar, & Kendrick, 2009). Stress is more often studied and reported on for caregivers than for stroke survivors. However, because of the many changes and challenges that stroke survivors face following a stroke, it is clear that stoke survivors experience psychological stress as well (Ostwald, et al. 2009). Moreover, a study of educational needs of stroke survivors reported the areas that stroke survivors wanted the most knowledge was about reducing the risk of a subsequent stroke and coping with stress (van Veenendaal, Grinspun, & Adriaanse, 1996).

In addition to the psychological stress of a stroke, the couple might have to adjust to changing roles within their relationship. Spousal caregivers simultaneously adjust to physical and cognitive changes in the stroke survivor and changes in their marital relationship, oftentimes leading to decreased marital satisfaction for the spousal caregiver (Blonder, Langer, Pettigrew, & Garrity, 2007; Chadiha, Rafferty, & Pickard, 2003; Forsberg-Warleby, Moller, Blomstrand, 2004). A study of male, mild stroke patients and their female, spousal caregivers reported that while caregiver strain improved over time, marital function, as measured by the Family Assessment Device (FAD), declined for both members of the couple (Green & King, 2010). Similarly, a meta-ethnographic review of qualitative studies found caregivers to experience biographical disruption (Greenwood & Mackenzie, 2010); meaning that due to the changes and losses that caregivers have in roles, relationships, autonomy, responsibility, and future plans, caregivers’ perception of themselves is challenged as they shift from a partner to a caregiver. These changes, losses and resulting change in perception of one’s self lead caregivers to a re-evaluation of themselves and a new way of life (Greenwood & Mackenzie, 2010).

Despite the challenges that a couple may face while coping with a stroke, not all aspects of giving or receiving care are negative. An epidemiologically based study of stroke survivors and their family caregivers found that while aspects of caregiving were stressful, the caregivers also derived benefits from caregiving (Haley et al, 2009). Mutuality, conceptualized as a positive aspect of the caregiving relationship, includes such notions as degree of closeness that the caregiver and care receiver feel, the amount of pleasure and comfort derived from the relationship, and the amount of appreciation each person feels for the other (Archbold, Stewart, Greenlick, & Harvath, 1990). Mutuality has been found to improve patient self-reported recovery (Kneeshaw, Considine, & Jennings, 1999), lessen caregiver strain (Archbold et al., 1990), and act as a protective factor in family caregiving relationships (Lyons, Sayer, Archbold, Hornbrook & Stewart, 2007). While lower mutuality among spousal caregivers has been associated with negative caregiver outcomes (Halm & Bakas, 2007) higher caregiver mutuality has been positively correlated with better mental health of both the patient and the caregiver and inversely correlated with higher physical impairments of the patient (Tanji et al., 2008). Additionally, higher stroke survivor mutuality has been associated with lower stroke survivor stress (Ostwald et al., 2009). As could be expected, mutuality is not static but may change over time as the relationship between the couple improves or worsens (Carter, et al., 1998; Kneeshaw et al., 1999; Lyons et al., 2007).

Stroke survivors and caregivers face significant stress following a stroke. Their relationship is affected by and affects their psychological stress. Thus, this study sought to examine the dyadic relationship between caregiver and stroke survivor mutuality and stress over the first year post discharge using the Actor Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) (Kenny, 1996). While studies have reported on stress and mutuality of stroke survivors and caregivers, no study has reported the longitudinal, dyadic effects of stroke survivor and caregiver mutuality on stroke survivor and caregiver stress. Specifically, this study sought to answer the following research questions: In the first year post hospital discharge, does higher spousal caregiver mutuality, when examined in the context of stroke survivor mutuality, result in lower caregiver stress and lower stroke survivor stress? Similarly, in the first year post hospital discharge, does higher stroke survivor mutuality, when examined in the context of caregiver mutuality, result in lower stroke survivor stress and lower caregiver stress?

Methods

Sample

This study was a secondary data analysis which focused on the dyadic relationship of stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers who were part of a previously completed educational intervention. Committed to Assisting with Recovery after Stroke (CAReS) was a randomized educational intervention that provided stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers with education about recovery from stroke, skill training, counseling, and community linkages via either a home-based or mailed intervention. CAReS showed positive changes in caregivers’ perceptions of their health and coping skills. To be eligible to participate in the CAReS study, dyads had to meet the following eligibility criteria: age 50 or older, one member of the dyad was admitted to acute care from home and had a diagnosis of stroke, the stroke survivor was to be discharged home with the spousal or committed partner caregiver who lived with the stroke survivor, the couple had to reside within 50 miles of the Texas Medical Center, speak English, and have a telephone. Neither member of the dyad could have severe Parkinson’s disease or another severe disability that might interfere with their rehabilitation. Couples were excluded if either had a life expectancy of less than six months or a severe psychiatric pathology. Additionally, stroke survivors with global aphasia or with a diagnosis of dementia were excluded. CAReS did not exclude same sex couples from participating in the study; however, all dyads enrolled in the study were heterosexual.

Measures

Mutuality

The Mutuality Scale measures the positive caregiving relationship between the caregiver and the care receiver (Archbold et al., 1990). Both the caregiver and care receiver answer 15 questions about their relationship on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = a great deal). Questions include, “How close do you feel to him or her?”, “How much do the two of you laugh together?”, and “When you really need it, how much does he or she comfort you?” The total Mutuality Scale score ranges from 0–4 and is the sum of the individual items divided by the number of items answered. High scores indicate the relationship between caregiver and care receiver is characterized by love, shared pleasurable activities, common values, and reciprocity. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for caregivers’ and stroke survivors’ Mutuality Scales in the CAReS study were 0.94 and 0.92, respectively (Ostwald et al., 2009).

Perceived Stress

Because stress is subjective and varies by individual, stroke survivor’s and caregiver’s perceived stress were measured in this study with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), a widely used measure of psychological, subjective stress (Cohen & Wills, 1985). The PSS is a 10-item scale in which individuals rate the extent to which they felt their life to be stressful during the past month by answering questions such as “How often have you felt nervous and “stressed?”, “How often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly?”, “How often have you felt that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?”. Item scores are rated on a 5-point scale (0 = never to 4 = very often). Total PSS scores range from 0 to 40; higher scores suggest higher levels of stress (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). The PSS has demonstrated adequate internal consistency (0.78) and moderate correlations with other measures of perceived stress. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the PSS was 0.85 in the CAReS study (Ostwald et al., 2009).

Demographic information

Demographic information including date of birth, gender and ethnicity of both the caregiver and stroke survivor were collected at baseline. Demographic data were reported by the caregiver and the stroke survivor. Age was calculated as the difference in years from the date of birth to the baseline visit after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Gender was reported as either male or female. Ethnicity was reported as Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, African American, Asian, Native American or other. Subjects could choose as many ethnicity categories as were appropriate. Additionally, highest educational level completed and occupation were collected on both the caregiver and the stroke survivor. These data were used with the Four-factor Hollingshead scale (Hollingshead, 1979) to calculate socioeconomic status (SES) of the dyad.

Procedures

CAReS was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston as well as the IRB’s of the health care systems from which the subjects were recruited. Stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers were recruited from hospitals and rehabilitation facilities in the Texas Medical Center in Houston, Texas between October, 2001 and April, 2005 (Schulz, Wasserman, & Ostwald, 2006). Dyads were recruited in an inpatient setting after a confirmed diagnosis of stroke. No data were collected until the stroke survivor was discharged home. Data were collected in the dyad’s home after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation (baseline), at six months, and 12 months after the baseline assessment by a trained nurse assessor. Stroke survivors and spousal caregivers completed the instruments separately. Stroke survivors were interviewed by the nurse assessor who administered the instruments. This allowed for continuous assessment of the stroke survivors’ understanding of the questions. The caregivers completed the instruments in a separate room so that they could not hear the stroke survivors’ responses. Study procedures were started after baseline data were collected and completed before the 12 month data collection.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics such as frequency distributions or means and standard deviations were calculated for demographic variables, stress and mutuality. Comparisons of demographic characteristics between caregivers and stroke survivors were made with paired sample t tests and χ2 tests. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were calculated to determine the association between caregivers’ and stroke survivors’ mutuality and stress at all time points. Repeated measures analysis was used to examine the differences between caregivers and stroke survivors on stress and mutuality from baseline to 12 months using mixed models analysis in SAS PROC MIXED. Independent samples t-test were conducted to test for differences on stress and mutuality between those who did and did not complete the study. An α level of .05 was used to determine statistical significance for all analyses other than correlations which were considered statistically significant at the α level of .01.

The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) for distinguishable dyads (Kenny, 1996; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006) served as the conceptual model for this analysis and was used to determine the effect of the stroke survivors’ and caregivers’ mutuality on their own stress and their partners’ stress. The APIM was used to examine how both members of the dyad affect the outcome. In this study, the actor effect represents how the individual’s mutuality affects his or her own stress while the partner effect represents how the individual’s mutuality affects his or her partner’s stress. The APIM accounts for dyadic interdependence by including both the actor and partner predictor and outcome variables within the same mixed model analysis.

To examine the relation between caregivers’ and stroke survivors’ mutuality and caregivers’ and stroke survivors’ stress over time, a cross-lagged, mixed models analysis was conducted following the procedure outlined by Kenny, Kashy, and Cook (2006). All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.2. Stroke survivors’ and caregivers’ mutuality and stress scores were mean-centered. The dataset was structured such that each unit referred to each person at a point in time. For example, an individual’s record at 6 months had their own scores for 6 month mutuality and stress, their own scores for mutuality and stress at baseline and their partner's scores for mutuality and stress as baseline. There were 954 observations because the dataset contained 159 couples measured at 3 time points (159*2*3). Almost 85% (n=134) of the dyads completed the study. However, missing data were excluded from the analysis and one time point was lost due to lagging because at baseline there was no prior measure of behavior; this resulted in 540 observations available for analysis.

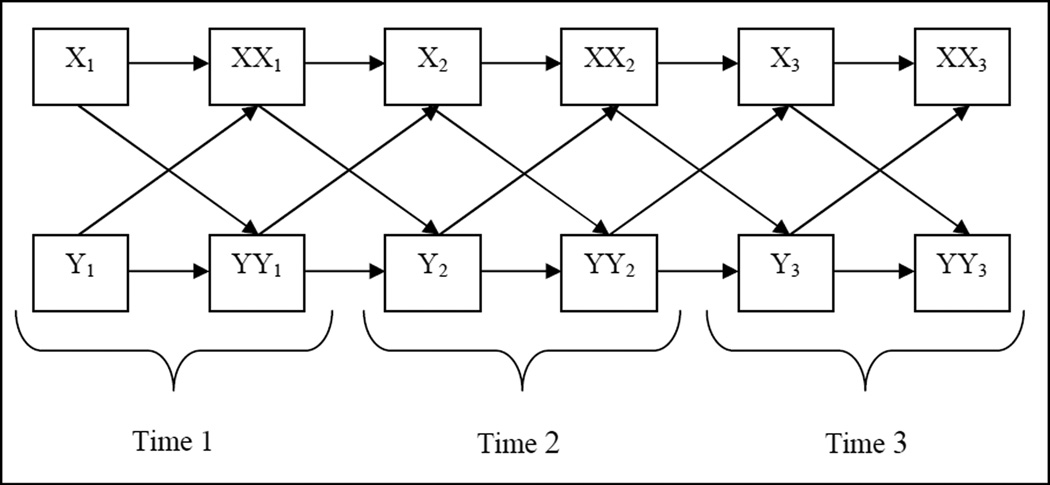

The dataset was organized such that each individual’s outcome (stress) was associated with his/her own lagged predictor (mutuality) scores and his/her partner’s lagged predictor scores over time (Figure 1). Dummy variables were created to allow for data collected at each time point (baseline, 6, and 12 months) and to distinguish between caregiver and stroke survivor (SSorCG). The mixed models included the predictor variables (mutuality) for both actor and partner interactions, the partner outcome (stress) interaction and time. The actor outcome interaction was not included as a separate variable in the model because it was accounted for with the unstructured autoregressive structure (UN@AR(1)) in the repeated statement (Kenny et al., 2006). Interaction terms were used to test differences between the caregiver and stroke survivor.

Figure 1.

Cross-lagged path diagram representing stress and mutuality over time for both members of the dyad*

*Where X= Caregiver Mutuality, Y= Stroke Survivor Mutuality, XX= Caregiver Stress, and YY= Stroke Survivor Stress and 1, 2, 3 = time 1, 2, 3, respectively

The greater number of parameter estimates in a longitudinal, dyadic model, as compared to a cross-sectional model, can result in difficulty in fitting a model. To determine the best model for the data, analyses were run starting with a saturated model including all possible random effects. Models which included unstructured random effects (TYPE=UN) would not converge, thus models with random variance components (TYPE=VC) and compound symmetry (TYPE=CS) were compared. The random variance components model and the compound symmetry model had similar covariance parameters and fixed effects. However, the random variance component structure had the best model fit. When all interaction terms were included in the model along with both the repeated and random effects, the model could not converge. Thus, the interaction terms (actor mutuality*SSorCG, partner mutuality*SSorCG and partner stress*SSorCG) were included in the mixed models analysis as separate random statements. The covariance parameters of the models which included the interaction terms in the random statement(s) were much smaller than the model which did not include the interaction terms in the model. Then, the random effect model was compared separately to the repeated effects model. The fixed effects of two models were found to be very similar, thus it was determined that there was not any unexplained variance from the random effects and the final model contained only fixed effects. Additionally, socioeconomic status and group assignment for the intervention were included in the model as covariates but neither had significant effects and they reduced the model fit. Thus, socioeconomic status and intervention group was removed from the model. The final model contained the fixed effects of the interaction terms for actor and partner mutuality, the interaction term for partner stress and time.

The lagged variables were used as predictors of the subsequent time point. The full model contained an individual’s mutuality at all time points as well as their partner’s stress and mutuality at all time points to predict the individual’s own stress. To simply illustrate how the lag was used in the model the outcome of actor stress further described. Actor stress at 6 months was predicted by partner stress (pstress) at baseline. Likewise, partner stress at 6 months predicted the actor own stress at 12 months. More specifically, the lags were specified as follows:

stress(6 months) = β0 + β1*pstress(baseline) + β2*time

stress(12 months) = β0 + β1*pstress(6 months) + β2*time

Where ‘stress’ is the actor outcome; β0 is the intercept, β1 and β2 are coefficients, ‘pstress’ is the partner’s stress, and ‘time’ represents baseline, 6 or 12 months.

When the model was tested, time was not found to be significant. Because time was not significantly different between lags only one parameter was estimated for both lags (6 months to baseline and 12 months to 6 months). Thus, the results do not include parameters estimates for each time point but only for time overall.

Results

This study contained 159 heterosexual stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers; 84% (n=134) of the dyads completed the 12 month interview. Average age was 66.4 and 62.5 years for the stroke survivors and caregivers, respectively; the majority of stroke survivors were male (74.8%, n=119). The sample was ethnically diverse with slightly more than 40% representative of minority groups, including African American and Non-Hispanic whites. No significant differences were found between stroke survivor and caregiver ethnicity; stroke survivors were significantly older than caregivers t(158)=7.19, p<.0001.

Repeated measures analysis revealed that stroke survivors had significantly higher mutuality scores (F=47.15, p<.0001) and lower stress scores (36.99, p<.0001) than did caregivers (Table 2). Both stroke survivors’ and caregivers’ mutuality decreased over time as did their stress (F=15.56, p< .0001 and F=4.70, p=.01, respectively). Stroke survivors’ mutuality was higher than caregivers’ mutuality at baseline and remained so after 12 months. Caregivers’ perception of their own stress was higher than that of stroke survivors’ across all time points. Additionally, independent samples t-test revealed no significant differences between those who did and did not complete 12 months with regards to caregivers’ and stroke survivors’ mutuality at baseline and stroke survivors’ stress at baseline. Caregivers’ stress at baseline was significantly higher for caregivers who completed 12 months of the study (t(229)=2.38, p=.02).

Table 2.

Caregiver and Stroke Survivor Mutuality and Stress over 12 months

| Caregiver | Stroke Survivor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | |

| Mutuality (Possible Range 0–4) | |||||

| Baseline | 158 | 3.27 | 0.66 | 3.46 | 0.52 |

| 6 months | 137 | 3.08 | 0.70 | 3.30 | 0.63 |

| 12 months | 133 | 3.00 | 0.77 | 3.26 | 0.66 |

| Stress (Possible Range 0–40) | |||||

| Baseline | 158 | 14.00 | 7.25 | 12.27 | 7.46 |

| 6 months | 137 | 13.52 | 7.44 | 10.73 | 7.13 |

| 12 months | 134 | 13.16 | 7.11 | 10.41 | 7.30 |

Caregivers’ mutuality was moderately correlated with their own mutuality over time (rs = 0.659–0.789) and weakly correlated with stroke survivors’ mutuality over time (rs = 0.278–0.464) (Table 3). Stroke survivors’ mutuality was moderately correlated with their own mutuality over time (rs = 0.502–0.638). Caregivers’ mutuality was moderately and inversely correlated with their own stress over time (rs = −0.326- −0.532). Stroke survivors’ mutuality was weakly and inversely correlated with their own stress at the corresponding time point (rs = −0.261- −0.328) but was inversely and weakly correlated with caregiver stress at baseline only (rs = −0.217- −0.272).

Table 3.

Correlations among mutuality and stress in stroke survivor-caregiver dyads

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CG Mutuality baseline | -- | |||||||||||

| 2 | SS Mutuality baseline | 0.464* | -- | ||||||||||

| 3 | CG Mutuality 6 Months | 0.707* | 0.309* | -- | |||||||||

| 4 | SS Mutuality 6 Months | 0.302* | 0.593* | 0.396* | -- | ||||||||

| 5 | CG Mutuality 12 Months | 0.659* | 0.386* | 0.789* | 0.337* | -- | |||||||

| 6 | SS Mutuality 12 Months | 0.292* | 0.502* | 0.278* | 0.638* | 0.379* | -- | ||||||

| 7 | CG Stress baseline | −0.471* | –0.217* | –0.519* | –0.239* | –0.389* | –0.119 | -- | |||||

| 8 | SS Stress baseline | –0.272* | –0.328* | –0.241* | –0.202 | –0.227* | –0.224 | 0.280* | -- | ||||

| 9 | CG Stress 6 Months | –0.326* | –0.134 | –0.494* | –0.218 | –0.391* | –0.067 | 0.576* | 0.160 | -- | |||

| 10 | SS Stress 6 Months | –0.142 | –0.171 | –0.187 | –0.261* | –0.211 | –0.244 | 0.274 | 0.602* | 0.227 | -- | ||

| 11 | CG Stress 12 Months | –0.376* | –0.137 | –0.532* | –0.108 | –0.511* | –0.127 | 0.631* | 0.278 | 0.626* | 0.190 | -- | |

| 12 | SS Stress 12 Months | –0.136 | –0.141 | –0.101 | –0.089 | –0.118 | –0.269* | 0.131 | 0.520* | 0.105 | 0.467* | 0.225* | -- |

p<.01

Caregivers’ mutuality exhibited a statistically significant (β= −3.82, p < .0001) actor effect on their own stress but was not significant on their partners’, the stroke survivors’, stress (β=1.36, p =.08) overall (Table 4 and Figure 2). Stroke survivors’ mutuality exhibited neither an actor effect on their own stress nor a partner effect on the caregivers’ stress overall. Thus, caregivers’ own mutuality was inversely associated with their own stress but not the stroke survivors’ stress while stroke survivors’ mutuality was not significantly associated with either their own or the caregivers’ stress.

Table 4.

The Actor Partner Interdependence Model demonstrating the actor and partner effects of mutuality and stress over time for caregivers and stroke survivors

| Caregiver | Stroke Survivor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Estimate | t value (df) | p-value | Estimate | t value (df) | p-value |

| Mutuality | ||||||

| Actor | –3.82 | 5.54 (259) | <.0001 | 0.20 | 0.24 (265) | 0.812 |

| Partner | 1.36 | 1.76 (269) | 0.080 | –0.58 | 0.72 (264) | 0.472 |

| Stress | ||||||

| Actor* | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Partner | 0.035 | 0.59 (273) | 0.558 | 0.13 | 2.00 (269) | 0.047 |

the actor outcome interaction was not included as a separate variable in the model because it was accounted for with the unstructured autoregressive structure

Figure 2.

The Actor Partner Interdependence Model demonstrating the overall actor and partner effects of mutuality and stress for caregivers and stroke survivors

*=p< .05, **=p<.0001

The actor effects of stress for the caregiver and the stroke survivor was accounted for in the model by the autoregressive structure. The partner effects of stress were included as an interaction term in the model. Caregivers’ stress did not have a significant effect on the stroke survivors’ stress. However, stroke survivors’ stress did have a small partner effect on caregivers’ stress (β=.13, p=.047) (Table 4 and Figure 2).

Discussion

This dyadic analysis of stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers and found perceived stress to improve and mutuality, or the quality of the caregiving relationship, to worsen over the first year post discharge for both caregivers and stroke survivors. However, on average, spousal caregivers had higher perceived stress and lower mutuality than stroke survivors across the year. Additionally, the interdependence of the caregiving relationship examined within the framework of the APIM indicates that the caregiving spouse, and not the stroke survivor, is more directly influenced by the caregiving relationship.

Caregivers’ mutuality was associated with their own stress overall but not the stress of the stroke survivor. Caregivers who had higher mutuality scores, or a more positive view of the caregiving relationship, over the first year post the stroke survivors’ discharge from inpatient rehabilitation had lower perceived stress. This finding is congruent with the literature on caregivers of other patient populations in that higher mutuality scores lessen caregiver strain (Archbold et al., 1990; Tanji et al., 2008) and have been correlated with lower caregiver anxiety and higher caregiver quality of life (Tanji et al., 2008). The results of this study demonstrate the impact that the quality of the caregiver-stroke survivor relationship has on the stress of the caregiver. This is likely due to positive aspects of caregiving relationship between the stroke survivor and his or her spouse ameliorating some of the negative aspects of caregiving (Cohen, Colantonio, & Vernich, 2002) for the caregiving spouse.

This study also found a partner effect for stroke survivors’ stress but not for caregivers’ stress, indicating that the stroke survivors’ stress over time was associated with the caregivers’ stress while the caregivers’ stress over time was not significantly associated with the stress of the stroke survivor. Caregivers appear to be more significantly affected by their partners’ stress than stroke survivors; this is possibly due to the caregiver’s focused attention always being on the needs of the stroke survivor. This highlights the interdependence of the caregiving relationship and the interpersonal nature of stress in the context of caregiving, especially in spousal relationships.

This study has limited generalizability to heterosexual stroke survivor and spousal caregiver dyads over the age of 50 years and English-speaking. All of the dyads in this study spoke English which could represent more acculturation among the ethnic minorities in this study as compared to the larger population. Increased acculturation may influence expectations of gender roles, which could possibly influence both mutuality and stress. A study of Mexican American elders found that among new caregivers, higher acculturation was related to a greater number of depressive symptoms (Han, Kim, & Chiriboga, 2010). Other possible influences on the dyads’ mutuality and stress that were not accounted for in this analysis could include the length of the dyad’s relationship, the amount of social support they receive individually and as a couple, and their co-morbid conditions. Socioeconomic status was not found to have significant effects in this analysis. Another limitation is that the stroke survivors in the study were predominately male; this is likely due to the inclusion criteria that stroke survivors be discharged home with a spouse or committed partner which possibly could have led to more males in this sample since women experience stroke at later ages, possibly after the death of their spouse, and are often cared for by adult children. Furthermore, this study was unable to measure pre-stroke mutuality and stress making it impossible to know if couples with high, or low, mutuality and stress were more likely to agree to participate in the study. Future studies should examine the stroke survivor-caregiver relationship and its effect on stress in non-spousal dyads, such as adult children, other familial or friend caregivers. Additionally, this study had only three time points which contributed to the difficulty of fitting the model. Additional time points might allow for a fully saturated model to be examined.

The present study highlights the interdependence of stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers. While caregiving can be burdensome and stressful, there are benefits of the caregiving relationship as well. A prospective epidemiological study of stroke survivors and their family caregivers found that more than 90% of caregivers reported a greater appreciation for life because of caregiving (Haley et al., 2009). A study of informal caregivers caring for someone in the community found that the benefits of caregiving included companionship, a sense of fulfillment or meaning in life, enjoyment, sense of duty, or enhanced quality of life (Cohen et al., 2002). Although the present study found the caregiver to be more affected by the caregiving relationship than the stroke survivor, previous research has found the positive aspects of the interdependence of the caregiving relationship to be beneficial for the patient as well (Kneeshaw et al., 1999; Ostwald et al., 2009; Tanji et al., 2008). Health professionals should encourage caregivers and stroke survivors to jointly focus on the positive aspects of the caregiving relationship in order to reduce stress, especially in spousal relationships. Moreover, stroke survivors’ stress should be acknowledged and managed as it not only affects stroke survivors but caregivers as well. Stroke survivors and their caregivers should be considered as a dyadic unit, both by health professionals and researchers, as they are interdependent in their relationship. Future interventions of stroke survivors and caregivers should foster dyadic coping in order to reduce couple stress and improve marital quality (Randall & Bodenmann, 2009; Story & Bradbury, 2004).

Finally, interventional research with stroke survivors and caregivers is increasingly including both members of the dyad as there is a vital link between the caregivers’ support and care and the stroke survivors’ physical and mental health. Especially because of the move toward dyadic or family interventions for stroke survivors and caregivers, care should be taken to analyze the resulting data appropriately. Dyads should be analyzed together to take into account their non-independence. Non-independence of dyadic data has important implications for hypothesis testing if the statistical technique assumes independence and can result in either false positives or false negatives (Kenny, 1996; Kashy & Levesque, 2000). Thus, dyadic analysis is more likely to allow us to see the ‘true’ interaction of the caregivers’ and stroke survivors’ mental health in the context of their relationship which will ultimately allow for more robust interventions.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of study sample (n=159 dyads)

| Caregiver | Stroke Survivor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | |

| Age* | 62.5 | 10.45 | 66.4 | 9.14 |

| Socioeconomic Status | 43.44 | 11.62 | 43.44 | 11.62 |

| n | % | n | % | |

| Gender (Male) | 40 | 25.16 | 119 | 74.84 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| African American | 30 | 18.9 | 31 | 19.5 |

| Asian | 6 | 3.8 | 5 | 3.1 |

| Hispanic | 26 | 16.4 | 25 | 15.7 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 92 | 57.9 | 92 | 57.9 |

| Other | 5 | 3.1 | 6 | 3.8 |

t(158)=7.19, p<.0001

Acknowledgements

The parent grant for this study was supported by the National Institues of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research RO1 NR005316 (Sharon K. Ostwald, PI) and the Isla Carrol Turner Friendship Trust. This work was partly supported by the National Research Service Award (T32 HP10031).

References

- Acitelli LK, Badr H. My illness or our illness? Attending to the relationship when one partner is ill. In: Revenson TA, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Greenlick MR, Harvath T. Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Research in Nursing & Health. 1990;13(6):375–384. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonder LX, Langer SL, Pettigrew LC, Garrity TF. The effects of stroke disability on spousal caregivers. Neurorehabilitation. 2007;22(2):85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JH, Stewart BJ, Archbold PG, Inoue I, Jaglin J, Lannon M, et al. Living with a person who has Parkinson’s disease: The spouse's perspective by stage of disease. Parkinson’s study group. Movement Disorders. 1998;13(1):20–28. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadiha LA, Rafferty J, Pickard J. The influence of caregiving stressors, social support, and caregiving appraisal on marital functioning among African American wife caregivers. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy. 2003;29(4):479–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CA, Colantonio A, Vernich L. Positive aspects of caregiving: Rounding out the caregiver experience. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;17(2):184–188. doi: 10.1002/gps.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98(2):310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs UE. Spousal caregiving for stroke survivors. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2007;39(2):112–119. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200704000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper P, Brocklehurst H. The impact of stroke on the well-being of the patient's spouse: An exploratory study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2007;16(2):264–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Norrving B. The International Agenda for Stroke. Presented at the 1st Global Conference on Healthy Lifestyles and Noncommunicable Diseases Control; Moscow, Russia. 2011. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/nmh/events/moscow_ncds_2011/ conference_documents/second_plenary_norrving_fisher_stroke.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg-Warleby G, Moller A, Blomstrand C. Spouses of first-ever stroke patients: Psychological well-being in the first phase after stroke. Stroke. 2001;32(7):1646–1651. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.7.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg-Warleby G, Moller A, Blomstrand C. Life satisfaction in spouses of patients with stroke during the first year after stroke. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2004;36(1):4–11. doi: 10.1080/16501970310015191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TL, King KM. Functional and psychosocial outcomes 1 year after mild stroke. Journal of Stroke & Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2010;19(1):10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood N, Mackenzie A. Informal caring for stroke survivors: Meta-ethnographic review of qualitative literature. Maturitas. 2010;66(3):268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn EA, Kim G, Chiriboga DA. Acculturation and depressive symptoms among Mexican American elders new to the caregiving role: Results from the Hispanic-EPESE. Journal of Aging & Health. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0898264310380454. e-pub (September 17) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley WE, Allen JY, Grant JS, Clay OJ, Perkins M, Roth DL. Problems and benefits reported by stroke family caregivers: Results from a prospective epidemiological study. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2129–2133. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.545269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halm MA, Bakas T. Factors associated with caregiver depressive symptoms, outcomes, and perceived physical health after coronary artery bypass surgery. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2007;22(6):508–515. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000297388.21626.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Haley WE. Family caregiving for patients with stroke: Review and analysis. Stroke. 1999;30:1478–1485. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.7.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead A. Four factor index of social status. 1979 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Deb P. The effect of chronic illness on the psychological health of family members. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2003;6(1):13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashy DA, Levesque MJ. Quantitative methods in close relationships research. In: Hendrick C, Hendrick S, editors. Close relationships: A sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Models of non-independence in dyadic research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1996;13(2):279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WI. Dyadic data analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kneeshaw MF, Considine RM, Jennings J. Mutuality and preparedness of family caregivers for elderly women after bypass surgery. Applied Nursing Research. 1999;12(3):128–135. doi: 10.1016/s0897-1897(99)80034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons KS, Sayer AG, Archbold PG, Hornbrook MC, Stewart BJ. The enduring and contextual effects of physical health and depression on care-dyad mutuality. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007;30(1):84–98. doi: 10.1002/nur.20165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostwald SK, Bernal MP, Cron SG, Godwin KM. Stress experienced by stroke survivors and spousal caregivers during the first year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 2009;16(2):93–104. doi: 10.1310/tsr1602-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall AK, Bodenmann G. The role of stress on close relationships and marital satisfaction. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(2):105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz CH, Wasserman J, Ostwald SK. Recruitment and retention of stroke survivors: The CAReS experience. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics. 2006;25(1):17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Simon C, Kumar S, Kendrick T. Cohort study of informal carers of first-time stroke survivors: Profile of health and social changes in the first year of caregiving. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(3):404–410. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story LB, Bradbury TN. Understanding marriage and stress: Essential questions and challenges. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;23(8):1139–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanji H, Anderson KE, Gruber-Baldini AL, Fishman PS, Reich SG, Weiner WJ, et al. Mutuality of the marital relationship in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2008;23(13):1843–1849. doi: 10.1002/mds.22089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Veenendaal H, Grinspun DR, Adriaanse HP. Educational needs of stroke survivors and their family members, as perceived by themselves and by health professionals. Patient Education and Counseling. 1996;28(3):265–276. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser-Meily A, Post M, Gorter JW, Berlekom SB, Van Den Bos T, Lindeman E. Rehabilitation of stroke patients needs a family-centred approach. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2006;28(24):1557–1561. doi: 10.1080/09638280600648215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A. What bothers caregivers of stroke victims? Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 1994;26:155–161. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199406000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]