Abstract

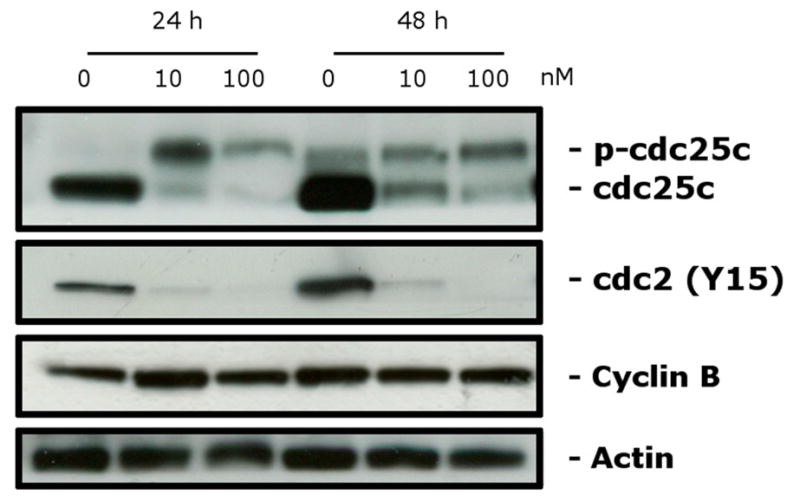

Two new series of inhibitors of tubulin polymerization based on the 2-(alkoxycarbonyl)-3-(3′,4′,5′-trimethoxyanilino)benzo[b]thiophene and thieno[2,3-b]pyridine molecular skeletons were synthesized and evaluated for antiproliferative activity on a panel of cancer cell lines, inhibition of tubulin polymerization, cell cycle effects, and in vivo potency. Antiproliferative activity was strongly dependent on the position of the methyl group on the benzene portion of the benzo[b]thiophene nucleus, with the greatest activity observed when the methyl was located at the C-6 position. Also, in the smaller thieno[2,3-b]pyridine series, the introduction of the methyl group at the C-6 position resulted in improvement of antiproliferative activity to the nanomolar level. The most active compounds (4i and 4n) did not induce cell death in normal human lymphocytes, suggesting that the compounds may be selective against cancer cells. Compound 4i significantly inhibited in vivo the growth of a syngeneic hepatocellular carcinoma in Balb/c mice.

INTRODUCTION

Microtubules are key components of the cytoskeleton of a eukaryotic cell and play an important role in a variety of essential cellular processes, such as mitotic spindle assembly during cell division, formation and maintenance of cell shape, regulation of motility, cell signaling, secretion, and intracellular transport.1,2 Perhaps because of their significant role in cellular functions, microtubules are a proven molecular target for cancer chemotherapeutic agents.3–5 Such compounds interfere with microtubule dynamics, which are particularly important during formation and functioning of the mitotic spindle required for proper chromosomal separation during cell division.6 In the past few decades, a large number of small molecules displaying wide structural diversity and derived from natural sources or obtained by chemical synthesis have been identified and shown to interfere with the tubulin system.7,8 Among the naturally occurring derivatives, combretastatin A-4 (CA-4, 1; Chart 1), isolated from the bark of the South African tree Combretum caffrum, is one of the well-known tubulin-binding molecules affecting microtubule dynamics.9 CA-4 strongly binds to the colchicine site of tubulin and prevents the polymerization of tubulin into microtubules.10 CA-4 shows potent cytotoxicity against a wide variety of human cancer cells, including those that are multi-drug-resistant.11 However, the low water solubility of 1 limited its efficacy in vivo, and a water-soluble disodium phosphate derivative of 1 (named combretastatin A-4 phosphate, CA-4P) has shown promising results in human cancer clinical trials.12

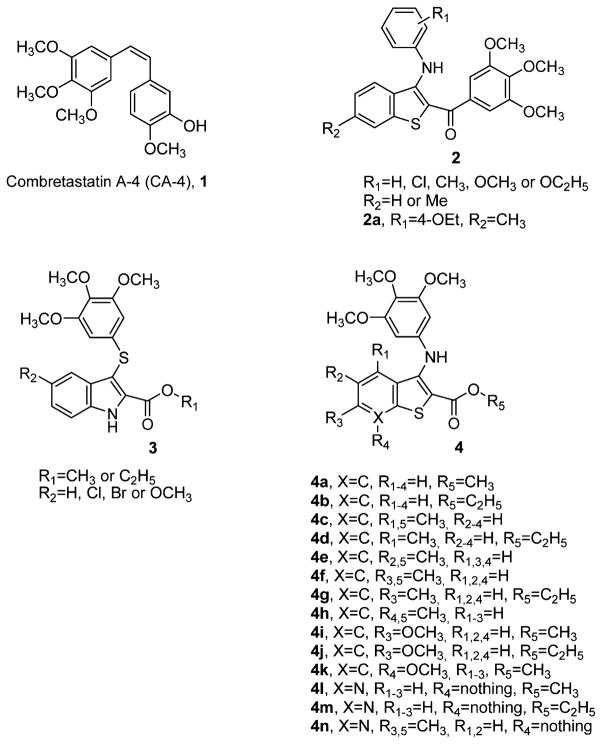

Chart 1.

Chemical Structures of CA-4, 2-(Alkoxycarbonyl)-3-(arylthio)indoles 3, 2-Anilinobenzo[b]thiophenes 2a and 4a–k, and 2-Anilinothieno[2,3-b]pyridines 4l–n

Anticancer therapy based on the discovery and development process of synthetic small molecules as inhibitors of tubulin assembly has interested us and many others in the past few years. In a recent study, we reported the synthesis and biological characterization of a class of molecules with general structure 2 that incorporated the structural motif of the 2-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoyl)-3-anilinobenzo[b]thiophene nucleus.13 The most promising derivative in this collection (2a) was active at micromolar concentrations (IC50 =0.2–1.4 μM) as an antiproliferative agent in a panel of five cancer cell lines and weakly inhibited tubulin assembly, with activity 7-fold reduced relative to that of CA-4 (IC50 = 7.2 μM). Silvestri and co-workers reported a series of 2-(alkoxycarbonyl)-3-[(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)thio]-5-substituted indoles with general structure 3, with excellent activity as inhibitors both of tubulin polymerization and of the growth of MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cells.14–16

Since the 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl substituent was demonstrated to be the essential structural requirement for optimal biological activity in numerous tubulin inhibitors,17,18 in an effort to further improve the activity of compound 2a, we have explored the possibility of replacing the 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoyl and substituted 4-ethoxyanilino moieties at the 2- and 3-positions of the benzo[b]thiophene nucleus of derivative 2a with alkoxycarbonyl and 3,4,5-trimethoxyanilino functions, respectively, in an effort to enhance the activity of 2a analogues. This provided a new series of 2-(methoxy/ethoxycarbonyl)-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyanilino)benzo[b]thiophene derivatives (4a–k), modified with respect to position C-4 to C-7 with methyl or methoxy substitution, corresponding to compounds 4c–h and 4i,k, respectively. In addition, we explored the effect of bioisosteric replacement of the C-7 carbon of derivatives 4a, 4b, and 4f with a basic nitrogen atom to furnish the 2-(alkoxycarbonyl)-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyanilino)thieno[2,3-b]-pyridine derivatives 4l, 4m, and 4n, respectively.

We examined the efficacy of the newly synthesized compounds with tubulin and on a panel of human cancer cell lines, including multi-drug-resistant lines overexpressing the 170 kDa P-glycoprotein drug effux pump. To evaluate further the cytotoxicity of these compounds, we also determined their activity in normal human lymphocytes. Finally, with one of our most active compounds (4i) we obtained preliminary in vivo data with a syngeneic murine tumor model that indicated high activity in tumor growth suppression.

CHEMISTRY

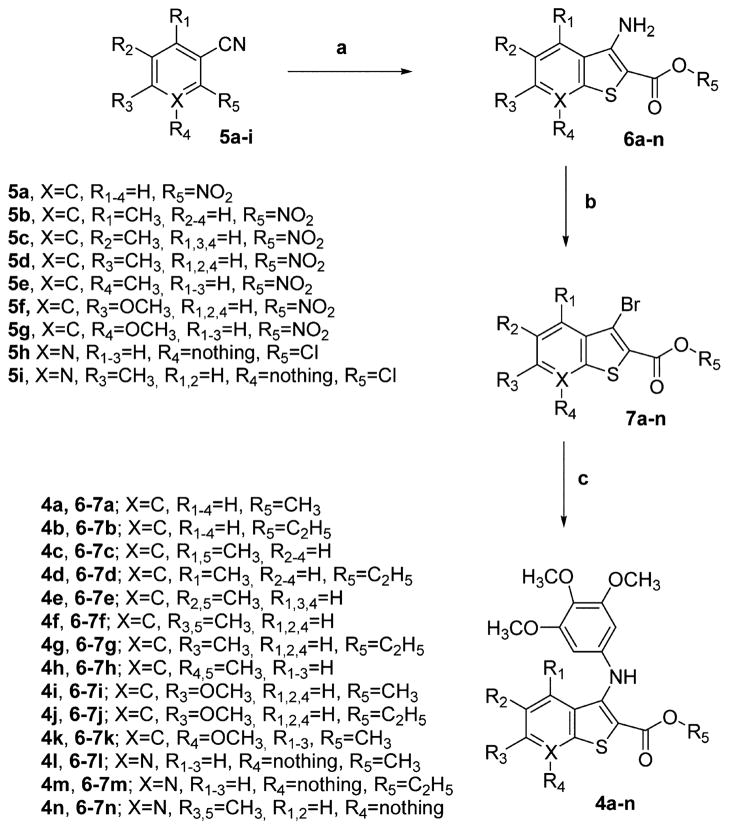

The 2-(alkoxycarbonyl)-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyanilino)benzo[b]-thiophenes 4a–k and the corresponding thieno[2,3-b]pyridines 4l–n were prepared through the three-step synthesis shown in Scheme 1. The condensation of 2-nitrobenzonitriles 5a–g or 2-chloro-3-cyanopyridines 5h,i with methyl/ethyl thioglycolate in DMF with aqueous KOH as the base furnished the 2-(methoxy/ethoxycarbonyl)-3-aminobenzo[b]thiophenes 6a–k and the related thieno[2,3-b]pyridines 6l–n, respectively, in good yields.19 These latter compounds were transformed by substitutive deamination with tBuONO and CuBr2 into the 3-bromobenzo[b]thiophenes 7a–k and 3-bromothieno[2,3-b]-pyridines 7l–n, respectively.20

The novel 2-(alkoxycarbonyl)-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyanilino)-benzo[b]thiophenes 4a–k and the corresponding thieno[2,3-b]pyridines 4l–n were prepared by C–N palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling arylamination conditions of the appropriate 3-bromo derivatives 7a–n with 3,4,5-trimethoxyaniline in the presence of Pd(OAc)2, BINAP as the ligand, and CsCO3 as the base in toluene.21

BIOLOGICAL RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In Vitro Antiproliferative Activities

The 2-(methoxy/ ethoxycarbonyl)-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyanilino)benzo[b]-thiophenes 4a–k and the related thieno[2,3-b]pyridines 4l–n were evaluated for their antiproliferative activity against a panel of seven human cancer cell lines and compared with the reference compound 1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

In Vitro Cell Growth Inhibitory Effects of Compounds 4a–n and CA-4 (1)

| compd | IC50a (nM)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa | A549 | HL-60 | Jurkat | SEM | MCF-7 | HT-29 | |

| 4a | 427 ± 51 | 2850 ± 235 | 1536 ± 378 | 490 ± 53 | 179 ± 41 | 795 ± 42 | 299 ± 31 |

| 4b | 3095 ± 200 | 8531 ± 2088 | 5491 ± 379 | 3023 ± 423 | 1901 ± 215 | 6391 ± 659 | 1610 ± 86 |

| 4c | 1301 ± 248 | 4578 ± 588 | 3385 ± 342 | 6710 ± 1532 | 2505 ± 332 | 8192 ± 1135 | 1024 ± 197 |

| 4d | 2520 ± 184 | 6252 ± 1555 | 7385 ± 1197 | 5666 ± 950 | 1933 ± 234 | 4153 ± 404 | 3614 ± 254 |

| 4e | 398 ± 75 | 2806 ± 452 | 4717 ± 460 | 727 ± 151 | 185 ± 27 | 540 ± 86 | 299 ± 46 |

| 4f | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 10.8 ± 4.5 | 20.5 ± 9.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 0.94 |

| 4g | 0.38 ± 0.04 | 7.2 ± 3.1 | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 9.0 ± 4.3 | 6.0 ± 3.0 |

| 4h | 1730 ± 143 | 3931 ± 401 | 4266 ± 369 | 1630 ± 704 | 1628 ± 157 | 4548 ± 371 | 552 ± 148 |

| 4i | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 8.5 ± 1.9 | 0.4 ± 0.10 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 10.3 ± 5.6 | 0.7 ± 0.08 | 0.9 ± 0.04 |

| 4j | 0.56 ± 0.06 | 8.9 ± 2.8 | 31.6 ± 8.4 | 3.3 ± 1.3 | 10.2 ± 4.6 | 5.6 ± 1.5 | 10.2 ± 3.2 |

| 4k | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 33.0 ± 10.1 | 25.6 ± 8.0 | 56.5 ± 15.2 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 95 ± 33.2 | 14.9 ± 3.9 |

| 4l | 342 ± 42.2 | 3850 ± 316 | 2915 ± 882 | 1113 ± 176 | 348 ± 63 | 2644 ± 423 | 542 ± 130 |

| 4m | 2102 ± 737 | 7157 ± 969 | 6097 ± 823 | 8450 ± 1520 | 1850 ± 248 | 5275 ± 736 | 2259 ± 475 |

| 4n | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 16.2 ± 4.4 | 0.4 ± 0.08 | 0.6 ± 0.02 | 0.5 ± 0.01 | 0.53 ± 0.09 | 0.35 ± 0.15 |

| CA-4 | 4 ± 1 | 180 ± 50 | 1 ± 0.2 | 5 ± 0.6 | 5 ± 0.1 | 370 ± 100 | 3100 ± 100 |

IC50 = compound concentration required to inhibit tumor cell proliferation by 50%. Data are presented as the mean ± SE from the dose–response curves of at least three independent experiments.

Compounds with a methyl (4f and 4g) or a methoxy (4i and 4j) substituent at the C-6 position of the 2-(methoxy/ethoxycarbonyl)-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyanilino)benzo[b]thiophene system, along with the 2-(methoxycarbonyl)-3-(3,4,5-trime-thoxyanilino)-6-methylthieno[2,3-b]pyridine (4n), exhibited the greatest antiproliferative activity among the tested compounds, with IC50 values of 0.31–20, 0.38–9.0, 0.28–10, 0.56–32, and 0.18–16 nM, respectively, showing more activity against HeLa cells as compared with the other cell lines. Derivative 4n was the only compound more potent than the reference compound 1 (from 1 to 3 orders of magnitude) against all cancer cell lines.

The two C-4/C-7-unsubstituted benzo[b]thiophene derivatives 4a and 4b proved moderately active, with 4a being about 3–10-fold more active than 4b (IC50 = 0.18–2.8 and 1.9–8.5 μM, respectively). The results presented in Table 1 show that the location of the methyl group on the benzene portion of the benzo[b]thiophene nucleus plays a critical role in inhibition of cell growth, with the greatest activity observed when the methyl is at the C-6 position of the benzo[b]thiophene nucleus (compounds 4f and 4g) (IC50 = 0.31–11 nM). Shifting the methyl group to the C-5 position (4e) resulted in only modest activity (IC50 = 0.18–2.8 μM), while moving it to either the C-4 or C-7 position further decreased activity (derivatives 4c, 4d, and 4h, IC50 as high as 8.2 μM).

Comparing the two C-6 methyl analogues 4f and 4g, the activity of methoxycarbonyl compound 4f was quite similar to that of the ethoxycarbonyl homologue 4g against HeLa, A549, and Jurkat cells, while there were greater differences from the other cell lines. 4f was 2–7-fold more active than 4g against SEM, HT-29, and MCF-7 cells, while 4g was 5-fold more potent than 4f against HL-60 cells. With the exception of HL-60 cells, both these molecules were more potent than the positive control 1.

As compounds 4i and 4j demonstrate, the C-6 methyl group can be replaced with a methoxy group without substantial loss of activity against HeLa, A549, MCF-7, and HT-29 cells. As growth inhibitors, 4i and 4j were equipotent against A549 and SEM cells, while the methoxycarbonyl derivative 4i was from 2-to 10-fold more potent than its ethoxycarbonyl counterpart 4j against the other five cancer cell lines. Although compound 4i was 2-fold less potent than 1 against the SEM cells, it was 2–3000-fold more active than 1 against the other six cell lines.

Replacing the C-7 methyl group of compound 4h with a methoxy moiety (4k) increased antiproliferative activity from 1 to 3 orders of magnitude (IC50 = 552–4548 and 2.3–95 nM for 4h and 4k, respectively), indicating that methyl and methoxy groups are not bioequivalent at the C-7 position of the benzo[b]thiophene nucleus.

A comparison between the methoxycarbonyl derivatives 4i and 4k demonstrated that the C-6 methoxy derivative 4i was generally 1–2 orders of magnitude superior as an inhibitor of cancer cell growth relative to the C-7 methoxy analogue 4k. The only exception was the SEM cells, which were somewhat more sensitive to 4k.

Comparing the two unsubstituted 2-(alkoxycarbonyl)-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyanilino)thieno[2,3-b]pyridine derivatives 4l and 4m, the methoxycarbonyl group on the C-2 position of thieno[2,3-b]pyridine analogue 4l resulted in better inhibitory activity than the ethoxycarbonyl moiety of 4m. As previously observed for the benzo[b]thiophene series, for the thieno[2,3-b]pyridine derivatives, the introduction of a methyl group at the C-6 position (compound 4n) resulted in a dramatic reduction in IC50 values to nanomolar and subnanomolar levels. Comparing 4n with the benzo[b]thiophene analogue 4f, replacement of the benzene with the bioisosteric pyridine ring produced a 2–50-fold increase in activity against HeLa, HL-60, MCF-7, and HT-29 cells, while 4f and 4n were equipotent against Jurkat and SEM cells. Reduction in potency was observed only against A549 cells.

Evaluation of Cytotoxicity in Human Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes

To obtain more insight into the cytotoxic potential of these new compounds for normal human cells, two of the most active compounds (4i and 4n) were assayed in vitro against peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) from healthy donors (Table 2). Compounds 4i and 4n were ineffective in resting lymphocytes having an IC50 > 10 μM and proved cytotoxic only for PHA-stimulated PBLs, but at higher concentrations (2000–3000-fold) than those active against the lymphoblastic cell lines Jurkat and CEM. These data thus suggest that these compounds may have cancer cell selective killing properties.

Table 2.

Cytotoxicity of 4i and 4n for Human PBLs

IC50 = compound concentration required to reduce cell growth inhibition by 50%. Values are the mean ± SEM for three separate experiments.

PBLs not stimulated with PHA.

PBLs stimulated with PHA.

Effect of Compounds 4i and 4n on Multi-Drug-Resistant Cells

Drug resistance is an important therapeutic problem caused by the emergence of tumor cells possessing different mechanisms that confer resistance against a variety of anticancer drugs.22,23 The more common mechanisms are those related to the overexpression of a cellular membrane protein called P-glycoprotein (P-gp) that mediates the effux of various structurally unrelated drugs.22,23 In this context, we evaluated the sensitivity of 4i and 4n on two multi-drug-resistant cell lines, one derived from lymphoblastic leukemia (CEMVbl-100), the other derived from colon carcinoma (LovoDoxo). Both these lines express high levels of P-gp.24,25 As shown in Table 3, the two compounds were equally potent toward parental cells and cells resistant to vinblastine or doxorubicin, showing a resistance index (RI, the ratio between IC50 values of resistant cells and sensitive cells) of about 1.

Table 3.

In Vitro Cell Growth Inhibitory Effects of Compounds 4i and 4n on Drug-Resistant Cell Lines

| compd | IC50a (nM)

|

resistance ratiob | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LoVo | LoVoDoxo | ||

| 4i | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 1.3 |

| 4n | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.3 |

| doxorubicin | 95.6 ± 43.2 | 11296 ± 356 | 118 |

|

| |||

| CEM | CEM Vbl100 | resistance ratiob | |

|

| |||

| 4i | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.4 |

| 4n | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 1.5 |

| vinblastine | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 211 ± 82 | 105 |

|

| |||

| A549 | A549-T12 | resistance ratiob | |

|

| |||

| 4l | 8.5 ± 1.9 | 12.6 ± 2.9 | 1.5 |

| 4m | 16.2 ± 4.4 | 19.5 ± 2.3 | 1.2 |

| paclitaxel | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 92.3 ± 26.8 | 26 |

IC50 = compound concentration required to inhibit tumor cell proliferation by 50%. Data are presented as the mean ± SE from the dose–response curves of at least three independent experiments.

The values express the ratio between IC50 determined in resistant and nonresistant cell lines.

Resistance to microtubule inhibitors may also be mediated by changes in the levels of expression of different β-tubulin isotypes and by tubulin gene mutations.26–28 Although a high rate of tubulin mutations have not been found in patients with different forms of tumors, this kind of mutation, when present, can result in modified tubulin with impaired polymerization properties and dynamics that probably lead to alterations in drug efficacy.

A-549-T12 is a cell line with an α -tubulin mutation with increased resistance to paclitaxel.29 Compounds 4i and 4n had greater relative activity than paclitaxel in this cell line (Table 3), having an RI similar to that found in wild-type cells, suggesting that, in addition to classical resistance mediated by P-gp, these compounds might be useful in the treatment of tumors in which drug resistance involves tubulin mutations.

Inhibition of Tubulin Polymerization and Colchicine Binding

To investigate whether the antiproliferative activities of compounds 4f,g, 4i–k, and 4n derived from an interaction with tubulin, these agents were evaluated for their inhibition of tubulin polymerization and for effects on the binding of [3H]colchicine to tubulin (Table 4).30–32 For comparison, CA-4 was examined in contemporaneous experiments. All tested compounds strongly inhibited tubulin assembly, and derivatives 4i, 4j, 4k, and 4n, with IC50 values of 0.88, 0.81, 0.76, and 0.70 μM, respectively, exhibited antitubulin activity greater than that of CA-4 (IC50 = 1.1 μM), while 4f and 4g had IC50 values of 1.2 and 1.1 μM, respectively, essentially equivalent to that of CA-4. Thus, the order of inhibitory effects on tubulin polymerization was 4n > 4k > 4j > 4i > CA-4 = 4g > 4f. With the exception of 4k, there was an excellent correlation between inhibition of tubulin polymerization and antiproliferative activity.

Table 4.

Inhibition of Tubulin Polymerization and Colchicine Binding by Compounds 4f,g, 4i–k, and 4n and CA-4

| compd | tubulin assemblya IC50 (μM) ± SD | colchicine bindingb (%)± SD

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 μM drug | 1 μM drug | ||

| 4f | 1.2 ± 0.05 | 95 ± 0.6 | 71 ± 2 |

| 4g | 1.1 ± 0.09 | 89 ± 0.2 | 58 ± 0.5 |

| 4i | 0.88 ± 0.1 | 98 ± 1 | 85 ± 2 |

| 4j | 0.81 ± 0.06 | 94 ± 1 | 77 ± 0.6 |

| 4k | 0.76 ± 0.02 | 76 ± 2 | 54 ± 1 |

| 4n | 0.70 ± 0.01 | 95 ± 0.9 | 78 ± 2 |

| CA-4 (1) | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 99 ± 0.1 | 90 ± 1 |

Inhibition of tubulin polymerization. Tubulin was at 10 μM.

Inhibition of [3H]colchicine binding. Tubulin and colchicine were at 1 and 5 μM, respectively, and the tested compound was at the indicated concentration.

In the colchicine studies, compounds 4f,g, 4i–k, and 4n potently inhibited the binding of [3H]colchicine to tubulin, since 76–98% inhibition occurred with these agents and colchicine both at 5 μM. Compound 4i was the most active inhibitor of the binding reaction, since 85% and 98% inhibition occurred with this agent at 1 and 5 μM, respectively. Compound 4i was as active as CA-4 when both compounds were tested at 5 μM, while at 1 μM 4i was slightly less potent than CA-4, which in these experiments inhibited colchicine binding by 99% and 90% at 5 and 1 μM, respectively.

While this group of compounds were all highly potent in the biological assays (inhibition of cell growth, tubulin assembly, and colchicine binding), correlation between the last two assay types was imperfect. Thus, while compound 4n was the best inhibitor of tubulin assembly, its effect on colchicine binding was matched by that of derivative 4f, which was 1.5-fold less active as an assembly inhibitor. In general, in these experiments inhibition of tubulin assembly correlated more closely with antiproliferative activity than did inhibition of [3H]colchicine binding.

The results are consistent with the conclusion that the antiproliferative activity of these compounds derives from an interaction with the colchicine site of tubulin and interference with microtubule assembly.

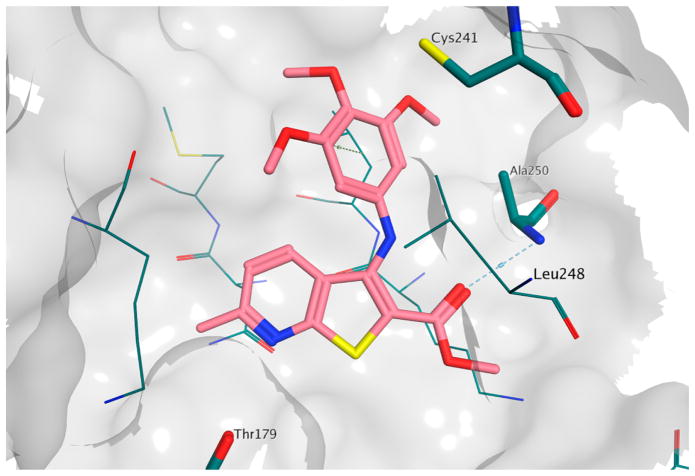

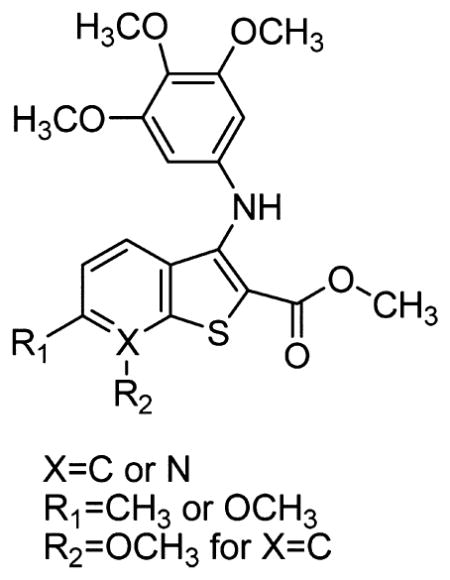

Molecular Modeling

To investigate the possible binding mode for this series of compounds, we performed a series of molecular docking simulations on the colchicine site of tubulin.33 The results obtained are similar to those reported for the (arylthio)indole family (3),34 with the trimethoxyphenyl ring in proximity of βCys241 and the heterocycle sitting deep in the hydrophobic pocket (Figure 1). However, the formation of an intramolecular hydrogen bond between the amino group and the carbonyl group in this series of compounds forces the ester moiety into a different orientation compared with that of 3, and this allows the formation of a hydrogen bond between the ester itself and βAla250. Interestingly, this binding pose was observed for all the compounds in the reported series (see the Supporting Information, Figure 1s), although, in the case of 4h, the methyl substituent induced a slight, yet significant, change in the pose orientation that caused the loss of the hydrogen bond described above (Figure 2). It should be noted that the methoxy-substituted analogue 4k was able to maintain the hydrogen bond between βAla250 and the ester group, suggesting that the binding pocket has very specific steric properties in this region, and this in turn suggests a structural justification for the loss of activity observed for 4h.

Figure 1.

Binding model of 4n in the colchicine site of tubulin. The hydrogen bond with βAla250 is indicated by a dashed line.

Figure 2.

Binding poses of 4h (in gray) and 4k (in magenta) in the colchicine site of tubulin. The hydrogen bond between 4k and βAla250 is indicated by a dashed line.

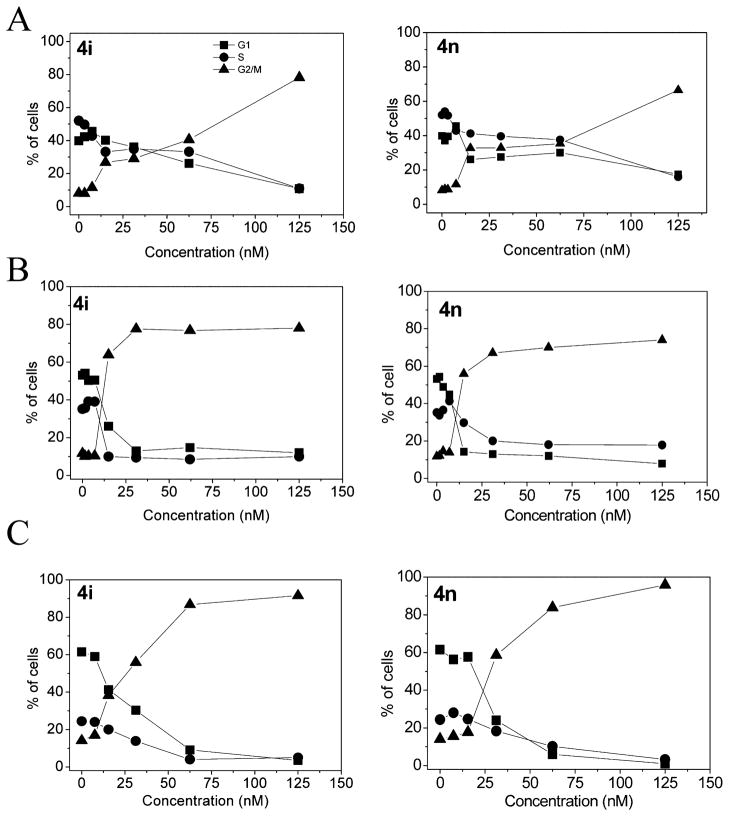

Analysis of Cell Cycle Effects

The effects of 24 h treatment with different concentrations of 4i and 4n on cell cycle progression in Jurkat, HT-29, and HeLa cells were determined by flow cytometry (Figure 3). The two compounds caused a significant G2/M arrest in a concentration-dependent manner in the cell lines tested, with a rise in G2/M cells occurring at a concentration as low as 20 nM, while at higher concentrations more than 80% of the cells were arrested in G2/ M. The cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase was accompanied by a commensurate reduction in cells in the other phases of the cell cycle.

Figure 3.

Percentage of cells in each phase of the cell cycle in Jurkat (A), HT29 (B), and HeLa (C) cells treated with the indicated compounds at the indicated concentrations for 24 h. Cells were fixed and labeled with PI and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in the Experimental Section.

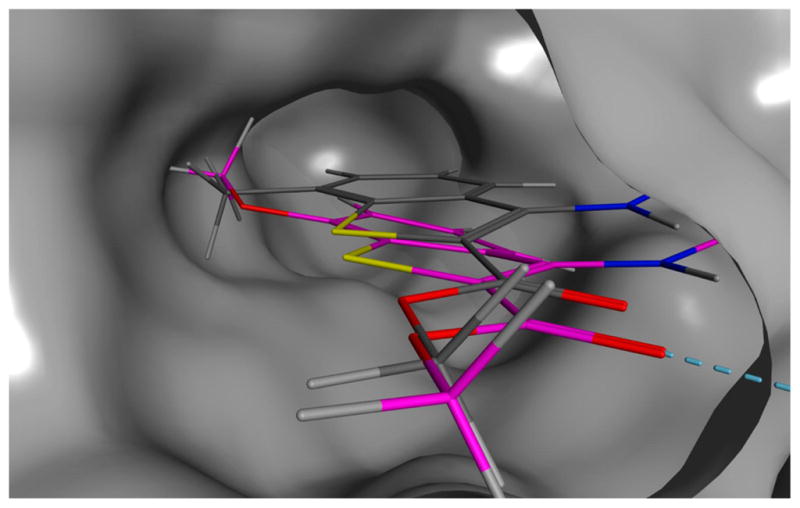

We next studied the association between 4i-induced G2/M arrest and alterations in expression of proteins that regulate cell division. The cdc2/cyclin B complex controls both entry into and exit from mitosis. Phosphorylation of cdc2 on Tyr15 and phosphorylation of cdc25c phosphatase on Ser216 negatively regulate the activation of the cdc2/cyclin B complex.

Thus, dephosphorylation of these proteins is needed to activate the cdc2/cyclin B complex. Cdc25c is a major phosphatase that dephosphorylates the site on cdc2 and autodephosphorylates itself. Phosphorylation of cdc25C directly stimulates both its phosphatase and its autophosphatase activities, a condition necessary to activate cdc2/cyclin B on entry of cells into mitosis.35–37 As shown in Figure 4 in HeLa cells, treatment with 4i at either 10 or 100 nM caused no significant variations in cyclin B expression after either a 24 or 48 h treatment. In contrast, slower migrating forms of phosphatase cdc25c appeared at 24 and 48 h, indicating changes in the phosphorylation state of this protein. We also observed a dramatic decrease in the expression of the phosphorylated form of cdc2 (Tyr15). These data, along with the fact that over 80% of the cells accumulated in the G2/M phase, suggest that 4i-induced G2/M arrest is not due to defects in G2/M regulatory proteins but, rather, is closely linked with acceleration of entry into mitosis.

Figure 4.

Effect of 4i on G2/M regulatory proteins. HeLa cells were treated for 24 or 48 h with the indicated concentration of 4i. The cells were harvested and lysed for the detection of cyclin B, p-cdc2Y15, and cdc25C expression by Western blot analysis. To confirm equal protein loading, each membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody.

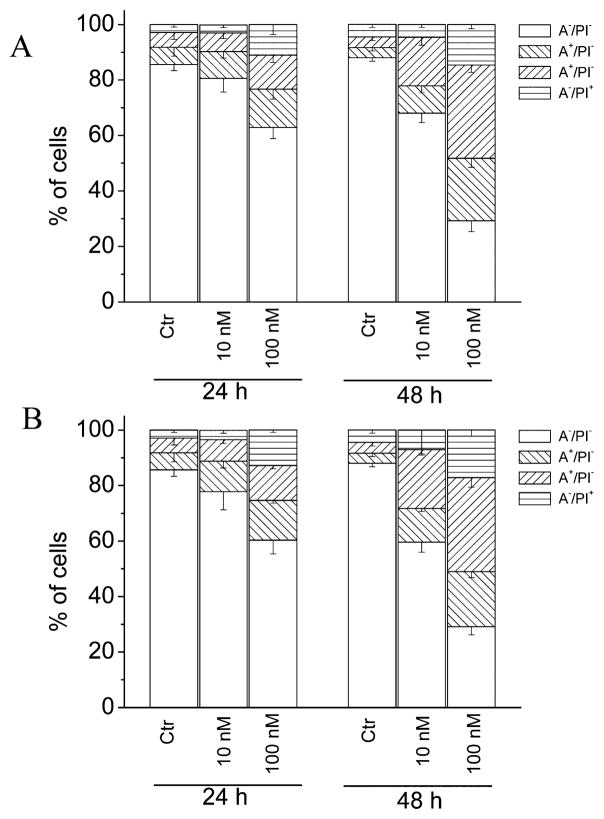

Compounds 4i and 4n Induce Apoptosis

To characterize the mode of cell death induced by 4i and 4n, a biparametric cytofluorimetric analysis was performed using PI, which stains DNA and enters only dead cells, and fluorescent immunolabeling of the protein annexin-V, which binds to PS in a highly selective manner.38 Dual staining for annexin-V and with PI permits discrimination among live cells (annexin-V−/PI−), early apoptotic cells (annexin-V+/PI−), late apoptotic cells (annexin-V+/PI+), and necrotic cells (annexin-V−/PI+). As depicted in Figure 5, HeLa cells treated with 4i or 4n showed an accumulation of annexin-V-positive cells in comparison with the control, in a concentration- and time-dependent manner.

Figure 5.

Flow cytometric analysis of apoptotic cells after treatment of HeLa cells with 4i (A) or 4n (B) at the indicated concentrations after incubation for 24 or 48 h. The cells were harvested and labeled with annexin-V–FITC and PI and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

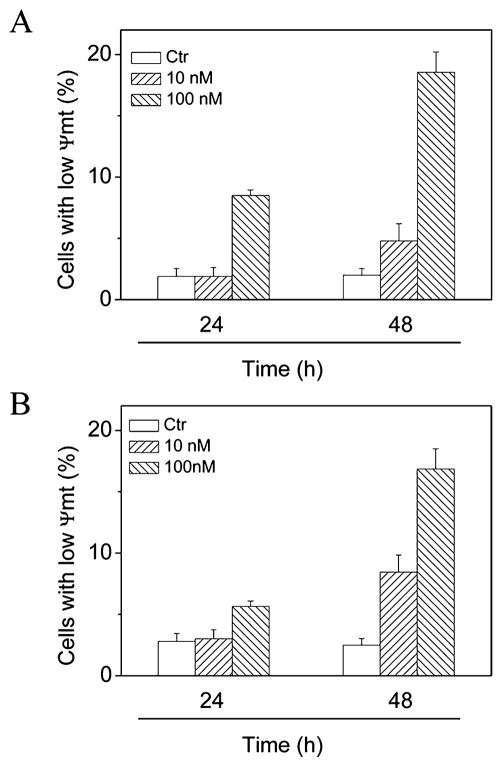

Compounds 4i and 4n Induce Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Mitochondria play an essential role in the propagation of apoptosis.39 It is well established that, at an early stage, apoptotic stimuli alter the mitochondrial trans-membrane potential (Δψmt). Δψmt was monitored by the fluorescence of the dye 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl-benzimidazolcarbocyanine (JC-1). As shown in Figure 6, both 4i and 4n induced a time- and concentration-dependent increase in the proportion of cells with depolarized mitochondria.

Figure 6.

Assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψmt) after treatment of HeLa cells with compound 4i (A) or 4n (B). Cells were treated with the indicated concentration of compound for 24 or 48 h and then stained with the fluorescent probe JC-1. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM for three independent experiments.

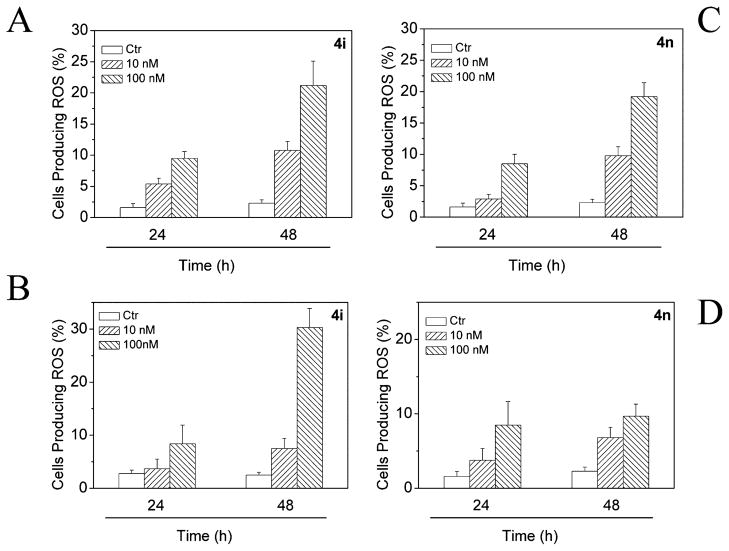

Mitochondrial membrane depolarization is associated with mitochondrial production of ROS.40 Therefore, we investigated whether ROS production increased after treatment with 4i or 4n. We analyzed the production of ROS by flow cytometry utilizing two fluorescence indicators: hydroxyethydine (HE) or 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2-DCFDA).41

The results presented in Figure 7 show that both 4i and 4n induced the production of significant amounts of ROS in comparison with control cells, which agrees with the previously described dissipation of Δψmt. Altogether, these results indicate that these compounds induced apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway. In this context, it is interesting to note that many other antimitotic compounds induce apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway.13,42

Figure 7.

Mitochondrial production of ROS in HeLa cells following treatment with compound 4i (A, B) or compound 4n (C, D). After 24 or 48 h incubations, cells were stained with H2-DCFDA (A, C) or HE (B, D) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

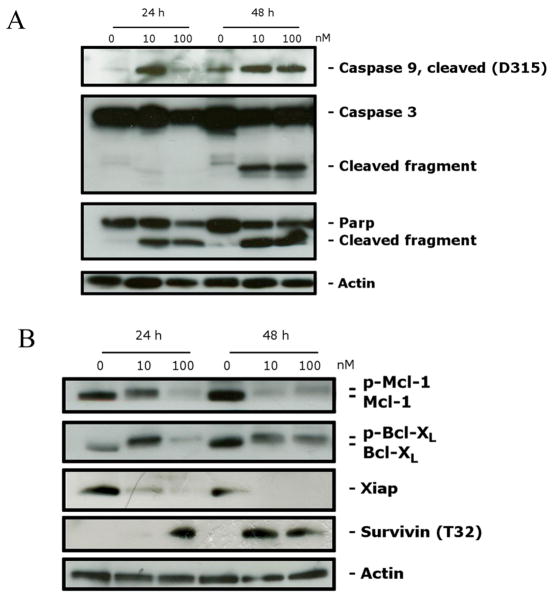

Compound 4i Induces Caspase Activation

The activation of caspases plays a central role in the process of apoptotic cell death.43 Synthesized as proenzymes, caspases are themselves activated by specific proteolytic cleavage reactions. Caspases-2, -8, -9, and -10 are termed initiator caspases and are usually the first to be activated in the apoptotic process. Following their activation, they in turn activate effector caspases, in particular caspase-3.44 As shown in Figure 8A, compound 4i induced proteolytic cleavage of caspase-9 and caspase-3, in good agreement with the mitochondrial depolarization described above. The DNA repair enzyme poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) is cleaved by caspase-3 from its full-length 116 kDa form to an inactive 85 kDa form. We also observed that PARP cleavage was detectable at 24 h and at a low concentration (10 nM) of 4i. Altogether, these results showed that 4i-induced apoptosis is caspase-dependent, in addition to utilizing the intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway.

Figure 8.

(A) Western blot analysis of caspase-3, cleaved caspase-9, and PARP after treatment of HeLa cells with 4i at the indicated concentrations and for the indicated times. (B) Western blot analysis of Bcl-XL, survivinThr32, Mcl-1, and XIAP after treatment of HeLa cells with 4i at the indicated concentrations and for the indicated times. To confirm equal protein loading, each membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody.

Effect of 4i on Proapoptotic Proteins and IAP Expression

There is increasing evidence that regulation of the Bcl-2 family of proteins shares the signaling pathways induced by antimicrotubule compounds.45 Several proapoptotic family proteins (e.g., Bax, Bid, Bim, and Bak) promote the release of cytochrome c, whereas antiapoptotic members (Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Mcl-1) are capable of antagonizing the proapoptotic proteins and preventing the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential. Antimitotic drugs can induce the phosphorylation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL.46 In agreement with these observations, we found that Bcl-XL was phosphorylated after treatment with 4i, as demonstrated by a band shift (Figure 8B), and these results are in agreement with previous studies.46 Mcl-1 is an antiapoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family, and recently it has been reported that sensitivity to antimitotic drugs is regulated by Mcl-1 levels.47 As shown in Figure 8B, as with Bcl-XL, a slower migrating form of the Mcl-1 band appeared, indicative of Mcl-1 phosphorylation. This change was observed after 24 h treatments at both 10 and 100 nM 4i, while the unmodified protein disappeared. In addition, a substantial reduction in the phosphorylated form occurred by 48 h with 10 nM 4i. With 100 nM 4i, there was much less phosphorylated Mcl-1 at 24 h than with 10 nM 4i, suggesting that peak formation of phosphorylated Mcl-1 occurred even earlier. These results are in agreement with recent studies that underlined the importance of Mcl-1 phosphorylation and its subsequent degradation in response to antimitotic agents and that this event potentiates cell death.48,49

Xiap and survivin are members of the IAP family (inhibitors of apoptosis protein). In general, the IAPs function through direct interactions to inhibit the activity of several caspases, including caspase-3, caspase-7, and caspase-9, and they thereby inhibit the processing and activation of these enzymes.50 Our results (Figure 8B) showed that expression of Xiap was almost eliminated after a 24 h treatment with 4i, even at a concentration of 10 nM.

Of note, survivin was phosphorylated on Thr32 upon treatment with 4i at both 24 and 48 h. This effect is consistent with cell cycle arrest in mitosis and is shared by various antimitotic drugs.51,52

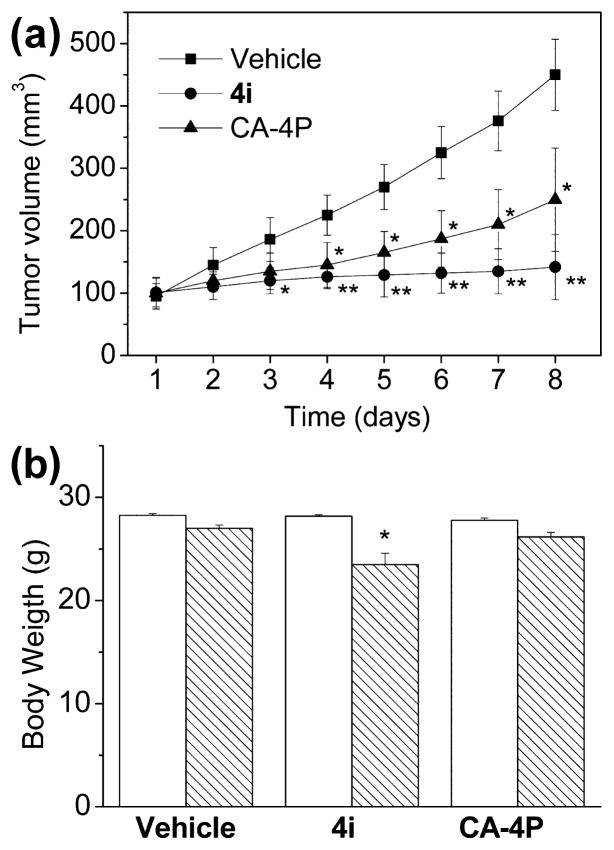

In Vivo Antitumor Activity of Compound 4i

To evaluate the in vivo antitumor activity of 4i, a syngeneic hepatocellular carcinoma model in mice was used.53 It was established by subcutaneous injection of BNL 1ME A.7R.1 cells into the backs of Balb/c mice. In preliminary experiments in vitro, we determined that compound 4i showed remarkable cytotoxic activity (IC50 = 2.1 nM) against BNL 1ME A.7R.1 cells. Once the BNL 1ME A.7R.1 allografts reached a size of ~100 mm3, fifteen mice were randomly assigned to one of the three groups. In two of the groups, compound 4i and the reference compound CA-4P, both dissolved in a 0.9% NaCl solution containing 5% polyethylene glycol 400 and 0.5% Tween 80, were injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 5 mg/kg, while the third group was used as a control. Both drugs, as well as the vehicle control, were administered daily for seven days. As shown in Figure 9A, compound 4i immediately caused a significant reduction in tumor growth, and this reached a 68.5% reduction by the end of the observation period as compared with administration of vehicle only. The reduction in tumor growth was statistically significant as early as the third day after the beginning of the treatment, suggesting a rapid, effective delivery of the compound to the tumor mass. The effect on tumor volume reduction by 4i was greater than that obtained with CA-4P, which caused a 44.5% reduction in volume at the end of the treatment. During the treatment period, only a small decrease in body weight occurred in the 4i-treated animals (Figure 9B).

Figure 9.

Inhibition of mouse allograft growth in vivo by compound 4i. Male mice were injected subcutaneously at their dorsal region with 107 BNL 1MEA.7R.1 cells, a syngeneic hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Tumor-bearing mice were administered the vehicle as a control or 5 mg/kg of 4i or CA-4P as a reference compound. Injections were given intraperitoneally daily starting on day 1. The figure shows the average measured tumor volumes (A) and body weights of the mice (B) recorded at the end of the treatments. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of tumor volume and body weight at each time point for five animals per group. Key: *, p < 0.05 vs control; **, p < 0.01 vs control.

CONCLUSIONS

Manipulation of the scaffold of compounds with general structures 2 and 3 led to the successful identification of a new series of inhibitors of tubulin assembly, characterized by an ester and a 3,4,5-trimethoxyaniline function at the 2- and 3-positions, respectively, of the benzo[b]thiophene nucleus. Structure–activity relationship studies revealed that a methyl or methoxy substitution at the C-6 position of the benzo[b]-thiophene skeleton results in the greatest inhibitory effects on cancer cell growth (compounds 4f, 4g, 4i, and 4j). We also observed effects at the C-7 position, where the substitution of a methyl with a methoxy group (4f and 4k, respectively) caused a substantial increase in activity. Comparing compounds 4i and 4k demonstrated that moving the methoxy group from the C-6 to the C-7 position caused a 4–130-fold reduction in antiproliferative activity.

The substitution with a nitrogen of the carbon at the C-6 position of compound 4f, to furnish 4n, resulted in improvement of the IC50 values, with 2–50-fold elevation in potency against four cancer cell lines. Compound 4n was one of the most active antiproliferative agents and the most effective inhibitor of tubulin polymerization among the newly synthesized compounds. Its antitubulin activity closely paralleled that of reference compound 1, and 4n was more active than 1 as an inhibitor of cancer cell growth.

Moreover, 4i and 4n had very low toxicity toward both quiescent and mitogen-stimulated cultures of primary lymphocytes, suggesting that these compounds may have selectivity against cancer cells. Further experiments in other non cancer cell models are needed to confirm this finding. In additional experiments, we found that these compounds overcame drug resistance, since 4i and 4n were not substrates of P-gp and were active in a cell line with a mutant α-tubulin. Both 4i and 4n were potent inducers of apoptosis in the HeLa cell line. These compounds were able to induce Bcl-XL phosphorylation, which is associated with the loss of antiapoptotic functions. Another prosurvival protein, Mcl-1, was found to be phosphorylated in response to cell treatment with 4i. Our results confirm that the induction of apoptosis by 4i and 4n is associated with dissipation of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential and activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3, which is coupled with terminal events of apoptosis, including PARP cleavage. The antitumor efficacy of 4i was demonstrated in a syngeneic tumor model in mice, in which we observed a significant inhibition of tumor growth at a low dose of 4i, which had minimal toxicity. In conclusion, our results demonstrated that 4i is a very promising new tubulin binding agent and is worthy of further evaluation as a potential chemotherapeutic agent.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemistry

Materials and Methods

1H NMR data were determined in CDCl3 or DMSO-d6 solutions with a Varian VXR 200 spectrometer or a Varian Mercury Plus 400 spectrometer. Peak positions are given in parts per million (δ) downfield from tetramethylsilane as an internal standard, and J values are given in hertz. Positive-ion electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectra were recorded on a double-focusing Finnigan MAT 95 instrument with BE geometry. Melting points (mp’s) were determined on a Buchi-Tottoli apparatus and are uncorrected. The purity of the tested compounds was determined by combustion elemental analyses conducted by the Microanalytical Laboratory of the Chemistry Department of the University of Ferrara with a Yanagimoto MT-5 CHN recorder elemental analyzer. All tested compounds yielded data consistent with a purity of at least 95% as compared with the theoretical values. All reactions were carried out under an inert atmosphere of dry nitrogen, unless otherwise indicated. Reaction courses and product mixtureswere routinely monitored by TLC on silica gel (precoated F254 Merck plates), and compounds were visualized with aqueous KMnO4. Flash chromatography was performed using 230–400 mesh silica gel and the indicated solvent system. Organic solutions were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. All chemicals and reagents were purchased from Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich) or Alfa Aesar (Johnson Matthey Co.).

General Procedure A for the Synthesis of Compounds 6a–n

To a cold solution (−5 °C) containing the appropriate 2-nitrobenzonitrile 5a–g or 2-chloro-3-cyanopyridine 5h,i (5 mmol) and methyl/ethyl thioglycolate (5 mmol) in DMF (5 mL) was added dropwise a solution of KOH (1.12 g, 20 mmol, 4 equiv) in water (2.5 mL). The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 1 h and added to ice water. The mixture was extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 15 mL), and the combined organic extracts were washed with water (2 × 5 mL) and brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel to give 6a–n.

General Procedure B for the Synthesis of 3-Compounds 7a–n

In a dry three-neck round-bottom flask, anhydrous CuBr2 (536 mg, 2.4 mmol) and tert-butyl nitrite (360 μL, 3 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous acetonitrile (10 mL) under an Ar atmosphere. The resulting mixture was warmed at 65 °C and the appropriate derivative 6a–n (2 mmol) in acetonitrile (5 mL) was slowly added. The reaction was complete after 2 h, as monitored by TLC. The dark mixture was allowed to reach room temperature, poured into a saturated aqueous NH4Cl solution (10 mL), and extracted with CH2Cl2 (30 mL). The organic phase was washed twice with a saturated aqueous NH4Cl solution (10 mL) and brine (10 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated at reduced pressure to furnish a residue that was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel to give 7a–n.

General Procedure C for the Preparation of Compounds 4a–n

A dry Schlenk tube was charged with dry toluene (5 mL), the appropriate bromo derivative 7a–n (0.5 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (13 mol %, 15 mg), rac-BINAP (4 mol %, 15 mg), CsCO3 (230 mg, 0.7 mmol, 1.4 equiv), and 3,4,5-trimethoxyaniline (137 mg, 0.75 mmol, 1.5 equiv) under Ar, and the mixture was heated at 100 °C for 18 h. After cooling, the mixture was filtered through a pad of Celite and the filtrate diluted with EtOAc (10 mL) and water (5 mL). The organic phase was washed with brine (5 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under vacuum. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel to furnish 4a–n.

Methyl 3-[(3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl)amino]-1-benzo[b]-thiophene-2-carboxylate (4a)

Following general procedure C, the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography, using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (2:8, v/v) as the eluting solution, to furnish 4a as a yellow solid (78% yield), mp 160–161 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 3.73 (s, 6H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.92 (s, 3H), 6.33 (s, 2H), 7.12 (m, 1H), 7.46 (m, 2H), 7.82 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.83 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 52.0, 56.2 (2×), 61.2, 99.8 (2×), 105.5, 123.3, 123.4, 125.9, 127.9, 131.7, 138.1 (2×), 140.2, 146.5, 153.6 (2×), 166.0. MS (ESI): [M + 1]+ = 374.1. Anal. (C19H19NO5S) C, H, N.

Ethyl 3-[(3,4,5-tTrimethoxyphenyl)amino]-1-benzo[b]thiophene-2-carboxylate (4b)

Following general procedure C, the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography, using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (2:8, v/v) as the eluting solution, to furnish 4b as a yellow solid (>95% yield), mp 120–121 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.41 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H), 3.72 (s, 6H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 4.40 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 6.32 (s, 2H), 7.17 (m, 1H), 7.42 (m, 2H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.81 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 14.5, 56.1 (2×), 61.0, 61.2, 99.7 (2×), 110.3, 123.3, 123.4, 125.9, 127.8, 131.8, 134.5, 138.2, 140.2, 146.3, 153.6 (2×), 165.7. MS (ESI): [M + 1]+ = 388.2. Anal. (C20H21NO5S) C, H, N.

Methyl 4-Methyl-3-[(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)amino]-1-benzo[b]-thiophene-2-carboxylate (4c)

Following general procedure C, the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography, using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (2:8, v/v) as the eluting solution, to furnish 4c as a brown solid (56% yield), mp 192–194 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.36 (s, 3H), 3.64 (s, 6H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 6.00 (s, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (m, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 20.2, 52.2, 56.0 (2×), 61.1, 95.3 (2×), 113.9, 120.8, 127.2, 127.9, 133.1, 133.6, 136.7, 140.4, 142.8, 146.7, 153.9 (2×), 165.3. MS (ESI): [M + 1]+ = 388.0. Anal. (C20H21NO5S) C, H, N.

Ethyl 4-Methyl-3-[(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)amino]-1-benzo[b]-thiophene-2-carboxylate (4d)

Following general procedure C, the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography, using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (2:8, v/v) as the eluting solution, to furnish 4d as a yellow solid (48% yield), mp 120–122 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.36 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 2.36 (s, 3H), 3.61 (s, 6H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 4.35 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 6.00 (s, 2H), 7.02 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (m, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 14.4, 20.1, 56.0 (2×), 61.1, 61.3, 95.3 (2×), 114.4, 120.8, 126.1, 127.2, 127.8, 133.7, 136.7, 140.4, 142.9, 146.5, 153.9 (2×), 164.9. MS (ESI): [M + 1]+ = 402.0. Anal. (C21H23NO5S) C, H, N.

Methyl 5-Methyl-3-[(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)amino]-1-benzo[b]-thiophene-2-carboxylate (4e)

Following general procedure C, the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography, using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (2:8, v/v) as the eluting solution, to furnish 4e as a yellow solid (73% yield), mp 190–192 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.29 (s, 3H), 3.73 (s, 6H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 6.31 (s, 2H), 7.23 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (s, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.77 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 21.5, 51.9, 56.2 (2×), 61.2, 99.4 (2×), 106.3, 122.9, 125.5, 129.8, 132.1, 133.3, 134.4, 137.5, 138.2, 146.0, 153.5 (2×), 166.0. MS (ESI): [M + 1]+ = 388.0. Anal. (C20H21NO5S) C, H, N.

Methyl 6-Methyl-3-[(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)amino]-1-benzo[b]-thiophene-2-carboxylate (4f)

Following general procedure C, the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography, using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (2:8, v/v) as the eluting solution, to furnish 4f as a yellow solid (64% yield), mp 168–170 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.43 (s, 3H), 3.73 (s, 6H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 6.33 (s, 2H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (s, 1H), 8.80 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 21.7, 51.9, 56.2 (2×), 61.2, 99.9 (2×), 104.3, 123.0, 125.3, 125.6, 129.5, 134.6, 138.1, 138.4, 140.7, 146.6, 153.5 (2×), 166.1. MS (ESI): [M + 1]+ = 388.0. Anal. (C20H21NO5S) C, H, N.

Ethyl 6-Methyl-3-[(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)amino]-1-benzo[b]-thiophene-2-carboxylate (4g)

Following general procedure C, the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography, using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (2:8, v/v) as the eluting solution, to furnish 4g as a yellow solid (79% yield), mp 125–127 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.37 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 2.43 (s, 3H), 3.73 (s, 6H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 4.39 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 6.32 (s, 2H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (s, 1H), 8.82 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 14.5, 21.8, 56.1 (2×), 60.9, 61.2, 99.7 (2×), 104.9, 121.7, 122.9, 125.3, 125.5, 129.6, 138.2, 138.3, 140.6, 146.4, 153.5 (2×), 165.8.. MS (ESI): [M + 1]+ = 402.2. Anal. (C21H23NO5S) C, H, N.

Methyl 7-Methyl-3-[(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)amino]-1-benzo[b]-thiophene-2-carboxylate (4h)

Following general procedure C, the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography, using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (2:8, v/v) as the eluting solution, to furnish 4h as a cream-colored solid (70% yield), mp 170–172 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.52 (s, 3H), 3.72 (s, 6H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.93 (s, 3H), 6.34 (s, 2H), 7.10 (m, 1H), 7.33 (m, 2H), 8.80 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 19.7, 52.0, 56.1 (2×), 61.2, 99.8 (2×), 102.4, 123.6, 123.9, 127.9, 131.6, 132.5, 124.6, 138.1, 140.4, 147.2, 153.5 (2×), 166.1. MS (ESI): [M + 1]+ = 388.0. Anal. (C20H21NO5S) C, H, N.

Methyl 6-Methoxy-3-[(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)amino]-1-benzo-[b]thiophene-2-carboxylate (4i)

Following general procedure C, the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography, using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (2:8, v/v) as the eluting solution, to furnish 4i as a yellow solid (78% yield), mp 155–156 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 3.73 (s, 6H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 6.34 (s, 2H), 6.76 (dd, J = 9.2 and 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.81 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 51.8, 55.6, 56.1 (2×), 61.2, 100.0 (2×), 104.7, 113.3, 114.1, 125.4, 126.8, 137.9, 138.2, 142.5, 146.7, 153.5 (2×), 159.9, 166.0. MS (ESI): [M + 1]+ = 404.2. Anal. (C20H21NO6S) C, H, N.

Ethyl 6-Methoxy-3-[(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)amino]-1-benzo[b]-thiophene-2-carboxylate (4j)

Following general procedure C, the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography, using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (2:8, v/v) as the eluting solution, to furnish 4j as a yellow solid (69% yield), mp 155–157 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.40 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 3.75 (s, 6H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 4.36 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 6.33 (s, 2H), 6.84 (dd, J = 9.0 and 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.80 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 14.6, 55.6, 56.2 (2×), 60.8, 61.2, 99.9 (2×), 104.7, 110.1, 114.0, 125.5, 126.8, 130.5, 134.6, 138.1, 142.4, 153.6 (2×), 159.9, 165.6. MS (ESI): [M + 1]+ = 418.1. Anal. (C21H23NO6S) C, H, N.

Methyl 7-Methoxy-3-[(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)amino]-1-benzo-[b]thiophene-2-carboxylate (4k)

Following general procedure C, the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography, using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (2:8, v/v) as the eluting solution, to furnish 4k as a yellow solid (74% yield), mp 176–178 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 3.72 (s, 6H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.92 (s, 3H), 3.99 (s, 3H), 6.33 (s, 2H), 6.80 (dd, J = 7.2 and 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (m, 2H), 8.76 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 52.0, 55.8, 56.1 (2×), 61.2, 99.8 (2×), 104.2, 106.9, 118.4, 121.6, 124.8, 133.4, 134.5, 138.1, 146.8, 153.5 (2×), 154.5, 166.1. MS (ESI): [M + 1]+ = 404.0. Anal. (C20H21NO6S) C, H, N.

Methyl 3-[(3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl)amino]thieno[2,3-b]pyridine-2-carboxylate (4l)

Following general procedure C, the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography, using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (3:7, v/v) as the eluting solution, to furnish 4l as a yellow solid (52% yield), mp 176–178 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 3.74 (s, 6H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.94 (s, 3H), 6.35 (s, 2H), 7.09 (m, 1H), 7.61 (dd, J = 8.4 and 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.61 (dd, J = 4.4 and 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.88 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 52.1, 56.2 (2×), 61.2, 100.6 (2×), 110.3, 118.4, 125.6, 133.5, 135.3, 137.4, 144.6, 145.7, 150.3, 153.8 (2×), 166.0. MS (ESI): [M + 1]+ = 375.1. Anal. (C18H18N2O5S) C, H, N.

Ethyl 3-[(3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl)amino]thieno[2,3-b]pyridine-2-carboxylate (4m)

Following general procedure C, the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography, using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (3:7, v/v) as the eluting solution, to furnish 4m as a yellow solid (76% yield), mp 167–168 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.42 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 3.74 (s, 6H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 4.42 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 6.34 (s, 2H), 7.09 (m, 1H), 7.62 (dd, J = 8.2 and 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.62 (dd, J = 4.6 and 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.90 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ14.5, 56.2 (2×), 61.2, 61.3, 100.4 (2×), 104.4, 118.4, 125.7, 133.4, 135.2, 137.5, 144.4, 150.2, 153.7 (2×), 161.1, 165.7. MS (ESI): [M + 1]+ = 389.1. Anal. (C19H20N2O5S) C, H, N.

Methyl 6-Methyl-3-[(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)amino]thieno[2,3-b]pyridine-2-carboxylate (4n)

Following general procedure C, the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography, using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (3:7, v/v) as the eluting solution, to furnish 4n as a yellow solid (63% yield), mp 186–188 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.64 (s, 3H), 3.74 (s, 6H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.92 (s, 3H), 6.34 (s, 2H), 6.93 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 8.88 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 24.8, 52.0, 56.2 (2×), 61.2, 100.5 (2×), 102.1, 118.8, 122.3, 133.5, 135.2, 137.4, 144.8, 145.3, 153.7 (2×), 160.1, 166.2. MS (ESI): [M + 1]+ = 389.0. Anal. (C19H20N2O5S) C, H, N.

Antiproliferative Assays

Human T-cell leukemia (Jurkat), human B-cell leukemia (SEM), and human promyelocytic leukemia (HL-60) cells were grown in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Milano, Italy). Breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7), human non-small-cell lung carcinoma (A549), human cervix carcinoma (HeLa), and human colon adenocarcinoma (HT-29) cells were grown in DMEM medium (Gibco). Both media were supplemented with 115 units/mL penicillin G (Gibco), 115 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen, Milano, Italy), and 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). These cell lines were purchased from ATCC. CEMVbl-100 cells are a multi-drug-resistant line selected against vinblastine.24 LoVoDoxo cells are a doxorubicin-resistant subclone of LoVo cells25 and were grown in complete Ham’s F12 medium supplemented with doxorubicin (0.1 μg/mL). LoVoDoxo and CEMVbl-100 were a kind gift of Dr. G. Arancia (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy). A549-T12 cells are a non-small-cell lung carcinoma line exhibiting resistance to paclitaxel29 and were kindly donated by Prof. I. Castagliuolo (University of Padova). They were grown in complete DMEM medium supplemented with paclitaxel (12 nM). Stock solutions (10 mM) of the different compounds were obtained by dissolving them in DMSO. Individual wells of a 96-well tissue culture microtiter plate were inoculated with 100 μL of complete medium containing 8 × 103 cells. The plates were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator for 18 h prior to the experiments. After medium removal, 100 μL of fresh medium containing the test compound at different concentrations was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 72 h. The percentage of DMSO in the medium never exceeded 0.25%. This was also the maximum DMSO concentration in all cell-based assays described below. Cell viability was assayed by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide test as previously described.54 The IC50 was defined as the compound concentration required to inhibit cell proliferation by 50%, in comparison with cells treated with the maximum amount of DMSO (0.25%) and considered as 100% viable.

PBLs from healthy donors were obtained by separation on a Lymphoprep (Fresenius KABI Norge AS) gradient. After extensive washing, cells were resuspended (1.0 × 106 cells/mL) in RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated overnight. For cytotoxicity evaluations in proliferating PBL cultures, nonadherent cells were resuspended at 5 × 105 cells/mL in growth medium, containing 2.5 μg/mL PHA (Irvine Scientific). Different concentrations of the test compounds were added, and viability was determined 72 h later by the MTT test. For cytotoxicity evaluations in resting PBL cultures, nonadherent cells were resuspended (5 × 105 cells/mL) and treated for 72 h with the test compounds, as described above.

Molecular Modeling

All molecular modeling studies were performed on a MacPro dual 2.66 GHz Xeon running Ubuntu. The tubulin structure was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/, PDB code 1SA0).55 Hydrogen atoms were added to the protein, using Molecular Operating Environment (MOE),56 and minimized keeping all the heavy atoms fixed until an RMSD gradient of 0.05 kcal mol−1 Å−1 was reached. Ligand structures were built with MOE and minimized using the MMFF94x force field until an RMSD gradient of 0.05 kcal mol−1 Å−1 was reached. The docking simulations were performed using PLANTS.57

Effects on Tubulin Polymerization and on Colchicine Binding to Tubulin

To evaluate the effect of the compounds on tubulin assembly in vitro,30 varying concentrations of compounds were preincubated with 10 μM bovine brain tubulin in glutamate buFFer at 30 °C and then cooled to 0 °C. After addition of 0.4 mM GTP, the mixtures were transferred to 0 °C cuvettes in a recording spectrophotometer and warmed to 30 °C. Tubulin assembly was followed turbidimetrically at 350 nm. The IC50 was defined as the compound concentration that inhibited the extent of assembly by 50% after a 20 min incubation. The ability of the test compounds to inhibit colchicine binding to tubulin was measured as described,32 except that the reaction mixtures contained 1 μM tubulin, 5 μM [3H]colchicine, and 1 or 5 μM test compound.

Flow Cytometric Analysis of Cell Cycle Distribution

For flow cytometric analysis of DNA content, 5 × 105 HeLa cells in exponential growth were treated with different concentrations of the test compounds for 24 and 48 h. After the incubation period, the cells were collected, centrifuged, and fixed with ice-cold ethanol (70%). The cells were treated with lysis buFFer containing RNase A and 0.1% Triton X-100 and then stained with PI. Samples were analyzed on a Cytomic FC500 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). DNA histograms were analyzed using MultiCycle for Windows (Phoenix Flow Systems).

Annexin-V Assay

Surface exposure of PS on apoptotic cells was measured by flow cytometry with a Coulter Cytomics FC500 (Beckman Coulter) by adding annexin-V conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) to cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Annexin-V Fluos, Roche Diagnostic). Simultaneously, the cells were stained with PI. Excitation was set at 488 nm, and the emission filters were at 525 and 585 nm, respectively, for FITC and PI.

Assessment of Mitochondrial Changes

The mitochondrial membrane potential was measured with the lipophilic cationic dye JC-1 (Molecular Probes), as described.54 The production of ROS was measured by flow cytometry using either HE (Molecular Probes) or H2DCFDA (Molecular Probes), as previously described.54

Western Blot Analysis

HeLa cells were incubated in the presence of test compounds and, after different times, were collected, centrifuged, and washed two times with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The pellet was then resuspended in lysis buffer. After the cells were lysed on ice for 30 min, the lysates were centrifuged at 15000g at 4 °C for 10 min. The protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using the BCA protein assay reagents (Pierce, Italy). Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were resolved using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) (7.5–15% acrylamide gels) and transferred to PVDF Hybond-p membranes (GE Healthcare). The membranes were blocked with I-block (Tropix), the membrane being gently rotated overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies against Bcl-XL, Mcl-1, Xiap, p-survivin (Thr34), PARP, cleaved caspase-9, p-cdc2Tyr15, cdc25c (Cell Signaling), caspase-3 (Alexis), cyclin B (Upstate), or β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h at room temperature. The membranes were next incubated with peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies for 60 min. All membranes were visualized using ECL Advance (GE Healthcare) and exposed to Hyperfilm MP (GE Healthcare). To ensure equal protein loading, each membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody.

Antitumor Activity in Vivo

The in vivo cytotoxic activity of compound 4i was investigated using a syngeneic murine hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (BNL 1ME A.7R.1) in Balb/c mice.53 Male mice, 8 weeks old, were purchased from Harlan (S. Pietro al Natisone Udine, Italy), and tumors were induced by a subcutaneous injection in their dorsal region of 107 cells in 200 μL of sterile PBS. The animals were randomly divided into three groups, and starting on the second day, they were daily dosed intraperitoneally (ip) with 7 μL/kg free vehicle (0.9% NaCl containing 5% polyethylene glycol 400 and 0.5% Tween 80), compound 4i, or the reference compound CA-4P, both at the dose of 5 mg/kg of body mass. Tumor sizes were measured daily for 7 days using a pair of calipers. In particular, the tumor volume (V) was calculated by the rotational ellipsoid formula: V = AB2/2, where A is the longer diameter (axial) and B is the shorter diameter (rotational). All experimental procedures followed guidelines recommended by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Padova University.

Statistical Analysis

Unless indicated otherwise, the results are presented as the mean ± SEM. The differences between different treatments were analyzed using the two-sided Student’s t test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) SHCH2CO2CH3 or SHCH2CO2C2H5, KOH, H2O, DMF; (b) tBuONO, CuBr2, CH3CN, 65 °C; (c) 3,4,5-trimethoxyaniline, Pd(OAc)2, BINAP, CsCO3, PhMe, 120 °C, 16 h.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Alberto Casolari for excellent technical assistance.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- CA-4

combretastatin A-4

- CA-4P

combretastatin A-4 phosphate

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- KOH

potassium hydroxide

- tBuONO

tert-butyl nitrite

- CuBr2

copper(II) bromide

- Pd(OAc)2

palladium(II) acetate

- BINAP

rac-2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphane)-1,1′-binaphtyl

- CsCO3

cesium carbonate

- J

coupling constant (in NMR spectroscopy)

- PBL

peripheral blood lymphocyte

- PHA

phytohemaglutinin

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- PI

propidium iodide

- PS

phospha-tidylserine

- Δψmt

mitochondrial transmembrane potential

- JC-1

5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbo-cyanine

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- HE

hydroxyethidine

- H2DCFDA

2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- PARP

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- IAP

inhibitor of apoptosis protein

- HBSS

Hank’s balanced salt solution

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- SDS–PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Detailed characterization of synthesized compounds 6a–n and 7a–n and molecular modeling studies of 4f, 4g, 4h, 4i, 4j, 4k, and 4n (Figure 1s). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Amos LA. Microtubule structure and its stabilisation. Org Biomol Chem. 2004;2:2153–2160. doi: 10.1039/b403634d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walczak CE. Microtubule dynamics and tubulin interacting proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:52–56. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dumontet C, Jordan MA. Microtubule-binding agents: a dynamic field of cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2010;9:790–803. doi: 10.1038/nrd3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perez EA. Microtubule inhibitors: differentiating tubulin inhibiting agents based on mechanisms of action, clinical activity, and resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2086–2095. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson RO. New tubulin targeting agents currently in clinical development. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2008;17:707–722. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.5.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pellegrini F, Budman DR. Review: tubulin function, action of antitubulin drugs, and new drug development. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:264–273. doi: 10.1081/cnv-200055970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yue QX, Liu X, Guo DA. Microtubule-binding natural products for cancer therapy. Planta Med. 2010;76:1037–1043. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1250073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JF, Harris LN. Antimicrotubule agents. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer Principles & Practice of Oncology. 8. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2008. pp. 447–456. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pettit GR, Singh SB, Hamel E, Lin CM, Alberts DS, Garcia-Kendall D. Isolation and structure of the strong cell growth and tubulin inhibitor combretastatin A-4. Experentia. 1989;45:209–211. doi: 10.1007/BF01954881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin CM, Ho HH, Pettit GR, Hamel E. Antimitotic natural products combretastatin A-4 and combretastatin A-2: studies on the mechanism of their inhibition of the binding of colchicine to tubulin. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6984–6991. doi: 10.1021/bi00443a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGown AT, Fox BW. Differential cytotoxicity of combretastatins A1 and A4 in two daunorubucin-resistant P388 cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1990;26:79–81. doi: 10.1007/BF02940301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siemann DW, Chaplin DJ, Walicke PA. A review and update of the current status of the vasculature-disabling agent combretastatin-A4 phosphate (CA4P) Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2009;18:189–197. doi: 10.1517/13543780802691068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romagnoli R, Baraldi PG, Lopez Cara C, Hamel E, Basso G, Bortolozzi R, Viola G. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 2-(3′,4′,5′-trimethoxybenzoyl)-3-aryl/arylaminobenzo[b]thiophene derivatives as a novel class of antiproliferative agents. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45:5781–5791. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Martino G, La Regina G, Coluccia A, Edler MC, Barbera MC, Brancale A, Wilcox E, Hamel E, Artico M, Silvestri R. Arylthioindoles, potent inhibitors of tubulin polymer-ization. J Med Chem. 2004;47:6120–6123. doi: 10.1021/jm049360d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Martino G, Edler MC, La Regina G, Coluccia A, Barbera MC, Barrow D, Nicholson RI, Chiosis G, Brancale A, Hamel E, Artico M, Silvestri R. New arylthioindoles: potent inhibitors of tubulin polymerization. 2. Structure-activity relationships and molecular modeling studies. J Med Chem. 2006;49:947–954. doi: 10.1021/jm050809s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.La Regina G, Sarkar T, Bai R, Edler MC, Saletti R, Coluccia A, Piscitelli F, Minelli L, Gatti V, Mazzoccoli C, Palermo V, Mazzoni C, Falcone C, Scovassi AI, Giansanti V, Campiglia P, Porta A, Maresca B, Hamel E, Brancale A, Novellino E, Silvestri R. New arylthioindoles and related bioisosteres at the sulfur bridging group. 4. Synthesis, tubulin polymerization, cell growth inhibition, and molecular modeling studies. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7512–7527. doi: 10.1021/jm900016t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaukroger K, Hadfield JA, Lawrence NJ, Nolan S, McGown AT. Structural requirements for the interaction of combretastatins with tubulin: how important is the trimethoxy unit? Org Biomol Chem. 2003;1:3033–3037. doi: 10.1039/b306878a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatanaka T, Fujita K, Ohsumi K, Nakagawa R, Fukuda Y, Nihei Y, Suga Y, Akiyama Y, Tsuji T. Novel B-ring modified combretastatin analogues: synthesis and antineoplastic activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8:3371–3374. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00622-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck JR. A direct synthesis of benzo[b]thiophene-2-carboxylate esters involving nitro displacement. J Org Chem. 1972;37:3224–3226. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doyle MP, Siegfried B, Dellaria JF., Jr Alkyl nitrite-metal halide deamination rections. 2. Substitutive deamination of arylamines by alkyl nitrites and copper (II) halides. A direct and remarkably efficient conversion of arylamines to aryl halides. J Org Chem. 1977;42:2426–2431. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Queiroz M-JRP, Begouin A, Ferreira ICFR, Kirsch G, Calhelha RC, Barbosa S, Estevinho LM. Palladium-catalysed amination of electron-deficient or relatively electron-rich benzo[b]-thienyl bromids—preliminary studies of antimicrobial activity and SARs. Eur J Org Chem. 2004:3679–3685. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szakács G, Paterson JK, Ludwig JA, Booth-Genthe C, Gottesman MM. Targeting multidrug resistance in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2006;5:219–234. doi: 10.1038/nrd1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baguley BC. Multidrug resistance mechanism in cancer. Mol Biotechnol. 2010;46:308–316. doi: 10.1007/s12033-010-9321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dupuis M, Flego M, Molinari A, Cianfriglia M. Saquinavir induces stable and functional expression of the multidrug transporter P-glycoprotein in human CD4 T-lymphoblastoid CEM rev cells. HIV Med. 2003;4:338–345. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1293.2003.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toffoli G, Viel A, Tumiotto I, Biscontin G, Rossi G, Boiocchi M. Pleiotropic-resistant phenotype is a multifactorial phenomenon in human colon carcinoma cell lines. Br J Cancer. 1991;63:51–56. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verrills NM, Kavallaris M. Improving the targeting of tubulin-binding agents: lessons from drug resistance studies. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:1719–1733. doi: 10.2174/1381612053764706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kavallaris M. Microtubules and resistance to tubulin-binding agents. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:194–204. doi: 10.1038/nrc2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ganguly A, Cabral F. New insights into mechanisms of resistance to microtubule inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1816:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martello LA, Verdier-Pinard P, Shen HJ, He L, Torres K, Orr GA, Horwitz SB. Elevated level of microtubule destabilizing factors in a taxol-resistant/dependent A549 cell line with an alpha-tubulin mutation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1207–1213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamel E. Evaluation of antimitotic agents by quantitative comparisons of their effects on the polymerization of purified tubulin. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2003;38:1–21. doi: 10.1385/CBB:38:1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhattacharyya B, Panda D, Gupta S, Banerjee M. Antimitotic activity of colchicine and the structural basis for its interaction with tubulin. Med Res Rev. 2008;28:155–183. doi: 10.1002/med.20097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verdier-Pinard P, Lai JY, Yoo HD, Yu J, Marquez B, Nagle DG, Nambu M, White JD, Falck JR, Gerwick WH, Day BW, Hamel E. Structure-activity analysis of the interaction of curacin A, the potent colchicine site antimitotic agent, with tubulin and effects of analogs on the growth of MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:62–76. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Massarotti A, Coluccia A, Silvestri R, Sorba G, Brancale A. The tubulin colchicine domain: a molecular modeling perspective. ChemMedChem. 2012;7:33–42. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coluccia A, Sabbadin D, Brancale A. Molecular modelling studies on arylthioindoles as potent inhibitors of tubulin polymer-ization. Eur J Med Chem. 2011;46:3519–3525. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clarke PR, Allan LA. Cell-cycle control in the face of damage—a matter of life or death. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiyokawa H, Ray D. In vivo roles of Cdc25 phosphatases: biological insight into the anti-cancer therapeutic targets. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2008;8:832–836. doi: 10.2174/187152008786847693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donzelli M, Draetta GF. Regulating mammalian checkpoints through Cdc25 inactivation. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:671–677. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vermes I, Haanen C, Steffens-Nakken H, Reutelingsperger C. A novel assay for apoptosis. Flow cytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on early apoptotic cells using fluorescein labelled annexin V. J Immunol Methods. 1995;184:39–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00072-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.(a) Ly JD, Grubb DR, Lawen A. The mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) in apoptosis: an update. Apoptosis. 2003;8:115–128. doi: 10.1023/a:1022945107762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Green DR, Kroemer G. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science. 2004;305:626–629. doi: 10.1126/science.1099320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.(a) Cai J, Jones DP. Superoxide in apoptosis. Mitochondrial generation triggered by cytochrome c loss. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11401–11404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nohl H, Gille L, Staniek K. Intracellular generation of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:719–723. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rothe G, Valet G. Flow cytometric analysis of respiratory burst activity in phagocytes with hydroethidine and 2′,7′-dichloro-fluorescein. J Leukocyte Biol. 1990;47:440–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.(a) Chiu WH, Luo SJ, Chen CL, Cheng JH, Hsieh CY, Wang CY, Huang WC, Su WC, Lin CF. Vinca alkaloids cause aberrant ROS-mediated JNK activation, Mcl-1 downregulation, DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1159–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mendez G, Policarpi C, Cenciarelli C, Tanzarella C, Antoccia A. Role of Bim in apoptosis induced in H460 lung tumor cells by the spindle poison combretastatin-A4. Apoptosis. 2011;16:940–949. doi: 10.1007/s10495-011-0619-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Denault JB, Salvesen GS. Caspases: keys in the ignition of cell death. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4489–4499. doi: 10.1021/cr010183n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Porter AG, Janicke RU. Emerging role of caspase-3 in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:99–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mollinedo F, Gajate C. Microtubules, microtubule-interfering agents and apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2003;8:413–450. doi: 10.1023/a:1025513106330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poruchynsky MS, Wang EE, Rudin CM, Blagosklonny MV, Fojo T. Bcl-xL is phosphorylated in malignant cells following microtubule disruption. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3331–3338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matson DR, Stukenberg PT. Spindle poisons and cell fate: a tale of two pathways. Mol Interventions. 2011;11:141–150. doi: 10.1124/mi.11.2.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wertz IE, Kusam S, Lam C, Okamoto T, Sandoval W, Anderson DJ, Helgason E, Ernst JA, Eby M, Liu J, Belmont LD, Kaminker JS, O’Rourke KM, Pujara K, Kohli PB, Johnson AR, Chiu ML, Lill JR, Jackson PK, Fairbrother WJ, Seshagiri S, Ludlam MJ, Leong KG, Dueber EC, Maecker H, Huang DC, Dixit VM. Sensitivity to antitubulin chemotherapeutics is regulated by MCL1 and FBW7. Nature. 2011;471:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature09779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harley ME, Allan LA, Sanderson HS, Clarke PR. Phosphorylation of Mcl-1 by CDK1-cyclin B1 initiates its Cdc20-dependent destruction during mitotic arrest. EMBO J. 2010;29:2407–2420. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Altieri DC, Survivin IAP. Proteins in cell-death mechanisms. Biochem J. 2010;430:199–205. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Castedo M, Perfettini JL, Roumier T, Andreau K, Medema R, Kroemer G. Cell death by mitotic catastrophe: a molecular definition. Oncogene. 2004;23:2825–2837. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Connor DS, Grossman D, Plescia J, Li F, Zhang H, Villa A, Tognin S, Marchisio PC, Altieri DC. Regulation of apoptosis at cell division by p34cdc2 phosphorylation of survivin. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2000;97:13103–13107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240390697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gasparotto V, Castagliuolo I, Chiarelotto G, Pezzi V, Montanaro D, Brun P, Palü G, Viola G, Ferlin MG. Synthesis and biological activity of 7-phenyl-6,9-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[3,2-f ]quinolin-9-ones: a new class of antimitotic agents devoid of aromatase activity. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1910–1915. doi: 10.1021/jm0510676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Viola G, Vedaldi D, Dall’Acqua F, Fortunato E, Basso G, Bianchi N, Zuccato C, Borgatti M, Lampronti I, Gambari R. Induction of -globin mRNA, erythroid differentiation and apoptosis in UVA-irradiated human erythroid cells in the presence of furocumarin derivatives. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:810–825. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ravelli RBG, Gigant B, Curmi PA, Jourdain I, Lachkar S, Sobel A, Knossow M. Insight into tubulin regulation from a complex with colchicine and a stathmin-like domain. Nature. 2004;428:198–202. doi: 10.1038/nature02393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Molecular Operating Environment (MOE 2010.10) Chemical Computing Group, Inc; Montreal, Quebec, Canada: [accessed February 23: 2013]. http://www.chemcomp.com. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Korb O, Stützle T, Exner TE. PLANTS: Application of ant colony optimization to structure-based drug design. Ant Colony Optimization and Swarm Intelligence. 5th International Workshop, ANTS 2006; Brussels, Belgium. Sept 4–7, 2006. [Google Scholar]; Dorigo M, Gambardella LM, Birattari M, Martinoli A, Poli R, Sttzle T, editors. LNCS. Vol. 4150. Springer; Berlin: 2006. pp. 247–258. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.