Abstract

The present study used qualitative methods to examine if and how African Americans with cancer use religiosity in coping. Patients (N=23) were recruited from physician offices and completed 1–1.5 hour interviews. Themes that emerged included but were not limited to control over one’s illness, emotional response, importance of social support, role of God as a healer, relying on God, importance of faith for recovery, prayer and scripture study, and how one makes sense of the illness. Participants had a great deal to say about the role of religion in coping. These themes may have utility for development of support interventions if they can be operationalized and intervened upon.

Keywords: Religion, Spirituality, Cancer, Coping, Quality of Life, African American, Qualitative Research

African Americans bear a disproportionate cancer burden in the US, suffering from the highest mortality relative to other groups (American Cancer Society, 2004). Cancer mortality for all sites combined are higher in African Americans than in Whites for both sexes, 1.4 times higher in males and 1.2 times higher in females. With the exception of female breast cancer, the incidence rates for all the major cancers are higher in African Americans than in Whites; mortality rates for the all the major cancers except for female lung cancer are higher in African Americans than Whites (American Cancer Society, 2004). Though disparities continue in cancer incidence and mortality, people with cancer across all racial/ethnic groups are living longer, and there is an increased focus on coping and survivorship. It is important to identify the specific factors that facilitate coping, for use in support and survivorship interventions. For African Americans, an important cultural factor in coping appears to be religion (Taylor & Chatters, 1986; Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990). However, less is known about the specific role of religion in coping, in other words how does religion help or hinder coping with cancer?

Religion Among African Americans

Religiosity plays an important role in the lives of many African Americans, and is an important part of the social and cultural fabric (Taylor & Chatters, 1986). African Americans are generally more religiously-involved than other groups (Levin & Taylor, 1993; Ferraro & Koch, 1994; Levin, Taylor, & Chatters, 1994; Taylor, Chatters, Jayakody, & Levin, 1996; Levin & Taylor, 1997; Chatters, Taylor, & Lincoln, 1999). Lincoln and Mamiya (1990) note that “much of black culture was forged in the heart of black religion and the Black Church” (p. 10). Church provides African Americans with an important source of social support (Taylor, 1993). Prayer improves ability to cope with stressful life events (Taylor & Chatters, 1986; Ellison & Taylor, 1996), including serious illness.

Although acknowledging the current scholarly debate concerning definitions of “religiosity” and “spirituality”, (Zinnbauer, Pargament, Cole, et al., 1997) this paper will focus on the term religiosity. Religiosity involves organized worship and practice, as well as theology (Jenkins & Pargament, 1995). Spirituality is harder to operationalize, may involve transcendent experiences, and can include religion. In this paradigm, religiosity may be seen as a component of spirituality, as spirituality refers to a broader construct than religiosity. The present study examined the role of religious beliefs and participation in coping with cancer. It is recommended that religiosity and spirituality be examined and measured separately in oncology research (Flannelly, Flannelly, & Weaver, 2002).

Role of religiosity in cancer coping

Several studies note a role of religiosity in the cancer experience. Religiosity and health are closely linked in African American culture, with explanations of illness and healing being associated with God and faith (Stroman, 2000). The majority of a random sample of nurses report referring cancer patients to clergy and chaplains (Taylor & Amenta, 1994). As a result of having cancer, individuals often increase frequency of prayer, church attendance, and their faith becomes more important (Moschella, Pressman, Pressman, & Weissman, 1997). In addition, the cancer patients expressed the belief that God has a reason for their suffering that cannot be explained or understood. In a Southeastern sample, most expressed the belief that God works through doctors and felt that they would place religious concerns above speaking with a physician if they were seriously ill (Mansfield, Mitchell, & King, 2002).

Religiosity is reported to aid with cancer coping, and the literature indicates religious concerns are important to health and quality of life among cancer patients (Mytko & Knight, 1999; Laubmeier, Zakowski, & Bair, 2004). Cancer patients were found to draw meaning from their suffering (Kappeli, 2000). In a study examining religious differences between African American and White breast cancer survivors, African American women reported relying on their religiosity as a coping mechanism more than did White women (Bourjolly, 1998), and to use prayer in coping with breast cancer (Henderson & Fogel, 2003). African American women also scored higher than White women on scales measuring public and private religiousness, with racial differences persisting even after controlling for income. The role of God and religion in coping with breast cancer was reported particularly by women who had “personal, social, or economic barriers” (p. 33) to health care. African American men also use religion to cope with prostate cancer (Bowie, Sydnor, & Granot, 2003). Among cancer patients, prayer is used and found to be helpful, even though it can sometimes be accompanied by religious conflicts such as unanswered prayers (Taylor, Outlaw, Bernardo, & Roy, 1999).

Pargament and colleagues have developed three religious coping styles: Self-Directing, Collaborative, and Deferring (Phillips, Pargament, Lynn, & Crossley, 2004; Pargament, Tarakeshwar, Ellison, & Wulff, 2001; Pargament, Kennell, Hathaway, Grevengoed, Newman, & Jones, 1988). These researchers have conducted extensive research on religious coping with health issues (Pargament, 1997; Emery & Pargament, 2004; Pargament, Zinnbauer, Scott, Butter, Zerowin, & Stanik, 2003), as well as other stressors (Butter & Pargament, 2003; Dubow, Pargament, Boxer, & Tarakeshwar, 2000), and among a variety of world religions (Pargament, Poloma, & Tarakeshwar, 2000; Tarakeshwar & Pargament, 2003). Research indicates that people diagnosed with various forms of cancer tend to use religion to cope with the diagnosis and subsequent issues that arise for them (Bowie, Curbo, Laveist, Fitzgerald, & Pargament, 2001; Gall, 2000; Jenkins & Pargament, 1995).

In a sample of elderly patients with cancer (93% White), both intrinsic religiosity and spiritual well-being were associated with hope and positive mood states (Fehring, Miller, Shaw, 1997). In addition, intrinsic religiosity was negatively associated with depression and negative mood states. A review of the literature on religion and coping with illness suggests that religion serves to buffer stress (Siegel, Anderman, & Scrimshaw, 2001). Religion is thought to help adjustment to illness by helping to provide an interpretive framework for people, aiding in coping, and providing social support.

Quality of life

It has been suggested that measures of religiosity and spirituality be included in quality of life studies, given their importance to those dealing with cancer, and the priority of understanding the role of body, mind, and spirit (Mytko & Knight, 1999). In a study of quality of life among leukemia and lymphoma survivors, it was reported that patients experience positive outcomes from their cancer experience and it is thought that those with higher quality of life are those that were able to cognitively reframe or make meaning of their cancer experience (Zebrack, 2000).

The relative contributions of religious and spiritual (defined as existential) well-being were examined with regard to symptom distress and quality of life among a sample of patients with various forms of cancer (96% White; Laubmeier, et al., 2004). Existential well-being played a more important role than religious well-being in this sample. This may be a function of the demographic composition of the sample. Among individuals with terminal cancer, those who reported more advanced stages of faith had higher quality of life than those at more simple stages of faith (Swensen, Fuller, & Clements, 1993). In a sample of African American and White breast cancer survivors, nonreligiousness was a negative predictor of breast cancer survival for African American women more than for White women (Van Ness, Kasl, & Jones, 2003). In a study of hospitalized cancer patients in Norway, a 2-item measure of religiosity (belief in God; extent to which religion has been of support during cancer experience) was predictive of satisfaction with life and negatively associated with hopelessness (Ringdal, 1996). Most of the patients reported that their religiosity did provide them with support in the cancer experience. A marginal association was found between the religiosity measures and survivorship.

Why is it important to know how religiosity relates to cancer coping?

It is important to learn about the complex relationship between religiosity and cancer coping and survivorship among African Americans. Cancer can be a frightening experience. Because there is often no known cause of cancer, and prognoses and recurrence are often uncertain, it may be seen as somewhat uncontrollable and therefore quite stressful. As a result, individuals may look to their religious beliefs in thinking about cancer. Cancer fatalism is defined as “the belief that death is inevitable when cancer is present” (Powe, 1994; p. 41). Powe found that cancer fatalism increased as knowledge, income, and education decreased, and African Americans reported higher cancer fatalism scores than did Whites. Religiosity may be associated with cancer-related coping more than others diseases because of this notion of uncontrollability.

The present study

The present study used qualitative methods to examine the specific perceived role of religiosity in cancer coping among African Americans with various cancer diagnoses. There is a well-established positive association between religiosity and cancer coping in the literature. The next step is to determine how religiosity relates to coping, or which aspects of religiosity are important for coping with cancer. If more is known about the mediators of this relationship, we will be better able to inform faith-based support efforts and improve their efficacy. For example, an intervention could direct African Americans to activate their social support network to help them cope with stress. This approach could then be tested using a controlled trial to compare it with existing cancer support and survivorship programs. The NIH research agenda for social science research involves “expanding research on social and interpersonal factors that influence health, including…religion and spirituality” and the “cultural, social, and biological mechanisms through which they affect health” (Bachrach & Abeles, 2004).

Method

Participant sampling and eligibility criteria

Data collection was divided equally between the Morehouse School of Medicine (MSM) and University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) sites, and is discussed elsewhere (Schulz, Holt, Caplan, Blake, Southward, Buckner, & Lawrence, 2008). Several oncology clinics at each site assisted with the identification of African American patients. Several methods were used to recruit patients through these provider offices including: 1) providers sent patients a letter about the study, inviting participants to call study staff for more information; 2) providers posted study fliers in their offices that invited patients to call for information about the study; 3) providers told potentially eligible patients about the study and invited them to call the coordinator, or obtained patients’ assent to be called by the study coordinator. Eligible patients were screened by telephone, and were African Americans with a cancer diagnosis at least 6 months ago but not more than 5 years ago. Five years was the upper bound because after that period, coping may take on a different meaning, as patients are generally considered to be in remission after five years. Six months was the lower bound, to allow time for treatment and the initial adjustment period. Patients with any type of cancer were eligible, except for skin cancer, which is generally not life-threatening. Patients with melanoma were eligible.

Interviewing and data collection

At the UAB site, recruitment and data collection was conducted through the Recruitment and Retention Shared Facility. At the MSM site, the Clinical Research Center conducted these activities. These units have specialized expertise in recruitment and data collection for medical research studies. In order to main consistency of data collection between the two sites, the protocols were standardized and the interviewers were trained together. Interviewers were African American females, thoroughly trained in the interview protocol and had the sensitivity required for interviewing a patient sample. Prospective participants called their respective study coordinator who screened them for eligibility. Those who were eligible and interested made an appointment to be interviewed while on site for their medical appointment (43%), or in their homes if they felt more comfortable there (48%). One interview was conducted at a workplace and another in a community setting.

Written informed consent was obtained from participants. The consent document was summarized verbally for each participant and time taken to ensure that the participant understood what their involvement would entail. Interviewers began by building rapport by asking how the patient had been doing lately and then going back to the time of diagnosis and retracing what that experience was like for the patient. Interviewers then asked about resources used in coping, and probes specifically about religiosity. Participants were asked to discuss whether religion gave them strength and comfort during their cancer diagnosis and treatment, and if so, in what ways; whether religion can make a difference in illness progression or recurrence; what are some factors that can play a role in cancer recovery and recurrence; the role of religion in helping deal with stress; and whether religion had ever been a negative factor in their coping. Participants were provided with an incentive in the amount of $25 for their time and travel.

Qualitative data analysis

Interviews were audiotaped and later transcribed verbatim for analysis. Three audio tapes from the MSM site were inaudible, and thus are not included in the present analysis. An inductive process was used in the data analysis using an open coding method (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This is because we did not have a pre-conceived notion of what we would find, nor any predominant theory to guide the analysis. Each member of the investigative team reviewed the transcripts, noting themes and patterns, and developed a preliminary list of themes (codes). A consensus agreement of the common dominant themes/codes, was used to develop a codebook, which included a definition of each theme, criteria for inclusion and exclusion, and sample illustrative quotes. Two experienced coders (CH & ES) trained the remainder of the team to conduct the coding. The entire team of seven investigators was trained to use the codebook, beginning with a random sample of 10% of the dataset. After training, the group then split into pairs, with each pair coding a portion of the dataset, and each member working independently. Discrepancies within each pair of coders were discussed and adjudicated. For each code, patterns of usage were examined. Member checking was conducted to increase the validity of the coding categories (Krefting, 1991). After the initial coding, participants were mailed a summary of the study findings. Participants were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with each of the codes and their definitions and to provide any comments and feedback if they had any. The participants reported overwhelming agreement with the themes. Several indicated minor additional comments but none of these impacted the coding scheme.

Results

Participant characteristics

The 23 patients (15 from Alabama sample; 8 from Georgia sample) ranged in age from 21 to 80, with a mean age of 59.19 years (SD = 13.96; median age was 57.78). Fourteen (60.9%) were women and nine (39.1%) were men. One (4.3%) had completed elementary school, 3 (13%) had completed some high school, 5 (21.7%) had completed high school or obtained a general equivalency diploma (GED), 6 (26.1%) attended 1–3 years of college or technical school, 7 (30.4%) attended 4 or more years of college, and 1 (4.3%) did not answer the question. One (4.3%) was a member of an unmarried couple, 2 (8.7%) were never married, 9 (39.1%) were married, 3 (13%) were separated, 3 (13%) were divorced, and 5 (21.7%) were widowed. Four (17.4%) were employed for wages, 2 (8.7%) were self-employed, 1 (4.3%) had been out of work for less than a year, 1 (4.3%) had been out of work for more than a year, 1 (4.3%) was a student, 5 (21.7%) were unable to work, and 9 (39.1%) were retired. Six (26.1%) had an annual household income before taxes of under 10k, 4 (17.4%) were in the 10–15k bracket, 2 (8.7%) were in the 15–20k bracket, 2 (8.7%) were in the 25–35k bracket, 4 (17.4%) were in the 35–50k bracket, 2 (8.7%) were in the 50–75k bracket, 2 (8.7%) were in the 75k or more bracket, and 1 (4.3%) indicated don’t know/not sure. Twenty-two (95.7%) had attended a place of worship within the past 12 months. Typical religious service attendance was 4 or more times per month for most (15; 68.2%), though 7 (31.8%) attended 1–3 times per month (1 participant did not answer this question). Participation in religious activities such as Bible study or choir practice ranged from 4 or more times per month (12; 52.2%) to 1–3 times per month (5; 21.7%) to 0 times per month (6; 26.1%). Twenty-two (95.7%) indicated that they were Christian, while 1 indicated they did not belong to a religious group. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the participants across two study sites.

God-help

God was seen as another person in the participants’ lives that stands beside them and provides support to them through the cancer experience (AL female 3-year breast cancer survivor: “I am doing absolutely wonderful. God has been taking care of me.”; AL female 2.5-year breast cancer survivor: “So I just believe whatever the Lord gives you He has already provided a means to deal with it.”). God was seen as helping the participant to “pull through” and many others mentioned that they would not have made it had it not been for being able to rely on God (GA female 2.5-year breast cancer survivor: “If it hadn’t been for God, I couldn’t cope with nothing.”). God was seen as providing insights or guidance to some (AL female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor: “I prayed a lot and I asked the Lord to help me and show me what He wanted me to do.”; AL male 2-year prostate cancer survivor: “No, there is a to me, a supreme being that we ask for guidance, forgiveness, strength, knowledge, so I do believe there is a supreme being.”). The feeling that God would make things better appeared to provide a great sense of comfort and strength to the participants, and perhaps helped to ease their stress as well (GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “The only way to beat the stress is Love, Joy, and Peace and you don’t get it without the relationship with Jesus Christ.”). The presence of God in the lives of the participants was viewed as important as the social support provided from friends and family members. Some participants indicated that God was there to provide support when nobody else was (AL male 2-year survivor of cancer under the tongue: “As you reading the Bible you got to trust the good master and He will help you pull through it, because sometimes you don’t have no one else but Him to help you.”).

Faith/belief

The role of having faith and a belief in God was viewed as highly important for coping (GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “If you just keep faith, knowing that there is going to be a better day and things are not going to keep going down…”) and recovery (AL female 3-year cervical cancer survivor: “We had prayer, we had a prayer service and somebody came around and prayed all the time and um, my own prayer. I had to have faith in God to heal me, if I didn’t believe and have the faith prayer, I feel like, all the praying in the world would not have helped because me myself have to believe and have faith.”; GA male 3-year prostate cancer survivor: “Well like I say, you must go through the right procedures and follow your doctor’s instructions, do all of that to the letter and then hold your faith.”) and in the avoidance of cancer recurrence (AL female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor: “…faith and prayer and knowing that through faith and prayer, everything will be alright. But you got to believe that, you can’t just say it, you got to believe.”). Faith/belief/trust was also reported to bring strength and comfort (AL male 3-year throat cancer survivor: “I think just reading it gave me a consolation that um His word, just trusting and believing in His word and they was following up with scriptures where you can go to the Bible and find it and read it and you know you get more consolation, I got more consolation in reading His word, you know.”).

When asked whether one’s faith had increased, decreased, or stayed the same since their experience with cancer, most indicated that their faith had increased (AL female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor: “I am better than what I was before and it made my faith stronger than what it was when I first started at first I had faith but I don’t think I had enough faith to say that I was going to be alright. That I ain’t worry ‘bout nothing, I would say that I’m alright, but I wasn’t sure. But through my church family and my pastor and they prayed for me. I mean my faith is renewed and stronger.”), though some indicated that it had stayed the same, due to the idea that it had always been strong (AL male 3-year lung cancer survivor: “My faith stayed just like it is until the good Lord comes. It won’t let me change.”).

Prayer

The role of prayer was viewed as important in coping with and recovering from cancer. In times of need, one could always pray and receive strength and coping (AL female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “…I just prayed and that’s the way I, I keep myself going. I always talk to the Lord, all through the night, through the day, and that way I don’t think about that I had cancer.”; GA female 4-year breast cancer survivor: “I just went to pray about it and asked the Lord that His will be done.”). Prayer was used to feel better (AL female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor: “Well, I found comfort in knowing that no matter what was going on, I could always pray.”) and to decrease stress (AL male 2-year lung cancer survivor: “Um, strength you know I can pray to the Lord and ask Him to help me ‘cause he showed me a lot of things. He helped me with a lot of crisis, bills, and all this you know just help me sometimes to forget, to go fishing and relax and just take it easy and stop thinking about this because what happens is gonna happen, you just got to face it.”).

The prayers of others is also important in the cancer experience (GA female 2.5-year breast cancer survivor: “I may tell one other person and that is my prayer partner. My prayer partner is a nurse and she can handle the burden.”), including the laying on of hands (AL male 3-year throat cancer survivor: “…I think I just had some good people praying for me you know I went to church, I went to different churches and I let them know and I got up and went to the altar and they put hands on me, they put healing oil and I know that I could feel it. I could just feel the spirit going through me even when they are praying and touching me you know I could feel His presence, His spirit and I felt reassurance from them that He, He is going to handle this and He did handle this. Nobody but Him.”). However, this patient also indicated that one must have a strong belief and faith for the prayers to be effective (AL male 3-year throat cancer survivor: “…prayers go up and blessings come down. I believe in His word because it never fails and prayer will change things, you got to believe it and receive it.”; AL male 3-year throat cancer survivor: “…I think that if you take it to the Lord and pray and take it to Him and ask Him to heal your body and I think that if it’s His will that He will do it, if you trust and believe it then it is already done.”).

Affective response

Participants reported experiencing an array of emotions in the context of their cancer experience, from initial emotions such as anger (AL male 2-year lung cancer survivor: “…I have been doing pretty good, I have been taking my treatment all the time and stuff like that but I get a little angry sometimes you know with the doctors, I guess that’s just all a part of it, I don’t mean anything but I do get upset.”), denial (AL female 3-year cervical cancer survivor: “…Yeah, I did not talk to nobody, I didn’t say what the doctor said or nothing. I guess I was trying to accept it myself. I was in denial.”), shock (AL male 1-year neck cancer/Hodgkins disease survivor: “…you don’t think oh um 16 years old, I can catch cancer, you don’t really think, it never crosses your mind that it can happen to you so that was just a total shock for me…so I mean it was just a big surprise, just totally shocking.”), crying (AL female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor: “Well I cried, I cried a lot. Then I called my momma and I told her and I cried with her.”), depression (AL female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor: “…I have my moments of depression, doubts…”), embarrassment/shame (AL female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “Um, the first thing I was thinking about, I was embarrassed, like um I wasn’t gonna have but one breast and that kinda made me feel ashamed, that is what it really did…”), fear (AL male 3-year neck/throat cancer survivor: “…They say I worry so much I don’t know where the ulcer come from. I am worried about this cancer you know. I am trying to live, can’t breathe at night and I get where I can’t swallow and it scares me.”), and self-pity (AL male 3-year neck/throat cancer survivor: “…It’s a hurting feeling you know, feeling sorry for yourself, you think some people be against you like they don’t even want you around and like its some kind of disease, like a disease they can catch, it’s not contagious.”).

The emotional response appeared to move from these types of emotions, to feelings of acceptance (AL male 2-year lung cancer survivor: “…I ain’t said I can whoop it, but I am feeling a heck of a lot better now that I have accepted it, I just take it easy.”), hope (AL male 3-year neck/throat cancer survivor: “I just go ahead and live from day to day. Just wishing, hoping, and praying. Ain’t too much I can do about it.”), staying positive (AL female 3-year breast cancer survivor: “But I think it’s a good thing that if we try like I said to stay positive, stay upbeat, live your life you know and think I am doomed now, because I have gotten this diagnosis or I have been battling this illness that you know just live your life and enjoy it you know, be the person you want other people to be.”), and the worry being replaced with a focus on living (GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “…Jesus is righteous, but in following in his foot steps, each day you come closer and closer to being the righteous that he calls us to be. And by it being a daily practice means I have love, joy, and peace.”). Some hid their emotions, feeling hurt on the inside while trying to appear strong on the outside. Others felt that their religion helped them to ease their fears (GA female 2.5-year breast cancer survivor: “So anytime the enemy has to bring any doubt, skepticism, unbelief, of any kind of fear in your heart, you just say My Lord, My God, has not given me a spirit of fear, but one of power and of love, and of sound mind, and I will not operate in fear.”).

Social support

Perhaps the most important (along with support from God) aid to coping with cancer was social support. This included support from family members (AL male 3-year neck/throat cancer survivor: “A lot of times, I just takes it off my mind some times but you know it is hard to get off my mind, I sit around and my brother comes around and we play dominos and we play cards, you know, it is just something to do, to have something to do.”; GA female 3-year breast cancer survivor: “I had support. Not a lot of family support, but I had my daughter. I had, as you guys are going to talk about later, spiritual support.”; GA male 5-year prostate cancer survivor: “Knowing that my family is there for me.”), including the church family (AL female 2.5-year breast cancer survivor: “…and with my church members they’re all there calling to see how I was doing so, that helps you to go on through and you know and not spend the time having a pity party but, that’s all you will do if you don’t have something else to do.”). Support may have come in the form of emotional support (AL female 1.5-year breast cancer survivor: “And sometimes you can draw strength from other people.”) or instrumental support (AL male 3-year throat cancer survivor: “…my wife still does the carrot juice for me and we heard that carrot juice is pretty good you know for cancer…”).

Control beliefs

Many participants indicated that they did not feel they had control over their cancer, whether it would be cured, or whether it would recur (AL female 3-year breast cancer survivor: “…like I said it made me realize that you know what I am not really in control of this, you know um. If I was in control I would not have received a diagnosis and I would not have had cancer, you know so I think that it makes you aware that you are not really in control, there is a higher power.”; AL male 3-year neck/throat cancer survivor: “What I said is sometimes the medication helps, the most thing of all, I put it out of my hands. I put it in the Lord’s hand so God has helped me cope with it, that’s what I say, the medication helped some but still that don’t get rid of the cancer.”; GA female 2.5-year breast cancer survivor: “When I got in the car I said God, I am not going to deal with this. You got this. I went on about my business getting home and did my regular routine and nobody even questioned me. I just simply dismissed it and put it into God’s hands.”).

Some participants felt that God was in control of their illness prognosis (AL female 2.5-year breast cancer survivor: “…you can know as much as you can and you still won’t be prepared for some of the things that will happen and this is why I know that the Lord is in control…”), and by realizing that this was the case, one could be freed from some of the stress of the situation (AL female 2.5-year breast cancer survivor: “…[when asked what is the main thing that determines recovery/recurrence]: Oh, the Lord. I have no control over this. Like I said, I had no control over, being diagnosed with it. So I am not going to spend my life worrying about if it will come back…”).

Many participants believed that one could will themselves well. They believed that the mind holds great power, so that by thinking positive or negative thoughts or speaking positively or negatively, a person could influence the prognosis (AL female 3-year breast cancer survivor: “…And simply because and you may have heard this but, I am a country girl, I grew up I the South so, you know the mind is powerful, you can will yourself ill or you can will yourself well and I truly believe that you know.”). Participants did not want to claim or verbalize an ill feeling (AL female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor: “…one of my cousins in Ohio said if you don’t claim it then you don’t have to worry about it. And I’m like what you mean don’t claim it? She said if you got a problem, don’t say well so and so and so, if you claim it, you make it so, giving the devil power. But if you don’t claim it, if you don’t say that it is what it is then you don’t have to worry about it.”; GA male 3-year prostate cancer survivor: “I just say that the cancer is not there. It is gone. If I accept it and say that I have it then I am speaking it on to myself. I speak it off me.”). Participants would cope by staying, speaking, and thinking positive (AL female 3-year breast cancer survivor: “…the words that you speak out of your mouth and the Bible tells us the power of life and death lies in the tongue so you have to speak positive things out of your mouth and just live it.”; AL female 3-year breast cancer survivor: “…like I said you know I said a little bit earlier about controlling your thought you know. Will yourself well. Think about living a long, healthy, happy life.”).

Meaning making

When faced with a life-threatening illness such as cancer, participants felt the need to search for an explanation of why this happened to them. This often involved a frustrated or angry “why me” experience (AL female 1.5-year breast cancer survivor: “But my first thought was why me, at 58? When I had my mammograms every year and every year they would tell me the same thing, everything is okay.”), later followed by an interpretation that involved the context of one’s religion/spirituality (AL female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor: “It makes me believe that no matter what you are going through and no [matter] what happens in your life that the Lord has a purpose for you and that He gonna see you through it. And don’t give up because when you give up, the Devil done won, he done had his way.”). Some felt that God allows things to happen for a reason (GA male 5-year prostate cancer survivor: “I believe that it is for a reason that I go through this. It was supposed to happen.”), or that God would not put more on a person than they could bear (GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “I think it plays a part in that I know that the cancer is not going to do anymore damage to me than the Lord allows.”). Others felt that God provided the cancer experience so that the participant would be able to provide testimony to others, or to make the participant stronger (AL female 2.5-year breast cancer survivor: “when you go through things that’s a test that you are put through and if you can’t stand the test then how will you have a testimony? If you don’t have a test, you will have nothing but a mony and that’ the way it is with life, if you’ve gone through some things you can share this with someone else”). The Lord’s plan was cited by many, as was the idea that God would not allow a person to die until it was “their time” (AL female 5-year ovarian cancer survivor: “And I say, they say I have cancer. And so I held my tears until I got out of the truck with him and the only thing I was telling him, I call my son [name]. And I said [name], you’re not going to leave here until the good Lord get ready for you.”).

Suffering

Participants going through cancer reported suffering through effects of treatment (AL male 3-year neck/throat cancer survivor: “…Because of the pain I am suffering, see they had me on medication, pain medication and they had me on Oxycotin 20 milligrams, they had me on Lortab 7.5 and Lortab #10, at times it just don’t work and I just have to put up with the suffering.”; GA male 5-year prostate cancer survivor: “There are times when it is kind of painful, but after I go along and get into my treatment, there is no pain at all… Sometimes I get kind of tired because of the radiation treatment, I get exhausted, but that’s all part of it.”), including side effects of medications (AL female 2.5-year breast cancer survivor: “…and about the biggest thing is that you receive the chemo and you stop it like at a month earlier, but the side effects are still in your system and you still have the side effects as the result…”). General symptoms and bodily changes were cited by many (AL male 1-year neck cancer/Hodgkins disease survivor:

“…everything with my body getting back to normal, I mean, the chemo made me darker than my skin color that is just coming back and some places I still have dark patches but it’s slowly getting better, um it’s like, I guess its kind of like a bomb just kind of blew up inside of me and everything is just recovering from that explosion you know, um my fingernails kind of turned black and they like my fingernails are kind of peeling off and my fingernails are just like growing like that black part, peeling off and I got new nails growing, my hair is just now growing back…”).

Death/mortality

The experience of cancer resulted in participants realizing their own mortality, perhaps for the first time in a real sense (AL female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor: “And I’m like okay but, at that time I didn’t believe, I just was gonna die and then I’m like who gonna take care of my children and what I’m gonna do.”; GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “He said anybody else would die of this in about 18 months. He said but you will probably make it 5 years because of your personality. I knew it wasn’t my personality, but it was Jesus inside of me.”). Some wondered how long they had to live (AL male 2-year lung cancer survivor: “Well, he told me, it was cancer and he said well it is cancerous, it is cancerous, and the lymph nodes and all like, that there and it was a slap in the face more or less, death sentence right then, the thought was, what am I going to do, who should I call, what will I do? How long you know will I live?”). Others talked about fearing death (AL male 3-year neck/throat cancer survivor: “I look and try to help people and other times and other times I worry about the hurry of death, in other words about dying from this cancer.”).

God as a healer

Participants viewed a strong role of God as a healer, either directly or through doctors and medicine (GA female 4-year ovarian cancer survivor: “I praise Him and thank Him for healing my body. And He told me that He gave me a new body. Every organ on my body is new and I thank Him for it.”; AL female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “Um, it makes a difference because you need the religion because when someone tells you got cancer most times you be afraid, the first thing you gonna think of is oh I’m going to die but if you have Jesus you will realize that you won’t have to die from cancer, you can be healed.”). Some felt that healing could only occur with God and not through doctors alone (AL male 3-year throat cancer survivor: “Well, I guess um I see it that I know that was what brought me through this um you know I can just say and it just wasn’t the medicine it was just the prayers and the belief that I got and trusting and believing in His word that He would bring me through this…”). Many felt that if they were healed, it was God’s will for them (AL female 3-year cervical cancer survivor: “He wouldn’t put no more on me than I can bear and I have not because I ask not and I asked for healing and He gave me healing.”). Others cited the notion that God gives the doctors and nurses the ability to heal (GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “After that, it was severe for about 18 months and then it began to subside and I knew that the Lord had stepped in to take care of whatever could not be taken care of by medicine. Because healing comes supernaturally and also naturally because the Lord works through doctors giving them the gift of knowledge and the ability to use it. They told me I had five years to live. I looked at them and smiled and said the Lord would take care of that.”), or that God provided the technology for the treatments (AL female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “So the Lord heal me, He took all of that cancer away. They did the surgery but He did the healing.”).

Bible/Scripture study

Many participants felt as though they received support by reading the Bible (AL male 1-year neck cancer/Hodgkins disease survivor: “…I am a strong believer of reading my Bible, I always had my scriptures I would read and you know I pulled through.”), including healing scriptures (GA female 2.5-year breast cancer survivor: “But during the course of a couple of weeks I was in my bedroom, just straightening up, and I picked up one of my Bibles and when I picked up my Bible a little piece of paper fell out with a scripture written on it. The scripture that was written on it was 1 Peter 2:24. When I saw 1 Peter 2:24, I knew that was one of the scriptures I pray when I pray for people’s healing, but most of the time I use Isaiah 53:5 [quotes scripture]…”). This activity gave comfort and reassurance to some (AL male 3-year throat cancer survivor: “…because when I read His word it gives me what I need to make me feel better you know to feel that I know that I can trust and believe into Him and His word…”; GA male 3-year prostate cancer survivor: “Oh it [my faith] has increased, based on His Word, which never comes back void.”). As one of the previous quotes illustrates, bible study was often done in conjunction with prayer.

Church

Participants cited church attendance as a way of obtaining comfort (GA female 2.5-year breast cancer survivor: “You have to pray, meditate, and go to church.”).

Adaptation

For many, having cancer involved learning to adapt to the disease (GA female 3-year breast cancer survivor: “I’m dealing with it but it’s very hard. It’s very hard to deal with. But my life has come to a halt.”). Participants discussed a desire to return to a normal life (AL male 1-year neck cancer/Hodgkins disease survivor: “…like right now I was out you know getting my resume back out just trying to start back working somewhere and I said that I would have a job next week…”). The cancer often resulted in a limited ability to do things or participants had to do things at a slower pace than they were accustomed to (GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “I used to could prepare dinner in 1 day, it takes me 3 now. I started yesterday. I am feeling a little better about it.”).

Non-religious coping

Participants also reported on secular things in their lives that helped them to cope, such as keeping busy (AL male 2-year lung cancer survivor: “My legs is aching and I go to hurting you know and I try to go fishing to keep myself amused by something and then the people that I be around…”), or focusing on the treatment regimen (GA male 5-year prostate cancer survivor: “I just asked him different questions about the operation, questions about the procedure.”), or maintaining a healthy lifestyle (AL male 2-year lung cancer survivor: “All I could think was dying you know but at that particular moment and now I see you know if I do the right thing and try to do, live right and eat right…”). Others went back to their normal routine (GA female 2.5-year breast cancer survivor: “…I went outside to pick up the hose and water my plants…I did normal things because my house was clean before I went to the hospital. I had friends to go over.”).

Thanks to God

Some participants expressed the theme of being thankful to God and praising him daily (AL male 3-year throat cancer survivor: “…she told me that she could save my voicebox, she could save all that stuff up around in my neck and I said Lord, thank you Jesus, just where I was about to give up and the Lord stepped right in on time…”; GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “[my faith] has increased because of the thankfulness. I feel that even though we thank the Lord everyday for things like waking me up this morning and all of those normal things, but when you have an illness of any sort I think the thankfulness comes more from the heart not just from the mouth.”). Others thanked God for their medical team (GA male 3-year prostate cancer survivor: “Well I can add that I thank God for people like Dr. [Name] and Dr. [Name], and these great doctors that we have today.”).

Devil talk

Several participants indicated that the Devil (Satan) may be the cause of illness, by tempting one into sinful behaviors (AL male 2-year lung cancer survivor: “…I guess, when Satan you know I’m alone and, my wife she smokes and she leaves laying there in my face and it is something just says get them and you know and that is old Satan talking to me. But so far I’ve been able to shake him off, I try to go to church every Sunday when I can, I got a piece of chicken hung in my throat ‘cause I didn’t go last Sunday…”; AL male 3-year throat cancer survivor: “Yeh, uh huh a lot of sickness we bring on ourself or the Devil gives it to us…”; AL male 2-year lung cancer survivor:

“…you know I used to just maybe laugh at people or maybe make fun of people that would be going to church on a Sunday or just when they come back from church, not just making fun of them you know, just the devil in me, and my power, you know power experience, ‘cause I have got power to turn down a drink or cigarettes and stuff like that, you know mess with all them old raggedy women I used to mess with and stuff like that, it come from my power. My life stories, is this uh, this cancer thing, I see it as a negative thing but I have to deal with it on a positive level because it’s there I can’t just sweep it under a rug.”).

The Devil may also be the cause of cancer recurrence, through this same mechanism (AL female 3-year cervical cancer survivor:

“Um, recurrence I don’t…some people don’t know God until they are in a need, one thing they get what they ask for they healing, or whatever. They remission, they scotch free or so they think. They don’t think about God no more until they get back down or something else bad happens but then God allows things to happen for a reason, teaches us things. Just like God, the Devil is busy all the time and the Devil can act like God, and some people say I feel like the Devil can do good things, to trick you, he will act like God for me a minute, but once he get you out there to do whatever, he gets you and the next thing you know, everything else is falling down hill for the Devil. Everything look like God, ain’t God.”).

No patients in the Georgia sample appeared to voice this theme in their interviews.

Religion/spirituality not negative

When asked whether religion/spirituality has ever had a negative impact on their cancer coping, participants overwhelmingly felt that it did not (AL female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor: “I have not had any negativity about [it].”; GA female 4-year ovarian cancer survivor: “[Religiosity] has never been negative to me for anything. I have been negative, but my Lord has never been negative. He doesn’t get negative, but I have. I have been negative. But then He’ll say something or something will happen and He will lift me so.”; AL female 3-year breast cancer survivor: “I wouldn’t say negative. I can’t think of an answer for that.”).

Other noteworthy findings

Particularly in the Alabama men, regarding the idea of social support, the men expressed the desire not to be over-pampered by those around them. Some felt that the support received from family and friends was too much, or more bothersome than helpful at times. Some wanted more space or solitude. Among the Georgia sample, there was a tendency for some patients not to want to let others know that they had cancer. This may include not letting coworkers know, and one participant appeared to tell her prayer partner but not her immediate family. Patients overall across both sites had a tendency not to “accept” their cancer diagnosis and would avoid openly saying things such as “I have cancer”, and some would even deny having it, which one might misunderstand as denial. However, this is likely rooted in the “power of the tongue” belief that is expressed in the “control” theme, in which speaking about things or even thinking about them gives them the power to become reality. If one does not speak of them or speaks in the opposite direction (thinking positively), then one might be cured or avoid recurrence. Finally, one participant in the Georgia sample appeared to have religious visions, or “revelations” in which she spoke of God speaking to her or revealing things to her before they happened. Her religious experience seemed to differ in this way from the remainder of the participants.

Discussion

The patients had a great deal to say about the role of religion in coping with cancer. The semi-structured interviews produced a coherent set of themes that were fairly consistent across the sample of patients, yet resulted in rich stories of personal journeys, and descriptions of faith experiences that are sometimes challenging to capture within one set of themes.

It is clear that the patients did perceive a strong role of a higher power, of their faith, and of their own will, in their healing, recovery, and avoidance of recurrence. These coupled with support received from family and friends, comprised the main factors that were perceived to facilitate coping. It appears that many patients, when first diagnosed with cancer, were confronted perhaps for the first time with their own mortality, experienced a range of negative emotions, reached for their faith, higher power (including prayer and scripture study), and others around them for coping resources, and were eventually able to make some sort of meaning out of their illness, to explain the “why me” question. Resolving the “why me struggle” appeared to help patients to cope as well. Certainly not all patients experience cancer in the same way and this represents an oversimplification of complex processes, however it may provide a useful manner in which to conceive of the cancer journey.

Previous qualitative studies of religiosity and coping

In a previous qualitative study, interviews were used to examine the meaning of spirituality for men with prostate cancer (Walton & Sullivan, 2004). Eleven men with prostate cancer were interviewed after treatment. Three categories emerged from a grounded theory analysis, including prayer, support, and coping with cancer. A social process emerged, in which the men went through four phases involving facing cancer (shock, fear, etc.), treatment choices (information gathering, decision making, etc.), trusting (self, God, surgeon, etc.), and day-to-day living (cherishing, giving/receiving, etc.). Participants in the current study reported a similar social process, as well as themes involving prayer, support, and the role of religiosity in coping.

Another qualitative study conducted a content analysis of correspondence (e.g., letters, emails, greeting cards) of a sample of ovarian cancer survivors, in the context of correspondence between members of a newsletter mailing list (Ferrell, Smith, Juarez, & Melancon, 2003). Themes that emerged included both positive and negative changes in religion and spirituality, and meaning themes including purpose in survivorship, hopefulness, and awareness of mortality. Survivorship themes and themes specific to ovarian cancer were also reported. Participants in the current study generally reported increases in faith and/or religiosity, or that their involvement remained high as it was prior to the onset of cancer. Themes involving meaning and mortality were reported in the current study as well.

In a qualitative study of African American women, Mattis (2002) examined the role of religion and spirituality in coping with adversity. Themes that emerged suggested that the women perceived religion and spirituality as helping them to accept reality, have a spiritual surrender, overcome limitations, learn life lessons, see their purpose and destiny, build character and act in accord with their moral values, grow as a person, and trust in a higher power. Findings are discussed from within the context of the meaning-making experience. Though the meaning-making experience was an important part of accepting the cancer diagnosis, the themes in the current study were more focused on religiosity and cancer, consistent with the aims and focus of the study.

In a review of the literature on spiritual beliefs and treatment decisions of African Americans, themes identified included spiritual beliefs providing comfort, coping and support, and the role of this in healing; God’s important role in physical and spiritual health; God being an instrument of the doctor; only God can decide life or death; and divine intervention and miracles can occur (Johnson, Elbert-Avila, & Tulsky, 2005). These themes were also expressed among the current study participants.

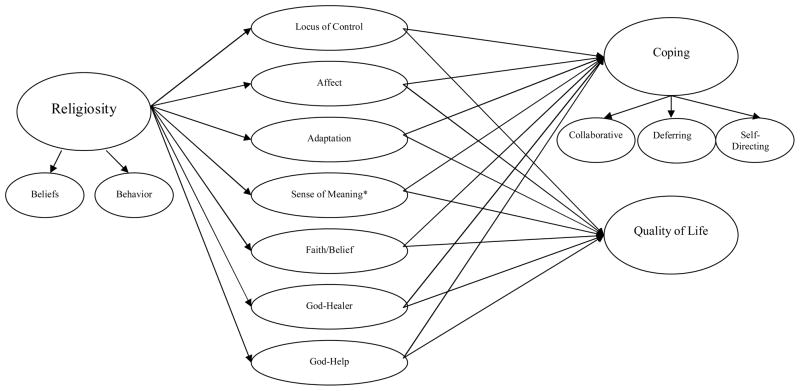

Jenkins and Pargament (1995) present a model of religion and cancer coping, involving the role of situational factors (e.g., disease stage), background variables (e.g., demographics), and resources (religious and nonreligious) leading to religious coping activities (e.g., spiritual support, congregational support, religious control), leading to self-management (e.g., emotional comfort, meaning, self-esteem), and finally adjustment and well-being. However, the model is not tested using empirical data, which is the next step in this research. The current findings suggest a similar model (see Figure 1), however the role of religiosity is perhaps defined in more detail through a series of mediators (e.g., God as a healer, God’s role in coping, role of faith/belief in coping), which were expressed as themes in the current study. The next step in this research will be to operationalize these constructs and to quantitatively test a mediational model of religion and cancer coping, with the themes identified in the present interviews as mediators of the religion-coping relationship.

Figure 1.

Role of religion in cancer coping and quality of life

Changes in religiosity as a result of serious illness

In a study of patients with HIV/AIDS, 75% indicated that their faith had strengthened at least a little as a result of their illness (Cotton, et al., 2006). In another study, 45% of patients with HIV reported increases in religiosity, 42% reported remaining the same, and 13% reported decreases (Ironson, et al., 2006). Among those reporting an increase, there was a greater preservation of CD4 cells over a study period of four years, and better control of viral load. These findings remained consistent even after controlling for a host of potential confounders including but not limited to church attendance, initial disease stage, medication, age, and social support.

Limitations

The findings of the present study should be interpreted from within the context of several limitations. First, as with most qualitative studies, the sample size was limited, and illustrates views of African American men and women with cancer, living in a Southeastern region of the United States. Findings may have differed had the geographic location been otherwise. Second, because the study was concerning religion and cancer coping, it is probable that patients who were higher in religiosity were more likely to be interested in participation than those who were less religious. Thus, the findings may over-represent the use of religious coping among the population. Third, the themes expressed in the interviews may have varied by the stage of cancer of the patient. For example, it is possible that those with more serious disease (e.g., stage 4) who were closer to facing death, may have relied more upon religious resources in coping than those with a less life-threatening (e.g., stage 1) experience. The period at which the interviews were conducted may have also affected the findings, in that patients who were closer to their diagnosis date may report more salient religious coping themes than those who are closer to the 5-year milestone. Finally, the present sample was mainly Christian, and findings may not generalize to those of Muslim, Jehovah’s Witness, Jewish, or those of Eastern faiths.

Nonetheless, the patients provided a very rich set of qualitative themes and narratives, which significantly enhance current understanding of how African American men and women use religion to cope with cancer. The present research contributes significantly beyond existing work in religious coping in several ways. First, this research focuses exclusively on cancer coping and survivorship; second, this research produced more specific information about the role of religion in cancer coping (not just that there is a role); and third, there are clear possibilities for application to cancer survivorship interventions that may result from this work.

Implications

Future studies in this area should examine the specific role of religion in coping with cancer among other demographic subgroups such as Hispanics/Latinos or Whites, or those living in different geographic regions. Studies should examine the role of religion in coping with other serious illness such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or stroke. Interventions could capitalize on factors that appear to facilitate coping, and be integrated into church-based and/or faith-based support groups. Such interventions could result in increased quality of life among cancer survivors, which is a significant issue given that more and more individuals are surviving from cancer due to medical advances in early detection and treatment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Drs. Mark Dransfield, Andres Forero, Helen Krontiras, and Sharon Spencer, for their assistance with participant access and recruitment for this study, and Pat Jackson for assistance with the data collection.

This publication was supported by Grant Number (#1 U54 CA118948-01) from the National Cancer Institute, and was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board (#X051004004).

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2004. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach CA, Abeles RP. Social science and health research: Growth at the National Institutes of Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:22–28. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourjolly JN. Differences in religiousness among black and white women with breast cancer. Social Work in Health Care. 1998;28:21–39. doi: 10.1300/J010v28n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie J, Curbo B, Laveist T, Fitzgerald S, Pargament K. The relationship between religious coping style and anxiety over breast cancer in African-American women. Journal of Religion and Health. 2001;40:411–424. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie J, Sydnor KD, Granot M. Spirituality and care of prostate cancer patients: a pilot study. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2003;95:951–954. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butter EM, Pargament KI. Development of a model for clinical assessment of religious coping: Initial validation of the process evaluation model. Mental Health, Religion, and Culture. 2003;6:175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD. African American religious participation: A multi-sample comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1999;38:132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton S, Puchalski CM, Sherman SN, Mrus JM, Pargament KI, Justice AC, Leonard AC, Tsevat J. Spirituality and religion in patients with HIV/AIDS. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:S5–S13. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Pargament KI, Boxer P, Tarakeshwar N. Religion as a source of stress, coping, and identity among Jewish adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2000;20:418–441. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Taylor RJ. Turning to prayer: Social and situational antecedents of religious coping among African Americans. Review of Religious Research. 1996;38:111–131. [Google Scholar]

- Emery EE, Pargament KI. The many faces of religious coping in late life: Conceptualization, measurement, and links to well-being. Aging International. 2004;29:3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fehring RJ, Miller JF, Shaw C. Spiritual well-being, religiosity, hope, depression, and other mood states in elderly people coping with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1997;24:663–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro KF, Koch JR. Religion and health among black and white adults: Examining social support and consolation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1994;33:362–375. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BR, Smith SL, Juarez G, Melancon C. Meaning of illness and spirituality in ovarian cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2003;30:249–257. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.249-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannelly LT, Flannelly KJ, Weaver AJ. Religious and spiritual variables in three major oncology nursing journals: 1990–1999. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2002;29:679–685. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.679-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall TL. Integrating religious resources within a general model of stress and coping: Long-term adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Religion and Health. 2000;64:65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing; 1967. The discovery of grounded theory. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson PD, Fogel J. Support networks used by African American breast cancer support group participants. Association of Black Nurses Forum Journal. 2003;14:95–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz E, Holt CL, Caplan L, Blake V, Southward P, Buckner A, Lawrence H. Role of spirituality in cancer coping among African Americans: A qualitative examination. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2008;2:104–115. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0050-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Stuetzle R, Fletcher MA. An increase in religiousness/spirituality occurs after HIV diagnosis and predicts slower disease progression over 4 years in people with HIV. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:S62–S68. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins RA, Pargament KI. Religion and spirituality as resources for coping with cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1995;13:51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KS, Elbert-Avila KI, Tulsky JA. The influence of spiritual beliefs and practices on the treatment preferences of African Americans: A review of the literature. Journal of the American Gerontological Society. 2005;53:711–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappeli S. Between suffering and redemption. Religious motives in Jewish and Christian cancer patients’ coping. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science. 2000;14:82–88. doi: 10.1080/02839310050162307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krefting L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1991;45:214–222. doi: 10.5014/ajot.45.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laubmeier KK, Zakowski SG, Bair JP. The role of spirituality in the psychological adjustment to cancer: A test of the transactional model of stress and coping. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;11:48–55. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1101_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Taylor RJ. Gender and age differences in religiosity among black Americans. Gerontologist. 1993;33:16–23. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Taylor RJ. Age differences in patterns and correlates of the frequency of prayer. Gerontologist. 1997;37:75–88. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Race and gender differences in religiosity among older adults: Findings from four national surveys. Journal of Gerontology. 1994;49:S137–S145. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln CE, Mamiya LH. The black church in the African American experience. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield CJ, Mitchell J, King DE. The doctor as God’s mechanic? Beliefs in the Southeastern United States. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;54:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattis JS. Religion and spirituality in the meaning-making and coping experiences of African American women: A qualitative analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2002;26:309–321. [Google Scholar]

- Moschella VD, Pressman KR, Pressman P, Weissman DE. The problem of theodicy and religious response to cancer. Journal of Religion and Health. 1997;36:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mytko JJ, Knight SJ. Body, mind and spirit: Towards the integration of religiosity and spirituality in cancer quality of life research. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:439–450. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<439::aid-pon421>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping: theory, research, and practice. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Kennell J, Hathaway W, Grevengoed N, Newman J, Jones W. Religion and the problem-solving process: Three styles of religious coping. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1988;27:90–104. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Poloma M, Tarakeshwar N. Spiritual healing, karma, and the bar mitzvah: Methods of coping from the religions of the world. In: Snyder CR, editor. Coping and copers: Adaptive Process and People. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Tarakeshwar N, Ellison CG, Wulff KM. Religious coping among the religious: The relationships between religious coping and well-being in a national sample of Presbyterian clergy, elders, and members. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2001;40:497–515. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Zinnbauer BJ, Scott AB, Butter EM, Zerowin J, Stanik P. Red flags and religious coping: Identifying some religious warning signs among people in crisis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59:1335–1350. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199801)54:1<77::aid-jclp9>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RE, Pargament KI, Lynn QK, Crossley CD. Self-directing religious coping: A deistic God, abandoning God, or no God at all? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2004;43:409–418. [Google Scholar]

- Powe BD. Perceptions of cancer fatalism among African Americans: the influence of education, income, and cancer knowledge. Journal of the National Black Nurses Association. 1994;7:41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringdal GI. Religiosity, quality of life, and survival in cancer patients. Social Indicators Research. 1996;38:193–211. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel K, Anderman SJ, Scrimshaw EW. Religion and coping with health-related stress. Psychology and Health. 2001;16:631–653. [Google Scholar]

- Stroman CA. Explaining illness to African Americans: Employing cultural concerns with strategies. In: Whaley BB, editor. Explaining illness: Research, theory, and strategies. LEA’s Communication Series. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Swensen CH, Fuller S, Clements R. Stage of religious faith and reactions to terminal cancer. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 1993;21:235–238. [Google Scholar]

- Tarakeshwar N, Pargament KI, Mahoney A. Initial development of a measure of religious coping among Hindus. Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:607–630. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ. Religion and religious observances. In: Jackson JS, Chatters LM, et al., editors. Aging in black America. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1993. pp. 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor EJ, Amenta M. Cancer nurses’ perspectives on spiritual care: Implications for pastoral care. The Journal of Pastoral Care. 1994;48:259–265. doi: 10.1177/002234099404800306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Church-based informal support among elderly blacks. Gerontologist. 1986;26:637–642. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Jayakody R, Levin JS. Black and white differences in religious participation: A multisample comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1996;35:403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor EJ, Outlaw FH, Bernardo TR, Roy A. Spiritual conflicts associated with praying about cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:386–394. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<386::aid-pon407>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ness PH, Kasl SV, Jones BA. Religion, race, and breast cancer survival. International Journal of Psychiatry and Medicine. 2003;33:357–375. doi: 10.2190/LRXP-6CCR-G728-MWYH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton J, Sullivan N. Men of prayer: Spirituality of men with prostate cancer: A grounded theory study. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2004;22:133–151. doi: 10.1177/0898010104264778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack B. Quality of life of long-term survivors of leukemia and lymphoma. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2000;18:39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer B, Pargament K, Cole B, Rye MS, Butter EM, Belavich TG, Hipp KM, Scott AB, Kadar JL. Religiousness and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzzy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1997;36:549–556. [Google Scholar]