Abstract

Introduction

This study used qualitative methods to examine whether, and if so how, African American cancer survivors use spirituality in coping with the disease. Spirituality was defined using a model involving connectedness to self, others, a higher power, and the world.

Methods

Twenty-three African American patients with various forms of cancer were recruited from physician offices and completed 1–1.5 h interviews. Data were coded by multiple coders using an inductive process and open-coding.

Results

Themes that emerged included, but were not limited to the aforementioned types of connectedness, one theme being connections to God. Given the important role of social support in the cancer experience, participants also emphasized their connectedness to others, which is in support of the spirituality model. Participants also articulated the notion that connections with others were not always positive, indicating that some perceived certain connections as having a detrimental impact on their well-being. Participants also expressed the desire to share their cancer story with others, often gained a new perspective on life, and obtained new self-understanding as a result of their illness experience.

Discussion/conclusions

Findings indicate that African Americans perceive that spirituality plays a strong role in their cancer coping and survivorship. Spirituality may address a human need for certitude in crisis. Further research is warranted for model testing, and to examine the role of spirituality in cancer coping among those of different backgrounds and cancer types/stages.

Implications for cancer survivors

These themes may have utility for the development of support interventions for cancer survivors.

Keywords: Spirituality, Coping, African Americans, Cancer survivorship, Narratives, Social support

Introduction

African Americans have the highest mortality rate for all cancer sites combined [1]. The mortality rate for all cancer sites for African American males is 1.4 times higher than for their White counterparts, while the mortality rate for African American females is 1.2 higher than for White females. Except for breast cancer in women, the incidence rates of the major cancers are also higher in African Americans than in Whites. [2]

Definition of spirituality

The current scholarly debate regarding definitions of “religiosity” and “spirituality” not withstanding [3], this paper will use the term spirituality. In general, religiosity entails structured worship and practice [4]. Religiosity also involves theological beliefs. Indeed, following the tradition of Thoresen [5], we define religion as “an organized system of beliefs, practices, rituals, and symbols.” The term spirituality is more elusive to operationalize than the term religiosity. It may include transcendent experiences and can include religion as well [4]. Spirituality has to do with “one’s transcendent relationship to some form of higher power” ([5], p. 415). In this paradigm, religiosity may be viewed as a component of spirituality, with spirituality referring to a broader concept than religiosity.

Based upon a literature review, Schulz [6] expanded upon Thoresen’s definition to include external expressions of an internal relationship with a higher power, and defined spirituality as “experiencing a meaningful connection to our core selves, others, the world, and/or a greater power, as expressed through our reflections, narratives, and actions” ([7] p.4). Schulz’s 3-Dimensional Model of Spirituality [7–9], which was used in this research, is based on that definition. The three dimensions of the model include: A vertical element involving connectedness to a higher power (God, beliefs and/or values); a horizontal element comprised of connectedness to self, others, and the world (including society, nature and the universe); and a temporal element encompassing the individual’s past, present, and future, as well as his/her place in history/culture.

Spirituality among African Americans

Spirituality is an important component of African American culture [10]. From an historical perspective, many African Americans coped with the experience of slavery by embracing Christianity and viewing Christ’s suffering as symbolic of their own [11]. For many African Americans, spirituality often facilitates in the process of creating and maintaining relationships with others [10]. Older African Americans use their spirituality to reframe remembered past experiences in a spiritual way [12].

Role of spirituality in cancer coping

The literature indicates that spiritual concerns are important to quality of life and health among cancer patients, and that spirituality facilitates cancer coping [13–14]. It has been suggested that spirituality be a focus of models addressing quality of life in oncology patients [15]. It also has been suggested that spirituality measures be included in studies examining quality of life, given the need to understand the role of body, mind, and spirit as well as the importance of spirituality in those diagnosed with cancer [13]. The spiritual needs of cancer patients often include finding meaning and hope, having access to spiritual resources [16], and drawing meaning from their suffering [17].

Mattis [18] used qualitative methods to examine the role of spirituality and religion in African American women coping with adversity. Findings analyzed within the context of meaning making indicated that participants viewed spirituality and religion as helping them to have a spiritual surrender, accept reality, grow as people, see their purpose and destiny, overcome limitations, learn life lessons, build character and act in accord with their moral values, and trust in a higher power. In a similar qualitative investigation, Walton and Sullivan [19] identified three spiritual themes among men coping with prostate cancer: prayer, coping with cancer and support.

Levine and colleagues [21] examined a multi-racial sample of women with breast cancer, and found that some women strengthened in faith while others began to question their faith. Simon and colleagues [20] conducted a qualitative study examining the role of spirituality in African American women with breast cancer. Upon initial diagnosis, spirituality was found to facilitate their acceptance, guide their decisions around treatment, and provide family support. During the treatment phase, spirituality aided them in coping with the effects of treatment and in finding meaning. Participants reported increases in spirituality and hope of survival. During posttreatment, spirituality gave participants a reason to survive, helped them to cope with the potential for cancer recurrence and helped them to adjust to treatment effects.

African American women with breast cancer reported that they used prayer when coping with their diagnosis [22]. They also experienced increased hope through their spirituality, and thus higher levels of psychological well-being [23]. African American men also coped with prostate cancer through spirituality [24]. Among patients with terminal cancer, those with advanced stages of faith experienced an increased quality of life relative to patients with less advanced stages of faith [25]. Persons with cancer diagnoses often experienced increases in the frequency of their prayer, church attendance, and faith [26], and their spirituality became more important to them as well [27]. They also reported the belief that although their suffering could not be comprehended or explained, God has a reason for it. In another cancer patient sample, prayer was used and found to be helpful; however, sometimes it resulted in unanswered prayers [28]. In a study of Southeastern participants, most reported that they believed that God works via doctors and also stated that they felt that spiritual issues would be more important than conversing with a physician if they were to become seriously ill [29].

Why is it important to know how spirituality relates to cancer coping?

The concept of cancer fatalism involves “the belief that death is inevitable when cancer is present” ([30], p.41). Powe [30] found that higher cancer fatalism is associated with lower levels of knowledge, education and income; and African Americans had higher scores for cancer fatalism than their White counterparts. Because of this notion of the uncontrollability of cancer, and the importance of spirituality in the African American community, spirituality may play an important role in assisting Africans Americans in coping with having a cancer diagnosis.

The literature suggests that there is a positive association between spirituality and cancer coping. It will be valuable to establish how spirituality relates to coping with cancer, as well as which aspects of it facilitate cancer coping. If more could be understood about the nature of the relationship between spirituality and cancer coping, we would be able to offer information to faith-based organizations or others providing support to cancer patients and thereby enhance their effectiveness. For example, suggesting to African Americans that they use their social support system, cognitive reframing or volunteering to help others with cancer may be a useful approach. Comparing such an approach with existing support programs on cancer survivorship using a controlled trial would help to establish this as an evidence-based method.

The present study

The present study used a qualitative approach to examine the specific nature of the relationship between spirituality and cancer coping among African Americans. It achieved this objective through the use of a semi-structured interview, in which interviewers asked a set of 26 pre-established questions. After each response provided by a participant for each question, the researcher followed up by asking further probing questions as needed to obtain comprehensive answers to the questions asked.

Method

Sampling and eligibility criteria

Half of all data collection was conducted at Morehouse School of Medicine (MSM) and half at University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). Patients were identified through several provider offices in which patients are seen for cancer treatment. Twenty-six patients were recruited through the provider offices using several methods: (1) providers mailed patients a letter describing the study, and interested patients called the study coordinator to learn more information; (2) providers posted recruitment fliers in their offices inviting patients to call the study coordinator for more information; (3) providers used a recruitment script to tell patients about the study and invite them to call the study coordinator for more information or to obtain their assent to be called by the study coordinator and be told more about the study. Eligible individuals, who were screened using a telephone script, were African Americans who had been diagnosed with cancer at least 6 months before but not more than five years before. Five years was used as the upper bound for time since diagnosis because after that, coping generally takes on a different level of relevance as patients are then generally considered “survivors.” Patients with any cancer except non-melanoma skin cancer were eligible; non-melanoma skin cancer was excluded because it is generally less severe and not life-threatening. Patients were not eligible until six months after diagnosis to allow for treatment and reasonable adjustment.

Interviewing and data collection

Data collection at the UAB site was conducted through the Recruitment and Retention Shared Facility and at the MSM site through the Clinical Research Center. These are units specializing in recruitment and data collection for medical research studies. All data collection was standardized between the two sites, including the two interviewers being trained together. Interested patients called the study coordinator at each site and were screened for eligibility. Interested, eligible patients made an appointment with study staff and were invited to come to UAB or MSM for the interview, or to be interviewed in the comfort and convenience of their own homes if they preferred (48% were home interviews). Forty-three percent of the interviews were conducted while the patient was at the medical center for an appointment.

Interviews began with written informed consent, and the document was summarized verbally for the participant, with time taken to ensure that the participant understood what participation would involve. The semi-structured interview began broadly by asking how the patient had been doing lately, and to go back to the time of diagnosis and retrace what the experience had been like. Information was solicited on what resources had been used in coping, with probes being given with specific regard to spirituality. Patients were first asked to define spirituality in their own words, and then to react to a definition of spirituality on a global scale that involved meaningful connections to self, others, God, and the world (based on Schulz, [7–9]), and then to discuss the role of each of these factors in their own individual coping with cancer.

Participants received an incentive in the amount of $25 for their participation. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed for analysis. Field notes were also taken by the interviewer. Interviewers were African American females, extensively trained in the interview protocol and in the sensitivity required for interviewing cancer patients about topics like coping and spirituality.

Qualitative data analysis

Because the purpose of the study was to explore the role of spirituality in cancer coping, an inductive process was used in the data analysis using an open coding method [31]. Though Schulz’s model [7–9] was used in the development of the interview guide and to conceptualize spirituality, no a priori framework was used in the identification of themes from the interviews. Interview tapes were transcribed verbatim. Data from three of the 11 tapes from MSM were inaudible and therefore could not be analyzed further. Because there was a strong preference among the project team for the analysis of verbatim transcripts as opposed to field notes, the patients who had been interviewed on these tapes were excluded from the analyses. The investigative team reviewed all transcripts noting themes and patterns which were then discussed at length leading to the development of a preliminary list of themes (codes). A codebook was developed after agreement was reached between researchers regarding the common dominant themes/codes, definitions of each code, criteria for inclusion and exclusion of each code, and example passages from interview transcripts illustrating the meaning of the codes. Two experienced coders (CH & ES) trained the other five members of the team to code by having them code a random sample of 10% of the dataset. The research team then split into pairs, each pair coding a portion of the dataset independently. One experienced coder (ES) worked on assignments with two different partners to balance the odd number of coders. Discrepancies within each pair of coders were resolved through discussion in a process of constant comparison [32]. Inter-rater reliability was calculated for each coded item through use of kappa statistics. Kappas ranged from 0.49–1.00 and were all p<0.001. Given that these themes are in their early stages of their development, these values indicate acceptable reliability [33]. Patterns of code usage were examined for each code. Member checking was done to increase the validity of the codes as applied to the data in the manner described below. After the initial coding process, participants were mailed a summary of the identified codes to make sure the codes correctly reflected their meaning [34]. No changes were made to the codebook or themes based on the feedback received from the member checking activity as the participants agreed with the team’s impressions and in some cases even provided additional elaboration to help corroborate.

Results

The 23 patients (15 from Alabama sample; eight from Georgia sample) ranged in age from 21 to 80, with a mean age of 59.19 years (SD=13.96; median age was 57.78). Fourteen (60.9%) were women and nine (39.1%) were men. One (4.3%) had completed elementary school, three (13.1%) had completed some high school, five (21.7%) had completed high school or obtained a GED, six (26.2%) attended one to three years of college or technical school, seven (30.4%) attended four or more years of college, and one (4.3%) did not answer the question. One (4.3%) was a member of an unmarried couple, two (8.7%) were never married, nine (39.3%) were married, three (13.1%) were separated, three (13.1%) were divorced, and five (21.7%) were widowed. Four (17.4%) were employed for wages, two (8.7%) were self-employed, one (4.3%) had been out of work for less than a year, one (4.3%) had been out of work for more than a year, one (4.3%) was a student, five (21.7%) were unable to work, and nine (39.1%) were retired. Six (26.1%) had an annual household income before taxes of under $10,000, four (17.4%) were in the 10,000–15,000 bracket, two (8.7%) were in the 15,000–20,000 bracket, two (8.7%) were in the 25,000–35,000 bracket, four (17.4%) were in the 35,000–50,000 bracket, two (8.7%) were in the 50,000–75,000 bracket, two (8.7%) were in the 75,000 or more bracket, and one (4.3%) indicated don’t know/not sure. Twenty-two (95.7%) had attended a place of worship within the past 12 months. Typical religious service attendance was four or more times per month for most, (15; 68.2%), though seven (31.8%) attended one to three times per month (one participant did not answer this question). Participation in religious activities such as Bible study or choir practice ranged from four or more times per month (12; 52.2%) to one to three times per month (five; 21.7%) to zero times per month (six; 26.1%). Twenty-two (95.7%) indicated that they were Christian, while one indicated not belonging to a religious group. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the participants across the two study sites.

Themes from semi-structured interviews

Six overall themes were gleaned from the interview data, with each theme having several sub-themes. The themes are as follows: ‘Definitions of Spirituality’, ‘Connections to Self’, ‘Connections to Others’, ‘Connections-Negative’, ‘Connections to the World’, and ‘Connections to God’. Illustrative quotes for the themes follow, grouped by code category.

Definitions of spirituality

When asked to define the term spirituality in their own words, some mentioned beliefs, the Holy Spirit, having a relationship with a higher power, clean living, having faith, treating others well, religion, and believing in something greater than oneself. When presented with a definition of spirituality based on Schulz’s 3-Dimensional Model of Spirituality [7–9] most participants agreed with the definition. Some had difficulty conceptualizing the definition of spirituality based on the model, and needed the interviewer to repeat the definition presented, AL female 4-year breast cancer survivor: “I don’t know. I agree with that statement. I don’t quite understand it but I agree with it.”; GA male 2.5-year prostate cancer survivor: “I hear you, but I don’t think I quite understand it.”. Some felt that the concept was difficult to put into words.

Belief and faith

With regard to the theme of spirituality involving belief and faith, one participant stated the following: AL male 3-year throat cancer survivor: “I guess I assume that you got to trust Him and believe in it, with all your heart, your mind, and your soul and that you know that He will heal your body…”; GA female 3-year breast cancer survivor: “There is a scripture that I use in Psalms, Renew my youth as an equal and every time I pray and God does it. If I believe it and I do believe it and he does it. He says according to your beliefs according to your faith renew onto you.”

Synonymous with religious beliefs

Other participants thought that spirituality was synonymous with religious beliefs. For example, one GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor stated: “I feel that this is a very good definition especially when you say through our core self, the spirit, the heart, and the soul because we are told that when you are going to be saved that if you believe and if thou shall confess with your mouth the Lord Jesus and believe in your heart that God raised Him from the dead, then thou shall be saved. It is with the heart that man is brought to righteousness and with the mouth confession is made into salvation.”

Involving the eternal

The notion that spirituality has to do with the eternal was brought forth by a GA male 2.5-year prostate cancer survivor: “Well I guess the only thing I can say on that is that I believe you have a body which houses a spirit which is your soul and those are two different entities. The body which houses the soul will wear out and die, but the spirit part will live forever.”

Relationship with God or spirit

Finally, participants also stated that spirituality has to do with a profound personal relationship with a greater power such as God or spirit. A GA male 5-year prostate cancer survivor said: “I believe it is true: spirit, heart, and soul. I believe in a meaningful connection with the spirit.” A GA female 3-year breast cancer survivor stated: “Well it is spiritually a connection of our own spirit and in our hearts with a greater power, the God Almighty. I’m gonna just say that a greater power, because a greater power to somebody else may be something else, but the greater power to me is what I have on my tag on my Jaguar: God All Mighty.”

Connections to God

Participants discussed their connection or relationship with God in a variety of ways. They indicated experiencing increased closeness with God and stressed the importance of having a relationship with God when coping. They also relied on and conversed with God and indicated a desire to seek God’s presence.

Relationship with God

Participants often reported that the experience with cancer had brought them closer to God, or strengthened their relationship with God. For example, as these participants stated, AL male 2-year lung cancer survivor: “Yeah, I feel closer to God, than I have in a long time.”; GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “I think it has brought me closer to God. I have always had a very good relationship with God, but I feel that I am even closer because I am forever thanking Him.”; GA female 3-year breast cancer survivor: “I am closer than ever with God. He is closer to me. I can hear him. I can hear him speak to me. I can hear his voice.”

The relationship with God is viewed as highly important in the coping process. As these participants explained, AL female 5-year ovarian cancer survivor:… “because like I say if you stay close to God, you know that burden of relief, you know what I mean and so I have seen people come in and there and they were oh, they were in terrible condition but like I say, I made it.”; GA male 5-year prostate cancer survivor: “It solidifies the fact that God is good. I put my faith in that. If God can bring me through the alcoholism and all that kind of stuff, I know I can make it through this.”; GA female 3-year breast cancer survivor: “I did not cry. When I got in the car I said God, I am not going to deal with this. You got this. I went on about my business getting home and did my regular routine and nobody questioned me. I just simply dismissed it and put it into God’s hands.”

Relying on and conversing with God

God was viewed as someone that the participants rely on and can talk to when nobody else is available, AL female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “I did not talk to nobody. Me and God had to talk and I felt good, I felt good.”; AL female 3-year cervical cancer survivor: “Yes, I sit and talk to Him just like I sit and talk to you, because I know that there is nobody in the room but me, but I, me and Him sit and talk just like me and you talk and I thank and I tell Him what I want and I say I know you are going to give it to me. And you are going to give it to me when you feel like it is to me for me to have it. God is the best friend that I got.”; GA male 5-year prostate cancer survivor: “I just rely on the Lord. My attitude about things today, and I know things happen in life and things are going to come to you, but if you just put your faith in the Lord and just lean on Him.”

Seeking God’s presence

For some participants, there was a desire to become closer and to know God better. As these participants stated, AL female 3-year breast cancer survivor:… “like I said, just being in here sometimes and, you know, being alone and just talking to God and seeking His presence basically and you can, I guess I can’t really explain it to you but if you have ever been in God’s presence you know it, you know it.”; GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “We will never be there until we get to heaven, but I feel that we can get closer to Him through the blood of Jesus Christ by his crucifixion.”

Connections to others

Participants also reported on meaningful, positive connections to others as being important in their coping experience. These others included family members, friends, the church family, other cancer patients, and the treatment team.

Family members

When discussing meaningful connections with family members, one participant, AL female 5-year ovarian cancer survivor, stated: “…my younger son I could talk to him and we were real close, you know”. Some reported that the cancer experience had brought them closer to family members, AL male 2.5-year lung cancer survivor: “My sisters and brothers once upon a time, when I was messing up they wouldn’t have much to do with me. But now they are right there any time I need them for their support…”; GA female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor: “I had support. Not a lot of family support, but I had my daughter. I had, as you guys are going to talk about later, spiritual support.”; GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “I prayed for him to allow me to take care of my grandchildren, which [NAME] at the time was only about 4 or 5 and she is now taking care of her child which is my great grand child.”; GA male 5-year prostate cancer survivor: “Knowing that my family is there for me…I have experienced a great connection with my children. And I have connected more with my children since I have experienced the cancer.”

Friends

Participants also described close relationships with friends. For example, one participant reported the following: AL male 2.5-year lung cancer survivor: “Well I still got a few friends that I am pretty close to, people they seem as though they sort of bond to me.” The same participant discussed positive changes in his relationship with his neighbors “… maybe the neighbors, some of the older people, that maybe used to hate to see me coming, all drunk up and crazy, you know they start to bond to me now, you know where I can sit down and talk to them on a good level head.”

The church family

Participants described close relationships with their church family, AL female 2.5-year breast cancer survivor: “…and when it was real bad and um my sisters and my brothers from church would come by.”; GA female 3-year breast cancer survivor: “My prayer partner is a nurse and she can handle the burden.”; GA male 2.5-year prostate cancer survivor: “There was a time when I went through stress, but through my minister, Rev. [NAME], he ministers strictly from the scripture, nothing made up from man’s mouth, to help me really understand the Lord and get introduced to the Lord, which I have done.”

Other cancer patients

The experience of meaningful connections with others may also include other cancer patients seen in treatment or elsewhere. For example, AL female 3-year breast cancer survivor, “…but um the other thing that I found like up in the chemotherapy area, it gets to be like a family environment because you see the same nurses and sometimes it depends on what time you come you can see the same patients, so it’s just really comical to me but we in America there are still racial problems and there is no need in telling that lie that there are not, but when you come to sickness, um, when you come to some common ground it’s just like color has no barrier and that’s kind of comical to me…”

The treatment team

Finally, participants discussed the close relationships they developed with the members of their treatment team: AL female 3-year breast cancer survivor, “Um, I have met several other patients that have been taking chemo, my doctors, all of my doctors, the people that work in the different offices when you go in, you form relationships with those people, that’s because you see them so often…”; GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “But anyway the nurse [NAME] was my guardian angel. She was so nice…[NAME] helped me to know what was going to happen to me.”

Connections to self

Many participants expressed experiencing a more meaningful connection to themselves in several ways, including increased self-understanding, becoming a better person, increased self-honesty, and increased self-love, as a result of their cancer.

Increased self-understanding

An example of increased self-understanding was described by several participants: AL female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor: “… the cancer itself, it helped me to get in touch with me…”; AL male 5-year head/neck cancer and Hodgkin’s disease survivor:

The connection that I had with myself was just understanding that there is a lot more to life than just living, you know. It just made me understand more that my life is what I make it. My life is what I make it. If I wake up everyday and do nothing but just go with some of my best friends and sit up at their house and drink beer and watch videos, that’s pretty much what I’m going to get for the rest of my life is waking up going to my friend’s house and watching videos twenty years later. But if I get up everyday and apply myself and go to work, finish college, make something out of myself, you know, do something to work towards, a dream. If I do one thing each day at the end of the year that’s three hundred sixty-five things I’ve done to work towards that one thing. If you do three hundred and sixty-five things to work towards your goal and nothing happens you need to change your goal.

Increased self-honesty/self-love

Honesty with self was another related theme as one participant illustrated, AL female 3-year breast cancer survivor, … “Just being honest with myself in that, you know, my body has changed since the surgeries and, you know, dealing with feeling different after chemo and things like that and looking different than I did before and so just coming to grips with that kind of stuff.” This quote also points towards the participant’s acceptance of the physical sequelae of her cancer. Other participants reported experiencing more self-love as a result of the illness. For example, one participant stated, AL female 3-year breast cancer survivor, … “It gave me; it made me care more about me. To take care, better care of me. I usually put everybody else first and not think about myself and love me more…”

Becoming a better person

Some participants felt that they had become better people through the process of cancer survivorship. For example, AL female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor, “We all have our, some character flaws or whatever, but, I try to make sure that the person I am, the person that I am becoming each day is a better person than I was yesterday.”; GA male 5-year prostate cancer survivor: “By being able not to judge and being able to accept whatever situation or circumstances of other people, regardless of their situations.”

New perspective

One theme, which indicated an increased connection to the self through an inner reflective process, is the theme of a new perspective. Participants reported gaining a new perspective from the cancer experience in several ways. Some simply indicated that they “look at things differently”. Others stated that they obtained a new perspective on life, experienced a change in priorities, or became a better person as a result of the cancer experience. Illustrative quotes of several types of new perspectives are described by participants follow.

New perspective on life

Going through cancer brought several participants a new perspective on life. These participants explained, AL male 2-year prostate cancer survivor, “A lot of things I looked at it one way and now that, that is, I found that the cancer is there it makes you look at things in a whole different perspective it puts things in a whole different perspective.”; GA female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor: “It has given me a more positive outlook. I encourage people.”; GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “…the Lord has given me the privilege to see things in a better light.”

Change in priorities/change for the better

Some participants reported that things that used to seem important were no longer important, and that their priorities had changed. For example, one participant stated, AL male 5-year head/neck cancer and Hodgkin’s disease survivor, “It made me have a more meaningful connection with myself, understanding that there is more to life than just living and I want this and I want that…it’s more to it than that…I mean I used to go to church every Sunday and I used to listen, but I never applied it to my life, until I had cancer.”

Finally, some participants even reported that they had changed for the better or in a more positive way as a result of the experience. These participants indicated, AL male 2.5-year lung cancer survivor, “I try to understand more people when they ask for a drink or can I have five dollars, I don’t just give them money, I give them something to eat.”; GA male 5-year prostate cancer survivor: “Something is different about life to me now. I am dealing with it positively actually. I feel that my heart is open and I am more connected to the world, more giving.”

Connections-negative

Importantly, the connections to others that participants described were not always positive in nature. Several participants noted that since their cancer experience, their relationships with others (spouse, family members, or friends) had become strained. It is interesting to note that this theme primarily came from male participant data.

Issues with spouse—stress

One person described feeling ongoing stress in his relationship with his wife, AL male 2.5-year lung cancer survivor, “…but my wife had stressed me out, I was taking so much medication I guess she always did have me stressed out, maybe that is where all that heavy drinking came from being stressed out trying to self medicate myself.” Another participant illustrates, GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor, “I know this is what happened to me over and over again, not just with illness, but when marriage problems come up. I have had quite a few. All I do is pray for that mountain to be removed and it does.”

Issues with family members—meddling

Another participant reported that although others were trying to help him, he did not like to be doted over and would have preferred to have been left alone or to have received a lower level of attention from his supporters. He stated, AL male 2-year lung cancer survivor, “… it seems as if they are picking they are meddling, you know and I don’t like that, you know, my auntie and my sister they act like I am in some kind of glass bubble or something, like if you bust it something is gonna happen and I tell them I got to just keep going on, you know, I can’t too much change my style. I mean I can’t do the things I used to as far as work around the house, you know, I can’t do that but they just seem they want to pamper me and I don’t like that.”

Issues with friends—abandonment

Finally, some reported that people whom they used to consider their friends had been scarce since the cancer experience, AL male 3-year head/neck cancer survivor, “I lost a lot of friends, so-called friends come to find out.” The same participant stated “I sit there I am by myself and all kinds of thoughts go through my mind, why don’t nobody want to be bothered with me, you know, I think about the times when I had more friends than I really wanted around, now they are gone. You know it’s the thoughts I don’t think nothing bad you know, I do tell myself I think the people are kind of wrong to do me the way they doing, they don’t come around no more.”

Connections to the world

There were several ways in which participants reported experiencing meaningful connections to the world, including helping others, giving to charity, volunteering, and giving others a better cancer experience.

Helping others

Participants indicated that as a result of going through cancer, they were more eager to help others. As these participants explained, AL male 5-year head/neck cancer and Hodgkin’s disease survivor, “Strangers, people that I know. I have heard the word from them that I am a good inspiration to them. I try to put a smile on somebody, laugh once a day.”; GA female 3.5-year breast cancer survivor: “I think it made me more of an advocate.”

Giving to charity/volunteering

Other participants reported an increased desire to give charity. As these participants stated, AL male 2.5-year lung cancer survivor, “… I’ve been giving more to charity, I see things, all different organizations on the street want you to give a donation and the schools and things like that and I have been participating in that more, you know, with a little gift, a small gift…”; GA male 5-year prostate cancer survivor: “I started dealing with a lot of the charities and fundraisers, people doing fundraisers for cancer. That is one that is really helping me deal with it. I am finding more out about it in other people and trying to help other women that do have breast cancer or find out they have it, trying to help them deal with it and cope with it in a positive way.”

Other participants mentioned one way they experienced meaningful connections to the world was by volunteering their time. As these participants explained, AL female 3-year breast cancer survivor, “…whatever I can do to help or offer and give back that may help someone else, you know, I try to do that. In going through the treatment I have participated in several studies and, you know, donated tissue for experiments and stuff like that, you know.”; GA female 2-year breast cancer survivor: “By sharing our loves, our smile, our money, and our talent with others.”

Giving others a better cancer experience

Participants were also interested in giving back so that someone else in their situation might have a better experience than they did. These participants stated, AL male 2-year lung cancer survivor, “I am going to treat it right and try to teach don’t do what I used to do.”; GA male 5-year prostate cancer survivor: “I had some experience with other women that were going through it and some of the problems they were having, I tried to use my spirit to help them get through their cancer experience.”

Share story

Another subtheme related to the ‘Connections with the World’ theme is the ‘Share Story’ subtheme. Participants recognized the importance of and held a desire to share their cancer story with others for two purposes. One purpose was to encourage others to engage in preventive health behaviors, and the other was to offer encouragement to others undergoing cancer treatment through telling their own cancer story.

Regarding offering encouragement to others to engage in preventive health behaviors through sharing one’s own cancer story, one participant stated, AL male 3-year throat cancer survivor, “… I am trying to tell people that, that maybe if you smoke, if you can stop you should, because it is not good for you and, you know, and any way that you can stop, stop because what I went through I don’t think that you want to go through it, you know if I can help it, so I try to tell people about that and what I went through on my experience with this cancer, if I had known 30 years ago, I never would have picked up the cigarette. I wouldn’t want to see a cigarette.”

Another reason participants shared their cancer story was to offer encouragement to others during their cancer treatment process. One participant said, AL male 5-year head/neck cancer and Hodgkin’s disease survivor, “… I’m just going through my experience that I went through, being that everyone has not went through what I went through, I feel I kinda got to share what I went through to other people to make them kinda see things different and maybe they can change for the better.”

Discussion

This current study offers a contribution to the existing body of knowledge on coping with serious illness. First, this work specifically addresses cancer survivorship and coping. Second, the priority population being studied is African American. Third, this work is aimed at identifying ways in which patients are using spirituality in cancer coping. Finally, these data hold potential for informing cancer support/survivorship interventions.

Findings from this study indicate that African Americans with cancer perceive that spirituality plays a strong role in their coping and survivorship. While a few of the participants did struggle with articulating a definition of spirituality, for the most part Schulz’s 3-dimensional model appears to be supported by the findings [7–9]. The concept that spirituality involves the eternal was brought to light when discussing the definition of spirituality. The idea of the eternal belongs in the vertical element of the model (connectedness to Greater Power)—in this case a person’s particular belief in the eternal spirit. The notion that a person is not his or her body but is actually an eternal spirit can be of great comfort to those facing a potentially fatal disease such as cancer, and personal mortality [35]. The vertical element of the model was also supported in the spirituality definition subthemes of belief and faith, religious beliefs, and connection to God or spirit. This emphasis on the importance of connection to a Greater Power (the vertical element of the model) was further underscored by the rich subthemes describing that relationship.

The horizontal element of Schulz’s model (connectedness to Self, Others, World, and Greater Power) [7–9] was also supported by the findings. Participants were able to describe connections to the self involving positive change, growth and a new perspective; connections to others as involving helpful and uplifting support from family, friends, church family, other patients and the treatment team; and connections to the world through volunteering—including sharing stories of their cancer experiences—and charity work. This giving back to others frequently involved the desire of patients to give back to others with cancer, doing anything they could to make someone else’s experience easier than what they went through.

Indeed, findings from this research suggest that African Americans coping with cancer may go through a spiritual process that is influenced by the experience of cancer. The spiritual process seems to involve experiencing increased closeness with God and significant others (family, friends, church family, other cancer patients, treatment team), while at the same time they experience some negative issues in relationships with others (stress, meddling, abandonment). Findings support the notion that adaptation to suffering via spirituality comes about by gaining a new perspective [7, 36], which is expressed through reflections and the sharing of one’s story (narratives), and from that new perspective, positive actions are taken to reach out to others and the world through volunteerism or donating to charity.

This study examined the role of spirituality in coping with cancer. The finding by Simon, et al. [20] that spirituality facilitated coping with cancer support the findings of this study. Their participants’ reports of increases in spirituality and of the role of the health care team as a spiritual resource were specifically echoed in our research. A recent study by Levine and colleagues [21] including African American women who had breast cancer revealed similar themes including deepening of faith, comforting presence of God, and acceptance; however different themes were also discussed involving questioning of faith and anger at God. It is possible that these differences were a result of their study including women of a variety of racial/ethnic groups while the present focused on African Americans. Is noteworthy that none of the participants in the present study voiced negativity regarding the role of spirituality in their cancer coping, and all felt that it played a significant role.

In a study of patients with cancer, HIV/AIDS, or myocardial infarction (63.3% White; 23.3% African American), the patients were asked to define spirituality and religiosity [37]. The patients defined spirituality as involving themes such as connection to God, connection to others, an individual orientation, and a way of relating to the universe, while religiosity was seen to involve themes such as rules or laws, rituals or traditions, community and fellowship, and people who share beliefs. Their definition of spirituality is very close to Schulz’s [7–9] definition of connectedness to a Greater Power, self, others, and the world, but does not include the expressiveness (reflections, narratives, and actions) aspect of the definition.

In a study of women with breast cancer, about half of whom were African American, both a self-forgiving attitude involving lack of guilt or regret for things one has done and spirituality were predictive of lower mood disturbance and higher quality of life [38]. The concept of self-forgiveness, while not specifically stated in our findings, may be related to the ‘connections to self’ theme of our research. The notion of lack of guilt or not having regrets, although not directly addressed in our findings, may be related to the theme of having a ‘new perspective’ through a reflective process after the cancer experience.

Finally, when people are faced with a failing body and failing medicines, sometimes the only thing left to turn to is the spiritual. There are various manifestations of a core human need that religion and spirituality serve, which is the quest for certitude or ultimate validation [39]. Ultimate invalidation would be the individual ceasing to exist at the time of death and ultimate validation or certitude would be the person experiencing eternal existence as is promised by our various religious beliefs [39]. The threat of ultimate invalidation with its associated uncertainty that is so frightening and as such religiosity and spirituality are tools to counter this. This may help explain why we often see spiritual concerns escalating during times of serious illness, such as cancer.

Limitations

Limitations of this research are several. First, the small sample size of 23 participants may not be representative of the larger population of all African American cancer patients. This research involved mainly Christian participants from the Southeastern United States, and thus findings may not be generalizable to other regions of the country nor to other religious backgrounds.

Future research

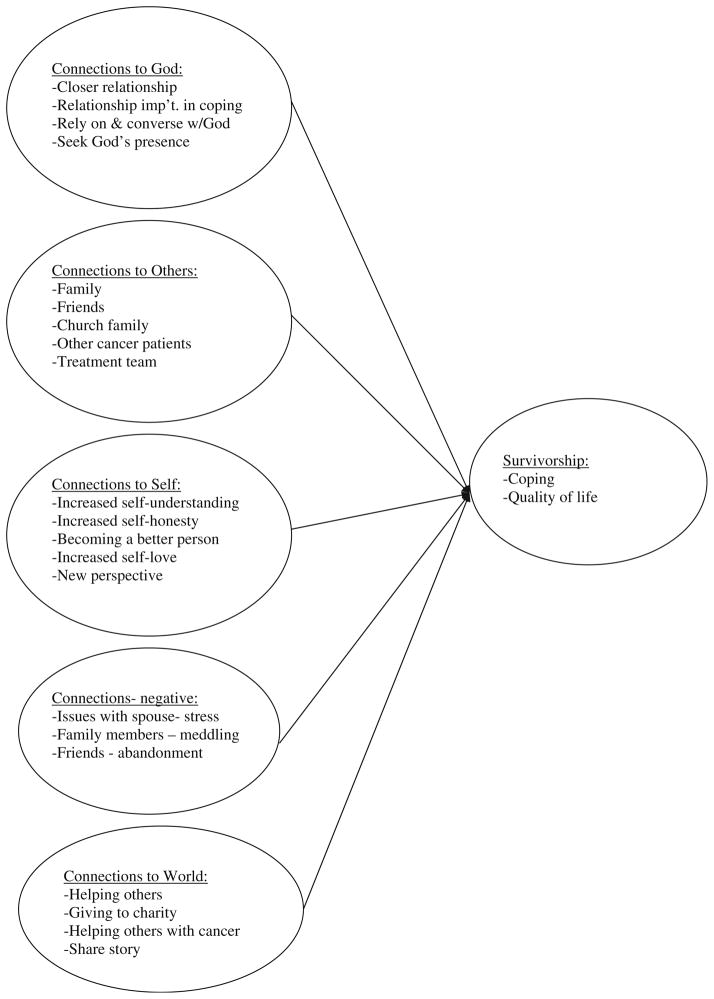

Further research is warranted regarding the role of spirituality and cancer coping among those from religious backgrounds (Jewish, Hindu, Buddhist, Islamic, no religious background, etc), as well as among those from other racial groups (Caucasians, Native Americans, Asian-Americans, Hispanic/Latinos, etc). Because several of our findings appeared to be gender-specific, a comparison of the role of spirituality in cancer coping between genders might also be useful. The role of spirituality in coping should also be explored by cancer stage, as the stage may influence the intensity of some participants’ spirituality. Finally, quantitative research should be done to further investigate the themes found in this study to determine if they are statistically associated with coping and quality of life (See Fig. 1). For example, a measurement tool could be developed to assess the thematic factors identified in this research, and models of spirituality and coping could be tested. Results could then be used to develop and offer support interventions to help cancer survivors cope with their disease.

FIGURE 1.

Theoretical model of spirituality, cancer coping, and quality of life.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank Drs. Mark Dransfield, Andres Forero, Sharon Spencer, and Helen Krontiras for their assistance with participant access and recruitment for this study, and Pat Jackson for her role in data collection.

This publication was supported by Grant Number (no. 1 U54 CA118948-01) from the National Cancer Institute, and was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board (no. X051004004).

Contributor Information

Emily Schulz, School of Medicine, Division of Preventive Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1717 11th Avenue South, Birmingham, AL 35294-4410, USA.

Cheryl L. Holt, Email: cholt@uab.edu, School of Medicine, Division of Preventive Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1717 11th Avenue South, Medical Towers Rm 641, Birmingham, AL 35294-4410, USA

Lee Caplan, Morehouse School of Medicine, Department of Community Health and Preventive Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Victor Blake, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Penny Southward, School of Medicine, Division of Preventive Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1717 11th Avenue South, Medical Towers Suite 415, Birmingham, AL 35294-4410, USA.

Ayanna Buckner, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Hope Lawrence, School of Medicine, Division of Preventive Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1717 11th Avenue South, Medical Towers, Birmingham, AL 35294-4410, USA.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures for African Americans 2005–2006. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2004. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zinnbauer B, et al. Religiousness and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzz. J Sci Study Relig. 1997;36:549–56. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenkins RA, Pargament KI. Religion and spirituality as resources for coping with cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1995;13 (102):51–74. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thoresen CE. Spirituality, health, and science: the coming revival? In: Roth-Roemer S, Kurpius SR, editors. The emerging role of counseling psychology in health care. New York: W. W. Norton; 1998. pp. 409–31. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulz EK. Spirituality and disability: a qualitative analysis of select themes. Occup Ther Health Care. 2004;18(4):57–83. doi: 10.1080/J003v18n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz EK. The meaning of spirituality in the lives and adaptation processes of individuals with disabilities. Denton, Texas: Texas Woman’s University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulz EK. Testing a spirituality model through measuring adolescent wellness outcomes. Denton, Texas: Texas Woman’s University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulz E. OT-Quest assessment. In: Hemphill-Pearson BJ, editor. Assessments in occupational therapy mental health: An integrative approach. 2. Thorofare, NJ: SLACK Incorporated; 2008. pp. 264–89. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattis JS, Jagers RJ. A relational framework for the study of religiosity and spirituality in the lives of African Americans. J Commun Psychol. 2001;29(5):519–39. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noel JA, Johnson MV. Psychological trauma, Christ’s passion, and the African American faith tradition. Pastor Psychol. 2005;53 (4):361–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas CL, Cohen HL. Understanding spiritual meaning making with older adults. J Theory Constr Test. 2006;10(2):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mytko JJ, Knight SJ. Body, mind and spirit: Towards the integration of religiosity and spirituality in cancer quality of life research. Psycho-Oncology. 1999 Sep-Oct;8(5):439–50. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<439::aid-pon421>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laubmeier KK, et al. The role of spirituality in the psychological adjustment to cancer: a test of the transactional model of stress and coping. Int J Behav Med. 2004;11(1):48–55. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1101_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brady MJ, et al. A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psycho-Oncology. 1999 Sep-Oct;8(5):417–28. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<417::aid-pon398>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moadel A, et al. Seeking meaning and hope: Self-reported spiritual and existential needs among an ethnically-diverse cancer patient population. Psycho-Oncology. 1999 Sep-Oct;8(5):378–85. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<378::aid-pon406>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kappeli S. Between suffering and redemption. Religious motives in Jewish and Christian cancer patients’ coping. Scand J Caring Sci. 2000;14(2):82–8. doi: 10.1080/02839310050162307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattis JS. Religion and spirituality in the meaning-making and coping experiences of African American women: A qualitative analysis. Psychol Women Q. 2002;26:309–21. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walton J, Sullivan N. Men of prayer: Spirituality of men with prostate cancer: A grounded theory study. J Holist Nurs. 2004;22:133–51. doi: 10.1177/0898010104264778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon CE, et al. The stage-specific role of spirituality among African American Christian women throughout the breast cancer experience. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2007;13:26–34. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine EG, Yoo G, Aviv C, Ewing C, Au A. Ethnicity and spirituality in breast cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2007;1:212–25. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0024-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson PD, Fogel J. Support networks used by African American breast cancer support group participants. Abnf J. 2003 Sep-Oct;14(5):95–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibson LM, Parker V. Inner resources as predictors of psychological well-being in middle-income African American breast cancer survivors. Cancer Control. 2003 Sep-Oct;10(5 Suppl):52–9. doi: 10.1177/107327480301005s08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowie J, et al. Spirituality and care of prostate cancer patients: a pilot study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003 Oct;95(10):951–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swensen CH, et al. Stage of religious faith and reactions to cancer. J Psychol Theol. 1993;21(3):238–45. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moschella VD, et al. The problem of theodicy and religious response to cancer. J Relig Health. 1997;36(1):17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner GB. Cancer recovery and the spirit. J Relig Health. 1999;38(1):27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor EJ, et al. Spiritual conflicts associated with praying about cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:386–94. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<386::aid-pon407>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansfield CJ, et al. The doctor as God’s mechanic? Beliefs in the Southeastern United States. Soc Sci Med. 2002 Feb;54(3):399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Powe BD. Perceptions of cancer fatalism among African Americans: The influence of education, income, and cancer knowledge. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 1995 Fall-Winter;7(2):41–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strauss A, Corbin J. Open coding. In: Strauss A, Corbin J, editors. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. London: Sage Publications; 1990. pp. 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glaser B, Strauss A. Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing; 1967. The discovery of grounded theory. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nunnaly JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krefting L. Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. Am J Occup Ther. 1991;45(3):214–22. doi: 10.5014/ajot.45.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levine S. Who dies? Baltimore, MD: Gateway; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schulz EK. The meaning of spirituality in the lives of individuals with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(21):1283–95. doi: 10.1080/09638280500076319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woods TE, Ironson GH. Religion and spirituality in the face of illness. J Health Psychol. 1999;4:393–412. doi: 10.1177/135910539900400308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romero C, et al. Self-forgiveness, spirituality, and psychosocial adjustment in women with breast cancer. J Behav Med. 2006;29:29–36. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9038-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baranson R. The secularization of American medicine. In: Lammers SE, Verhey A, editors. On moral medicine. 2. Grand Rapids, MI: William B Eerdmans pub co; 1998. pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar]