Abstract

In this study, an approach using influent COD/N ratio reduction was employed to improve process performance and nitrification efficiency in a membrane bioreactor (MBR). Besides sludge reduction, membrane fouling alleviation was observed during 330 d operation, which was attributed to the decreased production of soluble microbial products (SMP) and efficient carbon metabolism in the autotrophic nitrifying community. 454 high-throughput 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing revealed that the diversity of microbial sequences was mainly determined by the feed characteristics, and that microbes could derive energy by switching to a more autotrophic metabolism to resist the environmental stress. The enrichment of nitrifiers in an MBR with a low COD/N-ratio demonstrated that this condition stimulated nitrification, and that the community distribution of ammonia oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and nitrite oxidizing bacteria (NOB) resulted in faster nitrite uptake rates. Further, ammonia oxidation was the rate-limiting step during the full nitrification.

Introduction

Membrane bioreactor (MBR) technology is a reliable and promising process in wastewater treatment and reclamation owing to its distinctive advantages over conventional activated sludge (CAS) systems. Of particular significance is that the MBR systems avoid cell washout by retaining complete biomass, which favors the growth of autotrophic nitrifying bacteria and consequently increases the nitrification efficiency, as reported previously [1].

The nitrification pathway of ammonium removal in MBRs is a two-step reaction undertaken by ammonia oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and nitrite oxidizing bacteria (NOB): AOB oxidize ammonium to nitrite in the first step and then NOB oxidize nitrite to nitrate in the following step [2], [3]. Nitrifiers (AOB and NOB) are autotrophic bacteria and could derive energy for growth solely from the oxidation of ammonium/nitrite. However, in conventional MBRs, nitrification is not a strictly independent pathway and carbon oxidation is inevitable during this autotrophic process, which results in a bloom of heterotrophs. Even in an anoxic/oxic MBR, a considerable fraction of the organic carbon is still oxidized aerobically due to endogenous respiration of biomass as well as the leakage of organic carbon to aerobic tanks caused by the high recirculation flow [4], [5].

The unexpected heterotrophic metabolism under aerobic condition, on one hand, consumes a large quantity of influent organic carbon and oxygen. Huge amounts of waste activated sludges (WAS) are produced during this process and their microbial products have been verified as the active component causing membrane fouling in MBRs [6]. In addition, heterotrophs compete with nitrifying bacteria for oxygen and space [3], [7] and the accumulation of heterotrophic waste also inhibits the activities of the Nitrosomonas and the Nitrobacter group [8]. In the presence of organic carbon, nitrifiers are usually outcompeted by heterotrophs, which eventually cause the nitrification efficiency to decrease [9], [10]. Verhagen and Laanbroek [11] found that under such conditions the nitrifying bacteria were strongly reduced above the critical carbon-to-nitrogen ratios and the numbers of Nitrosomonas europaea decreased more than those of Nitrobacter winogradskyi.

In light of these findings, we explored a novel approach to improve the process performance and nitrification efficiency in an MBR. Since heterotrophs gain their energy primarily from organic carbon, it is possible to control heterotrophic metabolism by cutting down the external organic carbon supply or reducing the influent COD/N ratio [12], [13]. We hypothesized that operation in a low organic loading mode would result in nitrification stimulation, and that the metabolism (e.g. proliferation) of activated sludge would be altered in this mode, which would consequently influence the operation of MBRs (e.g., membrane fouling). To the best of our knowledge, the information of the effect of influent COD/N ratio on MBR performance and microbial community, especially as applied to low strength municipal wastewater treatment, is very limited.

Therefore, the overarching goal of this study was to evaluate the process performance and nitrification efficiency of an MBR fed with low COD/N-ratio municipal wastewater. 454 high-throughput pyrosequencing was then used to analyze the resulting bacterial population by sequencing the bacterial 16S rRNA gene, allowing us to investigate the population dynamics of the nitrifiers and heterotrophs in MBRs fed with different COD/N-ratio wastewater.

Materials and Methods

Lab-scale MBR: Configuration and Operating Conditions

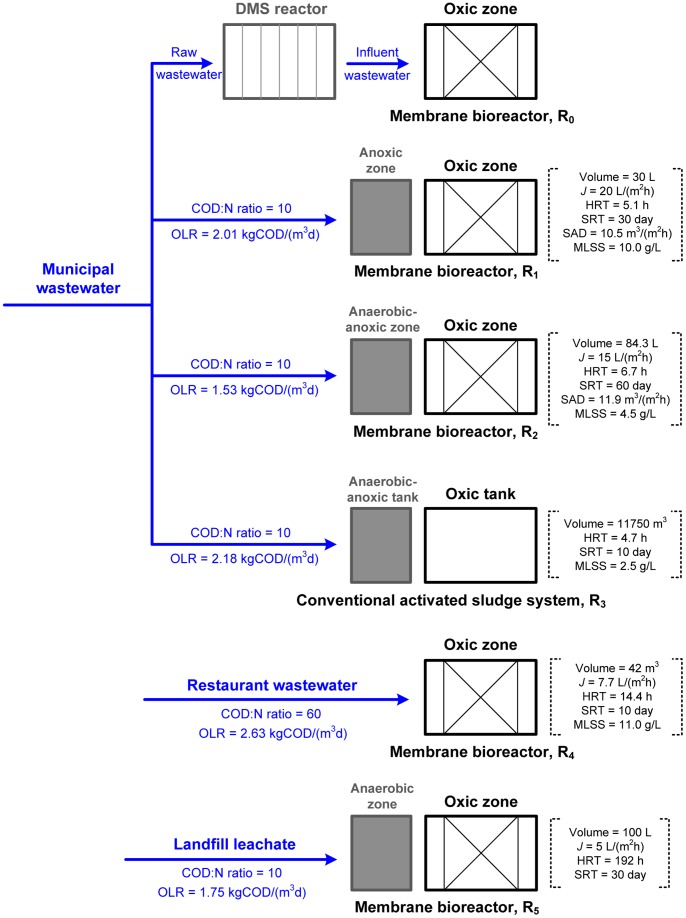

The lab-scale MBR (R0) consisted of a tank with an effective volume of 26 L (Figure S1 in Supporting Information). The influent came from a dynamic membrane separation (DMS) reactor (Figure 1). In our previous work, we have successfully decreased the COD/N ratio of raw wastewater through organic carbon recovery by the DMS reactor [14]. The characteristics of the wastewater are listed in Table 1. Two 40 cm×30 cm flat sheet membrane modules (PVDF, 0.40 µm, Kubota Corporation, Japan) were mounted vertically between two baffle plates located in the tank; the permeate flux (J) was set at 18–24 L/(m2·h).

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of R0 fed with low COD/N-ratio wastewater and control reactors (R1∼R5).

OLR, J, HRT, SRT and SAD represent organic loading rate, permeate flux, hydraulic retention time, and sludge retention time and specific aeration demand per unit projected area of riser zone, respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics of the raw, influent and treated wastewater (Unit: mg/L)a.

| Phase I | Phase II | Phase III | ||

| Raw wastewater | COD | 475.5±175.4 | 452.0±201.0 | 337.5±103.5 |

| TN | 44.7±10.5 | 41.5±11.3 | 43.5±7.3 | |

| Influent wastewater | COD | 66.5±23.8 | 57.3±18.8 | 75.2±27.8 |

| TN | 20.3±3.2 | 18.9±2.3 | 26.7±4.4 | |

| NH3-N | 17.4±5.2 | 16.2±3.2 | 24.5±4.9 | |

| Treated wastewater | COD | 14.3±14.9 | 8.8±5.6 | 17.0±10.0 |

| TN | 19.8±3.5 | 17.2±5.0 | 23.6±2.8 | |

| NH3-N | n.d.b | n.d. | n.d. |

Values are given as mean ± standard deviation and n = 18, 11, 13 for Phase I, Phase II and Phase III, respectively.

n.d.: not detectable.

The operation conditions of R0 are summarized in Table 2. Three phases with different hydraulic retention time (HRT) and sludge retention time (SRT) were performed to evaluate the reactor performance and to calculate the activated sludge yield coefficient (Y) under a low COD/N ratio. Over the 330 days’ operation, sludge was periodically wasted from the tank to maintain a SRT of 45 d in Phase I, 91 d in Phase II and 182 d in Phase III, respectively. The dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration of the tank was in the range of 1–3 mg/L. Details of the MBR configuration and operation can be found in Supporting Information (Text S1 and Figure S1).

Table 2. Operational conditions of R0 in three phases.

| COD/N ratio | ||||||

| Phase | J, L/(m2·h) | HRT, h | SRT, d | SAD, m3/(m2·h) | Raw wastewater | Influent wastewater |

| I | 18 | 4.6 | 45 | 10.5 | 10.8±4.3 | 3.3±1.0 |

| II | 24 | 3.4 | 91 | 14.3 | 11.3±5.3 | 3.1±1.0 |

| III | 24 | 3.4 | 182 | 14.3 | 7.8±1.8 | 3.0±0.6 |

For a full understanding of the microbial population dynamics resulting from influent COD/N variation, bacterial compositions in five control reactors (R1∼R5) were also evaluated in this study. The schematic diagram of the reactors can be found in Figure 1. R1 and R2 ran in parallel with R0, which were located in a municipal wastewater treatment plant (R3). R4 was constructed to treat high COD/N-ratio restaurant wastewater and R5 to treat landfill leachate. Membrane bioreactors (R1, R2, R4 and R5) were operated in a suction cycle of 10 min followed by 2 min relaxation to alleviate membrane biofouling and a chemical cleaning-in-place procedure (0.5% (v/w) NaClO solution, 2 h duration) was carried out if the trans-membrane pressure reached about 30 kPa during the operation. More information about the control reactors is available in our previous publications [6], [15], [16].

Calculation Procedures

The filtration resistance of R0 over time was calculated using the following equation according to the literature [17]:

| (1) |

where r t is the total filtration resistance (m−1), r c is the cake layer resistance (m−1), r p is the pore-clogging resistance (m−1), r m is the intrinsic membrane resistance (m−1), J is the permeate flux (m3/(m2·s)), and TMP is the applied transmembrane pressure (Pa), and μ is the permeate viscosity (Pa·s).

The sludge yield coefficient (Y, mgVSS/mgCOD) and decay coefficient (K d, day−1) in R0 were estimated from the material balance of substrate and biomass, according to the following equation:

| (2) |

where N rs is sludge loading rate (kgCOD/(kgMLVSS·d)), T is the temperature (°C), and Y′ and y (or K d ′ and k) are the Arrhenius constant and exponent of Y (or K d), respectively. Y and K d values for conventional MBRs were determined according to the MBR book [18] and our previous studies.

Biokinetics of microbial activities in R0 inferred from ammonia, nitrite and acetate oxidation were estimated via extant respirometry. Specific oxygen uptake rates (SOURA) and specific ammonia uptake rates (SAUR) related to AOB, SOURN and specific nitrite uptake rates (SNUR) related to NOB, and SOURH related to heterotrophs at different temperatures were measured separately using batch assays [19]. Specific nitrification rate (SNR) was determined by the limiting rate of SAUR or SNUR. The detailed measurement and calculation procedures are shown in Supporting Information (Text S1 and Table S1).

Microbial Diversity Analysis

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

Samples for pyrosequencing were obtained from oxic zones of the reactors (R0∼R5) in August, 2011 and water temperature was about 27°C. R0 was operated in Phase I with SRT of 45 d and HRT of 4.6 h. All sludge samples were settled and concentrated onsite and immediately transported to the laboratory for further treatment. DNA extraction was processed using the FastDNA® SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocols. The quantity and quality of the extracted DNA were assessed using a Nano-drop® ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Labtech International, UK). For genetic library construction, DNA from the 5 MBRs (R0, R1, R2, R4 and R5), and from R3, were each amplified by PCR using primer set 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 533R (5′-TTACCGCGGCTGCTGGCAC-3′) for the V1-V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene. The 20 µL PCR mixture contained 4 µL of 5×FastPfu Buffer, 2 µL of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.4 µL of each primer (5 µM), 0.5 µL of DNA and 0.4 µL FastPfu Polymerase. The thermocycling steps were as follows: 95°C for 2 min, followed by 25 cycles at 95°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. The fused forward primer includes a 10-nucleotide barcode inserted between the Life Sciences primer A and the 27F primer. The barcodes allowed sample multiplexing during pyrosequencing in a single 454 GS-FLX run.

454 high-throughput 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing

After purification using the UNIQ-10 PCR Purification Kit (Sangon, Shanghai, China) and quantification using a TBS-380 (Turner BioSystems, Inc., USA), a mixture of amplicons was used for pyrosequencing on a Roche massively parallel 454 GS-FLX Titanium sequencer (Roche 454 Life Sciences, Branford, CT, USA) according to standard protocols [20]. To minimize the effects of random sequencing error, low-quality sequences were removed by eliminating those without an exact match to the forward primer, those without a recognizable reverse primer, those with length shorter than 150 bp, and those containing any ambiguous base calls (Ns) [21]. Barcodes and primers were then trimmed from the resulting sequences. Pyrosequencing produced 7818 (R0), 6629 (R1), 7429 (R2), 8265 (R3), 9854 (R4) and 7944 (R5) high-quality V1-V3 tags of the 16S rRNA-gene with an average length of 419 bp.

Biodiversity analysis and phylogenetic classification

Initially, sequences were analyzed by performing a BLAST search via the silva106 database at a uniform length of 150 bp and then clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) by setting a 0.03 or 0.05 distance limit (equivalent to 97% or 95% similarity) using the MOTHUR program (http://www.mothur.org/wiki/Main_Page). From the cluster file, the rarefaction curves at α of 0.03, 0.05 and 0.10 were generated in MOTHUR for each sample. Taxonomic classification down to the phylum, class, order, and family and genus level was performed using MOTHUR via the silva106 database at a uniform sequence length of 400 bp with a set confidence threshold of 80%. Hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using the gplots package of R (http://www.r-project.org/) in Linux. The Chao linkage method was employed for distance calculation and the complete linkage method for cluster analysis in both coltree and rowtree of heatmap. MEGAN 4.0 software (http://ab.inf.uni-tuebingen.de/software/megan/) was then used to interactively explore the dataset. Each node is labeled by a taxon and the number of reads assigned to the taxon, and the size of a node (the pie chart) is scaled logarithmically to represent the number of assigned reads.

Analytical Measurements

Analytical measurements of chemical oxygen demand (COD), ammonium (NH3-N) and total nitrogen (TN) in raw, influent and treated wastewater, total mixed liquor suspended solids (MLSS), and mixed liquor volatile suspended solids (MLVSS) in the system were performed according to the Standard Methods [22]. Protein was measured by the modified Lowry method using bovine serum albumin (BSA) protein as a standard [23]. Carbohydrate was measured according to the phenol-sulfuric acid method with glucose as a standard [24]. TOC and UV254 of the filtrate of mixed liquor was quantified by a TOC analyzer (TOC-VCPN, Shimadzu, Japan) and 2802 UV/VIS spectrophotometer (Unico Inc., USA), respectively. Dissolved oxygen (DO) and temperature were monitored by using a DO meter HQ30d with probe LDO10103 (Hach Co., USA) online. Moreover, microscopic examination of the mixed liquor sample was performed according to the protocols [15] twice a week. Aquatic worms’ bloom was defined as the sharp decrease of biomass concentration with the presence of >1000 metazoans per L mixed liquor.

Results and Discussion

Process Performance

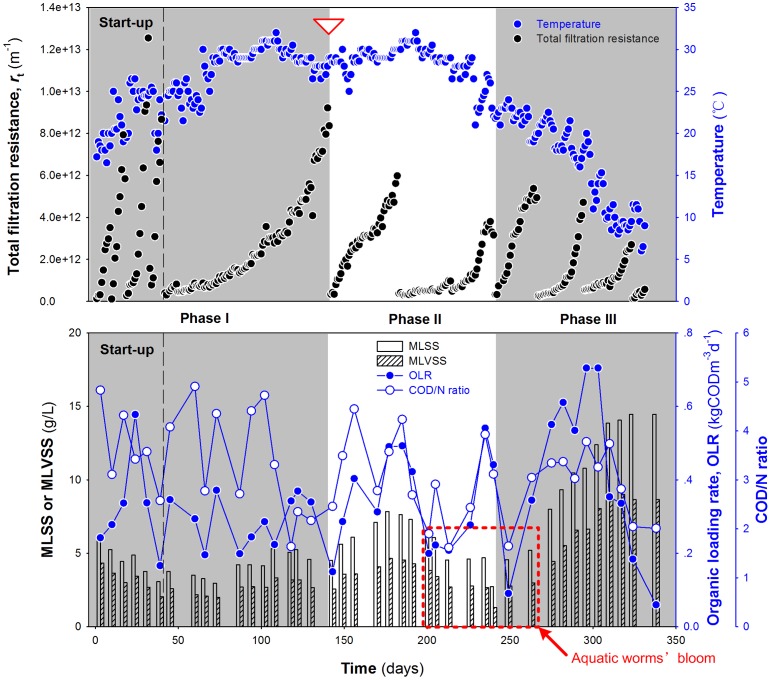

At the beginning of the experimental runs, a period of time intended for biomass acclimation (designated as start-up phase in Phase I) was imposed on R0. The stable biomass concentration of 4.66±0.48 g MLSS/L, 7.09±0.67 g MLSS/L and 14.60±0.59 g MLSS/L was achieved in Phase I, Phase II and Phase III, respectively (Figure 2). Since a large fraction of influent organic carbon was recovered in the upstream process (Table 1), WAS production involved in the treatment of per ton wastewater was decreased by 60–80%. Moreover, with the feeding strategy adopted, in which a low organic loading rate (OLR) was applied to favor the growth of autotrophic microorganisms, it was inferred that a low COD/N ratio would cause a limiting supply of nutrients for microorganism growth, and could result in a low sludge yield. Relevant literature has documented that an autotrophic community could derive energy for growth from the oxidation of ammonium/nitrite [25], resulting in a thinner microcolony structure in bioreactors [7], [13]. In view of this, we calculated the sludge yield coefficient (Y) and decay coefficient (K d) to evaluate the carbon metabolism in R0. Y and K d refer to microorganism growth and endogenous respiration. OriginPro 8 (OriginLab Corporation, USA) was applied to process the nonlinear curve fit and the results are shown in Figure S2.

Figure 2. Variations in r t, biomass concentration, OLR and COD/N ratio during R0 operation.

(The inverted open triangle indicates the time point of sludge sampling).

In this study, the kinetic parameters were calculated as Y = 0.362e0.001T mg VSS/mg COD and K d = 0.023e0.006T day−1 using the operational data, and these constants at 20°C were lower than those of conventional MBRs (0.56–0.40 mg VSS/mg COD and 0.08–0.07 day−1). This result indicated a limited rate of microorganism growth and biomass decay in a relatively autotrophic run [26]. Under such an oligotrophic environment, organic carbon was likely to be taken up by the starved community to derive energy for system sustainability rather than assimilated for microbial growth, and the significantly decreased K d is likely due to the lower aeration intensity [27], [28]. In summary, we preliminarily concluded that the sludge reduction in R0 was a result of both source reduction (influent organic carbon) and process reduction (bio-metabolism pathways).

The variations of the total filtration resistance with operation time in the three phases of R0 are also shown in Figure 2. After a successful acclimation in the start-up phase, the reactor operation was gradually stabilized with a relatively low rate of increase of r t. The operation cycles in Phases I and II of R0 lasted for about 100 and 60 days, respectively, relatively longer than that in our previous study [15], [16]. Even if the low liquor temperature (5–15°C) caused membrane filtration to deteriorate by the Phase III, the chemical cleaning cycle was still about 30 day. To clarify the mechanism of alleviation of membrane fouling in R0, the average content of TOC, protein, carbohydrate and UV254, representing dissolved organic matter (DOM) in the supernatant of the mixed liquor, was quantified as 9.40±2.91 mg/L, 11.49±1.11 mg/L, 10.11±3.09 mg/L and 0.090±0.003, respectively (n = 7). The DOM level was relatively lower than that of conventional MBRs [6], [15], [16], which presumably mitigated cake layer (or gel layer) formation and pore clogging during membrane filtration. To explain our result, we hypothesize a combined metabolic synergy, i.e., in addition to the decreased production of soluble microbial products (SMP) mentioned above, it is likely that there was an efficient food web (carbon metabolism) in the autotrophic nitrifying community, which ensured maximum heterotrophic utilization of SMP produced by nitrifiers and prevented significant accumulation of nitrifier waste materials, as reported by Kindaichi et al. [9]. In future, further attempts will be made to clarify the principle of SMP production and degradation during autotrophic nitrification in an MBR, and its impact on fouling and membrane filtration.

Biokinetics of Nitrifiers and Heterotrophs

Table 1 summarizes the average characteristics of the influent and treated wastewater in R0. Ammonium could not be detected in the treated water during the experimental operation. In three phases, ammonium was predominately oxidized to nitrate (99.8±0.1%, n = 42) rather than nitrite (0.2±0.1%, n = 42). The negligible nitrite accumulation (<0.04 mg NO2 −N/(gVSS·h)) during the full-scale nitrification decreased the risk of NO2 − reduction or its chemical decomposition, which subsequently reduced the transient and stabilized N2O and NO emissions, as documented previously [2], [19].

SOURH, SOURA and SOURN of the biomass in R0 were calculated as 3.91, 1.71 and 4.64 mgO2/(gVSS·h) (R2 = 0.9985, 0.9994 and 0.9963) at 19.8°C, and 8.47, 2.96 and 8.89 mgO2/(g VSS·h) (R2 = 0.9922, 0.9960 and 0.9896) at 23.7°C, respectively. The biokinetics of nitrite to nitrate oxidation were significantly (α = 0.05) higher than the biokinetics of ammonium to nitrite oxidation, illustrating that ammonia oxidation limited the full-nitrification. SNR was then determined as SAUR. It has been reported that with the SRT prolonged, biomass renovation became slower and enzymatic activity (e.g., SNR) decreased due to competition from the biomass derived from the limiting supply of nutrients [28], while the SNR in R0 was calculated as 18.9e0.059T mgN/(gVSS·d) (R2 = 0.8370), even higher than that of the conventional MBRs with shorter SRTs [26], [29]. Thus it is possible that the decrease in the influent COD/N ratio inhibited the metabolism of heterotrophs, thereby favoring the nitrifiers in competing for oxygen and scarce substrate (SOURA+ SOURN>SOURH) [11], especially under prolonged SRT conditions.

Further investigation using 454 high-throughput 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing was performed to compare the microbial diversity and composition (heterotrophs and nitrifiers) of bioreactors fed with different COD/N-ratio wastewater.

Taxonomic Complexity of the Bacterial Community

Six 16S rRNA gene libraries were constructed from pyrosequencing of R0, R1, R2, R3, R4 and R5 communities with 7818, 6629, 7429, 8265, 9854 and 7944 high-quality reads (average length of 419 bp). The number of sequences was comparable to our previous study [20]. The MOTHUR program was first used to assign these sequence tags into different phylogenetic bacterial taxa and we obtained 1230 (R0), 1335 (R1), 1668 (R2), 1534 (R3), 1173 (R4) and 781 (R5) OTUs at a 3% distance. From the cluster file, the rarefaction curves at α of 0.03, 0.05 and 0.10 were generated in MOTHUR for each sample (Figure S3). By comparing the curvature of rarefaction curves, the increase of COD/N ratio from 3.0 to 10.0 (R0 vs R1, R2 and R3) resulted in the proliferation of the overall bacterial communities, likely due to heterotroph enrichment. The difference in community structures did not actually influence the bioreactor performance with regard to contaminant removal (Table 1), probably due to species functional redundancy [2], [28], i.e functional redundancy appears to be a mechanism for increasing community robustness or responding to changing environments. With the COD/N ratio further increased from 10.0 to 60.5 (R1, R2 and R3 vs R4), the diversity of the overall bacterial communities was decreased, as observed elsewhere [11], due to the washout of autotrophs. The microbial diversity of biomass in R5 was significantly lower, likely in part due to the toxic and high-salty character of its feedwater.

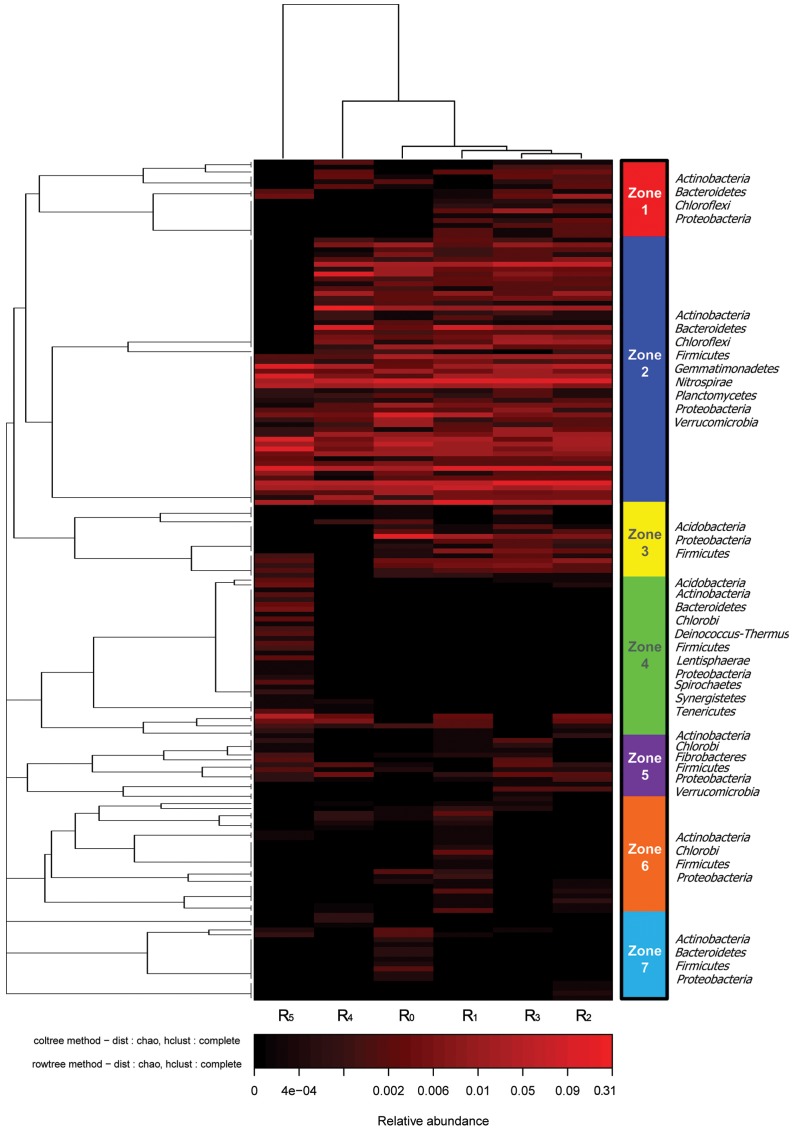

Comparative Analysis of Bacterial Communities

In order to further compare the population dynamics of heterotrophs, AOB, and NOB with COD/N ratio variations, hierarchical cluster analysis and bacterial taxonomic identification were conducted to illustrate the differences of the six bacterial community structures. In this study, the 174 most abundant OTUs were assigned into seven zones (Z1–Z7) according to the phylogenetic relationship, and taxonomic complexity of the zones is shown in Figure 3. It could be observed that three clusters were identified from the six bacterial communities by hierarchical cluster analysis: Cluster I (R0, R1, R2 and R3), Cluster II (R4) and Cluster III (R5). The microbial community structures in Cluster I (R0, R1, R2 and R3) exhibited high homology, especially in Z2–Z4 (Figure 3), and R5 was separated from Cluster I and R4, having only 0.04% similarity. These results show that sequence homology was mainly determined by feed characteristics (e.g. COD/N ratio and organic substrate composition), and particular bacteria were selectively enriched in their individual bioreactors.

Figure 3. Hierarchical cluster analysis of R0–R5 bacterial communities.

The y-axis is the clustering of the 174 most abundant OTUs (3% distance) in reads. The OTUs were divided into seven zones (Z1–Z7). Sample communities were clustered based on complete linkage method. The color intensity of scale indicates relative abundance of each OTU read. Relative abundance was defined as the number of sequences affiliated with that OTU divided by the total number of sequences per sample.

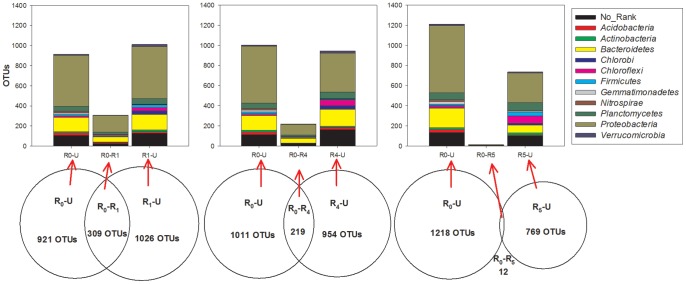

In contrast to the typical heterotrophic environment, a shift of an MBR from a copiotrophic (e.g. R1) to an oligotrophic environment (R0) did not increase the diversity of the community, although nitrification stimulation was observed [21]. However, the microbes present in an MBR could derive energy by switching to a more autotrophic metabolism to resist the environmental stress [25]. The total observed OTUs in the R0 and R1 communities was 2256, with 309 OTUs, or 13.7% of the total, shared by them (Figure 4). Of the 18 identified phyla, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and No_Rank bacteria accounted for the majority of the unique community composition in R0 (55.0%, 15.2% and 11.7%) and R1 (50.4%, 14.9% and 12.6%), respectively. Notably, although the organic matter in the influent of R0 was lower, the heterotrophic bacteria were still dominant over the autotrophic bacteria, as documented previously [31]. Despite the fact that the population composition of R0–U, R0–R1 and R1–U were not significantly different at the 0.05 level (p = 0.99985), a marked decrease in the phototropic bacteria in R0 was observed compared with R1, suggesting more favorable conditions for the growth of the nitrifiers (Figure 4). By contrast, the shared OTUs ratio with R0 was decreased by 27.0% with the influent COD/N-ratio increased from 10.0±4.2 (R1) to 60.5±13.9 (R4). The clearest difference between the unique communities of R0 and R4 was the different distribution of phyla Proteobacteria, Chlorobi, Chloroflexi and Nitrospirae in Z2, Z3 and Z5 in Figure 3. Autotrophic bacteria in phyla Proteobacteria and Nitrospirae may be depleted in R4 under such a copiotrophic environment. Although the influent COD/N ratio was also about 10 in R5, its community structure was quite different from the other MBRs’ (Figure 3). Racz has reported that not only the quantity but also the source of the organic carbon affected the make-up of the heterotroph community as well as AOB in mixed cultures [3]. The phyla Chloroflexi (9.5%), Firmicutes (4.4%) and Planctomycetes (10.5%) referring to polysaccharide degradation [32], anaerobic fermentation [21] and sulfated polymeric carbon utilization in the marine environment [33] were enriched in the R5 community (Figure 4), suggesting a versatile bio-metabolism of the inert component in the leachate.

Figure 4. Venn of the bacterial communities of R0 vs R1, R0 vs R4 and R0 vs R5 based on OTU (3% distance), and the taxonomic identities of the shared and unique OTUs at the phylum level (Phyla percentages below 1.0% are not shown).

R0–U, R1–U, R4–U and R5–U represent the unique R0, R1, R4 and R5 communities, and R0–R1, R0–R4 and R0–R5 refer to shared communities.

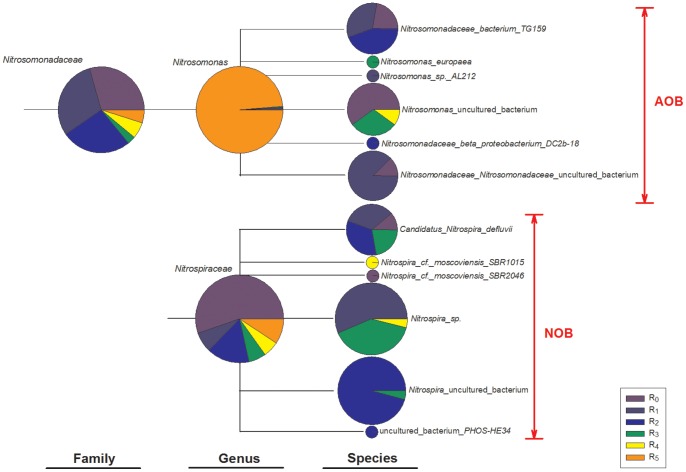

Specific comparison of nitrifier communities was conducted using the MEGAN 4.0 software (Figure 5). The ratio of spectrum color in each pie represents the ratio of the relative abundance of reads assigned to the corresponding family, genus or species in R0–R5. The reads present in the node of one taxon are not assigned to its descendants any more, i.e., these reads are unclassified to the down nodes in the taxonomy. As shown in Figure 5, the dominant AOB species was Nitrosomonas and the dominant NOB species was Nitrospira, belonging to the orders Nitrosomonadales and Nitrospirales, respectively. These results are consistent with previous literature characterizing activated sludge systems [3], [31]. From an ecological perspective, then, AOB with a lower half-saturation coefficient for ammonia can thus be enriched in environments such as the full nitrification reactor described here, and the lack of detection of Nitrobacter spp.-related NOB was likely due to the propensity of Nitrospira spp. to preferentially grow at lower nitrite concentrations [2], [30].

Figure 5. AOB and NOB sequences from R0–R5 assigned to NCBI taxonomies using BLAST and MEGAN.

In general, the AOB and NOB were more abundant in MBRs than those in the CAS (R3) system (p<0.01), which suggests that the complete biomass retention of microfiltration favored the nitrifiers with low growth rate and poor growth yield. With the influent COD/N ratio decreased from 10.0 (R1 and R2) to 3.0 (R0), the population of AOB and NOB was increased by 4.7% and 189.3%. The community distribution of AOB (155 OTUs) and NOB (353 OTUs) in R0 resulted in faster nitrite uptake rates and a rate-limiting step of ammonia oxidation during the nitrification. Under a high organic substrate concentration (R4), the nitrifiers were outcompeted by the heterotrophs and thus only 31 OTUs of AOB and 41 OTUs of NOB were detected at a 3% distance, which indicated a deterioration of nitrification. In R5, the influent organic carbon contained a large fraction of complex protein-like substances (data not shown), and Nitrosomonas referring to AOB were highly enriched while NOB species (Nitrospira) decreased. This result is consistent with a previous report that the protein-like organic substrate facilitates the growth of AOB [3].

Conclusions

Sludge reduction and membrane fouling alleviation were induced by the decrease of influent COD/N-ratio. The reduced SMP production and efficient carbon metabolism in the autotrophic nitrifying community facilitated membrane fouling mitigation. The diversity of microbial sequences was mainly determined by feed characteristics, and with a lower COD/N ratio, microbes could derive energy by switching to a more autotrophic metabolism to resist the environmental stress. The enrichment of nitrifiers in the low COD/N-ratio MBR stimulated nitrification, and the community distribution of AOB and NOB resulted in faster nitrite uptake rates and a limiting-rate step of ammonia oxidation during the full-scale nitrification. The results obtained from this study may indicate that decreasing influent COD/N ratio of MBRs (e.g. recovering organic matter from the influent) should be a promising means to improve nitrification efficiency and to alleviate membrane fouling.

Supporting Information

Schematic of R0 fed with low COD/N-ratio municipal wastewater.

(TIF)

Nonlinear curve fit of Y and K d, and analysis of variance (ANOVA).

(TIF)

Rarefaction curves of OTUs defined by 3%, 5% and 10% distances in R0–R5 sludge samples.

(TIF)

Substrate composition for SOURs.

(DOCX)

More information on MBR configuration/operation and SOUR/SAUR/SNUR determination.

(DOCX)

Funding Statement

This work was financially supported by the Sino-French Scientific and Technological Cooperation Project in the Domain of Water (2011DFA90400), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 51008217) and by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Hocaoglu SM, Insel G, Cokgor EU, Orhon D (2011) Effect of sludge age on simultaneous nitrification and denitrification in membrane bioreactor. Bioresource Technology 102: 6665–6672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahn JH, Kwan T, Chandran K (2011) Comparison of Partial and Full Nitrification Processes Applied for Treating High-Strength Nitrogen Wastewaters: Microbial Ecology through Nitrous Oxide Production. Environmental Science & Technology 45: 2734–2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Racz L, Datta T, Goel R (2010) Effect of organic carbon on ammonia oxidizing bacteria in a mixed culture. Bioresource Technology 101: 6454–6460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Virdis B, Rabaey K, Yuan ZG, Keller J (2008) Microbial fuel cells for simultaneous carbon and nitrogen removal. Water Research 42: 3013–3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan Z, Keller J, Lant P (2003) Optimization and control of nitrogen removal activated sludge processes: a review of recent developments. In: Agathos, S.N., Reineke, W. (Eds.), Biotechnology for the Environment: Wastewater Treatment and Modeling, Waste Gas Handling, vol. 3C, 187–227.

- 6. Wang ZW, Wu ZC (2009) Distribution and transformation of molecular weight of organic matters in membrane bioreactor and conventional activated sludge process. Chemical Engineering Journal 150: 396–402. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bassin JP, Kleerebezem R, Rosado AS, van Loosdrecht MCM, Dezotti M (2012) Effect of Different Operational Conditions on Biofilm Development, Nitrification, and Nitrifying Microbial Population in Moving-Bed Biofilm Reactors. Environmental Science & Technology 46: 1546–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li F, Chen JH, Deng CH (2006) The kinetics of crossflow dynamic membrane bioreactor. Water SA 32: 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kindaichi T, Ito T, Okabe S (2004) Ecophysiological interaction between nitrifying bacteria and heterotrophic bacteria in autotrophic nitrifying biofilms as determined by microautoradiography- fluorescence in situ hybridization. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 70: 1641–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee LY, Ong SL, Ng WJ (2004) Biofilm morphology and nitrification activities: recovery of nitrifying biofilm particles covered with heterotrophic outgrowth. Bioresource Technology 95: 209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Verhagen FJ, Laanbroek HJ (1991) Competition for Ammonium between Nitrifying and Heterotrophic Bacteria in Dual Energy-Limited Chemostats. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 57: 3255–3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nogueira R, Melo LF, Purkhold U, Wuertz S, Wagner M (2002) Nitrifying and heterotrophic population dynamics in biofilm reactors: effects of hydraulic retention time and the presence of organic carbon. Water Research 36: 469–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ohashi A, deSilva DGV, Mobarry B, Manem JA, Stahl DA, et al. (1995) Influence of substrate C/N ratio on the structure of multi-species biofilms consisting of nitrifiers and heterotrophs. Water Science and Technology 32: 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ma JX, Wang ZW, Xu YL, Wang QY, Wu ZC, et al. (2013) Organic matter recovery from municipal wastewater by using dynamic membrane separation process. Chemical Engineering Journal 219: 190–199. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang QY, Wang ZW, Wu ZC, Han XM (2011) Sludge reduction and process performance in a submerged membrane bioreactor with aquatic worms. Chemical Engineering Journal 172: 929–935. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang P, Wang ZW, Wu ZC, Mai SH (2011) Fouling behaviours of two membranes in a submerged membrane bioreactor for municipal wastewater treatment. Journal of Membrane Science 382: 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cho BD, Fane AG (2002) Fouling transients in nominally sub-critical flux operation of a membrane bioreactor. Journal of Membrane Science 209: 391–403. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Judd S (2006) The MBR Book. Elsevier.

- 19. Butler MD, Wang YY, Cartmell E, Stephenson T (2009) Nitrous oxide emissions for early warning of biological nitrification failure in activated sludge. Water Research 43: 1265–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE, Attiya S, Bader JS, et al. (2005) Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 437: 376–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lu L, Xing D, Ren N (2012) Pyrosequencing reveals highly diverse microbial communities in microbial electrolysis cells involved in enhanced H2 production from waste activated sludge, Water Research. 46: 2425–2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.APHA (2012) Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 22nd ed. American Public Health Association/American Water Works Association/Water Environment Federation, Washington, DC, USA.

- 23. Hartree EF (1972) Determination of protein: a modification of the Lowry method that gives linear photometric response. Analytical biochemistry 48: 422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F (1956) Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Analytical Chemistry 28: 350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 25. He Z, Kun JJ, Wang YB, Huang YL, Mansfeld F, et al. (2009) Electricity Production Coupled to Ammonium in a Microbial Fuel Cell. Environmental Science & Technology 43: 3391–3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Han SS, Bae TH, Jang GG, Tak TM (2005) Influence of sludge retention time on membrane fouling and bioactivities in membrane bioreactor system. Process Biochemistry 40: 2393–2400. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ramdani A, Dold P, Deleris S, Lamarre D, Gadbois A, et al. (2010) Biodegradation of the endogenous residue of activated sludge. Water research 44: 2179–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Keskes S, Hmaied F, Gannoun H, Bouallagui H, Godon JJ, et al. (2012) Performance of a submerged membrane bioreactor for the aerobic treatment of abattoir wastewater. Bioresource Technology 103: 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang ZH, Gedalanga PB, Asvapathanagul P, Olson BH (2010) Influence of physicochemical and operational parameters on Nitrobacter and Nitrospira communities in an aerobic activated sludge bioreactor. Water Research 44: 4351–4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ma JX, Wang ZW, Yang Y, Mei XJ, Wu ZC (2013) Correlating microbial community structure and composition with aeration intensity in submerged membrane bioreactors by 454 high-throughput pyrosequencing. Water Research 47: 859–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ye L, Shao MF, Zhang T, Tong AHY, Lok S (2011) Analysis of the bacterial community in a laboratory-scale nitrification reactor and a wastewater treatment plant by 454-pyrosequencing. Water Research 45: 4390–4398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kragelund C, Levantesi C, Borger A, Thelen K, Eikelboom D, et al. (2007) Identity, abundance and ecophysiology of filamentous Chloroflexi species present in activated sludge treatment plants. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 59: 671–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bengtsson MM, Ovreas L (2010) Planctomycetes dominate biofilms on surfaces of the kelp Laminaria hyperborea. BMC Microbiology 10: 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Schematic of R0 fed with low COD/N-ratio municipal wastewater.

(TIF)

Nonlinear curve fit of Y and K d, and analysis of variance (ANOVA).

(TIF)

Rarefaction curves of OTUs defined by 3%, 5% and 10% distances in R0–R5 sludge samples.

(TIF)

Substrate composition for SOURs.

(DOCX)

More information on MBR configuration/operation and SOUR/SAUR/SNUR determination.

(DOCX)