Abstract

Ag-specific memory T cell responses elicited by infections or vaccinations are inextricably linked to long-lasting protective immunity. Studies of protective immunity amongst residents of malaria endemic areas indicate that memory responses to Plasmodia antigens are not adequately developed or maintained, as persons who survive episodes of childhood malaria are still vulnerable to either persistent or intermittent malaria infections. In contrast, multiple exposures to radiation-attenuated Plasmodia sporozoites (γ-spz) induce long-lasting protective immunity to experimental sporozoite challenge. We previously demonstrated that sterile protection induced by Plasmodium berghei (Pb) γ-spz is MHC-class I-dependent and CD8 T cells are the key effectors. IFN-γ+CD8 T cells that arise in Pb γ-spz immunized B6 mice are found predominantly in the liver and are sensitive to levels of liver-stage Ag depot and they express CD44hiCD62Llo markers indicative of effector/effector memory (E/EM) phenotype. The developmentally related central memory (CM) CD8 T cells express elevated levels of CD122 (IL-15Rβ), which suggests that CD8 TCM cells depend upon IL-15 for maintenance. Using IL-15 deficient mice, we demonstrate here that although protective immunity is inducible in these mice, protection is short-lived, mainly owing to the inability of CD8 TCM cells to survive in the IL-15 deficient milieu. We present a hypothesis consistent with a model whereby intrahepatic CD8 TCM cells, being maintained by IL-15-mediated survival and basal proliferation, are conscripted into CD8 TE/EM cell pool during subsequent infections.

Introduction

One of the cardinal features of Ag-specific immune responses elicited by infections or vaccinations is the persistence of optimally effective memory T cells that are inextricably linked to long-lasting protective immunity (1). Adequately maintained memory T cell pools assure fast, effective and specific response against reoccurring infections. Both the induction and the maintenance of memory T cells have been the subject of many elegantly conducted studies. The results from these studies provide much needed information towards the development of effective vaccines against viral, bacterial and protozoan infections, like malaria.

Maintenance of memory T cells is a very complex process involving many signals that are not yet fully understood. In some instances, particularly for CD8 T cells, the initial MHC:peptide-TCR interaction provides a sufficiently strong signal that the presence of long-lasting memory T cells is independent of persisting Ag (2). In other instances, particularly for intracellular pathogens that display tropism for non-lymphoid organs such as the kidney, lungs, or liver, Ag-depot is needed for the maintenance of memory CD8 T cells (3, 4). Signals provided to T cells by co-stimulatory molecules, e.g. B7 or OX40, expressed on APC do not appear to be essential for the maintenance of secondary memory responses (5, 6), although engagement of OX40 is needed for the induction of lasting protection to vaccinia virus (7). Amongst other extrinsic factors that have been shown to affect the development and persistence of memory T cells, cytokines, referred to as signal 3 providers, play a prominent role in supporting these processes (8). Nevertheless, even in these instances, the sorting of each cytokine regarding its specific effects upon the development, survival, and turnover of memory CD8 T cells is still being investigated. The γ-chain receptor-sharing cytokines, IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and to some extent IL-21, have been shown to have complementary and overlapping effects on CD8 T cell differentiation and function; although each cytokine also exerts a unique effect. For example, in most studies concerning acute responses to viral infections, IL-7 and IL-15 influence different CD8 T cell subsets; IL-7 promotes the accumulation of KLRG1loCD127hi cells, whereas IL-2 and IL-15 cause accumulation of KLRG1hiCD127lo CD8 T cells (9). In addition, IL-7 regulates the survival and viability of naïve and memory CD8 T cells (10), whereas IL-15 promotes survival and homeostatic proliferation (11, 12) as well as composition and differentiation of memory CD8 T cells (13).

The results from the majority of studies, particularly those dealing with viral infections, show reduced maintenance of memory CD8 T cells in IL-15 deficient mice (14, 15). On the other hand, studies detailing the role of IL-15 in protective immunity to the intracellular parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, show conflicting results; while studies from one laboratory illustrate that IL-15 aids in resistance to infection and memory CD8 T cell development (16), another study demonstrates that IL-15 is not required for NK and CD8 T cell expansion or for protracted protection (17).

In this study, we focused on the maintenance of protracted protection induced by radiation-attenuated (γ) Plasmodium berghei sporozoites (Pb γ-spz) and particularly on the role of CD8 T central memory (TCM) cells in this process. We demonstrated previously (3) that lasting protective immunity induced in this model is associated with the accumulation in the liver of CD8 T cells that can be divided into two major subsets: (1) an effector/effector memory (TE/EM) CD8 T cell phenotype (CD44hiCD45RBloCD62Llo), which is the major IFN-γ producer and is liver-stage (LS) Ag-dependent (3); and (2) a CD8 TCM cell phenotype (CD44hiCD45RBhiCD62Lhi), which is not affected by the level of the LS-Ag depot. Unlike CD8 TE/EM cells, CD8 TCM cells display a high concentration of IL-15Rβ (CD122hi). We previously hypothesized (18) that CD8 TCM cells function as a memory reservoir of CD8 T cells that, under the influence of IL-15 and MHC class I:peptide complexes derived from LS-Ag depot, give rise to IFN-γ producing CD8 TE/EM cells during re-infections.

IL-15 exerts its effects primarily on memory CD8 T cells by promoting their homeostatic proliferation and survival as well as differentiation into an effector population (14, 19); hence during re-infection, IL-15 would promote a shift from KLRG-1loCD127hi memory potential effector cells (MPECs) to KLRG-1hiCD127lo short-lived effector cells (SLECs) (9, 20). Because Pb γ-spz induced CD8 TE/EM and TCM cells express different densities of IL-15Rβ (CD122), we asked whether this differential receptor expression on each subset might predispose each memory CD8 T cell set to respond uniquely to IL-15. The unique responses to IL-15 by each subset would in turn suggest a different, yet related, role of each subset in protective immunity induced by Pb γ-spz.

To investigate the effects of IL-15 on the CD8 TE/EM and CD8 TCM cell subsets, we utilized IL-15-deficient mice and examined CD8 T cell responses following multiple immunizations with Pb γ-spz and 1° and 2° homologous challenge with infectious sporozoites. Because IL-15 deficient mice have greatly diminished numbers of CD8 T (especially CD44hi phenotype) and NK cells, and because the residual CD44 hiCD8 T cells are nearly all IL-2Rβlo cells (21), we asked whether effector and/or memory CD8 T cells are inducible in IL-15-deficient mice and if these mice could manifest long-term protection against blood stage parasitemia upon challenge with infectious sporozoites.

Our results demonstrate that although IL-15-deficient mice immunized with Pb γ-spz were protected against 1° sporozoite challenge, they succumbed to parasitemia upon a 2° challenge 2 months later. Apart from demonstrating an absolute need IL-15 for durable protection, our results reveal a critical role of CD8 TCM cells in maintaining protection. These are novel observations in malaria pre-erythrocytic stage infection and are extremely important towards the shaping of our understanding of Plasmodia-induced immunity and towards developing more effective anti-malaria vaccines. For example, these observations are paramount in view of our current observations from malaria clinical trial studies in which we show that Ag-specific memory T cell phenotypes are inducible (22), yet, these memory T cells appear to be inadequately maintained to prevent malaria infection upon experimental re-challenge with P. falciparum.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Female C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME). Female IL-15deficient (KO) (6–8 weeks old) mice were purchased from Taconic Labs (Germantown, NY). All mice were housed in accordance with Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) guidelines. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in a facility accredited by the Association for Assessment of Laboratory Animal Care International.

Plasmodium berghei sporozoites, immunizations and parasitemia

P. berghei sporozoites (cloned ANKA strain (23)), maintained by cyclical transmission in mice and Anopheles stephensi, were isolated from the salivary glands of female mosquitoes as described previously (3). For the induction of protective immunity P. berghei spz were dissected from mosquitoes 18–22 days after blood meal and used either immediately or after attenuation with γ-radiation (15,000 Rad) (Cesium-137 source Mark 1 series; JL Sheppard & Associates, San Fernando, CA). Sham-dissected preparations obtained from the salivary glands of non-infected mosquitoes were treated identically to sporozoites and were used as controls. Mice were primed i.v. with 75K γ-spz followed by 2 weekly immunizations of 20K γ-spz. Naïve control and γ-spz-immunized mice were challenged i.v. with 10K sporozoites between 7–10 days after the last boost (1° challenge) or 2 months (~60 days) following 1° challenge (2° challenge) (Fig. 3A). Thin blood smears were prepared daily from individual mice starting on day 4 after the challenge and followed for up to 14 days, and parasitemia was determined microscopically from Giemsa stained slides

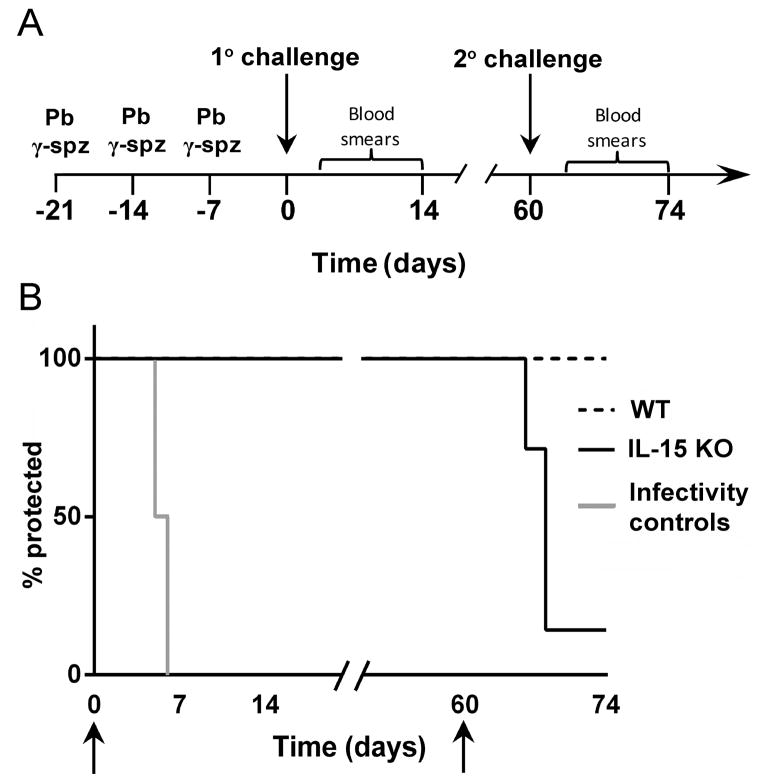

Figure 3. Immunization with Pb γ-spz induces sterile protection in IL-15KO mice at primary, but not upon secondary challenge.

(A) A schematic representation is shown for immunization with Pb γ-spz and 1° and 2° challenge regimen. Wt and IL-15KO mice (5 mice/group) were immunized 3 times with Pb γ-spz one week apart (day -21, -14, -7) and were challenged with infectious sporozoites one week later, day 0, for 1°challenge. Mice were monitored for parasitemia by thin blood smears starting on day 4 and continuing for 14 days after the challenge. Two months later (~day 60), wt and IL-15KO mice protected previously at 1° challenge received a 2° challenge with 10K infectious sporozoites and mice were monitored daily for parasitemia starting on day 3 and continuing for 14 days post 2° challenge. Mice that became parasitemic were considered not protected. (B) Arrows represent days of challenge, results expressed as % sterile protection are from several separately performed experiments. Naïve mice that received 10K infectious sporozoites served as infectivity controls. In two out of more than 10 experiments that yielded reproducible protection results, IL-15KO mice became parasitemic after the 1° challenge. Although the reasons for the failure to protect IL-15KO mice are multi-fold, including the quality of the sporozoite preparations, we noted that the IL-15KO mice used in these two experiments were considerably older than mice that we typically use.

Isolation of Intrahepatic Mononuclear Cells (IHMC)

Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation according to protocol guidelines. IHMC were isolated from the livers as described previously (3). Briefly, livers were exposed and the inferior vena cava was cut for blood outflow. After perfusion with 10ml PBS (24), livers were removed and pressed through a 70μM nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences San Jose, CA). IHMC were isolated from the liver cell suspension on a 35% Percol gradient (GE Healthcare Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and red blood cells (RBC) were lysed with RBC lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The IHMC were washed and resuspended in complete medium consisting of RPMI 1640 containing 10% heat inactivated FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 10mM Hepes, 50U/ml penicillin, 50μg/ml streptomycin, 1mM Sodium Pyruvate, GlutaMAX and non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) and 50μM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell counts were performed by the trypan blue exclusion test.

Lymphocyte Separation

CD8 T cell separation was done by CD8 negative selection using magnetic bead isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Where indicated, CD8+ and CD8− T cell subsets were separated further into CD62L+ and CD62L− populations using CD62L positive selection kit (Miltenyi Biotech).

3H-thymidine incorporation

For 3H-thymidine (3H-TdR) uptake, magnetic bead (Miltenyi Biotech) isolated subsets of CD8+ and CD8− T cells were cultured for 96 hours in the presence of recombinant mouse IL-15 at 50ng/ml or 100ng/ml (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN). During the last 16hrs of culture, 1μCi of 3H-TdR (Perkins Elmer, Waltham MA) was added to each well. Cells were harvested using a cell harvester (Perkin Elmer) and 3H-TdR uptake was quantified using Trilux MicroBeta (Perkin Elmer) scintillation counter.

Flow Cytometry

Surface staining of phenotypic markers was performed using anti-CD3 (17A2), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD8 (53–6.7), anti-CD44 (IM7), anti-CD45RB (16A), anti-CD62L (MEL-14), anti-CD122 (TM-b1) and anti-CD127, (A7R34) (BD Biosciences) as indicated in figure legends. FcR was blocked during surface staining using unlabeled anti-CD16/32 (2.4G2 BD Biosciences). Caspase-3 was detected using 46-Caspase 3 (BD Biosciences). Dead cells were labeled using PE labeled AnnexinV (BD Biosciences) and Live/Dead® Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain for UV Excitation (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes). Intracellular staining for Bcl-2 (BD Biosciences) was performed following surface staining using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm according to manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometry data was collected using BD FACSCalibur or LSRII instruments and analyzed using CellQuest (BD Biosciences) or FlowJo (Tree Star, Inc) software. 1×106 cells were stained in each sample and >100,000 live lymphocyte events were collected. Where appropriate, cell counts were derived from multiplying % gated events by total cell counts obtained by trypan blue exclusion test.

CFSE labeling

Total CD8+ T cells, isolated by negative magnetic bead selection and were stained with 10nM CFSE (Invitrogen -Molecular Probes) in PBS for 30 min at 37°C, washed 3 times, and cultured for 7 days in the presence of recombinant mouse IL-15, IL-2 (R&D Systems) or plate-bound α-CD3 mAb (145-2C11, BD Biosciences). Following culture, cells were stained with anti-CD44 and anti-CD45RB to delineate memory cell subsets.

In vivo proliferation by BrdU incorporation

In vivo proliferation of liver CD8 T cells, CD4 T cells and NK1.1T cells as well as NK cells was measured by BrdU (Sigma) incorporation assay (25). Mice were fed BrdU 0.8 mg/ml in drinking water replaced daily for 7 days prior to analysis. IHMN cells were isolated and stained using FITC BrdU staining kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were stained for the indicated surface markers after which cells were fixed and permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences) and washed in Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosciences). Cells were then incubated with Cytoperm Plus (BD Biosciences) and washed. BrdU was exposed by treatment with DNase and stained using anti-BrdU-FITC labeled antibody. Immunofluorescent staining of incorporated BrdU was performed using BrdU Flow Kit (BD Bioscience). Total numbers of IHMC were counted and were used to determine absolute number of CD8 TE/EM and CD8 TCM cell subsets.

IFN-γ cytokine secretion assay

The IFN-γ determinations were performed using the secretion assay detection kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec) and as described previously (3). Briefly, IHMC were washed twice with cold PBS-0.5% BSA (Sigma) and 2 mM EDTA (Sigma), and were resuspended at 106cells/90 μl cold RPMI 1640 with 5% normal mouse serum plus 10 μl of IFN-γ capture reagent and were incubated on ice for 5 min and then diluted up to 105cells/ml with warm RPMI 1640 with 5% normal mouse serum, transferred into flat-bottom 12-well plate, and incubated for 45 min at 37°C. After two washes, cells were resuspended in 90 μl of cold PBS (Invitrogen) and incubated with 10 μl of IFN-γ detection reagent for 10 min at 4°C. After the final two washes in PBS, cells were resuspended in 100 μl of freshly prepared propidium iodide at 50 μg/ml (Invitrogen) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data was analyzed by CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Preparation of Kupffer Cells

IHMC were isolated from livers and incubated with anti-CD8 and anti-CD4-conjugated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech), washed and then applied to a MS magnetic column. The flow through cells were labeled with biotinylated anti-Mac3 Ab (Cederlane, Ontario, Canada) and anti-biotin beads (Miltenyi Biotec), and applied to a second MS column. After removal of unlabeled cells, the bound Mac3+ Kupffer cells (KC) were eluted. The identity of KC was determined as described previously (26).

RT-PCR

RNA was isolated from the Kupffer cells lysed in TRIzol (Invitrogen) and 5 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript II (Invitrogen). Mouse genomic DNA was isolated using DNA STAT-60 (Iso-Tex Diagnostics, Inc, Pearland, TX) and diluted to 100 μg/μl, as previously described. Quantitative–PCR reactions were established (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with the following primers for IL-15 (Forward Primer: CTCTACCTTGCAAACAGCACTC, Reverse Primer: CAGCCAGATTCTGCTACATTCT), and for GapDH (Forward Primer: TCCCTCACAATTTCCATCCC, Reverse Primer: CCCTAGGCCCCTCCTGTTATT, Invitrogen), using the incorporation of cyber green as the read out. Assays were done on a 96-well plate format and the detection of the PCR products were performed using and ABI 7700 (PE Applied Biosystems) under the following conditions: 1 cycle at 95°C for 10 minutes, and 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 55°C for 1 minute. Standard curves were generated from a DNA standard and the amount of cDNA was determined for each sample. Quantitative IL-15 gene expression was done in triplicate and expressed as a ratio of IL-15 over GAPDH for each time point (26).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software using unpaired two-tailed t-test for unequal variances, Mann-Whitney U-test or 2-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post test where appropriate. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Liver CD8 TCM cells undergo selective in vitro proliferation and enhanced survival in the presence of IL-15

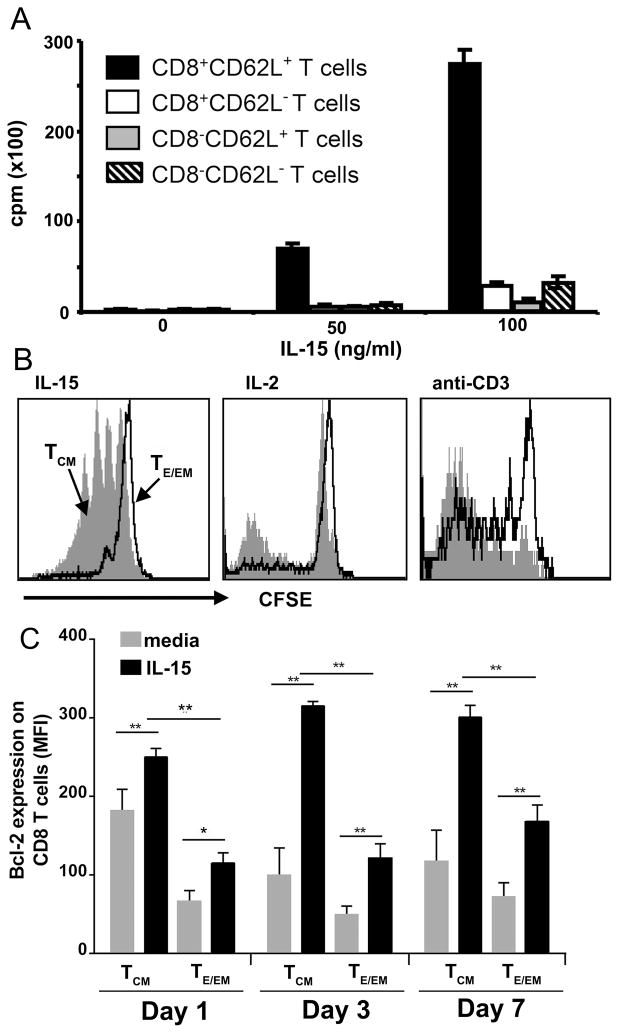

It has been demonstrated that cytokines, by providing signal to T cells via the shared γ-chain receptor, maintain survival of naïve and memory CD8 T cells (27). CD8 TCM cells (CD44hiCD45RBhiCD62Lhi) that accumulate in the liver of mice immunized with Pb γ-spz express considerably higher levels of CD122 (IL-15Rβ/IL-2Rβ) than the major IFN-γ producing CD8 TE/EM cells (CD44hiCD45RBloCD62Llo), or CD8 Tnaive cells (CD44lo) (3) (Fig. S1A–D), which suggests an enhanced sensitivity of CD8 TCM cells to either IL-15 or IL-2. We measured in vitro proliferation to soluble IL-15 (3H-TdR uptake) of enriched CD8+ and CD8− T cells isolated from livers of mice immunized thrice with Pb γ-spz. CD8+CD62Lhi T cells proliferated in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A) and all other cultures, including CD8+CD62Llo T cellsand CD8−CD62Lhi and CD8−CD62Llo Tcells, exhibited approximately 5-fold lower proliferation, even at 100 ng/ml of IL-15. We confirmed this observation by the dilution effect of CFSE labeled total liver CD8 T cells isolated from Pb γ-spz immunized mice. In the presence of soluble IL-15, CD8 TCM cells but not CD8 TE/EM cells underwent several rounds of division; IL-2 induced much less proliferative activity than IL-15, but had a discernible effect on both CD8 T cell subsets (Fig. 1B); anti-CD3 mAb, as expected, also induced proliferation of both CD8 TCM and CD8 TE/EM cells (Fig. 1B). A population of CD8 TE/EM cells that did not proliferate to anti- CD3 mAb likely belongs to terminally differentiated SLECs. Collectively, these observations establish that IL-15 selectively induced in vitro proliferative activity of liver CD8 TCM cells from mice exposed to protective doses of Pb γ-spz.

Figure 1. CD8 TCM cells, having elevated expression of IL-15Rβ (CD122), are the primary cells responding to IL-15.

IHMC were isolated from C57BL/6 mice (3 per group) 1 month after a tertiary immunization with Pb γ-spz. (A) CD62L+ and CD62L− T cells were separated by magnetic bead isolation procedure; a second round of isolation using CD8 magnetic beads resulted in the following subpopulations: CD8+CD62L+ and CD8+CD62L− T cells as well as CD8−CD62L+ and CD8−CD62L− T cells. Each T cell subset was cultured at 4 × 105 cells/0.2 ml culture medium for 96 hours in the presence of the indicted concentrations of IL-15; during the last 16hrs of culture, 1μCi of 3H-TdR was added to each well. Results are presented as the mean CPM ± SD of 3H-TdR uptake in triplicate wells and are representative of 3 separate experiments. (B) Liver CD8 T cells, isolated by negative magnetic beads selection, were stained with CFSE and incubated for 7 days in the presence of 100 ng/ml IL-15, or 100ng/ml IL-2. Harvested cells were stained with mAbs against CD8, CD44 and CD45RB. Lymphocytes were gated on a forward-side scatter plot, and gates were applied to identify CD8+ T cells that expressed either CD44hiCD45RBhi (TCM cells) or CD44hiCD45RBlo (TE/EM cells) phenotypes. Histogram plots represent CFSE dilution with gray shaded area representing CD8 TCM cells and solid contour line representing CD8 TE/EM cells. These results represent one of two separate experiments. (C) Liver CD8 T cells were cultured in the presence of either 100 ng/ml IL-15, or medium alone. Cells were harvested on day 1, 3, and 7 and stained with mAbs against CD44 and CD45RB as described above, fixed, permeabilized and stained with mAbs against Bcl-2. Mean fluorescent intensity (determined for each individual mouse and is presented as the mean ± SD) of Bcl-2 expression of TCM or TE/EM. Bcl-2 determinations on CD8 TCM and CD8 TE/EM cells prior to culture showed MFI=189± 45 for CD8 TCM and MFI= 76± 35 for CD8 TE/EM. Results are representative of 3 separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

IL-15 also has been shown to enhance survival of memory CD8 T cells by up-regulating anti-apoptotic molecules such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL (28, 29). We evaluated the expression of Bcl-2 on liver CD8 T cells in our protection model. Amongst the IHMC isolated 1 week after the third immunization with Pb γ-spz and cultured with IL-15, CD8 TCM cells significantly up-regulated the expression of Bcl-2 compared to control media, and significantly exceeded the expression of Bcl-2 on CD8 TE/EM cells from the same group of mice (Fig. 1C). While IL-15-stimulated cultures of CD8 TCM cells sustained Bcl-2 expression for 7 days, control cultures in medium alone, similar to cultures stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb (data not shown), showed down-regulated expression of Bcl-2 after 3 days of culture. Thus, as previously shown for spleen CD8 T cells (11), liver CD8 TCM cells also are the primary responders to IL-15 in regards to increased survival.

IL-15 deficient mice respond to immunization with P. berghei γ-spz by expanding liver IFN-γ+CD8 T cells

T cell and B cell responses directed to the non-repeat (30) and the repeat regions (31), respectively, of the circumsporozoite protein (CSP), the major protein antigen present on Plasmodia sporozoites, have been shown to be linked to protection induced by Plasmodia γ-spz (32, 33). Other Ags representing pre-erythrocytic stages, and specifically Ags expressed during LS development, have also been shown to be involved in protection (32, 34–36). We demonstrated previously that owing to drug-induced reduction of LS-Ag depot, protection wanes concurrently with declining CD8 TE/EM cells (3), which, expectedly, is not the case with effector CD8 T cells specific for epitopes on CSP (37, 38). We, as well as others, have proposed that the longevity of protective immunity (3, 39) and the effectiveness of CD8 TE/EM cells (3) are linked to the levels of LS-Ag depot derived from partially developed Plasmodia γ-spz. However, no links between CD8 TCM cells and Plasmodia γ-spz-induced protective immunity or immunity induced by natural exposure have thus far been investigated. Yet, CD8 TCM cells have been considered the key cells that maintain lasting protection (40) and in some infections, protective immunity has been shown to be largely dependent upon CD8 TCM cells (41).

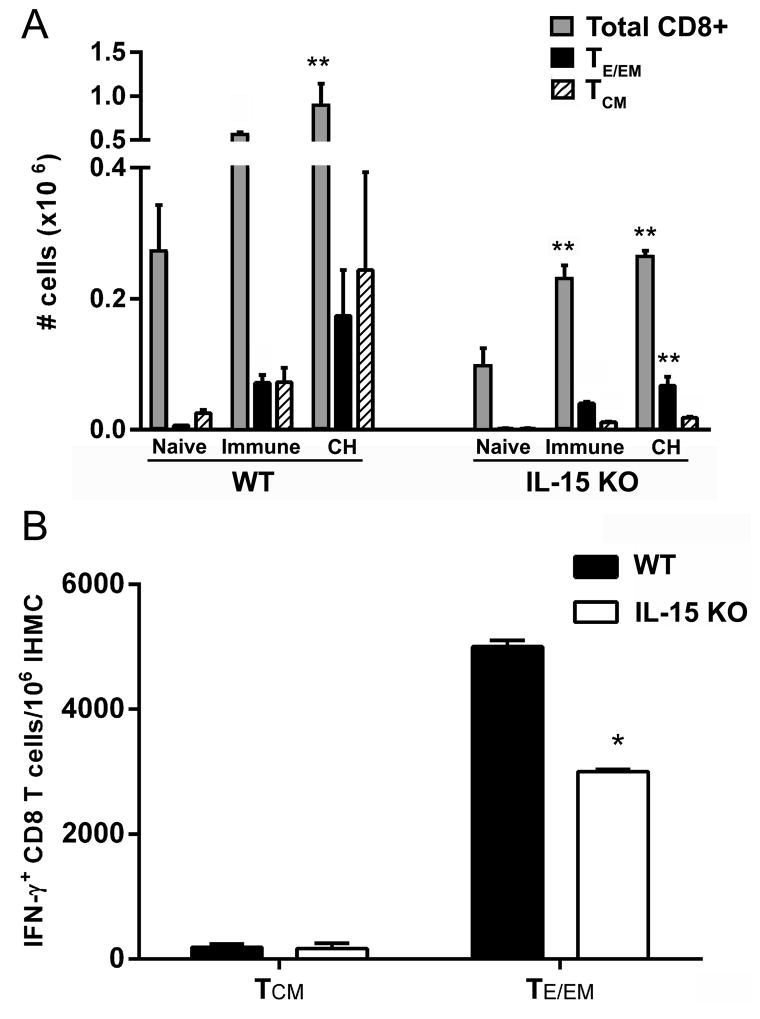

Because liver CD8 TCM cells preferentially responded in vitro to IL-15 (Fig. 1A–C), we utilized IL-15 deficient mice to test whether the absence of IL-15 might reveal a role of CD8 TCM cells in protective immunity in the Pb γ-spz model. IL-15KO mice have reduced numbers of CD8 T cells, NK T cells, and NK cells (15), nonetheless, the Ag-specific repertoire of CD8 T cells remains intact (14, 16). We monitored liver CD3+CD8 T cells from Pb γ-spz immunized wt and IL-15-deficient mice for the expression of an activation marker (CD44hi) indicative of Ag exposure and compared the numbers of CD44hiCD8 T cells between the two groups of mice. As shown previously for other organs (21), livers from naïve wt mice had twice as many CD3+CD8 T cells as IL-15 deficient mice. After the 3rd immunization with Pb γ-spz, the number of total liver CD3+CD8 T cells doubled with a concomitant increase of CD8 TE/EM cells in both groups of mice (Fig 2A); however, the increase of CD8 TCM cells was considerably lower in the IL-15 KO mice compared to wt mice. Upon primary challenge (~ 7 days after the last boost immunization with Pb γ-spz), the absolute number of CD3+CD8 T cells significantly increased in wt mice, whereas in the IL-15KO mice the number of total CD3+CD8 T cells, although significantly higher relative to naïve cells, did not change. The number of CD8 TE/EM cells rose in both groups and the ratio of TE/EM:TCM clearly favored the former subset in IL-15KO mice (Fig. 2A). We also observed this skewing towards CD8 TE/EM cells in a separate experiment; 2 months after the last Pb γ-spz boost immunization of wt and IL-15KO mice, where the percentage of CD8 TE/EM cells exceeded CD8 TCM about ~7-times in IL-15KO mice, but only ~1.4 times in wt mice (Fig. S2). The skewing towards the CD8 TE/EM subset in IL-15KO mice might have resulted from attrition of IL-15-dependent CD8 TCM cells or from a compensatory action of other γ chain cytokines that enhances the survival of CD8 TE/EM cells. As shown by others, differentiation of CD8 T cells is programmed following Ag exposure (41) and effector CD8 T cells do accumulate in γ-chain cytokine deficient mice (42). Regardless of the mechanism responsible for the skewing towards CD8 TE/EM cells, these results establish that IL-15KO mice responded to pre-erythrocytic stage antigens expressed by the partly developed Pb γ-spz.

Figure 2. IL-15KO CD8 T cells respond to antigen from Pb γ-spz.

Wt and IL-15KO mice (3–5 mice/group) were immunized with 3 weekly doses of Pb γ-spz followed one week later by infectious sporozoite challenge as described in materials and methods. (A) Livers from naïve, immune, or immune/challenged (CH) mice were isolated 1 week after last exposure to antigen and stained with anti-CD3, -CD8, -CD44, -CD62L mAbs to determine the number of total CD8 T cells, CD8 TE/EM cells and CD8 TCM cells. The results show the number of cells as the mean ± SD (B) IHMC were isolated from wt and IL-15KO mice one week following the 3rd immunization with Pb γ-spz. IFN-γ was detected by cytokine secretion assay, as described in Materials and Methods. CD8 T cells were enriched by magnetic bead separation and CD44hiCD45RBhi or CD44hiCD45RBlo T cells were identified by flow cytometry. The results are representative of several experiments performed under the same conditions and show the number of IFN-γ secreting CD8 TCM cells and CD8 TE/EM cells per 106 IHMC determined for each individual mouse and are presented as the mean ± SD, *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

It has been established that IFN-γ-producing effector CD8 T cells are the main mediators of protection induced by attenuated Plasmodia sporozoites (43–45). Although it has been shown that IL-15 modulates the differentiation of CD8 T cells into IFN-γ producing or perforin- and granzymes A- and B-expressing cells (13, 46, 47), we considered the possibility that the increased percentage, as well as cell number, of CD8 TE/EM cells in IL-15KO mice may also reflect an elevated IFN-γ production by CD8 T cells. Comparing IFN-γ+CD8 T cells between wt and IL-15KO mice immunized thrice with Pb γ-spz revealed that IL-15KO mice had significantly lower frequency of IFN-γ+CD8 T cells than wt mice: 3 × 103 cells/106 IHMC vs. 5 × 103 cells/106 IHMC, respectively (Fig. 2B). Nonetheless, IL-15KO mice immunized with Pb γ-spz were able to mount inflammatory cytokine producing CD44hiCD8 T cells before 1° challenge, which further confirms that IL-15KO mice were able to respond to antigens associated with Pb γ-spz.

IL-15 is not required for induction, but is needed for the maintenance of protective immunity induced by Pb γ-spz

The observation that immunization with Pb γ-spz induced both IFN-γ+ CD8 T cells and the expansion of CD8 TE/EM cells in IL-15 deficient mice prompted us to ask if these responses were sufficient to confer protection against infectious sporozoite challenge. Groups of wt and IL-15KO mice exposed to 3 weekly doses of Pb γ-spz were challenged with 1K infectious sporozoites between days 7 and 10 after the last boost immunization, along with naïve infectivity control mice, and sterile protection was determined by blood smears starting on about day 4 after the challenge (Fig. 3A). Both wt as well as IL-15KO mice were protected (14 days) and did not develop blood stage parasitemia, while infectivity control mice became parasitemic within 5 –7 days after exposure to infectious Pb sporozoites (Fig. 3B). On the basis of these results, we conclude that IL-15 was not needed for the induction of protective immunity. Clearly, functional effector CD8 Tcells arose to Pb γ-spz immunization in the absence of IL-15 and this response appeared to be sufficient to protect mice during 1° sporozoite challenge; severely reduced numbers of CD8 TCM cells did not affect this phase of protection induced with Pb γ-spz.

A sine qua non of a successful vaccine is Ag-specific durability of its protective effects. Exposure to Plasmodia γ-spz has been shown to provide sterile and long-lasting protection in both human and animal models, and, therefore, γ-spz vaccine is considered the gold standard of anti-malaria vaccines (48). We, and others, have firmly established that sterile protection induced by Pb γ-spz in wt mice is long-lived (3, 33). We compared the durability of protection in wt and IL-15 deficient mice by re-challenging mice that were protected 2 months previously (Fig. 3A). While wt mice remained protected, the majority (85%) of previously protected IL-15KO mice became parasitemic between days 5–9 after re-challenge (Fig 3B). All infectivity control mice became parasitemic between days 4 – 7 after infection (data not shown). In contrast to the induction of protection, durability of protection was clearly IL-15 dependent. This single observation underscores the importance of IL-15 in the maintenance of protection induced by Pb γ-spz against experimental sporozoite challenge, and by extension, it highlights the importance of CD8 TCM cells and suggests a link between IL-15 and CD8 TCM cells in this process.

We also considered that the failure to maintain long-term protection might be related to some deficits of NK or NKT cells in IL-15KO mice as IL-15 has a strong effect on the proliferation of NK and NKT cells (49). We measured absolute cell numbers and assessed proliferative responses (data not shown) of liver NK, and NK1.1+ T cells from wt and IL-15KO mice. As expected, the cell number of both NK and NK1.1+ T cells were reduced by 90% in IL-15KO mice as compared to wt mice (Fig S3A). Because the decline of NK1.1+ T cells and NK cells was already apparent at 1° challenge, when IL-15KO mice were protected, these results confirm previously established observations, that protection in B6 mice is mediated mainly by effector CD8 T cells (3, 45) rather than by NK or NK1.1+ T cells. Analyses of liver CD4 T cells showed that neither the absolute cell number nor the number of proliferating cells (data not shown) were statistically different between the two groups of mice at 2° challenge, when IL-15KO mice became parasitemic (Fig. S3B). According to these observations, liver CD4 T cells have not been compromised by the lack of IL-15 and thus do not appear to have a role in the IL-15 impact on lasting protection induced by Pb γ-spz. Although it has been shown that IL-15 readily substitutes for CD4 T cell helper activity in CD8 T cell responses (50), our results do not suggest any reciprocal affects of CD4 T cells on CD8 T cell responses in IL-15KO mice.

IFN-γ-producing CD8 T cells are induced in IL-15KO mice immunized with Pb γ-spz

The disparate outcomes of 1° and 2° challenges were not completely surprising in view of our current understanding of the IL-15 effects on CD8 T cells. IL-15 affects mainly memory CD8 T cells by promoting differentiation of MPEC to terminal effector CD8 T cells (19), enhancing cellular turn-over (14), and maintaining their survival (11). In consideration of these multiple effects, we hypothesized that the absence of IL-15 likely caused a global disturbance of memory CD8 T cell formation and/or function that ultimately resulted in the failure to maintain long-lasting protection induced by Pb γ-spz.

IFN-γ+CD8 T cells represent the hallmark of protective immunity induced in the Pb γ-spz model (45) and IFN-γ+CD8 T cell responses, albeit significantly lower than in wt mice, were nonetheless present in IL-15KO mice prior to primary challenge (Fig. 2B; Fig. 4). As has been originally proposed by Ahmed and Gray (1) and confirmed by others (51, 52), the breadth of the effector CD8 T cell population during the induction phase of immune response determines the size of the memory pool. On the basis of the above observations (Fig. 2B), we considered the possibility that the failure of IL-15KO mice to maintain lasting protection might be linked to reduced memory pool and hence fewer functioning CD8 T cells, e.g., IFN-γ producing, effector CD8 T cells upon re-challenge. If indeed memory CD8 T cells relied on IL-15 for the maintenance of memory cells pool size, or a transition from CD8 TCM or CD8 TE/EM to CD8 TE cells, the numbers of IFN-γ+CD8 T cells would be considerably lower in IL-15KO mice at 2° challenge, when the mice were no longer protected.

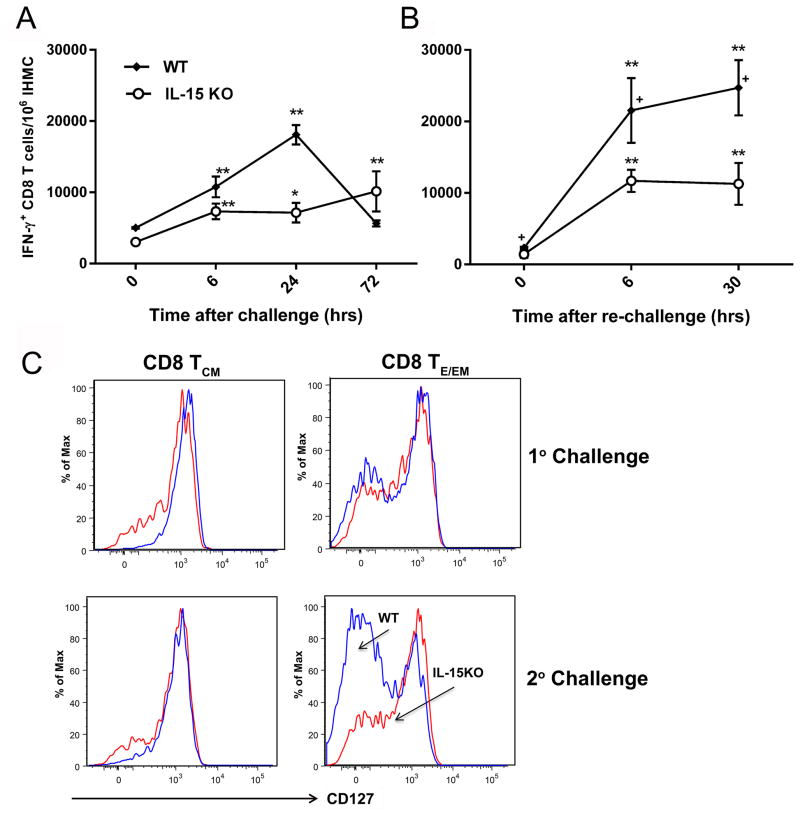

Figure 4. Failure to maintain protracted protection in IL-15KO mice is partly due to low numbers of IFN-γ producing CD8 T cells and the inability to transition to CD127lo TE/EM cells.

Pb γ-spz immunized wt and IL-15KO mice received 1° and 2° challenge with infectious sporozoites as described in legend for Fig. 3. At indicated time (hrs) points after (A) 1°challenge and (B) 2° challenge (re-challenge at 2 months after 1°challenge), liver CD8 TE/EM cells were examined for IFN-γ by cytokine secretion assay by flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods and in legend for Fig. 2B. Results from a representative of three separate experiments are shown as the mean ± SD of the number of IFN-γ+CD8 T cells/106 IHMC from 3 mice per group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 indicates significance of each time point relative to 0hrs. + p<0.05 indicates significance between wt and IL-15KO mice. (C) IHMC were isolated 24 hrs following 1° or 2° challenge, as described in legend for Fig. 3B. Representative flow plots show results for CD127 expression on CD8 TCM and CD8 TE/EM at 24 hrs after 1° or 2° challenge. The CD127-population was induced after the 3 immunizations with Pb γ-spz and it reverted back to CD127+ populations over time. As shown here, the CD127- population returned upon challenge and re-challenge with infectious Pb sporozoites of wt mice; in IL-15KO mice, the CD127- population was substantially reduced in re-challenged mice.

Both IL-15KO and wt mice were immunized thrice with Pb γ-spz and we determined the numbers of IFN-γ+CD8 Tcells in both groups of mice at several critical time points during 1° and 2° challenges. At 0 hrs (day of 1° challenge), IL-15-deficient mice responded robustly with nearly 3000 IFN-γ+CD8 T cells/106 IHMC cells vs. 5000 IFN-γ+CD8 T cells/106 IHMC in wt mice. The IFN-γ responses doubled in each group 6 hrs post challenge; 24 hrs post challenge, the response peaked (18,000/106 IHMC) in wt, while in IL-15-deficient mice, the response remained nearly the same (7000/106 IHMC) (Fig. 4A). There was a small spike of reactivity, however insignificant relative to reactivity at 24hrs in IL-15KO mice at 72 hrs, at which time the response in wt mice decreased to a baseline level. We have observed (3) that IFN-γ+CD8 T cell numbers fluctuate, particularly during the first week after the challenge. The key observation that emerged from these experiments was that like wt mice, IL-15KO mice, despite significantly lower IFN-γ+CD8 T cell responses prior to challenge, responded swiftly after the 1° challenge, which is essential to prevent blood stage parasitemia (3). A significantly higher response relative to pre-challenge was also maintained for 72hrs. Because antibodies also contribute to protection in this model, it should be noted that the anti-Pb CSP antibody responses were identical in both groups of mice (data not shown).

IFN-γ+CD8 T cell responses declined in both groups of mice 2 months after the 1° challenge (~day 60 or the day of 2° challenge). Six hrs after the 2° challenge, the number of IFN-γ+CD8 T cells rose significantly in both groups and responses remained at a plateau (Fig. 4B). However, the numbers IFN-γ+CD8 T cells in wt mice significantly exceeded those in IL-15KO mice at 6 and 30 hrs. We chose not to monitor IFN-γ+CD8 T cell responses beyond 30 hrs after 2° challenge primarily because the onset of parasitemia is known to interfere with responses induced by pre-erythrocytic stage-Ag. According to results from other studies, the absence of IL-15 has a negligible effect on the production of inflammatory cytokines by boosted memory CD8 T cells (17). In contrast, in the Pb γ-spz model, CD8 T cells were lower IFN-γ producers after challenge in IL-15KO mice relative to wt mice. The reasons for this difference remain unclear, but since the initial number of the responding effector CD8 T cells determines the memory CD8 T cell pool size (1), the initial lower cell number of the IFN-γ+CD8 T cells at pre-challenge in IL-15KO may have resulted in the lower breadth of responses that followed upon 2° challenge. It is also possible that Pb γ-spz-induced CD8 TCM cells are dependent on IL-15 for differentiation and/or transition to IFN-γ-producing terminal effector CD8 T cells.

A threshold of an effective IFN-γ+CD8 T cell response needed for sterile protection has been suggested, however, such a threshold has not been clearly defined in terms of cell numbers or cytokine levels. The threshold also varies among different murine Plasmodia, the source and type of CD8 T cells, as well as the assay used for determinations (53). Additionally, variations have been observed from experiment to experiment. On the basis of our observations, it is clear that IL-15 deficient mice showed lower responses than wt mice (Figs 4A&B). Nevertheless, the responses were not strikingly low to account for the failure of IL-15KO mice to maintain protective immunity at re-challenge compared to primary challenge. Similar observations have been made in other systems showing that despite the absence of a single γ-chain cytokine, formation of robust effector CD8 T cells does occur (42).

If IL-15 indeed affects the expression of phenotypic markers and functional attributes of memory CD8 T cells (13, 42), such as the transition from CD127hiCD62LhiCD8 TCM cells to a population of CD127loCD62LloCD8 TE cells, such transition would be less evident in IL-15KO than in wt mice exposed to Pb γ-spz. A compromised ability to transition to CD127loCD62loCD8 T cells may explain the lower IFN-γ response observed in IL-15KO, particularly during a re-challenge. We examined both CD44hiCD62LhiCD8 TCM cells and CD44hiCD62LloCD8 TE cells for the expression of CD127 24 hrs after 1°and 2° challenge. Liver CD8 TCM cells expressed nearly similar CD127 profiles in wt and IL-15KO mice and they persisted for 2 months as shown during the 2° challenge (Fig 4C). Because IL-15 and IL-7 overlap in the induction of CD8 T cell response, in the absence of IL-15, IL-7 might have been responsible for the preservation of CD62LhiCD127hiCD8 T cells in IL-15KO mice. In contrast, 24 hrs after 2° challenge, we observed a transition of CD8 TE/EM cells to CD127lo in wt mice, whereas in IL-15KO mice, the majority of CD62Llo CD8 T cells remained as CD127hi phenotype. Our observation that the loss of CD127, which indicates differentiation of MPECs into terminal effector cells (42), required IL-15 is in agreement with results from other studies that the availability of IL-15 allows long-lived memory to transition to short-lived IFN-γ producing effector cells (13). Further studies are needed to determine whether CD127hi cells in IL-15KO mice represent a true long-lived memory CD8 T cell, or if they are sustained by IL-7, which may not be critical for the determination of memory formation as shown during acute viral infection (54).

Attrition of CD8 TCM cells is coincident with the failure to maintain protracted protection in IL-15KO mice

Amongst the in vivo activities regulated by IL-15, basal proliferation of CD8 T cells is yet another of its signatures. We hypothesized that proliferation of CD8 TCM cells might be significantly reduced in Pb γ-spz immunized IL-15-deficient mice, because as we showed here (Fig 1) and as was shown by others (55), these cells depend on IL-15 more than CD8 TEM cells by the virtue of having elevated expression of CD122 (Fig S1C). A decreased cellular turnover, which has been reported previously for 2° memory CD8 T cells (13), would clearly lead to a severely contracted reservoir of CD8 TCM cells. Partly activated CD8 TCM cells are needed for a quick differentiation into effectors to sustain functional properties of CD8 T cells that provide a robust response during re-infection.

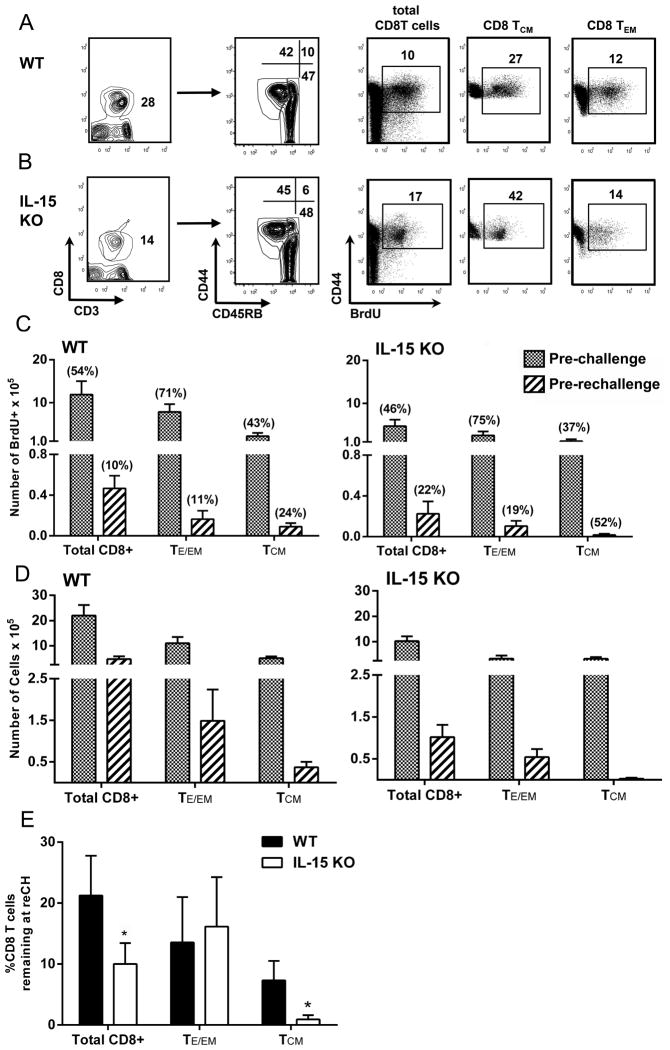

To examine if indeed CD8 TCM cells in IL-15KO mice have reduced proliferative activity in relation to wt mice, we measured BrdU incorporation by CD8 T cells in wt and IL-15KO mice for 7 days prior to either 1° or 2° challenge. Results from initial BrdU uptake experiments that were conducted in mice immunized with sham-dissected salivary glands material from non-infected Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes ruled out the possibility that proliferation of CD8 T cells stems from contaminants present in the hand-dissected sporozoite preparations (Fig. S4). The gating strategies for liver CD3+CD8 T cells and the respective CD8 TE/EM (CD44hiCD45RBlo) and CD8 TCM (CD44hiCD45RBhi) phenotypes are depicted for wt and IL-15KO mice in Figs. 5A&B, respectively. In addition, we show gating strategies for BrdU+ total liver CD3+CD8 T cells and the respective CD8 TCM and CD8 TEM cell subsets (Fig. 5A&B), where the numbers in each panel reflect the percentage of the designated BrdU+CD8 T cells from a representative single mouse from each group prior to 2° challenge.

Figure 5. Attrition of CD8 TCM cells in Pb γ-spz immunized IL-15KO mice at 2° challenge.

Groups of wt and IL-15KO mice were immunized with Pb γ-spz or immunized and challenged as described in the legend for Fig. 3. BrdU was given to mice in drinking water for 7 days prior to analysis as described in Materials and Methods section. Results in (A) and (B) show gating strategy of liver CD3+CD8 T cells that express CD44 and CD45RB phenotype and are BrdU+ (A) wt and (B) IL-15KO mice. The numbers within each panel show the percentage of the indicated CD8 T cell phenotype. The results shown are from an analysis of liver CD8 T cells from a single mouse and are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Results show absolute numbers × 105 of BrdU+CD8 T cells and BrdU+CD8 T cell memory subsets from livers of wt and IL-15KO mice prior to 1° challenge (pre-challenge, i.e., ~7 days after the last immunization with Pb γ-spz) and 2° challenge (pre-re-challenge, i.e., ~60 days after 1° challenge) and are expressed as the mean ± SD of responses from 3–4 mice/group. The numbers in ( ) above each bar indicate the % of BrdU+ cells for each CD8 T cell population in wt and IL-15KO mice. (D) Results show absolute numbers × 105 of total CD8 T cells and CD8 T cell memory subsets from livers of wt and IL-15KO mice prior to 1° and 2° challenge and are expressed as the mean ± SD of responses from 3–4 mice/group. (E) Results show the % of total CD8 T cells, CD8 TE/EM and CD8 TCM cells remaining at time of 2° challenge. The percent of the remaining cells was calculated as follows: at 1° challenge, the number of total CD8 T cells and each of the CD8 T cell subset was considered as a 100% and the number of each of the respective CD8 T cells counted at 2° challenge was considered as a percent of the cells at 1° challenge, which is indicated by the black bars for wt mice and by the clear bars for IL-15KO mice, *p<0.05.

Despite the fact that the numbers of total BrdU+CD8 T cells as well as CD8 T cell memory subsets in IL-15KO mice represented approximately half of the respective BrdU+CD8 T cells in wt mice, the percentage of BrdU+CD8 T cells were remarkably similar between the two groups of mice at pre-challenge (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that an equivalent fraction of the respective CD8 T cell subset from each group proliferated similarly after immunizations with Pb γ-spz. Prior to 2° challenge (pre-rechallenge), considerably fewer BrdU+CD8 T cells, regardless of the phenotype, were detected in both wt and IL-15 deficient mice (Fig 5C) and this is in agreement with observations made in bacterial and viral systems (13). The percentages of BrdU+CD8 T cells also declined in both groups of mice, but the percentage of BrdU+CD8 T cells was higher in IL-15KO than in wt mice. This was particularly true for CD8 TCM cells, as ~52% of these cells were proliferating, presumably driven by cytokines other than IL-15 or possibly by the LS-Ag depot. This is worth noting because we recovered very few CD8 T cells from IL-15 deficient mice prior to 2° challenge (Fig. 5D). It is possible that the proliferating CD8 TCM cells were undergoing an accelerated attrition in the absence of the survival promoting IL-15 (11, 28), which ultimately led to a reduced number of cells in the memory pool, hence inability to confer protection upon re-challenge. Although results from other studies suggest that 2° memory responses are less sensitive to endogenous IL-15 (56), it appears that in the Pb γ-spz system, cellular turnover of secondary memory CD8 T cells is dependent, in part, on the provision of IL-15.

According to absolute cell counts of the liver CD3+CD8 T cells and the two CD8 T cell memory subsets, a significant cellular attrition did occur in both groups prior to 2° challenge (Fig. 5D). A >10 fold reduction in IL-15KO mice was quite striking in comparison to cellular loss in wt mice. To assess the relative loss of CD8 T cells in both the wt and IL-15KO mice during the interval between the challenges, we determined the percentages of the total liver CD3+CD8 T cells and the respective CD8 T cell subsets that remained in each group of mice at 2° challenge. Accordingly, 20% of total liver CD8 T cells remained in wt mice (80% loss) and 10% remained in IL-15 deficient mice (90% loss) (Fig. 5E). The most drastic attrition occurred within the CD8 TCM subset in IL-15KO mice as only ~1% cells remained in contrast to ~ 7% of CD8 TCM that remained in wt mice. Similar observations were made with regard to level of memory CD8 T cells that remained in wt mice with other infections (54, 57).

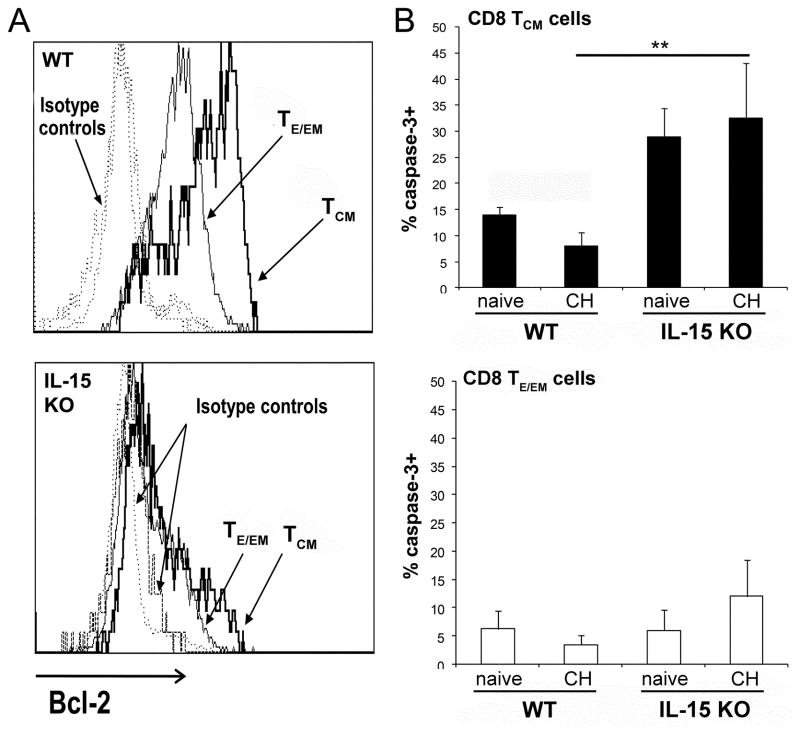

Decreased expression of anti-apoptotic molecules on CD8TCM in IL-15KO mice is responsible for decreased survival and lack of protection

Because the most severe attrition occurred within the CD8 TCM cell subset in IL-15KO mice prior to 2o challenge (2 months after the 1o challenge), we asked whether this cell loss could be explained by a reduced expression of anti-apoptotic proteins, e.g., Bcl-2. Prior to 2° challenge, CD8 TCM cells from wt mice expressed the highest level of Bcl-2; CD8 TE/EM cells also expressed a high level of Bcl-2 in comparison to naïve CD8 T cells and isotype controls (Fig 6A). Strikingly different results were observed from identically immunized and challenged IL-15 deficient mice, as Bcl-2 was down-regulated not only on CD8 TCM but also on CD8 TEM cells (Fig. 6A lower panel). Determinations of caspase-3 levels confirmed that the reduced levels of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 on IL-15KO CD8 T cell subsets related to the extensive apoptosis (Fig 6B). In comparison to caspase-3 levels on CD8 TCM in wt mice, significantly elevated levels (%) of caspase-3+ CD8 TCM cells were found in IL-15 deficient mice at 2 months after immunization/challenge (Fig 6B). Increased caspase-3+CD8 TCM were already found in naive IL-15KO mice as the absence of IL-15 could not support survival of these cells.

Figure 6. CD8 TCM cells from IL-15KO mice display reduced expression of anti-apoptotic molecules and increased cell death.

Liver CD8 TE/EM cells and CD8 TCM cells from Pb γ-spz immunized and challenged wt and IL-15KO mice (3 per group) were identified by flow cytometry as described in legend for figure 2 and were analyzed for the expression of (A) Bcl-2 two months after 1° challenge. The results shown represent one of two separate experiments. (B) IHMC were isolated 2 months after 1° challenge and stained with anti-CD8, -CD44 and -CD45RB mAbs, fixed, permeabilized and stained with mAbs against caspase-3. Naïve mice served as controls. The results, expressed as % caspase-3+ CD8 TCM cells and CD8 TE/EM cells in wt and IL-15KO mice, were determined for each individual mouse and are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 mice/group, **p<0.01. The results represent one of two experiments.

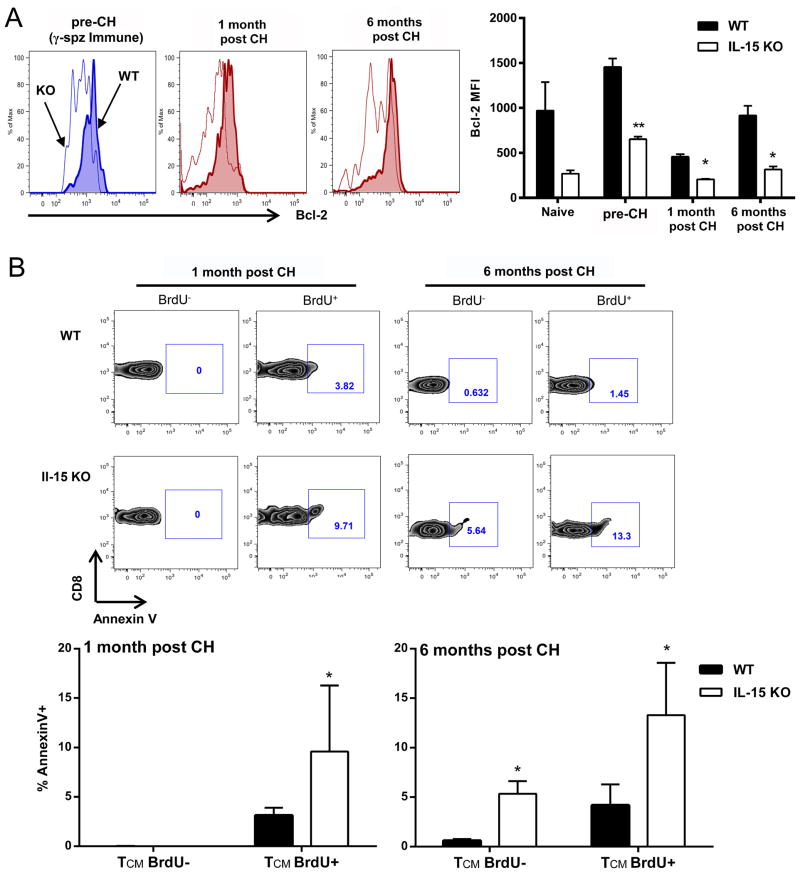

According to results shown in Fig. 5C, the percentage of BrdU+CD8 T cells, including CD8 TCM and CD8 TE/EM cells, were comparable in wt and IL-15KO mice prior to 1° challenge. Nonetheless, CD8 TCM underwent greater attrition in IL-15KO mice compared to wt, while CD8 TE/EM cells were comparable between the two strains of mice. In the next set of experiments we specifically evaluated proliferating, BrdU+CD8 TCM cells for both the expression of Bcl-2 and the level of apoptosis after Pb γ-spz immunization (prior to 1°challenge) and 1 month and 6 months after 1° challenge. BrdU+CD8 TCM cells from IL-15KO mice expressed significantly decreased levels (2–3 fold) of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 at all indicated time points relative to wt mice (Fig 7A). Similarly, IL-15KO BrdU+CD8 TCM cell populations also contained significantly greater percentage of annexinV+ staining cells than BrdU−CD8 TCM cells, indicating an increase in cell death within the proliferative subset at 1 month and 6 months after 1° challenge (Fig 7B). Although BrdU+CD8 TCM cells in wt mice also showed higher annexin V+ than BrdU−CD8TCM cells, the percentage was significantly lower than in IL-15KO mice (Fig. 7B). Additionally, BrdU+ CD8 TE/EM cells did not show significant differences between IL-15KO and wt in regards to the level of annexinV staining at any of the indicated time points (data not shown). Collectively, these results provide at least a partial explanation for the overall decreased number of CD8 TCM cells that remained in IL-15KO mice prior to 2° challenge.

Figure 7. Proliferating (BrdU+) cells in IL-15KO mice display an increase in cell death.

Wt or IL-15KO mice were immunized with Pb γ-spz and given 1° challenge as in legend for Fig. 4. Naive, Immune (pre-challenge), and 1 month or 6 months post challenge mice were fed BrdU in drinking water as described in the legend for Fig. 5, and CD8 TCM cells were gated based on CD3+CD8+CD44hiCD62L− phenotype. (A) Bcl-2 expression by proliferating (BrdU+) CD8 TCM cells at indicated time points. Data shown are from one representative mouse per group. Bar graph shows Bcl-2 MFI of BrdU+ CD8 TCM cells, represented as the mean ± SD for 3–5 mice/group. (B) AnnexinV expression by either proliferating (BrdU+) or non-proliferating (BrdU−) cells presented as %AnnexinV+. Representative flow plots are from one mouse per group, bar graph shows the mean ± SD of 5 mice/group, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

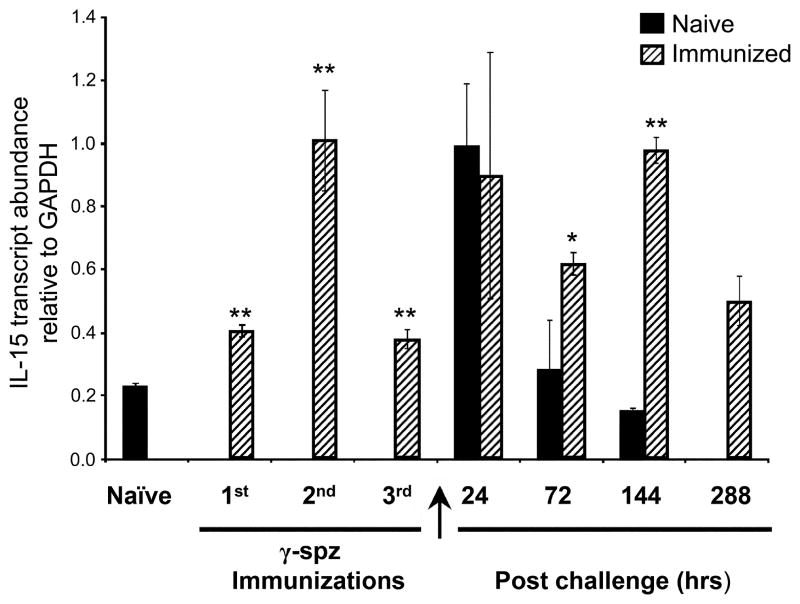

IL-15 is produced in a sustained manner in KC from mice immunized and challenged with Pb γ-spz

Because liver CD8 Tcells are a prominent cellular component in Pb γ-spz-induced protection, a question arose if the liver could be a source of IL-15 for the maintenance of memory CD8 T cells. IL-15 is produced by hepatocytes (58, 59) as well as by other cells in the liver, including KC (60). The precise involvement of KC in response to pre-erythrocytic stage Ags remains somewhat controversial (61, 62) and the role of KC in the maintenance of liver memory CD8 T cells has not been investigated. We hypothesized that if immunization with Pb γ-spz induces IL-15 in KC, these abundant liver macrophages could be involved in the maintenance of protracted protection. We determined the levels of IL-15 transcript in KC isolated at different time points during the immunization and challenge regimen with Pb sporozoites (Fig 8). Relative to KC from naïve mice, IL-15 transcripts increased in KC during immunization with Pb γ-spz. IL-15 transcripts increased in KC 24 hrs after challenge of both naïve and Pb γ-spz immune mice. However, while the IL-15 transcripts decreased to baseline in KC from naïve-infected mice, they remained elevated in KC for 288 hrs (12 days) post challenge of Pb γ-spz immunized mice (Fig 8). We have observed similar results at the IL-15 protein levels in liver CD11c+DCs (Dalai, manuscript in preparation). Although these results are not conclusive in regards to the role of KC in maintaining memory liver CD8 T cells, nor do they suggest the only source of IL-15 for memory CD8 T cells, they strongly suggest that apart from liver CD11c+DCs, KC provide IL-15 needed for protracted protection induced by Pb γ-spz.

Figure 8. Kupffer cells are a source of IL-15 in the liver.

IHMC were isolated from livers of naïve, Pb γ-spz immunized and immunized/challenge mice at the indicated time points. Mac3+ KC were isolated as described in Materials and Methods section and were lysed in TRIzol for RNA isolation and subsequently reverse transcribed for RT-PCR assay. Assays were done on a 96-well plate format and the detection of the PCR products was performed as described in the Materials and Methods section. Quantitative IL-15 gene expression is shown as a ratio of IL-15 to GapDH for each time point and results are expressed as the mean ±SD of triplicate wells. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Similar results were observed in thrice performed experiments.

Discussion

In this study we demonstrate that the presence of liver memory CD8 T cells correlates with maintaining protracted protective immunity induced by immunization with Pb γ-spz. Because CD8 TCM cells depend on IL-15 for proliferation (11, 27), effector function (42), and survival (28, 63), we tested the contribution of CD8 TCM cells to protection in IL-15KO mice. Despite reduced numbers of CD8 T cells, IL-15KO mice respond to a large spectrum of Ags and infectious agents (13, 14, 16, 17, 64). Here we expanded this list by adding responses to Pb pre-erythrocytic or LS-Ag. The activation of Ag-specific effector CD8 T cells was further confirmed by sterile protection of IL-15KO mice at 1° challenge. Of note, and as shown previously in wt mice (3, 45), protection in IL-15KO mice was mainly CD8 T cell-dependent; neither NK nor NK1.1+ T cells affected the outcome of protection at 1° challenge. Liver CD4 T cells appeared not to play a role in the IL-15 impact on duration of protection. The key observation that emerged from this study, however, was that unlike wt mice, the majority of IL-15KO mice succumbed to blood stage parasitemia at 2° challenge because they were unable to develop and/or maintain secondary memory CD8 T cell responses. The ability of IL-15KO mice to manifest only short-term protection underscores the differences in the requirements for the induction and maintenance of sterile immunity specific for LS-Ags in the Pb γ-spz model; maintenance, but not induction, of protection was IL-15-dependent.

Memory CD8 T cells play a crucial role in lasting protection

The failure to maintain sterile protection in IL-15KO mice against 2° sporozoite challenge was clearly linked to the dependence of memory CD8 T cells on IL-15 and immunologic deficits caused by the lack of IL-15 became evident during 2° challenge of previously protected mice. In comparison to wt mice, IL-15KO mice had lower numbers of IFN-γ-producing CD8 T cells, reduced basal proliferation, as well as fewer cells transiting from a central/long-term memory phenotype to an effector phenotype. The essentiality of IL-15, however, was apparent mainly in the inability of CD8 TCM cells to survive in IL-15KO mice. Survival is critical for the maintenance of adequate CD8 T cell numbers to combat parasites at re-challenge. In malaria, these numbers have been shown to be exceedingly higher than in other infections (65). Consequently, long-term protection was not sustainable in the absence of IL-15.

We propose that CD8 TCM cells represent a key cellular element required for long-term protection against the pre-erythrocytic stage of infection and perhaps malaria infection, in general. The dependence on CD8 TCM cells rather than CD8 TE cells or CD8 TEM cells for lasting protection has been demonstrated in other systems, including acute viral and bacterial infections(40, 41), as well as another protozoan parasite, Trypanosome cruzi (66). IL-15 is also critical for sustaining protective responses to vaccinia (67) and Toxoplasma gondii (16), as memory CD8 T cells are impaired and they gradually decline in numbers owing to a decrease in replication in the absence of IL-15. Although IL-15 has been shown to support early control and resolution of blood-stage parasites (68), to our knowledge, our study is the first demonstration of an important role of IL-15 in maintaining CD8 TCM cells required for protracted protection in the Plasmodia γ-spz model, which is considered to be the gold standard of anti-malaria vaccines.

Lasting protection requires a reservoir of CD8 TCM cells ready to combat the parasite

We previously hypothesized (18) that in the Pb γ-spz model of protection, CD8 TCM cells form a memory reservoir, which assures a quick differentiation of memory into effector cells upon reinfections. The memory reservoir is likely composed of CD8 T cells that avoid becoming effectors upon activation with LS-Ags during repeated immunizations with Pb γ-spz and CD8 TE cells that survive the contraction phase after sporozoite challenge and then transition to CD8 TCM cell pool where they are capable of replicating. CD8 TCM cells did indeed increase in both groups, but the increase in IL-15KO mice was to a lesser extent during immunizations with Pb γ-spz. After the primarychallenge, liver CD8 T cells declined in both wt and IL-15KO mice, but again the loss was particularly evident amongst CD8 TCM cells in IL-15KO mice. Similar to results from other systems (57), approximately 7% of CD8 TCM cells survived in wt mice, while only ~1% of CD8 TCM cells were found in the memory compartment in IL-15KO mice prior to 2° challenge. This suggests that a near absence of the surviving CD8 T cells limited the number of cells entering into the CD8 TCM reservoir. Because IL-15 enhances survival of CD8 T cells during the contraction phase (9, 29), thus assuring the formation of durable CD8 TCM compartment, our results suggest that the unavailability of IL-15 (in IL-15KO mice) during the contraction phase resulted in a severe loss of cells otherwise destined to form the memory reservoir.

IL-15 is needed for the conversion of memory to effector function during secondary challenge

The significantly reduced memory pool explains in part the inadequate differentiation of memory CD8 T cells into IFN-γ-producing CD8 TE cells at re-challenge. Although soon (6hrs) after re-challenge, IFN-γ-producing cells increased in wt and IL-15KO mice, the responses remained at a plateau in IL-15KO mice during subsequent time points, whereas in wt mice the responses continued to climb. These observations are in agreement with the findings from separate experiments showing that the transition of CD127hiCD8 TCM cells to CD127loCD8 TE cells diminished at 2°challenge in IL-15KO mice relative to wt mice. Together, these results support the involvement of IL-15 in conditioning differentiation of CD8 T cells into an effector population, and they are consistent with the observation that IL-15 promotes the conversion of CD127hi to CD127lo populations (20) and impacts the composition and function of CD8 T cells at 2° memory stage(13)

The high percentage of BrdU+ CD8 TCM cells that became evident in IL-15KO mice at 2° challenge was in stark contrast to rather low cell numbers of each phenotype in IL-15KO. Although this difference could be indicative of a difference in the rate of CD8 T cell division between these two groups of mice, it most likely resulted from increased apoptosis of CD8 T cells in IL-15KO mice. CD8 TCM displayed lower levels of Bcl-2 and increased caspase 3 and annexinV at 2° challenge of IL-15KO mice relative to wt mice. The preferential survival enhancing effects of IL-15 on CD8 TCM cells were confirmed by results from in vitro studies. Thus, despite the apparently proportional cellular turnover in wt and IL-15KO mice, many more dividing cells underwent apoptosis in the latter group. Although other cytokines, e.g., IL-7, have been shown to exert a dominant effect over IL-15 in enhancing memory cell formation amongst recently activated CD8 T cells (57), it appears that memory CD8 TCM cells that arise to Pb LS-Ags are extremely IL-15 sensitive particularly during the formation and/or maintenance of 2° memory cells. Our observation is in contrast to reports from other systems where 2° memory is less dependent on IL-15 than 1° memory CD8 T cells (56); however, our observations are in agreement that IL-15 still affected the composition of memory CD8 T cell pool (13). Neither of the γ-chain cytokines that are presumed to have been active in IL-15KO mice was sufficient to compensate for IL-15 prior to 2° challenge.

IL-15 is dispensable for the induction of protection but not for its maintenance

In contrast to the immunologic impairment caused by the absence of IL-15 at 2° challenge, IL-15 seemed rather dispensable during the initial induction, differentiation and expansion of CD8 T cells in response to immunization with Pb γ-spz, including the 1° challenge. These observations are similar to those made in other systems where the absence of γ-chain cytokines does not affect the processes associated with the initial CD8 T cell expansion and differentiation (42). Instead, the accumulation of CD8 TE cells in lymphoid organs proceeds quite normally, as did the accumulation of CD8 TE/EM cells in the livers of IL-15KO mice immunized with Pb γ-spz. It is entirely possible, therefore, that in the absence of IL-15, other cytokines with functional activities similar to those of IL-15 substituted for the effectiveness of IL-15 and promoted both cellular proliferation and effector function during primary challenge.

The two cytokines that likely supported activation of CD8 T cells during the priming and boosting immunizations with Pb γ-spz were IL-7, known to act on naïve CD8 T cells (10) and IL-21, produced by CD4 T cells (69) that help CD8 T cells. The supporting action of these cytokines in IL-15KO mice may be considered as evident by the increase of CD8 TE/EM cells. It is clear that the Pb LS-Ag-induced initial expansion and acquisition of an effector function was independent of the signals provided by IL-15. We presume that the swiftness of the response observed at 6 hrs after the challenge combined with the overall magnitude of the response must have been sufficient to eliminate the pre-erythrocytic parasites and to prevent blood stage parasitemia.

Although the absence of IL-15 did not interfere with or prevent the induction of protective immunity delivered by CD8 T cells at 1° challenge in Pb γ-spz, the absence of other γ-chain cytokines does show an impairment of CD8 T cell survival early after infection (10). The differences in the need for a particular γ-chain cytokine over another, e.g., IL-7 vs. IL-15, may stem from the differences associated with the type of infectious agents, mode of delivery of infection, as well as homing or localization of the infectious agent to particular organ or tissue, where each γ-chain cytokine may have a unique pattern or even a level of expression.

Liver APC supports the induction and maintenance of CD8 T cells

According to recently published studies, non-lymphoid organs contain resident memory CD8 T cells that confer local lasting protection of infected extra-lymphoidal organs (70). It remains unknown whether memory CD8 T cells specific for Pb LS-Ags were induced in liver or whether early during the effector phase CD8 T cells migrated from lymphoid organs, as has been shown for P. yoelii CSP-specific CD8 T cells (43), and lodged in the liver where they formed a memory CD8 T cell pool, which is partly supported by the local availability of IL-15. Recently, it was also demonstrated that CD8 T cell survival during influenza infection is promoted in the lung by trans-presentation of IL-15 by pulmonary CD8α+DCs (71). On the basis of our published results, liver, but not splenic, CD11c+CD8α+DCs from Pb γ-spz-immunized/challenged mice activate CD8 T cells to express CD44hi in a MHC-class I dependent manner; CD11c+DC also up-regulate IL-15 mRNA (72) and expressed detectable IL-15 protein (Dalai, unpublished). KC, the major liver macrophages, also up-regulate MHC class I molecules, secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (26), and, as shown here, maintained up-regulated IL-15 mRNA transcripts, but only after Pb γ-spz immunization and challenge. The issue of LS-Ag processing and presentation as well as the various signals needed for the survival of memory CD8 T cells remain to be sorted out in future studies. According to our collective results, however, we would like to suggest that in the Pb γ-spz model of protective immunity, liver KC and DCs function as APCs of LS-Ags and as IL-15 producers that target only liver CD8 TCM cells because CD8 TE/EM were not responsive to IL-15. Similar observations were made in in vitro studies where only CD8 TCM cells require trans-presentation of IL-15 in the context of a concurrent signaling via TCR for optimal recall response, as responses by CD8 TEM cells are not augmented by IL-15 (55). It could be envisaged, therefore, that TCR signal is delivered by MHC:peptide complex presented by KC or liver DC that hold the potential repository of LS-Ag depot, which is also needed for the maintenance of lasting protection in Pb γ-spz model (3, 39).

In summary, the general cellular dis-regulations caused by the absence of IL-15 contributed to the severely reduced CD8 TCM cell reservoir, which is critical for the maintenance of protective immunity induced with Pb γ-spz against homologous re-infections. IL-15 was crucial for the maintenance, but not for the induction, of protection as IL-15KO mice showed sterile protection at 1°challenge. The need for IL-15 in the maintenance of lasting protection to protozoan infection has been controversial; but, the majority of studies clearly demonstrate that memory CD8 T cells are exclusively IL-15-dependent (11, 13, 14, 27, 42, 56, 73). IL-15 extends the lifespan of CD8 TCM cells and hence, protective immunity. Our observations are in agreement with those that support models of IL-15 as the critical signal for the expansion, survival and thus long-term maintenance of the CD8 TCM cell pool.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the past and present Krzych Lab members for assistance in performing experiments that are part of this study and for assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- γ-spz

radiation attenuated sporozoites

- Pb

Plasmodium berghei

- TE/EM

effector/effector memory T cell

- TCM

central memory T cell

- TE

effector T cell

- MPEC

memory potential effector cell

- SLEC

short-lived effector cell

- IHMC

intrahepatic mononuclear cells

- NMS

normal mouse serum

- 3H-TdR

Tridiated thymidine

- CSP

circumsporozoite protein

- LS

liver stage

- wt

wild-type

- KC

Kupffer cell

Footnotes

The work was supported in part by a grant NIH AI 46438(UK) and by US Army Materiel Command.

The views of the authors do not purport to reflect the position of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.

References

- 1.Ahmed R, Gray D. Immunological memory and protective immunity: understanding their relation. Science. 1996;272:54–60. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murali-Krishna K, Lau LL, Sambhara S, Lemonnier F, Altman J, Ahmed R. Persistence of memory CD8 T cells in MHC class I-deficient mice. Science. 1999;286:1377–1381. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berenzon D, Schwenk RJ, Letellier L, Guebre-Xabier M, Williams J, Krzych U. Protracted protection to Plasmodium berghei malaria is linked to functionally and phenotypically heterogeneous liver memory CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:2024–2034. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zammit DJ, Turner DL, Klonowski KD, Lefrancois L, Cauley LS. Residual antigen presentation after influenza virus infection affects CD8 T cell activation and migration. Immunity. 2006;24:439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suresh M, Whitmire JK, Harrington LE, Larsen CP, Pearson TC, Altman JD, Ahmed R. Role of CD28-B7 interactions in generation and maintenance of CD8 T cell memory. J Immunol. 2001;167:5565–5573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopf M, Ruedl C, Schmitz N, Gallimore A, Lefrang K, Ecabert B, Odermatt B, Bachmann MF. OX40-deficient mice are defective in Th cell proliferation but are competent in generating B cell and CTL Responses after virus infection. Immunity. 1999;11:699–708. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salek-Ardakani S, Moutaftsi M, Crotty S, Sette A, Croft M. OX40 drives protective vaccinia virus-specific CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:7969–7976. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mescher MF, Curtsinger JM, Agarwal P, Casey KA, Gerner M, Hammerbeck CD, Popescu F, Xiao Z. Signals required for programming effector and memory development by CD8+ T cells. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubinstein MP, Lind NA, Purton JF, Filippou P, Best JA, McGhee PA, Surh CD, Goldrath AW. IL-7 and IL-15 differentially regulate CD8+ T-cell subsets during contraction of the immune response. Blood. 2008;112:3704–3712. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-160945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schluns KS, Kieper WC, Jameson SC, Lefrancois L. Interleukin-7 mediates the homeostasis of naive and memory CD8 T cells in vivo. Nature immunology. 2000;1:426–432. doi: 10.1038/80868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Judge AD, Zhang X, Fujii H, Surh CD, Sprent J. Interleukin 15 controls both proliferation and survival of a subset of memory-phenotype CD8(+) T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;196:935–946. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surh CD, Boyman O, Purton JF, Sprent J. Homeostasis of memory T cells. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:154–163. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandau MM, Kohlmeier JE, Woodland DL, Jameson SC. IL-15 regulates both quantitative and qualitative features of the memory CD8 T cell pool. J Immunol. 2010;184:35–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker TC, Wherry EJ, Boone D, Murali-Krishna K, Antia R, Ma A, Ahmed R. Interleukin 15 is required for proliferative renewal of virus-specific memory CD8 T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1541–1548. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy MK, Glaccum M, Brown SN, Butz EA, Viney JL, Embers M, Matsuki N, Charrier K, Sedger L, Willis CR, Brasel K, Morrissey PJ, Stocking K, Schuh JC, Joyce S, Peschon JJ. Reversible defects in natural killer and memory CD8 T cell lineages in interleukin 15-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2000;191:771–780. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan IA, Casciotti L. IL-15 prolongs the duration of CD8+ T cell-mediated immunity in mice infected with a vaccine strain of Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 1999;163:4503–4509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lieberman LA, Villegas EN, Hunter CA. Interleukin-15-deficient mice develop protective immunity to Toxoplasma gondii. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6729–6732. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6729-6732.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krzych U, Schwenk J. The dissection of CD8 T cells during liver-stage infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;297:1–24. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29967-x_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Obar JJ, Lefrancois L. Early signals during CD8 T cell priming regulate the generation of central memory cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:263–272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joshi NS, Cui W, Chandele A, Lee HK, Urso DR, Hagman J, Gapin L, Kaech SM. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8(+) T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sprent J. Turnover of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells. Microbes and infection/Institut Pasteur. 2003;5:227–231. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lumsden JM, Schwenk RJ, Rein LE, Moris P, Janssens M, Ofori-Anyinam O, Cohen J, Kester KE, Heppner DG, Krzych U. Protective immunity induced with the RTS, S/AS vaccine is associated with IL-2 and TNF-alpha producing effector and central memory CD4 T cells. PloS one. 2011;6:e20775. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lanar DE. Sequence of the circumsporozoite gene of Plasmodium berghei ANKA clone and NK65 strain. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;39:151–153. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90018-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lian ZX, Okada T, He XS, Kita H, Liu YJ, Ansari AA, Kikuchi K, Ikehara S, Gershwin ME. Heterogeneity of dendritic cells in the mouse liver: identification and characterization of four distinct populations. J Immunol. 2003;170:2323–2330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cauley LS, Cookenham T, Hogan RJ, Crowe SR, Woodland DL. Renewal of peripheral CD8+ memory T cells during secondary viral infection of antibody-sufficient mice. J Immunol. 2003;170:5597–5606. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steers N, Schwenk R, Bacon DJ, Berenzon D, Williams J, Krzych U. The immune status of Kupffer cells profoundly influences their responses to infectious Plasmodium berghei sporozoites. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2335–2346. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldrath AW, Sivakumar PV, Glaccum M, Kennedy MK, Bevan MJ, Benoist C, Mathis D, Butz EA. Cytokine requirements for acute and Basal homeostatic proliferation of naive and memory CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1515–1522. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berard M, Brandt K, Bulfone-Paus S, Tough DF. IL-15 promotes the survival of naive and memory phenotype CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:5018–5026. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yajima T, Yoshihara K, Nakazato K, Kumabe S, Koyasu S, Sad S, Shen H, Kuwano H, Yoshikai Y. IL-15 regulates CD8+ T cell contraction during primary infection. J Immunol. 2006;176:507–515. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romero P, Maryanski JL, Corradin G, Nussenzweig RS, Nussenzweig V, Zavala F. Cloned cytotoxic T cells recognize an epitope in the circumsporozoite protein and protect against malaria. Nature. 1989;341:323–326. doi: 10.1038/341323a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egan JE, Hoffman SL, Haynes JD, Sadoff JC, Schneider I, Grau GE, Hollingdale MR, Ballou WR, Gordon DM. Humoral immune responses in volunteers immunized with irradiated Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:166–173. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar KA, Sano G, Boscardin S, Nussenzweig RS, Nussenzweig MC, Zavala F, Nussenzweig V. The circumsporozoite protein is an immunodominant protective antigen in irradiated sporozoites. Nature. 2006;444:937–940. doi: 10.1038/nature05361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt NW, Podyminogin RL, Butler NS, Badovinac VP, Tucker BJ, Bahjat KS, Lauer P, Reyes-Sandoval A, Hutchings CL, Moore AC, Gilbert SC, Hill AV, Bartholomay LC, Harty JT. Memory CD8 T cell responses exceeding a large but definable threshold provide long-term immunity to malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14017–14022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805452105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krzych U, Lyon JA, Jareed T, Schneider I, Hollingdale MR, Gordon DM, Ballou WR. T lymphocytes from volunteers immunized with irradiated Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites recognize liver and blood stage malaria antigens. J Immunol. 1995;155:4072–4077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]