Abstract

The culture of pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) is focused on curative or life-prolonging treatments for seriously ill children. We present empirically-based approaches to family-centered palliative care that can be applied in PICUs. Palliative care in these settings is framed by larger issues related to the context of care in PICUs, the stressors experienced by families, and challenges to palliative care philosophy within this environment. Innovations from research on family-centered communication practices in adult ICU settings provide a framework for development of palliative care in PICUs and suggest avenues for social work support of critically ill children and their families.

Keywords: communication, end-of-life care, family-centered practice, palliative care, pediatric intensive care units

Historically, the goal of patient care in pediatric intensive care units (PICU)1 has been to do everything medically possible to cure a child's illness or prolong life. Childhood deaths are decreasing in the United States, with 53,552 deaths or 2.2% among children aged 0–19 years in 2005, which is significantly less than in 2000 (Martin et al., 2008). Yet, for some seriously or terminally ill children, the curative focus of the PICU will not prevent death. Pediatric deaths most typically are a result of congenital birth defects, cancers, traumatic injuries, and genetic or neurological disorders (Sands, Manning, Vyas, & Rashid, 2009). When curative therapies are no longer appropriate, or in cases where the outcome for seriously ill children is highly uncertain but could realistically end in death, PICU staff members face a transition in care to one that addresses the end-of-life issues. They must prioritize the physical and emotional comfort of the child and family while balancing continued treatment intended to prolong life (Friebert, 2009). In many cases, this transition, if it happens at all, comes very late in the trajectory of a child's serious illness and often only after every possible medical intervention has been pursued at length (Carter, Hubble, & Weise, 2006). The desire to continue aggressive care is supported by clinicians and families alike, especially when intensive interventions sometimes do succeed and offer a reason to invest in the hope and possibility of continued therapy (Byrne et al., 2011).

In the fast-paced, aggressive, care-focused environment of the PICU, the initiation and delivery of palliative care has unique challenges that require effective communication between the family and the health care team about their collective understanding of the possibilities for intervention, the likely and desired outcomes given the child's illness and capacities, and the goals of care for the child and family (Hays et al., 2006). Because of competing demands that keep the focus of care on the diagnosis and treatment of the child's illness, the in-depth assessment of the child and family's beliefs, values, and understanding of the medical implications of the illness or condition is often not the main concern within the context of the highly technological and procedure-focused environment of the PICU. Social workers can be key players in facilitating communication because of their training in culturally sensitive assessment, expertise in interaction and group process, life course development, family systems and dynamics theories, and their role as liaisons between clinicians and families (Fineberg, 2010). The purpose of this article is to provide information on empirically based approaches to family-centered palliative care which can be applied in a PICU setting. Any effort to introduce palliative care into PICUs is framed by larger issues related to the context of care in these units, the stresses experienced by families with a critically ill child, and the challenges to palliative care within this environment. Recent innovations from research on family-centered communication practices in adult ICU settings provide a framework for further development of palliative care in pediatric intensive care, and suggest avenues for social work support of critically ill children and their families.

THE CONTEXT OF CARE IN PEDIATRIC INTENSIVE CARE UNITS

Every year at least 200 children per 100,000 require hospitalization in PICUs because of serious illness (Shudy et al., 2006). Approximately 90% of pediatric deaths in the hospital occur in neonatal and pediatric intensive care units (Carter et al., 2004; Field & Behrman, 2003). These settings are characterized by their intensive technological focus on life-saving procedures such as the use of mechanical breathing assistance (ventilation), intensive intravenous (IV) administration of medications, and artificial hydration and nutrition supplementation. Most deaths in the PICU are preceded by withdrawal of life-prolonging medical therapy, most typically mechanical ventilation (Sands et al., 2009; Shudy et al. 2006), the removal of these can result in death from respiratory arrest within moments to hours.

In addition to the medical acuity of the children seen in PICU settings, the organization of care in these units is also complex, especially from a family's perspective. Families and patients in these settings interact with multiple professional caregivers including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, nutrition-ists, child life specialists, respiratory therapists, social workers and depending on the child's condition, specialists from medical disciplines such as nephrology, cardiology, pulmonology, and oncology. Many PICUs are located in teaching hospitals where in addition to attending physicians, families may also encounter residents and fellows who rotate through the unit on a weekly or monthly basis. In the course of a 24-hour period, families may interact with dozens of medical professionals each of whom has some responsibility for the care of their child. They then may encounter a substantially new set of caregivers the next day. Care may not be well coordinated among these multiple services and disciplines and communication may be fragmented, thus affecting the family's ability to access appropriate information and to make informed decisions regarding the care of their child.

While daily rounds in which the interdisciplinary professional team discusses the medical indications for treatment of the child are routine in PICUs, these conversations may or may not include family members. Even when family members are physically present, the usual purpose of the rounds is to review highly technical medical findings that are typically outside of most family members’ understanding. Rarely are families invited into the conversation or given explanations about what each lab value, medication, or machine setting indicates. As a result, families often face challenges in obtaining information about their child's condition and care needs that is understandable to them. This difficulty becomes even more pronounced when medical teams are caring for children and families with limited English language skills. When interpreters are available, they usually have to be requested in advance, so emergent changes in a child's condition may not be communicated to family members.

In response to efforts to improve care in PICUs, several changes have been recommended to include families more directly in the care of their children, drawing on practice principles derived from models of “family-centered care,” which is broadly focused on building partnerships between families and health care providers when caring for critically ill patients (Cooley, 2001; Frazier, Frazier, & Warren, 2009; Johnson, 2000; Johnson & Eichner, 2003; National Association of Children's Hospitals and Related Institutions [NACHRI], 2009). Truog, Meyer, and Burns (2006) have identified six domains that are central to family-centered care: (a) support of the family unit; (b) communication with the child and family about treatment goals and plans; (c) ethics and shared decision making; (d) relief of pain and other symptoms; (e) continuity of care; and (f) grief and bereavement support. A family-centered approach requires a core commitment to including patients and families as respected members of the health care team, and communicating with them in ways which elicit patient and family values, needs, and preferences (Frazier et al., 2009). For example, in response to parental concerns to have ongoing access to their child, many units have made provisions for parents to “room in” with their children in a more aesthetically appealing environment, rather than allowing only brief visitations each hour. These rooming-in arrangements support positive attachment and provide emotional security for the child. Rooming in can reduce the stress of travel for the parent and the stress of the hospital stay for the child and parent. Also, research suggests that such arrangements in pediatric care units can reduce parental stress caused by changes in the parental role that can occur during pediatric hospitalizations (Smith, Hefley, & Anand, 2007).

The Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) has developed clinical practice guidelines for the support of the patients and families in adult, pediatric, and neonatal ICUs (Davidson et al., 2007). These evidence-based guidelines address family psychosocial needs by recommending shared decision making; routine care conferences with families to explain the patient's medical condition and determine mutually agreed upon goals of care; cultural and spiritual support for patient and family; and family support before, during, and after a death. These guidelines recognize the need for interprofessional practice, and highlight the role that social workers can play in each of these areas. Yet, as discussed below, changing ICU practice remains an ongoing challenge despite advances in the recognition of the importance of family-centered care (Balluffi et al., 2004; Contro, Larson, Scofield, Sourkes, & Cohen, 2002; Carlet et al., 2004).

STRESSORS FOR FAMILIES WITH A CRITICALLY ILL CHILD

The serious illness and death of a child is one of the most disruptive events in a family's life experience, especially when the family is raising young children (Hooyman & Kramer, 2006). Research has documented that parents often have intense grief after the death of a child. Death in the PICU is often unexpected by parents who are hoping for recovery with use of aggressive therapies (Meert, Thurston, & Thomas, 2001). Complicated grief was found in 59% of parents whose child had died in the PICU, 6 months after the death (Meert et al., 2010). The majority of parents (74%) report having experienced some resolution of their grief after the death of a child (Kreicbergs et al., 2007); however, parents with unresolved grief reported significantly worsening psychological health and physical health compared with those who have experienced some resolution of their grief (Lannen, Wolfe, Prigerson, Onelov, & Kreicbergs, 2008). Parental stress may also limit the emotional and physical availability of parents for other children in the home, particularly in response to sibling fears, concerns, and anxieties. For example, the more depressed or distressed the parent in dealing with the serious illness of a child, the less able the parent will be to act as a buffer for siblings; in such circumstances, the sibling may refrain from disclosing to parents or revealing emotions out of a strong desire not to burden other family members or add to others’ distress (Aisenberg, 2006).

Parents not only are caregivers for their children, but also are “second-order patients” themselves who require attention from PICU staff (Rait & Lederberg, 1989). The PICU is an emotionally charged environment that places major demands on patients and family caregivers and can have negative effects on their short- and long-term psychosocial outcomes (Azoulay et al., 2001; Board & Ryan-Wenger, 2002; Contro et al., 2002; Meert et al., 2001; Studdert et al., 2003). For example, Balluffi and colleagues (2004) assessed the prevalence of two anxiety disorders among parents caring for a child in a PICU. During the initial period of the PICU admission, about one third of the parents met symptom criteria for Acute Stress Disorder (ASD). Four months after the PICU discharge, 21% of parents met symptom criteria for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Nearly all parents experienced one or more of four types of symptoms associated with PTSD—including feelings of dissociation, re-experiencing the stressful event, avoidance of the stressful event, or hyper-arousal. ASD rates were higher among parents who worried their child might die and for whom the admission was unexpected (Balluffi et al., 2004), both of which are characteristic of children who may benefit from palliative care consultation.

Adding another layer of stress for parents are the conflicts that can arise regarding care decisions in the PICU. These decisions are typically made by parents because their children are cognitively and/or legally not able to make autonomous choices about the kind of care they receive. This structural difference between adult and pediatric care requires that communication in a pediatric environment be focused on family system functioning, not just the desires and goals of the patient. Perception of support is a key determinant in psychosocial outcomes for parents—including support given by clinicians (Melnyk, Feinstein, & Fairbanks, 2006; Truog et al., 2006), PICU and other hospital staff, and family or friends (Briller, Meert, Schim, Thurston, & Kabel, 2009; Meert, Briller, Thurston, & Schim, 2008). However, in the only study specifically focused on the PICU setting, Studdert and colleagues (2003) found serious disagreements in over one-half of the cases where children spent more than eight days in intensive care. Conflicts between the medical team and family were the most common (60%) and were associated with poor communication (48%); unavailability of a parent/guardian (39%); disagreements over the child's care plan (39%); coping problems (21%); dys-functional families (12%); conflicts about decision making (9%); and young parents (6%). Intrateam conflicts were also present in over one third of cases, but intrafamily conflict was rare, occurring in only 2% of families, and most often associated with a disagreement over the care plan. Where there is conflict between staff and families, ethics consultations have been shown to be beneficial in adult environments (Schneiderman et al., 2003).

The needs of families may not be recognized by the physicians charged with the care of seriously ill children because of different perspectives regarding which processes and outcomes are most important in PICU care. For example, one study found that families valued clear communication and compassionate support at the end of life more than pain management or length of stay; however, physicians prioritized technical aspects of pain management and length of stay as the most important factors (Mack et al., 2005). Meyer, Burns, Griffith, and Truog (2002) reported that over half of families in the PICU considered the possibility of withdrawing life-prolonging interventions before any such discussions were initiated by the medical team, and up to 25% of parents reported that, in retrospect, they would have made decisions differently than those that were recommended by staff concerning their child's care. Unfortunately, because of the power differentials and structures of the PICU settings, families remain at a disadvantage in negotiating care in the PICU. The PICU is still a very technologically focused environment and has yet to become a family-friendly place despite a decade of study and dissemination of the concept of family-centered care in pediatrics. In this context, social workers can exercise crucial leadership to facilitate and enhance communication between parents and members of the medical team. Trained in addressing crisis and loss, social workers can also facilitate communication across the multiple services and members of the interdisciplinary palliative care team that are engaged in the care of the hospitalized child.

PALLIATIVE CARE AT END OF LIFE IN THE PICU

The goal of palliative care is to improve quality of life by relieving pain and other distressing symptoms for patients and families facing life-threatening illness (World Health Organization, 2010) and to assist patients and families in decision making about end-of-life care. Palliative care is family-centered support that includes physical, emotional, and spiritual comfort which is best provided by a multidisciplinary team that includes social workers, physicians, nurses, chaplains, and other health care professionals (Friedman, Hilden & Powaski, 2005; Teno et al., 2004). Patients are typically eligible for palliative care services from the time of diagnosis through death and into bereavement (Field & Behrman, 2003; Friedman et al., 2005); thus the mission of and services offered by palliative care can extend far beyond the typical 6-month prognosis used to determine eligibility for hospice by Medicare and most other private insurances in the United States. In addition, it is important to conceptualize palliative care as broader than end-of-life care. Although palliative care should be a component of end-of-life care, palliative care also includes care earlier in the disease trajectory focused on identifying the goals of care—including patient and family support for physical, emotional and spiritual issues that arise in the context of a potentially life-limiting illness (Curtis & Rubenfeld, 2005). Hospital-based palliative care teams often function in a more consultative role, especially for the critically ill, rather than directly providing ongoing nursing or other direct patient care services. However, some palliative care programs are integrated with hospice teams and more direct patient care is provided. During the past decade, pediatric palliative care teams have grown in number. Hospital-based pediatric palliative care teams deal with a greater diversity of medical conditions and duration of survival than palliative care teams caring for adult patients (Feudtner et al., 2011).

Both families and clinicians share the hope and expectation that ill or injured children will improve with aggressive care, so it is common that the unquestioned goal of care is to pursue every available option in the PICU. The desire to preserve and prolong life in the PICU has a heightened poignancy due the youth of the patients and the feeling that they have not yet had their lives to live. In this respect, the PICU may have a greater focus on cure in contrast to the more varied strategies and goals that might be considered for older adults in ICUs. As a result, palliative care in pediatric intensive care settings has been slower to develop than in adult ICUs where the patient mix often includes a substantial number of elderly adults who may be facing the end of life as a normal and expected part of the human life course. Barriers to good palliative care from family perspectives include a primary focus on curative treatments (Carter et al., 2006), dealing with a complex team of clinicians who are often not communicating consistent information, and the perception that decisions must be made quickly without enough time to absorb and act on changing situations (Briller et al., 2009).

Integrating palliative care into the PICU setting can be challenging for both logistical and provider-oriented reasons. Studies of death in PICUs suggest that even though some children are in the PICU for months, the median length of stay is around one week (Carter et al., 2004). Although one week is too short for optimal delivery of palliative care, even this short time can be used to incorporate palliative care consultation, particularly about goals of care and end-of-life decision making. However, children with serious chronic conditions may have multiple admissions to PICUs over the course of their illness. In these circumstances, families may benefit from palliative care that is offered in a more episodic fashion.

Communicating the prognosis of seriously or terminally ill children is a delicate process that can be more difficult in the milieu of the PICU. The uncertainty surrounding prognosis for many pediatric conditions poses another logistical issue in recognizing that end-of-life concerns should be addressed. For example, organ transplantation, an increasingly common category of ICU care, represents the entire spectrum of outcomes from full recovery to death. An infant in need of a heart transplant may die before the transplant can be obtained, or if a donor heart is found and transplanted successfully, the child may have a normal life expectancy. Many pediatric conditions have unclear trajectories, and given the focus on curative treatment, it can be difficult to raise the possibility of death when continued life and improved health are the hoped for outcomes (Byrne et al., 2011).

Health care professionals trained in critical or intensive care often feel personal discomfort when discussing quality-of-life or end-of-life issues and may therefore avoid or delay important conversations (Contro, Larson, Scofield, Sourkes, & Cohen, 2004; Hinds, Schum, Baker, & Wolfe, 2005). However, delaying such difficult conversations can result in missed opportunities for identification and resolution of emotional issues and for healing within the family (Hutton, 2002). The prevailing style of clinician communication to family members is typically a physiologic systems approach, focusing on ventilator settings, incremental changes in laboratory values, and other highly technical data. This approach usually does not directly address the child's chances for survival or future level of functioning. For example, 70% of families in one study felt they had been well-informed about their child's chances for survival (Meyer et al., 2002), yet only 14% of parents felt they had been adequately informed about their child's deteriorating physical condition as death approached (Davies & Connaughty, 2002). Frequently, PICU clinicians engage in frank discussions about prognosis only after they judge the future quality of life as unacceptable, at which point they use this information to suggest discontinuation of life-prolonging interventions (Meyer, Ritholz, Burns, & Truog, 2006).

Several studies have examined the health care providers’ comfort and confidence levels in providing pediatric palliative care in the PICU. In general, the staff of PICUs felt less comfortable providing psychosocial care compared to other aspects of care (Jones et al., 2007). Additionally, confidence in providing palliative care was significantly higher among physicians and nurses who had eight years or more of experience in the PICU (Jones et al., 2007). These findings suggest that palliative care conversations are difficult for the clinicians directly engaged in the care of critically ill children in pediatric intensive care settings. Social workers who have training in discussing uncomfortable issues can help initiate these conversations when they are aware that there is uncertainty about the child's potential for recovery.

INTEGRATING FAMILY-CENTERED COMMUNICATION INTO PICU SETTINGS

Excellent communication skills are essential in the PICU setting because of the high-stakes decisions; critical informational needs of families; and the numerous potential differences in cultural beliefs, understanding, values, and preferences between clinicians and families (Azoulay et al., 2001; Contro et al., 2002; Hinds et al., 2005; Meyer et al., 2006). Family-centered practice recommends that the appropriate role for family members for decision making about goals of care and discussion of end-of-life issues is generally that of shared decision making in concert with the clinicians (Carlet et al., 2004). However, it is important to realize that there is a spectrum of preferred decision-making roles for family members that can extend from decisions being made exclusively by family members on one end of the spectrum to families who would prefer to delegate decisions to clinicians on the other end (Heyland et al., 2003). Furthermore, research suggests that family members’ risk for psychological symptoms after a death in the ICU is higher if their preferred decision-making role does not match their actual decision-making role (Gries et al., 2010). Clinicians should develop skills to match the clinicians’ and families’ role with families’ needs and preferred role (Curtis & White, 2008; White, Malvar, Karr, Lo, & Curtis, 2010).

Parents have reported that they prefer for detailed medical information to be integrated into a larger context so that they can understand individual treatments, changes in status, and decision options within a “big picture” perspective of their child's overall care (Meyer et al., 2006). While clinical data are important, many families prioritize quality of life in their decision making. Unfortunately, quality of life issues are rarely addressed by providers until the child is in an acute crisis. A “take it as it comes” approach to discussing trajectories of illness may be the desired approach of some families, and may be necessary when the potential effects of treatment are difficult to predict (Byrne et al., 2011). In the absence of anticipatory guidance, families live without a full understanding of the possible choices they may have in response to acute episodes of chronic conditions. For example, with guidance, the family of a child with relapsed cancer, may be able to anticipate when hospitalizations are likely to occur and then plan family activities to maximize the child's experiences when she or he is home. Children and families might prioritize their quality of life at home over time in the hospital if they understood the prognosis and treatment options. However, in the absence of conversations about possible trajectories of the condition, planning is more difficult and decision making may happen in the context of a crisis, precisely when families would prefer it not to occur.

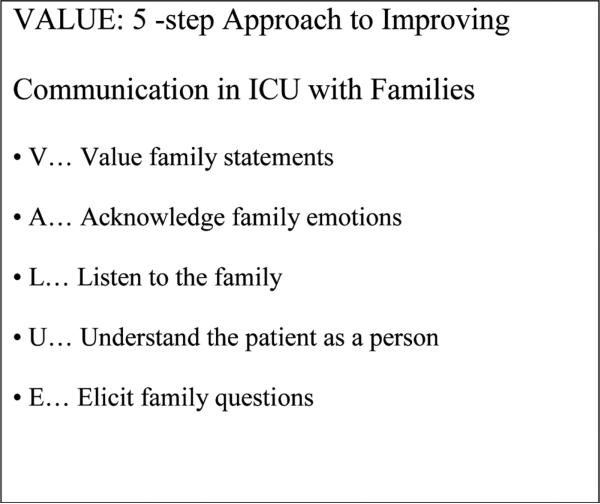

Studies from adult ICUs provide some insight into specific tools that may help clinicians improve communication with family members. One is the use of family care conferences to share information and determine the goals of care for the patient (Fineberg, Kawashima, & Asch, 2011). Care conferences can be formal meetings with agendas, or happen informally at the bedside of the patient. Typically, they cover content that is described in Table 1 and are usually led by a designated member, often the palliative care team member and/or the patient's primary physician. The format of these meetings usually includes preconference planning for the optimal use of the conference time; opening, information sharing, and moderation of discussion at the care conference; closing summary of important goals and decisions; and follow-up post-care conference to answer any emerging questions (Ambuel, 2000). Family care conferences offer the opportunity to “unpack” unfamiliar medical terms and diagnoses; for example, using the term “allow natural death” rather than “do not resuscitate” when suggesting not using extraordinary lifesaving measures (Jones et al., 2008). A skilled facilitator of these meetings will ensure not just that this information is provided by the medical team, but that the family can state their understanding in their own terms. The planning, facilitation, and follow-up to family care conferences enhance clinician-patient-family relationships, communication, and care coordination—which builds trust, the sense of being heard, and access to information and support (Meyer et al., 2006). When a standardized family conference was coupled with the use of the “VALUE” mnemonic for improving communication (see Figure 1), a randomized trial found that family members reported reduced symptoms of anxiety, depression, and PTSD (Lautrette et al., 2007).

TABLE 1.

Typical Information Shared in a Family Care Conference

| Introductions, reasons and goals for the conference | • Goals should be ascertained from both patient/family members and professional care providers |

| Medical condition | • Brief history • Current treatments • Current symptoms • Recent changes |

| Prognostic information | • Anticipated prognosis with and without disease-directed treatments • Likely level of functioning under each scenario |

| Patient/Family psychosocial information | • How patient and family define quality of life • Family communication dynamics • Current stressors • Developmental issues of patient and/or family |

| Decision making | • Obtain consensus on decisions to be made • Obtain consensus on treatment decisions • Anticipate future decisions that may need to be made |

Note. Adapted from Weissman, Quill, and Arnold (2010a, 2010b).

FIGURE 1.

VALUE Mnemonic for Improving Communication with Families (Reprinted with permission from Curtis & White, 2008).

Other studies have identified specific components of clinician communication that were related to enhanced family functioning—including having a private place for family communication, consistent communication by all members of the team (Pochard et al., 2001), and empathic statements by clinicians (Fineberg et al., 2011; Selph, Shiang, Engelberg, Curtis, & White, 2008). Research has demonstrated that physicians often talk the longest and are more likely to determine the topics covered in patient care conferences (Fine, Reid, Shengelia, & Adelman, 2010), yet families report more satisfaction when clinicians spend more time listening and less time talking (McDonagh et al., 2004). Other features of clinician communication associated with improved family experiences include assurances the patient will not be abandoned prior to death; that every effort will be made to treat physical, emotional, and spiritual suffering of the patient; and that family decisions are explicitly supported (Stapleton, Engelberg, Wenrich, Goss, & Curtis, 2006).

Communication interventions have reduced family stress in the ICU by addressing informational needs, providing emotional support, creating a collaborative environment for clinicians and families, and reducing the potential for conflict and misunderstanding (Burns et al., 2003; Curtis et al., 2005; Tulsky, 2005). Components of successful interventions include being proactive (Hays et al., 2006); being collaborative by bringing care teams and families together in facilitated care conferences (Curtis et al., 2005); and using a structured communication process to systematically discuss and document the patient's medical condition, the patient and family's preferences, definitions of quality of life, and any contextual factors that are important to decision making (Hays et al., 2006; Jonsen, Siegler, & Winslade, 2002). When implemented proactively, communication interventions empower families and create opportunities to exchange information and understanding about the medical circumstances, acknowledge and address family emotions, explore patient and family preferences, explain the process of decision making, and affirm nonabandonment by the clinical team (Hays et al., 2006; West, Engelberg, Wenrich, & Curtis, 2005).

IMPLICATIONS FOR SOCIAL WORK PRACTICE

Social workers have a crucial responsibility to facilitate the patient and family's understanding of the medical condition and the health care team's nonjudgmental understanding of the family within the pediatric intensive care setting. Social workers provide guidance to both the multidisciplinary team and to families on psychosocial, cultural, and spiritual issues. They facilitate communication between the multidisciplinary team and family; provide support and counseling to family members; obtain concrete financial resources; coordinate care delivery; and advocate for family's needs, choices, and desires (Jones et al., 2007). Social workers may also bear witness to suffering, provide spiritual support, pain and symptom management, and bereavement follow-up; and deal with ethical issues such as truth-telling and discontinuation of treatment (Browning, 2004; Csikai & Chaitin, 2006). Social work is well situated to provide a unique and essential contribution to the multidisciplinary pediatric palliative care team with its emphasis on fostering self-determination, empowerment, and social support (Raymer & Reese, 2004).

Social work education provides an excellent foundation for addressing complex family dynamics that may emerge as a result of the medical crisis, or be continuations of family problems or coping patterns that now intersect with the critical care decisions that have to be made for a seriously ill child. Information needs to be shared with the patient and family members according to their developmental ability and in age-appropriate terms (Christ, 2000). Children who have been told about the impending death of a loved one and who are encouraged to ask questions and express feelings cope more successfully and report fewer depressive symptoms than children without this knowledge and opportunity (Sahler, 2000). Conversely, withholding information or excluding children from discussions and preparations for these important life events in the name of “protection” can lead to adverse outcomes. For example, not including siblings in conversations about the medical condition of their ill sister or brother may further isolate well children and leave them to their own imaginations in which they experience exaggerated feelings or self-blame for events that are clearly outside their control (Aisenberg, 2006).

Social work's expertise in managing communication with culturally diverse groups is also an asset to palliative care in the PICU. While talking about one's problems may be understood as therapeutic in Euro-centric cultures, not all families may be comfortable sharing personal information or information about family members. Aisenberg (2006) notes, for example, that other-centered or “allocentric oriented cultures such as Latino and Asian/Pacific Islander cultures may have more boundaries around what is private information and what is community information in effort to save face” (p. 579). Cultural differences in health beliefs in terms of causes of conditions and where power for healing lies may also affect decision making and communication in pediatric intensive care settings (MacLachlan, 2007).

Organizationally, two approaches can be taken to strengthen social work's role in the provision of family-centered palliative care in PICUs (Meier & Beresford, 2008). First, PICU social workers can receive further training on how to integrate the precepts of palliative care into their practice. While Jones and colleagues (2007) found that social workers in PICUs felt well-prepared to counsel parents, provide emotional support, and facilitate access to medical information, they were less comfortable with discussions about the transition from curative to palliative care, advocacy around symptom management and pain control, and providing education about disease progression. Specialized mentoring and training for PICU social workers in palliative care philosophies and techniques could help unit social workers to recognize when palliative care is appropriate and provide guidance in its implementation. This approach may also help with continuity of care as families work with one social worker over the course of their hospitalization. A complementary strategy is to increase the presence of specialized palliative care programs within PICU settings. Social workers frequently serve as members of the multidisciplinary palliative care team, and can contribute specific expertise in family communication within the team and the PICU setting as well as among the medical team members themselves. Often palliative care services are staffed in such a way that allows smaller caseloads and more intensive family contact than may be possible for a PICU social worker who is responsible for all social work services on the unit (Meier & Beresford, 2008). The advantage of this approach is that social workers with specialized expertise can help families anticipate, recognize, and plan for changes that are associated with the worsening of the child's condition.

As palliative care has been most strongly developed in adult settings, it will be important for palliative care clinicians to become familiar with the differences that occur in pediatric settings. Unique psychosocial concerns and needs emerge for families when serious illness occurs in a life phase that is developmentally “off time,” especially where there is a need to discuss end-of-life concerns (Hooyman & Kramer, 2006). Children with potentially life-threatening conditions face highly uncertain clinical paths—sometimes their illness ends in death, but in other instances, full recovery may be possible (Byrne et al., 2011). Managing this degree of uncertainty in the context of differing developmental expectations differentiates pediatric palliative care from palliative care for elderly adults or adults with illnesses that have known trajectories. Social workers trained in empathic communication, systems theory, and family development are in a unique position to provide important leadership in promoting age-appropriate and family-centered communication and decision making.

CONCLUSIONS

Enhancement and integration of palliative care represents an important opportunity for improvement in the PICU. Integration of the principles and practice of palliative care into the pediatric ICU setting is an opportunity for incorporating family-centered care and enhancing communication between family members and the interdisciplinary clinical team. Social workers are some of the most highly trained professional in the PICU in the art and science of communication. Families value communication above all else when their child is critically ill (Meyer et al., 2002). Because of this, social workers are poised to excel as leaders in the adoption of palliative care in the PICU setting.

Footnotes

In hospitals which have intensive care units, these can focus on the general population, which includes the adult and pediatric population (ICUs), general pediatric care (PICUs), neonatal intensive care (NICUs), or cardiac care (CICUs). In this article, we will use the term PICU to refer to all three pediatric specific sites, understanding that there are some differences between the kinds of patients and structures found in each unit.

Contributor Information

ARDITH DOORENBOS, Department of Biobehavioral Nursing & Health Systems, School of Nursing, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

TARYN LINDHORST, School of Social Work, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

HELENE STARKS, Department of Bioethics and Humanities, School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

EUGENE AISENBERG, School of Social Work, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

J. RANDALL CURTIS, Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

ROSS HAYS, Center for Child Health, Behavior and Development, Seattle Children's Research Institute, and Department of Rehabilitative Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

REFERENCES

- Aisenberg E. Grief work with elementary and middle school students: Walking with hope when a child grieves. In: Franklin C, Harris MB, Allen-Meares P, editors. The school services sourcebook: A guide for social workers, counselors and mental health professionals. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 577–585. [Google Scholar]

- Ambuel B. Conducting a family conference. Principles & Practice of Supportive Oncology. 2000;3:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, Lemaire F, Mokhtari M, LeGall JR, French FAMIREA Group Meeting the needs of intensive care unit patient families: A multicenter study. American Journal of Respiratory Critical Care Medicine. 2001;163:135–139. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2005117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balluffi A, Kassam-Adams N, Kazak A, Tucker M, Dominguez T, Halfaer M. Traumatic stress in parents of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2004;5:547–553. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000137354.19807.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Board R, Ryan-Wenger N. Long-term effects of pediatric intensive care unit hospitalization on families with young children. Heart and Lung. 2002;31:53–66. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2002.121246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briller SH, Meert KL, Schim SM, Thurston C, Kabel A. Examining the needs of bereaved parents in the pediatric intensive care unit: A qualitative study. Death Studies. 2009;33:712–740. doi: 10.1080/07481180903070434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning D. Fragments of love: Explorations in the ethnography of suffering and professional caregiving. In: Berzoff J, Silverman PR, editors. Living with dying: A handbook for end-of-life healthcare practitioners. Columbia University Press; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Burns JP, Mello MM, Studdert DM, Puopolo AL, Truog RD, Brennan TA. Results of a clinical trial on care improvement for the critically ill. Critical Care Medicine. 2003;31:2107–2117. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000069732.65524.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne M, Tresgallo M, Saroyan J, Granowetter L, Valoy G, Schecter W. Qualitative analysis of consults by a pediatric advanced care team during its first year of service. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2011;28:109–117. doi: 10.1177/1049909110376626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlet J, Thijs LG, Antonelli M, Cassell J, Cox P, Hill N, Thompson BT. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU: Statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care: Brussels, Belgium, April 2003. Intensive Care Medicine. 2004;30:770–784. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BS, Howenstein M, Gilmer MJ, Throop P, France D, Whitlock J. Circumstances surrounding the deaths of hospitalized children: Opportunities for pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e361–e366. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0654-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BS, Hubble C, Weise KL. Palliative medicine in neonatal and pediatric intensive care. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2006;15:759–777. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ G. Healing children's grief: Surviving a parent's death from cancer. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen H. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:14–19. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen H. Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1248–1252. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0857-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley WC. Family-centered care in pediatric practice. In: Hoekelman RA, editor. Primary pediatric care. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 2001. pp. 712–714. [Google Scholar]

- Csikai EL, Chaitin E. Ethics in end-of-life decisions in social work practice. Lyceum Press; Chicago, IL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Rubenfeld GD. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the ICU. American Journal of Respiratory Critical Care Medicine. 2005;171:844–849. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JR, Rubenfeld GD. Improving palliative care for patients in the intensive care unit. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8:840–854. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JR, White DB. Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. Chest. 2008;134:835–843. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, Tieszen M, Kon AA, Shepard E, American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Society of Critical Care Medicine Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Critical Care Medicine. 2007;35:605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies B, Connaughty S. Pediatric end-of-life care: Lessons learned from parents. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2002;32:5–6. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feudtner C, Kang TI, Hexem KR, Friedrichsdorf SJ, Osenga K, Siden H, Wolfe J. Pediatric palliative care patients: A prospective multi-center cohort study. Pediatrics. 2011;127:1094–1101. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field MJ, Behrman RE, editors. When children die: Improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine E, Reid MC, Shengelia R, Adelman RD. Directly observed patient–physician discussions in palliative and end-of-life care: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2010;13:595–603. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg IC. Social work perspectives on family communication and family conferences in palliative care. Progress in Palliative Care. 2010;18(4):213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg IC, Kawashima M, Asch SM. Communication with families facing life-threatening illness: A research-based model for family conferences. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2011;14:421–427. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier A, Frazier H, Warren NA. A discussion of family-centered care within the pediatric intensive care unit. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly. 2009;33:82–86. doi: 10.1097/CNQ.0b013e3181c8e015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friebert S. NHPCO facts and figures: Pediatric palliative and hospice care in America. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; Alexandria, VA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman DL, Hilden JN, Powaski K. Issues and challenges in palliative care for children with cancer. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2005;9:249–255. doi: 10.1007/s11916-005-0032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gries CJ, Engelberg RA, Kross EK, Zatzick D, Nielsen EL, Downey L, Curtis JR. Predictors of symptoms of post–traumatic stress and depression in family members after patient death in the intensive care unit. Chest. 2010;137:280–287. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RM, Valentine J, Haynes G, Geyer JR, Villareale N, McKinistry B, Churchill SS. The Seattle Pediatric Palliative Care Project: Effects on family satisfaction and health-related quality of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006;9:716–728. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, Kutsogiannis DJ, Peters S, O'Callaghan CJ. Decision-making in the ICU: Perspectives of the substitute decision-maker. Intensive Care Medicine. 2003;29:75–82. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1569-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds PS, Schum L, Baker JN, Wolfe J. Key factors affecting dying children and their families. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8(Suppl. 1):70–78. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooyman NR, Kramer BJ. Living through loss: Interventions across the life span. Columbia University Press; New York, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton N. Pediatric palliative care: The time has come. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:9–10. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BH. Family-centered care: Four decades of progress. Families, Systems, & Health. 2000;18:133–156. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BH, Eichner JM. Family-centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics. 2003;112:691–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, Parker-Raley J, Higgerson R, Christie LM, Legett S, Greathouse J. Finding the right words: The use of Allow Natural Death (AND) and DNR in pediatric palliative care. Journal for Healthcare Quality. 2008;30(5):55–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2008.tb01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, Sampson M, Greathouse J, Legett S, Higgerson RA, Christie L. Comfort and confidence levels of health care professionals providing pediatric palliative care in the intensive care unit. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life and Palliative Care. 2007;3:39–58. doi: 10.1300/J457v03n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ. Clinical ethics: A practical approach to ethical decisions in clinical medicine. 5th ed. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kreicbergs UC, Lannen P, Onelov E, Wolfe J. Parental grief after losing a child to cancer: Impact of professional and social support on long-term outcomes. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:3307–3312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannen PK, Wolfe J, Prigerson HG, Onelov E, Kreicbergs UC. Unresolved grief in a national sample of bereaved parents: Impaired mental and physical health 4 to 9 years later. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:5870–5876. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, Azoulay E. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356:469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack JW, Hilden JM, Watterson J, Moore C, Turner B, Grier HE, Wolfe J. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:9155–9161. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLachlan M. Culture and health. 2nd ed. Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Kung HC, Mathews TJ, Hovert DL, Strobino DM, Guyer B, Sutton SR. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2006. Pediatrics. 2008;121:788–801. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, Shannon SE, Rubenfeld GD, Curtis JR. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the ICU: Increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Critical Care Medicine. 2004;32:1484–1488. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000127262.16690.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meert K, Briller SH, Thurston C, Schim SM. Exploring parents’ environmental needs at the time of a child's death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2008;9:623–628. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31818d30d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meert KL, Donaldson AE, Newth CJ, Harrison R, Berger J, Zimmerman J, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network Complicated grief and associated risk factors among parents following a child's death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164:1045–1051. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meert KL, Thurston CS, Thomas R. Parental coping and bereavement outcome after the death of a child in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2001;2:324–328. doi: 10.1097/00130478-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier DE, Beresford L. Social workers advocate for a seat at palliative care table. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2008;11:10–14. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk BM, Feinstein N, Fairbanks E. Two decades of evidence to support implementation of the COPE program as standard practice with parents of young unexpectedly hospitalized/critically ill children and premature infants. Pediatric Nursing. 2006;32:475–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer EC, Burns JP, Griffith JL, Truog RD. Parental perspectives on end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine. 2002;30:226–231. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer EC, Ritholz MD, Burns JP, Truog RD. Improving the quality of end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: Parents’ priorities and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2006;117:649–657. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Children's Hospitals and Related Institutions 2009 Retrieved from http://www.childrenshospitals.net. [PubMed]

- Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, Lemaire F, Hubert P, Canoui P, French FAMIREA Group Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: Ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Critical Care Medicine. 2001;29:1893–1897. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rait D, Lederberg M. The family of the cancer patient. In: Holland JC, Rowland JH, editors. Handbook of psychooncology: Psychological care of the patient with cancer. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1989. pp. 555–601. [Google Scholar]

- Raymer M, Reese D. The history of social work in hospice. In: Berzoff J, Silverman P, editors. Living with dying: A handbook for end-of-life practitioners. Columbia University Press; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 150–160. [Google Scholar]

- Sahler OJ. The child and death. Pediatric Review. 2000;21:350–353. doi: 10.1542/pir.21-10-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands R, Manning JC, Vyas H, Rashid A. Characteristics of deaths in paediatric intensive care: A 10-year study. Nursing in Critical Care. 2009;14:235–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2009.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD, Dugan DO, Blustein J, Cranford R, Young EW. Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:1166–1172. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selph RB, Shiang J, Engelberg R, Curtis JR, White DB. Empathy and life support decisions in intensive care units. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:1311–1317. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0643-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shudy M, de Almeida ML, Ly S, Landon C, Groft S, Jenkins TL, Nicholson CE. Impact of pediatric critical illness and injury on families: A systematic literature review. Pediatrics. 2006;118(Suppl. 3):S203–S218. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0951B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AB, Hefley GC, Anand KJ. Parent bed spaces in the PICU: Effect on parental stress. Pediatric Nursing. 2007;33:215–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton RD, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Goss CH, Curtis JR. Clinician statements and family satisfaction with family conferences in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine. 2006;34:1679–1685. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000218409.58256.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studdert DM, Mello MM, Burns JP, Puopolo AA, Galper BZ, Truog RD, Brennan TA. Conflict in the care of patients with prolonged stay in the ICU: Types, sources, and predictors. Intensive Care Medicine. 2003;29:1489–1497. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey VA, Welch LC, Wetle T, Shield R, Mor V. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truog RD, Meyer EC, Burns JP. Toward interventions to improve end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine. 2006;34(Suppl. 11):S373–S379. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237043.70264.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulsky JA. Interventions to enhance communication among patients, providers, and families. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8(Suppl. 1):S95–S102. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman DE, Quill TE, Arnold RM. The family meeting: End-of-life goal setting and future planning. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2010a;13:462–463. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.9846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman DE, Quill TE, Arnold RM. Helping surrogates make decisions. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2010b;13:461–462. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.9847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West HF, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Curtis JR. Expressions of nonabandonment during the intensive care unit family conference. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8:797–807. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DB, Malvar G, Karr J, Lo B, Curtis JR. Expanding the paradigm of the physician's role in surrogate decision making: An empirically derived framework. Critical Care Medicine. 2010;38:743–750. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c58842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Palliative care. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/en.