Abstract

We previously demonstrated that 11,12 and 14,15-epoxeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) produce cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury in dogs and rats. Several signaling mechanisms have been implicated in the cardioprotective actions of the EETs; however, their mechanisms remain largely elusive. Since nitric oxide (NO) plays a significant role in cardioprotection and EETs have been demonstrated to induce NO production in various tissues, we hypothesized that NO is involved in mediating the EET actions in cardioprotection. To test this hypothesis, we used an in vivo rat model of infarction in which intact rat hearts were subjected to 30-min occlusion of the left coronary artery and 2-hr reperfusion. 11,12-EET or 14,15-EET (2.5 mg/kg) administered 10 min prior to the occlusion reduced infarct size, expressed as a percentage of the AAR (IS/AAR), from 63.9±0.8% (control) to 45.3±1.2% and 45.5±1.7%, respectively. A nonselective nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor, L-NAME (1.0 mg/kg) or a selective endothelial NOS inhibitor, L-NIO (0.30 mg/kg) alone did not affect IS/AAR but they completely abolished the cardioprotective effects of the EETs. On the other hand, a selective neuronal NOS inhibitor, nNOS I (0.03 mg/kg) and a selective inducible NOS inhibitor, 1400W (0.10 mg/kg) did not affect IS/AAR or block the cardioprotective effects of the EETs. Administration of 11,12-EET (2.5 mg/kg) to the rats also transiently increased the plasma NO concentration. 14,15-EET (10 μM) induced the phosphorylation of eNOS (Ser1177) as well as a transient increase of NO production in rat cardiomyoblast cell line (H9c2 cells). When 11,12-EET or 14,15-EET were administered at 5 min prior to reperfusion, infarct size was also reduced to 42.8±2.2% and 42.6±1.9%, respectively. Interestingly, L-NAME (1.0 mg/kg) and a mitochondrial KATP channel blocker, 5-HD (10 mg/kg) did not abolish while a sarcolemmal KATP channel blocker, HMR 1098 (6.0 mg/kg) and a mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) opener, atractyloside (5.0 mg/kg) completely abolished the cardioprotection produced by the EETs. 14,15-EET (1.5 mg/kg) with an inhibitor of MPTP opening, cyclosporin A (CsA, 1.0 mg/kg) produced a greater reduction of infarct size than their individual administration. Conversely, an EET antagonist 14,15-epoxyeicosa-5(Z)-enoic acid (14,15-EEZE, 2.5 mg/kg) completely abolished the cardioprotective effects of CsA, suggesting a role of MPTP in mediating the EET actions. Taken together, these results suggest that the cardioprotective effects of the EETs in an acute ischemia-reperfusion model are mediated by distinct mediators depending on the time of EET administration. The cardioprotective effects of EETs administered prior to ischemia were regulated by the activation of eNOS and increased NO production, while sarc KATP channels and MPTP were involved in the beneficial effects of the EETs when administered just prior to reperfusion.

Introduction

Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) are the cytochrome P450 (CYP) monooxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid that have been demonstrated to reduce infarct size of intact dog, rat and mouse hearts subjected to regional ischemia and reperfusion [1–5]. Despite strong evidence for the cardioprotective effects of EETs, the mechanisms by which EETs protect the myocardium from injury are still unclear. It has been suggested that EETs bind to specific membrane receptors including a putative EET receptor [6, 7] that has not been identified at the molecular level. Several studies suggested that EETs may be acting as agonists or antagonists on several G protein-coupled receptors such as the thromboxane receptor (TP) [8, 9] and the E-prostanoid receptor (EP2) [10] as well as the nuclear peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARs) [11–14], resulting in the activation of a number of signal transduction pathways. Interestingly, the activation of PPARα with WY 14643 in rats [15] or the activation of PPARγ with rosiglitazone in mice [16] induces nitric oxide (NO) production to protect against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Overall cardioprotective effects of EETs have been shown to be mediated by the activation of the sarcolemmal (sarc) and mitochondrial (mito) ATP-sensitive potassium channel (KATP channel), the calcium–activated potassium channel, the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), the extracellular regulated kinase (ERK1/2) pathway, and via increases of oxygen-derived free radicals [1, 3, 4, 17–19] which may act at the myocardial mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) to prevent or enhance its opening [17, 20].

NO is an important signaling molecule that has been demonstrated to reduce myocardial injury in a number of ischemia/reperfusion models. For example, brief periods of NO breathing reduced myocardial injury from ischemia/reperfusion in mice and pigs [21–23]. Oral feeding of rats with several NO donors/precursors for 5 days protected against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury [24]. Administration of an endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) enhancer, AVE 9488, which upregulates eNOS expression and increases NO production, protected the myocardium from ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice [25]. The cardioprotective effects of tetramethylpyrazine in rats have been attributed to its ability to increase the phosphorylation of eNOS and subsequent NO production through the PI3/Akt pathway [26]. NO was also found to exert cardioprotective effects in ischemia/reperfusion, at least in part, by activation of ERK1/2 [27]. Since EETs have an ability to activate eNOS and increase NO release [28–30], we determined whether the cardioprotective effects of the EETs in rat hearts are mediated by the activation of specific NOS isoform(s) and NO release.

Post-ischemic reflow is recognized as a major determinant of reperfusion-induced injury and it has been long-known to have potential for additional injury to the myocardium [31–33]. An early part of reperfusion induces a burst of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and calcium overload and triggers an opening of a nonspecific pore in the inner mitochondrial membrane, called the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) [34–36]. A prolonged opening of the MPTP leads to mitochondrial swelling, uncoupling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, ATP depletion, and eventually results in cell death (necrosis and apoptosis) [36–38]. Thus, MPTP has been extensively investigated as an important mediator for myocardial reperfusion injury [39, 40]. In this study, we determined whether EETs are pharmacological targets in protecting the myocardium from reperfusion injury and mechanisms involved including determining whether the cardioprotective effects of the EETs are mediated by MPTP.

Materials and Methods

All experiments conducted in this study were in accordance with the Position of the American Heart Association on Research and Animal Use adopted by the American Heart Association and the guidelines of the Biomedical Resource Center of the Medical College of Wisconsin. The Medical College of Wisconsin is accredited by the American Association of Laboratory Animal Care (AALAC).

Materials

11,12- and 14,15-Epxoyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) and an EET antagonist [41], 14,15-epoxyeicosa-5(Z)-enoic acid (14,15-EEZE) were synthesized in the laboratory of Dr. J.R. Falck. A nonselective NOS inhibitor (nitro-L-arginine methyl ester, L-NAME), a selective eNOS inhibitor (N5-(1-iminoethyl)-L-ornithine, L-NIO), a selective iNOS inhibitor (N-[[3-(aminomethyl) methyl)phenyl]methyl]-ethanimdamide dihydrochloride, 1400W), a mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel inhibitor (5-hydroxydecanoate, 5-HD), and a mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) blocker (cyclosporin A, CsA) were obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). A selective nNOS inhibitor ((4S)-N-(4-amino-5[aminoethyl]aminopentyl)-N′-nitroguanidine, nNOS I) and a mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) opener (atractyloside dipotassium salt, ATR) were obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). A sarcolemmal KATP channel inhibitor (1-{[5-[2-(5-chloro-o-anisamido)ethyl]-2-methoxyphenyl]sulfonyl}-3-methylthiourea, sodium salt, HMR 1098) was obtained from Aventis (Frankfurt, Germany). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against p-eNOS (Ser1177) and total-eNOS, ECL Western blotting detection kit, and BCA protein assay kit were obtained from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL). Goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP secondary antibody and 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorescein (DAF-FM) were obtained from Invitrogen (Camarillo, CA). Mini-Protean gels were obtained from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). H9c2 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Nitrate/Nitrite Fluorometric Assay Kit was obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). 11,12-EET, 14,15-EET, 14,15-EEZE, and CsA were dissolved in a vehicle composed of 95% ethanol, polyethylene glycol 200 and 1 N sodium hydroxide (5:5:1). All stocks of drugs were prepared in water except for 1400W (was which dissolved in 95% ethanol and subsequently diluted in water). All drugs were made up fresh daily.

Intact rat preparation protocol

The surgical procedure for the intact rat preparation has been previously described in detail [1]. Briefly, male Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 250–300 g were fasted overnight and anesthetized with Inactin (Sigma, 100 mg/kg, ip) and ventilated with room air supplemented with 100% oxygen. Body temperature was maintained at 37 ± 1 °C with a heating pad. Arterial blood pH, pCO2, and pO2 were monitored at selected intervals by an AVL automatic blood gas system and maintained within normal physiological limits (pH 7.35 to 7.45, pCO2 30 to 40 mmHg, and pO2 85 to 120 mmHg) by adjusting the respiration rate and oxygen flow or by intravenous administration of 1.5% sodium bicarbonate if necessary. Hemodynamics and heart rate were monitored throughout the experiment. A cannula was placed into the jugular vein and carotid artery to administer drugs and measure peripheral hemodynamics, respectively.

Experimental treatment protocol

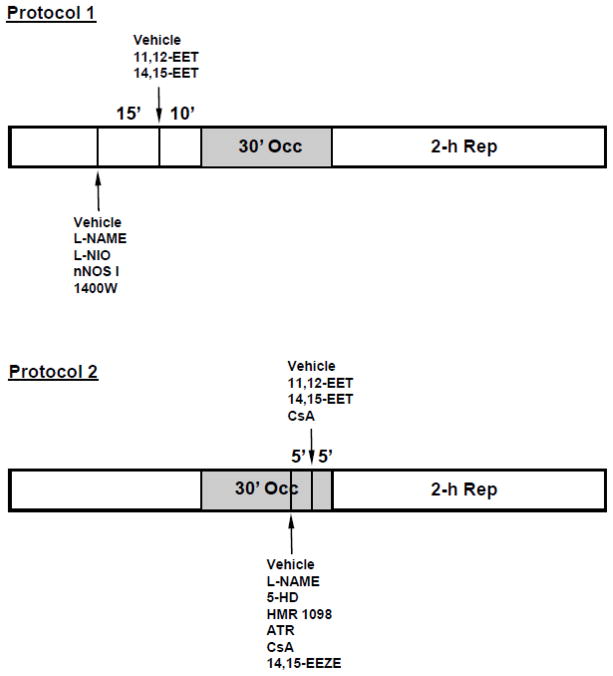

Rats were sequentially assigned to 34 groups for the different treatments. Typically, 6–10 rats were included in each group of experiments. At 10 min before the 30-min coronary occlusion period, 11,12-EET (2.5 mg/kg) or 14,15-EET (2.5 mg/kg) was administered by intravenous injection for 1–2 min (Fig. 1, Protocol 1). The 2.5 mg/kg dose was chosen based on preliminary dose-response experiments with 11,12- and 14,15-EET in the range of 1.0 to 5.0 mg/kg. The results indicated that doses above 2.5 mg/kg did not further reduce IS/AAR. For the NOS inhibitor studies, either a nonselective NOS inhibitor, L-NAME (1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg), a selective eNOS inhibitor, L-NIO (0.30 mg/kg), a selective nNOS inhibitor, nNOS I (0.03 mg/kg), or a selective iNOS inhibitor, 1400W (0.03, 0.10, and 0.30 mg/kg) were administered 15 min prior to EET administration.

Figure 1.

Protocols used to study the epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (EET)-induced cardioprotection in rat hearts. In these protocols, 11,12- or 14,15-EET was given alone intravenously 10 min prior to a 30-min occlusion and 2-h reperfusion (Protocol 1) or 5 min prior to reperfusion (Protocol 2). In protocol 1, nitric oxide synthase inhibitors were given intravenously 15 min prior to EET administration. In protocol 2, pharmacological agents were given intravenously 5 min prior to EET administration.

In series of experiments designed to investigate the cardioprotective effects of EETs against reperfusion injury (Fig. 1, Protocol 2) and their cellular mechanism(s), 11,12-EET or 14,15-EET (2.5 mg/kg) was administered at 5 min prior to reperfusion. L-NAME (1.0 mg/kg), 5-HD (10 mg/kg), HMR 1098 (6.0 mg/kg), or ATR (5.0 mg/kg) were administered 10 min prior to reperfusion (5 min prior to EET administration). In another group of experiments to investigate the synergistic effects of EETs and CsA on cardioprotection, CsA at a less than optimal dose (1.0 mg/kg) and 14,15-EET at a less than optimal dose (1.5 mg/kg) were administered alone or in combination just prior to reperfusion. An EET antagonist, 14,15-EEZE (2.5 mg/kg) was also administered to block the MPTP-mediated cardioprotective effects of CsA. In all groups, hemodynamic measurements and blood gas analyses were performed at baseline, at 15 min into the 30-min occlusion period and at the end of 2 h of reperfusion.

Infarct size determination

Infarct size was determined as previously described [1]. Briefly, at the end of the 2-h reperfusion period, the LAD was reoccluded. To determine the anatomic area-at-risk (AAR) and the nonischemic area, 1 mL of Patent blue dye was injected into the jugular vein and the heart was arrested by an iv injection of potassium chloride. The heart was then immediately removed and the left ventricle (LV) was dissected and sliced into serial transverse sections 1–2 mm in width. The nonstained ischemic area and the blue-stained normal area were separated and incubated with 1% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, Sigma) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 at 37 °C for 15 min. After incubation overnight in 10% formaldehyde, the non-infarcted and infarcted tissues within the AAR were separated and determined gravimetrically under a dissecting microscope. Infarct size was expressed as a percentage of the AAR.

Determination of NO concentrations in rat plasma

11,12-EET (2.5 mg/kg) was administered by intravenous injection into rats and blood was withdrawn from the femoral artery at various times as previously described [42]. The blood (about 100 μL) was aspirated over a few seconds into a chilled sample tube containing heparin (1000 U/mL), mixed thoroughly and placed in an ice bucket. The samples were centrifuged at 3000xg at 0°C for 20 min to separate plasma. Plasma was removed and transferred to a tube, purged with nitrogen gas, capped and stored at −80°C for analysis. Plasma NO (total nitrate and nitrite) was analyzed by using a Nitrate/Nitrite Fluorometric Assay Kit. Each rat plasma sample was divided into 4 replicates for NO determination. A total of 3 rats were used. The NO concentrations were normalized to the plasma volume.

Cell culture

Rat cardiomyoblast cell line (H9c2 cells) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin according to ATCC guidelines. Cells were grown in an incubator at 37° C and 5% CO2. Cells were used up to10 passages.

Western blot analysis of p-eNOS (Ser1177) in H9c2 cells

H9c2 cells at about 75% confluency were treated with 14,15-EET (10 μM) at 37 °C at various times. Then, cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors. The protein concentrations were determined by using a BCA protein assay kit. The samples were electrophoretically separated on Mini-Protean gels and detected for phosphorylated eNOS (p-eNOS Ser1177) using specific primary antibody and secondary antibody. Subsequently, the membranes were reprobed for total eNOS (t-eNOS) and used for normalization of the p-eNOS (Ser1177) band intensities.

Determination of NO concentrations in H9c2 cells

NO production was detected by immunocytochemistry in H9c2 cells and NO concentrations (total nitrate and nitrite) were determined in H9c2 cell lysates. First, H9c2 cells were cultured in 35-mm dishes to about 70% confluency and incubated with 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein (DAF-FM, 10 μM) at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, the media was removed and cells were washed three times with Hank’s buffered salt solution (HBSS) to remove free DAF-FM. Cells were treated with 14,15-EET (10 μM) at 37 °C. The fluorescent images of control cells and 14,15-EET treated-cells were captured with a Photometrics Sensys CCD camera and processed with Photometric Image ProPlus software. An increase of fluorescent intensity of cell images suggests an increase of NO production in these cells. Second, H9c2 cells were treated with 14,15-EET (10 μM) at 37 °C at various times. Cells were lysed and the samples were centrifuged at 100,000xg to remove particulates and membrane proteins. Then, the samples were analyzed for NO (nitrate and nitrite) concentrations by using Nitrate/Nitrite Fluorometric Assay Kits. Each sample was divided into four replicates for NO determination and four sets of samples were analyzed. The NO concentrations were normalized to the protein content.

Statistical analysis

All values were expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6–10/group). Differences between groups in hemodynamics were compared by using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Tukey’s post hoc test. Differences between groups in IS/AAR were compared by a one-way ANOVA. Differences between groups were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Results

Hemodynamics in the in vivo studies

There were no differences in baseline hemodynamics and no changes in heart rate or mean arterial pressure in any of the groups as compared to their corresponding control points in time (Tables 1&2). These results suggest that any changes observed in IS/AAR were unlikely to be the result of differences in peripheral hemodynamics between groups.

Table 1.

Hemodynamic Values (Heart Rate and AAR/LV)

| Heart Rate (beats/min) | AAR/LV | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Protocol | Con | 15-min Occ | 2-h Rep | (%) |

| Control (Pre) | 372 ± 7 | 382 ± 6 | 362 ± 5 | 40.8 ± 1.0 |

| 11,12-EET (Pre) | 367 ± 17 | 363 ± 9 | 370 ± 2 | 41.9 ± 4.3 |

| 14,15-EET (Pre) | 394 ± 10 | 410 ± 12 | 392 ± 7 | 45.0 ± 0.5 |

| L-NAME (Pre) | 372 ± 8 | 375 ± 8 | 375 ± 12 | 43.3 ± 1.1 |

| L-NAME + 11,12-EET (Pre) | 403 ± 18 | 377 ± 15 | 413 ± 28 | 41.0 ± 2.6 |

| L-NAME + 14,15-EET (Pre) | 365 ± 9 | 356 ± 8 | 354 ± 7 | 39.7 ± 1.6 |

| L-NIO (Pre) | 370 ± 6 | 390 ± 8 | 366 ± 11 | 37.4 ± 1.7 |

| L-NIO + 11,12-EET (Pre) | 383 ± 7 | 372 ± 7 | 367 ± 8 | 36.7 ± 3.3 |

| L-NIO + 14,15-EET (Pre) | 374 ± 7 | 378 ± 7 | 364 ± 3 | 40.8 ± 1.4 |

| nNOS I (Pre) | 394 ± 6 | 397 ± 9 | 378 ± 5 | 38.7 ± 1.2 |

| nNOS I + 11,12-EET (Pre) | 370 ± 10 | 380 ± 12 | 350 ± 15 | 44.1 ± 1.5 |

| nNOS I + 14,15-EET (Pre) | 395 ± 8 | 400 ± 9 | 372 ± 10 | 43.2 ± 2.6 |

| 1400W (Pre) | 392 ± 6 | 402 ± 7 | 386 ± 6 | 40.2 ± 3.7 |

| 1400W + 11,12-EET (Pre) | 390 ± 12 | 377 ± 12 | 380 ± 31 | 43.4 ± 2.7 |

| 1400W + 14,15-EET (Pre) | 373 ± 5 | 388 ± 7 | 370 ± 4 | 45.2 ± 4.2 |

| Control (Rep) | 390 ± 10 | 392 ± 15 | 379 ± 10 | 41.6 ± 4.1 |

| 11,12-EET (Rep) | 360 ± 10 | 362 ± 12 | 338 ± 7 | 45.1 ± 2.2 |

| 14,15-EET (Rep) | 368 ± 7 | 372 ± 8 | 343 ± 6 | 40.5 ± 3.0 |

| L-NAME (Rep) | 375 ± 5 | 380 ± 10 | 330 ± 10 | 36.8 ± 4.8 |

| L-NAME + 14,15-EET (Rep) | 382 ± 8 | 382 ± 9 | 362 ± 4 | 39.4 ± 1.6 |

| 5-HD (Rep) | 368 ± 9 | 373 ± 8 | 335 ± 10 | 36.3 ± 1.8 |

| 5-HD + 11,12-EET (Rep) | 387 ± 12 | 388 ± 13 | 350 ± 9 | 43.5 ± 2.0 |

| 5-HD + 14,15-EET (Rep) | 360 ± 11 | 360 ± 11 | 330 ± 7 | 45.3 ± 1.2 |

| HMR-1098 (Rep) | 357 ± 10 | 370 ± 9 | 337 ± 10 | 39.4 ± 2.0 |

| HMR + 11,12-EET (Rep) | 374 ± 8 | 374 ± 13 | 346 ± 6 | 36.3 ± 3.0 |

| HMR + 14,15-EET (Rep) | 370 ± 6 | 374 ± 7 | 348 ± 7 | 40.9 ± 1.2 |

| Atractyloside (ATR, Rep) | 400 ± 12 | 412 ± 9 | 393 ± 9 | 41.6 ± 2.6 |

| ATR + 11,12-EET (Rep) | 388 ± 8 | 394 ± 7 | 364 ± 10 | 35.1 ± 1.5 |

| ATR + 14,15-EET (Rep) | 377 ± 7 | 392 ± 7 | 373 ± 8 | 37.1 ± 2.7 |

| 14,15-EET (Low dose, Rep) | 392 ± 8 | 387 ± 7 | 373 ± 6 | 43.0 ± 2.1 |

| CsA (Low dose, Rep) | 392 ± 6 | 389 ± 10 | 363 ± 7 | 45.9 ± 3.2 |

| CsA + 14,15-EET (Rep) | 388 ± 6 | 400 ± 4 | 378 ± 9 | 37.1 ± 2.1 |

| 14,15-EEZE (Rep) | 408 ± 8 | 407 ± 7 | 382 ± 9 | 39.9 ± 1.4 |

| CsA + 14,15-EEZE (Rep) | 376 ± 14 | 376 ± 9 | 368 ± 8 | 40.4 ± 1.7 |

All values are the mean ± SEM (N = 6–10 rats).

Abbreviations: AAR = Area-at-risk; Con = Control; LV = Left Ventricle; Occ = Occlusion; Pre = Prior to occlusion; Rep = Reperfusion or prior to reperfusion.

Table 2.

Hemodynamic Values (Blood Pressure, mmHg)

| SBP | DBP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Protocol | Con | 15-min Occ | 2-h Rep | Con | 15-min Occ | 2-h Rep |

| Control (Pre) | 154 ± 4 | 135 ± 3 | 111 ± 2 | 123 ± 3 | 112 ± 3 | 80 ± 3 |

| 11,12-EET (Pre) | 137 ± 8 | 102 ± 9 | 112 ± 13 | 109 ± 10 | 87 ± 4 | 81 ± 15 |

| 14,15-EET (Pre) | 162 ± 4 | 139 ± 9 | 119 ± 7 | 131 ± 4 | 120 ± 6 | 84 ± 6 |

| L-NAME (Pre) | 145 ± 4 | 125 ± 6 | 104 ± 4 | 113 ± 4 | 108 ± 6 | 79 ± 4 |

| L-NAME + 11,12-EET (Pre) | 130 ± 14 | 119 ± 16 | 113 ± 12 | 103 ± 16 | 102 ± 7 | 87 ± 15 |

| L-NAME + 14,15-EET (Pre) | 148 ± 3 | 117 ± 7 | 112 ± 5 | 114 ± 4 | 97 ± 7 | 84 ± 5 |

| L-NIO (Pre) | 165 ± 6 | 145 ± 5 | 121 ± 7 | 131 ± 6 | 121 ± 5 | 87 ± 5 |

| L-NIO + 11,12-EET (Pre) | 144 ± 3 | 114 ± 7 | 111 ± 6 | 114 ± 2 | 92 ± 6 | 79 ± 5 |

| L-NIO + 14,15-EET (Pre) | 155 ± 6 | 129 ± 7 | 110 ± 3 | 120 ± 6 | 103 ± 7 | 74 ± 3 |

| nNOS I (Pre) | 154 ± 7 | 125 ± 6 | 115 ± 5 | 123 ± 6 | 102 ± 6 | 84 ± 4 |

| nNOS I + 11,12-EET (Pre) | 127 ± 2 | 109 ± 9 | 98 ± 7 | 98 ± 4 | 88 ± 8 | 68 ± 9 |

| nNOS I + 14,15-EET (Pre) | 152 ± 6 | 128 ± 5 | 115 ± 3 | 121 ± 5 | 104 ± 5 | 84 ± 2 |

| 1400W (Pre) | 173 ± 8 | 137 ± 7 | 111 ± 5 | 134 ± 4 | 117 ± 7 | 83 ± 5 |

| 1400W + 11,12-EET (Pre) | 150 ± 1 | 117 ± 15 | 105 ± 8 | 117 ± 1 | 92 ± 14 | 72 ± 5 |

| 1400W + 14,15-EET (Pre) | 157 ± 10 | 117 ± 7 | 106 ± 8 | 118 ± 8 | 95 ± 7 | 74 ± 8 |

| Control (Rep) | 151 ± 8 | 110 ± 6 | 109 ± 6 | 117 ± 5 | 96 ± 1 | 71 ± 4 |

| 11,12-EET (Rep) | 152 ± 4 | 127 ± 5 | 102 ± 5 | 123 ± 4 | 107 ± 6 | 72 ± 7 |

| 14,15-EET (Rep) | 148 ± 3 | 132 ± 8 | 105 ± 5 | 119 ± 3 | 109 ± 7 | 73 ± 6 |

| L-NAME (Rep) | 147 ± 10 | 131 ± 3 | 120 ± 5 | 119 ± 1 | 93 ± 14 | 92 ± 4 |

| L-NAME + 14,15-EET (Rep) | 152 ± 8 | 126 ± 7 | 112 ± 6 | 120 ± 7 | 104 ± 7 | 85 ± 5 |

| 5-HD (Rep) | 137 ± 7 | 115 ± 10 | 98 ± 8 | 108 ± 8 | 96 ± 10 | 70 ± 8 |

| 5-HD + 11,12-EET (Rep) | 146 ± 3 | 135 ± 4 | 109 ± 5 | 120 ± 2 | 104 ± 7 | 73 ± 5 |

| 5-HD + 14,15-EET (Rep) | 139 ± 3 | 118 ± 7 | 109 ± 4 | 108 ± 3 | 95 ± 6 | 78 ± 6 |

| HMR-1098 (Rep) | 146 ± 6 | 125 ± 7 | 105 ± 6 | 114 ± 5 | 103 ± 7 | 78 ± 7 |

| HMR + 11,12-EET (Rep) | 143 ± 8 | 131 ± 4 | 101 ± 6 | 113 ± 9 | 100 ± 8 | 64 ± 6 |

| HMR + 14,15-EET (Rep) | 139 ± 5 | 123 ± 3 | 106 ± 6 | 108 ± 6 | 99 ± 4 | 80 ± 5 |

| Atractyloside (ATR, Rep) | 148 ± 5 | 129 ± 4 | 109 ± 5 | 118 ± 5 | 104 ± 3 | 72 ± 7 |

| ATR + 11,12-EET (Rep) | 153 ± 5 | 121 ± 6 | 112 ± 4 | 119 ± 5 | 96 ± 9 | 75 ± 5 |

| ATR + 14,15-EET (Rep) | 145 ± 6 | 118 ± 7 | 108 ± 7 | 113 ± 5 | 96 ± 7 | 74 ± 7 |

| 14,15-EET (Low dose, Rep) | 148 ± 4 | 116 ± 6 | 106 ± 4 | 118 ± 4 | 96 ± 6 | 74 ± 4 |

| CsA (Low dose, Rep) | 143 ± 6 | 110 ± 5 | 105 ± 4 | 113 ± 5 | 87 ± 6 | 74 ± 7 |

| CsA + 14,15-EET (Rep) | 136 ± 3 | 118 ± 4 | 111 ± 3 | 109 ± 3 | 96 ± 4 | 79 ± 4 |

| 14,15-EEZE (Rep) | 146 ± 4 | 120 ± 4 | 111 ± 3 | 118 ± 3 | 98 ± 4 | 76 ± 2 |

| CsA + 14,15-EEZE (Rep) | 135 ± 6 | 114 ± 6 | 110 ± 4 | 102 ± 7 | 87 ± 7 | 77 ± 5 |

All values are the mean ± SEM (N = 6–10 rats).

Abbreviations: Con = Control; DBP = Diastolic Blood Pressure; Occ = Occlusion; Pre = Prior to occlusion; Rep = Reperfusion or prior to reperfusion; SBP = Systolic Blood Pressure.

Effects of EETs on infarct size

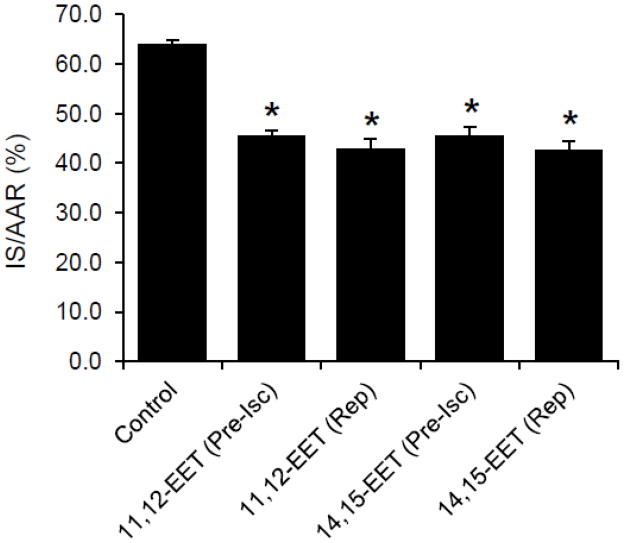

There were no statistical differences in left ventricular weight, area at risk, or area at risk as a percentage of left ventricular weight (AAR/LV) between groups (Table 1). However, both 11,12- and 14,15-EET, administered 10 min prior to ischemia, produced a similar decrease in infarct size when expressed as a percent of the area at risk (IS/AAR) (Figure 2). Interestingly, a decrease in IS/AAR produced by 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET administered at 5 min prior to reperfusion was similar to the decrease in IS/AAR when the EETs were administered 10 min prior to ischemia.

Figure 2.

Effects of EETs on infarct size in intact rat hearts. Both 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET administered 10 min prior to ischemia or 5 min prior to reperfusion significantly reduced infract size. All values are the mean ± SEM (n = 6–9/group). * P < 0.01 vs Control group.

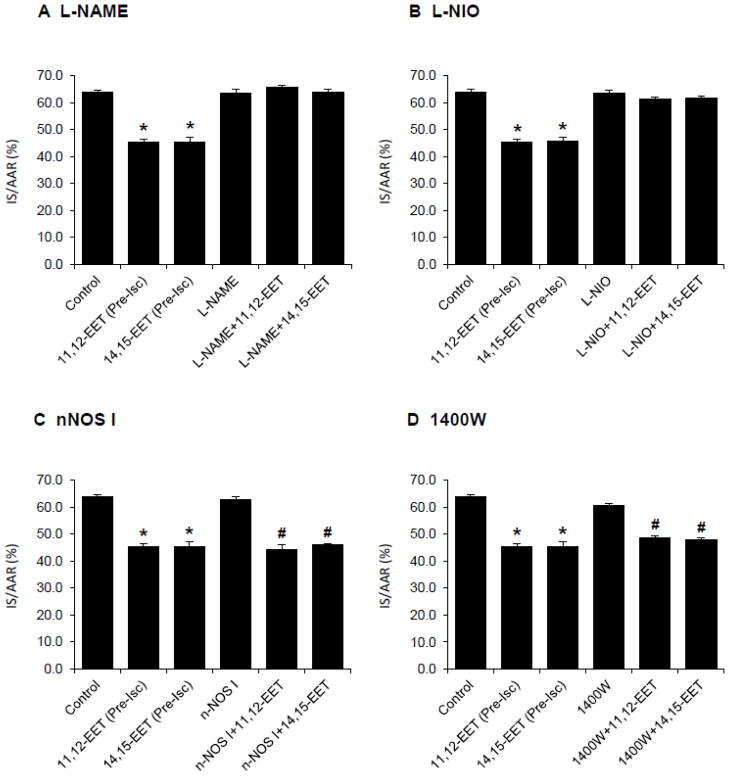

Effects of NOS inhibitors on infarct size

To test the hypothesis that the cardioprotective effects of EETs are mediated by NOS and NO, NOS inhibitors were administered intravenously to rats 15 min prior to EET administration. A nonselective NOS inhibitor, L-NAME (1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg) and a selective eNOS inhibitor, L-NIO (0.30 mg/kg) did not alter IS/AAR when they were administered alone. However, both L-NAME and L-NIO completely abolished the cardioprotection produced by both 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET (Fig. 3A&B). On the other hand, a selective nNOS inhibitor, nNOS I and a selective iNOS inhibitor, 1400W did not alter infarct size when they were administered alone or in combination with the EETs (Fig. 3C&D).

Figure 3.

Effects of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitors on the EET-induced cardioprotection in intact rat hearts. NOS inhibitors were administered 15 min prior to the 11,12-EET or 14,15-EET administration. (A) L-NAME, a nonselective NOS inhibitor was administered at 1.0 mg/kg. (B) L-NIO, a selective eNOS inhibitor was administered at 0.30 mg/kg. (C) nNOS I, a selective nNOS inhibitor was administered at 0.03 mg/kg. (D) 1400W, a selective iNOS inhibitor was administered at 0.10 mg/kg. All NOS inhibitors did not affect the infarct size when administered alone; however, only L-NAME and L-NIO completely abolished the cardioprotective effects of 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET. All values are the mean ± SEM (n = 6/group). * P < 0.01 vs Control group. # P < 0.01 vs nNOS I and 1400W groups.

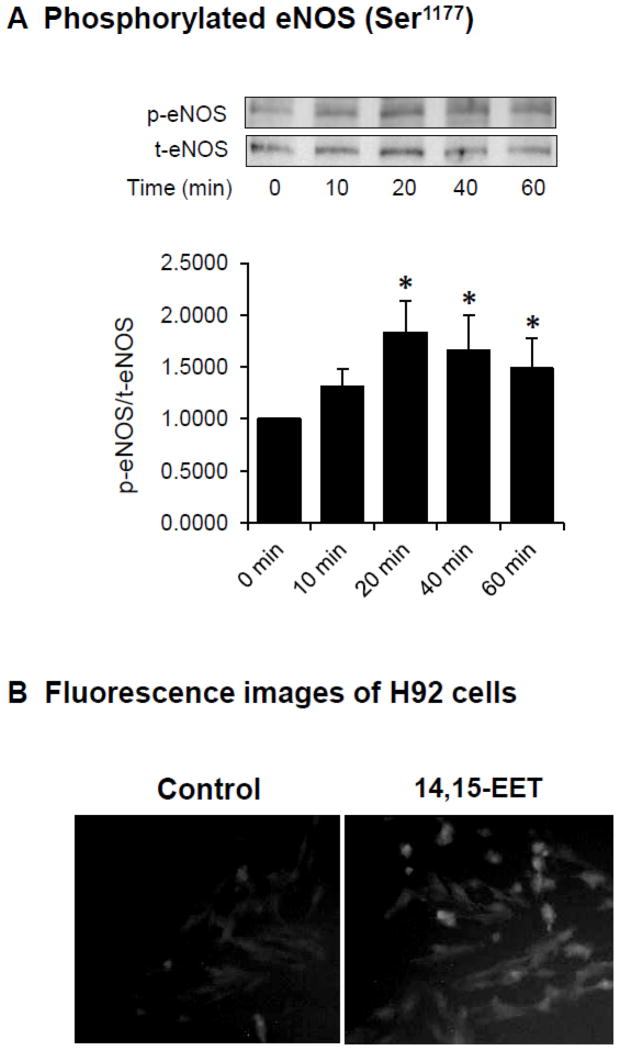

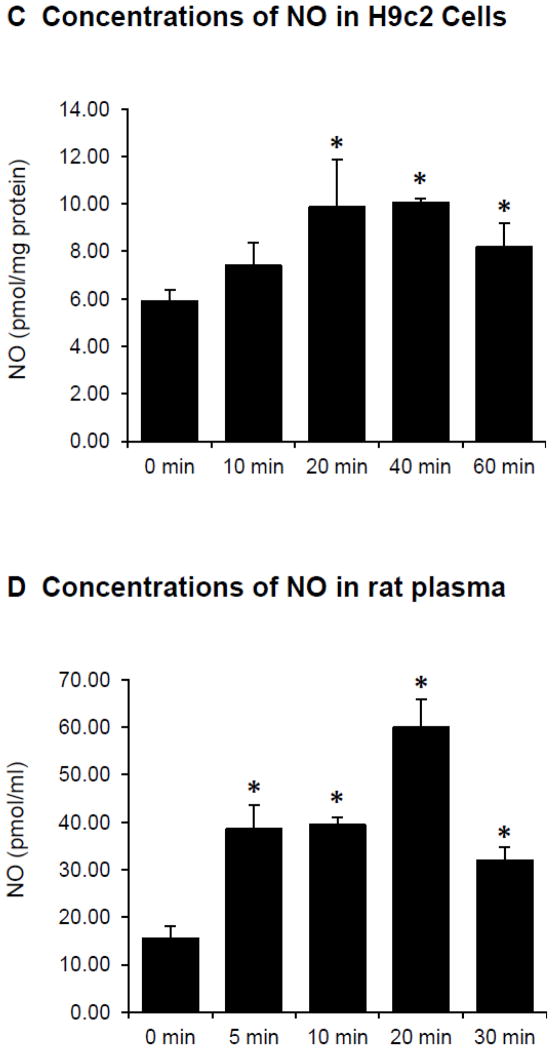

EETs activate eNOS and NO production in H9c2 cells

H9c2 cells were treated with 14,15-EET (10 μM) at various times and the phosphorylation of eNOS (Ser1177) was determined by Western blot analysis. The immunoreactive band intensity of p-eNOS (Ser1177) normalized to the total eNOS band intensity increased as a function of time to the maximum at about 20 min of treatment (Fig. 4A). These results suggest that the activity of eNOS was most likely induced by 14,15-EET.

Figure 4.

Effects of EETs on the phosphorylation of eNOS (Ser1177) and NO production in cardiac myocytes and rat plasma. (A) Example of immunoreactive bands for phosphorylated eNOS (p-eNOS, Ser1177) and total eNOS (t-eNOS) in H9c2 cells treated with 14,15-EET (10 μM) at 37 °C for different times (above panel) and the average of p-eNOS/t-eNOS (n = 4, bottom panel). * P < 0.05 vs Control group. (B) Fluorescence images depicting NO in H9c2 cells treated with PBS buffer vehicle (left) or 14,15-EET (10 μM) (right) at 37 °C for 15 min. (C) NO concentrations (total nitrate and nitrite) in H9c2 cells treated with 14,15-EET (10 μM) at 37 °C for different times. The NO concentrations were normalized to the protein content. Values are the mean ± SEM (n = 4). * P < 0.05 vs Control group. (D) Plasma NO concentrations (total nitrate and nitrite) at different times in rats after intravenous administration with 11,12-EET (2.5 mg/kg). The NO concentrations were presented as pmol of NO per plasma volume (ml). Values are the mean ± SEM (n = 3). * P < 0.05 vs Control group.

Treatment of H9c2 cells with 14,15-EET (10 μM) for 20 min and the produced NO was detected in the cells using DAF-FM to form a complex with NO. The fluorescent image signal of H9c2 cells treated with 14,15-EET was markedly higher than the fluorescence signal of the control cells (Fig. 4B), which suggested that 14,15-EET induced a production of NO in H9c2 cells.

Treatment of H9c2 cells with 14,15-EET (10 μM) increased NO concentrations (determined as nitrate and nitrite) as a function of time with the maximal concentration occurring at about 20 min at 37 °C (Fig. 4C). The increase of NO concentrations in H9c2 cells by 14,15-EET occurred at a similar time to the increase of eNOS activity (p-eNOS, Ser1177). A similar increase of NO concentrations was observed in H9c2 cells treated with 11,12-EET (data not shown).

EETs increase NO concentrations in rat plasma

Rats were administered with 11,12-EET (2.5 mg/kg) intravenously and arterial blood was collected and plasma NO concentrations were determined (as nitrate and nitrite) at various times after EET injection. The plasma NO concentrations rapidly increased as a function of time and reached the maximal concentration at 20 min after EET injection (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that EETs induced a release of NO in arterial blood and may represent a mechanistic pathway for cardioprotection by the EETs.

Effects of a NOS inhibitor administered prior to reperfusion on infarct size

To test whether the cardioprotective effects of EETs administered just prior to reperfusion are mediated by NOS and NO, a non-selective NOS inhibitor, L-NAME (1.0 mg/kg) was administered intravenously to rats 5 min prior to EET administration. L-NAME did not alter IS/AAR when it was administered alone as compared with the control (63.8±1.3% vs 63.9±0.8%). L-NAME also did not block the cardioprotective effects of EETs when it was administered in combination with 14,15-EET as compared with 14,15-EET alone (43.2±2.0% vs 42.6±1.9%). These results suggest that NOS and NO did not have a role in cardioprotection produced by the EETs from reperfusion-induced injury.

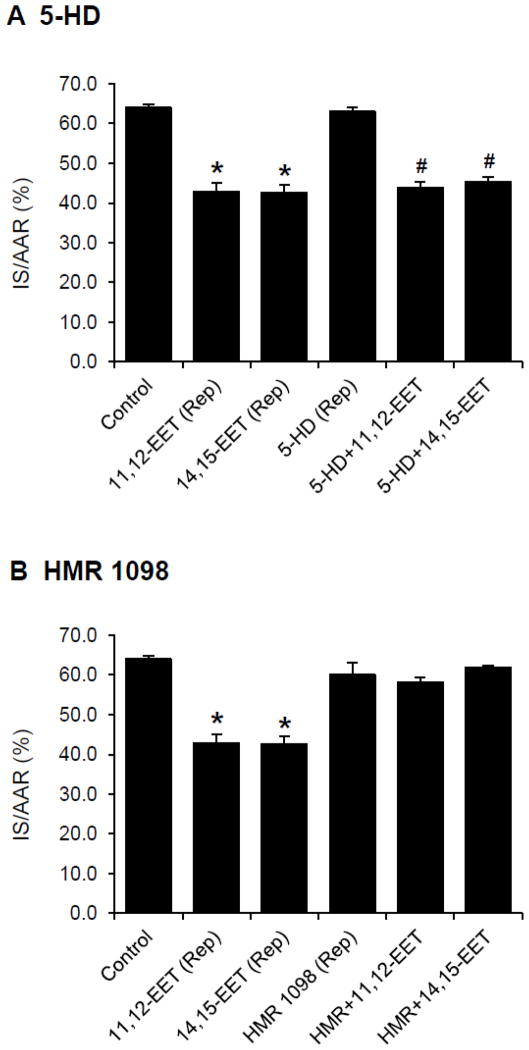

Role of KATP channels in EET-mediated reperfusion injury

To test whether the cardioprotective effects of EETs administered just prior to reperfusion are mediated by KATP channels, a mitochondrial KATP channel blocker, 5-HD (10 mg/kg) or a sarcolemmal KATP channel blocker, HMR 1098 (6.0 mg/kg) was administered at 5 min prior to EET administration. 5-HD did not alter infarct size when administered alone and it did not block the cardioprotective effects of the EETs (Fig. 5A). On the other hand, HMR 1098 did not alter infarct size when administered alone but it blocked the cardioprotective effects of the EETs (Fig. 5 B).

Figure 5.

Effects of KATP channel inhibitors on the EET-induced cardioprotection in intact rat hearts. KATP channel inhibitors were administered 10 min prior to reperfusion (5 min prior to the 11,12-EET or 14,15-EET administration). (A) 5-HD, a mitochondrial KATP channel blocker was administered at 10 mg/kg. (B) HMR 1098, a sarcolemmal KATP channel blocker was administered at 6.0 mg/kg. All values are the mean ± SEM (n = 6/group). * P < 0.01 vs Control group. # P < 0.01 vs 5-HD group.

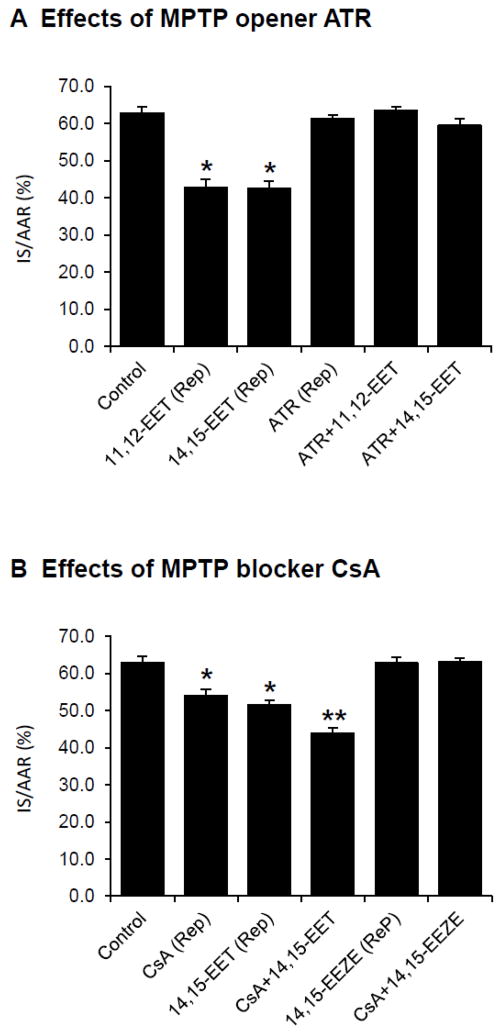

Role of MPTP in EET-mediated reperfusion injury

Since MPTP opening has been recognized as a major determinant in reperfusion injury, we determined whether the cardioprotective effects of EETs are mediated by MPTP. An MPTP opener, ATR (5.0 mg/kg) was administered at 5 min prior to EET administration. ATR did not significantly alter IS/AAR when administered alone but it completely abolished the cardioprotective effects of both 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Effects of MPTP opening on EET-induced cardioprotection against reperfusion injury in intact rat hearts. (A) Effects of an MPTP opener Atractyloside (ATR) on EET-induced cardioprotection. ATR (5.0 mg/kg) was administered 10 min prior to reperfusion (5 min prior to the 11,12-EET or 14,15-EET administration). All values are the mean ± SEM (n = 6/group). * P < 0.01 vs Control group. (B) Effects of an MPTP blocker cyclosporine A (CsA) and an EET antagonist 14,15-EEZE on EET-induced cardioprotection. CsA at low dose (1.0 mg/kg) or 14,15-EEZE (2.5 mg/kg) was administered 10 min prior to reperfusion. Then, 14,15-EET at low dose (1.5 mg/kg) or CsA (1.0 mg/kg) was administered 5 min prior to reperfusion, respectively. All values are the mean ± SEM (n = 6/group). * P < 0.05 vs Control group and ** P < 0.01 vs Control group.

14,15-EET at low dose (1.5 mg/kg) administered at 5 min prior to reperfusion reduced IS/AAR from 62.8±1.7% (control) to 51.5±1.2%. Similarly, CsA at low dose (1.0 mg/kg) administered prior to reperfusion reduced IS/AAR to 54.0±1.6% (Fig. 6B). A combination of 14,15-EET and CsA at low doses further reduced IS/AAR to 45.8±1.6%. Furthermore, an EET antagonist, 14,15-EEZE (2.5 mg/kg) completely abolished the cardioprotection of CsA _(Fig. 6B). These results suggest the EET-inhibited MPTP opening as a mechanism responsible in the reperfusion-induced injury.

Discussion

The present results strongly suggest that the cardioprotective effects of 11,12- and 14,15-EET administered prior to ischemia in intact rat hearts involve the activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and NO production. An intravenous injection of 11,12-EET induced an increase of NO concentrations in arterial plasma of the rats and it reached the maximal concentration in about 20 min. In rat cardiomyoblast cell line (H9c2 cells), 14,15-EET induced a phosphorylation of eNOS (Ser1177), indicating an increase of eNOS activity. 14,15-EET also induced an increase in NO concentrations in H9c2 cells with the maximal concentration observed at 20 min after 14,15-EET treatment. Importantly, a nonselective NOS inhibitor (L-NAME) and a selective eNOS inhibitor (L-NIO) completely abolished EET-induced cardioprotection, indicating that the actions of the EETs are mediated, at least in part, by the eNOS/NO signaling pathway.

The notion that EETs activate eNOS and increase NO production is supported by previous studies in a number of biological systems. For example, in bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs), either overexpression of cytochrome P450 epoxygenases (to increase production of EETs) or treatment of cells with exogenous EETs increased the activity of eNOS and NO production [28–30]. The increase of phosphorylated eNOS by EETs was mediated by MAPK, PI3K/Akt and PKC signaling pathways [28–30]. Intriguingly, some of these studies also reported that the expression of the constitutive eNOS increases when the cells were treated with EETs for longer than 2 h. On the other hand, some studies demonstrated that NOS/NO is not involved in the antiapoptotic effects of overexpression of CYP epoxygenases (to increase endogenous EETs) in tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)-induced apoptosis in BAECs [43]. An increase in eNOS activity and NO production by EETs is similar to the downstream effects of ligustrazine, a bioactive component contained in Chuanxiong (Chinese herb) which increases the phosphorylation of eNOS (Ser1177) and NO production, resulting in cardioprotection in rat hearts [26].

NO derived from eNOS has been demonstrated to posses cardioprotective effects not only against acute ischemia/reperfusion [25, 26, 44, 45] but also are involved in early ischemic preconditioning [45] as well as a late phase of ischemic preconditioning [46]. At present, it is not known whether EET-induced cardioprotection in early and late ischemic preconditioning [47] is mediated by eNOS/NO signaling, and this aspect of NO signaling deserves further studies.

Interestingly, nNOS has been shown to contribute to cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury [48] by increasing oxidative/nitrative stress, but it contributes to ischemic preconditioning-induced cardioprotection [48, 49]. In a late phase preconditioning (at 72 h) model in rabbits, nNOS expression as well as myocardial nitrate/nitrite increased. This increase in nNOS-derived NO was required to drive COX-2 activity and resulted in cardioprotection [50]. In the present study of acute ischemia-reperfusion, nNOS did not contribute to the actions of EETs in cardioprotection of rat hearts. However, whether nNOS has any role in the cardioprotective actions of the EETs in the late phase of preconditioning is not known.

Since iNOS is an inducible enzyme, it is not likely that iNOS will play a role in mediating acute ischemia/reperfusion injury of intact rat hearts in this study. iNOS has been long known to be cardioprotective in the late phase of ischemic preconditioning [51]. Expression and activity of iNOS and NO release were increased in the late phase of preconditioning and postconditioning [52, 53] and in isoflurane induced-second window of preconditioning in rat hearts [54]. The role of iNOS in cardioprotection in the late phase of ischemic preconditioning has been attributed to a decrease in reperfusion-induced oxygen free radicals and inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition pores [55]. Although EETs have been shown to be involved in cardioprotection in ischemic preconditioning and post-conditioning [47], it is not known whether iNOS mediates the actions of EETs in these models.

It has become clear from accumulating evidence that enhancing the endogenous concentration of EETs by numerous approaches including sEH inhibitors, overexpression of CYPs producing EETs in transgenic animals or by exogenous administration of novel EET analogues may be a new therapeutic target for reducing ischemia/reperfusion injury. EETs likely turn on a number of cellular signaling pathways including the activation of eNOS and NO release that lead to cardioprotective effects. It is currently known that the cardiac mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channel (mitoKATP) is cardioprotective in ischemia-reperfusion and the opening of the mitoKATP channel is activated by NO [56–58], particularly in the case of ischemic preconditioning. We previously showed that EETs elicit cardioprotection in an acute ischemia-reperfusion model of rat hearts and dog hearts via opening of sarcolemmal KATP channels and mitoKATP channels [1, 2]. Collectively, administering EETs during a brief period (10 min) prior to ischemia are cardioprotective primarily via a major pathway which includes activation of eNOS and subsequent NO release and opening of KATP channels. The eNOS-mediated release of NO is beneficial in acute protection of the myocardium.

Results from this study also suggest that the cardioprotective effects of EETs against reperfusion injury are mediated by different mechanisms than those activated by pre-ischemic administration. The cardioprotection produced by EETs against reperfusion-induced injury was not mediated by NOS/NO and mitoKATP channels but involved the sarcKATP channel. These results are similar to our previous observation which demonstrated that inhibition of CYP hydroxylase to block the production of the arachidonic acid metabolite, 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (the metabolite that exhibits opposing pharmacological effects from the EETs) that led to the reduction of infarct size during reperfusion in rat hearts [59].

The cardioprotective effects of EETs during reperfusion was completely abolished by the MPTP opener ATR, suggesting that EETs inhibit the opening of MPTP, the process that has been demonstrated as an important target for preventing reperfusion-induced injury [40]. The ability of EETs to block the opening of MPTP is supported by a study in rat cardiac cells [20]. The cardioprotective effects of EETs against reperfusion-induced injury by inhibiting MPTP opening was similar to results obtained with morphine in isolated rat hearts [60]. The further reduction of infarct size by administration of CsA and 14,15-EET from individual drug administration as well as the ability of an EET antagonist 14,15-EEZE to completely abolish cardioprotection by CsA strongly suggest that the inhibition of MPTP opening plays a major role in EET-induced cardioprotection against reperfusion-induced injury. These results suggest that EET mimetics may lead to an important novel treatment of patients with ischemic heart disease. In particular, the benefits of EETs administered prior to reperfusion may be a more practical target for clinical treatment of ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Highlights.

EETs administered at ischemia or reperfusion reduce infarct size similarly.

eNOS/NO signaling pathway mediates the cardioprotection of EETs at ischemia.

At reperfusion, MPTP is an important mediator of the EET cardioprotective actions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alan T. Tang for his technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants HL-74314 and HL111392 (GJG).

Footnotes

Disclosures: None declared

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gross GJ, Hsu A, Falck JR, Nithipatikom K. Mechanisms by which epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) elicit cardioprotection in rat hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007 Mar;42(3):687–91. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nithipatikom K, Moore JM, Isbell MA, Falck JR, Gross GJ. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in cardioprotection: ischemic versus reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006 Aug;291(2):H537–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00071.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seubert JM, Sinal CJ, Graves J, DeGraff LM, Bradbury JA, Lee CR, et al. Role of soluble epoxide hydrolase in postischemic recovery of heart contractile function. Circ Res. 2006 Aug 18;99(4):442–50. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237390.92932.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seubert J, Yang B, Bradbury JA, Graves J, Degraff LM, Gabel S, et al. Enhanced postischemic functional recovery in CYP2J2 transgenic hearts involves mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channels and p42/p44 MAPK pathway. Circ Res. 2004 Sep 3;95(5):506–14. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000139436.89654.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motoki A, Merkel MJ, Packwood WH, Cao Z, Liu L, Iliff J, et al. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition and gene deletion are protective against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008 Nov;295(5):H2128–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00428.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gross GJ, Gauthier KM, Moore J, Falck JR, Hammock BD, Campbell WB, et al. Effects of the selective EET antagonist, 14,15-EEZE, on cardioprotection produced by exogenous or endogenous EETs in the canine heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008 Jun;294(6):H2838–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00186.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang W, Tuniki VR, Anjaiah S, Falck JR, Hillard CJ, Campbell WB. Characterization of epoxyeicosatrienoic acid binding site in U937 membranes using a novel radiolabeled agonist, 20-125i-14,15-epoxyeicosa-8(Z)-enoic acid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008 Mar;324(3):1019–27. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.129577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behm DJ, Ogbonna A, Wu C, Burns-Kurtis CL, Douglas SA. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids function as selective, endogenous antagonists of native thromboxane receptors: identification of a novel mechanism of vasodilation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009 Jan;328(1):231–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.145102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senouvo FY, Tabet Y, Morin C, Albadine R, Sirois C, Rousseau E. Improved bioavailability of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids reduces TP-receptor agonist-induced tension in human bronchi. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011 Nov;301(5):L675–82. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00427.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang C, Kwan YW, Au AL, Poon CC, Zhang Q, Chan SW, et al. 14,15-Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid induces vasorelaxation through the prostaglandin EP(2) receptors in rat mesenteric artery. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2010 Jun 30; doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pozzi A, Ibanez MR, Gatica AE, Yang S, Wei S, Mei S, et al. Peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-alpha-dependent inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem. 2007 Jun 15;282(24):17685–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng VY, Huang Y, Reddy LM, Falck JR, Lin ET, Kroetz DL. Cytochrome P450 eicosanoids are activators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007 Jul;35(7):1126–34. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.013839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang D, Hirase T, Nitto T, Soma M, Node K. Eicosapentaenoic acid increases cytochrome P-450 2J2 gene expression and epoxyeicosatrienoic acid production via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in endothelial cells. J Cardiol. 2009 Dec;54(3):368–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu DY, Davis BB, Wang ZH, Zhao SP, Wasti B, Liu ZL, et al. A potent soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor, t-AUCB, acts through PPARgamma to modulate the function of endothelial progenitor cells from patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2012 Apr 21; doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.03.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bulhak AA, Sjoquist PO, Xu CB, Edvinsson L, Pernow J. Protection against myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury by PPAR-alpha activation is related to production of nitric oxide and endothelin-1. Basic Res Cardiol. 2006 May;101(3):244–52. doi: 10.1007/s00395-005-0580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonon AT, Bulhak A, Labruto F, Sjoquist PO, Pernow J. Cardioprotection mediated by rosiglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligand, in relation to nitric oxide. Basic Res Cardiol. 2007 Jan;102(1):80–9. doi: 10.1007/s00395-006-0613-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seubert JM, Zeldin DC, Nithipatikom K, Gross GJ. Role of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in protecting the myocardium following ischemia/reperfusion injury. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007 Jan;82(1–4):50–9. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Batchu SN, Chaudhary KR, El-Sikhry H, Yang W, Light PE, Oudit GY, et al. Role of PI3Kalpha and sarcolemmal ATP-sensitive potassium channels in epoxyeicosatrienoic acid mediated cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012 Jul;53(1):43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato M, Yokoyama U, Fujita T, Okumura S, Ishikawa Y. The roles of cytochrome p450 in ischemic heart disease. Curr Drug Metab. 2011 Jul;12(6):526–32. doi: 10.2174/138920011795713715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katragadda D, Batchu SN, Cho WJ, Chaudhary KR, Falck JR, Seubert JM. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids limit damage to mitochondrial function following stress in cardiac cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009 Jun;46(6):867–75. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hataishi R, Rodrigues AC, Neilan TG, Morgan JG, Buys E, Shiva S, et al. Inhaled nitric oxide decreases infarction size and improves left ventricular function in a murine model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006 Jul;291(1):H379–84. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01172.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagasaka Y, Fernandez BO, Garcia-Saura MF, Petersen B, Ichinose F, Bloch KD, et al. Brief periods of nitric oxide inhalation protect against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Anesthesiology. 2008 Oct;109(4):675–82. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318186316e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X, Huang Y, Pokreisz P, Vermeersch P, Marsboom G, Swinnen M, et al. Nitric oxide inhalation improves microvascular flow and decreases infarction size after myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007 Aug 21;50(8):808–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossoni G, Manfredi B, De Gennaro Colonna V, Brini AT, Polvani G, Clement MG, et al. Nitric oxide and prostacyclin pathways: an integrated mechanism that limits myocardial infarction progression in anaesthetized rats. Pharmacol Res. 2006 Apr;53(4):359–66. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frantz S, Adamek A, Fraccarollo D, Tillmanns J, Widder JD, Dienesch C, et al. The eNOS enhancer AVE 9488: a novel cardioprotectant against ischemia reperfusion injury. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009 Nov;104(6):773–9. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lv L, Jiang SS, Xu J, Gong JB, Cheng Y. Protective effect of ligustrazine against myocardial ischaemia reperfusion in rats: the role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2012 Jan;39(1):20–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li DY, Tao L, Liu H, Christopher TA, Lopez BL, Ma XL. Role of ERK1/2 in the anti-apoptotic and cardioprotective effects of nitric oxide after myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Apoptosis. 2006 Jun;11(6):923–30. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-6305-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang JG, Chen RJ, Xiao B, Yang S, Wang JN, Wang Y, et al. Regulation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activity through phosphorylation in response to epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007 Jan;82(1–4):162–74. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang H, Lin L, Jiang J, Wang Y, Lu ZY, Bradbury JA, et al. Up-regulation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase by endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor involves mitogen-activated protein kinase and protein kinase C signaling pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003 Nov;307(2):753–64. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen R, Jiang J, Xiao X, Wang D. Effects of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on levels of eNOS phosphorylation and relevant signaling transduction pathways involved. Sci China C Life Sci. 2005 Oct;48(5):495–505. doi: 10.1360/062004-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braunwald E, Kloner RA. Myocardial reperfusion: a double-edged sword? J Clin Invest. 1985 Nov;76(5):1713–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI112160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buckberg GD. When is cardiac muscle damaged irreversibly? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1986 Sep;92(3 Pt 2):483–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vinten-Johansen J, Johnston WE, Mills SA, Faust KB, Geisinger KR, DeMasi RJ, et al. Reperfusion injury after temporary coronary occlusion. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1988 Jun;95(6):960–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss JN, Korge P, Honda HM, Ping P. Role of the mitochondrial permeability transition in myocardial disease. Circ Res. 2003 Aug 22;93(4):292–301. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000087542.26971.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halestrap AP, Clarke SJ, Javadov SA. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening during myocardial reperfusion--a target for cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res. 2004 Feb 15;61(3):372–85. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(03)00533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halestrap AP, Kerr PM, Javadov S, Woodfield KY. Elucidating the molecular mechanism of the permeability transition pore and its role in reperfusion injury of the heart. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998 Aug 10;1366(1–2):79–94. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore: its fundamental role in mediating cell death during ischaemia and reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003 Apr;35(4):339–41. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Lisa F, Canton M, Menabo R, Dodoni G, Bernardi P. Mitochondria and reperfusion injury. The role of permeability transition. Basic Res Cardiol. 2003 Jul;98(4):235–41. doi: 10.1007/s00395-003-0415-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hausenloy DJ, Duchen MR, Yellon DM. Inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening at reperfusion protects against ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2003 Dec 1;60(3):617–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davidson SM, Hausenloy D, Duchen MR, Yellon DM. Signalling via the reperfusion injury signalling kinase (RISK) pathway links closure of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore to cardioprotection. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006 Mar;38(3):414–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gauthier KM, Deeter C, Krishna UM, Reddy YK, Bondlela M, Falck JR, et al. 14,15-Epoxyeicosa-5(Z)-enoic acid: a selective epoxyeicosatrienoic acid antagonist that inhibits endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization and relaxation in coronary arteries. Circ Res. 2002 May 17;90(9):1028–36. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000018162.87285.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nithipatikom K, Gross ER, Endsley MP, Moore JM, Isbell MA, Falck JR, et al. Inhibition of cytochrome P450omega-hydroxylase: a novel endogenous cardioprotective pathway. Circ Res. 2004 Oct 15;95(8):e65–71. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146277.62128.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang S, Lin L, Chen JX, Lee CR, Seubert JM, Wang Y, et al. Cytochrome P-450 epoxygenases protect endothelial cells from apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha via MAPK and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007 Jul;293(1):H142–51. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00783.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones SP, Greer JJ, Kakkar AK, Ware PD, Turnage RH, Hicks M, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase overexpression attenuates myocardial reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004 Jan;286(1):H276–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00129.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Talukder MA, Yang F, Shimokawa H, Zweier JL. eNOS is required for acute in vivo ischemic preconditioning of the heart: effects of ischemic duration and sex. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010 Aug;299(2):H437–45. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00384.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xuan YT, Guo Y, Zhu Y, Wang OL, Rokosh G, Bolli R. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase plays an obligatory role in the late phase of ischemic preconditioning by activating the protein kinase C epsilon p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase pSer-signal transducers and activators of transcription1/3 pathway. Circulation. 2007 Jul 31;116(5):535–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.689471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gross GJ, Gauthier KM, Moore J, Campbell WB, Falck JR, Nithipatikom K. Evidence for role of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in mediating ischemic preconditioning and postconditioning in dog. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009 Jul;297(1):H47–52. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01084.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barua A, Standen NB, Galinanes M. Dual role of nNOS in ischemic injury and preconditioning. BMC Physiol. 2010;10:15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-10-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu XM, Zhang GX, Yu YQ, Kimura S, Nishiyama A, Matsuyoshi H, et al. The opposite roles of nNOS in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion-induced injury and in ischemia preconditioning-induced cardioprotection in mice. J Physiol Sci. 2009 Jul;59(4):253–62. doi: 10.1007/s12576-009-0030-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y, Kodani E, Wang J, Zhang SX, Takano H, Tang XL, et al. Cardioprotection during the final stage of the late phase of ischemic preconditioning is mediated by neuronal NO synthase in concert with cyclooxygenase-2. Circ Res. 2004 Jul 9;95(1):84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000133679.38825.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo Y, Jones WK, Xuan YT, Tang XL, Bao W, Wu WJ, et al. The late phase of ischemic preconditioning is abrogated by targeted disruption of the inducible NO synthase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 Sep 28;96(20):11507–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Y, Guo Y, Zhang SX, Wu WJ, Wang J, Bao W, et al. Ischemic preconditioning upregulates inducible nitric oxide synthase in cardiac myocyte. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002 Jan;34(1):5–15. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jones SP, Bolli R. The ubiquitous role of nitric oxide in cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006 Jan;40(1):16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wakeno-Takahashi M, Otani H, Nakao S, Imamura H, Shingu K. Isoflurane induces second window of preconditioning through upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase in rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005 Dec;289(6):H2585–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00400.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.West MB, Rokosh G, Obal D, Velayutham M, Xuan YT, Hill BG, et al. Cardiac myocyte-specific expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury by preventing mitochondrial permeability transition. Circulation. 2008 Nov 4;118(19):1970–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.791533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ljubkovic M, Shi Y, Cheng Q, Bosnjak Z, Jiang MT. Cardiac mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channel is activated by nitric oxide in vitro. FEBS Lett. 2007 Sep 4;581(22):4255–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harada N, Miura T, Dairaku Y, Kametani R, Shibuya M, Wang R, et al. NO donor-activated PKC-delta plays a pivotal role in ischemic myocardial protection through accelerated opening of mitochondrial K-ATP channels. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004 Jul;44(1):35–41. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200407000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu Z, Ji X, Boysen PG. Exogenous nitric oxide generates ROS and induces cardioprotection: involvement of PKG, mitochondrial KATP channels, and ERK. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004 Apr;286(4):H1433–40. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00882.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gross ER, Nithipatikom K, Hsu AK, Peart JN, Falck JR, Campbell WB, et al. Cytochrome P450 omega-hydroxylase inhibition reduces infarct size during reperfusion via the sarcolemmal KATP channel. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004 Dec;37(6):1245–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim JH, Chun KJ, Park YH, Kim J, Kim JS, Jang YH, et al. Morphine-induced postconditioning modulates mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening via delta-1 opioid receptors activation in isolated rat hearts. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2011 Jul;61(1):69–74. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2011.61.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]