Abstract

Background

Patient navigation (PN) programs are being widely implemented to reduce disparities in cancer care for racial/ethnic minorities and the poor. However, few systematic studies cogently describe the processes of PN.

Methods

We qualitatively analyzed 21 transcripts of semi-structured exit interviews with three navigators about their experiences with patients who completed a randomized trial of PN. We iteratively discussed codes/categories, reflective remarks, and ways to focus/organize data and developed rules for summarizing data. We followed a three-stage analysis model: reduction, display, and conclusion drawing/verification. We used ATLAS.ti_5.2 for text segmentation, coding, and retrieval.

Results

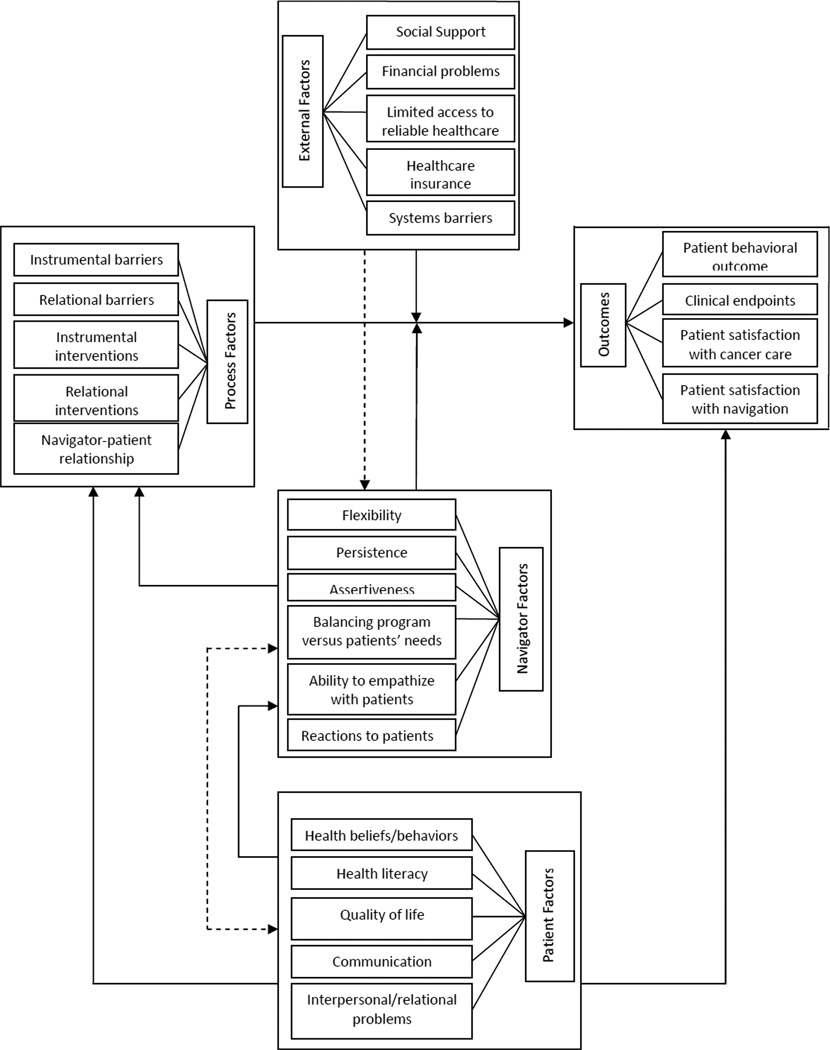

Four categories of factors affecting cancer care outcomes emerged: patients, navigators, navigation processes, and external factors. These categories formed a preliminary conceptual framework describing ways in which PN processes influenced outcomes. Relationships between processes and outcomes were influenced by patient, navigator, and external factors.

Conclusion

The process of PN has at its core relationship-building and instrumental assistance. An enhanced understanding of the process of PN derived from our analyses will facilitate improvement in navigators’ training and rational design of new PN programs to reduce disparities in cancer-related care.

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare disparities based on race, ethnicity and income remain a public health challenge in the United States.1–5 Despite significant advances in prevention, early detection and management of cancer, individuals from racial/ethnic minorities and lower socioeconomic groups continue to experience substantially higher cancer mortality rates than their Caucasian counterpatrs.6–8 Inequalities in cancer care in the United States are well documented and are associated with delays in follow-up for abnormal screening, uncoordinated care and mismanagement of cancer among racial/ethnic minorities and the poor.9–11

In recent years, patient navigation (PN) has emerged as a promising method to reduce disparities in cancer mortality rates for racial/ethnic minorities and the poor.12–15 PN involves providing support and guidance to an individual with abnormal cancer screening test results or with a diagnosis of cancer and helping this patient in accessing the healthcare system and overcoming barriers to obtaining optimal cancer care.16–18 PN programs are being widely implemented among underserved populations by the American Cancer Society (ACS), the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and at various cancer centers. Nevertheless, few studies systematically describe what aspects of PN are most critical and whether and how PN can alter clinical outcomes. The National Cancer Institute and ACS are addressing this paucity of evidence by supporting a collaborative research project called Patient Navigator Research Program (PNRP) to evaluate the effectiveness of PN across various underserved and poor populations in the US. One of the goals of the PNRP is to define the characteristics of an effective PN program. In order to achieve this goal, we need a clear conceptual framework of PN and an enhanced understanding of PN processes.

PN encompasses a wide range of instrumental and relational functions to assist patients as well as to help patients help themselves that navigators perform on behalf of patients. The primary purpose of this qualitative study was to describe key processes that navigators actually used drawing from the perspectives of trained navigators from the field. We also sought to describe factors that facilitate and impede PN and propose an initial taxonomy of PN interventions that both assist and empower patients. The findings will also enhance understanding of key aspects of PN and provide a framework for strategies that could help improve cancer clinical outcome.

METHODS

We qualitatively analyzed data from 21 interviews with three patient navigators. Each interview pertained to one patient randomized to the navigation arm of the PNRP study. We selected patients sequentially as they were completing their navigation intervention until we reached saturation in terms of the contents of narratives. Navigators notified the research group when they were about to complete navigation with a patient. An interview was then scheduled within a week or two of completion of navigation.

Inclusion Criteria

Patients in the PN clinical trial met the following criteria for inclusion: 1) age 18 years or over, 2) receiving care at a PN participating practice, 3) having a positive screening test or a diagnosis of breast or colorectal cancer, and 4) having no prior invasive cancer or history of lymphoma or leukemia (except non-melanoma skin cancer or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia). Patients were required not to be pregnant at the time of enrollment.

Ninety percent of the 21 patients were female (90%) and ranged in age from 29 to 83 years. Forty-eight percent were married, 19% were divorced, 14% were single, and 19% were widowed. The majority were Caucasians (67%), 19% were blacks, and 14% reported other races but did not provide an explication. The sample included patients with breast cancer (76%), colorectal cancer (19%), and abnormal screening for breast cancer (5%). Twenty-four percent of these patients had less than a high school education, 33% completed high school or had a General Equivalency Diploma, 24% had an associate degree or some college, 14% completed college, and 5% had a post graduate or professional degree.

Characteristics of Navigators

Our program recruited individuals from the community and trained them to work as navigators with cancer patients. Our navigators had at least a high school education, relevant knowledge of the community, and previous experience or training in case management and health care. Two of our navigators were proficient in both Spanish and English.

Navigators’ Training/Supervision

Navigators underwent a three-month intensive training that included an 80-hour Community Health Worker (CHW) curriculum developed through the Cornell Empowering Families Project. The CHW curriculum consisted of 10 modules: self-care for CHW, principles of empowerment, relationship and communication skills, cultural competencies training, working with low-literacy patients, needs assessment, accessing services, family conferences, and collaboration. Additional training components included adult learning principles, patient-physician communication, patient confidentiality, HIPAA, cancer health disparities, roles of navigators, and basics of breast and colorectal cancer. The training included opportunities for navigators to role-play interviewing and rehearse teaching/coaching skills. A licensed clinical social worker with experience in the supervision of paraprofessionals and case-management supervised the navigators.

Semi-Structured Interview Protocol (SSIP)/Administration

The SSIP was developed to capture the essence of PN from navigators’ perspectives and included questions about navigators’ overall experience working with patients, barriers that had to be overcome, and interpersonal and situational factors that influenced PN. Interviews lasted an average of 30 minutes. All interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim. Navigators were encouraged to use file notes, field notes and study data to assist their recall about each patient. We tried to create a trusting interview milieu to facilitate genuine discussion about PN; navigators were assured confidentiality and anonymity of their comments.

DATA ANALYSIS

We used a three-stage data analysis model: reduction, display, and conclusion drawing and verification.19 This approach resulted in a logical organization of data that facilitated effective manipulation, discussions, interpretation and verification. More than 174 pages of transcribed interviews were generated. Initial analysis by the Qualitative Data Analysis Team (QDAT) produced 506 codes and sub-codes, 61 memos, and 393 quotes. We used ATLAS.ti-5.2, a qualitative data analysis software package, for text segmentation, attaching codes to segments, combining codes, and for coding and retrieval strategies that facilitated examination of connections between codes and theory building.

Data Reduction

This stage included data collection, selection, and development of categories, which occurred between September 2006 and September 2008. The QDAT wrote summaries/memos, developed clusters of codes/sub-codes, and identified emerging themes. We discussed significance of concepts formed explanatory statements/themes. Themes relevant to our research questions were selected and discussed. Initially, we selected five transcribed audio-recorded interviews that we coded independently and then compared. We discussed themes, resolved coding discrepancies, and developed categories and definitions that encompassed related codes. Four categories emerged from our data analysis: Patient, Navigator, Navigation Process, and External Factors. Categories, codes/sub-codes were revised, new codes/sub-codes were generated, and problematic codes/subcodes were discarded based on QDAT consensus. The initial five and additional sixteen interviews were subsequently re-coded/coded using the revised and updated categories and codes/sub-codes list. Two members of our team served as primary coders for all the interviews. Other members of the team served as double coders. Primary and secondary coders reviewed codes and quotes from matching interviews. The QADT reviewed unresolved coding discrepancies between primary and secondary coders and made final coding decisions based on group consensus.

Data Display

We developed a data matrix that included categories and codes/sub-codes to organize and facilitate accurate data processing. We revised this matrix continuously as we progressed with our iterative analysis and understanding of the data.

Conclusion Drawing/Verification

We sought disconfirming data for our emerging hypothesis that patient, navigator and external factors affect the relationship between PN processes and outcomes.

RESULTS

The interviews provided compelling narratives about the experiences of patients and navigators with the cancer care system, the progression and dynamics of the relationships between patients and navigators, and how patients’ and navigators’ personal characteristics influenced navigation processes and outcomes. Four major categories influencing PN emerged from our qualitative analysis: Navigation Process Factors (NPF), Patient Factors, Navigator Factors, and External Factors (Tables 1–3). Navigators emphasized the importance of the navigator-patient relationship above and beyond instrumental supports provided to patients. Additionally, a small perspective difference was observed among the three navigators. One navigator demonstrated a more limited repertoire of descriptors about relationships with patients. This small difference, however, was not determined to contribute to important variances in interview contents among the three navigators. In addition, our goal in the present study was not to conduct a comparative analysis of navigators’ experiences. Our focus was to investigate preliminary factors not previously examined in the literature, which our navigators felt could significantly influence navigation processes and outcome.

Table 1.

Sample Quotes Illustrating Navigation Processes

| Providing Social Support | “Some patients they don’t need us to do everything for them, they just need us to listen to them cause to them that’s help enough…. it helps them think out, speak their thoughts, and actually decide "well I told somebody so now I guess I have to do something about it, now that I admitted it”. |

| “It would take them like thirty minutes… just to find a place where they could get to draw blood out. And so I would sit there and she would hold my hand. She would squeeze me because she would be poked here and poked there and in this way”. | |

| Encouraging | "Sometimes you have to fight against patients to get them to do things that are there’s good for them. And they don’t see it as good for them at the time, but afterwards, they realize “oh, thank you that you helped me. Even though when I wanted to give up, you still kept on encouraging me to do it”." |

| Communications | “She was getting ready to start her radiation. She wasn’t sure what kind of questions to ask her radiation oncologist, so that’s when we began. We talked about what kinds of questions she may want to ask. I gave her the questions and she actually asked them”. |

| “It made an impact on the oncologist that she was prepared to ask questions and uh, they actually wrote them down for her, her answers right on the sheet that she had”. | |

| “I always come up with some (questions) of my own during the appointment that I think she may want to know the answer to. When you have two people asking questions, you know, it prolongs the appointment a little bit more, and it gets more information”. | |

| “I wrote down all her questions and I mailed them to her. I said, when you go to your next appointment bring this sheet [paper] with you and ask these questions and you can write down the responses to them. She said the doctor told her “no, she [doctor] wasn’t going to answer that question now; that wasn’t important now”. | |

| Helping to Understand Medical Information | “I’m very surprised sometimes some of them don’t even know anything says they do have cancer. They don’t know what a stage is, they don’t know what a grade is, they don’t know (what a) medical oncologist is”. |

| “She had to take Tamoxifen…She wasn’t sure why she had to take it, so…we talked about that a little bit, then I went on the internet, printed out some sheets on Tamoxifen and what’s it for. And then she had the same concern with implants, she didn’t know what implant to pick …and I asked her did you… ask your doctor …she said, “Yeah, he told me that he really wants me to decide.” But how can she decide if she doesn’t know what’s the benefit, doesn’t know what’s better than the other one…So I sent her some information on that, and so that helped her too to make up her mind”. | |

| Coordinating Care | “We had to spend a lot of time making phone calls between different providers… between her insurance company to try to get them to get a referral sent …. So that took a lot of communication, a lot of phone calls back and forth with people and explaining the situation”. |

| “[We explain] who the doctor’s are that are involved in their care, and what each one of them does… one person for radiology, one person for … MRI, they see another person for chemo and another person for radiation and …[a] surgeon. I mean there’s just so many…plus their primary doctors. [We explain] what’s gonna happen”. | |

| Transportation | …we would have to set up the transportation for them because they didn’t speak English. … she would say “I don’t speak English”, which is really the only thing she could say in English, and they would hang up the phone on her. …No matter how many times I told them, that “they do not speak English. Don’t call their house" … they would [nevertheless] call them to tell them appointments. The patient’s wife would call me and tell me someone called me from the hospital …Then I would have to go and investigate to figure out who it was that called them”. |

| Supporting Patients’ Autonomy | “Well, I don’t want to be angry at her… And say you should be doing this or you should be doing this. Let her do what she wants to do. Just as long as she understands, ya know, what could happen and the surgeon and the nurses and everybody explains, ya know, just my job is to make sure that they know that she understands what the implications are of her decision to stop treatments and she did”. |

| Navigator-Patient Relationship | “Once she felt comfortable with me, she would call me and ask me to go with her to appointments, or call me for me to just listen to her. Yes, it [relationship] definitely changed over time”. |

| “Sometimes you have to prove yourself to some patients cause they’ve been burned by other people. They work with other people that promised some things and they never come through, and so there is like this hesitation on their part to totally trust you … You have to understand that’s how they are. Little by little, you know, I think you have a lot on your plate, let me help you with this little thing. And then once they see that you, you know, that’s OK with a little bit, then they let go with more. And just being patient with them. Seeing when the doors open a little bit so you can, you know, push it open a little bit more and get yourself more in there”. | |

| “She felt comfortable telling me things that maybe she didn’t feel like telling, she couldn’t tell anybody else cause she didn’t have anybody basically. So she saw me as somebody that she could trust and confide in… She didn’t have anybody to tell. She was a widow. Her son is incarcerated and her daughter has drug problems. Her … brothers and sisters, they’re all passed”. | |

| “So and even at the end when she didn’t want to do anything else, and she’s like, “No, I have stage 4 disease I don’t care, I don’t wanna do anything.” And the doctor told her … “You know we really care about you. I’m doing this out of caring for you, and [the navigator’s] doing it…I know you’re tired of us bugging you, but we care about you that’s why we’re doing it.” And she said, “…I know that you guys care about me, and I like that you guys care about me, but I don’t want to do it”. | |

| Unable to “Connect” | “So I would just call her periodically and check and see how she was doing so it wasn’t like my usual typical patients that I feel like I’m more closer to them, I know more about them and they know me. This patient was distant”. |

Table 3.

Sample Quotes Illustrating Navigator and External Factors

| Navigator Factors | |

| Empathy | “I think just trying to pretend like I was the patient. Like OK, I’m blind …[are] there stairs? Is the door wide enough for me to get in? …So, I had to think like if I was him, like if I was the patient, what would I do, what would I need?”. |

| Persistence | “When you think that there is a chance that the patient may not be able to get the proper treatment or their insurance may not cover a certain doctor there is always a way around that, there is always a chance that a patient even that doesn’t have the proper insurance that they would, there is always a chance for them to be able to see a specialized doctor that maybe won’t accept that type of insurance normally. You can always at least try it and then see what happens and if it doesn’t work try something else. First, be persistent and ask people questions and look into everything. Be assertive with these types of things because she may not have ended up getting that care that she got”. |

| Navigator’s reactions to patients | “I’ll always remember her and I think she will always remember me. I really didn’t realize how helpful I was to her until one day she told [me] that I was like her right arm, that she felt lost if she didn’t have me to help her”. |

| External Factors | |

| Positive Social Support | “Well, her husband was a major support for her. … I guess she didn’t need navigation, because she had him. … He’d bring her to all her appointments … He had a list of questions that he had for her. The doctor to ask. … And, so any choice, any decision that she made, she always would you know, talk to him about it first before she did anything”. |

| “She did have a friend who would bring her from where she lives over to all her appointments and who helped her when she had to come home after her surgery, who helped to take care of her when she was at home. She actually stayed at the friend’s house”. | |

| “She, she liked to, you know at her age she really, you know was able to talk about her faith, and her church, and they actually were a support system for her. Because I did mention, you know she needed some ah, you know support group or anything like that, but she never she had her church”. | |

| Lack of Social Support | “…her being alone and not having anybody…She didn’t have anybody to tell. She was a widow. Her son is incarcerated and her daughter has drug problems”. |

| Negative Social Influences | “For example, “He would say things that wouldn’t make her want to go to the doctors. They wanted her to have a colonoscopy, so I went to her house, and tried to convince her that she should really do this, and so I tried to get her husband involved and I said, “I’m here to convince Mrs. X that she should get a colonoscopy” and he goes “well, every time you go to the hospital they always find something else wrong with you”. |

| Navigator Provides Social Support | “Well, sometimes we think we are just going to their appointments and to them that’s the whole world because they have nobody that cares about them. It’s like we’re not their family but somehow we are because when they have a problem they call us. Sometimes they don’t even call their own husband. We know stuff the husbands’ don’t even know in some cases”. |

| Other External factors | “And at first she didn’t have a phone and then later on she didn’t have insurance either and something I worked out where we were able to help her to get insurance, the other navigator was able to help her get insurance and a phone so she was able to have a phone”. |

| “So, the problem was she didn’t have the right insurance. She had Medicaid HMO and they would not cover her visit”. | |

| “And she confessed to me that she felt that they didn’t like her because she was very assertive and she felt like they disliked her. She says well she (doctor) told me to be quiet for once and listen”. |

Navigation Process Factors

Navigators’ discussions of the PN process focused on three broad themes: 1) identification of instrumental and relational barriers (e.g., transportation, healthcare insurance, fear, and mistrust), 2) instrumental and relational interventions (e.g., arranging transportation, accompanying patients to visits) and 3) the navigator-patient relationship. While most instrumental barriers were readily characterized, those pertaining to personal characteristics and problematic interpersonal/relational styles of patients required that the navigators spend time getting to know the patient and build a trusting relationship. For instance, one fearful patient’s “non-compliance” was only understood when the navigator discovered, through perseverance, that the patient was worried about side effects because of a prior negative experience with her arthritis medications.

To facilitate healthcare, our navigators intervened with patients, their families, medical staff, healthcare insurance companies, community agencies, and various other healthcare resources. Other activities such as appointment tracking and coordinating patients’ care, albeit essential and constituting a major aspect of PN, often happened behind the scene. Our data showed that the intensity and complexity of PN varied among patients and depended on personal attributes and characteristics of patients.

Other key navigator interventions involved assisting patients with healthcare communication, which took several forms: coaching patients to formulate and ask questions, occasionally asking questions on patients’ behalf, gathering health information, or helping patients and their families understand medical information (Table 1). Sometimes navigators had to explain medical information in lay terms to facilitate comprehension, especially for patients with low health literacy. Navigators encouraged patients, especially those who demonstrated hesitation or shyness, to communicate with their doctors and other healthcare providers. Coaching facilitated assertiveness and more interactive patient-healthcare provider communication in the clinical encounter.

Navigators described their relationships with patients as either business-like (focusing on the instrumental aspects of cancer care), professional (the relationship revolved only around cancer issues and avoided personal issues), and/or friendly (relationships where navigator learned things about the patient outside of his/her cancer care including family problems). Friendly relationships were characterized by greater emotional connectedness, often facilitated by shared ancestry, cultural backgrounds, and religious beliefs. Nonetheless, although there were a few patients with whom the navigators could not connect, they reported that their efforts to work with every patient and develop trusting relationships generally helped patients to disclose important health related and personal information and to participate more actively in their care.

Prior studies about the dynamics and importance of the navigator-patient relationship are lacking. In this study, we found that patient-navigator relationships were very important and varied among patients, requiring substantial flexibility on the part of the navigators. On many occasions, the navigators reported complex relationships with patients. Navigators went to great length to describe how they built trust and rapport in difficult situations. Some patients seemed to invite navigators to help them make important decisions regarding their healthcare. Navigators also encountered patients who did not fully understand the gravity of their cancer diagnosis. Some of the most complex and difficult patient-navigator encounters involved patients who chose to stop or change treatment against doctors’ recommendations. These situations often created conflicts and disappointment as navigators tried to validate and support patients’ choices while promoting completion of recommended cancer treatment as they were trained to do. See Table 1 for sample quotes illustrating navigation process factors.

Patient Factors

Patient characteristics varied greatly and influenced the navigation process. These characteristics included health beliefs and behaviors, health literacy, communication and relational styles, and quality of life. We classified patient factors as facilitative, neutral or inhibitory/maladaptive in relation to their effects on the process of cancer care. Patients with facilitative characteristics (e.g., higher level of motivation or independence) were more likely to participate actively in PN processes and their cancer care than those with maladaptive characteristics (e.g., lower level of motivation, passivity, cognitive impairment, fear or mistrust, distrust of the healthcare system, severe co-morbidities). Patients who had the greatest navigation needs often were those who were least willing or able to engage in PN. The navigators characterized these patients as passive, unable to follow through, or reluctant to pursue treatment, and provided convincing examples of patient behavior. Navigators identified or implied that reasons why patients did not engage included lack of relevant health/healthcare knowledge and helpless or hopelessness often noted among underserved and poor patients facing cancer without adequate financial, healthcare and socioeconomic support. In these situations, navigators’ skills in building trust, rapport and understanding, as well as their ability to problem-solve were tested. See Table 2 for sample quotes illustrating patient factors.

Table 2.

Sample Quotes Illustrating Patient Factors

| Facilitative Patient Characteristics | “I gave her information and she would run with it. She wanted the information but she would take care of it herself. She was more proactive than some people” |

| “She went to groups… she borrowed countless books from the library”. | |

| Fear | “She was nervous cause she had breast cancer and it was scary, she was very scared and she leaned on the navigator a lot. It was like her only support person at the time”. |

| “she has a bad heart, she had stints placed in her heart, and she wasn’t sure that if she stopped taking the medicine to be able to have the surgery she would even be able to survive”. | |

| “Then something happened again with her heart, where she felt … that her heart was like beating too fast … she stopped taking the (medication) and there was nothing this time that I could tell her to make her change her mind”. | |

| Lack of Engagement | “I would go to Strong and I would wait for her and she would not show up. And she would not come. …She really didn’t want to do the surgery. And I kept on calling her, and she would avoid me, she wouldn’t answer my phone calls”. |

| “That was hard in the beginning because she wasn’t really reaching out for help and she didn’t ask, she didn’t ask us”. | |

| Passive | “He didn’t know how to ah, ah be assertive with you know. Proactive I should, I guess is the right word with, you know, getting what he wanted”. |

| Mistrust | “He’s mad at the doctors ‘cause he feels like, … how can he be sure that they’re [interpreters] really saying what he’s saying. He doesn’t understand English and he felt like his cancer could have been diagnosed earlier if the interpreter would have correctly interpreted what he was saying, his symptoms to the doctor”. |

| “…she didn’t like to go to appointments, she didn’t trust the doctor…”. | |

| “…she was cutting it in half and only taking half of the medicine…And she only took it for like three or four days and she was attributing all these side effects to it… She had horrible side effects from it and um, she didn’t like her medical oncologist at all”. | |

| Disorganized | “She could not really remember when her appointments were, and who they were with, and what they were for. And even though she was having chemo and she came every three weeks, she still couldn’t remember when it was, and who she saw last time”. |

| “Cause she was like a mess. She was always in crisis. So, just getting her organized, OK, we are going to do this today. Or, no, she had a doctor’s appointment (inaudible), so OK, you have a doctor’s appointment. I would have to call her like two (2) days beforehand and say like, you know, you have an appointment two (2) days from now at this time, do you have money to get on, to get Lift Line, are you going to call Lift Line, you got to remember to call Lift Line. You know, I would have to almost, …like I was kinda like her mother. I’d have to call her and, you sure you’re going to come, and sometimes she would, I would call her the two (2) days before she told me she was going to come and she wouldn’t show up and I’d do wait for her and she wasn’t there”. | |

| Co-morbidities | “She had a lot of other, um, co-morbidities besides having breast cancer. So, a lot of times she was sick. So, she couldn’t make appointments because she was sick”. |

| “…she was cognitively impaired as well…it was a stroke… She has difficulty understanding what you say… I would take notes for her and explain things to her because she had a lot of literacy issues as well”. |

Navigator Factors

The interviews provided insight into key navigator characteristics and behaviors that influence PN processes and outcomes: persistence, assertiveness and ability to balance program goals with patients’ needs, flexibility, and the ability to empathize with patients. Persistence and assertiveness were mentioned many times in various contexts, including when dealing with patients reluctant to accept help, a dysfunctional medical system, or with third parties such as insurance companies. Navigators reported many other challenges that required flexibility, including having to get out of their comfort zone and asking difficult questions, adjusting to age or gender differences, or even driving to unfamiliar places. Other challenges included being able to understand their own limitations and knowing when their work was over.

Navigators’ reactions to patients emerged as an important characteristic during the interviews. Navigators reported that they noted their initial reactions (i.e., positive or negative) towards patients and then adjusted their intervention strategies to be able to provide adequate PN services to all patients. Positive reactions included seeing patients as pleasant, proactive, having a sense of humor, and feeling comfortable dealing with the patient with whom navigators shared ethno-cultural values. On the other hand, the most common negative reactions recorded by navigators were frustration, especially when the navigator’s advice was not heeded. In these instances, sometimes navigators reported feeling hurt, disappointed or rejected – especially before they had gained experience with a wide variety of patients. The major source of frustration related to patients who could benefit from health care but simply did not show up for appointments or did not follow through in other ways. See Table 3 for sample quotes illustrating navigator factors.

External Factors

Social support emerged as a key external factor influencing patients’ attitudes and participation in their own healthcare. Patients who had more positive social support (e.g., families and friends participating in their healthcare, attending appointments, helping patients by asking physicians pertinent questions, participating in decision making, and providing emotional support) also tended to report positive healthcare experience than patients who lacked social support (e.g., having discouraging families/spouses or friends with negative feedback about healthcare). In many instances, negative and/or lack of social support was mitigated by navigators serving supportive roles for patients. Other external barriers included financial difficulties, lack of or insufficient healthcare insurance coverage and limited healthcare access also influenced patients’ cancer care experience. Finally, the medical system itself at times served as barriers to care (e.g., difficulty scheduling tests and communication problems with the healthcare team). See Table 3 for sample quotes illustrating external factors.

Emerging Conceptual Framework of PN

We considered four types of outcomes of navigation: patient behavioral outcomes, (e.g., adherence to recommended treatment), clinical endpoints (e.g., completion of recommended treatments), patient satisfaction with care, and patient satisfaction with navigation. We found evidence that navigation could affect all of these outcomes and that perception of usefulness of treatment influenced satisfaction. We also found that navigation processes (e.g., removing barriers, building relationships between patients and healthcare providers, and facilitating access to care and treatment adherence) influenced outcomes (e.g., treatment adherence and patient satisfaction). Relationships between patient navigation processes and outcomes were dependent upon patient factors (e.g., personal characteristics and attitudes towards healthcare), navigator factors (e.g., ability to set boundaries, be assertive, flexible, and persistent) and external factors (e.g., social support, medical insurance, transportation) (See Figure 1). We present this as a tentative framework, pending larger studies and studies in other contexts.

Figure 1.

Relationship between navigation process factors and outcomes as influenced by navigators, patients and external factors

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study was designed to identify key processes and domains of PN from navigators’ perspectives from the field. We found that two broad types of interventions contribute to successful PN: (1) instrumental interventions to identify and meet patients’ needs such as insurance, transportation and disease-related information, and (2) relationship interventions that enhance patient-navigator and patient-clinician relationships. These relational aspects have as their goals enhancing trust, building rapport and mutual understanding, providing psychosocial support and enabling patients to participate more actively in patient-physician consultations. To our knowledge, this is the first publication that explores navigators’ views about navigator-patient relationships. The conceptual framework that emerged from our analysis describes ways in which navigator, patient and external factors influence the relationship between navigation processes and outcomes. This preliminary model may be useful in guiding the development of new PN programs.

Previous studies have shown that racial/ethnic minorities and the poor generally confront many challenges or barriers to receiving optimal cancer care because of unavailability and inaccessibility to reliable healthcare resources in their communities. Consequently, PN has been conceptualized as an instrumental intervention identifying specific system barriers to linking patients with reliable cancer care services in a timely fashion. However, achieving instrumental tasks – assisting patients with healthcare insurance issues, obtaining transportation, and coordinating care – often happened behind the scenes, without patients’ knowledge.

This qualitative study was intended to generate Navigators’ accounts emphasized that relational skills are essential for the achievement of instrumental goals. Building a trusting relationship helps reluctant patients engage in care, follow up with appointments and express their needs. Navigator-patient relationships bolster social support and foster strong patient-clinician relationships. Navigators reported helping patients formulate pertinent questions and discuss issues related to their cancer care with their healthcare providers. These interventions were especially important when patients’ beliefs or the beliefs of their family members conflicted with physicians’ recommendations. Social support was provided by accompanying patients to appointments, visiting them in their homes and often by letting patients know that they were not alone and that the navigator was available if needed. Accompanying patients during an often terrifying and uncertain illness journey helped strengthen the navigator-patient relationship and facilitated completion of treatment. In addition, PN sometimes involved challenging conflicts, such as communication barriers with healthcare professionals, patient mistrust of physicians or the healthcare system, or patient reluctance to accept recommended treatments.

LIMITATIONS

Our conceptual framework of PN is provisional and subject to refinement based on future studies in different contexts. In addition, while the present study provides insight into the process of PN, it only includes navigators as informants. We interviewed all three navigators in our PN program at the University of Rochester. However, it is possible that navigators in other sites and with different personal characteristics would inform the generalizability of our findings. Further, it is plausible that in some instances navigators’ impressions of patients’ needs may not match patients’ perspectives on their own needs, and they may paint a biased picture of their own actions and effectiveness. Nonetheless, a previously published study by our group that examined the influence of navigation on patients’ perspectives on the quality of their cancer care found that newly diagnosed breast or colorectal cancer patients value many important aspects of patient navigation including emotional support, assistance with information needs and problem-solving and logistical coordination of cancer care.20 Furthermore, there is a great deal of heterogeneity amongst PN programs across the United States. Our findings apply most readily to a type of intensive and patient empowerment focused PN program. Importantly, we only had a small number of informants , who differed in small ways in their perspectives..

CONCLUSION

The findings from this qualitative study with patient navigators underscore the importance of both instrumental and relational aspects of PN. The preliminary framework for a descriptive taxonomy of navigators’ experiences that emerged from our analysis may provide guidance for future efforts to eliminate disparities in cancer care for racial/ethnic minorities and poor individuals, and might facilitate comparison and improvement of processes and outcomes across different PN programs. Future studies should examine ways to tailor navigation approaches to different contexts in which underserved, racial/ethnic minority and impoverished people with cancer are receiving less-than-optimal care.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Cancer Institute public health service grants: 5U01CA116924-04S1; U01CA116924-04S2; and 1R25CA10261801-A1

REFERENCES

- 1.Estachon J, Armour B, Ofili E, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care. JAMA. 2001;285:883. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.7.883-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiscella K, Franks P, Gold MR, et al. Inequality in quality: addressing socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic disparities in health care. JAMA. 2000;283:2579–2584. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. The future of the public’s health. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care Appendix C: Federal-Level and Other Initiatives to Address Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare (384 – 391) Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socioeconomic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:813–828. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Disparities in cancer diagnosis and survival. Cancer. 2001;91(1):178–188. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1<178::aid-cncr23>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaVeist TA. “Segregation, poverty, and empowerment: health consequences of African Americans.”. In: LaVeist TA, editor. Race, ethnicity, and health: A public Health Reader. San Franscisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roetzheim RG, Pal N, Tennant C, et al. Effects of health insurance and race on early detection of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1409–1915. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.16.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gornick ME, Eggers PW, Riley GF. Associations of race, education, and patterns of preventive service use with stage of cancer at time of diagnosis. Health Services Research. 2004;39:1403–1428. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griggs JJ, Culakova E, Sorbero ME, et al. Social and racial differences in selection of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18):2522–2527. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shavers VL, Brown ML. Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2002;94:334–357. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.5.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper LA, Hill MN, Powe NR. Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:477–486. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Battaglia TA, Roloff K, Posner MA, et al. Improving follow-up to abnormal breast cancer screening in an urban population: A patient navigation intervention. Cancer Supplement. 2007;109(2):359–367. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman H. Patient Navigation: A community based strategy to reduce cancer disparities. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2006;83(2):139–141. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9030-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vargas RB, Ryan GW, Jackson CA, et al. Characteristics of the original patient navigation programs to reduce disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(2):426–433. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: current practices and approaches. Cancer. 2005;104(4):848–855. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995;3:19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petereit DG, Molloy K, Reiner ML, et al. Establishing a patient navigator program to reduce cancer disparities in the American Indian communities of South Dakota: Initial observations and results. Cancer Control. 2008;15(3):254–259. doi: 10.1177/107327480801500309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miles MB, Huberman AM. An expanded sourcebook – Qualitative data analysis (2/e) Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carroll JK, Humiston SG, Meldrum SC, Salamone CM, Jean-Pierre P, Epstein RM, Fiscella K. Patients’expectation with navigation for cancer care. Patient Education Counseling. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.024. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]