Abstract

Recently, we characterized the functional properties of a mutant skeletal muscle L-type Ca2+ channel (CaV1.1 R174W) linked to the pharmacogenetic disorder malignant hyperthermia. Although the R174W mutation neutralizes the innermost basic amino acid in the voltage-sensing S4 helix of the first conserved membrane repeat of CaV1.1, the ability of the mutant channel to engage excitation-contraction coupling was largely unaffected by the introduction of the bulky tryptophan residue. In stark contrast, the mutation ablated the ability of CaV1.1 to produce L-type current under our standard recording conditions. In this study, we have investigated the mechanism of channel dysfunction more extensively. We found that CaV1.1 R174W will open and conduct Ca2+ in response to strong or prolonged depolarizations in the presence of the 1,4-dihydropyridine receptor agonist ±Bay K 8644. From these results, we have concluded that the R174W mutation impedes entry into both mode 1(low Po) and mode 2 (high Po) gating states and that these gating impairments can be partially overcome by maneuvers that promote entry into mode 2.

Introduction

The principal α1S subunit (CaV1.1) of the skeletal muscle L-type Ca2+ channel is a single polypeptide composed of four conserved domains (RI–RIV), each consisting of six transmembrane segments (S1–S6); the amino- and carboxyl-termini and the linkers joining the repeats are all cytoplasmic (1). Like other CaV family channels, the primary voltage-sensing structures for CaV1.1 are the S4 helices of each transmembrane repeat (1,2). It has been established that regularly spaced basic residues within a given S4 helix translocate with respect to the electrical field across the plasma membrane in response to depolarization (3). In the unique case of CaV1.1, the movement of the S4 helices is directly responsible for triggering voltage-induced Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) (i.e., skeletal-type excitation-contraction (EC) coupling (4–7)). In addition, the movement of the S4 helices causes further conformational rearrangements in the channel, which are coupled to opening of the pore allowing Ca2+ flux into the myoplasm (6). For CaV1.1, movement of the RI S4 voltage-sensing helix has been identified as a likely rate determining step in channel activation (8–10).

Like other L-type channels, CaV1.1 has three broadly defined gating modes (11). Mode 0 is characterized by null single channel sweeps and is indicative of the closed state of the channel, mode 1 has very brief (∼1 ms), infrequent openings, and mode 2 displays openings with longer dwell times, which are induced by strong depolarization and/or by exposure to 1,4-dihydropyridine agonists such as (−)Bay K 8644 (11–14). On the whole-cell level, entry into mode 2 is manifested by the enhanced amplitude, and decelerated decay, of tail currents upon repolarization.

We (15) have recently described the impact of a malignant hyperthermia-linked mutation in CaV1.1 (R174W; see (16)) on the functional properties of the channel. Although this mutation occurs at the innermost basic residue of the RI S4 helix (1–3), the intramembrane charge movement generated by depolarization was very similar to that of wild-type CaV1.1, as was the ability of the R174W mutant to engage EC coupling. In stark contrast, the R174W mutation virtually ablated the ability of CaV1.1 to produce L-type Ca2+ current during 200 ms depolarizations. These earlier findings have raised the question of whether this disease-causing mutation renders the channel completely incapable of opening. Here, we have addressed the question by investigating the gating behavior of CaV1.1 R174W in response to manipulations known to cause wild-type CaV1.1 channels to enter into a gating mode of higher open probability. We have found that CaV1.1 R174W will produce inward current under these conditions, although the entry into mode 2 requires stronger depolarization and occurs much more slowly.

Materials and Methods

Myotube culture and cDNA expression

All procedures involving mice were approved by the University of Colorado Denver-Anschutz Medical Campus Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Primary cultures of dysgenic (mdg/mdg) myotubes were prepared as described previously (17). Cultures were grown for 6–7 days in a humidified 37°C incubator with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; #15-017-CM, Mediatech, Herndon, VA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum/10% horse serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT). This medium was then replaced with differentiation medium (DMEM supplemented with 2% horse serum). 2–4 days following the shift to differentiation medium, single nuclei were microinjected with 200 ng/μl plasmid cDNA encoding either YFP-CaV1.1 (18) or YFP-CaV1.1 R174W (15). Fluorescent myotubes were used in experiments 2 days following microinjection.

Measurement of Ca2+ currents

All experiments were performed at room temperature (∼25°C). Pipettes were fabricated from borosilicate glass and had resistances of ∼2.0 MΩ when filled with internal solution, which consisted of (mM): 140 Cs-aspartate, 10 Cs2-EGTA, 5 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 with CsOH. The standard external solution contained (mM): 145 tetraethylammonium (TEA)-Cl, 10 CaCl2, 0.002 tetrodotoxin, 0.01 N-Benzyl-P-toluensulfonamide (#S949760, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 with TEA-OH. In some experiments, ±Bay K 8644 was included in the external solution. For the generation of current-voltage relationships, linear capacitative and leakage currents were determined by averaging the currents elicited by 11, 30 mV hyperpolarizing pulses from the holding potential of −80 mV. Test currents were corrected for linear components of leak and capacitive current by digital scaling and subtraction of this average control current. In all other experiments, −P/4 subtraction was employed. Electronic compensation was used to reduce the effective series resistance (usually to <1 MΩ) and the time constant for charging the linear cell capacitance (usually to <0.5 ms). L-type currents were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 5–10 kHz. In some cases, a 1 s prepulse to −20 mV followed by a 50 ms repolarization to −50 mV was administered before the test pulse (prepulse protocol; see (19)) to inactivate Na+ and T-type Ca2+ channels. Cell capacitance was determined by integration of a transient from −80 to −70 mV using Clampex 8.0 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and was used to normalize current amplitudes (pA/pF).

Pharmacology

Racemic Bay K 8644 (kindly supplied by Dr. A. Scriabine, Miles Laboratories, New Haven, CT) was stored at 4°C as a 20 mM stock in 50% EtOH, diluted to 10 μM just before use, and used in the dark.

Analysis

Figures were made using the software program SigmaPlot (version 11.0, SSPS, Chicago, IL). All data are presented as mean ± SE. Statistical comparisons were made by unpaired, two-tailed t-test or by one-way ANOVA (as appropriate), with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Tail currents of wild-type CaV1.1 channels are potentiated by Bay K 8644

As has been extensively documented, wild-type YFP-CaV1.1 produced robust, L-type currents during 200 ms depolarizations, and the subsequent tail currents increased in amplitude as a function of the prior test pulse (Fig. 1, A and C; cf. Fig. 3 C of (20)). The decay rate of the tail currents was similar upon repolarization to −50 mV following steps to either +20 or +40 mV (t1/2-deact = 1.4 ± 0.2 ms vs. 1.7 ± 0.2 ms, respectively; p > 0.05; Fig. 1 D), demonstrating that the wild-type channel resides in a similar gating state (i.e., predominantly mode 1) in this range of potentials. As the prior test depolarization was increased from +40 to +90 mV, there was a prominent slowing of tail current decay (to t1/2-deact = 2.5 ± 0.2 ms; p < 0.05, ANOVA), which is indicative of entry of the channels into a longer duration open state (i.e., mode 2). Application of the 1,4-dihydropyridine agonist ±Bay K 8644 (10 μM) to dysgenic myotubes expressing YFP-CaV1.1 further increased tail current amplitude and caused a substantial slowing of the tail current (see Fig. 1 B). Specifically, tail current density upon repolarization from +90 to −50 mV increased from −50.1 ± 8.6 pA/pF (n = 18) to −106.5 ± 17.4 pA/pF (n = 10; p < 0.005, unpaired t-test; Fig. 1 C) and the half-time of tail current decay increased from 2.5 ± 0.2 ms to 28.7 ± 8.8 ms (p < 0.001, unpaired t-test; Fig. 1 D) in the presence of ±Bay K 8644.

Figure 1.

Potentiation of wild-type CaV1.1 tail currents by Bay K 8644. Representative currents evoked by the illustrated voltage protocol are shown for dysgenic myotubes expressing YFP-CaV1.1 in the absence (A) and the presence (B) of ±Bay K 8644 (10 μM). The currents elicited by depolarization to +40 or +90 mV are indicated in green and red, respectively, with the tail currents upon repolarization to −50 mV shown on an expanded time base in the insets in A and B. (C) Summary of amplitudes of YFP-CaV1.1 tail currents recorded in the absence (♦; n = 18) and presence (⋄; n = 10) of ±Bay K 8644. (D) Summary of half-times of YFP-CaV1.1 tail current decay recorded in the absence (left panel) and presence (right panel) of ±Bay K 8644. Asterisks indicate significant differences (* denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.005, *** denotes p < 0.001, unpaired t-test in C and ANOVA for both panels in D). Bars represent mean ± SE throughout.

Potentiated CaV1.1 R174W conducts inward Ca2+ current

As we demonstrated previously (15), YFP-CaV1.1 R174W was incapable of producing inward current during 200 ms step depolarizations and the inward currents generated by repolarization to −50 mV were small and did not show slowed decay as the test depolarization was increased from +40 to +90 mV (Fig. 2 A). Indeed, the inward and outward transient currents at the onset and offset of the depolarizing step roughly mirrored one another, consistent with the idea that both were generated by membrane-bound charge movement and that YFP-CaV1.1 R174W produces neither mode 1 nor mode 2 openings in response to 200 ms depolarizations. Fig. 2 B shows a recording from another dysgenic myotube expressing YFP-CaV1.1 R174W in the presence of ±Bay K 8644. Similar to the recordings made in the absence of ±Bay K 8644, very little inward step current was evoked during 200 ms depolarizations. However, large, slowly decaying tail currents were evident upon repolarization from test potentials > +50 mV (Fig. 2, B and C). In particular, the average amplitude of tail currents elicited by repolarization from +90 to −50 mV was augmented nearly fourfold by exposure to ±Bay K 8644 relative to that of untreated dysgenic myotubes expressing YFP-CaV1.1 R174W (−31.8 ± 6.6 pA/pF; n = 9 vs. −7.7 ± 1.0 pA/pF; n = 5; p < 0.005, unpaired t-test). Likewise, tail current deactivation recorded in the presence of ±Bay K 8644 was substantially slowed compared to the deactivation of tail currents recorded from untreated cells expressing YFP-CaV1.1 R174W (t1/2-deact =1.9 ± 0.2 ms vs. 5.0 ± 0.5 ms; p < 0.001, unpaired t-test; Fig. 1 D). Importantly, the tail current amplitude in ±Bay K 8644-treated, YFP-CaV1.1 R174W-expressing dysgenic myotubes was considerably greater than in naive, ±Bay K 8644-treated dysgenic myotubes (Fig. 1, C and D), indicating that the augmented tail currents of the former did not arise from the endogenous L-type current of dysgenic myotubes (Idys; see (21)).

Figure 2.

Potentiated CaV1.1 R174W conducts inward Ca2+ tail current. Representative currents evoked by the illustrated voltage protocol are shown for dysgenic myotubes expressing YFP-Cav1.1 R174W in the absence (A) and the presence (B) of ±Bay K 8644 (10 μM). The currents elicited by depolarization to +40 or +90 mV are indicated in green and red, respectively, with the tail currents upon repolarization to −50 mV shown on an expanded time base in the insets in A and B. (C) Summary of amplitudes of YFP-CaV1.1 R174W tail currents recorded in the absence (●; n = 9) and presence (○; n = 10) of ±Bay K 8644. Also shown in panel C are the corresponding control data for naive dysgenic myotubes in the presence of ±Bay K 8644 (●; n = 6). (D) Summary of half-times of YFP-CaV1.1 R174W tail current decay recorded in the absence (black bars) and presence (white bars) of ±Bay K 8644. Asterisks indicate significant differences (* denotes p < 0.05; ** denotes p < 0.005; *** denotes p < 0.001, ANOVA in both C and D).

A fraction of the repolarization current observed in the presence of ±Bay K 8644 most certainly was attributable to membrane-bound gating charge movement (see above). However, based on the reasoning described below, this component was likely to have been insignificant. Specifically, in the absence of ±Bay K 8644, Qon and Qoff were similar to one another, both for YFP-CaV1.1 and YFP-CaV1.1 R174W (see Fig. 1 of (15)). Also in the absence of ±Bay K 8644, Qon was similar for YFP-CaV1.1 and YFP-CaV1.1 R174W (15). Furthermore, Qon for R174W was little affected by ±Bay K 8644 (6.3 ± 0.7 nC/μF, n = 7 vs. 5.8 ± 0.8 nC/μF, n = 10; p < 0.05, unpaired t-test). Thus, the contribution of Qoff (∼6 nC/μF) to the integrated current produced by repolarization from +90 to −50 should have been minor for both YFP-CaV1.1 and YFP-CaV1.1 R174W (3464.5 ± 1437.0 nC/μF and 249.5 ± 69.1 nC/μF, respectively). Taken together, the results of Figs. 1 and 2 show that wild-type CaV1.1 channels exhibit both mode 1 and mode 2 gating during 200 ms step depolarization in the absence of Bay K 8644 (Fig. 1), whereas CaV1.1 R174W channels are incapable of these transitions without agonist (Fig. 2).

Strong depolarization in the presence of ±BayK 8644 causes CaV1.1 R174W to gate into mode 2 openings

Large, slowly decaying tail currents for YFP-CaV1.1 R174W were apparent following depolarizing test potentials greater than about +50 mV (see Fig. 2, B–D), suggesting that the combined application of agonist and strong depolarization were driving the channel into mode 2 gating. To test this idea, we used the voltage protocols illustrated at the top of Fig. 3 in which we compared the current at +60 mV recorded following 200 ms depolarizations to either +60 or +90 mV in the presence of ±Bay K 8644. When the membrane potential was maintained at +60 mV following the initial 200 ms depolarization in this representative experiment, there was a subtle hint of inward Ca2+ current (Fig. 3, black trace). However, substantial inward Ca2+ current was apparent upon repolarization to +60 mV following the 200 ms depolarization to +90 mV (−4.9 ± 1.2 pA/pF vs. 0.2 ± 0.3 pA/pF, n = 6, p < 0.005; Fig. 3, red trace), indicating entry of the channel into a higher Po state.

Figure 3.

After strong depolarization in the presence of ±Bay K 8644, CaV1.1 R174W produces long-lasting inward Ca2+ current. Currents from a YFP-CaV1.1 R174W-expressing dysgenic myotubes were elicited by an initial 200 ms step depolarization to either +60 mV (black trace) or +90 mV (red trace), followed by 100 ms at +60 mV, before final repolarization to −20 mV (illustrated at top). Note the substantial, sustained inward current recorded at +60 mV following the step to +90 mV and the enhanced tail current upon repolarization to −20 mV. Similar behavior was observed in a total of six cells (see text).

CaV1.1 R174W channels open during long depolarizations in the presence of ±BayK 8644

In addition to strong depolarizations, long depolarizations can also drive L-type channels into mode 2 gating (14). As shown in Fig. 3, a hint of inward current began to develop near the end of 300 ms long depolarizations to +60 mV. In light of this observation, we investigated whether significant current via YFP-CaV1.1 R174W could be evoked by 2 s long depolarizations in the presence of ±Bay K 8644. To this end, we observed inward currents of variable amplitude in five dysgenic myotubes expressing YFP-CaV1.1R174W (−0.66 ± 0.41 pA/pF); Fig. 4 A shows a family of currents recorded from one of these cells. In this particular myotube, the current density at the end of the 2 s depolarization from −50 to +50 mV was −2.2 pA/pF. The activation of the current in dysgenic myotubes expressing YFP-CaV1.1 R174W was quite slow in comparison to dysgenic myotubes expressing YFP-CaV1.1 (Fig. 4 B; t1/2-act = 9628 ± 144 ms, n = 4 vs. 53.2 ± 21.9 ms, n = 8, respectively; p < 0.005). In control experiments, only outward current was observed in naive dysgenic myotubes (n = 4; data not shown).

Figure 4.

CaV1.1 R174W opens in response to long depolarizations in the presence of ±Bay K 8644. Recordings of Ca2+ currents elicited by 2 s depolarizations from −50 mV to the indicated test potentials are shown for dysgenic myotubes expressing either YFP-CaV1.1 (A) or YFP-CaV1.1 R174W (B).

Discussion

In agreement with many previous studies, wild-type CaV1.1 (Fig. 1 A) displayed slowly activating inward Ca2+ current during 200 ms depolarizations, which represent predominantly mode 1 gating for test potentials up to around +40 mV, as indicated by rapid deactivation of the tail currents upon repolarization. Additionally, exposure to Bay K 8644 or depolarizations to potentials greater than about +40 mV caused mode 2 gating of wild-type CaV1.1, as indicated by increased tail current amplitude and slowed tail current decay (Fig. 1, B–D). By contrast, 200 ms depolarizations over the same voltage range failed to cause either mode 1 or mode 2 gating of CaV1.1 R174W (Fig. 2 A). Even in the presence of the 1,4-dihydropyridine agonist ±Bay K 8644, little or no inward Ca2+ current via CaV1.1 R174W occurred during 200 ms depolarizations, although test potentials > +40 mV caused mode 2 gating, as indicated by slowly deactivating, inward, Ca2+ current upon repolarization (Fig. 2, B–D, Fig. 3). However, the ability of CaV1.1 R174W to transition from mode 0 to mode 2 was impaired even in the presence of Bay K 8644, such that its entry into mode 2 required stronger depolarization (compare Figs. 1 C and 2 C). Despite the case that entry into mode 2 was strongly impaired for CaV1.1 R174W, there was sufficient entry into mode 2 in the presence of ±Bay K 8644 that very slowly activating inward currents were observed during prolonged (2 s) depolarizations (Fig. 4).

Previously, we showed that although the R174W mutation suppressed inward current during 200 ms depolarizations, it had no significant effect on the voltage dependence of either membrane-bound charge movement or EC coupling Ca2+ release (15). The observation that the mutation had no effect on charge movement is consistent with our earlier work (10), which suggested that IS4 moves too slowly to produce a measureable charge movement upon depolarization. In regard to EC coupling, previous work had shown that voltage-gated Ca2+ release from the SR occurs for weak depolarization, and at a much faster rate, than activation of L-type current via CaV1.1 (6). Thus, it seems reasonable that the R174W mutation impairs mode 1 and mode 2 openings of CaV1.1 without affecting EC coupling.

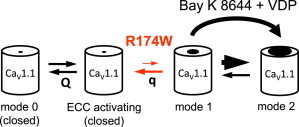

A number of publications (11–14,22) have described L-type Ca2+ channels as having three gating modes: mode 0 (deeply closed), mode 1 (brief openings), and mode 2 (long openings). Additionally, it has been proposed that there is a reversible transition between mode 0 and mode 1, between mode 1 and mode 2, and also between mode 0 and mode 2 (see (12 and 14), for detailed descriptions). Fig. 5 adapts this model to describe the transitions of CaV1.1 between modes 0, 1, and 2, the relationship of these gating modes to EC coupling, and the effects on intermodal transition caused by the R174W mutation and ±Bay K 8644. In particular, depolarizations that are subthreshold for activation of L-type current can nonetheless cause the rapid movement of sufficient charge (Q) to engage EC coupling within milliseconds (6). Further depolarization (≤ ∼40 mV) cause the slow movement of an additional, lesser charge (q), which causes the channel to enter predominantly mode 1, as indicated by the rapid decay of tail currents (Fig. 1). Because the R174W mutation ablates Ca2+ current during 200 ms depolarizations without affecting the voltage dependence of EC coupling, we propose that the mutation destabilizes mode 1. If mode 2 is predominantly entered from mode 1, then destabilization of mode 1 would account both for the absence of inward current during 200 ms depolarizations and the absence of a slowly decaying, Ca2+ tail current, even after depolarization to +90 mV, which causes the wild-type channel to enter mode 2. That is, the very brief sojourns in mode 1 would result in a negligible probability of entry into mode 2, the prerequisite for slowly decaying tail current. However, the combined actions of ±Bay K 8644 and strong/prolonged depolarization appeared able to overcome such brief spells in mode 1 by accelerating the transition from mode 1 to mode 2. As stated earlier, it has been proposed that mode 2 can also be entered directly from mode 0, although a rigorous experimental test of this proposition is difficult. However, if a significant fraction of entries into mode 2 occurred from mode 0, we would have to conclude that the R174W mutation is important for this transition as well. Independent of the precise mechanism, IS4 appears to be an important structural element for entry into both modes 1 and 2.

Figure 5.

Model for CaV1.1 R174W dysfunction. Mode 0 represents closed states of CaV1.1. Upon sufficient depolarization, the voltage sensors of both wild-type CaV1.1 and CaV1.1 R174W translocate within the membrane field producing the movement of charge (Q) and engage EC coupling, although the channel remains in mode 0. Stronger depolarization of sufficient duration causes the slow movement of additional charge (q) and entry into mode 1, in which the pore opens with low Po. Our present work indicates that the malignant hyperthermia-linked R174W mutation impairs the transitions necessary for the channel to enter mode 1. However, strong or prolonged depolarization in the presence of ±Bay K 8644 sufficiently accelerates the transition (big arrow) into higher Po mode 2 to overcome the gating impediment caused by the R174W mutation.

Based on the crystal structures of the bacterial Na+ channel NaVAb in the closed state (23) and an insect-based KV1.2/KV2.1 chimeric channel in the open state (24), R174 in the closed state of CaV1.1 is positioned below the highly conserved Phe gap phenylalanine in the adjacent S2 helix and must pass this aromatic residue for the channel to open (25). Our data are consistent with the idea that the introduction of a bulky tryptophan at position 174 strongly impedes movement of the repeat IS4 through the Phe gap, and thus stabilizes CaV1.1 in mode 0. Previously, we observed that a ryanodine-insensitive, SR Ca2+ leak in resting myotubes is increased in cells expressing CaV1.1 R174W compared to those expressing wild-type CaV1.1, which agrees with the idea that the resting conformation of CaV1.1 R174W differs from that of wild-type. Thus, both these earlier results and the results reported here are consistent with the idea that the R174W mutation produces a closed conformation of CaV1.1 that differs structurally and functionally from wild-type.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. O. Moua and Drs. J.D. Ohrtman, A.D. Polster, and H. Bichraoui for insightful discussion.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants NS24444 and 2P01 AR052354 (to K.G.B.), and AG038778 (to R.A.B.).

References

- 1.Tanabe T., Takeshima H., Numa S. Primary structure of the receptor for calcium channel blockers from skeletal muscle. Nature. 1987;328:313–318. doi: 10.1038/328313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujita Y., Mynlieff M., Beam K.G. Primary structure and functional expression of the ω-conotoxin-sensitive N-type calcium channel from rabbit brain. Neuron. 1993;10:585–598. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90162-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hille B. Gating: voltage sensing and inactivation. In: Hille B., editor. Ion channels of excitable membranes. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 2001. pp. 607–634. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider M.F., Chandler W.K. Voltage dependent charge movement of skeletal muscle: a possible step in excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 1973;242:244–246. doi: 10.1038/242244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ríos E., Brum G. Involvement of dihydropyridine receptors in excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. Nature. 1987;325:717–720. doi: 10.1038/325717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García J., Tanabe T., Beam K.G. Relationship of calcium transients to calcium currents and charge movements in myotubes expressing skeletal and cardiac dihydropyridine receptors. J. Gen. Physiol. 1994;103:125–147. doi: 10.1085/jgp.103.1.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beam K.G., Bannister R.A. Looking for answers to EC coupling’s persistent questions. J. Gen. Physiol. 2010;136:7–12. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.García J., Nakai J., Beam K.G. Role of S4 segments and the leucine heptad motif in the activation of an L-type calcium channel. Biophys. J. 1997;72:2515–2523. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78896-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanabe T., Adams B.A., Beam K.G. Repeat I of the dihydropyridine receptor is critical in determining calcium channel activation kinetics. Nature. 1991;352:800–803. doi: 10.1038/352800a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dirksen R.T., Beam K.G. Role of calcium permeation in dihydropyridine receptor function. Insights into channel gating and excitation-contraction coupling. J. Gen. Physiol. 1999;114:393–403. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox A.P., Nowycky M.C., Tsien R.W. Single-channel recordings of three types of calcium channels in chick sensory neurones. J. Physiol. 1987;394:173–200. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hess P., Lansman J.B., Tsien R.W. Different modes of Ca channel gating behaviour favoured by dihydropyridine Ca agonists and antagonists. Nature. 1984;311:538–544. doi: 10.1038/311538a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nowycky M.C., Fox A.P., Tsien R.W. Long-opening mode of gating of neuronal calcium channels and its promotion by the dihydropyridine calcium agonist Bay K 8644. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:2178–2182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.7.2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pietrobon D., Hess P. Novel mechanism of voltage-dependent gating in L-type calcium channels. Nature. 1990;346:651–655. doi: 10.1038/346651a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eltit J.M., Bannister R.A., Moua O., Hopkins P.M., Pessah I.N. Malignant hyperthermia susceptibility arising from altered resting coupling between CaV1.1 and RyR1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:7923–7928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119207109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpenter D., Ringrose C., Shaw M.A. The role of CACNA1S in predisposition to malignant hyperthermia. BMC Med. Genet. 2009;10:104–115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beam K.G., Franzini-Armstrong C. Functional and structural approaches to the study of excitation-contraction coupling. Methods Cell Biol. 1997;52:283–306. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60384-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papadopoulos S., Leuranguer V., Beam K.G. Mapping sites of potential proximity between the DHPR and RyR1 in muscle using a CFP-YFP tandem as a FRET probe. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:44056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams B.A., Tanabe T., Beam K.G. Intramembrane charge movement restored in dysgenic skeletal muscle by injection of dihydropyridine receptor cDNAs. Nature. 1990;346:569–572. doi: 10.1038/346569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bannister R.A., Grabner M., Beam K.G. The α(1S) III-IV loop influences 1,4-dihydropyridine receptor gating but is not directly involved in excitation-contraction coupling interactions with the type 1 ryanodine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:23217–23223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804312200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams B.A., Beam K.G. A novel calcium current in dysgenic skeletal muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 1989;94:429–444. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.3.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bannister R.A., Beam K.G. Properties of Na+ currents conducted by a skeletal muscle L-type Ca2+ channel pore mutant (SkEIIIK) Channels. 2011;5:262–268. doi: 10.4161/chan.5.3.15269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Payandeh J., Scheuer T., Catterall W.A. The crystal structure of a voltage-gated sodium channel. Nature. 2011;475:353–358. doi: 10.1038/nature10238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Long S.B., Tao X., MacKinnon R. Atomic structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid membrane-like environment. Nature. 2007;450:376–382. doi: 10.1038/nature06265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tao X., Lee A., MacKinnon R. A gating charge transfer center in voltage sensors. Science. 2010;328:67–73. doi: 10.1126/science.1185954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]