Abstract

The prostacyclin receptor (IP - International Union of Pharmacology nomenclature) is a member of the seven transmembrane G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily. Recent concerns with selective and non-selective COX-1/COX-2 inhibition have exposed an important cardioprotective role for IP in preventing atherothrombosis. Receptor dysfunction (genetic variants) or reduced signaling (COX-2 inhibition) in high cardiovascular risk patients leads to increased cardiovascular events. These clinical observations have also been confirmed genetically by mouse knockout studies. Thus, receptor regulation is paramount in ensuring correct function in the prevention of atherothrombosis. This review summarizes recent literature on how this important receptor is regulated, from transcription to transport (to and from the membrane surface). These regulatory processes are critical in ensuring that IP receptors are adequately expressed and functional on the cell surface.

Keywords: Prostacyclin receptor, activation, desensitization, dimerization, internalization, transcriptional regulation

PROSTACYCLIN IS CARDIOPROTECTIVE

For many decades prostacyclin (PGI2) has been recognized to play an important role in cardiovascular homeostasis and hemostasis. However, only recently has it emerged as a critical protective factor against atherothrombosis in human patients. Atherosclerosis is a complex inflammatory disease involving coronary, peripheral and/or cerebral arterial blood vessels and serves as the underlying cause for the majority of cardiovascular diseases and clinical cardiovascular events, including acute coronary syndrome (myocardial infarction and angina), as well as stroke [1]. It is estimated that 82,600,000 American adults (1 in 3) have 1 or more types of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) or atherosclerotic risk factors [1]. Many different blood and vascular cells are involved in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis, and the prostacyclin receptor (IP) is found in abundance on two key cell sub-types, namely platelets and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). Platelets are anucleate cell fragments derived from megakaryocytes that regulate vascular hemostasis, and in the context of heart disease, play a key role in thrombus formation, leading to myocardial infarction [2]. Platelets may also be involved in the earliest stages of atherosclerosis --- binding to endothelial cells at lesion-prone sites before any evidence of fatty streaks. This has been shown in several animal models, including rabbits with hypercholesterolemia [3] and atherosclerotic ApoE−/− knockout mice [4]. Additionally, vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) play an important role in the development of atherosclerosis whereby de-differentiation and proliferation contribute to the formation of plaques. Prostacyclin receptor (IP) activity has been shown to exert both anti-proliferative [5, 6] and anti-migratory [7] effects on vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). Moreover, in advanced atherosclerotic lesions (as well as restenotic lesions), expression levels of smooth-muscle-specific differentiation markers are significantly reduced [8, 9]. Recent studies of prostacyclin signaling in VSMCs have shown that IP receptor activation induces VSMC differentiation via the cAMP-PKA pathway [10]. Additional studies have shown that IP signaling --- via activation of PKA and ERK-1/2, as well as inhibition of Akt-1 --- up-regulates COX-2 expression. This, in turn, generates further PGI2 release, which acts on neighboring VSMCs in a paracrine manner [11].

Furthermore, the IP receptor appears to play a role in modulating coronary heart disease, as deficits in receptor function have been correlated with increased disease severity in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) [12]. In addition, knocking out the prostacyclin receptor gene (PTGIR) in mouse models of heart disease, such as the LDL-R−/− and ApoE−/− knockout models, leads to increased atherosclerotic lesion size [13, 14]. Interestingly, the receptor knockout in the LDL-R background led to increased lesion size in female mice, but not male mice [13]. Thus, platelet and VSMC surface expression of the prostacyclin receptor is critical for normal hemodynamic functioning, as well as protection against atherosclerosis. This review will summarize recent studies on prostacyclin receptor regulation.

PROSTACYCLIN RECEPTOR AND KEY POST-TRANSLATIONAL MODIFICATIONS REQUIRED FOR NORMAL CELL SURFACE TRAFFICKING

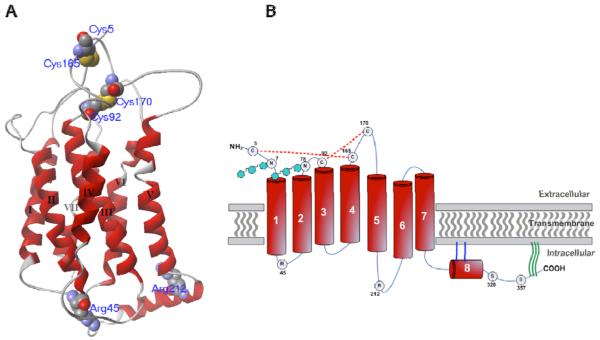

Within the circulatory system, the majority of PGI2 is synthesized by the vascular endothelium [15], beginning with the initial conversion of arachidonic acid (AA) into the unstable precursors prostaglandin G2 (PGG2) and H2 (PGH2) by the dual actions of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 (COX-1 and COX-2) isoenzymes. In a subsequent reaction, prostacyclin synthase converts PGH2 into PGI2. To carry out its physiological actions, PGI2 selectively binds and activates a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR), known as the prostacyclin receptor or IP receptor [16] [17, 18]. The IP receptor is a Class A, rhodopsin-type GPCR and, as such, maintains certain characteristic features of this protein class (Figure 1). The extracellular domain includes a small N-terminal region, along with 3 extracellular loops. The transmembrane domain consists of seven membrane-spanning alpha-helices, within which ligand binding is thought to occur [19, 20]. The intracellular domain consists of three intracellular loops, a putative intracellular eighth helix, lying parallel to the membrane [21], and a C-terminal tail [20] (Figure 1). Within each of these regions, a number of key post-translational modifications are required for normal receptor structure, function, and trafficking. These modifications include N-linked glycosylation, isoprenylation, palmitoylation, and disulfide bond formation. The human IP receptor contains two consensus sites for N-linked glycosylation at residues N7 and N78, which have been shown to be important for agonist-induced sequestration [22]. Also on the extracellular side of the hIP receptor, there exists a highly conserved disulfide interaction between C92 (top of transmembrane helix III) and C170 (second extracellular loop), as well as an additional, putative non-conserved disulfide bridge between C5 (N-terminus) and C165 (second extracellular loop), which have been shown to be critical for ligand binding, receptor activation, cell-surface expression, and trafficking [23](Figure 1). Lipid modification of the C-terminal tail of the receptor has been extensively studied. IP receptors from a number of different species contain the conserved CAAX isoprenylation motif (CSLC in mouse IP and CCLC in human IP), which has been shown to be important for G-protein coupling, effector signaling, and agonist-induced internalization [24, 25]. Subsequent studies have proposed that the IP receptor is also palmitoylated at its C-terminus, in addition to being isoprenylated [26]. More recent studies have proposed that C-terminal palmitoylation at C311 is crucial for positioning the putative eighth alpha-helix in proximity to Rab11, which is crucial for mediating agonist-induced intracellular trafficking of the IP receptor [21].

Figure 1. Secondary structure of human prostacyclin receptor.

A) Three-dimensional homology model of human prostacyclin receptor, based upon x-ray crystallographic structure of bovine rhodopsin (PDB code: 1HZX). Shown are major structural features including seven transmembrane-spanning alpha-helices (red, roman numeral designation), along with both extracellular (top gray) and intracellular loops (bottom gray). C-terminal tail is not included. Key residues are highlighted in space-filling motif (van der Waals radii) and labeled with three-letter amino acid designation. B) Two-dimensional representation of human prostacyclin receptor. Extracellular, transmembrane, and cytoplasmic regions are designated. Seven transmembrane-spanning alpha-helices, as well as putative eighth helix, are shown in red. Three extracellular and three intracellular loops are designated in light blue. The conserved (C92-C170) and putative (C5-C165) disulfide bonds are found in the extracellular domain and indicated with dashed red lines. N-linked glycosylation sites are represented by hexagonal shapes (N7 and N78). The putative isoprenylation and palmitoylation sites are located along the cytoplasmic tail of the receptor and indicated by dual, blue lines and triple, green waves, respectively. Shown in circles are key regulatory and functionally important amino acids (single-letter nomenclature) as described in text.

PROSTACYCLIN RECEPTOR TRANSCRIPTIONAL REGULATION

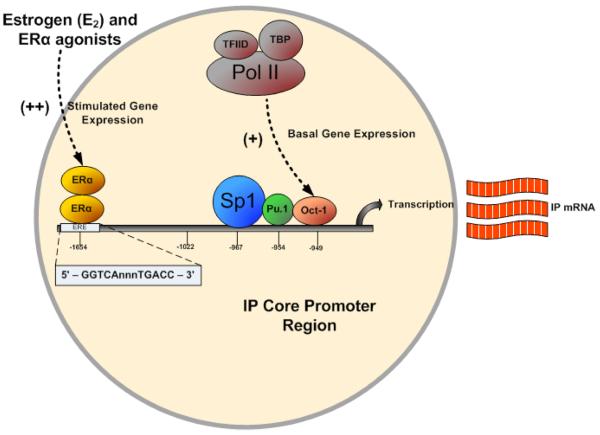

Recent studies have shown that basal transcription of the IP receptor is regulated by key trans-acting elements, including a consensus Sp1 element, a nearby PU box (PU.1), and an octamer binding element (Oct-1), all located within the essential core promoter of the IP receptor gene (PrmIP) [27](Figure 2). These sites were found within −1271 bases of the transcriptional initiation site. Disruption of each of these elements led to substantial reductions in promoter-directed gene expression in both megakaryoblastic human erythroleukemia (HEL) 92.1.7 and vascular endothelial EA.hy 926 cell lines [27]. In an additional study, an evolutionary conserved estrogen response element was also located within the promoter region (PrmIP)[28](Figure 2). Estrogen was found to increase the amount of IP mRNA in the same erythroleukemia (HEL 92.1.7) and endothelial (EA.hy926) cell lines. Moreover, this estrogen-induced signal increase was determined to be due to the ERα isoform of the receptor, and not ERβ. Treating human aortic smooth muscle cells (hASMC) with ERα agonists caused an increase in IP mRNA, along with cicaprost-induced cAMP generation, indicating an increased number of IP receptors [28]. While such studies are just beginning to probe the transcriptional regulation of the IP receptor, these results provide a glimpse into potential sex differences in the regulation of the receptor. Moreover, elucidation of an ERα-dependent transcriptional mechanism provides a means by which both PGI2 and estrogen mediate their atheroprotective effects within the vasculature.

Figure 2. Transcriptional regulation of human prostacyclin receptor gene.

Schematic showing the essential core promoter of the IP receptor gene within the nucleus. Transcription factors Sp-1, PU.1, and Oct-1 are shown as key initiating transcription factors involved in basal gene expression, when joined by other general components (e.g., RNA polymerase II, TBD, and TFIID). Also shown is evolutionary conserved estrogen response element (ERE), which participates in direct ERα-dependent induction of gene expression.

PROSTACYCLIN RECEPTOR ACTIVATION

Like all GPCRs, the IP directly activates heterotrimeric G-proteins for signal transduction. This complex is made up of three subunits --- Gα, Gß, and Gα --- all of which are involved in signal transduction. The Gα proteins exist in several isoforms that activate different downstream effector molecules. The G-stimulatory (Gαs) proteins activate adenylate cyclase (AC) to produce cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), the G-inhibitory (Gαi) proteins inhibit adenylate cyclase activity, while the Gαq proteins activate the inositol phosphate (Ins-P) pathway, leading to increased Ca2+ flux and protein kinase C (PKC) activation [29]. The Gα12/13 proteins interact with Rho-GEF proteins and affect cytoskeleton rearrangements [30]. Studies of the IP receptor have shown differences in coupling to G-proteins, depending upon cellular context and species sequence variations. Activating over-expressed IP receptors in human embryonic kidney (HEK) and simian kidney (COS) cells lead to increases in cAMP, Ins-P, and intracellular Ca2+ concentrations [20, 31–33]. Continued stimulation of the receptors leads to a decrease in the ability of forskolin (adenylate cyclase inducer) to stimulate cAMP production [33]. From the above studies, it has been inferred to mean that the IP couples to both Gαs and Gαq, and potentially Gαi in these expression systems. Alternative studies of endogenous IP receptors in neuroblastoma cells [34], pre-adipocytes [35] vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) [36], and platelets [37] have verified IP coupling to Gαs but not to Gαq. Thus, G-protein coupling can be cell-, species-, and expression-level-dependent. Interestingly, the mouse IP (mIP) receptor has been shown to couple to Gαi, which appears to be dependent upon cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) phosphorylation at S357 on the C-terminal tail of the receptor. However, the analogous serine in the human IP (hIP) receptor is not phosphorylated by PKA, but rather by PKC, and the phosphorylation of this residue does not seem to affect coupling to the G-proteins [31]. The culmination of these studies demonstrates the complexity of coupling experiments, and supports the well-accepted notion that endogenously-expressed human IP (hIP) receptor couples predominantly to the Gαs protein. Coupling to other G proteins may very well be, at least in part, due to hetero-dimerization (as will be described).

To better understand the IP receptor/G-protein interface, one study over-expressed “minigenes” encoding the IP intracellular loops, using an HEK cell line that had been engineered to express IP receptor [38]. The over-expression of the first and third intracellular loops inhibited cAMP production, implying that these loops are critical for coupling the receptor to the Gαs protein. To determine if this phenomenon also occurred in a more physiological setting, the loops were over-expressed in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells (hCASMCs), which endogenously express IP receptors. Again, the first and third loops inhibited agonist-induced cAMP production, further validating the importance of these structures for endogenous receptor signaling [38].

Focusing on the first intracellular loop, the particular amino acids important for this IP receptor/G-protein interaction were further explored using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy studies. Constrained synthetic peptides were constructed, mimicking both the putative first intracellular loop of the IP receptor and the C-terminal domain (11 residues) of the Gαs protein, and their interactions were assessed. The results suggested that IP residues R42, A44, and R45 directly interacted with the Gαs peptide. Further experiments using site-directed mutagenesis and COS-7 over-expression found that R45 and the residues surrounding it, R42 to A48, were important for receptor activation, suggesting that all of these residues --- with R45 at the center --- form an epitope that interacts with the Gαs protein. The interaction with R45 was found to be dependent upon the chemical nature of its side-chain and not simply related to its charge, as a lysine (K) substitution at this position was unable to rescue the receptor [39]. Solution structures of the constrained peptide loop and C-terminal segment of the Gαs have also shown that the R45 side-chain changes its orientation, from outside to inside the loop, while the C-terminus of the Gαs peptide loses its alpha-helical character, straightening out. These changes suggest that the first intracellular loop and the C-terminus of the Gαs interact [40]. While the first intracellular loop has been shown to be important for IP receptor activation, it is hard to reconcile the aforementioned IP solution structures with the crystal structures of bovine opsin (PDB code: 3DQB) and metarhodpopsin II (PDB code: 3PQR) in their G-protein-interacting conformations, both of which seem to place the first intracellular loop at quite a distance from the bound Gαs C-terminal fragment, which appears to interact with residues along transmembrane helices 5 and 6 [41, 42]. While the IP solution structures may depict a non-specific interaction, further studies into the molecular interactions among the first intracellular loop and the Gαs are needed to clarify this issue.

PROSTACYCLIN RECEPTOR DESENSITIZATION

Once GPCRs are activated, they generally become desensitized relatively quickly (usually on the order of minutes) in a two-step process. Therefore, even in the continued presence of agonists, the receptors are unable to signal. During the first step in desensitization, the intracellular loops and the C-terminal tail of the receptors become phosphorylated. This phosphorylation is carried out by either: 1) the G-protein receptor kinases (GRKs), a family of kinases that recognize and phosphorylate agonist-bound GPCRs, or 2) second messenger kinases, such as protein kinase A (PKA) and protein dependent kinase C (PKC). Since these second messenger kinases do not discriminate between active and inactive GPCRs, it is possible for an active receptor to cause an inactive receptor to become desensitized, a process termed heterologous desensitization [43]. After phosphorylation, proteins that recognize phosphorylated receptors in the active state bind to the receptor and sterically block the coupling of G-proteins. These blocking adapter proteins are generally members of the ß-arrestin family [43]. However, the GRKs have also been shown to be capable of GPCR desensitization by simply binding to the receptor [44]. In addition, other regulators of G-protein signaling such as calmodulin and PDZ domain-containing proteins have the potential to bind and desensitize GPCRs, without prior phosphorylation [44].

In the IP receptor, desensitization studies carried out in HEK-293 cells have shown that PKC-mediated phosphorylation of residue S328 within the C-terminal tail is required for receptor desensitization for both the cAMP and Ins-P responses [45](Figure 1). However, experiments using human fibroblasts demonstrated that the endogenously-expressed IP receptor was not desensitized by PKC, as phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA), an activator of PKC, and GF-109203X, a PKC inhibitor, had no effect on cAMP production [46]. In platelets, it has been suggested that the IP receptor is desensitized due to agonist-dependent decreases in cAMP production after agonist pre-stimulation [47, 48]. This is unlikely to be carried out by PKC as: 1) the IP receptor on platelets primarily activates adenylate cyclase (AC) [49], and 2) PKC is activated during platelet aggregation [50]. A complicating issue in assessing IP receptor desensitization using cAMP production is that it is an indirect measure of receptor desensitization and, furthermore, it has also been shown that adenylate cyclase (AC) itself undergoes desensitization [51]. In addition, temporal factors (i.e., long incubation times with IP receptor agonist) have also been shown to play a role in receptor internalization [47]. In light of this, another plausible explanation could be argued for decreased cAMP production, whereby pre-stimulation with agonist decreases the number of cell surface IP receptors, leading to a subsequent decrease in cAMP production when the platelets are again stimulated by agonist. As will be described, the desensitization process may be further complicated by homo- and heterodimerization. Considering the important role of IP receptor activity in maintaining vascular hemostasis and preventing aberrant platelet aggregation, further desensitization studies on endogenous proteins are warranted.

PROSTACYCLIN RECEPTOR INTERNALIZATION

After GPCRs are desensitized, they are re-distributed away from the cell surface in a process known as endocytosis. In the canonical pathway, ß-arrestin (silencer of G-protein-mediated signaling) binds to the GPCR, adapter proteins bind to ß-arrestin, then clathrin (lattice-forming protein) binds to the complex, and the receptors are internalized into the clathrin-coated vesicles (CCVs) for intracellular trafficking. These internalized GPCRs undergo one of two possible fates, involving either: 1) recycling back to the cell surface for another round of signaling or 2) degradation within lysosomes [52, 53]. The IP receptor has been shown to undergo agonist-dependent internalization. However, in HEK-293 cells, endocytosis of the IP receptor is independent of PKC-induced desensitization, GRK phosphorylation, and ß-arrestin binding. Nevertheless, sequestration in HEK cells is at least partially dependent upon clathrin-coated vesicles (CCVs), as endocytosis is incompletely blocked, using an over-expressed, inactive dynamin mutant [54]. Given the importance of internalization in regulating receptor activity, there have been attempts to identify proteins directly involved in the process.

Rab5a, a small GTPase (membrane-localized hydrolase enzyme), is involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis and has been shown to be involved in the internalization of several GPCRs, including β2-adrenergic and angiotensin 1A receptors [55]. As such, Rab5a was investigated as a potential mediator of IP receptor internalization. Although there is conflicting data regarding the involvement of Rab5a in receptor endocytosis, it is clear that IP is transported to Rab5a endosomes. Fluorescent imaging experiments in HEK cells showed the human IP receptor to co-localize with Rab5a after agonist exposure and, furthermore, Rab5a could also be co-immunoprecipitated with the IP receptor following treatment with agonist [56].

In other attempts to identify potential binding partners, yeast two-hybrid screens have been employed. Given that the C-terminal tail of the IP receptor has been implicated in receptor trafficking, as deletion of the C-terminal tail has been reported to either inhibit receptor internalization [54] or impair receptor trafficking [56], both screens made use of the C-terminal tail as bait. The first screen used a kidney cDNA library as prey and identified Rab11 as a potential partner. Rab11 was found to associate with the receptor by immunoprecipitation, and this association was increased in an agonist-dependent manner. Using confocal microscopy with wild-type Rab11, it was found that the IP receptor associated with Rab11 and then was recycled back to the cell surface in about four hours. A constitutively active mutant Rab11 prevented the receptor from recycling back to the membrane. In addition, a Rab11 loss-of-function mutant showed impaired association with the IP receptor along with defects in recycling, although not as severe as the constitutively active mutant. The region important to binding of Rab11 was mapped by yeast two-hybrid to the putative eighth helix [57]. To determine if the palmitoylation sites were important for Rab11 binding, a yeast two-hybrid approach was used with a mutant C-terminal tail and Rab11. This identified some of the cysteines involved in palmitoylation as important for Rab11 binding. The palmitoylation-deficient mutants were co-expressed with Rab11 in HEK cells and the mutant receptors were unable to co-immunoprecipitate with Rab11. Furthermore, confocal images showed deficient co-localization of the mutant receptors with Rab11 after agonist treatment [21]

The other yeast two-hybrid approach used the IP C-terminal tail as bait and a cDNA library from human aortic smooth muscle cells (hASMC) as prey. Using this library, the delta subunit of phosphodiesterase-6 (PDE6∂) was found to interact with the C-terminal tail. PDE6∂ is a prenyl-binding protein that originally has been found to solubilize lipid-modified proteins from membranes [58]. To understand how the PDE6∂ protein interacts with the IP receptor, PDE6∂ was expressed in HEPG2 liver hepatocellular carcinoma cells, which do not endogenously express either IP or PDE6∂. When the IP receptor and PDE6∂ were expressed together in the HEPG2 system, they could be co-immunoprecipitated. Moreover, this interaction seemed to be dependent upon prenylation of the IP receptor C-terminal tail. Interestingly, in the co-transfected cells, agonist-induced internalization of the IP receptor occurred within 15 minutes, which is much faster than what has been observed in HEK cells. Furthermore, the IP receptor appears to be recycled back to the surface, as surface expression was restored within 2 hours [59]. To examine if PDE6∂ is involved in receptor endocytosis, within an endogenous setting, PDE6∂ was knocked down using siRNA in hASMCs. This resulted in decreased agonist-dependent IP receptor internalization [59]. These results suggest that PDE6∂ may be important for IP internalization in certain vascular tissues. However, whether PDE6∂ plays a role in receptor endocytosis in platelets remains unknown.

Unfortunately, there is little known about agonist-induced IP receptor endocytosis in platelets. One study attempted to measure IP receptor internalization using a radiolabeled IP receptor selective agonist, iloprost. In this instance, platelets internalized the ligand, with most of the internalization occurring within two hours. Furthermore, iloprost internalization was blocked by incubating platelets at 4°C, as well as by utilizing metabolic inhibitors. In addition, the number of iloprost binding sites was reduced when the platelets were pre-incubated with the agonist [60]. These results suggest that the IP receptor is internalized in an agonist-dependent manner. In another study, platelets were treated with iloprost for two hours, after which the impact on platelet function was measured. After the incubation, the number of iloprost binding sites was reduced, however, platelet permeabilization was found to restore the binding sites, indicating the receptors were internalized. In addition, platelets were desensitized to iloprost, as measured by increased thrombin-induced P-selectin expression, platelet aggregation, and increased serotonin release. This desensitization to iloprost could be reversed after a three-hour re-sensitization period, with the number of iloprost binding sites being restored as well [47]. This implies that platelet desensitization to iloprost was a result of IP internalization, and not receptor desensitization. While the IP receptor is known to undergo internalization in platelets, there has not been a platelet-specific study to determine the proteins or pathways involved. Given the current evidence, it may be postulated that the IP receptor is removed from the cell surface, utilizing a clathrin-independent pathway, which may require PDE6∂ or a related protein.

PROSTACYCLIN RECEPTOR DEGRADATION

After agonist-induced phosphorylation, desensitization, and internalization, the human prostacyclin receptor may be recycled to the plasma membrane or targeted for degradation. Recent studies have shown that the hIP is ubiquitinated and targeted for lysosomal degradation [61]. This study demonstrated that inhibition of the lysosomal pathway prevented basal and agonist-induced degradation of the mature species of the hIP, indicating that this is the major regulatory pathway for the mature desensitized protein. Interestingly, inhibition of the proteasomal pathway led to the accumulation of four, newly-synthesized immature receptor species (38–44 kDa), supporting proteasomal degradation as being the major pathway for immature receptors. For those receptors not recycled, polyubiquitination is the presumed final step in the regulation of the prostacyclin receptor, although the exact mechanism and particular lysine residues involved are not known. Thus, while agonist-induced activation has been shown to promote rapid ubiquitination and lysosomal-mediated degradation for a number of GPCRs [62–64], with E3 ubiquitin ligase being a key mediator of ubiquitination, at least for the chemokine CXCR4 receptor [62], the determinants involved in IP receptor degradation have yet to be determined.

PROSTACYCLIN RECEPTOR DIMERIZATION

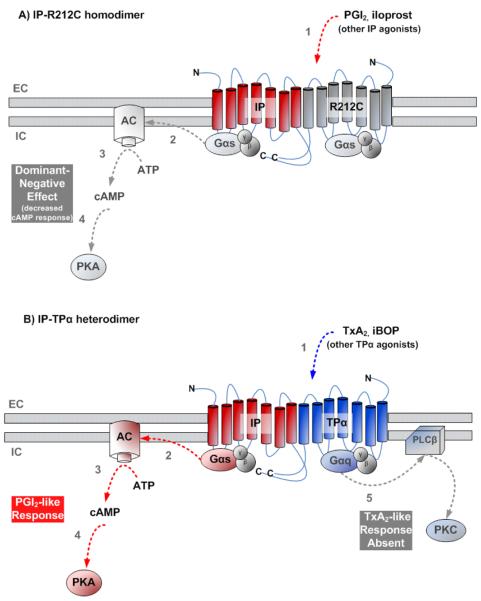

The evidence for GPCR dimerization (homo- and hetero-dimerization) is rapidly accumulating, and some postulate that dimerization affects not only ligand recognition and receptor activation [65], but trafficking and signaling as well [66]. The IP has been shown (by immunoprecipitation and western blot, using differentially labeled receptors) to homo-dimerize with itself, and may form higher order oligomers as well [67]. This homo-dimerization has been shown to be dependent upon disulfide bonds between cysteines on the N-terminus of the first extracellular loop with cysteines on the second extracellular loop, with possible disulfide links between C5 and C165, and between C92 and C170 [67](Figure 1). Disruption of the disulfide bonds results in reduced receptor expression and failure of the receptors to be transported to the cell surface [67]. This could occur because of protein misfolding or dimerization may indeed be required for proper receptor trafficking. Evidence for the latter may be seen in a recent study of wild-type and variant IP homo-dimerization, whereby an IP receptor variant (R212C) demonstrated a reduced ability to homo-dimerize with its wild-type counterpart, as determined using BRET [68]. Additionally, co-transfected wild-type and R212C mutant receptors demonstrated impaired cAMP production, compared to cells transfected with only the wild-type receptor (Figure 3A). Such results imply that, in addition to effects on ligand binding and receptor signaling, variant receptors with dominant-negative actions may also impair the ability of any available wild-type receptor to be trafficked to the cell surface.

Figure 3. Effects of human prostacyclin receptor dimerization.

A) Schematic showing wild-type and variant R212C prostacyclin receptor homo-dimerization, whereby stimulation with IP receptor agonists (1) results in decreased downstream activation of canonical transduction pathway elements (2, 3, and 4), due to the dominant-negative actions of the variant R212C receptor. B) Schematic showing prostacyclin-thromboxane receptor hetero-dimerization, whereby stimulation with TPα receptor agonists (1) elicits activation of prostacyclin-like pathway involving Gαs and adenylate cyclase (AC)(2) activation, which converts ATP to cAMP (3) to stimulate downstream effectors, such as PKA (4). Conversely, thromboxane-specific activation pathway is not induced in the context of hetero-dimerization (5).

Further investigations using co-immunoprecipitation of differentially-tagged receptors have shown that the IP receptor also hetero-dimerizes with the thromboxane A2 α receptor (TPα)[69], which serves to mediate the IP-opposing functions of vasoconstriction and induction of platelet aggregation in vivo [70]. When the TPα receptor is independently over-expressed in HEK-293 human embryonic kidney cells, it couples to Gαq (but not to Gαs) upon agonist stimulation to activate phospholipase C (PLC) and the inositol phosphate (Ins-P) pathway, leading to increased intracellular Ca2+ [71]. However, when both IP and TPα receptors were co-expressed in HEK-293 cells, it was found that activation of TPα receptors (using TPα ligands) elicited a “PGI2 like” cellular response, increasing intracellular cAMP (in a manner that appears to be IP-dependent)[69](Figure 3B). This was postulated to be a mechanism for IP-mediated inhibition of TP activity. Furthermore, support for IP-TPα hetero-dimerization as a physiologically-relevant phenomenon was shown using human and mouse aortic smooth muscle cells (ASMC), which both produce cAMP in response to TPα agonists [69]. In murine studies using aortic smooth muscle cells (mASMC), cAMP production (in response to TP agonists) seems to be IP-dependent, as the IP knockout (IP−/−) mASMC do not produce cAMP when stimulated with TPα agonists [69]. However, the mechanism by which the IP-TPα hetero-dimer couples to Gαs proteins is currently unknown.

Both the IP and TPα receptors are known to undergo agonist-dependent internalization and, furthermore, the receptor hetero-dimers undergo agonist-dependent endocytosis in response to agonists selective for either receptor [72]. Interestingly, the IP receptor demonstrates differential post-endocytotic fates (either degradation or recycling back to cell surface) dependent upon cell type, whereas the TPα receptor does not. Studies have shown that individually expressed IP in hASMCs undergoes degradation and is not recycled back to cell surface after agonist induction while, conversely, in HEK-293 cells, IP expression and responsiveness is restored after treatment with agonist, indicating receptor recycling back to the plasma membrane [72]. In comparison, the TPα receptor was shown to undergo agonist-induced degradation in both cell systems when expressed independently. Thus, by making use of the different individual fates of IP and TPα during internalization, it was shown that the fate of the hetero-dimer --- either degradation or recycling --- occurs as a singular unit, dependent upon which receptor agonist was bound. As a result, when IP-selective agonist was applied to the co-expressed receptors in HEK-293 cells, the internalized TPα followed the IP fate (i.e., was recycled back to plasma membrane), while treatment with TP-selective agonist caused the internalized IP to follow the TPα fate (i.e., degradation and loss of cell surface expression over time) [72]. These results suggest that the hetero-dimerized IP does not adopt an active conformation that is recognized by the endocytotic machinery when TP agonist is applied and, yet somehow, the TPα-IP hetero-dimer is coupling to Gαs proteins.

Perhaps the most interesting finding from IP-TPα hetero-dimer investigations is that such an interaction appears to form a binding site for the isoprostane, iPE2III [69]. iPE2III is an oxidative product of arachidonic acid (AA) that is known to activate the TPα, causing inositol phosphate (Ins-P) production. When iPE2III was applied to HEK cells transfected with both the IP and TPα receptors, there was an increase cAMP that did not occur in cells transfected with just the TPα or the IP alone [69]. Similarly, human and mouse ASMC treated with iPE2III showed increased cAMP production that was not seen using mASMC obtained from IP knockout (IP−/−) mice. In addition, treating the cells with the competitive TP inhibitor SQ 29548 did not reduce the amount of cAMP produced upon exposure to iPE2III, meaning that iPE2III does not make use of the known TPα binding site [69]. While the binding site for iPE2III is still unknown, this data suggests that it might occur within the TPα-IP hetero-dimer interface.

CONCLUSION

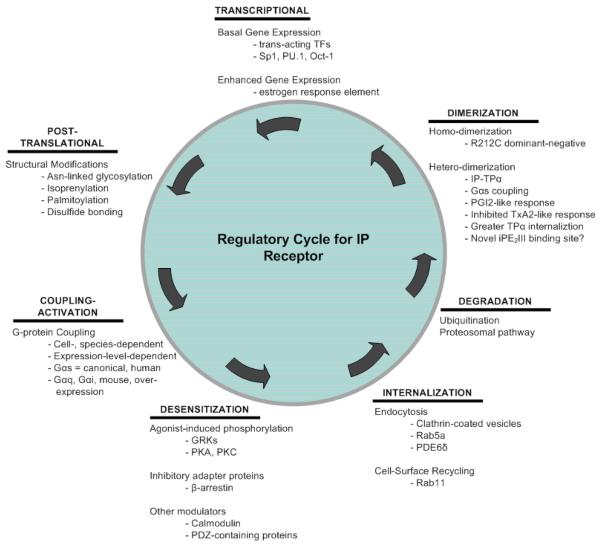

The prostacyclin receptor (IP) is an important cardiovascular GPCR that has been shown to play critical roles in vascular hemostasis and protection against atherothrombotic disease. The regulatory processes for the prostacyclin receptor involve a complex array of transcriptional machinery, in addition to multiple post-translational modifications, including N-linked glycosylation, isoprenylation, palmitoylation, and dimerization (Figure 4). Further regulation comes by way of cell-surface activation of the mature species, which necessitates phosphorylation, internalization, ubiquitination, and degradation. The various processes of IP receptor regulation, which span from transcription to cell-surface expression, are still being explored, and serve as potential therapeutic targets for various IP-related pathologies. As evidenced in this review, there have been great strides made in the elucidation of IP receptor regulation. However, many questions still remain unanswered. Further studies are required to determine the mechanism by which the first intracellular loop interacts with the Gαs protein to activate downstream effectors, as well as homo- and hetero-dimerization effects on G-protein-receptor interactions. The role of PDE6∂, which seems to be required in VSMC internalization, will need further exploration in other tissues, and is an important area of investigation, as it appears to be an important method of IP deactivation and internalization. Another interesting area of receptor regulation is IP-TPα hetero-dimerization, which provides several fascinating avenues to pursue, including: 1) the structural mechanism by which IP-TPα hetero-dimers activate the cAMP pathway (presumably by coupling to Gαs proteins) upon stimulation with TP agonists, 2) identification of the novel iPE2III binding pocket within the hetero-dimer and the molecular pathway by which it couples to G-protein, and 3) the effect of TPα activation on IP trafficking (and vice versa) in other physiological tissues such as platelets. Lastly, the initial studies of transcriptional regulation and the involvement of estrogen provide a means to explore potential gender-stratified differences in cardiovascular disease risk.

Figure 4. Regulatory cycle for human prostacyclin receptor.

Schematic showing major regulatory processes involved in prostacyclin receptor gene expression, protein function, and inactivation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and the American Heart Association (AHA).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- AA

Arachidonic acid or 5, 8, 11, 14-eicosatetraenoic acid

- AC

Adenylate cyclase

- ApoE

Apolipoprotein E

- ASMC

Aortic smooth muscle cell

- BRET

Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer

- cAMP

Cyclic-adenosine monophosphate

- CASMCs

Coronary artery smooth muscle cells

- CCVs

Clathrin-coated vesicles

- ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- COX

Cyclooxygenase

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- GRK

GPCR kinase

- GTP

Guanosine triphosphate

- Ins-P

Inositol phosphate

- IP receptor

Prostacyclin receptor

- iPE2III

isoprostaglandin E2 type-3

- LDL-R

Low-density lipoprotein receptor

- PDE6∂

Phosphodiesterase 6 delta subunit

- PGH2

Prostaglandin H2

- PGG2

Prostaglandin G2

- PGI2

Prostacyclin or prostaglandin I2

- PKA

cAMP-dependent protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PMA

Phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate

- TPα

Thromboxane receptor alpha

- TXA2

Thromboxane A2

- VSMC

Vascular smooth muscle cell

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2011 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010 Dec 15; doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Croce K, Libby P. Intertwining of thrombosis and inflammation in atherosclerosis. Current Opinion in Hematology. 2007 Jan 1;14(1):55–61. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200701000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Theilmeier G, Michiels C, Spaepen E, Vreys I, Collen D, Vermylen J, et al. Endothelial von Willebrand factor recruits platelets to atherosclerosis-prone sites in response to hypercholesterolemia. Blood. 2002 Jun 15;99(12):4486–93. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Massberg S, Brand K, Grüner S, Page S, Müller E, Müller I, et al. A critical role of platelet adhesion in the initiation of atherosclerotic lesion formation. J Exp Med. 2002 Oct 7;196(7):887–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Grosser T, Bonisch D, Zucker TP, Schror K. Iloprost-induced inhibition of proliferation of coronary artery smooth muscle cells is abolished by homologous desensitization. Agents Actions Suppl. 1995;45:85–91. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7346-8_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zucker TP, Bonisch D, Hasse A, Grosser T, Weber AA, Schror K. Tolerance development to antimitogenic actions of prostacyclin but not of prostaglandin E1 in coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998 Mar 19;345(2):213–20. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Blindt R, Bosserhoff AK, vom Dahl J, Hanrath P, Schror K, Hohlfeld T, et al. Activation of IP and EP(3) receptors alters cAMP-dependent cell migration. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002 May 24;444(1–2):31–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01607-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].O'Brien ER, Alpers CE, Stewart DK, Ferguson M, Tran N, Gordon D, et al. Proliferation in primary and restenotic coronary atherectomy tissue. Implications for antiproliferative therapy. Circ Res. 1993 Aug;73(2):223–31. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wilcox JN. Analysis of local gene expression in human atherosclerotic plaques. J Vasc Surg. 1992 May;15(5):913–6. doi: 10.1016/0741-5214(92)90747-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fetalvero KM, Shyu M, Nomikos AP, Chiu YF, Wagner RJ, Powell RJ, et al. The prostacyclin receptor induces human vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation via the protein kinase A pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006 Apr;290(4):H1337–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00936.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kasza Z, Fetalvero KM, Ding M, Wagner RJ, Acs K, Guzman AK, et al. Novel signaling pathways promote a paracrine wave of prostacyclin-induced vascular smooth muscle differentiation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009 May;46(5):682–94. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Arehart E, Stitham J, Asselbergs FW, Douville K, MacKenzie T, Fetalvero KM, et al. Acceleration of cardiovascular disease by a dysfunctional prostacyclin receptor mutation: potential implications for cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition. Circulation Research. 2008 Apr 25;102(8):986–93. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.165936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Egan KM, Lawson JA, Fries S, Koller B, Rader DJ, Smyth EM, et al. COX-2-derived prostacyclin confers atheroprotection on female mice. Science. 2004 Dec 10;306(5703):1954–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1103333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kobayashi T, Tahara Y, Matsumoto M, Iguchi M, Sano H, Murayama T, et al. Roles of thromboxane A(2) and prostacyclin in the development of atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004 Sep 1;114(6):784–94. doi: 10.1172/JCI21446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gryglewski RJ. Prostacyclin among prostanoids. Pharmacologcal Reports. 2008 Jan 1;60(1):3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Boie Y, Rushmore TH, Darmon-Goodwin A, Grygorczyk R, Slipetz DM, Metters KM, et al. Cloning and expression of a cDNA for the human prostanoid IP receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994 Apr 22;269(16):12173–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kobayashi T, Ushikubi F, Narumiya S. Amino acid residues conferring ligand binding properties of prostaglandin I and prostaglandin D receptors. Identification by site- directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(32):24294–303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002437200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Smyth EM, FitzGerald GA. Human prostacyclin receptor. Vitam Horm. 2002;65:149–65. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(02)65063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Stitham J, Stojanovic A, Merenick BL, O'Hara KA, Hwa J. The unique ligand-binding pocket for the human prostacyclin receptor. Site-directed mutagenesis and molecular modeling. J Biol Chem. 2003 Feb 7;278(6):4250–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207420200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Narumiya S, Sugimoto Y, Ushikubi F. Prostanoid receptors: structures, properties, and functions. Physiol Rev. 1999 Oct;79(4):1193–226. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Reid HM, Mulvaney EP, Turner EC, Kinsella BT. Interaction of the Human Prostacyclin Receptor with Rab11: CHARACTERIZATION OF A NOVEL Rab11 BINDING DOMAIN WITHIN -HELIX 8 THAT IS REGULATED BY PALMITOYLATION. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010 Jun 11;285(24):18709–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.106476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [22].Zhang Z, Austin SC, Smyth EM. Glycosylation of the human prostacyclin receptor: role in ligand binding and signal transduction. Mol Pharmacol. 2001 Sep 1;60(3):480–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Stitham J, Gleim SR, Douville K, Arehart E, Hwa J. Versatility and differential roles of cysteine residues in human prostacyclin receptor structure and function. J Biol Chem. 2006 Dec 1;281(48):37227–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hayes JS, Lawler OA, Walsh MT, Kinsella BT. The prostacyclin receptor is isoprenylated. Isoprenylation is required for efficient receptor-effector coupling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999 Aug 20;274(34):23707–18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Miggin SM, Lawler OA, Kinsella BT. Investigation of a functional requirement for isoprenylation by the human prostacyclin receptor. Eur J Biochem. 2002 Mar 1;269(6):1714–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2002.02817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Miggin SM, Lawler OA, Kinsella BT. Palmitoylation of the human prostacyclin receptor. Functional implications of palmitoylation and isoprenylation. J Biol Chem. 2003 Feb 28;278(9):6947–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210637200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Turner EC, Kinsella BT. Transcriptional regulation of the human prostacyclin receptor gene is dependent on Sp1, PU.1 and Oct-1 in megakaryocytes and endothelial cells. J Mol Biol. 2009 Feb 27;386(3):579–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Turner EC, Kinsella BT. Estrogen increases expression of the human prostacyclin receptor within the vasculature through an ERalpha-dependent mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2010 Feb 26;396(3):473–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. Mammalian G proteins and their cell type specific functions. Physiol Rev. 2005 Oct;85(4):1159–204. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Siehler S. Regulation of RhoGEF proteins by G12/13-coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2009 Sep;158(1):41–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Miggin SM, Kinsella BT. Investigation of the mechanisms of G protein: effector coupling by the human and mouse prostacyclin receptors. Identification of critical species-dependent differences. J Biol Chem. 2002 Jul 26;277(30):27053–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Smyth EM, Nestor PV, FitzGerald GA. Agonist-dependent phosphorylation of an epitope-tagged human prostacyclin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1996 Dec 27;271(52):33698–704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Smyth EM, Li WH, FitzGerald GA. Phosphorylation of the prostacyclin receptor during homologous desensitization. A critical role for protein kinase c. J Biol Chem. 1998 Sep 4;273(36):23258–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kam Y, Chow KB, Wise H. Factors affecting prostacyclin receptor agonist efficacy in different cell types. Cell Signal. 2001 Nov;13(11):841–7. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Vassaux G, Gaillard D, Ailhaud G, Negrel R. Prostacyclin is a specific effector of adipose cell differentiation. Its dual role as a cAMP- and Ca(2+)-elevating agent. J Biol Chem. 1992 Jun 5;267(16):11092–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Parfenova H, Zuckerman S, Leffler CW. Inhibitory effect of indomethacin on prostacyclin receptor-mediated cerebral vascular responses. Am J Physiol. 1995 May;268(5 Pt 2):H1884–90. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.5.H1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Nishimura T, Yamamoto T, Komuro Y, Hara Y. Antiplatelet functions of a stable prostacyclin analog, SM-10906 are exerted by its inhibitory effect on inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate production and cytosolic Ca++ increase in rat platelets stimulated by thrombin. Thromb Res. 1995 Aug 1;79(3):307–17. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(95)00117-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zhang L, Bastepe M, Jüppner H, Ruan K-H. Characterization of the molecular mechanisms of the coupling between intracellular loops of prostacyclin receptor with the C-terminal domain of the Galphas protein in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2006 Oct 1;454(1):80–8. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhang L, Huang G, Wu J, Ruan KH. A profile of the residues in the first intracellular loop critical for Gs-mediated signaling of human prostacyclin receptor characterized by an integrative approach of NMR-experiment and mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 2005 Aug 30;44(34):11389–401. doi: 10.1021/bi050483p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Zhang L, Wu J, Ruan K-H. Solution structure of the first intracellular loop of prostacyclin receptor and implication of its interaction with the C-terminal segment of G alpha s protein. Biochemistry. 2006 Feb 14;45(6):1734–44. doi: 10.1021/bi0515669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Scheerer P, Park JH, Hildebrand PW, Kim YJ, Krauss N, Choe HW, et al. Crystal structure of opsin in its G-protein-interacting conformation. Nature. 2008 Sep 25;455(7212):497–502. doi: 10.1038/nature07330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Choe HW, Kim YJ, Park JH, Morizumi T, Pai EF, Krauss N, et al. Crystal structure of metarhodopsin II. Nature. 2011 Mar 31;471(7340):651–5. doi: 10.1038/nature09789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kelly E, Bailey CP, Henderson G. Agonist-selective mechanisms of GPCR desensitization. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2008 Mar 3;153:S379–S88. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ferguson SSG. Phosphorylation-independent attenuation of GPCR signalling. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2007 Apr 1;28(4):173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Smyth EM, Li WH, FitzGerald GA. Phosphorylation of the prostacyclin receptor during homologous desensitization. A critical role for protein kinase C. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998 Sep 4;273(36):23258–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Nilius SM, Hasse A, Kuger P, Schrör K, Meyer-Kirchrath J. Agonist-induced long-term desensitization of the human prostacyclin receptor. FEBS Letters. 2000 Nov 10;484(3):211–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Fisch A, Tobusch K, Veit K, Meyer J, Darius H. Prostacyclin receptor desensitization is a reversible phenomenon in human platelets. Circulation. 1997 Aug 5;96(3):756–60. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.3.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Jaschonek K, Faul C, Schmidt H, Renn W. Desensitization of platelets to iloprost. Loss of specific binding sites and heterologous desensitization of adenylate cyclase. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1988 Mar 1;147(2):187–96. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90777-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Nishimura T, Yamamoto T, Komuro Y, Hara Y. Antiplatelet functions of a stable prostacyclin analog, SM-10906 are exerted by its inhibitory effect on inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate production and cytosolic Ca++ increase in rat platelets stimulated by thrombin. Thrombosis Research. 1995 Aug 1;79(3):307–17. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(95)00117-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Harper MT, Poole AW. Diverse functions of protein kinase C isoforms in platelet activation and thrombus formation. J Thromb Haemost. 2010 Mar;8(3):454–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ashby B. Novel mechanism of heterologous desensitization of adenylate cyclase: prostaglandins bind with different affinities to both stimulatory and inhibitory receptors on platelets. Molecular Pharmacology. 1990 Jul 1;38(1):46–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. The role of beta-arrestins in the termination and transduction of G-protein-coupled receptor signals. Journal of Cell Science. 2002 Feb 1;115(Pt 3):455–65. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. Multifaceted roles of beta-arrestins in the regulation of seven-membrane-spanning receptor trafficking and signalling. Biochemical Journal. 2003 Nov 1;375(Pt 3):503–15. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Smyth EM, Austin SC, Reilly MP, FitzGerald GA. Internalization and sequestration of the human prostacyclin receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000 Oct 13;275(41):32037–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Seachrist JL, Ferguson SSG. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis and trafficking by Rab GTPases. Life Sci. 2003 Dec 5;74(2–3):225–35. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].O'Keeffe MB, Reid HM, Kinsella BT. Agonist-dependent internalization and trafficking of the human prostacyclin receptor: a direct role for Rab5a GTPase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008 Oct 1;1783(10):1914–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Wikström K, Reid HM, Hill M, English KA, O'Keeffe MB, Kimbembe CC, et al. Recycling of the human prostacyclin receptor is regulated through a direct interaction with Rab11a GTPase. Cell Signal. 2008 Dec 1;20(12):2332–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Nancy V, Callebaut I, El Marjou A, de Gunzburg J. The delta subunit of retinal rod cGMP phosphodiesterase regulates the membrane association of Ras and Rap GTPases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002 Apr 26;277(17):15076–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wilson SJ, Smyth EM. Internalization and recycling of the human prostacyclin receptor is modulated through its isoprenylation-dependent interaction with the delta subunit of cGMP phosphodiesterase 6. J Biol Chem. 2006 Apr 28;281(17):11780–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Giovanazzi S, Accomazzo MR, Letari O, Oliva D, Nicosia S. Internalization and down-regulation of the prostacyclin receptor in human platelets. Biochemical Journal. 1997 Jul 1;325(Pt 1):71–7. doi: 10.1042/bj3250071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Donnellan PD, Kinsella BT. Immature and mature species of the human Prostacyclin Receptor are ubiquitinated and targeted to the 26S proteasomal or lysosomal degradation pathways, respectively. J Mol Signal. 2009;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Marchese A, Raiborg C, Santini F, Keen JH, Stenmark H, Benovic JL. The E3 ubiquitin ligase AIP4 mediates ubiquitination and sorting of the G protein-coupled receptor CXCR4. Dev Cell. 2003 Nov;5(5):709–22. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00321-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Cottrell GS, Padilla B, Pikios S, Roosterman D, Steinhoff M, Gehringer D, et al. Ubiquitin-dependent down-regulation of the neurokinin-1 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006 Sep 22;281(38):27773–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Martin NP, Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. Regulation of V2 vasopressin receptor degradation by agonist-promoted ubiquitination. J Biol Chem. 2003 Nov 14;278(46):45954–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Milligan G. G protein-coupled receptor dimerization: function and ligand pharmacology. Mol Pharmacol. 2004 Jul;66(1):1–7. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.000497.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Lohse MJ. Dimerization in GPCR mobility and signaling. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010 Feb;10(1):53–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Giguere V, Gallant MA, de Brum-Fernandes AJ, Parent JL. Role of extracellular cysteine residues in dimerization/oligomerization of the human prostacyclin receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004 Jun 21;494(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Ibrahim S, Tetruashvily M, Frey AJ, Wilson SJ, Stitham J, Hwa J, et al. Dominant negative actions of human prostacyclin receptor variant through dimerization: implications for cardiovascular disease. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2010 Sep 1;30(9):1802–9. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.208900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Wilson SJ, Roche AM, Kostetskaia E, Smyth EM. Dimerization of the human receptors for prostacyclin and thromboxane facilitates thromboxane receptor-mediated cAMP generation. J Biol Chem. 2004 Dec 17;279(51):53036–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Shen RF, Tai HH. Thromboxanes: synthase and receptors. J Biomed Sci. 1998;5(3):153–72. doi: 10.1007/BF02253465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Kinsella BT, O'Mahony DJ, Fitzgerald GA. The human thromboxane A2 receptor alpha isoform (TP alpha) functionally couples to the G proteins Gq and G11 in vivo and is activated by the isoprostane 8-epi prostaglandin F2 alpha. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997 May;281(2):957–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Wilson SJ, Dowling JK, Zhao L, Carnish E, Smyth EM. Regulation of thromboxane receptor trafficking through the prostacyclin receptor in vascular smooth muscle cells: role of receptor heterodimerization. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2007 Feb 1;27(2):290–6. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000252667.53790.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]