Abstract

Background

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease that may be associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events, including cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

Methods and Results

We searched the MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register databases for relevant studies in English between January 1, 1980, and January 1, 2012. Extraction was by 3 independent reviewers. Summary incidence, risk ratios (RRs), and confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using fixed‐effects and random‐effects modeling. Meta‐regression was also performed to identify sources of between‐study variation. Nine studies were included, representing a total of 201 239 patients with mild and 17 415 patients with severe psoriasis. The level of covariate adjustment varied among studies, leading to the possibility of residual confounding. Using the available adjusted effect sizes, mild psoriasis remained associated with a significantly increased risk of myocardial infarction (RR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.63) and stroke (RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.16). Severe psoriasis was associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular mortality (RR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.74), myocardial infarction (RR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.32 to 2.18), and stroke (RR, 1.56 95% CI, 1.32 to 1.84). Based on these risk ratios and the background population event rates, psoriasis is associated with an estimated excess of 11 500 (95% CI, 1169 to 24 407) major adverse cardiovascular events each year.

Conclusions

Mild and severe psoriasis are associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke. Severe psoriasis is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality. Future studies should include more complete covariate adjustment and characterization of psoriasis severity.

Keywords: cardiovascular diseases, epidemiology, meta‐analysis, myocardial infarction, psoriasis

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the skin and joints that affects 2% to 3% of the world's population.1–2 Recent research has emphasized that psoriasis is a systemic disease with multiple associated comorbidities.3 For example, patients with psoriasis also have an increased prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidemia.4–7 These findings have led to the recommendation that all patients with psoriasis should undergo detailed screening and management of cardiovascular risk factors.8

Patients with psoriasis may also have an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) beyond that attributable to measured cardiovascular risk factors.9 In support of this theory, large epidemiologic studies have found increased rates of cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke among patients with both mild and severe psoriasis.10–12 Shared inflammatory pathways, including TH1‐mediated inflammation, alterations in angiogenesis, and endothelial dysfunction, may link the pathogenesis of psoriasis with the development of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.13–14 However, the magnitude of this association remains controversial, and it is uncertain whether the increased risk for MACE is limited only to patients with severe psoriasis.

To answer these questions, we performed a systematic review and meta‐analysis of the association between psoriasis and cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke. We stratified our analysis by mild versus severe psoriasis and included adjusted risk estimates accounting for comorbidities. Based on these results, we also estimated the attributable risk of psoriasis to excess major adverse cardiovascular events in the US population.

Methods

Selection of Studies

We systematically searched the MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register databases with the following search terms: “Psoriasis”[Mesh] AND {(“Death, Sudden, Cardiac”[Mesh]) OR (“Myocardial Infarction”[Mesh]) OR (“Stroke”[Mesh]) OR (“Cardiovascular Diseases”[Mesh])}. Our search was limited to English‐language and human‐only studies published between January 1, 1980, and January 1, 2012. The search yielded 558 results. All abstracts were read to determine eligibility for inclusion in the systematic review. To be included, original studies needed to fulfill the following inclusion criteria: case–control, cross‐sectional, cohort, or nested case–control design; evaluation of MI, stroke, cardiovascular death, or composite cardiovascular end point in conjunction with psoriasis; and analyses that compared psoriasis patients with control groups. The studies had to evaluate the incidence of subsequent cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke, with these 3 entities defined as overall MACE. The end point could be identified by physical examination, patient self‐report, medical chart review, or medical billing codes. A number of studies assessed MI or stroke prevalence but not incidence. These studies are detailed in Tables S1 and S2 but were not included in the analysis because they did not assess incidence.

Data Extraction and Clinical Endpoints

The Meta‐Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines were used to guide analysis.15 The systematic review and data extraction were performed independently by 3 reviewers (E.J.A., C.T.H., and A.W.A.), and any differences were adjudicated by consensus. For each study included, we recorded the study year, country in which the study population lived, setting in which the study took place, study design, numbers of case and control subjects, age, sex, statistical adjustments for comorbidities, data collection processes (prospective versus retrospective), whether the results were a primary or secondary analysis of the publication, and whether psoriasis disease severity was assessed. A previously validated 6‐point scale was used to determine study quality, with values of 0 or 1 assigned to study design, assessment of exposure (psoriasis), assessment of outcome (major adverse cardiovascular events), control for confounding, evidence of bias, and assessment of psoriasis severity. Studies with a score of 0 to 3 were categorized as lower quality, whereas studies with scores of 4 to 6 were categorized as higher quality.16 Most of the included studies were of either case–control or cohort design. One study assessed the combined outcome of MACE.9 All others assessed MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death independently.

Statistical Analysis

Because prior studies have suggested a significant effect modification of psoriasis severity on cardiovascular outcomes, we stratified our analysis on the basis of patients with mild psoriasis versus patients with severe psoriasis. To estimate the pooled risk ratio (RR), the adjusted effect size and reported upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence interval for each study were log‐transformed. The inverse variance method was then applied with fixed‐effects and random‐effects models of DerSimonian and Laird.17 Study heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic.

Risk ratios were used to calculate the excess risk for cardiovascular mortality, MI, and stroke among patients with psoriasis. Because 2 studies used standardized mortality ratios based on a population sample, we assumed that the control groups in each case consisted of an equal number of patients matched by age and sex with the same duration of follow‐up as the psoriasis group.18–19 In cases in which the total number of patient‐years of follow‐up was not reported, we integrated the mean of the aggregate data.18 In another study, the total patient‐years of follow‐up were available, but the total number of events was not reported.20 We therefore estimated the number of events on the basis of the size of the cohort and the reported events/1000 patient‐years.

Publication bias was assessed using visual inspection of a funnel plot of study size versus standard error, with formal statistical testing using the Begg adjusted rank correlation test.21–22 To explore sources of study heterogeneity, we performed meta‐regression using prespecified variables and fixed‐effects meta‐analysis. Prespecified sources of heterogeneity included study country, subject location (ambulatory or inpatient), multivariate adjustment for confounders, prospective versus retrospective study design, primary versus secondary analysis, ascertainment of psoriasis disease severity, measure of outcome, and study quality (0 to 3 versus 4 to 6).

To calculate the population attributable risk of psoriasis on major adverse cardiovascular events, we used the most current statistics from the American Heart Association,23 which are based on 2008 US census data.24 We assumed that a total of 7.5 million people in the United States have psoriasis, and that 10% of patients with psoriasis have severe psoriasis.25

All analyses were performed using STATA Version 11.2 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX). All statistical tests were 2 sided, with a significance level of <0.05.

Results

Study Selection

From the initial 558 search results, 108 full‐text articles were chosen for further review. Among these full‐text articles, 26 studies were excluded because they were reviews; 20 were letters, commentaries, or case reports; 12 exclusively assessed psoriatic arthritis (PsA) patients; 15 assessed cardiovascular risk factors only; 13 did not measure the association between psoriasis and MACE; 6 were of the same cohort as prior studies; and 7 assessed prevalence of MI or stroke but not incidence (Tables S1 and S2).26–32 Nine studies were therefore included in the meta‐analysis (Figure 1).11–12,11–20,11–36 Studies with significant cohort overlap (eg, in which multiple studies used the General Practice Research Database [GPRD] in overlapping periods) were included only once.9–10,9–39 In each case, the study with the highest‐quality measure and most complete reporting was included.

Figure 1.

Article selection. CV indicates cardiovascular; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events.

The baseline characteristics of each study, stratified by mild versus severe psoriasis, are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Two studies used standardized mortality ratios based on the expected mortality among patients matched for age and sex,18–19,37 whereas other studies used hazard ratios or rate ratios. Study designs included nested case–control, isolated cohorts based on practice patterns, or whole‐country cohort design. All studies except 1 differentiated mild from severe psoriasis, as defined by either inpatient status, need for phototherapy, or use of systemic medications.34

Table 1.

Mild Psoriasis and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events

| Reference | Study Country | Number of Patients | Mean Age, Years | Events | Event Rate, Control | Event Rate, Psoriasis | Mean Follow‐Up Time, Years | Effect Measure | Definition of Outcomes | Adjusted Effect Size | Adjustment Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular mortality | |||||||||||

| Mallbris et al18 | Sweden | 19 757 | NR | 1302 | 6.1 | 5.7 | 11.6 | SMR | Death registry; ICD‐7, ICD‐8, and ICD‐9 codes | 0.94 (0.89 to 0.99) | A, G |

| Ahlehoff et al20 | Denmark | 34 371 | 47.2 | 393 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 5.0 | RR | Cardiovascular death using ICD‐10 code | 1.14 (1.06 to 1.22) | A, G, M |

| Myocardial infarction | |||||||||||

| Gelfand et al11 | United Kingdom | 127 129 | 46.4 | 2319 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 3.8 | HR | Diagnostic code using READ or OXMIS | 1.54 (1.24 to 1.91) | H, D, C, A, G, S, MI, BMI |

| Wakkee et al34* | Netherlands | 15 820 | 48.9 | 223 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 6.0 | HR | Hospitalization for MI | 0.94 (0.8 to 1.11) | H, D, C, A, G, U |

| Ahlehoff et al20 | Denmark | 34 371 | 47.2 | 494 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 5.0 | RR | MI using ICD‐10 code | 1.22 (1.12 to 1.33) | A, G, M |

| Lin et al35 | Taiwan | 4162 | NR | 17 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 5.0 | HR | New MI, using insurance database | 2.10 (1.27 to 3.43) | H, D, C, A, G, SD |

| Stroke | |||||||||||

| Gelfand et al12 | United Kingdom | 129 143 | 45.1 | 2100 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.7 | HR | Diagnostic code using Read or OXMIS | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.11) | A, G, H, D, C, S, N |

| Ahlehoff et al36 | Denmark | 36 765 | 46.1 | 838 | 3.1 | 4.5 | 5.0 | RR | Ischemic stroke using ICD‐9 codes | 1.25 (1.17 to 1.34) | A, G, SD, M |

Event rates are reported as events/1000 person‐years. NR indicates not reported; SMR, standardized mortality ratio; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; RR, risk ratio; HR, hazard ratio; A, age; G, gender; M, medical comorbidities (individual comorbidities not reported); OXMIS, Oxford Medical Information System; H, hypertension; D, diabetes; C, cholesterol; S, smoking; U, healthcare utilization; N, neurovascular disease; MI, prior myocardial infarction; BMI, body mass index; SD, social demographics.

Authors did not distinguish mild from severe psoriasis.

Table 2.

Severe Psoriasis and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events

| Reference | Study Country | Number of Patients | Mean Age, Years | Events | Event Rate, Control | Event Rate, Psoriasis | Mean Follow‐Up Time, Years | Effect Measure | Definition of Outcomes | Adjusted Effect Size | Adjustment Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular mortality | |||||||||||

| Mallbris et al18 | Sweden | 8991 | NR | 1529 | 10.6 | 16.2 | 10.5 | SMR | Death registry; ICD‐7, ICD‐8, and ICD‐9 codes | 1.52 (1.44 to 1.60) | A, G |

| Abuabara et al33 | United Kingdom | 3603 | 52.2 | 108 | 6.2 | 8.7 | 2.7 | HR | Diagnostic code using READ or OXMIS | 1.57 (1.26 to 1.96) | A, G |

| Ahlehoff et al20 | Denmark | 2621 | 46.9 | 41 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 5.0 | RR | Cardiovascular death using ICD‐10 code | 1.57 (1.27 to 1.94) | A, G, M |

| Stern et al19 | USA | 1376 | 46 | 246 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 22.4 | SMR | Telephone interviews and national death index | 1.02 (0.90 to 1.16) | A, G |

| Myocardial infarction | |||||||||||

| Gelfand et al11 | United Kingdom | 3837 | 49.8 | 112 | 3.6 | 5.1 | 5.4 | HR | Diagnostic code using READ or OXMIS | 7.08 (3.06 to 16.36) | H, D, C, A, G, S, MI, BMI |

| Ahlehoff et al20 | Denmark | 2621 | 46.9 | 45 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 5.0 | RR | MI using ICD‐10 code | 1.45 (1.10 to 1.90) | A, G, M |

| Lin et al35 | Taiwan | 590 | NR | 5 | 0.4 | 1.7 | 5.5 | HR | New MI, using insurance database | 1.81 (0.69 to 4.74) | H, D, C, A, G, SD |

| Stroke | |||||||||||

| Gelfand, 200912 | United Kingdom | 3603 | 52.2 | 74 | 4.4 | 6.1 | 2.7 | HR | Diagnostic code using READ or OXMIS | 1.43 (1.10 to 1.87) | A, G, H, D, C, S, N |

| Ahlehoff et al36 | Denmark | 2793 | 46.0 | 90 | 3.1 | 6.8 | 4.7 | RR | Ischemic stroke using ICD‐9 codes | 1.65 (1.33 to 2.05) | A, G, SD, M |

NR indicates not reported; SMR, standardized mortality ratio; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; RR, risk ratio; HR, hazard ratio; A, age; G, gender; M, medical comorbidities (individual comorbidities not reported); H, hypertension; D, diabetes; C, cholesterol; S, smoking; U, healthcare utilization; MI, prior myocardial infarction; BMI, body mass index; SD, social demographics; N, neurovascular disease, including prior stroke or transient ischemic attack.

Quality of the Studies and Publication Bias

All studies were observational and included sufficient follow‐up to determine the end point of interest. All studies were deemed high quality (score of 4 or greater) using a prespecified 6‐point quality scale. Variable levels of covariate adjustment were performed (Tables 1 and 2), with all studies adjusting for age and sex, but only some studies including full adjustment for other medical comorbidities. The studies of cardiovascular mortality adjusted only for age, sex, and some medical comorbidities, whereas studies of myocardial infarction and stroke in general included more complete covariate adjustment. No evidence of publication bias was detected for cardiovascular mortality (P=0.7), MI (P=0.5), or stroke (P=0.9) using visual inspection of a funnel plot and formal testing with the Egger test.

Because observational studies may also have significant between‐study heterogeneity in design and cohort selection, we also performed meta‐regression analysis for the end points of cardiovascular mortality and MI (CV death in mild psoriasis and stroke were not included in meta‐regression testing because of identification of only 2 studies for each of these analysis subgroups and no significant between‐study heterogeneity). There was an association between study country and the strength of association of severe psoriasis with cardiovascular mortality (P=0.01), largely because the 1 US‐based study of cardiovascular mortality had a smaller reported RR than the other, European‐based studies.19 All other prespecified meta‐regression analyses were not statistically significant (Tables S3 through S5).

Cardiovascular Mortality

Cardiovascular mortality was studied among 4 cohorts, including patients from the United States, United Kingdom, Sweden, and Denmark (Figure 2). A total of 54 128 patients with mild psoriasis were studied. Only 2 studies addressed cardiovascular mortality among patients with mild psoriasis. The 2 studies had discordant findings, leading to no statistically significant association (RR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.86 to 1.25) on meta‐analysis.

Figure 2.

Cardiovascular death among patients with psoriasis. A, Risk of cardiovascular death among patients with mild psoriasis. B, Risk of cardiovascular death among patients with severe psoriasis. Rates are reported as events/1000 person‐years.

Among 16 591 patients with severe psoriasis, there was a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular mortality during long‐term follow‐up ranging from 2.7 to 22.4 years (RR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.74). Discordant outcomes between the European‐based and US‐based studies accounted for all the between‐study heterogeneity (I2=91.1% before exclusion, I2=0 after exclusion). If the meta‐analysis was restricted to the 3 European‐based studies, the RR for cardiovascular mortality among patients with severe psoriasis increased to 1.53 (95% CI, 1.45 to 1.60). The incidence rate per 1000 person‐years for cardiovascular mortality among patients with severe psoriasis ranged from 3.1 to 16.2 (Table 2).

Myocardial Infarction

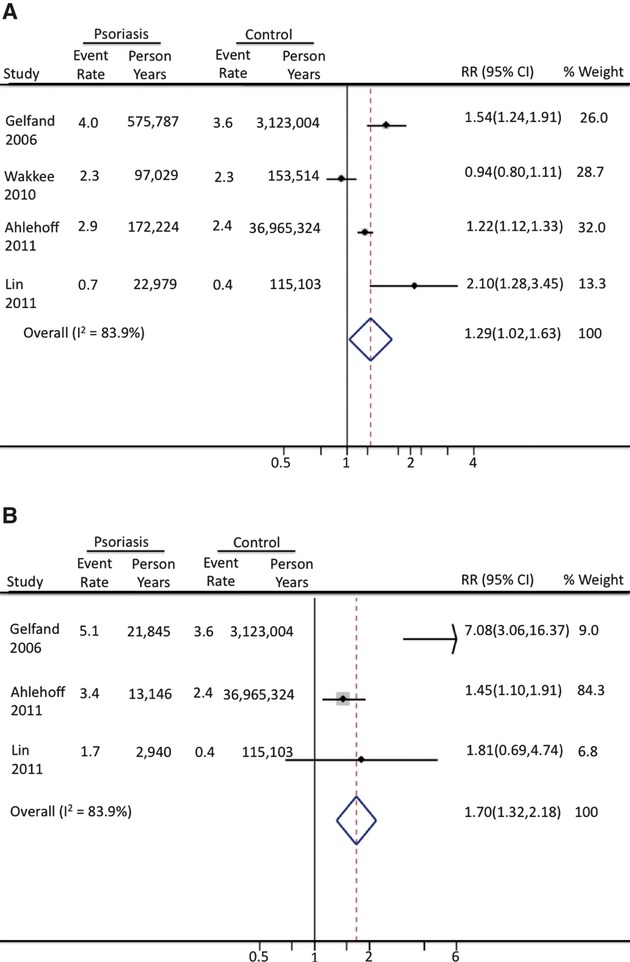

Myocardial infarction was studied among 4 cohorts (Figure 3). There was a significantly increased risk of MI among patients with both mild and severe psoriasis. Among the 181 492 patients with mild psoriasis, the RR of MI was 1.29 (95% CI, 1.02 to 1.63). For the 7048 patients with severe psoriasis, the RR of MI was 1.70 (95% CI, 1.32 to 2.18). In 1 study, patients with severe psoriasis were identified only by use of TNF‐alpha inhibitors.35 Excluding this study from the meta‐analysis did not significantly affect the outcomes (RR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.30 to 2.19 for severe psoriasis). These studies were based on a total number of 3053 MI events among patients with mild psoriasis and of 162 MI events among patients with severe psoriasis. The incidence rate per 1000 person‐years for MI among patients with psoriasis ranged from 1.7 in a study conducted in Taiwan to 4.0 in a study conducted in the United Kingdom.11,35

Figure 3.

Myocardial infarction among patients with psoriasis. A, Risk of myocardial infarction among patients with mild psoriasis. B, Risk of myocardial infarction among patients with severe psoriasis. Rates are reported as events/1000 person‐years.

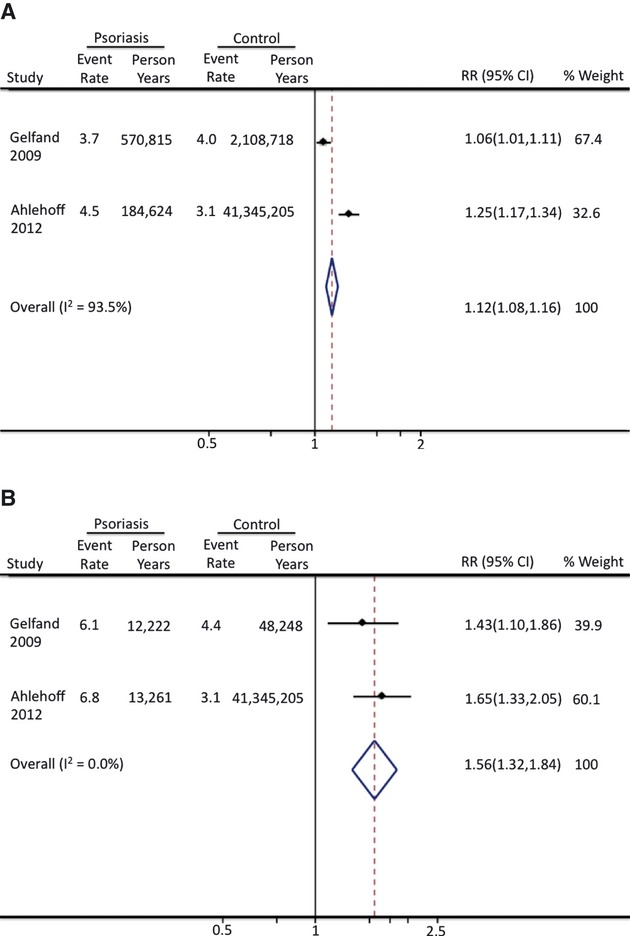

Stroke

Two studies assessed the risk of incident stroke among patients with psoriasis (Figure 4). Among 165 908 patients with mild psoriasis, the RR for stroke was 1.12 (95% CI, 1.08 to 1.16). Among 6396 patients with severe psoriasis, the RR for stroke was 1.56 (95% CI, 1.32 to 1.84). Both these studies were derived from large European‐based cohorts and use of medical codes. In 1 study, patients with psoriasis were identified on the basis of medical prescriptions, and the analysis only included treated patients.36 The incidence rate per 1000 person‐years for stroke ranged from 3.7 to 5.0 for patients with mild psoriasis and from 6.1 to 6.8 for patients with severe psoriasis.

Figure 4.

Stroke among patients with psoriasis. A, Risk of stroke among patients with mild psoriasis. B, Risk of stroke among patients with severe psoriasis. Rates are reported as events/1000 person‐years.

Attributable Risk Estimate of Psoriasis

Using the most current background rates of cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in the US population, we calculated the population attributable risk of psoriasis on major adverse cardiovascular events (Table 3). On the basis of these estimates and pooling results from patients with mild and severe psoriasis, psoriasis in the United States is associated with an estimated 1269 (95% CI, −2208 to 5741) excess deaths from cardiovascular causes, 6479 (95% CI, 979 to 13 409) excess MIs, and 3782 (95% CI, 2399 to 5258) excess strokes each year, for an estimated total of >11 500 (95% CI, 1169 to 24 407) excess major adverse cardiovascular events each year.

Table 3.

Population Attributable Risk of Psoriasis on Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events

| Baseline Rate Per 100 000/Year | Rate Ratio, Psoriasis (95% CI) | Rate Per 100 000/Year, Psoriasis | Excess Rate Per 100 000/Year, Psoriasis | Number of Excess Cases/Year Attributable to Psoriasis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild psoriasis | |||||

| CV death | 256 | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.25) | 263.7 (220 to 320) | 7.7 (−36 to 64) | 520 (−2419 to 4320) |

| MI | 261 | 1.29 (1.02 to 1.63) | 336.7 (266 to 425) | 75.7 (5 to 164) | 5109 (352 to 11 099) |

| Stroke | 307.5 | 1.12 (1.08 to 1.16) | 344.4 (332 to 356) | 36.9 (25 to 49) | 2491 (1661 to 3321) |

| Severe psoriasis | |||||

| CV death | 256 | 1.39 (1.11 to 1.74) | 355.8 (284 to 445) | 99.8 (28 to 189) | 749 (211 to 1421) |

| MI | 261 | 1.70 (1.32 to 2.18) | 443.7 (345 to 569) | 182.7 (84 to 308) | 1370 (626 to 2310) |

| Stroke | 307.5 | 1.56 (1.32 to 1.84) | 479.7 (406 to 566) | 172.2 (98 to 258) | 1292 (738 to 1937) |

Estimates are based on 2008 US census data and current national rates of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke. The 95% CI estimates for the rate ratio are based on meta‐analysis results. CV indicates cardiovascular; MI, myocardial infarction.

Discussion

The association between psoriasis and cardiovascular disease has gained increased attention in the past 5 years. Although psoriasis was once thought to be a disease limited to the skin, there is increasing awareness that patients with psoriasis have a number of associated medical comorbidities. These comorbidities may significantly affect quality of life and also place patients with psoriasis at higher risk of subsequent medical problems. Although many of the initial studies examining psoriasis and comorbidities assessed only the prevalence of risk factors, a number of recent cohort studies have assessed incident cardiovascular events among patients with psoriasis. In this meta‐analysis, we systematically assessed the incidence of MACE among patients with psoriasis to better understand the magnitude of this association and the additional contribution of psoriasis to cardiovascular disease.

In our analysis, we found that both mild and severe psoriasis were associated with significantly increased risk of MI and stroke. In addition, severe psoriasis was associated with significantly increased cardiovascular mortality. The strength of the association for MI and stroke was greater for severe than for mild psoriasis, further supporting a possible dose–response relationship between disease severity and the excess risk of cardiovascular disease. On the basis of the pooled risk ratios for mild and severe psoriasis, we estimated that psoriasis accounts for an additional approximately 11 000 major adverse cardiovascular events/year in the United States. Although the relative risk of MACE is greater for patients with severe compared with mild psoriasis, the greater population prevalence of mild psoriasis actually translates into a greater population attributable risk of mild psoriasis for both MI and stroke. These findings emphasize that all patients with psoriasis, rather than only those with severe psoriasis, should be educated regarding an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Prior studies have suggested an age interaction between psoriasis and cardiovascular risk, with younger patients having a significantly higher relative risk for cardiovascular disease than older patients.11 These risk estimates may reflect the bimodal incidence of psoriasis, with a differential effect of early‐onset psoriasis on progression of atherosclerosis. Alternatively, the development of additional cardiovascular risk factors coincident with aging may eventually outweigh the additional risk of psoriasis to cardiovascular disease. However, we recently found that even among older patient cohorts, patients with psoriasis undergoing coronary angiography were more likely to have coronary artery disease.40 Although we could not adjust in this meta‐analysis for an age‐dependent effect of psoriasis on cardiovascular outcomes, these findings should be widely applicable to the cohorts studied, in which the mean age ranged from 45 to 52 years of age. This age group represents a common age at which intervention into cardiovascular risk factors can substantially modify future cardiovascular risk.

Currently, no specific treatments exist for modification of cardiovascular risk independent of standard risk factors. In the absence of specific treatments, recognition of modifiable risk factors remains paramount. Recent survey results suggest that most physicians are not aware of the association between psoriasis and cardiovascular disease and that patients with psoriasis are not adequately screened for medical comorbidities.41–42 Once these modifiable conditions are recognized, aggressive lifestyle modification and medical intervention may be warranted. Recognizing the additional contribution of psoriasis to cardiovascular disease may also result in reclassification of a number of patients from low‐ or medium risk based on Framingham risk scores to a higher‐risk category.43

It is possible that treatment of psoriasis with systemic medications may independently affect cardiovascular outcomes. Methotrexate, which is commonly prescribed in cases of moderate to severe psoriasis, may reduce the risk of cardiovascular events, although most of this evidence is observational and based on patients with rheumatoid arthritis.44 TNF‐alpha inhibitors are increasingly used in the management of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Randomized trials with short duration of follow‐up showed no effect of TNF‐alpha inhibitors on cardiovascular events.45 Recently published observational data suggests that TNF‐alpha inhibitors may be associated with reduced incidence of cardiovascular events among patients with psoriasis.46 In addition, treatment of psoriasis with TNF‐alpha inhibitors may reduce the incidence of diabetes, thereby reducing long‐term cardiovascular risk.47 Although there is some concern that more recent IL 12/23 inhibitors may increase cardiovascular mortality, a recent meta‐analysis failed to find any association between these agents and cardiovascular events.45 Further research will be necessary to better delineate the effect of these systemic medications on cardiovascular events.

This study should be interpreted in the context of its design. First, observational studies have inherent limitations, including unmeasured confounders and between‐study heterogeneity. The included studies, however, were all high quality and included effect sizes that were adjusted. Second, a potential major limitation of this analysis is the extent of covariate adjustment performed in each primary study. For example, studies of cardiovascular mortality did not adjust for important covariates, including smoking and diabetes, both of which are known to occur with greater prevalence among patients with psoriasis. It is therefore possible that the apparent independent effect of psoriasis on cardiovascular mortality is partly attributable to incomplete covariate adjustment. The studies of myocardial infarction and stroke utsed more complete covariate adjustment including smoking and diabetes status, but not all these studies adjusted for body mass index, and patients with psoriasis are known to have a higher prevalence of obesity when compared with the general population. These analyses emphasize that future epidemiologic studies should include a more thorough assessment of cardiovascular risk factors among well‐defined cohorts of patients with psoriasis. Third, the majority of the studies used billing codes and/or medication prescriptions to identify patients with psoriasis. The study population therefore represents patients with treated psoriasis and may not reflect the entire, often undertreated population of patients with psoriasis. Furthermore, the definition of severe psoriasis varied between studies. Most cohorts identified only 3% to 10% of patients as having severe psoriasis, whereas recent estimates based on percent body surface area involvement suggest that 15% to 20% of patients with psoriasis have a moderate to severe form of the disease.25 Whether such patients have an intermediate risk profile between that of patients with mild versus severe psoriasis is uncertain. Fourth, the studied cohorts range over the last 1 to 3 decades. A number of new therapies have been developed for psoriasis in the past decade, and it is possible that these therapies have altered the current epidemiology of cardiovascular disease among patients with psoriasis.

In conclusion, this meta‐analysis supports a significant association between psoriasis and incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events, with a significant population attributable risk of psoriasis. Patients with psoriasis should be educated regarding the increased risk of cardiovascular disease and aggressively treated for modifiable cardiovascular risk factors. Further research into the mechanisms linking psoriasis with cardiovascular disease is warranted and may provide insights into both pathogenesis and treatment.

Disclosures

Dr Ehrin Armstrong and Dr Harskamp have no disclosures. Dr April Armstrong has served as an investigator for and an advisor to AbbVie, Amgen, Janssen, Ely Lilly, Merck, and Pfizer.

References

- 1.Kurd SK, Gelfand JM. The prevalence of previously diagnosed and undiagnosed psoriasis in US adults: results from NHANES 2003–2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009; 60:218-224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelfand JM, Stern RS, Nijsten T, Feldman SR, Thomas J, Kist J, Rolstad T, Margolis DJ. The prevalence of psoriasis in African Americans: results from a population‐based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005; 52:23-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li K, Armstrong AW. A review of health outcomes in patients with psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 2012; 30:61-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prey S, Paul C, Bronsard V, Puzenat E, Gourraud PA, Aractingi S, Aubin F, Bagot M, Cribier B, Joly P, Jullien D, Le Maitre M, Richard‐Lallemand MA, Ortonne JP. Cardiovascular risk factors in patients with plaque psoriasis: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010; 24suppl 2:23-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottlieb AB, Dann F. Comorbidities in patients with psoriasis. Am J Med. 2009; 122:1150.e1-1150.e9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qureshi AA, Choi HK, Setty AR, Curhan GC. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study of US female nurses. Arch Dermatol. 2009; 145:379-382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta NN, Li R, Krishnamoorthy P, Yu Y, Farver W, Rodrigues A, Raper A, Wilcox M, Baer A, Derohannesian S, Wolfe M, Reilly MP, Rader DJ, Vanvoorhees A, Gelfand JM. Abnormal lipoprotein particles and cholesterol efflux capacity in patients with psoriasis. Atherosclerosis. 2012; 224:218-221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedewald VE, Cather JC, Gelfand JM, Gordon KB, Gibbons GH, Grundy SM, Jarratt MT, Krueger JG, Ridker PM, Stone N, Roberts WC. AJC editor's consensus: psoriasis and coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2008; 102:1631-1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta NN, Yu Y, Pinnelas R, Krishnamoorthy P, Shin DB, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Attributable risk estimate of severe psoriasis on major cardiovascular events. Am J Med. 2011; 124:775.e1-775.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, Neimann AL, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010; 31:1000-1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006; 296:1735-1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, Azfar RS, Kurd SK, Wang X, Troxel AB. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009; 129:2411-2418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong AW, Voyles SV, Armstrong EJ, Fuller EN, Rutledge JC. A tale of two plaques: convergent mechanisms of T‐cell‐mediated inflammation in psoriasis and atherosclerosis. Exp Dermatol. 2011; 20:544-549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armstrong AW, Voyles SV, Armstrong EJ, Fuller EN, Rutledge JC. Angiogenesis and oxidative stress: common mechanisms linking psoriasis with atherosclerosis. J Dermatol Sci. 2011; 63:1-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta‐analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta‐analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000; 283:2008-2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Circulation. 2010; 121:2271-2283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986; 7:177-188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mallbris L, Akre O, Granath F, Yin L, Lindelof B, Ekbom A, Stahle‐Backdahl M. Increased risk for cardiovascular mortality in psoriasis inpatients but not in outpatients. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004; 19:225-230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stern RS, Huibregtse A. Very severe psoriasis is associated with increased noncardiovascular mortality but not with increased cardiovascular risk. J Invest Dermatol. 2011; 131:1159-1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Charlot M, Jorgensen CH, Lindhardsen J, Olesen JB, Abildstrom SZ, Skov L, Torp‐Pedersen C, Hansen PR. Psoriasis is associated with clinically significant cardiovascular risk: a Danish nationwide cohort study. J Intern Med. 2011; 270:147-157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997; 315:629-634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994; 50:1088-1101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, Sorlie PD, Sotoodehnia N, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012; 125:e2-e220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.United States Census Bureau. U.S. Department of Commerce. Available at: http://www.census.gov/x0023. Accessed June 25, 2012.

- 25.Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, Van Voorhees AS, Leonardi CL, Gordon KB, Lebwohl M, Koo JY, Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Beutner KR, Bhushan R. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008; 58:826-850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimball AB, Robinson D, Jr, Wu Y, Guzzo C, Yeilding N, Paramore C, Fraeman K, Bala M. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001–2002. Dermatology. 2008; 217:27-37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao J, Chen LH, Tu YT, Deng XH, Tao J. Prevalence of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis in central China. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009; 23:1311-1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Driessen RJ, Boezeman JB, Van De Kerkhof PC, De Jong EM. Cardiovascular risk factors in high‐need psoriasis patients and its implications for biological therapies. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009; 20:42-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmitt J, Ford DE. Psoriasis is independently associated with psychiatric morbidity and adverse cardiovascular risk factors, but not with cardiovascular events in a population‐based sample. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010; 24:885-892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prodanovich S, Kirsner RS, Kravetz JD, Ma F, Martinez L, Federman DG. Association of psoriasis with coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases and mortality. Arch Dermatol. 2009; 145:700-703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi H, Takahashi I, Honma M, Ishida‐Yamamoto A, Iizuka H. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Japanese psoriasis patients. J Dermatol Sci. 2010; 57:143-144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerdes S, Zahl VA, Knopf H, Weichenthal M, Mrowietz U. Comedication related to comorbidities: a study in 1203 hospitalized patients with severe psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008; 159:1116-1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, Neimann AL, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Cause‐specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population‐based cohort study in the U.K. Br J Dermatol. 2010; 163:586-592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wakkee M, Herings RM, Nijsten T. Psoriasis may not be an independent risk factor for acute ischemic heart disease hospitalizations: results of a large population‐based Dutch cohort. J Invest Dermatol. 2010; 130:962-967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin HW, Wang KH, Lin HC. Increased risk of acute myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis: a 5‐year population‐based study in Taiwan. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011; 64:495-501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Jorgensen CH, Lindhardsen J, Charlot M, Olesen JB, Abildstrom SZ, Skov L, Torp‐Pedersen C, Hansen PR. Psoriasis and risk of atrial fibrillation and ischaemic stroke: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2012; 33:2054-2064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stern RS, Lange R. Cardiovascular disease, cancer, and cause of death in patients with psoriasis: 10 years prospective experience in a cohort of 1,380 patients. J Invest Dermatol. 1988; 91:197-201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008; 159:895-902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brauchli YB, Jick SS, Miret M, Meier CR. Psoriasis and risk of incident myocardial infarction, stroke or transient ischaemic attack: an inception cohort study with a nested case‐control analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2009; 160:1048-1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Ledo L, Rogers JH, Armstrong EJ. Coronary artery disease in patients with psoriasis referred for coronary angiography. Am J Cardiol. 2012; 109:976-980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parsi KK, Brezinski EA, Lin TC, Li CS, Armstrong AW. Are patients with psoriasis being screened for cardiovascular risk factors? A study of screening practices and awareness among primary care physicians and cardiologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012; 67:357-362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kimball AB, Szapary P, Mrowietz U, Reich K, Langley RG, You Y, Hsu MC, Yeilding N, Rader DJ, Mehta NN. Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012; 67:76-85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehta NN, Krishnamoorthy P, Yu Y, Khan O, Raper A, Van Voorhees A, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. The impact of psoriasis on 10‐year Framingham risk. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012; 67-796-79810.1016/j.jaad.2012.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Micha R, Imamura F, Wyler von Ballmoos M, Solomon DH, Hernan MA, Ridker PM, Mozaffarian D. Systematic review and meta‐analysis of methotrexate use and risk of cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2011; 108:1362-1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryan C, Leonardi CL, Krueger JG, Kimball AB, Strober BE, Gordon KB, Langley RG, de Lemos JA, Daoud Y, Blankenship D, Kazi S, Kaplan DH, Friedewald VE, Menter A. Association between biologic therapies for chronic plaque psoriasis and cardiovascular events: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2011; 306:864-871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu JJ, Poon KY, Channual JC, Shen AY. Association between tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy and myocardial infarction risk in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2012; 148:1244-1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Solomon DH, Massarotti E, Garg R, Liu J, Canning C, Schneeweiss S. Association between disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs and diabetes risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. JAMA. 2011; 305:2525-2531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]