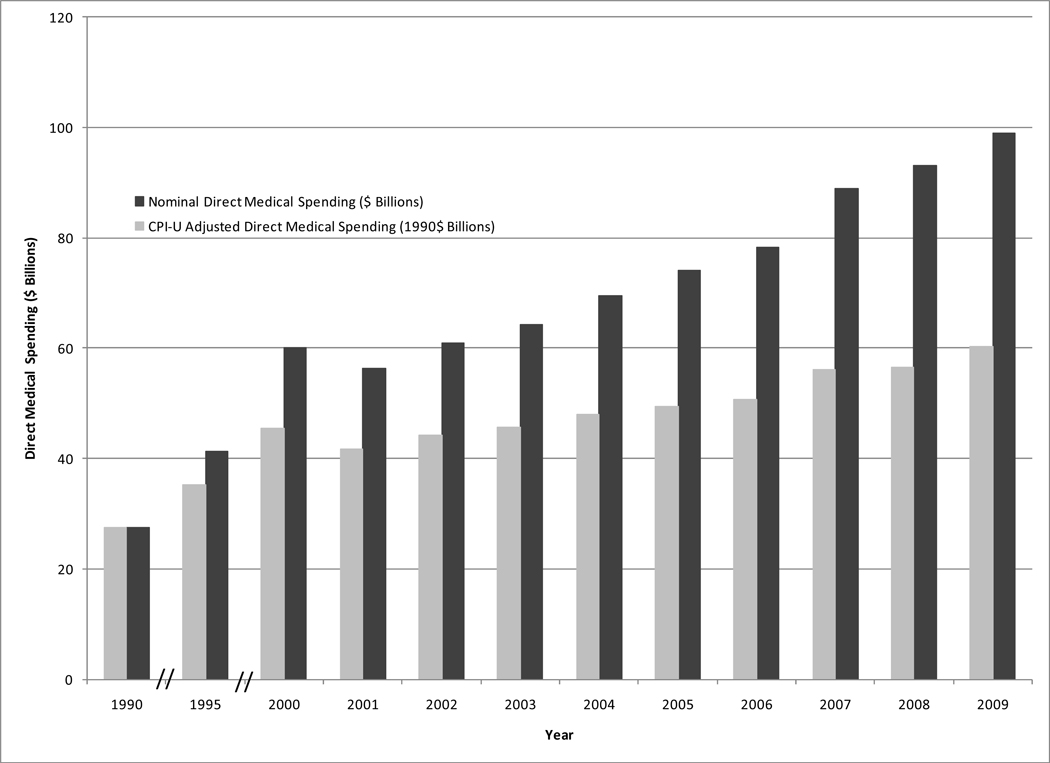

The direct medical costs of cancer have grown dramatically in the past two decades. By one set of estimates, expenditures rose from about $27 billion in 1990 to more than $90 billion in 2008, a more than two-fold increase even after adjusting for inflation (Figure 1). Other estimates place these costs even higher, at over $106B in 2006 (personal communication, M. Brown). The high cost of cancer treatment often leads to financial hardship for patients and their families, including those with health insurance. Median out-of-pocket medical spending was more than $1,500 in 2003–2004 for privately insured adults with cancer, and 10% had out-of-pocket costs exceeding $18,000.1 In a 2006 survey of adults in households affected by cancer, almost a quarter of insured respondents reported using most or all of their savings during treatment, and a similar proportion said their insurance plan paid less than expected for a medical bill.2 While more than four out of five oncologists report that their concerns regarding patients’ out-of-pocket spending influence their treatment recommendations, fewer than half say that they routinely discuss financial issues with their patients.3

Figure 1.

Nominal and inflation-adjusted direct medical spending attributed to cancer, 1990–2009.

Direct costs are personal health care expenditures for hospital and nursing home care, drugs, home care, and physician and other professional services.

Sources: 1990–1995 estimates from Brown et al.10; 2000–2009 estimates are from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, based on data from multiple sources, applying the 1995 fraction of direct medical costs attributable to cancer to annual national health expenditure estimates.11

The overall growth in spending is due to increases in both the price and the quantity of care. For example, in 2003 dollars, average spending on initial breast cancer treatment rose from about $4,000 in 1991 to over $20,000 in 2002.4 This 5-fold increase resulted from a doubling in the proportion of women receiving chemotherapy, a doubling in the cost of chemotherapy and comparable increases in the use and cost of radiation therapy. Similar trends have been observed in other types of cancer.

Increases in both the price and quantity of cancer treatment services can be linked to the introduction of new medical technology. Newer cancer therapies are not only more expensive than the prior standard of care,5 but they also expand the pool of treatment candidates. Targeted biologic agents, robot-assisted surgical techniques and computer-optimized radiation therapy all come at prices much greater than their predecessors, and, due to reduced toxicities or broader indications, they are also used in more patients. For example, minimally invasive tumor resections and highly focused radiation are used in patients who previously might have been considered untreatable because they were poor candidates for open surgical procedures. Advances in supportive medications have made systemic chemotherapy an option for older and frailer patients. In some cases novel therapies have created a new treatment paradigm for patients who previously had few options. Imatinib for chronic myelogenous leukemia is one example.

Like most people, physicians respond rationally to economic incentives. Fee-for-service physician payment methods, used by most private and public payers, reward physicians for the volume of services they provide, rather than the quality of care they deliver. Evidence suggests that physicians are, in fact, sensitive to changes in reimbursement. For example, after increasing for several years, the use of LHRH agonists for androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer patients dropped precipitously between 2004 and 2005, paralleling a cut in reimbursement.6 Among Medicare beneficiaries with metastatic cancer, reimbursement does not seem to influence the receipt of chemotherapy overall, but more generously reimbursed providers may prescribe more costly regimens.7

The problems of sky-rocketing health care costs and misaligned provider incentives have not gone unnoticed by policymakers. As we write this, US health care reform efforts are now sputtering or stalled. But there remains widespread consensus that major changes in the health care delivery system are needed in order to align incentives and reduce the growth rate of health care spending. The same conclusions have been drawn about cancer care specifically, which is often costly, fragmented and, in many cases, not supported by clear evidence of effectiveness.

Several promising proposals for delivery system reform rely on fiscal, organizational, and technical approaches to achieve two changes: shifting payment away from fee-for-service to more global, or outcome centered, payment, and pushing groups of providers together so that they act more cohesively and consistently when caring for individual patients. Two notable strategies motivated by these objectives are ‘episode-based payment’ and ‘accountable care organizations’ (ACO’s).

Under a system of episode-based payment, also known as global or bundled payment, the anticipated costs of an episode of treatment would be provided in a single payment to a provider organization. The organization would use those funds to purchase and provide all necessary services within the episode of care.8 Payments would be based on the expected costs of an episode of treatment, including the costs of drugs, tests and other care. Shifting to this type of reimbursement should encourage providers to shop carefully for the services patients need, favoring lower cost goods and services when they are just as effective. Likewise, because the total cost of care is included in a single payment, providers would have an incentive to work together, improving care coordination and reducing duplication.

With ACOs, payment would also move away from fee-for-service methods, focusing more on covering the costs of organizations that provide care for populations of patients. Using objective and standardized measures of performance, ACOs would align the incentives of participating providers with the promise of shared savings for achieving or exceeding specific benchmarks.9 In ACOs providers would be rewarded for delivering care that adheres with evidence-based guidelines and is likely to improve health outcomes.

Episode-based payment and ACOs both encourage providers to make choices that benefit their patients and make care more affordable by linking payment to the quality of care the patient receives, not the volume of services the provider delivers. Both would exert downward pressure on prices and constrain quantity by rewarding prudent purchasing and appropriate utilization. Both approaches also face hurdles to implementation. For episode-based payment to work, the definition of an episode must be sufficiently narrow to accommodate a homogenous level of payment, yet sufficiently broad that providers have a large enough denominator of patients so as to counteract the impact of the rare outlier. The success of ACOs depends on the quality of performance measurement. Benchmarks must be realistic, and the structure of shared savings arrangements must balance rewarding high achievement with rewarding performance improvement. Episode-based payment and ACOs will also require appropriate risk-adjustment methods and sound information on the comparative effectiveness of different diagnostic and treatment approaches.

Cancer care is well-suited to both of these payment reform proposals. Adjuvant chemotherapy, for example, is an apt candidate for episode-based payment, with episodes defined by treatment cycles or an entire course of therapy. Episode definitions could also be expanded to encompass other aspects of treatment, including radiation and surgery. At the same time, cancer surveillance and oncology practice already favor the data collection required for ACOs, and the multi-disciplinary nature of cancer treatment creates a strong incentive to coordinate care.

As the debate over remedies for our health care system simmers, stakeholders on all sides will continue to examine the strategies for cost containment. Care for cancer patients will be a focus. The expanding financial burden of cancer, its rising incidence and prevalence, and the steady introduction of new therapies and tests that will increase costs but have the potential to improve patient outcomes all push it to the top of the list.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Lawless G, Crown WH, Willey V. Benefit design and specialty drug use. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2006;25(5):1319–1331. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.5.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.USA Today/Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard School of Public Health National Survey of Households Affected by Cancer. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann PJ, Palmer JA, Nadler E, Fang C, Ubel P. Cancer therapy costs influence treatment: a national survey of oncologists. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2010;29(1):196–202. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warren JL, Yabroff KR, Meekins A, Topor M, Lamont EB, Brown ML. Evaluation of trends in the cost of initial cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(12):888–897. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bach PB. Limits on Medicare's ability to control rising spending on cancer drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):626–633. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0807774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weight CJ, Klein EA, Jones JS. Androgen deprivation falls as orchiectomy rates rise after changes in reimbursement in the U.S. Medicare population. Cancer. 2008;112(10):2195–2201. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobson M, O'Malley AJ, Earle CC, Pakes J, Gaccione P, Newhouse JP. Does reimbursement influence chemotherapy treatment for cancer patients? Health affairs (Project Hope) 2006;25(2):437–443. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.2.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Brantes F, Rosenthal MB, Painter M. Building a bridge from fragmentation to accountability--the Prometheus Payment model. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1033–1036. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0906121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher ES, McClellan MB, Bertko J, et al. Fostering accountable health care: moving forward in medicare. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2009;28(2):w219–w231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.w219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown ML, Lipscomb J, Snyder C. The burden of illness of cancer: Economic cost and quality of life. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:91–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. NHLBI Fact Book (FY 2000- FY 2009 editions) Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; [Google Scholar]