Abstract

We examined, in 106 community-dwelling middle-aged non-smokers, the time-course and the acute effects of fine particles (PM2.5) on heart rate variability (HRV), which measures cardiac autonomic modulation (CAM). 24-hour beat-to-beat ECG data were visually examined. Artifacts and arrhythmic beats were removed. Normal beat-to-beat RR data were used to calculate HRV indices. Personal PM2.5 nephelometry was used to estimate 24-hour individual-level real-time PM2.5 exposures. We use linear mixed-effects models to assess autocorrelation- and other major confounder-adjusted regression coefficients between 1-6 hour moving averages of PM2.5 and HRV indices. The increases in preceding 1-6 hour moving averages of PM2.5 was significantly associated with lower HF, LF, and SDNN, with the largest effect size at 4-6 hour moving averages and smallest effects size at 1 hour moving average. For example, a 10 μg/m3 increase in 1-hour and 6-hour moving averages was associated with 0.027 and 0.068 ms2 decrease in log-HF, respectively, and with 0.024 and 0.071 ms2 decrease in log-LF, respectively, and with 0.81 and 1.75 ms decrease in SDNN, respectively (all p values < 0.05). PM2.5 exposures are associated with immediate impairment of CAM. With a time-course of within 6 hours after elevated PM2.5 exposure, with the largest effects around 4-6 hours.

Keywords: Particulate Matter, Fine Particles, Heart Rate Variability, Autonomic Modulation, Cardiovascular Disease, Personal Nephelometry

Introduction

Recently, both scientific and regulatory communities have focused their attention on the evidence of the adverse effects of air pollution on cardiovascular disease. Numerous studies have consistently demonstrated that exposure to ambient air pollution, especially fine particulate matters with aerodynamic diameter < 2.5μm (PM2.5), is associated with increased cardiopulmonary mortality and morbidity (Brook et al, 2004; Pope et al, 2002; Dockery et al, 1993; Peters et al, 2000; Peters et al, 2001a). Previous studies have proposed several hypothesized mechanisms for PM-related adverse cardiac effects, including autonomic modulation impairment (Liao et al, 1999; Luttmann-Gibson et al, 2006; Park et al, 2005; Gold et al, 2000; Magari et al, 2001), prolonged ventricular repolarization (Yue et al, 2007; Lux and Pope, 2009), PM induced oxidative stress (Sørensen et al, 2003), systematic inflammation (Ridker et al, 1997; Peters et al, 2001b), and blood coagulation (Ghio et al, 2000; Schwartz, 2001). The findings from the PM effects on cardiac autonomic modulation were the most consistent among these competing mechanisms. Together with the large body of evidence supporting that impaired cardiac autonomic modulation (CAM) is associated with increased risk of incident coronary heart disease, sudden cardiac death, and all cause mortality (Liao et al, 1997; Martin et al, 1987; Tsuji et al, 1994), PM effects on CAM has emerged as one of the most promising mechanisms responsible for the link between PM and cardiac disease risk.

To date, however, few published studies have investigated the time course of the PM effect on CAM. Therefore, we carried out this study to investigate the CAM effects and time course of individual-level exposures to PM2.5 in a community-dwelling sample of healthy individuals.

Population and Methods

Population

The data collected for the Air Pollution and Cardiac Risk and its Time Course (APACR) study are used for this report. The APACR study, funded by NIEHS (1 R01 ES014010), was designed to investigate the mechanisms and the time-course of the adverse effects of PM2.5 on cardiac electrophysiology, hemostasis, thrombosis, and systemic inflammation. All study participants were recruited from community-dwelling individuals residing in central Pennsylvania, mostly from the Harrisburg Metropolitan area. The inclusion criteria for the APACR study included those who were > 45 years of age, non-smokers, and not having severe cardiac problems (defined as diagnosed valvular heart disease, congenital heart disease, acute myocardial infarction or stroke within 6 months, or congestive heart failure). The NIH-funded Penn State College of Medicine General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) Community Recruitment Specialists and GCRC-organized community outreach activities supported subject recruitment. The GCRC maintains a list of community-dwelling individuals for various health related studies. The APACR study participants were numerated from the GCRC's potential participants list. All study participants were examined between November, 2007 and June, 2009. Approximately 75% of the individuals we approached and who met our inclusion criteria enrolled in the study. Our targeted sample size was 100 individuals, and we enrolled and examined 106 individuals for the APACR study.

Study participants were examined in the GCRC in the morning between 8 and 10 AM on Day-1. All participants fasted for at least 8 hours before the clinical examination. After completing a health history questionnaire, a trained research nurse measured seated blood pressure three times, height, and weight, and drew 50 ml of blood for biomarker assays according to the blood sample preparation protocols. A trained investigator connected the PM2.5 and Holter ECG recorders. Participants were given an hourly activity log to record special events that occurred over the next 24 hours, including outdoor activities, exposure to traffic on the street, traveling in an automobile, and any physical activities. The entire clinical examination session lasted about 1 hour. Participants were then released to proceed with their usual daily routines. The next morning, the participants returned to the GCRC to remove the PM and Holter monitors, deliver the completed activity log, have another 50 ml of blood drawn, and the collection of a urine sample. Then, an exercise echocardiography was performed on each participant according to a standardized protocol to measure the participant's ventricular function and structure. The entire day-2 session lasted for about 1 hour and 45 minutes. Penn State University College of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. Each participant was reimbursed $50, one breakfast certificate in the hospital cafeteria, and the mileage of the transportation required for participating in the APACR study.

Personal Exposure Monitoring

A personal DataRam (pDR, model 1200, Thermo Scientific, Boston MA) was used in combination with a PM2.5 size-selective inlet driven by a 1.5 L/ min pump to obtain the personal real time 24-hour PM2.5 exposure estimates. The pDR, size-selective inlet, and the pump were fixed into the inside of a modified and locked 6 × 6 × 9 inch solid lunch box, with the inlet open towards the outside of the lunch box. The pDR is a lightweight, self-recording optical nephelometer that uses light scattering physics of the fine particles to detect the real-time concentrations of particles of various sizes. This monitor has been widely used in other human exposure panel studies investigating human exposure factors as well as integrated exposure/epidemiological studies involving lung function and cardiovascular and other observable health effects (Reed et al, 2000; Rea et al, 2001; Wallace, et al, 2005; Williams et al, 2009). The device has a response that is a function of the number and mean aerodynamic size of the particles entering its optical chamber. The resulting response is then directly proportional to a calibrated particle range of PM2.5 sized aerosol. This calibration was performed by the manufacturer just prior to the start of the field study. The PM2.5 particle size selection was achieved by using an active pump with a cyclone inlet (KTL SCC1.062, BGI Inc., Waltham, MA) at a flow rate of 1.5 L/Min. The standard operation procedure (SOP) for the use of pDR, including the pump volume setting, zeroing, calibration, filter loading, application, data transfer, and data validation, as well as chemical analysis of filters for major PM2.5 species, were developed by the APACR investigators (Penn State University 2008a). The standardized procedures were rigorously followed prior to and right after each use of the pDR. For this report, the real-time PM2.5 concentrations originally recorded at 1-minute intervals over the 24-hr sampling period were summarized as 30-min segment means. Therefore, each participant contributed 48 PM2.5 concentration data points in this report.

Continuous Ambulatory Electrocardiogram (Holter ECG)

The collection of heart rate data in panel studies has been widely reported as a means to investigate the effects of environmental exposures (Liao et al, 1999; Luttmann-Gibson et al, 2006; Park et al, 2005). In this study, a high fidelity (sampling frequency 1000 Hz) 12-lead HScribe Holter System (Mortara Instrument, Inc) was used for 24-hour Holter beat-to-beat ECG data collection. The high fidelity ECG significantly increases the resolution and enhances the accuracy of various wave form measurements. The Holter ECG data are scanned to a designated computer for offline processing by an experienced investigator using specialized SuperECG software (also developed by Mortara Instrument, Inc). The SOPs for the APACR study have been developed by the study investigators (Penn State University 2008b, 2008c) and were rigorously followed in the data collection and interpretation processes. Briefly, the “Holter ECG Data Collection and Analysis Procedures” (Penn State University 2008b) were followed rigorously to prepare, hook-up, calibrate, and start the Holter digital recorder. After 24 hours of recording, a trained investigator followed the SOP to retrieve and archive the beat-to-beat ECG data for offline processing. The main objective of the offline processing was to verify the Holter-identified ECG waves, and to identify and label additional electronic artifacts and arrhythmic beats in the ECG recording. Finally, a single the research investigator followed the “SuperECG Manual,” (Penn State University 2008c) to perform beat-to-beat ECG analysis to calculate ECG parameters.

HRV data

We performed time and frequency domain HRV analysis on the ECG recording, after removing artifacts and ectopic beats with standardized visuall inspection. We calculated HRV indices from each 30-minute segment using the SuperECG package (Mortara Instrument, Inc) according to the current recommendations (Task Force, 1996). The following HRV indices were used as indices of CAM: standard deviation of all normal RR intervals (SDNN, ms), square root of the mean of the sum of the squares of differences between adjacent RR (RMSSD, ms), heart rate (beat per min), power in the low frequency range (0.04-0.15 Hz, LF), power in the high frequency range (0.15-0.40 Hz, HF), and the ratio of LF and HF (LF/HF).

Weather variables

We obtained real-time temperature and relative humidity using the HOBO H8 logger (Onset Computer Corporation, Bourne, MA), directly fixed on top of the lunch box housing the pDR. The real-time temperature and relative humidity were recorded at 1-minute intervals initially. For each participant, we calculated 30-minute segment specific averages, corresponding to the PM2.5 and Holter measures. Therefore, these weather co-variables are treated as repeated measures, and each individual contributed 48 data points for each variable.

Other participant-level co-variables

A standardized questionnaire administered on Day-1 of the study was used to collect the following individual-level information: (a) demographic variables, including age, race, sex, highest education level; (b) medication uses, including anti-anginal medication, anti-hypertensive medication, and anti-diabetic medication; and (c) physician diagnosed chronic disease history, including CVD (including revascularization procedures and myocardial infarction), hypertension, and diabetes. The averages of the 2nd and 3rd measures of seated systolic and diastolic blood pressures on Day-1 were used to represent a participant's blood pressure levels. Day-1 fasting glucose was measured by Penn State GCRC central laboratory. CVD was defined by anti-anginal medication use or a history of CVD. Hypertension was defined by anti-hypertensive medication use, physician diagnosed hypertension, systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, or diastolic blood pressure ≥90mm Hg. Diabetes was defined by anti-diabetic medication use, physician diagnosed diabetes, or fasting glucose >126 mg/dl. Body mass index (BMI) was defined as the ratio of weight to height squared (BMI, kg/m2).

Statistical analysis

We treated HRV, PM2.5, and the weather variables as repeated measurements in 30-minute segments; thus, each individual contributed 48 data points for each of these variables. In some individuals, because of accidental detachments of the ECG electrodes, the total length of usable ECG data within certain segments was less than 20 minutes (2/3 of the total 30 minutes). These segments were excluded from our regression analysis. As a result, this report included 5 050 pairs (out of a total of 5 088 possible pairs from 106 individuals) of 30-minute-based PM2.5 and HRV data in the regression analysis. For each individual, we calculated the 24-hour overall PM2.5, temperature, and relative humidity based on 48 data points. From these individual averages, we then calculated the 24-hour overall exposures for our study population. One to six hour moving average PM2.5 concentrations were also calculated for each 30-minute segment HRV index. These moving averages were calculated in two ways: 1) using all available data points regardless of the amount of missing data (e.g., five 30-minute segment means were used to calculate a 2-hour moving average) or 2) the 75% rule approach – we calculated these moving averages when at least 75% of the total data points were present within the respective moving average time frame (e.g., at least 90 minutes of PM2.5 data (four 30-minute segment means) were required for a 2-hour moving average calculation). For each individual, we calculated the 24-hour means of the 1–6 hour moving averages, and then from these individual mean moving averages, we calculated the 24-hour overall exposures for our study population on each of the six moving averages we reported here. In the regression analysis associating PM2.5 moving averages to 30-minute based repeated HRV variables, we confirm the finding from the first approach with that from the second approach to the moving average calculation. We used linear mixed-effect models to assess the autocorrelation corrected regression coefficients between 1-6 hour moving average PM2.5 concentrations and the 30-min HRV measures. All associations were adjusted for age, sex, race, temperature, relative humidity, diabetes, hypertension, and history of CVD. We used the SAS statistical package (version 9; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) for all analyses. All results were expressed per 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5, and α=0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

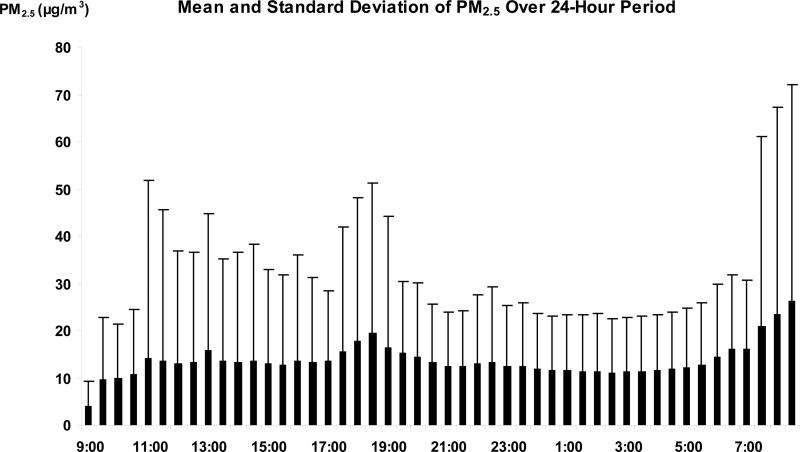

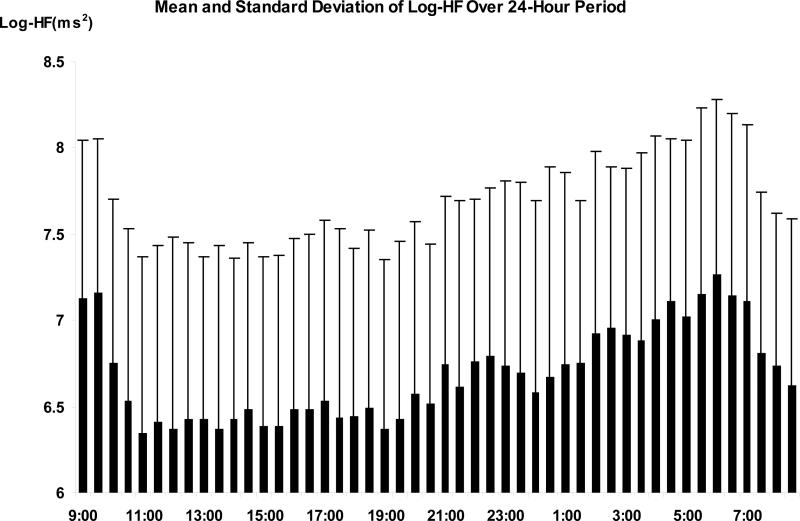

Table 1 presents the time independent demographic and clinical characteristics, and the time dependent HRV indices. The mean age of the participants was 56 years, with 74% non-Hispanic white, 59% females, and 43% having chronic diseases (CVD, hypertension, or diabetes). The prevalence of CVD, hypertension, and diabetes was 8.5%, 34.9%, and 7.6%, respectively. Figures 1 and 2 show the time of the day specific distribution (mean and standard deviation) of the PM2.5 levels and log-HF as an example of HRV indices calculated from the entire set of study participants. The overall average 24-hour exposure to PM2.5 and its standard deviation, as well as the mean of 1-6 hour based moving averages and their standard deviations are presented in Table 2. From these summary statistics, both environmental and HRV variables presented significant variation over the study period. The environmental variables also showed large inter-individual variations. However, as expected, since all the moving average concentrations were calculated from the same 48 data points for each individual, there was little variation among the six moving averages of PM2.5 exposures in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study population

| Hypertension, Diabetes, or CVD |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | All subjects N=106 | No N=60 | Yes N=46 |

| Age | 56.23 (7.61) | 55.55 (8.19) | 57.12 (6.76) |

| Gender (% Male) | 40.57 | 40.00 | 41.30 |

| Race (% White) | 73.58 | 71.67 | 76.09 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 88.82 (25.14) | 84.64 (10.04) | 94.29 (35.95) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.71 (5.86) | 26.19 (4.31) | 29.69 (6.98) |

| CVD History (%) | 8.49 | 0.00 | 19.57 |

| Hypertension History (%) | 34.91 | 0.00 | 84.78 |

| Diabetes History (%) | 7.55 | 0.00 | 17.39 |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||

| Systolic | 121.88 (15.73) | 117.05 (11.86) | 128.18 (17.93) |

| Diastolic | 75.07 (9.22) | 73.12 (8.34) | 77.62 (9.77) |

| Education | |||

| College or higher (%) | 78.30 | 73.33 | 84.78 |

| Log-HF (ms2) | 6.68 (1.04) | 6.80 (1.00) | 6.54 (1.07) |

| Log-LF (ms2) | 6.28 (0.98) | 6.41 (0.94) | 6.10 (1.00) |

| LF/HF | 0.69 (0.20) | 0.71 (0.20) | 0.67 (0.19) |

| SDNN (ms) | 66.40(31.35) | 69.37 (31.06) | 62.57 (31.32) |

| RMSSD (ms) | 26.12 (18.56) | 26.86 (17.78) | 25.15 (19.25) |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 75.87 (15.23) | 75.32 (15.17) | 76.59 (15.30) |

Results are presented as mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables

Figure 1.

Time specific means and standard deviations of PM2.5

Figure 2.

Time specific means and standard deviations of Log-HF.

Table 2.

24-hour mean and moving averages of PM2.5, temperature, and relative humidity

| 24-hour Mean | 1-hour moving average | 2-hour moving average | 3-hour moving average | 4-hour moving average | 5-hour moving average | 6-hour moving average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 13.66 (11.77) | 13.41 (18.56) | 13.36 (16.79) | 13.24 (15.88) | 13.23 (15.26) | 13.19 (14.85) | 13.21 (14.44) |

| Temperature (°C) | 21.75 (2.57) | 21.78 (3.63) | 21.80 (3.27) | 21.82 (3.19) | 21.84 (3.14) | 21.86 (3.09) | 21.87 (3.04) |

| Relative Humidity (%) | 39.69 (9.82) | 39.70 (11.78) | 39.75 (11.55) | 39.69 (11.37) | 39.71 (11.21) | 39.63 (11.07) | 39.65 (10.95) |

Results are presented as mean (standard deviation).

Multivariable-adjusted regression coefficients and standard errors for the associations between PM2.5 and HRV indices are presented in Table 3. As indicated in the table, there is a significant inverse relationship between PM2.5 and log-HF, log-LF, and SDNN in 1-6 hours. An increase in PM2.5 concentration in the preceding 3-5 hours was also significantly associated with elevated heart rate. LF/HF ratio and RMSSD were not statistically significant associated with PM2.5. The pattern of association between elevated PM2.5 and HRV variables remained unchanged after additional adjustment for chronic diseases. The association between PM2.5 and HRV indices did not change substantially when we applied the 75% available data rule in the calculation of the moving averages (Model 3 in Table 3).

Table 3.

Regression coefficients (SE) of HRV indices associated with 10 μ/m3 increment of PM2.5 concentration

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moving average | β (SE) | P value | β (SE) | P value | β (SE) | P value | |

| Log_HF | 1 hour | -0.033 (0.012) | <0.01 | -0.029 (0.012) | 0.02 | -0.027 (0.012) | 0.03 |

| 2 hour | -0.047 (0.016) | <0.01 | -0.041 (0.016) | <0.01 | -0.042 (0.016) | <0.01 | |

| 3 hour | -0.062 (0.017) | <0.01 | -0.055 (0.017) | <0.01 | -0.057 (0.018) | <0.01 | |

| 4 hour | -0.073 (0.019) | <0.01 | -0.065 (0.019) | <0.01 | -0.063 (0.019) | <0.01 | |

| 5 hour | -0.071 (0.019) | <0.01 | -0.062 (0.019) | <0.01 | -0.060 (0.020) | <0.01 | |

| 6 hour | -0.078 (0.020) | <0.01 | -0.068 (0.020) | <0.01 | -0.068 (0.022) | <0.01 | |

| Log_LF | 1 hour | -0.029 (0.011) | 0.01 | -0.024 (0.011) | 0.03 | -0.024 (0.011) | 0.04 |

| 2 hour | -0.044 (0.015) | <0.01 | -0.037 (0.015) | <0.01 | -0.040 (0.015) | <0.01 | |

| 3 hour | -0.060 (0.017) | <0.01 | -0.051 (0.017) | <0.01 | -0.056 (0.017) | <0.01 | |

| 4 hour | -0.073 (0.018) | <0.01 | -0.064 (0.018) | <0.01 | -0.064 (0.019) | <0.01 | |

| 5 hour | -0.071 (0.019) | <0.01 | -0.061 (0.019) | <0.01 | -0.062 (0.020) | <0.01 | |

| 6 hour | -0.078 (0.019) | <0.01 | -0.067 (0.019) | <0.01 | -0.071 (0.021) | <0.01 | |

| LF/HF | 1 hour | -0.001 (0.002) | 0.50 | 0.0004 (0.002) | 0.85 | -0.001 (0.002) | 0.70 |

| 2 hour | -0.003 (0.002) | 0.30 | -0.001 (0.002) | 0.63 | -0.002 (0.003) | 0.38 | |

| 3 hour | -0.003 (0.003) | 0.33 | -0.001 (0.003) | 0.70 | -0.002 (0.003) | 0.41 | |

| 4 hour | -0.003 (0.003) | 0.26 | -0.002 (0.003) | 0.60 | -0.003 (0.003) | 0.36 | |

| 5 hour | -0.004 (0.003) | 0.20 | -0.002 (0.003) | 0.51 | -0.003 (0.003) | 0.33 | |

| 6 hour | -0.004 (0.003) | 0.23 | -0.002 (0.003) | 0.58 | -0.003 (0.003) | 0.34 | |

| SDNN | 1 hour | -0.99 (0.35) | <0.01 | -0.84 (0.35) | 0.02 | -0.81 (0.35) | 0.02 |

| 2 hour | -1.39 (0.42) | <0.01 | -1.18 (0.42) | <0.01 | -1.13 (0.42) | <0.01 | |

| 3 hour | -1.62 (0.45) | <0.01 | -1.39 (0.45) | <0.01 | -1.34 (0.45) | <0.01 | |

| 4 hour | -1.83 (0.47) | <0.01 | -1.58 (0.47) | <0.01 | -1.48 (0.49) | <0.01 | |

| 5 hour | -1.89 (0.48) | <0.01 | -1.63 (0.49) | <0.01 | -1.58 (0.51) | <0.01 | |

| 6 hour | -2.00 (0.49) | <0.01 | -1.73 (0.49) | <0.01 | -1.75 (0.54) | <0.01 | |

| RMSSD | 1 hour | 0.18 (0.21) | 0.41 | 0.19 (0.21) | 0.36 | 0.23 (0.21) | 0.28 |

| 2 hour | 0.27 (0.29) | 0.36 | 0.30 (0.29) | 0.31 | 0.39 (0.30) | 0.20 | |

| 3 hour | 0.10 (0.34) | 0.76 | 0.14 (0.34) | 0.67 | 0.26 (0.36) | 0.46 | |

| 4 hour | -0.15 (0.37) | 0.69 | -0.10 (0.38) | 0.78 | 0.03 (0.40) | 0.95 | |

| 5 hour | 0.08 (0.39) | 0.83 | 0.14 (0.40) | 0.73 | 0.36 (0.44) | 0.41 | |

| 6 hour | -0.06 (0.41) | 0.89 | -0.001 (0.41) | 0.99 | 0.24 (0.47) | 0.61 | |

| HR | 1 hour | 0.22 (0.13) | 0.10 | 0.21 (0.13) | 0.11 | 0.20 (0.13) | 0.13 |

| 2 hour | 0.31 (0.19) | 0.10 | 0.31 (0.19) | 0.32 | 0.22 (0.20) | 0.27 | |

| 3 hour | 0.61 (0.23) | <0.01 | 0.60 (0.24) | 0.01 | 0.56 (0.24) | 0.03 | |

| 4 hour | 0.77 (0.27) | <0.01 | 0.76 (0.27) | <0.01 | 0.71 (0.30) | 0.02 | |

| 5 hour | 0.76 (0.29) | <0.01 | 0.75 (0.29) | <0.01 | 0.65 (0.33) | 0.05 | |

| 6 hour | 0.82 (0.30) | <0.01 | 0.81 (0.30) | <0.01 | 0.63 (0.37) | 0.08 | |

Model 1: Adjusted for age, sex, race, temperature, and relative humidity

2: Adjusted for age, sex, race, temperature, relative humidity, and chronic disease status

3: Adjusted for age, sex, race, temperature, relative humidity, and chronic disease status with moving average set to missing if available data points less than 75%

Discussion

Recently, various studies have suggested several important potential underlying mechanisms that link PM2.5 air pollution and cardiac disease (Liao et al, 1999; Yue et al 2007; Sørensen et al, 2003; Ridker et al, 1997; Ghio et al, 2000). One of the most promising potential mechanisms is the adverse effect of fine particle air pollution on cardiac autonomic modulation. Specifically, increased PM2.5 concentration may result in imbalanced cardiac autonomic modulation, i.e. a reduced parasympathetic and increased sympathetic modulation. This PM2.5-HRV association has been demonstrated to be acute in terms of occurring within days (Liao et al, 2004; de Hartog et al, 2009). However, to our knowledge, few studies have systematically examined the exact time-course of the PM effect on HRV.

The data from this community-dwelling sample of healthy non-smokers confirmed a significant adverse association between elevated individual-level exposures to PM2.5 and CAM. Most importantly, these data indicated that the time course of the PM2.5 effect on CAM occurred acutely, all within 6 hours of exposures to elevated PM2.5 with the strongest effects occurring between 4-6 hours. Other studies have indicated several potential mechanisms that link PM pollution and cardiovascular disease risk. These mechanisms ranged from shorter term to longer term effects of PM. The former included shorter term PM effects on CAM ((Liao et al, 1999; Park et al, 2005), on lowered threshold of arrhythmia (Huikuri et al, 2001; Liao et al, 2009), on potential myocardium ischemia (Zhang et al, 2009), on ventricular reporlorization (Yue et al, 2007; Lux and Pope, 2009), and on blood coagulation (Liao et al, 2004;) The latter included longer-term PM effects on atherosclerosis and plaque rupture (Suwa et al, 2002; Sun et al, 2005), on prothrombin time and on thrombosis risk (Barrcarelli et al, 2008). Our time course-results are suggestive of an acute adverse effect of PM2.5 on CAM impairment. Such an acute effects on CAM suggest an acute triggering effect of PM2.5 in terms of its mechanistic impact on the onset of cardiac events, such as arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death.

It is worthwhile noting that several previous studies reported chronic cardiopulmonary disease as a significant effect modifier in the relationship between PM air pollution and decreased HRV, indicating higher susceptibility to an air pollution effect on HRV among persons with cardiopulmonary conditions (Park et al, 2005; Liao et al, 2004; Holguin et al, 2003). In this study, however, we did not find a significant interaction between PM2.5 concentration and history of CVD or diabetes. This may be due to the small number of participants that had a positive history of CVD (N=9) or diabetes (N=8). Given that the total length of data collection on both HRV and PM was 24 hours in parallel, we chose to analyze the exposure and outcome association up to a 6-hour moving average only, since moving averages of longer duration would lead to a significant proportion of the calculated moving averages being based on the same set of data points. Thus, a significant proportion of the longer-term moving averages would be identical to the shorter-term moving averages.

When comparing to previous studies, one of the strengths of current study is using individual-level PM2.5 concentration measured on a real-time basis over 24 hours. For example, in the EPA Baltimore study (Liao et al, 1999), PM concentration was measured from a monitor located in the center of a retirement facility. In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study (Liao et al. 2004), and in the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) study (Whitsel et al, 2009), the PM concentrations were mathematically estimated either using a simple area average of the ambient concentrations (Liao et al. 2004), or the spatial correlation based ambient estimations at the participant's primary homes (Whitsel et al, 2009). These studies all relied on the ambient exposure data at the community or the residence levels, which may not be representative of the true exposures that the study participants experienced. In contrast, current study used a personal PM2.5, which enabled us to capture individual-level exposures during the entire 24-hour period. The individual level exposure and health outcome data collected in this study allow us the opportunity to better model the PM2.5 and CAM association much more efficiently and it also enabled us to “control” for many individual-level unmeasured factors that may influence the CAM measures. We also treated both the exposure and outcome data as 30-minute based repeated measures, and thus benefited from increased statistical power in associating the PM exposures to HRV variables.

Although the results generated from this study are compelling, there are still several limitations. First, we excluded smokers and people who had severe cardiac events in the past 6 months. Therefore, one may not be able to generalize the association seen in these data to individuals with more severe cardiovascular disease. It is possible that the PM2.5 effect on HRV might be greater in individuals with underlying structural heart disease, ischemic heart disease, or heart failure. Secondly, the effect sizes we identified in this study are relatively small, but this is consistent with previous studies of the PM effect on HRV (Liao et al, 1999; Luttmann–Gibson et al, 2006). Thirdly, the majority of the participants reported that they stayed indoors most of the time during the 24-hour study period, except when they had to travel by automobile. This behavior pattern is reflected in the relatively low levels of exposure to PM2.5. In general, our participants had limited indoor exposures, such as second-hand smoking. Thus, we were unable to assess whether exposures at much higher levels would exhibit similar associations. However, we purposely used the personal monitors and real-time Holter system to collect the true individual-level exposure and routine ECG data, respectively. We argue that the associations we observed in these individuals are more reflective of their routine exposure and outcome associations. Fourth, the ECG data from Holter were not collected under a controlled, supine position setting. Thus, the short-term variation of other factors that may impact the HRV cannot be fully accounted for. However, it is not feasible to keep a healthy participant in a supine indoor position for 24 hours. Even if this were achieved, the results from such a study design would likely have limited variation in PM2.5 exposure levels, and would have limited utility for generalization to a real world situation. In contrast, our study captures the range of activities occurring in real life, including time spent outdoors, time spent in commuting in automobile, and various other activities associated with a disease-free community-dwelling individual. Lastly, the pDR estimated PM2.5 concentrations over 24 hours were used in this study as an estimation of personal exposures. This nephelometric device responds to the optical properties of the particles it encounters rather than the true particle gravimetric properties. It should be recognized that the optical properties calibrated using Arizona road dust might not be highly representative of the actual PM2.5 aerosol the study participants encountered. Previous studies have reported that the Arizona road dust calibrated pDR, identical to the one used in this study, provides mass concentration estimates in good agreement with that from gravimetric mass-based measures (correlation coefficients > 0.8), but the pDR often yield estimates 10-50% higher than that from gravimetric mass-based measures (Reed et al, 2000; Rea et al, 2001; Williams et al, 2008). Based on these validation studies, the personal exposures used in this study might be slight, but systematically, overestimate the true environmental conditions that existed. However, such a systematic over estimation of the true exposures to PM2.5 should not have biased the pattern of the observed associations. It can be argued that the reported effect sizes per 10 μg/m3 increase in the pDR estimated PM2.5 actually represent effect sizes of only 6.67 – 9.00 μg/m3 increase in the true PM2.5 exposure, if pDR systematically overestimates the true exposure by 10-50%. In other words, the reported effect sizes in this study were systematically underestimated.

In conclusion, these data confirmed a significant adverse relationship between individual-level PM2.5 exposures and cardiac autonomic modulation as measured by HRV indices towards a reduced parasympathetic modulation and an increased sympathetic outflow. Most importantly, our data suggest that the effect of elevated PM2.5 exposure on impaired CAM occurred within 6 hours after elevated PM2.5 exposures, with the strongest effects occurring between 3 to 6 hours. Such an acute effect of PM2.5 on CAM may contribute to acute increase in the risk of cardiac disease, or trigger the onset of acute cardiac events, such as arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death.

Acknowledgement

This study is funded by NIEHS (1 R01 ES014010). The authors wish to thank Dr. David Mortara of Mortara Instrument, Inc. for providing the SuperECG software for the analysis of the electrocardiographic data.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baccarelli A, Martinelli I, Zanobetti A, Grillo P, Hou LF, Bertazzi PA, et al. Exposure to particulate air pollution and risk of deep vein thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(9):920–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.9.920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Franklin B, Cascio W, Hong Y, Howard G, Lipsett M, et al. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;109:2655–2671. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128587.30041.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hartog JJ, Lanki T, Timonen KL, Hoek G, Janssen NA, Ibald-Mulli A, et al. Associations between PM2.5 and heart rate variability are modified by particle composition and beta-blocker use in patients with coronary heart disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:105–111. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockery DW, Pope CA, 3rd., Xu X, Spengler JD, Ware JH, Fay ME, et al. An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1753–1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312093292401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghio AJ, Kim C, Devlin RB. Concentrated ambient air particles induce mild pulmonary inflammation in health human volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(3 Pt 1):981–988. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9911115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold DR, Litonjua A, Schwartz J, Lovett E, Larson A, Nearing B, et al. Ambient Pollution and Heart Rate Variability. Circulation. 2000;101:1267–1273. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.11.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holguín F, Téllez-Rojo MM, Hernández M, Cortez M, Chow JC, Watson JG, et al. Air pollution and heart rate variability among the elderly in Mexico City. Epidemiology. 2003;14:521–527. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000081999.15060.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huikuri HV, Castellanos A, Myerburg RJ. Sudden death due to cardiac arrhythmias. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(20):1473–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra000650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Cai J, Rosamond WD, Barnes RW, Hutchinson RG, Whitsel EA, et al. Cardiac autonomic function and incident coronary heart disease: a population-based case-cohort study. The ARIC Study. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;15(145):696–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/145.8.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Creason J, Shy C, Williams R, Watts R, Zweidinger R. Daily Variation of Particulate Air Pollution and Poor Cardiac Autonomic Control in the Elderly. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:521–525. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Duan Y, Whitsel EA, Zheng ZJ, Heiss G, Chinchilli VM, et al. Association of higher levels of ambient criteria pollutants with impaired cardiac autonomic control: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:768–777. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Heiss G, Chinchilli VM, Duan Y, Folsom AR, Lin HM, et al. Association of criteria pollutants with plasma hemostatic/inflammatory markers: a population-based study. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2005 Jul;15(4):319–328. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Whitsel EA, Duan Y, Lin HM, Quibrera PM, Smith R, et al. Ambient particulate air pollution and ectopy--the environmental epidemiology of arrhythmogenesis in Women's Health Initiative Study, 1999-2004. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2009;72(1):30–8. doi: 10.1080/15287390802445483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttmann-Gibson H, Suh HH, Coull BA, Dockery DW, Sarnat SE, Schwartz J, et al. Short-term effects of air pollution on heart rate variability in senior adults in Steubenville, Ohio. J Occup Environ Med. 2006 Aug;48(8):780–788. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000229781.27181.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lux RL, Pope CA., 3rd Air pollution effects on ventricular repolarization. Res Rep Health Eff Inst. 2009;141:3–20. discussion 21-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magari SR, Hauser R, Schwartz J, Williams PL, Smith TJ, Christiani DC. Association of heart rate variability with occupational and environmental exposure to particulate air pollution. Circulation. 2001;104:986–991. doi: 10.1161/hc3401.095038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GJ, Magid NM, Myers G, Barnett PS, Schaad JW, Weiss JS, et al. Heart rate variability and sudden death secondary to coronary artery disease during ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:86–89. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90990-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SK, O'Neill MS, Vokonas PS, Sparrow D, Schwartz J. Effects of Air Pollution on Heart Rate Variability: The VA Normative Aging Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:304–309. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn State College of Medicine, Department of Public Health Sciences . Personal DataRam (pDR) Operation Manual for Air Pollution and Cardiac Risk (APACR) Study. Hershey, PA: 2008a. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Penn State College of Medicine, Department of Public Health Sciences . Holter ECG Data Collection and Analysis Procedures for Air Pollution and Cardiac Risk (APACR) Study. Hershey, PA: 2008b. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Penn State College of Medicine, Department of Public Health Sciences . Super ECG Software Standard Operational Procedures for Air Pollution and Cardiac Risk (APACR) Study. Hershey, PA: 2008c. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Liu E, Verrier RL, Schwartz J, Gold DR, Mittleman M, et al. Air pollution and incidence of cardiac arrhythmia. Epidemiology. 2000;11(1):11–17. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200001000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Dockery DW, Muller JE, Mittleman MA. Increased particulate air pollution and the triggering of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001a;2001103:2810–2815. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.23.2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Fröhlich M, Döring A, Immervoll T, Wichmann HE, Hutchinson WL, et al. Particulate air pollution is associated with an acute phase response in men: results from the MONICA: Augsburg Study. Eur Heart J. 2001b;200122:1198–1204. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA, 3rd., Burnett RT, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D, Ito K, et al. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA. 2002;287:1132–1141. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea A, Zufall M, Williams R, Reed C, Sheldon L. The influence of human activity patterns on personal PM exposure: a comparative analysis of filter-based and continuous particle measurements. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2001;51:1271–1279. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2001.10464351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed CH, Rea A, Zufall M, Burke J, Williams R, Suggs J, Walsh D, Kwok R, Sheldon L. Use of a continuous nephelometer to measure personal exposure to particles during the U.S. EPA Baltimore and Fresno panel studies. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2000 Jul;50(7):1125–1132. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2000.10464150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP, Hennekens CH. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(14):973–979. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704033361401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J. Air pollution and blood markers of cardiovascular risk. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109(Suppl 3):405–409. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen M, Daneshvar B, Hansen M, Dragsted LO, Hertel O, Knudsen L, et al. Personal PM2.5 Exposure and Markers of Oxidative Stress in Blood. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:161–166. doi: 10.1289/ehp.111-1241344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Wang A, Jin X, Natanzon A, Duquaine D, Brook RD, et al. Long-term air pollution exposure and acceleration of atherosclerosis and vascular inflammation in an animal model. JAMA. 2005;294(23):3003–3010. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.23.3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwa T, Hogg JC, Quinlan KB, Ohgami A, Vincent R, van Eeden SF. Particulate air pollution induces progression of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(6):935–942. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01715-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology: Heart Rate Variability -- Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation. 1996;93:1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji H, Venditti FJ, Jr, Manders ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, Feldman CL, et al. Reduced heart rate variability and mortality risk in an elderly cohort: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1994;90:878–883. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.2.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace L, Williams R, Rea A, Croghan C. Continuous week long measurements of personal exposures and indoor concentrations of fine particles for 37 health-impaired North Carolina residents for up to four seasons. Atmospheric Environment. 2005;40:399–414. [Google Scholar]

- Whitsel EA, Quibrera PM, Christ SL, Liao D, Prineas RJ, Anderson GL, et al. Heart rate variability, ambient particulate matter air pollution, and glucose homeostasis: the environmental epidemiology of arrhythmogenesis in the women's health initiative. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(6):693–703. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R, Rea A, Vette A, Croghan C, Whitaker D, Wilson H, et al. The design and field implementation of the Detroit Exposure and Aerosol Research Study (DEARS). J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2009 Nov;19(7):643–59. doi: 10.1038/jes.2008.61. Epub 2008 Oct 22. doi: 10.1038/jes.2008.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue W, Schneider A, Stölzel M, Rückerl R, Cyrys J, Pan X, et al. Ambient source-specific particles are associated with prolonged repolarization and increased levels of inflammation in male coronary artery disease patients. Mutat Res. 2007;621(1-2):50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZM, Whitsel EA, Quibrera PM, Smith RL, Liao D, Anderson GL, et al. Ambient fine particulate matter exposure and myocardial ischemia in the Environmental Epidemiology of Arrhythmogenesis in the Women's Health Initiative (EEAWHI) study. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(5):751–756. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]