Summary

The insulin-regulated trafficking of the facilitative glucose transporter GLUT4 in human fat and muscle cells and the nitrogen-regulated trafficking of the general amino acid permease Gap1 in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae share several common features: Both Gap1 and GLUT4 are nutrient transporters that are mobilised to the cell surface from an intracellular store in response to an environmental cue; both are polytopic membrane proteins harbouring amino acid targeting motifs in their C-terminal tails that are required for their regulated trafficking; ubiquitylation of both Gap1 and GLUT4 plays an important role in their regulated trafficking, as do the ubiquitin-binding GGA (Golgi-localised, γ-ear-containing, ARF-binding) adaptor proteins. Here, we find that when expressed heterologously in yeast, human GLUT4 is subject to nitrogen-regulated trafficking in an ubiquitin-dependent manner similar to Gap1. In addition, by expressing a GLUT4/Gap1 chimeric protein in adipocytes we show that the carboxy-tail of Gap1 directs intracellular sequestration and insulin-regulated trafficking in adipocytes. These findings demonstrate that the trafficking signals and their cognate molecular regulatory machinery that mediate regulated exocytosis of membrane proteins are conserved across evolution.

Key words: Endosomes, Protein sorting, Regulated traffic

Introduction

Compartmentalisation into discrete, membrane-bound organelles enables eukaryotic cells to use regulated membrane trafficking to respond to changing environmental conditions in a timely manner. For example, rapid mobilisation of the facilitative glucose transporter GLUT4 from an intracellular store to the plasma membrane of fat and muscle cells in response to insulin increases the rate of glucose transport into these cells, lowering plasma glucose levels, and thus plays an important role in regulating whole body glucose homeostasis (Abel et al., 1996; Bryant et al., 2002). Amino-acid transporters in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae are also subject to regulated trafficking (Magasanik and Kaiser, 2002). Trafficking of the general amino-acid transporter Gap1 is regulated by nitrogen availability (Roberg et al., 1997a). Gap1 is retained intracellularly in yeast grown on nitrogen-rich media, but under low nitrogen conditions is delivered to the cell surface where it scavenges amino acids from the extracellular media.

There are a number of similarities between Gap1p and GLUT4 trafficking giving rise to the notion that elements of these pathways are conserved across evolution. GLUT4 and Gap1 are nutrient transporters with 12 predicted transmembrane domains (Birnbaum, 1989; James et al., 1989; Jauniaux and Grenson, 1990). They both harbour amino acid targeting motifs in their cytosolic C termini that are required for their regulated trafficking (Hein and André, 1997; Lalioti et al., 2001; Verhey et al., 1993). In the absence of signal to trigger delivery to the cell surface, both GLUT4 and Gap1 are retained intracellulary, with the majority of both localising to the trans Golgi network (TGN) (Bryant et al., 2002; Roberg et al., 1997b). This supports current working models for the trafficking itinerary of GLUT4 in insulin-sensitive cells that suggest GLUT4 continuously cycles through the TGN/endosomal system as part of its intracellular retention mechanism (Dugani and Klip, 2005; Stöckli et al., 2011). Such cycling is reminiscent of how proteins such as Kex2 and Ste13 achieve steady state localisation to the yeast TGN (Brickner and Fuller, 1997; Bryant and Stevens, 1997). We recently reported that human GLUT4, expressed heterologously in yeast, colocalises with Kex2 (Lamb et al., 2010). Like endogenous yeast TGN proteins, this GLUT4 becomes trapped in the exaggerated endosomal compartment that accumulates in class E vps mutants (Lamb et al., 2010), an observation that has also been reported for Gap1 in cells grown on a rich source of nitrogen (Nikko et al., 2003). The GGA (Golgi-localised, γ-ear-containing, ARF-binding) family of clathrin adaptor proteins recognise ubiquitinated proteins and facilitate their transport from the TGN into the endosomal system in both yeast and mammalian cells (Pelham, 2004). Ubiquitination is essential for the regulated trafficking of both GLUT4 and Gap1 (Lamb et al., 2010; Soetens et al., 2001), and both processes also require GGA proteins (Li and Kandror, 2005; Scott et al., 2004; Watson et al., 2004).

Given the high level of evolutionary conservation of molecular machinery involved in membrane traffic (Ferro-Novick and Jahn, 1994) and the above similarities in the regulated trafficking pathways of Gap1 and GLUT4 in yeast and mammalian cells, we set out to test the hypothesis that the machinery involved in regulated trafficking of GLUT4 in insulin-sensitive cells has been evolutionarily conserved from yeast. In support of this, we found that when expressed in yeast, GLUT4 is trafficked in a nitrogen-regulated manner analogous to Gap1. Furthermore, we found that a chimeric protein with the cytosolic C-terminal tail of GLUT4 replaced with the analogous region of Gap1 traffics to the cell surface of adipocytes in response to insulin stimulation, in contrast to a version of GLUT4 with this region mutated. These findings demonstrate that the molecular machinery responsible for regulating Gap1 traffic in yeast recognises sequences in GLUT4, and that the machinery in adipocytes that recognises sequences in the C-terminal tail of GLUT4 also recognises sequences in Gap1. These studies suggest evolutionary conservation of the regulated trafficking of GLUT4 and Gap1 in yeast and mammalian cells.

Results

GLUT4 expressed in yeast is subject to nitrogen-regulated trafficking

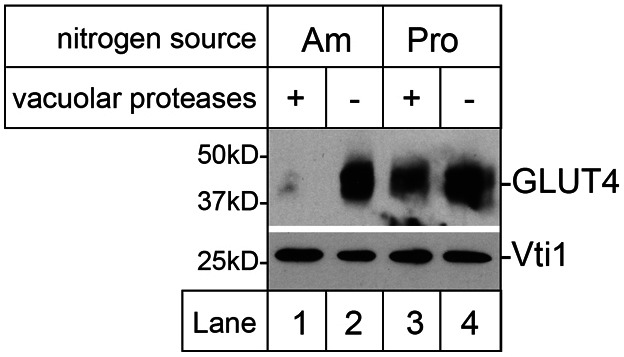

We have previously reported that when expressed heterologously in yeast, human GLUT4 localises to the TGN by cycling through the proteolytically active endosomal system (Lamb et al., 2010). Building on this, and other similarities between trafficking of GLUT4 and Gap1 in insulin-sensitive cells and yeast respectively (Bryant et al., 2002; Roberg et al., 1997b), we investigated whether GLUT4 is subject to nitrogen-regulated trafficking when produced in yeast. Fig. 1 shows that GLUT4 can be diverted away from the yeast endosomal system by moving cells to a less favourable source of nitrogen. GLUT4 expressed from the yeast CUP1 promoter is readily detectable in yeast cells devoid of vacuolar protease activity provided with a favourable source of nitrogen (ammonium), but not in cells containing active vacuolar proteases (Fig. 1, compare lanes 1 and 2), reflecting its continual cycling through the proteolytically active endosomal system under these conditions (Lamb et al., 2010). In contrast to the low levels found in yeast containing active vacuolar proteases grown on media containing a rich source of nitrogen (ammonium), GLUT4 was present at much higher levels in the same cells provided with a poor source of nitrogen (proline; Fig. 1, compare lanes 1 and 3). These data indicate that, like Gap1, GLUT4 is trafficked away from the proteolytically-active endosomal system in response to nitrogen-limiting conditions when expressed in yeast.

Fig. 1.

Heterologously expressed GLUT4 traffics to the yeast endosomal system in a nitrogen-responsive manner. Yeast containing (+) or lacking (−) active vacuolar proteases (RPY10 and SF838-9D) and producing human GLUT4 (from pRM2) were grown in media containing ammonium sulfate (Am) or proline (Pro) as the sole nitrogen source. Lysates of these cells were immunoblotted for GLUT4 and Vti1 (loading control).

Ubiquitination of GLUT4 is necessary and sufficient for delivery to the yeast endosomal system

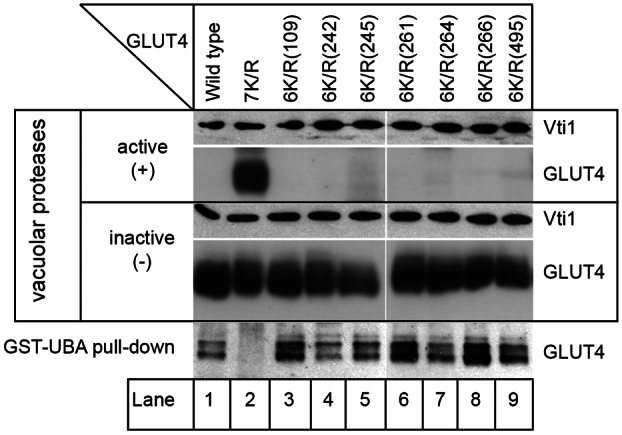

Nitrogen-regulated trafficking of Gap1 is controlled by ubiquitination of the transporter (Helliwell et al., 2001; Soetens et al., 2001). Under nitrogen-rich conditions Gap1 is ubiquitinated by Rsp5 and sorted into the endosomal system (Helliwell et al., 2001). In contrast, no ubiquitin is added to Gap1 when cells are provided with a poor nitrogen source and the transporter is trafficked away from the endosomal system to the plasma membrane (Helliwell et al., 2001; Soetens et al., 2001). We have previously shown that, in contrast to its wild-type counterpart, a non-ubiquitinated version of GLUT4 (with all seven cytosolically disposed lysines mutated to arginines; G4-7K/R) is not trafficked to the proteolytically active endosomal system in yeast provided with a rich source of nitrogen, indicating a requirement for ubiquitination in this process (Lamb et al., 2010) (Fig. 2, compare lanes 1 and 2). To address concerns that the defective trafficking of G4-7K/R is due to the multiple mutations it carries, rather than loss of ubiquitination, we took advantage of the finding that reintroduction of a single lysine into G4-7K/R is sufficient to restore its ubiquitination status (Lamb et al., 2010). Fig. 2 shows that reintroduction of any one of lysine 109, 242, 245, 261, 264, 266 or 495 restores delivery to the proteolytically active endosomal system of yeast grown on a rich nitrogen source. Only the ubiquitin-resistant G4-7K/R (lane 2) can be detected in cells containing active vacuolar proteases in contrast to wild-type GLUT4 (lane 1) and versions carrying a single cytosolic lysine (lanes 3–9, G4-6K/Rs). It is important to note that all of these versions of GLUT4 are expressed in yeast as demonstrated by immunoblot analysis of yeast lacking active vacuolar proteases grown on a rich source of nitrogen, indicating that their low levels in cells containing active vacuolar proteases grown under the same conditions reflects their delivery into the proteolytically active endosomal system. Lysates prepared from proteolytically inactive cells were also used to demonstrate that, as observed in adipocytes (Lamb et al., 2010), the G4-6K/R versions of GLUT4, carrying any one of the lysines listed above, all bind to a ubiquitin-binding UBA domain, in contrast to the ubiquitin-resistant G4-7K/R (Fig. 2, bottom panel). Collectively, the data presented thus far demonstrate that ubiquitination is required to traffic GLUT4 into the yeast endosomal system in a nitrogen-regulated manner.

Fig. 2.

Ubiquitination is required for trafficking of GLUT4 to the yeast endosomal system. Yeast containing (+) or lacking (−) active vacuolar proteases (RPY10 and SF838-9D) and producing wild-type GLUT4 (from pRM2), the ubiquitin-resistant 7K/R version (from pRM3) or a version of the same with one of the seven lysines (indicated) mutated back to lysine (6K/R; from pRM17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 or 23 as described in Table 1) were provided with ammonium sulfate as a nitrogen source. Lysates from these cells were immunoblotted for GLUT4 and Vti1 (loading control). The ubiquitination status of the versions of GLUT4 detected in cells lacking vacuolar proteases (grown on ammonium sulfate) was assessed by their ability to bind a GST-fusion protein harbouring a ubiquitin-binding UBA domain as described (Lamb et al., 2010). Note that none of the versions of GLUT4 used here bound a non-ubiquitin binding mutant version of the GST-UBA fusion protein (not shown), indicating that their binding to the GST-UBA is due to ubiquitination (Lamb et al., 2010).

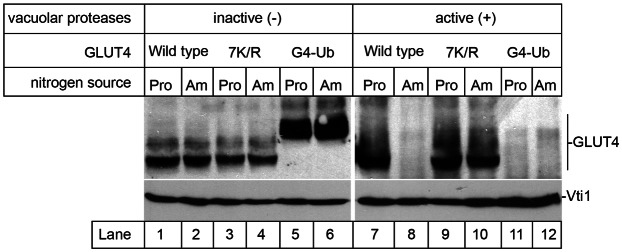

To ask whether ubiquitination is sufficient to sort GLUT4 into the yeast endosomal system, we adopted a strategy often used to create constitutively ubiquitinated versions of proteins (Piper and Luzio, 2007; Urbé, 2005), and expressed a chimeric gene encoding G4-7K/R fused to a single ubiquitin moiety at its C-terminus (G4-Ub). G4-Ub is readily detectable in yeast devoid of active vacuolar proteases, but not in cells that have active vacuolar proteases (Fig. 3, compare lanes 5 and 6 with lanes 11 and 12). Unlike wild-type GLUT4 which can be diverted away from the proteolytically active endosomal system by supplying cells with a less favourable source of nitrogen (proline; Fig. 1; Fig. 3, lanes 7 and 8), levels of G4-Ub can not be elevated in cells containing active vacuolar proteases in this manner (Fig. 3, lanes 11 and 12). These data indicate that G4-Ub is delivered to the proteolytically-active endosomal system even under nitrogen-poor conditions, demonstrating that ubiquitination of GLUT4 is sufficient for its endosomal delivery in yeast.

Fig. 3.

Ubiquitin serves as a signal to traffic GLUT4 into the endosomal system. Yeast containing (+) or lacking (−) active vacuolar proteases (RPY10 and SF838-9D) and producing various versions of GLUT4 [wild-type, non-ubiquitinated 7K/R, or an in-frame GLUT4-ubiquitin fusion protein (G4-Ub) as indicated: from pCAL4, pCAL5 or pRM24] were grown in media containing ammonium sulfate (Am) or proline (Pro) as sole nitrogen source. Lysates from these cells were immunoblotted for GLUT4 and Vti1 (loading control).

Abrogation of GLUT4 insulin-sensitivity by mutation of its C-terminal cytosolic tail can be restored by transplantation of the analogous region of the yeast protein Gap1

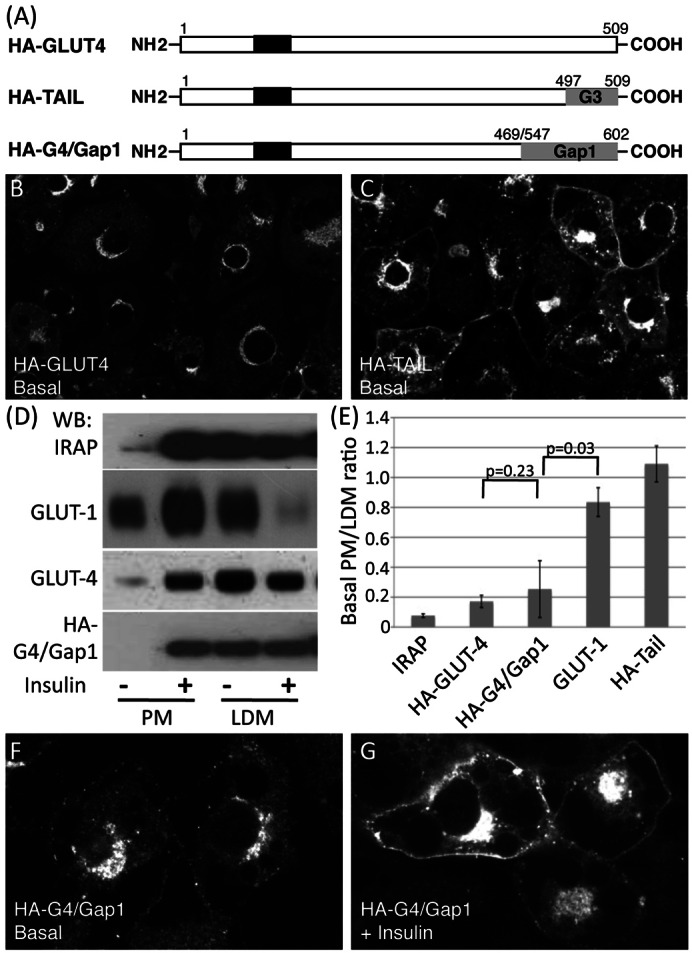

The data presented so far indicate a degree of evolutionary conservation of molecular events required for regulated trafficking of Gap1 and GLUT4 in yeast and insulin-sensitive cells respectively, in that the yeast machinery responsible for regulating Gap1 traffic recognise signals present in GLUT4. To investigate whether insulin-sensitive cells recognise signals present in Gap1 we created a chimeric protein in which the C-terminal cytosolic domain of an HA-tagged version of GLUT4 (residues 470–509; please see supplementary material Table S1) was replaced with the analogous region of the yeast protein Gap1 (residues 547–602; please see supplementary material Table S1) to create HA-G4/Gap1 (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

The C-terminal cytosolic domain of Gap1 contains information sufficient to sequester GLUT4 in an insulin-sensitive intracellular store in adipocytes. (A) Representation of proteins used. HA-tagged human GLUT4 (Quon et al., 1994) was used as a starting point for construction of the chimeric proteins HA-TAIL [in which the 12 C-terminal residues of GLUT4 are replaced with the corresponding residues from GLUT3 (Shewan et al., 2000)] and HA-G4/Gap1chimeric (with the entire cytosolic C-terminal tail of HA-GLUT-4 replaced with the corresponding region of Gap1, as detailed in Materials and Methods). (B,C) Adipocytes expressing HA-GLUT4 (B) or HA-TAIL (C) were immunolabelled with antibodies specific for the HA-epitope to visualise the localisation of these proteins as steady state using confocal microscopy. Representative confocal images are shown. Note the presence of HA-TAIL at the cell surface in unstimulated cells in contrast to the intracellular sequestration of HA-GLUT4 under the same conditions, in agreement with previous studies (Shewan et al., 2000). (D) 3T3-L1 adipocytes expressing HA-G4/Gap1 treated with 1 µM insulin (+) or not (−) for 15 minutes at 37°C were fractionated by differential centrifugation into fractions enriched in plasma membrane (PM) or the intracellular GLUT4 compartment (LDM). Aliquots of each fraction (10 µg protein) were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for IRAP, GLUT4 and the HA-epitope (for the HA-G4/Gap1 chimera). GLUT1 distribution in HA-GLUT4 cells is presented for comparison of the subcellular fractionation profile of an endogenous endosomal protein. (E) 3T3-L1 adipocytes expressing HA-GLUT4, HA-TAIL or HA-G4/Gap1 were subjected to insulin stimulation, differential centrifugation and western blotting as described above. The PM/LDM ratio provides an index of the intracellular sequestration of transporters in the absence of insulin (Marsh et al., 1998; Shewan et al., 2000). PM/LDM ratios were calculated for each of the proteins shown from multiple (≥3) independent fractionation experiments. Results are presented as means ± s.e.m. Data were analysed using two-tailed Students t-tests assuming unequal variance where these tests were appropriate. (F,G) Adipocytes expressing HA-G4/Gap1 were treated with (G, + Insulin) or without (F, Basal) 1 µM insulin at 37°C for 15 minutes prior to immunolabelling with antibodies specific for the HA-epitope to visualise the localisation of these proteins using confocal microscopy. Representative confocal images are shown. Note the steady state intracellular accumulation of HA-G4/Gap1 under basal conditions, and translocation to the cell surface upon insulin stimulation.

The C-terminal tail of GLUT4 contains targeting information required for intracellular retention of the transporter in insulin-sensitive cells. Replacement of the C-terminal 12 amino acids of GLUT4 with the C-terminal 12 residues of GLUT3 to create HA-TAIL (Fig. 4A) results in loss of intracellular sequestration in adipoctyes in the absence of insulin [(Shewan et al., 2000) and Fig. 4]. Whereas wild-type HA-tagged GLUT4 displays the same perinuclear staining pattern seen for endogenous GLUT4 in adipocytes, with little detectable at the cell surface (Fig. 4B), HA-TAIL was readily observed at the cell surface (Fig. 4C,E) reflecting its loss of intracellular retention (Shewan et al., 2000). Intracellular sequestration of wild-type GLUT4 in basal cells is also reflected by its low abundance in plasma membrane (PM) fractions prepared from adipocytes in the absence of insulin (Fig. 4D). This is a feature of GLUT4 that sets it apart from other transporters such as GLUT1. This is an important point since, while endosomal proteins, including GLUT1 and the transferrin receptor, are responsive to insulin stimulation (Livingstone et al., 1996; Piper et al., 1991), the key difference between these and proteins that traffic to the specialised insulin-responsive compartment (GLUT4 and IRAP) is that endosomal proteins are not sequestered intracellularly, but rather traffic constitutively via the cell surface. This difference is clearly demonstrated by the presence of GLUT1 in the basal-PM membrane fraction (Fig. 4D). The low-density microsomal membrane (LDM) fraction isolated from adipocytes is enriched for the intracellular storage pool from which GLUT4 is mobilised to the cell surface in response to insulin. The PM/LDM ratio provides a quantitative index of the extent of intracellular sequestration of endogenous and exogenous proteins in insulin-sensitive cells (Shewan et al., 2000) (Fig. 4E). In agreement with our previous studies (Shewan et al., 2000), and reflecting its intracellular sequestration, HA-GLUT4 exhibits a low PM/LDM ratio under basal conditions (0.171±0.04, n = 4), comparable to endogenous GLUT4 and IRAP. In contrast, we have previously reported that HA-TAIL has a much higher PM/LDM ratio (1.09±0.12, n = 3) indicative of inefficient intracellular sequestration in unstimulated cells. The sequestration profile of HA-TAIL more closely resembles the profile of endosomal transporter proteins such as GLUT1 rather than that of proteins such as GLUT4 and IRAP that are sequestered intracellularly in an insulin-responsive store (Shewan et al., 2000) (Fig. 4D, 4E). To determine whether the C-terminal tail of Gap1 could direct intracellular sequestration and insulin responsiveness in adipocytes the subcellular fractionation profile of HA-G4/Gap1 was examined in both basal and insulin-stimulated cells (Fig. 4D). Like the insulin-responsive proteins, GLUT4 and IRAP, HA-G4/Gap1 was largely absent from the plasma membrane fraction under basal conditions and its PM/LDM ratio was similar to that of GLUT4 and IRAP (Fig. 4E). This demonstrates that the Gap1 C-terminal sequences used here contain information sufficient to bestow intracellular sequestration in adipocytes.

Furthermore, insulin stimulation elicited robust translocation of HA-G4/Gap1 to the PM fraction similar to that observed for the endogenous insulin-responsive proteins, GLUT4 and IRAP (Fig. 4D). These fractionation studies show that the Gap1 C-terminal tail contains information to both sequester the protein and to direct the chimera into an insulin-responsive compartment.

This contention is supported by immunofluorescence studies where HA-G4/Gap1 displayed a perinuclear staining pattern reminiscent of that seen for wild-type HA-GLUT4 with little, if any, present at the cell surface under basal conditions (Fig. 4F). Treatment of these adipocytes with insulin elicited a robust translocation of HA-G4/Gap1 to the plasma membrane (Fig. 4G). Collectively, these studies reveal that the cytosolic C-terminal domain of Gap1 contains information to direct sorting into the intracellular, insulin-responsive compartment of adipocytes.

Discussion

Trafficking of certain proteins between endosomes and the TGN plays a key role in intracellular retention and can be regulated to alter trafficking pathways in response to external stimuli (Bryant et al., 2002). We have now shown that this is highly conserved across evolution and appears to be encoded via ubiquitination of cargo which likely facilitates recognition by the GGA adaptor machinery that facilitates sorting from the TGN into the endosomal system (Lamb et al., 2010; Li and Kandror, 2005; Scott et al., 2004; Soetens et al., 2001; Watson et al., 2004).

While our data highlight remarkable similarities between regulated trafficking of GLUT4 and Gap1 in yeast and adipocytes, it is also clear from our studies that additional, unique processes also operate in the two systems. In the case of Gap1 ubiquitination in response to nutrient deprivation diverts its trafficking from the TGN away from the plasma membrane into the endosomal system (Helliwell et al., 2001; Soetens et al., 2001). On the other hand, ubiquitination of GLUT4 occurs constitutively and insulin, which controls cell surface expression of GLUT4, does not appear to regulate GLUT4 ubiquitination (Lamb et al., 2010). In the case of GLUT4, rather than providing a mechanism by which trafficking can be regulated directly, ubiquitination is required to deliver GLUT4 into the insulin-sensitive store from where it can be mobilised to the cell surface in response to insulin (Lamb et al., 2010). Thus, although evolutionarily conserved molecular machinery is used in the regulated trafficking of both GLUT4 and Gap1 the stage at which these processes are regulated by external stimuli differs.

Despite the above noted differences in the regulated trafficking of GLUT4 and Gap1, the conservation of sorting information and molecular machinery used by the two processes gives important insight into how GLUT4 is sorted into its insulin-sensitive store in adipocytes. We have previously shown an important role for an acidic cluster motif, located in the C-terminal tail of GLUT4 adjacent to a dileucine motif, in intracellular sequestration of the transporter in an insulin-sensitive store in adipoctyes (Shewan et al., 2000). We now find that this motif is also required to direct GLUT4 to the proteolytically active endosomal system in yeast (supplementary material Fig. S2). Similar acidic motifs are present in the cytosolic tails of other proteins that are sequestered in the endosomal system, including the proprotein convertase PC6B as well as other insulin-responsive proteins such as IRAP (Shewan et al., 2000). Gap1 also harbours such a motif in its C-terminal cytosolic tail, contained within the region used in construction of our HA-G4/Gap1 (supplementary material Fig. S1). Our observation that this portion of Gap1 contains information sufficient to direct sorting into an insulin-sensitive store in adipocytes taken in conjunction with our observation that when expressed in yeast, GLUT4 is sorted into the endosomal system in a ubiquitin-dependent manner indicates that ubiquitin-dependent sorting into the endosomal system is a key step in sorting of GLUT4 into its insulin-sensitive store in adipocytes.

These studies raise several important questions concerning the role of ubiquitination in sorting GLUT4 into its insulin-sensitive store. Perhaps the most obvious of these is how ubiquitinated GLUT4 escapes lysosomal degradation, the canonical fate of ubiquitinated proteins sorted from the TGN in a GGA-dependent manner (Piper and Luzio, 2007). Our finding that fusing a ubiquitin moiety in-frame to the C-terminus of GLUT4 results in its constitutive delivery to the proteolytically active endosomal system, regardless of nitrogen source, indicates that ubiquination is sufficient to act as a signal for this trafficking step. Our attempts to express the same construct in mammalian cells resulted in an extremely short lived protein, supporting our previous speculation (Lamb et al., 2010) that GLUT4 may be rescued from lysosomal delivery by a deubiquitinating process. Such a role for deubiquitination in routing cargo away from the lysosome has been observed for other receptors including the epidermal growth factor receptor (Clague and Urbé, 2006), the Drosophila Wnt receptor Frizzled (Mukai et al., 2010) and the β2-adrenergic receptor (Berthouze et al., 2009). Studies are currently underway in our laboratory to investigate this possibility.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies against GLUT4, GLUT1 and Vti1 have been described elsewhere (Coe et al., 1999; James et al., 1989; Piper et al., 1991). Antibodies against IRAP were from Paul Pilch (Boston University). Anti-HA (16B12) antibodies were from Berkeley Antibody Co., Inc., Richmond, CA.

Yeast [SF838-9D; MATa ura3-52 leu2-3, 112 his4-519 ade6 gal2 pep4-3 (Rothman and Stevens, 1986), or the congenic PEP4 strain RPY10 (Piper et al., 1994)] harbouring the indicated plasmids were grown in minimal media [0.67% Difco yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and ammonium sulfate (Difco Laboratories Inc., Detroit, MI, USA), 2% glucose, and either proline (0.1%) or ammonium sulfate (0.5%) as a nitrogen source as indicated (all percentages are w/v)]. Cells contained low-copy plasmids to cover auxotrophic requirements not covered by plasmids already present.

Plasmids

Plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. pRM17–23, each encoding G4-7K/R (Lamb et al., 2010) with a different single lysine residue mutated back to arginine (as described in the table) were constructed from pRM3 (Lamb et al., 2010) using site directed mutagenesis. pRM24 encoding a G4-7K/R-HA-tagged-ubiquitin fusion was created by using PCR to amplify HA-tagged ubiquitin from pRM1 (Lamb et al., 2010) flanked by sequences homologous to the 3′ end of the G4-7K/R ORF and the proximal end of the PHO8 3′UTR contained within pRM3 (Lamb et al., 2010). Homologous recombination was used to create the fusion by repairing a version of pRM3 (Lamb et al., 2010) linearised at an SphI site that had been introduced (by site directed mutagenesis) in place of the G4-7K/R STOP codon. pCAL4 and pCAL5 were constructed by amplification of the HA-tagged wild-type (for pCAL4) or the ubiquitin-resistant G4-7K/R (for pCAL5) ORFs flanked by sequences homologous to the 3′ end of the CUP1 promoter and the 5′ end of the PHO8 3′ UTR using PCR. These PCR products were used to repair gapped pNB701 as described previously (Struthers et al., 2009). pHA-G4/Gap1, the retroviral expression vector encoding HA-tagged human GLUT4 with the entire C-terminal cytosolic tail (residues 470–509; please see supplementary material Table S1) replaced with the analogous region of the yeast protein Gap1 (residues 547–602; please see supplementary material Table S1) was constructed using SOEing PCR to generate a GLUT4/GAP1 chimeric ORF as follows. First round PCR was performed with 5′-ctaagagtgcctcacaagatctataag-3′ and 5′-cgaattcttaacaccagaaattccag-3′ using GAP1, contained within a preparation of S. cerevisiae genomic DNA, as template; second round PCR utilised the gel purified product of first round PCR reaction and 5′-atcgtggccatatttggc-3′ with pHA-GLUT4 (Shewan et al., 2000) as template. The resultant PCR product was sequenced prior to sub-cloning as an Nco1-EcoR1 fragment into pHA-GLUT4 that had been gapped with the same restriction endonucleases to generate pHA-G4/Gap1.

Table 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Reference |

| pRM2 | Yeast expression plasmid (CEN, URA3) encoding human GLUT4 from the CUP1 promoter | (Lamb et al., 2010) |

| pRM3 | Yeast expression plasmid (CEN, URA3) encoding human GLUT4 with lysines 109, 242, 245, 261, 264, 266, 495 mutated to arginine residues (G4-7K/R) from the CUP1 promoter | (Lamb et al., 2010) |

| pRM17 | Yeast expression plasmid encoding human GLUT4 with a single cytosolic lysine at position 242 from the CUP1 promoter (derived from pRM3) | This study |

| pRM18 | Yeast expression plasmid encoding human GLUT4 with a single cytosolic lysine at position 261 from the CUP1 promoter (derived from pRM3) | This study |

| pRM19 | Yeast expression plasmid encoding human GLUT4 with a single cytosolic lysine at position 109 from the CUP1 promoter (derived from pRM3) | This study |

| pRM20 | Yeast expression plasmid encoding human GLUT4 with a single cytosolic lysine at position 245 from the CUP1 promoter (derived from pRM3) | This study |

| pRM21 | Yeast expression plasmid encoding human GLUT4 with a single cytosolic lysine at position 264 from the CUP1 promoter (derived from pRM3) | This study |

| pRM22 | Yeast expression plasmid encoding human GLUT4 with a single cytosolic lysine at position 266 from the CUP1 promoter (derived from pRM3) | This study |

| pRM23 | Yeast expression plasmid encoding human GLUT4 with a single cytosolic lysine at position 495 from the CUP1 promoter (derived from pRM3) | This study |

| pRM24 | Yeast expression plasmid (CEN, URA3) encoding G4-7K/R carrying an HA-tag fused in-frame to ubiquitin from the CUP1 promoter | This study |

| pCAL4 | Yeast expression plasmid (CEN, URA3) encoding HA-tagged human GLUT4 from the CUP1 promoter | This study |

| pCAL5 | Yeast expression plasmid (CEN, URA3) encoding HA-tagged G4-7K/R from the CUP1 promoter | This study |

| pHA-GLUT4 | Retroviral expression plasmid encoding HA-tagged human GLUT4. | (Shewan et al., 2000) |

| pHA-TAIL | Retroviral expression plasmid encoding HA-tagged human GLUT4 with the C-terminal 12 amino acid residues replaced with the corresponding sequence from human GLUT3. | (Shewan et al., 2000) |

| pHA-G4/Gap1 | Retroviral expression plasmid encoding HA-tagged human GLUT4 with the entire C-terminal cytosolic tail (residues 470–509) replaced with the analogous region of the yeast protein Gap1 (residues 547–602). | This study |

Expression of recombinant GLUT4 proteins in 3T3-L1 adipocytes

3T3-L1 murine fibroblasts obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) were infected with retroviral stocks generated from pHA-GLUT4, pHA-TAIL or pHA-G4/Gap1 prior to differentiation into adipocytes as described (Shewan et al., 2000).

Immunoblot analyses

Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE using 7.5% or 10% polyacrylamide resolving gels. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose or polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) for immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies and horse radish peroxidase linked secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence (both from Amersham). Chemiluminescent bands were quantified directly using a Lumi-Imager F1 (Boehringer Mannheim).

Preparation of yeast cell lysates

10 OD600 equivalents were harvested from growing cultures and vortexed in 200 µl Laemmli sample buffer (LSB) in the presence of glass beads (425–600 µm, acid washed). Glass beads were allowed to settle during a 10-minute incubation at 65°C and 10 µl of the lysate was loaded on a SDS-polyacrylamide gel.

Subcellular fractionation of adipocytes

Subcellular fractionation of 3T3-L1 adipocytes was used to generate low-density microsome (LDM) and plasma membrane (PM) enriched fractions (Shewan et al., 2000). The protocol used yields an additional two fractions, high-density microsomes (HDM) and mitochondria/nuclei (M/N), but here we focused on the PM and LDM fractions as the ratio of proteins contained within these provides a well-characterised index of intracellular retention in the insulin-sensitive GLUT4-enriched store of adipocytes (Shewan et al., 2000).

Ubiquitin-binding UBA-GST-fusion pull downs

The ability of various mutant versions of GLUT4 to bind the UBA domain of Dsk2p (within GST-UBA) was compared to wild-type and the ubiquitin-resistant G4-7K/R to assess their ubiquitination status as described (Lamb et al., 2010).

Indirect immunofluorescence

Cells were processed for immunofluorescence as described (Shewan et al., 2003). Confocal sections were obtained using a 63×/1.4 Zeiss oil immersion objective fitted to a Zeiss Axiovert fluorescence microscope, equipped with a Bio-Rad MRC-600 laser confocal imaging system, or a 100×/1.4 Plan Apo oil immersion objective on a Nikkon Eclipse E600 fluorescence microscope, equipped with a Bio-Rad Radiance 2000 laser confocal imaging system.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Author contributions

This study was conceived by A.M.S., N.J.B. and D.E.J. who analysed data and wrote the manuscript. All authors except D.E.J. performed experiments.

Funding

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust [grant number 081933/Z/07/Z to N.J.B.] and a studentship [grant number 080395/Z/06/Z to C.A.L.]; and the University of Queensland Graduate School (scholarship to A.M.S., currently an NHMRC CJ Martin Fellow). N.J.B. is a Prize Fellow of the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine. Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.114371/-/DC1

References

- Abel E. D., Shepherd P. R., Kahn B. B. (1996). Glucose transporters and pathophysiological states. Diabetes Mellitus LeRoith D, Taylor S I, Olefsky J M, ed530–544Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven [Google Scholar]

- Berthouze M., Venkataramanan V., Li Y., Shenoy S. K. (2009). The deubiquitinases USP33 and USP20 coordinate beta2 adrenergic receptor recycling and resensitization. EMBO J. 28, 1684–1696 10.1038/emboj.2009.128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum M. J. (1989). Identification of a novel gene encoding an insulin-responsive glucose transporter protein. Cell 57, 305–315 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90968-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner J. H., Fuller R. S. (1997). SOI1 encodes a novel, conserved protein that promotes TGN-endosomal cycling of Kex2p and other membrane proteins by modulating the function of two TGN localization signals. J. Cell Biol. 139, 23–36 10.1083/jcb.139.1.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant N. J., Stevens T. H. (1997). Two separate signals act independently to localize a yeast late Golgi membrane protein through a combination of retrieval and retention. J. Cell Biol. 136, 287–297 10.1083/jcb.136.2.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant N. J., Govers R., James D. E. (2002). Regulated transport of the glucose transporter GLUT4. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 267–277 10.1038/nrm782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clague M. J., Urbé S. (2006). Endocytosis: the DUB version. Trends Cell Biol. 16, 551–559 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe J. G., Lim A. C., Xu J., Hong W. (1999). A role for Tlg1p in the transport of proteins within the Golgi apparatus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 2407–2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugani C. B., Klip A. (2005). Glucose transporter 4: cycling, compartments and controversies. EMBO Rep. 6, 1137–1142 10.1038/sj.embor.7400584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferro-Novick S., Jahn R. (1994). Vesicle fusion from yeast to man. Nature 370, 191–193 10.1038/370191a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein C., André B. (1997). A C-terminal di-leucine motif and nearby sequences are required for NH4(+)-induced inactivation and degradation of the general amino acid permease, Gap1p, of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 24, 607–616 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3771735.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell S. B., Losko S., Kaiser C. A. (2001). Components of a ubiquitin ligase complex specify polyubiquitination and intracellular trafficking of the general amino acid permease. J. Cell Biol. 153, 649–662 10.1083/jcb.153.4.649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James D. E., Strube M., Mueckler M. (1989). Molecular cloning and characterization of an insulin-regulatable glucose transporter. Nature 338, 83–87 10.1038/338083a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauniaux J. C., Grenson M. (1990). GAP1, the general amino acid permease gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleotide sequence, protein similarity with the other bakers yeast amino acid permeases, and nitrogen catabolite repression. Eur. J. Biochem. 190, 39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalioti V., Vergarajauregui S., Sandoval I. V. (2001). Targeting motifs in GLUT4 (review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 18, 257–264 10.1080/09687680110090780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb C. A., McCann R. K., Stöckli J., James D. E., Bryant N. J. (2010). Insulin-regulated trafficking of GLUT4 requires ubiquitination. Traffic 11, 1445–1454 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01113.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. V., Kandror K. V. (2005). Golgi-localized, gamma-ear-containing, Arf-binding protein adaptors mediate insulin-responsive trafficking of glucose transporter 4 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 2145–2153 10.1210/me.2005-0032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone C., James D. E., Rice J. E., Hanpeter D., Gould G. W. (1996). Compartment ablation analysis of the insulin-responsive glucose transporter (GLUT4) in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochem. J. 315, 487–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magasanik B., Kaiser C. A. (2002). Nitrogen regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 290, 1–18 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00558-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh B. J., Martin S., Melvin D. R., Martin L. B., Alm R. A., Gould G. W., James D. E. (1998). Mutational analysis of the carboxy-terminal phosphorylation site of GLUT-4 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 275, E412–E422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai A., Yamamoto-Hino M., Awano W., Watanabe W., Komada M., Goto S. (2010). Balanced ubiquitylation and deubiquitylation of Frizzled regulate cellular responsiveness to Wg/Wnt. EMBO J. 29, 2114–2125 10.1038/emboj.2010.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikko E., Marini A. M., André B. (2003). Permease recycling and ubiquitination status reveal a particular role for Bro1 in the multivesicular body pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 50732–50743 10.1074/jbc.M306953200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham H. R. (2004). Membrane traffic: GGAs sort ubiquitin. Curr. Biol. 14, R357–R359 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper R. C., Luzio J. P. (2007). Ubiquitin-dependent sorting of integral membrane proteins for degradation in lysosomes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 459–465 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper R. C., Hess L. J., James D. E. (1991). Differential sorting of two glucose transporters expressed in insulin-sensitive cells. Am. J. Physiol. 260, C570–C580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper R. C., Whitters E. A., Stevens T. H. (1994). Yeast Vps45p is a Sec1p-like protein required for the consumption of vacuole-targeted, post-Golgi transport vesicles. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 65, 305–318 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quon M. J., Guerre-Millo M., Zarnowski M. J., Butte A. J., Em M., Cushman S. W., Taylor S. I. (1994). Tyrosine kinase-deficient mutant human insulin receptors (Met1153–>Ile) overexpressed in transfected rat adipose cells fail to mediate translocation of epitope-tagged GLUT4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 5587–5591 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberg K. J., Bickel S., Rowley N., Kaiser C. A. (1997a). Control of amino acid permease sorting in the late secretory pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by SEC13, LST4, LST7 and LST8. Genetics 147, 1569–1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberg K. J., Rowley N., Kaiser C. A. (1997b). Physiological regulation of membrane protein sorting late in the secretory pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 137, 1469–1482 10.1083/jcb.137.7.1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman J. H., Stevens T. H. (1986). Protein sorting in yeast: mutants defective in vacuole biogenesis mislocalize vacuolar proteins into the late secretory pathway. Cell 47, 1041–1051 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90819-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott P. M., Bilodeau P. S., Zhdankina O., Winistorfer S. C., Hauglund M. J., Allaman M. M., Kearney W. R., Robertson A. D., Boman A. L., Piper R. C. (2004). GGA proteins bind ubiquitin to facilitate sorting at the trans-Golgi network. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 252–259 10.1038/ncb1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shewan A. M., Marsh B. J., Melvin D. R., Martin S., Gould G. W., James D. E. (2000). The cytosolic C-terminus of the glucose transporter GLUT4 contains an acidic cluster endosomal targeting motif distal to the dileucine signal. Biochem. J. 350, 99–107 10.1042/0264-6021:3500099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shewan A. M., van Dam E. M., Martin S., Luen T. B., Hong W., Bryant N. J., James D. E. (2003). GLUT4 recycles via a trans-Golgi network (TGN) subdomain enriched in Syntaxins 6 and 16 but not TGN38: involvement of an acidic targeting motif. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 973–986 10.1091/mbc.E02-06-0315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soetens O., De Craene J. O., Andre B. (2001). Ubiquitin is required for sorting to the vacuole of the yeast general amino acid permease, Gap1. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43949–43957 10.1074/jbc.M102945200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöckli J., Fazakerley D. J., James D. E. (2011). GLUT4 exocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 124, 4147–4159 10.1242/jcs.097063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struthers M. S., Shanks S. G., MacDonald C., Carpp L. N., Drozdowska A. M., Kioumourtzoglou D., Furgason M. L., Munson M., Bryant N. J. (2009). Functional homology of mammalian syntaxin 16 and yeast Tlg2p reveals a conserved regulatory mechanism. J. Cell Sci. 122, 2292–2299 10.1242/jcs.046441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbé S. (2005). Ubiquitin and endocytic protein sorting. Essays Biochem. 41, 81–98 10.1042/EB0410081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhey K. J., Hausdorff S. F., Birnbaum M. J. (1993). Identification of the carboxy terminus as important for the isoform-specific subcellular targeting of glucose transporter proteins. J. Cell Biol. 123, 137–147 10.1083/jcb.123.1.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson R. T., Khan A. H., Furukawa M., Hou J. C., Li L., Kanzaki M., Okada S., Kandror K. V., Pessin J. E. (2004). Entry of newly synthesized GLUT4 into the insulin-responsive storage compartment is GGA dependent. EMBO J. 23, 2059–2070 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.