Abstract

Virus infections usually begin in peripheral tissues and can invade the mammalian nervous system (NS), spreading into the peripheral (PNS) and more rarely the central nervous systems (CNS). The CNS is protected from most virus infections by effective immune responses and multi-layer barriers. However, some viruses enter the NS with high efficiency via the bloodstream or by directly infecting nerves that innervate peripheral tissues, resulting in debilitating direct and immune-mediated pathology. Most viruses in the NS are opportunistic or accidental pathogens, but a few, most notably the alpha herpesviruses and rabies virus, have evolved to enter the NS efficiently and exploit neuronal cell biology. Remarkably, the alpha herpesviruses can establish quiescent infections in the PNS, with rare but often fatal CNS pathology. Here we review how viruses gain access to and spread in the well-protected CNS, with particular emphasis on alpha herpesviruses, which establish and maintain persistent NS infections.

Introduction

Most acute and persistent viral infections begin in the periphery, often at epithelial or endothelial cell surfaces. Infection of cells at these sites usually induces a tissue-specific antiviral response that includes both a cell autonomous response (intrinsic immunity) and paracrine signaling from the infected cell to surrounding uninfected cells by secreted cytokines (innate immunity). This local inflammatory response usually contains the infection. After several days, the adaptive immune response may be activated and the infection cleared by the action of infection-specific antibodies and T cells (acquired immunity). Viral infections that escape local control at the site of primary infection can spread to other tissues where they can cause more serious problems due to robust virus replication or, overreacting innate immune response. This latter reaction is sometimes called a `cytokine storm` because both pro-inflammatory and antiinflammatory cytokines are elevated in the serum leading to vigorous systemic immune activity (Figure 1). Such a response in the brain is usually devastating and can lead to meningitis, encephalitis, meningoencephalitis or death.

Figure 1. Immune Control of Viral Infections.

Cellular pattern recognition receptors (PRR) recognize viral molecules after attachment and entry. This initial recognition starts a cell autonomous intrinsic defense involving increased synthesis of many antiviral proteins, and several cytokines, including type I interferons (IFN-α/β). If intrinsic defenses fail to stop virus relication, cytokines and infected cell death activate sentinel cells (e.g. dendritic cells, macrophages), which produce copious cytokines and present antigens to trigger T-cell mediated immunity. The innate immune response, which is activated quickly and robustly, also involves the actions of the complement system, natural killer cells (NK), neutrophils and other granulocytes. Over-reaction of this response causes immunopathology termed a “cytokine storm”. The adaptive, acquired immune response is slow, systemic, pathogen-specific, and leads to the induction of immunological memory. The cell-mediated “Th1” response involves the action of CD4+ T-helper cells and CD8+ Cytotoxic T-cells (CTL). CTLs are important to kill infected cells and to produce type II interferon (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α).The “Th2” humoral response involves CD4+ T-helper cells and antibody-producing B-cells. Most of the time, the clinical symptoms of virus infection (e.g. fever, pain, tissue damage) are caused by the inflammatory action of the innate and adaptive immune systems. Due to their mostly irreplacable nature, nervous system tissues rely predominantly on the intrinsic and innate immune responses, and avoid the extensive inflammation and cytotoxic effects of the adaptive immune response.

The capacity to invade the host nervous system (NS) appears to be a rather poor evolutionary path because of the potentially damaging and lethal nature of these infections. In most cases, acute infection of the central nervous system (CNS) has no apparent selective advantage for the host or the pathogen. These infections, when they occur, often represent a zoonotic infection: an incursion of a virus from its natural host into a "dead-end host", which has little chance to further disseminate the infection. Zoonotic virus infections are often minimally pathogenic in their natural hosts, but can be highly virulent and neuroinvasive in non-natural hosts. The virulence and lethality of zoonotic infections may result from the cytokine storm evoked after the primary infection. The 1918 influenza pandemic and more recent H5N1 (bird flu) outbreak in humans are good examples of this phenomenon [1]. Patients infected with H5N1 virus die, not because of robust virus replication, but because of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) triggered by the cytokine storm. Fatal infection by rabies virus (RABV), and the less known, but nonetheless devastating infections caused by West Nile virus (WNV) and Nipah virus also represent zoonotic infections. When these zoonotic RNA viruses infect fully differentiated neurons (in the brain and spinal cord), virus clearance by the immune system is a major challenge. Because CNS neurons in particular are irreplaceable, canonical T cell mediated cytolysis of these infected cells is not a favorable strategy. Thus, as understood by animal models, recovery from viral infection and the clearance of viral RNA require a slower process involving the actions of virus-specific antibodies and interferon gamma (IFNγ) secretion from T cells [2].

In contrast to the dangerous zoonotic CNS infections described above, some human-adapted viruses gain access to the CNS as a result of diminished host defenses that fail to limit peripheral infections (e.g. Epstein-Barr virus, human cytomegalovirus, JC virus). Others are the result of the iatrogenic introduction of the infection directly into the CNS, bypassing peripheral barriers (e.g. use of adenovirus or lentivirus vectors, or prions). Remarkably, many alpha herpesviruses efficiently enter the PNS of their natural hosts and establish a quiescent infection with little or no CNS pathogenesis. Their initial peripheral infection stimulates a well-controlled intrinsic and innate immune response as well as a long-lived adaptive immune response. The alpha herpesvirus genomes remain quiescent in PNS neurons for the life of their hosts, only occasionally reactivating to produce virions that can re-infect peripheral tissues and spread to other hosts. Perhaps the pro-survival, cytolysis-resistant nature of mature neurons facilitates establishment of such persistent and reactivatable infections.

In this review, after providing a general overview on how viruses gain access to the NS, we will focus on intra- and interneuronal virus trafficking and spread tactics and discuss how alpha herpesviruses establish persistent infections in the NS. We will finish by discussing our views on the control of virus invasion in the NS.

Entering the nervous system

While the PNS is relatively more accessible to peripheral infections because nerves are in direct contact with tissues of all types, the CNS proper has several layers of protection. Spread of infection from the blood to the cerebral spinal fluid and CNS cells is limited by the blood brain barrier (BBB). The BBB is mainly composed of endothelial cells, pericytes, astrocytes and the basement membrane (Figure 2D). Pericytes project finger-like processes to ensheath the capillary wall and coordinate the neurovascular functions of the BBB. The star shaped astrocytes (i.e. astroglia) are the major glial cell type in the CNS. The astrocyte endfeet projections ensheath the capillary, regulating BBB homeostasis and blood-flow. Brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMVECs) that line the CNS vasculature are connected by tight junctions not found in capillaries in other tissues. These junctions restrict the egress of bacteria, virus particles, and large protein molecules from the lumen of the blood vessel, while allowing the transport of metabolites, small hydrophobic proteins, and dissolved gasses in and out of the CNS. The basement membrane, a thick extracellular matrix, also surrounds these capillaries further limiting movement of pathogens. Perivascular macrophages (i.e. migroglia) residing between the endothelial and glial cells further provide immune surveillance in the CNS tissue. Virus infections that leave the periphery and find their way into the PNS or CNS do so either by direct infection of nerve endings in the tissues, or by infecting cells of the circulatory system that ultimately carry the infection through the BBB into the CNS (Table 1, Figure 2).

Figure 2. Virus entry routes into the CNS.

(A) Alpha herpesviruses (e.g. HSV-1, VZV, PRV) infect pseudounipolar sensory neurons of PNS ganglia. CNS spread is rare and requires anterograde axonal transport of progeny virions toward the spinal cord. (B) RABV and poliovirus spread via neuromuscular junctions (NMJ) from muscles into somatic motor neurons in the spinal cord. (C) Several viruses may infect receptor neurons in the nasal olfactory epithelium. Spread to the CNS requires anterograde axonal transport along the olfactory nerve into the brain. (D) Infiltration through the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The BBB is composed of brain microvascular endothelium cells (BMVEC) with specialized tight junctions, surrounding basement membrane, pericytes, astrocytes, and neurons. Infected leukocytes can traverse this barrier carrying virus into the brain parenchyma. (E) Alternatively, virus particles in the bloodstream can infect BMVECs, compromising the BBB.

Table 1.

Classification, properties and CNS entry routes of viruses that can cause nervous system infections.

| Genome | Virus Family | N/E | Specifics | Viruses | CNS Entry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dsDNA | Adenoviridae | N | MAV-1 | BBB; BMVECs | |

| Herpesviridae | E | Alphaherpesvirus | HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, PRV, BHV | sensory nerve endings, ORN | |

| Betaherpesvirus | HCMV | BBB; BMVECs | |||

| Gammaherpesvirus | EBV | BBB; BMVECs | |||

| Polyomaviridae | N | JCV | BBB; BMVECs | ||

| dsRNA | Reoviridae | N | mouse model | T3[1] | BBB, peripheral nerve? |

| (+)ssRNA | Coronaviridae | E | mouse model | MHV[2] | peripheral nerve, ORN |

| Flaviviridae | E | Hepacivirus | HCV* | BBB, BMVECs | |

| zoonotic | WNV*, JEV* | peripheral nerve, BBB, ORN, BMVECs | |||

| Picornaviridae | N | Enterovirus | Poliovirus*, EV71* | NMJs, BBB | |

| mouse model | TMEV[3] | BBB | |||

| Togaviridae | E | zoonotic | CHIKV* | ORN? | |

| mouse model | SINV[4] | ORN | |||

| (−)ssRNA | Arenaviridae | E | zoonotic | LCMV | BBB |

| Bornaviridae | E | zoonotic | BDV | ORN | |

| Bunyaviridae | E | zoonotic | LACV | ORN, BBB? | |

| Orthomyxoviridae | E | zoonotic | Influenza A* | peripheral nerve, ORN | |

| Paramyxoviridae | E | Morbilivirus | MV | BBB | |

| Rubulavirus | MuV | BBB | |||

| Henipavirus (zoonotic) | HeV*, Nipah* | BBB, ORN? | |||

| Rhabdoviridae | E | zoonotic | RabV, VSV | NMJs, ORN | |

| ssRNA-RT | Retroviridae | E | Lentivirus | HIV*, HTLV | BBB |

ds: double stranded/ ss: single stranded, E:enveloped/ N: naked, *: emerging virus, ORN: olfactory receptor neuron, RT: reverse transcriptase, MHV: mouse hepatitis virus.

Richardson-Burns, S.M., D.J. Kominsky, and K.L Tyler, Reovirus-induced neuronal apoptosis is mediated by caspase 3 and is associated with the activation of death receptors. J Neurovirol, 2002. 8(5): p. 365-80.

Bergmann, C.C., T.E. Lane, and S.A. Stohlman, Coronavirus infection of the central nervous system: host-virus stand-off. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2006. 4(2): p. 121-32.

Tsunoda, I. and R.S. Fujinami, Neuropathogenesis of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus infection, an animal model for multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol, 2010. 5(3): p. 355-69.

Metcalf, T.U. and D.E. Griffin, Alphavirus-induced encephalomyelitis: antibody-secreting cells and viral clearance from the nervous system. J Virol, 2011. 85(21): p. 11490-501.

Direct infection of nerve endings

a) Invasion of sensory nerve endings

Some viruses can enter the PNS by binding to receptors on axon termini of sensory and autonomic neurons, which respectively convey sensory and visceral information. Most alpha herpesviruses use this route to enter the PNS and establish a life-long persistent infection [3] (Figure 2A). Human alpha herpesviruses include herpes simplex type-1 (HSV-1), HSV-2, and varicella zoster virus (VZV). Well-studied animal alpha herpesviruses include pseudorabies virus (PRV) and bovine herpes virus (BHV). The cellular adhesion molecule, Nectin-1, is a major neuronal receptor for these viruses (except for VZV) [4]. Alpha herpesvirus particles enter sensory nerve endings by membrane fusion, and engage dynein motors for retrograde transport to the neuronal cell body or soma [4]. The capsids then dock at the nuclear pore and the viral DNA is instilled in the nucleus where an acute or a quiescent, latent infection is established. These viruses are unique in maintaining quiescent infections in the PNS neurons of their hosts. This quiescent state can be reversed by certain stress stimuli, which results in the production of large numbers of progeny in a relatively short period of time (1–2 days) [5]. Despite the direct synaptic connection of PNS neurons to the CNS, spread of alpha herpesvirus infection to the CNS is rare, but debilitating, in natural hosts [3]. Alpha herpesvirus trafficking, latency and reactivation is further reviewed in the following sections.

b) Invasion of motor neurons at neuromuscular junctions (NMJs)

NMJs are specialized synapses between muscles and motor neurons that facilitate and control muscle movement. NMJs can be gateways for many viruses to spread into the CNS (Figure 2B). Most motor neurons have their cell bodies in the spinal cord, which in turn, are in synaptic contact with motor centers in the brain. Poliovirus and RABV infections spread into the CNS through NMJs. While RABV particles enter the NMJ directly after a bite from an infected animal, poliovirus particles reach the NMJ by a more circuitous route [6]. Poliovirus infection begins with the ingestion of virus particles followed by replication in the intestinal mucosa and secretion of new virus particles in feces, typically with no CNS infection. However, about 1–2% of poliovirus infections result in the infection of motor neurons that leads to the well-known motor dysfunction, poliomyelitis [6]. The receptor for poliovirus is an Ig superfamily member called CD155, which is found on axonal membranes [7]. Work in transgenic mice expressing human CD155 has led to a model in which the virus replicates in motor neurons within the spinal cord, and subsequent retrograde spread of progeny virions to motor centers in the brain results in muscle paralysis [8, 9].

RABV, a member of the Rhabdoviridae family, infects many animals including bats, skunks, foxes, and dogs, and rhabdoviruses can even infect insects and plants. RABV in animal saliva spreads between hosts via bites or scratches. Animals infected with RABV can survive for months and even years secreting infectious particles in their saliva. In contrast, human infection results in fatal acute myeloencephalitis unless treated with rabies antiserum. RABV particles enter the axons of motor neurons at the NMJ by binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAchR) and neural cell adhesion molecules (NCAM) [10]. Transneuronal spread occurs exclusively between synaptically connected neurons and the infection moves unidirectionally from post-synaptic to presynaptic neurons (retrograde spread). A unique feature of RABV infection of humans is the relatively long asymptomatic incubation period after initial infection, which can last from weeks to one year. This feature provides valuable time for intervention with antiserum, which blocks CNS infection. Once rabies infection reaches the CNS, marked behavioral and neurological symptoms begin and death almost always ensues. If the host survives long enough, virus particles can spread from the CNS to peripheral tissues, particularly to the salivary glands.

c) Invasion via the olfactory epithelium and olfactory neurons

The olfactory system provides a unique and directly accessible portal of entry to the CNS from the periphery. The bipolar olfactory receptor neurons have dendrites in the olfactory epithelium at the roof of the nasal-pharyngeal cavity, where odors are detected. The CNS literally is one synapse away from the environment. The olfactory nerve, which belongs to the PNS, innervates the olfactory epithelium and terminates in the olfactory bulb in the CNS proper (Figure 2C). The olfactory epithelium is well protected from most common infections by mucus and the presence of several pathogen recognition receptor systems [11]. However, in laboratory models, the olfactory portal can be used by some viruses. There is evidence that HSV-1, vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), Borna disease virus (BDV), RABV, influenza A virus, parainfluenza viruses, and prions can enter CNS through olfactory route [12, 13].

Some emerging zoonotic infections may also spread to the CNS by the olfactory pathway. For example, the paramyxoviruses Hendra virus (HeV) and Nipah virus are natural pathogens of bats. HeV infection of humans causes lethal pneumonia, but also causes encephalitis by unknown mechanisms. In mice, HeV is able to infect the CNS after intranasal infection via the olfactory system, which may also be the infection route in humans [14]. An alphavirus, Chikungunyavirus (CHIKV), from the Togaviridae family, is a mosquito-borne pathogen causing high fever, joint pain and skin rash. Although CHIKV is not considered a neurotropic virus, CHIKV may spread into the CNS especially in young or elderly patients [15]. In a mouse model, CHIKV could enter the CNS using the olfactory path [16]. Similarly, La Crosse virus (LACV), a mosquito-borne bunyavirus, causes rare but severe meningoencephalitis, particularly in children. How LACV spreads into the CNS is controversial, but it may occur via viremia after the initial replication in muscle cells [17], or the virus may travel from the olfactory epithelium to the CNS via olfactory neurons [18].

Invasion by Infected circulating leukocytes

Some viruses gain access to the NS without infecting neurons. Instead, these viruses infect leukocytes, which circulate in the blood, and may infiltrate in the brain parenchyma. This mechanism is known as `Trojan horse` entry since the pathogens are hidden within these immune defense cells, which are naturally able to traverse the BBB [19] (Figure 2D). Lentiviruses, including simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and another retrovirus, human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV), may access the CNS by the Trojan horse mechanism after infection of monocytes/macrophages that infiltrate through the BBB [20]. HIV primarily targets CD4+ T-lymphocytes, but also infects macrophages/microglia, which function as specialized phagocytic and antigen presenting cells in the CNS, and astrocytes, which express the cell surface receptor CD4 and appropriate chemokine co-receptors [21, 22]. Viral envelope glycoproteins gp120 and gp41 mediate virion attachment to these receptors. HIV replication is extensively influenced by the immune response induced by the infection. For instance, cytokines produced during infection can either stimulate virus replication or suppress viral entry and replication, depending on the nature of the released cytokine and the state of the cell. CNS invasion occurs when infected memory T-cells or infected monocyte/macrophage precursors traverse the BBB, which then differentiate into perivascular microglia. Virus replication in microglia and the subsequent induction of an inflammatory cytokine response damages the CNS causing depression and cognitive disorders. Notably, 10–20% of infected patients exhibit HIV-Associated Dementia (HAD) [23]. HIV infection also has an effect on the PNS. Between 30–60% of AIDS patients suffer from HIV-associated sensory neuropathy characterized by the degeneration of myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibers [24].

The picornavirus, enterovirus 71 (EV71) [25], and a ubiquitous human polyomavirus, JC virus (JCV) [26], can also infiltrate into the CNS by the Trojan horse mode of entry. In the case of JCV infection, infiltration of infected B-cells into the CNS in immune suppressed patients can result in the infection of oligodendrocytes (the myelin producing cells) and astrocytes, leading to a fatal inflammatory disease in the brain called progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) [26].

Infection of brain microvascular endothelium

In some instances, virus particles in the circulatory system can reach and infect BMVECs, a major constituent of the BBB. RNA viruses such as West Nile virus (WNV) [27], Hepatitis C virus (HCV) [28], HTLV-1 [29], and DNA viruses such as JCV [30], Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [31], human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) [32], and mouse adenovirus 1 (MAV-1) [33] all can infect BMVECs (Figure 2E). Infection of these cells often leads to the disruption of BBB integrity, which is accompanied by the uncontrolled migration of immune cells into the brain parenchyma. Inflammation in the brain tissue induced by the activity of these cells is usually the cause of the observed neurological disorders.

WNV, an arthropod-borne flavivirus, causes encephalitis and meningitis in a small percentage of infected humans after the initial replication in keratinocytes and Langerhans cells in the skin [34]. CNS infections often are associated with inefficient immune clearance of infection in the peripheral tissues and the resulting robust virus replication and subsequent viremia [35]. WNV can access the CNS either by infecting sensory nerve endings, olfactory neurons, or through blood circulation, but not via NMJs [34]. A hallmark of WNV neuropathogenesis is the disruption of the BBB resulting in uncontrolled entry of immune cells into the brain. The infection not only stimulates the loss of tight junction proteins in both epithelial and endothelial cells [36], but also induces production of matrix metalloproteinases that degrade the basement membrane. As a result leukocytes traverse the capillaries into surrounding tissue and release cytokines upon recognition of WNV double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) via toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) signaling [27, 37]. These events are unique to WNV and are not observed with other hemorrhagic flaviviruses such as Dengue virus [36]. HIV, HTLV-1, and MAV-1 infections also may disrupt the BBB by affecting tight junction proteins [29, 33]. MAV-1 infects both BMVECs and macrophages leading to acute encephalomyelitis in susceptible mouse strains, which might explain how human adenovirus infections in immunodeficient patients leads to encephalitis with mortality rate approaching 60% [33, 38].

Another flavivirus HCV, which primarily infects hepatocytes, has also been associated with CNS abnormalities such as cognitive dysfunction, fatigue and depression (reviewed in [39]). BMVECs are the only cell type in the brain that express all four receptors required for HCV entry (scavenger receptor BI, CD81, claudin-1 and occludin). They also support HCV infection in vitro suggesting that they may be the CNS reservoir of HCV [28]. CNS infection by HCV is also associated with increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1, TNF-α, IL-12 and IL18), choline, creatine and inositol, all of which trigger microglia and astrocyte activation, leading to pronounced neurological disorders [39].

Prevalent human DNA viruses that establish life-long, well-controlled persistent infections in other tissues, can also damage the CNS by infecting BMVECs under immune-suppressive conditions. The beta-herpesvirus, HCMV [32], gamma-herpesvirus, EBV [31], and polyomavirus, JCV [30], are among such pathogens. HCMV establishes life-long latency, predominantly in the cells of the myeloid lineage [40]. If the primary infection happens during pregnancy, transmission to the not-yet immune competent fetus may result in a variety of fatal CNS abnormalities such as mental retardation and hearing loss. Besides BMVECs, astrocytes, pericytes, neurons, microglial cells, and importantly, neural stem cells all can be infected with HCMV [32, 41]. Astrocytes and microglial cells naturally produce copious quantities of inflammatory cytokines in response to HCMV infection and this response can promote fetal neurodevelopmental diseases.

EBV establishes life-long latency in memory B-cells ([42]). EBV infection in young adults causes infectious mononucleosis. In rare cases, EBV infection leads to B cell lymphomas (e.g. Burkitt`s lymphoma) and epithelial cell carcinomas (e.g. nasopharyngeal carcinoma). Horwitz and colleagues showed that EBV can infect human BMVECs, where it becomes latent [31]. Virus reactivation in these cells increases inflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression affecting the integrity of the local BBB, which might lead to progression of, the inflammatory neurological disease multiple sclerosis (MS) [31].

Virus induced immune-mediated CNS pathogenesis

The BBB may be disrupted by mechanisms other than endothelial cell infection. Local production of cytokines in the CNS due to viral infections affects tight junctions of the BBB as well. For example, expression of the chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1, CCL2), which is induced by viral infections, is sufficient to disrupt tight junction proteins in the BBB [43] and predispose the brain tissue for immune-mediated neuropathology. An interesting example of virus-induced immune-mediated CNS pathogenesis is the rare, but fatal Borna disease virus (BDV) infection. BDV, a zoonotic RNA virus infecting warm-blooded animals, establishes persistent, non-cytolytic infection in the CNS, particularly in neurons of the limbic system (cortex and hippocampus) [44]. The transmission route into the CNS is probably via the olfactory system, followed by axonal transport and transsynaptic spread to other parts of the brain [45]. Depending on the immune state of the host, BDV replication interferes with a multitude of signaling cascades, deranging the expression of cytokines, neurotrophins that control neuron survival and function, and apoptosis-related genes, leading to neuropathogenesis. Although controversial, human BDV infections might be associated with a variety of neurological disorders including unipolar depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia [45].

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) is a rodent-borne human pathogen that causes CNS disease. Pathogenesis occurs through the combinatorial effects of virus replication and the subsequent host immune response. Humans acquire this infection by inhalation of aerosols or dust suspensions. After the initial replication in lung cells, LCMV virions move into the circulation and can enter the CNS. In animal models, LCMV preferentially infects non-neuronal cells in the brain (i.e. glial cells), which triggers a robust inflammatory response and interferes with neuronal migration [46].

Influenza A (i.e. H5N1, H1N1), an orthomyxovirus that is both zoonotic and endemic in human population, primarily replicates in the lungs after transmission through the respiratory tract. Some of the Influenza A isolates (i.e. HK483) are neurovirulent and can spread to the CNS through olfactory, vagus, trigeminal and sympathetic nerves in mouse models [47]. Interestingly, neurological and cognitive effects associated with influenza infection have also been reported following non-neurotropic H1N1 pandemics. Recent work shows that increased production of proinflammatory cytokines and activation of microglia upon peripheral, non-neurotropic influenza (A/PR/8/34) infection contributes to altered hippocampal structures and cognitive dysfunction in mice in the absence of neuroinvasion [48].

Paramyxoviruses, measles virus (MV), and mumps virus (MuV), which are the causative agents of highly communicable diseases, can also lead to serious CNS infections. Primary MV and MuV infections begin in the upper respiratory tract and infection of lymphoid tissue causes viremia and spread to other tissues. MuV is highly neurotropic and can cause acute encephalopathy in children with high incidence. Elevated levels of multiple cytokines was detected in cerebrospinal fluids of children diagnosed with MuV-associated acute encephalopathy [49]. Unlike MuV, MV infection spreads to the CNS in approximately 0.1% of the cases, causing several types of devastating neurological diseases, such as fatal subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), which manifests weeks to years after infection (reviewed in [50]). Although the molecular mechanisms of CNS infection are not well understood, transgenic rodent models reveal that a complex interplay of innate and adaptive immune system responses are involved including disrupted Th1/Th2 balance and defective T-cell proliferation [51].

These selected examples of neuropathogenesis caused by diverse virus families demonstrate that, while virus replication itself may cause neuropathologies, the activated immune system also contributes to the neuronal damage in an effort to eradicate the infection. Moreover, immune-mediated changes in the CNS induced by one virus infection might stimulate the neuropathogenicity of other viruses, as is seen in co-infections with HIV and HCV, JCV, or HCMV. To better comprehend the effects of viral invasion on the NS, we must understand how viruses interact with, replicate in, and spread in between neurons.

Cell Biology of Neuronal Infection and Spread

Neurons are highly polarized, with distinct dendrite and axonal processes. Single axons can extend meters, many thousands of times the diameter of a typical cell. The maintenance and the communication of distal axons with their cell bodies requires highly specialized signal transduction, intracellular sorting, trafficking, and membrane systems. As obligate intracellular parasites, viruses are dependent on these cellular functions that are often cell-type specific. Accordingly, neurotropic viruses can be divided into two categories: those that accidentally or opportunistically spread to the specialized NS (e.g. WNV, HCV, EBV), and those that have adapted to the NS (e.g. alpha herpesviruses, RABV). From a human health perspective, these fundamental differences in virus/host interaction result in the broad range of viral pathogenesis. In this section we will summarize how viral infections engage neuronal cell biology to enter, traffic and spread between neurons.

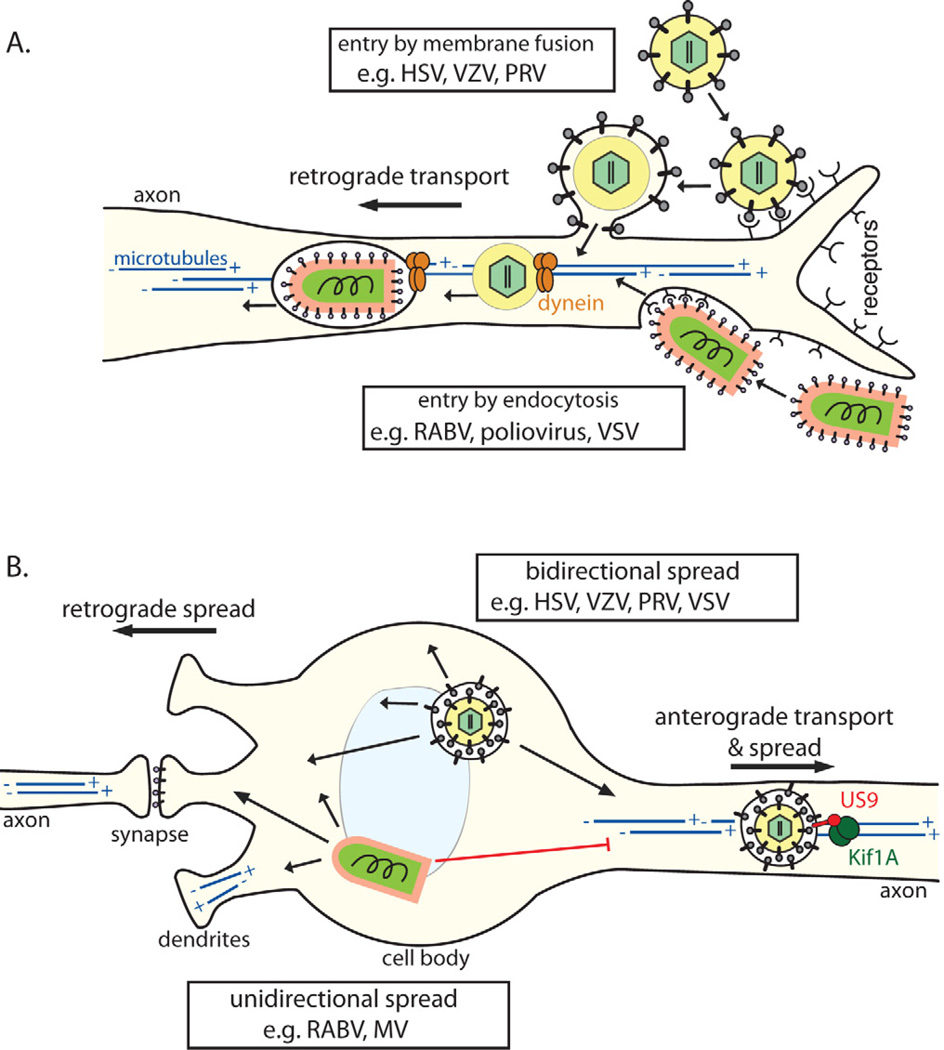

Entry

In general, virions may enter cells by direct fusion with or penetration of the plasma membrane, or by endocytosis. Alpha herpesviruses enter neurons by direct fusion of their virion envelopes with the plasma membrane (Figure 3A) [52]. Nectin-1, a member of the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily, is a receptor for HSV and PRV virions and engages the conserved viral glycoprotein gD on the virion surface to initiate the entry process. After membrane fusion, the capsid with inner tegument proteins is deposited into the axonal cytoplasm, ready for subsequent intracellular transport steps [4].

Figure 3. Cell biology of virus entry, transport, and spread in the NS.

(A) Virons enter axons either via (1) direct fusion with the axonal membrane after receptor attachment (e.g. alpha herpesviruses) or by (2) endocytosis (e.g. RABV; most neurotropic viruses). All particles entering the axon cytoplasm require (−) end-directed dynein motors for long distance retrograde transport on microtubules toward the cell body. Microtubules in axons are uniformly oriented with (+) ends facing the axon terminus and the (−) ends in the cell body. In the cell body and dendrites, microtubules have mixed polarity. (B) Post-replication trafficking and spread of progeny virions. Progeny alpha herpesvirus virions in transport vesicles can be transported anterograde in axons, dependent on the viral protein Us9 associating with the microtubule motor kinesin-3/Kif1A. Egress from axons allows anterograde virus spread from pre-synaptic to post-synaptic neurons. Virions in transport vesicles can also traffic to and egress from the somatodendritic compartment, allowing retrograde spread from post-synaptic to presynaptic neurons. Accordingly, herpesviruses can spread bidirectionally (1) in neuronal circuits. In contrast, enveloped RNA virions (e.g. RABV, MV) acquire their membranes by budding though the plasma membrane during egress. For these viruses, the location of envelopment/egress, and directionality of spread, may depend on the transport and intracellular localization of viral glycoproteins. These viruses tend to spread unidirectionally (2), only from post-synaptic to pre-synaptic neurons.

Most other neurotropic viruses enter neurons by endocytosis, using cellular receptors that are concentrated at nerve terminals (Figure 3A). The following neuromuscular junction proteins serve as viral receptors: Neuron cell adhesion molecules (NCAM) and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) for RABV [10], CD155 for poliovirus [53], and the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) [54]. In addition, many viruses that do not infect neurons during natural infections can enter nerve terminals by endocytosis when artificially introduced, for example, during experimental or iatrogenic infections with adenovirus [54], adeno-associated virus (AAV) [55], and lentivirus vectors [56].

The molecular mechanisms of endocytosis are well studied in a variety of cell types [57]. Compared to non-neuronal cells, neuronal endocytosis is highly regulated, and mediated by many neuron-specific isoforms of the conserved endocytosis machinery. At nerve terminals, in particular, the most prominent and best studied endocytic activity is a specialized mode of clathrin-mediated endocytosis for neurotransmitter reuptake and synaptic vesicle recycling [58]. These endocytic/recycled synaptic vesicles typically remain near the presynaptic active zone for ongoing rounds of endo- and exocytosis, and therefore their role in mediating viral entry is unclear. Other vesicle populations, including those with canonical early and late endosomal markers like Rab5 and Rab7 GTPases are present in axons, but their genesis, fate and role in virus entry is also uncertain.

Upon endocytosis, the lumen of endocytic vesicles is rapidly acidified by vacuolar ATPases. In non-neuronal cell types this pH change is often a trigger for virions to fuse with or otherwise disrupt the vesicle membrane, to reach the cytoplasm [57]. Interestingly, in neurons, most virions remain inside the endocytic vesicle for subsequent long-distance retrograde trafficking to the neuronal cell body (e.g. rabies virus [59], polio [60], and adenoviruses [54]). Studies of the endocytosis and trafficking of canine adenovirus 2 (CAV-2) and tetanus neurotoxin (TeNT) revealed a population of endocytic vesicles with a neutral pH, suggesting that such non-acidified vesicles may generally promote the retention and subsequent trafficking of neurotropic viruses [61].

Post-Entry Retrograde Transport

After axonal entry, virus particles must undergo retrograde transport to the cell body using motor proteins that move along microtubules (Figure 3A). Generally in polarized cells and particularly in axons, microtubules are oriented with the (+) end at the cell periphery or axon terminal, and the (−) end toward the cell body. The kinesin family of motor proteins generally mediates (+) end-directed anterograde transport (from the soma to the axon terminus), and dynein motor complexes generally mediate (−) end-directed retrograde transport (from axon terminus to soma) [62].

After membrane fusion and entry into axons, alpha herpesvirus capsid/inner tegument complexes undergo very efficient retrograde transport to the cell body (Figure 3A). The viral protein VP1/2 (UL36), a major component of the inner tegument, recruits (−) end-directed dynein motors for this retrograde transport [63]. However, retrograde axonal transport is punctuated by brief anterograde movements, purified capsid/inner tegument complexes also bind kinesin motors, and VP1/2 is a multifunctional protein involved in multiple intracellular transport steps during virus replication [4]. Thus, motor recruitment by VP1/2, and other viral and cellular factors, is likely a complex and regulated process requiring further study.

Like alpha herpesvirus particles, RABV virions were thought to immediately undergo membrane fusion, releasing the viral nucleocapsid into the axon cytoplasm, as typically occurs in non-neuronal cell types. The nucleocapsid associated P protein was proposed to mediate retrograde axonal transport by binding dynein light chain LC8. However, other studies demonstrated that P protein binding to LC8 is not necessary for RABV neuropathogenesis [64], and RABV virions instead remain within endocytic vesicles during retrograde transport [59] (Figure 3A).

The fact that most neurotropic viruses, particularly those not adapted to the nervous system, are transported within endocytic vesicles presents an inherent topological problem. Unlike alpha herpesvirus particles, which are exposed to the axon cytoplasm immediately after entry, these endocytosed virions are trapped in the lumen of an endosome and therefore can neither recruit motor complexes nor directly modulate the transport machinery, but may remain passive cargo of the pre-existing axonal transport pathways. Several viruses appear to use a common retrograde transport pathway involved in neurotrophin signal transduction. In this signaling pathway, neurotrophins (e.g. nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)) and their receptors (e.g. p75NTR and TrkB) are incorporated into Rab5-positive early endosome-like vesicles, which mature into Rab7-postive late endosome-like vesicles. Rab7 mediates recruitment of dynactin (p50/glued), part of the dynein complex, and these vesicles undergo retrograde transport to the neuronal cell body [65]. This pathway is implicated in the retrograde transport of poliovirus [60], rabies virus [66], canine adenovirus (CAV-2), and tetanus neurotoxin (TeNT) [54, 61]. These endosomal transport vesicles appear to remain at neutral pH, which may stabilize pH-dependent viruses within the endosome [54, 61].

In some cases, the interaction between virions and their cellular receptors may direct the retrograde transport of the virion-containing endocytic vesicle. For example, the poliovirus cellular receptor, CD155, which is endocytosed along with the virion, binds the dynein light chain Tctex-1 to engage the retrograde transport machinery [53]. Similarly, the envelope glycoprotein (G protein) of RABV and related rhabdoviruses can confer endocytosis and efficient retrograde transport functions to heterologous lentivirus vector particles [56, 67], suggesting that interaction between the G protein and a cellular receptor (possibly p75NTR [66], see above) mediates retrograde transport.

While these examples provide some insight into the molecular mechanisms of post-entry retrograde transport, it is not clear if virions endocytosed at nerve terminals engage a common or default retrograde transport pathway, and to what extent they alter or modulate these intracellular trafficking mechanisms.

After entry and retrograde transport to the cell body, viral nucleic acid genomes replicate, and express mRNA and proteins. Remarkably, the biosynthetic machinery (i.e. ribosomes & secretory pathway organelles) of neurons is distributed in axons and dendrites as well as the cell bodies. It is not clear whether this distribution of cellular machinery facilitates compartment-specific viral replication and gene expression.

Post-Replication Transport, Egress, and Spread

Many neurotropic virus infections (e.g. RABV, alpha herpesviruses, MV, WNV) spread between chains of connected neurons. Virions do not typically spread by free diffusion, but rather between tightly connected neurons via neurochemical synapses or other close cell-cell contacts. Infected PNS neurons often are in direct synaptic contact with CNS neurons providing a direct route of spread from the periphery. Consequently, CNS infection is determined in part by the directionality of virus spread along neuronal circuits, which is influenced by directional intracellular virus transport and egress. Motor neurons receive input from CNS neurons via synapses on the somatodendritic plasma membrane (i.e. post-synaptic contacts), and relay these signals to neuromuscular junctions at axon termini. RABV, which typically infects motor neurons, spreads exclusively in the retrograde direction along neuronal circuits, exiting from the somatodendritic plasma membrane to spread towards the CNS (Figure 2B). Most neurotropic viruses are capable of spreading retrograde in neural circuits, suggesting that there may be common or default somatodendritic transport pathways. In contrast to motor neurons, sensory neurons are typically pseudounipolar, with two axon-like projections: one innervating peripheral tissues, and the other making pre-synaptic contact with CNS neurons (Figure 2A). To be able to spread within this pseudounipolar architecture, the alpha herpesviruses have evolved the capacity to spread in the anterograde direction, exiting from axon termini. The alpha herpesviruses are among the very few viruses that are capable of bidirectional spread (both anterograde and retrograde direction) (Figure 3B).

Like post-entry transport, post-replication transport of viral components also requires microtubule motors. The cellular mechanisms that determine whether cargo is transported into the axon or into dendrites are not entirely clear; however, several mechanisms are apparent [62]. First, the axon initial segment contains a mesh of actin filaments proposed to function as a molecular sieve, preventing macromolecular complexes like transport vesicles or virions from entering the axon non-specifically. Some motors, for example kinesin-1/KIF5, efficiently penetrate this barrier, providing a level of specificity so that only particular cargo/adaptor/motor combinations are transported into the axon. Second, stable microtubules acquire post-translational modifications, most notably C-terminal detyrosination and K40 acetylation of alpha-tubulin. Both axons and dendrites contain acetylated microtubules, and axons are enriched in detyrosinated microtubules. Kinesin-1/KIF5 preferentially binds these modified microtubules, suggesting that post-translational modifications may also regulate cargo transport into axons. Finally, microtubule polarity differs between axons and dendrites. While microtubules in axons have a uniform, parallel orientation, with (+) ends at the axon terminus and (−) ends in the soma, microtubules in dendrites have mixed, anti-parallel orientations. This difference in microtubule polarity would allow only (+) end-directed kinesin motors to enter axons, whereas the (−) end-directed dynein complex could enter dendrites [62]. Indeed, one study using a drug-inducible protein dimerization system showed that experimentally recruiting kinesin-1/KIF5 or kinesin-2/KIF17 induces cargo transport into axons, whereas recruiting dynein induces transport into dendrites [68].

While enveloped virions may exit cells by budding though cellular membranes, which preserves membrane topology, non-enveloped viruses (e.g. poliovirus, Ad) must breach membranes to enter or exit a cell. How non-enveloped viruses cross-cellular membranes, particularly neuronal membranes, without causing extensive cytopathology is not well understood (reviewed in [69]). However, a study on Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV), a non-enveloped picornavirus like poliovirus, revealed that TMEV can exit from neurons into oligodendrocyte myelin sheaths without axon lysis/degeneration [70]. It is not clear if other non-enveloped viruses can spread between neurons without cell lysis/axon degeneration.

In the case of many enveloped viruses (e.g. RABV, MV) final assembly and egress are coordinated processes (Figure 3B). Viral components and sub-assemblies, such as nucleocapsids and membrane proteins, are transported separately and meet at the plasma membrane. Virions then acquire their envelope budding through the plasma membrane, simultaneously completing assembly and egress from the cell. For decades researchers have recognized that viral membrane proteins (i.e. glycoproteins and matrix proteins) are sorted either to the apical or basolateral side of polarized epithelial cells, and that release of enveloped viruses is often polarized accordingly (see [71] for relevant discussion). Analogously, if viral envelope proteins are preferentially sorted into the axons or dendrites, virion assembly, egress, and trans-synaptic spread may also be polarized. In support of this model, a recent study showed that the directionality of viral spread along synaptic connections depends on the viral glycoprotein G [72]. In this study, the authors produced recombinant VSV expressing G proteins from either RABV (a related rhabdovirus), LCMV (an unrelated arenavirus), or its native VSV G protein. The RABV G protein conferred retrograde (post-synaptic to pre-synaptic) spread across synaptic connections, whereas the LCMV or native VSV G proteins conferred anterograde (pre-synaptic to post-synaptic) virus spread [72]. While it is difficult to draw conclusions about the functions of viral proteins outside of their natural context, these studies contribute towards a mechanistic understanding of viral spread in the NS. But important questions remain: What are the molecular determinants of viral glycoprotein sorting in neurons? How is the transport of nucleocapsids and other viral factors coordinated to ensure efficient assembly and egress? And, does this glycoprotein-centric model hold true for other enveloped viruses?

The transport of nascent alpha herpesvirus particles is now understood in more molecular detail. These viruses replicate their genome and assemble capsids in the nucleus, traverse the nuclear envelope, acquire tegument proteins, and obtain their envelope by budding into trans-Golgi-like membranes [4]. There has been some debate whether alpha herpesviruses fully assemble in the neuronal cell body prior to axonal transport, or if sub-assemblies are transported to distant sites of final assembly. The details of this debate are reviewed elsewhere [4, 73], but it is clear that alpha herpesviruses have evolved neuron-specific viral mechanisms to direct anterograde transport and spread along circuits of synaptically connected neurons. For both HSV and PRV, three conserved viral membrane proteins, gE, gl, and US9, are necessary for efficient anterograde transport and spread [4]. While the role of US9 in HSV is debated, US9-null PRV mutants are completely defective in anterograde transport and spread in neurons, and these phenotypes appear to be neuron-specific [74]. US9 is dispensable in non-neuronal cells, and for retrograde somatodendritic egress in neurons. A recent study demonstrated that PRV US9 associates with the neuron-specific (+) end-directed microtubule motor kinesin-3/KIF1A, providing a molecular basis for this neuron-specific phenotype [75]. According to this model, PRV US9 mediates the recruitment of KIF1A, which mediates both sorting into axons and anterograde transport leading to spread of infection from pre-synaptic to post-synaptic cells in a neuronal circuit (Figure 3B). Thus, in bipolar neuronal circuitry, PRV serves as an illustrative example of how directional spread along neuronal circuits depends on the directionality of intracellular transport and egress. Ongoing research to identify the cellular and molecular mechanisms of viral transport and egress in neurons will be necessary to fully understand how other neurotropic viruses spread through the NS.

However, directional transport in neurons is not the sole determinant of spread in neuronal circuits. For example, PRV and other alpha herpesviruses naturally infect pseudounipolar sensory neurons that have two axon-like projections. Thus, anterograde axonal transport could direct progeny virions down either branch, into peripheral tissues or into the CNS (Figure 4). Yet, spread to the CNS is typically rare or inapparent. In this case, the directionality of spread in the nervous system may depend on factors other than intracellular transport, such as intrinsic immune responses and latency, as described in the following section.

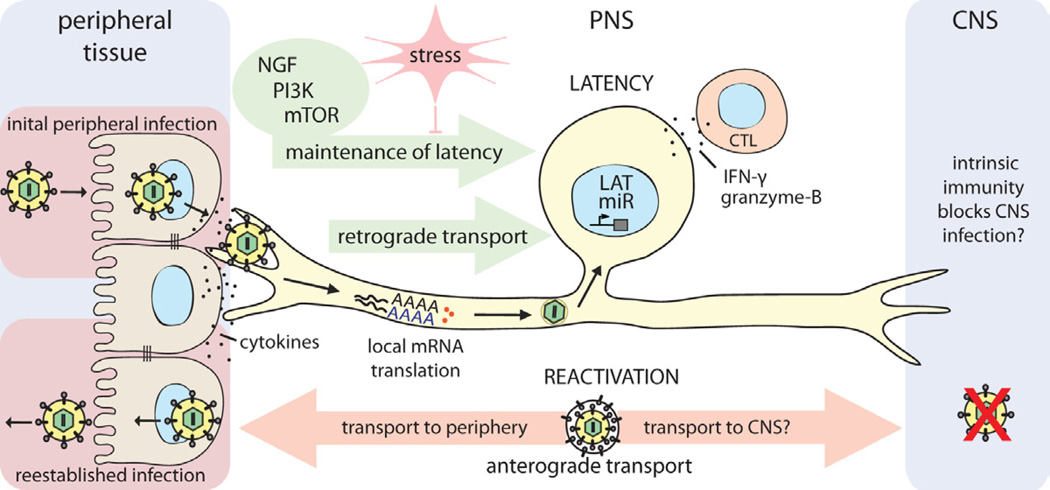

Figure 4. Establishment and control of alpha herpesvirus latency in PNS neurons.

HSV-1 enters the host organism through mucosal/epithelial surfaces. Initial replication in epithelial cells results both in cytokine secretion and viral spread. Progeny virions enter sensory nerve terminals and undergo long-distance retrograde transport to the neuronal cell body. Localized intracellular signaling and protein translation in distal axons induced by cytokines and viral proteins during entry supports retrograde particle transport and also may influence the establishment of latency in neuronal cell bodies. Once in the nucleus, viral latency genes are activated (e.g. LAT, miRs), and the HSV-1 genome is repressed. CD8+ CTLs secreting IFN-γ and granzyme-B, and continuous retrograde NGF-PI3K-mTOR signaling from distal axons contribute to maintaining this latent state of infection. If this homeostasis is disrupted by environmental or nutritional stress, the HSV-1 genome reactivates lytic gene expression, leading to virus replication. Newly replicated virions traffic back by anterograde axonal transport mechanisms, to reestablish infection at epithelial tissues. It is still not understood why CNS invasion is rare after reactivation from latency, even though both axonal projections of the pseudounipolar sensory neuron are accessible to HSV-1 virion transport. If there is no difference in transport, it may be that HSV-1 does invade the CNS, but is strongly suppressed or silenced by an effective intrinsic immune response in CNS neurons of healthy individuals.

Alpha herpesvirus invasion of the nervous system: the potential for a lifetime association

The life-long persistence of herpesvirus genomes in their natural hosts coupled with the capacity to reactivate the quiescent infection to produce infectious particles that transmit to other hosts is remarkable in many ways (reviewed in [76]). Three subfamilies of the herpesviridae establish a latent persistent infection in different cell types: Alphaherpesvirinae (PNS neurons); betaherpesvirinae (monocyte/macrophage precursors); and gammaherpesvirinae (B and T cells) [77]. In most cases, the quiescent herpesvirus genome is not integrated into the host genome and either exists as a non-replicating, quiescent histone-covered molecule, or as a replicating extra “chromosome” (reviewed in [42]). Recently, this paradigm was broken by human herpesvirus 6, a beta herpesvirus that can integrate into the host genome [78].

Alpha herpesvirus genomes can remain in a latent, but reactivatable state in neurons of essentially all PNS ganglia. HSV-1 and HSV-2 are two human alpha herpesviruses causing cold sores and genital herpes. A third human alpha herpesvirus, VZV, causes chickenpox during primary infection of children, and zoster (shingles) when the virus reactivates in the ganglia that transmit sensory signals toward the brain (e.g. dorsal root ganglion, trigeminal ganglion). Infection initiates in epithelial cells at a mucosal surface. The primary infection is usually well contained by host defenses, and overt pathogenic effects are rare. Some viral progeny invariably enter axon terminals that innervate the infected tissue and move on microtubules to PNS cell bodies where a productive or latent infection may be established (Figure 4). Establishing the quiescent infection in PNS neurons is a multistep process and depends on the efficiency of several parameters: i) virus replication in non-neuronal cells under the pressure of local intrinsic, innate and humoral immune responses; ii) virion entry into axon terminals and retrograde transport of nucleocapsids to the neuronal cell body; and, iii) intrinsic and innate immune responses in the infected neuron and ganglia. After the latent infection is established, maintenance of this silent state requires continuous action of surrounding glial and virus-specific CD8+ T-cells that suppress lytic gene expression through secretion of IFNγ and granzyme-B [79].

Recent studies with HSV-1 suggest that infection of neurons following axonal entry is inherently biased toward a latent infection because when the HSV-1 virions enter axons, some critical tegument proteins are transported toward the cell body separately from the capsid [80]. When neuronal cell bodies are exposed directly to purified virions, the infection is instead productive. This bias towards latency presumably occurs because productive infection may require that both tegument proteins and capsids containing the viral genome arrive at the nucleus at the same time [81, 82]. Besides this long-distance trafficking, other factors such as cytokine and IFN production also influence the outcome. The cytokines produced after primary infection of epithelial cells or the virion attachment to axonal receptors might induce an anti-viral state in neuronal soma before the genome reaches the nucleus. Indeed, De Regge et. al., using an in vitro two-chamber neuron culture system showed that treatment of trigeminal ganglion neurons with IFNα before HSV-1 or PRV infection is sufficient to suppress lytic gene expression and induce a quiescent infection [83].

A hallmark of alpha herpesvirus latency is the expression of a latency-associated transcript (LAT) and several microRNAs (miRNAs) [84, 85]. Although the exact role of the LAT transcripts is still not well understood, there is evidence that these non-coding RNAs are involved in blocking apoptosis of the infected neuron, and in the control of reactivation from latency (see review [86]). Besides LAT, HSV-1 miRNAs target the key regulators of the viral lytic cycle (i.e. ICP0) to control and stabilize latency. Remarkably, for VZV, six different transcripts and proteins are produced during latency. Interestingly, one of the most abundant proteins, ORF63, is predominantly cytoplasmic during latency but localizes mostly in the nucleus during lytic infection [87]. Nevertheless, almost 90% of the viral genome remains transcriptionally silent during latent HSV-1, HSV-2 or PRV infection, and importantly, the infected neuron is not recognized or eliminated by the immune system.

Such long-term maintenance of a silenced viral genome in a state that can be reactivated requires precise control and a high threshold for reactivation. Stress responses, including nutritional, hormonal, and environmental, can reactivate a latent genome. Strikingly, although reactivation can recur throughout the life of the host, it seems to have little adverse effect on PNS function. This is, in part, because few latently infected neurons undergo reactivation: in vivo animal experiments show that only 1–3 neurons, among thousands of latently infected cells in the trigeminal ganglion, display signs of reactivation in a single recurrence [88].

Furthermore, neurons have evolved to inherently avoid cell death, and viruses that persist in neurons have also adapted to prevent the death of their host cells. These neuronal and viral pro-survival strategies clearly allow neurons to survive during a latent herpesvirus infection. but it may be that these same strategies promote neuronal survival during reactivation as well. It appears that a fine balance exists between the immune system of a naturally immunized host and the virus replication machinery, limiting virus replication and subsequent axon-to-cell spread of the progeny even during reactivation [89, 90]. Indeed, It appears that neurons can tolerate not only high viral genome inputs but also abundant viral gene expression, which possibly is controlled by the suppressing action of nearby CD8+ T-cells [79]. Furthermore, autophagy is a neuronal pro-survival strategy to block several neurotropic virus infections (i.e. Sindbis virus (SINV), HCMV, HSV-1) [91–93]. The autophagy machinery normally is used by cells to engulf cytosolic material in a double-membrane vesicle to be degraded by the lysosomes. HSV-1 encodes proteins that modulate autophagy in a neuron-specific manner. For example, autophagy is activated in response to HSV-1 infection through interferon-induced protein kinase R (PKR), which induces an anti-viral signaling cascade in response to viral dsRNA [94]. The HSV-1 protein ICP34.5 interferes with this pathway by binding to and inactivating Beclin-1, a host protein responsible for the recruitment of other autophagy proteins [93]. This interaction has little effect or advantage in non-neuronal cells, but promotes HSV-1 persistence in neurons and also pathogenesis if the infection spreads to the CNS [95].

After reactivation, it is not clear if progeny herpesvirus virions are transported towards the CNS, and if so, what prevents devastating CNS infection and pathogenesis in most immune-competent individuals? A recent elegant study revealed the importance of neuronal intrinsic immunity in the control of HSV-1 spread in the NS. Children with genetic defects in the antiviral TLR3-interferon pathway have a higher risk of herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) during primary infection with HSV-1. Using pluripotent stem cells from susceptible children, the authors showed that a TLR3-dependent intrinsic immune response in neurons is crucial to restrict HSV-1 spread in the NS [96]. It is likely that, the lack of this defense system in neurons prevents the establishment of latency in the peripheral ganglia, promoting further viral spread into the brain. Once in the brain, where HSV-1 replication is normally tightly restricted, TLR-3 deficient neurons may continue to support virus replication leading to HSE.

The herpesvirus latency/reactivation cycle is understood in principle, but important details are lacking. Small animal models (i.e. mouse peripheral infection and rabbit eye models to study HSV-1, and guinea pig model for HSV-2 latency) have been quite useful, but do not recapitulate all the nuances of latency in humans [76, 97]. However, latency and reactivation have been addressed using PNS neurons cultured in vitro, and these studies have provided some mechanistic understanding of these phenomena [5, 98]. HSV-1 latency is proposed to be maintained by the continuous binding of nerve growth factor (NGF) to the TrKA receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) and activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K)-Akt signaling pathway [5, 98]. Recently, Kobayashi et. al. further showed that the key target of PI3K-Akt signaling is mTORC1 in axons [99]., The mTOR system regulates the translational repressor elF4E-binding protein (4E-BP), which influences the state of latent viral genomes in the neuronal nucleus. Although the cellular effectors of this pathway that suppress the viral lytic gene expression is still unknown, any interference with this signaling cascade (e.g. NGF depletion, inhibition of mTOR activity, hypoxia) breaks latency control and promotes reactivation. It appears that a variety of physiological stimuli originating in the periphery are integrated in the local mTOR system in axons and relayed to the cell body. This local monitoring in axons and long distance signaling to the cell body could alarm and protect neuronal cell bodies, but at the same time might be repurposed for the replication of opportunistic viruses that invade the nervous system (Figure 4).

What controls invasion of the nervous system: a herpesvirus perspective

Alpha herpesvirus infection of immune competent hosts presents an apparent two-part paradox: First, during primary infection, the infection passes with high efficiency from epithelial surfaces to the nerve terminals, and on to the soma of PNS ganglia neurons. Indeed it is difficult to block primary PNS invasion once epithelial cells are infected. Second, once in the PNS, infection rarely spreads further to the brain. We learned from animal models and mutant virus infections that a complex interplay exists between the host immune system and the NS adapted viral replication strategy. For instance, virulent PRV infection of the skin induces a violent, inflamed peripheral pruritus with almost no further spread to the brain in mice [100]. By contrast, the attenuated mutant strain PRV Bartha, which replicates as well as wild type virus, produces almost no tissue damage and peripheral inflammation, yet is massively neuroinvasive ([100]). This property makes PRV Bartha an excellent neural tracer [100].

What regulates controlled alpha herpesvirus spread in the NS, and how does the infection proceed differently in neurons, non-neuronal cells, PNS neurons, and CNS neurons? The answer may lie within the specialized signaling and gene expression patterns that maintain highly polarized morphology and function of neurons. Such a differentiated system calls for a long-distance communication between the axon terminals which are in contact with epithelial or muscle cells, and the cell bodies in the ganglia. This axon-to-cell body communication must be finely tuned, so that cell bodies are well informed about distant events near axon terminals, but at the same time should not overreact. It is noteworthy that PNS neurons produce little type I IFN after HSV-1 infection [101, 102]. However, when herpes virions invade epithelial cells, prior to infecting nerve terminals, these infected cells produce a variety of inflammatory and antiviral cytokines, including type I IFN. Such potent signaling molecules are likely to have an effect on local axon function and subsequent viral invasion of PNS neurons [103]. Indeed, previous work on human dorsal root ganglion neurons in a chambered culture system showed that IFNα and IFNγ, added to the epidermal cell compartment, after axonal transmission of HSV-1 infection, inhibit infection and spread [104].

Certainly, information about events at nerve termini (i.e. damage, inflammation, infection) must be transmitted to the distant neuronal cell bodies to produce an appropriate response at the site of axonal insult. Because some axons can be centimeters to meters long, efficient and rapid transmission presents a potential problem for homeostasis of the neuron. How this long distance communication is accomplished remains a fundamental problem in neuroscience and in virology. New findings suggest that new protein synthesis in axons upon environmental stimuli, and subsequent transport of local signaling molecules to the nuclei might serve this function. Indeed a subset of mRNAs and the complete protein synthesis machinery are localized to axons in uninfected neurons, far away from the cell body [105]. Local translation in axons, not in the distant cell body, regulates growth cone navigation and integrity during development and regeneration, and retrograde communication with the cell body in adult neurons and plays a key role in axonal damage signaling [106].

We have found that local events involving axonal protein synthesis in or near the initially infected axon termini facilitate neural invasion and spread [107]. Our results also suggest that virus infection stimulates an axonal response similar to injury signaling, and these damage/danger signals induced by initial axonal infection and subsequent inflammatory events at the site of primary infection affect axonal transport of viral particles to the neuronal nuclei. Interestingly, retrograde transport of poliovirus to the CNS in mice is inefficient unless there is muscle damage at the site of infection [108]. For PRV, we and others have seen almost the opposite: tissue damage blocks neural invasion [107, 109]. Perhaps these local events in the PNS ganglia or near the infected axons contribute to determining lytic vs. latent infection states and controlling further neuroinvasion.

It is still a mystery why spread of alpha herpesviruses to the CNS after the initial peripheral infection or after reactivation from latency is rare. There is no evidence that the block is at the cellular and molecular level of axonal transport to the CNS neurons. Perhaps the limitation is in the replication of virus in CNS neurons. Like PNS neurons, these neurons may be less permissive to lytic herpesvirus infection. CNS and PNS neurons may both have specialized intrinsic immune responses that promote abortive infections and long-term maintenance of latency. The suggestion that herpesvirus particles or genomes are present in the brain of latently infected individuals draws attention to possible correlation between herpesvirus infection and neuropathologies like Alzheimer`s disease [110]. Such correlations remain difficult to study due to the lack of appropriate experimental models.

Future Perspectives

The interaction of viruses with their hosts is noteworthy in many ways. Studying the complex interplay between these tiny intracellular entities and the infected cell in a culture dish has taught us many valuable lessons in cell biology. However this interaction between virus and host in vivo is even more complicated by the hierarchical organization of cells, tissues, and systems. This complexity, while providing layers of protection against microbial invasions, also requires strictly regulated communication among cells and tissues to produce the appropriate protective response. If this combined reaction to viral attack is not sufficient, balanced and controlled, severe pathology is likely.

It is striking that there is no prototypical virus that spreads to the CNS. Viruses with RNA or DNA genomes, enveloped or naked virions, members of diverse virus families, all can spread into the CNS under the right conditions. In general, even viruses capable of infecting a variety of cell types tend to spread from one tissue to another until they reach a barrier. If the infection is not contained locally (due to inefficient intrinsic and innate immune reaction) it can spread to vital organs causing severe pathologies. Damage to cells can result from viral replication or by the action of the activated immune system. Virus spread to CNS can be deadly, not only because infected neurons may die, but also because of the immune-mediated inflammation in the brain. We now recognize that we are constantly infected and colonized with numerous microorganisms, some of which can affect spread and pathogenesis of invading microbes (the microbiome). This complex interaction of host and microbes was not recognized and routinely neglected in in vitro and in vivo experimental models. However, recent pioneering work [111, 112] suggest methods and models of how to approach these complex and multifactorial biological problems.

Historically, research on PNS-adapted alpha herpesviruses, zoonotic RABV, and enteric poliovirus, taught us much of what we know about viral spread in the NS. Developing techniques such as live-cell and intravital imaging together with neuron culturing methods (in chambers or microfluidic devices, and co-cultures with other cell types) accompanied by the ability to construct recombinant viruses, now allow researchers to study some of the fundamental characteristics of virus replication and spread within and between neurons. These approaches will enable new mechanistic understanding of how neurotropic viruses gain access to and spread in the NS. In vitro culture of human neuronal/pluripotent stem cells, and closer-to-natural-host models such as `humanized mice` carrying human-specific genes, cells, or tissues will reveal host-specific aspects of lytic or latent infections caused by human viruses. Novel techniques, such as deep sequencing of viral nucleic acid from clinical samples or single molecule sequencing will facilitate identification of more neurovirulent and/or neuroinvasive virus mutants, and will provide a genetic view of host barriers and viral bypass mechanisms. Screening of diseased tissues by these techniques will enable the detection of minute quantities of viral genomic material, possibly revealing more roles for viruses in a variety of neuropathologies even if we cannot propagate them in the laboratory.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Enquist lab, especially M.P. Taylor, R. Song, E. Engel, K. Lancaster and A. Ambrosini for critical reading of the manuscript. L.W.E. acknowledges support from US National Institutes of Health grants NS033506 and NS060699. I.B.H. is supported by fellowship PF-13-050-01-MPC from the American Cancer Society.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Teijaro JR, et al. Endothelial cells are central orchestrators of cytokine amplification during influenza virus infection. Cell. 146(6):980–991. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffin DE, Metcalf T. Clearance of virus infection from the CNS. Curr Opin Virol. 2011;1(3):216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tirabassi RS, et al. Molecular mechanisms of neurotropic herpesvirus invasion and spread in the CNS. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1998;22(6):709–720. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(98)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith G. Herpesvirus transport to the nervous system and back again. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012;66:153–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camarena V, et al. Nature and duration of growth factor signaling through receptor tyrosine kinases regulates HSV-1 latency in neurons. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8(4):320–330. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Racaniello VR. One hundred years of poliovirus pathogenesis. Virology. 2006;344(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ren R, Racaniello VR. Human poliovirus receptor gene expression and poliovirus tissue tropism in transgenic mice. J Virol. 1992;66(1):296–304. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.296-304.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohka S, et al. Poliovirus trafficking toward central nervous system via human poliovirus receptor-dependent and -independent pathway. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:147. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuss SK, Etheredge CA, Pfeiffer JK. Multiple host barriers restrict poliovirus trafficking in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(6):el000082. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ugolini G. Rabies virus as a transneuronal tracer of neuronal connections. Adv Virus Res. 2011;79:165–202. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387040-7.00010-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalinke U, Bechmann I, Detje CN. Host strategies against virus entry via the olfactory system. Virulence. 2011;2(4):367–370. doi: 10.4161/viru.2.4.16138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Detje CN, et al. Local type I IFN receptor signaling protects against virus spread within the central nervous system. J Immunol. 2009;182(4):2297–2304. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mori I, et al. Olfactory transmission of neurotropic viruses. J Neurovirol. 2005;11(2):129–137. doi: 10.1080/13550280590922793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dups J, et al. A new model for Hendra virus encephalitis in the mouse. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arpino C, Curatolo P, Rezza G. Chikungunya and the nervous system: what we do and do not know. Rev Med Virol. 2009;19(3):121–129. doi: 10.1002/rmv.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powers AM, Logue CH. Changing patterns of chikungunya virus: re-emergence of a zoonotic arbovirus. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(Pt 9):2363–2377. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82858-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson RT. Pathogenesis of La Crosse virus in mice. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1983;123:139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett RS, et al. La Crosse virus infectivity, pathogenesis, and immunogenicity in mice and monkeys. Virol J. 2008;5:25. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGavern DB, Kang SS. Illuminating viral infections in the nervous system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(5):318–329. doi: 10.1038/nri2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaul M, Garden GA, Lipton SA. Pathways to neuronal injury and apoptosis in HIV-associated dementia. Nature. 2001;410(6831):988–994. doi: 10.1038/35073667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin KA, et al. CD4-independent binding of SIV gpl20 to rhesus CCR5. Science. 1997;278(5342):1470–1473. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5342.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schweighardt B, Atwood WJ. Virus receptors in the human central nervous system. J Neurovirol. 2001;7(3):187–195. doi: 10.1080/13550280152403236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McArthur JC, et al. Relationship between human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia and viral load in cerebrospinal fluid and brain. Ann Neurol. 1997;42(5):689–698. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamerman PR, et al. Pathogenesis of HlV-associated sensory neuropathy: evidence from in vivo and in vitro experimental models. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2012;17(1):19–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2012.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solomon T, et al. Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of enterovirus 71. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(11):778–790. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boothpur R, Brennan DC. Human polyoma viruses and disease with emphasis on clinical BK and JC. J Clin Virol. 2010;47(4):306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verma S, et al. Reversal of West Nile virus-induced blood-brain barrier disruption and tight junction proteins degradation by matrix metalloproteinases inhibitor. Virology. 2010;397(1):130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fletcher NF, et al. Hepatitis C virus infects the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(3):634–643. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.028. e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Afonso PV, et al. Alteration of blood-brain barrier integrity by retroviral infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(11):e1000205. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapagain ML, et al. Polyomavirus JC infects human brain microvascular endothelial cells independent of serotonin receptor 2A. Virology. 2007;364(1):55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casiraghi C, Dorovini-Zis K, Horwitz MS. Epstein-Barr virus infection of human brain microvessel endothelial cells: a novel role in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;230(1–2):173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fish KN, et al. Human cytomegalovirus persistently infects aortic endothelial cells. J Virol. 1998;72(7):5661–5668. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5661-5668.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gralinski LE, et al. Mouse adenovirus type 1-induced breakdown of the blood-brain barrier. J Virol. 2009;83(18):9398–9410. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00954-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim SM, et al. West Nile virus: immunity and pathogenesis. Viruses. 2011;3(6):811–828. doi: 10.3390/v3060811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho H, Diamond MS. Immune responses to West Nile virus infection in the central nervous system. Viruses. 2012;4(12):3812–3830. doi: 10.3390/v4123812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Z, et al. West Nile virus infection causes endocytosis of a specific subset of tight junction membrane proteins. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang T, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 mediates West Nile virus entry into the brain causing lethal encephalitis. Nat Med. 2004;10(12):1366–1373. doi: 10.1038/nm1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashley SL, et al. Mouse adenovirus type 1 infection of macrophages. Virology. 2009;390(2):307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fletcher NF, McKeating JA. Hepatitis C virus and the brain. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19(5):301–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2012.01591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodrum F, et al. Differential outcomes of human cytomegalovirus infection in primitive hematopoietic cell subpopulations. Blood. 2004;104(3):687–695. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheeran MC, Lokensgard JR, Schleiss MR. Neuropathogenesis of congenital cytomegalovirus infection: disease mechanisms and prospects for intervention. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(1):99–126. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00023-08. Table of Contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Speck SH, Ganem D. Viral latency and its regulation: lessons from the gamma-herpesviruses. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8(1):100–115. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stamatovic SM, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 regulation of blood-brain barrier permeability. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25(5):593–606. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Planz O, Pleschka S, Wolff T. Borna disease virus: a unigue pathogen and its interaction with intracellular signalling pathways. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11(6):872–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]