Abstract

Cancer and its treatments produce a myriad of burdensome side effects and significantly impair quality of life (QOL). Exercise reduces side effects and improves QOL for cancer patients during treatment and recovery. Exercise prior to, during, and after completion of cancer treatments provides numerous beneficial outcomes. Exercise represents an effective therapeutic intervention for preparing patients to successfully complete treatments, for reducing acute, chronic and late side effects, and for improving QOL during and after treatments. This overview of exercise oncology and side-effect management summarizes existing evidence-based exercise guidelines for cancer patients and survivors.

Keywords: Exercise, Physical Activity, Cancer, Side Effects, Quality of Life, Yoga, Tai Chi, Aerobic Exercise, Resistance Exercise, Cancer-Related Fatigue, Bone Loss, Muscle Loss, Mental Health, Cardiotoxicity

INTRODUCTION

Over 1.6 million Americans will be diagnosed with cancer in 2012, adding to the approximately 12 million Americans already living with a diagnosis of cancer.1The vast majority of these cancer patients are receiving or have completed treatment for their disease. The overall survival rate for all types of cancer has increased from less than 50% in 1975 to over 68% in 2012.1Therefore, many Americans with a wide variety of cancers are living beyond the historical 5-year survival marker. The number of cancer survivors will continue to increase with continued improvements in screening and treatment. Despite these improvements, however, many cancer survivors suffer from the acute, chronic, and late side effects of treatment. Acute side effects are those which develop during treatment and last a short time (days, weeks, or months); chronic side effects develop during treatment and persist for months to years, and late side effects arise months or even years after treatments are complete. All of these side effects negatively impact cancer patients and survivors during, immediately following, and long after treatments. Exercise is an effective therapeutic intervention for preparing patients to successfully complete treatments, managing acute, chronic and late side effects and improving quality of life (QOL).

SIDE EFFECTS OF CANCER TREATMENT

Treatments for cancer often include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormone therapy and/or a combination of these modalities. These treatments lead to a myriad of physical and psychological side effects which subsequently interfere with a cancer patient’s ability to complete treatments as prescribed, function independently, perform activities of daily of living, and live with a high quality of life. Side effects are especially burdensome in older adults who are at greatest risk for functional impairment after cancer treatment. Among the most onerousside effects stemming from cancer and its treatments are cancer-related fatigue (CRF), cognitive impairment, sleep problems, depression, pain, anxiety, and physical dysfunction including impaired muscular function, reduced cardiopulmonary function, and decreased bone mineral density.

Cancer-Related Fatigue

CRF is defined as “a distressing, persistent, subjective sense of physical, emotional and/or cognitive tiredness or exhaustion related to cancer or cancer treatment that is not proportional to recent physical activity and interferes with usual functioning.”2 CRF is differentiated from other types of fatigue by the timeline in which it occurs (i.e., after a cancer diagnosis or treatment), its severity and persistence, the inability to alleviate it through rest, and its negative impact on function and overall QOL.3-7 ENREF 3 CRF is the most common symptom experienced by patients and survivors ENREF 84-6,8-21 Patients report CRF from the time of diagnosis through treatment completion and often during the months or years after treatments are complete.5-7,22,23 ENREF 2 Nearly all cancer patients who are undergoing treatment report CRF, and almost half report their CRF as severe.5-7,22CRF is a chronic problem in over two-thirds of cancer survivors, and nearly 40% describe it as severe for at least six months following treatment.5-7,22CRF is more common, more severe, and persistent in patients who receive more than one type of treatment.5-7,22CRF is a dose-limiting toxicity resulting from established therapies and from newer targeted agents (such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors), ultimately limiting their effective use alone and in combination with other agents.24CRF is associated with variety of co-morbidities such as sleep problems, depression, pain, medication side effects, nutritional imbalance, and physical inactivity.5-7,22CRF is often described by patients as the most distressing side effect of treatment, even more so than nausea, vomiting, sleep problems, pain, and depression, due to its impact on their ability to perform activities of daily living and QOL.5-7,22

Cognitive Problems

Cognitive impairments (e.g., problems with memory, attention, and executive function), for which there is no treatment, are a clinically significant problem for up to 75% of breast cancer patients during chemotherapy and persist in 20-35% of survivors during the years following treatment.25-32 Patients receiving chemotherapy have much greater difficulty with cognitive function than patients receiving radiation treatments.33 These cognitive problems can have a severe negative effect on the mental and physical well-being of patients and impair function (e.g., activities of daily living) and QOL. For example, one study found that 57% of women with breast cancer were unable to do their jobs as effectively, unable to maintain the same job, or unable to work at all following chemotherapy due to difficulty with memory, maintaining attention, and accomplishing tasks requiring executive function.29,34

Sleep Problems, Depression, Pain, and Anxiety

Between 30% and 50% of cancer patients report sleep disruption.35 ENREF 36 Poor sleep quality is common among cancer patients and survivors; it is several times more prevalent than in the general population.35,36 Patients and survivors who spend a significant amount of time napping report increased sleep problems.37 Additionally, 10-25% of cancer patients report depression.38 Pain is also common; 45-59% of cancer patients and survivors report pain.39 Anxiety is reported by approximately half of cancer patients and survivors; 20% meet the clinical criteria for an anxiety disorder.40

Physical Dysfunction

Cancer and its treatments can lead to impaired muscle function through atrophy and loss of strength.41,42Reduced muscle mass and strength impair a cancer patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living and remain independent during and following treatment, which is of particular concern among older patients.43,44Chemotherapy and radiation treatments may also lead to cardiac and pulmonary dysfunction.4,5,45Patients treated with anthracyclines, taxanes and/or trastuzumab may develop acute or chronic cardiac dysfunction and, in some cases, the maximum cumulative dose for these agents is limited due to potential cardiomyopathy.46,47 ENREF 49 Cardiotoxicities can develop during treatment or become manifest years after treatment completion.48 Radiation to the chest increases the risk of cardiac damage.49Patients treated with methotrexate and bleomycin may develop pulmonary toxicities.50-53Patients treated with chemotherapy, oophorectomy, and aromatase inhibitors often decrease production of endogenous estrogens and develop premature menopause leading to reduced bone mineral density and an increased risk of fracture.54-56

Aging

Older adults are at a greater risk of developing cancer than those who are younger. In the U.S., approximately 60% of new cancer diagnoses occur in those who are 65 years of age or older.57 Compared to older adults without a history of cancer, older cancer survivors suffer from a greater incidence of frailty and more limitations in activities of daily living, lower self-rated health, reduced QOL, and a greater prevalence of geriatric syndromes such as dementia, depression, falls, incontinence, and osteoporosis.ENREF 4443,44,58

EXERCISE FOR SIDE EFFECT MANAGEMENT

The selection of cancer treatments is based on numerous factors including the type and stage of cancer and the patient’s underlying health status.45The type of cancer, types of treatments, and underlying health status of the cancer patient and survivor influence the development, type and severity of side effects.59-61Exercise is an effective intervention for improving side effects such as CRF, cognitive impairment, sleep problems, depression, pain, anxiety and physical dysfunction including impaired muscular function, cardiopulmonary function and bone density. Exercise can be individually tailored to the specific needs of each cancer patient or survivor.6,7,22,62-100Exercise is an effective behavioral intervention with the potential to mitigate multiple side effects and improve physical function in older cancer patients and survivors as well.101-105

Aerobic Exercise During and Following Treatment

Aerobic exercise utilizes large muscle groups for prolonged periods of time.106Examples of aerobic exercises include walking, running, cycling, and swimming.106Aerobic exercise is an effective intervention for CRF, sleep disruption, depression, anxiety, cardiopulmonary function and QOL among cancer patients and survivors.64,66,71,74,78,82,91,93-95,97-100

Aerobic exercise is beneficial when performed by cancer patients who are undergoing treatment. Mock and colleagues reported that home-based walking at a moderate intensity (50-70% of maximum heart rate), performed for 10 to 45 minutes per day, 4 to 6 days per week, for one to six months, during chemotherapy and radiation treatment for breast cancer reduced CRF, sleep disruption, depression, and anxiety while improving cardiopulmonary function and QOL.84-86,107 ENREF 90 ENREF 90 Another study in female breast cancer patients who were undergoing chemotherapy concurrent with participation in a progressive aerobic exercise intervention showed improvements in anxiety. The exercise intervention began with 3 sessions per week, 15 minutes per session at 60% of VO2peak and progressed to 45-minute sessions at 80% of VO2peak. The patients used a treadmill, cycle ergometer, or elliptical trainer.67

Prostate cancer patients undergoing radiation treatments while participating in a moderate intensity (60-70% maximum heart rate) home-based walking program for 30 minutes a day, 3 days a week for 10 weeks reported improvements in CRF and cardiopulmonary function compared to usual care controls.98Colorectal cancer patients who received chemotherapy and engaged in a moderate intensity walking (65-75% maximum heart rate) and flexibility program for 20 to 30 minutes per day, 3 to 5 days per week showed improvements in CRF, depression, anxiety and cardiopulmonary function. They also reported greater functional, physical, and emotional well-being and higher QOL than controls.66Aerobic exercise has also been shown to improve sleep quality in cancer patients and survivors. Breast cancer survivors receiving hormonal treatment who engaged in a home-based moderate-intensity walking intervention 4 times per week, 20 minutes per day reported improved sleep quality.108

Dimeo and colleagues assessed the benefits of a cycle ergometer exercise intervention in cancer patients who had undergone surgery for lung or gastrointestinal tumors. Patients were prescribed a stationary cycle intervention for 30 minutes per day, 5 days per week, for 3 weeks and reported improvements in CRF, physical performance, and global health.71Dimeo and colleagues performed another cycle ergometer exercise intervention in cancer patients who were receiving high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. The intervention consisted of a moderately intense bed cycle ergometer interval program. Patients performed 1 minute intervals at 50% of heart rate reserve followed by 1 minute of rest, for a total of 30 minutes, 7 days per week. Patients who exercised reported less CRF and psychological stress than usual care controls.70

Aerobic exercise also has beneficial effects following treatment. Breast cancer survivors who had completed treatment were given a moderate intensity cycle ergometer intervention, three times per week for 15 weeks. Sessions were 15 minutes in duration during weeks 1 through 3 and progressed to 35 minutes by weeks 13 through 15. Participants in the exercise group showed significant improvements in cardiopulmonary function and QOL.109

Resistance Exercise During and Following Treatment

Resistance exercise involves muscle contraction against resistance and leads to improvements in muscular function and bone density.106 Resistance can be achieved by using hand-held dumbbells, resistance bands, or even body weight.106Resistance training is safe, reduces side effects, and improves QOL when performed during and following cancer treatment.69,89,90,92,110

During chemotherapy for breast cancer, resistance training, consisting of 2 sets of 8 to 12 repetitions three times per week for the duration of chemotherapy, resulted in an increase in upper and lower body strength and lean body mass when compared to a usual care control group.67Courneya and colleagues also found that breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy were able to tolerate higher relative doses of chemotherapy if engaging in resistance exercise.67

Resistance training is safe and efficacious for breast cancer survivors who have recently completed primary treatment. Schmitz and colleagues implemented a twice weekly resistance training intervention lasting 6 to 12 months. The intervention was safe and resulted in decreased body fat and increased lean body mass.89 Ahmed and colleagues also assessed the safety of resistance training in breast cancer survivors who had recently completed treatment. Twice weekly resistance training, lasting for 6 months, did not result in any change in arm circumference in participants and therefore did not seem to contribute to the development of lymphedema.62Breast cancer survivors who performed moderate intensity resistance training in addition to jump/impact training three times per week for one year benefited from a reduction in fracture risk due to preservation of bone mineral density at the lumbar spine in comparison to a control group. This preservation may be particularly beneficial for breast cancer survivors taking aromatase inhibitors.111A progressive, moderate intensity resistance and impact training intervention, including jumping exercises, preformed 3 times per week for one year was found to preserve bone mineral density in the lumbar spine in breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitors. Resistance training performed 3 days per week for 12 weeks by prostate cancer survivors receiving and rogen deprivation therapy resulted in improved CRF, cognitive function, QOL, and muscular strength.92

Combined Aerobic and Resistance Exercise

Researchers have also assessed the benefits of exercise programs that combine aerobic and resistance exercise on cancer- and treatment-related side effects. Mustian and colleagues showed the combination of aerobic and resistance exercise as part of an individually tailored, 4-week intervention for breast and prostate cancer patients improved CRF, QOL, sleep quality, aerobic capacity, strength and immune function.87,96 Associations between interleukin-6 levels and sleep efficiency and duration suggested that improvements in sleep due to exercise may be mediated by cytokines.96In addition, participants were able to progressively increase the number of steps walked per day from 5,000 to nearly 12,000 despite undergoing radiation treatments.87,96 ENREF 105 A combined aerobic and resistance training intervention performed two days per week for 12 weeks resulted in improved muscle mass, muscular strength, and physical function among prostate cancer survivors undergoing androgen suppression therapy.75Milne and colleagues tested an exercise intervention that combined aerobic and resistance training for 12 weeks and found improved muscular strength and cardiopulmonary function in breast cancer survivors.83A 4-week combined aerobic and resistance exercise intervention in older prostate cancer patients undergoing radiation treatments resulted in improvements in CRF, cardiopulmonary function, and strength.112A phone-based intervention aimed at increasing exercise and improving diet over the course of six months showed promise for improving physical functioning in older cancer patients.113 Unfortunately, very little research has focused on using exercise interventions in older cancer patients or survivors.114

Mindfulness-Based Exercise

Tai Chi Chuan and yoga are mindfulness-based exercise interventions that provide substantial benefits for cancer patients by relieving side effects, improving physical function, and increasing QOL Mustian and colleagues demonstrated that a community-based 12-week, 15-move, Yang style short-form of Tai Chi Chuan improved muscular function, cardiopulmonary function, body composition, QOL, bone metabolism, and immune function among breast cancer survivors.115-119One very recent, non-controlled, feasibility study showed a positive effect of 10 weeks of Tai ChiChuan (2 times/week, 60 minutes/session) on memory, attention, and executive function in cancer survivors, suggesting that exercise may be a promising intervention for cognitive function in this population.120

Joseph and colleagues reported improvements in sleep, QOL, treatment tolerance, and mood, among patients participating in yoga while receiving radiation treatments.121The intervention consisted of a 90-minute session, two times per week, for eight weeks. Yoga postures, breathing, and visualization exercises were used. Cohen and colleagues found less sleep disturbance among lymphoma patients participating in Tibetan yoga once per week for 7 weeks. Patients were receiving treatment or within 12 months following completion of treatment. The Tibetan yoga intervention consisted of one yoga session a week for 7 weeks, focusing on yoga postures, visualization, breathing, and mindfulness.122

Providing Information

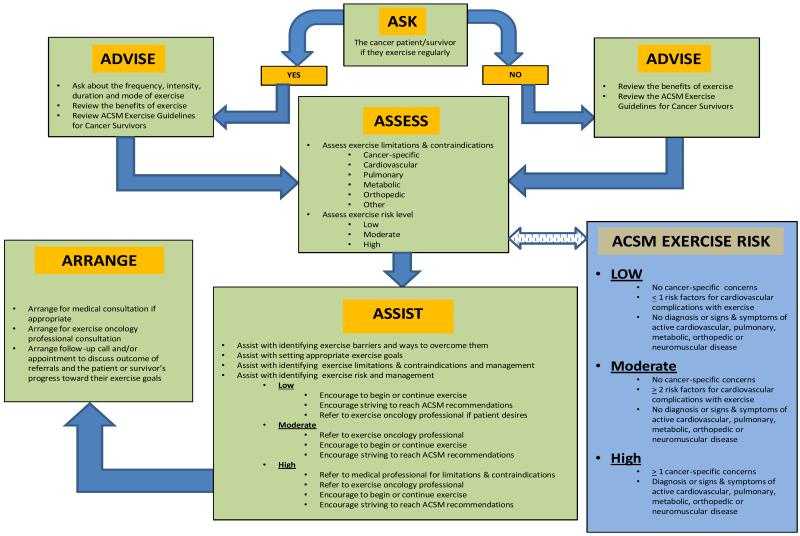

Themajority of cancer patients report that they do not discuss initiating or continuing an exercise program with their treating oncologist or primary care physician throughout their cancer experience.6,123Yet, research shows that cancer patients want their oncologists to initiate discussions about exercise.124Cancer patients would prefer to receive information on exercise during the time period in which they are receiving treatments (i.e., during chemotherapy and during radiation therapy); specifically, they prefer receiving this information shortly after they have initiated treatments and prior to completion.125 Given the benefits of exercise during cancer treatments, oncologists should routinely discuss exercise and physical activity with their patients. The information below, in Figure 1, and in Tables 1 and 2 can help guide these discussions.

Figure 1.

The 5 A’s of Applied Exercise Oncology

Table 1.

Examples of Exercise Limitations , Contraindications and Recommendations Adapted from ACSM Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Suvivors

| Examples of Cancer-Specific Concerns | Examples of Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Extreme fatigue, anemia, and ataxia | Refer to medical specialist and exercise oncology professional to determine if exercise is safe. If determined to be safe, exercise at a low intensity, as tolerated, preferably under the supervision of an exercise oncology professional. |

| Surgery | Allow sufficient time to heal after surgery before commencing exercise. |

| Pain at surgery site | Refer to surgeon and/or physical therapist for clearance prior to exercise. Use exercises that do not involve that area of the body until pain is appropriately managed. |

| Limited mobility at surgery site | Refer to surgeon and/or physical therapist for clearance prior to exercise. Consider physical activity that does not involve that area of the body. |

| Risk of hernia due to ostomy | Avoid contact sports and exercises that increase intra-abdominal pressures. |

| Swelling and lymphedema | Refer to oncologist and physical therapist for clearance prior to exercise. Monitor limb circumference and stop exercise and seek medical evaluation if circumference changes in patients/survivors. Patients at increased risk can wear acompression garment when exercising. |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Refer to neurologist, physical therapist and exercise oncology professional. Monitor closely for balance impairments. Include exercises that improve balance. |

| Cardiovascular toxicities | Refer to cardiologist for and exercise oncology professional to determine if exercise is safe. |

| Compromised immune function | Refer to exercise oncology professional. Prescribe exercise at a low to moderate intensity. Ensure facility is clean to reduce infection risk. |

| Increased fracture risk | Avoid exercises that put excessive stress on bones, including high impact activities. |

Table 2.

Exercise Recommendations Adapted from the ACSM Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Patients and Survivors

| MODE OF EXERCISE | RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

| Aerobic Exercise | Achieve a weekly volume of 150 minutes of moderate intensity exercise or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity exercise, or some combination of the two. |

| Resistance Exercise | Perform strength training exercises 2-3 times per week. Include exercises that target all of the major muscle groups. |

| Flexibility Exercises | Include stretching exercises for all of the major muscle groups on all the days that other exercises are performed. |

|

| |

| Additional Information | Return to normal activity as soon as possible during and following cancer treatment. Some exercise is better than none. Start slowly and progressively increase. Strive to achieve the recommended levels of exercise. See a medical professional if any questions or concerns arise. See an exercise oncology professional for assistance with exercise testing, prescription and monitoring. |

Considerations and Contraindications for Exercise

Oncologists should discuss with cancer patients and survivors how they can safely begin or continue an exercise program during and after treatments. Patients must also be informed of any potential contraindications (e.g., orthopedic, cardiopulmonary, oncologic) that might affect their exercise safety and tolerance.90 Contraindications do not necessarily mean that a cancer patient or survivor cannot exercise at all; in fact, this is rarely the case. In most instances, contraindications simply require specific modifications to the exercise regimen so that the individual can exercise safely and still achieve physical and mental health benefits (See Table 1). Many cancer patients will be able to safely initiate or continue an exercise program with the goal of achieving the levels of exercise, both aerobic and resistance, recommended by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) for cancer patients and survivors.90Active exercisers or those at low to moderate risk, based on the ACSM guidelines, are not required to obtain medical clearance to continue or begin a low to moderate exercise program (See Figure 1).90However, a medical assessment by qualified medical professionals (e.g., oncologist, surgeon, cardiologist, orthopedist, physical therapist) along with appropriate management of cancer-specific, cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, orthopeadic or other co-morbid conditions, is advisable for individuals at moderate risk wishing to participate in vigorous exercise and those at high risk initiating low to moderate intensity exercise, based on the ACSM guidelines.90Cancer survivors should be evaluated for musculoskeletal morbidities, peripheral neuropathies, and fractures if they have received or are currently on hormonal treatments.90 Cancer patients with additional concerns, such as bone metastasis and cardiac toxicity, should be assessed to determine if and how they can safely exercise.90Medical evaluations should be conducted prior to the initiation of exercise testing, prescription and participation. It is strongly suggested that exercise testing, prescription and monitoring be done by qualified exercise professionals, as described in the next section, for all cancer patients and survivors, but, particularly for individuals at moderate risk beginning or continuing vigorous exercise and those at high risk commencing or continuing any level of exercise.90 In all cases, the exercise prescription should be developed to target relevant cancer- and general-health-related outcomes.90

Exercise Professionals

Exercise participation and adherence during and following cancer treatments are increased if physicians are involved in making recommendations and referring patients.126Referral to a qualified exercise specialist is preferred.90 Minimum qualifications include a bachelor’s degree or higher in an accredited exercise science or kinesiology program. Certification as a Cancer Exercise Trainer from the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) further ensures that the exercise professional has the minimum competencies required to safely and effectively prescribe exercise for cancer patients and survivors.90 This certification, which can be obtained by individuals with varied educational backgrounds (e.g., exercise physiologists, physical therapists, nurses), requires training in the unique cancer-specific issues that need to be addressed when a patient or survivor plans to start or continue exercise throughout primary treatment and into long-term survivorship. The certification also provides a very useful professional competency benchmark for oncology professionals who are looking for exercise referral options in their local communities.90,106,127

Exercise Prescription Guidelines

Since cancer survivors are a heterogeneous group, their exercise prescription should be individualized and tailored based on health status, disease trajectory, previous and/or current treatment, current fitness level and past and present exercise participation and preferences in order to be safe and effective.90,128 ENREF 130 Introducing a low to moderate intensity exercise intervention and slowly increasing its frequency, intensity and duration over a period of weeks is recommended.90,106 ENREF 130 In 2010, the ACSM published the “Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors,” a set of evidence-based guidelines developed by a team of expert exercise oncology researchers and clinicians (See Table 2).90These guidelines along with the ACSM Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription provide an excellent starting point for exercise testing, prescription and monitoring among cancer patients and survivors.90,106 ENREF 106 The ACSM Guidelines for Cancer Survivors recommend that cancer patients and survivors slowly progress up to participating in 150 minutes of moderate intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity aerobic exercise weekly plus strength training across all the major muscle groups 2 to 3 times weekly and regular stretching.90,128-130 ENREF 130 The guidelines also suggest that individuals with conditions that limit their ability to perform exercise should participate in physical activity to the fullest extent they are able, even if they are unable to achieve the recommended levels.90,129,130

Results from clinical trials that focus on the use of exercise for improving cancer-related outcomes are also helpful to health professionals when testing, prescribing and monitoring exercise behavior and results. Research suggests that moderately intense exercise interventions (55–75% of heart rate maximum, corresponding to a rating of perceived exertion between 11 and 14131), including aerobic exercise ranging from 10–90 minutes in duration, 3–7 days/week, are consistently effective for managing side effects and improving QOL among cancer survivors with an early-stage diagnosis.7,68,87,132Cancer survivors with ataxia or balance difficulties may benefit most from stationary cycling as a mode of physical exercise.90Accumulating 30 minutes of daily activity through short bouts of exercise(3-10 minutes), with rest in between, can also reduce side effects and improve QOL.90 ENREF 6 Moderate to vigorously intense resistance exercise performed 3 times per week and progressively increasing up to 2-4 sets ranging from 8-15 repetitions is effective at reducing side effects and improving QOL among cancer survivors.62,67,89,92,111Mindfulness-based modes of exercise such as yoga and Tai Chi Chuan performed 1-3 times a week for 60-90 minutes at a moderate intensity level can also reduce side effects and improve QOL.115-120

Low intensity exercise is also safe and well-tolerated by cancer patients with metastatic disease.133-138Lymphedema risk can be reduced by use of compression sleeves when appropriate, although recent research suggests that resistance training does not result in increased incidence of lymphedema.90Generally, it is prudent to advise cancer patients and survivors to avoid excessive high-intensity exercise which can compromise the immune system and interfere with treatment and recovery.90

SUMMARY

The exercise oncology literature provides consistent support for the safety and efficacy of exercise interventions in managing cancer- and treatment-related side effects as well as improving QOL in cancer patients and survivors. This area of research, however, is still in its infancy, and limitations do exist. Small sample sizes, a lack of consistency in the type and dose of exercise utilized, and methodological concerns make it difficult to generalize published findings to the diverse cancer population. Additionally, comparisons based on the dose and mode of exercise are challenging due to a lack of appropriate statistical and follow-up analyses (e.g., intent-to-treat analyses in randomized controlled trials). Despite these limitations, preliminary evidence consistently indicates that that physical activity is not only safe but beneficial for cancer patients and survivors for the management of multiple side effects associated with cancer and cancer treatments. Overall, research suggests that aerobic exercise, resistance training, a combination of both, and mindfulness forms of exercise such as yoga and Tai Chi Chuan are effective in helping cancer patients cope with their disease, improve recovery, and increase overall QOL.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Reference List

- 1.Cancer Facts & Figures. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mock V, Atkinson A, Barsevick A, et al. NCCN Practice Guidelines for Cancer-Related Fatigue. Oncology. 2000;14:151–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan JL, Carroll JK, Ryan EP, et al. Mechanisms of cancer-related fatigue. The oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):22–34. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD, et al. Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. The oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):4–10. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrow GR. Cancer-related fatigue: causes, consequences, and management. The oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):1–3. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mustian KM, Griggs JJ, Morrow GR, et al. Exercise and side effects among 749 patients during and after treatment for cancer: a University of Rochester Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program Study. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2006;14:732–41. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0912-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mustian KM, Morrow GR, Carroll JK, et al. Integrative nonpharmacologic behavioral interventions for the management of cancer-related fatigue. The oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):52–67. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langeveld N, Ubbink M, Smets E. ‘I don’t have any energy’: The experience of fatigue in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. European journal of oncology nursing : the official journal of European Oncology Nursing Society. 2000;4:20–8. doi: 10.1054/ejon.1999.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2000;342:326–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cella D, Davis K, Breitbart W, et al. Cancer-related fatigue: prevalence of proposed diagnostic criteria in a United States sample of cancer survivors. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:3385–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forlenza MJ, Hall P, Lichtenstein P, et al. Epidemiology of cancer-related fatigue in the Swedish twin registry. Cancer. 2005;104:2022–31. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, et al. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a systematic review. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2007;34:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theunissen JM, Hoogerbrugge PM, van Achterberg T, et al. Symptoms in the palliative phase of children with cancer. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2007;49:160–5. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butt Z, Rosenbloom SK, Abernethy AP, et al. Fatigue is the most important symptom for advanced cancer patients who have had chemotherapy. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2008;6:448–55. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2008.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minton O, Stone P. How common is fatigue in disease-free breast cancer survivors? A systematic review of the literature. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2008;112:5–13. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9831-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hockenberry-Eaton M, Hinds PS, Alcoser P, et al. Fatigue in children and adolescents with cancer. Journal of pediatric oncology nursing : official journal of the Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses. 1998;15:172–82. doi: 10.1177/104345429801500306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinds PS, Hockenberry-Eaton M, Gilger E, et al. Comparing patient, parent, and staff descriptions of fatigue in pediatric oncology patients. Cancer nursing. 1999;22:277–88. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199908000-00004. quiz 288-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies B, Whitsett SF, Bruce A, et al. A typology of fatigue in children with cancer. Journal of pediatric oncology nursing : official journal of the Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses. 2002;19:12–21. doi: 10.1053/jpon.2002.30012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson F, Garnett M, Richardson A, et al. Heavy to carry: a survey of parents’ and healthcare professionals’ perceptions of cancer-related fatigue in children and young people. Cancer nursing. 2005;28:27–35. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perdikaris P, Merkouris A, Patiraki E, et al. Changes in children’s fatigue during the course of treatment for paediatric cancer. International nursing review. 2008;55:412–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitsett SF, Gudmundsdottir M, Davies B, et al. Chemotherapy-related fatigue in childhood cancer: correlates, consequences, and coping strategies. Journal of pediatric oncology nursing : official journal of the Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses. 2008;25:86–96. doi: 10.1177/1043454208315546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mustian KM, Peppone LJ, Palesh OG, et al. Exercise and Cancer-related Fatigue. US oncology. 2009;5:20–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vogelzang NJ, Breitbart W, Cella D, et al. Patient, caregiver, and oncologist perceptions of cancer-related fatigue: results of a tripart assessment survey. The Fatigue Coalition. Seminars in hematology. 1997;34:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cornelison M, Jabbour EJ, Welch MA. Managing side effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy to optimize adherence in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: the role of the midlevel practitioner. The journal of supportive oncology. 2012;10:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janelsins M, Roscoe JA, Jean-Pierre P, Morrow GR. Cognitive Functioning in Breast Cancer Patients During and Following Chemotherapy. Supplement to American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;47 Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brezden CB, Phillips KA, Abdolell M, et al. Cognitive function in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2695–701. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.14.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, Furstenberg CT, et al. Neuropsychologic impact of standard-dose systemic chemotherapy in long-term survivors of breast cancer and lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:485–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Dam FS, Schagen SB, Muller MJ, et al. Impairment of cognitive function in women receiving adjuvant treatment for high-risk breast cancer: high-dose versus standard-dose chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:210–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wefel JS, Lenzi R, Theriault RL, et al. The cognitive sequelae of standard-dose adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast carcinoma: results of a prospective, randomized, longitudinal trial. Cancer. 2004;100:2292–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, McDonald BC, et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Cognitive Changes Associated With Adjuvant Treatment for Breast Cancer: Impact of Age and Cognitive Reserve. J Clin Oncol. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jansen CE, Dodd MJ, Miaskowski CA, et al. Preliminary results of a longitudinal study of changes in cognitive function in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. Psychooncology. 2008;17:1189–95. doi: 10.1002/pon.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janelsins MC, Kohli S, Mohile SG, et al. An update on cancer- and chemotherapy-related cognitive dysfunction: current status. Semin Oncol. 2011;38:431–8. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kohli S, Griggs JJ, Roscoe JA, Jean-Pierre P, Bole C, Mustian KM, Hill R, Smith K, Gross H, Morrow GR. Self-Reported Cognitive Impairments in Patients With Cancer. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2007;3:54–59. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0722001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Bednarek HL, et al. Short-term effects of breast cancer on labor market attachment: results from a longitudinal study. J Health Econ. 2005;24:137–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savard J, Morin CM. Insomnia in the context of cancer: a review of a neglected problem. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:895–908. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palesh OG, Roscoe JA, Mustian KM, et al. Prevalence, demographics, and psychological associations of sleep disruption in patients with cancer: University of Rochester Cancer Center-Community Clinical Oncology Program. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:292–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ancoli-Israel S, Moore PJ, Jones V. The relationship between fatigue and sleep in cancer patients: a review. European journal of cancer care. 2001;10:245–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2001.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pirl WF, Roth AJ. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in cancer patients. Oncology. 1999;13:1293–301. discussion 1301-2, 1305-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M, et al. Symptom and quality of life survey of medical oncology patients at a veterans affairs medical center: a role for symptom assessment. Cancer. 2000;88:1175–83. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000301)88:5<1175::aid-cncr30>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stark D, Kiely M, Smith A, et al. Anxiety disorders in cancer patients: their nature, associations, and relation to quality of life. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:3137–48. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tisdale MJ. Cachexia in cancer patients. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2002;2:862–71. doi: 10.1038/nrc927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tisdale MJ. The ‘cancer cachectic factor’. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2003;11:73–8. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0408-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohile SG, Fan L, Reeve E, et al. Association of cancer with geriatric syndromes in older Medicare beneficiaries. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:1458–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.6695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mohile SG, Xian Y, Dale W, et al. Association of a cancer diagnosis with vulnerability and frailty in older Medicare beneficiaries. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2009;101:1206–15. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA. Cancer, principles & practice of oncology. ed 7th Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Allen A. The cardiotoxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs. Seminars in oncology. 1992;19:529–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA. Cancer : principles & practice of oncology : breast cancer. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yeh ET. Cardiotoxicity induced by chemotherapy and antibody therapy. Annual review of medicine. 2006;57:485–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sardaro A, Petruzzelli MF, D’Errico MP, et al. Radiation-induced cardiac damage in early left breast cancer patients: Risk factors, biological mechanisms, radiobiology, and dosimetric constraints. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willenbacher W, Mumm A, Bartsch HH. Late pulmonary toxicity of bleomycin. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16:3205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jacka MJ, Chan CK. Pulmonary toxicity associated with bleomycin. The Medical journal of Australia. 1995;162:220–1. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb126032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lateef O, Shakoor N, Balk RA. Methotrexate pulmonary toxicity. Expert opinion on drug safety. 2005;4:723–30. doi: 10.1517/14740338.4.4.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cannon GW. Methotrexate pulmonary toxicity. Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America. 1997;23:917–37. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bruning PF, Pit MJ, de Jong-Bakker M, et al. Bone mineral density after adjuvant chemotherapy for premenopausal breast cancer. British journal of cancer. 1990;61:308–10. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1990.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shuster LT, Gostout BS, Grossardt BR, et al. Prophylactic oophorectomy in premenopausal women and long-term health. Menopause international. 2008;14:111–6. doi: 10.1258/mi.2008.008016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, et al. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years’ adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:60–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17666-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Balducci L. Epidemiology of cancer and aging. J Oncol Manag. 2005;14:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baker F, Haffer SC, Denniston M. Health-related quality of life of cancer and noncancer patients in Medicare managed care. Cancer. 2003;97:674–81. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hofman M, Morrow GR, Roscoe JA, et al. Cancer patients’ expectations of experiencing treatment-related side effects: a University of Rochester Cancer Center--Community Clinical Oncology Program study of 938 patients from community practices. Cancer. 2004;101:851–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Side effects of prostate cancer treatment. Health News. 1998;4:7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hoskins CN. Breast cancer treatment-related patterns in side effects, psychological distress, and perceived health status. Oncology nursing forum. 1997;24:1575–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ahmed RL, Thomas W, Yee D, et al. Randomized controlled trial of weight training and lymphedema in breast cancer survivors. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:2765–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baumann FT, Zopf EM, Bloch W. Clinical exercise interventions in prostate cancer patients--a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012;20:221–33. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1271-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bicego D, Brown K, Ruddick M, et al. Effects of exercise on quality of life in women living with breast cancer: a systematic review. The breast journal. 2009;15:45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2008.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Campbell A, Mutrie N, White F, et al. A pilot study of a supervised group exercise programme as a rehabilitation treatment for women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant treatment. European journal of oncology nursing : the official journal of European Oncology Nursing Society. 2005;9:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Quinney HA, et al. A randomized trial of exercise and quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. European journal of cancer care. 2003;12:347–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2003.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Gelmon K, et al. Six-month follow-up of patient-rated outcomes in a randomized controlled trial of exercise training during breast cancer chemotherapy. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2007;16:2572–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Mackey JR, et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:4396–404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cramp F, James A, Lambert J. The effects of resistance training on quality of life in cancer : a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2010;18:1367–76. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0904-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dimeo FC, Stieglitz RD, Novelli-Fischer U, et al. Effects of physical activity on the fatigue and psychologic status of cancer patients during chemotherapy. Cancer. 1999;85:2273–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dimeo FC, Thomas F, Raabe-Menssen C, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise and relaxation training on fatigue and physical performance of cancer patients after surgery. A randomised controlled trial. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2004;12:774–9. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0676-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Duijts SF, Faber MM, Oldenburg HS, et al. Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors--a meta-analysis. Psycho-oncology. 2011;20:115–26. doi: 10.1002/pon.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Friedenreich CM. Physical activity and breast cancer: review of the epidemiologic evidence and biologic mechanisms. Recent results in cancer research. Fortschritte der Krebsforschung. Progres dans les recherches sur le cancer. 2011;188:125–39. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-10858-7_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Galvao DA, Newton RU. Review of exercise intervention studies in cancer patients. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:899–909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Galvao DA, Taaffe DR, Spry N, et al. Combined resistance and aerobic exercise program reverses muscle loss in men undergoing androgen suppression therapy for prostate cancer without bone metastases: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:340–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ingram C, Courneya KS, Kingston D. The effects of exercise on body weight and composition in breast cancer survivors: an integrative systematic review. Oncology nursing forum. 2006;33:937–47. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.937-950. quiz 948-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jones LW, Peppercom J, Scott JM, et al. Exercise therapy in the management of solid tumors. Current treatment options in oncology. 2010;11:45–58. doi: 10.1007/s11864-010-0121-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Knols R, Aaronson NK, Uebelhart D, et al. Physical exercise in cancer patients during and after medical treatment: a systematic review of randomized and controlled clinical trials. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:3830–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Knols RH, de Bruin ED, Shirato K, et al. Physical activity interventions to improve daily walking activity in cancer survivors. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:406. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Loprinzi PD, Cardinal BJ. Effects of physical activity on common side effects of breast cancer treatment. Breast Cancer. 2012;19:4–10. doi: 10.1007/s12282-011-0292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lowe SS. Physical activity and palliative cancer care. Recent results in cancer research. Fortschritte der Krebsforschung. Progres dans les recherches sur le cancer. 2011;186:349–65. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-04231-7_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McNeely ML, Campbell KL, Rowe BH, et al. Effects of exercise on breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne. 2006;175:34–41. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Milne HM, Wallman KE, Gordon S, et al. Effects of a combined aerobic and resistance exercise program in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2008;108:279–88. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9602-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mock V, Dow KH, Meares CJ, et al. Effects of exercise on fatigue, physical functioning, and emotional distress during radiation therapy for breast cancer. Oncology nursing forum. 1997;24:991–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mock V, Frangakis C, Davidson NE, et al. Exercise manages fatigue during breast cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Psycho-oncology. 2005;14:464–77. doi: 10.1002/pon.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mock V, Pickett M, Ropka ME, et al. Fatigue and quality of life outcomes of exercise during cancer treatment. Cancer practice. 2001;9:119–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.009003119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mustian KM, Peppone L, Darling TV, et al. A 4-week home-based aerobic and resistance exercise program during radiation therapy: a pilot randomized clinical trial. The journal of supportive oncology. 2009;7:158–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pekmezi DW, Demark-Wahnefried W. Updated evidence in support of diet and exercise interventions in cancer survivors. Acta oncologica. 2011;50:167–78. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.529822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Hannan PJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of weight training in recent breast cancer survivors to alter body composition, insulin, and insulin-like growth factor axis proteins. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2005;14:1672–80. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2010;42:1409–26. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schmitz KH, Holtzman J, Courneya KS, et al. Controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2005;14:1588–95. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Segal RJ, Reid RD, Courneya KS, et al. Resistance exercise in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:1653–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Segar ML, Katch VL, Roth RS, et al. The effect of aerobic exercise on self-esteem and depressive and anxiety symptoms among breast cancer survivors. Oncology nursing forum. 1998;25:107–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Speck RM, Courneya KS, Masse LC, et al. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice. 2010;4:87, 100. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Spence RR, Heesch KC, Brown WJ. Exercise and cancer rehabilitation: a systematic review. Cancer treatment reviews. 2010;36:185–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sprod LK, Palesh OG, Janelsins MC, et al. Exercise, sleep quality, and mediators of sleep in breast and prostate cancer patients receiving radiation therapy. Community oncology. 2010;7:463–471. doi: 10.1016/s1548-5315(11)70427-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Stevinson C, Lawlor DA, Fox KR. Exercise interventions for cancer patients: systematic review of controlled trials. Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2004;15:1035–56. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-1325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Windsor PM, Nicol KF, Potter J. A randomized, controlled trial of aerobic exercise for treatment-related fatigue in men receiving radical external beam radiotherapy for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101:550–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Winters-Stone KM, Schwartz A, Nail LM. A review of exercise interventions to improve bone health in adult cancer survivors. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice. 2010;4:187–201. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wolin KY, Ruiz JR, Tuchman H, et al. Exercise in adult and pediatric hematological cancer survivors: an intervention review. Leukemia : official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, U.K. 2010;24:1113–20. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Morey MC, et al. Lifestyle intervention development study to improve physical function in older adults with cancer: outcomes from Project LEAD. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3465–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.7224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.LaStayo PC, Marcus RL, Dibble LE, et al. Eccentric exercise versus usual-care with older cancer survivors: the impact on muscle and mobility--an exploratory pilot study. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Morey MC, Snyder DC, Sloane R, et al. Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: RENEW: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301:1883–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Courneya KS, Vallance JKH, McNeely ML, et al. Exercise issues in older cancer survivors. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2004;51:249–61. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rao AV, Cohen HJ. Fatigue in older cancer patients: etiology, assessment, and treatment. Seminars in oncology. 2008;35:633–42. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.American College of Sports Medicine. Thompson WR, Gordon NF, et al. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. ed 8th Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mock V, Burke MB, Sheehan P, et al. A nursing rehabilitation program for women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncology nursing forum. 1994;21:899–907. discussion 908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Payne JK, Held J, Thorpe J, et al. Effect of exercise on biomarkers, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and depressive symptoms in older women with breast cancer receiving hormonal therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:635–42. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.635-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Bell GJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of exercise training in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: cardiopulmonary and quality of life outcomes. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:1660–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.De Backer IC, Schep G, Backx FJ, et al. Resistance training in cancer survivors: a systematic review. International journal of sports medicine. 2009;30:703–12. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1225330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Winters-Stone KM, Dobek J, Nail L, et al. Strength training stops bone loss and builds muscle in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: a randomized, controlled trial. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2011;127:447–56. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1444-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mustian K, Peppone L, Sprod L, Janelsins M, Trevino L, Gewandter J, Chandwani K, Heckler C, Morrow G. EXCAP©® Exercise Improves Fatigue, Cardiopulmonary Function and Strength: A Randomized, Controlled Phase II Clinical Trial Among Prostate Cancer Patients Receiving Radiation and Androgen Therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology Supplement. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 113.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Morey MC, et al. Lifestyle intervention development study to improve physical function in older adults with cancer: outcomes from Project LEAD. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:3465–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.7224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Courneya KS, Vallance JK, McNeely ML, et al. Exercise issues in older cancer survivors. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2004;51:249–61. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sprod LK, Janelsins MC, Palesh OG, et al. Health-related quality of life and biomarkers in breast cancer survivors participating in tai chi chuan. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice. 2012;6:146–54. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0205-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Janelsins MC, Davis PG, Wideman L, et al. Effects of Tai Chi Chuan on insulin and cytokine levels in a randomized controlled pilot study on breast cancer survivors. Clinical breast cancer. 2011;11:161–70. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Peppone LJ, Mustian KM, Janelsins MC, et al. Effects of a structured weight-bearing exercise program on bone metabolism among breast cancer survivors: a feasibility trial. Clinical breast cancer. 2010;10:224–9. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2010.n.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mustian KM, Katula JA, Zhao H. A pilot study to assess the influence of tai chi chuan on functional capacity among breast cancer survivors. The journal of supportive oncology. 2006;4:139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mustian KM, Katula JA, Gill DL, et al. Tai Chi Chuan, health-related quality of life and self-esteem: a randomized trial with breast cancer survivors. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2004;12:871–6. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0682-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Reid-Arndt SA, Matsuda S, Cox CR. Tai Chi effects on neuropsychological, emotional, and physical functioning following cancer treatment: a pilot study. Complementary therapies in clinical practice. 2012;18:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Joseph CD. Psychological supportive therapy for cancer patients. Indian journal of cancer. 1983;20:268–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Cohen L, Warneke C, Fouladi RT, et al. Psychological adjustment and sleep quality in a randomized trial of the effects of a Tibetan yoga intervention in patients with lymphoma. Cancer. 2004;100:2253–60. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jones LW, Courneya KS. Exercise discussions during cancer treatment consultations. Cancer practice. 2002;10:66–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.102004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yates JS, Mustian KM, Morrow GR, et al. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer patients during treatment. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2005;13:806–11. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0770-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sprod LK, Peppone LJ, Palesh OG, Janelsins MC, Heckler CE, Colman LK, Kirshner JJ, Bushunow PW, Morrow GR, Mustian KM. Timing of information on exercise impacts exercise behavior during cancer treatment (N=748): A URCC CCOP protocol. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28 [Google Scholar]

- 126.Jones LW, Courneya KS, Fairey AS, et al. Effects of an oncologist’s recommendation to exercise on self-reported exercise behavior in newly diagnosed breast cancer survivors: a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;28:105–13. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2802_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Doyle C, Kushi LH, Byers T, et al. Nutrition and physical activity during and after cancer treatment: an American Cancer Society guide for informed choices. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2006;56:323–53. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.6.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee report, 2008. To the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Part A: executive summary. Nutrition reviews. 2009;67:114–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2007;39:1423–34. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616b27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;116:1081–93. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 1982;14:377–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, et al. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293:2479–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Crevenna R, Schmidinger M, Keilani M, et al. Aerobic exercise for a patient suffering from metastatic bone disease. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2003;11:120–2. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0400-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Headley JA, Ownby KK, John LD. The effect of seated exercise on fatigue and quality of life in women with advanced breast cancer. Oncology nursing forum. 2004;31:977–83. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.977-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Porock D, Kristjanson LJ, Tinnelly K, et al. An exercise intervention for advanced cancer patients experiencing fatigue: a pilot study. Journal of palliative care. 2000;16:30–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Oldervoll LM, Loge JH, Paltiel H, et al. The effect of a physical exercise program in palliative care: A phase II study. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2006;31:421–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Adamsen L, Midtgaard J, Rorth M, et al. Feasibility, physical capacity, and health benefits of a multidimensional exercise program for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2003;11:707–16. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Oldervoll LM, Loge JH, Lydersen S, et al. Physical exercise for cancer patients with advanced disease: a randomized controlled trial. The oncologist. 2011;16:1649–57. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]