Abstract

A series of easily prepared, phosphine-ligated palladium precatalysts based on the 2-aminobiphenyl scaffold have been prepared. The role of the precatalyst-associated labile halide (or pseudohalide) in the formation and stability of the palladacycle has been examined. It was found that replacing the chloride in the previous version of the precatalyst with a mesylate leads to a new class of precatalysts with improved solution stability and that are readily prepared from a wider range of phosphine ligands. The differences between the previous version of precatalyst and that reported here are explored. In addition, the reactivity of the latter is examined in a range of C-C and C-N bond forming reactions.

Introduction

Over the past thirty years palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions have become powerful tools for generating carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom bonds.1,2 Key to the success of such couplings is the efficient generation of a phosphine-ligated Pd(0) species to enter into the catalytic cycle. Common commercially available Pd(0) sources such as Pd2(dba)3 and Pd(PPh3)4 contain ligands that can interfere with the reaction.3 Commercial Pd2(dba)3 has also recently been shown to contain varying amounts of Pd nanoparticals and free dba.4 To avoid this problem, Pd(II) sources, such as Pd(OAc)2 and PdCl2, are sometimes used, though these must be reduced in-situ. Often the efficiency of these reductions is inadequate for a wide range of coupling reactions.

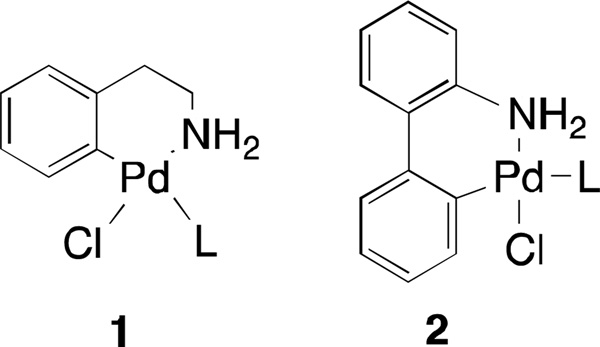

Recently, solutions to the problem of catalyst activation have taken the form of readily activated palladium precatalysts. Many such systems have been reported, including the pyridine-stabilized NHC precatalysts (PEPPSI)5, ligated allylpalladium chloride precatalysts,6 imine-derived precatalysts7, and the palladacycle-based precatalysts 1 and 2 previously reported by our group (Figure 1).8,9 Each of these species is a pre-ligated air and moisture stable Pd(II) source, which forms a ligated Pd(0) species in-situ when exposed to base.

Figure 1.

Related precatalysts8–9 previously reported by the MIT group

While both MIT chemists and the Merck Process Group have successfully employed palladacyclic precatalysts in various transformations, those previously reported versions still suffer from drawbacks. For example, the first reported synthesis of 1 required three steps and involved the handling of organometallic intermediates. Recently, Vicente reported a deft alternative procedure for the synthesis of 1, which involved a C-H activation/cyclopalladation sequence starting from Pd(OAc)2.10,11,12 However this procedure also required the use of triflic acid and an additional ion exchange step.

In 2010 we developed a class of biarylamine-derived precatalysts 2 as a more convenient alternative to 1. A similar C-H activation/cyclopalladation sequence, as discovered by Albert,13,14 also provides access to precatalyst 2 in a one-pot procedure from Pd(OAc)2 which does not require the handling of any organometallic intermediates. Precatalysts of type 2, however, cannot be generated with larger ligands such as tBuXPhos and BrettPhos. Additionally, these precatalysts are not stable in solution for extended periods of time. Thus, access to a precatalyst system with enhanced stability and broader range of ligands would be highly desirable. Herein we report the development of a series of novel precatalysts based on a cyclopalladated 2-aminobiphenylmesylate backbone.

Results and Discussion

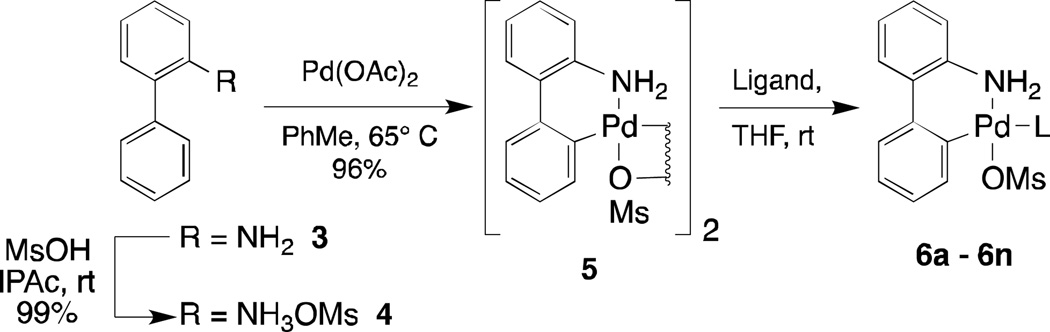

We postulated that precatalysts related to 2 that incorporated larger ligands might be accessible by rendering the Pd(II) center more electron-poor via replacement of the chloride with a more electron-withdrawing species. Additionally, we thought that a non-coordinating anion could allow for the incorporation of larger ligands by making the palladium center less sterically encumbered. After evaluating a variety of halides and pseudohalides, it was ultimately found that palladium precatalysts that are analogues of 2 with the chloride replaced by a methanesulfonate group (Scheme 1, 6a – 6n) could be readily prepared with both BrettPhos and tBuXPhos. Moreover, this new class of precatalyst allowed us to meet our secondary goal: to retain the ease of preparation and stability of precatalysts of general structure 2. As detailed in Scheme 1, μ-OMs dimer 5 is generated in high yield from commercially available 2-aminobiphenyl 3 via a sequence involving mesylate salt formation and cyclopalladation. To demonstrate the practicality of this process, the reaction was performed with 315 grams of mesylate salt 4 to afford 417 grams μ-OMs 5 (96% yield) after isolation directly from the reaction mixture. Reactions of a wide array of synthetically important ligands with μ-OMs 5 in THF or dichloromethane proceed smoothly (15 – 45 minutes) to afford the desired palladacycle precatalyst 6.

Scheme 1.

Preparation of Mesylate Precatalysts

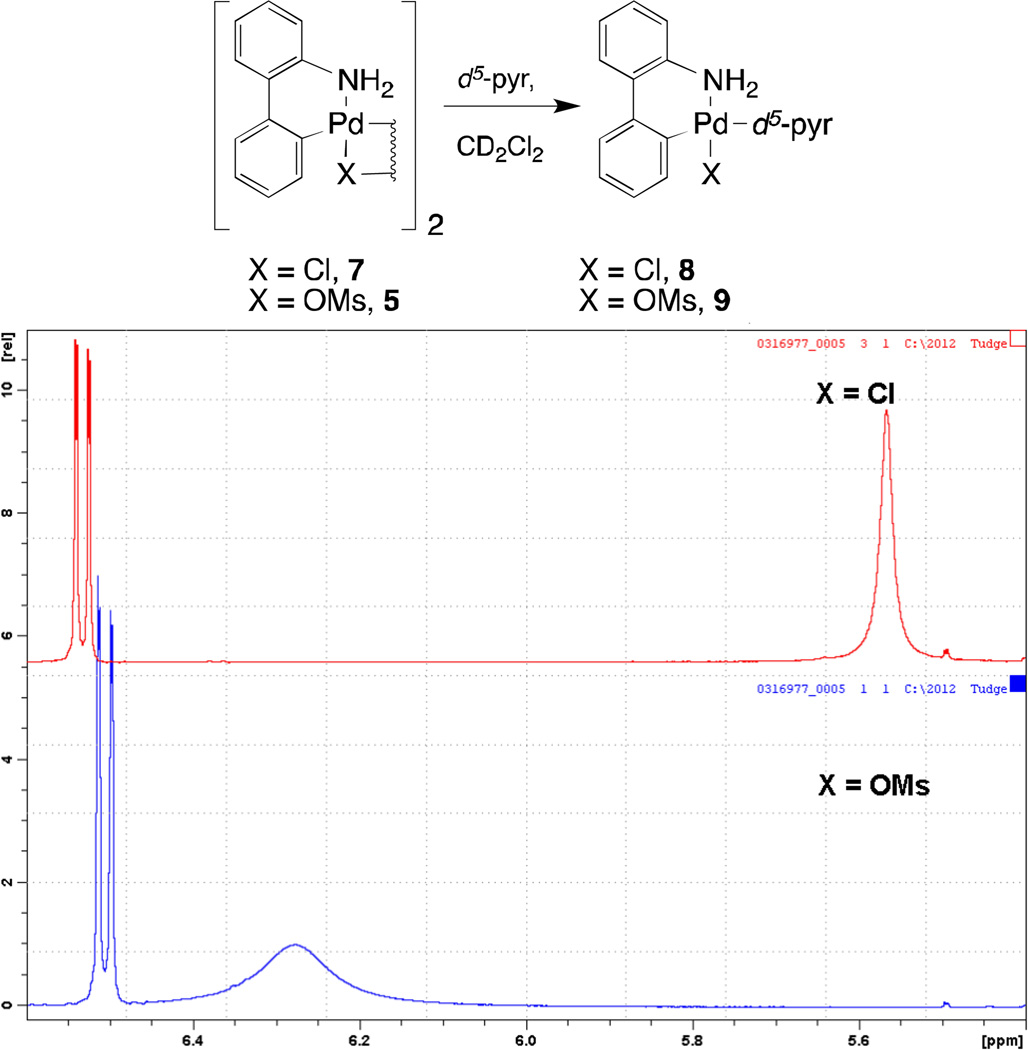

Because of their versatility and broad applicability as ligands for palladium-catalyzed reactions, L1 – L14 (Figure 2) were selected as an ideal set of ligands to test for compatibility with our mesylate precatalyst structure 6. We found that all of the ligands in combination with 5 afforded precatalysts 6a – 6n in excellent yields with short reaction times. In fact, due to their high solubility and fast rate of formation, precatalysts 6a – 6n can also be prepared and used in-situ, directly from μ-OMs dimer 5. This operationally facile process should allow for rapid testing of an array of ligands for a desired chemical transformation using a single palladium precursor.

Figure 2.

Ligands from which precatalyst 6 was prepared and isolated yields of precatalysts

To date the only ligands that have proven difficult to incorporate into this precatalyst system are the extremely bulky phosphines tBuBrettPhos and RockPhos, partially due to their propensity to rearrange when coordinated to Pd(II).15

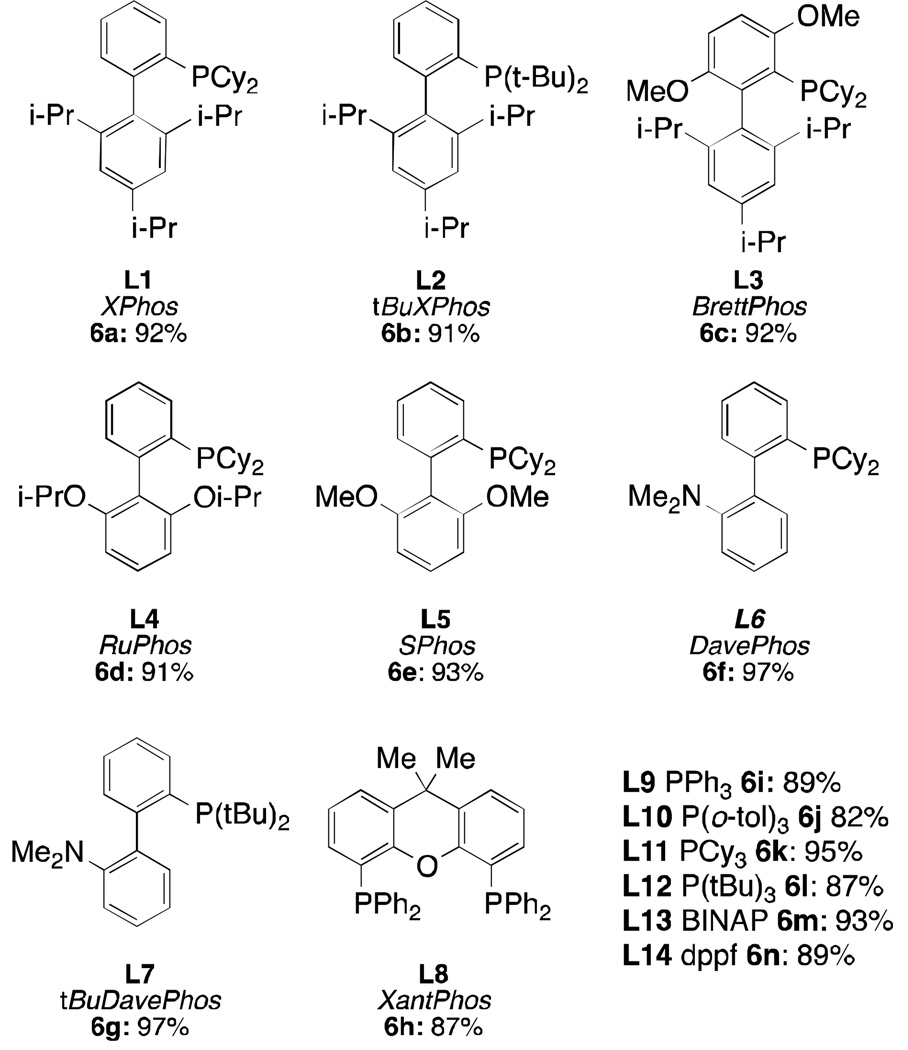

In order to investigate the role of the mesylate anion leading to the broader scope of ligands that can be incorporated into precatalysts 6, we carried out 1H NMR studies of d5-pyridine complexes derived from μ-dimers 5 and 7. As shown in Figure 3, treatment of 0.05 mmol samples of μ-dimers 5 and 7 with 10 µL of d5-pyridine in 0.75 mL CD2Cl2 afforded the d5-pyridine complexes 8 and 9 in situ. The resonance for the NH2 group of complex 9 is shifted downfield by 0.76 ppm units relative to that of complex 8, suggesting a more electron deficient palladium center is present in 9.

Figure 3.

1H spectra of in-situ generated 8 and 9 showing a downfield shift of the amine protons of 0.76 ppm for 9 relative to 8.

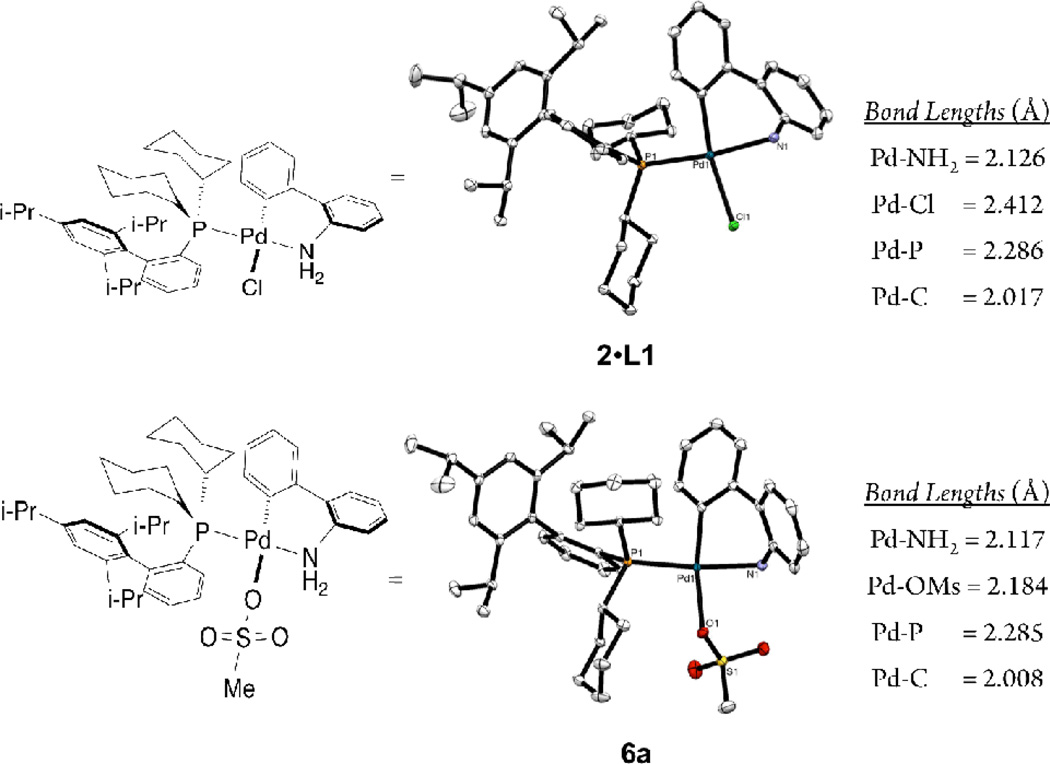

Single crystal X-ray crystal structures of precatalyst 2 with L1 as the supporting ligand, 2•L1, 2 with BINAP as the supporting ligand, 2•L13, and precatalysts 6a, 6b, 6c and 6m provide additional structural evidence suggesting enhanced electrophilicity of the palladium mesylate center. All of these complexes feature a tetracoordinate palladium (II) center with slightly distorted square planar geometries. In the case of 2•L1, 6a, 6b, and 6c the 2-aminobiphenyl ligand chelates the palladium center and in each species the phosphine ligand is in the cis conformation relative to the aryl moiety of the 2-aminobiphenyl carbon bound to palladium. It is also worth noting that in each of these species the corresponding Pd-P, Pd-N and Pd-C bond lengths are nearly identical to each other between the four complexes. In 2•L1 and 6a the chloride and mesylate anions are bound to palladium with bond lengths of 2.412 Å and 2.184 Å respectively (figure 4). While the two species are structurally very similar, preliminary in-silico studies indicate that the palladium center in 6a is a more electron deficient species.16

Figure 4.

Crystallographically-determined X-ray structure representations of 6a and 2•L1 and relevant bond lengths (thermal ellipsoid plot at 50% probability, hydrogen atoms are omitted)

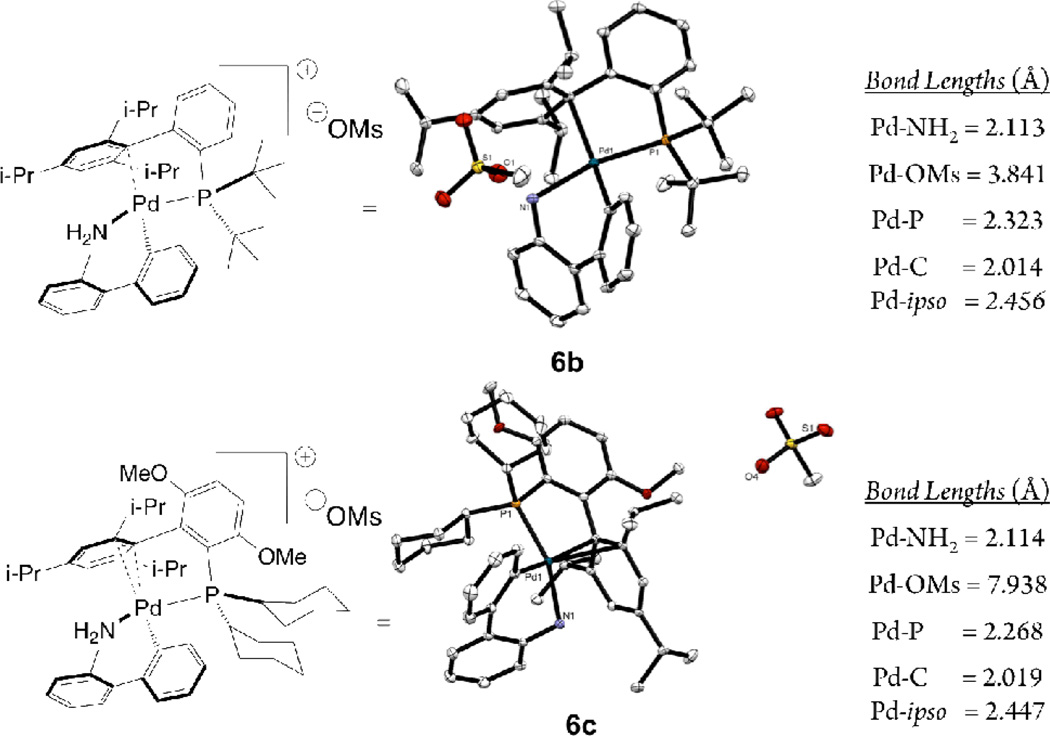

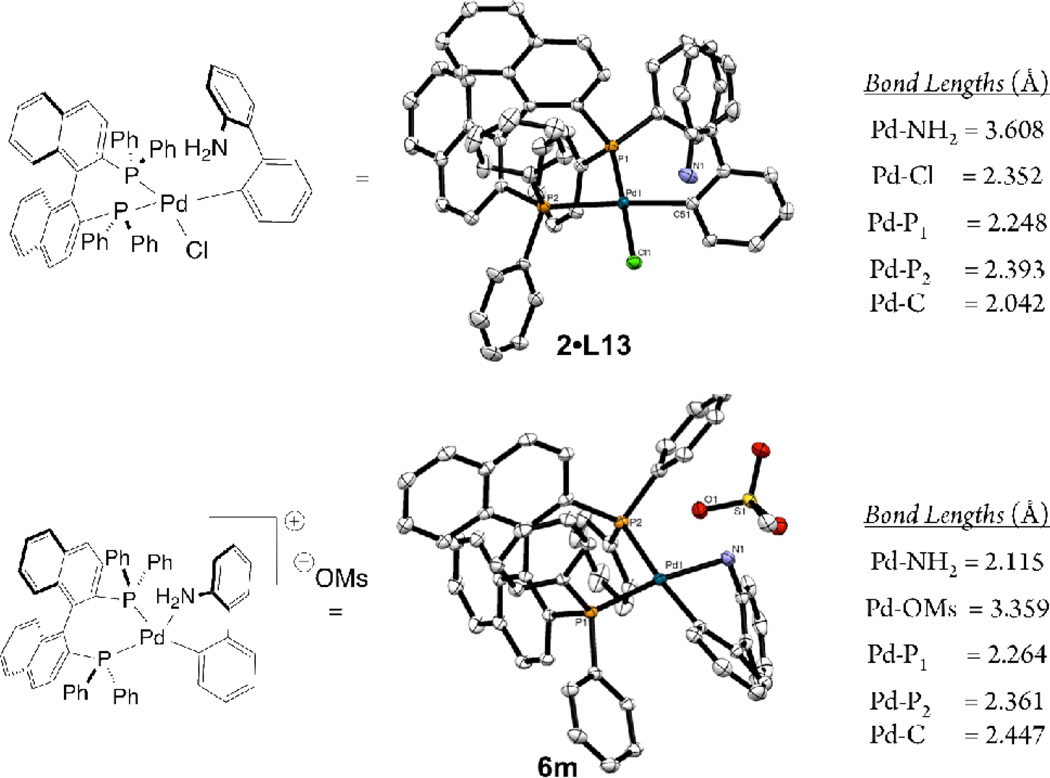

The differences between 2 and 6 are pronounced in chelating bis-phosphines. In 6m both phosphines of the BINAP ligand are coordinated to the palladium center with the mesylate anion dissociated (Pd-O bond distance = 3.359 Å) (Figure 6). This is in contrast to 2•L13, where chloride ligand does not dissociate and remains bound to the palladium center, while the amine moiety of the 2-aminobiphenyl ligand is displaced by one of the phosphine groups of the BINAP ligand. That one of the phosphines of BINAP and the 2-amino group are hemilabile in 2•L13 is seen in its 31P NMR spectrum in chloroform, where two rapidly exchanging species (one sharp doublet at 15 ppm (JP-P = 15.3) and a broad singlet at 36 ppm) are observed.

Figure 6.

Crystallographically-determined X-ray structure representations of 6b and 6c and relevant bond lengths (thermal ellipsoid plot at 50% probability, hydrogen atoms are omitted)

Examining the structures of 6b and 6c, precatalysts of which the analogous 2 cannot be made (Figure 6), the mesylate anion dissociates from palladium, allowing the palladium center to accommodate the very bulky ligands L2 and L3. To occupy the fourth coordination site left vacant by the dissociated mesylate the palladium coordinates to the ipso carbon of the of the triisopropylphenyl ring. It is likely that 6 can accommodate these larger ligands while 2 cannot due to the inability of the chloride to dissociate from the palladium center while the mesylate anion can.

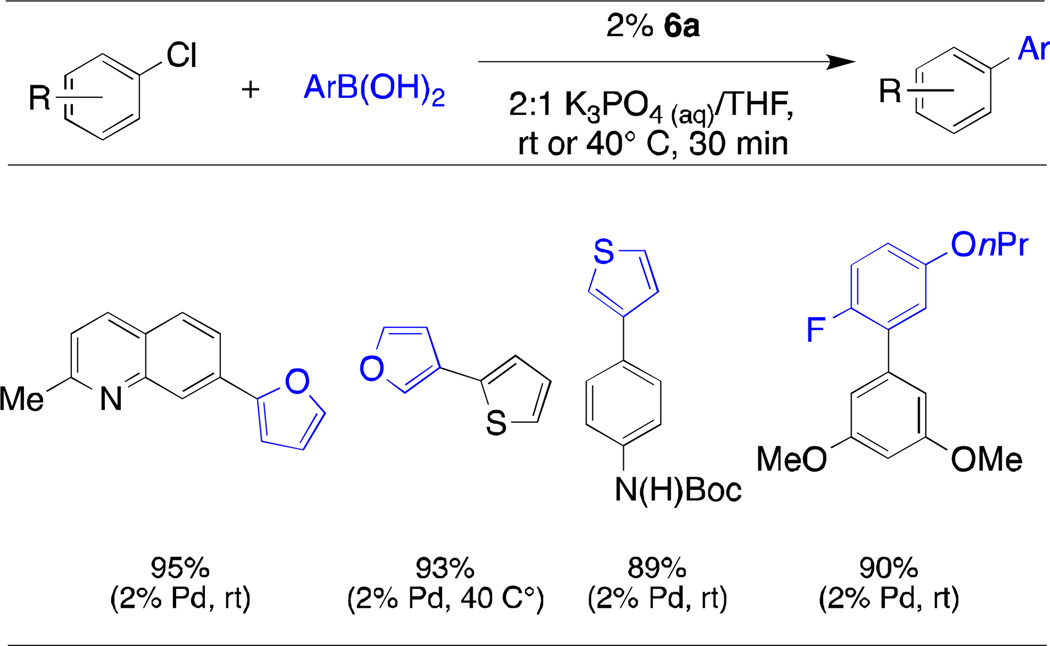

With a series of mesylate precatalysts 6 in hand, we examined their efficiency in various cross-coupling reactions. Biaryl phosphine ligand L1 (XPhos) has seen application in a broad range of transition metal-catalyzed C-C and C-N bond forming processes.17–19 To test the utility of XPhos precatalyst 6a, we evaluated its performance in the Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of unstable boronic acids that are extremely prone to protodeboronation.9 The success of this coupling process, as reported, was dependent on the extremely fast activation of the XPhos precatalyst of type 2 at room temperature in conjunction with its high level of catalytic activity. With the analogous XPhos-derived mesylate precatalyst 6e, unstable boronic acids could be coupled with electron-rich, sterically-hindered, and heteroaryl chlorides under mild conditions (rt → 40° C) with short reaction times (30 minutes) and in high yields similar to the previously reported results (Table 1).

Table 1.

Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling of Unstable Boronic Acids with 6aa

|

aryl chloride (1 mmol), boronic acid (1.5 mmol), precatalyst 6a (2%), THF (2 mL), 0.5 M K3PO4 (4 mL);

average isolated yield of two runs

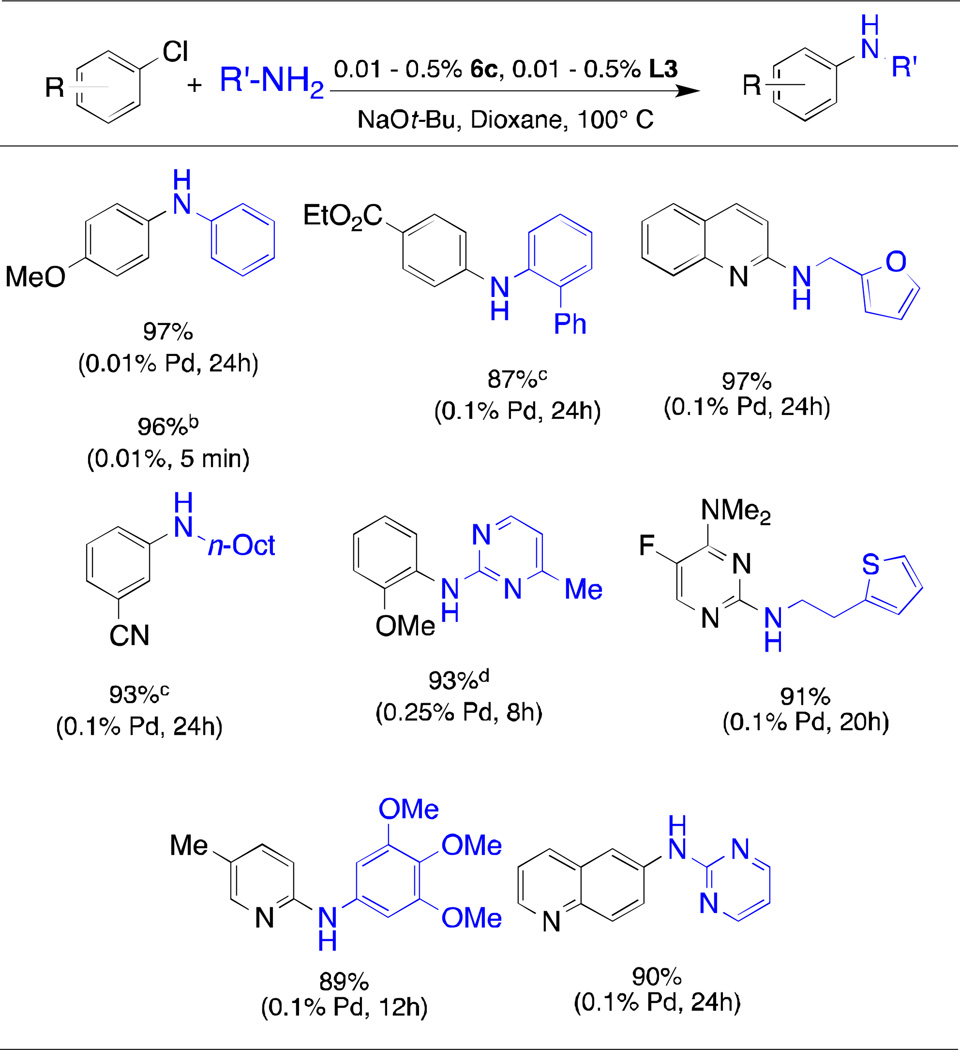

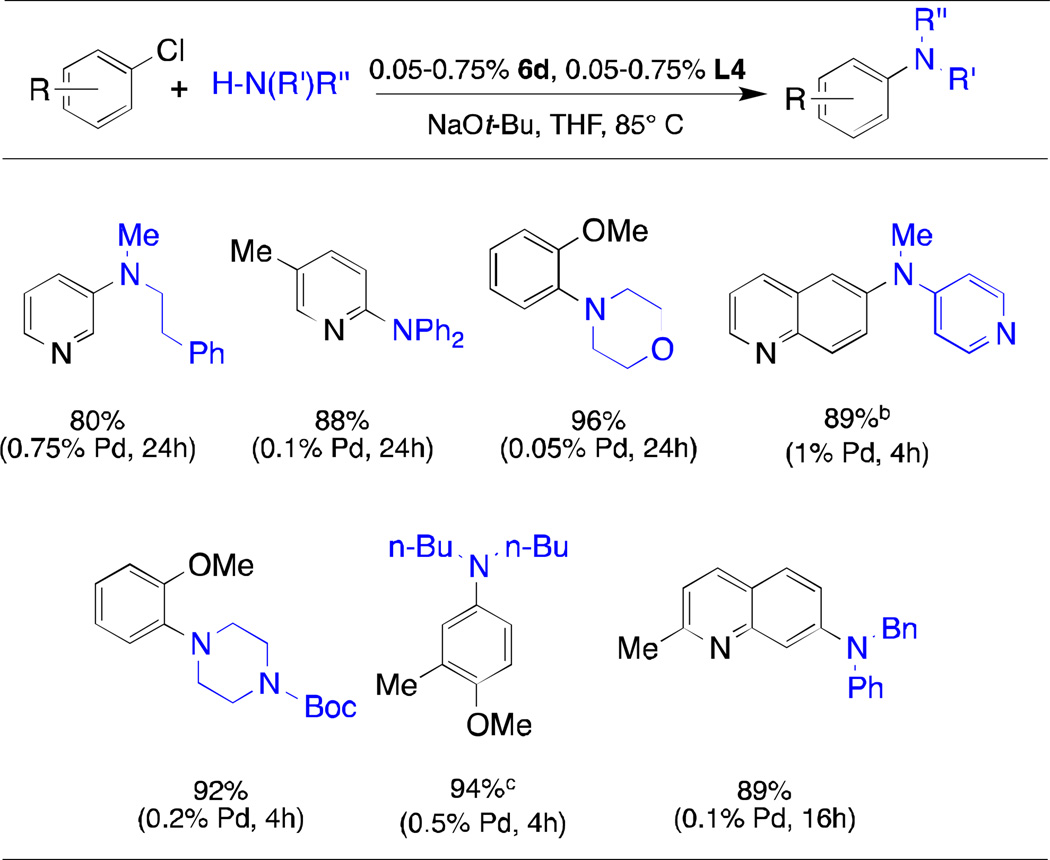

The t-butyl-substituted version of L1, L2 (tBuXPhos), has also been utilized in a range of transformations including vinyl trifluoromethylations,20 α-arylations,21 the amination of heteroaryl halides,22 and arylation of sulfonamides.23 In 2008 the Palladium-catalyzed C-N coupling reactions are powerful tools in both industry and academia. Recent work by our group has shown L3 and L4 to be highly efficient supporting ligands for Pd in the coupling of primary amines and secondary amines, respectively.24–26 Novel palladacycle precatalysts 6c and 6d are also extremely effective in the coupling of primary (Table 3) and secondary (Table 4) amines with aryl halides, even at very low catalyst loadings, and display activity comparable to that of the previous generation precatalysts of type 1 and 2 (for L4).

Table 3.

Arylation of Primary Amines with 6c/L3a

|

aryl chloride (1 mmol), amine (1.2 mmol), NaOt-Bu, (1.2 mmol), 6c (0.01 – 0.5%), L3 (0.01 – 0.5%), dioxane (1 mL) 100 °C;

aryl iodide (1 mmol), amine (1.4 mmol), NaOt-Bu, (1.4 mmol), toluene (1 mL) 100 °C;

Cs2CO3 was used as the base;

t-BuOH was used as the solvent;

Average isolated yields of two runs

Table 4.

Arylation of Secondary Amines with 6e/L5a

|

aryl chloride (1 mmol), amine (1.2 mmol), NaOt-Bu, (1.2 mmol), THF (1 mL) 85 °C;

6a/L1 is used;

ArBr is used;

average isolated yields of two runs

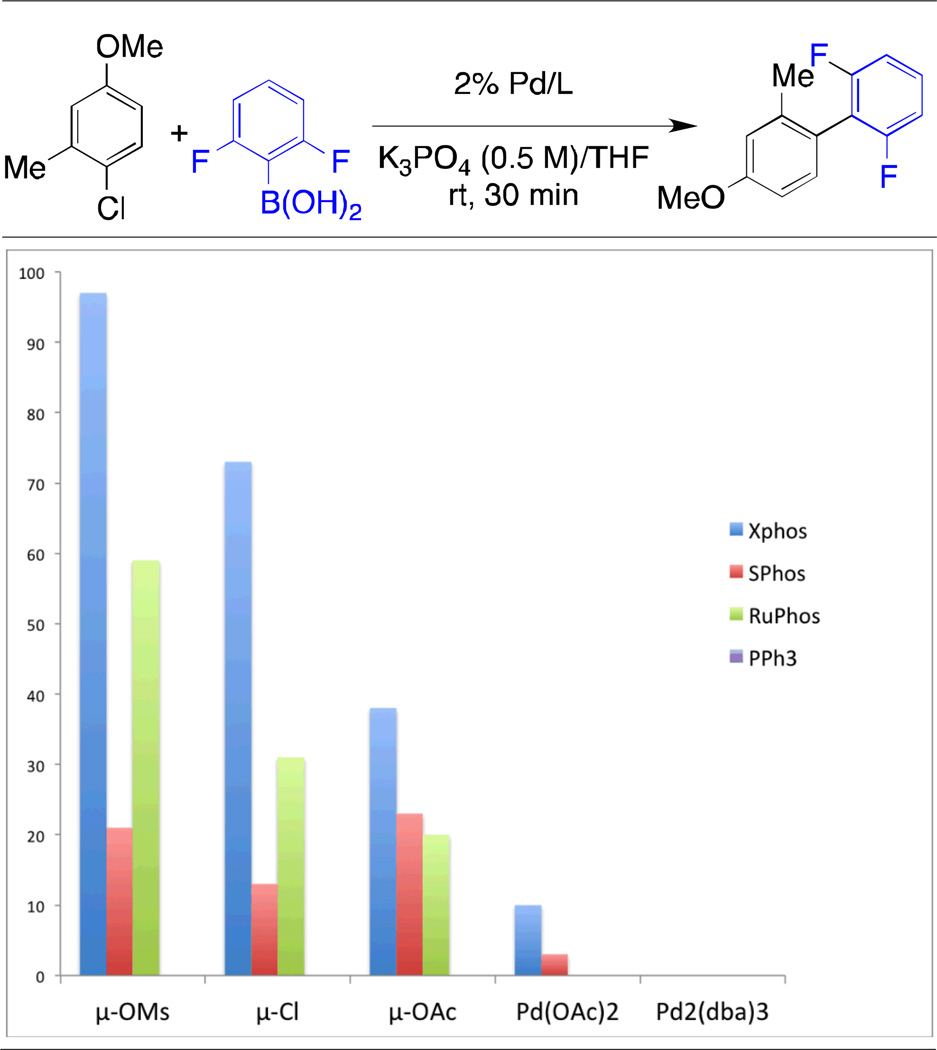

As previously stated, precatalysts 6a – 6n can be rapidly generated in situ from μ-OMs dimer 5 and directly used in palladium-catalyzed reactions with activity comparable to that of the isolated precatalysts. This method could facilitate the expedient determination of optimal conditions for a palladium-catalyzed reaction. To evaluate this process, the Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of 4-chloro-3-methylanisole and 2, 6-difluorophenylboronic acid was chosen as a model reaction. As depicted in Table 5, the coupling was examined with SPhos, RuPhos, XPhos and triphenylphosphine as supporting ligands and with the μ-Cl, μ-OMs, μ-OAc dimers, as well as Pd(OAc)2 and Pd2(dba)3 as palladium sources. Vials of palladium source and ligand were aged for ten minutes in 1 mL of THF and directly added to a reaction tube containing the aryl halide and boronic acid, followed by the addition of base. The results of this study clearly indicate that XPhos is the optimal ligand for this transformation, with the catalyst based on RuPhos also showing moderate activity. The μ-OMs dimer is optimal as the palladium source, with the chloride and acetate dimers showing some activity. The use of Pd(OAc)2 and Pd2(dba)3 under these conditions provided little product.

Table 5.

Screening of Ligands and Palladium Sources for in-situ Precatalyst Generation in the Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling of an Unstable Boronic Acida

|

1 mol % Pd, 1 mol % ligand aged 10 min in 1 mL THF, ArCl (0.50 mmol), boronic acid (0.75 mmol), K3PO4 (aq) (1.0 mmol, 0.5 M), rt, 30 min

Conclusions

In conclusion we have developed a new series of palladium precatalysts based on the 2-aminobiphenyl mesylate palladacycle 5. These precatalysts can be prepared with a broad range of phosphine ligands in a facile and straightforward way and can be activated under mild conditions to generate the desired LPd(0) species. These precatalysts are all obtained in high yields from common intermediate 5, which can be synthesized from readily available starting materials in a three-step process, which avoids rigorous Schlenk techniques. We anticipate that these precatalysts will considerably improve the scope of palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions.

Supplementary Material

Figure 5.

Crystallographically-determined X-ray structure representations of 2•L13 and 6m and relevant bond lengths (thermal ellipsoid plot at 50% probability, hydrogen atoms are omitted)

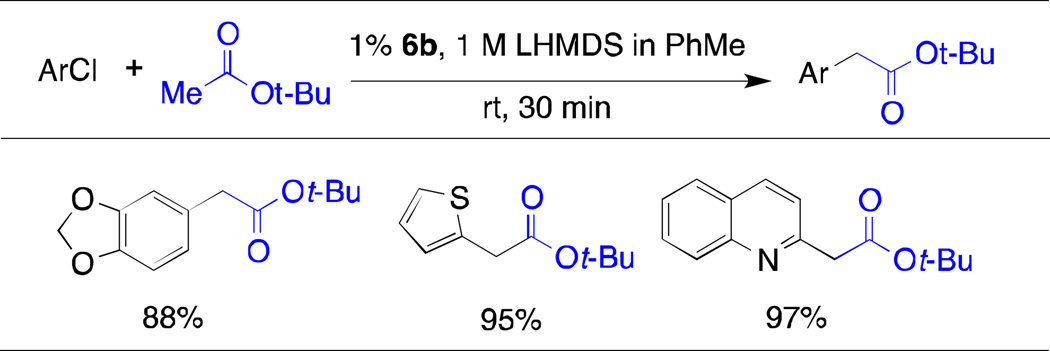

Table 2.

Arylation of t-Butyl Acetate Catalyzed by 6b at Room Temperaturea

|

aryl chloride (0.5 mmol), tBuOAc (0.75 mmol), 1 M LHMDS in PhMe (1.5 mL), 6b (1 mol %),

average isolated yield of two runs

Acknowledgements

This activity was supported, in part, by an educational donation provided by Amgen for which we are grateful. We thank the National Institutes of Health for financial support (GM46059 and GM58160). We thank Sigma-Aldrich for a gift of BrettPhos and Johnson Matthey for a gift of Pd2(dba)3. We thank Dr. Peter Müller for X-ray structural analysis. We also thank Dr. Meredith McGowan for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript and Dr. Alex Spokoyny for helpful discussions. The Varian 300 MHz NMR instrument used for portions of this work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Grants CHE 9808061 and DBI 9729592).

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Procedural, spectral and X-ray crystallographic (CIF) data. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Contributor Information

Matthew T. Tudge, Email: matthew_tudge@merck.com.

Stephen L. Buchwald, Email: sbuchwal@mit.edu.

Notes and references

- 1.Martin R, Buchwald SL. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1461–1473. doi: 10.1021/ar800036s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartwig JF. Nature. 2008;41:314–322. doi: 10.1038/nature07369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amatore C, Broeker G, Jutand A, Khalil F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:5176–5185. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zalesskiy SS, Ananikov VP. Organometallics. 2012;31:2302–2309. [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Brien CJ, Kantchev EB, Valente C, Hadei N, Chass GA, Lough A, Hopkinson AC, Organ M. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:4743–4748. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chartoire A, Lesieur M, Slawin AMZ, Nolan SP, Cazin CS. Organometallics. 2011;30:4432–4436. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedford RB, Cazin CSJ, Coles SJ, Gelbrich T, Horton PN, Hursthouse MB, Light ME. Organometallics. 2003;22:987–999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biscoe MR, Fors BP, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6686–6687. doi: 10.1021/ja801137k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinzel T, Zhang Y, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14073–14075. doi: 10.1021/ja1073799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vicente J, Saura-Llamas I, Olivia-Madrid M, Garcia-Lopez J. Organometallics. 2011;30:4624–4631. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vicente J, Saura-Llamas I. Comment Inorg. Chem. 2007;28:39–72. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vicente J, Saura-Llamas I, Cuadrado J, Ramírez de Arellano M. Organometallics. 2003;22:5513–5517. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albert J, D’Andrea L, Granell J, Zafrilla J, Font-Bardia M, Solans X. J. Organomet. Chem. 2005;690:422–429. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albert J, D’Andrea L, Granell J, Zafrilla J, Font-Bardia M, Solans X. J. Organomet. Chem. 2007;692:4895–4902. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maimone TJ, Milner PJ, Kinzel T, Zhang Y, Takase MK, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18106–18109. doi: 10.1021/ja208461k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preliminary DFT calculations show 6a to be 0.05 charge units more electropositive than 2•L1. See supporting information

- 17.Barluenga J, Moriel P, Valdes C, Aznar F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:5587–5590. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen HN, Huang X, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11818–11819. doi: 10.1021/ja036947t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson KW, Tundel RE, Ikawa T, Altman RA, Buchwald SL. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:6523–6527. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho EJ, Buchwald SL. Org. Lett. 2011;13:6552–6555. doi: 10.1021/ol202885w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biscoe MR, Buchwald SL. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1173–1175. doi: 10.1021/ol900295u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang X, Anderson KW, Zim D, Jiang L, Klapars A, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:6653–6655. doi: 10.1021/ja035483w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosen BR, Ruble JC, Beauchamp TJ, Navarro A. Org. Lett. 2011;13:2564–2567. doi: 10.1021/ol200660s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Surry D, Buchwald SL. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:27–50. doi: 10.1039/C0SC00331J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maiti D, Fors BP, Henderson J, Buchwald SL. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:57–68. doi: 10.1039/C0SC00330A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartwig J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1534–1544. doi: 10.1021/ar800098p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.