Abstract

During a scrub typhus outbreak investigation in Thailand, 4 isolates of O. tsutsugamushi were obtained and established in culture. Phylogenetic analysis based on the 56-kDa type-specific antigen gene demonstrated that the isolates fell into 4 genetic clusters, 3 of which had been previously reported and 1 that represents a new genotype.

Keywords: scrub typhus, Orientia tsutsugamushi, outbreak investigation, parasites, trombiculid mites, chiggers, small mammals, mammal reservoirs, rodents, transmission vector, Thailand, zoonoses, bacteria

Scrub typhus is a febrile disease endemic to the Asia–Australia–Pacific region, where ≈1 million cases occur annually (1). The causative agent of scrub typhus in this region is the gram-negative obligate intracellular bacterium Orientia tsutsugamushi (2). The bacterium maintains itself in trombiculid mites, and small mammals serve as reservoir hosts in the natural life cycle of the mites. Chiggers, the larval stage of mites, act as the transmission vector for O. tsutsugamushi (1). Humans and small animals become infected following the bite of chiggers harboring O. tsutsugamushi. After an incubation period of 7–14 days, high fever, chills, headache, rash, and an eschar usually develop in infected persons (3).

Scrub typhus is endemic to northern Thailand, especially Chiang Mai Province, where >200 cases are reported each year (4). During June 2006–May 2007, a total of 142 febrile children with clinically suspected scrub typhus were admitted to Nakornping Hospital in the city of Chiang Mai. Serologic and molecular laboratory test results showed that 65 of the children were positive for O. tsutsugamushi. Among the 142 hospitalized children, 30 were Hmong hill tribe people living in Ban Pongyeang, a village in the mountain area located north of the Chiang Mai. Laboratory testing also confirmed that 26 of the 30 Hmong children had scrub typhus.

To better characterize the specific strain(s) of O. tsutsugamushi present in the area and to determine how the agent(s) is transmitted to humans, we genetically typed O. tsutsugamushi obtained from these 26 children and small mammals. The Royal Thai Army Medical Department Ethical Committee approved all procedures (protocol S014q/45). Small mammals were handled according to guidelines in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health publication no. 85–23, revised 1985).

The Study

We obtained clinical information and blood samples from 26 scrub typhus–infected children from Ban Pongyeang after their parents gave informed consent. Blood specimens were stored in liquid nitrogen and shipped on dry ice to the Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences in Bangkok, Thailand, for serologic testing, genetic characterization, and isolation of O. tsutsugamushi.

We assessed serum samples for the presence of antibodies against O. tsutsugamushi by using an indirect fluorescence antibody assay (5) with an in-house antigen preparation from propagated O. tsutsugamushi Karp, Kato, and Gilliam strains. Single specimens with an IgM or IgG titer >400 were considered positive; paired specimens were considered positive if they showed seroconversion or a >4-fold rise in titer (6). To genetically characterize O. tsutsugamushi, we amplified a fragment of the 56-kDa type-specific antigen gene from patients’ blood genomic DNA by using a modified nested PCR procedure as described (7). A newly designed forward primer (F584, 5′-CAA TGT CTG CGT TGT CGT TGC-3′) was used with the previously reported reverse primers RTS9 and RTS8 (7). The expected 693-bp products were purified, directly sequenced, and aligned according to ClustalW algorithm (www.clustal.org/). Using PAUP 4.0b10 software and maximum parsimony methods, we generated phylogenetic relationships (8). O. tsutsugamushi was isolated by using animal inoculation and L-929 mouse fibroblast cell culture techniques as described (9).

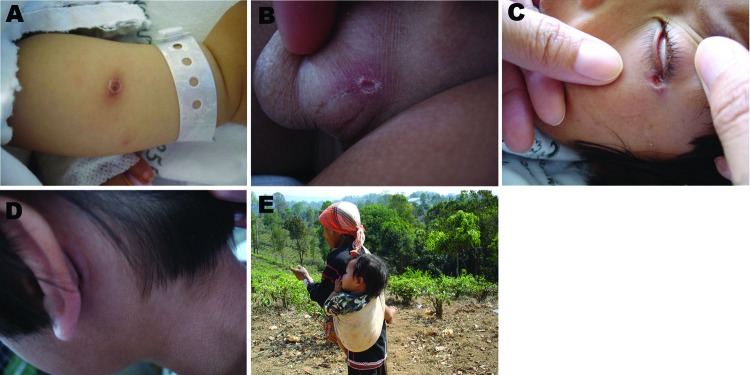

Patient clinical information and laboratory test results are shown in the Technical Appendix. The patients’ ages ranged from 11 months to 13 years. Common signs and symptoms of illness were fever (100.0%), chills (73.1%), eschar (73.1%), headache (57.7%), and rash (23.1%) (Technical Appendix; Figure 1). Of the 26 patients, 23 showed seroreactivity to O. tsutsugamushi antigens; PCR confirmed the presence of O. tsutsugamushi DNA in 24/26 patients (Technical Appendix). Two O. tsutsugamushi isolates (PYH1 and PYH4) were successfully established from EDTA whole blood samples of 7 patients (Technical Appendix). Patient histories revealed that the infected children commonly played in grassland, woods, and rice fields. Cases also occurred in infants who were carried on their mother’s back during work in those areas (Figure 1E). In addition, the opportunity to become infected was increased by frequent exposure to vector mites living in vegetation-rich areas.

Figure 1.

Eschars in different body areas of children with scrub typhus (A–D) and a child carried on his mother’s back during work (E), Ban Pongyeang, Thailand.

To investigate O. tsutsugamushi transmission, we trapped small mammals from different terrains in Ban Pongyeang, identified them to species level, and collected tissue specimens (whole blood, liver, and spleen). The specimens were kept in liquid nitrogen and delivered to the Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences for laboratory testing. Chiggers were removed from captured mammals and stored in 70% ethanol. The chiggers were slide-mounted and identified to species by using a microscope.

A total of 55 small wild mammals were captured from different terrains in Ban Pongyeang, such as grass, rice, and banana fields and areas with shrubs and woods. The collected animals included greater bandicoot rats (Bandicota indica), Savile's bandicoot rats (B. savilei), black rats (Rattus rattus), small white-tooth rats (R. berdmorei), Polynesian rats (R. exulans), Berdmore's ground squirrels (Menetes berdmorei), a common tree shrew (Tupaia glis), and a small Asian mongoose (Herpestes javanicus) (Table 1).

Table 1. Chigger infestation and Orientia tsutsugamushi infection in small mammals captured in Ban Pongyeang, northern Thailand, 2006–2007*.

| Rodent family, genus species | No. animals captured | No. (%) animals infested with chiggers | No. chiggers collected (mean no./animal) | No. (%) animals with O. tsutsugamushi infection | No. (%) O. tsutsugamushi isolates obtained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muridae | |||||

| Bandicota indica | 15 | 15 (100.0) | 951 (63.4) | 15 (100.0) | 2 (22.2) |

| B. savilei | 12 | 12 (100.0) | 699 (58.2) | 9 (75.0) | 0 |

| Rattus rattus | 15 | 8 (55.6) | 320 (21.3) | 8 (53.3) | 0 |

| R. exulans | 3 | 1 (50.0) | 40 (5.0) | 1 (33.3) | 0 |

|

R. berdmorei

|

6 |

4 (66.6) |

168 (28.0) |

3 (50.0) |

0 |

| Viverridae, Herpestes javanicus | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 7 (7.0) | ND | NA |

| Sciuridae, Menetes berdmorei | 2 | 2 (100.0) | 56 (28.0) | ND | NA |

| Tupaiidae, Tupaia glis | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 41 (41.0) | ND | NA |

| Total | 55 | 45 (81.8) | 2,277 (44.4) | 36 (65.5) | 2 (3.6) |

*ND, not done; NA, not applicable.

Forty-five (81.8%) mammals were infested with a total of 2,277 chiggers (Table 1). A B. indica and a B. savilei rat had the highest chigger densities. Collected chiggers were classified to 4 species: Leptotrombidium deliense (47.6%; a well-known vector of scrub typhus), Gahrliepia (Walchia) rustica (35.1%), G. (Schoengastiella) ligula (14.6%), and Ascoschoengastia spp. (2.7%) (Table 2).

Table 2. Species of chiggers collected from small mammals, Ban Pongyeang, northern Thailand, 2006–2007.

| Host species | No. (%) chiggers |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leptotrombidium deliense | Gahrliepia (Walchia) rustica | Gahrliepia (Schoengastiella) ligula | Ascoschoengastia spp. | ||

| Bandicota indica | 471 (49.5) | 324 (34.1) | 131 (13.8) | 25 (2.6) | 951 |

| Bandicota savilei | 354 (50.7) | 223 (31.9) | 105 (15.0) | 17 (2.4) | 699 |

| Rattus rattus | 125 (39.1) | 119 (37.2) | 56 (17.4) | 20 (6.3) | 320 |

| Rattus exulans | 28 (70.0) | 12 (30.0) | 0 | 0 | 40 |

| Rattus berdmorei | 52 (31.0) | 80 (47.6) | 31 (18.5) | 5 (2.9) | 168 |

| Tupaia glis | 15 (36.6) | 17 (41.5) | 9 (21.9) | 0 | 41 |

| Menetes berdmorei | 32 (57.1) | 24 (42.9) | 0 | 0 | 56 |

|

Herpestes javanicus

|

7 (100.0) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| Total | 1,084 (47.6) | 799 (35.1) | 332 (14.6) | 62 (2.7) | 2,277 |

Thirty-six (65.5%) of 51 animals tested were seroreactive to O. tsutsugamushi (Table 1). Compared with the other animals, a higher percentage (100%) of B. indica rats had O. tsutsugamushi infections, indicating that this species might serve as a reservoir host for the bacterium (Table 1). Because of limitations of commercial secondary antibodies, we could not perform indirect fluorescence antibody assays for the captured T. glis shrew (1), M. berdmorei ground squirrels (2), and H. javanicus mongoose (1). Two O. tsutsugamushi isolates (PYA5 and PYA6) were established from livers and spleens of 2 B. indica rats (Table 1). Together, the high prevalence of O. tsutsugamushi–seroreactive small mammals and the presence of infested scrub typhus–specific arthropod vectors indicate that scrub typhus is endemic to the Ban Pongyeang area.

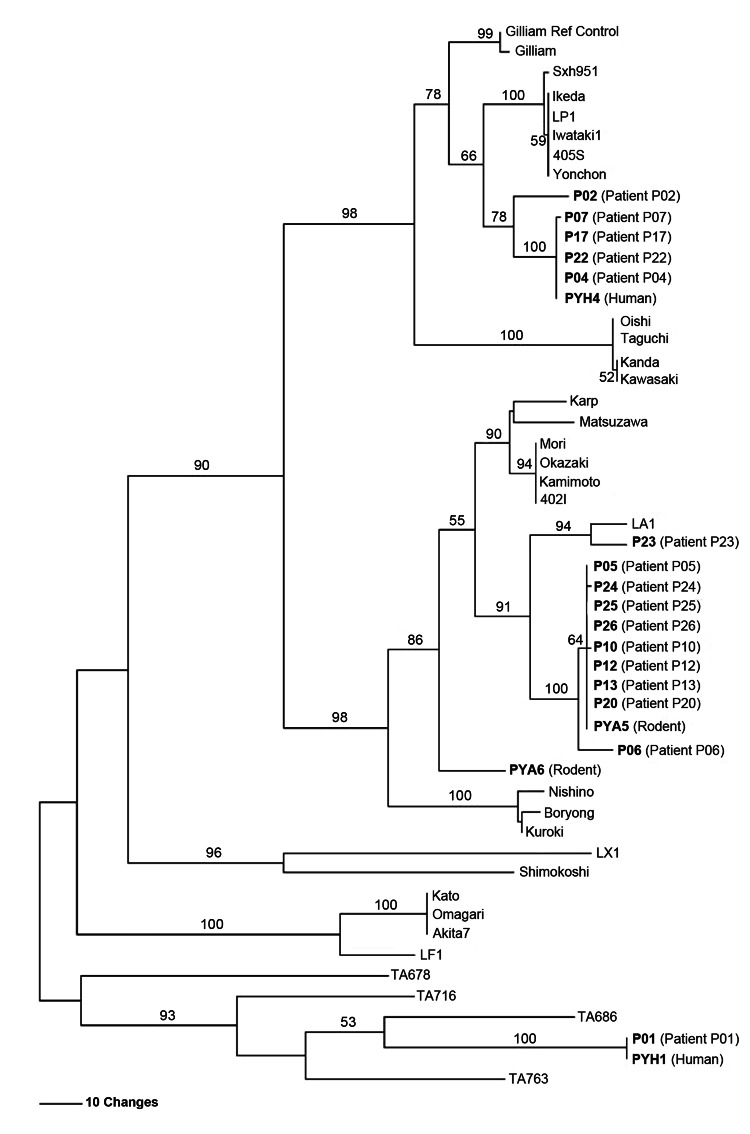

O. tsutsugamushi obtained from the infected children and small mammals was characterized on the basis of Orientia spp.–specific 56-kDa gene fragments. Multiple alignment and phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that the 4 O. tsutsugamushi isolates from Ban Pongyeang fell into 4 clusters. Sequences for 3 of the isolates clustered with Gilliam, LA, and TA, 3 genotypes that are commonly found in Southeast Asia (10,11); the sequence of the fourth isolate presented as a divergent distinct genotype (Figure 2). Most of the children were infected with a strain genetically similar to the LA cluster (Figure 2). Moreover, this major pathogenic strain was recovered from B. indica bandicoot rats (isolate PYA5), the most commonly found rats in the village and the small mammals with the highest densities of L. deliense chiggers. These findings indicate possible transmission between animals and humans. Many studies have demonstrated that chiggers can acquire O. tsutsugamushi during the feeding process (12–15). Therefore, rodents could play a critical role as reservoir hosts for O. tsutsugamushi and for feeding vector mites, causing widespread distribution of O. tsutsugamushi in Ban Pongyeang.

Figure 2.

Maximum parsimony phylogenetic tree of Orientia tsutsugamushi based on partial 56-kDa type-specific antigen gene sequences, demonstrating the relationships among O. tsutsugamushi isolates from Thailand and strains causing scrub typhus in humans in Ban Pongyeang, Thailand, and reference (ref) strains. The tree was midpoint rooted. Bootstrap values >50% are labeled over branches (1,000 replicates). Isolates from Thailand are in boldface. The tree was generated by using heuristic search with random stepwise addition (10 replicates). Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site.

Conclusions

Investigation of scrub typhus in Ban Pongyeang, northern Thailand, demonstrated O. tsutsugamushi infection in children and rodent hosts, and it demonstrated the potential for transmission between small mammal reservoirs and humans. Campaigns concerning protection from scrub typhus should be established in areas where O. tsutsugamushi is endemic, and local medical clinics should be made aware of the campaigns. Specific plans for protecting against/preventing O. tsutsugamushi transmission are crucially needed to prevent scrub typhus infection in humans.

Clinical manifestations and laboratory test results for 26 scrub typhus–infected children from Ban Pongyeang, Thailand, who were hospitalized during June 2006–May 2007.

Acknowledgments

We thank the pediatric ward nurses and central laboratory staff at Nakhornping Hospital for their assistance.

Support for this study was provided by the Royal Thai Army (to W.R.); the Thailand Tropical Diseases Research Funding Program (T-2; to J.G.); the Thanphuying Viraya Chavakul Foundation for Medical Armed Forces Research Grant (to T.R.); and the Global Emerging Infections Surveillance and Response System, a Division of the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center (work unit no. 0000188M.0931.001.A0074) (to A.L.R.).

Biography

Dr Rodkvamtook, a Lieutenant Colonel in the Royal Thai Army, is chief of the Pathology Section, Research Division, Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences, Royal Thai Army Component in Bangkok. His interests are in the study of arthropod borne diseases, particularly rickettsial diseases.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Rodkvamtook W, Gaywee J, Kanjanavanit S, Ruangareerate T, Richards AL, Sangjun N, et al. Scrub typhus outbreak, northern Thailand, 2006–2007. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013 May [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1905.121445

References

- 1.Rosenberg R. Drug-resistant scrub typhus: paradigm and paradox. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:131–2. 10.1016/S0169-4758(97)01020-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamura A, Ohashi N, Urakami H, Miyamura S. Classification of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi in a new genus, Orientia gen. nov., as Orientia tsutsugamushi comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:589–91. 10.1099/00207713-45-3-589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watt G, Chouriyagune C, Ruangweerayud R, Watcharapichat P, Phulsuksombati D, Jongsakul K, et al. Scrub typhus infections poorly responsive to antibiotics in northern Thailand. Lancet. 1996;348:86–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)02501-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bureau of Epidemiology, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand. Annual epidemiologic surveillance report 2007. Scrub typhus [cited 2013 Mar 6]. http://www.boe.moph.go.th/Annual/ANNUAL2550/Part1/Annual_MenuPart1.html

- 5.Bozeman FM, Elisberg BL. Serological diagnosis of scrub typhus by indirect immunofluorescence. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1963;112:568–73 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown GW, Shirai A, Rogers C, Groves M. Diagnostic criteria for scrub typhus: probability values for immunofluorescent antibody and Proteus OXK agglutination titers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:1101–7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enatsu T, Urakami H, Tamura A. Phylogenetic analysis of Orientia tsutsugamushi strains based on the sequence homologies of 56-kDa type-specific antigen genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;180:163–9. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08791.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swofford DL. PAUP*: Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (and other methods) 4.0 beta 10. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamura A, Takahashi K, Tsuruhara T, Urakami H, Miyamura S, Sekikawa H, et al. Isolation of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi antigenically different from Kato, Karp, and Gilliam strains from patients. Microbiol Immunol. 1984;28:873–82 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tay ST, Rohani YM, Ho TM, Shamala D. Sequence analysis of the hypervariable regions of the 56 kDa immunodominant protein genes of Orientia tsutsugamushi strains in Malaysia. Microbiol Immunol. 2005;49:67–71 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruang-Areerate T, Jeamwattanalert P, Rodkvamtook W, Richards AL, Sunyakumthorn P, Gaywee J. Genotype diversity and distribution of Orientia tsutsugamushi causing scrub typhus in Thailand. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2584–9. 10.1128/JCM.00355-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traub R, Wisseman CL Jr, Jones MR, O’Keefe JJ. The acquisition of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi by chiggers (trombiculid mites) during the feeding process. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1975;266:91–114. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb35091.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker JS, Gan E, Chye CT, Muul I. Involvement of small mammals in the transmission of scrub typhus in Malaysia: isolation and serological evidence. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1973;67:838–45 . 10.1016/0035-9203(73)90012-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi M, Murata M, Hori E, Tanaka H, Kawamura A Jr. Transmission of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi from Apodemus speciosus, a wild rodent, to larval trombiculid mites during the feeding process. Jpn J Exp Med. 1990;60:203–8 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frances SP, Watcharapichat P, Phulsuksombati D, Tanskul P, Linthicum KJ. Seasonal occurrence of Leptotrombidium deliense (Acari: Trombiculidae) attached to sentinel rodents in an orchard near Bangkok, Thailand. J Med Entomol. 1999;36:869–74 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Clinical manifestations and laboratory test results for 26 scrub typhus–infected children from Ban Pongyeang, Thailand, who were hospitalized during June 2006–May 2007.