Abstract

Objective:

Describe the rates of suicidal ideation, self-injury, and suicide among detained youth as well as risk factors and preventive measures that have been attempted.

Method:

Literature searches in PubMed, PsycINFO, and the Social Science Citation Index were undertaken to identify published studies written in English. Governmental data was also included from English-speaking nations.

Results:

The adjusted risk of suicide was 3 to 18 times higher than age-matched controls. The prevalence of lifetime suicidal ideation ranged from 16.9% to 59% while lifetime self-injury ranged from 6.2% to 44%. Affective disorders, borderline personality traits, substance use disorders, impulse control disorders, and anxiety disorders were associated with suicidal thoughts and self-injury. Screening for suicidal ideation upon entry was associated with a decreased rate of suicide.

Conclusions:

All youth should be screened upon admission. Identified co-morbid disorders should also be treated.

Keywords: youth, suicide, self-harm, delinquent

Résumé

Objectif:

Décrire les taux d’idéation suicidaire, d’automutilation et de suicide chez les jeunes détenus ainsi que les facteurs de risque et les mesures préventives adoptées à l’essai.

Méthode:

Des recherches de la littérature ont été entreprises dans PubMed, PsycINFO, et le Social Science Citation Index afin d’identifier les études publiées en anglais. Des données du gouvernement de nations anglophones ont également été incluses.

Résultats:

Le risque corrigé de suicide était de 3 à 18 fois plus élevé que chez les témoins du même âge. La prévalence de durée de vie de l’idéation suicidaire allait de 16,9% à 59% tandis que l’automutilation de durée de vie se situait entre 6,2% et 44%. Les troubles affectifs, les traits de la personnalité limite, les troubles liés à l’utilisation d’une substance, les troubles de contrôle des impulsions, et les troubles anxieux étaient associés aux pensées suicidaires et à l’automutilation. Le dépistage de l’idéation suicidaire à l’admission était associé à un risque moindre de suicide.

Conclusions:

Tous les jeunes devraient subir un dépistage à l’admission. Les troubles comorbides identifiés devraient aussi être traités.

Keywords: jeunes, suicide, automutilation, délinquant

Introduction

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among Canadian youth (Kutcher & Szumilas, 2008). Admission into a correctional facility is a highly stressful event, which can precipitate suicidal ideation and self-injury in youth. While reviews about suicide in adult correctional facilities exist (Matschnig, Frühwald, & Frottier, 2006; Mann et al., 2005) there is little known about youth suicide. Liebling’s (1993) review only included one youth study. We systematically examined published studies to describe the rate and risk factors for suicidal ideation, self-injury, and suicide among youth in correctional facilities. This review is guided by the PRISMA statement, which consists of evidence-based minimum criteria for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA, 2012).

Method

Information Sources and Search Strategy

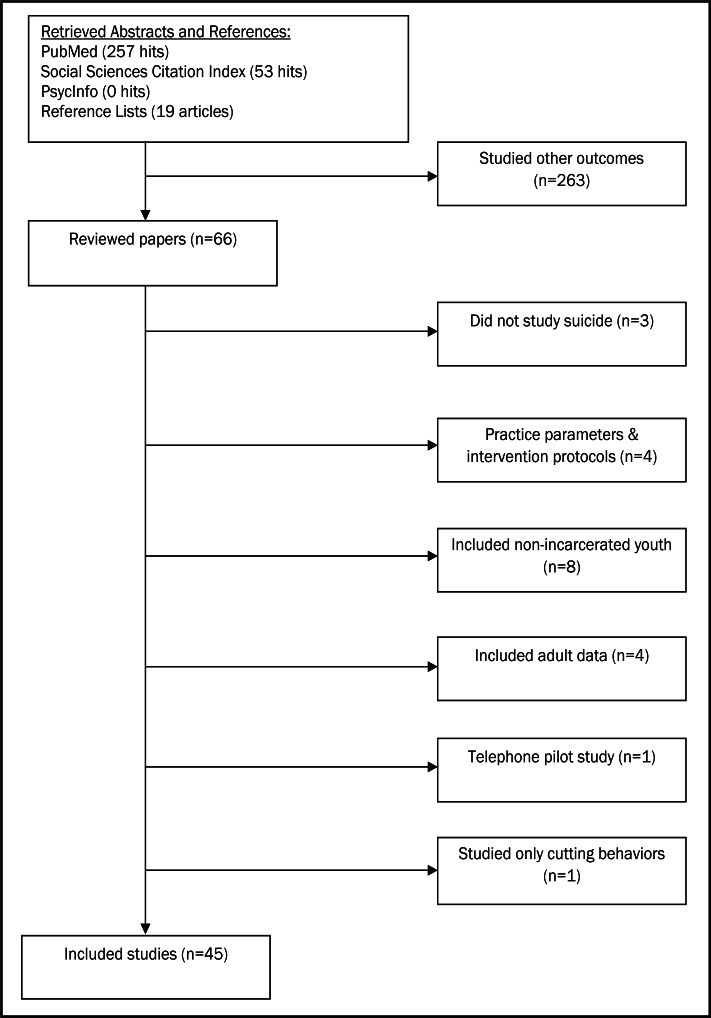

Studies were retrieved through literature searches in the databases of PubMed, PsycINFO, and the Social Science Citation Index (January 1955 to November 2011). Searches combined the key words “youth,” “suicide,” “juvenile,” “jails,” “self harm,” and “correctional facility”. Articles were hand-searched and references were reviewed. A separate search was conducted in Google for grey literature from English-speaking nations. In total, 45 articles were identified, as shown in Figure 1. Two governmental articles were retrieved, including one each from the US and the UK. Practice parameters and intervention protocols were not included. Due to the heterogeneity of the population, we did not conduct a meta-analysis of the data.

Figure 1.

Overview of study selection

Eligibility Criteria

Due to the paucity of articles retrieved, broad inclusion criteria were utilized to inform the review. The principal inclusion criteria were: 1) inclusion of information about suicidal ideation or self-injury which occurred in a correctional facility; and, 2) inclusion of youth only, as defined by an age between 11 and 22. Studies that met these criteria were included, regardless of primary objectives, design, or quality.

Study Selection

Abstracts were reviewed by the lead author and articles were searched for the eligibility criteria. Articles with clear relevance were included, while those with questionable reference were reviewed by the team and included based on consensus.

Types of Outcome Measures

This review intended to obtain information on suicidal ideation, self-injury, and suicide. The distinction was not made between non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicidal behavior though the function differs between them. Jacobson & Gould (2007) reported rates of NSSI in non-incarcerated youth between 13.0% to 23.2%. We were unable to distinguish between suicidal behavior and NSSI due to articles using the term “suicide” instead of “self-harm.” We therefore will use the term “self-injury” to capture both suicidal behavior and NSSI.

Consideration of Bias

As per PRISMA guidelines, assessment of the risk of bias at the study level and outcome level was undertaken (PRISMA, 2012). Reporting bias was a concern; although Mace et al. (Mace, Rohde, & Gnau, 1997) found good concordance on retesting, Putnins (2005) disclosed concerns about inconsistent reporting. Although attempts were made for complete inclusion, publication bias may have limited the inclusion of all relevant articles. The use of Google helped to reduce this bias and allowed the retrieval of relevant grey literature. Cultural bias may have also occurred; as noted by Hawton et al. (Hawton, Saunders, & O’Connor, 2012), youth suicide may be under-recorded by different countries and national rates should be interpreted with caution.

Results

Death by Suicide

Suicide in correctional facilities is the leading cause of death (Gallagher & Dobrin, 2006a). The suicide rate for incarcerated youth was 3 to 18 times higher than the age-matched general population (Gallagher & Dobrin, 2006b; Fazel, Benning, & Danesh, 2005). Most suicides occurred by hanging during regular waking hours by those who engaged in previous self-injury and had psychiatric illness; most were confined on nonviolent offenses (Hayes, 2009). Deaths were distributed fairly evenly over the confinement period with no seasonal differences (Hayes, 2009; Hockenberry, Sickmund, & Sladky, 2009). Increased rates occurred in facilities that did not screen all individuals within 24 hours of arrival, locked sleeping room doors, and were designed to screen for future placements (Gallagher & Dobrin, 2006b). Overcrowding was not a contributing factor (Hayes, 2009). Seventeen percent of youth were on suicide precaution status at the time of their death (Hayes, 2009).

Suicidal Ideation and Self-injury

Eighteen articles reported rates of suicidal ideation and 23 reported on self-injury. Studies examined current rates, lifetime rates, or a discrete time period (Table 1). Current suicidal ideation ranged from 9.6% to 52% (Wasserman, McReynolds, Lucas, Fisher, & Santos, 2002; Esposito & Clum, 2002). Suicidal ideation in the previous year ranged from 20% to 68% (Lader, Singleton, & Meltzer, 2000; Alessi, McManus, Brickman, & Grapentine, 1984). Lifetime suicidal ideation varied from 16.9% to 58.3% (Ruchkin, Schwab-Stone, Koposov, Vermeiren, & King, 2003; Freedenthal, Vaughn, Jenson, & Howard, 2007). Table 2 summarizes self-injury in incarcerated youth. Lawlor and Kosky (1992) found that 1% of residents incarcerated longer than seven days attempted suicide. The facility rate of report of a suicide attempt was just over 4% (Gallagher & Dobrin, 2006b). The report of self-harm by youth was higher, with 14.5% reporting engaging in self-injury (Kirikadis, 2008). Self-injury in the previous year ranged between 15% to 61% (Lader et al., 2000; Alessi et al., 1984) while lifetime self-injury ranged from 6.2% to 44% (Matsumoto et al., 2009; Lader et al., 2000). No studies confirmed self-harm acts by staff.

Table 1.

Reported prevalence of suicidal ideation

| Timeframe | Author(s) and country | Sample size and gender | Age | Reported prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | Esposito & Clum, 2002 – US | 200; 141 males, 59 females | 12–17 years | 52% |

| Plattner et al., 2007 – Austria | 319; 266 males, 53 females | 14–21 years | 21.6% | |

| Mace et al., 1997 - US | 555; 458 males, 97 females | Mean age 15.3 years | 14.2% | |

| Wasserman et al., 2002 – US | 292 males | Mean age 17.04 years | 9.6% | |

| Previous month | Evans et al., 1996 – US | 394; 334 males, 60 females | 12–18 years | 29.5% |

| Previous six months | Abram et al., 2008 – US | 1829; 1170 males, 656 females | 10–18 years | 10.3% |

| Previous year | Alessi et al., 1984 – US | 71; 40 males, 31 females | 14–18 years | 68% |

| Lader et al., 2000 – UK | 330; 314 males, 26 females | 16–20 years | 35% remand males, 20% sentenced males; 50% remand females, 34% sentenced females | |

| Suk et al., 2009 – Belgium | 290; 228 males, 62 females | Males 16.3 years (mean) females 15.7 years (mean) | 21.5% males, 58.1% females | |

| Lifetime | Freedenthal et al., 2007 – US | 723; 629 males, 94 females | Mean age 15.5 years | 58.3% |

| Morgan & Hawton, 2004 – UK | 45; no information on gender | 16–18 years | 26.6% | |

| Morris et al., 1995 – US | 1801; 1574 males, 219 females | 21 and under | 22% | |

| Plattner et al., 2007 – Austria | 319; 266 males, 53 females | 14–21 years | 39.8% | |

| Rohde et al., 1997a – US | 555; 458 males, 97 females | Mean age 15.3 years | 33.7% | |

| Ruchkin et al., 2003 – Russia | 271 males | 14–19 years | 16.9% | |

| Matsumoto et al., 2009 – Japan | 301; 113 male, 22 female | 15–17 years | 21.2% males, 54.5% females | |

| Lader et al., 2000 – UK | 330; 314 males, 26 females | 16–20 years | 46% remand males, 37% sentenced males, 59% remand females, 52% sentenced females | |

| Kenny et al., 2008 – Australia | 242; 223 males, 19 females | Males 17.2 years (mean), females 16.9 years (mean) | 19.2% |

Table 2.

Reported prevalence of self-injury

| Timeframe | Author(s) and country | Sample size and gender distribution | Age | Reported prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| While in custody | Kiriakidis, 2008 – UK | 152 males | 16–21 years, mean age 18.9 years | 14.5% |

| Previous month | Wasserman et al., 2002 – US | 292 males | Mean age 17.04 | 3.1% |

| Previous year | Alessi et al., 1984 – US | 71; 40 males, 31 females | 14–18 years | 61% |

| Evans et al., 1996 – US | 394; 334 males, 60 females | 12–18 years | 24.4% | |

| Lader et al., 2000 – UK | 330; 314 males, 26 females | 16–20 years | 15%/7% remand/sentenced males, 27%/16% remand/sentenced females | |

| Kenny et al., 2008 – Australia | 242; 223 males, 19 females | Males 17.2 years (mean), females 16.9 years (mean) | 21.9% | |

| Lifetime | Abram et al., 2008 – US | 1829; 1170 males, 656 females | 10–18 years | 11.0% |

| Esposito & Clum, 2002– US | 200; 141 males, 59 females | 12–17 years | 33% | |

| Freedenthal et al., 2007– US | 723; 629 males, 94 females | Mean age 15.5 | 25.5% | |

| Hales et al., 2003 – UK | 355 males | 15–21 years | 20% | |

| Harris et al., 1993 – Australia | 47 males | 15–19 years | 40% | |

| Howard et al., 2003 – Australia | 300; 270 males, 30 females | 12–22 years | 23.7% | |

| Kempton & Forehand, 1992 – US | 51 males | 11–19 years | 30% | |

| Lader et al., 2000 – UK | 330; 314 males, 26 females | 16–20 years | 27%/20% remand/sentenced males, 44%/37% remand/sentenced females | |

| Mace et al., 1997 – US | 555; 458 males, 97 females | Mean age 15.3 years | 19.4% | |

| Matsumoto et al., 2009– Japan | 301; 113 male, 22 female | 15–17 years | 6.2% male, 27.3% female | |

| Morgan & Hawton, 2004– UK | 45; no information on gender | 16–18 years | 15.6% | |

| Morris et al., 1995 – US | 1801; 1574 males,219 females | 21 and under | 16% | |

| Penn et al., 2003 – US | 289; 234 males, 55 females | 12–18 years | 12.4% | |

| Putnins, 2005 – Australia | 900; 810 males, 90 females | 11–20 years | 27.1% | |

| Rohde et al., 1997b – US | 60; 44 males, 16 females | Mean age 14.9 | 36.7% | |

| Rohde et al., 1997a – US | 555; 458 males, 97 females | Mean age 15.3 years | 19.4% | |

| Ruchkin et al., 2003 – Russia | 271 males | 14–19 years | 17.6% |

Risk Factors for Suicidal Ideation and Intentional Self-injury

Several mental disorders were associated with suicidal ideation and self-injury. Borderline personality disorder traits (Alessi et al., 1984), affective disorders (Plattner et al., 2007; Harris & Lennings, 1993; Abram et al., 2008; Miller, Chiles, & Barnes, 1982; Alessi et al., 1984; Rohde, Seeley, & Mace, 1997a; Gallagher & Dobrin, 2005; Penn, Esposito, Schaeffer, Fritz, & Spirito, 2003), substance use disorders (Morris et al., 1995; Freedenthal et al., 2007; Sanislow, Grilo, Fehon, Axelrod, & McGlashan, 2003; Chapman & Ford, 2008), post traumatic stress disorder (Plattner et al., 2007; Ruchkin et al., 2003; Suk et al., 2009; Chapman & Ford, 2008), social phobia (Plattner et al., 2007), anxiety (Abram et al., 2008; Penn et al., 2003), and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (Plattner et al., 2007; Miller et al., 1982; Putnins, 2005) increased the risk of suicidal ideation and self-injury.

Other risk factors for suicidal ideation and self-injury included sexual abuse (Morgan & Hawton, 2004; Esposito & Clum, 2002; Evans, Albers, Macari, & Mason, 1996; Matsumoto et al., 2009), female gender (Abram et al., 2008; Miller et al., 1982; Matsumoto et al., 2009), exposure to violence (Howard, Lennings, & Copeland, 2003), housing stress (Howard et al., 2003), white race (Kempton & Forehand, 1992; Alessi et al., 1984), impulsivity (Mace et al., 1997; Rohde et al., 1997a; Sanislow et al., 2003), anger (Putnins, 2005; Penn et al., 2003), a tendency to act out (Miller et al., 1982; Suk et al., 2009), younger age (Morris et al., 1995), and perceived negative parenting (Ruchkin et al., 2003).

When compared with incarcerated teens who did not engage in such behavior, self-harming youth had a greater number of offenses, were more disruptive in school, performed worse on a problem-solving task, and committed more rule violations (Suk et al., 2009; Chowanec, Josephson, Coleman, & David, 1991). Sanislow et al. (2003) compared self-injury in juvenile detainees to psychiatric inpatients and found that while both groups reported similar elevated levels of distress, after controlling for depression and impulsivity, drug abuse remained associated only with self-harm among detainees.

Prevention of Suicide

Screening of youth upon entry varied. In a US governmental report, 84% of the 80% of facilities that reported suicide screening said that they evaluated all youth for risk (Hockenberry et al., 2009). Gallagher and Dobrin (2005 Gallagher and Dobrin (2006b) found that only 60% of facilities screened all youth upon entry but those that did were less likely to report a suicide. Facilities differed in the level of suicide training; less than 38% of facilities that experienced a suicide provided annual suicide prevention training to its direct care staff (Hayes, 2005). Approximately 40% used neither mental health professionals nor counselors trained by mental health professionals to conduct suicide screening (Hockenberry et al., 2009). Levels of agreement about suicide risk by detention centre staff and mental health clinicians were weak (Stathis, Litchfield, Letters, Doolan, & Martin, 2008).

With regard to prevention, US governmental data indicated that between 21% and 85% of facilities placed high risk youth in locked observation rooms, removed risky items, used restraints, or used special clothing to prevent harm or identify youth at risk for suicide (Hockenberry et al., 2009). No article followed incarcerated youth prospectively to determine the impact of prevention measures.

Discussion

Several important findings are demonstrated in this study. Detained youth are at increased risk of suicide and suicidal ideation. There is significant morbidity and mortality in incarcerated youth and the rates of psychiatric disorder are elevated (Teplin, Abram, McClelland, Dulcan, & Mericle, 2002; Wasserman et al., 2003). Universal screening upon entry has been advocated (Penn & Thomas, 2005). Screening should be brief, easily administered, and used to identify those youth who require a comprehensive assessment (Cocozza & Skowyra, 2000). Work is underway to identify screening instruments (Galloucis & Francek, 2002; Grisso & Underwood, 2004), crisis assessment tools, and intervention models (Roberts & Bender, 2006) that can be used in youth correctional facilities.

Several limitations exist. One problem is the heterogeneity of the population. Rates of self-harm for males and females were often reported together in studies and the psychopathology and function of self-harm may have differed. A previous survey showed that the onset of puberty was related to self-harm, especially in girls and for self-cutting (Patton et al., 2007). Also, studies included individuals at different stages of the judicial process with a wide variety of charges. Another limitation was that of only studying youth residing in a youth correctional facility. Depending on the jurisdiction and nature of the crime, adolescents may have been placed in adult detention centers, which would limit their representation in our study. Another problem was that it was not possible to ascertain when in the incarceration process a youth developed maladaptive coping strategies to deal with stress, and whether suicidal ideation or self-injury occurred as a result of incarceration or preceded it.

There is much information that still needs to be discovered. One such area is distinguishing self-harm in older and younger juvenile adolescents. Dervic et al. (Dervic, Breut, & Oquendo, 2008) reported that youth suicides in those younger than age 14 was associated with cognitive immaturity/misjudgment, impulsivity, and availability of suicide methods, whereas older adolescents showed greater influence from depression and substance abuse. In adults, family history has been studied and suicidal behavior for manipulation versus ending life has been distinguished (Lohner & Konrad, 2006). By studying these areas in youth, prevention strategies can be implemented which may decrease the rates of self-injury and suicide.

Conclusion

Detained youth are at higher risk than the general population for suicidal ideation and self-injury. Psychiatric illness is common and more help is needed to identify and treat those at risk. It is recommended that all youth admitted to a correctional facility be screened on arrival. Those at risk should be closely monitored. Adequate training for staff is imperative. Further study is required to determine the impact of prevention strategies on suicide and self-injury rates.

Acknowledgements / Conflicts of Interest

Preparation of this article was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) New Investigator Award (#152348) to Dr. Sareen and a CIHR operating grant (#166720) to the Swampy Cree Suicide Prevention Team. The authors have no financial conflicts to disclose.

References

- Abram KM, Choe JY, Washburn JJ, Teplin LA, King DC, Dulcan MK. Suicidal ideation and behaviors among youths in juvenile detention. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(3):291–300. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318160b3ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi NE, McManus M, Brickman A, Grapentine L. Suicidal behavior among serious juvenile offenders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1984;141(2):286–287. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JF, Ford JD. Relationships between suicide risk, traumatic experiences, and substance use among juvenile detainees. Archives of Suicide Research. 2008;12:50–61. doi: 10.1080/13811110701800830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowanec GD, Josephson AM, Coleman C, Davis HJ. Self-harming behavior in incarcerated male delinquent adolescents. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30(2):202–207. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199103000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocozza J, Skowyra K. Youth with mental health disorders: Issues and emerging responses. Juvenile Justice. 2000;7:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dervic K, Brent DA, Oquendo MA. Completed suicide in childhood. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2008;31(2):271–291. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito CL, Clum GA. Social support and problem-solving as moderators of the relationship between childhood abuse and suicidality: Applications to a delinquent population. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2002;15(2):137–146. doi: 10.1023/A:1014860024980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans W, Albers E, Macari D, Mason A. Suicide ideation, attempts and abuse among incarcerated gang and nongang delinquents. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 1996;13:115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Benning R, Danesh J. Suicide in male prisoners in England and Wales, 1978–2003. Lancet. 2005;366:1301–1302. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedenthal S, Vaughn MG, Jenson JM, Howard MO. Inhalant use among incarcerated youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90(1):81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher CA, Dobrin A. The association between suicide screening practices and attempts requiring emergency care in juvenile justice facilities. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(5):485–493. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000156281.07858.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher CA, Dobrin A. Deaths in juvenile justice residential facilities. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006a;38(6):662–668. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher CA, Dobrin A. Facility-level characteristics associated with serious suicide attempts and deaths from suicide in juvenile justice residential facilities. Suicide & Life Threatening Behavior. 2006b;36(3):363–375. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloucis M, Francek H. The Juvenile Suicide Assessment: An instrument for the assessment and management of suicide risk with incarcerated juveniles. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health. 2002;4(3):181–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisso T, Underwood LA. Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders Among Youth in the Juvenile Justice System. 2004. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/1b/a4/4b.pdf.

- Hales H, Davison S, Misch P, Taylor PJ. Young male prisoners in a Young Offenders’ Institution: Their contact with suicidal behaviour by others. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26(6):667–685. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(03)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TE, Lennings CJ. Suicide and adolescence. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 1993;37(3):263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Saunders KEA, O’Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012;379:2373–2382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes LM. Juvenile suicide in confinement in the United States results from a national survey. Crisis. 2005;26(3):146–148. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.26.3.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes LM. Juvenile suicide in confinement – Findings from the First National Survey. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2009;34:353–363. doi: 10.1521/suli.2009.39.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockenberry S, Sickmund M, Sladky A. Juvenile residential facility census, 2006: Selected Findings. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/228128.pdf Accessed June 30, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Howard J, Lennings CJ, Copeland J. Suicidal behavior in a young offender population. Crisis. 2003;24(3):98–104. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.24.3.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson CM, Gould M. The epidemiology and phenomenology of non-suicidal self-injurious behavior among adolescents: A critical review of the literature. Archives of Suicide Research. 2007;11:129–147. doi: 10.1080/13811110701247602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempton T, Forehand R. Suicide attempts among juvenile delinquents: The contribution of mental health factors. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1992;30(5):537–541. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(92)90038-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DT, Lennings CJ, Munn OA. Risk factors for self-harm and suicide in incarcerated young offenders: Implications for policy and practice. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice. 2008;8:358–382. [Google Scholar]

- Kiriakidis SP. Bullying and suicide attempts among adolescents kept in custody. Crisis. 2008;29:216–218. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.29.4.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutcher SP, Szumilas M. Youth suicide prevention. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2008;178(3):283–285. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lader D, Singleton N, Meltzer H. Psychiatric morbidity among young offenders in England and Wales. 2000. Retrieved from http://www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_health/PyscMorbYoungOffenders97.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lawlor D, Kosky R. Serious suicide attempts among adolescents in custody. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;26:474–478. doi: 10.3109/00048679209072073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebling A. Suicide in young prisoners: A summary. Death Studies. 1993;17:381–409. [Google Scholar]

- Lohner J, Konrad N. Deliberate self-harm and suicide attempt in custody: Distinguishing features in male inmates’ self-injurious behavior. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2006;29(5):370–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace D, Rohde P, Gnau V. Psychological patterns of depression and suicidal behavior of adolescents in a juvenile detention facility. Journal for Juvenile Justice and Detention Services. 1997;12:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, Hendin H. Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294(16):2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matschnig T, Frühwald S, Frottier P. Suicide behind bars -- an international review. Psychiatr Prax. 2006;33(1):6–13. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-834784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T, Tsutsumi A, Izutsu T, Imamura F, Chiba Y, Takeshima T. Comparative study of the prevalence of suicidal behavior and sexual abuse history in delinquent and non-delinquent adolescents. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2009;63(2):238–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ML, Chiles JA, Barnes VE. Suicide attempters within a delinquent population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50(4):491–498. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J, Hawton K. Self-reported suicidal behavior in juvenile offenders in custody: Prevalence and associated factors. Crisis. 2004;25(1):8–11. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.25.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RE, Harrison EA, Knox GW, Tromanhauser E, Marquis DK, Watts LL. Health risk behavioral survey from 39 juvenile correctional facilities in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1995;17(6):334–344. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00098-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Hemphill SA, Beyers JM, Bond L, Toumbourou JW, McMorris BJ, Catalano RF. Pubertal stage and deliberate self-harm in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(4):508–514. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31803065c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn JV, Esposito CL, Schaeffer LE, Fritz GK, Spirito A. Suicide attempts and self-mutilative behavior in a juvenile correctional facility. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(7):762–769. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046869.56865.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn JV, Thomas C. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of youth in juvenile detention and correctional facilities. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(10):1085–1098. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000175325.14481.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plattner B, The SS, Kraemer HC, Williams RP, Bauer SM, Kindler J, Steiner H. Suicidality, psychopathology, and gender in incarcerated adolescents in Austria. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;68(10):1593–1600. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRISMA PRISMA Transparent Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012 from http://www.prisma-statement.org.

- Putnins AL. Correlates and predictors of self-reported suicide attempts among incarcerated youths. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2005;49(2):143–157. doi: 10.1177/0306624X04269412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AR, Bender K. Juvenile offender suicide: Prevalence, risk factors, assessment, and crisis intervention protocols. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health. 2006;8(4):255–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Seeley JR, Mace DE. Correlates of suicidal behavior in a juvenile detention population. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 1997a;27(2):164–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Seeley JR, Mace DE. The association of psychiatric disorders with suicide attempts in a juvenile delinquent sample. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health. 1997b;7:187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ruchkin VV, Schwab-Stone M, Koposov RA, Vermeiren R, King RA. Suicidal ideations and attempts in juvenile delinquents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:1058–1066. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Fehon DC, Axelrod Sr, McGlashan TH. Correlates of suicide risk in juvenile detainees and adolescent inpatients. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(2):234–240. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200302000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathis S, Litchfield B, Letters P, Doolan I, Martin G. A comparative assessment of suicide risk for young people in youth detention. Archives of Suicide Research. 2008;12(1):62–66. doi: 10.1080/13811110701800939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suk E, Mill JV, Vermeiren R, Ruchkin V, Schwab-Stone M, Doreleijers T, Deboutte D. Adolescent suicidal ideation: A comparison of incarcerated and school-based samples. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;18:377–383. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0740-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK, Mericle AA. Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(12):1133–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman GA, Jensen PS, Ko SJ, Cocozza J, Trupin E, Angold A, Grisso T. Mental health assessments in juvenile justice: Report on the consensus conference. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(7):752–761. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046873.56865.4B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman GA, McReynolds LS, Lucas CP, Fisher P, Santos L. The voice DISC-IV with incarcerated male youths: Prevalence of disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(3):314–321. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200203000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]