Abstract

Mutations in the inverted formin 2 gene (INF2) have recently been identified as the most common cause of autosomal dominant focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). In order to quantify the contribution of various genes contributing to FSGS, we sequenced INF2 where all mutations have previously been described (exons 2 to 5) in a total of 215 probands and 281 sporadic individuals with FSGS, along with other known genes accounting for autosomal dominant FSGS (ACTN4, TRPC6 and CD2AP) in 213 probands. Variants were classified as disease-causing if they altered the amino acid sequence, were not found in control samples, and in families segregated with disease. Mutations in INF2 were found in a total of 20 of the 215 families (including those previously reported) in our cohort of autosomal dominant familial nephrotic syndrome or FSGS, thereby explaining disease in 9 percent. INF2 mutations were found in 2 of 281 individuals with sporadic FSGS. In contrast, ACTN4 and TRPC6-related disease accounted for 3 and 2 percent of our familial cohort, respectively. INF2-related disease showed variable penetrance, with onset of disease ranging widely from childhood to adulthood and commonly leading to ESRD in the third and fourth decade of life. Thus, mutations in INF2 are more common, although still minor, monogenic cause of familial FSGS when compared to other known autosomal dominant genes associated with FSGS.

Keywords: INF2, FSGS, nephrotic syndrome, mutations, familial FSGS, sporadic cases

INTRODUCTION

Glomerular disease, characterized by focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis histology (FSGS), is a challenging disease to treat due to its frequent relapsing unremitting course and high rate of progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD). For unclear reasons, FSGS has a rising incidence, now becoming a common cause of glomerular disease in both children and adults worldwide.1–4 Although only a minority of those affected by FSGS have a family history of this lesion, the study of hereditary forms has helped inform our understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of FSGS. Mutations in ACTN4, TRPC6 and CD2AP are all rare causes of FSGS, although never quantified in the literature.5–8 In contrast, several recent studies suggest that mutations in the INF2 gene account for a significant proportion of hereditary cases.9–11 INF2 belongs to the formin family, a group of heterogeneous actin binding proteins that regulate a variety of cytoskeleton-dependent cellular processes.12–16 Moreover, INF2 has been implicated in individuals with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease who manifest FSGS as part of this syndrome.17

We previously reported INF2 as a cause of autosomal dominant FSGS in 11 of 93 families screened. Initial screening of the entire gene revealed disease-causing mutations only in exons 2 to 4. In this study, we expand on our initial report by mutational analysis of the DNA sequence encoding the diaphanous inhibitory domain (DID) of INF2 in a total of 215 probands from autosomal dominant FSGS families and also in 281 individuals with apparent sporadic disease. Known autosomal dominant FSGS genes including ACTN4, TRPC6 and CD2AP were also screened in 213 probands for comparison.

RESULTS

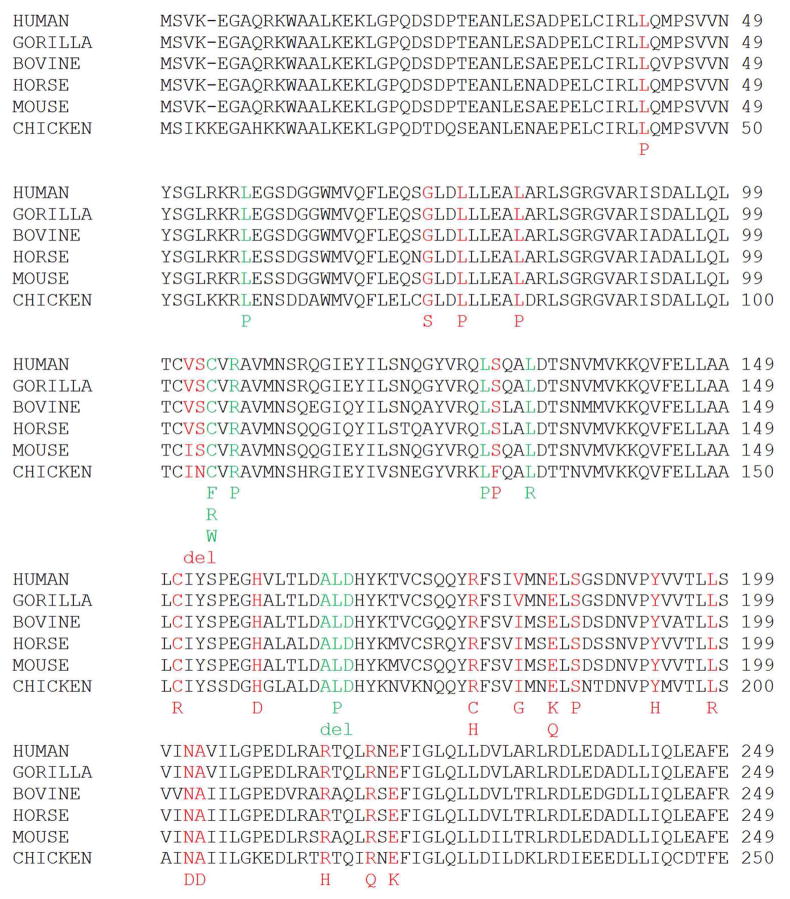

INF2 exons 2, 3, 4 and 5 were sequenced by Sanger method in the DNA belonging to 215 probands from autosomal dominant FSGS families and 281 sporadic cases in order to evaluate variation in the DID domain of the gene. Given the absence of mutations detected outside of this domain based on our own experience and other published reports, we restricted mutational screening to these exons.9–11, 17 Thirteen missense variants in 20 families that segregated with disease were identified, thereby explaining disease in 9% of our cohort with hereditary proteinuric renal disease (Tables 1 and 2). Individuals whose clinical status was defined as indeterminate given their young age were also found to have the mutations in some instances. Eleven of these families were reported previously. These tables summarize results from our entire cohort with INF2-related disease.11 We also now include sporadic cases of FSGS and identify mutations in 2 individuals (Tables 1 and 3). Scores from PolyPhen-2 software analysis (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2) to predict the functional effects of missense INF2 variants ranged from 0.789 to 1.000, predicting that INF2 variants were possibly or probably damaging. No INF2 variants were present in any of the 10800 control chromosomes assayed or referenced in dbSNP, 1000 Genomes Project or in the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s Exome Sequencing Project. All mutations affected highly conserved residues (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Percentage of families and sporadics affected by INF2-related kidney disease in the current cohort compared to other groups reported in the literature.9,10

| Barua ET AL | Boyer ET AL9 | Gbadegesin ET AL10 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of families with INF2 mutations | 20 | 9 | 8 |

| Total number of families tested | 215 | 54 | 49 |

| Percentage of families with INF2 mutations | 9 | 17 | 16 |

| Number of sporadics with INF2 mutations | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Total number of sporadics tested | 281 | 84 | 31 |

| Percentage of sporadics with INF2 mutations | 0.7 | 1 | 0 |

Table 2.

List of INF2 heterozygous missense mutations by family and in silico protein function prediction according to Polyphen-2 software. Mutations that were found in other families, either in our cohort or published in the literature, are indicated.

| Family ID | Exon Number | Nucleotide Change | Amino Acid Change | Polyphen-2 Prediction | Polyphen-2 Score | Found in other cohorts? | Previously Reported? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FG-BR | 4 | c.556T>C | p.S186P | Probably damaging | 0.988 | Y | Y11 |

| FG-DM | 4 | c.593T>G | p.L198R | Probably damaging | 0.995 | Y | Y9 |

| FG-EA | 4 | c.652C>T | p.R218W | Probably damaging | 1.000 | Y | Y11 |

| FG-EF | 4 | c.641G>A | p.R214H | Probably damaging | 1.000 | Y | Y9,10 |

| FG-EP | 2 | c.125T>C | p.L42P | Probably damaging | 0.995 | N | Y11 |

| FG-ER | 4 | c.556T>C | p.S186P | Possibly damaging | 0.789 | Y | Y11 |

| FG-FG | 4 | c.641G>A | p.R214H | Probably damaging | 1.000 | Y | Y9-11 |

| FG-GY | 4 | c.550G>A | p.E184K | Probably damaging | 0.999 | Y | Y10 |

| FG-HT | 3 | c.472C>G | p.H158D | Probably damaging | 1.000 | N | N |

| FG-JN | 4 | c.653G>A | p.R218Q | Probably damaging | 1.000 | Y | Y9-11 |

| FG-JY | 4 | c.640C>T | p.R214C | Probably damaging | 1.000 | Y | N9,10 |

| FG-KM | 2 | c.217G>A | p.G73S | Probably damaging | 0.999 | N | N |

| FG-KQ | 4 | c.653G>A | p.R218Q | Probably damaging | 1.000 | Y | N9-11 |

| FG-LL | 4 | c.542T>G | p.V181G | Probably damaging | 0.989 | N | N |

| FG-LP | 4 | c.529C>T | p.R177C | Probably damaging | 1.000 | N* | N9,10 |

| FG-LW | 4 | c.653G>A | p.R218Q | Probably damaging | 1.000 | Y | N9-11 |

| FG-LY | 3 | c.451T>C | p.C151R | Probably damaging | 1.000 | N | N |

| FG-ME | 4 | c.652C>T | p.R218W | Probably damaging | 1.000 | Y | N9-11 |

| FS-B | 4 | c.658G>A | p.E220K | Probably damaging | 0.999 | N | Y9,18 |

| FS-V | 2 | c.242T>C | p.L81P | Probably damaging | 0.995 | N | N11 |

An asterisk (*) indicates that this residue has been mutated in other families with FSGS but to a different amino acid. Families that were reported in our original INF2 discovery paper published in 2009 are also shown.11 Alterations in nucleotide and amino acid sequence are reported using the following NCBI RefSeq accession numbers: INF2 – NM_022489 and NP_071934.

Table 3.

List of INF2 heterozygous variants found in sporadic individuals with FSGS and in silico protein function prediction according to Polyphen-2 software. Alterations in nucleotide and amino acid sequence are reported using the following NCBI RefSeq accession numbers: INF2 – NM_022489 and NP_071934.

| Affected Individual | Exon Number | Nucleotide Change | Amino Acid Change | Polyphen-2 Prediction | Polyphen-2 Score | Found in other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FG-FU 13 | 2 | c.305_314delTCAGCTGCG | p.del102_104VSC | N/A | N/A | No |

| CPMC 105 | 2 | c.385T>C | p.S129P | Probably damaging | 0.895 | No |

Figure 1.

Summary of INF2 substitutions, with red representing affected residues reported in families with FSGS and green representing residues reported to be altered in individuals with CMT disease. Disease-segregating alterations shown aligned with wild-type INF2 protein sequence from humans, gorilla, bovine, horse, mouse and chicken. All of the disease alterations occur in evolutionarily conserved residues.11

Some of the mutations identified in our cohort have been described before, whereas others are novel (Tables 2 and 3). Certain codons appear to be hot spots for mutations.9, 10, 17–19 For example, five families have a mutation affecting arginine at the 218th position. Three of these families share the p.R218Q mutation while two share the p.R218W mutation. None of these families are known to be related and this mutation has been described by other groups as well. Mutations in the arginine at the 214th position are also frequently seen in our cohort and others; two of our families have an arginine to histidine mutation and one family has an arginine to cysteine mutation. Finally, two families share the p.S186P mutation but are not known to be closely related.

Though we believe that there are certain “hotspots” for mutations, an alternative explanation is that these mutations could have been passed from a common ancestor. However, in family FG-JN, with the recurrent mutation p.R218Q, the mutation appears to have arisen de novo in an apparent founder individual within the pedigree. We do not have this individual’s DNA sample but several of his unaffected siblings share the haplotype on which the mutation is found in later generations (data not shown). These unaffected siblings do not harbor the mutation thus suggesting that their affected sibling is the founder.

Our clinical data suggests that affected families are predominantly Caucasian, though this may reflect bias in our cohort. Affected individuals who have had a kidney biopsy generally show focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, usually of the not otherwise specified variant but collapsing in one instance, on histology. Affected individuals generally develop disease during adolescence or early adulthood, which frequently leads to end-stage renal disease in the third or fourth decades of life (Table 4). Ages of onset for renal disease and ESRD ranged from 8 to 72 years and 13 to 67 years, respectively. Most of the families were moderately sized, with 2 to 19 affected individuals per family.

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics for the 20 families affected with INF2-related disease.

| Family ID | Self-reported Ethnicity/Country | Ages at disease onset | Number affected | Ages at ESRD | Number with ESRD | Histology | Number with Biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FG-BR | European ancestry/Canada | 12–67 | 19 | 32–67 | 6 | FSGS | 7 |

| FG-DM | European ancestry/Ireland and USA | 13–18 | 2 | 21–29 | 2 | FSGS | 2 |

| FG-EA | African American/USA | 27–33 | 3 | 30–40 | 2 | FSGS | 1 |

| FG-EF | European ancestry/USA | 19–35 | 5 | 49 | 1 | FSGS | 3 |

| FG-EP | European ancestry/USA | 11–13 | 3 | 13–14 | 3 | FSGS | 3 |

| FG-ER | European ancestry/Canada | 13–60 | 9 | 20–50 | 6 | Unclear | 3 |

| FG-FG | European ancestry/USA | 12–72 | 7 | 17–60 | 3 | FSGS | 3 |

| FG-GY | African American/USA | 17–30 | 8 | 17–30 | 7 | FSGS | 2 |

| FG-HT | European ancestry/USA | 13–29 | 9 | 21–22 | 9 | FSGS | 4 |

| FG-JN | European ancestry/USA | 22–45 | 10 | 30–45 | 4 | FSGS | At least 1 |

| FG-JY | European ancestry/Australia | 21-? | 2 | 35 | 1 | FSGS | 3 |

| FG-KM | European ancestry/Poland | 15–24 | 4 | 25–44 | 2 | FSGS | 2 |

| FG-KQ | Asian/USA | ? | 2 | 26-? | 2 | FSGS | 1 |

| FG-LL | European ancestry | 19 | 2 | 19 | 1 | FSGS | At least 1 |

| FG-LP | European ancestry/USA | 17–27 | 4 | 25–28 | 3 | FSGS | 1 |

| FG-LW | European ancestry | 22–30 | 4 | 27–30 | 3 | FSGS | 1 |

| FG-LY | European ancestry/France | 18 | 4 | 33 | 3 | FSGS | 1 |

| FG-ME | European ancestry | 15–16 | 3 | - | 0 | FSGS | 1 |

| FS-B | European ancestry/USA | 13–21 | 5 | 23–30 | 4 | FSGS | 3 |

| FS-V | European ancestry/Sweden and Denmark | 15 | 6 | 30 | 2 | FSGS | 1 |

Disease penetrance is variable. Within families, there are rare individuals who harbor the variant but remain clinically unaffected into their sixth and seventh decades of life. Urine screening has revealed microalbumin ratios >250mg/g creatinine in some of these asymptomatic individuals. There are rare individuals who carry a mutation but have no proteinuria. There was at least one adult without any proteinuria.

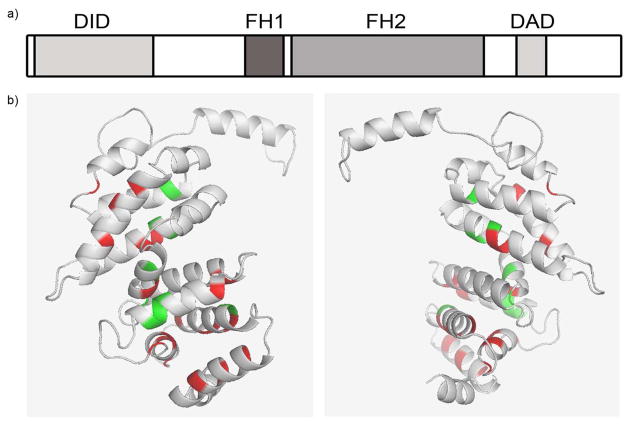

Of note, one affected female individual from family FS-V with the p.L81P variant developed motor weakness but the cause was unclear. She was diagnosed with FSGS at the age of 15 and developed ESRD at the age of 30. In light of the recent publication linking Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) to INF2 mutations, she is undergoing further evaluation for this disorder.17 The INF2 mutations described in individuals with CMT disease with associated FSGS do not overlap with individuals with familial FSGS (Figure 2). The underlying mechanism causing individuals with INF2 mutations to develop kidney disease and/or neurological manifestations as part of CMT disease still remain unknown.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic showing INF2 protein domain structure. All INF2 mutations identified thus far occur in exons 2 to 4, which localizes to the diaphanous inhibitory domain (DID) of the protein, albeit only exons 2 to 5 were sequenced in the majority of individuals in our cohort. FH1/2 = formin homology domains 1 and 2, DAD = diaphanous activating domain (b) Three dimensional model of the first 234 amino acids of INF2 as modeled in Phyre2.29 Affected residues identified in families with FSGS are indicated in red. All known pathogenic mutations cluster in the DID, represented by grey ribbons. Green represents residues mutated in individuals with CMT disease. Figure was generated using PyMOL (DeLano, W.L. The PyMOL molecular graphics system 2002).

Of the 281 sporadic individuals screened, 2 INF2 mutations were identified. One was a mutation in exon 2 leading to a serine to proline change at the 129th position, which was not found in control chromosomes. The other mutation was a heterozygous in-frame 9 base pair deletion (c.305_314delTCAGCTGCG, p.del102_104VSC) in exon 2. This individual was diagnosed with primary FSGS on biopsy but also has a long standing history of sarcoidosis involving the skin. Four unaffected individuals from this family, including both parents, were also sequenced and not found to have this variant thereby indicating it to be de novo.

Examination of the burden of coding variants in the entire INF2 gene documented in the 1000 Genomes Project and the Exome Sequencing project is telling in that the ratio of non-synonymous (NS) to synonymous (S) variants in exons 6 to 22 is higher than the ratio for exons 2 to 5 in both datasets. In the 1000 Genomes project, this ratio is 36/20 for exons 6 to 22 and 1/9 for exons 2 to 5 (p=0.002 by right-tailed Fisher Exact test). Similarly, in the Exomes Sequencing Project, the ratios are 57/38 versus 4/9, in exons 6 to 22 and exons 2 to 5, respectively (p=0.045 by right-tailed Fisher Exact test). This suggests that coding variants in exons 2 to 5 of INF2 are less tolerated than coding variants in exons 6 to 22, resulting in a higher rate of purifying selection in the first coding exons.

Sequencing by Sanger and next generation method of known autosomal dominant FSGS genes—ACTN4, TRPC6, and CD2AP—was also performed in 213 probands. Only the first 10 exons of the ACTN4 gene were sequenced by Sanger method given that all disease-causing mutations have been localized to this part of the gene.5, 6 Novel missense variants in ACTN4 and TRPC6 that segregated were identified in 7 and 5 or 3% and 2% of families, respectively (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). No novel variants were found in CD2AP. These variants were not present in any of the 10800 control chromosomes assayed or referenced in dbSNP, 1000 Genomes Project or in the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s Exome Sequencing Project.

DISCUSSION

The most recent gene to be identified as causing a form of autosomal-dominant FSGS is inverted formin 2 (INF2).11 Mutations in this gene have been demonstrated to be a major cause of autosomal dominant FSGS, previously reported to account for up to 16% to 17% of familial cases.9, 10 We report a lower proportion of INF2-related disease, 9%, in a larger familial cohort than has been previously tested. We also show it to be a more common, albeit still minor, monogenic cause of FSGS when compared to other known gene culprits including ACTN4, TRPC6, and CD2AP. Conversely, similar to other reports, our results indicate that mutations in INF2 are rarely found in sporadic cases of FSGS, with only 2 identified cases in our cohort of 281 sporadic individuals.

Identified variants in INF2, ACTN4, TRPC6, and CD2AP were ultimately determined to be disease-causing if they a) segregated with disease b) were not present in control chromosomes in dbSNP, 1000 Genomes Project and the Exome sequencing project and 3) predicted to be damaging by in silico analysis. For each mutation, every affected individual tested for whom we had a DNA sample harbored the variant. For INF2, there were occasional family members who carried the family variant and had asymptomatic proteinuria or indeterminate microalbuminuria (25–250 mg/g creatinine). Many of these individuals are children and may not have manifested clinical disease yet, however, there are rare adults with disease-associated mutations who do not have clinical kidney disease.

We include in this report a list of all INF2, ACTN4, and TRPC6 mutations found in screening our expanded cohort of autosomal dominant families with FSGS, including those published earlier as part of the initial discovery of these genes.5–7, 11 Most of the mutations are missense with only one structural variant in a sporadic case—a finding that is not surprising given the significantly higher frequency of missense variants in the human genome. We now exclude two missense variants previously reported as disease-causing, INF2 p.A13T and TRPC6 p.N143S as both have now been discovered in controls in the Exome sequencing project (Exome Variant Server, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA (URL: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) [date (January, 2011) accessed]).

The recessive gene, NPHS2 or podocin, has also been previously sequenced in the sporadic cohort given that it has been found in sporadic cases of FSGS, though usually in children.19 Novel missense variants in NPHS2 were identified in 6 or 3% of sporadic individuals.20 One deletion was detected in NPHS2.20

The new INF2 families we have identified since our first report of INF2 mutations have a similar phenotype. Our current data continue to support the trend that individuals with INF2-related disease typically present in the second to fourth decade of life with onset of renal failure in the third decade. However, there continues to be wide inter-family and intra-family variability for ages at which disease onset and ESRD occurs. There were several cases of affected children manifesting proteinuria and ESRD in adolescence, suggesting that INF2 should be considered in the pediatric population as well.

Previous work on genes identified as causing familial forms of nephrotic syndrome and/or FSGS such as ACTN4, TRPC6, and CD2AP highlight the importance of the podocyte slit diaphragm and actin cytoskeleton in the pathogenesis of disease.5, 21–25 INF2 is also highly expressed in the podocyte and belongs to the formin family, a group of heterogeneous actin binding proteins that regulate a variety of cytoskeleton-dependent cellular processes.12–16 INF2, in particular, is known to accelerate both actin polymerization and depolymerization. Our work on the initial INF2 discovery families showed that all mutations were contained within the diaphanous inhibitory domain (DID), suggesting an important role for this domain in its signaling pathway (Figure 2).11 Furthermore, the burden of coding variants in the entire INF2 gene documented in the 1000 Genomes Project and the Exome Sequencing project is weighted to outside of the DID, suggesting that coding variants in exons 2 to 5 of INF2 are less tolerated than coding variants in exons 6 to 22. The INF2 protein exists in 3 isoforms, 2 of which are long forms and 1 of which is a short form lacking the C-terminal portion downstream from the DID. Thus, we hypothesize that there is something inherently more biologically relevant about the short splice variant (NM_032714) of INF2 compared to the long splice variants (NM_022489 and NM_001031714). Given that only INF2 exons 2 to 5 were sequenced in this study, it is possible that mutations outside of the DID have been missed. However, previous studies sequencing the entire INF2 gene have localized mutations to this domain only, suggesting that mutations outside of the DID domain are relatively infrequent if they exist at all.9–11, 17–19

INF2’s depolymerization activity is regulated via an autoinhibitory interaction of its DID with its diaphanous autoregulatory domain (DAD).26 Subsequent work has shown that INF2-DID interacts with the DAD of the mammalian diaphanous-related formins (mDias), which are a family of Rho effectors that also regulate actin dynamics27. INF2 bearing the p.E184K, p.S186P and p.R218Q mutations decreased the binding affinity of INF2 DID with the mDia DAD.28 We hypothesize that mutations within the DID domain of INF2 may interrupt the binding conformation of INF2 to the DAD domains of itself and the mDias leading to altered cytoskeletal rearrangements. To date, all FSGS-associated INF2 mutations alter highly conserved residues within the DID domain.

Familial studies have yielded significant insight into our current understanding of FSGS. Despite the fact that mutations in INF2 do not contribute significantly to sporadic disease, they are a relatively common cause of familial FSGS. The lessons learned from the biological study of INF2 and disease-causing INF2 mutations are likely to be relevant to the broader patient population with sporadic disease. Though the primary insult leading to disease may be different, the downstream effects leading to altered actin dynamics and glomerulosclerosis may reveal common targets for therapy.

Thus, mutations in INF2 explain a greater, albeit still minor, proportion of hereditary FSGS compared to ACTN4, TRPC6 and CD2AP while not contributing significantly to sporadic disease. INF2-related disease has variable penetrance, presenting in the second to fourth decades of life, though childhood onset has also been documented. INF2 mutations cluster in exons 2 to 4, representing the DID domain, and highlights the importance of this domain and its ability to regulate actin assembly and disassembly in the podocyte.

METHODS

Patients

A total of 912 individuals belonging to 215 families and 281 sporadic cases of FSGS were included in this study. Familial cases were defined as 2 or more affected individuals. All families had an inheritance pattern consistent with autosomal dominance. Affected status was defined as having either a reported history of nephrotic syndrome or biopsy-proven FSGS, having documented proteinuria with urine microalbumin >250mg/g creatinine in a family with at least one case of documented FSGS or nephrotic syndrome. We obtained blood, sputum, or isolated DNA and clinical information after receiving informed consent from participants in accordance with the Institutional Review Board at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Clinical information was obtained from telephone interviews, questionnaires and physician reports.

Mutation Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from blood or sputum samples using standard procedures. For INF2, mutational screening was restricted to exons 2, 3, 4 and 5. As positive controls, we included families in which INF2 mutations had been previously identified. The first 10 of 21 exons in ACTN4 were sequenced. All 13 exons in TRPC6 and 18 exons in CD2AP were screened. Sanger sequencing was performed using Big Dye terminator cycle sequencing kit and analyzed with an ABI Prism 3130 XL DNA analyzer. Primer sequences are available on request. Sequence chromatograms were analyzed using the Sequencher software (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI). INF2 was sequenced in all probands and sporadic cases. A minority of the probands had next generation sequencing performed. A shotgun sequencing library for each sample was constructed and captured using either the Nimblegen 2.1M Human Exome kit or the Nimblegen SeqCap EZ Exome v2. Enriched libraries were then sequenced on a GAII. The potential pathogenicity of variants were assessed in silico using PolyPhen-2 software analysis (http://genetics/bwh.harvard.edu/pph2). Variants were compared against dbSNP 134 (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/snp/organisms/human_9606/VCF/v4.0/00-All.vcf.gz), 1,000 Genomes Project (ftp://ftp-trace.ncbi.nih.gov/1000genomes/ftp/release/20110521/ALL.wgs.phase1_intergrated_calls.20101123.snps_indels_svs.sites.vcf.gz) and the Exome Sequencing Project (Exome Variant Server, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA (URL: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) [(January 2012) accessed]). Where a novel variant was identified in a family, all available affected and unaffected family members were sequenced to investigate if the variant segregated with disease. If any affected individual of a family did not harbor the variant of interest, it was excluded as disease-causing.

Structural Model

Three-dimensional models of the human INF2 (amino acids 1 through 234) were designed using the Phyre2 threading program based on primary sequence conservation and known protein structures.29 The model was manipulated using the program PyMOL (DeLano, W.L. The PyMOL molecular graphics system 2002).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (DK54931 to M.R.P and 5K12HDO52896 to E.B.). This data was presented at the ASN in poster form. M.B. is supported by a training fellowship from the Kidney Research Scientist Core Education and National Training Program, Canadian Society of Nephrology, and Canadian Institutes of Health Research. E.B. was also supported by a fellowship from the NephCure foundation.

We thank the families for their participation. The authors would like to thank Andrea Uscinski Knob, MSc, for her assistance in obtaining clinical information from some of the families. The authors would also like to thank the NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project and its ongoing studies which produced and provided exome variant calls for comparison: the Lung GO Sequencing Project (HL-102923), the WHI Sequencing Project (HL-102924), the Broad GO Sequencing Project (HL-102925), the Seattle GO Sequencing Project (HL-102926) and the Heart GO Sequencing Project (HL-103010).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

+Moumita Barua, MD1: None

+Elizabeth J. Brown, MD1,2: E.J.B is named as an inventor of a genetic test for INF2 mutations

Victoria T. Charoonratana, BSc1,2: None

Giulio Genovese, PhD1: None

Hua Sun, MD1: None

Martin R. Pollak, MD1: M.R.P is named as an inventor of a genetic test for INF2 mutations

References

- 1.Simon P, Ramee MP, Boulahrouz R, et al. Epidemiologic data of primary glomerular diseases in western France. Kidney international. 2004;66:905–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briganti EM, Dowling J, Finlay M, et al. The incidence of biopsy-proven glomerulonephritis in Australia. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2001;16:1364–1367. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.7.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haas M, Spargo BH, Coventry S. Increasing incidence of focal-segmental glomerulosclerosis among adult nephropathies: a 20-year renal biopsy study. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1995;26:740–750. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90437-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitiyakara C, Eggers P, Kopp JB. Twenty-one-year trend in ESRD due to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in the United States. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2004;44:815–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan JM, Kim SH, North KN, et al. Mutations in ACTN4, encoding alpha-actinin-4, cause familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nature genetics. 2000;24:251–256. doi: 10.1038/73456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weins A, Kenlan P, Herbert S, et al. Mutational and Biological Analysis of alpha-actinin-4 in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2005;16:3694–3701. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005070706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiser J, Polu KR, Moller CC, et al. TRPC6 is a glomerular slit diaphragm-associated channel required for normal renal function. Nature genetics. 2005;37:739–744. doi: 10.1038/ng1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liakopoulos V, Huerta A, Cohen S, et al. Familial collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clinical nephrology. 2011;75:362–368. doi: 10.5414/cn106544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyer O, Benoit G, Gribouval O, et al. Mutations in INF2 are a major cause of autosomal dominant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2011;22:239–245. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gbadegesin RA, Lavin PJ, Hall G, et al. Inverted formin 2 mutations with variable expression in patients with sporadic and hereditary focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney international. 2012;81:94–99. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown EJ, Schlondorff JS, Becker DJ, et al. Mutations in the formin gene INF2 cause focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nature genetics. 2010;42:72–76. doi: 10.1038/ng.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krebs A, Rothkegel M, Klar M, et al. Characterization of functional domains of mDia1, a link between the small GTPase Rho and the actin cytoskeleton. Journal of cell science. 2001;114:3663–3672. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupton SL, Eisenmann K, Alberts AS, et al. mDia2 regulates actin and focal adhesion dynamics and organization in the lamella for efficient epithelial cell migration. Journal of cell science. 2007;120:3475–3487. doi: 10.1242/jcs.006049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bindschadler M, McGrath JL. Formin’ new ideas about actin filament generation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:14685–14686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406317101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang C, Czech L, Gerboth S, et al. Novel roles of formin mDia2 in lamellipodia and filopodia formation in motile cells. PLoS biology. 2007;5:e317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chhabra ES, Ramabhadran V, Gerber SA, et al. INF2 is an endoplasmic reticulum-associated formin protein. Journal of cell science. 2009;122:1430–1440. doi: 10.1242/jcs.040691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyer O, Nevo F, Plaisier E, et al. INF2 mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease with glomerulopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:2377–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HK, Han KH, Jung YH, et al. Variable renal phenotype in a family with an INF2 mutation. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:73–76. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1644-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santin S, Bullich G, Tazon-Vega B, et al. Clinical utility of genetic testing in children and adults with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2011;6:1139–1148. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05260610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tonna SJ, Needham A, Polu K, et al. NPHS2 variation in focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. BMC nephrology. 2008;9:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kestila M, Lenkkeri U, Mannikko M, et al. Positionally cloned gene for a novel glomerular protein--nephrin--is mutated in congenital nephrotic syndrome. Molecular cell. 1998;1:575–582. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boute N, Gribouval O, Roselli S, et al. NPHS2, encoding the glomerular protein podocin, is mutated in autosomal recessive steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Nature genetics. 2000;24:349–354. doi: 10.1038/74166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winn MP, Conlon PJ, Lynn KL, et al. A mutation in the TRPC6 cation channel causes familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Science. 2005;308:1801–1804. doi: 10.1126/science.1106215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hinkes B, Wiggins RC, Gbadegesin R, et al. Positional cloning uncovers mutations in PLCE1 responsible for a nephrotic syndrome variant that may be reversible. Nature genetics. 2006;38:1397–1405. doi: 10.1038/ng1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shih NY, Li J, Karpitskii V, et al. Congenital nephrotic syndrome in mice lacking CD2-associated protein. Science. 1999;286:312–315. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chhabra ES, Higgs HN. INF2 Is a WASP homology 2 motif-containing formin that severs actin filaments and accelerates both polymerization and depolymerization. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:26754–26767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604666200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose R, Weyand M, Lammers M, et al. Structural and mechanistic insights into the interaction between Rho and mammalian Dia. Nature. 2005;435:513–518. doi: 10.1038/nature03604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun H, Schlondorff JS, Brown EJ, et al. Rho activation of mDia formins is modulated by an interaction with inverted formin 2 (INF2) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:2933–2938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017010108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ. Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nature protocols. 2009;4:363–371. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.