Abstract

Objective

This study determined whether kinesiophobia levels were different among older adults with chronic low back pain (LBP) and varying body mass index (BMI) and whether kinesiophobia predicted perceived disability or walking endurance.

Design

This study was a secondary analysis from a larger interventional study. Obese, older adults with LBP (N=55; 60-85 years) were participants in this study. Data were stratified based on BMI: overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2), obese (30-34.9 kg/m2) and severely obese (35 kg/m2). Participants completed a battery of surveys (modified Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia [TSK-11], Fear Avoidance Beliefs [FAB], Pain Catastrophizing scale [PCS], and perceived disability measures of the Oswestry Disability Index [ODI], Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire [RMDQ]). Walking endurance time was captured using a symptom limited graded walking treadmill test. Peak LBP ratings were captured during the walk test.

Results

Walking endurance times did not differ by BMI group, but peak LBP ratings were higher in the moderate and severely obese groups compared to the overweight group (3.0 and 3.1 points vs. 2.1; p<0.05). There were no difference in the kinesiophobia scores (TSK-11, PCS, FAB work and activity subscores) or the perceived disability scores (ODI, RMD). However, adjusted regression analyses revealed that TSK-11 scores contributed 10-21% of the variance of the models pain with walking and perceived disability due to back pain. Kinesiophobia was not a significant contributor to the variance of the regression modeling for walking endurance.

Conclusions

In the obese older population with LBP, the TSK-11 might be a quick and simple measure to identify patients at risk for poor self-perception of functional ability The TSK and ODI may be quick useful measures to assess initial perceptions before rehabilitation. Kinesiophobia may be a good therapeutic target to address to help affected obese older adults fully engage in therapies for LBP.

Keywords: Low Back Pain, Obesity, Kinesiophobia, Multifidus

Obese persons incur musculoskeletal challenges including disabling joint pain, functional impairment and difficulty walking.1 The prevalence of joint pain increases with higher body mass index (BMI) values, especially in load bearing segments such as the low back.2 Pain influences obesity-induced impairments of physical function and mobility, which contribute to health decline. Among physical tasks, maintenance of walking ability in advanced age is important for several reasons: walking endurance correlates with disability risk,3 is influenced by LBP4 and is a main exercise mode for older and obese adults and for chronic back pain. A loss of walking ability compromises overall health and quality of life.

There are several psychosocial characteristics that may influence LBP-related pain during walking. Among these characteristics, fear of movement due to pain (kinesiophobia) has emerged as a characteristic consistently related to back pain severity and perceived disability.5 Pain catastrophizing and fear avoidance beliefs are likely involved with chronic LBP. Catastrophizing and fear avoidance behaviors may perpetuate a cycle of physical activity aversion, thereby worsening mobility and functional limitations. With aging, the duration of LBP episodes increases.6 Older adults with high BMIs and chronic LBP may report higher kinesiophobia levels, have higher perceived disability due to LBP, and subsequently may incur greater mobility impairment than persons with lower BMIs. At present, the relationships between kinesiophobia, perceived disability and mobility in the obese older adult are not clear. Limited data show that persons with chronic LBP who sought physical therapy for back pain, kinesiophobia scores were moderately higher in obese compared to non-obese persons.7 Furthermore, kinesiophobia enhanced the prediction of self-reported disability.7 Expanding our understanding of the relationships between kinesiophobia, walking mobility and pain will facilitate development of targeted therapy approaches for chronic LBP and its related psychosocial factors in the growing obese, older demographic. Thus, the purpose of this study was to determine whether or not kinesiophobia levels were different among older adults with LBP and varying BMI values, and whether kinesiophobia was related to LBP, perceived disability and walking endurance. We hypothesized that: 1) participants with higher body mass index (BMI) values would demonstrate higher levels of pain with walking, and 2) kinesiophobia levels would be inversely related with walking endurance and would be directly related with LBP severity and perceived disability.

METHODS

As described in Part I, the companion paper, we recruited participants with chronic, diffuse low back pain from the Gainesville, FL and surrounding communities. This study was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board, and all procedures on human subjects were conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. All participants read, understood and signed an informed consent document.

Back Pain Symptoms, Other Joint Pain and Pain Treatments

To examine whether the low back pain symptoms were different across BMI groups, each participant was asked whether specific activities elicited low back pain, including: bending forward and backward, twisting side to side, turning and twisting, standing or sitting still, walking, lying down, sitting down and standing up. Because kinesiophobia might be influenced by the presence of joint pain in other sites besides the low back, we asked each participant about the presence of pain in the following joints: neck, shoulder, elbow, wrist/ hand, hip, knee and ankle/foot. Each participant reported the use of any prior treatments for LBP. Categories of main treatments included over the counter medications, relaxation-meditation, massage, prayer, chiropractic, surgery, nutritional aids (micronutrients, herbs, glucosamine/chondroitin) and steroid injections.

Graded Treadmill Walking Exercise Test

The participant’s maximal aerobic fitness, or rate of oxygen consumption (VO2max) was determined using a walking symptom-limited graded exercisetest (modified incremental treadmill Naughton).8 All tests followed the guidelines of the American College of Sports Medicine,9 with electrocardiogram heart monitoring and periodic blood pressure measures. Open-circuit spirometry was used to determine VO2 and carbon dioxide production. Back pain symptoms and severity were collected using the numerical pain rating scale (NRSpain) before exercise, every two minutes during exercise with workload change and every two minutes during recovery. Peak pain ratings are reported in the results, as these ratings corresponded with the highest treadmill workload. Walking time until voluntary exhaustion or pain limitation was recorded. Rating of perceived exertion values were collected at rest, at each exercise stage and during recovery.9

Kinesiophobia and Fear Avoidance Beliefs

The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK-11) was used to measure fear of movement or re-injury. The TSK questionnaire assesses fear of movement/re-injury and has invariance across different clinical conditions and patient populations.10 Each survey question is provided with a 4-point Likert scale with scoring alternatives ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”11 The TSK-11 consists of two lower order factors, Somatic Focus and Activity Avoidance Focus.10 The “Somatic Focus” represents the belief of underlying and serious medical problems, and the “Activity Avoidance Focus” represents the belief that activity may result in (re)injury or increased pain.12 Thus, the overall TSK score and the two subscores of Somatic Focus and Activity Avoidance are presented. Second, the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) is a tool based on theories of fear and avoidance behavior and focuses specifically on beliefs about how physical activity and work affect low back pain.13 Internal consistency of the TSK and FABQ scores range from α=0.70 to 0.83 in individuals with low back pain. Test-retest reliability ranges from r=0.64 to 0.80, and concurrent validity is moderate, ranging from r=0.33 to 0.59.14 Third, the pain catastrophizing scale (PCS)15 was used to assess the effect of the chronic back pain on rumination on pain symptoms and helplessness.

Perceived Disability Due to LBP

Perceived disability due to LBP was assessed using two surveys, the modified Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (ODI) and the Roland Disability Survey. The ODI16 focuses on the self reported intensity of low back pain, and the effects of low back pain on personal care, sitting, standing, sleeping, walking, traveling, sex life and social life. This version of the Oswestry survey is responsive to intervention treatments for low back pain, is reliable with an intraclass coefficient value of 0.90, and corresponds well with several global patient disability measures.16, 17 The Roland Disability Survey assesses physical disability and mental function with low back pain; this survey is reproducible and consistent and correlated well with other global ratings and disability measures.17

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; v.20.0). Data were managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture).18 Non-parametric Kruskal Wallis tests were used to determine whether the three BMI groups responded differently to the survey instruments. To determine the contribution of kinesiophobia to the variance of the regression models for pain severity during walking, perceived disability due to LBP and walking endurance time, hierarchical regression models were generated. Models were generated by first entering factors that likely affect pain severity (age, gender, race and BMI), and then the TSK scores were added. Different models were generated for each independent variable. Addition of the PCS and FAB questionnaire sores were also added to the regression models to determine whether these scores enhanced the predictive ability of the model for the dependent variables. Significance was established at p<0.05 for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

As described in our companion paper (Part I) other than BMI, waist circumference and body weight, no other differences were detected in group characteristics across the three BMI groups (p<0.05).

LBP Symptoms, Other Joint Pain and Treatments for LBP

There were no differences in the proportions of participants who reported pain in the joints listed (Table 1). Irrespective of BMI, participants reported experiencing pain most commonly in the neck, hip and knee. There were also no differences in the proportions of patients reporting pain with different spine motions. Among the BMI groups, however, walking was identified as a one of the top three triggers for inducing pain. There were no significant differences in the proportions of participants who reported use of various treatments for LBP (Table 2). Overall, these participants experienced similar LBP and self-treatment methods.

Table 1.

Presence of pain symptoms in other joint sites and during specific activities. Values are % of the group.

| Overweight | Moderately Obese |

Severely Obese |

p value (sig) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you have pain in the following sites? (% yes) | ||||

| Neck | 55.0 | 48.4 | 55.6 | 0.85 |

| Shoulder | 40.0 | 48.4 | 38.9 | 0.76 |

| Elbow | 15.0 | 16.1 | 16.7 | 0.99 |

| Wrist/ hand | 50.0 | 35.5 | 38.9 | 0.58 |

| Hip | 60.0 | 64.5 | 66.7 | 0.91 |

| Knee | 55.0 | 58.1 | 66.7 | 0.75 |

| Ankle/ foot | 35.0 | 29.0 | 38.9 | 0.77 |

| Do these motions cause your back to hurt? (% yes) | ||||

| Bend forward | 55.0 | 61.3 | 61.1 | 0.89 |

| Bend backwards | 45.0 | 41.9 | 38.9 | 0.93 |

| Twist side to side | 35.0 | 54.8 | 61.1 | 0.23 |

| Turn and twist | 45.0 | 48.4 | 22.2 | 0.18 |

| Stand still | 70.0 | 48.4 | 72.2 | 0.16 |

| Sit still | 45.0 | 51.6 | 55.6 | 0.81 |

| Walk | 60.0 | 74.2 | 61.1 | 0.49 |

| Lie down | 55.0 | 38.7 | 72.2 | 0.07 |

| Stand up | 55.0 | 48.4 | 44.4 | 0.81 |

| What hurts the most? (three most painful actions, % of group) | ||||

| Stand up, 20.0 | Bend forward, 16.1 | Bend forward, 27.8 | ||

| Bend backward, 15.0 | Lie down, 16.1 | Stand still, 27.8 | ||

| Walk, 15.0 | Walk, 12.9 | Walk, 22.2 | ||

Table 2.

The use of different treatments for chronic low back pain. Values are % of the group who reported ‘yes’.

| Overweight | Moderately Obese |

Severely Obese |

p value (sig) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over the counter medications | 15.0 | 16.1 | 11.1 | 0.89 |

| Relaxation or meditation | 15.0 | 41.9 | 22.2 | 0.09 |

| Massage | 45.0 | 67.7 | 44.4 | 0.16 |

| Prayer | 40.0 | 48.4 | 55.6 | 0.63 |

| Chiropractic | 40.0 | 71.0 | 66.7 | 0.07 |

| Nutritional aids | 55.0 | 32.3 | 50.0 | 0.23 |

| Steroid injections | 45.0 | 22.6 | 27.8 | 0.23 |

| Surgery | 10.0 | 12.9 | 27.8 | 0.28 |

Walking Endurance, Kinesiophobia and Perceived Disability

Walking endurance values were not found to be different between the three BMI groups (14.2 ± 4.2 minutes [overweight], 12.0 ± 4.3 minutes [obese] and 11.7 ± 4.2 minutes [severely obese]). Peak pain ratings were, however, higher in the severely obese and obese groups compared with the overweight group (3.0 ± 2.3 points and 3.3 ± 2.3 points vs 2.1 ± 1.8 points; p<0.05). The survey responses for kinesiophobia, fear avoidance and self-reported disability are found in Table 3. TSK-11 total scores and Somatic Focus and Activity Avoidance subscores were not different among the three BMI groups. The FABQ responses were also not statistically different among the BMI groups. The Roland Morris Disability score and Oswestry score group differences did not attain significance.

Table 3.

Survey responses in obese, older adults with chronic low back pain. Values are means ± SD. All values are expressed in points.

| Overweight | Moderately Obese |

Severely Obese |

P (Sig) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinesiophobia and Fear Avoidance Beliefs | ||||

| TSK-11 total | 22.7 ± 7.1 | 22.6 ± 6.9 | 24.0 ± 6.3 | 0.77 |

| Somatic Focus | 11.1 ± 3.9 | 11.3 ± 3.8 | 11.5 ± 3.2 | 0.76 |

| Activity | 14.3 ± 3.7 | 13.5 ± 3.9 | 14.5 ± 3.8 | 0.79 |

| Fear Avoidance Beliefs | ||||

| Activity | 13.2 ± 7.2 | 12.1 ± 7.1 | 12.7 ± 6.9 | 0.84 |

| Work | 9.0 ± 11.5 | 12.8 ± 12.4 | 17.0 ± 14.0 | 0.29 |

| Pain Catastrophizing scale | 9.5 ± 4.1 | 8.9 ± 4.1 | 10.4 ± 4.4 | 0.52 |

| Self-reported Disability | ||||

| Oswestry Disability Index | 26.8 ± 12.4 | 28.4 ± 12.8 | 33.5 ± 11.5 | 0.14 |

| Roland Morris Disability score | 9.5 ± 4.1 | 8.8 ± 4.1 | 10.4 ± 4.4 | 0.29 |

TSK-11 point range: 11-44

Fear Avoidance Beliefs point ranges: 0-24 activity, 0-42 points work

Pain catastrophizing scale point range: 0-52

Oswestry Disability Index point range: 0-50

Roland Morris Disability point range: 0-24

Scatter Plots and Regressions

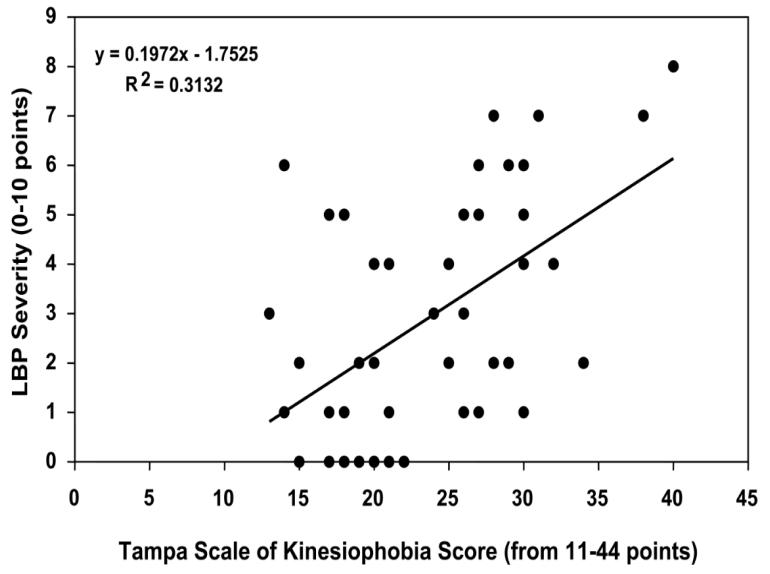

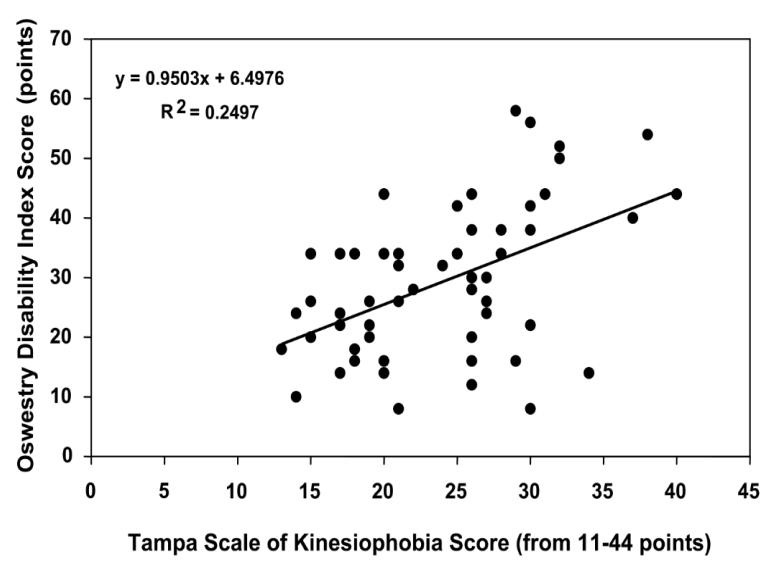

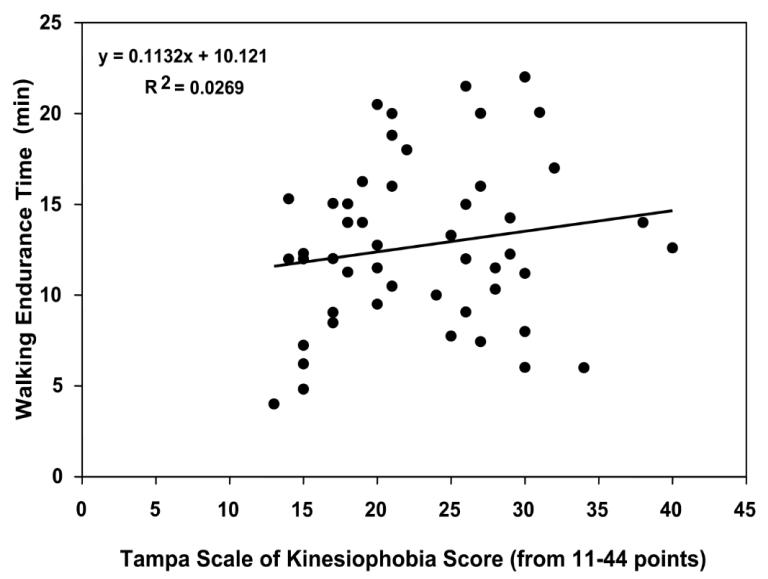

Figures 1a-1c are scatter plots of the TSK scores and LBP severity (1a), Oswestry Disability Index score (1b) and walking endurance time (1c). These graphs suggest that the correlations between kinesiophobia and perceived LBP severity and perceived disability due to back pain are high (r=0.56 and r=.50), whereas there is a poor correlation between kinesiophobia and actual walking endurance ability (r=.16). Regression analyses revealed that TSK scores contributed 10% to the variance of the model for LBP severity during walking, and ~21% of the variance of the model for perceived disability due to back pain (Oswestry score; Table 4). However, TSK scores did not significantly contribute to the regression model for walking endurance. In all regression models, the addition of pain catastrophizing scores and fear avoidance belief questionnaire scores did not significantly enhance the prediction ability for any model.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots of the TSK scores and LBP severity (1a), Oswestry Disability Index score (1b) and walking endurance time (1c).

Table 4.

Hierarchical regression analyses for LBP severity during walking (A), perceived disability due to back pain [Oswestry score] (B) and for walking endurance (C).

| A. LBP severity during walking | R | R2 | R2 Change | Significance of F Change | B (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1 Age | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Race | 0.410 | 0.168 | 0.168 | 3.838 (p=0.014) | 2.543 (0.868 to 4.218) |

| Block 2 BMI | 0.464 | 0.216 | 0.048 | 3.393 (p=0.071) | 0.111 (-0.10 to 0.231) |

| Block 3 TSK score | 0.558 | 0.312 | 0.100 | 7.696 (p=0.008) | .0115 (0.032 to .197) |

| B. Perceived Disability (ODI) | R | R2 | R2 Change | Significance of F Change | B (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1 Age | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Race | 0.271 | 0.074 | 0.074 | 1.722 (p=0.171) | 2.289 (−5.953 to 10.531) |

| Block 2 BMI | 0.361 | 0.131 | 0.057 | 4.189 (p=0.045) | 0.631 (0.015 to 1.248) |

| Block 3 TSK score | 0.582 | 0.339 | 0.209 | 19.877 (p=0.0001) | 0.865 (0.477 to 1.253) |

| C. Walking Endurance Time | R | R2 | R2 Change | Significance of F Change | B (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1 Age | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Race | 0.599 | 0.358 | 0.358 | 10.432 (p=0.0001) | −1.539 (−4.394 to 1.316) |

| Block 2 BMI | 0.671 | 0.410 | 0.091 | 9.120 (p=0.004) | −.299 (−.498 to −.101) |

| Block 3 TSK score | 0.671 | 0.410 | 0.001 | 0.001 (p=0.766) | 0.022 (−.124 to 0.167) |

Each block includes the listed variables and the addition of each previous block, and represents a separate regression equation.

B (CI) = unstandardized B coefficient and confidence interval

Sex coded = 0 male, 1 female; Race coded 1 = Caucasian, 2 = African American, 3 = Hispanic, 4 = Asian

DISCUSSION

We examined the relationships between LBP, kinesiophobia and walking ability in overweight, older adults with LBP. We hypothesized that participants with higher BMI values would have higher walking LBP, and that kinesiophobia levels would be inversely related with walking endurance and directly related with LBP severity and perceived disability. In these well-matched BMI groups, pain during walking was related to BMI, but there were no differences in fear avoidance belief scores, Roland Morris Disability scores or pain catastrophizing scores. However, regression analyses showed that TSK scores enhanced prediction of LBP severity with walking and perceived disability, but not with the walking endurance itself. In this obese older population, it appears that a mismatch exists between perception of disability (Oswestry scores) and actual walking disability. Hence, physical medicine care teams can expect that overweight and obese older adults are capable of performing walking activity, but should consider including therapeutic strategies to help individuals with kinesiophobia and high disability scores overcome their perceptions to optimize participation in rehabilitation.

In a retrospective study, we previously found that obese persons who sought physical therapy for LBP had moderately higher TSK and ODI scores compared to non-obese persons.7 We were not able to document relationships between survey responses and walking endurance (data not available). However, thoracolumbar flexion and hamstring flexion ranges did not differ based on adiposity level, and were not predicted by TSK scores.7 Here, we found that kinesiophobia indices were significant predictors of LBP severity but not of walking endurance itself. It appears that there is not a strong relationship between functional ability obtained in the laboratory and kinesiophobia. One interpretation is that variations in participant pain coping ability results in achievement of long walking times in some persons compared with others irrespective of pain intensity. We noted that some patients with average walking pain ratings of 5-7 still kept walking on the treadmill and reported that they were “used to it” and knew that “they had to walk even if it hurts.” Female gender and elevated BMI negatively predict walking distance,19 and these factors may be greater influences on walking endurance time than kinesiophobia for some participants. Thus, the lower prevalence of women our severely obese group may have reduced the ability to detect differences in walking endurance. A second explanation is that some participants may have wanted to perform better in front of the research staff in spite of kinesiophobia; this may have been especially true for men in the presence of a female staff member.

While comparative data are few, two studies reported no relationship between walking activity and TSK and Roland Morris Disability scores in persons with chronic LBP.20, 21 What may complicate the relationships between these study variables is that there are adaptive muscle activation strategies in LBP, such as guarding and activation of different muscles compared to persons without back pain.21 Potentially, a shift in the gait pattern to smaller stride length and wider stance as we reported in Part 1, may help reduce spine rotation and pain. Also, obese persons likely have other joint pains or more severe pain that might impede walking endurance independent of back pain (foot, ankle, knee), and discomforts such as respiratory difficulty and skin friction and vein varicosity.22 In the present study, we found similar distributions of bodily joint pain and types of activities that elicited pain (Table 1), but we did not capture severity of pain in the other joints.

Considerations for Future Directions

These findings will help in the development of interventions focused on minimizing psychosocial barriers to rehabilitation in obese, older persons with LBP. Prospective data collection with a larger sample size inclusive of a range of BMIs and would permit the study team to stratify analyses by multiple factors: the presence of other joint pains (knee, hips or ankle), by gender and age. The natural progression of LBP could be followed in each participant stratum to identify which physical and psychosocial characteristics affect walking endurance most over time. Interventions to combat kinesiophobia in afflicted individuals can be tested to determine the relationships between changes in fear avoidance, perceptions of disability and pain catastrophizing over time.

CONCLUSION

In this study, TSK scores moderately enhance the prediction of pain severity with walking and perceived disability due to LBP, but not with walking endurance. The TSK and ODI may be quick useful measures to assess initial perceptions before rehabilitation. Kinesiophobia may be a good therapeutic target to address to help affected obese, older adults fully engage in therapies for LBP.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This publication was made possible by Grant Number RO3 AR057552-10A1 from NIAMS/NIH. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAMS or NIH. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Florida (CTSA grant UL1 TR000064).

Funding for this project was obtained from the NIH NIAMS grant RO3 AR057552-10A1 (H. Vincent, R. Hurley, K. Vincent)

Footnotes

Disclosures: Financial disclosure statements have been obtained, and no conflicts of interest have been reported by the authors or by any individuals in control of the content of this article.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vincent HK, Ben-David K, Cendan J, Vincent KR, Lamb KM, Stevenson A. Effects of bariatric surgery on joint pain: a review of emerging evidence. Surgery in Obesity and Related Disorders. 2010;6(4):451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.03.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent HK, Vincent KR, Seay AN, Hurley RW. Functional Impairment in Obesity: A Focus on Knee and Back Pain. Pain Medicine. 2011;1(5):427–439. doi: 10.2217/pmt.11.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vestergaard S, Patel KV, Walkup MP, et al. Stopping to rest during a 400-meter walk and incident mobility disability in older persons with functional limitations. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(2):260–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyakoshi N, Kasukawa Y, Ishikawa Y, Nozaka K, Shimada Y. Spinal alignment and mobility in subjects with chronic low back pain with walking disturbance: a community-dwelling study. Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2010;221(1):53–59. doi: 10.1620/tjem.221.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crombez G, Vlaeyen JW, Heuts PH, Lysens R. Pain-related fear is more disabling than pain itself: evidence on the role of pain-related fear in chronic back pain disability. Pain. 1999;80(1-2):329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knauer SR, Freburger JK, Carey TS. Chronic low back pain among older adults: a population-based perspective. Journal of Aging and Health. 2010;22(8):1213–1234. doi: 10.1177/0898264310374111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vincent HK, Omli MR, Day TI, Hodges M, Vincent KR, George S. Fear of movement, quality of life and self-reported disability in obese patients with chronic lumbar pain. Pain Medicine. 2010;12(1):154–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincent KR, Braith RW, Feldman RA, Kallas HE, Lowenthal DT. Improved cardiorespiratory endurance following 6 months of resistance exercise in elderly men and women. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(6):673–678. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.6.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American, College, of, Sports, Medicine . ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 6 ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2000. 6 ed. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roelofs J, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH, et al. Fear of movement and (re)injury in chronic musculoskeletal pain: Evidence for an invariant two-factor model of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia across pain diagnoses and Dutch, Swedish, and Canadian samples. Pain. 2007;131(1-2):181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woby SR, Roach NK, Urmston M, Watson P. Psychometric properties of the TSK-11: a shortened version of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia. Pain. 2005;117:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roelofs J, Goubert L, Peters ML, Vlaeyen JW, Crombez G. The Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia: further examination of psychometric properties in patients with chronic low back pain and fibromyalgia. European Journal of Pain. 2004;8(5):495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993;52(2):157–168. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90127-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swinkels-Meewisse EJ, Swinkels RA, Verbeek AL, Vlaeyen JW, Oostendorp RA. Psychometric properties of the Tampa Scale for kinesiophobia and the fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire in acute low back pain. Manual Therapies. 2003;8(1):29–36. doi: 10.1054/math.2002.0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan MJL, Bishop S, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psyhcology Assessment. 1995;7:432–524. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine. 2000;25(22):2940–2952. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine. 2000;25(24):3115–3124. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture [REDCap] – A metadriven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomkins-Lane CC, Holz SC, Yamakawa KS, et al. Predictors of walking performance and walking capacity in people with lumbar spinal stenosis, low back pain, and asymptomatic controls. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2012 Feb 22; doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.09.023. (epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamoth CJ, Meijer OG, Daffertshofer A, Wuisman PI, Beek PJ. Effects of chronic low back pain on trunk coordination and back muscle activity during walking: changes in motor control. European Spine Journal. 2005;15(1):23–40. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0825-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Hulst M, Vollenbroek-Hutten MM, Rietman JS, Schaake L, Groothuis-Oudshoorn KG, Hermens HJ. Back muscle activation patterns in chronic low back pain during walking: a “guarding” hypothesis. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2010;26(1):30–37. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b40eca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hulens M, Vansant G, Claessens AL, Lysens R, Muls E. Predictors of 6-minute walk test results in lean, obese and morbidly obese women. Scandiavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 2003;13(2):98–105. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.10273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]