Systems biology is increasingly recognized for its importance to infectious disease research. From a systems-level perspective, microbe-host interactions can be better understood by taking into account the dynamical molecular networks that constitute a biological system. Reconstructed networks are modeled and refined, undergoing iterative cycles of perturbation and experimental validation. Similar to the progressive nature of the analyses, the field itself is constantly evolving. This issue of Future Microbiology highlights new developments in the field, including emerging technologies impacting ‘omic’ analyses, new applications for modeling schemes, and discovery-based endeavors seeking to uncover novel pathogens and virulence factors. Regrettably, ‘systems biology’ is often used as a blanket term, mistakenly referenced in studies utilizing only high-throughput technologies or incorporated into titles to give extra weight or novelty [1]. Integration of multiple high-throughput data types represents just a single dimension of the field necessary to elucidate host responses to infection.

What truly sets systems biology apart from these correlation studies is the use of bioinformatics to computationally model molecular networks and define relationships between pathogen and host. There are several definitions of systems biology. Some emphasize that modeling and simulation be tightly integrated with experimentation to characterize network behavior [2], while others believe that systematic perturbation of individual network components will better define relationships governing pathway function [3]. The unifying theme to these different view points is the use of computational strategies modeling information obtained from experimental models, data types and stimuli (e.g., infectious agents). With respect to infectious diseases, bioinformaticists model molecular networks to make predictions about network behavior to a pathogen. Mathematical modeling together with documented virus-host interaction data can be used to predict key network components and/or connections (e.g. ‘bottlenecks’) that can then be assessed by introducing targeted perturbations and monitoring the effects of these changes on the network as a whole. Subsequent analysis of model-based predictions using siRNA knock-down studies or knock-out animal models relate model findings to infection phenotypes and disease outcome in these experimental systems, refining models and driving further predictions.

To understand the true complexity of pathogen-host interactions, it is necessary for systems biology to 1) extend into more complex experimental models and 2) incorporate a greater breadth of high-throughput data. Small-scale studies have excelled our understanding of innate immune defenses, including recent characterization of the inflammasome as an intracellular pathogen sensor capable of activating caspase-1 [4] and P58IPK as a cellular inhibitor of host defenses during influenza infection [5]. These model systems, however, do not portray a comprehensive view of infection. Host antimicrobial responses, and conceivably the underlying mechanism(s) by which a pathogen blocks and/or modulates the activity of these responses, will be revealed in more complex models (e.g. non-human primates), aiding translational research efforts in rational drug design and vaccine development. In the case of influenza virus, macaques infected with pathogenic influenza viruses including the fully reconstructed 1918 influenza virus [6], and more recently with the highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus [7] indicates that the host response occurs early and results in enhanced levels of innate immune signaling that remain unabated. Information obtained from these studies provide a foundation to build upon using systems biology approaches with the hope of defining host mediators of early dysregulated host responses dictating later stages of immunopathology. Recent work from our laboratory using systems biology to model the impact of HCV infection on global metabolism revealed that HCV exploits the metabolic resources of liver cells to support viral replication, a process that results in massive disruption of liver cell metabolism [6]. Diamond and coworkers used mathematical modeling strategies to analyze HCV-induced changes in the protein and lipid composition of liver cells, identifying proteins that are central points for connecting and controlling metabolic pathways. This approach led to the identification of mitochondrial fatty acid enzymes as key cellular proteins targeted by HCV. The same metabolic changes observed in liver cells were also found in liver biopsy specimens taken from HCV-infected liver transplant patients that had rapid recurrence of liver fibrosis, suggesting that similar disturbances in metabolic homeostasis occur during natural infection and may contribute to liver disease progression.

High-throughput analytical techniques are constantly evolving, allowing for greater coverage in cataloguing molecular components at RNA and protein levels. Emerging technologies such as RNA-Seq [9] will greatly enrich current data sets by enhancing the detection of novel splice variants, noncoding RNA and sRNAs—all of which are receiving a great deal of attention in the virology community given their potential regulatory role during infection [10]. More recently, it has been applied to microbial systems, unveiling the transcriptome of Chlamydia trachomatis [11] and further defining the two-component regulatory system of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi involving OmpR [12]. A major pitfall of RNA-seq, however, is that over 70% of the reads map to ribosomal RNA making it particularly challenging to analyze the bacterial transcriptome. Recently, Armour and coworkers published a deep sequencing technique termed ‘not-so-random’ (NSR) priming that significantly reduces the number of reads mapping to rRNA, potentially making it easier to distinguish microbial RNA species from host cell transcripts [11]. Microarrays are diversifying. No longer are they predominantly used for transcriptional profiling. Platforms are being developed to probe protein and glycolipid repertoires of infectious agents, as described by Felgner and coworkers and Twine and coworkers, respectively, in this issue of Future Microbiology. We have demonstrated that use of microarrays to profile host miRNA expression patterns, when combined with modeling, allows identification of HCV-associated miRNA-mRNA regulatory modules that are revealed through inverse expression relationships between miRNA and mRNAs and computational target predictions [12].

It is important to take a global perspective when investigating infection and a systems biology approach to infectious disease research will lend greater understanding of the interplay between host and pathogen. Mathematical modeling of interaction networks is essential for researchers to better relate changes at the molecular level to the global properties observed within a biological system during infection. As new technologies develop and become readily available, it will expand the repertoire of information that can enrich modeling efforts. This will likely translate into more effective strategies devised to counter pathogen-mediated cellular alterations, which can consequently be the primary cause of virus pathogenesis, for example, or set the stage for cellular processes to contribute to the pathological outcome. Unless systems-level analysis is correctly pursued, the insights we hope to learn through this approach may be lost.

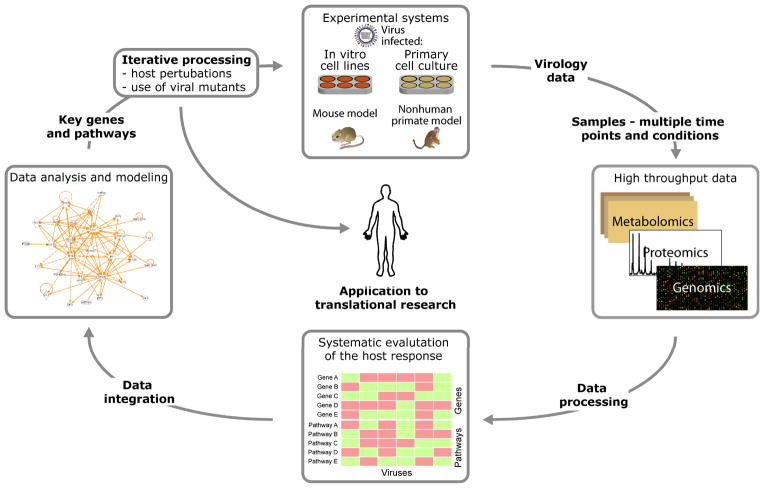

Figure 1. Iterative cycles of perturbation biology.

Identification of key genes and pathways through computational modeling schemes of diverse data types.

Acknowledgments

Research in the authors’ laboratory is supported by federal grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services under contract number HHSN272200800060C, and Public Health Service grants R01AI022646, R01HL080621, R24RR016354, P30DA015625, P01AI058113, and P51RR000166 from the National Institutes of Health, USA.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jennifer R Tisoncik, Email: tisoncik@u.washington.edu, University of Washington, Department of Microbiology, Seattle, WA 98195-8070, USA Tel.: +1 206 732 6120; Fax: +1 206 732 6056;.

Michael G Katze, Email: honey@u.washingon.edu, University of Washington, Department of Microbiology and Washington, National Primate Research Center, Box 358070, Seattle, WA, 98195-8070, USA, Tel.: +1 206 732 6135; Fax: +1 206 732 6056;.

Bibliography

- 1.Querec TD, Akondy RS, Lee EK, et al. Systems biology approach predicts immunogenicity of the yellow fever vaccine in humans. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(1):116–25. doi: 10.1038/ni.1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassman M. Barriers to progress in systems biology. Nature. 2005;438(7071):1079. doi: 10.1038/4381079a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ideker T, Thorsson V, Ranish JA, et al. Integrated genomic and proteomic analyses of a systematically perturbed metabolic network. Science. 2001;292(5518):929–34. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5518.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muruve DA, Pétrilli V, Zaiss AK, et al. The inflammasome recognizes cytosolic microbial and host DNA and triggers an innate immune response. Nature. 2008;452(7183):103–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodman AG, Smith JA, Balachandran O, et al. The cellular protein P58IPK regulates influenza virus mRNA translation and replication through a PKR-mediated mechanism. J Virol. 2007;81(5):2221–30. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02151-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobasa D, Jones SM, Shinya K, et al. Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus. Nature. 2007;445(7125):319–23. doi: 10.1038/nature05495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baskin CR, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Tumpey TM, et al. Early and sustained innate immune response defines pathology and death in nonhuman primates infected by highly pathogenic influenza virus. 2009;106(9):3455–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813234106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diamond DL, Syder AJ, Jacobs JM, et al. Temporal proteome and lipidome profiles reveal hepatitis C virus-associated reprogramming of hepatocellular metabolism and bioenergetics. PLoS Pathog. 2009 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000719. Ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu LF, Liston A. MicroRNA in the immune system, microRNA as an immune system. Immunology. 2009;127(3):291–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(1):57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albrecht M, Sharma CM, Reinhardt R, et al. Deep sequencing-based discovery of the Chlamydia trachomatis transcriptome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1032. Ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perkins TT, Kingsley RA, Fookes MC, et al. A strand-specific RNA-Seq analysis of the transcriptome of the typhoid bacillus Salmonella typhi. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(7):e1000569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armour CD, Castle JC, Chen R, et al. Digital transcriptome profiling using selective hexamer priming for cDNA synthesis. Nat Methods. 2009;6(9):647–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng X, Li Y, Walters KA, et al. Computational identification of hepatitis C virus associated microRNA-mRNA regulatory modules in human livers. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:373. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]