Abstract

Recently, the vacuum-phase molecular polarizability tensor of various molecules has been accurately modeled (Truchon, J.-F. et al, J Chem Theory and Comput 2008, 4, 1480) with an intra-molecular continuum dielectric model. This preliminary study showed that electronic polarization can be accurately modeled when combined with appropriate dielectric constants and atomic radii. In this article, using the parameters developed to reproduce ab initio Quantum molecular polarizabilities, we extend the application of the "electronic polarization from internal continuum" (EPIC) approach to intermolecular interactions. We first derive a dielectric-adapted least-square-fit procedure similar to RESP, called DRESP, to generate atomic partial charges based on a fit to a Quantum ab initio electrostatic potential. We also outline a procedure to adapt any existing charge model to EPIC. The ability of this to reproduce local polarization, as opposed to uniform polarization, is also examined leading to an induced electrostatic potential relative root mean square deviation of 1%, relative to ab initio, when averaged over 37 molecules including aromatics and alkanes. The advantage of using a continuum model as opposed to an atom-centered polarizable potential is illustrated with a symmetrically perturbed atom and benzene. We apply EPIC to a cation-π binding system formed by an atomic cation and benzene and show that the EPIC approach can accurately account for the induction energy. Finally, this article shows that the ab initio electrostatic component in the difficult case of the H-bonded 4-pyridone dimer, a highly polar and polarized interaction, is well reproduced without parameter adjustment.

3.1 Introduction

An intramolecular continuum dielectric model has been recently applied to the calculation of molecular polarizabilities and shown to accurately reproduce those computed using high-level ab intio Quantum Mechanical (QM) calculations1. The electronic polarization from internal continuum (EPIC) approach showed that, relative to other methods, significantly less parameters were required to describe the anisotropy in molecular polarizability which was illustrated by calculations on a set of aromatic, diatomic and alkane molecules. This work focuses on the ability of the parameterized EPIC model to reproduce electrostatic potentials and in particular the response of this potential to external electric fields typical of those responsible for electronic polarization in intermolecular interactions. This is considered an essential feature for force-field based methodologies.

Many researchers have published work on combining a polarizable force-field with Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) formalism mainly to take advantage of the implicit solvent averaging modeled by a solvent dielectric constant. For example, the "Polarizable Force Field" (PFF)2 combines a point induced dipole (PID) model with a continuum solvent. Similarly the "Atomic Multipole Optimized Energetics for Biomolecular Applications" (AMOEBA) force field couples a static multipolar expansion with atomic polarizabilities3 in the context of a PB description of solvent. However, such models are computationally complex requiring atomic tensors to model response effects. In contrast, this work demonstrates that solute polarizability can be modeled using simple dielectric response theory, and requires only a small number of fitted atomic radii and isotropic relative permittivities (dielectrics). Here, however, we focus on explicit interactions, not on solvent reaction fields. Complex electron distributions and response are modeled using atom-centered point charges and a continuum dielectric. A crucial feature of the model is that screening effects produced by intramolecular polarization of the dielectric are explicitly accounted for in calculating atomic charges by least-squares fitting to the electrostatic potential (ESP) computed using ab initio Quantum techniques.

This article describes such a modified RESP4 approach to calculating atomic charges from the ESP. To indicate that dielectric screening is accounted for in the model, the approach is referred to as DRESP. In the rest of this article, we derive the equations relative to DRESP and show the resulting charges on few examples. Additionally, we propose a general way of adapting an existing charge model to behave properly when used with EPIC and we show its performances in reproducing the AM1-BCC5, 6 permanent ESP on selected molecules. The ability of the proposed polarization model to reproduce the response to non-uniform perturbations is also examined. In doing this, we have found that it is not necessary to refit radii and dielectric values optimized based on the vacuum-phase molecular polarizabilities only, thus our previously published parameter sets1 are directly applied. These findings suggest that a general small molecule polarizable model based on continuum electrostatics could be developed. Finally, we apply the EPIC polarizable model to two problems of fundamental importance in biological applications (namely cation-π binding and H-bonding) to demonstrate its performance.

3.2 Methods

Below, a least-squares method, hereafter named DRESP, is derived for fitting atomic point charges to a QM electrostatic potential in the presence of an internal dielectric. The computational details for both the finite difference Poisson’s equation (PE) solver and B3LYP calculations are then presented. Details on the calculation of the induced ESP are also given. Finally, the molecule dataset used to validate the current approaches is described.

3.2.1 A Least-Squares Method

The derivation presented in this section is a generalization of the least-squares method already in use to fit atomic charges to an ESP computed on a grid. Finding the optimal set of atomic charges in the presence of a locally changing dielectric requires a special treatment. For example, Tan and Luo7 designed an iterative optimization scheme. The objective here is to obtain a set of equations linear in the atomic charges that can be easily and quickly solved computationally. The following derivation uses the Poisson’s equation linearity in both the charge density and the potential such that the solution for each individual charge can be superimposed to produce the correct solution for the entire system.

The ESP at a point r of space, φ(r), can be written in an integral formulation with a kernel function G(r,r′) (a Green’s function) that defines the contribution of the local charge density ρ(r′) at a point r of space as shown in (3.1). The discrete nature of point charges allows us to write the charge density as a sum of N Dirac delta functions δ centered at each of the N charge positions ri in (3.2) leading to (3.3):

| (3.1) |

| (3.2) |

| (3.3) |

Now, we define a basis of N atom-source potential Φi (r⃑) functions which describe the potential produced by a unit charge placed at atom i, setting all the other atomic charges to zero. Thus from (3.3):

| (3.4) |

where Φi (r⃑) is a Green function with a single charge that can be obtained, for example, with a finite difference Poisson’s equation solver. The linearity of electrostatic potential (with respect to charge) means (3.1) can be written in terms of the atom source potentials:

| (3.5) |

The goal is to obtain a set of atomic charges that produces an electrostatic potential φ that best approximates that computed from an accurate Quantum calculation ψ. This can be achieved by minimizing the sum of the squares of the residuals between φ and ψ, evaluated at each grid point m. Defining the residual as χ2 we have:

| (3.6) |

Substituting (3.5) into (3.6) gives

| (3.7) |

Using a finite-difference Poisson solver for (3.7), is the atom-source potential evaluated at the fitting grid point m by some interpolation scheme. The values of Qi that minimize the residual χ2 are obtained by setting to zero the N first derivatives of eq 7 against the atomic charges. This leads to:

| (3.8) |

| (3.9) |

To simplify the notation, we define a matrix A̿ and a vector b⃑:

| (3.10) |

| (3.11) |

The linear system of equations to solve becomes

| (3.12) |

If the internal dielectric is set to 1 (vacuum and no polarization) in the computation of atom-source potentials, then the linear equations in (3.12) are those used by RESP4. However by introducing an arbitrary dielectric to model solute polarizability in the calculation of the atom-source potentials, it is possible to account for the contribution of polarization effects in obtaining charges that fit to the Quantum electrostatic potential. In practice, one can solve Poisson’s equation and interpolate the electrostatic potential on the fitting grid for each Green’s function related systems. In general, this procedure requires a solution per point charge. It is also possible to incorporate Lagrangian constraints and regularizing restraints as with RESP4. The introduction of the dielectric effects into the overall procedure is indicated by calling the modified procedure Dielectric RESP (DRESP). In this work, while we choose to not use restraints, we constrained topologically equivalent atoms to have identical charges and applied a constraint to the molecular formal charge. For example, the high symmetry of benzene leads to only one charge degree of freedom whereas in 4-pyridone there are 7 such degrees of freedom. In the remainder of this work, we set the hyperbolic restraints to zero for the all the fit using a dielectric of one (RESP) or higher (DRESP). Normally the RESP hyperbolic restraints reduce the charges to make them more transferable at the expense of reducing the fit quality; for this work restraints were not used. Finally, the general formulation presented here allows to use any kind of dielectric boundary functions (smoothed or not) and multiple dielectric values.

3.2.2 Computational details

Ab initio Quantum electronic calculations were all based on density functional theory (DFT) using the B3LYP8–10 functional as implemented in the Gaussian 0311 software. The molecular geometries were optimized as reported in a previous study1 with a 6–31++G(d,p) basis12. Subsequent ESP and energy calculations were performed using these optimal geometries but with an extended 6–311++G(3df,3pd) basis set. Molecular symmetry was not used as part of the calculations and an accurate convergence criteria was specified for the iterative calculation of the electron density matrix (by using the keyword Scf=Tight, which sets the average density change to be smaller than 10−8 a.u.). Interaction energies reported in this work were all corrected for basis set superposition error (BSSE) using the Boys and Bernardi counterpoise method13, 14.

Finite difference Poisson calculations were done using the program Zap15. A grid spacing of 0.5 Å was used to calculate potentials for both the DRESP charge fitting procedure and in the analysis of induced polarization. A smaller grid spacing of 0.3 Å was needed when solving PE to obtain smooth intermolecular energy curves. The grid boundary was positioned 10 Å away from the closest point on the vdW surface. The convergence grid energy was set to 0.00006 kcal/mol and a Richards vdW surface16 was used to define the molecular dielectric boundary. The molecule inner dielectric and atomic radii were based on the parameterization that reproduced vacuum QM polarizabilities1. The three parameter sets reported previously1 are examined in this work, namely: "P2E" a parameter set which adopts different dielectric values for alkane and aromatic molecules, "P1E" parameter set in which a single dielectric is used to describe the solute response of all molecules, and finally "Bondi" which combines a dielectric of 4 with Bondi radii17 (H radius set to 1.1 Å). The P2E and P1E parameter sets use optimal radii which are systematically smaller than Bondi radii, necessary to accurately reproduce the anisotropy of the molecular polarizability.

In addition to the grid specific to the Zap calculations, a grid was needed to compute the vacuum and the induced ESP. For this purpose, a face-centered cubic (FCC) grid ranging from 1.4 to 2.0 times the atomic Bondi vdW radii was employed5, 6. These distances were determined to lead to an adequate sampling18 of the ESP for atomic charge determination. The FCC grid spacing was set to 0.5 Å.

3.2.3 Induced polarization

To examine the accuracy of the dielectric polarization model, molecules were probed with a +0.5e point charge positioned exterior to the vdW surface of molecules. This probe charge has been used by others19, 20 and was recently shown to be well-adapted to examine the polarizability of aromatics20. In this work, the probe charge positions were determined using a single Conolly surface21 with a vdW distance scaling factor of 2.0 and a density of 0.4 point per Å2. Redundant probe charge positions, by symmetry, were partially eliminated. For example, this resulted in benzene having 6 positions for the perturbing charge, whereas 1,2,4-triazine had 47.

The induced potential is obtained by difference relative to the vacuum potential. Care must be taken to eliminate the contribution of the perturbing point charge to the calculation of the induction potential. This is handled automatically in the Quantum case as a consequence of the coding of Gaussian03. However, when using Zap an extra calculation is required to determine the explicit Coulombic potential arising from the perturbing charge. In total, the induced potential required three PE solutions per molecule on a constant grid. The numerical accuracy was ensured with the low energy convergence criterion.

The difference between QM induction potential (ψ) and that from EPIC model (φ) is characterized as a relative root mean square deviation (RRMSD) as follows:

| (3.13) |

3.2.4 Molecule dataset

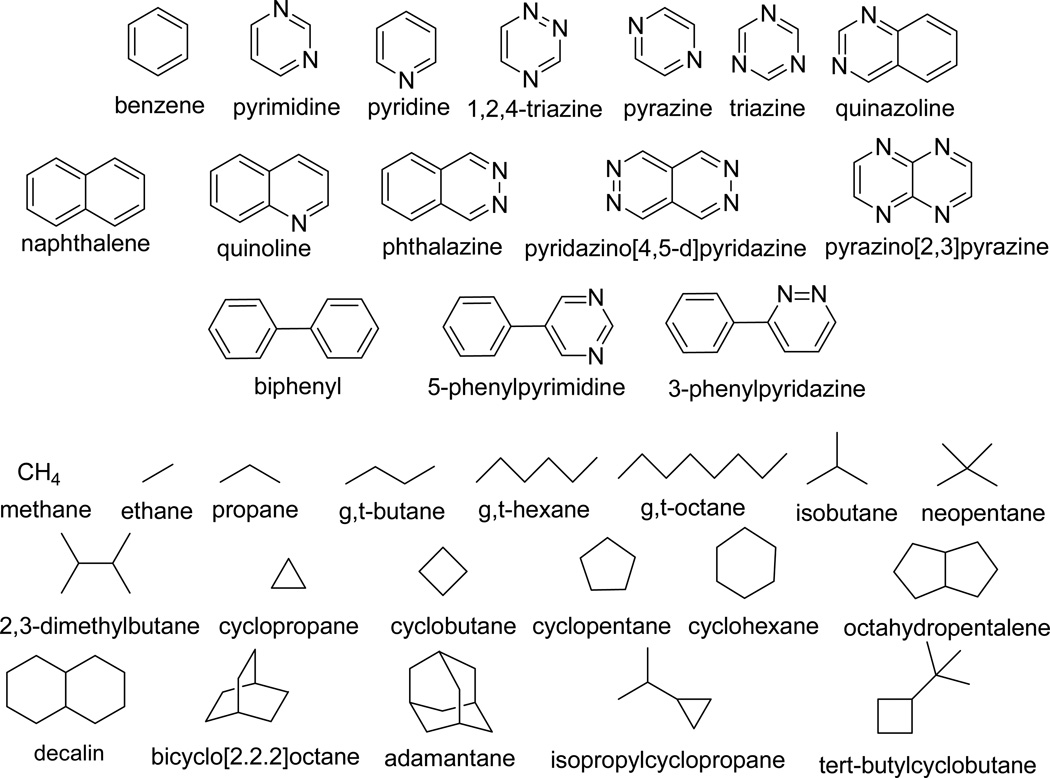

The molecule dataset used in this work contains 15 polar and non-polar aromatics and 22 alkanes as shown in Figure 3.1. In addition, 4-pyridone is used in the study of a H-bond potential. The aromatic molecules exhibit quite a large spectrum of values for the ESP at the surface studied and possess a wide range of polarity. Due to their anisotropy, they constitute a good challenge to polarizable methods. Because of their non-planarity, biphenyl and its analogs have a different shape of the potential and a different conjugation of the π electron system compared to the other aryl molecules. Finally, the alkanes are quite polarizable in spite of their low polarity and the molecules used exercise many kind of shapes. All the molecule structures in this dataset are from the previous study1.

Figure 3.1.

Molecule dataset which contains aryls and alkanes chemical classes. These 15 aromatic and 21 alkane molecules are extracted from reference1. We use the notation 't' to indicate the all-trans conformation and 'g' when one or more gauche dihedrals are present; these are separate entries.

3.3 Results and discussion

In this section, the ability of the proposed least-squares fitting method, DRESP, to produce an accurate permanent electrostatic potential is first examined and compared to the usual least-squares fitting RESP approach. We then continue by proposing a general way of coupling an existing charge model to EPIC, illustrated with the AM1-BCC charge model, which is general and shows many advantages in condensed phase simulations5, 6, 22, 23. The ability of the EPIC approach to produce an accurate induced ESP in the presence of a locally varying electric field is also examined. Finally, the polarizable and permanent features of EPIC are used to study the electrostatic energy profiles in two challenging cases: cation-π and 4-pyridone H-bonded dimers.

3.3.1 DRESP VS RESP

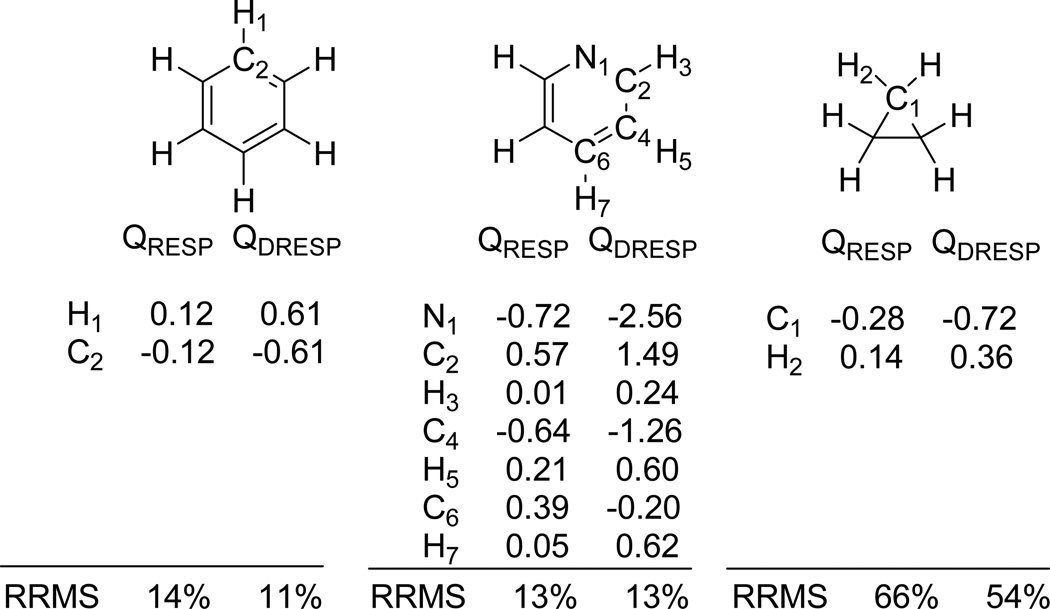

Given the way EPIC incorporates electronic polarization, the usual strategy to fit atomic partial charges to reproduce the QM ab initio ESP must be modified. This is due to the presence of a dielectric continuum inside the molecular electronic volume that screens the effects of a charge even at long distances. The DRESP approach, outlined in the Method section, solves this issue and provides a set of linear equations that give the optimal set of charges, in the least-squares sense, that reproduce the QM ab initio ESP. We first apply DRESP with the P2E parameters and compare the RRMSD made on the permanent ESP of B3LYP for the molecules of Figure 3.1. The atomic partial charges are also fitted to the same vacuum QM ESP using RESP. The DRESP charges are significantly larger than those obtained with RESP. This is illustrated in Figure 3.2 for benzene, pyridine and cyclopropane: the C/H charges of benzene are found to be ±0.12e as calculated with RESP and ±0.61 with the dielectric P2E model calculated with DRESP, the charges on pyrimidine are also significantly smaller with RESP than with DRESP and similarly for the cyclopropane. Although large and chemically counter-intuitive charges are needed when Poisson’s equation is used, they produce the same ESP as the regular coulombic approach. Figure 3.2 also reports comparable RRMSD deviations between DRESP and RESP for benzene, pyridine and cyclopropane. The RRMSD reported on cyclopropane is high, but it is known that for simple alkanes the atomic partial charge approximation is poor24, 25 However, since the actual ESP for the alkanes is very small, this defect might be negligible in intermolecular interactions although the alkane polarizability is not. Finally, it is important to keep in mind that whenever a radius or an inner dielectric value change, the DRESP charges cannot be transferred but must be re-optimized against the same QM ab initio ESP grid.

Figure 3.2.

Benzene, pyridine and cyclopropane optimal charges fitting equally the same electrostatic potential with a dielectric of one (RESP, non-polarizable) and the P2E model (DRESP). The significantly higher charges with the P2E model comes from the internal dielectric screening of the point charges.

3.3.2 Use of an existing charge model: the AM1-BCC/DRESP example

AM1-BCC from Jakalian et al.5, 6 is an accurate charge model applicable to all small organic molecules and based on the over-polarized HF/6–31* ESP known to produce good charges adapted to polar media such as water. AM1-BCC was shown to be better or equal to much more computationally expensive methods in matching experimental free energy of solvations of small molecules22, 26. A significant advantage of AM1-BCC is that the atomic point charges are obtained by adjusting with pre-fitted bond-charge corrections the AM1 electronic population analysis charges. Because the bond-charge corrections published by Jakalian et al. are adapted to produce polar media charges, a gas-phase AM1-BCC model is needed for use with a polarizable electrostatic model. In this work, we demonstrate proof-of-concept for the coupling of a general AM1-BCC/vacuum model, fitted to vacuum B3LYP/cc-pVTZ ESP27, to the dielectric polarizable model. The approach taken here uses the AM1-BCC/vacuum charges to calculate the ESP on a fitting FCC grid, detailed in the Methods section, to which dielectric adapted charges are fitted using the DRESP method. We call this fitting strategy AM1-BCC/DRESP. Although we apply this strategy to the AM1-BCC/vacuum charging scheme, it is general in the sense that any other charge model could be adapted the same way.

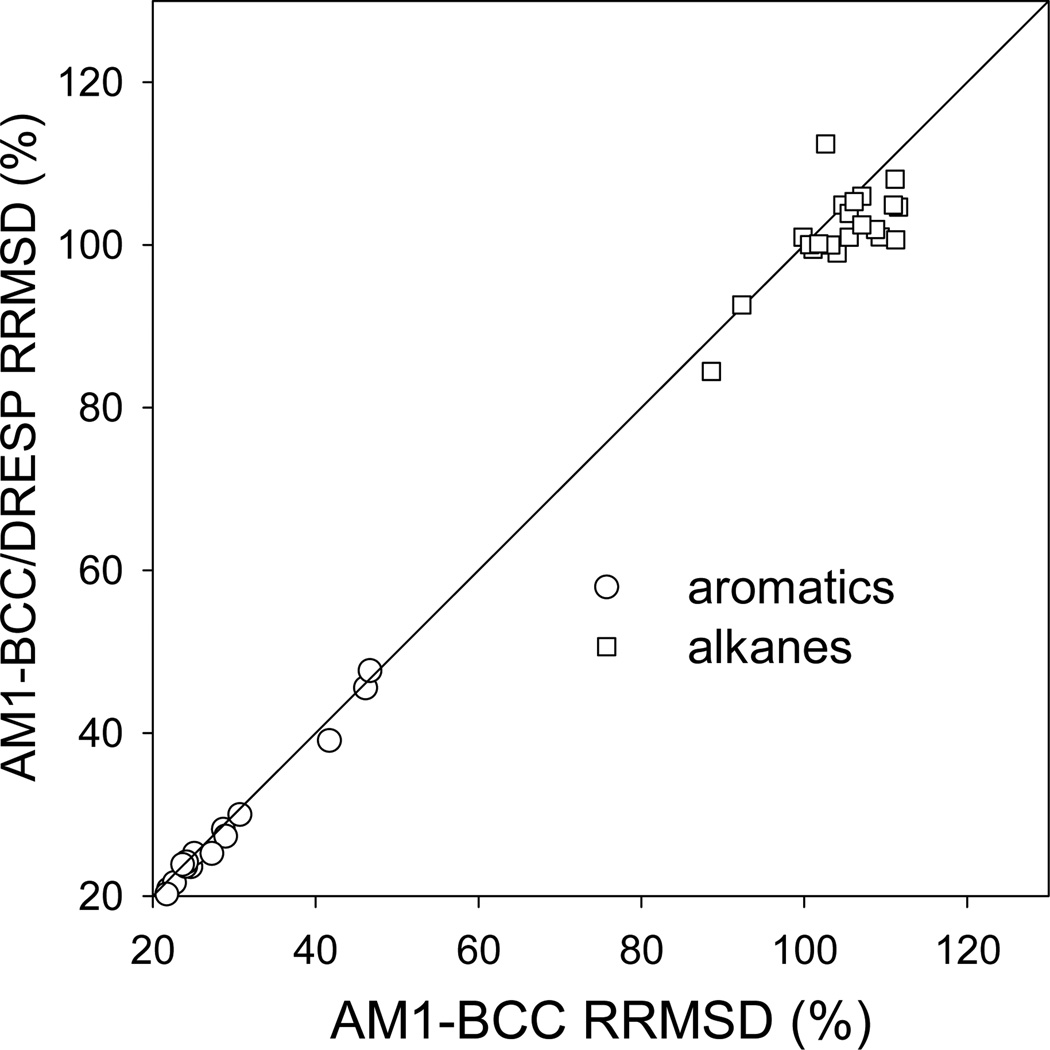

In Figure 3.3, we compare the B3LYP/6–311++G(3df,3pd) ESP to both the AM1-BCC/vacuum and the AM1-BCC/DRESP ESP. The correlation between the two RRMSD is excellent for aromatics and the AM1-BCC/DRESP charges produce slightly smaller RRMSD for the alkanes, which we think is not significant given the low level of accuracy for this chemical class. This demonstrates that extending an existing charge model, developed in a non-polarizable context, is easy and accurate. More importantly, the parameterization of the polarizable parameters and of the permanent charges can be fully decoupled, hence greatly reducing the fitting complexity.

Figure 3.3.

Correlation plot of the RRMSD obtained with AM1-BCC and AM1-BCC/DRESP charging schemes. The RRMSD are calculated against the B3LYP permanent electrostatic potential on the FCC grid.

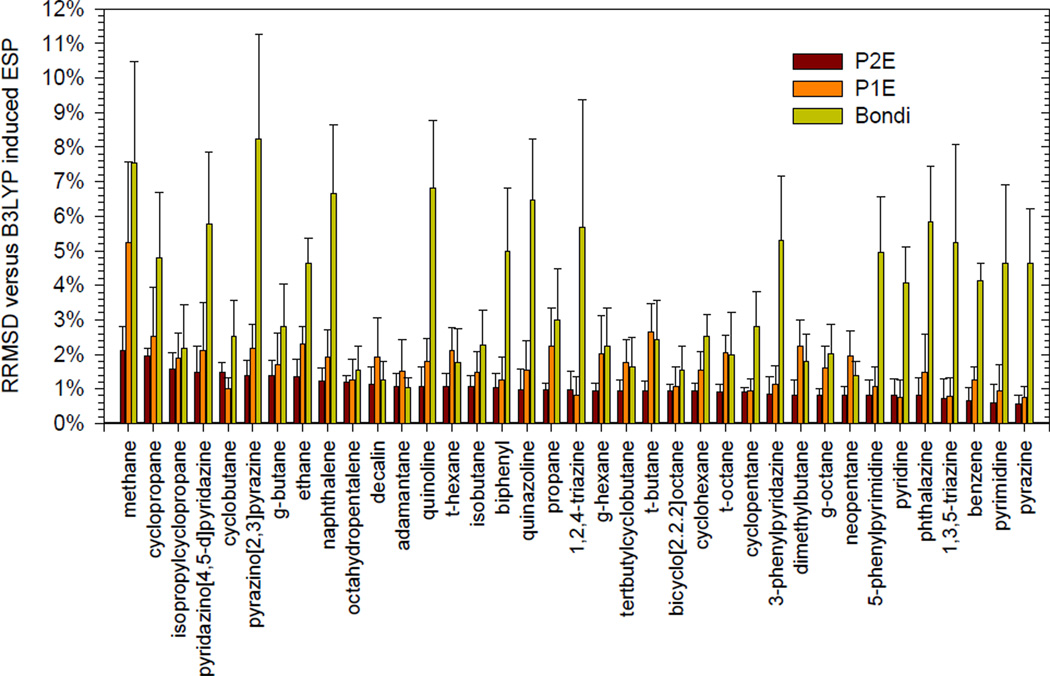

3.3.3 Induced electrostatic potential

Previously, EPIC was shown to reproduce accurate induced dipole moments on molecules submitted to a uniform electric field1. Here we assess the ability of the approach to account for more local perturbations. This is accomplished by examining each of the 37 molecules from Figure 1 for which the electrostatic potential induced by a single probe charge of +0.5e is calculated with both B3LYP and EPIC according to the prescription detailed in the Methods section. Given the numerous placements of the probe charge for each molecule, the RRMSD deviations between B3LYP and EPIC are averaged and reported in Figure 3.4. This includes around 1700 B3LYP single point calculations in total. The RRMSD standard deviation (STDEV) indicates how much the error varies as a function of the position of the probe charge. The three bars per molecule correspond to the results obtained using three different parameter sets from the previous study1. The average RRMSD obtained with P2E (c.f. Method section) were used to sort the molecules in Figure 3.1. This method led to an average RRMSD and STDEV across the molecules of 1.06% and 0.3% respectively; the maximum average RRMSD is attributed to methane with 2.1%. The results obtained with the P1E parameter set (see Method) are slightly worse with an average RRMSD across the molecules of 1.70% and a STDEV of 0.8%. In the case of the Bondi parameter set (see Method), the average RRMSD and STDEV are 3.74% and 2.0%, almost a factor of four higher than P2E. The errors reported with Bondi parameters show a bias toward a more accurate description of the alkane polarizabilities.

Figure 3.4.

Average RRMSD on the induced ESP maps as calculated with EPIC using three parameter sets (P2E, P1E and Bondi, see the text). The ESP maps are generated by a +0.5e located at non-redundant positions and the reference induced ESP is calculated from B3LYP 6–311++G(3df,3dp).

To examine the effect of induction by the +0.5e charge on the alkanes, non-polar aromatics, and polar aromatics, it is of interest to compare the grid unsigned average of the induced and vacuum ESPs for each class. In the case of the alkanes, the unsigned average of the induced ESP is about 3 times higher than the vacuum ESP evaluated on the fitting grid. Benzene and non-polar aromatics have comparable induced and static ESP positive magnitudes and, in the case of polar aromatics such as pyrimidine, the induced ESP is between twofold and threefold smaller than the vacuum ESP. This indicates that the level of electronic polarization is significant and appropriately challenging to the polarizable model. The RRMSD obtained with the induced ESP is much lower than the RRMSD of the static ESP fit by atomic charges. This shows that the model can accurately account for locally induced polarization although the induced ESP is certainly simpler than the ESP originating from the unperturbed molecule.

Here, we use the induced ESP to test the ability of the EPIC model, parameterized solely on the QM gas phase polarizability tensor, in reproducing a molecule’s induced QM electronic response to a polarizing charge. The very small RRMSD obtained with the P2E and the P1E parameter sets indicate that the local polarization with a non-uniform electric field is as accurately modeled as the induced dipole moment due to a uniform electric field1 (molecular polarizability), the basis of the P2E and P1E parameterization. In contrast, most previous polarizable models28–30 obtain their polarizability parameters (and often simultaneously the charges) by fitting to the induced ESP on polarized molecules.

3.3.4 Induction by a symmetric field

The parameterization of polarizable models usually involves simple fields such as uniform external electric fields or fields produced by a probe point charge or a probe dipole. These external fields induce mainly a molecular dipole moment, which should be reasonably well accommodated given a simple functional form for a polarizable model. However, in condensed media, the electric field is rarely simple and is often transiently symmetric around a molecule. In this section we compare the induced electrostatic potential in a non-trivial electric field applied on an argon atom and benzene; three methods are examined: point inducible dipoles, EPIC and B3LYP.

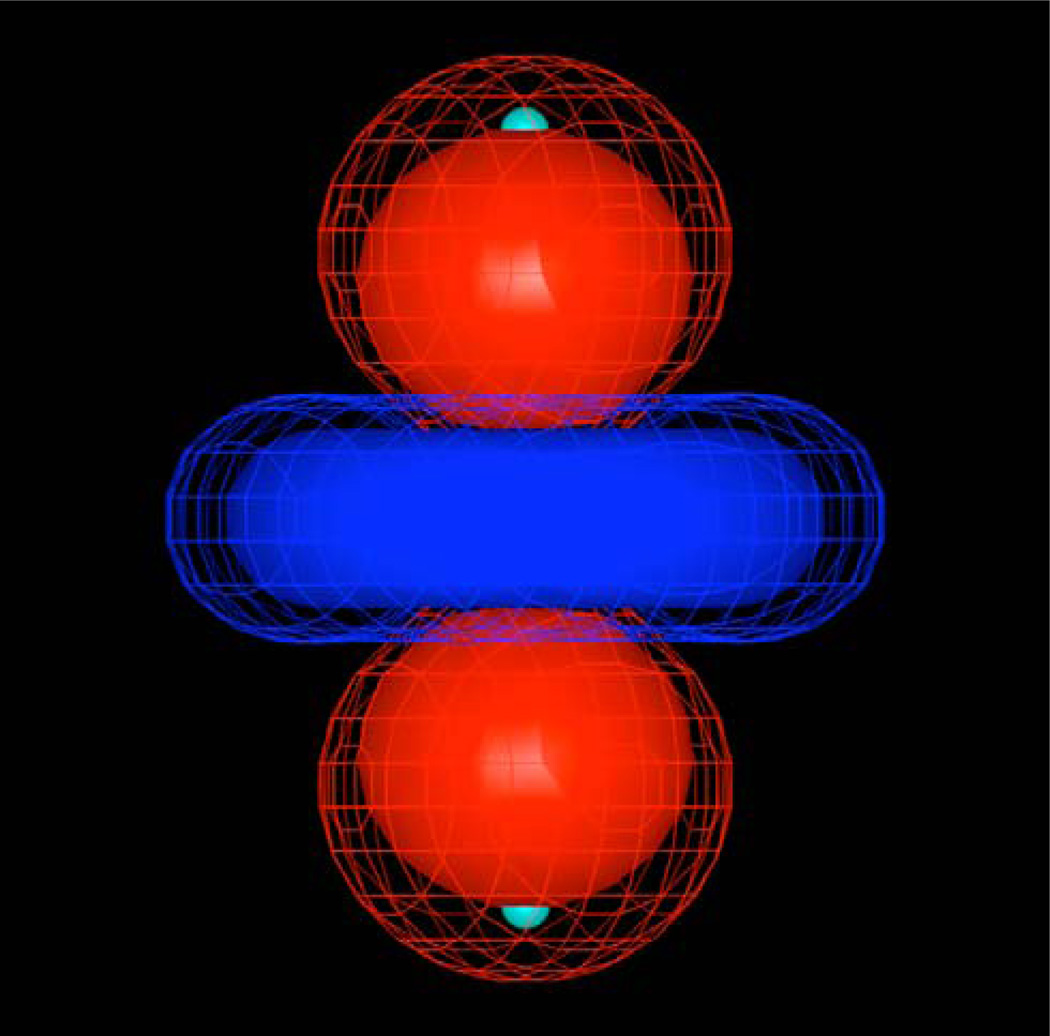

In the first system, the argon atom is sandwiched between two point charges positioned at 3.0 Å above and below the atom. The EPIC argon radius used is set to 1.31 Å and the dielectric=7.36 as fit to reproduce the (gas-phase) B3LYP atomic polarizability of argon (11.1 a.u.). Given the symmetry of this system, the net electric field at the argon nucleus is zero. Since the point inducible dipole1 and the fluctuating charges31 polarizable models respond only to the net electric field at the nucleus, neither of these models would show induction in this case. As illustrated on Figure 3.5, the B3LYP induced electrostatic potential is a quadrupole with the dz2 hydrogenoid-like orbital symmetry. Remarkably, the EPIC induced electrostatic potential has the same symmetry and is of similar magnitude.

Figure 3.5.

The induced electrostatic potential of an argon atom sandwiched in between two +0.5e charges positioned at 3.0 Å of the nucleus. The solid iso-surface corresponds to the B3LYP/6–311++G(3df,3pd) and the mesh iso-surface to the result from EPIC (radius=1.3 Å, dielectric=7.4). The induced moment is an induced quadrupole with the dz2 orbital symmetry. The traditional atomic polarizable approaches have a zero induced electrostatic potential.

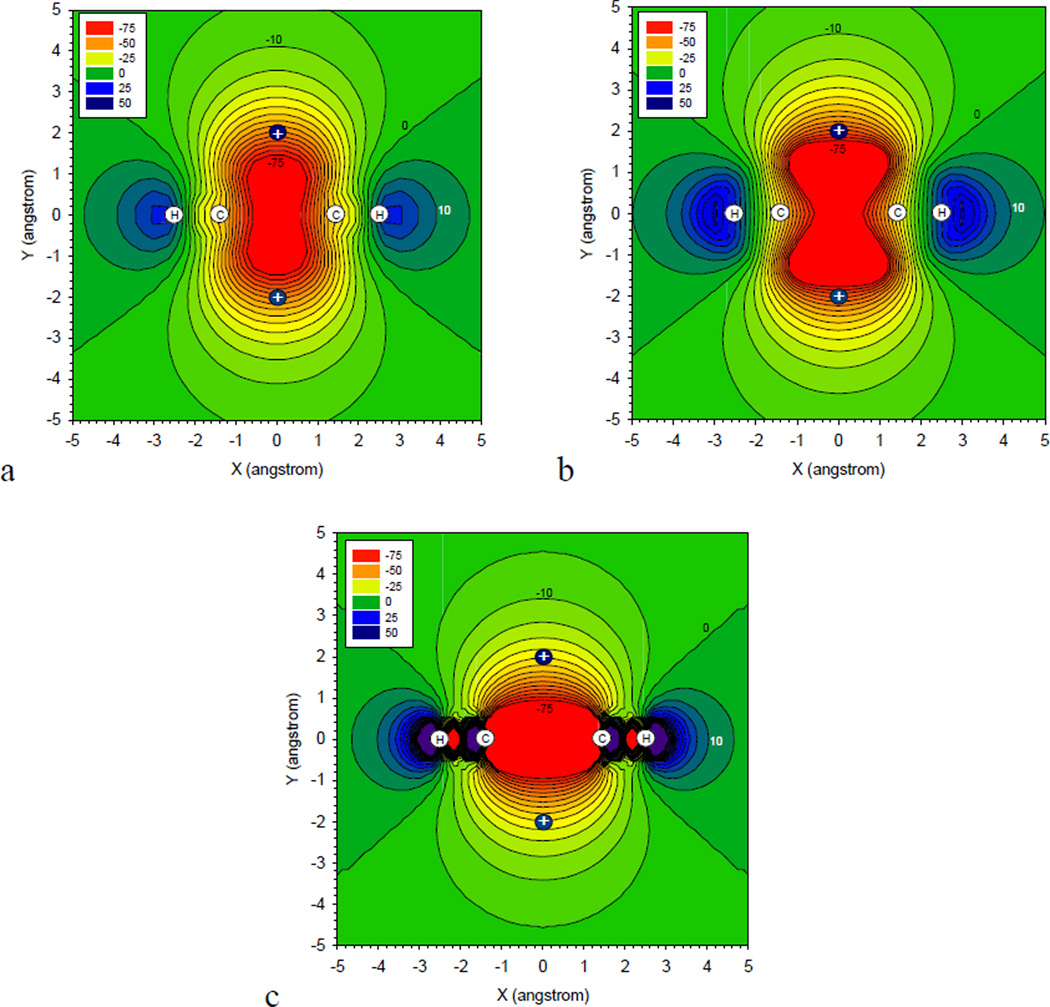

The second system examined consists of benzene sandwiched by two +1e point charges located at 2Å above and below the ring. This is a fairly large perturbation where the point charges are positioned approximately at the Li+/benzene equilibrium distance. Although in nature it is unlikely that two Li+ atoms would be stable in such a sandwich system, the perturbing electric field varies quickly from zero at the center of the benzene ring to 2/r at infinity. So within the volume of the benzene, the field varies enough to significantly test the model. The symmetry of this arrangement is such that the external electric field has only a component in the plane of the ring at the atomic positions, although the out-of-plane polarization should be predominant. A similar system was used to show the failure of the fluctuating point charges model by Stern et al.31. In principle the point inducible and related polarizability models should also have difficulty since the magnitude of the induced potential would then be fully dictated by the in-plane polarizability component. For our comparison, we used the AMOEBA polarizability model for benzene which includes a Thole exponential damping parameter of 0.39 coupled with carbon and hydrogen isotropic polarizabilities of 1.334 Å3 and 0.8 Å3 respectively (as provided in TINKER 4.2 distribution parameter file). The Thole parameter has the role of adjusting the molecular polarizability anisotropy by reducing the atomic induced-dipole/induced-dipole interactions thereby avoiding the polarizability catastrophe, inherent to the PID models. Calculated with these parameters, the benzene vacuum molecular polarizabilities are 11.4Å3 in the plane and 6.2Å3 perpendicular to the plane, which are in close agreement with the values of 12.2Å3 and 6.7Å3 obtained with B3LYP/aug-cc-pVTZ. For this comparison, we use EPIC with the P2E parameters which also produces accurate polarizabilities of 12.2Å3 and 6.6 Å3.

For the charge-sandwiched system, the iso-contour lines of the induced electrostatic potential on one of the six planes of symmetry perpendicular to the ring are plotted in Figure 3.6. The iso-lines are spaced by 5 kcal/mol/e and the ESP values are given in kcal/mol/e. For the three methods, the induced ESP has the shape and symmetry of a dz2 orbital, a quadrupole moment, with the negative lobes oriented along the axis joining the two probe charges and the positive torus located close to the hydrogen atoms. Good agreement is obtained between the induced ESP of B3LYP and EPIC even intra-molecularly. At the probe charge positions, the B3LYP, EPIC and AMOEBA induced potentials are −52, −60 and −29 kcal/mol/e respectively. In general the point inducible dipole potential is too positive moving away from the benzene along the probe charge axis. The relatively large difference between B3LYP and AMOEBA, compared with the smaller error made with EPIC, cannot solely be explained by the smaller in-plane benzene polarizability of AMOEBA because the AMOEBA positive ESP regions, particularly at vdW distances from the H atoms (2Å away), match the B3LYP values. We attribute the better success of the dielectric-based EPIC model by its departure from the atom centric-polarization to an electron-centric model where the entire molecular boundary responds to the electric field. In order to improve the PID model while retaining the correct average molecular polarizability and anisotropy of benzene, auxiliary polarizable points above and below the ring would have to be added, at the expense of additional complexity and supplemental parameterization. This being said, condensed phase simulations have lead to parameterizations of polarizable PID-based force fields that accounted for important liquid properties of benzene32 although a polarizable electrostatic term is often not necessary to fit the liquid properties. We believe that the accurate polarizable electrostatic term should make a more important difference in heterogeneous and anisotropic environment such as the active site of an enzyme or a trans-membrane ionic channel. It is encouraging that the EPIC model with default P2E parameters exhibits good physical behaviors at the purely electrostatic level even in the context of strong and complex electric fields.

Figure 3.6.

The induced electrostatic potential for benzene is shown by iso-contour lines spaced by 5kcal/mol/e on one of the six symmetry plan perpendicular to the ring. The external perturbing potential is produced by two +1e charges positioned 2Å above and below the benzene ring. The induced potential obtained at the B3LYP/6–311++G(3df,3pd) level (a) is compared to the EPIC/P2E (b) and AMOEBA, a good quality QM derived point-inducible model (c).

3.3.5 Cation-π interactions

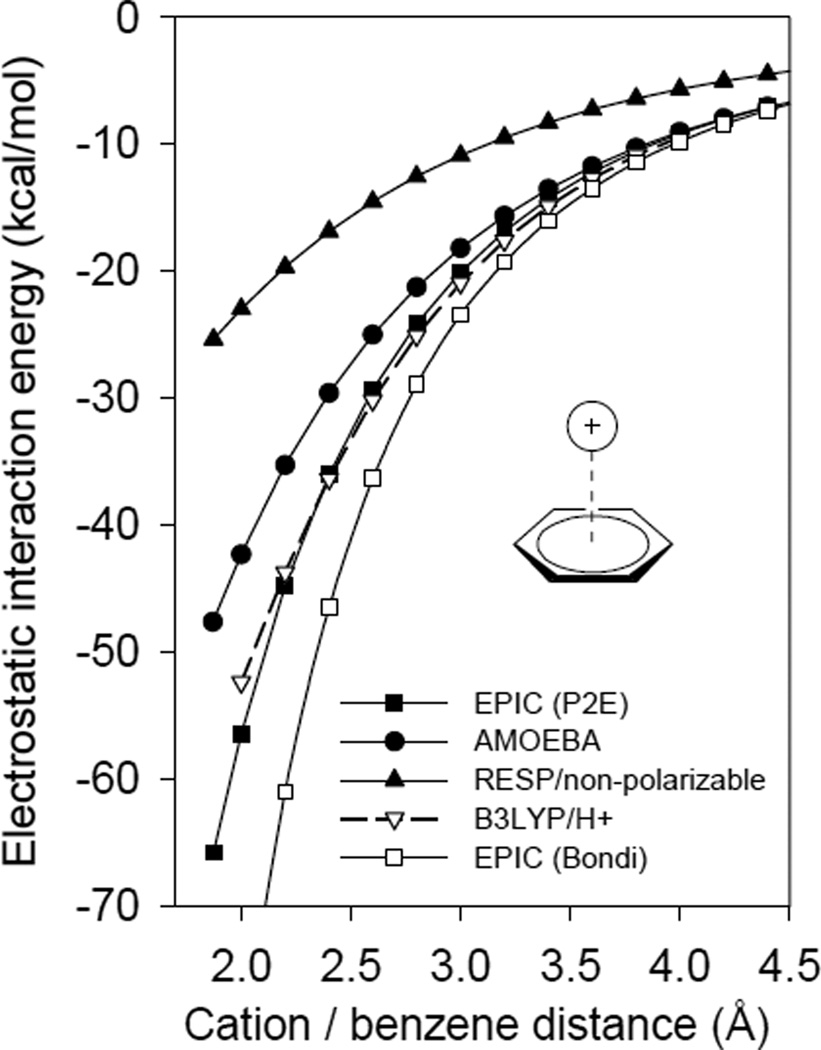

In the previous sections, we have separately demonstrated that EPIC can handle both the permanent and induced electrostatic potential strictly by comparison to the induced B3LYP electrostatic potentials. Now, we combine the DRESP fitting procedure and the EPIC model to assess the electrostatic interaction energy in cation-π systems. The cation-π attractive interaction energy between benzene and Li+, Na+ or K+, displaced along the benzene six-fold symmetry axis, was shown to be impossible to describe with nonadditive models33. However, the contribution of the induction energy (from electrostatic polarization) is crucial for an accurate description of cation-π binding33, 4. Furthermore, the presence of cation-π interactions in many biological systems35–37 makes this application a critical validation for a new polarizable electrostatic term. Therefore, in this section we decompose the total interaction energies and check if the induction found with the P2E parameter set is quantitatively correct.

At the QM level, the total interaction energy between an atomic cation and benzene can be conceptually split into electrostatic, vdW repulsive, and vdW attractive components. Each term is normally represented separately in a force field, although one term often compensates for another containing deficiencies. We are now only interested in examining the electrostatic component and we focus on the proton since the its vdW interaction with the benzene can be neglected. Other cations have similar electrostatic profiles outside their vdW range (data not shown). At the force field level, if the proton/enzene interaction energy is described correctly, all that remains to be added is the repulsive vdW term in order to model other, more physiologically relevant, atomic cation-π interactions. This will be shown in the next section in a different application.

The energy of interaction between a benzene molecule and H+ is calculated at the B3LYP/6–311++G(3df,3pd) level with no basis function positioned on the proton to avoid unphysical stabilization. Figure 3.7 reports the energies as a function of the distance from the center of the benzene ring using B3LYP, a non-polarizable Coulomb potential calculated with RESP-fitted atomic charges, the electrostatic component of the polarizable AMOEBA force field, and our polarizable EPIC/P2E model. For the non-polarizable and AMOEBA models, the parameters mentioned in section 3.4 are used. Figure 3.7 shows that EPIC matches quantitatively the B3LYP energy profile. As found previously33, the non-polarizable potential is inappropriate for describing cation-π interactions, despite the fact that the atomic partial charges of benzene were fitted on the same ESP grid as were the EPIC/DRESP charges. The energy resulting from electronic polarization dominates the electrostatic interaction energy, being twice more stabilizing than the static contribution at typical intermolecular separations – this induction energy remains substantial for intermolecular separations as large as 4Å. The AMOEBA description of the electrostatic energy captures most of the induction energy. This model, like EPIC, is derived from ab initio calculations, but includes atom-based multipole expansion terms up to the quadrupole for the permanent potential. In addition, AMOEBA adds an atomic polarizability on the hydrogen atoms. The difference between B3LYP and AMOEBA energies can be explained, in part, by AMOEBA's slightly smaller out-of-the-plane polarizability (c.f. section 3.4). Tsuzuki et al.34 have shown that it is possible to get the cation-π system correctly modeled with a PID model if it is parameterized in a specialized manner. In their work they not only use atomic multipoles, but also anisotropic atomic polarizability located on the carbon atoms. Once more, we see that the EPIC model with P2E parameters is robust and general, needing only a small number of default parameters to account for the different aspects of electronic polarization. The accuracy of this model implies that the vdW term will not need to compensate for errors in the close-range electrostatics thus easing its parameterization.

Figure 3.7.

The electrostatic interaction energy between a benzene molecule and H+ displaced along the C6 symmetry axis corresponds to the electrostatic component of a cation-π system formed with an atomic cation. The non-polarizable model using ESP derived charges is far from the B3LYP calculated energy, the EPIC/P2E model closely follows the B3LYP curve and AMOEBA captures most of the electronic polarization of B3LYP. The EPIC electrostatics fitted on B3LYP monomer reproduces the correct cation-π electrostatic energy without adjustment.

3.3.6 H-bond of the pyridine-4(1H)-one dimer

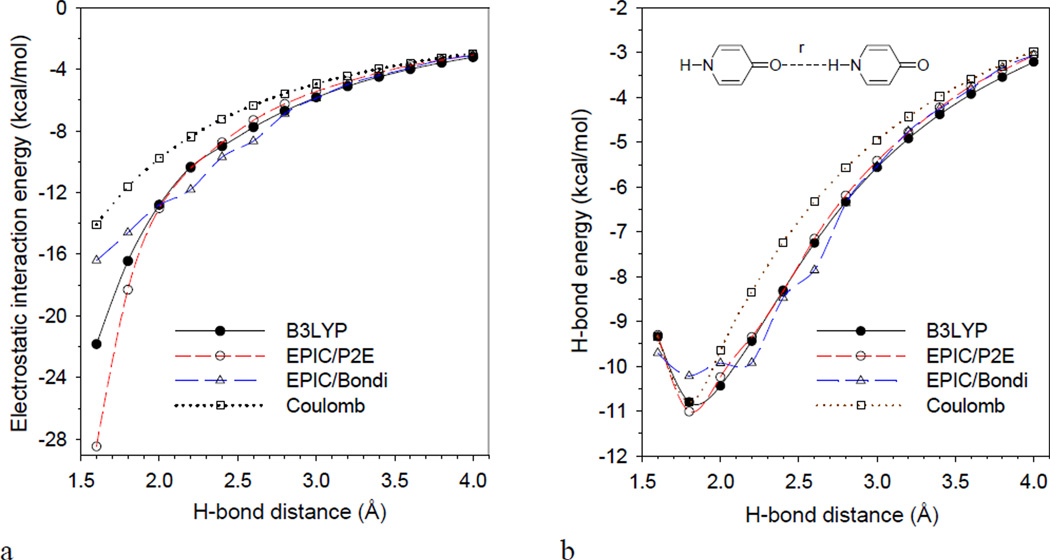

The induction energy in H-bonds is implicitly included in existing additive force fields. The single-minimum interaction energy profile representing an H-bond becomes a trade-off between the attractive electrostatic term and the short-range repulsive vdW term of a force field. For example, in the original AMBER force field a special 12-10 Lennard-Jones potential was initially needed to describe short range H-bonding potentials38. In more recently developed non-polarizable force fields39, both the condensed phase overpolarized HF/6–31G(d) charges and the addition of hydrogen atom types using small Lennard-Jones radius (σ) parameters corrected for the lack of induction energy. Including explicitly induction energies should, in principle, simplify the parameterization of vdW potential and incorporate non-additive condensed phase effects such as H-bond cooperativity40, 41. In this section, we examine the challenging case of pyridin-4(1H)-one, hereafter 4-pyridone, which was shown to form strong intermolecular H-bonds42 when monomers are co-planar and aligned along the two-fold axis passing through the NH and the CO bonds. This is in part due to the large dipole moment of 7 Debye and the high polarizability component of 97 a.u. both oriented along the H-bond axis that should polarize the monomers and thereby constitute an interesting second application for the validation of polarization using EPIC This is a case where polarizability needs to be taken into account even at the dimer level. In what follows, we conduct two different studies which objectives are a) to assess if the EPIC model with DRESP charges gives the correct electrostatic interaction energy profile compared to B3LYP and b) to reproduce the dimer H-bond dissociation energy curve obtained by B3LYP.

3.3.6.1 4-pyridone dimer electrostatic interaction energy

Unlike the previous cation-π application, evaluating the performance of our electrostatic approach here involves partitioning the total electronic structure energy into its components because the vdW term cannot be neglected. We will divide the total energy into an electrostatic (ΔEelec) term and an exchange-repulsion (hereafter called the vdW repulsion and noted ΔEvdw) term. The short range attractive dispersion energy is omitted because B3LYP does not capture it and it remains very small compared to the range of energies involved.

Given this partitioning, we calculate ΔEelec by substracting ΔEvdw from the total interaction energy (ΔEtot). The delta symbol in front of the energy signifies that this is an interaction energy, meaning the difference in energy between the interacting system and the energies of the monomers. To approximate the ΔEvdwDFT term, we used benzo-1,4-quinone (quinone) and benzene which both have a relatively small ESP. The benzene hydrogen replaces the 4-pyridone H donor and the quinone oxygen the acceptor, forming a quasi H-bond. The assumption here is that the vdW repulsive term is similar between the two systems. The monomer geometries are held fixed and the carbonyl oxygen to benzene H distances are the same as the 4-pyridone H-bonded dimer distances. The ESP of both molecules is relatively small and can be approximated using RESP-derived atomic point charges (ΔEelecRESP); thus ΔEelec is calculated using equations 14 and 15:

| (3.14) |

| (3.15) |

Figure 3.8a shows ΔEelecDFT, ΔEelecRESP and ΔEelecDRESP associated with the 4-pyridone dimer for distances going from 1.6Å to 4Å. The the equilibrium distance is found at 1.78 Å42; details of the energies are reported in the Supplemental Material. As reported in Figure 3.8a, the induction energy stabilization obtained with EPIC/P2E matches B3LYP over most of the distances. The deviations at close contact (<2 Å) may be attributable to defects in the approximation given by eq. 14. Comparing the Coulomb and B3LYP curves at the equilibrium distance, the induction energy is almost −5 kcal/mol, a significant increase over the Coulomb value of −11.6 kcal/mol. The quantitative match between the approximated B3LYP electrostatic H-bond energy shows that the induction interaction is appropriately described by our polarizable EPIC/P2E. It is important to emphasize that the radii and dielectric parameters (P2E) used were not fitted to any energy but to the QM gasphase molecular polarizability tensors for many molecules simultaneously1. In Figure 3.8a, we can also see the EPIC/Bondi interaction curve that uses DRESP derived charges and the Bondi parameter set (c.f. Method). The long range interaction energies are appropriate but when the electronic volumes, defined by the Bondi radii (1.52 Å for oxygen and 1.1 Å for the hydrogen), start to interpenetrate, the induction energy becomes insufficient and undergoes numerical instability that we attribute to the vdW surface used in the finite difference PB solver, known to form cusps.

Figure 3.8.

The reported electrostatic interaction energies of the H-bonded 4-pyridone dimer (a) show that the EPIC/P2E model produces the appropriate polarization as opposed to the non-polarizable permanent charge model (Coulomb) when compared to B3LYP (3.15). The EPIC/Bondi calculations produce the correct electronic response at long ranges of H-bond distances but saturates as the vdW dielectric surfaces of the monomers start overlapping. The observed deviations are a result of the numerical instability that occur when the dielectric spheres come into contact at 2.6 Å. (b) The BSSE/corrected B3LYP interaction energies of the dimer unveils a very strong H-bond of −10.8 kcal/mol at the minimum located at 1.78 Å. The reported classical approaches combined the electrostatic energies (shown in a) and a fitted repulsive vdW term. EPIC/P2E matches the B3LYP energies over the examined range whereas the Coulomb non-polarizable model deviates at longer distances as a result of the difficulty for such a model to match both regions.

3.3.6.2 4-pyridone dimer dissociation energy

To get an idea of how well EPIC polarization could be incorporated into an atomic force field, a vdW term was fitted to see how well the QM energy profile could be reproduced; the details of the fitted vdW terms are given in the Supplementary Material. The resulting complete interaction energy profiles for the H-bond formation of the 4-pyridone dimer, ΔEtot(4-pyridone,4-pyridone), are presented in Figure 3.8b. For the DFT profile (ΔEtotDFT), the approximation of (3.15) is not needed because only the total energy is examined. The B3LYP/6–311++G(3df,3pd) BSSE corrected energies show a very stable H-bond with a dissociation energy of-10.8 kcal/mol..

A few comments on the vdW fitting process are in order. In keeping with high-level QM calculation of exchange-repulsion energies,43 we have used a two-parameter exponential vdW energy function ΔEvdwEPIC(r) fitted to the residuals ΔEtotDFT(r) -ΔEelecEPIC(r) calculated along the intermolecular H-bond axis. Fortunately, the vdW dispersion energy, an attractive force, is absent in DFT methods and should not be needed here. The fit of the EPIC/P2E residuals resulted in a dissociation energy curve quantitatively reproducing the B3LYP energies in all ranges examined, giving a correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.999.

Note that the atomic partial charges derive from a DRESP fit to the monomer only. In contrast, the Coulomb model residuals (using atomic partial charges from the gas-phase monomer without polarizability) could not be fit to an exponential as successfully, exhibiting an attractive potential well of about −1 kcal/mol located at 2.3 Å. This example shows that, at the level of the dimer, the lack of polarizability introduces a requirement for a more complex functional form for the vdW term in order to compensate. Finally, the EPIC/Bondi potential has difficulty capturing the energy minimum and exhibits numerical instability. At very short H-bond distances (<1.5 Å), EPIC/P2E also exhibits similar instability behavior, but fortunately this is less relevant given that the high repulsive vdW energy is dominant. This is due to the smaller dielectric radii assigned to the oxygen and hydrogen atoms in the fit. The use of a smooth dielectric boundary could significantly reduce these effects15.

While these applications demonstrate the use of EPIC to incorporate electronic polarization into short-range intermolecular interactions, the generalization of this model for use in the condensed phase will require special attention in the parameterization. Indeed, it has been proposed based on various evidences that the condensed phase molecular polarizability per monomer is smaller than its gas phase polarizability. In practice, the correction to a PID model was made by fitting the polarizabilities on ab initio values obtained with a relatively small basis set, which systematically produces smaller molecular polarizabilities43. Hence for the PID model, the parameterized polarizability cannot accurately account for both the gas- and condensed-phase polarization, one of the main objectives for a polarizable force field. We are currently examining this problem with EPIC and this will be addressed in a subsequent publication.

3.4 Conclusion

This work extends the proof-of-concept of the EPIC (electronic polarization from intramolecular continuum) approach to intermolecular interactions1. We show that in general the presence of an intramolecular continuum dielectric, for example in PB or PE formalisms, requires a modification of the conventional method for obtaining accurate atomic partial charges. We derive a least-squares approach called DRESP, by analogy to RESP, which not only reproduces the ab initio electrostatic potential but also offers a way to transfer the atomic partial charges from an existing vacuum charge model. We demonstrate this by successfully transferring the charges from an AM1-BCC/vacuum charging scheme of a set of 37 molecules including polar and non-polar aromatics and alkanes. In general, the charges obtained are significantly larger whenever the dielectric inside the molecule is larger than one. Even more importantly, our results show that the polarizable parameters of EPIC can be derived independently from the permanent electrostatic terms. In fact, the atomic radii and dielectrics fitted to vacuum ab initio molecular polarizabilities were derived in the absence of atomic partial charges. We believe that this parameter decoupling will be an important asset to broaden the approach to encompass bio-organic chemistry.

Although EPIC was successfully fitted previously to reproduce ab initio dipole moments induced by a uniform electric field1, it was important to demonstrate that the full electrostatic potential induced by a more local or complex perturbation would be as accurate. To this end, we tested the validity of our parameters with a perturbing +0.5e probe charge moved on a Connolly surface. This is frequently employed to fit the polarizable parameters in force fields. The results were very encouraging leading to an average of 1% RRMSD deviation, relative to B3LYP, obtained from about 1700 calculations done on our set of 37 molecules. This shows that we can fit the EPIC radii and dielectrics on gas-phase molecular polarizabilities and expect an accurate local electronic polarization response as well.

A potential advantage of EPIC over other polarizable models is its use of 'electronic polarizability density' through the intramolecular continuum dielectric. As opposed to PID models, the electric field induction is effective through the entire molecular volume. A recent study by Schropp and Tavan44 suggests that the usual approximation that the polarizability is centered on atomic nuclei artificially invalidates the use of gas-phase derived atomic polarizabilities into condensed phase simulations unless non-obvious and non-general corrections are applied. To further examine the ability of EPIC to deal with inhomogeneous environments, an argon atom and a benzene molecule were sandwiched by positive point charges. In both cases EPIC led to an accurate induced electrostatic potential relative to B3LYP. The ab initio derived AMOEBA polarizable force field parameters were used for comparison and show a significant quantitative discrepancy of the out-of-plane potential. In agreement with Schropp and Tavan, we attribute this deficiency to the difficulty of atom centered polarizabilities to account for locally varying electric field.

We also applied our independently generated charges, radii and dielectrics to calculate the cation-π electrostatic interaction energy between a benzene molecule and a proton. This energy corresponds, more generally, to the electrostatic component for the binding of Li+, Na+ or K+ to benzene where the induction energy is predominant. The results show that EPIC with parameters derived uniquely on the monomer lead to B3LYP quality binding energies. In addition, the H-bonding electrostatic energy of the 4-pyridone dimer has been examined and we found that EPIC/P2E quantitatively matches the approximated B3LYP electrostatics and total interaction energies whereas the non-polarizable term obtained with fixed charges derived from the ESP were not sufficient. Although we have not covered an exhaustive intermolecular list, these two applications are challenging cases that clearly show that the approach can work. Our fitting strategy of the electrostatic on the monomers can be easily generalized. In the 4-pyridone dimer example, we also show that the vdW term, needed to obtain the full energy, would not have to compensate for the poor electrostatic at short distances. This is one important and expected advantage from an accurate polarizable electrostatic model.

This work shows a new and potentially advantageous electrostatic term which could be applied to molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo simulations. Recently, molecular dynamics simulations using a PB solver to include implicitly the effects of solvent polarization were successfully carried out 2, 3, 15, 45–48 In order to fully use the concepts discussed herein as the electrostatic foundation of a force field, there are remaining scientific points to be addressed. The dielectric boundary will require a special attention if stable forces are to be calculated. Also, transferability of the parameters obtained from ab initio gas-phase calculations to the condensed phase need to be addressed. The extension of the parameterization will command a major effort not only for the electrostatic term, but also for all the other force field terms which need to balance the electrostatics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Chen from Lamar University for providing to us the coordinates of the optimized 4-pyridone dimer. We thank Daniel J. McKay from Merck Frosst and Georgia McGaughey from Merck & Co. for useful comments on the manuscript. This work was made possible by the computational resources of Réeseau Québécois de Calcul Haute Performance (RQCHP). The authors are grateful to OpenEye Inc. for free academic licenses. J.-F.T. thanks the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) for a Canada graduate scholarship (CGS D) and Merck & Co. for support through the MRL Doctoral Program. R. I. I. acknowledges financial support from the NSERC. B. R. is supported by NIH grant GM072558

Bibliography

- 1.Truchon J-F, Nicholls A, Iftimie RI, Roux B, Bayly CI. Accurate Molecular Polarizability based on Continuum Electrostatics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:1480–1493. doi: 10.1021/ct800123c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maple JR, Cao YX, Damm WG, Halgren TA, Kaminski GA, Zhang LY, Friesner RA. A polarizable force field and continuum solvation methodology for modeling of protein-ligand interactions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2005;1:694–715. doi: 10.1021/ct049855i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnieders MJ, Baker NA, Ren P, Ponder JW. Polarizable atomic multipole solutes in a Poisson-Boltzmann continuum. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:124114. doi: 10.1063/1.2714528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayly CI, Cieplak P, Cornell WD, Kollman PA. A Well-Behaved Electrostatic Potential Based Method Using Charge Restraints for Deriving Atomic Charges - the Resp Model. J. Phys. Chem. 1993;97:10269–10280. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jakalian A, Bush BL, Jack DB, Bayly CI. Fast, efficient generation of high-quality atomic Charges. AM1-BCC model: I. Method. J. Comput. Chem. 2000;21:132–146. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakalian A, Jack DB, Bayly CI. Fast, efficient generation of high-quality atomic charges. AM1-BCC model: II. Parameterization and validation. J. Comput. Chem. 2002;23:1623–1641. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan YH, Luo R. Continuum treatment of electronic polarization effect. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:094103. doi: 10.1063/1.2436871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becke AD. Density-Functional Thermochemistry .3. the Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becke AD. A New Mixing of Hartree-Fock and Local Density-Functional Theories. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:1372–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephens PJ, Devlin FJ, Chabalowski CF, Frisch MJ. Ab-Initio Calculation of Vibrational Absorption and Circular-Dichroism Spectra Using Density-Functional Force-Fields. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:11623–11627. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaussian 03, Revision, version C.02. Wallingford CT, USA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frisch MJ, Pople JA, Binkley JS. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods 25. Supplementary functions for Gaussian basis sets. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;80:3265–3269. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon S, Duran M, Dannenberg JJ. How does basis set superposition error change the potential surfaces for hydrogen bonded dimers? J. Chem. Phys. 1996;105:11024–11031. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boys SF, Bernardi F. The calculation of small molecular interactions by the differences of separate total energies. Mol. Phys. 2002;100:65–73. Some procedures with reduced errors (Reprinted from Molecular Physics, vol 19, pg 553-566, 1970) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant JA, Pickup BT, Nicholls A. A smooth permittivity function for Poisson-Boltzmann solvation methods. J. Comput. Chem. 2001;22:608–640. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richards FM. Areas, Volumes, Packing, and Protein-Structure. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 1977;6:151–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.06.060177.001055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bondi A. van der Waals Volumes and Radii. J. Phys. Chem. 1964;68:441–451. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh UC, Kollman PA. An Approach to Computing Electrostatic Charges for Molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 1984;5:129–145. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anisimov VM, Lamoureux G, Vorobyov IV, Huang N, Roux B, MacKerell AD. Determination of electrostatic parameters for a polarizable force field based on the classical Drude oscillator. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2005;1:153–168. doi: 10.1021/ct049930p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elking D, Darden T, Woods RJ. Gaussian induced dipole polarization model. J. Comput. Chem. 2007;28:1261–1274. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connolly ML. Solvent-Accessible Surfaces of Proteins and Nucleic-Acids. Science. 1983;221:709–713. doi: 10.1126/science.6879170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mobley DL, Dumont E, Chodera JD, Dill KA. Comparison of charge models for fixed-charge force fields: Small-molecule hydration free energies in explicit solvent. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:2242–2254. doi: 10.1021/jp0667442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mobley DL, Graves AP, Chodera JD, Shoichet BK, Dill KA. Predictive absolute binding free energy calculations for an engineered binding site in T4 Lysozyme. Biophys. J. 2007:368A–368A. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams DE, Abraha A. Site charge models for molecular electrostatic potentials of cycloalkanes and tetrahedrane. J. Comput. Chem. 1999;20:579–585. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams DE. Failure of Net Atomic Charge Models to Represent the Van-Der-Waals Envelope Electric-Potential of N-Alkanes. J. Comput. Chem. 1994;15:719–732. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholls A, Mobley DL, Guthrie JP, Chodera JD, Bayly CI, Cooper MD, Pande VS. Predicting small-molecule solvation free energies: An informal blind test for computational chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:769–779. doi: 10.1021/jm070549+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The B3LYP/cc-pVTZ ESP based bond charge corrections were obtained through private communications. Cooper, M.D.: Bayly, C.I; [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopes PEM, Lamoureux G, Roux B, MacKerell AD. Polarizable empirical force field for aromatic compounds based on the classical drude oscillator. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:2873–2885. doi: 10.1021/jp0663614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaminski GA, Stern HA, Berne BJ, Friesner RA, Cao YXX, Murphy RB, Zhou RH, Halgren TA. Development of a polarizable force field for proteins via ab initio quantum chemistry: First generation model and gas phase tests. J. Comput. Chem. 2002;23:1515–1531. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anisimov VM, Vorobyov IV, Lamoureux G, Noskov S, Roux B, MacKerell AD. CHARMM all-atom polarizable force field parameter development for nucleic acids. Biophys. J. 2004;86:415A–415A. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stern HA, Kaminski GA, Banks JL, Zhou RH, Berne BJ, Friesner RA. Fluctuating charge, polarizable dipole, and combined models: Parameterization from ab initio quantum chemistry. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1999;103:4730–4737. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jorgensen WL, Severance DL. Aromatic-aromatic interactions: free energy profiles for the benzene dimer in water, chloroform, and liquid benzene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:4768–4774. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caldwell JW, Kollman PA. Cation-Pi Interactions - Nonadditive Effects Are Critical in Their Accurate Representation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:4177–4178. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuzuki S, Yoshida M, Uchimaru T, Mikami M. The Origin of the Cation/pi; Interaction: The Significant Importance of the Induction in Li+ and Na+ Complexes. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001;105:769–773. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gallivan JP, Dougherty DA. Cation-pi interactions in structural biology. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:9459–9464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roux B. Nonadditivity in Cation Peptide Interactions - A Molecular-Dynamics and Ab-initio Study of Na+ in the Gramicidin Channel. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1993;212:231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma JC, Dougherty DA. The cation-pi interaction. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:1303–1324. doi: 10.1021/cr9603744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiner SJ, Kollman PA, Case DA, Singh UC, Ghio C, Alagona G, Profeta S, Weiner PA. New Force-Field for Molecular Mechanical Simulation of Nucleic-Acids and Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:765–784. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cornell WD, Cieplak P, Bayly CI, Gould IR, Merz KM, Ferguson DM, Spellmeyer DC, Fox T, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA. A 2Nd Generation Force-Field for the Simulation of Proteins, Nucleic-Acids, and Organic-Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:5179–5197. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo H, Gresh N, Roques BP, Salahub DR. Many-body effects in systems of peptide hydrogen-bonded networks and their contributions to ligand binding: A comparison of the performances of DFT and polarizable molecular mechanics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:9746–9754. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo H, Salahub DR. Cooperative hydrogen bonding and enzyme catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 1998;37:2985–2990. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981116)37:21<2985::AID-ANIE2985>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen YF, Dannenberg JJ. Cooperative 4-pyridone H-bonds with extraordinary stability. A DFT molecular orbital study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:8100–8101. doi: 10.1021/ja060494l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harder E, Kim BC, Friesner RA, Berne BJ. Efficient simulation method for polarizable protein force fields: Application to the simulation of BPTI in liquid. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2005;1:169–180. doi: 10.1021/ct049914s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schropp B, Tavan P. The Polarizability of Point-Polarizable Water Models: Density Functional Theory/Molecular Mechanics Results. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:6233–6240. doi: 10.1021/jp0757356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luo R, David L, Gilson MK. Accelerated Poisson-Boltzmann calculations for static and dynamic systems. J. Comput. Chem. 2002;23:1244–1253. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prabhu NV, Zhu PJ, Sharp KA. Implementation and testing of stable, fast implicit solvation in molecular dynamics using the smooth-permittivity finite difference Poisson-Boltzmann method. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:2049–2064. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Im W, Beglov D, Roux B. Continuum Solvation Model: computation of electrostatic forces from numerical solutions to the Poisson-Boltzmann equation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1998;111:59–75. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu Q, Luo R. A Poisson--Boltzmann dynamics method with nonperiodic boundary condition. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;119:11035–11047. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.