Abstract

This study provides an examination of women’s perceptions of care provided by student doulas undertaking a formal qualification in doula support services. Feedback forms completed by women attended by student doulas undertaking a formal qualification in doula support services were analyzed. The women (N = 160) consistently rated the student doulas’ contribution to their experience of birth favorably. Qualitative analysis revealed that women value the presence of their student doulas highly with reference to the student doulas’ demeanor, support provided to family, interface with other health professionals, and learned skills. Within the Australian context, this study suggests that the support provided by student doulas that have completed a formal training course is held in positive regard by the women receiving their care.

Keywords: doula, women’s experiences, support, birth

Women during birth benefit from continuous labor support (Campbell, Lake, Falk, & Backstrand, 2006) with this aspect of their care potentially being provided adjunctive to and distinct from the activities of trained maternity care practitioners such as midwives or obstetricians (Rosen, 2004). Indeed, the work of doulas—laypeople trained in providing nonmedical support during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period (Australian Doula College [ADC], 2007)—includes listening, providing information, assisting in the development of a birth plan, and offering continuous support to the woman and her birth team. A doula does not perform clinical tasks such as vaginal exams or fetal heart monitoring and does not diagnose medical conditions or give medical advice.

The provision of doula care has been identified through international studies as assisting women to have positive birth experiences (Berg & Terstad, 2006; Breedlove, 2005; Koumouitzes-Douvia & Carr, 2006; Lundgren, 2008; Schroeder & Bell, 2005) and outcomes (Campbell et al., 2006; Campbell, Scott, Klaus, & Falk, 2007; Kennell, Klaus, McGrath, Robertson, & Hinkley, 1991; Klaus, Kennell, Robertson, & Sosa, 1986; McComish & Visger, 2009; McGrath & Kennell, 2008; Mottl-Santiago et al., 2008; Nommsen-Rivers, Mastergeorge, Hansen, Cullum, & Dewey, 2009; Van Zandt, Edwards, & Jordan, 2005). The research evaluating birth outcomes has generally focused on objective measurements such as use of analgesia and rates of intervention (Campbell et al., 2006; McGrath & Kennell, 2008; Mottl-Santiago et al., 2008; Van Zandt et al., 2005). From these studies, doula care has been associated with reduced rates of epidural use (McGrath & Kennell, 2008; Mottl-Santiago et al., 2008; Van Zandt et al., 2005), although others have found no such association (Campbell et al., 2006; Mottl-Santiago et al., 2008). Other research measuring the incidence of cesarean surgery (CS) in relation to doula care shows no difference overall, although some change in CS rates have been noted in women receiving doula care and also being attended by a midwife rather than a physician (Mottl-Santiago et al., 2008). Breastfeeding has also been used as an outcome to assess the impact of doula care and has been found to have a positive effect from the results of both cohort studies (Mottl-Santiago et al., 2008) and intervention studies (Nommsen-Rivers et al., 2009).

In conjunction with outcomes-based research, women’s experiences of their birth and the value of doula care has been reported. This research has predominantly drawn on qualitative research design and includes women from a diverse range of demographic groups such as disadvantaged teens (Breedlove, 2005), incarcerated women (Schroeder & Bell, 2005), and single mothers (Lundgren, 2008). These high-need populations report high levels of appreciation and support for doulas who are perceived as aiding a positive life experience (Breedlove, 2005; Lundgren, 2008; Schroeder & Bell, 2005). Beyond these specific subgroups, more general populations of women have also been investigated with study findings showing the description of doula care as a positive contribution to the birthing experience (Berg & Terstad, 2006; Koumouitzes-Douvia & Carr, 2006). The specific activities contributing to doula support identified as beneficial by women receiving their care is quite diverse, although fairly consistent across research papers. This includes support to the woman’s partner and family (Koumouitzes-Douvia & Carr, 2006; McComish & Visger, 2009), interacting and communicating with other health professionals (Berg & Terstad, 2006; Lundgren, 2008; McComish & Visger, 2009; Schroeder & Bell, 2005), and providing antenatal education (Berg & Terstad, 2006; Breedlove, 2005; McComish & Visger, 2009; Nommsen-Rivers et al., 2009). Beyond such interpersonal expertise, other practical skills employed during intrapartum (Van Zandt et al., 2005) and in the postnatal period (McComish & Visger, 2009) are also valued by women.

However, much of this previous research has focused on either doula care introduced to women after admittance to hospital following the onset of labor (McGrath & Kennell, 2008; Nommsen-Rivers et al., 2009; Van Zandt et al., 2005) or care provided by fully qualified/certified doulas (Berg & Terstad, 2006; Breedlove, 2005; Koumouitzes-Douvia & Carr, 2006; Lundgren, 2008; McComish & Visger, 2009; McGrath & Kennell, 2008; Mottl-Santiago et al., 2008; Nommsen-Rivers et al., 2009; Schroeder & Bell, 2005). Unfortunately, the definition of training or certification of doulas remains inconsistent, and such training can vary between a weekend workshop and a 6–7 months course (Childbirth International, 2008). Furthermore, research projects that have included the use of untrained laypeople for the purpose of providing doula care as part of the intervention have relied on between 0 and 4 hours of doula training (Campbell et al., 2006; Campbell et al., 2007; Van Zandt et al., 2005). Within this broad scope of research, inquiry into the experience of women receiving care by student doulas as part of a formal course has not been undertaken.

Despite inconsistencies, doula training has evolved in several countries such as the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, and Australia. In the United Kingdom and Australia, available courses in doula care range from 3 days to 9 months, whereas courses in the United States vary between 2 days and 7 months (Childbirth International, 2008). Doulas are not regulated in any of these countries. However, there are attempts within the United Kingdom, United States, and Switzerland to provide minimum standards through professional associations and certification processes (Doulas of North America [DONA] International, 2005; Doula UK Ltd., n.d.; The Swiss Association of Doulas, 2011).

A recent development in Australia is the availability of a government-accredited Certificate IV in Doula Support Services. This course is a 6-month doula training program delivered through the ADC. The course requires, among other activities, that students attend three supported births before final qualification. It includes both practical skills and psychosocial development to ensure that qualified doulas are able to provide nonjudgmental, respectful, and empowering support to women during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period (ADC, 2009). Prior to course completion, students are expected to provide antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal support to three women. This can occur any time after week 10 of the course by which time the students have covered a range of topics including pregnancy, communication skills, understanding the system, dad/partner support, last trimester complications, prelabor, induction (natural and medical), first and second stage, cesarean surgery, and vaginal births after cesarean (VBAC). Women whose births are attended by student doulas are invited to complete a feedback form, which describes their experience of the care received from their student doulas. Given the paucity of Australian data regarding doula care and this recent development in the Australian doula education landscape, examination of the impact of trained doulas on women receiving care during the antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal period is needed. This article reports the analyses of data obtained via the ADC feedback forms and as such constitutes the first empirical data regarding the care provided by student doulas completing a formal and structured doula training program and the first examination of doula care in the Australian setting.

METHODS

Sample

Women attended by student doulas from ADC over a 4-year period were invited to complete a feedback form describing their experience of the support received from their student doulas. The women were asked to sign a release statement associated with a feedback form, which permitted deidentified data to be made available to external researchers for analysis.

Instrument

The feedback form included both structured questions and an “open” qualitative comments section. Variables of interest included demographic data, location of birth, birth method, and women’s opinions of the student doulas’ contribution, with particular reference to physical aspects, emotional aspects, assistance to the support person, and, lastly, overall usefulness.

Demographic and Birth Characteristics

Identification of a partner was classified as either existent or nonexistent. Women were also asked about their ethnicity, number of living children, history of CS, and intention to undertake VBAC. The women were asked to identify the location where the birth took place based on three categories: hospital, home, and independent birth center. Similarly, the practitioner providing the primary care through their pregnancy and birth was also determined. The duration of Stage 1, Stage 2, and Stage 3 were self-reported, as was the occurrence of spontaneous rupture of membranes.

Experience of Student Doula Care

The respondents’ rating of the care provided by their doulas was determined through responses to a 5-point Likert scale across four domains: physical aspects, emotional aspects, support person, and usefulness. Because of the high number of positive responses, these four domains were recoded to the following binary categories: negative/neutral and positive. The recoded variable was then analyzed against several potential predictors to identify any relationships between the variables. An open comment section was also provided where the women could provide further details regarding their experience of the care provided by their student doulas.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics that were used included frequencies, percentages, and means with associated standard deviations. Pearson’s chi-square tests were used to test for association between categorical variables, and a Fisher’s exact test was used for variables with low frequency categories. A p value of < .05 was adopted to determine the level of statistical significance. Analyses were conducted using the statistical software Stata 11.1.

Qualitative Analyses

Thematic analysis of the open comments was conducted using a grounded theory approach (Hansen, 2006). This was a process of inductive analysis of themes grounded in the qualitative data collected. Comments were then organized under these themes. To triangulate the interpretation of the qualitative data, a second researcher also conducted a separate analysis of several comments, and any inconsistency across the two interpretations discussed and resolved by the research team were applicable.

FINDINGS

Quantitative Results

Survey response. Feedback forms were completed by women (N = 160) each attended by a student doula from ADC. Because submissions of feedback forms are a requirement in the final assessment of student doulas, all questionnaires were completed and included in the analysis. However, because not all questions were answered by all participants, response rates to individual questions varied between 55% and 100%.

Demographics.

As reported in Table 1, the mean gestation at birth for the participating women was 40 (SD = 1.33) weeks. Most had not had a previous cesarean (85.9%), and many had no children (M = 1.2, SD = 0.86). Most (97.6%) of the respondents reported having a partner and were Australian born (74.3%). Most commonly, the women birthed in hospital (88.5%) and were attended by a midwife (61.5%).

TABLE 1. Demographics and Characteristics of Participants (N = 160).

| Demographics | n | % |

| Husband/partner present | ||

| Yes | 120 | 97.6 |

| No | 3 | 2.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Australian born | 84 | 74.3 |

| Other English speaking | 4 | 3.5 |

| European born | 11 | 9.7 |

| Asian born | 7 | 6.2 |

| Other | 7 | 6.2 |

| Number of children | ||

| None | 21 | 17.2 |

| One | 67 | 54.9 |

| Two | 26 | 21.3 |

| Three or more | 8 | 6.6 |

| Birthplace | ||

| Hospital | 115 | 88.5 |

| Home | 11 | 8.5 |

| Independent birth center | 4 | 3.1 |

| Carer | ||

| Obstetrician | 34 | 26.2 |

| Midwife | 80 | 61.6 |

| GP | 16 | 12.3 |

| History of cesarean birth | ||

| Yes | 61 | 38.1 |

| No | 99 | 61.9 |

| Attempting a vaginal birth after cesarean | ||

| Yes | 14 | 15.7 |

| No | 75 | 84.3 |

| Spontaneous rupture of membranes | ||

| Yes | 69 | 54.8 |

| No | 57 | 45.2 |

| Birth outcome | ||

| Vaginal birth | 103 | 64.4 |

| Cesarean after onset of labor | 47 | 29.4 |

| Cesarean before onset of labor | 10 | 6.3 |

| Undertook breastfeeding | ||

| Yes | 115 | 89.2 |

| No | 14 | 10.8 |

| M | SD | |

| Gestation | 40.0 weeks | 1.33 |

| Duration of Stage 1 | 8.1 hr | 10.4 |

| Duration of Stage 2 | 59.1 hr | 49.4 |

| Duration of Stage 3 | 21.6 hr | 19.9 |

| Total time in attendance by student doula | 11.4 hr | 6.8 |

| Intrapartum time in attendance by student doula | 10.6 hr | 7.5 |

| Postnatal time in attendance by student doula | 3.9 hr | 5.5 |

Note. GP = general practitioner.

Experience of student doula care.

The women overwhelmingly rated their opinion of their student doulas’ contribution positively across all four domains (see Table 2). Analysis of the association between the perceived contribution of the doula and the location of the birth, primary maternity carer, and the woman’s ethnicity identified no predictive relationships (see Tables 3 and 4). However, as seen in Table 3, interesting relationships were identified regarding other characteristics with women who breastfed their baby (p = .03) or who had not had a previous cesarean (p = .005) more likely to rate the physical support provided by their student doulas more positively. The exact nature of this relationship is not clear, particularly because there were no significant findings across the other domains in relation to these characteristics.

TABLE 2. Women’s Opinion of Their Student Doulas’ Contribution.

| Domain | Responses n (%) | More Harm Than Good (%) | Neither Helped nor Hurt (%) | Did the Job (%) | Was More Helpful (%) | Outstanding (%) |

| Physical aspects | 141 (88.1) | 0 | 1.4 | 4.2 | 32.6 | 61.7 |

| Emotional aspects | 144 (90.0) | 0 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 23.6 | 74.3 |

| Support person | 136 (85.0) | 0 | 2.2 | 5.2 | 23.5 | 69.1 |

| Usefulness | 141 (88.1) | 0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 13.5 | 85.1 |

TABLE 3. Women’s Ethnicity, Infant Feeding Choice, and History of Cesarean Birth Compared With Their Opinion of the Contribution of Their Student Doulas to Their Birth (N = 160).

| Domain | Response | Ethnicity | p | Infant Feeding Choice | p | History of Cesarean Birth | p | |||

| Australian born | Non-Australian born | Breastfeeding | No Breastfeeding | Previous Cesarean | No Previous Cesarean | |||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Physical | Negative/neutral | 3 (3.6) | 5 (6.6) | .31 | 4 (3.5) | 3 (21.4) | .03a | 7 (11.5) | 1 (1.0) | .005b |

| Positive | 81 (96.4) | 71 (93.4) | 111 (96.5) | 11 (78.6) | 54 (88.5) | 98 (99.0) | ||||

| Emotional | Negative/neutral | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.4) | .54 | 2 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | .79 | 1 (1.6) | 2 (2.0) | .68 |

| Positive | 75 (98.7) | 82 (97.6) | 113 (98.3) | 14 (100.0) | 60 (98.4) | 97 (98.0) | ||||

| Support persons | Negative/neutral | 4 (5.3) | 66 (7.1) | .44 | 6 (5.2) | 1 (7.1) | .56 | 4 (6.6) | 6 (6.1) | .57 |

| Positive | 72 (94.7) | 78 (92.9) | 109 (94.8) | 13 (92.9) | 57 (93.4) | 93 (93.9) | ||||

| Usefulness | Negative/neutral | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | .22 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.0) | .38 |

| Positive | 74 (97.4) | 84 (100.0) | 115 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 61 (100.0) | 97 (98.0) | ||||

aStatistically significant relationship between women’s opinions of the physical contribution of their student doula and women’s choice of breastfeeding.

bStatistically significant relationship between women’s opinions of the physical contribution of their student doulas and women’s history of cesarean birth.

TABLE 4. Women’s Primary Maternity Carer and Birth Location Compared With Their Opinion of the Contribution of Their Student Doulas to Their Birth (N = 160).

| Domain | Response | Primary Maternity Carer | Birth Location | p | ||||

| Obstetrician | Midwife | Other | Hospital | Nonhospital | ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Physical | Negative/neutral | 2 (5.9) | 5 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | .87 | 6 (5.2) | 2 (4.4) | .60 |

| Positive | 32 (94.1) | 75 (93.8) | 16 (100.0) | 109 (94.8) | 43 (95.6) | |||

| Emotional | Negative/neutral | 1 (2.9) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | .62 | 2 (1.7) | 1 (2.2) | .63 |

| Positive | 33 (97.1) | 79 (98.8) | 16 (100.0) | 113 (98.3) | 44 (97.8) | |||

| Support persons | Negative/neutral | 1 (2.9) | 5 (6.3) | 1 (6.3) | .74 | 6 (5.2) | 4 (8.9) | .30 |

| Positive | 33 (97.1) | 75 (93.8) | 15 (93.8) | 109 (94.8) | 41 (91.1) | |||

| Usefulness | Negative/neutral | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.4) | .08 |

| Positive | 34 (100.0) | 80 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 115 (100.0) | 43 (95.6) | |||

Qualitative Results

Thematic analysis of the respondents’ written comments provides further support for the women’s positive experiences and evaluations of their student doulas as ascertained from the closed survey responses. From qualitative analysis, the women’s perceived value of the support given by the student doulas was separated into themes associated with the support provided by the doula to the family, the doula’s confident and calm demeanor, and the doula’s provision of valuable skills to aid the woman during birth. Less dominant themes included the relationship between the doula and other health professionals and a perception that the doula has an impact on the birth outcome.

The women overwhelmingly rated their opinion of their student doulas’ contribution positively across all four domains.

The overall theme from the qualitative data is that the women valued the presence of their doulas. This perspective can be seen in the following comment:

“I consider myself blessed to have such an amazing person in my life sharing my precious birth experience and believing in me.”

Comments such as this were repeated throughout the qualitative data and provide strong evidence that the women perceived their student doulas and the care they provided in a very positive light.

Support for the Family

Many of the women explained how their student doulas undertook a valuable role in not only supporting them but also supporting their wider immediate family unit. In particular, and as seen in the following comments, the support provided to husbands/partners was very highly valued:

“[doula] gave my husband, mother, and myself so much support and confidence.”

“She supported me and my husband’s wishes at a very emotional and physically demanding time.”

A Source of Calm Confidence

The participants often described how their student doulas provided and promoted an attitude and atmosphere of calm and confidence irrelevant of the immediate circumstances. The women drew strength from this calm attitude to assist them in their birth, as the following comments explain:

“It was wonderful to have such a calm and reassuring person present.”

“During the 12 hours at home/in birth center, and the 8 hours in labor ward [doula] provided me with calm, informed, encouraging, clear support.”

From these comments, it can be seen that the calm confidence described by the women may have been perceived to be through specific actions of the student doulas, or it may simply have been through nonspecific “presence.”

A Provider of Valuable Skills

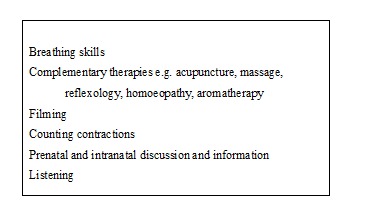

The women also described learned skills, traits, and abilities demonstrated by their student doulas as valuable additions to the care they received. A range of qualities and skills were identified through the analysis (see Figure 1) and were enlisted at different stages throughout the women’s relationship with their student doulas. This includes antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal care. The following comments highlight a number of these:

Figure 1.

Skills valued by the women which were displayed by student doulas.

“[doula]’s skills were invaluable. The prebirth meetings really helped [partner] and I to prepare.”

“She got cups of tea and snacks and did lots of little but important jobs.”

“I particularly liked her hand massage technique during contractions.”

An Interprofessional Liaison

Many women explained how they valued the contribution of their student doulas in negotiating and communicating with other staff within the hospital setting. In some cases, this was regarding fostering a collaborative practitioner environment, translating medical terminology for the women, assisting the women in communicating effectively with their maternity care providers, and/or navigating the hospital bureaucracy and policies.

“ . . . the communication between the nurse and [partner] and I (via [doula]) has helped us enormously—the explanation of medical terms and support of natural birth”

“We felt she was a mediator between us and the hospital with its policies.”

Impacting Birth Outcome

Several respondents also expressed a belief that the doulas’ presence had a direct effect on the birth outcome. The women explained that this may be via the doulas helping to avoid (what the women perceived as) unwanted interventions or via helping reduce the duration of the recovery period. Examples of comments reflecting these issues are seen in the following:

“Her suggestions on how to minimize the labor pains were also very helpful and it made it possible for us to have a normal vaginal delivery.”

“We couldn’t have achieved the fantastic birth we did without her help.”

Changing Perceptions of Other Maternity Professionals

Women perceived the actions and conduct of their student doulas as changing the opinions of other health professionals regarding the value of doulas. These changes in opinion (toward a more positive understanding) were reported by the women with reference to both doctors and midwives:

“One midwife told me that she changed her perspective toward a doula because she was very impressed by [doula].”

“[doula] was great with hospital staff including my obstetrician . . . who thought [doula] was most helpful and supportive.”

DISCUSSION

This is the first study worldwide to examine the experience of women receiving care from student doulas undertaking a formal doula qualification. The findings from this research suggest that women value the support received from a student doula completing a formal course in doula care.

The women’s perceptions of the relationship between the support from their student doulas and their birth outcomes is interesting as several previous studies have focused on objective measurement of birth outcomes and analgesia use as an assessment of physical benefits. One such study (Van Zandt et al., 2005), which used student nurses as doulas who supported women through vaginal births (n = 89), found that women in the treatment group used less epidural (OR = 0.62) when their doulas used complementary interventions (defined as activities beyond emotional support including massage, showering, reinforcement of the birth plan, discussion of options, etc.). Similar results of lower rates of epidural analgesia were reported by a larger randomized controlled trial (McGrath & Kennell, 2008) of women (N = 420) in which the intervention group were randomly assigned a doula (not met antenatally) when arriving at hospital in early active labor. In contrast, a larger controlled study (Campbell et al., 2006) of birthing women (N = 600) assessed the outcomes of an intervention group who received support from a layperson (previously known to the woman) who had received at total of 4 hours training in doula care in preparation for participating in the study. The doula group showed no difference in the type of analgesia or incidence of CS. However, they did find a shorter length of labor and greater cervical dilation at the time of epidural. Similarly, a retrospective cohort analysis (Mottl-Santiago et al., 2008) of women (N = 11,471) receiving social support from a layperson through a hospital-based doula program in prenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal care found no difference in rates of epidural use, CS, or operative vaginal births. Through this study, we found a different relationship between CS and doula care to the previous two studies because the women who had a history of CS were less likely to positively rate the physical support provided by their student doulas. This may be because of the women with a history of CS feeling less prepared for the experience of vaginal birth or it may simply be reflective of them not having a vaginal birth and therefore needing less physical support from their student doulas.

Another interesting finding from the previous cohort study (Mottl-Santiago et al., 2008) was the impact of a maternity care provider on these results. Primiparous women receiving care from a doula and a midwife had lower rates of CS which contrasts with primiparas receiving care from a doula and a physician who had no difference in CS rates when compared with controls. Based on the results of this study, however, different primary maternity carers do not seem to impact women’s perceived value of student doulas’ care. This study did identify a link between the apparent importance of the physical support provided by the student doula and the likelihood of breastfeeding. Although previous research has not examined this link, a positive impact of doula care on breastfeeding has been reported (Mottl-Santiago et al., 2008; Nommsen-Rivers et al., 2009).

Compared with women’s perceptions of physical support, the significance of emotional support provided by a doula has received much more attention, mostly through qualitative research. This was consistent across a diverse range of demographic groups including disadvantaged teens (Breedlove, 2005), incarcerated women (Schroeder & Bell, 2005), single mothers (Lundgren, 2008), as well as study samples more representative of the general population (Berg & Terstad, 2006; Koumouitzes-Douvia & Carr, 2006). The study of incarcerated women (N = 18; Schroeder & Bell, 2005) who received antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal doula care found that the doula was important to the women’s experience of birth. Again, this is also reflected in the comments made by the women in this study who expressed a belief that the student doulas’ presence had a direct effect on their birth experience and outcome. The positive effect of the emotional support provided by the student doulas may also be related to promoting an expectation of a desired outcome through antenatal discussions, as reported in other studies (Breedlove, 2005; Campbell et al., 2007).

Our findings also suggest that the value placed on the student doulas was not only the support they gave directly to the women but also the interactions and support they provided to others in the care team. For example, the assistance provided to other support persons such as husbands was very clearly expressed by the women. This response has also been reported in other studies particularly regarding doula’s providing postnatal care (Koumouitzes-Douvia & Carr, 2006; McComish & Visger, 2009). Similarly, although this study did not evaluate the perceptions of the other maternity care providers in relation to support given by the student doula, the women did suggest that the health-care professionals caring for them during labor held a positive regard for their student doulas. Although this is only based on the perception of the woman and may not reflect the experience of either student doula or the health professionals, this does not detract from the value such a perception may bring to the woman’s birth experience. However, this finding is also reflected in the study of incarcerated women (Schroeder & Bell, 2005) through which maternity carers and correctional officers rated their satisfaction with doula care highly. The role of the doula in terms of contributing to the communication and relationship between the women, their families, and their maternity care providers was also identified in other studies in which the doula has been described as a mediator (Berg & Terstad, 2006; Lundgren, 2008) and advocate (McComish & Visger, 2009).

The value placed on the student doulas was not only the support they gave directly to the women but also the interactions and support they provided to others in the care team.

Finally, an interesting finding from this study was the overall perceived usefulness of the care given by the student doulas toward the women. The positive regard identified in this study may be related to the variety of skills the student doulas demonstrated. In particular, the role of the student doula in education and information provision during antenatal meetings is consistently reported by other researchers (Berg & Terstad, 2006; Breedlove, 2005; McComish & Visger, 2009; Nommsen-Rivers et al., 2009) as a highly valued aspect of doula care. Other supportive skills identified through this study which are used more often during labor (such as massage, breathing skills, and filming/photography; Van Zandt et al., 2005) and postnatally (such as domestic duties; McComish & Visger, 2009) have also been reported.

The limitations of this study are largely associated with the survey tool. As the survey was completed by the women, some aspects of the medical information (such as duration of labor and attendance time of doula) may be affected by recall bias and the women’s understanding of medical terminology. Also, the small sample size of the study meant that we may not have had the statistical power to detect differences/associations. In terms of the qualitative analysis, the nature of the content derived from open comments, which provides no facility to further prompt, probe, or clarify meaning, acts to limit the study analyses. The recent developments in doula training in Australia and the variability in maternity care internationally may also limit the data generalizability beyond the Australian context.

Within the scope of doula research, this study highlights other areas that would benefit from additional investigation. Although there has been research into the benefits of doula care compared with standard care, these have not commonly been conducted in a mixed methodology format which includes both objective and subjective outcomes as well as quantitative and qualitative methods. It would also be beneficial to include the perspective of support persons (such as husbands) and the maternity health professionals in the research design of future studies. This is particularly important as current Australian research does not differentiate between trained and untrained doulas when examining midwives’ perceptions of doulas role in maternity care (Stevens, Dahlen, Peters, & Jackson, 2011). More specific research is also needed to compare the difference in outcomes between laypeople providing continuous care with little or no training and formally trained and certified doulas. Finally, because of the absence of any real data on Australian doulas, a workforce survey describing the employment, education, and service profile of individuals providing doula care in Australia is needed.

CONCLUSION

The care provided by student doulas that have completed a formal training course is held in positive regard by the women receiving their care. This is consistent across physical and emotional support as well as the value to the other support persons and the overall usefulness of the student doula. Student doulas are valued in several areas and provide important skills to the woman during birth. Given the diversity of training available for those wishing to offer doula services, it may be of benefit to carefully consider the value women place on the support they receive from doulas who have completed formal training and ensure best practice standards are applied. Although more research in this area is required, these findings may be of interest to hospital administrators, maternity care professionals, policy makers, and consumers.

Biographies

AMIE STEEL, Grad Cert Ed (Higher Ed), BHSc (Nat), University of Technology Sydney.

HELENE DIEZEL, BA (SocSc), Embrace Holistic Services.

KATE JOHNSTONE, BIR, director, Embrace Holistic Services.

DAVID SIBBRITT, BMath, MMedStat, PhD, associate professor in Biostatistics, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle.

JON ADAMS, BA(Hons), MA, PhD, director of Network of Researchers in the Public Health of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NORPHCAM) and professor in Public Health, Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery and Health, University of Technology Sydney.

RENEE ADAIR, Cert IV, Doula Support Services, principal of Australian Doula College.

REFERENCES

- Australian Doula College (2007). What is a doula? Retrieved from http://www.australiandoulacollege.com.au/what_is_a_doula_/

- Australian Doula College (2009). Course information. Retrieved from http://www.australiandoulacollege.com.au/doula_training/course_information.htm

- Berg M., & Terstad A. (2006). Swedish women’s experiences of doula support during childbirth. Midwifery, 22(4), 330–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breedlove G. (2005). Perceptions of social support from pregnant and parenting teens using community-based doulas. Journal of Perinatal Education, 14(3), 15–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D. A., Lake M. F., Falk M., & Backstrand J. R. (2006). A randomized control trial of continuous support in labor by a lay doula. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 35(4), 456–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D., Scott K. D., Klaus M. H., & Falk M. (2007). Female relatives or friends trained as labor doulas: Outcomes at 6 to 8 weeks postpartum. Birth, 34(3), 220–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childbirth International (2008). Birth doula—compare training programs. Retrieved from http://www.childbirthinternational.com/birth_doula/compare.htm

- Doulas of North America International (2005). DONA International, 2011-11-30. Retrieved from www.dona.org

- Doula UK Ltd (n.d). About Doula UK. Retrieved from http://doula.org.uk/content/about-doula-uk

- Hansen E. C. (2006). Successful qualitative research: A practical introduction. Berkshire, United Kingdom: Open University Press [Google Scholar]

- Kennell J., Klaus M., McGrath S., Robertson S., & Hinkley C. (1991). Continuous emotional support during labor in a US Hospital. Journal of the American Medical Association, 265, 2197–2201 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus M., Kennell J., Robertson S., & Sosa R. (1986). Effects of social support during parturition on maternal and infant morbidity. British Medical Journal, 293, 585–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koumouitzes-Douvia J., & Carr C. A. (2006). Women’s perceptions of their doula support. Journal of Perinatal Education, 15(4), 34–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren I. (2008). Swedish women’s experiences of doula support during childbirth. Midwifery, 26(2), 173–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McComish J. F., & Visger J. M. (2009). Domains of postpartum doula care and maternal responsiveness and competence. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 38(2), 148–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath S. K., & Kennell J. H. (2008). A randomized controlled trial of continuous labor support for middle-class couples: Effect on cesarean delivery rates. Birth, 35(2), 92–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottl-Santiago J., Walker C., Ewan J., Vragovic O., Winder S., & Stubblefield P. (2008). A hospital-based doula program and childbirth outcomes in an urban, multicultural setting. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 12(3), 372–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nommsen-Rivers L. A., Mastergeorge A. M., Hansen R. L., Cullum A. S., & Dewey K. G. (2009). Doula care, early breastfeeding outcomes, and breastfeeding status at 6 weeks postpartum among low-income primiparae. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 38(2), 157–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen P. (2004). Supporting women in labor: Analysis of different types of caregivers. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health, 49(1), 24–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder C., & Bell J. (2005). Doula birth support for incarcerated pregnant women. Public Health Nursing, 22(1), 53–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J., Dahlen H., Peters K., & Jackson D. (2011). Midwives’ and doulas’ perspectives of the role of the doula in Australia: A qualitative study. Midwifery, 27(4), 509–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Swiss Association of Doulas (2011). Doula geburtsbegleitung, 2011-11-30. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zandt S. E., Edwards L., & Jordan E. T. (2005). Lower epidural anesthesia use associated with labor support by student nurse doulas: Implications for intrapartal nursing practice. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 11(3), 153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]