Abstract

Mycoplasma gallisepticum is an important avian pathogen that commonly induces chronic respiratory disease in chicken. To better understand the mycoplasma factors involved in host colonization, chickens were infected via aerosol with two hemadsorption-negative (HA−) mutants, mHAD3 and RCL2, that were derived from a low passage of the pathogenic strain R (Rlow) and are both deficient in the two major cytadhesins GapA and CrmA. After 9 days of infection, chickens were monitored for air sac lesions and for the presence of mycoplasmas in various organs. The data showed that mHAD3, in which the crmA gene has been disrupted, did not promote efficient colonization or significant air sac lesions. In contrast, the spontaneous HA− RCL2 mutant, which contains a point mutation in the gapA structural gene, successfully colonized the respiratory tract and displayed an attenuated virulence compared to that of Rlow. It has previously been shown in vitro that the point mutation of RCL2 spontaneously reverts with a high frequency, resulting in on-and-off switching of the HA phenotype. Detailed analyses further revealed that such an event is not responsible for the observed in vivo outcome, since 98.4% of the mycoplasma populations recovered from RCL2-infected chickens still display the mutation and the associated phenotype. Unlike Rlow, however, RCL2 was unable to colonize inner organs. These findings demonstrate the major role played by the GapA and CrmA proteins in M. gallisepticum host colonization and virulence.

INTRODUCTION

The wall-less bacterium Mycoplasma gallisepticum is an important avian pathogen that commonly induces chronic respiratory disease in chickens (1–4) and sinusitis in turkeys (5). This avian mycoplasma is responsible for considerable economic losses worldwide, and consequently a large number of studies have been dedicated to better understand its biology and the factors involved in host interactions.

M. gallisepticum colonizes its host mainly via the mucosal surfaces of the respiratory tract, causing air sacculitis within a few days (6), and disseminates throughout the body. This systemic infection is reflected by the high rate of M. gallisepticum reisolation from inner organs such as the liver, heart, spleen, or kidney (6) and by its detection inside and at the surface of red blood cells of experimentally infected birds (7). Successful infection by M. gallisepticum may rely on two independent phenomena that provide the pathogen with defensive measures against host defenses. These are the high versatility of its surface architecture via phase-variable expression of surface antigens (8, 9) and the ability to establish facultative intracellular residence in nonphagocytic host cells (7, 10).

For colonization, dissemination, or cell invasion, the attachment of M. gallisepticum to host cells is a crucial event that is mediated primarily via a unipolar terminal organelle, a bleb-like structure containing several potential cytadhesins and accessory proteins. Among these are the products of the genes gapA (or mgc1) (11, 12) and crmA (or mgc3) (13, 14), which have been shown in independent in vitro studies to be the two major cytadhesins of M. gallisepticum strain R (13, 15).

Indeed, a high, avirulent passage of strain R (Rhigh) that lacks both GapA and CrmA has a diminished capacity to adhere to MRC5 human cells (13) and is deficient in binding erythrocytes on colonies (15) compared to a low, virulent passage of the same strain (Rlow). In Rhigh, the lack of GapA and CrmA is due to an additional adenine residue in the 5′ region of the structural gapA gene that results in a premature stop codon and has a negative polar effect on the transcription of the crmA gene located downstream (13). Interestingly, complementation of Rhigh with either gapA or crmA did not restore in vitro adhesion to MRC5 cells, while introduction of the gapA-crmA operon did (16). Although Rhigh transformants that have reacquired expression of both products induce air sacculitis in chickens, lesion scores were still lower than those observed with Rlow, and no tracheal lesions were detected (16). Collectively, these data suggest that both GapA and CrmA are required for adhesion but also that other factors lacking in Rhigh may contribute to virulence. This is further supported by a recent comparison of the Rhigh and Rlow genomes (17) that resulted in the identification of 29 open reading frames (ORFs) carrying mutations in Rhigh. However, their potential involvement in virulence remains to be experimentally addressed.

In contrast to the stable GapA/CrmA-negative phenotype of Rhigh, a reversible point mutation based on a base substitution at the beginning of the structural gapA gene was shown to govern a spontaneous, high-frequency phase variation in expression of gapA of RCL2 (15). This mutational event, which is distinct from that described above for Rhigh, also has a polar effect on the transcription of crmA resulting in the concomitant phase variation of the CrmA product. Oscillation in expression of the GapA and CrmA products is responsible for the variable binding of erythrocytes (hemadsorption [HA]) onto M. gallisepticum colonies (15). This was demonstrated using a lineage derived from RCL2 and composed of clonal variants that alternatively displayed the HA-positive (HA+) and HA− phenotypes and expressed or did not express the two cytadhesins, respectively. Phase variation in expression of surface components in pathogenic mycoplasma species has been extensively described, and a collection of genetic systems generating high-frequency phase variation has been reported (18–20). These mainly include gene families encoding related surface proteins and single-copy genes encoding molecules with adhesive properties. However, the significance and consequences of this phenomenon have been addressed in vivo only in the case of complex gene families (21, 22).

The aim of this study was to define in vivo the possible role played by phase variation in expression of GapA. For this purpose, the colonizing ability and the virulence of a well-characterized HA− variant, namely, RCL2, that belongs to the clonal lineage described above, lacks the GapA and CrmA products, and displays a base substitution in the gapA gene (15) were addressed in this study. Since the GapA and CrmA cytadhesins are believed to be important in infection, we postulated that a back-switching from HA− to HA+ might confer a selective advantage in vivo. We therefore monitored the expression of the cytadhesins GapA and CrmA and the gapA gene mutation in populations reisolated from RCL2-infected chickens. Parallel experiments were also done with the parental Rlow and Rhigh strains and with the previously described mHAD3 mutant, which was derived from Rlow by insertion of Tn4001mod in the crmA structural gene (15). In this mutant, disruption of the crmA gene resulted in the lack of a CrmA product and the production of a minute amount of GapA, with the mutant displaying an HA− phenotype identical to that of RCL2. The results presented in this study revealed that RCL2 and mHAD3 differ in virulence and in colonization of the birds. Interestingly, mHAD3 was avirulent and its reisolation rates were low compared to data obtained with RCL2. In contrast to our hypothesis, populations recovered from RCL2-infected chickens and analyzed did not revert to the HA+ phenotype. In light of these data, the potential role of GapA and CrmA in M. gallisepticum infection of chickens is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycoplasma strains and growth conditions.

The M. gallisepticum laboratory passages Rlow and Rhigh used in this study and by others worldwide (6, 15, 16, 23) were kindly provided by S. Levisohn, Kimron Veterinary Institute, Bet Dagan, Israel. Rlow and Rhigh correspond to the prototype strain R propagated 10 and 160 times in culture medium, respectively (24) and are therefore not clonal populations. The clonal variant RCL2 and the mutant mHAD3 were derived from Rlow by spontaneous mutation in the gapA gene (for RCL2) or by insertion of Tn4001mod in the crmA gene (for mHAD3). Consequently, these two mutants display the HA− phenotype, which correlates with the lack of expression of the gapA and crmA genes. RCL2 and mHAD3 were cloned as previously described (15).

Mycoplasmas were grown at 37°C in modified Hayflick medium (25) containing 20% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated horse serum (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) to mid-exponential growth phase, as indicated by the metabolic color change of the medium. The growth medium for mHAD3 was supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 gentamicin. The stability of the transposon insertion in mHAD3 was assessed by passaging an mHAD3 culture 40 times in Hayflick medium without gentamicin. Both the HA− phenotype and the presence of Tn4001mod in the crmA gene remained stable.

The number of viable mycoplasmas in a suspension was determined by plating serial dilutions on Hayflick medium containing 1% (wt/vol) agar, followed by incubation at 37°C. After 6 to 8 days, the number of CFU was counted using an SMZ-U stereomicroscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The presence of Tn4001mod in mycoplasma populations recovered from infected chickens was assessed by plating appropriate dilutions on solid medium without or with 100 μg of gentamicin per ml.

Experimental infection procedure.

The experimental infection procedure was performed as previously described by our group (6). Briefly, 150 Arbor Acres chickens, 21 days old and certified free of mycoplasmas, were divided into five groups of 30 birds each. Each group was placed in an aerosol chamber and inoculated with 10 ml of bacterial culture that was pulverized into fine aerosol particles of 7 to 10 μm and sprayed for 2 min into the chamber. The inoculum consisted of (i) 9.6 × 109 CFU of Rhigh, (ii) 10.5 × 109 CFU of Rlow, (iii) 9.7 × 109 CFU of mHAD3, (iv) 4 × 109 CFU of RCL2, or (v) medium alone without mycoplasmas. Infected birds were slaughtered at 9 days postinfection, and necropsy was performed for pathomorphological lesions of the thoracic and abdominal air sacs (AS) that were documented by a scoring system previously described (26), with a maximum theoretical score of 12 per bird.

During necropsy, swabs were collected from several body sites of the respiratory tract (trachea, lung, and left thoracic air sac) and of deeper inner organs (spleen, liver, kidney, and heart). Samples were directly transferred into culture medium and incubated at 37°C. Samples that showed a metabolic color change within 14 days were further processed, while the remaining samples were kept at 37°C for six additional days. All samples were stored at −80°C for further analysis after an aliquot from each grown culture was plated in two dilutions onto Hayflick agar plates. Mycoplasmas were identified as M. gallisepticum on randomly selected cultures by colony immunoblotting using anti-M. gallisepticum rabbit polyclonal serum at a 1:300 dilution (10) and by phenotyping of the mycoplasma populations.

Antibodies to CrmA.

M. gallisepticum clonal variant RCL1, which has been previously described and shown to express the CrmA product (15), was subjected to Triton X-114 fractionation as previously described (27). Proteins that partitioned into the insoluble pellet were resolved by 9% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The 116-kDa CrmA protein of interest was localized by negative staining using a zinc stain kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and the corresponding gel slice was excised, lyophilized, homogenized in an equal volume of 0.9% NaCl, and injected subcutaneously into three different locations of New Zealand White rabbits. Two booster injections of the protein in NaCl were given subcutaneously at monthly intervals so that each rabbit had received a total amount of protein corresponding to approximately 1.5 × 1011 CFU. Eleven days following the last inoculation, the rabbits were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (25 mg per kg of body weight) and Xalazine (3 mg per kg of body weight) and bled by cardiac puncture. The specificity and the working dilution of the rabbit antibodies directed against CrmA were assessed in Western blots using proteins extracted from CrmA-negative and CrmA-positive clones, namely, RCL2 and RCL1, respectively.

Colony immunoblotting and HA assay.

Colony immunoblotting was performed as described previously (28) with the antibodies and conditions described for Western blot analyses (see below). The hemadsorption (HA) assay was used to confirm that mycoplasmas reisolated from infected chickens had conserved the phenotype of the inoculum. To avoid artifacts due to removal of surface material through washing, colonies were first blotted on nitrocellulose discs (Protran BA 83; Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany), and the remaining colonies left on the agar plate were overlaid with a 0.5% (vol/vol) suspension of sheep erythrocytes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. After two gentle washes with PBS, the colonies were examined microscopically for hemadsorption.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Protein profile analyses of populations and clones used in this study were performed by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie blue staining and/or Western blotting using fractions obtained after Triton-X114 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) partitioning as described elsewhere (27). The membranes were probed either with rabbit anti-GapA antibodies (13) or with rabbit anti-CrmA antibodies diluted 1:8,000.

DNA manipulations.

Mycoplasma genomic DNA was extracted as previously described (29). Plasmid DNA was extracted using the PeqLab E.Z.N.A. plasmid miniprep kit II (PeqLab Biotechnologie GmbH, Erlangen, Germany). Restriction endonuclease (Promega GmbH, Madison, WI) digestion was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

PCR assays.

The presence of the transposon in mycoplasma populations recovered from infected birds was assessed by PCR. Along with the transposon-specific primers Tn1 and Tn2, the PCR mixture also contained the primers TufG15 and TufC26 to amplify a 210-bp fragment of the housekeeping tuf gene (30) as an internal control. All primers have been previously described (15). The reaction conditions were as follows: initial denaturation (3 min, 95°C); 30 cycles of denaturation (1 min, 94°C), annealing (1 min, 50°C), and extension (2 min, 72°C); and a final extension step (5 min, 72°C).

The integration of the transposon was confirmed by long-range PCR (LR-PCR) using the Expand Long Template PCR system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) to amplify the region located between the beginning of the crmA gene and the insertion sequence (IS) of Tn4001mod. Primers IS256rev and JF and LR-PCR conditions were applied as described elsewhere (15), with the exception that the annealing temperature was lowered to 48°C for all cycles.

The presence of the point mutation located at nucleotide 1393 of the RCL2 gapA gene (this position was defined based on data described by Papazisi et al. [13]) was assessed by performing a PCR with primers GapA4 and GapA5 (15) followed by digestion of the PCR product by MseI (NEB Inc.). The resulting fragments were resolved by electrophoresis in a 10% polyacrylamide gel as described elsewhere (15).

Statistical analysis.

The SISA software (Simple Interactive Statistical Analysis; Quantitative Skills Consultancy for Research and Statistics, Hilversum, The Netherlands) was used for statistical analysis. The numbers of infected birds, air sac lesion scores, and frequency of reisolations were analyzed by the Fisher exact test (n = 30). Both groups, i.e., birds infected with RCL2 or mHAD3, were compared with the control groups Rlow and Rhigh and with each other. P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Virulence of the two distinct HA− M. gallisepticum mutants.

To better understand the role of the two cytadhesins GapA and CrmA in M. gallisepticum virulence, host colonization, and systemic infection, two groups of chickens were infected by aerosol with the mutants RCL2 and mHAD3 (Fig. 1), while three control groups received either (i) sterile broth medium, (ii) the virulent parental strain Rlow, or (iii) the highly passaged strain Rhigh, which has lost its virulence properties and lacks both the GapA and CrmA products (6, 13, 16). When air sac (AS) lesions were scored in necropsied chickens, control groups behaved as expected (6): (i) no AS lesions were found in birds of the group inoculated with medium, (ii) 30 birds out of 30 in the Rlow-infected group displayed air sacculitis, with a total lesion score of 220, and (iii) only 3 out of 30 birds of the Rhigh-infected group presented mild AS lesions, with a total score of 4 (Table 1). Results obtained with the mHAD3-infected group revealed that only 8 out of 30 chickens displayed AS lesions, with a total score of 12. A closer examination revealed that among these, mycoplasma populations recovered from one bird exhibiting severe AS lesions (score of 5) had lost the transposon and reverted to the parental Rlow phenotype (see below). These data indicate that the number of birds presenting AS lesions did not significantly differ between groups infected with Rhigh and mHAD3 (Table 1). In contrast, more than half of the RCL2-infected chickens (19 out of 30) displayed air sac lesions, with a total score of 40. These values are significantly higher than those observed in groups inoculated with mHAD3 or Rhigh; however, they are also significantly lower than those obtained with the parental Rlow strain, suggesting that RCL2 displayed an attenuated virulence.

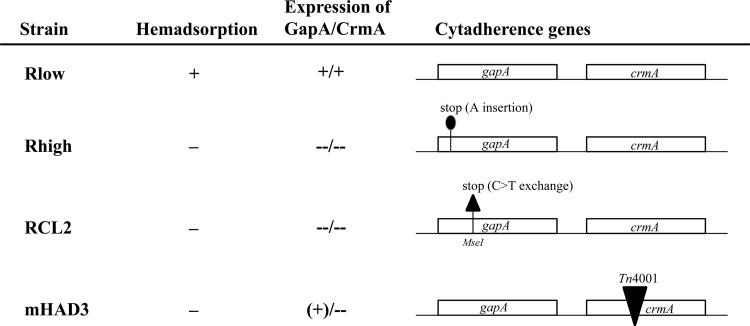

Fig 1.

Phenotypes of M. gallisepticum strains and mutants used as inocula in the experimental infection. Hemadsorption capacity, expression of GapA and CrmA, and the nature of the underlying mutations in HA− mutants Rhigh, RCL2, and mHAD3 are depicted. While Rhigh displays a frameshift mutation in gapA and mHAD3 a disruption of crmA by transposon insertion, RCL2 harbors a nonsense mutation in gapA which is highly reversible.

Table 1.

Numbers of chickens presenting air sacculitis and/or infected with M. gallisepticuma

| Infection group | No. of birds with AS lesions | AS lesion score |

No. of birds in which M. gallisepticum was recovered |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Per bird | RT | IO | Total | ||

| Medium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rlow | 30 | 220 | 7.33 | 30 | 28 | 30 |

| Rhigh | 3 | 4 | 1.33 | 26 | 7 | 26 |

| RCL2 | 19 L,H,M | 40 L,H,M | 2.1 | 30 M | 14 L,H,M | 30 M |

| mHAD3 | 8 L,C | 12 L,H,C | 1.5 L | 17 L,H,C | 5 L,C | 17 L,H,C |

Abbreviations: AS, air sac; RT, respiratory tract; IO, inner organs. The letters L, H, C, and M indicate values significantly different (P ≤ 0.05) from those obtained for birds infected with Rlow, Rhigh, RCL2, or mHAD3, respectively.

Host colonization abilities of the two distinct HA− M. gallisepticum mutants.

To investigate whether the two HA− M. gallisepticum mutants are able to colonize the chicken host, swab samples were collected at necropsy from the respiratory tract and from different inner organs. A total of 150 swabs from the trachea, left thoracic air sac, lung, liver, spleen, kidney, or heart were initially grown in broth. Aliquots were plated on solid medium when a metabolically derived color change could be observed. A large number of samples showed a color change within the first week of incubation, and samples were considered negative after no color change was observed for 14 days of incubation. M. gallisepticum was identified by colony immunoblotting using anti-M. gallisepticum rabbit polyclonal serum (10) and further confirmed during phenotyping of the recovered mycoplasmas (see below).

The frequency of reisolation of M. gallisepticum in each group is presented in Tables 1, 2, and 3, which show that (i) no mycoplasma was recovered from chickens inoculated with medium, (ii) Rhigh predominantly colonizes the upper respiratory tract, (iii) Rlow colonizes the respiratory tract and various inner organs, and (iv) the degree of colonization varies among birds of the same group (i.e., not all birds displayed mycoplasmas in all organs). Overall, the highest frequency of M. gallisepticum reisolation was observed in the group infected with Rlow, with 70% of positive samples (Table 2). In contrast, the mHAD3-infected group displayed the lowest frequency, 13.2%, a value representing less than half of that obtained with the Rhigh-infected group (29.7%). Finally, M. gallisepticum was reisolated in 43% of the samples collected from RCL2-infected birds. Therefore, mHAD3 and RCL2 differ significantly in their ability to colonize or survive in the host, although both variants are derived from Rlow and display a similar GapA- and CrmA-negative phenotype.

Table 2.

Frequency of reisolation of M. gallisepticum from the respiratory tract and from inner organs after 9 days of infection

| Inoculum | % of birds with M. gallisepticum-positive sampling froma: |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory tract |

Inner organs |

Total | ||||||||

| Trachea | Air sac | Lung | Total | Spleen | Liver | Heart | Kidney | Total | ||

| Rlow | 100 (23) | 90.0 (30) | 100 (29) | 96.3 | 23.3 (30) | 27.6 (29) | 60.0 (30) | 96.6 (29) | 51.7 | 70.0 |

| Rhigh | 88.5 (26) | 23.3 (30) | 70.0 (30) | 59.3 | 0 (27) | 0 (30) | 6.7 (30) | 24.1 (29) | 7.8 | 29.7 |

| RCL2 | 100 (25) | 53.3 (30) | 90.0 (30) | 80.0 | 3.5 (29) | 3.5 (29) | 20.7 (29) | 35.7 (28) | 15.7 | 43.0 |

| mHAD3 | 51.7 (29) | 6.7 (30) | 13.8 (29) | 23.9 | 0 (28) | 7.1 (28) | 3.3 (30) | 10.0 (30) | 5.2 | 13.2 |

| Medium | 0 (30) | 0 (29) | 0 (29) | 0 | 0 (30) | 0 (30) | 0 (30) | 0 (30) | 0 | 0 |

One sample per organ site was taken from each of the 30 birds per group. Because contaminated samples were withdrawn from calculation, numbers in parentheses represent the number of birds used for calculation.

Table 3.

Phenotypes of the mycoplasmas recovered after infection

| Infection group | No. of samples: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| M. gallisepticum positive | Analyzed for phenotype | Presenting phenotype of inoculum (%) | |

| Medium control | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rlow | 140 | 24 | 24 (100) |

| Rhigh | 60 | 29 | 27 (93) |

| RCL2 | 86 | 62 | 61 (98.4) |

| mHAD3 | 27 | 27 | 19 (70.4) |

Overall, mHAD3-infected birds displayed the lowest frequency of mycoplasma reisolation from the respiratory tract (23.9%) (Table 2) compared to the rates calculated for groups infected with RCL2 (80%) or even with Rhigh (59.3%). Most specifically, the frequency of reisolation from the lung was particularly low in the mHAD3 group with respect to that obtained from the trachea.

Finally, reisolation from the inner organs was lower in all groups than that from the respiratory tract, with Rlow presenting the highest rate and mHAD3 the lowest. This suggests that the ability of M. gallisepticum to colonize or persist within the respiratory tract might correlate with its dissemination throughout the body.

In vivo stability of the mHAD3 and RCL2 mutations.

The data described above suggested that RCL2 exhibits attenuated virulence properties compared to the parental strain Rlow, while mHAD3, which is derived from the same strain, is avirulent. This raised the question of whether the mutations underlying the mHAD3 and the RCL2 genotypes are stable, especially when considering the reversible nature of the gapA mutation in RCL2 in vitro.

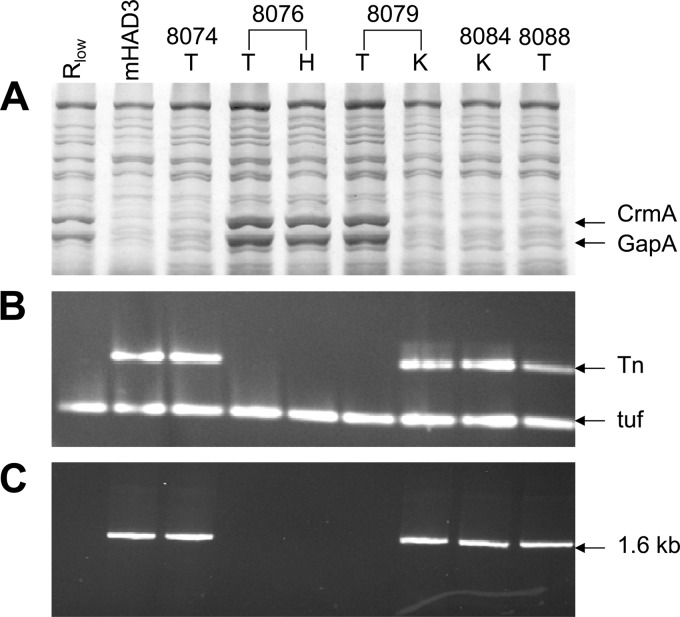

To address this question, the 27 mycoplasma-positive samples from the mHAD3-infected group were first monitored (i) for their resistance or sensitivity to gentamicin (Gmr/Gms) by plating appropriate dilutions on solid agar plates with and without gentamicin, (ii) for the detection of GapA and CrmA (GapA+/− CrmA+/−) in SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis, and (iii) for the presence of Tn4001mod and its location within the crmA gene (Tn+/−) by PCR using the two pairs of primers described in Materials and Methods. The results revealed that 8 out of 27 reisolates were gentamicin sensitive (Gms), did not contain the transposon, and produced both GapA and CrmA. Most particularly, all populations recovered from bird 8076, which exhibited the highest AS lesion score, expressed the GapA and CrmA products regardless of the origin of the sampling (trachea, air sac, lung, liver, and heart). This is illustrated in Fig. 2, which shows a perfect correlation between the expression of GapA and CrmA (Fig. 2A) and the absence of the transposon within the crmA gene (Fig. 2B and C) in populations recovered from the trachea (T) and the heart (H) of bird 8076. Interestingly, the same picture was obtained for isolates recovered from the tracheae of two birds from which mycoplasmas exhibiting the original mHAD3 features (Gmr, GapA− CrmA−, Tn+) also were reisolated from another body site. This is illustrated in Fig. 2 for the two samples recovered from the trachea (8079 T) and from the kidney (8079 K) of bird 8079, which represented the Rlow and the original mHAD3 features, respectively.

Fig 2.

Analyses of mycoplasmas recovered from mHAD3-infected chickens. (A) Total proteins of mycoplasma populations were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. (B) Total DNAs from the mycoplasma populations analyzed in panel A were subjected to a multiplex PCR assay, and the resulting products specific for the Tn4001 (Tn) and the housekeeping EfTu gene (tuf) were detected by ethidium bromide staining after agarose gel electrophoresis. (C) Total DNAs from mycoplasma populations (analyzed in panel A) were subjected to a long-range PCR assay using a forward primer located in the crmA gene and a reverse primer located in Tn4001 to amplify a 1.6-kb DNA which was detected by ethidium bromide staining after agarose gel electrophoresis. Mycoplasma populations were recovered from the tracheae (T), the kidneys (K), or the hearts (H) of mHAD3-infected chickens as described in Materials and Methods. Rlow and mHAD3 were used as controls. Numbers above the lanes correspond to the number that was assigned to each bird.

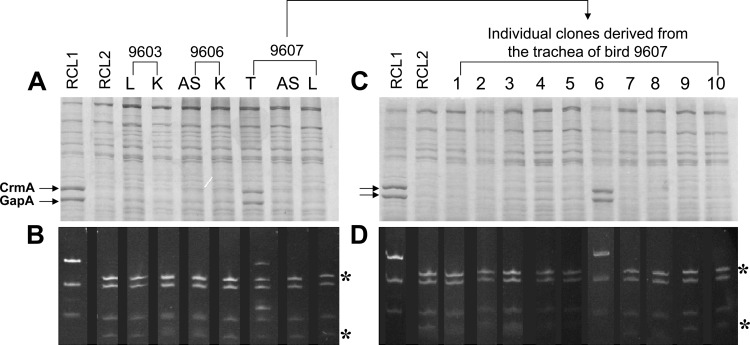

Similarly, we monitored 62 reisolates from the 86 samples (72%) which were positive for M. gallisepticum in birds infected with RCL2 (i) for the expression of GapA and CrmA and (ii) for the presence of the point mutation located at the beginning of the structural gapA gene by combining PCR with restriction analyses as previously described (15). This analysis revealed that 61 reisolates displayed molecular features identical to those of the RCL2 inoculum, as illustrated with reisolates from birds 9603 and 9606 (Fig. 3A and B).

Fig 3.

Analyses of mycoplasmas recovered from RCL2-infected chickens. (A and C) Total proteins of mycoplasma populations (A) or clones (C) were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. (B and D) Total DNAs from the mycoplasma populations (B) or clones (D) analyzed in panels A and C were subjected to a PCR assay to amplify the gapA region containing the RCL2 point mutation, and the resulting products were digested with MseI. Restriction fragments were detected by ethidium bromide staining after agarose gel electrophoresis. Mycoplasma populations were recovered from the left air sacs (AS), the tracheae (T), the lungs (L), or the kidneys (K) of RCL2-infected chickens as described in Materials and Methods. Numbers above the lanes correspond to the number that was assigned to each bird. RCL2 and RCL1, two isogenic variants derived from Rlow that differ by (i) their HA phenotype, (ii) the expression of GapA and CrmA, and (iii) a base substitution at the beginning of the gapA gene, were used as controls. Lanes 1 to 10 correspond to individual clones randomly selected from the mycoplasma population collected from the trachea of bird 9607. Asterisks indicate restriction DNA fragments that are detected only in HA− RCL2 variants lacking the GapA and CrmA products.

Interestingly, in one bird, namely, 9607, from which mycoplasmas were reisolated from the trachea, the air sac, and the lung, analysis of the tracheal sample (A673) revealed the presence of a mycoplasma population that was different from the RCL2 inoculum. Ten randomly picked colonies grown from tracheal sample A673 were screened for the RCL2 gapA mutation, and one out of 10 colonies was GapA/CrmA positive and did not contain the additional MseI restriction site of the mutated gapA gene. This indicates that sample A673 is composed of a mixed population, approximately 10% of which displayed the parental Rlow features. Although the in vitro on-and-off switching of gapA gene expression has been previously estimated to occur at a frequency of 5 × 10−2 to 2 × 10−4 per cell per generation, the emergence of revertants in sample A673 is likely to reflect an in vivo event rather than a contamination of the inoculum or of the samples, as this has not been observed for any other sample.

As controls, reisolates derived from Rlow and Rhigh were also analyzed. No difference in the GapA/CrmA status was observed between the Rlow inoculum and isolates recovered from Rlow-infected chickens. Two reisolates from the trachea and the air sac of one chicken infected with Rhigh showed expression of the GapA and CrmA products.

Overall, most phenotypic changes were recorded in M. gallisepticum populations recovered from birds infected with mHAD3, and it is noteworthy that almost 30% (8 out of 27) of the reisolates recovered from inner organs and the respiratory tract presented a phenotype different from that of the inoculum.

DISCUSSION

In past years, accumulated data regarding Mycoplasma gallisepticum infection in chickens have pointed toward GapA and CrmA as cytadhesins involved in colonization of the upper respiratory tract. In the current study, we revisited the part played by these two components in vivo and showed that they have a prominent role in systemic infection compared to the colonization of the respiratory tract.

Infections of chickens with two mutants displaying the same phenotype but containing distinctive mutations led to different outcomes in vivo. More specifically, the HA− mHAD3 mutant, in which the crmA gene has been disrupted (15), is unable to promote efficient colonization of the chicken host after aerosol inoculation. The results were particularly striking when considering that mHAD3 could be reisolated from the air sacs in only two birds, while the frequency of reisolation from the trachea was approximately seven times higher in the same group of infected birds. In one mHAD3-infected chicken (8076), the lesion score was surprisingly higher than for others of the same group. Detailed analysis of mycoplasmas reisolated from bird 8076 revealed that they display the wild-type phenotype and that they have lost the transposon Tn4001mod initially inserted in crmA. This contrasts with a previous study showing that insertion of Tn4001mod, which carries its own transposase, is stable in mHAD3 propagated in vitro without any antibiotic pressure. Nonetheless, the mHAD3 inoculum for the experimental infection was grown in the presence of gentamicin except for the very last step when propagating the culture from 1 to 10 ml. Most likely, the loss of the transposon in chicken 8076 has occurred over time, generating the emergence of a wild-type population which was further selected in vivo. A similar event was independently described by Mudahi-Orenstein and collaborators (23), who also reported the in vivo reversion of a M. gallisepticum mutant containing Tn4001 in the crmA gene. While the data presented in their study were focused on tracheal colonization, revertants were noted several days after intratracheal inoculation and the number of mycoplasma color-changing units (CCU) recovered over time from this body site was significantly lower than in birds infected with the wild-type strain. In our study, the behavior of mHAD3 with and without the transposon emphasizes the role played by genes of the gapA-crmA locus in virulence and in colonization of the respiratory tract and, further, in generating a systemic infection.

Aerosol inoculation of chickens with the spontaneous HA− RCL2 mutant, which contains a nonsense mutation in the gapA structural gene, revealed a different picture. Colonization by RCL2 of the upper and lower respiratory tracts was not significantly different from that by Rlow, although the frequency of reisolation of RCL2 from the air sacs was slightly lower than that from birds infected with the parent strain. Compared to Rlow, RCL2 displays an attenuated virulence and is impaired in dissemination to the inner organs. However, the behavior of RCL2 also significantly differs from those of mHAD3 and Rhigh, with a higher overall lesion score that seems to correlate with its ability to reach or to survive within the air sacs. As well, RCL2 performed better in reaching inner body sites, although it is significantly less efficient than the “wild-type,” parental Rlow strain. Overall, this suggests that RCL2 exhibits a pattern of infection that reflects an intermediate situation compared to those for Rlow and Rhigh or mHAD3. When comparing RCL2 to Rhigh, point mutations located in the gapA gene are distinct, but both affect the stability of the polycistronic mRNA that encodes GapA and CrmA and both result in the absence of these two products (13, 15). Besides their exact location, the only attribute that distinguishes these mutations is their frequency of reversion. In vitro, the point mutation in gapA of RCL2 was shown to spontaneously revert with a high frequency, resulting in on-and-off switching of the GapA expression, while that in Rhigh is reversible with a low frequency (15). Therefore, the higher virulence of the RCL2 inoculum as documented by the number of birds developing AS lesions was not unexpected if generated by a subpopulation having switched back to wild type. Surprisingly, 98.4% of the populations recovered from RCL2-infected birds still possessed the nonsense mutation. Only the reisolates from the tracheal sample of bird 9607 seemed to have lost the nonsense mutation, while mycoplasmas recovered from AS or lung samples of the same bird were not discernible from RCL2. When analyzing the RCL2 inoculum used for infection, no evidence was found that GapA/CrmA-positive mycoplasmas that have lost the gapA mutation existed in the inoculum. The same was so for the Rhigh inoculum; however, in two samples (out of 29) of Rhigh-infected birds, GapA/CrmA-positive mycoplasmas were found in the tracheal and AS samples of one bird. The very small amount of RCL2 revertants was unexpected. Apparently, switching on of the gapA and crmA expression via a reverse mutation did not spontaneously occur with a high frequency in vivo or, if occurring over a period of 9 days, did not provide an adequate advantage so that it was further selected and stable. While Rhigh is known to contain 29 additional mutations that could contribute to its avirulence, data obtained with RCL2 raised the question of the in vivo translation of gapA via ribosome slippage and/or of crmA, whose transcription could be initiated by a cryptic promoter located downstream of the gapA point mutation. Such a situation was recently reported for Mycoplasma agalactiae, in which a cryptic promoter was shown to be active in a mutant with a mutation affecting a group of genes required for survival (31). In this scenario, RCL2 would produce CrmA at a level that might differ slightly from that in Rlow, thus generating a pattern of infection that is intermediate between those of the wild-type, parent strain and its sibling, mHAD3, in which the disruptive mutation cannot be compensated for by the activity of the cryptic promoter.

A common trend observed between birds infected with either RCL2, mHAD3, or Rhigh is the reduced colonization of the air sacs compared to that in infection with Rlow. This observation suggests that GapA and CrmA might be particularly required for M. gallisepticum to reach, to adhere to, or to maintain itself in this particular body site. As well, there is a correlation between colonization of the air sacs and reisolation from the inner organs, suggesting that this site may be a portal for dissemination of the avian mycoplasma. As reported before, M. gallisepticum was detected inside and on the surface of red blood cells of experimentally infected chickens by PCR and confocal laser scanning microscopy (7). In consideration of the cell invasion capabilities of M. gallisepticum (7, 10), it is tempting to speculate that GapA and CrmA enable the mycoplasma to efficiently colonize the avian air sacs and the adjacent parabronchial system. Consisting of intermingling air and blood capillaries which are separated by extremely thin membranes ranging around 100 nm in thickness (32), this might be a suitable site for entering the avian bloodstream. We will address this topic in future experiments. The presence of mycoplasmas in body sites other than the mucosal surfaces has long been underestimated, although this occurrence could have important consequences for treatment and diagnosis. Understanding the mechanisms by which mycoplasmas are able to spread from the mucosal surface to deeper organs may provide new valuable information for the control of mycoplasmosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully thank J. Spergser and M. Steinbrecher for assistance in producing CrmA-specific antiserum. We are indebted to C. U. Zimmerman for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by grant P16538 from the Austrian Science Fund FWF (to C.C., R.R., and M.P.S.) and by grants 8633 (to P.M.) and 9137 (to R.R.) from the Jubilaeumsfonds of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank (OeNB).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 March 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Jordan FTW. 1979. Avian mycoplasmas, p 1–48 In Tully JG, Whitcomb RF. (ed), The mycoplasmas, vol II. Human and animal mycoplasmas. Academic Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levisohn S, Kleven SH. 2000. Avian mycoplasmosis (Mycoplasma gallisepticum). Rev. Sci. Technol. 19:425–442 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stipkovits L, Kempf I. 1996. Mycoplasmoses in poultry. Rev. Sci. Technol. 15:1495–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yoder HWJ. (ed). 1991. Mycoplasma gallisepticum infection. Iowa State University Press, Ames, IA [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davidson WR, Nettles VF, Couvillion CE, Yoder HW., Jr 1982. Infectious sinusitis in wild turkeys. Avian Dis. 26:402–405 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Much P, Winner F, Stipkovits L, Rosengarten R, Citti C. 2002. Mycoplasma gallisepticum: influence of cell invasiveness on the outcome of experimental infection in chickens. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 34:181–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vogl G, Plaickner A, Szathmary S, Stipkovits L, Rosengarten R, Szostak MP. 2008. Mycoplasma gallisepticum invades chicken erythrocytes during infection. Infect. Immun. 76:71–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Citti C, Browning GF, Rosengarten R. 2005. Phenotypic diversity and cell invasion in host subversion by pathogenic mycoplasmas, p 439–483 In Blanchard A, Browning GF. (ed), Mycoplasmas: molecular biology, pathogenicity and strategies for control. Horizon Bioscience, Wymondham, Norfolk, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 9. Markham PF, Glew MD, Browning GF, Whithear KG, Walker ID. 1998. Expression of two members of the PmgA gene family of Mycoplasma gallisepticum oscillates and is influenced by PmgA-specific antibodies. Infect. Immun. 66:2845–2853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Winner F, Rosengarten R, Citti C. 2000. In vitro cell invasion of Mycoplasma gallisepticum. Infect. Immun. 68:4238–4244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goh MS, Gorton TS, Forsyth MH, Troy KE, Geary SJ. 1998. Molecular and biochemical analysis of a 105 kda Mycoplasma gallisepticum cytadhesin (GapA). Microbiology 144:2971–2978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keeler CL, Jr, Hnatow LL, Whetzel PL, Dohms JE. 1996. Cloning and characterization of a putative cytadhesin gene (mgc1) from Mycoplasma gallisepticum. Infect. Immun. 64:1541–1547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Papazisi L, Troy KE, Gorton TS, Liao X, Geary SJ. 2000. Analysis of cytadherence-deficient, GapA-negative Mycoplasma gallisepticum strain r. Infect. Immun. 68:6643–6649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yoshida S, Fujisawa A, Tsuzaki Y, Saitoh S. 2000. Identification and expression of a Mycoplasma gallisepticum surface antigen recognized by a monoclonal antibody capable of inhibiting both growth and metabolism. Infect. Immun. 68:3186–3192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Winner F, Markova I, Much P, Lugmair A, Siebert-Gulle K, Vogl G, Rosengarten R, Citti C. 2003. Phenotypic switching in Mycoplasma gallisepticum hemadsorption is governed by a high-frequency, reversible point mutation. Infect. Immun. 71:1265–1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Papazisi L, Frasca S, Jr, Gladd M, Liao X, Yogev D, Geary SJ. 2002. GapA and CrmA coexpression is essential for Mycoplasma gallisepticum cytadherence and virulence. Infect. Immun. 70:6839–6845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Szczepanek SM, Tulman ER, Gorton TS, Liao X, Lu Z, Zinski J, Aziz F, Frasca S, Jr, Kutish GF, Geary SJ. 2010. Comparative genomic analyses of attenuated strains of Mycoplasma gallisepticum. Infect. Immun. 78:1760–1771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wise KS. 1993. Adaptive surface variation in mycoplasmas. Trends Microbiol. 1:59–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yogev D, Browning GF, Wise KS. 2002. Genetic mechanisms of surface variation, p 417–443 In Razin S, Herrmann R. (ed), Molecular biology and pathogenicity of mycoplasmas. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 20. Citti C, Nouvel Baranowski L-XE. 2010. Phase and antigenic variation in mycoplasmas. Future Microbiol. 5:1073–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Glew MD, Papazisi L, Poumarat F, Bergonier D, Rosengarten R, Citti C. 2000. Characterization of a multigene family undergoing high-frequency DNA rearrangements and coding for abundant variable surface proteins in Mycoplasma agalactiae. Infect. Immun. 68:4539–4548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gumulak-Smith J, Teachman A, Tu AH, Simecka JW, Lindsey JR, Dybvig K. 2001. Variations in the surface proteins and restriction enzyme systems of Mycoplasma pulmonis in the respiratory tract of infected rats. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1037–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mudahi-Orenstein S, Levisohn S, Geary SJ, Yogev D. 2003. Cytadherence-deficient mutants of Mycoplasma gallisepticum generated by transposon mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 71:3812–3820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin MY, Kleven SH. 1984. Evaluation of attenuated strains of Mycoplasma gallisepticum as vaccines in young chickens. Avian Dis. 28:88–99 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wise KS, Watson RK. 1983. Mycoplasma hyorhinis Gdl surface protein antigen p120 defined by monoclonal antibody. Infect. Immun. 41:1332–1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Czifra G, Sundquist BG, Hellman U, Stipkovits L. 2000. Protective effect of two Mycoplasma gallisepticum protein fractions affinity purified with monoclonal antibodies. Avian Pathol. 29:343–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wise KS, Kim MF, Watson-McKown R. 1995. Variant membrane proteins, p 227–241 In Razin S, Tully JG. (ed), Molecular and diagnostic procedures in mycoplasmology. Academic Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 28. Citti C, Wise KS. 1995. Mycoplasma hyorhinis vlp gene transcription: critical role in phase variation and expression of surface lipoproteins. Mol. Microbiol. 18:649–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Citti C, Watson-McKown R, Droesse M, Wise KS. 2000. Gene families encoding phase- and size-variable surface lipoproteins of Mycoplasma hyorhinis. J. Bacteriol. 182:1356–1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Glew MD, Markham PF, Browning GF, Walker ID. 1995. Expression studies on four members of the pmgA multigene family in Mycoplasma gallisepticum s6. Microbiology 141:3005–3014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Skapski A, Hygonenq MC, Sagne E, Guiral S, Citti C, Baranowski E. 2011. Genome-scale analysis of Mycoplasma agalactiae loci involved in interaction with host cells. PLoS One 6:e25291 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maina JN, West JB. 2005. Thin and strong! The bioengineering dilemma in the structural and functional design of the blood-gas barrier. Physiol. Rev. 85:811–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]