Abstract

To determine the ability of the major outer membrane protein (MOMP) to elicit cross-serovar protection, groups of mice were immunized by the intramuscular (i.m.) and subcutaneous (s.c.) routes with recombinant MOMP (rMOMP) from Chlamydia trachomatis serovars D (UW-3/Cx), E (Bour), or F (IC-Cal-3) or Chlamydia muridarum strain Nigg II using CpG-1826 and Montanide ISA 720 VG as adjuvants. Negative-control groups were immunized i.m. and s.c. with Neisseria gonorrhoeae recombinant porin B (Ng-rPorB) or i.n. with Eagle's minimal essential medium (MEM-0). Following vaccination, the mice developed antibodies not only against the homologous serovar but also against heterologous serovars. The rMOMP-vaccinated animals also mounted cell-mediated immune responses as assessed by a lymphoproliferative assay. Four weeks after the last immunization, mice were challenged i.n. with 104 inclusion-forming units (IFU) of C. muridarum. The mice were weighed for 10 days and euthanized, and the number of IFU in their lungs was determined. At 10 days postinfection (p.i.), mice immunized with the rMOMP of C. muridarum or C. trachomatis D, E, or F had lost 4%, 6%, 8%, and 8% of their initial body weight, respectively, significantly different from the negative-control groups (Ng-rPorB, 13%; MEM-0, 19%; P < 0.05). The median number of IFU recovered from the lungs of mice immunized with C. muridarum rMOMP was 0.13 × 106. The median number of IFU recovered from mice immunized with rMOMP from serovars D, E, and F were 0.38 × 106, 7.56 × 106, and 11.94 × 106 IFU, respectively. All the rMOMP-immunized animals had significantly less IFU than the Ng-rPorB (40 × 106)- or MEM-0 (70 × 106)-immunized mice (P < 0.05). In conclusion, vaccination with rMOMP can elicit protection against homologous and heterologous Chlamydia serovars.

INTRODUCTION

Chlamydia trachomatis is the leading cause of bacterial sexually transmitted infections and preventable blindness worldwide and can also produce gastrointestinal and respiratory infections (1–4). Genital infections particularly affect young, sexually active individuals of both genders (1, 3, 5, 6). Newborns become infected in the birth canal and contract ocular and respiratory infections (1, 6, 7). Adult immunocompromised individuals can also suffer from respiratory infections (8, 9). Antibiotic therapy is available, but due to the high percentage of asymptomatic patients, and delayed or inappropriate treatment, persistent infections with long-term sequelae can develop, including abdominal pain, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and blindness (3, 6, 10, 11). Countries that have established screening programs for genital infections, followed by antibiotic therapy, have observed an increase in the prevalence of infection (12, 13). This increase is thought to be due to a block in the development of natural immunity as a result of the antibiotic therapy (12). Furthermore, C. trachomatis infections facilitate HIV transmission and favor the development of human papillomavirus (HPV)-induced neoplasia (14, 15). Therefore, there is an urgent need for a vaccine.

Based on protection experiments in mice and immunofluorescence tests, a total of 15 different human C. trachomatis serovars have been identified (16, 17). In addition, Chlamydia muridarum, previously called Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis (MoPn), was isolated from mice inoculated with human respiratory specimens (18, 19). In the 1960s, vaccines formulated with live and whole inactivated Chlamydia were tested in humans and in nonhuman primates to protect against trachoma (1, 11, 20–23). Several vaccine protocols induced protection, although it appeared to be serovar, or subgroup, specific (1, 11). In addition, upon reexposure to this pathogen, some of the vaccinated individuals developed a hypersensitivity reaction (1, 11, 21–26). Therefore, the need for a subunit vaccine was considered. The C. trachomatis major outer membrane protein (MOMP) belongs to a family of proteins found in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria whose monomers have a molecular mass of ∼40 kDa and the homotrimers function as porins (27, 28). DNA sequencing of the C. trachomatis MOMP identified four variable domains (VD) that are unique to each serovar and antigenically dominant and, therefore, most likely account for the serovar specificity observed in the vaccination trials to protect against trachoma (29–31).

Here, to test the ability of recombinant MOMP (rMOMP) to elicit protection against the homologous and heterologous serovars, we immunized mice with the chlamydial rMOMP from the C. trachomatis D, E, and F serovars and the C. muridarum isolate. Cross-reactive humoral and cell-mediated immune responses were obtained in the vaccinated animals. Immunized mice were challenged in the nares with C. muridarum elementary bodies (Cm-EB), and protection was determined based on the loss of body weight, weight of the lungs, and number of inclusion-forming units (IFU) recovered from the lungs. The most robust protection was observed in the mice immunized with the C. muridarum rMOMP. In addition, significant protection against C. muridarum was also obtained in the mice immunized with the rMOMP preparations from the three human C. trachomatis serovars, D, E, and F. Thus, vaccination with rMOMP can induce homologous and heterologous protection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Stocks of Chlamydia.

The C. muridarum (strain Nigg II) and the C. trachomatis D (UW-3/Cx), C. trachomatis E (Bour), and C. trachomatis F (IC-Cal-3) serovars were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA) and were grown in McCoy and HeLa-229 cells, respectively. Elementary bodies (EB) were purified as described and stored in SPG (0.2 M sucrose, 20 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.2], and 5 mM glutamic acid) (32).

Purification and preparation of recombinant proteins.

The cloning, expression, and purification of the mature rMOMP from C. muridarum (Cm-rMOMP), C. trachomatis D (D-rMOMP), C. trachomatis E (E-rMOMP), and C. trachomatis F (F-rMOMP) were performed as described elsewhere (33). The N. gonorrhoeae strain FA1090 from the ATCC was grown on GC agar plates, and the porB gene (36 kDa; 330 amino acids [aa]) without the leading sequence (GenBank identifier AAW90430) was amplified by PCR, cloned, and expressed, and the protein was purified as described (Ng-rPorB) (33). The recombinant proteins were dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) with 0.05% Anzergent 3-14 (Z3-14; Anatrace, Maumee, OH) before immunization. The purity and the apparent molecular weight (MW) of all the recombinant proteins were evaluated on 10% tricine-SDS-PAGE (34). By the limulus amebocyte assay (BioWhittaker, Inc., Walkersville, MD), the recombinant preparations had less than 0.05 EU of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/mg of protein (33).

Immunization and challenge of mice.

Three-week-old female BALB/c (H-2d) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). The animals were vaccinated with rMOMP or the Ng-rPorB preparations by the intramuscular (i.m.) and the subcutaneous (s.c.) (10 μg protein/mouse/immunization) routes. CpG-1826 (5′-TCCATGACGTTCCTGACGTT-3′; 10 μg/mouse/dose; Coley Pharmaceutical Group, Ontario, Canada) and Montanide ISA 720 VG (Seppic Inc., Fairfield, NJ; at a 30:70 volume ratio of protein plus CpG to Montanide) were used as adjuvants (33). The mice were boosted two times at 2-week intervals with the same vaccine formulation. A negative-control group of mice was inoculated once intranasally (i.n.) with minimum essential medium (MEM-0) at the time of the first immunization. Positive-control mice were immunized i.n. once with 1 × 104 IFU of C. muridarum, at the time the other groups received the first immunization (33). Each group included 8 to 10 mice, and all the experiments were repeated.

Four weeks after the last immunization, all BALB/c mice were anesthetized and then challenged i.n. with 104 IFU of C. muridarum in 20 μl of MEM-0 (35). Body weight was assessed daily postchallenge (p.c.) for each individual mouse. On day 10 p.c., the lungs were harvested, weighed, and homogenized in SPG. Serial 10-fold dilutions of the lungs were inoculated onto HeLa cells, and the Chlamydia inclusions were stained with a pool of monoclonal antibodies (MAb) as described elsewhere (35). All experiments were repeated twice. The University of California, Irvine, Animal Care and Use Committee approved the animal protocols.

Immunological assays.

Blood was collected from the periorbital plexus of all the animals and stored frozen. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to detect Chlamydia-specific antibodies (35). Cm-EB at 10 μg/ml concentration were coated in a flat-bottom 96-well plate and incubated at 4°C overnight. Goat IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL), diluted 1:10,000 for IgG and 1:1,000 for the two isotypes, were used to determine the subclass or isotype-specific antibodies. ABTS [2,2′-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonate)] (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used as the substrate, and the plates were scanned in an ELISA plate reader at 405 nm (Labsystems Multiskan, Helsinki, Finland).

To determine antibody titers to the Cm-rMOMP, D-rMOMP, E-rMOMP, and F-rMOMP, the ELISA plates were coated with the corresponding protein (1 μg/ml; 100 μl/well of a 96-well plate) and incubated with 2-fold serial dilutions of sera from immunized animals. A secondary goat anti-mouse total IgG antibody was added, and the reaction was detected as described above.

To characterize B-cell-specific linear epitopes, overlapping 25-mers representing the entire length of the mature Cm-MOMP amino acid sequence were chemically synthesized (SynBioSci Corp., Livermore, CA) (36). The peptides (10 μg/ml; 100 μl/well of a 96-well plate) were adsorbed onto high-binding-affinity ELISA plates, and the serum antibody binding was determined in triplicate as described above using a 1:100 dilution of total anti-mouse IgG (34). Peptide 25 (p25) overlaps the N and C termini of the Cm-MOMP.

Western blottings were performed using nitrocellulose membranes as previously described (35). Briefly, tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was carried out for Cm-rMOMP (34). The protein was loaded on a 7.5-cm-wide slab gel and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, followed by blocking nonspecific binding sites with bovine lacto transfer technique optimizer (BLOTTO; 5% [wt/vol] nonfat dry milk, 2 mM CaCl2, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]). Serum samples were diluted and were used to probe the membrane strips by incubating them at 4°C overnight (35, 37). Detection of antibody binding was performed with the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody developed with 0.01% hydrogen peroxide and 4-chloro-1-naphthol (38).

For the in vitro neutralization assay, the method described by Peterson et al. (39) was followed. In brief, duplicate sets of 2-fold serial dilution of serum samples were made with 5% guinea pig serum in Ca+2- and Mg+2-free PBS. The serum was incubated with 1 × 104 IFU of C. muridarum for 45 min at 37°C. The mixture was inoculated into HeLa-229 monolayers grown in 15- by 45-mm glass shell vials and centrifuged for an hour at 1,000 × g. Media with cycloheximide at 1 μg/ml was added to the cells and incubated for 30 h. The monolayers were then fixed with methanol and the chlamydial inclusions stained with a pool of Chlamydia-specific monoclonal antibodies. The number of IFU was counted, and neutralization was defined as greater than, or equal to, a 50% decrease in the number of IFU, compared to the control sera from the animals immunized with Ng-rPorB.

The lymphoproliferative assay (LPA) was performed as described previously with the following modifications (35, 37). Splenocytes were collected from two spleens per group, and T lymphocytes were separated using a nylon wool column. Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) were preprepared by irradiating (3,000 rads, 137Cs) syngeneic unseparated splenocytes, and 200 μl was incubated in round-bottom 96-well plates (Costar, Corning, Inc.) at 37°C for 2 h with Cm-EB at a 1:5 ratio. T cells were added to APCs at a ratio of 1:1. The tissue culture medium was prepared by adding 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2% l-glutamine, 5 μg/ml gentamicin, and 50 μM 2β-mercaptoethanol to RPMI 1640 (RPMI-FBS; Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA). Concanavalin A (5 μg/ml) served as a positive stimulant and tissue culture medium (RPMI-FBS) as a negative antigen control. Supernatants from three wells were collected 48 h postincubation and stored at −70°C for cytokine analysis. At the end of 96 h of incubation, 1.0 μCi of thymidine [methyl-3H] (47 Ci/mmol; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) in 25 μl of culture medium was added to the rest of the wells. After an additional 18 h of incubation, the cells were washed and collected on filter paper (Filter MAT, Skatron Instruments, USA), and scintillation fluid was added. A scintillation counter (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA) was used to measure the incorporation of [3H] in the samples tested.

Levels of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and interleukin 4 (IL-4) were determined using commercial kits (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) in the supernatants from the stimulated splenic T cells (33).

Statistics.

The two-tailed unpaired Student t test, the one-way repeated analysis of variance (ANOVA) Holm-Sidak method, and the Mann-Whitney rank test were employed to determine the significance of the differences between groups. Differences were considered significant for P values of <0.05.

RESULTS

Humoral immune responses in serum.

BALB/c mice were immunized i.m. and s.c. with D-rMOMP, E-rMOMP, F-rMOMP, and Cm-rMOMP, using CpG-1826 and Montanide ISA 720 as adjuvants. As a positive control, mice were immunized i.n. with live Cm-EB, and as negative controls one group of animals received only MEM-0 i.n. and another Ng-rPorB by the i.m. and s.c. routes with the same adjuvants as those vaccinated with rMOMP. As shown in Table 1, following immunization, the highest total IgG geometric mean titer (GMT; 102,400) against Cm-EB was observed in the Cm-rMOMP-immunized group. The total IgG GMTs determined in the mice immunized with D-rMOMP, E-rMOMP, and F-rMOMP were 2,016, 4,032, and 1,270, respectively. The IgG GMT in the sera from the positive control inoculated i.n. with Cm-EB was 16,127. The negative-control groups had no chlamydial-specific IgG antibodies.

Table 1.

Anti-C. muridarum EB antibody titers in serum from the day before the i.n. challenge

| Vaccine | Geometric mean of serum antibody titers (range) |

Serum-neutralizing titer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | IgG1 | IgG2a | ||

| D-rMOMP | 2,016 (1,600–3,200) | 400 (400–400) | 1,270 (800–1,600) | 50 |

| E-rMOMP | 4,032 (3,200–6,400) | 800 (200–1600) | 3,200 (1,600–6,400) | 250 |

| F-rMOMP | 1,270 (400–3,200) | 400 (200–800) | 2,016 (1,600–3,200) | 50 |

| Cm-rMOMP | 102,400a (51,200–409,600) | 1,008 (800–1,600) | 81,275a (51,200–204,800) | 1,250 |

| Ng-rPorB | <100 | <100 | <100 | <50 |

| Cm-EB | 16,127 (12,800–25,600) | 1,270 (800–1,600) | 25,600 (25,600–25,600) | 1,250 |

| MEM-0 | <100 | <100 | <100 | <50 |

P < 0.05 by Student's t test compared to D-rMOMP-, E-rMOMP-, or F-rMOMP-immunized groups.

To determine if the immunizations induced Th1 or Th2 responses, the levels of IgG1 and IgG2a were measured (Table 1). In the groups of mice immunized with D-rMOMP, E-rMOMP, F-rMOMP, or Cm-rMOMP, the ratios of IgG2a to IgG1 were 3:1, 4:1, 5:1, and 80:1, respectively, indicating a Th1-biased response. This ratio was 20:1 for the positive-control group, immunized with Cm-EB.

To assess the level of antibody cross-reactivity to the rMOMP, microtiter plates were coated with the rMOMP from the human C. trachomatis serovars D, E, and F and the C. muridarum isolate. Sera from the mice immunized with these proteins, plus the negative-control group immunized with Ng-rPorB, were used to probe those plates using an ELISA. As shown in Table 2, overall the highest total IgG GMT was obtained when sera from rMOMP-immunized mice were used to react with the homologous rMOMP. For example, the IgG GMT against the Cm-rMOMP in the sera from the mice immunized with the homologous rMOMP was 620,838, while the titers against the D-, E-, and F-rMOMP were 22,286, 19,401 and 19,401, respectively. Cross-reactive antibodies were detected for all the heterologous combinations. As expected, there was more cross-reactivity among the human serovars D and E than between these two serovars and F.

Table 2.

Serovar-specific antibody titers in serum from the day before the i.n. challenge

| Vaccine | Geometric mean of serum total IgG antibody titers (range) probed against: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-rMOMP | E-rMOMP | F-rMOMP | Cm-rMOMP | |

| D-rMOMP | 356,578a,b (102,400–819,200) | 270,235b (102,400–819,200) | 67,559a,b (25,600–204,800) | 178,289 (102,400–409,600) |

| E-rMOMP | 204,800b (51,200–409,600) | 178,289b (51,200–409,600) | 44,572 (12,800–102,400) | 117,627 (51,200–409,600) |

| F-rMOMP | 67,559 (25,600–204,800) | 77,605b (25,600–204,800) | 270,235b,c,d (204,800–409,600) | 77,605 (25,600–204,800) |

| Cm-rMOMP | 22,286 (12,800–25,600) | 19,401 (12,800–25,600) | 19,401 (12,800–25,600) | 620,838a,c,d (409,600–1,638,400) |

| Ng-rPorB | <100 (<100–<100) | <100 (<100–<100) | <100 (<100–<100) | <100 (<100–<100) |

| Cm-EB | 400 (100–1,600) | 400 (100–1,600) | 384 (100–3,200) | 3,667 (1,600–6,400) |

P < 0.05 by Student's t test compared to the F-rMOMP-immunized group.

P < 0.05 by Student's t test compared to the Cm-rMOMP-immunized group.

P < 0.05 by Student's t test compared to the D-rMOMP-immunized group.

P < 0.05 by Student's t test compared to the E-rMOMP-immunized group.

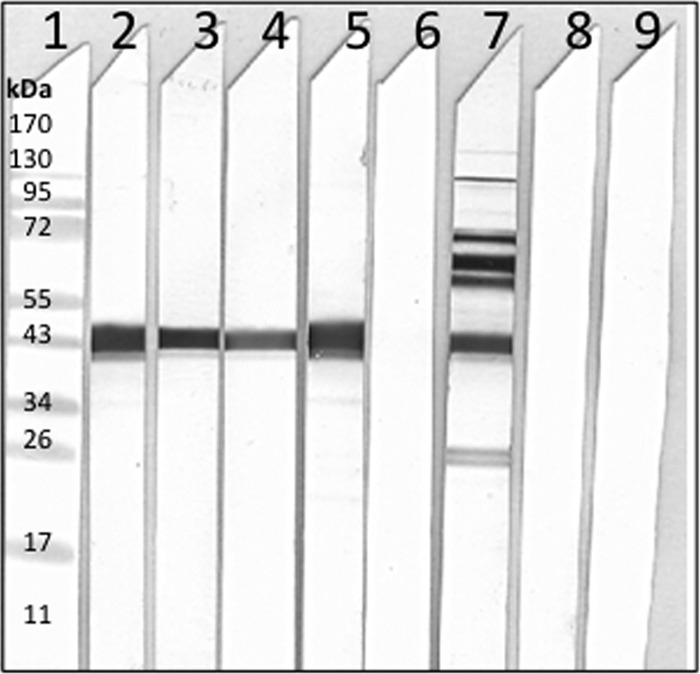

Immunoblot analyses of serum samples, using Cm-rMOMP as the antigen, are shown in Fig. 1. The mice immunized with D-rMOMP, E-rMOMP, F-rMOMP, Cm-rMOMP, or Cm-EB had antibodies against the Cm-rMOMP. No antibodies against Cm-rMOMP were detected in the serum of mice inoculated with Ng-rPorB or MEM-0.

Fig 1.

Western blot analyses of serum samples collected the day before the i.n. challenge with Cm-EB. Lane 1, MW standards; Cm-rMOMP protein probed with sera from mice immunized with D-rMOMP (lane 2), E-rMOMP (lane 3), F-rMOMP (lane 4), Cm-rMOMP (lane 5), Ng-rPorB (lane 6), Cm-EB (lane 7), MEM-0 (lane 8), preimmunization sera (lane 9).

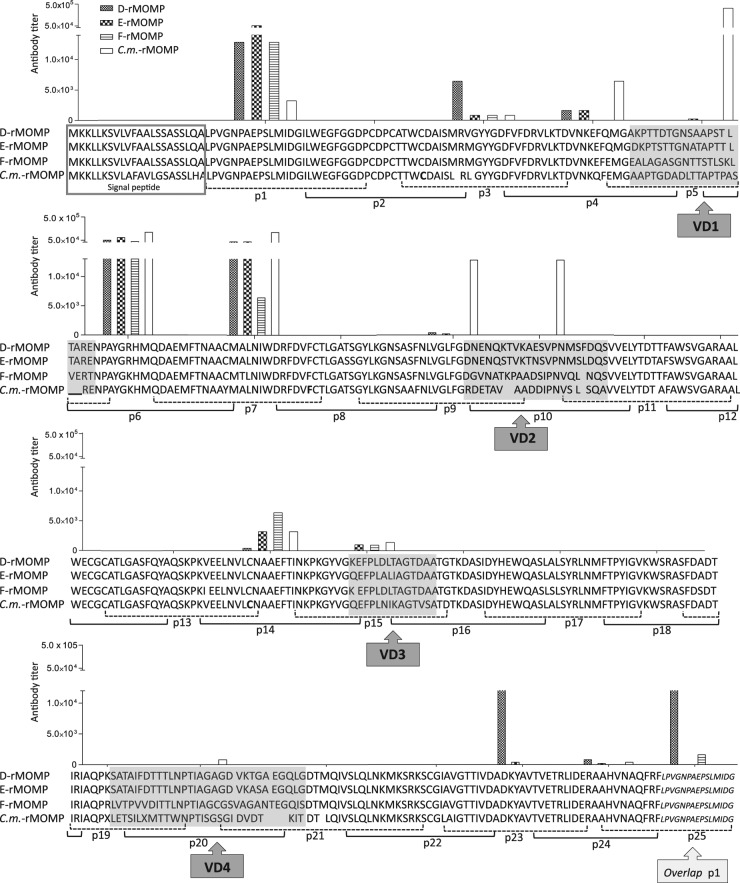

To determine the B-cell epitopes recognized by antibodies following immunization with the four MOMP preparations, ELISA plates coated with Cm-MOMP 25-mer overlapping peptides were probed with serum samples collected the day before the i.n. challenge. Only sera from the Cm-rMOMP-immunized group recognized B-cell epitopes in Cm-MOMP VD (p5 corresponding to VD1, p9 and p10 corresponding to VD2, and p20 corresponding to VD4) (Fig. 2). Sera from the D-rMOMP-, E-rMOMP-, F-rMOMP-, and Cm-rMOMP-immunized animals exhibited equivalent reactivity to the constant domains (CD) corresponding to p1, p6, and p7. Weaker and more uneven responses were detected with peptides p3, p4, p14, p15, and p23.

Fig 2.

Serum antibody binding to synthetic C. muridarum peptides. Serum samples from mice immunized with Cm-rMOMP, D-rMOMP, E-rMOMP, and F-rMOMP were collected the day before the i.n. challenge, and their reactivities against synthetic peptides corresponding to the Cm-MOMP were determined by an ELISA.

The highest in vitro neutralizing titer to Cm-EB was observed in the mice immunized with the Cm-rMOMP (1,250) (Table 1). Lower titers of neutralizing antibodies were found in sera from mice vaccinated with D-rMOMP (50), E-rMOMP (250), and F-rMOMP (50). The neutralizing titer in the sera from positive-control mice immunized with Cm-EB was 1,250. Sera from animals immunized with Ng-rPorB were used as negative controls.

T-cell responses of immunized mice.

To determine the Chlamydia-specific T-cell response elicited by vaccination, mice were euthanized and their spleens were collected the day before the i.n. challenge. T cells were purified and stimulated with Cm-EB, with MEM-0 as a negative control and ConA as a positive control. T-cell proliferation was determined by the incorporation of [3H]thymidine. As shown in Table 3, significant proliferative T-cell responses with Cm-EB were observed in the groups of animals vaccinated with D-rMOMP, F-rMOMP, or Cm-rMOMP, compared to the control groups immunized with Ng-rPorB or MEM-0 (P < 0.05). For E-rMOMP, significant results were obtained only compared with MEM-0. The stimulation indexes (SI) for the mice immunized with D-rMOMP, E-rMOMP, F-rMOMP, or Cm-rMOMP were 22, 14, 30, and 16, respectively. The positive-control group immunized i.n. with Cm-EB showed a robust T-cell response (SI = 189).

Table 3.

T-cell proliferative responses to Cm-EB of immunized mice from the day before the i.n. challenge with C. muridaruma

| Vaccine | T-cell proliferative response (×103 CPM ± 1 SE) to: |

In vitro cytokine production (Cm-EBb) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cm-EBb | ConAc | Medium | SI | IFN-γ (pg/ml) × 103 | IL-4 (pg/ml) | |

| D-rMOMP | 3.15 ± 0.24d,e | 14.40 ± 1.25 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 22 | 5.04 ± 0.28h | 25.01 ± 14.80 |

| E-rMOMP | 1.66 ± 0.39d | 21.87 ± 1.24 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 14 | 3.15 ± 1.12 | 20.65 ± 18.05 |

| F-rMOMP | 3.45 ± 0.30d,e | 17.38 ± 0.97 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 30 | 1.35 ± 0.86 | 10.28 ± 14.74 |

| Cm-rMOMP | 2.20 ± 0.12d,e | 22.22 ± 1.21 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 16 | 7.91 ± 0.60f,g,h | 22.02 ± 13.32 |

| Ng-rPorB | 1.02 ± 0.13 | 35.33 ± 3.53 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 4 | 1.56 ± 1.9 | 2.19 ± 6.02 |

| Cm-EB | 14.04 ± 1.39 | 24.66 ± 2.4 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 189 | 148.89 ± 4.13 | 20.86 ± 15.66 |

| MEM-0 | 0.65 ± 0.11 | 16.05 ± 2.66 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 6 | 2.21 ± 1.7 | 3.27 ± 6.60 |

Values are indicated as means ± 1 SE of triplicate cultures. SI, stimulation index.

Cm-EB was added at a 1:1 ratio to APC cells.

Concavalin A was added at a concentration of 5 μg/ml.

P < 0.05 by Student's t test compared to the MEM-0-immunized group.

P < 0.05 by Student's t test compared to the Ng-rPorB-immunized group.

P < 0.05 by Student's t test compared to the D-rMOMP-immunized group.

P < 0.05 by Student's t test compared to the E-rMOMP-immunized group.

P < 0.05 by Student's t test compared to the F-rMOMP-immunized group.

Levels of IFN-γ and IL-4 were determined in the supernatants from splenocytes stimulated with Cm-EB (Table 3). The highest level of IFN-γ was found in the animals immunized with Cm-rMOMP (7.91 ng/ml) and D-rMOMP (5.04 ng/ml). IFN-γ levels were high in the C. muridarum-immunized group (148.89 ng/ml). The levels of IL-4 were low, and no statistically significant differences were observed in the rMOMP-vaccinated animals compared with the control groups (Table 3).

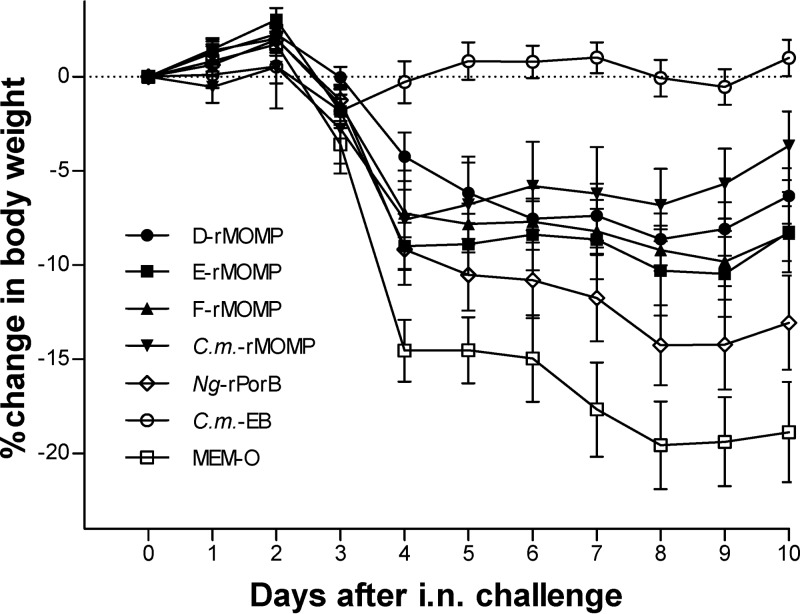

Body weight changes following the intranasal challenge.

The body weight of the mice was determined daily following the i.n. challenge and was used as an indication of the systemic effect of the chlamydial infection. As shown in Fig. 3, the positive-control mice immunized with Cm-EB lost weight immediately following the challenge, recovered their initial body weight by day 3, and maintained their weight for the rest of the experiment. In contrast, the negative-control groups inoculated with Ng-rPorB and MEM-0 continuously lost body weight and by day 10 p.c. had lost 13% and 19%, respectively, of their initial body weight. By day 4 p.c., the animals vaccinated with the rMOMPs from different serovars had lost between 5 to 9% of their initial body weight but recovered or did not lose any more weight by day 10 p.c. The Ng-rPorB-immunized group is statistically significantly different (P < 0.05) from the D-rMOMP-, F-rMOMP-, and Cm-rMOMP-immunized groups but not from the E-rMOMP group. The body weight of the D-rMOMP, E-rMOMP, F-rMOMP, and Cm-rMOMP groups are not statistically significantly different from each other, by repeated-measure ANOVA, over the course of the 10-day follow-up, but significantly different from the MEM-0 and Cm-EB control groups (P < 0.05).

Fig 3.

Percentage change in mean body weight of mice following the i.n. challenge with C. muridarum. Daily percentage change in mean body weight following the i.n. C. muridarum challenge. Errors bars represent standard errors (SE).

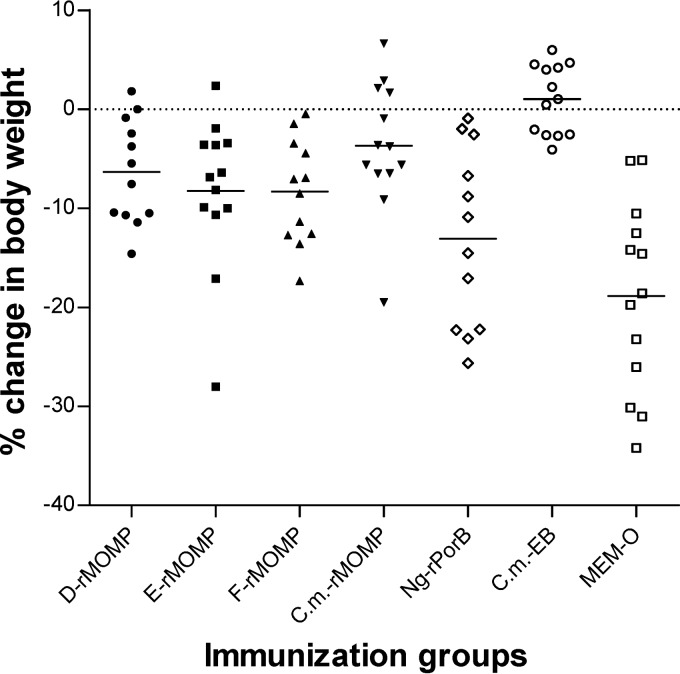

By day 10 p.c., all the groups of mice immunized with rMOMP had lost less body weight than the groups immunized with MEM-0 (P < 0.05; Fig. 4 and Table 4). The mice vaccinated with Cm-rMOMP had lost significantly less weight (3.66%) than the group inoculated with Ng-rPorB (13%) (P < 0.05).

Fig 4.

Percentage change in mean body weight of mice at day 10 following the i.n. challenge with C. muridarum. Dots represent individual animals, and the horizontal bars correspond to the means for the different groups.

Table 4.

Disease burden and yields of C. muridarum from the lungs at day 10 postinfection

| Vaccine | % change in body wt (mean ± 1 SE) | Lung wt (g) (mean ± 1 SE) | Median no. of IFU recovered from lungs (min-max; × 103) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-rMOMP | −6.32 ± 1.47a | 0.20 ± 0.01a,c | 384e,f,g (0.7–264,550) |

| E-rMOMP | −8.24 ± 2.13a | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 7,560f (26–19,701,000) |

| F-rMOMP | −8.32 ± 1.46a | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 11,943e,f (124–25,340) |

| Cm-rMOMP | −3.66 ± 1.83a,b | 0.18 ± 0.01a,b,c,d | 138e,f,g,h (5–58,680) |

| Ng-rPorB | −13.06 ± 2.5 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 40,255 (865–28,954,500) |

| Cm-EB | 1.01 ± 0.97 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | BLDi (BLD-0.4) |

| MEM-0 | −18.86 ± 2.66 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 69,840 (14,307–41,193,000) |

P < 0.05 by the one-way ANOVA Holm-Sidak method compared to the MEM-0-immunized group.

P < 0.05 by the one-way ANOVA Holm-Sidak method compared to the Ng-rPorB-immunized group.

P < 0.05 by the one-way ANOVA Holm-Sidak method compared to the E-rMOMP-immunized group.

P < 0.05 by the one-way ANOVA Holm-Sidak method compared to the F-rMOMP-immunized group.

P < 0.05 by Mann-Whitney rank test compared to the Ng-rPorB-immunized group.

P < 0.05 by Mann-Whitney rank test compared to the MEM-0-immunized group.

P < 0.05 by Mann-Whitney rank test compared to the F-rMOMP-immunized group.

P < 0.05 by Mann-Whitney rank test compared to the E-rMOMP-immunized group.

BLD, below the limit of detection.

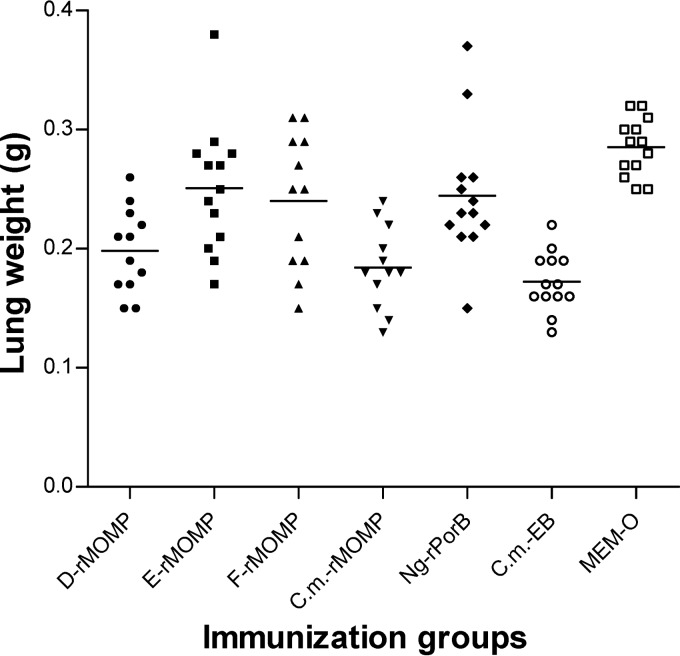

Weight of the lungs.

At 10 days following the i.n. challenge, the mice were euthanized and their lungs were harvested and weighed (Fig. 5 and Table 4). The weight of the lungs was used as an indication of the local inflammatory response. The mean weight of the lungs from the positive-control mice vaccinated with Cm-EB was 0.17 ± 0.01 g versus 0.29 ± 0.01 g for the MEM-0 negative control (P < 0.05). The weight of the lungs from mice vaccinated with D-rMOMP (0.20 ± 0.01g) and Cm-rMOMP (0.18 ± 0.01g) was significantly lower than those of the MEM-0 negative-control group (P < 0.05). Only the weight of the lungs from the mice immunized with Cm-rMOMP was significantly different from the weight of the lungs of mice immunized with Ng-rPorB (0.24 ± 0.02 g; P < 0.05).

Fig 5.

Lung weights at day 10 following the i.n. challenge with C. muridarum. Dots represent individual animals, and the horizontal bars correspond to the means for the different groups.

Recovery of C. muridarum from the lungs.

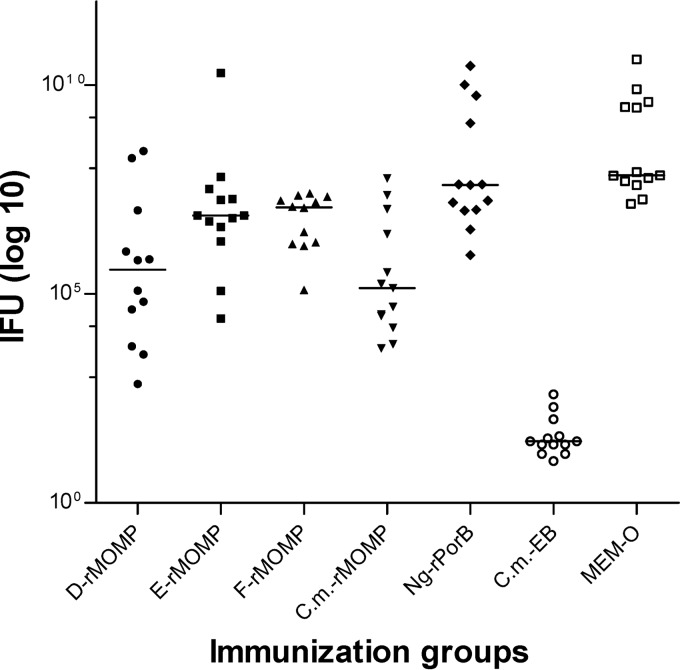

At day 10 p.c., the lungs were homogenized and the number of chlamydial IFU was determined using HeLa monolayers (Fig. 6 and Table 4). In the positive-control group immunized i.n. with live Cm-EB, the median number of IFU was below 50, the limit of detection (range, <50 to 400). Ten of the 13 animals in this group had IFU counts below the limit of detection. For the negative-control groups inoculated with Ng-rPorB or MEM-0, the median number of IFU was 40,255 × 103 (range, 865 × 103 to 28,954,500 × 103) or 69,840 × 103 (range, 14,307 × 103 to 41,193,000 × 103), respectively. A significant reduction in the number of IFU recovered from the lungs was observed in the four groups of mice vaccinated with rMOMP from the various serovars compared with the negative control inoculated with MEM-0 (P < 0.05). Also, the animals immunized with D-rMOMP, F-rMOMP, or Cm-rMOMP had a significantly lower number of IFU than those vaccinated with Ng-rPorB (P < 0.05). The most significant reduction was observed in the mice immunized with Cm-rMOMP, where the median number of IFU was 138 × 103 and the range was 5 × 103 to 58,680 × 103, followed by the D-rMOMP-immunized group (median IFU, 384 × 103; range, 0.7 × 103 to 264,550 × 103), with no statistical difference between them (P = 0.892). For the group vaccinated with E-rMOMP, the median IFU was 7,560 × 103 and the range was 26 × 103 to 19,701,000 × 103, statistically not different from the F-rMOMP-immunized group (median, 11,943 × 103; range, 124 × 103 to 25,340 × 103; P = 0.807).

Fig 6.

Number of C. muridarum IFU recovered from the lungs at day 10 following the i.n. challenge with Cm-EB. Dots represent individual animals, and the horizontal bars correspond to the medians for the different groups.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that vaccination with rMOMP from the C. trachomatis human serovars D, E, and F and the C. muridarum isolate elicit in mice antibodies that cross-react with Cm-EB, the Cm-rMOMP, and synthetic peptides of the Cm-MOMP. Furthermore, T cells from the immunized mice proliferated and produced IFN-γ when stimulated with Cm-EB. As shown by changes in body weight, weight of the lungs, and the number of C. muridarum IFU recovered from the lungs, although the protection was more robust in the animals immunized with the Cm-rMOMP, all four groups of vaccinated mice were significantly protected against an i.n. challenge with Cm-EB compared with the negative controls. To our knowledge, this is the first time that vaccination of mice with recombinant MOMP preparations of the C. trachomatis human serovars have been shown to elicit cross-serovar protection to the C. muridarum isolate.

One of the potential limitations of using MOMP as a Chlamydia vaccine antigen is the possibility that protection will be limited to the homologous serovar (1, 11). Following the isolation of multiple human strains of C. trachomatis, Wang and Grayston performed cross-protection experiments in a mouse model (16, 17). Mice immunized with one C. trachomatis isolate were subsequently challenged intravenously with the homologous and heterologous isolates. The degree of protection was quantified, and a relationship was established between all the C. trachomatis isolates. This interrelation between the serovars was further supported by cross-reactivity with the microimmunofluorescence (MIF) assay with sera from mice inoculated intravenously with the C. trachomatis serovars. The results of the two experimental approaches, i.e., mouse toxicity prevention and MIF, led to the division of the C. trachomatis human isolates into 15 main immunotypes/serovars (17). The immunotypes were found to fall into two major groups, the C and the B complex. The C complex includes the C, J, H, I, and A immunotypes, and the B complex encompasses types B, Ba, E, D, L1, and L2. Types K and L3 are related to the C complex, while types G and F are related to the B complex. Furthermore, within each complex, Wang and Grayston (17) found asymmetric cross-reaction among the various types. For example, type C antiserum reacted strongly with the homologous C and heterologous A antigen, while type A antisera reacted strongly with A but not with the C antigen. Based on these findings, they called the C serovar antigenically senior to A and A junior to C. Thus, in the C complex, the senior-to-junior relationship of the immunotypes is C, J, H, I, A, K, and L3, while in the B group the senior-to-junior relationship is B, Ba, E, D, L1, and L2 serovars. G and F are very closely related to each other, and they cross-react mainly with E and D. These results suggested that vaccination with the senior serovar from each group could protect against the most junior isolates of the same group. The classification of Wang and Grayston was subsequently shown to correspond with the DNA sequence of the VD of MOMP (30, 40). From these experiments, it was concluded that MOMP was the major antigenic determinant of Chlamydia and most likely accounting for the protection observed in the mouse experiments and the trachoma trials (30, 41–43). Here, we used C. muridarum to challenge the animals because it is a mouse isolate and is very closely related to the human serovars (30, 44). Except for the plasticity region, there is an extraordinary degree of DNA homology between C. muridarum and the C. trachomatis human serovars (44). The Cm-MOMP also has the same structure as the MOMP of the human serovars, and its amino acid sequence differs significantly only in the VD, like the human serovars do among themselves (29, 45). C. muridarum produces in mice acute and long-term sequelae that parallel those observed in humans infected with C. trachomatis, and, therefore, it is the preferred isolate for characterizing the pathogenesis of chlamydial infections in mice and testing vaccine candidates (46–48).

Vaccination trials performed in the 1960s utilized live and whole-inactivated C. trachomatis EB to protect against trachoma (1, 11). These trials, performed both in humans and in nonhuman primates, concluded that the protection was serovar or, at most, serogroup specific, supporting Wang and Grayston's classification (17). However, subsequent immunization trials performed in animal models obtained different results. For example, Digiacomo et al. (49) inoculated the urethra of two sexually mature male baboons (Papio cynocephalus) with the human C. trachomatis serovar D and/or I. Following the primary infection, the animals were challenged with the homologous or the heterologous serovar and, as determined by urethral shedding, were found to be protected.

Ramsey et al. (50, 51) studied cross-serovar protection in mice using the C. muridarum isolate. Following a primary vaginal infection with C. muridarum, C3H/HeN mice were solidly protected, as determined by vaginal shedding, against a subsequent vaginal challenge with C. muridarum or with C. trachomatis serovars E or L2. A primary infection with C. trachomatis serovar E also protected against challenges with C. muridarum or C. trachomatis serovar L2, although the level of protection was not as robust as that resulting from a primary infection with C. muridarum. Interestingly, in a subsequent study, Ramsey et al. (51) also showed that C3H/HeN mice, intravaginally infected with C. trachomatis serovar E, were not protected against infertility resulting from a secondary challenge with C. muridarum. Lyons et al. infected outbred CF-1 mice intravaginally with C. trachomatis serovar D or H and challenged the animals by the same route. Serovar D infection resulted in significant homotypic and heterotypic protection against reinfection, while serovar H elicited only weak homotypic protection. Therefore, from recent studies, using live Chlamydia vaccines, we cannot conclude that the protection is exclusively serovar or subgroup specific. The apparent discrepancies between the results could be due to the animal model used, to differences in virulence of particular serovars or strains of Chlamydia, and/or to experimental parameters not yet characterized.

During the trachoma vaccination trials, some individuals, upon exposure to Chlamydia, developed a hypersensitivity reaction that was more severe than the lesions resulting from a primary infection (1, 11, 20–23, 26). This hypersensitivity reaction was thought to be due to an antigen present in Chlamydia, and therefore a subunit vaccine was considered an alternative (24, 42, 52). Recombinant preparations of MOMP have been extensively used in animal models to protect against the homologous serovar, but we are aware of only few reports that used rMOMP to elicit heterotypic protection. For example, Tuffrey et al. (53) immunized C3H mice by the subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intraperitoneal route or in the Peyer's patch, with a truncated rMOMP from C. trachomatis serovar L1, and challenged the animals intrabursally with C. trachomatis serovar F. Limited protection against vaginal shedding and salpingitis was observed in the rMOMP-vaccinated animals, but no protection against infertility was achieved. Similarly, Li et al. (54) vaccinated mice with the C. trachomatis serovar D rMOMP and challenged the animals intravaginally with C. muridarum. No significant differences in vaginal shedding or tubal pathology were observed in these animals in comparison with a group of mice immunized using an unrelated antigen.

Protection in the mouse model against a secondary genital infection with C. muridarum, following a primary infection with live C. muridarum, appears to be mediated by CD4 Th1 and B cells and antibodies (43, 55, 56). In our studies, the T-cell-proliferative responses to Cm-EB were more robust in the mice immunized with rMOMP from C. muridarum and C. trachomatis D and F than from the animals vaccinated with the C. trachomatis E-rMOMP, compared with control mice immunized with the Ng-rPorB, and were not significantly different compared among themselves. Most of the T-cell epitopes of MOMP have been identified in the constant domains (CD), and therefore we should expect that they will cross-react with all the C. trachomatis serovars and the C. muridarum isolate (36, 57). The differences in the T-cell reactivity among the animals vaccinated with the four serovars in comparison with the group immunized with Cm-EB may be due, like in the case of B-cell epitopes, to differences in the conformation of the MOMP. There are now several reports demonstrating that the T-cell response is dependent on the conformation of the antigen (58–62). For example, Musson et al. (59) characterized the mechanisms of antigen presentation of CD4+ T cell epitopes of the Caf1 antigen of Yersinia pestis. They showed that the degree of antigen processing was dependent on the structural content of the epitopes in the antigen. Epitopes located in the globular domain of the protein were presented by newly synthesized major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II, after low pH-dependent lysosomal processing. On the other hand, epitopes in a flexible strand of the protein were presented by mature MHC class II, independent of low pH, and did not require proteolytic processing. Also, Tikhonova et al. (60) have shown that T cells not undergoing MHC-specific thymic selection can express T cell receptors that recognize conformational epitopes independently of MHC molecules.

Here, we used Cm-EB and rMOMP from four isolates (C. trachomatis D, E, and F and C. muridarum) and synthetic peptides corresponding to the Cm-MOMP as antigens to characterize the antibody response. However, due to differences in the affinity and/or avidity of the primary and/or secondary antibodies, a direct quantitative assessment cannot be made, but we can make relative comparisons using ratios. For example, serum from the mice immunized with Cm-EB had an IgG GMT of 16,127 when reacted with Cm-EB, while when reacted with Cm-rMOMP the GMT was 3,667 (ratio, 4.4). In contrast, for mice immunized with Cm-rMOMP, the values were 102,400 and 620,838 (ratio, 0.17). As expected, the Cm-EB/rMOMP IgG ratios were even more skewed for sera from the mice immunized with the C. trachomatis human serovar D (2,016/178,289 = 0.011), E (4,032/117,627 = 0.034), or F (1,270/77,605 = 0.016). Most likely, this indicates that mice immunized with Cm-EB developed antibodies to surface-exposed conformational and/or linear serovar-specific epitopes, while those vaccinated with rMOMP reacted mainly with cryptic linear epitopes. This was confirmed, at least in part, when the sera were tested against 25-mer overlapping peptides of the Cm-MOMP. As expected, only samples from animals immunized with Cm-rMOMP recognized the peptides corresponding to the Cm-MOMP VD. On the other hand, reactivity to peptides corresponding to the Cm-MOMP CD were similar for the four groups of mice immunized with C. muridarum and C. trachomatis D, E, or F. Studies can now be performed using peptides from the CD that elicit antibodies and T-cell responses to determine their ability to protect. Based on the results of the in vitro neutralization assay, cross-reactive protective antibodies should be expected.

Vaccination with live Cm-EB or with the C. muridarum purified native MOMP (nMOMP) elicits a more robust protection than immunization with Cm-rMOMP (33, 63). Conformational or linear serovar-specific epitopes present in the native antigen may be dominant, and, although more effective at inducing protection against the homologous serovar, they may limit the immune response to hidden/cryptic epitopes that may be cross-reactive. Identification of common, nonimmunodominant antigens, with the goal of formulating vaccines that induce cross-isolate protection, is a major challenge for several human pathogens, such as Neisseria meningitides, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and influenza virus (64–67). For example, Moe et al. (64) showed that multiple vaccinations of mice with three meningococcal strains that were heterologous with respect to several antigens resulted in an enhanced immune response to conserved proteins that normally are poorly immunogenic. In the case of hepatitis C virus, it was shown that vaccination with a recombinant gpE1E2 elicited neutralizing antibodies in mice and chimpanzees to epitopes that are poorly induced during natural infection. These findings suggest that the shared, hidden B-cell epitopes are poorly presented to the immune system in the infectious organism and when using an antigen in its native conformation.

In conclusion, we have shown that immunization with rMOMP from the C. trachomatis human serovars D, E, and F and the C. muridarum isolate can protect mice against an i.n. challenge with C. muridarum. These results demonstrate that MOMP can elicit significant heterotypic protection, in particular against pathogen burden, although not necessarily against disease status. Although the level of protection was not the same against all the serovars, our findings are important because even not highly efficacious Chlamydia vaccines can have a major impact on the prevalence of these infections (68). In addition, to increase the range of protection, MOMP from more than one serovar could be included in the vaccine, as has recently been done with vaccines to protect against HPV (69, 70).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI-67888 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 March 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Schachter J, Dawson C. 1978. Human chlamydial infections. PSG Publishing Co., Littleton, CO [Google Scholar]

- 2. CDC 2009. Chlamydia screening among sexually active young female enrollees of health plans—United States, 2000–2007. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 58:362–365 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ness RB, Smith KJ, Chang CC, Schisterman EF, Bass DC. 2006. Prediction of pelvic inflammatory disease among young, single, sexually active women. Sex. Transm. Dis. 33:137–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Darville T. 2006. Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection in adolescents and young adults. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 582:85–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miller WC, Ford CA, Morris M, Handcock MS, Schmitz JL, Hobbs MM, Cohen MS, Harris KM, Udry JR. 2004. Prevalence of chlamydial and gonococcal infections among young adults in the United States. JAMA 291:2229–2236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stamm W. 2008. Chlamydia trachomatis infections of the adult, p 575–593 In Holmes K, Sparling P, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JW, Corey L, Cohen MS, Watts DH. (ed), Sexually transmitted diseases. McGrawHill Book Co., New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 7. Darville T. 2005. Chlamydia trachomatis infections in neonates and young children. Semin. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 16:235–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arth C, Von Schmidt B, Grossman M, Schachter J. 1978. Chlamydial pneumonitis. J. Pediatr. 93:447–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stutman HR, Rettig PJ, Reyes S. 1984. Chlamydia trachomatis as a cause of pneumonitis and pleural effusion. J. Pediatr. 104:588–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Westrom L, Joesoef R, Reynolds G, Hagdu A, Thompson SE. 1992. Pelvic inflammatory disease and fertility. A cohort study of 1,844 women with laparoscopically verified disease and 657 control women with normal laparoscopic results. Sex. Transm. Dis. 19:185–192 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Taylor HR. 2008. Trachoma: a blinding scourge from the Bronze Age to the twenty-first century, 1st ed Haddington Press Pry Ltd., Victoria, Australia [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brunham RC, Pourbohloul B, Mak S, White R, Rekart ML. 2005. The unexpected impact of a Chlamydia trachomatis infection control program on susceptibility to reinfection. J. Infect. Dis. 192:1836–1844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gotz H, Lindback J, Ripa T, Arneborn M, Ramsted K, Ekdahl K. 2002. Is the increase in notifications of Chlamydia trachomatis infections in Sweden the result of changes in prevalence, sampling frequency or diagnostic methods? Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 34:28–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Plummer FA, Simonsen JN, Cameron DW, Ndinya-Achola JO, Kreiss JK, Gakinya MN, Waiyaki P, Cheang M, Piot P, Ronald AR. 1991. Cofactors in male-female sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Infect. Dis. 163:233–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Anttila T, Saikku P, Koskela P, Bloigu A, Dillner J, Ikaheimo I, Jellum E, Lehtinen M, Lenner P, Hakulinen T, Narvanen A, Pukkala E, Thoresen S, Youngman L, Paavonen J. 2001. Serotypes of Chlamydia trachomatis and risk for development of cervical squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA 285:47–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang SP, Grayston JT. 1963. Classification of trachoma virus strains by protection of mice from toxic death. J. Immunol. 90:849–856 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang SP, Grayston J. 1984. Microimmunofluorescence serology of Chlamydia trachomatis. In Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. (ed), Medical virology III. Elsevier Science Publishing, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nigg C. 1942. An unidentified virus which produces pneumonia and systemic infection in mice. Science 95:49–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nigg C, Eaton MD. 1944. Isolation from normal mice of a pneumotropic virus which forms elementary bodies. J. Exp. Med. 79:497–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grayston JT, Wang SP. 1978. The potential for vaccine against infection of the genital tract with Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex. Transm. Dis. 5:73–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dawson C, Wood TR, Rose L, Hanna L. 1967. Experimental inclusion conjunctivitis in man. 3. Keratitis and other complications. Arch. Ophthalmol. 78:341–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nichols RL, Bell SD, Jr, Murray ES, Haddad NA, Bobb AA. 1966. Studies on trachoma. V. Clinical observations in a field trial of bivalent trachoma vaccine at three dosage levels in Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 15:639–647 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Woolridge RL, Grayston JT, Chang IH, Cheng KH, Yang CY, Neave C. 1967. Field trial of a monovalent and of a bivalent mineral oil adjuvant trachoma vaccine in Taiwan school children. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 63(Suppl):1645–1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morrison RP, Belland RJ, Lyng K, Caldwell HD. 1989. Chlamydial disease pathogenesis. The 57-kDa chlamydial hypersensitivity antigen is a stress response protein. J. Exp. Med. 170:1271–1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nichols RL, Bell SD, Jr, Haddad NA, Bobb AA. 1969. Studies on trachoma. VI. Microbiological observations in a field trial in Saudi Arabia of bivalent trachoma vaccine at three dosage levels. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 18:723–730 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang S, Grayston JT. 1962. Trachoma in the Taiwan monkey Macaca cyclopis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 98:177–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sun G, Pal S, Sarcon AK, Kim S, Sugawara E, Nikaido H, Cocco MJ, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. 2007. Structural and functional analyses of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Bacteriol. 189:6222–6235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nikaido H. 1992. Porins and specific channels of bacterial outer membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 6:435–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stephens RS, Sanchez-Pescador R, Wagar EA, Inouye C, Urdea MS. 1987. Diversity of Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein genes. J. Bacteriol. 169:3879–3885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fitch WM, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. 1993. Phylogenetic analysis of the outer-membrane-protein genes of Chlamydiae, and its implication for vaccine development. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10:892–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grayston JT, Wang S. 1975. New knowledge of Chlamydiae and the diseases they cause. J. Infect. Dis. 132:87–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Caldwell HD, Kromhout J, Schachter J. 1981. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 31:1161–1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sun G, Pal S, Weiland J, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. 2009. Protection against an intranasal challenge by vaccines formulated with native and recombinant preparations of the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein. Vaccine 27:5020–5025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schagger H, von Jagow G. 1987. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166:368–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pal S, Fielder TJ, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. 1994. Protection against infertility in a BALB/c mouse salpingitis model by intranasal immunization with the mouse pneumonitis biovar of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 62:3354–3362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Su H, Morrison RP, Watkins NG, Caldwell HD. 1990. Identification and characterization of T helper cell epitopes of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Exp. Med. 172:203–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pal S, Theodor I, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. 2001. Immunization with the Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis major outer membrane protein can elicit a protective immune response against a genital challenge. Infect. Immun. 69:6240–6247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pal S, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. 2005. Vaccination with the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein can elicit an immune response as protective as that resulting from inoculation with live bacteria. Infect. Immun. 73:8153–8160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Peterson EM, Zhong GM, Carlson E, de la Maza LM. 1988. Protective role of magnesium in the neutralization by antibodies of Chlamydia trachomatis infectivity. Infect. Immun. 56:885–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stephens RS, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, Mitchell W, Olinger L, Tatusov RL, Zhao Q, Koonin EV, Davis RW. 1998. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science 282:754–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brunham RC, Zhang DJ, Yang X, McClarty GM. 2000. The potential for vaccine development against chlamydial infection and disease. J. Infect. Dis. 181(Suppl 3):S538–S543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. de la Maza LM, Peterson EM. 2002. Vaccines for Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 3:980–986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Morrison RP, Caldwell HD. 2002. Immunity to murine chlamydial genital infection. Infect. Immun. 70:2741–2751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Read TD, Brunham RC, Shen C, Gill SR, Heidelberg JF, White O, Hickey EK, Peterson J, Utterback T, Berry K, Bass S, Linher K, Weidman J, Khouri H, Craven B, Bowman C, Dodson R, Gwinn M, Nelson W, DeBoy R, Kolonay J, McClarty G, Salzberg SL, Eisen J, Fraser CM. 2000. Genome sequences of Chlamydia trachomatis MoPn and Chlamydia pneumoniae AR39. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:1397–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fielder TJ, Pal S, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. 1991. Sequence of the gene encoding the major outer membrane protein of the mouse pneumonitis biovar of Chlamydia trachomatis. Gene 106:137–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. de la Maza LM, Pal S, Khamesipour A, Peterson EM. 1994. Intravaginal inoculation of mice with the Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis biovar results in infertility. Infect. Immun. 62:2094–2097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pal S, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. 1999. A murine model for the study of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections during pregnancy. Infect. Immun. 67:2607–2610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pal S, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. 2004. New murine model for the study of Chlamydia trachomatis genitourinary tract infections in males. Infect. Immun. 72:4210–4216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Digiacomo RF, Gale JL, Wang SP, Kiviat MD. 1975. Chlamydial infection of the male baboon urethra. Br. J. Vener. Dis. 51:310–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ramsey KH, DeWolfe JL, Salyer RD. 2000. Disease outcome subsequent to primary and secondary urogenital infection with murine or human biovars of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 68:7186–7189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ramsey KH, Cotter TW, Salyer RD, Miranpuri GS, Yanez MA, Poulsen CE, DeWolfe JL, Byrne GI. 1999. Prior genital tract infection with a murine or human biovar of Chlamydia trachomatis protects mice against heterotypic challenge infection. Infect. Immun. 67:3019–3025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Brunham RC, Rey-Ladino J. 2005. Immunology of Chlamydia infection: implications for a Chlamydia trachomatis vaccine. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5:149–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tuffrey M, Alexander F, Conlan W, Woods C, Ward M. 1992. Heterotypic protection of mice against chlamydial salpingitis and colonization of the lower genital tract with a human serovar F isolate of Chlamydia trachomatis by prior immunization with recombinant serovar L1 major outer-membrane protein. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138(Part 8):1707–1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li W, Guentzel MN, Seshu J, Zhong G, Murthy AK, Arulanandam BP. 2007. Induction of cross-serovar protection against genital chlamydial infection by a targeted multisubunit vaccination approach. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14:1537–1544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Morrison SG, Morrison RP. 2001. Resolution of secondary Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection in immune mice with depletion of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Infect. Immun. 69:2643–2649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Morrison SG, Morrison RP. 2005. A predominant role for antibody in acquired immunity to chlamydial genital tract reinfection. J. Immunol. 175:7536–7542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ortiz L, Demick KP, Petersen JW, Polka M, Rudersdorf RA, Van der Pol B, Jones R, Angevine M, DeMars R. 1996. Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein (MOMP) epitopes that activate HLA class II-restricted T cells from infected humans. J. Immunol. 157:4554–4567 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hanada K, Yewdell JW, Yang JC. 2004. Immune recognition of a human renal cancer antigen through post-translational protein splicing. Nature 427:252–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Musson JA, Morton M, Walker N, Harper HM, McNeill HV, Williamson ED, Robinson JH. 2006. Sequential proteolytic processing of the capsular Caf1 antigen of Yersinia pestis for major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted presentation to T lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 281:26129–26135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tikhonova AN, Van Laethem F, Hanada K, Lu J, Pobezinsky LA, Hong C, Guinter TI, Jeurling SK, Bernhardt G, Park JH, Yang JC, Sun PD, Singer A. 2012. Alpha beta T cell receptors that do not undergo major histocompatibility complex-specific thymic selection possess antibody-like recognition specificities. Immunity 36:79–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vigneron N, Stroobant V, Chapiro J, Ooms A, Degiovanni G, Morel S, van der Bruggen P, Boon T, Van den Eynde BJ. 2004. An antigenic peptide produced by peptide splicing in the proteasome. Science 304:587–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Warren EH, Vigneron NJ, Gavin MA, Coulie PG, Stroobant V, Dalet A, Tykodi SS, Xuereb SM, Mito JK, Riddell SR, Van den Eynde BJ. 2006. An antigen produced by splicing of noncontiguous peptides in the reverse order. Science 313:1444–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tifrea DF, Sun G, Pal S, Zardeneta G, Cocco MJ, Popot JL, de la Maza LM. 2011. Amphipols stabilize the Chlamydia major outer membrane protein and enhance its protective ability as a vaccine. Vaccine 29:4623–4631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Moe GR, Zuno-Mitchell P, Hammond SN, Granoff DM. 2002. Sequential immunization with vesicles prepared from heterologous Neisseria meningitidis strains elicits broadly protective serum antibodies to group B strains. Infect. Immun. 70:6021–6031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Liu L, Hao Y, Luo Z, Huang Y, Hu X, Liu Y, Shao Y. 2012. Broad HIV-1 neutralizing antibody response induced by heterologous gp140/gp145 DNA prime-vaccinia boost immunization. Vaccine 30:4135–4143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kachko A, Kochneva G, Sivolobova G, Grazhdantseva A, Lupan T, Zubkova I, Wells F, Merchlinsky M, Williams O, Watanabe H, Ivanova A, Shvalov A, Loktev V, Netesov S, Major ME. 2011. New neutralizing antibody epitopes in hepatitis C virus envelope glycoproteins are revealed by dissecting peptide recognition profiles. Vaccine 30:69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wilkinson TM, Li CK, Chui CS, Huang AK, Perkins M, Liebner JC, Lambkin-Williams R, Gilbert A, Oxford J, Nicholas B, Staples KJ, Dong T, Douek DC, McMichael AJ, Xu XN. 2012. Preexisting influenza-specific CD4+ T cells correlate with disease protection against influenza challenge in humans. Nat. Med. 18:274–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. de la Maza MA, de la Maza LM. 1995. A new computer model for estimating the impact of vaccination protocols and its application to the study of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections. Vaccine 13:119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bryan JT. 2007. Developing an HPV vaccine to prevent cervical cancer and genital warts. Vaccine 25:3001–3006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler C, Ferris DG, Jenkins D, Schuind A, Zahaf T, Innis B, Naud P, De Carvalho NS, Roteli-Martins CM, Teixeira J, Blatter MM, Korn AP, Quint W, Dubin G. 2004. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 364:1757–1765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]