Abstract

To survive in various environments, from host tissue to soil, opportunistic bacterial pathogens must be metabolically flexible and able to use a variety of nutrient sources. We are interested in Pseudomonas aeruginosa's catabolism of quaternary amine compounds that are prevalent in association with eukaryotes. Carnitine and acylcarnitines are abundant in animal tissues, particularly skeletal muscle, and are used to shuttle fatty acids in and out of the mitochondria, where they undergo β-oxidation. We previously identified the genes required for carnitine catabolism as the first four genes in the carnitine operon (caiX-cdhCAB; PA5388 to PA5385). However, the last gene in the operon, PA5384, was not required for carnitine catabolism. We were interested in determining the function of PA5384. Bioinformatic analyses along with the genomic location of PA5384 led us to hypothesize a role for PA5384 in acylcarnitine catabolism. Here, we have characterized PA5384 as an l-enantiomer-specific short-chain acylcarnitine hydrolase that is required for growth and hydrolysis of acetyl- and butyrylcarnitine to carnitine and the respective short-chain fatty acid. The liberated carnitine and its downstream catabolic product, glycine betaine, are subsequently available to function as osmoprotectants in hyperosmotic environments and induce transcription of the virulence factor phospholipase C, plcH. Furthermore, we confirmed that acylcarnitines with 2- to 16-carbon chain lengths, except for octanoylcarnitine (8 carbons), can be utilized by P. aeruginosa as sole carbon and nitrogen sources. These findings expand our knowledge of short-chain acylcarnitine catabolism and also point to remaining questions related to acylcarnitine transport and hydrolysis of medium- and long-chain acylcarnitines.

INTRODUCTION

Carnitine and acylcarnitines are quaternary amine compounds that are abundant in mammalian tissues and play important roles in eukaryotic metabolism (1). Carnitine facilitates the translocation of fatty acids into the mitochondrial matrix, where they undergo β-oxidation to produce energy for the cell (2, 3). This translocation is dependent on the formation of an ester linkage between the fatty acid and the hydroxyl oxygen on carbon three; this esterified carnitine is referred to as O-acylcarnitine or, as we will use throughout this study, acylcarnitine. While there are no eukaryotic enzymes that catabolize carnitine (2), free carnitine can be utilized by some bacteria, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, as a sole carbon, nitrogen, and energy source (4, 5). The concentrations of carnitine and acylcarnitines in humans range from 50 μM in plasma to the low-millimolar range in tissues; thus, these compounds are potential sources of energy in colonization and infection (2, 6, 7). In P. aeruginosa, carnitine and its downstream catabolic product, glycine betaine, can function as osmoprotectants (8–10) and may be important for enhanced growth under hyperosmotic conditions, such as the environment of the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis and the urinary tract (11, 12). The generation of glycine betaine via carnitine catabolism also allows carnitine to induce expression of the virulence factor hemolytic phospholipase C, PlcH (8). During infection, PlcH can function to induce a proinflammatory response, suppress oxidative burst in neutrophils, degrade pulmonary surfactant, and increase endothelial cell death (13–18).

We previously identified the metabolic pathway responsible for carnitine catabolism in P. aeruginosa and determined that all but the last gene in the carnitine catabolism operon are required for carnitine degradation (19). The last gene in the operon, PA5384, is immediately downstream of the carnitine dehydrogenase genes (CDH) but is not required for growth on carnitine (19). However, the genomic location of PA5384 provided insight into its potential function. Uanschou et al. compared the genomic sequences of predicted CDH genes in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and determined that many of the CDH-containing operons had an unidentified esterase/lipase downstream of the CDH gene(s) (7). PA5384 fits this pattern, as it is immediately downstream of cdhB and is bioinformatically predicted to be a lipolytic enzyme (19, 20). The prediction made by Uanschou et al., that PA5384 and homologs encode an acylcarnitine hydrolase, has not been directly tested. Previous work has briefly biochemically characterized an acylcarnitine hydrolase from an Alcaligenes species (21) that is used as a diagnostic tool for measuring acylcarnitine in serum. However, this study provided no genetic identification associated with the purified hydrolase (22). Acylcarnitine catabolism has been studied in Pseudomonas putida (23), but it was not known if P. aeruginosa can hydrolyze acylcarnitines or employ them as a sole carbon and nitrogen source.

In this study, we demonstrate that P. aeruginosa can utilize acylcarnitines as sole carbon, nitrogen, and energy sources. We also demonstrate that hydrolysis of acylcarnitines enables osmoprotection via production of carnitine and the downstream catabolite glycine betaine, improving cell survival in hyperosmotic environments and inducing the expression of the virulence factor PlcH. In addition, we characterize the function of the PA5384 enzyme and determine its role in acylcarnitine metabolism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

P. aeruginosa PA14 (24), PAO1 (25), and derivative strains were maintained on Pseudomonas isolation agar (PIA; Difco) plates or in LB broth with gentamicin added, when necessary, at 50 or 40 μg ml−1, respectively (Table 1). Escherichia coli NEB5α was maintained on LB plates or in LB broth supplemented, when necessary, with gentamicin at 10 or 7 μg ml−1, respectively, or in LB broth with 100 μg ml−1 kanamycin when needed.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Database no. | Description (reference or source)a |

|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | ||

| PAO1 wild type | MJ79 | P. aeruginosa WT (25) |

| PA5384::Tn5 | MJ206 | PA01 transposon mutant ID 47947, position in ORF 570 (31) |

| PA5384::Tn5 | MJ207 | PA01 transposon mutant ID 52172, position in ORF 236 (31) |

| PA5384::Tn5 attTn7::PA5384 | JM118 | trans-complementation of PA5384::Tn ID 47947 (this study) |

| PA5384::Tn5 attTn7::PA5384 | JM119 | trans-complementation of PA5384::Tn ID 52172 (this study) |

| P. aeruginosa PA14 | ||

| PA14 wild type | MJ101 | P. aeruginosa WT (24) |

| ΔPA5384 | MJ264 | Clean PA5384 deletion (this study) |

| PA5384-FLAG | JM116 | PA14 with PA5384 C-terminal FLAG-tag clone 1 (this study) |

| PA5384-FLAG | JM117 | PA14 with PA5384 C-terminal FLAG-tag clone 2 (this study) |

| PA14 pMQ30 integrant | JM141 | PA14 with PA4921-pMQ30 genome integrant (this study) |

| E. coli | ||

| E. coli wild type | MJ340 | S17/λpir |

| E. coli T7 Express | NEB C2566 | |

| E. coli NEB5α | NEB C2987 | |

| E. coli T7 Express with pJAM8 | JM17 | T7 Express with pJAM8 (this study) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMQ30 | Suicide vector, Gmr (27) | |

| pMQ80 | High-copy-number Pseudomonas vector, Gmr (27) | |

| pET-30a | T7 expression vector, 6× His N-terminal tag, Kanr (Novagen) | |

| pUCP22 | High-copy-number Pseudomonas stabilization vector, Gmr (49) | |

| pUC18-mini-Tn7T-Gm | Gmr on mini-Tn7T (32) | |

| pTNS2 | Plasmid carrying the attTn7 transposase (33) | |

| pMW22 | Promoter plcH-lacZYA transcriptional fusion (35) | |

| pMW79 | PA14 genomic clone with PA5380–PA5389 in pMQ8 (19) | |

| pMW86 | Causes deletion of PA5384 in pMQ30 (this study) | |

| pJAM6 | PA5384-PA5388 in pUCP22, Gmr (derived from pMW79) (this study) | |

| pJAM8 | PA5384 in pET-30a expression vector (this study) | |

| pJAM10 | PA14 PA5384 in pMQ30 (this study) | |

| pJAM34 | PA14 PA5384FLAG, C terminal (this study) | |

| pJAM61 | PA14 PA5388 promoter in pJAM8 (this study) | |

| pJAM62 | PA14 PA5388 promoter fused to PA5384 in pUC18-mini-Tn7T-Gm (32 and this study) |

ORF, open reading frame.

To assess growth on acylcarnitines, P. aeruginosa cultures were pregrown overnight at 37°C on a rotary wheel in 3 ml of morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) minimal medium with 20 mM pyruvate and 5 mM glucose added as carbon sources (26). When necessary, gentamicin was added to these minimal medium cultures at 20 μg ml−1. Cells from these overnight cultures were added to MOPS medium without a nitrogen source or MOPS medium with a 20 mM concentration of the specified carbon source in 48-well plastic culture dishes at a final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05. These plates were shaken at 170 rpm for 24 h at 37°C for carnitine and acylcarnitines with 2- to 14-carbon chain lengths (designated 2C, 4C, …, 16C) or at room temperature for palmitoylcarnitine due to micelle formation of palmitoylcarnitine at 37°C. Growth was assessed by OD600 on a Synergy 2 BioTek plate reader. Measurement of growth at OD600 was not possible for palmitoylcarnitine due to the optical interference from the micelles that formed; therefore, triplicate serial dilutions were plated onto PIA and incubated for 24 h to determine CFU ml−1. The suppliers for the compounds are the following: l-carnitine, l-acetylcarnitine, and d,l-palmitoylcarnitine are from Sigma; l-butyrylcarnitine and d-acetylcarnitine are from Crystal Chem; d,l-hexanoylcarnitine, d,l-decanoylcarnitine, d,l-lauryolcarnitine, and d,l-myristoylcarnitine are from Biotrend Chemicals; and d,l-acetylcarnitine is from Tocris Bioscience. The d,l-octanoylcarnitine was purchased from two different suppliers, Tocris Bioscience and Biotrend Chemicals. Biotrend Chemicals synthesize their compounds onsite in Germany, whereas Tocris Bioscience purchased the d,l-octanoylcarnitine from a producer in the United Kingdom (personal communication with technical staff at each company).

Octanoylcarnitine competition assay.

To determine if octanoylcarnitine inhibits growth on other acylcarnitines, P. aeruginosa PA14 was pregrown overnight at 37°C on a rotary wheel in 3 ml of MOPS medium with 20 mM pyruvate and 5 mM glucose added as carbon sources. Cells from the overnight culture were added at a final OD600 of 0.05 to MOPS medium with a 10 mM concentration of either acetylcarnitine or decanoylcarnitine as the carbon source. Octanoylcarnitine (Tocris Biosciences or Biotrend Chemicals) was added at 5 mM, and the cultures were incubated at 37°C overnight. Growth was assessed by OD600 on a Synergy 2 BioTek plate reader.

Expression and deletion constructs.

The PA5384 deletion construct was generated in the pMQ30 plasmid (27), and the deletion in P. aeruginosa PA14 was made by recombination as described previously (28, 29). Briefly, the upstream and downstream regions of the PA5384 gene were amplified by PCR from pMW79 using the primers PA5384-GOI-A (5′-aagcttGCCTGACCTTCCAGGACAT-3′), PA5384-SOE-A (5′-aagtacgaaggcgactcgaccatggGGCGAGGCAGGGTTCTAT-3′), PA5384-SOE-B (5′-ccatggtcgagtcgccttcgtacttCCGGAGACAGCGGATACTT-3′), and PA5384-GOI-B (5′-gaattcATTGCCCTGGACCTACCTG-3′). (Lowercase letters in sequences represent complementary regions for splice overlap extension or engineered restriction sites.) The splice overlap extension PCR product was cloned into the pCR-Blunt vector (Invitrogen), excised with HindIII and EcoRI, and cloned into similarly cut pMQ30 by E. coli-based cloning as described previously to generate pMW86. Donor E. coli S17/λpir, carrying the PA5384 deletion construct (pMW86), was mated with P. aeruginosa PA14, and single-crossover mutants were selected for growth on PIA plates with gentamicin. Recombinants were verified by PCR. Double-crossover events were selected by growth on 5% sucrose LB plates with no NaCl (28, 30).

The PA5384 expression vector (pJAM8) was made by amplifying PA5384 from the plasmid pMW79 (19) using primers 5384ET30a F (5′-ggatccGCTGCGAAGTATCCGCTGTCT-3′) and 5384ET30a R (5′-aagcttCTATTCGCCTGGCTGGTG-3′). This product was cloned into the pCR-Blunt vector using the Zero Blunt cloning kit (Invitrogen), with subsequent transformation and plasmid preparation as described above. The resulting plasmid was digested with HindIII and BamHI-HF (NEB), and the ∼1-kb fragment was extracted from an agarose gel and ligated into the similarly digested pET-30a expression vector (Novagen). The newly assembled plasmid, pJAM8, was transformed into chemically competent T7 Express competent E. coli (NEB C2566), and transformants were selected on LB with kanamycin.

trans-complementation of PA5384::Tn mutant strains.

To complement the PAO1 PA5384::Tn mutant strains (MJ206 and MJ207) (31), we placed the PA5384 gene at the attTn7 site under the control of the promoter regulating the native operon. The promoter of the carnitine catabolism operon (PA5388) was amplified from plasmid pMW79 using primers 5388promfor-5384F (5′-TAGCggtaccGGTTGAGGTTGCGCAGCC-3′) and 5388promfor5384R (5′-ATCAggatccCATCGGTCTCCCCTCGTG-3′). The 213-bp product was ligated into the pCR-Zero Blunt vector using the Zero Blunt cloning kit (Invitrogen), with subsequent transformation and plasmid preparation as described above. The resulting plasmid was digested with KpnI-HF and BamHI-HF (NEB), and the 213-bp fragment was extracted from an agarose gel and ligated into the similarly digested pJAM8 to generate pJAM61. The pJAM61 plasmid was digested with KpnI-HF and HindIII-HF, and the ∼1.2-kbp fragment was ligated into the similarly cut plasmid pUC18-mini-Tn7T-Gm (32) and transformed into chemically competent E. coli NEB5α. Transformants harboring the newly generated plasmid, pJAM62, were selected in the presence of 7 μg ml−1 gentamicin. The PA5388 promoter fused to PA5384 was integrated onto the chromosome of the PAO1 PA5384::Tn mutant strains as previously described (18, 32). Briefly, the plasmids pJAM62 and pTNS2 (33) were coelectroporated into each of the PAO1 PA5384::Tn mutant strains, and transformants were selected on 50 μg ml−1 gentamicin.

Expression and purification of PA5384.

Overnight cultures of JM17, which is T7 Express competent E. coli carrying pJAM8, in LB with 100 μg ml−1 of kanamycin, were inoculated into flasks containing 300 ml LB supplemented with 100 μg ml−1 of kanamycin and grown to an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4. The cultures were then induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM for 3 h at 37°C. Cells were collected by centrifugation, and the pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (B-PER; Thermo Scientific) at 4 ml per 1 g of cells. Halt protease inhibitor cocktail, EDTA-free 100× (Thermo) at 1× concentration, 150 mM NaCl, 2 μl ml−1 lysozyme (50 U ml−1; Thermo Scientific), and 2 μl ml−1 DNase (2,500 U ml−1; Thermo Scientific) were added to the culture, and it was incubated, with gentle shaking, at 37°C for 20 min. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The clarified lysate was applied to a HisPur cobalt-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) column (Thermo Scientific) and washed thoroughly with wash buffer 1 (10 mM imidazole, 50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM sodium chloride, pH 7.4) and wash buffer 2 (wash buffer 1 with 33 mM imidazole), and protein was eluted off the column with elution buffer (70 mM imidazole, 50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM sodium chloride, pH 7.4). The elution fractions containing N-terminal hexahistidine PA5384, determined by SDS-PAGE, were pooled and dialyzed in a 20,000-molecular-weight-cutoff (MWCO) Slide-A-Lyzer (Thermo Scientific) in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, and stored at 4°C. The protein concentration was determined to be 37 μg ml−1 by using bovine serum albumin standards in a Coomassie Plus–The Better Bradford assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Acetylcarnitine hydrolysis assay.

An assay developed to detect acetylcarnitine for a diagnostic application previously described by Tomita et al. (22) was modified for the purpose of detecting the enzymatic activity of the purified protein encoded by P. aeruginosa PA5384. The coupled assay of Tomita et al. was modified as follows. Purified 6×His-PA5384 in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, was added to the reaction mixture (0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, 7 mM MgSO4, 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM ATP, 0.5 M phosphoenolpyruvate, 0.3 mM NADH, 20 U ml−1 acetate kinase [Sigma], 9 U ml−1 pyruvate kinase [Sigma], and 4 U ml−1 l-lactate dehydrogenase [Sigma]) in a 96-well plate and incubated with shaking at 30°C (Synergy 2 BioTek) for 15 min. After this equilibration period, substrate (l-acetylcarnitine, d-acetylcarnitine, d,l-acetylcarnitine, or acetylcholine) was added to each well at 250 or 125 μM and incubated for an additional 3 h at 30°C. During this incubation, the absorbance was read at 340 nm every 3 min, with each read preceded by 15 s of shaking.

Hydrolysis reactions for other acylcarnitines and detection of enzymatic activity.

The substrate specificity of PA5384 was determined by detecting free l-carnitine using a colorimetric l-carnitine assay (BioVision). The assay was performed as described by the manufacturer with the modifications described here. First, in a 96-well plate, 15 μl of 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, was added to each well of l-carnitine standard and brought to a final volume of 50 μl with the provided assay buffer. In a 96-well plate, l-acylcarnitines with chain lengths of 2C to 4C were added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM, and d,l-acylcarnitines 6C to 16C were added to a final concentration of 1 mM in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2. The assay had technical triplicates and had more than three biological replicates for each carbon chain length. Subsequently, 0.5 μg of 6×His-PA5384 was added to each well and incubated at 30°C with shaking for 15 s every 3 min for 3.5 h. As a control, in triplicate, 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, and 0.5 mM acylcarnitine 2C to 4C or 1 mM acylcarnitine 6C to 16C were added to the assay to detect signal from free carnitine present in these compounds. Assay controls according to BioVision's protocols were also performed with the modification of adding 0.5 μg 6×His-PA5384 to the background control, which has no converting enzyme.

PA5384-FLAG tag and localization by Western blotting.

For Western blot analysis, PA5384 was C-terminally FLAG tagged via chromosomal integration by PCR amplifying the C terminus of PA5384 with primers 5384Flag F (5′-ggtaccGAGCAGCCCCTGGAGTTC-3′) and 5384Flag R (5′-aagcttCTACTTATCATCATCATCCTTGTAATCCGGCTTCAGGTTCATCCTG-3′), which contain the FLAG tag. The 585-bp product was cloned into the pCR-Blunt vector (Invitrogen) and excised with KpnI and HindIII. The excised product was cloned into similarly cut pMQ30 (27). Donor E. coli S17/λpir carrying the PA5384-FLAG construct, pJAM34, underwent conjugation with P. aeruginosa PA14, and single-crossover integrants were selected for growth on PIA plates with gentamicin. Recombinants were verified by growth in MOPS with 20 mM acetylcarnitine as a sole carbon source, supplemented with 20 μg ml−1 gentamicin, and by whole-lysate Western blotting using anti-FLAG monoclonal antibodies (Sigma). The Western blotting was performed by electrophoresis on 8 or 12% SDS-PAGE gels, followed by protein transfer to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore). The membrane was blocked overnight in 5% nonfat dried milk in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBS-T; 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1% Tween 20, 0.01% sodium azide, pH 7.6). The membrane was washed in TBS-T, incubated for 1 h with the anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma) or anti-SadB antibody (34), and washed in TBS-T before detection with anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase (HRP) secondary antibody (GE Healthcare) or anti-rabbit IgG IRDye 800CW (Odyssey). After washing with TBS-T, HRP was detected via the use of enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting detection reagent (GE Healthcare) prior to exposing the membrane to film.

PA5384-FLAG strains JM116 and JM117 and the control, JM141, were grown overnight to mid-log phase in MOPS with 5 mM glucose, 20 mM carnitine, and 15 μg ml−1 gentamicin. JM141 was used as a control to account for nonspecific binding of the anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody to an unrelated pMQ30 integrant (JM141 has a single-crossover integrant in PA4921, a gene irrelevant to the CDH pathway). Cells were collected by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was saved as the extracellular fraction. The pellets were resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.3, and lysed by repeated passage through a French press at 9,000 psi. The lysates were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 10 min to remove nonlysed cells and large cellular debris. Separation of membrane from the soluble fraction (cytoplasmic and periplasmic) was performed by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min. The whole-membrane fraction (outer and inner membrane) was resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.3, and washed three times. The soluble fraction was centrifuged at 100,000 × g three times to ensure no membrane contamination. The protein from the extracellular fraction was concentrated using a 10,000-MWCO Centriprep centrifugal filter (Millipore). The extracellular, soluble, and membrane fractions were then analyzed by Western blotting by following the protocol described above.

Osmoprotection assay.

Osmoprotection was determined by first growing P. aeruginosa PA14 wild-type (WT) and ΔPA5384 strains overnight at 37°C on a rotary wheel in 3 ml of MOPS medium with 20 mM pyruvate and 5 mM glucose. Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended to a final OD600 of 0.05 in MOPS (which contains 50 mM NaCl) with an additional 800 mM NaCl, 20 mM glucose, and 0.2 mM carnitine or acetylcarnitine in 48-well plates. Cultures were grown at 37°C for 48 h due to the low growth rate in a high-salt medium, and growth was determined by OD600.

plcH promoter activity by means of lacZYA fusion.

Transcriptional induction from the plcH promoter was measured as previously described (35). Briefly, the plcH-lacZYA reporter construct, pMW22 (35), was transformed by electroporation into P. aeruginosa PA14 WT and ΔPA5384 strains, and transformants were selected for growth on gentamicin. Cells were grown overnight in MOPS with 20 mM pyruvate, 5 mM glucose, and 20 μg ml−1 gentamicin. Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in MOPS with 20 mM pyruvate and 20 μg ml−1 gentamicin, with the addition of 1 mM carnitine or acetylcarnitine for induction samples. Cells were induced for 5.5 h at 37°C, and β-galactosidase assays were performed according to the method of Miller (36).

NPPC assay.

Phospholipase C (PLC) activity was measured by p-nitrophenylphosphorylcholine (NPPC) hydrolysis according to the method of Kurioka and Matsuda (37), as previously modified in our laboratory (18, 35). Briefly, cells were grown overnight in MOPS, 20 mM pyruvate, and 5 mM glucose. Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in MOPS with 20 mM pyruvate and 1 mM carnitine or acetylcarnitine and grown overnight at 37°C in a 48-well plate. Supernatants from these cultures were obtained and added to 2× reaction buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 50% glycerol, 20 mM NPPC) in a 1:1 ratio. Hydrolysis of NPPC was quantified by measuring absorbance at 410 nm using the extinction coefficient 17,700 M−1 cm−1.

RESULTS

PA5384 is required for growth on acetylcarnitine.

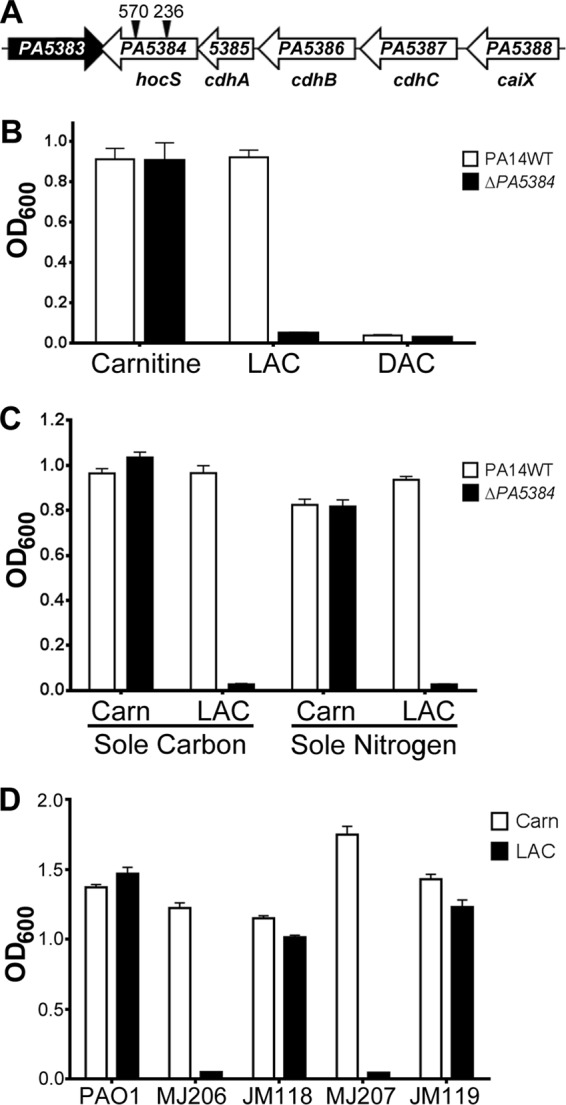

We previously demonstrated that the first four genes in the caiX-cdhCAB-PA5384 (PA5388 to PA5384) operon (Fig. 1A) were critical for aerobic carnitine transport and metabolism (19, 38). PA5384, the last gene in the operon, was not required for carnitine catabolism (19). We hypothesized that PA5384 is associated with acylcarnitine catabolism based on its presence in the carnitine catabolism operon and bioinformatic prediction of lipase/esterase function. To determine the function of PA5384, we made an unmarked deletion of PA5384 (ΔPA5384) in P. aeruginosa PA14 and measured growth on acetylcarnitine. The PA5384 deletion mutant was unable to grow on acetylcarnitine as a sole carbon source (Fig. 1B). To test whether P. aeruginosa could use either acetylcarnitine stereoisomer, we used both the l- and d-enantiomers of acetylcarnitine in a growth assay and found that P. aeruginosa can only grow on the l-enantiomer of acetylcarnitine (Fig. 1B). It has been shown that carnitine can be used as a sole nitrogen source (23), and we tested if acetylcarnitine can be used as a sole nitrogen source. P. aeruginosa PA14 can grow on acetylcarnitine as the sole nitrogen source, whereas the ΔPA5384 deletion strain cannot (Fig. 1C).

Fig 1.

PA5384 is required for P. aeruginosa growth on l-acetylcarnitine. (A) Diagram of the carnitine catabolism operon in P. aeruginosa PAO1. ORFs are shown as arrows and are scaled relative to other ORFs. Black triangles represent transposon insertion sites in two separate PAO1 PA5384 mutant strains, with the position of the insertion noted by base pair numbers above the triangle. Gene designations are given below the arrows (19, 38), along with our proposed gene name for PA5384. (B) PA14 WT and ΔPA5384 mutant cells were grown in MOPS minimal media supplemented with 20 mM carnitine, l-acetylcarnitine (LAC), or d-acetylcarnitine (DAC). (C) PA14 WT and ΔPA5384 mutant cells were grown in MOPS minimal media or MOPS minimal media without nitrogen supplemented with 20 mM carnitine (Carn) or l-acylcarnitine (LAC) as the sole carbon and nitrogen source. (D) Transcomplementation of two independent PAO1 PA5384 transposon mutants. Cells were incubated in MOPS minimal media with 20 mM carnitine or LAC. MJ206 is the strain designation for the PA5384::Tn mutant strain with the transposon insertion at bp 570, and the derivative attTn7::PA5384 mutant strain is designated JM118. MJ207 is the strain designation for the PA5384::Tn mutant with the transposon insertion at bp 236, and the derived attTn7::PA5384 strain is designated JM119. Error bars represent standard deviations from three replicates, and results are representative of three independent experiments.

We were unable to complement the acetylcarnitine growth defect of the PA5384 deletion strain using a high-copy-number constitutive plasmid (PA5384 on the pUCP22 backbone) or using an arabinose-inducible high-copy-number system (PA5384 under PBAD control on the pMQ80 backbone). Therefore, to test if the growth phenotype in the PA5384 mutant strain was due to mutation of PA5384, we constructed a PA5388 (caiX) promoter fusion with PA5384 (PcaiX-PA5384) and integrated it onto the chromosome at the attTn7 site in two independent PAO1 transposon mutant strains. The two PAO1 transposon mutants, MJ207 and MJ206, carry a Tn5 transposon that confers resistance to tetracycline inserted into the PA5384 coding sequence at base pairs 236 and 570, respectively (Fig. 1A) (31). Both strains carrying PcaiX-PA5384 at the attTn7 site (JM118 and JM119) were able to grow on acetylcarnitine as a sole carbon source (Fig. 1D). These data confirm the necessity of PA5384 for growth on acetylcarnitine.

PA5384 exhibits acetylcarnitine hydrolase activity.

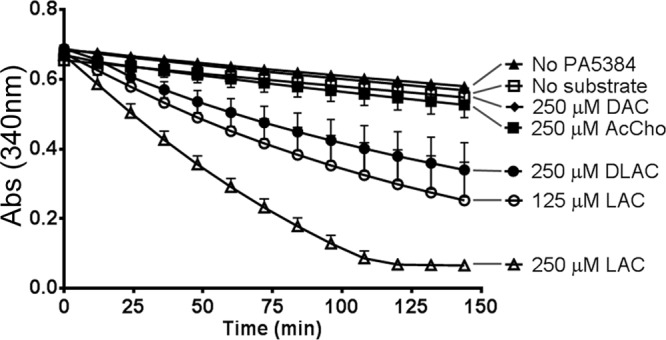

P. aeruginosa requires PA5384 for growth on acetylcarnitine (Fig. 1). To determine if PA5384 encoded an acetylcarnitine hydrolase, we expressed recombinant PA5384 protein with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag (6×His) and purified it by cobalt affinity chromatography and dialysis as described in Materials and Methods. To measure the acetylcarnitine hydrolase activity of PA5384, we adapted an enzymatic method designed to measure acetylcarnitine in serum (22), which uses four coupled enzymatic reactions to convert acetate abundance to an increase in NAD+ concentration, resulting in decreased UV absorbance at 340 nm dependent upon acetate. We predicted that PA5384 was an acetylcarnitine hydrolase that would hydrolyze acetylcarnitine to carnitine and acetate and allow detection of acetate using the coupled reaction system. Using this assay, we showed that PA5384 has l-enantiomer-specific acetylcarnitine hydrolase activity, as it hydrolyzes l-acetylcarnitine and not d-acetylcarnitine (Fig. 2). The specificity of PA5384 was examined further by determining if the presence of the carnitine backbone of acetylcarnitine was necessary for hydrolysis. The inability of PA5384 to hydrolyze acetylcholine, which is another quaternary amine-containing ester, to choline and acetate suggests that the carnitine backbone is necessary for acetylcarnitine hydrolysis and that PA5384 is not a general hydrolase (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

PA5384 can hydrolyze l-acetylcarnitine. Coupled enzymatic assays were performed with purified 6×His-PA5384 and either no substrate or one the following substrates: 250 μM l-acetylcarnitine (LAC), 125 μM LAC, 250 μM d-acetylcarnitine (DAC), 250 μM d,l-acetylcarnitine (DLAC), 250 μM acetylcholine (AcCho), or (▲) 250 μM LAC with no added PA5384. Lines have been added from the key to the absorbance (Abs) curves to clarify the line identities. Error bars represent standard deviations from triplicate samples, and results are representative of three separate experiments.

PA5384 has specificity for short-chain acylcarnitines.

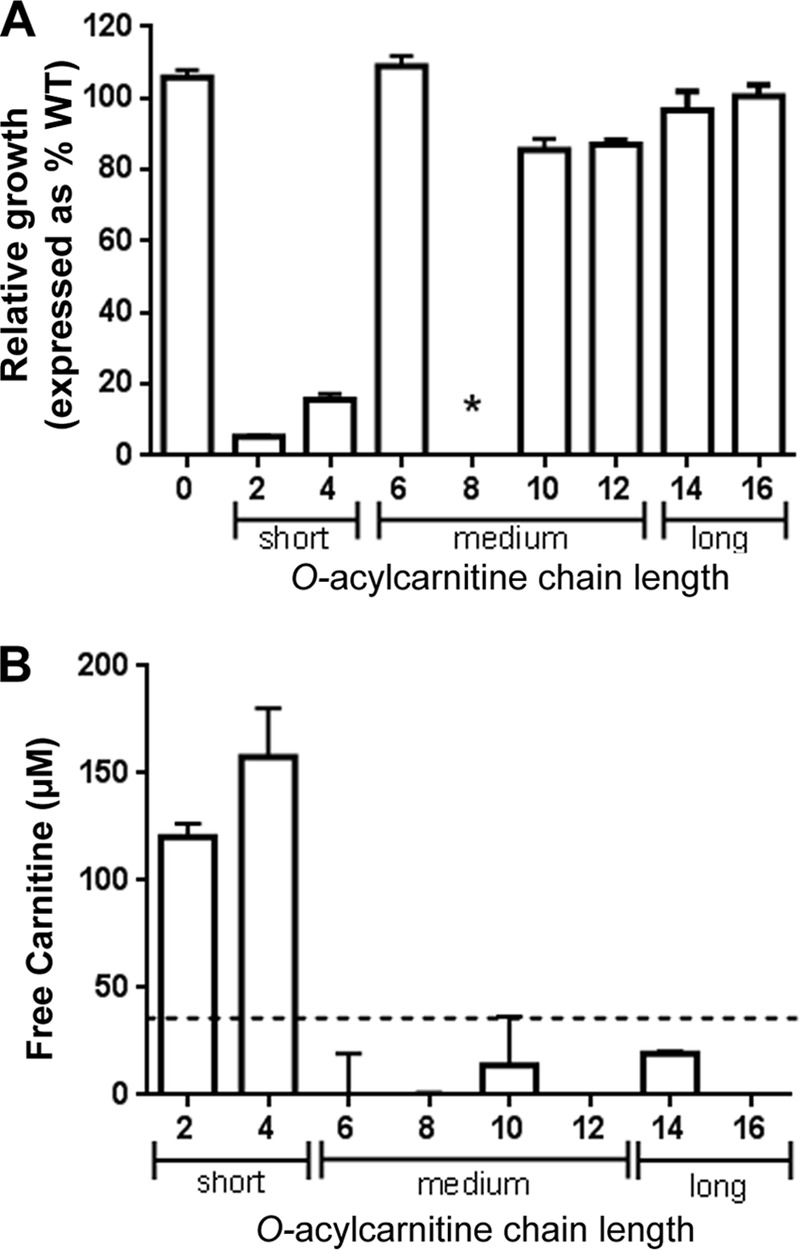

As demonstrated above, PA5384 is required for growth on acetylcarnitine and purified 6×His-PA5384 hydrolyzes acetylcarnitine in vitro. In the infection environment, P. aeruginosa encounters a variety of acylcarnitines with different O-acyl chain lengths. To determine whether PA5384 was required for growth on O-acyl chain lengths longer than those of acetylcarnitine, we compared the PA14 wild type to a ΔPA5384 mutant strain for growth on acylcarnitines with chain lengths of 2C to 16C. Here, we show that PA5384 is required for growth on short-chain acylcarnitines (2C and 4C) but not for growth on medium- or long-chain acylcarnitines (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, P. aeruginosa cannot use octanoylcarnitine as a sole carbon source (Fig. 3A), nor does octanoylcarnitine inhibit growth on acetylcarnitine and decanoylcarnitine as the sole carbon sources (data not shown). This observation will be addressed in Discussion.

Fig 3.

PA5384 encodes a short-chain acylcarnitine hydrolase. (A) PA14 WT and the ΔPA5384 mutant were grown in MOPS minimal medium with 20 mM carnitine (0) or 2C to 16C acylcarnitine. The number on the x axis indicates chain length. The y axis shows relative growth of the mutant compared to that of the WT, expressed as a percentage of WT growth (i.e., WT growth = 100%). Growth for carnitine to acylcarnitines with 12C chain lengths was measured by OD600, and growth on acylcarnitines with chain lengths of 14C and 16C was determined by serial dilution and plating. An asterisk indicates that neither the PA14 WT nor the ΔPA5384 mutant strain grew on octanoylcarnitine as the sole carbon source. (B) Free l-carnitine generated from hydrolysis of acylcarnitines by 6×His-PA5384 was detected using a colorimetric l-carnitine assay. The dotted line represents the assay sensitivity limit, below which measurements of carnitine are not reliable. Error bars represent standard deviations from triplicate samples, and results are representative of three separate experiments.

We sought to determine if the chain length specificity for the observed growth phenotype was due to enzymatic specificity of PA5384. To test the in vitro hydrolysis of different acylcarnitines by PA5384, we measured l-carnitine release using a colorimetric assay for l-carnitine detection (BioVision). Each acylcarnitine, from 2C to 16C, was assayed for free l-carnitine either in the presence or absence of purified 6×His-PA5384. The samples with no PA5384 enzyme added allowed for subtraction of contaminating free l-carnitine from the starting materials. The results show that PA5384 can hydrolyze the short-chain acylcarnitines, acetyl and butyryl, but it has no activity on medium-chain and long-chain acylcarnitines (Fig. 3B). Based on the l-carnitine assay described above and our genetic evidence, PA5384 will now be referred to as HocS (for hydrolase of O-acylcarnitine, short chains), with hocS being the corresponding gene name for PA5384.

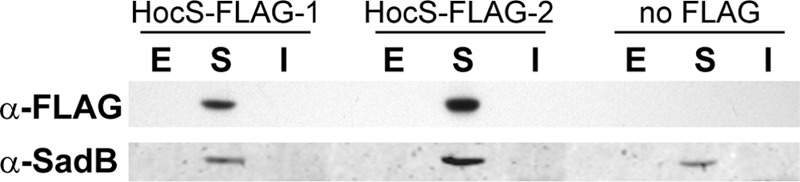

HocS is located in the cytoplasm.

HocS was bioinformatically predicted to be in the cytoplasm using the PSORTb database, v3.0, with a cytoplasmic score of 9.97, well above the accepted cutoff of 7.5 (39, 40). To confirm this prediction, we tracked the localization of a chromosomally incorporated C-terminally FLAG-tagged HocS. Cells with the hocS-FLAG allele were grown in carnitine to induce expression (19). Western blot analysis was performed on the extracellular, soluble, and insoluble fractions, and HocS-FLAG was detected by use of an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Fig. 4) compared to the untagged HocS control. A known cytoplasmic protein, SadB, was used as a control for cytoplasmic localization as well as cytoplasmic contamination in the extracellular and insoluble fractions using the anti-SadB antibody (34). Based on these data, HocS is most likely cytoplasmic, although these data do not conclusively exclude periplasmic localization.

Fig 4.

HocS likely is localized to the cytoplasm. Cells from two independent strains, HocS-FLAG-1 (JM116) and HocS-FLAG-2 (JM117), that integrate a C-terminal FLAG tag on HocS, and control strain JM141 were grown in carnitine. The extracellular (E), soluble (S), and insoluble fractions (I) were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. After SDS-PAGE and blotting, the FLAG tag was detected with a monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody, and the cytoplasmic control, SadB, was detected with an anti-SadB antibody. The Western blot shown is a representative of four comparable blots.

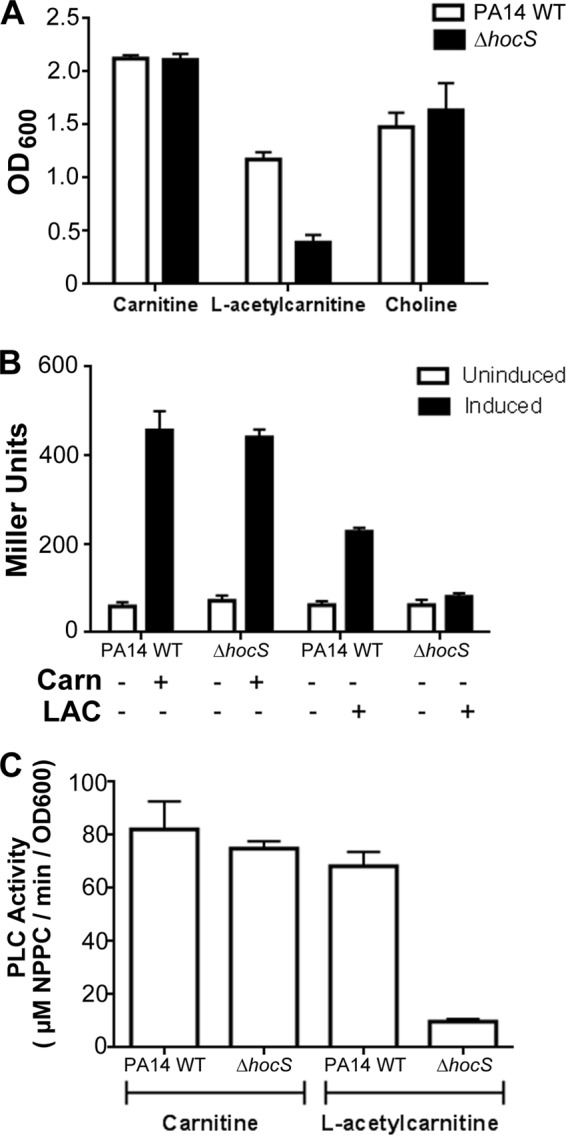

HocS is important for osmoprotection and induction of the virulence factor PlcH.

Carnitine is known to be an osmoprotectant (8) and to induce PLC activity (8). The ability of HocS to liberate carnitine from short-chain acylcarnitines led us to predict its involvement in osmoprotection and PlcH activity under conditions where short-chain acylcarnitines were present. To determine if hocS has a role in osmoprotection, we compared the PA14 wild type to the hocS deletion strain for the ability to grow in the presence of 850 mM NaCl. Under these conditions, carnitine functions as an osmoprotectant allowing for growth in the wild type and the ΔhocS mutant strain (Fig. 5A). Osmoprotection was also observed with acetylcarnitine as the osmoprotectant source in the PA14 wild type but not in the ΔhocS mutant strain, which had a 3-fold decrease in growth compared to the level of the wild type (Fig. 5A). Choline is oxidized to glycine betaine, a potent osmoprotectant (9), and was used as a control to show that deleting hocS did not compromise the choline catabolic pathway or general osmoprotection. These results support two conclusions. First, acetylcarnitine is not an effective osmoprotectant prior to hydrolysis, and second, hydrolysis of acetylcarnitine by HocS can provide osmoprotection in hyperosmotic environments.

Fig 5.

HocS has a role in osmoprotection and induction of the virulence factor plcH. (A) Osmoprotection was determined by growing PA14 WT and ΔhocS mutant cells for 48 h in MOPS minimal medium (50 mM NaCl) supplemented with 800 mM NaCl, 20 mM glucose as the carbon source, and the compatible solute, carnitine or l-acetylcarnitine (LAC), at a final concentration of 0.2 mM. (B) Induction of plcH-lacZYA (pMW22) by carnitine (Carn) or LAC was measured by inducing PA14 WT and ΔhocS mutant strain cells for 4 h prior to the β-galactosidase assay. (C) To measure PLC activity, PA14 WT and ΔhocS mutant cells were grown overnight in MOPS supplemented with 20 mM pyruvate and either 1 mM carnitine or LAC. The resultant culture supernatants were used in an NPPC assay to determine PLC activity. Error bars represent standard deviations from triplicate samples, and results are representative of three separate experiments.

Release of carnitine by HocS activity would also be predicted to impact plcH transcription and PLC enzyme production by supplying glycine betaine for GbdR-dependent induction of plcH. To test this prediction, we measured plcH transcription using a plasmid-based plcH-lacZYA reporter (pMW22) (35) and measured PLC enzymatic activity using the NPPC assay (37). Carnitine induced transcription of plcH, as previously reported (35), in both the PA14 wild-type and ΔhocS mutant strains. However, in the ΔhocS mutant strain, acetylcarnitine showed no plcH transcriptional induction, whereas the PA14 wild type showed robust induction (Fig. 5B). Activity of secreted PLC was determined for both the PA14 wild-type and ΔhocS mutant strains using the NPPC assay. A 7-fold increase in PLC activity induced by acetylcarnitine was observed in the PA14 wild type compared to the ΔhocS mutant (Fig. 5C). These results demonstrate that hocS hydrolysis of acetylcarnitine is required for acetylcarnitine-dependent induction of plcH transcription and PlcH activity.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified HocS (PA5384) as a short-chain acylcarnitine hydrolase that is required for P. aeruginosa to utilize acetyl- and butyrylcarnitine as sole carbon, nitrogen, and energy sources. Using a coupled enzymatic assay, we show that HocS is specific for acylcarnitines, and, in conjunction with the l-carnitine assay, we demonstrate that HocS specifically hydrolyzes short-chain acylcarnitines. The free carnitine generated can induce plcH transcription and result in induced PLC activity. P. aeruginosa can also utilize the rendered carnitine as an osmoprotectant to promote growth under hyperosmotic conditions. Through trans-complementation we were able to show that hocS is required for P. aeruginosa to grow on acetylcarnitine. We speculate that plasmid complementation was not successful due to the concentration of HocS being higher than those of the other carnitine dehydrogenase proteins.

Acylcarnitine degradation has only been evaluated in Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas fluorescens (23, 41), which led us to inquire if P. aeruginosa can utilize acylcarnitines as sole carbon and nitrogen sources. In humans, acetylcarnitine is the most prevalent acylcarnitine intracellularly and in circulation, but medium- and long-chain acylcarnitines are also present throughout the body, with long-chain acylcarnitines being the dominant acylcarnitine in bile (1). P. putida cannot utilize acylcarnitines with chain lengths of 2C to 8C, but it is capable of using acylcarnitines with chain lengths of 10C and longer as a sole carbon source (23). This led us to hypothesize that P. aeruginosa can utilize longer-chain-fatty-acid acylcarnitines as well. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to show that P. aeruginosa can utilize acylcarnitines with chain lengths of 2C to 16C as sole carbon and nitrogen sources (Fig. 1C and 3A). Interestingly, our data illustrate that P. aeruginosa cannot use octanoylcarnitine as a sole carbon source and that octanoylcarnitine does not inhibit growth on either acetyl- or decanoylcarnitine. The failure to grow on octanoylcarnitine may be due to an inability to transport or hydrolyze octanoylcarnitine, either or both of which suggest that P. aeruginosa is specifically restricted in its use of octanoylcarnitine (Fig. 3A). We used two different sources of octanoylcarnitine that were manufactured at two different sites (United Kingdom and Germany) to rule out toxic contaminants and defective synthesis, so we think that this restriction is a biological one, although we do not know the mechanism governing this restriction. P. fluorescens strain IMAM, on the other hand, can hydrolyze l-octanoylcarnitine (41), but no study to date has shown growth on octanoylcarnitine as the sole carbon source in the pseudomonads.

Takahashi and others demonstrated, through crude purification, that an acylcarnitine hydrolase from Alcaligenes could be employed effectively to identify acetylcarnitine in biological samples (22, 42, 43). However, the gene responsible for the acetylcarnitine hydrolase activity in Alcaligenes was not determined. We successfully identified the gene and expressed the protein responsible for hydrolysis of short-chain acylcarnitines in P. aeruginosa, PA5384 (HocS), and determined that it is likely localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4). Data from the l-carnitine assay further illustrate that hocS only hydrolyzes the short-chain acylcarnitines acetyl- and butyrylcarnitine (Fig. 3B). Since hocS hydrolyzes only substrates with a carnitine backbone, it suggests that an accessible fatty acid alone is not sufficient to achieve hydrolase activity, and that the hydrolase activity is specific to the bond position on carnitine, which is further supported by the enantiomeric selectivity of the enzyme. These data, and the ability of the ΔhocS mutant strain to grow on medium- or long-chain acylcarnitines as the sole carbon source, suggest that P. aeruginosa possesses an alternate hydrolase(s) that can liberate carnitine from medium- and long-chain acylcarnitines.

An additional goal of this study was to determine if short-chain acylcarnitines have a physiological role in P. aeruginosa in addition to their use as nutrient sources. The virulence factor PlcH is induced by phosphate deprivation and by the products of choline and carnitine catabolism, glycine betaine and dimethylglycine (8, 44, 45). As access to carnitine enables induction of plcH, we hypothesized that the free carnitine generated by HocS hydrolysis of short-chain acylcarnitines would provide a source of carnitine to induce plcH. The lack of induction in either plcH transcription or PLC activity in the ΔhocS mutant in the presence of acetylcarnitine leads us to conclude that the carnitine generated from hydrolysis of short-chain acylcarnitines by HocS is sufficient to induce plcH expression (Fig. 5B and C).

The ability of P. aeruginosa to survive under hyperosmotic conditions by employing quaternary amine osmoprotectants, such as choline-O-sulfate, carnitine, and glycine betaine, has long been established (1, 8). Even though acylcarnitines had not been evaluated in P. aeruginosa as osmoprotectants, our data show that free carnitine generated by HocS hydrolysis acts as an osmoprotectant for P. aeruginosa under hyperosmotic conditions, but that acetylcarnitine itself is not an osmoprotectant (Fig. 5A). In Bacillus subtilis, acetylcarnitine is a precursor to carnitine, which is then used as an osmoprotectant (46). In Listeria monocytogenes, acetylcarnitine functions as an osmoprotectant (47, 48), but these studies did not address if acetylcarnitine is catabolized to carnitine. P. aeruginosa has been shown to catabolize carnitine to glycine betaine in hyperosmotic environments (46). Short-chain acylcarnitines are a source of carnitine that can ultimately be converted to glycine betaine.

This study has expanded our knowledge on P. aeruginosa acylcarnitine catabolism. Similar to P. putida, P. aeruginosa can grow on acylcarnitines of 10- to 16-carbon chain lengths, but P. aeruginosa is additionally capable of utilizing acylcarnitines with 2- to 6-carbon chain lengths. P. aeruginosa hydrolyzes short-chain acylcarnitines using an l-enantiomer-specific hydrolase we have described here, HocS. The liberated carnitine from short-chain acylcarnitine hydrolysis has multiple physiological impacts, including induction of virulence factors and providing access to osmoprotectants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Heather Bean (University of Vermont) for technical advice and George O'Toole (Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College) for generously providing us with the anti-SadB antibody.

This project was supported by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (5P20RR021905-07) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20 GM103496 and P30 GM103532) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 March 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Rebouche CJ, Seim H. 1998. Carnitine metabolism and its regulation in microorganisms and mammals. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 18: 39–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bremer J. 1983. Carnitine-metabolism and functions. Physiol. Rev. 63: 1420–1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fritz IB. 1963. Carnitine and its role in fatty acid metabolism. Adv. Lipid Res. 1: 285–334 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aurich H, Kleber HP, Schopp WD. 1967. An inducible carnitine dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 139: 505–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aurich H, Lorenz I. 1959. On the catabolism of carnitine by Pseudomonas pyocyanea. Acta Biol. Med. Ger. 3: 272–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rebouche CJ. 1992. Carnitine function and requirements during the life cycle. FASEB J. 6: 3379–3386 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Uanschou C, Frieht R, Pittner F. 2005. What to learn from a comparative genomic sequence analysis of l-carnitine dehydrogenase. Monatsh. Chem. 136: 1365–1381 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lucchesi GI, Lisa TA, Casale CH, Domenech CE. 1995. Carnitine resembles choline in the induction of cholinesterase, acid phosphatase, and phospholipase C and in its action as an osmoprotectant in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Curr. Microbiol. 30: 55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. D'Souza-Ault MR, Smith LT, Smith GM. 1993. Roles of N-acetylglutaminylglutamine amide and glycine betaine in adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to osmotic stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59: 473–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vasil ML, Vasil AI, Shortridge VD. 1994. Phosphate in microorganisms: cellular and molecular biology. In Torriani-Gorrini EY, Silver S. (ed), Phosphate and osmoprotectants in the pathogenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kunin CM, Hua TH, Van Arsdale White L, Villarejo M. 1992. Growth of Escherichia coli in human urine: role of salt tolerance and accumulation of glycine betaine. J. Infect. Dis. 166: 1311–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gilljam H, Ellin A, Strandvik B. 1989. Increased bronchial chloride concentration in cystic fibrosis. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest 49: 121–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berk RS, Brown D, Coutinho I, Meyers D. 1987. In vivo studies with two phospholipase C fractions from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 55: 1728–1730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meyers DJ, Berk RS. 1990. Characterization of phospholipase C from Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a potent inflammatory agent. Infect. Immun. 58: 659–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Terada LS, Johansen KA, Nowbar S, Vasil AI, Vasil ML. 1999. Pseudomonas aeruginosa hemolytic phospholipase C suppresses neutrophil respiratory burst activity. Infect. Immun. 67: 2371–2376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ostroff RM, Vasil AI, Vasil ML. 1990. Molecular comparison of a nonhemolytic and a hemolytic phospholipase C from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 172: 5915–5923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wiener-Kronish JP, Sakuma T, Kudoh I, Pittet JF, Frank D, Dobbs L, Vasil ML, Matthay MA. 1993. Alveolar epithelial injury and pleural empyema in acute P. aeruginosa pneumonia in anesthetized rabbits. J. Appl. Physiol. 75: 1661–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wargo MJ, Gross MJ, Rajamani S, Allard JL, Lundblad LK, Allen GB, Vasil ML, Leclair LW, Hogan DA. 2011. Hemolytic phospholipase C inhibition protects lung function during Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 184: 345–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wargo MJ, Hogan DA. 2009. Identification of genes required for Pseudomonas aeruginosa carnitine catabolism. Microbiology 155: 2411–2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Winsor GL, Lam DK, Fleming L, Lo R, Whiteside MD, Yu NY, Hancock RE, Brinkman FS. 2011. Pseudomonas Genome Database: improved comparative analysis and population genomics capability for Pseudomonas genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 39: D596–D600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Takahashi M, Ueda S. January 1995. Method of assaying for acyl-l-carnitine and short-chain acyl-carnitine. US patent 5,385,829

- 22. Tomita K, Sakurada S, Minami S. 2001. Enzymatic determination of acetylcarnitine for diagnostic applications. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 24: 1147–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kleber HP, Seim H, Aurich H, Strack E. 1978. Interrelationships between carnitine metabolism and fatty acid assimilation in Pseudomonas putida. Arch. Microbiol. 116: 213–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rahme LG, Stevens EJ, Wolfort SF, Shao J, Tompkins RG, Ausubel FM. 1995. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science 268: 1899–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin AL, Mizoguchi SD, Warrener P, Hickey MJ, Brinkman FS, Hufnagle WO, Kowalik DJ, Lagrou M, Garber RL, Goltry L, Tolentino E, Westbrock-Wadman S, Yuan Y, Brody LL, Coulter SN, Folger KR, Kas A, Larbig K, Lim R, Smith K, Spencer D, Wong GK, Wu Z, Paulsen IT, Reizer J, Saier MH, Hancock RE, Lory S, Olson MV. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406: 959–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. LaBauve AE, Wargo MJ. 2012. Growth and laboratory maintenance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 6: Unit 6E.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shanks RM, Caiazza NC, Hinsa SM, Toutain CM, O'Toole GA. 2006. Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based molecular tool kit for manipulation of genes from gram-negative bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72: 5027–5036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schweizer HD. 1993. Small broad-host-range gentamycin resistance gene cassettes for site-specific insertion and deletion mutagenesis. Biotechniques 15: 831–834 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wargo MJ, Szwergold BS, Hogan DA. 2008. Identification of two gene clusters and a transcriptional regulator required for Pseudomonas aeruginosa glycine betaine catabolism. J. Bacteriol. 190: 2690–2699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Choi KH, Schweizer HP. 2005. An improved method for rapid generation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa deletion mutants. BMC Microbiol. 5: 30 doi:10.1186/1471-2180-5-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jacobs MA, Alwood A, Thaipisuttikul I, Spencer D, Haugen E, Ernst S, Will O, Kaul R, Raymond C, Levy R, Chun-Rong L, Guenthner D, Bovee D, Olson MV, Manoil C. 2003. Comprehensive transposon mutant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100: 14339–14344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Choi KH, Schweizer HP. 2006. Mini-Tn7 insertion in bacteria with single attTn7 sites: example Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat. Protoc. 1: 153–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Choi KH, Gaynor JB, White KG, Lopez C, Bosio CM, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Schweizer HP. 2005. A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat. Methods 2: 443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Caiazza NC, O'Toole GA. 2004. SadB is required for the transition from reversible to irreversible attachment during biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol. 186: 4476–4485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wargo MJ, Ho TC, Gross MJ, Whittaker LA, Hogan DA. 2009. GbdR regulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa plcH and pchP transcription in response to choline catabolites. Infect. Immun. 77: 1103–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kurioka S, Matsuda M. 1976. Phospholipase C assay using p-nitrophenylphosphoryl-choline together with sorbitol and its application to studying the metal and detergent requirement of the enzyme. Anal. Biochem. 75: 281–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen C, Malek AA, Wargo MJ, Hogan DA, Beattie GA. 2010. The ATP-binding cassette transporter Cbc (choline/betaine/carnitine) recruits multiple substrate-binding proteins with strong specificity for distinct quaternary ammonium compounds. Mol. Microbiol. 75: 29–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rey S, Acab M, Gardy JL, Laird MR, deFays K, Lambert C, Brinkman FS. 2005. PSORTdb: a protein subcellular localization database for bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 33: D164–D168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yu NY, Laird MR, Spencer C, Brinkman FS. 2011. PSORTdb-an expanded, auto-updated, user-friendly protein subcellular localization database for Bacteria and Archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 39: D241–D244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Aragozzini F, Manzoni M, Cavazzoni V, Craveri R. 1986. d,l-carnitine resolution by Fusarium oxysporum. Biotechnol. Lett. 8: 95–98 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Matsumoto K, Takahashi M, Takiyama N, Misaki H, Matsuo N, Murano S, Yuki H. 1993. Enzyme reactor for urinary acylcarnitines assay by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Clin. Chim. Acta 216: 135–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Takahashi M, Ueda S. October 1991. Acyl-carnitine-esterase, method for measuring acylcarnitine. Japanese patent 91309212.8

- 44. Sage AE, Vasil AI, Vasil ML. 1997. Molecular characterization of mutants affected in the osmoprotectant-dependent induction of phospholipase C in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Mol. Microbiol. 23: 43–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sage AE, Vasil ML. 1997. Osmoprotectant-dependent expression of plcH, encoding the hemolytic phospholipase C, is subject to novel catabolite repression control in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 179: 4874–4881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kappes RM, Bremer E. 1998. Response of Bacillus subtilis to high osmolarity: uptake of carnitine, crotonobetaine and gamma-butyrobetaine via the ABC transport system OpuC. Microbiology 144: 83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bayles DO, Wilkinson BJ. 2000. Osmoprotectants and cryoprotectants for Listeria monocytogenes. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 30: 23–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Verheul A, Rombouts FM, Beumer RR, Abee T. 1995. An ATP-dependent L-carnitine transporter in Listeria monocytogenes Scott A is involved in osmoprotection. J. Bacteriol. 177: 3205–3212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schweizer HP. 1991. Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19. Gene 97: 109–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]