Abstract

The Staphylococcus aureus cid and lrg operons play significant roles in the control of autolysis and accumulation of extracellular genomic DNA (eDNA) during biofilm development. Although the molecular mechanisms mediating this control are only beginning to be revealed, it is clear that cell death must be limited to a subfraction of the biofilm population. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that cid and lrg expression varies during biofilm development as a function of changes in the availability of oxygen. To examine cid and lrg promoter activity during biofilm development, fluorescent reporter fusion strains were constructed and grown in a BioFlux microfluidic system, generating time-lapse epifluorescence images of biofilm formation, which allows the spatial and temporal localization of gene expression. Consistent with cid induction under hypoxic conditions, the cid::gfp fusion strain expressed green fluorescent protein predominantly within the interior of the tower structures, similar to the pattern of expression observed with a strain carrying a gfp fusion to the hypoxia-induced promoter controlling the expression of the lactose dehydrogenase gene. The lrg promoter was also expressed within towers but appeared more diffuse throughout the tower structures, indicating that it was oxygen independent. Unexpectedly, the results also demonstrated the existence of tower structures with different expression phenotypes and physical characteristics, suggesting that these towers exhibit different metabolic activities. Overall, the findings presented here support a model in which oxygen is important in the spatial and temporal control of cid expression within a biofilm and that tower structures formed during biofilm development exhibit metabolically distinct niches.

INTRODUCTION

The existence of pronounced death and lysis during bacterial biofilm development has led to the proposal that these relatively simple organisms have the capacity to control cell viability in a process analogous to apoptosis in more complex eukaryotic organisms (1, 2). A key function of these processes, referred to as bacterial programmed cell death (PCD), is likely to release genomic DNA into the biofilm matrix, where it serves as an effective intercellular adherence molecule. The importance of extracellular DNA (eDNA) as a matrix molecule was originally demonstrated in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (3) and has since been shown to be important for biofilms produced by a wide range of bacterial species (3–9). Although some reports suggest the involvement of bacteriophage in DNA release during biofilm development (9–12), the presence of distinct regions of cell death and lysis indicates that this process is highly regulated (4, 6, 9, 13).

Insight into the molecular mechanisms controlling PCD has come from studies of the Staphylococcus aureus cidABC and lrgAB operons, which were originally characterized as mediators of murein hydrolase activity and lysis (14–16). The mode of action of their gene products has been hypothesized to involve a mechanism analogous to the holin-antiholin-mediated control of host cell lysis during bacteriophage infection (1, 17). A role for these operons during biofilm development was demonstrated by the observations that cid and lrg mutations affect biofilm formation, disrupting the normal architecture that is a characteristic of these multicellular communities (6, 7). Additionally, it was established that the cid mutant produced biofilm with reduced levels of matrix-associated eDNA, while the lrg mutant exhibited increased levels of this matrix component (6). Similar effects on biofilm development were also produced by P. aeruginosa in which homologues of cid and lrg had been disrupted (18). These results suggest the existence of a careful balance between death effectors and inhibitors in normal biofilm, not unlike that proposed to control normal tissue homeostasis in more complex developmental organisms (2). Moreover, they support the notion that this mechanism is conserved in other bacterial species.

Recent evidence also suggests that Cid/Lrg-like proteins are conserved much more broadly than was originally recognized. Recent studies of a putative Arabidopsis CidAB/LrgAB homolog, designated AtLrgB, indicated that the gene that encodes it is an important regulator of cell death in plants (19, 20). Disruption of the gene encoding AtLrgB produced plants with interveinal chlorotic and premature necrotic leaves, suggesting the involvement of this protein in leaf senescence. Furthermore, recent studies (21) also support the model in which the mammalian Bcl-2 family of proteins functions in a manner analogous to that of holins and antiholins. Strikingly, these studies demonstrated that the death effector and inhibitor components of the Bcl-2 protein family can induce cell death and lysis in Escherichia coli, similar to holins and antiholins, respectively. Indeed, replacement of the normal holin of bacteriophage lambda with derivatives of the human Bax protein resulted in the formation of functional, plaque-forming viral particles. These results suggest that the functions of the Cid and Lrg proteins span at least three biological kingdoms.

It is clear that any model of controlled cell death and lysis during biofilm development must accommodate the observation that only a subpopulation of cells undergoes this process. Structured biofilms exhibit obvious spatial differences in cell viability and lysis, including localized dead cell and eDNA staining in towers and more homogeneous live cell populations in the basal biofilm (4, 6, 9, 13). This has led us to hypothesize that the differential expression of cell death and lysis within biofilm subpopulations is dictated by the heterogeneous expression of the cid and lrg operons within the biofilm (1, 2), possibly as a result of the metabolic heterogeneity commonly observed in them (22). The combined effects of metabolism are envisioned to result in an optimal balance of expression that is essential for normal biofilm development (2). Indeed, expression of the S. aureus cidABC and lrgAB operons has been shown to be tightly coordinated by regulators that sense and respond to basic metabolic processes. For example, cidABC expression is induced by the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) CidR under conditions of excess glucose and oxygen (overflow metabolism) (23–25), while lrgAB expression is stimulated by changes in membrane potential in a process that is dependent on the two-component regulatory system LytSR (26). Although much is known about the regulatory signals important in cidABC and lrgAB expression, how these signals are integrated during biofilm development remains unknown.

In the study presented here, we explore the effects of hypoxic growth on cid and lrg expression and its impact on gene expression during biofilm development. Notably, planktonic growth under hypoxic conditions was found to strongly induce the transcription of the cidABC operon, consistent with the hypothesis that hypoxic biofilm microenvironments could have a dramatic effect on the expression of these genes (27). To directly test this, we generated fluorescent reporter fusion constructs and assessed gene expression in individual cells during biofilm growth by using a BioFlux microfluidic system (28). This system allows the serial acquisition of epifluorescence images of biofilm under more biologically relevant continuous-flow conditions and provides insight into the temporal and spatial patterns of gene expression. Furthermore, this system allows the simultaneous comparison of gene expression and biofilm development within different samples. Thus, with this system, we demonstrate that the cid and lrg operons are expressed during biofilm development in response to both spatial and temporal signals. Importantly, these studies also revealed the existence of different tower types within the growing biofilm, likely resulting from variations in the metabolic activity associated with these towers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The S. aureus strains used in this study were derived from osteomyelitis isolate UAMS-1 (29) and are listed in Table 1. All experiments were initiated with fresh overnight cultures grown at 37°C in tryptic soy broth (TSB; EMD Biosciences, Gibbstown, NJ). Aerobic cultures were generated by the inoculation of overnight cultures into TSB medium with or without glucose to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 and incubation with shaking at 250 rpm, 37°C, and a 10:1 flask-to-volume ratio. Hypoxic growth was achieved by growing the cells statically at 37°C in a covered flask at a 5:3 flask-to-volume ratio. Dissolved oxygen levels were measured with a portable dissolved oxygen meter (Accumet) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml), erythromycin (2 μg/ml), and tetracycline (5 μg/ml) were added to the growth medium as needed.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | Host strain for construction of recombinant plasmids | |

| S. aureus | ||

| RN4220 | Highly transformable strain; restriction deficient | 30 |

| UAMS-1 | Clinical isolate | 29 |

| KB999 | UAMS-1 lytS::ermC | 26 |

| KB1090 | UAMS-1 cidR::ermC | 25 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1 | E. coli PCR cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pBK123 | Shuttle vector, pCN51ΔEM::CAT; Cmr | 31 |

| pEM64 | pBK123 derivative containing Cd-inducible GFPaav; Emr | This study |

| pEM80 | lrgAB promoter::sGFP, Cmr | This study |

| pEM81 | cidABC promoter::sGFP, Cmr | This study |

| pEM87 | ldh1 promoter::sGFP, Cmr | This study |

| pCM11 | Shuttle vector encoding sGFP | 32 |

| pDM4 | lrgAB promoter::sDsRed, cidABC promoter::sGFP, Cmr | This study |

Generation of transcriptional reporter fusions.

The S. aureus cidABC, lrgAB, and ldh1 promoter regions were PCR amplified with oligonucleotide primers flanking these sequences and Thermolace high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Specifically, a 689-nucleotide (nt) DNA fragment spanning the promoter region of cidABC (PcidABC) and a 500-nt DNA fragment spanning the promoter regions of lrgAB (PlrgAB) and ldh1 (Pldh1) were amplified with the cidA-pro, lrgA-pro, and ldh1-pro primer sets, respectively, listed in Table 2. Each promoter fragment was ligated into pCR2.1 with the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and the recombinant plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH5α cells (Table 1). After the absence of mutations was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing, the promoter fragments were excised by digestion with the restriction endonucleases SphI and BamHI and used to replace the cadmium-inducible promoter in front of the gene encoding the short half-life GFPaav in plasmid pEM64. Because of the weak fluorescence of GFPaav, the gene for GFPaav was replaced with the gene encoding superfolder GFP (sGFP) from pCM11 (Table 1). The resulting transcriptional fusion plasmids, pEM80 (PlrgAB), pEM81 (PcidABC), and pEM87 (Pldh1), were then electroporated into S. aureus strain RN4220 (Table 1). Plasmid DNA from the transformants was reisolated and electroporated into S. aureus UAMS-1 and its cidR and lytSR mutant derivatives, KB1090 and KB999 (Table 1).

Table 2.

Primers used in this studya

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| cidA-pro-F | 5′-CCCGCATGCAGCAAATTATCAATGATGAAGTAGATA-3′ |

| cidA-pro-R | 5′-CCCGGATCCCGCCATCCCTTTCTAAATAC-3′ |

| lrgA-pro-F | 5′-CCCGCATGCCGATAAAATTCACATGTTAAAGC-3′ |

| lrgA-pro-R | 5′-CCCGGATCCCGTTTGATTTAACTAAAGTATAGATGG-3′ |

| ldh1-pro-F | 5′-CCCGCATGCATGGCTTTTAATAAATTTTC-3′ |

| ldh1-pro-R | 5′-CCCGGATCCTACAAAAACTCCCTTATGAT-3′ |

| cidA-rt-F | 5′-GGGTAGAAGACGGTGCAAAC-3′ |

| cidA-rt-R | 5′-TTTAGCGTAATTTCGGAAGCA-3′ |

| lrgA-rt-F | 5′-GCATCAAAACCAGCACACTTT-3′ |

| lrgA-rt-R | 5′-TGATGCAGGCATAGGAATTG-3′ |

| sigA-rt-F | 5′-AACTGAATCCAAGTCATCTTAGTC-3′ |

| sigA-rt-R | 5′-TCATCACCTTGTTCAATACGTTTG-3′ |

| DsRed-F | 5′-CAGAGTCGACTGATTAACTTTATAAGGAGGAAATACATATGGACAACACCGAGG-3′ |

| DsRed-R | 5′-ACATGCATGCTACAGGAACAGGTGGTGGCGG-3′ |

| sGFP-F | 5′-CACGAATTCTGATTAACTTTATAAGGAGGAAAAACATATGCCCGGGAGCAAAGGAG-3′ |

| sGFP-R | 5′-CCTGGCGCGCCTTCTTATTTGTAGAGCTCATCCATGCC-3′ |

| lrgA-R | 5′-GCTGGATCCACGTTTGATTTAACTAAAGTATAGATGGCTCAC-3′ |

| cidA-R | 5′-GCCGGAATTCTAAATACGTCTAAATTGTTACAATAACTATTATAAAGATGGCG-3′ |

| cidABC-lrgAB-F | 5′-GTTTCCAGTCCATTCAAGCGTTCCGCACATGACCAATACGCAGTACAG-3′ |

| lrgAB-cidABC-F | 5′-CTGTACTGCGTATTGGTCATGTGCGGAACGCTTGAATGGACTGGAAAC-3′ |

| sDsRed-F | 5′-AGCGGATCCAGATAATCTATAAAAGGAGG-3′ |

| sDsRed-R | 5′-TCTTGCATGCTTATAAAAACAAATGATGACGAC-3′ |

Recognition sequences for restriction endonucleases used for cloning are underlined.

A dual-reporter plasmid (designated pDM4) containing divergently transcribed cidABC and lrgAB promoter regions fused to genes encoding green and red fluorescent proteins, respectively, was constructed as follows. Primers DsRed-f and DsRed-r (Table 2) were used to amplify the gene encoding DsRed.T3(DNT) fluorescent protein (33). The 717-bp DsRed.T3(DNT) PCR product was ligated into the SalI-SphI sites of the shuttle vector pBK123 (Table 1), producing pDM1. With primers lrgA-r, cidA-r, cidABC-lrgAB-f, and lrgAB-cidABC-f (Table 2), the promoter regions spanning the 833 and 602 bp upstream of cidABC and lrgAB, respectively, were amplified from the S. aureus UAMS-1 chromosome and combined by splicing by overlap extension (34), resulting in a 1,441-bp DNA fragment containing the cid and lrg promoters in a divergent orientation. After the confirmation of this fragment by nucleotide sequencing, it was ligated into the EcoRI and BamHI sites of pDM1 to generate pDM2. Next, a 768-bp DNA fragment encoding sGFP from pEM80 was amplified with primers sGFP-r and sGFP-f (Table 2) and then ligated into the EcoRI and AscI sites of pDM2, generating pDM3. Finally, because of the weak expression of the gene encoding DsRed.T3(DNT), the coding region was optimized for codon usage in S. aureus and synthesized by GeneArt (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). This gene was then used to replace the unoptimized DsRed.T3(DNT) gene in pDM3, resulting in the plasmid pDM4.

RNA quantification.

Total S. aureus RNA was isolated as previously described (26) with minor modifications as follows. Briefly, S. aureus cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,100 rpm in a Legend tabletop centrifuge (Sorvall, Newtown, CT) and the resulting pellets were resuspended in 500 μl of TSB. Then 1.0 ml of RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was added, and samples were vortexed vigorously for 30 s and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Cells were then pelleted by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min in a Microfuge 18 centrifuge (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA); supernatants were removed, and pellets were stored at −80°C. Once all samples had been collected, the cells were thawed for 10 min and resuspended in 900 μl of RLT buffer, and RNA was isolated with an RNeasy Mini RNA purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as described previously (26).

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with the cidA-, lrgA-, and sigA-specific primers listed in Table 2. Briefly, 500 ng of total RNA was converted to cDNA with the QuantiTect reverse transcription kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). The samples were then diluted 1:50, and the cidA, lrgA, and sigA cDNA products were amplified with 5.0 μM cidA-rt, lrgA-rt, and sigA-rt primers (Table 2), respectively, and the LightCycler DNA Master SYBR green I kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) by following the manufacturer's instructions. n-Fold changes in cidA and lrgA transcript levels were calculated by the comparative threshold cycle method (35), normalizing to the amount of sigA transcripts present in the RNA samples. Results were recorded in triplicate, representative of three independent experiments. Data were analyzed with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for nonparametric data.

Biofilm assays.

To continuously monitor gene expression during biofilm development, we used a BioFlux 1000 microfluidic system (Fluxion Biosciences Inc., San Francisco, CA), which allows the acquisition of epifluorescence microscopic images over time. To grow biofilm in the BioFlux system, the channels were first primed for 5 min with 200 μl of TSB at 5.0 dynes/cm2. After priming, the TSB was aspirated from the output wells and replaced with 200 μl of fresh overnight cultures diluted to an OD600 of 0.8. The channels were seeded by pumping from the output wells to the input wells at 2.0 dynes/cm2 for 5 to 10 s. Cells were then allowed to attach to the surface of the channels for 1 h at 37°C. Excess inoculums were carefully aspirated off, and 1.3 ml of 50% TSB plus 0.125% glucose was added to the input well and pumped at 0.6 dyne/cm2 for 18 h (flow rate, 64 μl/h). Bright-field and epifluorescence (with fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC] and tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate [TRITC] filters) images were taken at ×200 magnification at 5-min intervals at a total of 217 time points for each strain tested; the gain and exposure settings were kept consistent for all images.

To analyze expression in a static biofilm assay, overnight cultures of each strain were grown and diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in TSB plus 0.5% glucose with 1.0 μM Toto-3. Subsequently, 400 μl of each inoculum was placed in one well of an eight-chamber Lab-Tek chambered number 1.0 borosilicate coverglass system (Nunc, Rochester, NY). Biofilms were grown for 6 h, at which point they were imaged by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) as described in detail below.

Confocal microscopy.

Planktonic S. aureus cells expressing fluorescent reporter genes were grown and imaged by CLSM as follows. Overnight cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.1 into fresh medium and incubated under aerobic and hypoxic conditions as described above. Samples of the cultures were harvested and pelleted by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 3 min. The pellets were resuspended in 0.85% NaCl to an OD600 of approximately 5.0. A 2.5-μl volume of each preparation was placed on a microscope slide, covered with a coverslip, and imaged with an inverted Zeiss 510 Meta confocal laser scanning microscope fitted with a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.40 numerical aperture oil differential interference contrast (DIC) M27 objective set to a 3.0× digital zoom. In addition to the acquisition of DIC images, a 488-nm argon laser was used to excite any GFP present in the cells and the emissions were collected with a 505- to 550-nm band pass filter. For static biofilms, 30 to 40 1-μm sectioned z stack images were acquired with the same settings as above except with an EC Plan-Neofluar 40×/1.30 numerical aperture oil DIC M27 objective. Images collected from static biofilms and planktonic cells were rendered with the Imaris 7.0.0 software suite (Bitplane, Saint Paul, MN).

RESULTS

Induction of cid and lrg expression during hypoxic growth.

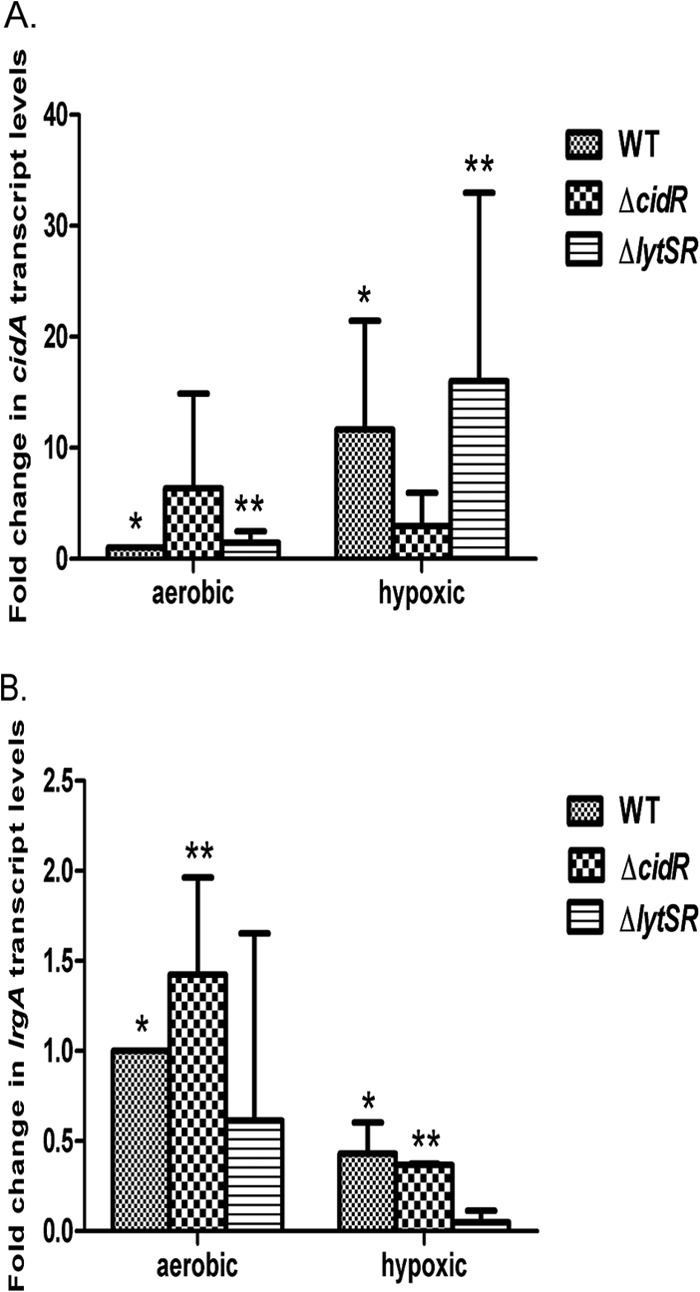

Previous studies of cidABC and lrgAB transcription showed that the expression of both of these operons was induced during aerobic overflow metabolism (23), where the high rate of glycolysis inhibits aerobic respiration and induces carbon flow through fermentation pathways (27). Since staphylococcal biofilms contain regions of hypoxia (22), we hypothesized that the decrease in oxygen concentrations, leading to activation of fermentative metabolism, will also affect cid and lrg expression. To test this, RNA was extracted from aerobically and hypoxically grown cells at 4 h postinoculation and the relative levels of cid and lrg transcripts were determined by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR). Measurements of oxygen revealed that hypoxic growth resulted in an oxygen concentration of approximately 1% total saturation, compared to approximately 70% total oxygen saturation under our standard growth conditions (see Materials and Methods). As anticipated, the levels of the cid-specific transcripts were markedly higher (approximately 12-fold) in cells grown under hypoxic conditions than in cells grown aerobically (Fig. 1A). Consistent with previous studies (25), cid expression was induced under excess glucose conditions in a cidR-dependent but lytSR-independent manner, respectively (data not shown). Similarly, the induction of cid expression under hypoxic conditions was found to be cidR dependent and lytSR independent (Fig. 1A). In contrast, lrgAB transcription was found to be slightly decreased under hypoxic conditions but remained lytSR dependent (Fig. 1B), as previously demonstrated (31, 36). Additionally, we found that lrgAB expression was not influenced by the cidR mutation during growth under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 1B). Taken together, these data demonstrate that hypoxic conditions induce cidABC operon expression in a CidR-dependent manner, similar to its induction observed during overflow metabolism. However, unlike the induction of lrgAB expression previously observed during overflow metabolism, hypoxic growth does not affect lrgAB transcription.

Fig 1.

Hypoxic induction of cidABC and lrgAB transcription. Total RNAs were collected from S. aureus WT (UAMS-1), cidR mutant, and lytSR mutant cells at 4 h of growth under aerobic and hypoxic conditions. The cidABC (A) and lrgAB (B) transcripts present in the RNA were detected by qRT-PCR with cidA- and lrgA-specific primers, normalized to the levels of sigA-specific transcripts detected, and then plotted as n-fold changes relative to the cidABC and lrgAB transcript levels in WT cells grown under aerobic conditions. Error bars represent standard deviations generated from three independent experiments. In panel A, significant differences (P < 0.05 for all) between aerobic and hypoxic treatments are denoted as follows: *, WT; **, ΔlytSR. In panel B, significant differences (P < 0.05 for all) between aerobic and hypoxic treatments are denoted as follows: *, WT; **, ΔcidR.

Expression of cid and lrg in individual cells.

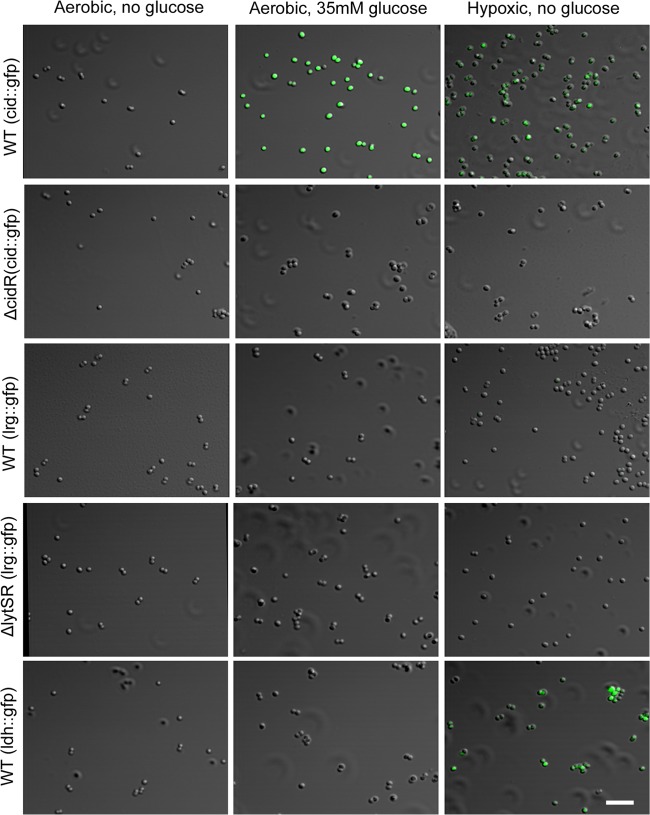

To test the hypothesis that the cid and lrg operons are differentially expressed within a growing biofilm, we generated cid and lrg transcriptional reporter fusions to facilitate the assessment of the expression of these genes in individual cells during different stages of biofilm development. Promoter regions of both the cid and lrg operons were amplified and inserted upstream of the gene encoding sGFP, which was previously shown to be easily detected in S. aureus cultures (32). The resulting constructs were moved into UAMS-1, as well as the cidR and lytSR derivatives of this clinical isolate. The strains were tested to determine if GFP expression during planktonic growth reflects the transcriptional regulation seen by Northern blotting analyses (23, 25, 36) and qRT-PCR analyses (Fig. 1). Indeed, when grown in the presence of excess glucose or under hypoxic conditions, the cid::gfp reporter construct produced increased levels of GFP fluorescence (Fig. 2), as opposed to aerobically grown cells in the absence of glucose, and was cidR dependent (Fig. 2). In contrast, the lrg::gfp promoter construct did not produce detectable fluorescence under these conditions (Fig. 2). However, when grown in the presence of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), a membrane potential-dissipating agent known to induce lrgAB expression, the lrg::gfp promoter construct fluoresced brightly in a lytSR-dependent manner (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). As a control, we also generated a gfp fusion to the ldh1 promoter that is specifically expressed during hypoxic growth (37). In wild-type (WT) cultures containing the ldh1::gfp promoter fusion grown under hypoxic conditions, GFP fluorescence was seen in the majority of the cells, in contrast to the absence of fluorescence in cells grown aerobically in the presence or absence of excess glucose (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Expression of fluorescent reporters during planktonic growth. S. aureus UAMS-1 (WT), the cidR mutant (ΔcidR) strain, and the lytSR mutant (ΔlytSR) strain containing the cid::gfp, lrg::gfp, and ldh::gfp transcriptional reporter plasmids were grown to exponential phase in the presence or absence of 35 mM glucose and under aerobic and hypoxic conditions as indicated. GFP-positive cells were visualized by CLSM at ×630 magnification as described in Materials and Methods. The scale bar represents 5 μm.

Expression of cid and lrg operons during biofilm development.

To study cid and lrg expression within a biofilm, we first examined the fluorescent reporter constructs in biofilm grown under static conditions. As shown in Fig. S2a and c in the supplemental material, GFP fluorescence was observed in biofilm formed by the WT strain containing the cid fusion but not in the cidR mutant, similar to growth under planktonic conditions (Fig. 1). Also similar to planktonic growth (Fig. 2), the lrgAB promoter was not expressed in a static biofilm (see Fig. S2d). As anticipated on the basis of previously published results demonstrating the hypoxic nature of static biofilms (22), the ldh promoter fusion construct also expressed GFP fluorescence in our static biofilm assays (see Fig. S2b).

To examine the pattern of cid and lrg expression during biofilm development under flow cell conditions, we took advantage of BioFlux technology (28) to acquire sequential bright-field and epifluorescence images of a developing biofilm. The BioFlux system is a microfluidic device that precisely controls the flow of growth medium between two interconnected wells of a microtiter plate. By positioning the channel connecting the two wells over a window accessible for viewing by epifluorescence microscopy, biofilm growth can be monitored in a time course assay in which images are collected at 5-min intervals. In addition, the microtiter plate is positioned on a motorized stage, allowing the analysis of the development of multiple biofilms simultaneously. As shown in the video compilations of the collected images (see Videos S1 to S4 in the supplemental material), the growth of the fusion strains in this system was initially rapid, resulting in a confluent “lawn” of cells that was followed by a period of dispersal. After this initial phase, distinct foci of robust biofilm growth were observed, resulting in the formation of tower structures (Fig. 3, 4, and 5).

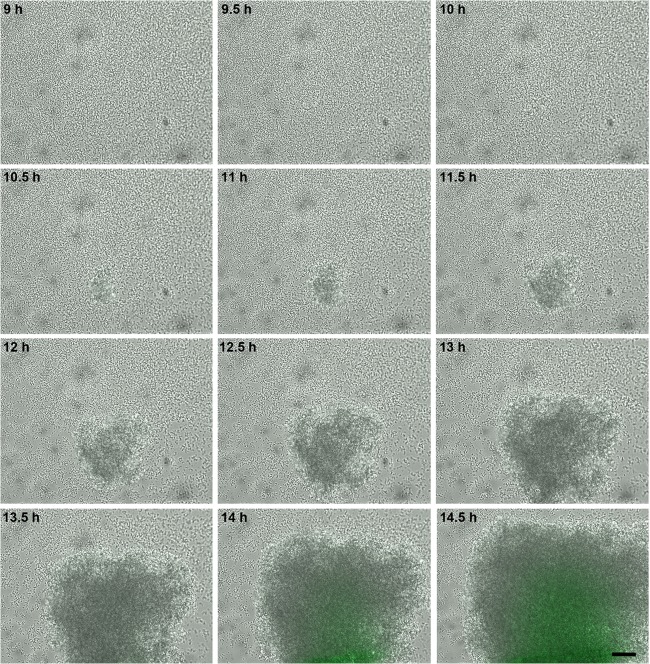

Fig 3.

Temporal analysis cidABC expression during biofilm development. S. aureus cells containing the cid::gfp reporter plasmid were inoculated into a BioFlux microfluidic system and allowed to form a biofilm within a flow shear environment at a flow rate of 64 μl/h for a total of 18 h. Bright-field and epifluorescence microscopic images were collected at 5-min intervals. The images presented were taken from the complete set of 217 images (see Video S1 in the supplemental material for a video compilation of these images) taken at ×200 magnification, spanning 9 to 14.5 h, and illustrate typical tower development and GFP expression observed in multiple experiments. For a complete video compilation of this experiment, see Video S1. The scale bar represents 50 μm.

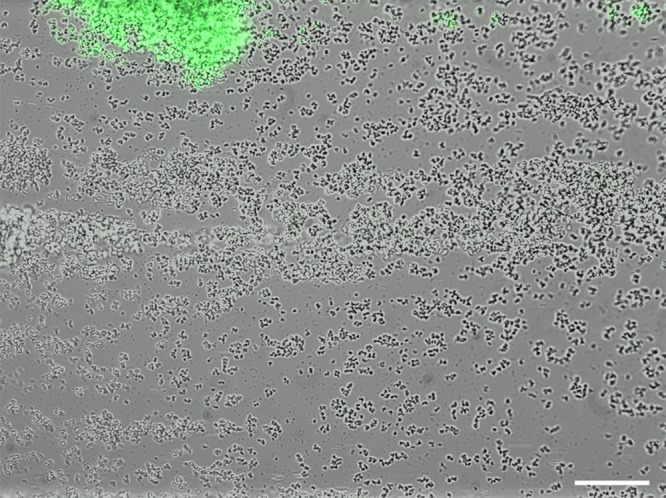

Fig 4.

High-level cid expression in small towers. S. aureus cells containing the cid::gfp reporter plasmid were inoculated into a BioFlux microfluidic system and allowed to form a biofilm as described in the legend to Fig. 3. The image shown (at ×200 magnification) represents a typical constitutive highly fluorescent “small” tower that is formed by this strain, distinct from the delayed fluorescence produced by the “large” towers depicted in Fig. 3. Note the presence of detached, highly fluorescent cells “downstream” (to the right) of the tower. The scale bar represents 50 μm.

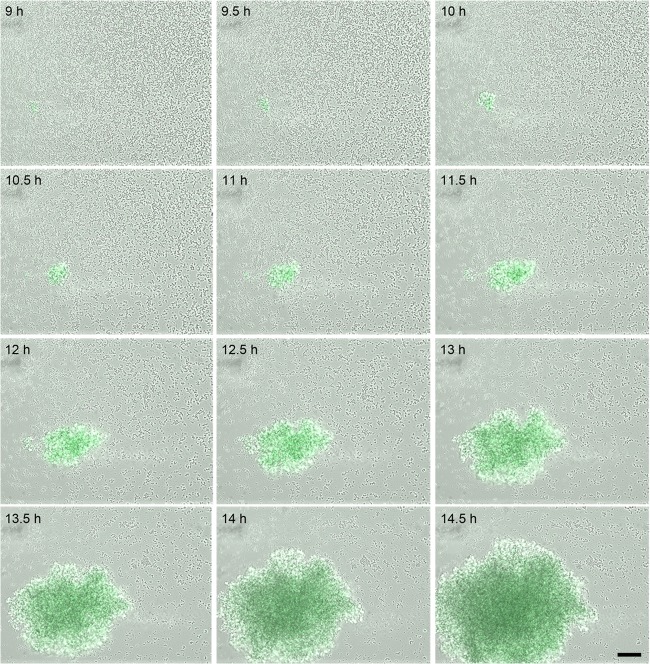

Fig 5.

Temporal analysis of lrgAB expression during biofilm development. S. aureus cells containing the lrg::gfp reporter plasmid were inoculated into a BioFlux microfluidic system and allowed to form a biofilm within a flow shear environment at a flow rate of 64 μl/h for a total of 18 h. Bright-field and epifluorescence microscopic images were collected at 5-min intervals at ×200 magnification. The images presented were taken from the complete set of 217 images spanning 9 to 14.5 h and illustrate typical tower development and GFP expression observed in multiple experiments. See Video S3 in the supplemental material for a video compilation of these images. The scale bar represents 50 μm.

Analysis of the epifluorescent images revealed distinct patterns of cid and lrg expression during the development of these biofilms. With the UAMS-1 cid::gfp fusion strain (Fig. 3; see Video S1 in the supplemental material), distinct clusters of cells or “towers” emerged and gradually turned green as they increased in size, similar to the pattern of expression observed with the ldh::gfp fusion strain (see Fig. S3 and Video S2), consistent with the hypothesis that hypoxic regions of the biofilm (within the interior of the large towers) induce cid expression. Unexpectedly, the cid::gfp fusion strain also produced smaller towers with constitutively high levels of fluorescence (Fig. 4), clearly distinct from the larger towers. These smaller towers appeared to emerge from a single highly fluorescent cell that divided (although with a seemingly lower growth rate than the other clusters) and remained exclusively associated with its siblings until a large, intensely fluorescent tower was formed. In addition, these towers appeared to be less adherent, as demonstrated by their propensity to release smaller cell clusters (Fig. 4). Importantly, similar highly fluorescent towers were observed in the ldh::gfp fusion strain (unpublished results), suggesting that overlapping metabolic cues may be responsible for the high-level cid and ldh expression observed in these small towers. Also, no cid::gfp-mediated fluorescence in either tower type was observed in a strain in which the cidR gene had been disrupted (unpublished results), suggesting that the signals responsible for cid expression in the two tower types were similar.

The UAMS-1 lrg::gfp fusion strain exhibited a different pattern of expression during biofilm development (Fig. 5; see Video S3 in the supplemental material). Similar to the cid and ldh promoter fusion constructs, the lrg::gfp fusion strain produced fluorescence in what appeared to be the large towers that exhibited inducible cid and ldh expression as the towers matured. However, unlike what was observed with the cid and ldh promoter fusion constructs, the lrg::gfp fusion strain produced constitutive fluorescence without increasing expression within growing towers, consistent with results indicating that this promoter is not inducible under hypoxic conditions. Importantly, it should be noted that despite the fact that the lrg::gfp fusion strain did not produce detectable fluorescence in planktonic culture or static biofilm assays, this strain produced robust fluorescence within towers formed in this flow cell system, suggesting that this operon is controlled by developmental signals associated with biofilm formation. As expected, the fluorescence produced by the lrg::gfp construct was abolished in the lytSR mutant background (unpublished data).

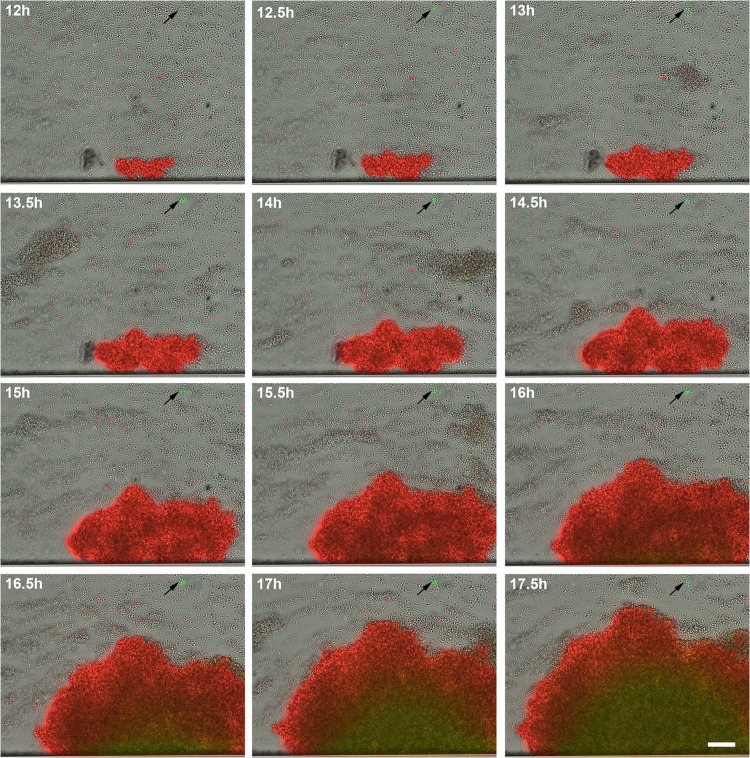

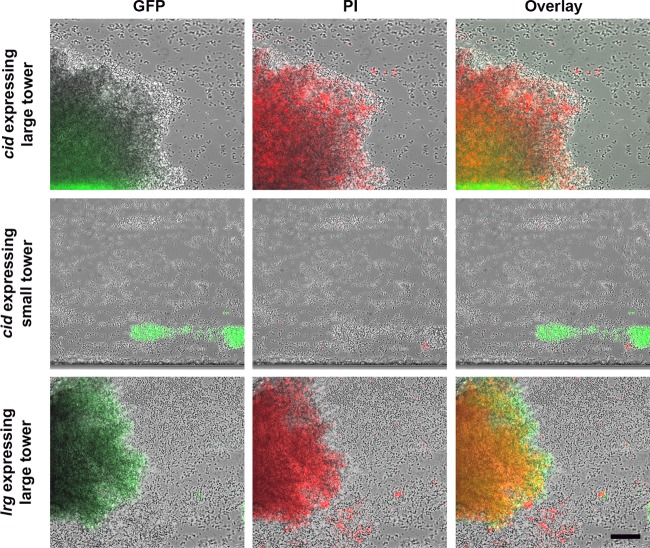

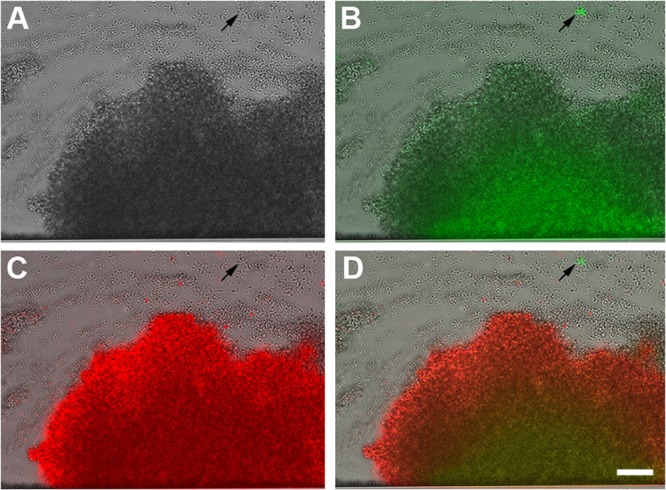

To clearly distinguish the coincidence of cid and lrg expression within the tower structures, a cid-lrg dual-reporter strain was also generated. The cid promoter was fused to the gene encoding sGFP, and the lrg promoter was fused to the gene encoding DsRed.T3(DNT). WT UAMS-1 containing this construct was grown with the BioFlux system and observed during biofilm development. As shown in Fig. 6 (see also Video S4 in the supplemental material), lrg expression (red fluorescence) was detected early in the development of the towers (12 h), followed by the emergence of cid expression (green fluorescence) as the towers increased in size (starting at 16 h). Distinct small towers expressing high levels of cid were also observed (Fig. 6, arrows), similar to those produced by the cid::gfp fusion strain (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 7, which illustrates the fluorescence detected with the different filter sets, the small towers (arrows) clearly express a high level of cid-associated sGFP fluorescence and nearly undetectable levels of lrg-associated DsRed fluorescence, while the large towers express both promoters, albeit with different temporal patterns. These data confirm the existence of two distinct tower types, one that is characterized by rapid cell division, constitutive lrg expression, and gradual cid expression induced presumably as the tower enlarges and becomes hypoxic and another that exhibits relatively slow cell division and high constitutive levels of cid expression.

Fig 6.

Simultaneous temporal analyses of cidABC and lrgAB expression during biofilm development. S. aureus cells containing the cid::gfp lrg::sDsRed dual-reporter plasmid were inoculated into a BioFlux microfluidic system and allowed to form a biofilm within a flow shear environment at a flow rate of 64 μl/h for a total of 18 h. Bright-field and epifluorescence microscopic images were collected at 5-min intervals at ×200 magnification. The images presented were taken from the complete set of 217 images spanning 12 to 17.5 h and illustrate the typical tower development and GFP and DsRed.T3(DNT) expression observed in multiple experiments. See Video S4 in the supplemental material for a compilation of these images. The scale bar represents 50 μm. The arrows indicate the small, highly fluorescent cid-expressing towers.

Fig 7.

Differential expression of cid and lrg within different towers. The individual images collected at 17 h from Fig. 6 are presented to better illustrate the green and red fluorescence produced by the S. aureus cid::gfp lrg::sDsRed dual-reporter strain (at ×200 magnification). The panels include images collected by bright-field microscopy only (A), a bright-field microscopy and FITC overlay (B), a bright-field microscopy and TRITC overlay (C), and a bright-field microscopy, FITC, and TRITC overlay (D). The scale bar represents 50 μm. The arrows indicate the small, highly fluorescent cid-expressing towers.

Correlation of lrg expression with cell death and lysis.

Previous studies using CLSM demonstrated that tower structures contain a high number of dead cells and/or eDNA, as indicated by viability staining techniques (6). Subsequent lysis of the dead cells resulted in clear, cell-free voids that likely contain cell debris, including released genomic DNA. This pattern of death and lysis causing a “hollowing out” of tower structures appears to be conserved in other bacterial species (18, 38), including a positive role for P. aeruginosa cid and a negative role for lrg orthologs in this process (18). To determine if cid and/or lrg expression correlates with cell death and lysis under these flow cell conditions, we grew our cid::gfp and lrg::gfp fusion constructs in the BioFlux system and stained the biofilm with propidium iodide (PI) to visualize dead cells and eDNA. As shown in Fig. 8, the large towers expressing both cid and lrg were readily stained with PI, exhibiting a relatively uniform fluorescence intensity throughout their structures (see top and bottom panels), similar to the uniform GFP-mediated fluorescence produced by the lrg::gfp fusion construct (see Video S3 in the supplemental material). Analysis of the temporal pattern of PI staining revealed that it also overlapped with lrg expression, with staining of the tower occurring early in development and continuing as they grew in size. This is in contrast to the cid::gfp reporter construct, which is expressed in the center of the tower structures only after they have reached a certain size, presumably corresponding to the hypoxic regions of the towers (see above). Interestingly, the smaller, intensely fluorescent green towers that constitutively express the cid promoter (Fig. 8, middle panels) did not retain the PI stain, also similar to the absence of lrg expression observed in these structures (Fig. 6 and 7). Overall, the results of these studies suggest that the pattern of lrg expression within a developing biofilm correlates with the presence of dead cells and/or eDNA in tower structures.

Fig 8.

Correlation of eDNA/cell death with cidABC and lrgAB expression within a biofilm. S. aureus WT cells carrying the cid::gfp and lrg::gfp reporter plasmids were inoculated into a BioFlux microfluidic system and grown into biofilms as described in the legend to Fig. 3. The biofilm was grown in 50% TSB medium containing 0.125 μM PI stain (red) to stain dead cells and eDNA. Individual images captured at 17 h demonstrate an overlap of lrg expression (green) and dead cells/eDNA (red) in large towers (top and bottom panels) and the absence of lrg expression and dead cells/eDNA in small towers (middle panels). The scale bar represents 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies in our laboratory have suggested a role for S. aureus cid- and lrg-mediated cell death and lysis during biofilm development (6, 7). Implicit in this model is that there is heterogeneity in the expression of these operons such that only subpopulations of the biofilm cells will die and lyse. Indeed, viability staining clearly revealed marked heterogeneity in the distribution of dead cells within the basal biofilm layers and more pronounced cell death and lysis associated with tower structures (6). Although these observations suggest that variations in cid and lrg expression may exist within different regions of a biofilm, our current understanding of cid and lrg regulation has been limited to studies in which the expression of these operons was assessed during planktonic growth, where the results generated represent an average level of expression throughout the population. For example, glucose metabolism in planktonic cultures was shown to induce cidABC expression via the LTTR encoded by the cidR gene (23–25). Additionally, the two-component regulatory system LytSR was shown to induce lrgAB transcription in response to changes in membrane potential (26, 31). Although both of these studies provided an appreciation of the metabolic signals important in the control of cid and lrg expression, neither afforded any insight into the heterogeneity of gene expression within the population or how the expression of these operons might be affected by growth in the context of a multicellular biofilm. Thus, a key focus of our laboratory is to gain a better understanding of how these and/or related metabolic signals are involved in the coordination of cid and lrg expression during biofilm development.

In the first part of this study, we demonstrated that in addition to being induced by growth in the presence of excess glucose, cid expression is also induced during growth in a hypoxic environment (Fig. 1), conditions known to predominate within a biofilm. In fact, aerobic growth in the presence of excess glucose is well known to induce a physiological change in cells that results in a shift from oxidative phosphorylation to substrate level phosphorylation, in which less oxygen is consumed (39). This so-called “Crabtree effect” may thus produce metabolic intermediates during aerobic growth that stimulate CidR-dependent expression of the cid operon that would normally be produced during hypoxic growth. In agreement with the notion that similar metabolic signals are sensed under these seemingly disparate conditions is the observation that cid expression under hypoxic conditions was cidR dependent, similar to the induction of this operon during growth in the presence of excess glucose (Fig. 1). As cidR encodes a member of the LTTR family of proteins, whose members are activated by the binding of specific small effector molecules, the effector interacting with CidR likely reflects the metabolic similarities that form the basis of the Crabtree effect. Although the identity of this molecule remains to be determined, it was recently speculated that pyruvate or an intermediate of pyruvate metabolism could serve this purpose on the basis of the observations that CidR-mediated control occurs under conditions favoring fermentative metabolism, as well as the fact that the CidR regulon includes two operons, both of which encode enzymes involved in pyruvate metabolism (27). Interestingly, recent studies indicate that pyruvate plays a key role in the formation of microcolonies in P. aeruginosa (40).

It seems clear that the expression and/or function of the cid and lrg operons must be a population-dependent phenomenon, given the observation that there is a mixture of live and dead cells within biofilms. Because cell death and lysis are particularly predominant within tower structures (6), we hypothesized that the level of cid expression relative to lrg is higher in tower structures than in the surrounding basal layer of cells (1). The differences in expression may be a function of localized microenvironments in which oxygen is depleted. Indeed, oxygen and nutrient gradients have been shown to exist in biofilm and have been implicated in signaling heterogeneity within the biofilm (22, 41, 42). Furthermore, P. aeruginosa (43, 44) and B. subtilis (45–47) demonstrate heterogeneous expression of genes within the biofilms they produce. On the basis of the impact of hypoxic growth on cid and lrg expression, we reasoned that variations in oxygen levels within a biofilm play an important role in the differential control of cid and lrg expression and subsequent cell death and lysis within these metabolically diverse communities. Thus, to examine the differential control of cid and lrg expression during biofilm development, transcriptional fusions of cid and lrg promoter regions with a gfp reporter gene were generated and introduced into S. aureus WT and cidR and lytSR mutant strains. We took advantage of newly developed BioFlux technology (28) that allowed us to simultaneously monitor biofilm growth and reporter gene expression under flow cell conditions over an extended time course experiment, mimicking a more physiologically relevant environment. Strikingly, growth of the cid and lrg reporter strains revealed clear temporal and spatial control of these genes. For the cid::gfp strain, fluorescence increased over time in large tower structures (Fig. 3 and 6; also see Videos S1 and S4 in the supplemental material), similar to the ldh::gfp fusion strain (see Fig. S3 and Video S2) and consistent with the hypothesis that reduced oxygen levels within these structures were responsible for the upregulation of these genes. In addition, a second highly fluorescent subpopulation of cells was observed in the cid::gfp fusion strain that was clearly distinct from those associated with large tower structures (Fig. 4, 6, and 7). In contrast to the latter, the highly fluorescent subpopulation appeared to emerge from single cells that multiplied and formed distinct tower structures that appeared less adherent, as evidenced by the observation that they tended to release small cell clusters, likely as a result of shear forces in this flow cell environment (Fig. 4). Thus, the differences in gene expression observed between the two tower types identified in this study appear to be associated with fundamentally distinct physical characteristics, such as matrix composition, although this remains to be investigated. Importantly, the lack of a genetically stable, highly fluorescent population of cells within the effluent (unpublished results) suggests that these highly fluorescent towers are not a result of a regulatory mutation (e.g., within the cidR gene).

The lrgAB::gfp strain also generated a fluorescent signal that was associated with tower structures (Fig. 5; see Video S3 in the supplemental material). Although the kinetics of this induction were clearly distinct from the delayed, gradual emergence of fluorescence observed in the large towers produced by the cid::gfp and ldh::gfp fusion strains, it was similar in some respects to the small towers expressing high levels of GFP fluorescence. However, a dual-reporter construct allowed us to determine the relationship between cid and lrg expression within individual towers and clearly demonstrated that towers exhibiting a gradual increase in cid expression were also constitutively expressing lrg. In contrast, towers constitutively expressing high cid levels were expressing low-to-undetectable levels of lrg. Interestingly, similar results were observed with a USA300 JE2 strain containing these reporter plasmids (unpublished results), suggesting that the temporal and spatial controls of cid and lrg expression are common to multiple S. aureus strains. Together, these data suggest that the differences in cid and lrg expression undoubtedly reflect the fact that the expression of these operons is controlled by distinct regulatory systems that respond to different metabolic signals. Thus, gaining a better appreciation for the metabolic cues sensed by the CidR and LytSR regulatory systems, as well as the metabolic differences between these tower types, will be essential for understanding the basis of the expression differences observed.

Given the proposed functions of the cid and lrg operons, we next wanted to examine the correlation between the expression of these genes in a biofilm and the death and lysis that occur in these structures. As shown in Fig. 8, analyses of the cid reporter construct revealed that the GFP signal produced by the cid::gfp strain overlapped the PI staining, which was previously shown to be particularly evident in these structures (6). However, it is clear that this overlap is incomplete, as evidenced by the observation that the high-level expression observed in the smaller towers was not associated with PI staining. In contrast, fluorescence produced by the lrg::gfp strain showed a better correlation with the PI-stained structures exhibiting homogeneous fluorescence throughout the large towers and no fluorescence in the small towers. Since the cidA and lrgA gene products are proposed effectors of cell death and lysis, one might predict that the disruption of these genes would affect the death and/or lysis observed by PI staining. However, similar experiments with cidA and lrgA mutants harboring the cid and lrg GFP reporter constructs revealed no obvious effect on the pattern of cell death, lysis or tower formation (as indicated by PI staining; unpublished results), suggesting that the roles of these genes are not readily detectable under these conditions. Specifically, the biofilm conditions in our microfluidic system are quite different from static assays previously described. In fact, the lack of pronounced phenotypes is most likely a function of the continuous supply of medium in the former, which has a major effect on access to nutrients and oxygen, as well as disposal of waste products such as weak acids (e.g., acetic and lactic acids). Furthermore, another possibility is that the Cid and Lrg proteins encoded by these operons simply potentiate cell death and under biofilm conditions make this process more efficient. In fact, holin proteins function much like this, as they are expressed and inserted into the membrane in an inactive form and can be induced by lethal agents that dissipate the membrane potential (48). Similarly, altered expression of members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins, critical in the control of apoptosis, does not directly affect cell viability but instead potentiates cell death or survival, depending on the relative levels of death effectors or inhibitors present in the cell (49).

Given the apparent fundamental differences in gene expression and physical properties between large and small towers, a better understanding of the relative physiological differences between these tower types should provide valuable information about the control of cell death during biofilm development. Furthermore, insight into the potential functional differences that are associated with spatially and temporally regulated genes within the biofilm, as has been observed in Bacillus subtilis (50), could be particularly enlightening. Thus, current studies with BioFlux technology are aimed at using fluorescent metabolic probes that will allow us to correlate the temporal and spatial aspects of cid and lrg expression with defined physiological states within biofilm microenvironments, providing more mechanistic and functional insights into the heterogeneous control of cell death and lysis observed within a developing biofilm.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kari Nelson for her insightful editorial comments in the preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH grants P01-AI83211 and R01-AI038901 to K.W.B.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 March 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00395-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bayles KW. 2007. The biological role of death and lysis in biofilm development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5: 721– 726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rice KC, Bayles KW. 2008. Molecular control of bacterial death and lysis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72: 85– 109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Whitchurch CB, Tolker-Nielsen T, Ragas PC, Mattick JS. 2002. Extracellular DNA required for bacterial biofilm formation. Science 295: 1487 doi:10.1126/science.295.5559.1487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Allesen-Holm M, Barken KB, Yang L, Klausen M, Webb JS, Kjelleberg S, Molin S, Givskov M, Tolker-Nielsen T. 2006. A characterization of DNA release in Pseudomonas aeruginosa cultures and biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 59: 1114– 1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guiton PS, Hung CS, Kline KA, Roth R, Kau AL, Hayes E, Heuser J, Dodson KW, Caparon MG, Hultgren SJ. 2009. Contribution of autolysin and sortase a during Enterococcus faecalis DNA-dependent biofilm development. Infect. Immun. 77: 3626– 3638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mann EE, Rice KC, Boles BR, Endres JL, Ranjit D, Chandramohan L, Tsang LH, Smeltzer MS, Horswill AR, Bayles KW. 2009. Modulation of eDNA release and degradation affects Staphylococcus aureus biofilm maturation. PLoS One 4: e5822 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rice KC, Mann EE, Endres JL, Weiss EC, Cassat JE, Smeltzer MS, Bayles KW. 2007. The cidA murein hydrolase regulator contributes to DNA release and biofilm development in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:8113– 8118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thomas VC, Thurlow LR, Boyle D, Hancock LE. 2008. Regulation of autolysis-dependent extracellular DNA release by Enterococcus faecalis extracellular proteases influences biofilm development. J. Bacteriol. 190: 5690– 5698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Webb JS, Thompson LS, James S, Charlton T, Tolker-Nielsen T, Koch B, Givskov M, Kjelleberg S. 2003. Cell death in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. J. Bacteriol. 185: 4585– 4592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gödeke J, Paul K, Lassak J, Thormann KM. 2011. Phage-induced lysis enhances biofilm formation in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. ISME J. 5: 613– 626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rice SA, Tan CH, Mikkelsen PJ, Kung V, Woo J, Tay M, Hauser A, McDougald D, Webb JS, Kjelleberg S. 2009. The biofilm life cycle and virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa are dependent on a filamentous prophage. ISME J. 3: 271– 282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Webb JS, Lau M, Kjelleberg S. 2004. Bacteriophage and phenotypic variation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. J. Bacteriol. 186: 8066– 8073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Klausen M, Aaes-Jorgensen A, Molin S, Tolker-Nielsen T. 2003. Involvement of bacterial migration in the development of complex multicellular structures in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 50: 61– 68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Groicher KH, Firek BA, Fujimoto DF, Bayles KW. 2000. The Staphylococcus aureus lrgAB operon modulates murein hydrolase activity and penicillin tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 182: 1794– 1801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patton TG, Rice KC, Foster MK, Bayles KW. 2005. The Staphylococcus aureus cidC gene encodes a pyruvate oxidase that affects acetate metabolism and cell death in stationary phase. Mol. Microbiol. 56: 1664– 1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rice KC, Firek BA, Nelson JB, Yang SJ, Patton TG, Bayles KW. 2003. The Staphylococcus aureus cidAB operon: evaluation of its role in the regulation of murein hydrolase activity and penicillin tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 185: 2635– 2643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rice KC, Bayles KW. 2003. Death's toolbox: examining the molecular components of bacterial programmed cell death. Mol. Microbiol. 50: 729– 738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ma L, Conover M, Lu H, Parsek MR, Bayles K, Wozniak DJ. 2009. Assembly and development of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. PLoS Pathog. 5: e1000354 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang Y, Jin H, Chen Y, Lin W, Wang C, Chen Z, Han N, Bian H, Zhu M, Wang J. 2012. A chloroplast envelope membrane protein containing a putative LrgB domain related to the control of bacterial death and lysis is required for chloroplast development in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 193:81– 95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yamaguchi M, Takechi K, Myouga F, Imura S, Sato H, Takio S, Shinozaki K, Takano H. 2012. Loss of the plastid envelope protein AtLrgB causes spontaneous chlorotic cell death in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 53: 125– 134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pang X, Moussa SH, Targy NM, Bose JL, George NM, Gries C, Lopez H, Zhang L, Bayles KW, Young R, Luo X. 2011. Active Bax and Bak are functional holins. Genes Dev. 25: 2278– 2290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rani SA, Pitts B, Beyenal H, Veluchamy RA, Lewandowski Z, Davison WM, Buckingham-Meyer K, Stewart PS. 2007. Spatial patterns of DNA replication, protein synthesis, and oxygen concentration within bacterial biofilms reveal diverse physiological states. J. Bacteriol. 189: 4223– 4233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rice KC, Nelson JB, Patton TG, Yang SJ, Bayles KW. 2005. Acetic acid induces expression of the Staphylococcus aureus cidABC and lrgAB murein hydrolase regulator operons. J. Bacteriol. 187: 813– 821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang SJ, Dunman PM, Projan SJ, Bayles KW. 2006. Characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus CidR regulon: elucidation of a novel role for acetoin metabolism in cell death and lysis. Mol. Microbiol. 60: 458– 468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang SJ, Rice KC, Brown RJ, Patton TG, Liou LE, Park YH, Bayles KW. 2005. A LysR-type regulator, CidR, is required for induction of the Staphylococcus aureus cidABC operon. J. Bacteriol. 187: 5893– 5900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Patton TG, Yang SJ, Bayles KW. 2006. The role of proton motive force in expression of the Staphylococcus aureus cid and lrg operons. Mol. Microbiol. 59: 1395– 1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sadykov MR, Bayles KW. 2012. The control of death and lysis in staphylococcal biofilms: a coordination of physiological signals. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15: 211– 215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Benoit MR, Conant CG, Ionescu-Zanetti C, Schwartz M, Matin A. 2010. New device for high-throughput viability screening of flow biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76: 4136– 4142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gillaspy AF, Hickmon SG, Skinner RA, Thomas JR, Nelson CL, Smeltzer MS. 1995. Role of the accessory gene regulator (agr) in pathogenesis of staphylococcal osteomyelitis. Infect. Immun. 63: 3373– 3380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kreiswirth BN, Lofdahl S, Betley MJ, O'Reilly M, Shlievert PM, Bergdoll MS, Novick RP. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305: 709– 712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sharma-Kuinkel BK, Mann EE, Ahn JS, Kuechenmeister LJ, Dunman PM, Bayles KW. 2009. The Staphylococcus aureus LytSR two-component regulatory system affects biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 191: 4767– 4775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lauderdale KJ, Malone CL, Boles BR, Morcuende J, Horswill AR. 2010. Biofilm dispersal of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on orthopedic implant material. J. Orthop. Res. 28: 55– 61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dunn AK, Millikan DS, Adin DM, Bose JL, Stabb EV. 2006. New rfp- and pES213-derived tools for analyzing symbiotic Vibrio fischeri reveal patterns of infection and lux expression in situ. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72: 802– 810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Horton RM. 1995. PCR-mediated recombination and mutagenesis. SOEing together tailor-made genes. Mol. Biotechnol. 3: 93– 99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 3: 1101– 1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brunskill EW, Bayles KW. 1996. Identification of LytSR-regulated genes from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 178: 5810– 5812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Richardson AR, Libby SJ, Fang FC. 2008. A nitric oxide-inducible lactate dehydrogenase enables Staphylococcus aureus to resist innate immunity. Science 319: 1672– 1676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stewart PS, Rani SA, Gjersing E, Codd SL, Zheng Z, Pitts B. 2007. Observations of cell cluster hollowing in Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 44: 454– 457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wojtczak L. 1996. The Crabtree effect: a new look at the old problem. Acta Biochim. Pol. 43: 361– 368 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Petrova OE, Schurr JR, Schurr MJ, Sauer K. 2012. Microcolony formation by the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires pyruvate and pyruvate fermentation. Mol. Microbiol. 86: 819– 835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Anderl JN, Zahller J, Roe F, Stewart PS. 2003. Role of nutrient limitation and stationary-phase existence in Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilm resistance to ampicillin and ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47: 1251– 1256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Borriello G, Werner E, Roe F, Kim AM, Ehrlich GD, Stewart PS. 2004. Oxygen limitation contributes to antibiotic tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48: 2659– 2664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Irvin RT, Govan JW, Fyfe JA, Costerton JW. 1981. Heterogeneity of antibiotic resistance in mucoid isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa obtained from cystic fibrosis patients: role of outer membrane proteins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 19: 1056– 1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stewart PS, Franklin MJ. 2008. Physiological heterogeneity in biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6: 199– 210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chai Y, Chu F, Kolter R, Losick R. 2008. Bistability and biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 67: 254– 263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lopez D, Vlamakis H, Kolter R. 2009. Generation of multiple cell types in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33: 152– 163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. López D, Vlamakis H, Losick R, Kolter R. 2009. Paracrine signaling in a bacterium. Genes Dev. 23: 1631– 1638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Garrett JM, Young R. 1982. Lethal action of bacteriophage lambda S gene. J. Virol. 44: 886– 892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Strasser A, Cory S, Adams JM. 2011. Deciphering the rules of programmed cell death to improve therapy of cancer and other diseases. EMBO J. 30: 3667– 3683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vlamakis H, Aguilar C, Losick R, Kolter R. 2008. Control of cell fate by the formation of an architecturally complex bacterial community. Genes Dev. 22: 945– 953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.