Abstract

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) plays a pivotal role in the regulation of the transcription of genes that encode proplasticity proteins. In the present study, we provide evidence that stimulation of rat primary cortical neurons with BDNF upregulates matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) mRNA and protein levels and increases enzymatic activity. The BDNF-induced MMP-9 transcription was dependent on extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) pathway and c-Fos expression. Overexpression of AP-1 dimers in neurons led to MMP-9 promoter activation, with the most potent being those that contained c-Fos, whereas knockdown of endogenous c-Fos by small hairpin RNA (shRNA) reduced BDNF-mediated MMP-9 transcription. Additionally, mutation of the proximal AP-1 binding site in the MMP-9 promoter inhibited the activation of MMP-9 transcription. BDNF stimulation of neurons induced binding of endogenous c-Fos to the proximal MMP-9 promoter region. Furthermore, as the c-Fos gene is a known target of serum response factor (SRF), we investigated whether SRF contributes to MMP-9 transcription. Inhibition of SRF and its cofactors by either overexpression of dominant negative mutants or shRNA decreased MMP-9 promoter activation. In contrast, MMP-9 transcription was not dependent on CREB activity. Finally, we showed that neuronal activity stimulates MMP-9 transcription in a tyrosine kinase receptor B (TrkB)-dependent manner.

INTRODUCTION

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) plays a crucial role in the regulation of synaptic plasticity (1). It is involved in rapid local changes at the synapse and has a long-term effect on the transcription of genes that are important for neuronal plasticity, such as c-Fos and Arc (2, 3). BDNF plays a critical role in activity-dependent synaptic plasticity, particularly long-term potentiation (LTP) (3–6). BDNF exerts its biological function upon binding to tyrosine kinase receptor B (TrkB), leading to the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) (7). Activity-dependent stimulation of the ERK1/2 pathway plays a critical, proplasticity role in the transduction of extracellular signals and plasticity-associated immediate early gene (IEG) induction (8–10). BDNF/TrkB-induced signal propagation activates several transcription factors, including the cyclic AMP (cAMP) response element binding protein (CREB) and serum response factor (SRF), with the latter playing a critical role in brain plasticity (11–14).

Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) is an extracellularly operating endopeptidase that has recently emerged as a new player in neuronal plasticity (15–18). It is required for late-phase LTP, memory formation, and dendritic spine remodeling (16, 19, 20). Increased MMP-9 transcription and enzymatic activity have been observed in response to neuronal depolarization driven by KCl and chemically evoked seizures induced by kainate or pentylenetetrazole (21–24). Although multiple factors that regulate MMP-9 expression have been described in different cell types, the molecular mechanism that controls MMP-9 transcription in neurons remains poorly understood (for a review see references 25 and 26).

In the present study, we investigated the existence of a direct link between the proplasticity molecules BDNF and MMP-9. Because BDNF is involved in the regulation of plasticity-related gene expression, we tested the hypothesis that BDNF can regulate MMP-9 production in neurons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The following plasmids have been described previously: EF1αLacZ, 1×CRE (CRE-luciferase reporter) (27), a hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged expression vector for constitutively active MKK1 (28), a dominant negative mutant of SRF (DN-SRF) (29, 30), dominant negative Flag-MKL1 (C630) (31), a dominant negative mutant of p53 (32), shMKL1 (33), pSUPER-shGFP (where shGFP is a small hairpin RNA [shRNA] targeting green fluorescent protein) (33), a mutant form of CREB (A-CREB) (34),and an expression vector for inducible cAMP early repressor 2γ (ICER IIγ) (35). Small hairpin RNA constructs that were based on the pRNAT-H1.1/Shuttle vector and targeting serum response factor (shSRF) or negative control were donated by B. P. Herring (Department of Cellular and Integrative Physiology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN) (36). Constructs expressing tethered the AP-1 dimers c-Jun–c-Fos, JunB–c-Fos, JunD–c-Fos, JunB-JunB, JunD-JunD, and JunB-JunD in which AP-1 monomers were joined via a flexible polypeptide tether were kindly provided by M. Wisniewska (International Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Warsaw, Poland) (37).

The following antibodies and reagents were obtained from commercial sources: rabbit anti-MMP-9 antibody (G657; Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (E10; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-α-tubulin (Sigma), mouse anti-β-galactosidase (β-Gal) (Promega), anti-c-Fos (sc-7202; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-c-Jun (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-CREB (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Egr-1 (sc-110; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 5×SRE (where SRE is serum response element) (Stratagene), pAP1-luc (Clontech), recombinant human BDNF (Sigma), bicuculline (Sigma), U0126 [1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(2-aminophenylthio)butadiene; Calbiochem], PD98059 (2′-amino-3′-methoxyflavone; Calbiochem), TrkB-Fc (R&D Systems), and duplex RNA oligonucleotides against rat c-Fos (1138; 5′-CUACCUAUACGUCUUCUU-TT) and rat mTOR (7513; 5′-GCGACAUCUCAUGAGAACCTT) (both from Sigma).

Introducing point mutations into the MMP-9 reporter plasmid.

The luciferase reporter plasmid for MMP-9 containing the wild-type (wt) MMP-9 promoter fragment from bp −1369 to +35 (herein called MMP-9 luc wt) and the fragment with the proximal AP-1 binding site mutated from bp −88 to −80 [herein called MMP-9 luc mt(−88/−80)] were described previously (24). Point mutations in the core of the distal AP-1 binding site mt(−514/−507) fragment as well as in the potential SRF-binding site mt(−237/−228) fragment of the MMP-9 promoter were introduced with a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The following primers were used: GCAGGAGAGGAAGCTGAGAAAAAGACACTAACAGGGGG (AP-1 binding site, TGAGTCA) and TGTGGGTCTGGGGTCCTGCTTGCCTTTTCAGTGGGGGACTGTGGGCA (SRF-binding site, CCTGACTTGG) (nucleotides corresponding to the indicated transcription factor binding site are in boldface and substituted nucleotides are underlined).

Generation of shRNA expression constructs.

To generate MKL2 and c-Fos shRNA constructs, the corresponding rat mRNA sequences (MKL2, XM_001075589; c-Fos, X06769) were analyzed using small interfering RNA (siRNA) design software (http://sonnhammer.cgb.ki.SE/). Oligonucleotides were designed (MKL2, GATCCCCGCAGTTCCTGAATTCTTGATTCAAGAGATCAAGAATTCAGGAACTGCTTTTTGGAAA; c-Fos, GATCCCCCTACCTATACGTCTTCCTTTTCAAGAGAAAGGAAGACGTATAGGTAGTTTTTGGAAA) together with their complementary counterparts, annealed, and subcloned into pSUPER vector (38).

Primary neuronal culture and transfection.

Cortical neurons were prepared from newborn Wistar rats at postnatal day 0 (P0) as described previously (39). Briefly, dissociated cortical neurons were plated at a density of 106 cells/ml in basal medium Eagle (BME) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated bovine calf serum (BCS), 35 mM glucose, 1 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin. On the second day after seeding, 2 days in vitro (2 DIV), cytosine arabinoside (2.5 μM) was added to cultures to inhibit proliferation of nonneuronal cells. Cells were used for experiments at 6 to 7 DIV unless indicated otherwise. Transient transfections were performed at 4 to 5 DIV (for 72 or 48 h, respectively) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For gelatin zymography analysis neurons were cultured in Neurobasal medium supplemented with B-27 (Invitrogen).

Drug treatment.

BDNF and TrkB-Fc were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin, whereas bicuculline, U0126, and PD98059 were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The following final concentrations were used: BDNF, 10 ng/ml or 50 ng/ml; TrkB-Fc, 1 μg/ml; bicuculline, 50 μM; U0126, 30 μM; PD98059, 30 μM or 50 μM, as indicated in text. U0126, PD98059, and TrkB-Fc were added 30 min before stimulation.

RAT-2 cell culture, transfection, and drug treatment.

RAT-2 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were transfected with plasmid DNA or siRNA duplexes using Lipofectamine 2000, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, cells were washed once with PBS and starved by 3 h of incubation in DMEM without FBS. Afterwards cells were exposed to 20% FBS to induce c-Fos expression. Cells were either lysed for Western blotting or fixed for immunofluorescence staining 1 h after addition of FBS.

Immunofluorescence staining of RAT-2 cells.

For immunofluorescence staining, RAT-2 cells were fixed for 10 min with ice-cold 100% methanol. After fixation, cells were washed three times with PBS for 5 min at room temperature, blocked in 10% normal serum for 1 h, and finally incubated with primary antibodies (anti-c-Fos at 1:500 and anti-β-galactosidase at 1:500) in 1.5% normal serum overnight at 4°C. Cells were then washed three times with PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Secondary antibodies were applied in 1.5% normal serum for 1 h at room temperature and underwent three washes (10 min each) with PBS. Secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 568 were used for double labeling.

RNA preparation and quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from 1 × 106 cells using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) as described by the manufacturer. Residual DNA was removed by digestion with DNase I (Qiagen). RNA concentration was calculated from the absorbance at 260 nm, and the purity of the RNA was determined by the 260/280-nm absorbance ratio. RNA was reverse transcribed with the SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The cDNA was amplified using a set of custom sequence-specific primers and TaqMan minor groove binder (MGB) probes. The following TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) were used: Rn00579162_m1 for MMP-9 and Rn01775763_g1 for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; endogenous control). Quantitative real-time PCRs were performed using TaqMan Fast Advanced PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in an Applied Biosystems 7900HT fast real-time PCR system using the following cycling conditions: 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Additionally exemplary products were also visualized on agarose gel. Fold changes in expression were determined using the ΔΔCT (where CT is threshold cycle) relative quantification method. Values were normalized to the relative amounts of GAPDH mRNA.

Western blot analysis.

Western blotting was performed using a standard procedure. The following primary antibodies were used: MMP-9 (1:1,000), pERK1/2 (1: 2,000), ERK1/2 (1:1,000), α-tubulin (1:5,000), c-Fos (1:200 to 1:500), c-Jun (1:200), CREB (1:1,000), and Egr-1 (1:200). Blots were reprobed with an anti-α-tubulin antibody to ensure equal total-protein levels. A chemiluminescent detection method was used. For the quantification of individual bands, the scan of the photographic film was analyzed by densitometry using GeneTools software (Syngene). The blot scans were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS software.

Gelatin zymography.

For gelatin zymography analysis, neurons were cultured on 12-well plates (106 cells/well) in serum-free medium: Neurobasal medium supplemented with B-27 (Invitrogen). At 6 DIV half of the volume of the medium was aspirated, and the cells were treated with 50 ng/ml BDNF in 0.5 ml of medium. After 24 h medium was collected and analyzed by gelatin zymography as previously described (17), and the cells were lysed and subjected to Western blotting. Briefly, samples of the culture medium were mixed with SDS sample buffer in the absence of reducing reagents and separated on 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gels containing 2 mg/ml gelatin. The gels were washed twice with 2.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature and incubated in developing buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 10 mM CaCl2, 1 μM ZnCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 0.02% NaN3) for 48 h at 37°C. Following staining with Coomassie brilliant blue, the gelatinolytic activities were detected as clear bands against a blue background. For quantifications, a scan of the gel was analyzed by densitometry using GeneTools software (Syngene). After quantification, scans were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS software.

Luciferase reporter gene assays.

Neurons cultured on 24-well plates (0.5 × 106 cells/well) were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were evaluated using commercial assay kits (Promega). Recordings were performed using an Infinite M200 microplate reader with an injector system (Tecan) that allows automated injection of substrate and subsequent luminescence measurement. To monitor β-Gal activity, absorbance at 420 nm was acquired with a Sunrise 96-well plate reader (Tecan). Transcriptional activity was determined as luciferase activity normalized to β-Gal activity and compared with unstimulated controls.

ChIP.

Chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIPs) were performed as previously described (40) with some modifications. After 2 h of stimulation with 50 ng/ml BDNF, primary cortical neurons at 6 DIV (1 × 107 cells) were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, glycine was then added, and samples were incubated for 5 min to quench the formaldehyde. The cells were put on ice, collected, and washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). Next, the cells were resuspended in lysis buffer [5 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES), pH 8.0, 85 mM KCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, with protease inhibitors], incubated for 10 min on ice, and disrupted using a glass-glass homogenizer. Crude nuclear extract was collected by centrifugation at 1.3 × g for 5 min at 4°C and resuspended in 1% SDS; then high-salt lysis buffer without SDS but with protease inhibitors was added (1× phosphate-buffered saline, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate; final SDS concentration, 0.1%). Samples were sonicated on ice 11 times for 20 s each time with 40-s breaks at a 50% duty cycle and 50% power using a Sonopuls Bandelin sonicator obtaining an average of 300- to 500-bp DNA fragments. Samples were centrifuged for 15 min to remove cell debris, precleared with sonicated salmon sperm DNA-protein A-agarose (50% slurry) at 4°C with rotation, and the DNA content was measured spectrophotometrically. Equal amounts of DNA were immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C using 5 μg of anti-c-Fos antibody or 5 μg of normal rabbit IgG as a negative control. Next day, salmon sperm DNA-protein A-agarose beads (Millipore) were added for 2 h; then the beads were washed successively with low-salt wash buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, 150 mM NaCl), high-salt wash buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, 500 mM NaCl), and LiCl wash buffer (0.25 M LiCl, 1% Igepal-Ca 630, 1% deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1) and twice in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer. Antibody-DNA complexes were eluted with elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3), cross-linking was reversed, and proteins were removed by adding 5 M NaCl and proteinase K and incubated for 2 h at 42°C, followed by incubation at 65°C overnight. Next, DNA was purified. Immunoprecipitated chromatin was used as a template for real-time PCRs using Fast SYBR green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in an Applied Biosystems 7900HT fast real-time PCR system. The following primer sequences were used, modified according to Rylski et al. (41): a primer pair amplifying the MMP-9 proximal promoter region (−157/−5) containing the AP-1 binding site, CTTTGGGCTGCCCAACACACA (forward) and GAAGCAGAATTTGCGGAGGTTTT reverse; a primer pair amplifying a region situated in the last MMP-9 intron (∼7 kb downstream of the MMP-9 promoter) as a negative control, TGGTGCTGGAGAGGTAGGTGA (forward) and AGTGAAAATGGACCCCACAGTC (reverse).

Obtained data were analyzed using the ΔΔCT relative quantification method, and results are calculated as a percentage of the input.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) from at least three independent experiments. The statistical analysis of the data was performed with Statistica software (StatSoft) using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a post hoc Newman-Keuls test.

RESULTS

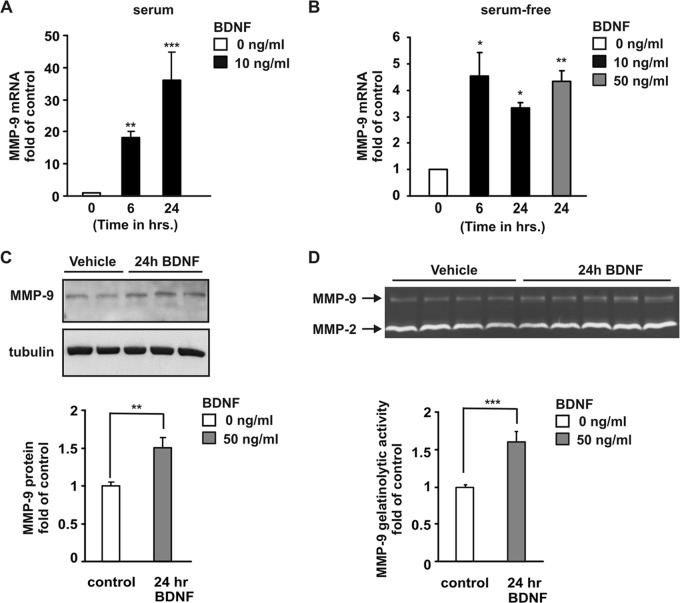

BDNF induces MMP-9 expression in cortical neurons.

To test whether BDNF contributes to the regulation of MMP-9 expression in neurons, we investigated the effects of BDNF treatment on MMP-9 levels. Rat primary cortical neurons (6 days in vitro [6 DIV]) were stimulated with BDNF, and total RNA was subjected to real-time PCR analysis. In neurons cultured in BME supplemented with serum (BCS), 6 h after BDNF exposure, we observed MMP-9 mRNA upregulation (18-fold higher than the level of the control) (Fig. 1A) which increased up to 24 h after the treatment (36-fold higher than the control level) (Fig. 1A). For the analysis of MMP-9 activity by gelatin zymography, neurons need to be cultured in serum-free medium; we verified the effect of BDNF on MMP-9 levels in neurons cultured in Neurobasal medium. Under these conditions BDNF stimulation also resulted in activation of MMP-9 transcription (Fig. 1B). We next investigated whether the observed induction of MMP-9 mRNA accumulation was followed by an increase in MMP-9 protein levels. Twenty-four hours after the BDNF stimulation of cortical neurons cultured in Neurobasal medium, cell extracts and medium were collected and subjected to Western blotting and gelatin zymography analysis, respectively. BDNF stimulation led to enhanced MMP-9 protein expression and increased MMP-9 secretion and gelatinolytic activity (Fig. 1C and D). Together, these data suggest that BDNF can induce MMP-9 mRNA upregulation in neurons, followed by increased protein expression and gelatinolytic activity.

Fig 1.

BDNF induces the expression of MMP-9 in rat primary cortical neurons. At 6 DIV, rat primary cortical neurons were stimulated with BDNF as indicated. (A and B) Induction of MMP-9 mRNA expression in BDNF-treated neurons was analyzed by real-time PCR. MMP-9 mRNA levels were normalized to the endogenous control GAPDH and are presented as relative to the level of the nonstimulated control. The determinations from at least three independent experiments are shown. (C and D) Upregulation of MMP-9 protein levels after 24 h of BDNF stimulation. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting for MMP-9 protein expression (C), and medium was analyzed for MMP-9 activity by zymography (D). Neurons were cultured in BME supplemented with BCS (A) or in Neurobasal medium supplemented with B-27 (B to D). Error bars indicate SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

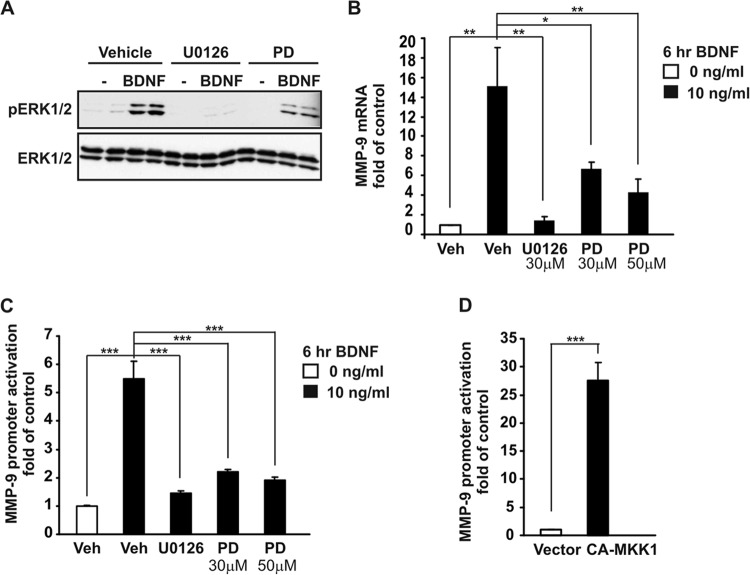

BDNF-mediated transcription of MMP-9 is dependent on ERK1/2 activity.

The ERK1/2 pathway plays a key role in BDNF-triggered signaling that leads to activation of gene transcription (7). Therefore, we investigated whether MMP-9 expression induced by BDNF requires ERK1/2 activity.

The treatment of cultured cortical neurons with BDNF resulted in increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation, with no change in total ERK1/2 levels. As expected, pretreatment with specific inhibitors of the ERK1/2 pathway, U0126 and PD98059, led to inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 2A). To determine whether MMP-9 transcription is dependent on ERK1/2 activity, cortical neurons were stimulated for 6 h with BDNF in the presence or absence of U0126 or PD98059. Inhibition of ERK1/2 blocked MMP-9 mRNA upregulation in response to BDNF (Fig. 2B). Convergent results were obtained using a luciferase reporter assay system. In these experiments, the neurons were transfected with a reporter vector in which the luciferase gene is controlled by the MMP-9 promoter fragment (−1369/+35) MMP-9 luc wt. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were stimulated for 6 h with BDNF in the presence or absence of U0126 or PD98059. ERK1/2 inhibition abolished the activation of the MMP-9 promoter by BDNF (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2C).

Fig 2.

BDNF-mediated activation of MMP-9 gene expression requires ERK1/2 activity. (A) At 6 DIV, cortical neurons were stimulated with 10 ng/ml BDNF in the presence of U0126 and PD98059 (PD), inhibitors of the ERK1/2 pathway. DMSO was used as vehicle control (Veh). Western blot analysis with an antibody specific for active phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) demonstrated that both U0126 and PD98059 abolished the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 triggered by BDNF. To ensure equal levels of total ERK1/2, the pERK1/2 blot was reprobed with an anti-ERK1/2 antibody. (B) Cortical neurons (6 DIV) were stimulated with BDNF in the presence or absence of U0126 or PD98059. Real-time PCR revealed that BDNF-mediated MMP-9 mRNA upregulation was diminished by ERK1/2 inhibition. (C) Cortical neurons (5 DIV) were cotransfected with a reporter vector-containing fragment of the rat MMP-9 promoter (−1369/+35) MMP-9 luc wt that controlled luciferase reporter expression together with an EF1αLacZ β-Gal expression plasmid as a control of transfection efficiency (0.1 μg + 0.1 μg of plasmid DNA/5 × 105 cells). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were stimulated with BDNF as described for panel B. Activation of the MMP-9 promoter was determined as the luciferase/β-Gal activity ratio and is presented as the fold change relative to the unstimulated control. (D) At 6 DIV, cortical neurons were cotransfected with the indicated constructs as described for panel C, together with either an empty cloning vector (vector) or construct that contained constitutively active MKK1 (CA-MKK1). After 48 h, CA-MKK1 strongly activated the MMP-9 promoter. In panels B to D, triplicate determinations from at least three independent experiments are shown. Error bars indicate SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To investigate whether selective activation of ERK1/2 is sufficient to activate MMP-9 transcription, the neurons were cotransfected with an MMP-9 reporter vector and an expression plasmid encoding a constitutively active mutant form of the MKK1, activator of ERK1/2 (CA-MKK1). CA-MKK1 overexpression resulted in strong activation of the MMP-9 promoter (Fig. 2D). Altogether, these data indicate that activation of ERK1/2 is both necessary and sufficient to activate MMP-9 transcription in neurons.

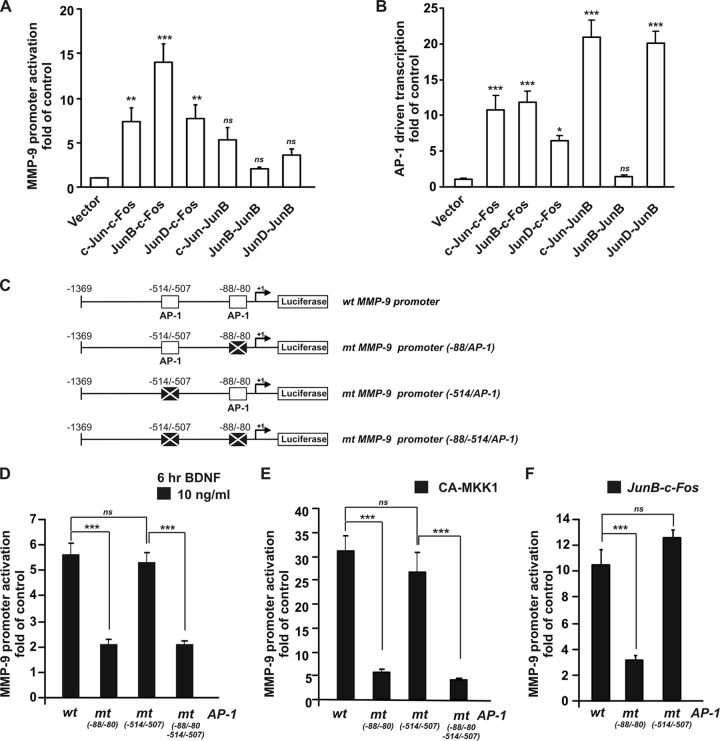

AP-1/c-Fos regulates MMP-9 transcription triggered by BDNF.

The initiation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway triggered by BDNF leads to the activation of various transcription factors that control gene expression (7). Diverse transcription factor binding sites have been described in the MMP-9 promoter, including two AP-1 binding sites, but the molecular mechanism that directly controls MMP-9 transcription in neurons remains unclear.

As a first step to evaluate whether the AP-1 transcription factor contributes to the regulation of MMP-9 transcription in neurons, we used constructs that expressed tethered AP-1 dimers in which AP-1 monomers were joined via a flexible polypeptide tether (37). We analyzed the effects of the overexpression of different tethered AP-1 dimers on activation of the MMP-9 reporter vector. Forty-eight hours after transfection, MMP-9 promoter activation was observed when c-Fos-containing AP-1 dimers were overexpressed: c-Jun–c-Fos, JunB–c-Fos, JunD–c-Fos (7.3-, 14-, and 7.7-fold higher than the level of the control, respectively; P < 0.001) (Fig. 3A). The dimers that contained only proteins from the Jun family did not significantly stimulate MMP-9 transcription although they strongly activated the pAP1-luc reporter plasmid that contained multiple AP-1 binding sites (Fig. 3A and B). Thus, the observed effects were specific for the MMP-9 promoter.

Fig 3.

AP-1 transcription factor contributes to MMP-9 promoter activation mediated by BDNF. (A and B) At 5 DIV, cortical neurons were cotransfected with the indicated reporter together with EF1αLacZ and either an empty cloning vector (vector) or a construct that contained one of the indicated AP-1 dimers. Notice the different activation patterns for the MMP-9 luc wt reporter and control pAP1-luc reporter. Overexpression of AP-1 dimers that contained c-Fos activated the MMP-9 promoter, with the most potent being JunB–c-Fos. (C) Diagram of wild-type MMP-9 luciferase reporter plasmid (MMP-9 luc wt) and mutant reporters: the proximal AP-1 binding site mutation mt(−88/−80), the distal AP-1 binding site mutation mt(−514/−507), and both AP-1 binding site mutations [mt(−88/−80, −514/−507)]. The binding sites for the AP-1 transcription factor are indicated. (D) At 5 DIV, cortical neurons were cotransfected with EF1αLacZ together with one of the following MMP-9 luciferase reporters: wild-type (wt), proximal AP-1 binding site mutation mt(−88/−80), the distal AP-1 binding site mutation mt(−514/−507), and both AP-1 binding site mutations [mt(−88/−80, −514/−507)]. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were stimulated with BDNF. (E) At 5 DIV, cortical neurons were cotransfected with the indicated constructs as described for panel D, together with either an empty cloning vector or a construct that contained constitutively active MKK1 (CA-MKK1). Notice the significant reductions of BDNF-mediated (D) or CA-MKK1 (E) activation of MMP-9 reporters if the proximal but not distal AP-1 binding site was mutated. (F) At 5 DIV, cortical neurons were cotransfected with EF1αLacZ together with one of the following MMP-9 luciferase reporters: wild type (wt), the proximal AP-1 binding site mutation mt(−88/−80), the distal AP-1 binding site mutation mt(−514/−507), and either an empty cloning vector or a construct that contained the JunB–c-Fos dimer. Mutation of the proximal AP-1 binding site [mt(−88/−80)] significantly reduced the activation of the MMP-9 promoter by JunB–c-Fos. The data represent triplicate determinations from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To determine whether the BDNF-mediated induction of MMP-9 transcription is AP-1 dependent and occurs directly through the AP-1 binding sites present in the MMP-9 promoter, mutant reporters of the AP-1 binding sites were created. The following reporter constructs were obtained by introducing two point mutations into one or both AP-1 binding sites in the MMP-9 reporter vector (MMP-9 luc wt) the constructs with the proximal AP-1 binding site mutation [mt(−88/−80)], the distal AP-1 binding site mutation [mt(−514/−507)], and mutations in both AP-1 binding sites [mt(−88/−80, −514/−507) (Fig. 3C). Neurons were transfected with one of the reporter constructs and 48 h later were stimulated with BDNF for 6 h. In neurons transfected with the wild-type (MMP-9 luc wt) reporter, BDNF increased MMP-9 promoter activation 5.6-fold compared with the vehicle-treated control, and mutation of the proximal AP-1 binding site [mt(−88/−80) or mt(−88/−80, −514/−507)] decreased this induction to 2.1-fold compared with the vehicle-treated control (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3D). Mutation of the distal AP-1 binding site [mt(−514/−507)] did not affect the BDNF-mediated activation of the MMP-9 promoter (P > 0.05). Similar effects were observed when the neurons were cotransfected with one of the reporter vectors together with a constitutively active mutant form of MKK1 (CA-MKK1). CA-MKK1 overexpression substantially activated the wild-type (wt) MMP-9 promoter (31-fold compared with the level of the control; P < 0.001), and this activation was significantly reduced when the proximal (5.8-fold compared with the level of the control; P < 0.001) but not the distal AP-1 binding site was mutated (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, because the AP-1 dimer JunB–c-Fos was the most potent activator of the MMP-9 promoter, we investigated the role of both AP-1 binding sites in this activation. Again, mutation of the proximal but not distal AP-1 binding site strongly inhibited MMP-9 promoter activation (Fig. 3F). Together, these data demonstrate that BDNF-induced MMP-9 transcription in neurons is mediated by the AP-1/c-Fos transcription factor.

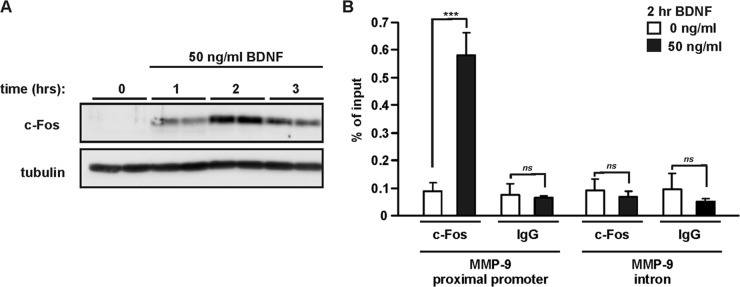

c-Fos is considered a marker of neuronal activity and plays an important role in synaptic plasticity (42–44). Our results revealed that overexpression of c-Fos-containing AP-1 dimers is able to induce MMP-9 transcription in neurons. To test the effects of BDNF on c-Fos expression, cortical neurons (6 DIV) were stimulated with 50 ng/ml BDNF. Using Western blotting, the c-Fos protein level was examined over a time course of 1 to 3 h. BDNF-mediated induction of c-Fos expression in a time-dependent manner was observed, with a peak at 2 h and a gradual decrease at 3 h after stimulation (Fig. 4A). Next, we aimed at determining whether BDNF stimulation leads to in vivo recruitment of endogenous c-Fos to the MMP-9 promoter in neurons. We performed ChIP assays on primary cortical neurons treated with 50 ng/ml BDNF for 2 h. Chromatin from BDNF-stimulated and untreated cells was immunoprecipitated using an anti-c-Fos antibody or normal IgG to determine the background, followed by real-time PCR amplification with specific primers. We used a primer pair encompassing the aforementioned proximal AP-1 binding site in the rat MMP-9 promoter region (−157/−5). As a negative control, we used primers amplifying a fragment of the MMP-9 intron; the obtained signal was at the background level (<0.1%). Stimulation of cortical neurons with BDNF significantly increased in vivo binding of c-Fos to the MMP-9 promoter (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B), suggesting that endogenous c-Fos is responsible for induction of MMP-9 transcription in response to BDNF.

Fig 4.

BDNF induces binding of endogenous c-Fos to the MMP-9 proximal promoter. (A) At 6 DIV, rat primary cortical neurons were stimulated with BDNF as indicated. Western blot analysis demonstrated induction of c-Fos expression that reached a peak after 2 h of BDNF treatment. (B) At 6 DIV, cortical neurons were stimulated with BDNF for 2 h, and then ChIP analysis of c-Fos occupancy at the MMP-9 proximal promoter was performed. BDNF stimulation led to increased binding of c-Fos at the MMP-9 promoter fragment (bp −157/−5) containing proximal AP-1 binding site. Normal IgG was used to determine the background; primers amplifying a fragment of the MMP-9 intron were used as a negative control. The data represent determinations from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate SEM. ***, P < 0.001; ns, P > 0.05.

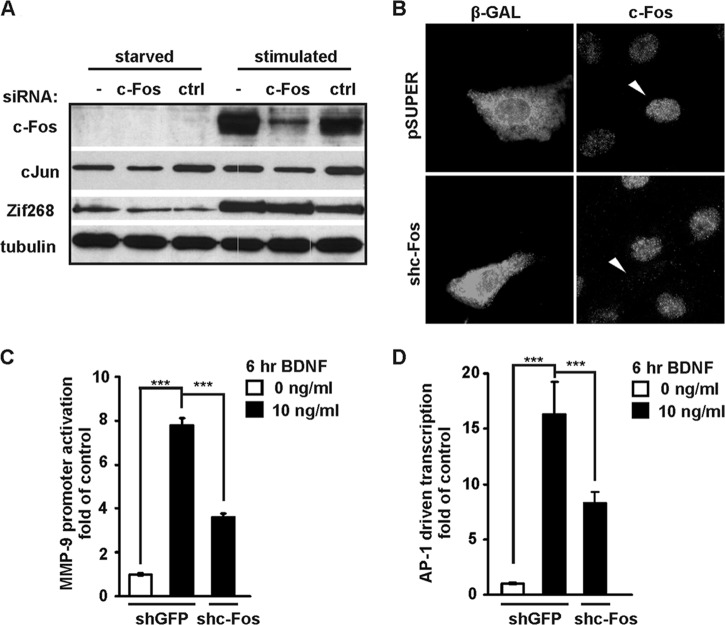

We then investigated whether the presence and binding of endogenous c-Fos are critical for BDNF-mediated MMP-9 expression. We first designed an siRNA that specifically targeted rat c-Fos. As shown in Fig. 5A, such an siRNA transfected into rat embryonic fibroblasts in the form of a duplex RNA oligonucleotide effectively prevented the appearance of c-Fos protein upon serum stimulation. In contrast, a control, unrelated siRNA (simTOR7513 [45]) did not block c-Fos expression. Neither siRNA (i.e., against c-Fos or the control) affected either another component of AP-1 (i.e., c-Jun) or an unrelated IEG (i.e., Zif268 [Egr-1]) (Fig. 5A). Once the effectiveness and specificity of the selected siRNA sequence were confirmed, we cloned this sequence to a pSUPER vector and tested whether it was equally effective when introduced in the form of a plasmid-encoded shRNA. As shown in Fig. 5B, the immunofluorescence staining of RAT-2 cells transfected with pSUPER-shc-Fos (where shc-Fos is an shRNA targeting c-Fos) confirmed that our shRNA effectively blocked c-Fos expression also in this form. Finally, to determine the contribution of c-Fos to MMP-9 transcription, we used shc-Fos to specifically inhibit endogenous c-Fos in neuronal cells. The neurons were cotransfected with an shRNA expression plasmid together with an MMP-9 reporter or control pAP1-luc reporter that contained multiple AP-1 binding sites. As a control, we used an shRNA expression plasmid that targeted GFP (shGFP). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the neurons were stimulated with BDNF for 6 h. We confirmed the ability of shc-Fos to decrease the BDNF-induced induction of AP-1-driven transcription (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5D) and observed significantly reduced BDNF-mediated activation of the MMP-9 promoter (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5C).

Fig 5.

Inhibition of endogenous c-Fos reduces BDNF-induced stimulation of MMP-9 transcription. (A) Western blot analysis of effectiveness and specificity of siRNA against rat c-Fos. RAT-2 cells cultured in vitro were transfected with RNA oligonucleotide duplexes that encoded either c-Fos siRNA or a control siRNA. Forty-eight hours later, the cells were starved from serum for 3 h and treated with 20% fetal bovine serum for 1 h. (B) siRNA against c-Fos cloned into pSUPER vector effectively inhibited c-Fos expression. RAT-2 cells cultured in vitro were transfected with either the empty pSUPER plasmid or one that encoded c-Fos shRNA. A plasmid that encoded β-galactosidase was cotransfected to visualize transfected cells. Forty-eight hours later, the cells were starved from serum for 3 h and treated with 20% fetal bovine serum for 1 h, fixed, and immunostained for c-Fos and β-galactosidase. (C and D) Cortical neurons (5 DIV) were cotransfected with EF1αLacZ together with the indicated reporter construct and either a control shRNA (shGFP) or an shRNA expression plasmid that targeted c-Fos (shc-Fos) (0.1 μg + 0.1 μg + 1.0 μg of plasmid DNA/5 × 105 cells). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were stimulated with BDNF. shc-Fos reduced the BDNF-mediated activation of the MMP-9 promoter (C) and activation of the control reporter that contained AP-1 binding sites (collagenase promoter) (D). In panels C and D, triplicate determinations from three independent experiments are shown. Error bars indicate SEM. ***, P < 0.001.

Altogether, these results demonstrate that AP-1/c-Fos is sufficient and contributes to the activation of MMP-9 transcription in neurons and can bind in vivo to the MMP-9 proximal promoter fragment in response to BDNF. MMP-9 promoter activation triggered by BDNF requires an intact AP-1 binding site in the proximal promoter region (−88/−80). In contrast, the more distal (−514/−504) AP-1 binding site does not play a role in this process.

SRF, but not CREB, contributes to BDNF-mediated MMP-9 transcription through c-Fos regulation.

Serum response factor is a transcription factor that plays a prominent role in various programs of gene expression, including IEG induction. Moreover, SRF can regulate the neuronal induction of c-Fos (11, 33, 46). Therefore, we investigated the possibility that the BDNF-mediated activation of c-Fos, which leads to upregulation of MMP-9 expression, involves the SRF-driven transcription of the c-Fos gene.

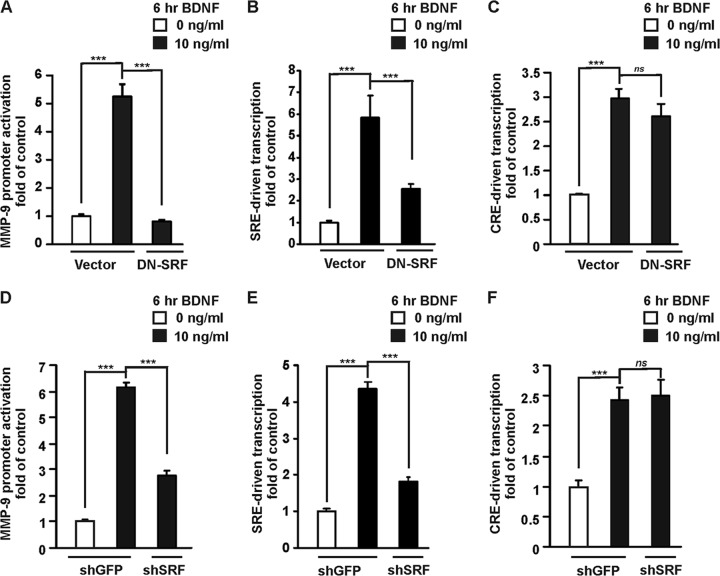

We first investigated whether SRF can contribute to the activation of MMP-9 transcription triggered by BDNF. At 4 DIV, cortical neurons were cotransfected with a reporter plasmid and an expression vector for a dominant negative mutant of SRF (DN-SRF) (29, 30). Seventy-two hours after transfection, the neurons were stimulated with BDNF for 6 h. Overexpression of DN-SRF completely abolished the BDNF-induced activation of the MMP-9 promoter (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6A). The observed effects were specific to SRF because DN-SRF blocked SRF-driven transcription as observed with the 5×SRE reporter (Fig. 6B), but it did not affect BDNF-induced stimulation of cyclic AMP response element (CRE)-driven transcription (Fig. 6C).

Fig 6.

SRF contributes to the activation of the MMP-9 promoter by BDNF. Cortical neurons (4 DIV) were cotransfected with EF1αLacZ together with the indicated reporter construct and either an empty cloning vector (Vector) or expression construct for a dominant negative mutant form of SRF (DN-SRF), in the presence of a dominant negative p53 construct (p53DD) to reduce transfection toxicity (0.1 μg + 0.1 μg + 1.0 μg + 0.1 μg of plasmid DNA/5 × 105 cells) (A to C) or either a control shRNA (shGFP) or shRNA expression plasmid that targeted SRF (shSRF) (0.1 μg + 0.1 μg + 1.0 μg of plasmid DNA/5 × 105 cells) (D to F). Seventy-two hours after transfection, the cells were stimulated with BDNF. Inhibition of endogenous SRF reduced the BDNF-mediated activation of the MMP-9 luc wt promoter (A and D). Inhibition of SRF abolished SRF-driven transcription (B and E); however, it did not affect BDNF stimulation of 1×CRE transcriptional activity (C and F). The data that present MMP-9 luc wt promoter, 5×SRE, and 1×CRE activation by BDNF in panels A to C and in Fig. 8A to C are from the same sets of experiments. For clarity of presentation, the data are displayed on two figures. Error bars indicate SEM. ***, P < 0.001; ns, P > 0.05.

To confirm the results obtained with the dominant negative mutant, we reduced SRF expression using shRNA. Cortical neurons (4 DIV) were transfected with one of the following reporters MMP-9 luc wt, 1×CRE, and 1×SRE together with an shRNA expression plasmid (either a control shRNA or an shRNA that targeted SRF) (36). Seventy-two hours after transfection, the neurons were treated for 6 h with BDNF. Knocking down SRF expression by shRNA decreased MMP-9 promoter activation triggered by BDNF (Fig. 6D) (P < 0.001), which is consistent with the results obtained with DN-SRF. The effect was specific to SRF because shSRF inhibited SRF-driven transcription (Fig. 6E), but it did not influence the BDNF-induced induction of CRE-driven transcription (Fig. 6F).

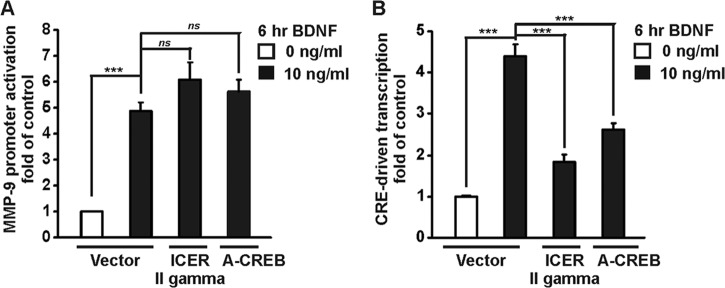

As in nonneuronal cells, MMP-9 transcription has been shown to be regulated by another transcription factor, the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) and its coactivators CREB binding protein (CBP) and p300 (47, 48); we verified whether CREB contributes to BDNF-mediated MMP-9 transcription in neurons. We used two different approaches to inhibit endogenous CREB in neurons: we overexpressed inducible cyclic AMP early repressor 2γ (ICER IIγ) (35), which is an endogenous repressor of CREB, or a mutant form of CREB (A-CREB) that inhibits DNA binding of endogenous CREB (34). At 5 DIV, cortical neurons were cotransfected with a reporter plasmid, MMP-9 luc wt or 1×CRE, together with either an empty cloning vector (vector) or an expression construct for ICER IIγ or A-CREB. Seventy-two hours after transfection, the neurons were stimulated with BDNF for 6 h. Inhibition of CREB by ICER IIγ or A-CREB overexpression did not affect the BDNF-induced activation of the MMP-9 promoter (P > 0.05) (Fig. 7A), while it blocked BDNF-induced stimulation of cAMP response element (CRE)-driven transcription (P < 0,001) (Fig. 7B).

Fig 7.

Inhibition of endogenous CREB does not affect BDNF-mediated MMP-9 transcription. Cortical neurons (5 DIV) were cotransfected with EF1αLacZ together with the indicated reporter construct and either an empty cloning vector (Vector), an expression construct for ICER IIγ, or a mutant form of CREB (A-CREB) in the presence of a dominant negative p53 construct (p53DD) to reduce transfection toxicity (0.1 μg + 0.1 μg + 1.0 μg + 0.1 μg of plasmid DNA/5 × 105 cells). Seventy-two hours after transfection, the cells were stimulated with BDNF. Both ICER IIγ and A-CREB inhibited CRE-driven transcription (B) but did not affect the BDNF-mediated activation of the MMP-9 promoter (A). The data represent triplicate determinations from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate SEM. ***, P < 0.001; ns, P > 0.05.

SRF-mediated transcription can be modulated by two families of coactivators: ternary complex factors (TCFs; i.e., Elk-1) and myocardin-related transcription factors, including megakaryoblastic acute leukemia -1/2 (MKL1/MAL/MRTF-A and MKL2/MRTF-B). Inhibition of endogenous Elk-1 has been previously shown to not affect the BDNF-mediated induction of transcription (33). Thus, we investigated whether MKL1/2 coregulates SRF in the BDNF-stimulated transcription of MMP-9.

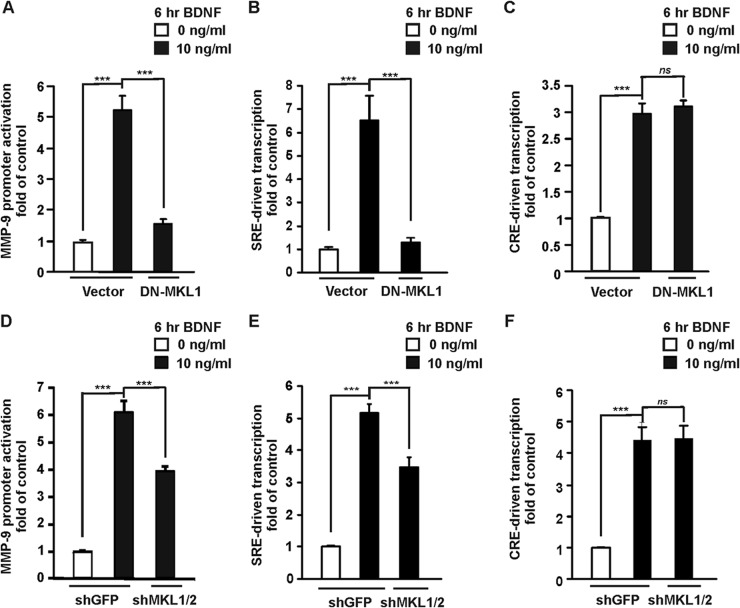

To inhibit endogenous MKL1/2 activity, an expression vector for a Flag-tagged dominant negative (C630) mutant of MKL1 (DN-MKL1) was used (31). This C-terminal deletion mutant lacks the region from amino acid residue 630. Elimination of a putative transactivation domain resulted in a defective MKL1 protein that interacts with SRF, preventing its regulation by endogenous MKL1 and also MKL2 (31). Cortical neurons (4 DIV) were transfected with the indicated luciferase reporter together with a DN-MKL1 expression vector. Three days after transfection, the neurons were treated with BDNF for 6 h. Overexpression of DN-MKL1 strongly inhibited MMP-9 promoter activation (Fig. 8A) as well as SRE-driven transcription (Fig. 8B), but it did not affect CRE-driven transcription (Fig. 8C). Thus, the observed effect was specific.

Fig 8.

Inhibition of SRF coactivators MKL1 and MKL2 by DN-MKL1 mutant or shRNA reduces MMP-9 promoter activation after BDNF stimulation. Cortical neurons (4 DIV) were cotransfected with EF1αLacZ together with the indicated reporter construct and either an empty cloning vector (Vector) or expression construct for a dominant negative mutant form of MKL1 (DN-MKL1) in the presence of a dominant negative p53 construct (p53DD) to reduce transfection toxicity (0.1 μg + 0.1 μg + 1.0 μg + 0.1 μg of plasmid DNA/5 × 105 cells) (A to C) or either a control shRNA (shGFP) or shRNA expression plasmids that targeted MKL1 (shMKL1) and MKL2 (shMKL2) (0.1 μg + 0.1 μg + 0.5 μg + 0.5 μg of plasmid DNA/5 × 105 cells) (D to F). Three days after transfection, the neurons were stimulated with BDNF. Effects of inhibiting endogenous MKL1/2 on the BDNF-mediated activation of the MMP-9 promoter are shown in panels A and D. The increase in MMP-9 promoter activation was significantly reduced with DN-MKL1 and shMKL1/2. Inhibition of MKL1/2 significantly reduced BDNF stimulation of 5×SRE transcriptional activity (B and E) but did not affect CRE-driven transcription (C and F). Data represent triplicate determinations from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate SEM. ***, P < 0.001; ns, P > 0.05.

To confirm that the observed suppression of MMP-9 transcription by DN-MKL1 was indeed attributable to MKL1/2 inhibition and not the consequence of competitive inhibition of other SRF coactivators, we used an shRNA-based strategy to specifically knock down both endogenous MKL1 and MKL2 (shMKL1 and shMKL2, respectively). We confirmed that the shMKL1 and shMKL2 constructs were effective tools for knocking down neuronal MKL1 (33) and MKL2 (data not shown), respectively. At 4 DIV, cortical neurons were cotransfected with one of the following reporter vectors: MMP-9 luc wt, 1×SRE, 1×CRE, and either both shMKL1 and shMKL2 expression plasmids or shRNA that targeted GFP as a control (shGFP). After 72 h, the cells were treated with BDNF for 6 h. Knocking down MKL1/2 by shRNA reduced BDNF-induced MMP-9 promoter activation (Fig. 8D) (P < 0.001) and decreased SRF-driven transcription (Fig. 8E). The effect was specific because shMKL1/2 did not influence the BDNF-mediated stimulation of CRE-driven transcription (Fig. 8F). Altogether, knockdown of MKL1/2 by shRNA led to convergent effects on MMP-9 promoter activation, similar to the observations with DN-MKL1, demonstrating that endogenous MKL1/2 in neurons participates in the BDNF-mediated activation of MMP-9 transcription.

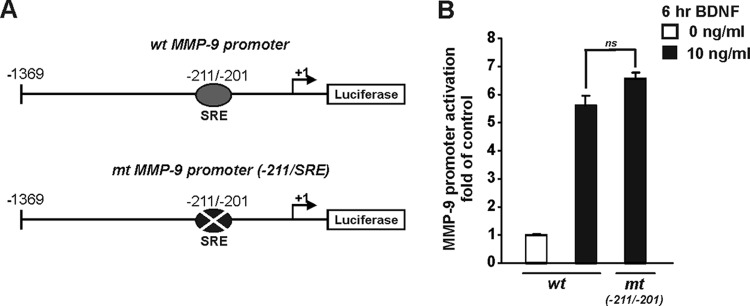

In megakaryocytes, MMP-9 can be directly regulated by the MKL1/SRF complex (49). However, the potential SRF binding site is not a consensus CArG box present in the promoter or enhancer regions of SRF-regulated genes. To test the possibility that SRF directly regulates MMP-9 transcription, we introduced four point mutations into the described SRF binding site (−211/−201) (Fig. 9A). At 5 DIV, cortical neurons were transfected with an MMP-9 reporter vector, either the wild type (MMP-9 luc wt) or the SRE mutant [MMP-9 luc mt(−211/−201)]. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were stimulated with BDNF for 6 h. The mutation of the potential SRF binding site did not affect the BDNF-mediated activation of the MMP-9 promoter (Fig. 9B), demonstrating that this site does not play a role in the regulation of MMP-9 transcription in neurons triggered by BDNF.

Fig 9.

Mutation of potential SRF binding site in MMP-9 promoter does not affect BDNF-mediated MMP-9 transcription. (A) Diagram of the MMP-9 luciferase reporter plasmid. The potential binding site for SRF is indicated. (B) At 5 DIV, cortical neurons were cotransfected with EF1αLacZ together with one of the following MMP-9 reporters: the wild type (MMP-9 luc wt) or a reporter with a potential SRF binding site mutation [MMP-9 luc mt(−211/−201)]. Two days after transfection, the cells were stimulated with BDNF. BDNF-mediated activation of MMP-9 promoter was unaffected by a point mutation of the potential SRF binding site (P > 0.05). The data represent triplicate determinations from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate SEM. ns, nonsignificant.

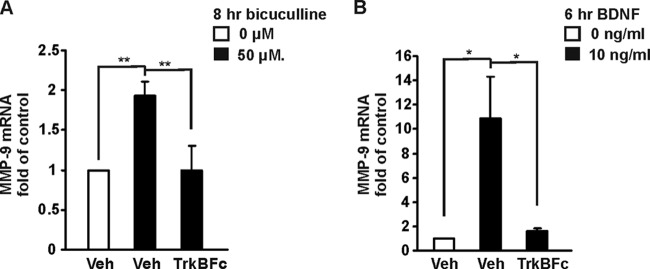

Synaptic activity induces MMP-9 transcription in cortical neurons.

To evaluate whether endogenous BDNF regulates MMP-9 transcription in cortical neurons, we used a GABAA receptor antagonist, bicuculline. Pharmacological stimulation of synaptic activity with bicuculline was shown to increase BDNF expression in neurons (50–52). At 8 DIV, cortical neurons were treated for 8 h with bicuculline. Like BDNF treatment, stimulation of synaptic activity with bicuculline upregulated the MMP-9 level (1.8-fold higher than that of the control) (Fig. 10A). To test whether the observed MMP-9 transcription was activated by increased endogenous levels of BDNF, neurons were treated with bicuculline in the presence of the fusion protein TrkB-Fc, a potent and specific antagonist of BDNF. Pretreatment with TrkB-Fc abolished synaptic activity-induced activation of MMP-9 transcription (Fig. 10A). These data suggest that the observed mRNA upregulation in response to increased neuronal activity was mediated by the TrkB/BDNF-signaling pathway. Similarly, TrkB-Fc was able to inhibit BDNF-induced MMP-9 transcription in cortical neurons (Fig. 10B).

Fig 10.

Synaptic activity induces MMP-9 transcription in cortical neurons. (A) At 8 DIV, cortical neurons were treated for 8 h with bicuculline in the presence or absence of TrkB-Fc. Bicuculline stimulation activated MMP-9 transcription. A 30-min pretreatment with TrkB-Fc abolished bicuculline-mediated upregulation of MMP-9 mRNA. (B) At 8 DIV, cortical neurons were stimulated for 6 h with BDNF in the presence or absence of TrkB-Fc. Pretreatment with TrkB-Fc blocked BDNF-induced MMP-9 transcription. The data represent triplicate determinations from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

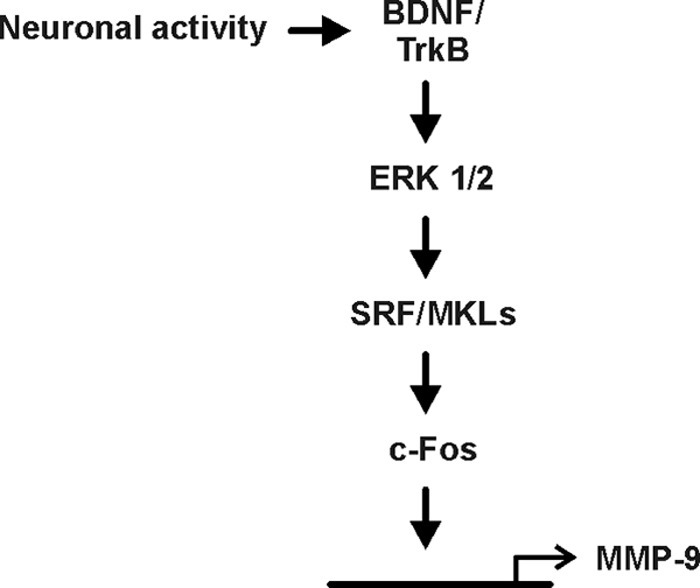

Our data indicate the following: (i) BDNF activates MMP-9 expression in cortical neurons, (ii) the BDNF-mediated transcription of MMP-9 is dependent on ERK1/2 activation, (iii) c-Fos can regulate MMP-9 transcription triggered by BDNF through a proximal (−88/−80) AP-1 binding site present in the MMP-9 promoter, (iv) SRF and its cofactors, MKL1 and MKL2, in contrast to CREB, contribute to BDNF-mediated MMP-9 transcription indirectly through the regulation of c-Fos gene expression, and (v) increased neuronal activity stimulates MMP-9 transcription in a TrkB-dependent manner (Fig. 11). Thus, our data identify a novel relationship between two proplasticity proteins, MMP-9 and BDNF. It has been suggested that MMP-9 is one of the metalloproteinases that may promote precursor BDNF (proBDNF) conversion into mature, biologically active BDNF, playing a pivotal role in plasticity (53–57). Here, we show that in addition to MMP-9 modulation of BDNF activity, BDNF itself can regulate MMP-9 transcription in neurons.

Fig 11.

Schematic diagram illustrating the signal transduction pathway involved in BDNF-mediated MMP-9 expression. BDNF-induced activation of TrkB results in signal propagation through ERK1/2 and leads to activation of SRF/MKL-dependent transcription. The downstream cascade involves transcription of the c-Fos gene, leading to activation of MMP-9 promoter gene expression.

Transcriptional activation plays a major role in regulation of MMP-9 gene expression in different systems. It may appear surprising that the observed induction of MMP-9 mRNA accumulation (4-fold increase) is followed by a smaller increase (1.5-fold) in MMP-9 protein levels and activity under the same culture conditions (Fig. 1B to D). However, it is well established that expression of proteins may also be regulated at the posttranscriptional level. Also, it has been recently shown that MMP-9 mRNA can be transported to dendrites and undergo local translation in response to enhanced neuronal activity (58). Altogether, these results suggest the important role of both transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of MMP-9 expression in neurons.

Our results demonstrate the critical role of c-Fos, which is a component of the AP-1 transcription factor, in the positive regulation of MMP-9 gene expression. Although the regulation of MMP-9 transcription has been well described in various cell types (for a review, see reference 25), the molecular mechanism that controls MMP-9 gene expression in neurons is still underinvestigated. Previous studies in nonneuronal cells reported the regulation of MMP-9 transcription by the AP-1 transcription factor (25, 26). However, many contradictory results have been obtained showing both the positive and negative regulation of MMP-9 gene expression by AP-1 (24, 59–62) and suggesting that the modulation of MMP-9 transcription could be cell specific and depend on cell context and the differential activity of various AP-1 dimers.

AP-1 comprises a family of dimeric protein complexes that consist of either Jun (c-Jun, JunB, and JunD) or Jun and Fos (c-Fos, FosB, Fra-1, and Fra-2) proteins (63). Thus, the variety of dimer compositions results in large differences in transactivating potential and specificity. Furthermore, AP-1 dimer composition has been suggested to be a major factor in the regulation of gene expression in the nervous system (for a review, see reference 64). Our results identify c-Fos as a major player that is important for MMP-9 promoter activation induced by BDNF. Overexpression of tethered AP-1 dimers that contain c-Fos and proteins from the Jun family (c-Jun, JunB, or JunD) resulted in activation of the MMP-9 promoter in neurons, whereas this effect was not observed with other Jun homodimers. Moreover, our results demonstrate the in vivo recruitment of endogenous c-Fos, in response to BDNF stimulation in neurons, to the MMP-9 proximal promoter region. Furthermore, we showed that knockdown of c-Fos expression in neurons reduced the BDNF-mediated activation of MMP-9 transcription. The observed inhibition of MMP-9 mRNA upregulation was not complete, probably due to the limited efficiency of the shRNA knockdown. We demonstrated that shRNA targeting c-Fos blocks the appearance of c-Fos protein upon serum stimulation in RAT-2 cells; however, low levels of c-Fos protein can still be detected. Moreover, under the conditions of c-Fos knockdown, it is possible that other AP-1 family members are responsible for regulation of MMP-9 transcription. As already mentioned, there is a large variety of AP-1 dimer compositions. Our results suggest that, from the AP-1 dimers tested, the most potent are the ones that contain c-Fos protein (Fig. 3A). However, after the overexpression of Jun homodimers, we observed a trend of MMP-9 promoter activation (Fig. 3A). Altogether, our data indicate that c-Fos, which is considered a marker of neuronal activity, plays a critical role in the regulation of MMP-9 expression in response to BDNF stimulation.

There are two functional AP-1 binding sites in the rat MMP-9 gene proximal promoter, located at positions −88/−80 and −514/−507 (65, 66). Our data indicate that the proximal −88/−80 AP-1 binding site is critical for BDNF-mediated MMP-9 transcription, whereas the distal −514/−507 AP-1 binding site does not play a role in this process. These results are consistent with previous findings indicating that the proximal −88/−80 AP-1 binding site is important in MMP-9 gene expression in neurons in response to neuronal depolarization (24). However, in the present study, we found positive regulation of MMP-9 transcription by AP-1 in response to BDNF, whereas Rylski et al. (24) identified JunB as a repressor of MMP-9 gene promoter activity after depolarization. Notably, however, we analyzed the BDNF-mediated induction of MMP-9 transcription and identified c-Fos/AP-1 dimers as major positive regulators in this pathway. In contrast, in a previous report (24) the JunB/FosB AP-1 dimer was found to exert repressive action on MMP-9 gene expression induced by neuronal depolarization. Collectively, these data strongly support the possibility that the AP-1 −88/−80 transcription binding site can exert both a positive and negative influence on MMP-9 gene promoter activation in neurons, depending on the manner of neuronal activation and AP-1 dimer composition.

In the present report, we demonstrate that MMP-9 transcription in neurons is regulated by SRF and its cofactors, MKL1 and MKL2. SRF is a transcription factor that plays a critical role in neuronal activity-induced gene expression, synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory (11, 13, 67–70). Moreover, c-Fos was previously reported to be an SRF target gene regulated in response to neuronal stimulation in the brain in vivo as well as in neurons in vitro. SRF knockout mice exhibit abolished c-Fos induction in response to electroconvulsive shock (11). Moreover, we previously showed that endogenous SRF and its cofactor MKL1 are bound to the c-Fos promoter in rat primary cortical neurons upon BDNF stimulation (33). Additionally, the activity of dominant negative SRF and its functional ability to knock down c-Fos expression in primary neurons have been described previously (13).

Our results indicate that SRF controls MMP-9 gene expression indirectly through the regulation of c-Fos. Interestingly, in HEK293T cells and megakaryocytes, SRF can directly regulate MMP-9 through a potential serum response element (SRE) located in the proximal MMP-9 promoter (49). In contrast to these findings, our data indicate that the potential SRE is not functional in neurons because introducing point mutations in the core of this site did not affect MMP-9 transcription. Furthermore, the aforementioned potential SRF binding site is not a consensus CArG box present in the promoter or enhancer regions of SRF-regulated genes. Thus, consistent with previous findings, MMP-9 gene expression appears to be regulated in a cell-specific manner. Our results show that SRF plays critical role in the regulation of MMP-9 promoter activation in neurons, but it acts indirectly through the activation of c-Fos expression.

In contrast with previous reports showing regulation of MMP-9 expression by CREB and its cofactors in nonneuronal cells (47, 48), our data indicate that in neurons BDNF-induced MMP-9 transcription is not mediated by CREB activity. However, as already mentioned, MMP-9 gene expression seems to be modulated in a cell type/stimulus-specific manner.

Our results demonstrate that MMP-9 transcription is increased by synaptic activity and is dependent on TrkB signaling. It has been shown that increasing synaptic activity with bicuculline induces the expression of BDNF (50–52). Thus, our observations indicate that endogenous BDNF, upregulated in response to bicuculline treatment, regulates MMP-9 expression in neurons. Taking these results together, expression of both BDNF and MMP-9 is modulated by synaptic activity, which is a critical signal activating pathways important for neuronal plasticity.

In summary, we identified a novel signaling cascade activating MMP-9 expression in neurons (Fig. 11). Synaptic activity or BDNF-induced signal propagation involves SRF-dependent transcription of c-Fos, leading to activation of MMP-9 promoter by AP-1 and its binding to the MMP-9 proximal promoter and activation of MMP-9 transcription.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Foundation for Polish Science, Homing Program (K.K.) and a Marie Curie International Reintegration Grant within the 7th European Community Framework Programme under grant agreement number 230992, EpiTarGene (K.K.).

We thank Michal Hetman for critically reading the manuscript and Paul Herring, Marcin Rylski, and Marta Wisniewska for the reagents used in this study.

K.K. designed and performed the experiments and analyzed the data. B.K. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. E.R. performed the experiments. J.J. and A.R.M. designed, constructed, and tested shRNA c-Fos. B.K., K.K., and L.K. wrote the paper. K.K. and L.K. supervised the project.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 March 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Lu Y, Christian K, Lu B. 2008. BDNF: a key regulator for protein synthesis-dependent LTP and long-term memory? Neurobiol. Learn Mem. 89:312–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cohen MS, Orth CB, Kim HJ, Jeon NL, Jaffrey SR. 2011. Neurotrophin-mediated dendrite-to-nucleus signaling revealed by microfluidic compartmentalization of dendrites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:11246–11251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ying SW, Futter M, Rosenblum K, Webber MJ, Hunt SP, Bliss TV, Bramham CR. 2002. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces long-term potentiation in intact adult hippocampus: requirement for ERK activation coupled to CREB and upregulation of Arc synthesis. J. Neurosci. 22:1532–1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Figurov A, Pozzo-Miller LD, Olafsson P, Wang T, Lu B. 1996. Regulation of synaptic responses to high-frequency stimulation and LTP by neurotrophins in the hippocampus. Nature 381:706–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patterson SL, Abel T, Deuel TA, Martin KC, Rose JC, Kandel ER. 1996. Recombinant BDNF rescues deficits in basal synaptic transmission and hippocampal LTP in BDNF knockout mice. Neuron 16:1137–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Messaoudi E, Ying SW, Kanhema T, Croll SD, Bramham CR. 2002. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor triggers transcription-dependent, late phase long-term potentiation in vivo. J. Neurosci. 22:7453–7461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kaplan DR, Miller FD. 2000. Neurotrophin signal transduction in the nervous system. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 10:381–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sgambato V, Pages C, Rogard M, Besson MJ, Caboche J. 1998. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) controls immediate early gene induction on corticostriatal stimulation. J. Neurosci. 18:8814–8825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Valjent E, Caboche J, Vanhoutte P. 2001. Mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase induced gene regulation in brain: a molecular substrate for learning and memory? Mol. Neurobiol 23:83–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Radwanska K, Caboche J, Kaczmarek L. 2005. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) modulate cocaine-induced gene expression in the mouse amygdala. Eur. J. Neurosci. 22:939–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramanan N, Shen Y, Sarsfield S, Lemberger T, Schutz G, Linden DJ, Ginty DD. 2005. SRF mediates activity-induced gene expression and synaptic plasticity but not neuronal viability. Nat. Neurosci. 8:759–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Knoll B, Kretz O, Fiedler C, Alberti S, Schutz G, Frotscher M, Nordheim A. 2006. Serum response factor controls neuronal circuit assembly in the hippocampus. Nat. Neurosci. 9:195–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Etkin A, Alarcon JM, Weisberg SP, Touzani K, Huang YY, Nordheim A, Kandel ER. 2006. A role in learning for SRF: deletion in the adult forebrain disrupts LTD and the formation of an immediate memory of a novel context. Neuron 50:127–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carlezon WA, Jr, Duman RS, Nestler EJ. 2005. The many faces of CREB. Trends Neurosci. 28:436–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meighan SE, Meighan PC, Choudhury P, Davis CJ, Olson ML, Zornes PA, Wright JW, Harding JW. 2006. Effects of extracellular matrix-degrading proteases matrix metalloproteinases 3 and 9 on spatial learning and synaptic plasticity. J. Neurochem. 96:1227–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nagy V, Bozdagi O, Matynia A, Balcerzyk M, Okulski P, Dzwonek J, Costa RM, Silva AJ, Kaczmarek L, Huntley GW. 2006. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 is required for hippocampal late-phase long-term potentiation and memory. J. Neurosci. 26:1923–1934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Michaluk P, Kolodziej L, Mioduszewska B, Wilczynski GM, Dzwonek J, Jaworski J, Gorecki DC, Ottersen OP, Kaczmarek L. 2007. Beta-dystroglycan as a target for MMP-9, in response to enhanced neuronal activity. J. Biol. Chem. 282:16036–16041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Okulski P, Jay TM, Jaworski J, Duniec K, Dzwonek J, Konopacki FA, Wilczynski GM, Sánchez-Capelo A, Mallet J, Kaczmarek L. 2007. TIMP-1 abolishes MMP-9-dependent long-lasting long-term potentiation in the prefrontal cortex. Biol. Psychiatry 62:359–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Michaluk P, Wawrzyniak M, Alot P, Szczot M, Wyrembek P, Mercik K, Medvedev N, Wilczek E, De Roo M, Zuschratter W, Muller D, Wilczynski GM, Mozrzymas JW, Stewart MG, Kaczmarek L, Wlodarczyk J. 2011. Influence of matrix metalloproteinase MMP-9 on dendritic spine morphology. J. Cell Sci. 124:3369–3380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang XB, Bozdagi O, Nikitczuk JS, Zhai ZW, Zhou Q, Huntley GW. 2008. Extracellular proteolysis by matrix metalloproteinase-9 drives dendritic spine enlargement and long-term potentiation coordinately. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:19520–19525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Szklarczyk A, Lapinska J, Rylski M, McKay RD, Kaczmarek L. 2002. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 undergoes expression and activation during dendritic remodeling in adult hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 22:920–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Konopacki FA, Rylski M, Wilczek E, Amborska R, Detka D, Kaczmarek L, Wilczynski GM. 2007. Synaptic localization of seizure-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 mRNA. Neuroscience 150:31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wilczynski GM, Konopacki FA, Wilczek E, Lasiecka Z, Gorlewicz A, Michaluk P, Wawrzyniak M, Malinowska M, Okulski P, Kolodziej LR, Konopka W, Duniec K, Mioduszewska B, Nikolaev E, Walczak A, Owczarek D, Gorecki DC, Zuschratter W, Ottersen OP, Kaczmarek L. 2008. Important role of matrix metalloproteinase 9 in epileptogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 180:1021–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rylski M, Amborska R, Zybura K, Michaluk P, Bielinska B, Konopacki FA, Wilczynski GM, Kaczmarek L. 2009. JunB is a repressor of MMP-9 transcription in depolarized rat brain neurons. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 40:98–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yan C, Boyd DD. 2007. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression. J. Cell. Physiol. 211:19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chakraborti S, Mandal M, Das S, Mandal A, Chakraborti T. 2003. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinases: an overview. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 253:269–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Impey S, Obrietan K, Wong ST, Poser S, Yano S, Wayman G, Deloulme JC, Chan G, Storm DR. 1998. Crosstalk between ERK and PKA is required for Ca2+ stimulation of CREB-dependent transcription and ERK nuclear translocation. Neuron 21:869–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mansour SJ, Matten WT, Hermann AS, Candia JM, Rong S, Fukasawa K, Vande Woude GF, Ahn NG. 1994. Transformation of mammalian cells by constitutively active MAP kinase kinase. Science 265:966–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Poser S, Impey S, Trinh K, Xia Z, Storm DR. 2000. SRF-dependent gene expression is required for PI3-kinase-regulated cell proliferation. EMBO J. 19:4955–4966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chang SH, Poser S, Xia Z. 2004. A novel role for serum response factor in neuronal survival. J. Neurosci. 24:2277–2285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cen B, Selvaraj A, Burgess RC, Hitzler JK, Ma Z, Morris SW, Prywes R. 2003. Megakaryoblastic leukemia 1, a potent transcriptional coactivator for serum response factor (SRF), is required for serum induction of SRF target genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:6597–6608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shaulian E, Zauberman A, Ginsberg D, Oren M. 1992. Identification of a minimal transforming domain of p53: negative dominance through abrogation of sequence-specific DNA binding. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:5581–5592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kalita K, Kharebava G, Zheng JJ, Hetman M. 2006. Role of megakaryoblastic acute leukemia-1 in ERK1/2-dependent stimulation of serum response factor-driven transcription by BDNF or increased synaptic activity. J. Neurosci. 26:10020–10032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ahn S, Olive M, Aggarwal S, Krylov D, Ginty DD, Vinson C. 1998. A dominant-negative inhibitor of CREB reveals that it is a general mediator of stimulus-dependent transcription of c-fos. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:967–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Klejman A, Kaczmarek L. 2006. Inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER) isoforms and neuronal apoptosis in cortical in vitro culture. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. (Wars.) 66:267–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yin F, Hoggatt AM, Zhou J, Herring BP. 2006. 130-kDa smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase is transcribed from a CArG-dependent, internal promoter within the mouse mylk gene. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 290:C1599–1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bakiri L, Matsuo K, Wisniewska M, Wagner EF, Yaniv M. 2002. Promoter specificity and biological activity of tethered AP-1 dimers. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:4952–4964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brummelkamp TR, Bernards R, Agami R. 2002. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science 296:550–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Habas A, Kharebava G, Szatmari E, Hetman M. 2006. NMDA neuroprotection against a phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase inhibitor, LY294002 by NR2B-mediated suppression of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta-induced apoptosis. J. Neurochem. 96:335–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mullenbrock S, Shah J, Cooper GM. 2011. Global expression analysis identified a preferentially nerve growth factor-induced transcriptional program regulated by sustained mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and AP-1 protein activation during PC12 cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 286:45131–45145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rylski M, Amborska R, Zybura K, Mioduszewska B, Michaluk P, Jaworski J, Kaczmarek L. 2008. Yin Yang 1 is a critical repressor of matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in brain neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 283:35140–35153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kaczmarek L. 1993. Molecular biology of vertebrate learning: is c-fos a new beginning? J. Neurosci. Res. 34:377–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kaczmarek L, Chaudhuri A. 1997. Sensory regulation of immediate-early gene expression in mammalian visual cortex: implications for functional mapping and neural plasticity. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 23:237–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kaczmarek L, Lapinska-Dzwonek J, Szymczak S. 2002. Matrix metalloproteinases in the adult brain physiology: a link between c-Fos, AP-1 and remodeling of neuronal connections? EMBO J. 21:6643–6648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jaworski J, Spangler S, Seeburg DP, Hoogenraad CC, Sheng M. 2005. Control of dendritic arborization by the phosphoinositide-3′-kinase-Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. J. Neurosci. 25:11300–11312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xia Z, Dudek H, Miranti CK, Greenberg ME. 1996. Calcium influx via the NMDA receptor induces immediate early gene transcription by a MAP kinase/ERK-dependent mechanism. J. Neurosci. 16:5425–5436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Park JK, Park SH, So K, Bae IH, Yoo YD, Um HD. 2010. ICAM-3 enhances the migratory and invasive potential of human non-small cell lung cancer cells by inducing MMP-2 and MMP-9 via Akt and CREB. Int. J. Oncol. 36:181–192 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tsai LN, Ku TK, Salib NK, Crowe DL. 2008. Extracellular signals regulate rapid coactivator recruitment at AP-1 sites by altered phosphorylation of both CREB binding protein and c-jun. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:4240–4250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gilles L, Bluteau D, Boukour S, Chang Y, Zhang Y, Robert T, Dessen P, Debili N, Bernard OA, Vainchenker W, Raslova H. 2009. MAL/SRF complex is involved in platelet formation and megakaryocyte migration by regulating MYL9 (MLC2) and MMP9. Blood 114:4221–4232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zafra F, Castren E, Thoenen H, Lindholm D. 1991. Interplay between glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid transmitter systems in the physiological regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and nerve growth factor synthesis in hippocampal neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:10037–10041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jia JM, Chen Q, Zhou Y, Miao S, Zheng J, Zhang C, Xiong ZQ. 2008. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-tropomyosin-related kinase B signaling contributes to activity-dependent changes in synaptic proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 283:21242–21250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Verpelli C, Piccoli G, Zibetti C, Zanchi A, Gardoni F, Huang K, Brambilla D, Di Luca M, Battaglioli E, Sala C. 2010. Synaptic activity controls dendritic spine morphology by modulating eEF2-dependent BDNF synthesis. J. Neurosci. 30:5830–5842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hwang JJ, Park MH, Choi SY, Koh JY. 2005. Activation of the Trk signaling pathway by extracellular zinc. Role of metalloproteinases. J. Biol. Chem. 280:11995–12001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lee R, Kermani P, Teng KK, Hempstead BL. 2001. Regulation of cell survival by secreted proneurotrophins. Science 294:1945–1948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mizoguchi H, Nakade J, Tachibana M, Ibi D, Someya E, Koike H, Kamei H, Nabeshima T, Itohara S, Takuma K, Sawada M, Sato J, Yamada K. 2011. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 contributes to kindled seizure development in pentylenetetrazole-treated mice by converting Pro-BDNF to mature BDNF in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 31:12963–12971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pang PT, Teng HK, Zaitsev E, Woo NT, Sakata K, Zhen S, Teng KK, Yung WH, Hempstead BL, Lu B. 2004. Cleavage of proBDNF by tPA/plasmin is essential for long-term hippocampal plasticity. Science 306:487–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yang J, Siao CJ, Nagappan G, Marinic T, Jing D, McGrath K, Chen ZY, Mark W, Tessarollo L, Lee FS, Lu B, Hempstead BL. 2009. Neuronal release of proBDNF. Nat. Neurosci. 12:113–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dziembowska M, Milek J, Janusz A, Rejmak E, Romanowska E, Gorkiewicz T, Tiron A, Bramham CR, Kaczmarek L. 2012. Activity-dependent local translation of matrix metalloproteinase-9. J. Neurosci. 32:14538–14547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Troussard AA, Costello P, Yoganathan TN, Kumagai S, Roskelley CD, Dedhar S. 2000. The integrin linked kinase (ILK) induces an invasive phenotype via AP-1 transcription factor-dependent upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9). Oncogene 19:5444–5452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kobayashi T, Kishimoto J, Hattori S, Wachi H, Shinkai H, Burgeson RE. 2004. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression is coordinately modulated by the KRE-M9 and 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate responsive elements. J. Investig. Dermatol. 122:278–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Crowe DL, Brown TN. 1999. Transcriptional inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) activity by a c-fos/estrogen receptor fusion protein is mediated by the proximal AP-1 site of the MMP-9 promoter and correlates with reduced tumor cell invasion. Neoplasia 1:368–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Moon SK, Kim HM, Kim CH. 2004. PTEN induces G1 cell cycle arrest and inhibits MMP-9 expression via the regulation of NF-κB and AP-1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 421:267–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Morgan JI, Curran T. 1991. Stimulus-transcription coupling in the nervous system: involvement of the inducible proto-oncogenes fos and jun. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 14:421–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Perez-Cadahia B, Drobic B, Davie JR. 2011. Activation and function of immediate-early genes in the nervous system. Biochem. Cell Biol. 89:61–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yang JQ, Zhao W, Duan H, Robbins ME, Buettner GR, Oberley LW, Domann FE. 2001. v-Ha-RaS oncogene upregulates the 92-kDa type IV collagenase (MMP-9) gene by increasing cellular superoxide production and activating NF-κB. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 31:520–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Eberhardt W, Schulze M, Engels C, Klasmeier E, Pfeilschifter J. 2002. Glucocorticoid-mediated suppression of cytokine-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in rat mesangial cells: involvement of nuclear factor-kappaB and Ets transcription factors. Mol. Endocrinol. 16:1752–1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dash PK, Orsi SA, Moore AN. 2005. Sequestration of serum response factor in the hippocampus impairs long-term spatial memory. J. Neurochem. 93:269–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lindecke A, Korte M, Zagrebelsky M, Horejschi V, Elvers M, Widera D, Prüllage M, Pfeiffer J, Kaltschmidt B, Kaltschmidt C. 2006. Long-term depression activates transcription of immediate early transcription factor genes: involvement of serum response factor/Elk-1. Eur. J. Neurosci. 24:555–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nikitin VP, Kozyrev SA. 2007. Transcription factor serum response factor is selectively involved in the mechanisms of long-term synapse-specific plasticity. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 37:83–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Johnson AW, Crombag HS, Smith DR, Ramanan N. 2011. Effects of serum response factor (SRF) deletion on conditioned reinforcement. Behav. Brain Res. 220:312–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]