Abstract

Herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) is an important human pathogen that is the major cause of genital herpes infections and a significant contributor to the epidemic spread of human immunodeficiency virus infections. The UL21 gene is conserved throughout the Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily and encodes a tegument protein that is dispensable for HSV-1 and pseudorabies virus replication in cultured cells; however, its precise functions have not been determined. To investigate the role of UL21 in the HSV-2 replicative cycle, we constructed a UL21 deletion virus (HSV-2 ΔUL21) using an HSV-2 bacterial artificial chromosome, pYEbac373. HSV-2 ΔUL21 was unable to direct the production of infectious virus in noncomplementing cells, whereas the repaired HSV-2 ΔUL21 strain grew to wild-type (WT) titers, indicating that UL21 is essential for virus propagation. Cells infected with HSV-2 ΔUL21 demonstrated a 2-h delay in the kinetics of immediate early viral gene expression. However, this delay in gene expression was not responsible for the inability of cells infected with HSV-2 ΔUL21 to produce virus insofar as late viral gene products accumulated to WT levels by 24 h postinfection (hpi). Electron and fluorescence microscopy studies indicated that DNA-containing capsids formed in the nuclei of ΔUL21-infected cells, while significantly reduced numbers of capsids were located in the cytoplasm late in infection. Taken together, these data indicate that HSV-2 UL21 has an early function that facilitates viral gene expression as well as a late essential function that promotes the egress of capsids from the nucleus.

INTRODUCTION

Genital infections with herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) are among the most common sexually transmitted diseases worldwide (1). Furthermore, HSV-2 infection both facilitates the acquisition and transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and is fuelling the epidemic spread of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa (2, 3). Despite its prevalence in the human population, HSV-2 has not been as intensively studied as the related pathogen HSV-1. HSV-1 and HSV-2 share roughly 83% nucleotide identity in protein coding regions and were estimated to diverge from each other roughly 8.4 million years ago (4, 5). Notwithstanding the considerable homology between these viruses, HSV-1 and HSV-2 have demonstrably different properties in terms of both pathogenesis and their interactions with permissive cells (6–8). An understanding of the molecular basis for the differences between HSV-1 and HSV-2 activities is expected to provide insight into the distinct clinical manifestations exhibited by these important human pathogens.

The HSV-2 genome is approximately 155 kbp in length and is predicted to encode at least 74 different proteins (4). The majority of these gene products are packaged into the virion and are either capsid, tegument, or envelope components. Located between the virion capsid and envelope, the tegument is the most complex subvirion compartment. In HSV-1 virions, the tegument is comprised of an estimated 23 virus-encoded components and at least 49 host cell proteins (9). Compositional analysis of the related swine pathogen pseudorabies virus (PRV) has revealed a similar virion complexity (10). The present study was initiated to determine the function of the HSV-2 tegument protein encoded by the UL21 gene.

While often reported in the literature to be conserved throughout the Herpesviridae, our recent analysis using the resources of the Virus Pathogen Database (http://www.viprbrc.org/) indicated that the HSV-2 UL21 gene is conserved only among members of the Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily. HSV-1 UL21 null mutants are replication competent but demonstrate a delay in the transcription of immediate early virus gene products and delayed production of infectious virus; however, virus production is reduced by only 3- to 10-fold by late times postinfection (11, 12). Discrepancies exist between the reported phenotypes of PRV UL21 mutants. When UL21 expression was eliminated from the PRV NIA-3 strain, the virus grew poorly in cell culture and demonstrated defects in capsid maturation, specifically the cleavage and packaging of viral DNA into capsids (13, 14). In contrast, deletion of UL21 from the PRV Kaplan strain led to only modest defects in virus replication in cultured cells, with no apparent defects in capsid maturation (15, 16). UL21 mutations in both strains led to reductions in plaque size and attenuated virulence in mice and in swine (13, 16, 17).

In PRV- and HSV-1-infected cells, UL21 localizes predominantly to the cytoplasm, with some diffuse nuclear localization also evident (11, 15, 18). UL21 is a capsid-associated tegument protein that forms a complex with two other tegument proteins, the capsid-associated protein UL16 and the lipid-modified, trans-Golgi network (TGN) membrane-associated protein UL11 (15, 19–26). Recently, Han and colleagues reported that HSV-1 UL11, UL16, and UL21 form a complex on the cytoplasmic tail of the viral glycoprotein gE and that this complex is required for appropriate gE processing, trafficking, and gE modulation of membrane fusion (27). Whereas UL11 does not interact directly with UL21, UL16 is capable of binding simultaneously to UL21 and UL11 (20). The C-terminal half of UL21 contains sequences capable of interacting directly with UL16, and UL11 contains leucine-isoleucine and acidic motifs required for its interaction with UL16 (28). Because deletion of UL11 from HSV-1 results in the accumulation of nonenveloped capsids in the cytoplasm, it has been suggested that another function of the UL11/UL16/UL21 complex is to promote the interaction of cytoplasmic capsids with the cytoplasmic face of the TGN, a proposed site of final virion envelopment (22, 29, 30). Interestingly, UL11 also associates with nuclear membranes, and an HSV-1 UL11 deletion mutant accumulates roughly three times more capsids at the inner nuclear membrane (INM) than wild-type (WT) or repaired strains (19, 29). As UL16 and UL21 can also be found in the nuclei of virus-infected cells (11, 15, 18, 24), it is possible that the UL11/UL16/UL21 complex also has nuclear functions.

The aim of this study was to characterize the HSV-2 UL21 gene product and to isolate a UL21 null mutant (HSV-2 ΔUL21) in order to determine its function in the virus replicative cycle. Here we show that, unlike what has been observed for HSV-1 or PRV, HSV-2 UL21 is essential for virus propagation and that it functions in both early and late stages of the virus replicative cycle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells.

All HSV-2 mutant viruses were derived from the HSV-2 strain 186 bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) pYEbac373. HSV-2 strain 186 was a kind gift from David Knipe, Harvard University. The African green monkey kidney (Vero) cell line was provided by the ATCC, and the murine L fibroblast cell (L cell) line was a kind gift from Frank Tufaro, University of British Columbia. The amphotropic Phoenix cell line (31) was kindly provided by Craig McCormick, Dalhousie University. All cell lines were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

Plasmids.

To fuse enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) to the C terminus of HSV-2 UL21 (pUL21-GFP), the full-length HSV-2 UL21 DNA sequence was obtained by PCR amplification using primers 5′-TCA TCA GAA TTC ATG GAG CTC AGC TAT GCC A-3′ and 5′-TCA TCA CTC GAG TCA CAC AGA CTG GCC GTG-3′ with HSV-2 strain 186 viral DNA as the template. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and EcoRI and ligated into similarly digested pEGFP-N1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). An N-terminal EGFP fusion (pGFP-UL21) was constructed by using primers 5′-TCA TCA TCC GGA ATG GAG CTC AGC TAT GCC A-3′ and 5′-TCA TCA CTC GAG TCACAC AGA CTG GGC GTG-3′ with viral HSV-2 strain 186 DNA as the template. The PCR product was digested with BspEI and XhoI and ligated into similarly digested pEGFP-C1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). An untagged UL21 construct (pUL21) was produced by ligation of the UL21 DNA sequence into the EcoRI restriction site of pCI-neo (Promega, Madison, WI). UL21 was amplified from pUL21-GFP by using primers 5′-TCA TCA GAA TTC ATG GAG CTC AGC TAT GCC A-3′ and 5′-TCA TCA GAA TTC TCA CAC AGA CTG GCC GTG-3′. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI, and directionality of cloning was confirmed by digestion with SalI.

pBMN-IP-UL21 was used to construct a UL21-expressing retrovirus. To construct pBMN-IP-UL21, the UL21 gene was amplified from pUL21-GFP with forward (5′-TCA TCA GAA TTC ATG GAG CTC AGC TAT GCC A-3′) and reverse (5′-TCA TCA CTC GAG TCA CAC AGA CTG GCC GTG-3′) primers that introduced EcoRI and XhoI sites, respectively. The resulting PCR product was subsequently digested with these restriction enzymes and inserted into the similarly digested pBMN-IP retroviral vector, provided by Craig McCormick, Dalhousie University.

For production of polyclonal antisera against HSV-2 UL21, codons 149 to 384 were amplified by PCR using primers 5′-GAT CGG ATC CAT GCA CCC GGC GAT CGT CAA CAT TTC C-3′ and 5′-GAT CGA ATT CTC ACA CAG ACT GGC CGT GCT GGG-3′ from HSV-2 strain HG52 DNA. The PCR fragment was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and ligated into similarly digested pGEX4T-1 (GE Healthcare, Louisville, KY). The resulting plasmid, pGEX-UL21, was used to produce a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-UL21 fusion protein.

For production of polyclonal antisera against HSV-2 ICP0, PCR was performed by using primers 5′-GAT CGG ATC CGG CGC TGG GGA GAG ACG AGA AAC C-3′ and 5′-GAT CGT CGA CCC GAG TGT TAG CTC CCC CTA CTC C-3′ and HSV-2 strain HG52 DNA as the template to amplify the DNA sequence corresponding to ICP0 codons 639 to 825. The PCR fragment was digested with BamHI and SalI and ligated into similarly digested pGEX4T-1 (GE Healthcare, Louisville, KY). The resulting plasmid, pGEX-ICP0, was used to produce a GST-ICP0 fusion protein.

Plasmid transfections of Vero cells were carried out by using FuGene HD (Roche, Laval, QC, Canada) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Protein expression and production of antisera.

Recombinant HSV-2 GST-UL21 and GST-ICP0 proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli strain Rosetta(DE3) after induction with 0.2 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 4 h at 37°C. Bacteria were lysed, and inclusion bodies were purified by using the B-Per protein purification kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Proteins in inclusion bodies were separated on preparative SDS-PAGE gels, and the bands corresponding to GST fusions were excised and sent to Cedarlane Laboratories (Burlington, ON, Canada) to immunize Wistar rats for polyclonal antiserum production.

Antibodies.

Rat polyclonal antiserum against UL21 was used for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy at a dilution of 1:1,000 and Western blotting at a dilution of 1:3,000, rat polyclonal antiserum against HSV-2 ICP0 was used for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy at a dilution of 1:200, mouse monoclonal antibody against HSV ICP27 (Virusys, Sykesville, MD) was used for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy and for Western blotting at a dilution of 1:1,000, mouse monoclonal antibody against HSV-2 ICP8 (Virusys, Sykesville, MD) was used for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy at a dilution of 1:10,000 and for Western blotting at a dilution of 1:16,000, rat polyclonal antiserum against HSV Us3 (32) was used for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy at a dilution of 1:1,000 and for Western blotting at a dilution of 1:500, mouse monoclonal antibody against HSV ICP5 (Virusys, Sykesville, MD) was used for Western blotting at a dilution of 1:3,000, mouse monoclonal antibody against HSV gD (Virusys, Sykesville, MD) was used for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy at a dilution of 1:1,000 and for Western blotting at a dilution of 1:80,000, and mouse monoclonal antiserum against VP16 (Virusys, Sykesville, MD) was used for Western blotting at a dilution of 1:2,000 and for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy at a dilution of 1:100. Rabbit monoclonal anti-Flag antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used at a dilution of 1:100 for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G monoclonal antibody, Alexa Fluor 633-conjugated goat anti-chicken immunoglobulin G monoclonal antibody, and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-rat immunoglobulin G monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) were used at a dilution of 1:500 for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-rat IgG (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were used for Western blotting at dilutions of 1:5,000 and 1:80,000, respectively.

Construction of recombinant HSV-2 strains.

pYEbac373, the full-length infectious HSV-2 186 BAC, was constructed essentially as described previously (33), except that HSV-2 strain 186 was used. The HSV-2 mutant lacking the UL21 gene (pYEbac373-ΔUL21) was constructed by the two-step Red-mediated mutagenesis procedure (34), using pYEbac373 in E. coli GS1783. Primers 5′-CCA CTA TTC CCC CCC CCA AGT CCG CCC CGT GGC TCG CCG GCC ATG TGA GAT ATC CCA ATA AGG ATG ACG ACG ATA AGT AGG G-3′ and 5′-GCA TCC GTG GGT TAG AAA ACG ACT GCA CTT TAT TGG GAT ATC TCA CAT GGC CGG CGA GCC CAA CCA ATT AAC CAA TTC TGA TTA G-3′ were used to amplify a PCR product from pEP-Kan-S2, a kind gift of Klaus Osterrieder, Freie Universität Berlin, and used to completely remove the UL21 coding sequence, leaving only the first and last codons (underlined). HSV-2 ΔUL21 was repaired (HSV-2 ΔUL21R) by cotransfection of pYEbac373-ΔUL21 and a PCR product containing the UL21 coding sequence as well as flanking up- and downstream sequences (5′-CCA AAT CAT GGG TGG ATG TG-3′ and 5′-CAC CCC GAA CGT GTT TTC C-3′).

A C-terminal Flag tag fused to UL21 (pYEbac373-UL21-Flag) was constructed, as described above, with primers 5′-GCT TAC CGT TTG CCT GGC TCG CGC CCA GCA CGG CCA GTC TGT GGA TTA CAA GGA TGA CGA CGA TAA G-3′ and 5′-TGG GTT AGA AAA CGA CTG CAC TTT ATT GGG ATA TCT CAC TAC TTA TCG TCG TCA TCC TTG TAA TCC AAC CAA TTA ACC AAT TCT GAT T-3′.

An N-terminal mCherry tag fused to the capsid protein VP26 (pYEbac373-mCh-VP26) was constructed, as described above, with primers 5′-GAC GTT GTC GGC GGT AAT GGT GCT GGG GCG GTG AAA CTG CGG GGC CTT GTA CAG CTC GTC-3′ and 5′-GCC TCC GGC CCG ATT CTT ACG GCG CGA CCC AAG GTC CCG ATG GCC GTG AGC AAG GGC GAG-3′.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis was used to confirm the integrity of each recombinant BAC clone compared to the WT BAC by digestion with EcoRI. Additionally, a PCR fragment that spanned the mutated region of interest was amplified and sequenced to confirm the deletion or appropriate protein fusion.

Virus reconstitution.

To produce HSV-2 186 strains that lacked the BAC DNA sequences, we cotransfected WT or recombinant pYEbac373 and the nuclear localization signal (NLS)-Cre-expressing plasmid pOG231 (35) into Vero cells. Briefly, Vero cells were trypsinized and resuspended in DMEM–10% FBS containing 10 mM N,N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid, N,N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)taurine (BES) (pH 7.2) to a concentration of 4 × 107 cells/ml. pYEbac373 and pOG231 (1 μg each) were added to a 250-μl cell suspension in the presence or absence of 1 μg pUL21 and were then transferred into an electroporation cuvette (0.4-cm gap; Fisher Scientific, Toronto, ON, Canada). Electroporation was carried out at settings of 210 V, 950 μF, and 200 Ω by using a BTX ECM 630 electroporator. Cells and DNA were immediately plated onto an empty 100-mm dish or dishes containing ∼3 × 106 L21 cells, and the infection was allowed to proceed for up to 3 days. Supernatants were collected, and WT or recombinant HSV-2 186 strains were plaque purified twice on Vero or complementing L21 cells.

Isolation of L21 cells.

The complementing UL21-expressing cell line L21 was derived from L cells and produced by using an amphotropic Phoenix-Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) system (31) and plasmid pBMN-IP-UL21. L cells were infected with retrovirus containing UL21 sequences in the presence of 5 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 4 h. Stably transduced cells were established by selection with 5 μg/ml puromycin (Cedarlane Laboratories, Burlington, ON, Canada). Drug-resistant colonies were selected and expanded, and expression of UL21 was confirmed by Western blotting.

Analysis of UL21 expression kinetics.

One hour prior to infection, confluent monolayers of Vero cells growing in 6-well plates were incubated with or without 400 μg/ml phosphonoacetic acid (PAA) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Cells were infected with the HSV-2 WT at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5.0. At the indicated times postinfection, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were scraped into 60 μl of cold PBS containing protease inhibitors (Roche, Laval, QC, Canada) and transferred into a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube containing 30 μl 3× SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Samples were passed through a 28½-gauge syringe needle to reduce viscosity, heated to 100°C for 5 min, and analyzed by Western blotting.

Virion purification.

L and L21 cells were infected at an MOI of 3.0 with HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, and ΔUL21R strains. At 36 h postinfection (hpi), the infected-cell medium was harvested, and cell debris was removed by low-speed centrifugation. The viral suspension was layered onto a 25% sucrose–TN buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.4]) cushion and centrifuged in a Beckman SW41 rotor at 23,000 rpm for 3 h. The pelleted virions were resuspended in 1× SDS-PAGE loading buffer, immediately electrophoresed through SDS-PAGE gels, and analyzed by Western blotting.

Western blotting.

Proteins in samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA) that were subsequently blocked with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA). After blocking, the membranes were probed with appropriate dilutions of primary antibody followed by appropriate dilutions of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, and proteins were detected by using Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) and exposed to film.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

For indirect immunofluorescence microscopy, Vero cells were seeded onto glass-bottom dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA). Cells were infected, washed three times with PBS at the indicated times postinfection, and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde–PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Fixed cells were washed with PBS containing 1% BSA (PBS-BSA) and permeabilized with PBS-BSA containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 3 min. Cells were again washed three times in PBS-BSA, and primary antiserum, diluted in PBS-BSA, was applied for 45 min at room temperature. Cells were washed with PBS-BSA, and the appropriate Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibody diluted in PBS-BSA was applied for 30 min. Cells were then washed with PBS-BSA. Nuclei were visualized by incubating cells with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) diluted to 0.5 μg/ml in PBS. Images were captured by using an Olympus FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope and Fluoview 2.01 software through a 60×, 1.42-numerical-aperture (NA), oil immersion objective and a digital zoom factor of 3. Composites are representative images that were assembled by using Adobe Photoshop CS3.

Analysis of virus replication kinetics.

Virus growth analysis was performed by using L and L21 cells growing in 35-mm dishes. Cells were infected with the HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, or ΔUL21R strain at an MOI of 0.1 or 1.0. After 1 h of absorption at 37°C, the inoculum was removed, extracellular virus was inactivated with a low-pH wash (40 mM citric acid [pH 3.0], 10 mM KCl, 135 mM NaCl) for 3 min, and DMEM containing 10% FBS was added to each culture. Cells were scraped into the medium at the indicated times postinfection, and virus titers were determined by plaque assays on L21 cell monolayers.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR.

Vero cells were infected with HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, and ΔUL21R strains at an MOI of 0.1. At 2, 4, and 6 hpi, total RNA was extracted from cells by using TRI RNA isolation reagent (Molecular Research Center Inc., Cincinnati, OH) or TRIzol RNA isolation reagent (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON, Canada), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA (1 μg) was treated with DNase I (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to eliminate any contaminating DNA. Reverse transcription (RT) of 1 μg total RNA was performed by using MMLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON, Canada). To quantify the levels of ICP0, ICP27, ICP8, gC, and 18S rRNA transcripts, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed by using SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada) with the following primer sets: ICP0 forward primer 5′-ACCATCCCGATAGTGAACGA-3′, ICP0 reverse primer 5′-TTGCCCGTCCAGATAAAGTCCA-3′, ICP27 forward primer 5′-TTCTGCGATCCATATCCGAGC-3′, ICP27 reverse primer 5′-AAACGGCATCCCGCCAAA-3′, ICP8 forward primer 5′-AGGACATAGAGACCATCGCGTTCA-3′, ICP8 reverse primer 5′-TGGCCAGTTCGCTCACGTTATT-3′, gC forward primer 5′-AAATCCGATGCCGGTTTCCCAA-3′, gC reverse primer 5′-TTACCATCACCTCCTCTAAGCTAGGC-3′, 18S rRNA forward primer 5′-TTCGGAACTGAGGCCATGAT-3′, and 18S rRNA reverse primer 5′-CGAACCTCCGACTTTCGTTT-3′. PCR cycling was performed with a CFX96 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada). The amount of each viral mRNA relative to the amount of18S rRNA was calculated by the ΔCT method as follows: relative ratio = 2∧(18S rRNA CT [threshold cycle] − viral transcript CT). Values were normalized to the value for HSV-2 WT-infected cells at 2 hpi, which was arbitrarily set to 1.0. Reactions were performed in duplicate for each biological specimen, and three biological replicates were analyzed under each condition.

Electron microscopy.

Electron microscopy was performed as previously described (36). Briefly, Vero cells were infected at an MOI of 1.0 with the HSV-2 ΔUL21, ΔUL21R, or HSV-2 WT strain. At 14 hpi, cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 100 mM sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 30 min at room temperature and 90 min at 4°C. Cells were rinsed three times for 5 min each with cacodylate buffer and then fixed in 2% OsO4 in cacodylate buffer at room temperature for 2 h. Cells were again rinsed three times for 5 min each with cacodylate buffer and then dehydrated through a series of increasing ethanol concentrations, followed by dehydration with a 1:1 mixture of ethanol-acetone and then twice with 100% acetone. The cells were infiltrated with increasing concentrations of Epon-Araldite until fully embedded in 100% Epon-Araldite and then cured at 70°C overnight in Beem capsules. Thin sections (60 nm) were examined, and images were collected by using an FEI Tecnai-T12 BioTWIN transmission electron microscope. For quantification, total numbers of capsids as well as numbers of cytoplasmic capsids were counted in 10 independent sections for each strain. Statistical analysis, balanced one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), was performed by using MATLAB software (MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Quantitative analysis of nuclear egress.

A UL21 null virus containing mCherry fused to the N terminus of the capsid protein VP26, referred to as ΔUL21/mCh-VP26, was constructed to quantify capsid localization during virus infection. To construct this strain, L21 cells were coinfected with the ΔUL21 and WT/mCh-VP26 strains. Viruses produced from the coinfection were harvested, and mCherry-expressing plaques were isolated from infected L21 monolayers. Isolates that formed plaques on L21 monolayers but not on noncomplementing L cell monolayers were identified, and loss of UL21 expression was confirmed. Vero cells were inoculated with either the ΔUL21/mCh-VP26 strain or the WT/mCh-VP26 strain at an MOI of 0.01. At 18 hpi, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min and stained with Hoechst 33342 to visualize nuclei. z series of cells were acquired with a step size of 0.4 μm by using an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope equipped with a 60×, 1.42-NA, oil immersion objective and a digital zoom factor ranging between 2 and 5. Three-dimensional reconstructions were then used for the quantification of cytoplasmic capsids in 21 to 24 infected cells for each strain. Capsid counting was facilitated with Fluoview 2.01 software.

RESULTS

Characterization of the HSV-2 UL21 gene product.

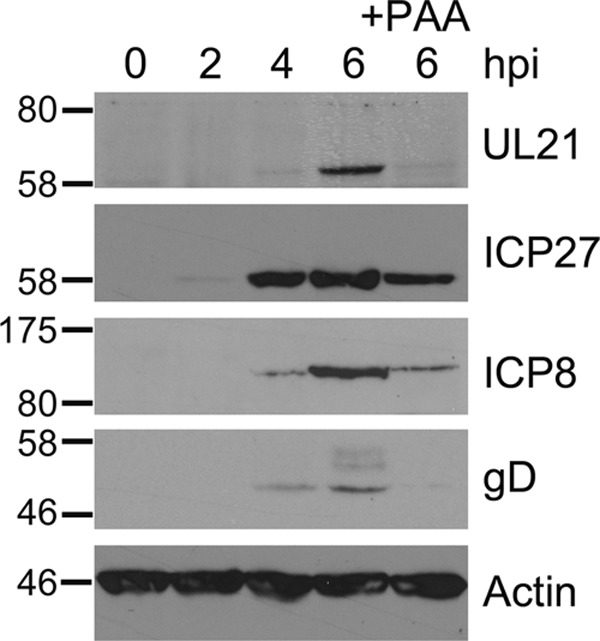

Herpesvirus genes are grouped into four kinetic classes: immediate early (IE), early (E), late (L), and leaky late (LL). IE genes are expressed first, followed by the E genes that are expressed prior to viral DNA replication. L gene expression is dependent on viral DNA replication, whereas LL genes are expressed poorly if viral DNA synthesis is inhibited (37). To determine the kinetics of expression of HSV-2 UL21, Vero cells were infected with HSV-2 at an MOI of 5.0 in the presence or absence of PAA, an inhibitor of viral DNA synthesis. The expression of UL21 in total cell lysates was compared to the expression of representative IE (ICP27), E (ICP8), and L (gD) gene products by Western blotting (Fig. 1). Expression of the L gene HSV-2 gD was inhibited in the presence of PAA, whereas the expression of the IE and E gene products were only modestly affected. UL21 was detected as an approximately 62-kDa band at 4 hpi, and its expression was inhibited by the addition of PAA, indicating that, similar to HSV-1 UL21 (11), HSV-2 UL21 is expressed as an L gene product.

Fig 1.

HSV-2 UL21 is expressed as a late gene. Vero cells were infected at an MOI of 5.0 with HSV-2 WT in the absence or presence of 400 ng/ml PAA. At the indicated times postinfection, total cell lysates were collected, electrophoresed through 10% polyacrylamide gels, and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Membranes were probed with the antisera indicated on the right. The UL21 gene of HSV-2 encodes a 532-amino-acid protein with a predicted mass of 58 kDa. Molecular mass markers in kDa are shown on the left.

Localization of HSV-2 UL21.

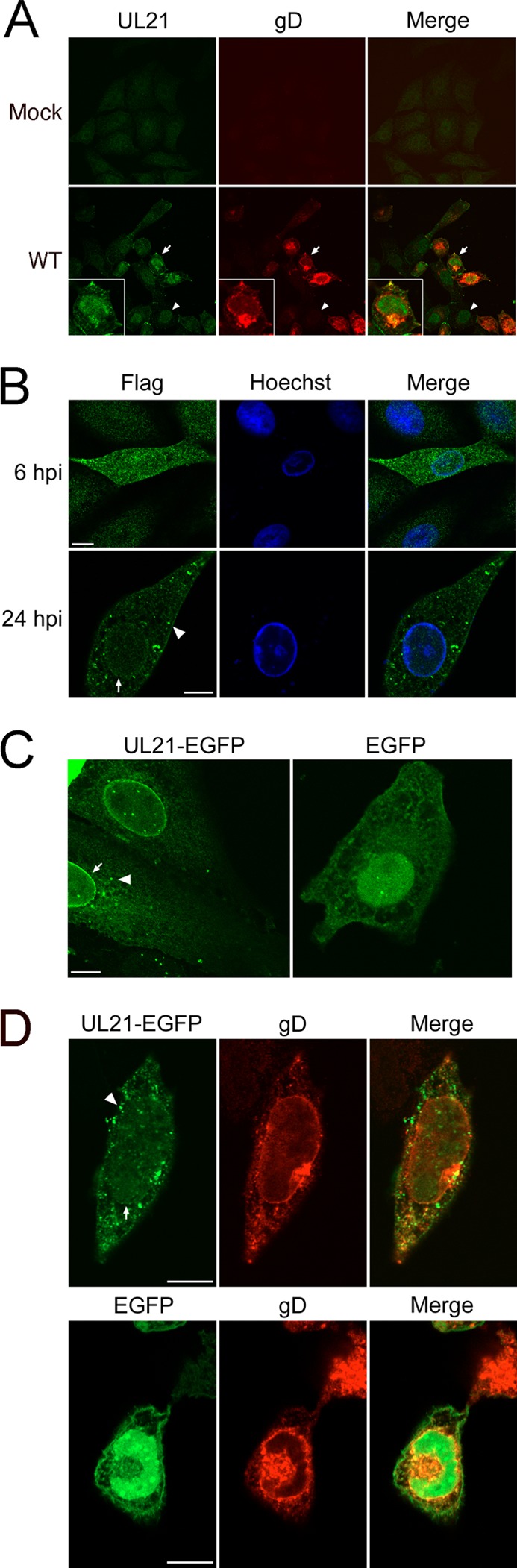

To gain insight into the function of HSV-2 UL21, we investigated the subcellular localization of UL21 in infected cells. Vero cells were infected with HSV-2, fixed at 6 hpi, and stained for UL21 and gD. With the exception of distinct cytoplasmic puncta seen in HSV-2 WT-infected (gD-positive) cells, the pattern of nuclear and cytoplasmic staining observed in infected cells was similar in cells that were negative for gD (Fig. 2A). Mock-infected cells, however, reacted poorly with the UL21 antiserum. The variability in staining seen in uninfected (i.e., gD-negative) versus mock-infected cells using our UL21 antiserum prompted us to investigate UL21 localization by other means. We constructed an HSV-2 strain containing a Flag epitope fused to the C terminus of UL21 and used an anti-Flag rabbit monoclonal antibody to determine the localization of UL21 in infected cells. At 6 hpi, UL21-Flag localized diffusely in the nucleus and cytoplasm as well as to cytoplasmic puncta, although these puncta appeared somewhat smaller than those observed in HSV-2 WT-infected cells at 6 hpi (Fig. 2B). In addition, UL21-Flag localized to the nuclear rim at 24 hpi (Fig. 2B). To determine the localization of UL21 in the absence of virus infection, the localization of a UL21-EGFP fusion protein was examined in transfected Vero cells. In transfected Vero cells, UL21-EGFP had a localization similar to that of UL21-Flag in infected cells: a pancellular distribution with concentrations of protein at the nuclear rim and in cytoplasmic puncta (Fig. 2C). Upon infection of UL21-EGFP-expressing cells with the HSV-2 WT strain, UL21-EGFP was observed in numerous cytoplasmic puncta as well as at the nuclear rim in a staining pattern similar to that observed for UL21-Flag-infected cells (Fig. 2D). We conclude that UL21 has both a nuclear and cytoplasmic localization and that this localization is independent of other viral factors; however, the abundance of cytoplasmic puncta positive for UL21 appeared to increase in virus-infected cells.

Fig 2.

Localization of HSV-2 UL21. (A) Monolayers of mock-infected cells (top) or Vero cells infected with HSV-2 WT at an MOI of 1.0 (bottom) were fixed at 6 hpi and stained with rat polyclonal antiserum against UL21. Infected cells were identified by using an anti-gD antibody. Arrows point to an infected, gD-positive cell. Arrowheads indicate the position of a gD-negative cell. (B) Vero cells were infected with HSV-2 UL21-Flag at an MOI of 0.1. At 6 hpi and 24 hpi, the cells were fixed and examined by confocal microscopy for localization of UL21 by using anti-Flag antibody. The arrowhead indicates cytoplasmic puncta, whereas the arrow indicates nuclear rim localization. (C) Vero cells were transfected with pUL21-GFP or pEGFP-CI. Images are representative of three independent experiments. The arrowhead indicates cytoplasmic puncta, whereas the arrow indicates nuclear rim localization. (D) Vero cells transfected with pUL21-GFP (top) or pEGFP-CI (bottom) were infected with HSV-2 WT at an MOI of 1.0. At 24 hpi, cells were fixed and stained for gD as described above. The arrowhead indicates cytoplasmic puncta, whereas the arrow indicates nuclear rim localization. Scale bars, 10 μm.

UL21 is essential for virus propagation.

Previous studies have shown that HSV-1 UL21 mutants exhibit slightly impaired replication in cell culture (11, 12, 38). To determine the requirements for HSV-2 UL21 during infection, we constructed an HSV-2 UL21 null mutant by deleting codons 2 to 531 of the 532-amino-acid UL21 open reading frame (ORF) (ΔUL21 BAC) (Fig. 3A). A repaired strain, ΔUL21R, was produced in Vero cells by homologous recombination between the ΔUL21 BAC and a PCR product containing the UL21 ORF and 5′ and 3′ flanking sequences. Transfection of the WT BAC into Vero cells resulted in plaque formation, as revealed by GFP fluorescence encoded by the BAC sequences, where GFP expression is under the control of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) major immediate early promoter (Fig. 3B). Transfection of the ΔUL21 BAC into Vero cells produced single GFP-positive cells that did not progress into plaques (Fig. 3B). Cotransfection of Vero cells with ΔUL21 BAC and the UL21 expression plasmid pUL21 produced small plaques of 15 to 20 infected cells (Fig. 3B). These findings suggest that the deletion of HSV-2 UL21 is lethal and can be partially complemented by expression of UL21 in cells initially transfected with the ΔUL21 BAC.

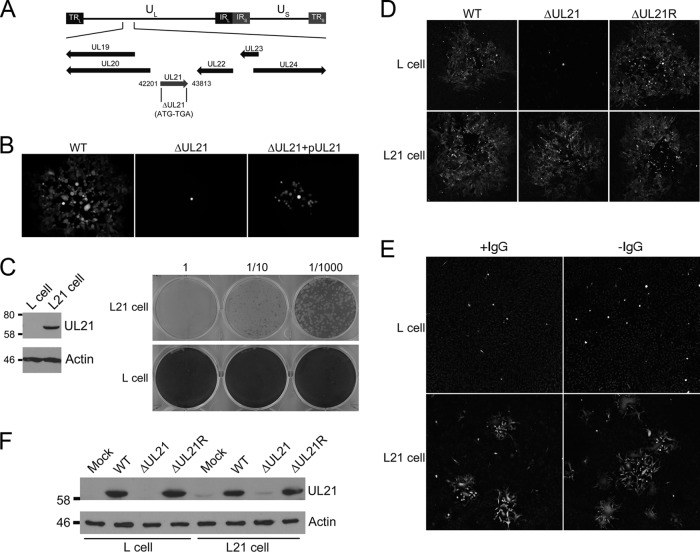

Fig 3.

Characterization of HSV-2 ΔUL21. (A) Schematic representation of the HSV-2 genome with unique long (UL), unique short (US), and inverted repeat (IR and TR) sequences. The region of the genome containing UL21 is enlarged, and the positions of the UL19, UL20, UL21, UL22, UL23, and UL24 genes are indicated by arrows. The genome coordinates comprising the deletion are provided on either side of the UL21 gene. (B) Vero cells were transfected with the indicated HSV-2 BAC in the absence or presence of the UL21 expression plasmid pUL21. Spread of infection was visualized at 72 h posttransfection by GFP expression encoded by BAC sequences. Representative images are shown. (C) L cells stably expressing UL21 (L21 cells) were constructed as described in Materials and Methods. (Left) Western blots of L and L21 cell lysates probed for UL21 and actin. (Right) Plaque assays of HSV-2 ΔUL21 on noncomplementing L and complementing L21 cells. Cells were fixed and stained with 0.5% methylene blue in 70% methanol at 3 days postinfection. (D) Plaque morphologies of HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, and ΔUL21R on L and L21 cells. Cells were infected with the indicated virus for 1 h at 37°C and incubated for 48 h in the presence of 0.05% pooled human IgG. Spread of infection was visualized at 48 hpi by using polyclonal antisera against Us3. Representative images are shown. Note that because these viruses lack BAC sequences, GFP fluorescence could not be used to evaluate the spread of these strains. (E) Plaque morphologies of ΔUL21 on L and L21 cells in the presence and absence of 0.05% pooled human IgG. Spread of infection was visualized at 24 hpi by using polyclonal antiserum against Us3. Representative images are shown. (F) L and L21 cells were infected at an MOI of 3.0 with HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, or ΔUL21R. At 36 hpi, total cell lysates were collected, electrophoresed through 10% polyacrylamide gels, and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Membranes were probed with the antisera indicated on the right. The migration positions of molecular mass markers in kDa are indicated on the left.

To propagate HSV-2 ΔUL21, we constructed a complementing cell line by transduction of the UL21 gene into murine L cells (L21 cells). Dilutions of HSV-2 ΔUL21 produced on L21 cells were plated onto L and L21 cells to assess the ability of the mutant virus to form plaques. HSV-2 ΔUL21 failed to form plaques on monolayers of the parental L cell line (Fig. 3C). In contrast, HSV-2 ΔUL21 was able to form plaques when plated onto L21 cells, indicating that L21 cells were able to complement HSV-2 ΔUL21 and restore its infectivity.

The plaque-forming ability of HSV-2 ΔUL21 was compared to those of HSV-2 WT and ΔUL21R by confocal microscopy. Noncomplementing (L) and complementing (L21) cell lines were infected with HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, or ΔUL21R in the presence of 0.5% pooled human IgG to prevent cell-free transmission of virus. At 48 hpi, the cells were fixed and stained with Us3 antiserum, which produces a strong and specific signal, to visualize plaque morphology. HSV-2 WT and ΔUL21R were able to form plaques efficiently on both tested cell lines (Fig. 3D). Productive replication of HSV-2 ΔUL21 was detected only when UL21 was provided in trans by the L21 cells, while only single infected L cells were observed (Fig. 3D). To investigate the possibility that 0.5% pooled human IgG interfered with the spread of ΔUL21 between cells, infections of L and L21 cells were compared in its presence and absence (Fig. 3E). Omission of 0.5% pooled human IgG from the culture medium resulted in only isolated single cells being infected and did not enhance the transmission of HSV-2 ΔUL21 between infected L cells, further suggesting that UL21 is essential for virus propagation.

To confirm that ΔUL21 did not produce UL21, UL21 expression was compared in infected L and L21 cells by Western blotting (Fig. 3F). In infected L cell lysates, the UL21 antiserum detected a band of approximately 62 kDa in HSV-2 WT- and ΔUL21R-infected cell lysates that was absent from mock- and ΔUL21-infected lysates (Fig. 3F). Parenthetically, the expression level of UL21 was low in mock-infected and ΔUL21-infected L21 cells compared to L and L21 cells infected with HSV-2 WT and ΔUL21R (Fig. 3F).

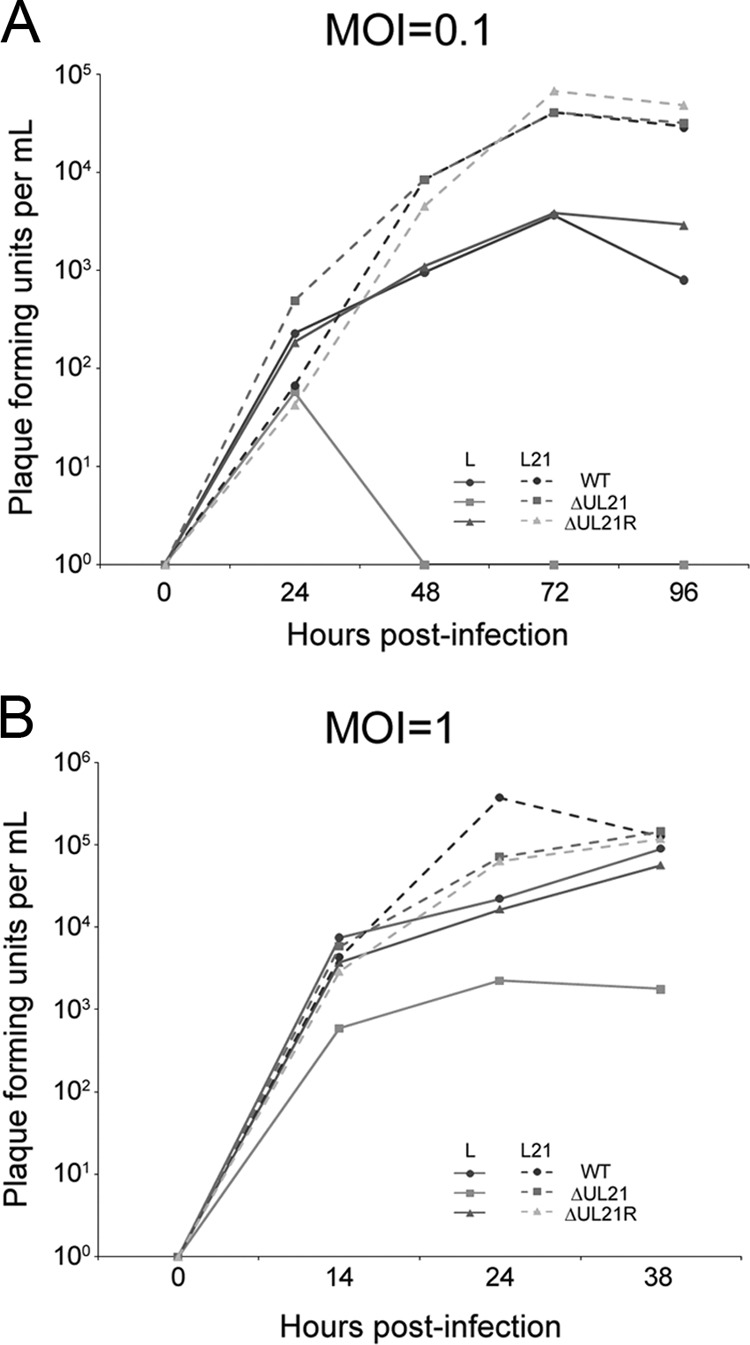

To analyze the replication of HSV-2 ΔUL21 in greater detail, virus production was measured over time after infection of L and L21 cells by titrating progeny virus on L21 cell monolayers. By necessity, the inocula for these experiments were produced on complementing L21 cells. At an MOI of 0.1, infection of noncomplementing L cells with HSV-2 ΔUL21 resulted in no detectable infectious virus beyond 48 hpi, while propagation of the mutant on complementing L21 cells resulted in titers of infectious progeny comparable to those of HSV-2 WT (Fig. 4A). At an MOI of 1.0, HSV-2 ΔUL21 produced a considerable amount of virus from L cells, with total virus yields being roughly 50-fold lower than those of HSV-2 WT and ΔUL21R (Fig. 4B). Notably, ΔUL21 produced from L or L21 cells could be titrated only on complementing L21 cells. These data indicate that the deficiency in HSV-2 ΔUL21 propagation can be partially overcome by increasing the MOI. Regardless of the cell line or MOI, HSV-2 ΔUL21R replicated with the same kinetics as HSV-2 WT (Fig. 4). Collectively, the data shown in Fig. 3 and 4 demonstrate that UL21 is essential for HSV-2 replication.

Fig 4.

Replication kinetics of HSV-2 ΔUL21. L and L21 cells were infected with HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, and ΔUL21R at an MOI of 0.1 (A) or an MOI of 1.0 (B). At the indicated times postinfection, cells and culture medium were harvested together, and virus was titrated on L21 cells. Results are the averages of duplicate experiments.

HSV-2 ΔUL21 exhibits a delay in virus gene expression.

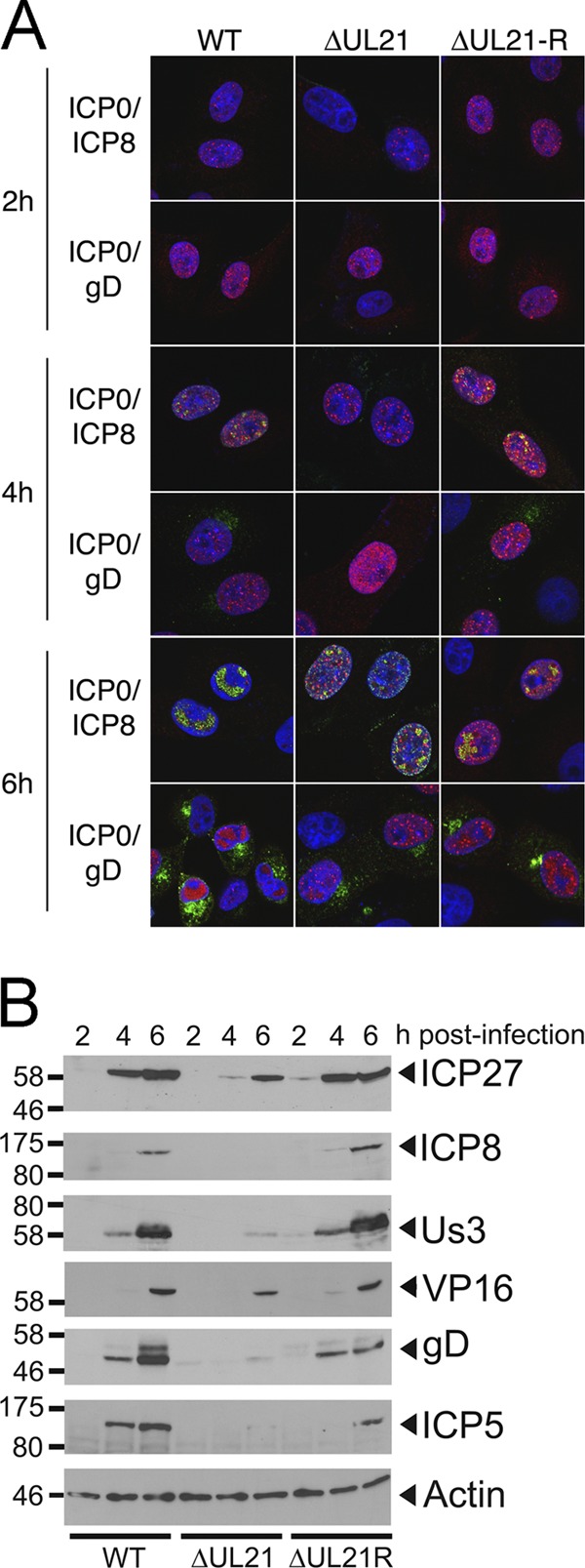

To investigate the block in virus replication caused by the deletion of UL21, we compared the kinetics of viral gene expression in noncomplementing Vero cells infected with HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, and ΔUL21R by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5A). Expression of ICP0 (Fig. 5A, red) alongside ICP8 (green) and ICP0 alongside gD (green) was examined by confocal microscopy at 2, 4, and 6 hpi. The IE gene product ICP0 was present in nuclear puncta at 2 hpi in HSV-2 WT and ΔUL21R, while a similar staining pattern in HSV-2 ΔUL21 was not observed until 4 hpi. At 6 hpi, in HSV-2 WT- and ΔUL21R-infected cells, the E gene product ICP8 localized to coalesced replication compartments (39), while HSV-2 ΔUL21 displayed punctate ICP8 nuclear staining, reminiscent of ICP8 localization at 4 hpi in HSV-2 WT- and ΔUL21R-infected cells. A 2-h delay in the appearance of the L gene product gD in the Golgi apparatus was seen with HSV-2 ΔUL21 (6 hpi) compared to HSV-2 WT and ΔUL21R (4 hpi). To quantify these data, cells in 10 randomly selected fields (n = 300 to 400 cells/condition) were evaluated under each experimental condition. Cells were scored positive for virus antigen when an appropriately localized signal was detected over background. At 4 hpi, 63.6% and 51.9% of HSV-2 WT- and ΔUL21R-infected cells were both ICP0 and ICP8 positive, respectively, whereas only 7.4% of ΔUL21-infected cells were stained with both IE and E antigens. The percentage of infected cells positive for both ICP0 and ICP8 rose to 100% for HSV-2 WT and ΔUL21R and 87.8% for ΔUL21 at 6 hpi. From 4 to 6 hpi, the percentages of infected cells positive for ICP0 and gD increased from 63.6% to 100% for HSV-2 WT, 0% to 45.9% for ΔUL21, and 64.8% to 75% for ΔUL21R.

Fig 5.

HSV-2 ΔUL21 displays a delay in virus protein expression. (A) Vero cells were infected with HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, or ΔUL21R at an MOI of 0.1. At the indicated times postinfection, cells were fixed and analyzed for ICP0/ICP8 (IE/E) and ICP0/gD (IE/L). Cells were stained with rat polyclonal antiserum specific for ICP0 and mouse monoclonal antibodies against ICP8 or gD, followed by staining with Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (red signal) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (green signal). Nuclei were visualized with Hoechst 33342 (blue signal). Images were captured by using confocal microscopy. Representative images are shown. Scale bars, 10 μm. (B) Vero cells were infected with HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, or ΔUL21R at an MOI of 1.0. At the indicated times postinfection, cells lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting against representative proteins from three kinetic classes: IE (ICP27), E (ICP8 and Us3), and L (VP16, ICP5, and gD). Molecular mass markers in kDa are shown on the left.

In a complementary approach, Western blot analysis was performed to determine the expression of representative IE (ICP27), E (ICP8 and Us3), and L (VP16, ICP5, and gD) gene products over time (Fig. 5B). ICP27 (IE) expression in HSV-2 ΔUL21-infected Vero cell lysates was first detected by 4 hpi, while in HSV-2 WT- and ΔUL21R-infected samples, ICP27 appeared by 2 hpi. In HSV-2 WT- and ΔUL21R-infected samples, ICP8 (E) and Us3 (E) were detected by 4 hpi, compared to 6 hpi in HSV-2 ΔUL21-infected cell lysates. Finally, VP16 (L), ICP5 (L), and gD (L) appeared by 4 hpi in HSV-2 WT- and ΔUL21R-infected cell lysates, whereas in HSV-2 ΔUL21-infected cell lysates, these proteins were weakly detected at 6 hpi.

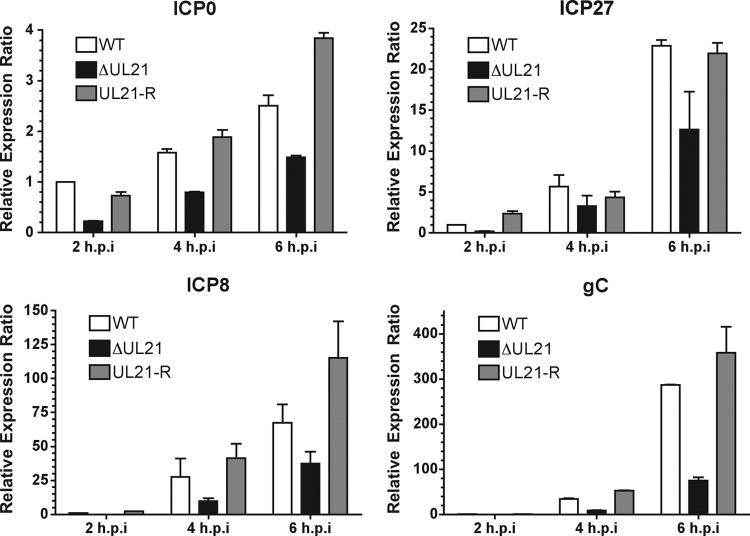

A recent study demonstrated that HSV-1 UL21 facilitates viral protein production at the level of mRNA synthesis (12). To determine whether the observed delay in protein production in HSV-2 ΔUL21 was due to a lag in mRNA synthesis, we performed quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). Vero cells were infected at an MOI of 0.1 with HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, or ΔUL21R for 2, 4, and 6 h, and total RNA was extracted and used for the synthesis of cDNA. PCR amplification with specific primers for representative IE (ICP0 and ICP27), E (ICP8), and L (gC) genes produced bands of the expected sizes, and their identities were confirmed by DNA sequencing (data not shown). The qRT-PCR data shown in Fig. 6 revealed that mRNA levels of all genes tested were reduced between 4- and 50-fold in cells infected with HSV-2 ΔUL21 compared to WT- and ΔUL21R-infected cells. These findings were consistent with results reported previously by Mbong and colleagues (12).

Fig 6.

HSV-2 ΔUL21 displays a delay in virus gene expression The levels of ICP0, ICP27, ICP8, and gC mRNAs were analyzed in HSV-2 WT-, ΔUL21-, or ΔUL21R-infected cells at 2, 4, and 6 hpi. Vero cells were mock infected or infected at an MOI of 0.1, and total mRNA was extracted from cells at the indicated times postinfection. After reverse transcription, the relative abundances of ICP0, ICP27, ICP8, and gC mRNAs were quantified by qRT-PCR using 18S rRNA as an internal control to normalize the template input. Values were normalized to the value for HSV-2 WT-infected cells at 2 hpi, which was arbitrarily set to 1.0. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard errors between duplicate wells.

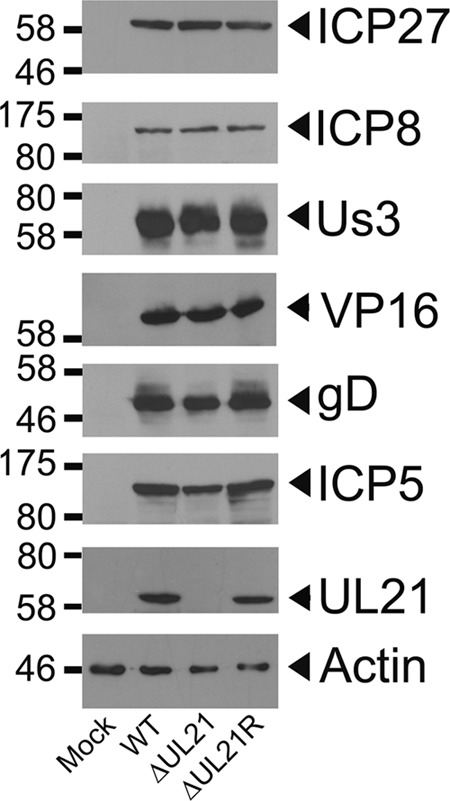

HSV-2 ΔUL21 accumulates gene products at later times postinfection.

To discern whether the reduction in the levels of viral mRNA seen early during infection impacted protein synthesis at later times postinfection, we compared the expression levels of representative IE (ICP27), E (ICP8 and Us3), and L (VP16, gD, and ICP5) gene products in HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, and ΔUL21R at 24 hpi in noncomplementing Vero cells. The data presented in Fig. 7 illustrate that the delay in viral protein expression that occurred early in HSV-2 ΔUL21-infected cells was abrogated by 24 hpi, as all proteins examined accumulated to similar levels, with the notable exception of UL21. These findings suggest that the delay in virus gene expression observed for HSV-2 ΔUL21 is not responsible for failure of this strain to propagate on noncomplementing cells.

Fig 7.

Expression of HSV-2 ΔUL21 gene products late in infection. Western blot analysis of representative IE (ICP27), E (ICP8 and Us3), and L (UL21, VP16, gD, and ICP5) gene products was performed at 24 hpi. Cell lysates from Vero cells infected with HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, or ΔUL21R at an MOI of 3.0 were electrophoresed through 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Antisera are indicated on the right, and molecular mass markers in kDa are shown on the left.

UL21 is required for nuclear egress of capsids.

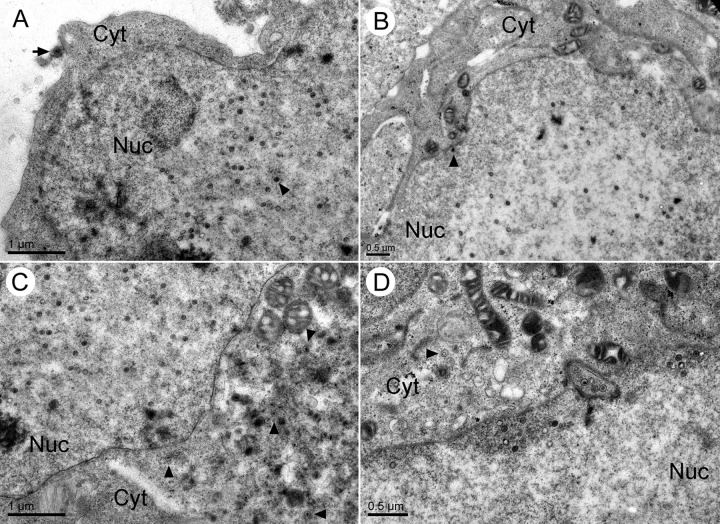

Given that the defect in virus gene expression was merely a delay and not a complete block, it was of interest to determine if loss of UL21 impacted virion assembly. Vero cells were infected with HSV-2 ΔUL21 and HSV-2 ΔUL21R at an MOI of 3.0. At 14 hpi, the cells were fixed, and thin sections were examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 8). In HSV-2 ΔUL21R-infected cells, enveloped virions and nonenveloped capsids were readily seen in the cytoplasm, and extracellular virions were evident (Fig. 8A and C). While empty and DNA-containing C capsids were obvious in the nuclei of ΔUL21-infected cells, cytoplasmic capsids were rarely seen (Fig. 8B and D). Importantly, there was no evidence of accumulation of perinuclear enveloped virions, such as those seen with alphaherpesviruses lacking Us3 (40), suggesting that UL21 is required for primary envelopment of capsids rather than deenvelopment of perinuclear virions.

Fig 8.

HSV-2 ΔUL21 has a defect in nuclear egress. Electron micrographs of Vero cells infected at an MOI of 3.0 with HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, or ΔUL21R were fixed at 14 hpi, thin sectioned, and processed for TEM. (A) Section through a ΔUL21R-infected nucleus reveals numerous nucleocapsids containing viral DNA (arrowhead) and an extracellular virion (arrow). (B) Section through a ΔUL21-infected nucleus reveals numerous nucleocapsids containing viral DNA (arrowhead). (C) Section through the cytoplasm of a ΔUL21R-infected cell reveals numerous capsids (arrowheads). (D) Section through the cytoplasm of a ΔUL21-infected cell reveals a paucity of cytoplasmic capsids. A rare empty capsid (arrowhead) is visible.

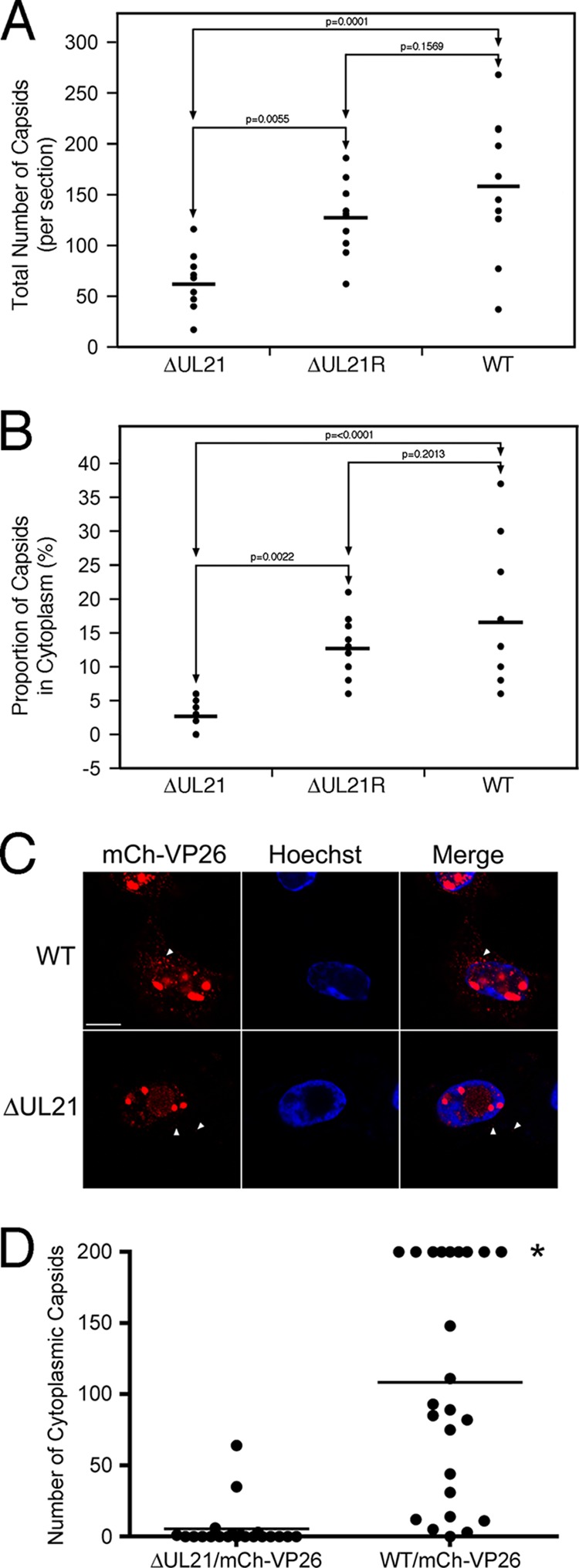

To quantify the effects of UL21 deletion on nuclear egress, the numbers of total capsids as well as the numbers of cytoplasmic capsids were counted in 10 independent sections of Vero cells infected with HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, or ΔUL21R (Fig. 9A and B). While 2- to 3-fold-fewer capsids were seen in Vero cells infected with ΔUL21 than in cells infected with the WT or ΔUL21R strain, the percentage of the total number of capsids found in the cytoplasm of ΔUL21-infected Vero cells was significantly reduced in comparison to cells infected with the WT or ΔUL21R strain, further supporting a role for UL21 in egress of nuclear capsids.

Fig 9.

Quantification of HSV-2 ΔUL21 nuclear egress. (A) Total numbers of capsids were counted in 10 sections of Vero cells infected with HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, or ΔUL21R by transmission electron microscopy. Horizontal lines indicate mean values for each specimen analyzed. One-way ANOVA of the data revealed significant differences in total capsid numbers between WT and ΔUL21 (P = 0.0001) and ΔUL21R and ΔUL21 (P = 0.0055) viruses. The differences between the numbers of capsids seen in WT- compared to ΔUL21R-infected cells were not significant (P = 0.1569). (B) The percentage of capsids localized to the cytoplasm was evaluated in 10 sections of Vero cells infected with HSV-2 WT, ΔUL21, or ΔUL21R by transmission electron microscopy. Horizontal lines indicate mean values for each specimen analyzed. One-way ANOVA of the data revealed significant differences in the percentages of cytoplasmic capsid between WT and ΔUL21 (P < 0.0001) and ΔUL21R and ΔUL21 (P = 0.0022) viruses. The differences between the numbers of cytoplasmic capsids seen in WT- compared to ΔUL21R-infected cells were not significant (P = 0.2013). (C) Vero cells infected with the WT/mCh-VP26 (top row) or ΔUL21/mCh-VP26 (bottom row) virus were fixed and stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue) at 18 hpi. A series of z images taken from the bottom to the top of the cell were acquired by confocal microscopy using a step size of 0.4 μm. Projection images of representative z stacks are shown. Arrowheads indicate cytoplasmic capsids (red). Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) The numbers of cytoplasmic capsids were counted in entire ΔUL21/mCh-VP26- and WT/mCh-VP26-infected cells. Each data point represents a single cell. The horizontal bar represents the mean number of cytoplasmic capsids found in 21 to 24 infected cells. The asterisk indicates WT/mCh-VP26-infected cells containing more than 200 cytoplasmic capsids.

To corroborate the transmission electron microscopy findings, we constructed WT and ΔUL21 mutant viruses with mCherry fused to the N terminus of the capsid protein VP26 (mCh-VP26). At 18 hpi, fluorescent capsids were readily detected in the cytoplasm of WT/mCh-VP26-infected cells (Fig. 9C). In contrast, the fluorescence of HSV-2 ΔUL21/mCh-VP26 was observed to be predominantly nuclear, with few capsids visible in the cytoplasm. Times beyond 18 hpi resulted in severe disruptions in cellular morphology in ΔUL21/mCh-VP26-infected cells and prohibited analysis. To quantify these observations, WT/mCh-VP26 (n = 21)- and ΔUL21/mCh-VP26 (n = 24)-infected cells were imaged in three dimensions at 18 hpi, and the numbers of cytoplasmic capsids per cell were counted (Fig. 9D). While the majority of WT/mCh-VP26-infected cells had in excess of 100 cytoplasmic capsids per cell, 67% of ΔUL21/mCh-VP26-infected cells had no detectable cytoplasmic capsids. The majority of ΔUL21/mCh-VP26-infected cells with detectable capsids (20%) had 3 or fewer per cell, raising the possibility that these capsids represented remaining input capsids from the inoculum. Taken together, these findings suggest a critical role for UL21 in the nuclear egress of HSV-2 capsids.

DISCUSSION

The HSV-2 ΔUL21 mutant described here was able to replicate only when UL21 was provided in trans. Moreover, the restoration of virus growth upon repair of the UL21 deletion confirmed that loss of UL21 expression was responsible for the lethal phenotype. Together, these data provide strong evidence that the HSV-2 UL21 ortholog is essential for virus propagation. These findings are in contrast to observations with HSV-1 and PRV, where UL21 was dispensable for virus replication in cultured cells (11–13, 16, 38). HSV-2 UL21 shares 84% amino acid identity with its HSV-1 ortholog, which is a higher degree of conservation than that maintained by two nonessential tegument proteins, Us3 and Us2, which have 75% and 76% identity, respectively. In comparison, conservation of the essential tegument proteins VP16 and VP1/2 is 86% and 83%, respectively. These observations may suggest that there is greater selective pressure to conserve UL21 features than those of nonessential tegument proteins.

HSV-2 ΔUL21 replication occurred on noncomplementing L cells, at a level approximately 2% of WT virus replication, if an MOI of 1.0 was used (Fig. 4). Because the inoculum used in these experiments was produced, by necessity, using complementing L21 cells, it is possible that tegument-associated UL21, acquired by the inoculum during its production in L21 cells, partially complemented the ΔUL21 replication defect in L cells. It is also possible that the ΔUL21 virions released from L21 cells contain additional, non-UL21, complementing components lacking in virions released from L cells. The observation that a reproducible, albeit miniscule, production of virus was detected from L cells at 24 h after infection at an MOI of 0.1, but not at later times, supports the view that the ΔUL21 virion composition is different when the virus is produced in L cells versus L21 cells. We suggest that the virus released from L cells after the first round of replication reinfected other cells to begin a second round of infection in L cells and that this second round of infection was nonproductive because the second-round inoculum was produced in L, rather than L21, cells. Alternatively, it may simply be that when a higher inoculum is used to infect noncomplementing L cells, more tegument components are delivered to the infected cell that, together, partially overcome the UL21 deficiency. Regardless, the inability of HSV-2 ΔUL21 to be propagated in the absence of UL21 defines UL21 as an essential gene product for HSV-2.

Interestingly, at an MOI of 0.1, total virus yields of HSV-2 WT and ΔUL21R were consistently increased by approximately 15-fold in L21 cells compared to virus yields in noncomplementing L cells, suggesting that ectopic expression of UL21 stimulates virus production after low-multiplicity infection (Fig. 4). The levels of UL21 produced in L21 cells were far lower than those observed in cells infected with HSV-2 WT or ΔUL21R (Fig. 3F), implying either that UL21 is produced in great excess during WT virus infection or that the constitutive, and therefore inappropriately timed, expression of UL21 in L21 cells circumvents the requirement for increased levels of UL21. Moreover, the relative paucity of UL21 present in L21 cells which is nonetheless capable of complementing the ΔUL21 virus may indicate a catalytic role for UL21 in HSV-2 production rather than a structural role.

We determined that HSV-2 ΔUL21 has defects in two aspects of the virus replicative cycle, one early and the other at a late stage of virus infection. Similar to what was recently documented for an HSV-1 UL21 mutant (12), we found that HSV-2 UL21 mutants had a delay in the initiation of virus gene expression and that this occurred at the level of transcription. One study demonstrated that HSV-1 UL21 binds to microtubules, prompting speculation that it may function in the transport of capsids along microtubules during entry or egress (18). It may be that the absence of UL21 delays the transport of incoming capsids to the nucleus, contributing to the delay in the expression of IE gene products. Alternatively, indirect deficiencies in virion composition, secondary to the UL21 deletion, might adversely impact the kinetics with which infecting ΔUL21 virions initiate virus gene expression.

The defects in the kinetics of virus gene expression observed with the HSV-2 ΔUL21 strain could not explain its replication defect, because WT levels of representative virus gene products were observed to accumulate late in infection (Fig. 7). Analysis of infected cells by transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 8) and quantitative measurements of cytoplasmic capsid localization (Fig. 9) indicated reduced overall numbers of capsids in the nuclei of ΔUL21-infected cells as well as a failure of nuclear capsids to acquire a primary envelope from the inner nuclear membrane (INM) and to exit the nucleus. It may be that the loss of UL21 affects capsid stability and/or that the delay in virus gene expression impacts the rate at which capsids assemble in the nuclei of ΔUL21-infected cells. Either of these scenarios could result in the reduction in steady-state levels of nuclear capsids observed and may also contribute to the reduced replication of the ΔUL21 strain. Nevertheless, the proportion of capsids trafficking from the nucleus to the cytoplasm was significantly reduced in ΔUL21-infected cells and suggests a defect in primary envelopment of capsids. The process of primary envelopment is largely conserved between diverse herpesviruses and is a subject of considerable interest (reviewed in reference 41). Essential components of the nuclear egress complex (NEC), the orthologs of the HSV proteins UL31 and UL34, localize predominantly to the INM in virus-infected cells (36, 42). These proteins are conserved throughout the Herpesviridae, whereas the alphaherpesvirus-specific serine/threonine kinase, Us3, which phosphorylates UL31 and UL34 as well as nuclear lamins A and C along with the conserved virus-encoded kinase, UL13, and cellular kinases, modulates the process of primary envelopment in part by promoting focal solubilization of the nuclear lamina at sites of nuclear egress (43–49). DNA-containing C capsids were evident in the nucleoplasm of ΔUL21-infected cells (Fig. 8); however, there was no evidence of the congregation of ΔUL21 capsids at the INM or the accumulation of primary enveloped virions within the perinuclear space. These findings suggest that DNA-containing ΔUL21 capsids are defective at a stage prior to their recruitment to the NEC at the INM. Recruitment of C capsids to the INM is mediated by the C-capsid-specific complex comprised of UL17 and UL25, which recruits UL31 to the capsid surface (50–52). Interactions between capsid-associated UL31 and UL34 in the INM could then bridge the capsid to the NEC. As UL21 has been reported to be an inner tegument protein tightly associated with the capsid (18, 53), it may be that in HSV-2, UL21 participates in the formation of the C-capsid-specific complex or is involved in the recruitment of UL31 to capsids. The observation that UL21 itself has the capacity to localize to the nuclear rim (Fig. 2B and C) evokes the hypothesis that UL21 functions as part of the NEC to recruit capsids to the INM or, alternatively, promotes disruption of the nuclear lamina.

UL21 can be isolated as part of a complex containing at least two additional viral tegument proteins, UL11 and UL16 (15, 19–26). One role of this complex is to regulate the localization, trafficking, and activities of the viral glycoprotein gE through interactions with the gE cytoplasmic tail (27). It is not immediately obvious how a gE/UL11/UL16/UL21 complex might be involved in the nuclear egress of capsids. Aberrant trafficking of viral membrane proteins to, or from, the INM could potentially interfere with this process. Whether the essential activities of HSV-2 UL21 occur in complex with UL16 and UL11 is unclear at this time. The finding that UL16 and UL11 are conserved between all subfamilies of the Herpesviridae, whereas UL21 is specific to the Alphaherpesvirinae, suggests that UL21 activities that are independent of the UL11/UL16/UL21 complex likely exist. Further analyses of HSV-2 ΔUL21 entry, nucleocapsid composition, and the function of its NEC should provide new insight into the unique requirements for HSV-2 UL21 in early and late stages of the virus replication cycle.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research operating grant 93804, Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada discovery grant 418719, Canada Foundation for Innovation award 16389, and an award from the Violet E. Powell Research Fund to B.W.B. Y.K. was supported by the Funding Program for Next Generation World-Leading Researchers from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and a contract research fund for the Program of Japan Initiative for Global Research Network on Infectious Diseases from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, Sports and Technology (MEXT) of Japan. This work made use of the Cornell Center for Materials Research Facilities, supported by the National Science Foundation under award number DMR-1120296.

We thank Craig McCormick, Dalhousie University, for help and advice with amphotropic retrovirus production; Hervé Le Moual, McGill University, and Klaus Osterrieder, Freie Universität Berlin, for plasmids; Greg Smith, Northwestern University, for bacterial strain GS1783; and David Knipe, Harvard University, for HSV-2 strain 186. We thank members of the Gee and Poole laboratories, Queen's University, for help with qRT-PCR and members of the Banfield laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 March 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Stanberry L, Cunningham A, Mertz G, Mindel A, Peters B, Reitano M, Sacks S, Wald A, Wassilew S, Woolley P. 1999. New developments in the epidemiology, natural history and management of genital herpes. Antiviral Res. 42:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barnabas RV, Wasserheit JN, Huang Y, Janes H, Morrow R, Fuchs J, Mark KE, Casapia M, Mehrotra DV, Buchbinder SP, Corey L, NIAID HIV Vaccine Trials Network 2011. Impact of herpes simplex virus type 2 on HIV-1 acquisition and progression in an HIV vaccine trial (the Step study). J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 57:238–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ward H, Ronn M. 2010. Contribution of sexually transmitted infections to the sexual transmission of HIV. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 5:305–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dolan A, Jamieson FE, Cunningham C, Barnett BC, McGeoch DJ. 1998. The genome sequence of herpes simplex virus type 2. J. Virol. 72:2010–2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McGeoch DJ, Cook S, Dolan A, Jamieson FE, Telford EA. 1995. Molecular phylogeny and evolutionary timescale for the family of mammalian herpesviruses. J. Mol. Biol. 247:443–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Corey L, Whitley RJ, Stone EF, Mohan K. 1988. Difference between herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 neonatal encephalitis in neurological outcome. Lancet i:1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dyer AP, Banfield BW, Martindale D, Spannier DM, Tufaro F. 1997. Dextran sulfate can act as an artificial receptor to mediate a type-specific herpes simplex virus infection via glycoprotein B. J. Virol. 71:191–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Langenberg AG, Corey L, Ashley RL, Leong WP, Straus SE. 1999. A prospective study of new infections with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2. Chiron HSV Vaccine Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:1432–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Loret S, Guay G, Lippe R. 2008. Comprehensive characterization of extracellular herpes simplex virus type 1 virions. J. Virol. 82:8605–8618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kramer T, Greco TM, Enquist LW, Cristea IM. 2011. Proteomic characterization of pseudorabies virus extracellular virions. J. Virol. 85:6427–6441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baines JD, Koyama AH, Huang T, Roizman B. 1994. The UL21 gene products of herpes simplex virus 1 are dispensable for growth in cultured cells. J. Virol. 68:2929–2936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mbong EF, Woodley L, Frost E, Baines JD, Duffy C. 2012. Deletion of UL21 causes a delay in the early stages of the herpes simplex virus 1 replication cycle. J. Virol. 86:7003–7007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Wind N, Wagenaar F, Pol J, Kimman T, Berns A. 1992. The pseudorabies virus homolog of the herpes simplex virus UL21 gene product is a capsid protein which is involved in capsid maturation. J. Virol. 66:7096–7103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wagenaar F, Pol JM, de Wind N, Kimman TG. 2001. Deletion of the UL21 gene in pseudorabies virus results in the formation of DNA-deprived capsids: an electron microscopy study. Vet. Res. 32:47–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Klupp BG, Bottcher S, Granzow H, Kopp M, Mettenleiter TC. 2005. Complex formation between the UL16 and UL21 tegument proteins of pseudorabies virus. J. Virol. 79:1510–1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Klupp BG, Lomniczi B, Visser N, Fuchs W, Mettenleiter TC. 1995. Mutations affecting the UL21 gene contribute to avirulence of pseudorabies virus vaccine strain Bartha. Virology 212:466–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Klopfleisch R, Klupp BG, Fuchs W, Kopp M, Teifke JP, Mettenleiter TC. 2006. Influence of pseudorabies virus proteins on neuroinvasion and neurovirulence in mice. J. Virol. 80:5571–5576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Takakuwa H, Goshima F, Koshizuka T, Murata T, Daikoku T, Nishiyama Y. 2001. Herpes simplex virus encodes a virion-associated protein which promotes long cellular processes in over-expressing cells. Genes Cells 6:955–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baines JD, Jacob RJ, Simmerman L, Roizman B. 1995. The herpes simplex virus 1 UL11 proteins are associated with cytoplasmic and nuclear membranes and with nuclear bodies of infected cells. J. Virol. 69:825–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harper AL, Meckes DG, Jr, Marsh JA, Ward MD, Yeh PC, Baird NL, Wilson CB, Semmes OJ, Wills JW. 2010. Interaction domains of the UL16 and UL21 tegument proteins of herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 84:2963–2971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Loomis JS, Bowzard JB, Courtney RJ, Wills JW. 2001. Intracellular trafficking of the UL11 tegument protein of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:12209–12219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Loomis JS, Courtney RJ, Wills JW. 2003. Binding partners for the UL11 tegument protein of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 77:11417–11424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meckes DG, Jr, Wills JW. 2007. Dynamic interactions of the UL16 tegument protein with the capsid of herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 81:13028–13036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nalwanga D, Rempel S, Roizman B, Baines JD. 1996. The UL 16 gene product of herpes simplex virus 1 is a virion protein that colocalizes with intranuclear capsid proteins. Virology 226:236–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oshima S, Daikoku T, Shibata S, Yamada H, Goshima F, Nishiyama Y. 1998. Characterization of the UL16 gene product of herpes simplex virus type 2. Arch. Virol. 143:863–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schimmer C, Neubauer A. 2003. The equine herpesvirus 1 UL11 gene product localizes to the trans-Golgi network and is involved in cell-to-cell spread. Virology 308:23–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Han J, Chadha P, Starkey JL, Wills JW. 2012. Function of glycoprotein E of herpes simplex virus requires coordinated assembly of three tegument proteins on its cytoplasmic tail. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:19798–19803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yeh PC, Meckes DG, Jr, Wills JW. 2008. Analysis of the interaction between the UL11 and UL16 tegument proteins of herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 82:10693–10700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baines JD, Roizman B. 1992. The UL11 gene of herpes simplex virus 1 encodes a function that facilitates nucleocapsid envelopment and egress from cells. J. Virol. 66:5168–5174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meckes DG, Jr, Marsh JA, Wills JW. 2010. Complex mechanisms for the packaging of the UL16 tegument protein into herpes simplex virus. Virology 398:208–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Swift S, Lorens J, Achacoso P, Nolan GP. 2001. Rapid production of retroviruses for efficient gene delivery to mammalian cells using 293T cell-based systems. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Chapter 10:Unit 10.17C. doi:10.1002/0471142735.im1017cs31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Finnen RL, Roy BB, Zhang H, Banfield BW. 2010. Analysis of filamentous process induction and nuclear localization properties of the HSV-2 serine/threonine kinase Us3. Virology 397:23–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morimoto T, Arii J, Tanaka M, Sata T, Akashi H, Yamada M, Nishiyama Y, Uema M, Kawaguchi Y. 2009. Differences in the regulatory and functional effects of the Us3 protein kinase activities of herpes simplex virus 1 and 2. J. Virol. 83:11624–11634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tischer BK, Smith GA, Osterrieder N. 2010. En passant mutagenesis: a two step markerless red recombination system. Methods Mol. Biol. 634:421–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. O'Gorman S, Fox DT, Wahl GM. 1991. Recombinase-mediated gene activation and site-specific integration in mammalian cells. Science 251:1351–1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Reynolds AE, Wills EG, Roller RJ, Ryckman BJ, Baines JD. 2002. Ultrastructural localization of the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL31, UL34, and US3 proteins suggests specific roles in primary envelopment and egress of nucleocapsids. J. Virol. 76:8939–8952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roizman B, Knipe DM. 2001. Herpes simplex viruses and their replication, p 2399–2459 In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE. (ed), Fields virology, 4th ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 38. Muto Y, Goshima F, Ushijima Y, Kimura H, Nishiyama Y. 2012. Generation and characterization of UL21-null herpes simplex virus type 1. Front. Microbiol. 3:394 doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Quinlan MP, Chen LB, Knipe DM. 1984. The intranuclear location of a herpes simplex virus DNA-binding protein is determined by the status of viral DNA replication. Cell 36:857–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wagenaar F, Pol JM, Peeters B, Gielkens AL, de Wind N, Kimman TG. 1995. The US3-encoded protein kinase from pseudorabies virus affects egress of virions from the nucleus. J. Gen. Virol. 76(Part 7):1851–1859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Johnson DC, Baines JD. 2011. Herpesviruses remodel host membranes for virus egress. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9:382–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Reynolds AE, Ryckman BJ, Baines JD, Zhou Y, Liang L, Roller RJ. 2001. U(L)31 and U(L)34 proteins of herpes simplex virus type 1 form a complex that accumulates at the nuclear rim and is required for envelopment of nucleocapsids. J. Virol. 75:8803–8817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cano-Monreal GL, Wylie KM, Cao F, Tavis JE, Morrison LA. 2009. Herpes simplex virus 2 UL13 protein kinase disrupts nuclear lamins. Virology 392:137–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Leach NR, Roller RJ. 2010. Significance of host cell kinases in herpes simplex virus type 1 egress and lamin-associated protein disassembly from the nuclear lamina. Virology 406:127–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mou F, Forest T, Baines JD. 2007. US3 of herpes simplex virus type 1 encodes a promiscuous protein kinase that phosphorylates and alters localization of lamin A/C in infected cells. J. Virol. 81:6459–6470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mou F, Wills E, Baines JD. 2009. Phosphorylation of the U(L)31 protein of herpes simplex virus 1 by the U(S)3-encoded kinase regulates localization of the nuclear envelopment complex and egress of nucleocapsids. J. Virol. 83:5181–5191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Muranyi W, Haas J, Wagner M, Krohne G, Koszinowski UH. 2002. Cytomegalovirus recruitment of cellular kinases to dissolve the nuclear lamina. Science 297:854–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Park R, Baines JD. 2006. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection induces activation and recruitment of protein kinase C to the nuclear membrane and increased phosphorylation of lamin B. J. Virol. 80:494–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Purves FC, Spector D, Roizman B. 1991. The herpes simplex virus 1 protein kinase encoded by the US3 gene mediates posttranslational modification of the phosphoprotein encoded by the UL34 gene. J. Virol. 65:5757–5764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Leelawong M, Guo D, Smith GA. 2011. A physical link between the pseudorabies virus capsid and the nuclear egress complex. J. Virol. 85:11675–11684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Trus BL, Newcomb WW, Cheng N, Cardone G, Marekov L, Homa FL, Brown JC, Steven AC. 2007. Allosteric signaling and a nuclear exit strategy: binding of UL25/UL17 heterodimers to DNA-filled HSV-1 capsids. Mol. Cell 26:479–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang K, Baines JD. 2011. Selection of HSV capsids for envelopment involves interaction between capsid surface components pUL31, pUL17, and pUL25. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:14276–14281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Radtke K, Kieneke D, Wolfstein A, Michael K, Steffen W, Scholz T, Karger A, Sodeik B. 2010. Plus- and minus-end directed microtubule motors bind simultaneously to herpes simplex virus capsids using different inner tegument structures. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000991 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]