Abstract

Influenza A virus uses sialic acids as cell entry receptors, and there are two main receptor forms, α2,6 linkage or α2,3 linkage to galactose, that determine virus host ranges (mammalian or avian). The receptor binding hemagglutinins (HAs) of both 1918 and 2009 pandemic H1N1 (18H1 and 09H1, respectively) influenza A viruses preferentially bind to the human α2,6 linkage receptor. A single D225G mutation in both H1s switches receptor binding specificity from α2,6 linkage binding to dual receptor binding. However, the molecular basis for this specificity switch is not fully understood. Here, we show via H1-ligand complex structures that the D225G substitution results in a loss of a salt bridge between amino acids D225 and K222, enabling the key residue Q226 to interact with the avian receptor, thereby obtaining dual receptor binding. This is further confirmed by a D225E mutant that retains human receptor binding specificity with the salt bridge intact.

INTRODUCTION

There were three recorded influenza pandemics (1) before 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza (pH1N1) appeared (2). The 2009 pH1N1 virus is named the swine-origin influenza A virus (S-OIV) due to the major origins of its gene segments in terms of the host species (i.e., from pigs) (3–6). In fact, interspecies transmission is a characteristic of influenza A viruses, and all of the pandemic viruses display some evidence of an animal origin (7). Therefore, elucidation of the molecular mechanism by which interspecies influenza A virus transmission occurs is crucial for the prevention and control of infection and pandemics.

Influenza viruses are negative-strand segmented RNA viruses classified in the family Orthomyxoviridae, which includes the three types of influenza virus: A, B, and C. Among these three viruses, influenza A viruses are the major cause of the seasonal flu and occasional pandemics. There are eight gene segments in the influenza A virus genome that encode 13 proteins (8–10), namely, hemagglutinin (HA), NA, NP, NS1, NS2, M1, M2, PA, PB1, PB2, PB1-F2, PB1-N40, and PA-X.

HA is the major influenza A virus surface envelope protein, with 16 known serotypes, and it is responsible for host range, receptor binding, and virus fusion/entry (11). A newly identified bat-derived H17 has an as-yet-undefined function (12). Influenza A virus infects the host cell by entry through endocytosis after the HA binds its receptor.

The HA receptors are sialic acids (SAs) on the cell surface glycoproteins and glycolipids (13–15). SAs are usually found in either an α2,3 or α2,6 linkage to galactose (Gal), which determines the host specificity for infection. Avian influenza viruses in general bind α2,3 linkage receptors, whereas human isolates predominantly bind α2,6 linkage receptors. However, swine viruses usually bind both. The binding mechanism has been delineated by virological, biochemical, and structural biology methods, and the major amino acids involved in receptor binding in the HA proteins have been defined (16).

It is known that HAs derived from the three pandemic viruses (the 1918 Spanish flu, 1957 Asia flu, and 1968 Hong Kong flu) preferentially bind α2,6 linkage receptors (1, 2, 16). For the 2009 pandemic viruses, the receptor binding specificity is complicated by the presence of a D225G substitution. Over 1% of all HA sequences from the 2009 pandemic viruses contained the avian-like residue G225 instead of the human-like residue D225 in H1 (17). Importantly, the D225G mutant viruses are related to a number of severe human infections and were transmitted locally in different countries (18–21). A similar D225G substitution was also observed in the 1918 pandemic viruses, generating mixed specificity for α2,6-linked and α2,3-linked glycans (22–24). Glycan binding assays and virus attachment studies further indicated that the 2009 pandemic viruses with a D225G substitution acquire dual receptor specificity for both α2,6-linked and α2,3-linked glycans (17, 25, 26). Thus, structural examination is necessary to understand the effect of these HA mutations on receptor binding specificity and transmission as well as to predict the behavior of new pandemic viruses in humans.

To elucidate the molecular characteristics of both 2009 pH1N1 HA (09H1) and 1918 pandemic HA (18H1), we used soluble transmembrane-removed HA to test its binding to α2,3 and α2,6 linkage receptors and to solve the structures of their protein-receptor complexes in this study. We further analyzed the D225G/E mutant proteins for receptor binding properties and protein-receptor complex structures. Using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to test binding, our results further demonstrated that both 09H1 and 18H1 preferentially bind α2,6 linkage human receptors, but their D225G variants bind both avian α2,3 linkage and human α2,6 linkage receptors. The complex structures revealed that the D225G substitution results in a loss of a salt bridge between amino acids D225 and K222, enabling the key residue Q226 to interact with the avian receptor, explaining the receptor binding switch.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning, expression, and purification.

The sequences corresponding to the HA ectodomain from A/California/04/2009 (09H1) and A/South Carolina/1/18 (18H1) were cloned into the baculovirus transfer vector pFastBac1 (Invitrogen). The constructs contain an N-terminal gp67 signal peptide for secretion, HA1 residues 11 to 329, HA2 residues 1 to 174 (H3 numbering), a C-terminal thrombin cleavage site, a trimerization foldon sequence, and a His6 tag at the extreme C terminus for purification, as previously reported (4). The 09H1-D225E, 09H1-D225G, and 18H1-D225G mutants were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis. Transfection and virus amplification were performed according to the Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression system manual (Invitrogen).

HA proteins were produced by infecting suspension cultures of Hi5 cells (Invitrogen) for 2 days. Soluble HA was recovered from the cell supernatant by metal affinity chromatography using a 5-ml HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare). Fractions containing HA were pooled and dialyzed against 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 50 mM NaCl and then subjected to ion-exchange chromatography (IEX) using a Mono-Q 4.6/100 PE column (GE Healthcare). IEX-purified HA proteins were subjected to thrombin digestion (3 U/mg HA overnight at 4°C; BD Biosciences) and purified by gel filtration chromatography using a Superdex-200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) and 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–50 mM NaCl as a running buffer. Collected proteins were concentrated to 6 mg/ml.

Crystal structure determination.

09H1, 09H1-D225E, and 18H1-D225G crystals were grown by the hanging-drop diffusion method with a reservoir solution (0.4 ml) of 10% polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG 6000), 5% (±)-2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD), and 0.1 M morpholineethanesulfonic acid (MES) (pH 6.5) at 18°C. The resulting crystals were cryoprotected by soaking in 2 μl well solution mixed with 1 μl 50% PEG 6000 and then flash-cooled in a cold nitrogen gas stream at 100 K. X-ray diffraction data were collected on Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) beamline 17U, using a MAR 225 charge-coupled-device (CCD) detector. The data were processed and scaled by using an HKL2000 instrument. Crystallographic data statistics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Parametera | Value (value for highest-resolution shell) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 09H1 + human receptor | 09H1-D225E | 09H1-D225E + human receptor | 18H1-D225G | 18H1-D225G + human receptor | 18H1-D225G + avian receptor | |

| Data collection | ||||||

| Space group | P1 | P1 | P1 | P3 | P21 | P21 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | ||||||

| a | 66.72 | 67.69 | 66.87 | 120.86 | 71.91 | 71.99 |

| b | 117.32 | 119.01 | 116.81 | 120.86 | 242.15 | 243.20 |

| c | 117.39 | 123.61 | 116.50 | 235.72 | 71.75 | 72.21 |

| Cell dimensions (°) | ||||||

| α | 61.78 | 115.14 | 62.06 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| β | 81.83 | 94.96 | 77.76 | 90.00 | 119.66 | 119.62 |

| γ | 77.42 | 96.78 | 81.54 | 120.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50–3 (3.00–3.11) | 50–3 (3.00–3.11) | 50–2.9 (2.90–3.00) | 50–2.7 (2.70–2.80) | 50–3 (3.00–3.11) | 50–2.8 (2.80–2.90) |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 0.119 (0.387) | 0.118 (0.378) | 0.125 (0.456) | 0.083 (0.473) | 0.120 (0.418) | 0.090 (0.515) |

| I/σI | 11.0 (2.4) | 10.3 (1.7) | 11.4 (1.7) | 16.7 (2.1) | 11.1 (2.2) | 15.9 (2.7) |

| Completeness (%) | 88.8 (59.9) | 93.8 (66.8) | 94.9 (74.2) | 98.7 (89.1) | 97.0 (82.2) | 99.8 (99.7) |

| Redundancy | 3.7 (3.0) | 3.6 (2.3) | 3.3 (2.7) | 3.9 (3.1) | 4.1 (3.4) | 4.3 (4.3) |

| Refinement | ||||||

| Resolution range (Å) | 38.4–3.0 | 46.7–3.0 | 40.2–2.9 | 47.9–2.7 | 38.2–3.0 | 38.4–2.8 |

| No. of reflections | 50,057 | 60,635 | 58,849 | 97,310 | 37,212 | 49,662 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.22/0.28 | 0.21/0.24 | 0.24/0.28 | 0.21/0.27 | 0.20/0.25 | 0.20/0.25 |

| No. of atoms | ||||||

| Protein | 22,987 | 23,131 | 23,022 | 23,404 | 11,631 | 11,631 |

| Ligand/ion | 267 | 0 | 300 | 0 | 90 | 45 |

| Water | 275 | 150 | 186 | 207 | 63 | 200 |

| B factors | ||||||

| Protein | 84.9 | 57.3 | 81.3 | 63.8 | 69.0 | 54.7 |

| Ligand/ion | 100.6 | 0 | 82.0 | 0 | 92.8 | 60.3 |

| Water | 41.1 | 53.0 | 51.5 | 47.2 | 42.3 | 41.1 |

| RMS deviations | ||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.135 | 0.958 | 0.968 | 0.826 | 0.802 | 0.821 |

RMS, root mean square.

The 09H1 structure was solved and reported previously (4); crystal soaking with receptors is described below. The structure of the 09H1-D225E mutant was solved at a 3.0-Å resolution by the molecular replacement method using the structure of 09H1 as the search model (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession number 3AL4). The structure of the 18H1-D225G mutant was solved at a 3.0-Å resolution by the molecular replacement method using the structure of 18H1 as the search model (PDB accession number 2WRG).

Crystals for data sets of HAs with bound receptor were prepared by soaking the crystals in 10 mM pentasaccharide LSTc or LSTa (prepared in cryobuffer) for 4 h. LSTc and LSTa represent α2-6 and α2-3-linked glycan analogs of human and avian recepors, respectively. The data collection and structure determinations were performed similarly to that for the native crystals.

SPR measurements and affinity analysis.

The affinity and kinetics of the binding of soluble HAs to receptor analogs were analyzed at 25°C on a BIAcore 3000 machine with streptavidin chips (SA chips; GE Healthcare) by SPR. PBST buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] with 0.005% Tween 20 [pH 7.4]) was used for all measurements. For SPR measurements, thrombin-digested HAs were purified by gel filtration using PBST buffer as a running buffer. Eluted protein was then concentrated to 6 mg/ml. Two biotinylated receptor analogs, the α2,6 glycans (6′S-Di-LN, Neu5Aca2-6[Galb1-4GlcNAcb1-3]2b-SpNH-LC-LC-biotin) and the α-2,3 glycans (3′S-Di-LN, Neu5Aca2-3[Galb1-4GlcNAcb1-3]2b-SpNH-LC-LC-biotin), were kindly provided by the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (Scripps Research Institute Department of Molecular Biology, La Jolla, CA). We used the blank channel as a negative control. Approximately 450 response units of biotinylated glycans were immobilized on the chip, followed by blockage with 100 μl 10 mM free biotin. Kinetics analysis was performed by applying a series of concentrations ranging from 0.625 to 10 μM. When the data collection was finished in each cycle, the sensor surface was regenerated with 10 mM NaOH. Sensograms were locally fitted with BIAcore 3000 analysis software (BIAevaluation version 4.1), using a 1:1 Langmuir binding mode with the HA monomer as an identity from the trimer preparation. On- and off-rates were determined from the concentration-dependent fits, and the KD (equilibrium dissociation constant) was calculated. The affinity values for 09H1, 18H1, and the D225G mutants for their receptors were calculated with a simultaneous kinetic Ka (association rate)/Kd (dissociation rate) model.

Protein structure accession numbers.

The crystal structures were deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession numbers 4JTV, 4JTX, 4JUO, 4JUG, 4JUH, and 4JUJ.

RESULTS

Both 09H1 and 18H1 preferentially bind the α2,6 linkage human receptor with slow kinetics.

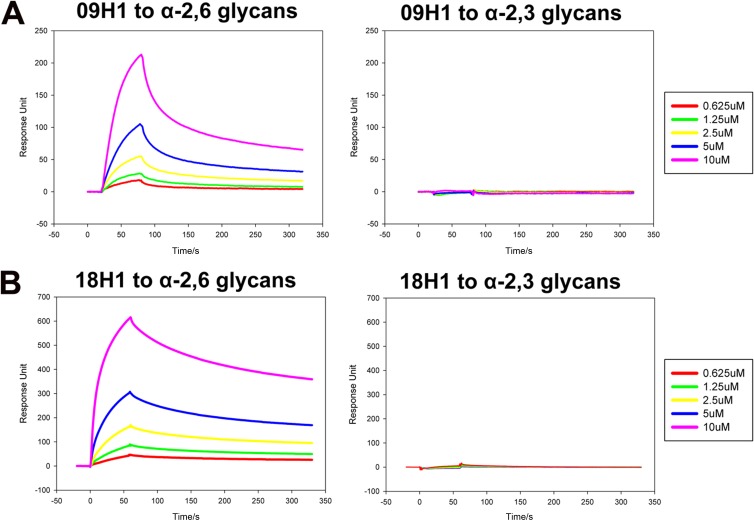

Receptor binding was tested by using the biosensor SPR method with a BIAcore machine and soluble proteins prepared in a baculovirus expression system, as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 1, 09H1 and 18H1 specifically bind to α2,6 linkage sialylated glycans, which is in accordance with previous reports (17, 24, 25). The affinity of 09H1 and 18H1 binding to α2,6 linkage sialylated glycans is in the micromolar range, with KD values of 3.74 and 13.7 μM, respectively (Table 1). Strikingly, the binding half-life of 09H1 and 18H1 with the α2,6 linkage sialic acid was extremely long (Koff = 1.19 × 10−3 and 1.7 × 10−3 s−1, respectively).

Fig 1.

BIAcore binding properties of the HAs to α2,3-linked sialylglycan avian and α2,6-linked sialylglycan human receptors. Shown are BIAcore diagrams of 09H1 (A) and 18H1 (B) binding to the two receptors, showing strong binding to the α2,6-linked sialylglycan human receptor but no binding to the α2,3-linked sialylglycan avian receptor.

Table 1.

Kinetics data for 18H1, 09H1, and their mutantsa

| HA | Glycan | Kd (μM) | Kon (1/Ms) | Koff (1/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 09H1 | α2,6 | 3.74 | 319 | 0.00119 |

| 09H1 | α2,3 | N | N | N |

| 09H1-D225G | α2,6 | 0.475 | 3,650 | 0.00173 |

| 09H1-D225G | α2,3 | 2.24 | 1,460 | 0.00327 |

| 09H1-D225E | α2,6 | 0.768 | 1,800 | 0.00138 |

| 09H1-D225E | α2,3 | N | N | N |

| 18H1 | α2,6 | 13.7 | 125 | 0.0017 |

| 18H1 | α2,3 | N | N | N |

| 18H1-D225G | α2,6 | 8.35 | 531 | 0.00444 |

| 18H1-D225G | α2,3 | 4.73 | 984 | 0.00466 |

N, no binding.

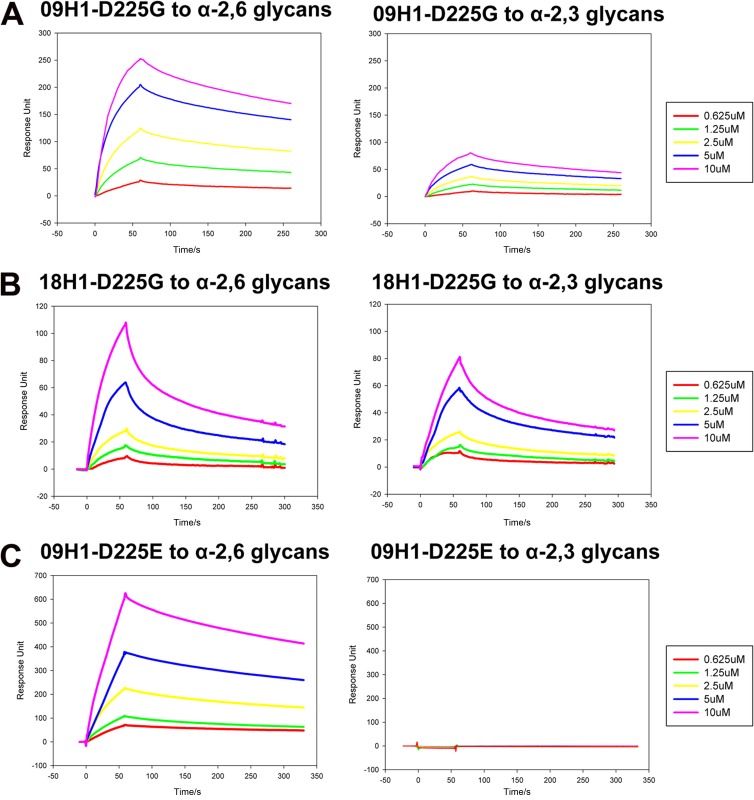

Differential receptor binding specificities for the 09H1-D225G and -D225E HAs.

In the later stage of the 2009 pandemic, viruses with D225G/E were isolated, and the D225G substitution was especially related to cases with severe disease outcomes (20, 21, 27). Thus, we next asked if the D225G substitution (H3 numbering) in 09H1 would change the receptor binding specificity as it does in 18H1 (22, 28, 29). Here, SPR experiments were performed to test the receptor binding properties of the HA mutants of both the 2009 and 1918 pandemic viruses. The affinities of the HA mutants for the receptor analogs were still in the micromolar range (Table 1). 18H1 and 09H1 have very similar binding properties. However, the D225G substitution shifts the binding specificity from the α2,6 linkage receptor preference to dual α2,3 linkage and α2,6 linkage receptor specificity (Fig. 2A and B). According to the SPR results (Table 1), we found that the affinities of the D225G mutants of both 18H1 and 09H1 are higher than that of the wild type, indicating even stronger binding to both receptors. This is likely why most of the viruses containing the D225G substitution contribute to higher mortality, as the dual specificity could facilitate entry of the mutant influenza virus into the deeper respiratory tract and lung (17, 28). Indeed, the α2,3 linkage receptor is the major receptor type in the human lung (30). Furthermore, for the 09H1-D225E mutant, the binding preference was the same as that of wild-type 09H1 but with a higher affinity (Fig. 2C and Table 1).

Fig 2.

BIAcore binding properties of the HA mutants to α2,3-linked sialylglycan avian and α2,6-linked sialylglycan human receptors. (A) BIAcore diagram of 09H1-D225G mutant binding to the two receptors showing dual receptor binding specificity. (B) BIAcore diagram of 18H1-D225G mutant binding to the two receptors showing dual receptor binding specificity. (C) BIAcore diagram of 09H1-D225E binding to the two receptors showing strong binding to the α2,6-linked sialylglycan human receptor but no binding to the α2,3-linked sialylglycan avian receptor.

Structural analysis of 18H1, 09H1, and their mutants bound to ligands.

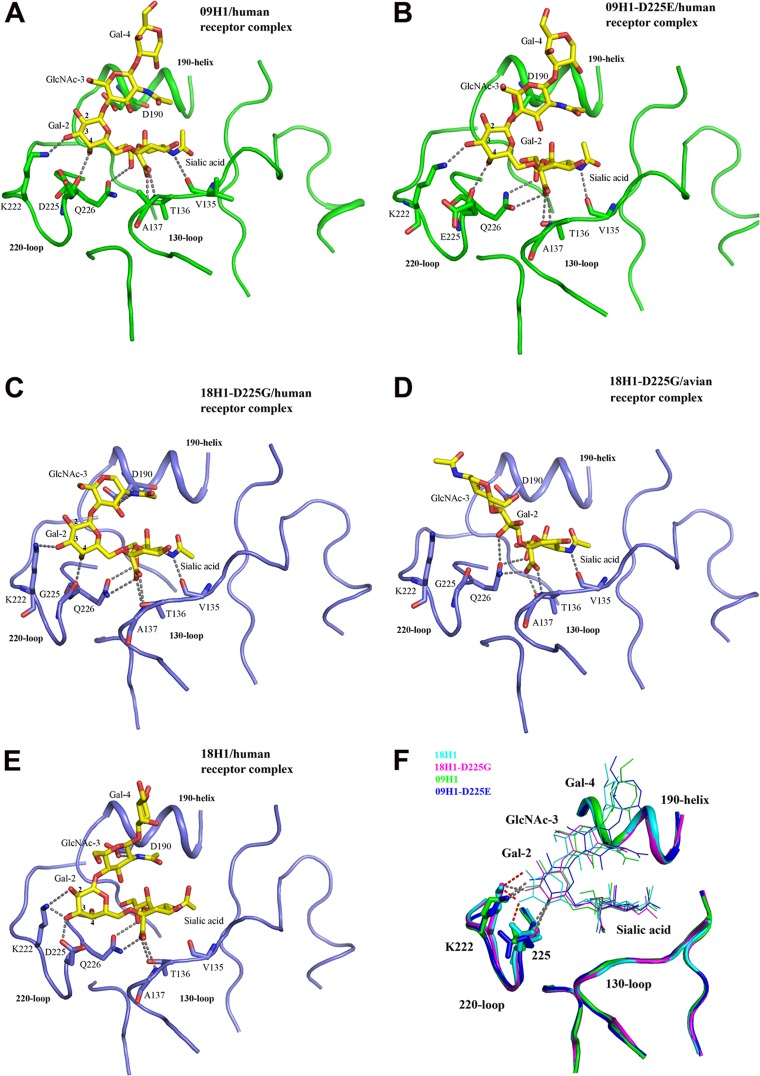

The receptor binding sites, located on the top of each subunit of the HA trimer, consist of three secondary elements, the 190 helix (residues 190 to 198), the 130 loop (residues 135 to 138), and the 220 loop (residues 221 to 228), which form the sides of the receptor binding sites, as well as a base formed by the conserved residues Y98, W153, H183, and Y195 (11). To understand the receptor binding properties of 09H1 and the mechanism for the binding specificity shift in both 18H1 and 09H1 due to the D225G substitution, we determined the structures of 09H1, the 09H1-D225E mutant, and the 18H1-D225G mutant with and without α2,6- and α2,3-linked sialopentasaccharides as analogs of avian and human receptors. These structures were solved by molecular replacement, and crystallographic statistics are given in Table 2. As observed with other H1 HAs, the terminal SAs of the human and avian receptors interact with binding-site residues both through a series of conserved hydrogen bonds and via a previously unknown interaction between Q226 and Sia-1 (see Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

Interactions of 09H1, 09H1-D225E, 18H1, and 18H1-D225G with human receptor and avian receptor analogs. The three secondary structure elements of the binding site are shown in a ribbon representation, i.e., the 190 helix and the 130 and 220 loops. The residues important for receptor binding are shown in a stick representation. The broken lines indicate potential hydrogen bonds between the protein and the receptors. The sialosaccharides are shown in yellow for carbon atoms, blue for nitrogen, and red for oxygen. (A and B) 09H1 (A) and 09H1-D225E (B) in complex with the human receptor. In both cases, the HA backbone and carbon atoms are green. (C to E) 18H1-D225G in complex with the human receptor (C), 18H1-D225G in complex with the avian receptor (D), and 18H1 in complex with the human receptor (E). In these cases, the backbone and carbon atoms of the HA are blue. (F) Differences in the orientations of bound human receptor in the receptor binding sites of 09H1, 18H1, and their mutants. The receptor binding sites of 18H1 (cyan), 18H1-D225G (magenta), 09H1 (green), and 09H1-D225E (blue) were superimposed by fixing the 190 helix. The sialopentasaccharides are colored according to the HAs to which they are bound and are shown in a line representation. Residues K222 and D/G225 are shown in a stick representation, and the hydrogen bond interactions are shown as broken lines for 18H1 (red), 18H1-D225G (gray), 09H1 (gray), and 09H1-D225E (gray). The bound receptors in the 18H1-D225G, 09H1, and 09H1-D225E structures have similar orientations, while the bound receptor in the 18H1 structure sits lower than in the other three H1s.

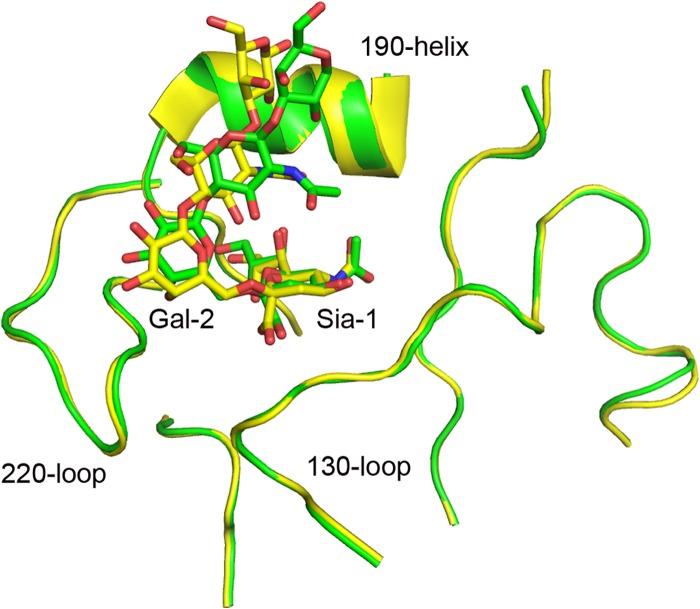

While we were preparing the manuscript, the Wilson group reported the structural basis of the preferential binding of 09H1 to α2,6-linked receptors using an engineered HA in which a disulfide was introduced to stabilize the protein (31). However, in our case, the native sequence was used to obtain the 09H1 protein without any modification. Therefore, this provides a unique chance to compare our complex with the complex reported by the Wilson group (Fig. 3) to confirm if the introduced disulfide bond had any effect on receptor binding. Indeed, when the two structures were superimposed, we found that they match very well (Fig. 3). In the 09H1-human receptor complex (Fig. 4A), the electron density maps revealed well-ordered features for the Sia-1, Gal-2, GlcNAc-3, and Gal-4 of the sialopentasaccharide in the complex. Sia-1 forms four hydrogen bonds with the binding site: three bonds between Sia-1 and the 130 loop, which are conserved in other H1-receptor complexes, and the fourth between the 8-hydroxyl of Sia-1 and the side chain of Q226. Gal-2 forms two hydrogen bonds with the 220 loop. One is formed between the 3-hydroxyl of Gal-2 and the side chain of K222, and the other is formed between the 4-hydroxyl of Gal-2 and the main-chain carbonyl of D225. In the 09H1-D225E–human receptor complex (Fig. 4B), the interaction between the receptor analog and the binding site is nearly the same as that of the 09H1-human receptor complex, except that one extra hydrogen bond exists between the 1-carbonyl of Sia-1 and the side chain of Q226.

Fig 3.

Comparison between 09H1-LSTc (green) and the previously determined 09H1-LSTc (yellow) structures. The Wilson group used an engineered 09H1 protein with an artificial disulfide bond to investigate the HA-ligand interaction. In our case, we used unmodified 09H1 protein. Structural superimposition reveals that the glycan ligands bind similarly in both of the complex structures, with some differences in the position of Gal-2, which may be due to the different resolutions of the structures.

Liu et al. (32) previously solved the 18H1-human receptor complex (Fig. 4E). Comparison of 09H1-human receptor and 18H1 complexes revealed that the Sia-1, Gal-2, GlcNAc-3, and Gal-4 moieties of the sialopentasaccharide are ordered in both complexes. In the 18H1-human receptor complex, Sia-1 also forms four hydrogen bonds with the binding site. Only two bonds are formed between Sia-1 and the 130 loop, while the other two are formed between the 1-carbonyl and 8-hydroxyl of Sia-1 and the side chain of Q226. Gal-2 forms three hydrogen bonds with the 220 loop, between the 2- and 3-hydroxyls of Gal-2 and the side chains of K222 and D225. GlcNAc-3 forms a hydrogen bond with the 190 helix, between the side chain of D190 and the amino nitrogen of GlcNAc-3.

In the 18H1-D225G–human receptor complex, only the Sia-1, Gal-2, and GlcNAc-3 moieties of the sialopentasaccharide were observed (Fig. 4C). Sia-1 forms five hydrogen bonds with the binding site. Unlike the 18H1-human receptor complex, three bonds are formed between Sia-1 and the 130 loop, which is conserved in other H1-human receptor complexes. Gal-2 forms two hydrogen bonds with the 220 loop, which is the same as in the 09H1-human receptor and 09H1-D225E–human receptor complexes. Moreover, GlcNAc-3 forms a hydrogen bond with the 190 helix as in the 18H1-human receptor complex.

In the 18H1-D225G–avian receptor complex (Fig. 4D), only the Sia-1, Gal-2, and GlcNAc-3 moieties of the sialopentasaccharide are again ordered. Three hydrogen bonds are formed between Sia-1 and the 130 loop, with the key residue Q226 forming three hydrogen bonds with the 1-carbonyl and 8-hydroxyl of Sia-1 and the 4-hydroxyl of Gal-2. Thus, Q226 plays a key role in binding of the avian receptor by human H1 HAs.

Complexes of the human receptor analog bound to 18H1, 18H1-D225G, 09H1, and 09H1-D225E are superimposed in Fig. 4F. Perhaps the most important feature of this comparison is the difference in the position of Gal-2. This moiety in the 18H1-human receptor complex structure is positioned more toward the 220 loop than in the other three complex structures. Due to these different conformations, the Gal-2 in the 18H1-human receptor complex structure forms a hydrogen bond with the side chain of D225, while the Gal-2 in the other three complex structures forms a hydrogen bond with the main chain of D225.

Proposed structural basis and key residues affecting the binding specificity of H1 HAs.

Changes in receptor binding specificity are required for cross-species transmission, especially when the virus jumps from avian species to mammals (i.e., swine and humans) (11). For different subtypes, the mechanism which human viruses have used to achieve these changes appears to be different (16). For the HAs of H2 and H3 human viruses, changes in only two amino acids in the binding site, Q226L and G228S, are associated with the shift from avian to human receptor binding (33). However, for HAs of human H1 viruses, the ability to bind to human receptors occurs while retaining Q226 and G228, and the mechanism is much more complicated. In the case of the 1934 human and 1930 swine HAs (34), Q226 plays an essentially passive role in binding to the human receptor, in marked contrast to the role played by L226 in the binding of human H3 HA to the human receptor. However, in the case of 09H1 and 18H1, Q226 plays a positive role in binding to the human receptor. Similarly, Q226 also plays a key role in binding to the avian receptor in the 18H1-D225G mutant.

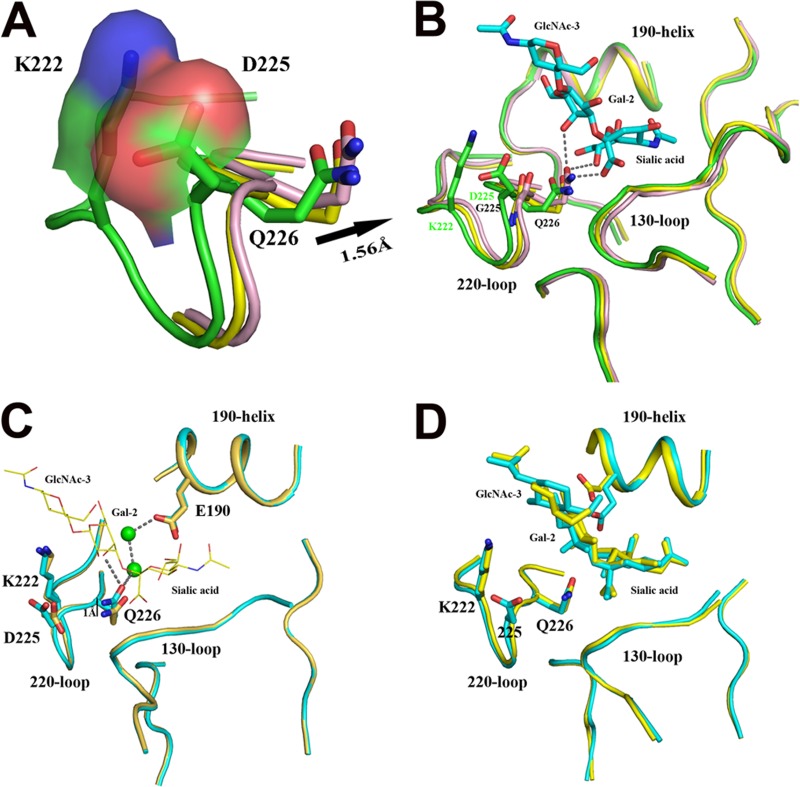

Previously, Skehel and colleagues (34) proposed a mechanism to explain how the human receptor-specific H1 influenza viruses obtain dual binding specificity (Fig. 5C). They hypothesized that E190 interacts with Q226 through two water molecules, and as a result, this network of hydrogen bonds positions Q226 higher in the binding site for its interaction with Gal-2. Here, we elucidated another mechanism for the human H1 HAs that contain an Asp residue at position 190, and the amino acid at position 225 is very important for the interaction of Q226 with Gal-2. Normally, the K222 and D225 residues form a salt bridge to restrict the 220 loop in the 09H1 and 18H1 structures (Fig. 5A). However, when the D225G substitution occurs, the salt bridge between K222 and D225 disappears, and the 220 loop is more flexible, facilitating the forward movement of Q226 by ∼1.56 Å to interact with Gal-2 of the avian receptor (Fig. 5B). In the absence of D225G, the HAs will have a human receptor preference. The D225E mutant of 09H1 also confirms this proposed mechanism, as the negative E residue can also form a salt bridge with K222 and limit the movement of Q226, restricting the HA to a human receptor preference. Finally, via either mechanism, the orientation of the avian receptor is almost the same (Fig. 5D).

Fig 5.

Mechanism for the dual receptor binding specificity of H1 HAs containing the D225G substitution. (A) Superimposition of the binding site of 18H1 (green) and 18H1-D225G in its uncomplexed state (yellow) and complexed state (pink) with the avian receptor analog. In 18H1, K222 and D225 form a salt bridge to restrict the 220 loop. (B) However, in 18H1-D225G, the loss of the salt bridge makes the 220 loop flexible, and residue Q226 can move forward by ∼1.56 Å and interact with the avian receptor analog through three hydrogen bonds. (C) In the case of the 1934 human HA with D at position 225, E190 lifts Q226 by ∼1 Å through two water molecules (green spheres), mediated by a hydrogen bond network, and Q226 can interact with the avian receptor analog. The free state of 1934 human HA is colored in light orange, and the bound state of 1934 human HA is colored in cyan. (D) Superimposition of the bound avian receptor in the receptor binding sites of the 1934 human HA (cyan) and 18H1-D225G (yellow). The bound receptors have almost the same orientations.

In conclusion, for either human receptor binding or avian receptor binding, excluding the conserved Y98, W153, H183, and Y195 residues, there are conserved interactions between the SA and the 130 loop (amino acids at positions 135 to 137). For human receptor binding, the interactions between Gal-2 and the 220 loop (K222 and the amino acid at position 225) are necessary, while the interactions with the amino acids at positions 226 and 190 are alternative. For avian receptor binding, residue Q226 plays a key role. The amino acids at position 225 or 190 can affect the binding specificity. As summarized in Table 3, the D190 plus G225 and E190 plus D225 combinations enable dual receptor binding specificity. For the D190 plus D225 and D190 plus E225 combinations, binding is preferential for the human receptor. For the combination of E190 and G225, binding is preferential for the avian receptor.

Table 3.

Residue types at three positions in the binding sites of different H1 HAs are correlated with receptor binding specificity

| H1 HA type | Residue at position: |

Bindinga |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 190 | 222 | 225 | α2,3 | α2,6 | |

| 1918 human | D | K | D | − | + |

| 1918 human-D225G | D | K | G | + | + |

| 1930 swine | D | K | G | + | + |

| 1934 human | E | K | D | + | + |

| 1976 avian | E | K | G | + | + |

| 2005 avian | E | K | G | + | + |

| 2009 human | D | K | D | − | + |

| 2009 human-D225G | D | K | G | + | + |

| 2009 human-D225E | D | K | E | − | + |

Binding is shown as “+,” and no binding is shown as “−.”

DISCUSSION

The 2009 pH1N1 virus can transmit from human to human extremely rapidly, which led the WHO to claim that it caused a pandemic in June 2009, just 2 months after the first H1N1 cases were reported in Mexico (2). The molecular mechanism of the fast transmission is yet to be understood. Previous reports indicated that the 2009 pH1N1 virus has a high level of resemblance to the 1918 pandemic virus (35), which killed over 20 million people worldwide, making it the most devastating infectious disease in recorded history. Here, using SPR, we confirmed that both 09H1 and 18H1 preferentially bind to α2,6-linked SA with remarkably low off-rates. Furthermore, the affinities are much higher than those (mM range) previously determined by using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (13), as we calculated the affinities assuming a 1:1 binding mode. However, the HA protein is a multivalent trimer, and the affinity calculation may be overestimated in our case.

Previously, Maines et al. reported that soluble 09H1 binds to an α2,6 linkage receptor with little or no binding to an α2,3 linkage receptor, based on a dose-dependent microarray method (36), and these results were recently confirmed by Xu et al. (31). However, Childs et al. reported that the 09H1 virus can bind to both the α2,6 linkage and α2,3 linkage receptors due to high-avidity cooperative binding of the virus, unlike the low affinity of the individual HA molecules binding to their oligosaccharide receptors (37). This discrepancy may be due to the binding difference between the entire virus and the soluble HAs. However, it should be noted that the data reported by Childs et al. (37), when scrutinized, show that the binding affinity of the virus for different forms (different sugar linkages) of the α2,3 linkage receptor is quite low, and many fewer receptor forms in their glycomicroarrays displayed binding than that of the α2,6 linkage receptors which they used (see Fig. 1 in reference 36). This implies stronger binding to the α2,6 linkage receptor, which is consistent with our data.

The D225G/E mutants found in patients during the later stage of the 2009 pandemic revealed an adaptation process similar to that of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus (38). There were two major 1918 viruses circulating during the 1918 pandemic: the wild type and an HA D225G mutant (39). The latter binds both human and avian receptors (22) and has receptor binding properties similar to those of the D225G mutant of 2009 pH1N1, as revealed by our group and others (17, 26). In contrast, the D225E mutant was more similar to wild-type 09H1, preferentially binding to the α2,6-linked SA (human receptor), implying that the two mutants give rise to different biological outcomes. The dual receptor binding specificity switch of the D225G mutant may help the virus enter the deeper airway and cause inflammation in the lung, resulting in increased mortality.

Under strong immune pressure, influenza viruses can use an antigenic variation approach to survive in the host. During antigenic variation, many amino acid changes occur near the receptor binding site. Compared to H2 and H3 HAs, the changes observed in the receptor binding site are different in H1 HA. In both H2 and H3 HAs, residues 226 (Q to L) and 228 (G to S) are the major differences between the avian and human viruses. However, in H1 HA, residue 226 is usually an aspartate, and substitutions at residues 138, 190, and 225 are instead important (23, 24, 40). Here, we elucidated the structural basis of the dual receptor binding specificity of the D225G mutant and summarize how the different amino acid combinations at residues 190 and 225 affect the receptor binding specificity of H1 subtype viruses. These data may help us to predict the transmission of H1 subtype viruses in different species.

We directly observed that the D225G substitution results in a loss of a salt bridge between D225 and K222, loosening the 220 loop and enabling the key residue Q226 to interact with the avian receptor to enable dual receptor binding properties. In contrast, the Wilson group suggested that the D225G substitution induces a distinct conformation of the 220 loop resulting from a difference in the backbone conformation of G225 (31). Both models are plausible, and it is likely that both the salt bridge loss and backbone conformational change induce the flexibility of the 220 loop.

In conclusion, our biophysical and structural analyses of wild-type and mutant HAs imply that the rapid human-to-human transmission of the 2009 pandemic swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus may be partially explained by HA's high binding affinity and long binding half-life for the α2,6 linkage receptor. Furthermore, the 09H1 HA truly has some characteristics similar to those of the 1918 pandemic HA. The D225G/E mutants found in the later stage of the 2009 pandemic have different biological implications due to different receptor binding specificities. Close surveillance of emerging viruses and investigation into the biological significance of their mutations are crucial for the control of and preparedness for possible future pandemics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National 973 Project (grant no. 2011CB504703) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (grant no. 81021003). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. G.F.G. is a leading principal investigator of the NSFC Innovative Research Group.

We thank Lijun Bi (IBPCAS), Yuanyuan Chen (IBPCAS), Hui Niu (NIBS), Jijie Chai (NIBS), Taijiao Jiang (IBPCAS), Maojun Yang (Tsinghua University), Zhijie Liu (IBPCAS), Jinsong Liu (GIBHCAS), Di Liu (IMCAS), and Christopher J. Vavricka (IMCAS) for their help in performing the experiments and writing the manuscript. We are grateful to James Paulson of the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (Scripps Research Institute Department of Molecular Biology, La Jolla, CA) for providing the sialic acid analogs. We acknowledge assistance by the staff (especially Jianhua He and Sheng Huang) at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) (beamline 17U).

G.F.G. conceived of and supervised the research and designed the study; W.Z., Y.S., and Q.L. performed protein expression, purification, and crystallization; J.Q. and F.G. performed the crystal data collection and solved the crystal structure; Y.S., W.Z., and Z.F. performed the BIAcore binding experiments; G.F.G., Y.S., W.Z., J.Y., and J.Q. performed the data analysis; and G.F.G., Y.S., and W.Z. wrote the manuscript.

We declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 20 March 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Kilbourne ED. 2006. Influenza pandemics of the 20th century. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:9–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neumann G, Noda T, Kawaoka Y. 2009. Emergence and pandemic potential of swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus. Nature 459:931–939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gao GF, Sun Y. 2010. It is not just AIV: from avian to swine-origin influenza virus. Sci. China Life Sci. 53:151–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang W, Qi J, Shi Y, Li Q, Gao F, Sun Y, Lu X, Lu Q, Vavricka CJ, Liu D, Yan J, Gao GF. 2010. Crystal structure of the swine-origin A (H1N1)-2009 influenza A virus hemagglutinin (HA) reveals similar antigenicity to that of the 1918 pandemic virus. Protein Cell 1:459–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guan Y, Vijaykrishna D, Bahl J, Zhu H, Wang J, Smith GJ. 2010. The emergence of pandemic influenza viruses. Protein Cell 1:9–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sun Y, Shi Y, Zhang W, Li Q, Liu D, Vavricka C, Yan J, Gao GF. 2010. In silico characterization of the functional and structural modules of the hemagglutinin protein from the swine-origin influenza virus A (H1N1)-2009. Sci. China Life Sci. 53:633–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Medina RA, Garcia-Sastre A. 2011. Influenza A viruses: new research developments. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9:590–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen W, Calvo PA, Malide D, Gibbs J, Schubert U, Bacik I, Basta S, O'Neill R, Schickli J, Palese P, Henklein P, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. 2001. A novel influenza A virus mitochondrial protein that induces cell death. Nat. Med. 7:1306–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wise HM, Foeglein A, Sun J, Dalton RM, Patel S, Howard W, Anderson EC, Barclay WS, Digard P. 2009. A complicated message: identification of a novel PB1-related protein translated from influenza A virus segment 2 mRNA. J. Virol. 83:8021–8031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jagger BW, Wise HM, Kash JC, Walters KA, Wills NM, Xiao YL, Dunfee RL, Schwartzman LM, Ozinsky A, Bell GL, Dalton RM, Lo A, Efstathiou S, Atkins JF, Firth AE, Taubenberger JK, Digard P. 2012. An overlapping protein-coding region in influenza A virus segment 3 modulates the host response. Science 337:199–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 2000. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:531–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tong S, Li Y, Rivailler P, Conrardy C, Castillo DA, Chen LM, Recuenco S, Ellison JA, Davis CT, York IA, Turmelle AS, Moran D, Rogers S, Shi M, Tao Y, Weil MR, Tang K, Rowe LA, Sammons S, Xu X, Frace M, Lindblade KA, Cox NJ, Anderson LJ, Rupprecht CE, Donis RO. 2012. A distinct lineage of influenza A virus from bats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:4269–4274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sauter NK, Bednarski MD, Wurzburg BA, Hanson JE, Whitesides GM, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 1989. Hemagglutinins from two influenza virus variants bind to sialic acid derivatives with millimolar dissociation constants: a 500-MHz proton nuclear magnetic resonance study. Biochemistry 28:8388–8396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Takemoto DK, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 1996. A surface plasmon resonance assay for the binding of influenza virus hemagglutinin to its sialic acid receptor. Virology 217:452–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gambaryan AS, Tuzikov AB, Piskarev VE, Yamnikova SS, Lvov DK, Robertson JS, Bovin NV, Matrosovich MN. 1997. Specification of receptor-binding phenotypes of influenza virus isolates from different hosts using synthetic sialylglycopolymers: non-egg-adapted human H1 and H3 influenza A and influenza B viruses share a common high binding affinity for 6′-sialyl(N-acetyllactosamine). Virology 232:345–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gamblin SJ, Skehel JJ. 2010. Influenza hemagglutinin and neuraminidase membrane glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 285:28403–28409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chutinimitkul S, Herfst S, Steel J, Lowen AC, Ye J, van Riel D, Schrauwen EJ, Bestebroer TM, Koel B, Burke DF, Sutherland-Cash KH, Whittleston CS, Russell CA, Wales DJ, Smith DJ, Jonges M, Meijer A, Koopmans M, Rimmelzwaan GF, Kuiken T, Osterhaus AD, Garcia-Sastre A, Perez DR, Fouchier RA. 2010. Virulence-associated substitution D222G in the hemagglutinin of 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus affects receptor binding. J. Virol. 84:11802–11813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Puzelli S, Facchini M, Spagnolo D, De Marco MA, Calzoletti L, Zanetti A, Fumagalli R, Tanzi ML, Cassone A, Rezza G, Donatelli I. 2010. Transmission of hemagglutinin D222G mutant strain of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:863–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen GW, Shih SR. 2009. Genomic signatures of influenza A pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:1897–1903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kilander A, Rykkvin R, Dudman SG, Hungnes O. 2010. Observed association between the HA1 mutation D222G in the 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus and severe clinical outcome, Norway 2009–2010. Euro Surveill. 15(9):pii=19498. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mak GC, Au KW, Tai LS, Chuang KC, Cheng KC, Shiu TC, Lim W. 2010. Association of D222G substitution in haemagglutinin of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) with severe disease. Euro Surveill. 15(14):pii=19534. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19534 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Glaser L, Stevens J, Zamarin D, Wilson IA, Garcia-Sastre A, Tumpey TM, Basler CF, Taubenberger JK, Palese P. 2005. A single amino acid substitution in 1918 influenza virus hemagglutinin changes receptor binding specificity. J. Virol. 79:11533–11536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tumpey TM, Maines TR, Van Hoeven N, Glaser L, Solorzano A, Pappas C, Cox NJ, Swayne DE, Palese P, Katz JM, Garcia-Sastre A. 2007. A two-amino acid change in the hemagglutinin of the 1918 influenza virus abolishes transmission. Science 315:655–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stevens J, Blixt O, Glaser L, Taubenberger JK, Palese P, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. 2006. Glycan microarray analysis of the hemagglutinins from modern and pandemic influenza viruses reveals different receptor specificities. J. Mol. Biol. 355:1143–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu Y, Childs RA, Matrosovich T, Wharton S, Palma AS, Chai W, Daniels R, Gregory V, Uhlendorff J, Kiso M, Klenk HD, Hay A, Feizi T, Matrosovich M. 2010. Altered receptor specificity and cell tropism of D222G hemagglutinin mutants isolated from fatal cases of pandemic A(H1N1) 2009 influenza virus. J. Virol. 84:12069–12074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang H, Carney P, Stevens J. 2010. Structure and receptor binding properties of a pandemic H1N1 virus hemagglutinin. PLoS Curr. 2:RRN1152 doi:10.1371/currents.RRN1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen H, Wen X, To KK, Wang P, Tse H, Chan JF, Tsoi HW, Fung KS, Tse CW, Lee RA, Chan KH, Yuen KY. 2010. Quasispecies of the D225G substitution in the hemagglutinin of pandemic influenza A(H1N1) 2009 virus from patients with severe disease in Hong Kong, China. J. Infect. Dis. 201:1517–1521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brookes SM, Nunez A, Choudhury B, Matrosovich M, Essen SC, Clifford D, Slomka MJ, Kuntz-Simon G, Garcon F, Nash B, Hanna A, Heegaard PM, Queguiner S, Chiapponi C, Bublot M, Garcia JM, Gardner R, Foni E, Loeffen W, Larsen L, Van Reeth K, Banks J, Irvine RM, Brown IH. 2010. Replication, pathogenesis and transmission of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus in non-immune pigs. PLoS One 5:e9068 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takemae N, Ruttanapumma R, Parchariyanon S, Yoneyama S, Hayashi T, Hiramatsu H, Sriwilaijaroen N, Uchida Y, Kondo S, Yagi H, Kato K, Suzuki Y, Saito T. 2010. Alterations in receptor-binding properties of swine influenza viruses of the H1 subtype after isolation in embryonated chicken eggs. J. Gen. Virol. 91(Part 4):938–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shinya K, Ebina M, Yamada S, Ono M, Kasai N, Kawaoka Y. 2006. Avian flu: influenza virus receptors in the human airway. Nature 440:435–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xu R, McBride R, Nycholat CM, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. 2012. Structural characterization of the hemagglutinin receptor specificity from the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. J. Virol. 86:982–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu J, Stevens DJ, Haire LF, Walker PA, Coombs PJ, Russell RJ, Gamblin SJ, Skehel JJ. 2009. Structures of receptor complexes formed by hemagglutinins from the Asian influenza pandemic of 1957. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:17175–17180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eisen MB, Sabesan S, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 1997. Binding of the influenza A virus to cell-surface receptors: structures of five hemagglutinin-sialyloligosaccharide complexes determined by X-ray crystallography. Virology 232:19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gamblin SJ, Haire LF, Russell RJ, Stevens DJ, Xiao B, Ha Y, Vasisht N, Steinhauer DA, Daniels RS, Elliot A, Wiley DC, Skehel JJ. 2004. The structure and receptor binding properties of the 1918 influenza hemagglutinin. Science 303:1838–1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xu R, Ekiert DC, Krause JC, Hai R, Crowe JE, Jr, Wilson IA. 2010. Structural basis of preexisting immunity to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza virus. Science 328:357–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maines TR, Jayaraman A, Belser JA, Wadford DA, Pappas C, Zeng H, Gustin KM, Pearce MB, Viswanathan K, Shriver ZH, Raman R, Cox NJ, Sasisekharan R, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. 2009. Transmission and pathogenesis of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza viruses in ferrets and mice. Science 325:484–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Childs RA, Palma AS, Wharton S, Matrosovich T, Liu Y, Chai W, Campanero-Rhodes MA, Zhang Y, Eickmann M, Kiso M, Hay A, Matrosovich M, Feizi T. 2009. Receptor-binding specificity of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus determined by carbohydrate microarray. Nat. Biotechnol. 27:797–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Alonso M, Rodriguez-Sanchez B, Giannella M, Catalan P, Gayoso J, Lopez Bernaldo de Quiros JC, Bouza E, Garcia de Viedma D. 2011. Resistance and virulence mutations in patients with persistent infection by pandemic 2009 A/H1N1 influenza. J. Clin. Virol. 50:114–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reid AH, Fanning TG, Hultin JV, Taubenberger JK. 1999. Origin and evolution of the 1918 “Spanish” influenza virus hemagglutinin gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:1651–1656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rogers GN, D'Souza BL. 1989. Receptor binding properties of human and animal H1 influenza virus isolates. Virology 173:317–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]