Abstract

Objective

To compare Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) incidence rates during a 6-year period among five geographically diverse academic medical centers across the United States using recommended standardized CDI surveillance definitions that incorporate recent healthcare facility (HCF) exposures.

Methods

Data on C. difficile toxin assay results and dates of admission, discharge and assays were collected from electronic hospital databases. Chart review was performed for patients with a positive C. difficile toxin assay identified within 48 hrs of admission to determine HCF exposures in the 90 days prior to hospital admission. CDI cases, defined as any inpatient with a positive stool toxin assay for C. difficile, were categorized into five surveillance definitions based on recent HCF exposure. Annual CDI rates were calculated and evaluated with chi-square test for trend and chi-square summary tests.

Results

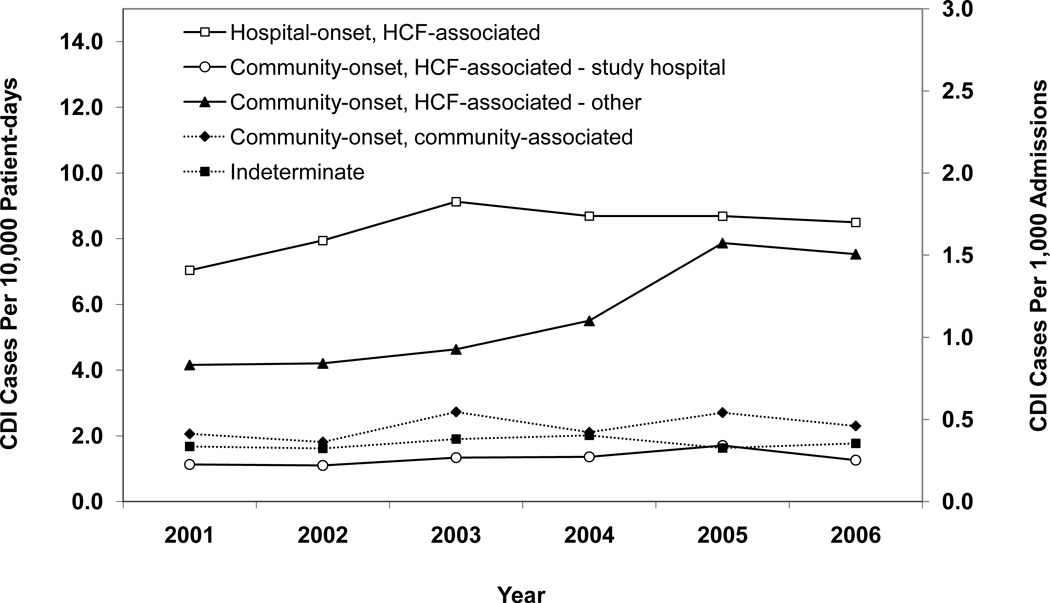

Over the study period, there were significant increases in the overall incidence rates of hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI (7.0 to 8.5 cases/10,000 patient days (p < 0.001)); community-onset, HCF-associated – study hospital CDI (1.1 to 1.3 cases/10,000 patient-days (p = 0.003)); and community-onset, HCF-associated – other HCF CDI (0.8 to 1.5 cases/1,000 admissions overall (p < 0.001)). For each CDI surveillance definition, there were significant differences in total incidence rates between institutions.

Conclusions

The increasing incidence rates of CDI over time and across institutions, and correlation of CDI incidence in different categories suggest that CDI may be a regional problem, and not isolated to single healthcare facilities.

Keywords: Clostridium difficile, surveillance, healthcare epidemiology, hospital-associated infections

INTRODUCTION

Despite widespread efforts to prevent CDI in healthcare facilities, recent studies from individual hospitals suggest that the incidence and severity of CDI is increasing in the U.S (1–5). Understanding recent trends in CDI incidence rates is essential to improve CDI surveillance and prevention efforts. However, comparisons of CDI incidence rates between institutions have been limited by the wide variability in case definitions of healthcare-associated CDI. Published studies have utilized definitions that differ on important details such as the duration of hospitalization prior to stool sample collection, the duration between previous hospital discharge and symptom onset, the definition of recurrent CDI cases, and the inclusion of CDI cases diagnosed in outpatients (2;6–8). Standardized surveillance definitions are necessary to provide the framework for meaningful comparisons among institutions and to better understand the incidence of CDI. The absence of standardized surveillance definitions has hindered accurate quantification of the national burden of CDI, as well as the consequent morbidity, mortality, and costs due to CDI. In addition, the lack of standardized surveillance definitions has negatively impacted CDI prevention efforts by making it difficult to identify targets for prevention efforts and to fully assess the impact of prevention efforts.

Prompted by recent changes in the epidemiology of CDI, an ad hoc C. difficile Surveillance Working Group was formed to develop recommendations and surveillance definitions based on existing literature and expert opinion (9). Despite publication in 2007 of these recommendations, which include five CDI surveillance definitions that incorporate recent healthcare facility exposures, there have not been any multicenter reports of CDI incidence trends using these definitions. The purpose of this study was to compare CDI incidence rates during a 6-year period among five geographically diverse academic medical centers across the United States using published recommended definitions incorporating recent healthcare facility exposures.

METHODS

This multicenter study was conducted at five geographically diverse academic medical centers in the United States. All hospitals participated in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Epicenters Program, including Barnes-Jewish Hospital (St. Louis, MO), Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA), The Ohio State University Medical Center (Columbus, OH), Stroger Hospital of Cook County (Chicago, IL), and University of Utah Hospital (Salt Lake City, UT). All patients ≥ 18 years of age admitted between July 2000 and June 2006 were included in the study. Electronic hospital databases were queried to collect data on comorbidities, C. difficile toxin assay results, total patient-days and dates of admission, discharge and assays. Chart review was performed for patients with a positive C. difficile toxin assay identified within 48 hours of admission to determine HCF exposures in the 90 days prior to hospital admission. HCF was defined as acute care, long-term care, long-term acute care, or other facility in which skilled nursing care was provided and patients were admitted at least overnight. Data from hospital B were excluded from the analysis from July 1, 2004 through June 30, 2006 due to a CDI pseudo-outbreak related to improper stool collection and transport methods (unpublished data). Data from hospital D were excluded from the analysis from July 1, 2000 through August 31, 2001 because toxin assay results were not available.

CDI Case Definitions

CDI cases were defined as any inpatient with a positive stool toxin assay for C. difficile. Recurrent cases were defined as repeated CDI episodes within eight weeks of each other and were excluded from the study. CDI cases were categorized into five surveillance definitions based on recent HCF exposure. 1) Hospital-onset, HCF-associated cases were defined as patients with symptom onset more than 48 hours after admission to the HCF. 2) Community-onset, HCF-associated – study hospital cases were defined as patients with symptom onset in the community or 48 hours or less after admission to an HCF, provided that symptom onset was less than 4 weeks after the last discharge from the study hospital and there were no exposures to other HCFs between the last discharge and most recent admission. 3) Community-onset, HCF-associated – other HCF cases were defined as patients with symptom onset in the community or 48 hours or less after admission to an HCF, provided that symptom onset was less than 4 weeks after the last discharge from an HCF other than the study hospital. 4) Community-onset, community-associated cases were defined as patients with symptom onset in the community or 48 hours or less after admission to an HCF, provided that symptom onset was more than 12 weeks after the last discharge from an HCF. 5) Indeterminate CDI cases were defined as patients who did not fit any of the above criteria for an exposure setting (e.g., a patient who has CDI symptom onset in the community but who was discharged from the same or another HCF 4–12 weeks before symptom onset).

Hospital onset CDI cases were attributed to the month of stool collection for the positive C. difficile toxin assay. Community-onset, HCF-associated – study hospital CDI cases were attributed to the month of discharge from the HCF before symptom onset. Community-onset, HCF-associated – other HCF and indeterminate CDI cases were attributed to the month of admission during the current hospitalization.

Calculation of CDI Rates

Annual CDI rates were calculated for five HCF exposure surveillance definitions, using denominators that were a modification of published surveillance definitions. The hospital-onset and the community-onset, HCF-associated – study hospital CDI rates were expressed per 10,000 patient-days because this denominator best reflected the per-day patient risk of C. difficile exposure at the study hospital. The remaining community-onset rates were expressed per 1,000 hospital admissions because this denominator best reflected the prevalence of CDI among the population admitted to the hospital. A denominator based on the metropolitan area would bias CDI rates since multiple hospitals, not a single hospital, serve the catchment area.

Since the community-onset, HCF-associated – study hospital CDI cases were attributed to the month of discharge from the HCF before symptom onset, community-onset, HCF-associated – study hospital CDI rates excluded the last month of the study period because we did not assess whether patients discharged during the last month of the study period presented to the study hospital with C. difficile after the study period.

Data Analysis

Patient characteristics were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test, the chi-square test for trend, and bivariate linear regression, as appropriate. CDI rates were evaluated with chi-square test for trend and chi-square summary tests. The Bonferroni correction was used to account for multiple testing. The correlation between annual rates of hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI and each community-onset CDI surveillance definition category was assessed via a Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) and Epi Info. Approval for this study was obtained from the human research protection offices of all participating centers.

RESULTS

During the six-year study period, the Prevention Epicenter hospitals identified 6,906 non-recurrent CDI cases, including 4,412 hospital-onset cases and 2,494 community-onset cases. The majority of community-onset cases (n=2,072 (83%)) were discharged from HCF less than 12 weeks before CDI symptom onset. These 2,072 CDI cases were classified as follows: 697 (34%) community-onset, HCF-associated – study hospital CDI, 1,048 (51%) community-onset, HCF-associated – other HCF CDI, and 327 (16%) indeterminate CDI. Seventeen percent (n=422) of the 2,494 community-onset cases did not have any inpatient HCF exposures within 12 weeks of their current hospital admission date, and were therefore classified as community-onset, community-associated CDI (Table 1).

Table 1.

Incidence rates of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) for 2000–2006, according to five CDI surveillance definitions based on recent healthcare facility (HCF) exposure.

| Hospital | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | A | B** | C | D** | E | Total |

| Hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI | ||||||

| No. of cases | 2467 | 383 | 552 | 425 | 585 | 4,412 |

| Rate per 10,000 patient-days | 15.5 | 11.1 | 4.0 | 6.3 | 4.6 | 8.4 |

| Community-onset, HCF-associated - study hospital CDI* | ||||||

| No. of cases | 421 | 31 | 77 | 53 | 115 | 697 |

| Rate per 10,000 patient-days | 2.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| Community-onset, HCF-associated - other HCF CDI | ||||||

| No. of cases | 667 | 24 | 187 | 40 | 130 | 1,048 |

| Rate per 1,000 admissions | 2.1 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| Community-onset, community-associated CDI | ||||||

| No. of cases | 203 | 67 | 21 | 78 | 53 | 422 |

| Rate per 1,000 admissions | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Indeterminate CDI | ||||||

| No. of cases | 170 | 36 | 45 | 25 | 51 | 327 |

| Rate per 1,000 admissions | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| No. of patient days | 1,594,249 | 346,648 | 1,390,063 | 676,253 | 1,268,875 | 5,476,405 |

| No. of admissions | 318,847 | 70,954 | 254,073 | 113,617 | 162,351 | 930,692 |

The last month of the study period was excluded from the analysis of CO/HCFA – study hospital CDI because patients discharged during the last month of the study period were not followed-up for hospital readmissions with CDI after the study period.

Data from hospital B from July 1, 2004 through June 30, 2006 and from hospital D from July 1, 2000 through August 31, 2001 were excluded.

Table 2 presents selected patient characteristics by CDI surveillance definition for all hospitals combined. Hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI cases were significantly older than community-onset, HCF-associated – study hospital CDI cases; community-onset, community-associated CDI cases; and indeterminate CDI cases. Hospital-onset, HCF-associated cases were younger than community-onset, HCF-associated – other HCF CDI cases (61.6 years vs. 72.7 years, p < 0.001). There were no significant changes in age among CDI cases over time, neither collectively nor within CDI surveillance definitions. Median hospital length of stay was significantly longer for hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI cases than community-onset CDI cases (p < 0.001 for all categories). Of 2,494 community-onset CDI cases, those discharged from an HCF less than 12 weeks before CDI symptom onset (i.e., community-onset, HCF-associated – study hospital CDI cases, community-onset, HCF-associated – other CDI cases, and indeterminate CDI cases) had significantly longer hospital length of stay compared to community-onset, community-associated CDI cases (median, 7 vs. 5 calendar days, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) cases, according to five CDI surveillance definitions based on recent healthcare facility (HCF) exposure.

| Variable | CDI Surveillance Definition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital- onset, HCF- associated (n = 4,412) |

Community- onset, HCF- associated – study hospital (n = 697) |

Community- onset, HCF- associated - other (n = 1,048) |

Community- onset, community- associated (n = 422) |

Indeterminate (n = 327) |

|

| Age, y | 61.6 (18–102) | 59.1 (18–103) | 72.7 (20–105) | 54.7 (19–97) | 58.1 (18–100) |

| Charlson score | 2 (0–14) | 2 (0–15) | 1 (0–14) | 1 (0–11) | 2 (0–11) |

| Hospital LOSa, days | 19 (3–436) | 6 (1–121) | 8 (1–152) | 5 (1–64) | 6 (2–128) |

| Time to positivity, days | 9 (3–383) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0–3) |

NOTE. Data are presented as median (range).

LOS for patients with community-onset CDI is the LOS for the hospitalization during which the patient was diagnosed with CDI.

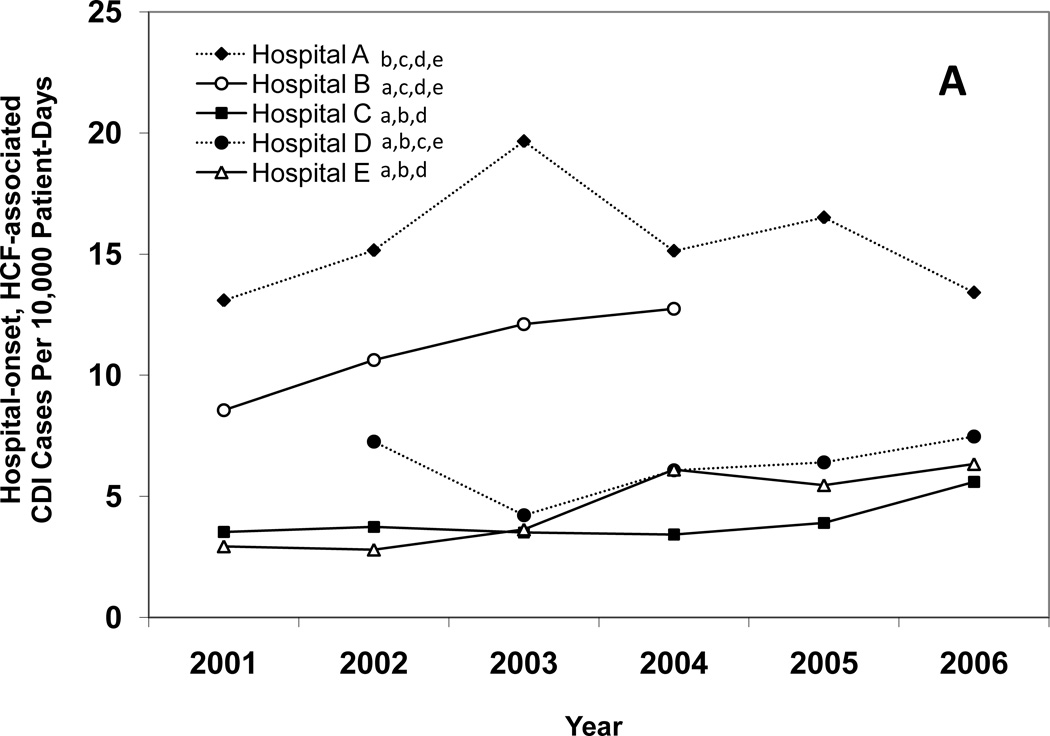

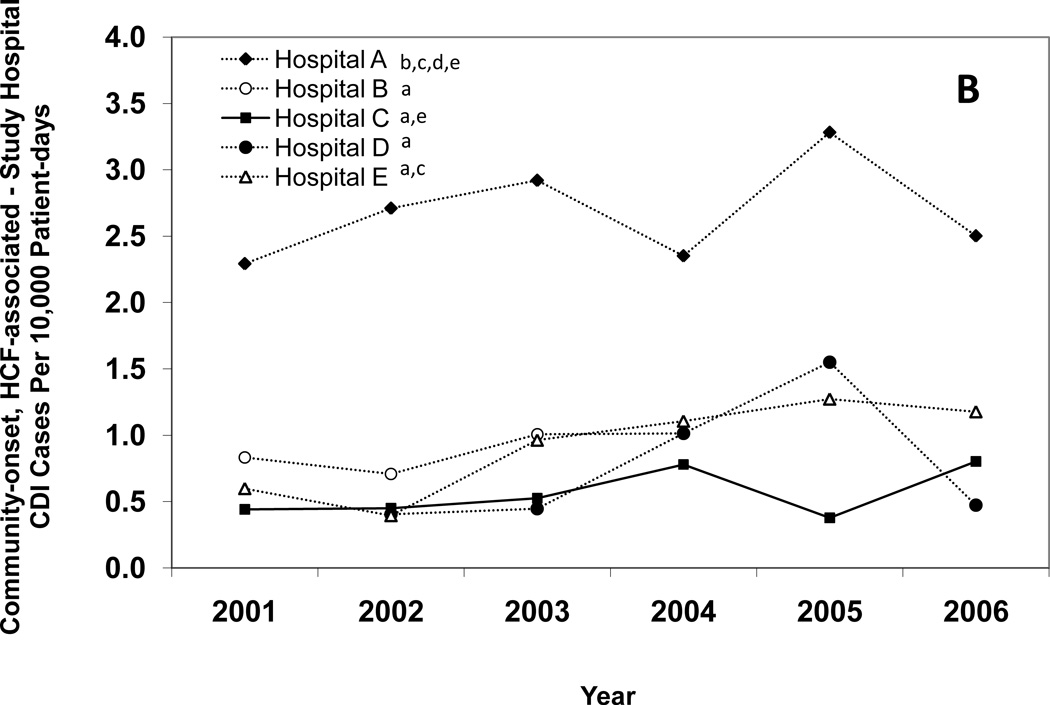

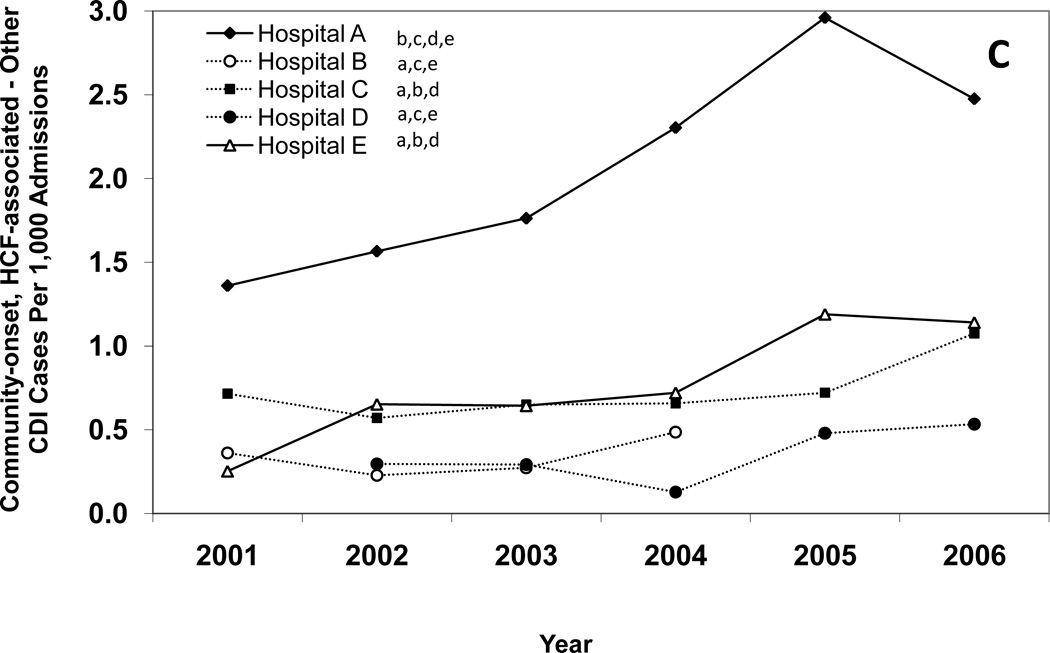

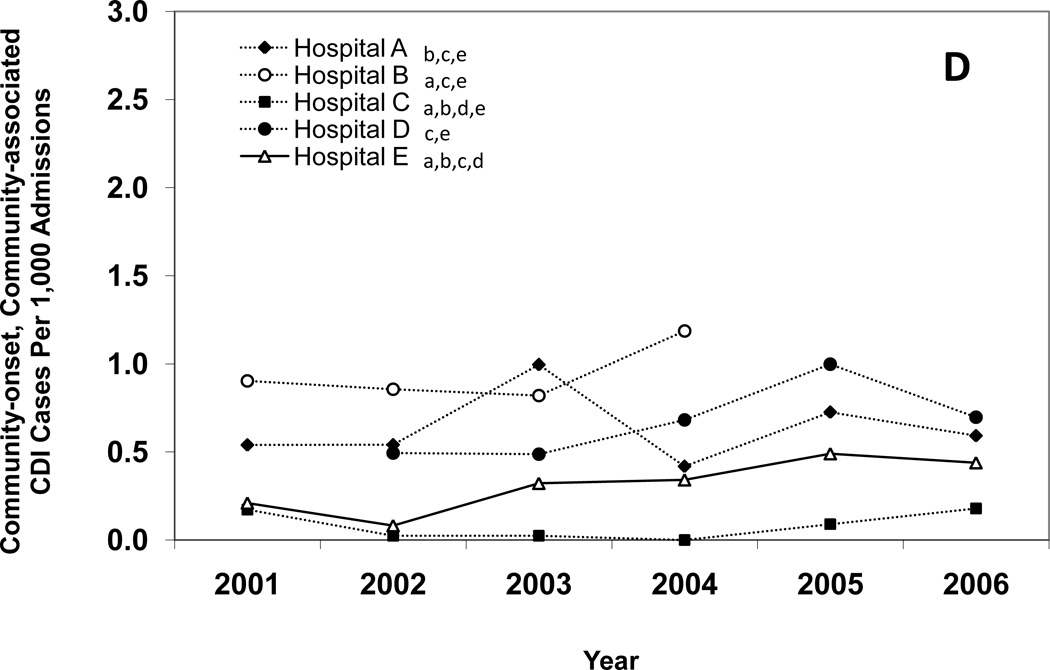

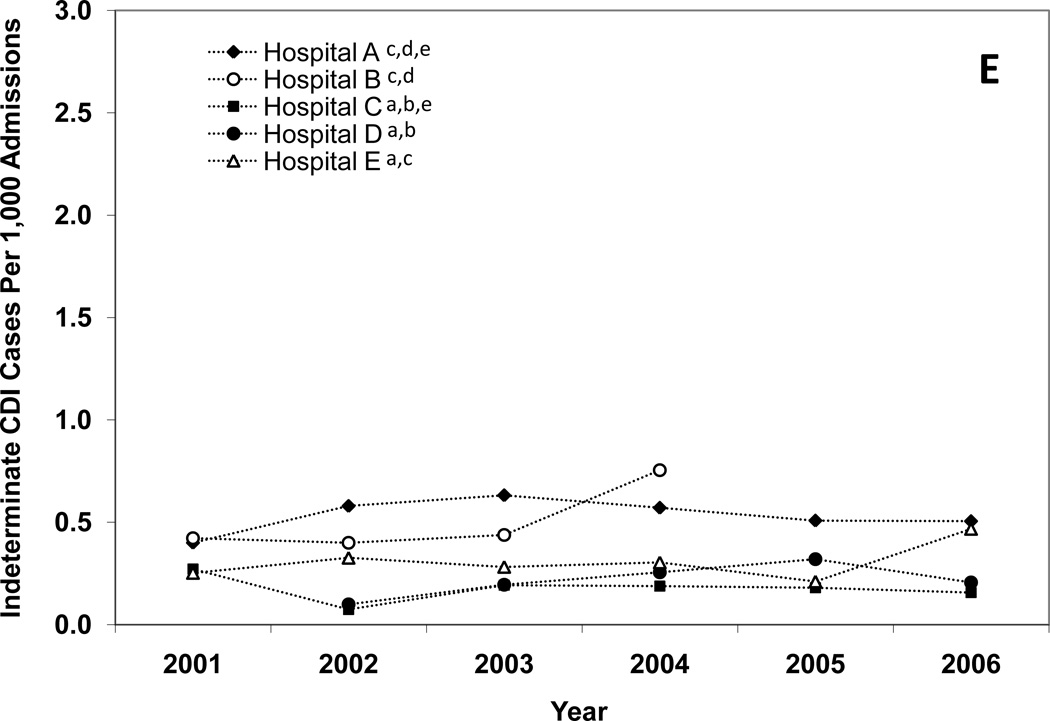

Figure 1 presents annual CDI incidence rates for all of the hospitals combined and Figures 2A–E provide hospital-specific data for each of the 5 surveillance definitions. Between 2000 and 2006, there were significant increases in the overall incidence of hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI; community-onset, HCF-associated – study hospital CDI; and community-onset, HCF-associated – other HCF CDI. The overall incidence of community-onset, community-associated CDI and indeterminate CDI remained stable over the study period. Overall, hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI increased by 21% from 7.0 to 8.5 cases/10,000 patient days (p < 0.001) (Figure 1). However, examination of Figure 1 indicates a possible upward trend in hospital-onset CDI from 2001 through 2003, but then a downward trend from 2003 through 2006. Addition analyses confirm a significant upward trend from 2001 through 2003 (p < 0.001), but no change in hospital-onset CDI was identified from 2003 through 2006 (p = 0.80). Hospitals B, C, and E had significant increases in hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI from 2000 to 2006 (p < 0.01 for all) (Figure 2A). There was no trend in hospital-onset CDI identified at hospital A across the entire study period (p = 0.94), but there was a significant increase from 2001 through 2003 (p < 0.001) and a significant decrease (p = 0.002) from 2003 through 2006. Overall, community-onset, HCF-associated CDI – study hospital CDI increased by 11% from 1.1 to 1.3 cases/10,000 patient-days (p = 0.003) (Figure 1), with a significant increase at hospital E only (p = 0.002) (Figure 2B). Community-onset, HCF-associated - other HCF CDI increased by 81% from 0.8 to 1.5 cases/1,000 admissions overall (p < 0.001) (Figure 1), with significant increases in incidence at hospitals A and E (p < 0.001 for both) (Figure 2C).

Figure 1.

Annual incidence rates of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) for all 5 hospitals combined, according to surveillance definition. Solid lines indicate a significant increase in incidence over the study period (χ2 test for trend p < 0.01). Open symbols, CDI cases per 10,000 patient-days; solid symbols, CDI cases per 1,000 admissions. HCF, healthcare facility.

Figure 2.

Annual incidence rates of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) for hospital-onset, healthcare facility (HCF)-associated CDI (A), community-onset, HCF-associated – study hospital CDI (B), community-onset, HCF-associated – other HCF (C), community-onset, community-associated CDI (D), and indeterminate CDI (E), according to hospital. Solid lines indicate a significant increase in incidence over the study period (χ2 test for trend p < 0.01). The lower-case letters next to the hospital name denote the hospitals with a significantly different overall CDI incidence rate (p < 0.005 for all). For example, hospital A had a significantly different overall hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI incidence rate than hospitals B, C, D, and E.

There were significant positive correlations between annual rates of hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI and community-onset, community-associated CDI (Pearson’s r = 0.659, p < 0.001), community-onset, HCF-associated -study hospital CDI (Pearson’s r = 0.849, p < 0.001), community-onset, HCF-associated – other HCF CDI (Pearson’s r = 0.657, p < .001), and CO/IND CDI (Pearson’s r = 0.813, p < .001).

For each CDI surveillance definition, there were significant differences in total incidence rates between institutions (Figure 2A–E). Hospital A had the highest incidence of CDI for each surveillance definition category, with the exceptions of community-onset, community-associated CDI and indeterminate CDI. Hospital C had the lowest incidence of CDI for each surveillance definition category, with the exception of community-onset, HCF-associated – other HCF CDI. Total hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI rates ranged from 4.0 cases/10,000 patient days at hospital C to 15.5 cases/10,000 patient days at hospital A (Table 1). There were significant differences in rates of hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI among all institutions, with the exception of hospital C versus hospital E (4.0 vs. 4.6 cases/10,000 patient-days) (Figure 2A). Total community-onset, community-associated CDI rates ranged from 0.1 cases/1,000 admissions at hospital C to 0.9 cases/1,000 admissions at hospital B (p <0.001) (Table 1), with non-significant differences between hospital A vs. hospital D (0.6 vs. 0.7 cases/1,000 admissions, p = 0.572) and hospital B vs. hospital D (0.9 vs. 0.7 cases/1,000 admissions, p = 0.055) (Figure 2D). Additional differences in total incidence rates among institutions are presented in Figure 2A–E.

DISCUSSION

This is the first multicenter study using recommended standardized surveillance definitions based on laboratory-confirmed CDI cases to identify increasing rates of CDI. The strengths of this study include data from five academic medical centers across the United States over a six-year span (2000–2006) and more than 959,000 hospitalizations. Medical chart review of CDI cases for detailed information on recent healthcare facility exposures allowed classification of both healthcare facility-associated and community-associated CDI using standardized surveillance definitions. Our surveillance data document the increasing incidence rates of the three most common types of CDI in our population: hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI, community-onset, HCF-associated - study hospital CDI and community-onset, HCF-associated - other HCF CDI. These CDI cases represented 89% of the CDI cases identified in our study population, and are consistent with several reports of increasing CDI rates in the U.S., including two national studies that analyzed the proportion of hospital discharges in which the patient received the ICD-9-CM discharge diagnosis code for CDI (8;10). Although statistically significant increases were not identified at all healthcare facilities and all surveillance categories, visual inspection of Figures 1 and 2 indicate there were no clear downward trends except for hospital-onset CDI from 2003 through 2006 at hospital A. Because of the high incidence of CDI, hospital A conducted numerous interventions to prevent CDI. The downward trend was significant (p = 0.002) and may reflect some success in these efforts. More notable is despite the downward trend at hospital A and hospital A accounting for over half of all hospital-onset CDI cases during the study period, overall there was still a significant increase in hospital-onset CDI incidence (p < 0.001) with no significant changes from 2003 through 2006 (p = 0.80). This study provides novel information because previous comparisons of CDI incidence rates among institutions were limited by differences in case definitions, lack of surveillance for community-onset CDI, and/or limited duration of surveillance (2;6–8).

The increasing incidence rate of hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI observed in our data differs from a 2005 Prevention Epicenter study, which did not detect any significant increases in healthcare facility-associated CDI rates between 2000 and 2003 at any of seven tertiary-care centers in the U.S. (6). The report by Sohn et al., which preceded the 2007 publication of standardized CDI surveillance definitions by the Ad Hoc C. difficile Surveillance Working Group, was limited by the absence of a standardized case definition. Each hospital used a unique case definition for healthcare-associated CDI, with variation in the duration of hospitalization prior to stool sample collection, the duration between previous hospital discharge and symptom onset, the definition of recurrent CDI cases, and the inclusion of CDI cases diagnosed in outpatients, limiting the ability to compare rates across hospitals. Based on their findings of a 30% difference in CDI rates when applying different case definitions used by the hospitals to a fixed data set, Sohn et al. recommended development of a more standardized CDI case definition.

Of two published multicenter studies using standardized surveillance definitions based on laboratory confirmed cases, neither study identified an increasing CDI incidence rate. Campbell et al. reported a downward trend in monthly healthcare-onset CDI rates in a statewide surveillance study using 2006 data collected as a result of active public reporting of healthcare-onset CDI mandated for all Ohio hospitals (n = 210) and nursing homes (n = 955) (7). Those results are contrary to the increasing incidence rate of hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI observed in our study, which may be partially attributable to the Ohio study’s exclusion of patients with CDI during the previous six months. The six-month interval during which a subsequent episode of CDI was considered to be a recurrent case rather than a new initial case was substantially longer than the 8 weeks specified by the more recently recommended CDI surveillance definitions, and likely underestimated CDI cases. Other potential explanations include potential seasonality of CDI incidence which was not identified because data were collected for only one year, or a true reduction in CDI incidence over the study period. Using data from 2005, Kutty et al. calculated monthly CDI rates according to the recommended CDI surveillance definitions, but did not evaluate trends over time (8). Unlike our study, which included data from a six-year study period, those studies only included one year of data. The short time period may explain the inability to detect an increasing trend of CDI incidence rates.

Our observations are consistent with existing evidence regarding significant variability in CDI incidence across HCF and the interdependence between CDI incidence within an HCF and CDI incidence in the surrounding area (8;11–14). In our multicenter study, the rank order of hospitals by CDI incidence rate was generally consistent across surveillance definition categories. For three of the five CDI surveillance definition categories, Hospital A had the highest CDI incidence rate. For four of the five CDI surveillance definition categories, Hospital C had the lowest CDI incidence. In addition, there were significant positive correlations between hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI rates and each category of community-onset CDI cases. Similarly, Kutty et al. reported a modest correlation (r = 0.63, P < 0.001) between monthly rates of hospital-onset, HCF-associated CDI cases and community-onset, HCF-associated CDI cases across six acute care hospitals in North Carolina (8). Campbell et al. reported positive correlations of Ohio healthcare-onset CDI rates between acute care hospitals and nursing homes in the same region for both initial cases (r = 0.22, P = 0.054) and recurrent cases (r = 0.29, P = 0.011) (7). An important explanation for the propagation of C. difficile within an HCF is thought to be newly admitted infected or asymptomatic patients who harbor the bacterium. These patients often have been recently discharged from a HCF (12). From an institution perspective, it is important to recognize the impact CDI incidence in the surrounding community has on the likelihood of a patient developing CDI after admission to the HCF. A high prevalence of CDI on admission may indicate more aggressive infection prevention and control measures are necessary to identify and isolate patients with CDI on admission to the HCF. These data also suggest the most successful measures to prevent CDI may require coordination amongst all healthcare facilities within a shared patient catchment area, rather than be centered around single institutions.

Our study has some limitations. There was incomplete ascertainment of demographic and clinical patient characteristics for the majority of non-cases in our study population. Demographic and clinical patient characteristics were only collected for CDI cases and a random subset of the non-cases (four per case), which precluded our ability to model CDI incidence rates adjusted for these variables. However, it is noteworthy that there were no significant changes in age or comorbidities (as measured by the Charlson score) over time among CDI cases, neither collectively nor within CDI surveillance definitions. Nor were there any changes in age or comorbidities in non-cases, and there was no correlation between CDI incidence and age or comorbidities in non-cases across HCF (data not shown). These findings suggest that the increasing incidence rates of CDI were not related to increasing age or changing severity of illness in the patient population over time or across HCF. Although there was a statistically significant increase in community-onset, HCF-associated CDI – study hospital, there may be concern the increase is not clinically significant. One of the primary reasons to conduct surveillance is to identify worrisome trends before they become clinically significant. This is part of the rationale for having standardized CDI surveillance definitions, to enable comparisons and pooling of like data to identify trends that may not otherwise be recognized in order to enhance prevention efforts before significant increases in morbidity and mortality occur. Another limitation of the study includes the potential for misclassification of the outcome. Our CDI rates are most likely an underestimate, because the surveillance strategy that we used was based on inpatient laboratory data that was available at each study hospital. CDI cases that were diagnosed and treated as inpatients at other healthcare facilities or solely in outpatient settings were not included. In addition, variability in the assays used to diagnose CDI and differences in CDI testing patterns between institutions and over the six-year study period may have contributed further to misclassification. Differences between the sensitivity and the specificity of the assays used at different healthcare facilities will impact the proportion of tests that will be positive, although the degree to which this may impact CDI rates is currently unknown. Lastly, this study only included data from academic medical centers. It is possible that differences in patient populations, patient care practices, and C. difficile testing patterns at other healthcare facilities may impact CDI rates.

The ideal definitions for CDI surveillance remain unknown. However, standardized surveillance definitions are necessary to track CDI over time and across facilities. This study demonstrated the importance of standardized CDI surveillance definitions. We were able to compare CDI rates over time and across institutions, and confirmed an increase in CDI over the study period. This study also provides additional evidence that CDI incidence may be a regional problem, and not isolated to single HCF. At a minimum, all hospitals should track hospital-onset, healthcare facility associated CDI to identify outbreaks at their facility (9;15). Community-onset CDI should also be tracked whenever resources are available, as tracking community-onset CDI may help identify an important source of C. difficile transmission within the healthcare facility. In addition, more study is need to further delineate the role newly admitted patients with CDI healthcare-onset CDI, the source of acquisition of C. difficile in patients with community-onset CDI, and whether regional CDI prevention measures are more effective than single institution-based CDI prevention efforts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (UR8/CCU715087-06/1 and 5U01C1000333 to Washington University, 5U01CI000344 to Eastern Massachusetts, 5U01CI000328 to The Ohio State University, 5U01CI000327 to Stroger Hospital of Cook County/Rush University Medical Center, and 5U01CI000334 to University of Utah) and the National Institutes of Health (K12RR02324901, K24AI06779401, K01AI065808 to Washington University). Findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest: E.R.D. has served as a consultant to Merck, Salix, and Becton-Dickinson and has received research funding from Viropharma. D.S.Y. has received research funding from Sage Products, Inc.

Footnotes

Preliminary data was presented in part at the 18th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, Orlando, FL (April 5–8, 2008), abstract 52.

Reference List

- 1.Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ, Sirio CA, Farkas LM, Lee KK, et al. Fulminant Clostridium difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications. Ann Surg. 2002;235(3):363–372. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gravel D, Miller M, Simor A, Taylor G, Gardam M, McGeer A, et al. Health care-associated Clostridium difficile infection in adults admitted to acute care hospitals in Canada: a Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(5):568–576. doi: 10.1086/596703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loo VG, Poirier L, Miller MA, Oughton M, Libman MD, Michaud S, et al. A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2442–2449. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A, Owens RC, Jr, Kazakova SV, Sambol SP, et al. An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2433–2441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonald LC, Owings M, Jernigan DB. Clostridium difficile infection in patients discharged from US short-stay hospitals, 1996–2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(3):409–415. doi: 10.3201/eid1203.051064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sohn S, Climo M, Diekema D, Fraser V, Herwaldt L, Marino S, et al. Varying rates of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea at prevention epicenter hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26(8):676–679. doi: 10.1086/502601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell RJ, Giljahn L, Machesky K, Cibulskas-White K, Lane LM, Porter K, et al. Clostridium difficile infection in Ohio hospitals and nursing homes during 2006. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(6):526–533. doi: 10.1086/597507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kutty PK, Benoit SR, Woods CW, Sena AC, Naggie S, Frederick J, et al. Assessment of Clostridium difficile-associated disease surveillance definitions, North Carolina, 2005. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(3):197–202. doi: 10.1086/528813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald LC, Coignard B, Dubberke E, Song X, Horan T, Kutty PK. Recommendations for surveillance of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(2):140–145. doi: 10.1086/511798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Kollef MH. Increase in adult Clostridium difficile-related hospitalizations and case-fatality rate, United States, 2000–2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(6):929–931. doi: 10.3201/eid1406.071447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belmares J, Johnson S, Parada JP, Olson MM, Clabots CR, Bettin KM, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Clostridium difficile over the course of 10 years in a tertiary care hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(8):1141–1147. doi: 10.1086/605638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clabots CR, Johnson S, Olson MM, Peterson LR, Gerding DN. Acquisition of Clostridium difficile by hospitalized patients: evidence for colonized new admissions as a source of infection. J Infect Dis. 1992;166(3):561–567. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubberke ER. The A, B, BI, and Cs of Clostridium difficile. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(8):1148–1152. doi: 10.1086/605639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samore MH, Bettin KM, DeGirolami PC, Clabots CR, Gerding DN, Karchmer AW. Wide diversity of Clostridium difficile types at a tertiary referral hospital. J Infect Dis. 1994;170(3):615–621. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubberke ER, Butler AM, Hota B, Khan YM, Mangino JE, Mayer J, et al. Multicenter study of the impact of community-onset Clostridium difficile infection on surveillance for C. difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(6):518–525. doi: 10.1086/597380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]