Abstract

Background

Testosterone therapy is increasingly promoted. No randomized placebo-controlled trial has been implemented to assess the effect of testosterone therapy on cardiovascular events, although very high levels of androgens are thought to promote cardiovascular disease.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted of placebo-controlled randomized trials of testosterone therapy among men lasting 12+ weeks reporting cardiovascular-related events. We searched PubMed through the end of 2012 using “(“testosterone” or “androgen”) and trial and (“random*”)” with the selection limited to studies of men in English, supplemented by a bibliographic search of the World Health Organization trial registry. Two reviewers independently searched, selected and assessed study quality with differences resolved by consensus. Two statisticians independently abstracted and analyzed data, using random or fixed effects models, as appropriate, with inverse variance weighting.

Results

Of 1,882 studies identified 27 trials were eligible including 2,994, mainly older, men who experienced 180 cardiovascular-related events. Testosterone therapy increased the risk of a cardiovascular-related event (odds ratio (OR) 1.54, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.09 to 2.18). The effect of testosterone therapy varied with source of funding (P-value for interaction 0.03), but not with baseline testosterone level (P-value for interaction 0.70). In trials not funded by the pharmaceutical industry the risk of a cardiovascular-related event on testosterone therapy was greater (OR 2.06, 95% CI 1.34 to 3.17) than in pharmaceutical industry funded trials (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.60).

Conclusions

The effects of testosterone on cardiovascular-related events varied with source of funding. Nevertheless, overall and particularly in trials not funded by the pharmaceutical industry, exogenous testosterone increased the risk of cardiovascular-related events, with corresponding implications for the use of testosterone therapy.

Keywords: Testosterone, Cardiovascular, Men, Trial

Background

In observational studies low serum testosterone is associated with cardiovascular disease [1,2]. Testosterone may protect or be a secondary risk marker of other processes [1-3]. On the precautionary principle, expert advice and reviews, largely based on observational evidence, warn that cardiovascular disease may be increased by androgen deprivation therapy [4] and low testosterone [5,6]. Awareness of low testosterone as a treatable condition is being raised [7,8]. Testosterone use is increasing [9-11], possibly as self-medication in response to advertising.

In 2004 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) reviewed the evidence on testosterone therapy and concluded, largely based on placebo-controlled trials, that ‘there is not clear evidence of benefit for any of the health outcomes examined’ [12]. The IOM recommended small-scale trials to establish the efficacy of testosterone therapy where other treatments were not available [12]. To our knowledge, no trial has been designed to assess the effect of testosterone therapy on cardiovascular morbidity or mortality. Previous meta-analyses of randomized placebo-controlled trials found that testosterone therapy resulted in a non-significantly higher risk of cardiovascular events, based on adverse events, but only included trials through March 2005 [13,14]. A more recent meta-analysis included trials through August 2008 but only reported on three specific cardiovascular outcomes, that is, arrhythmia, coronary bypass surgery and myocardial infarction [15]. Given the widespread use of testosterone, the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease in older men and no comprehensive assessment of the effect of testosterone therapy on cardiovascular events, an up-to-date meta-analysis may help inform clinical practice. We carried out a meta-analysis of adverse events from randomized placebo-controlled trials to examine the overall risk of cardiovascular-related events associated with testosterone therapy.

Methods

This meta-analysis follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [see Additional file 1] and a published protocol (CRD42011001815) [16]. Two reviewers (LX and CMS) independently searched for and selected trials, resolving any differences by consensus. Two statisticians (GF and BJC) extracted information from the selected trials.

Data sources and searches

We (LX and CMS) systematically searched PubMed until 31st December 2012 using “(“testosterone” or “androgen”) and (random*) and trial” with the selection limited to studies in men in English, because a preliminary search only found studies in English. We (LX and CMS) searched the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform for any trial using testosterone as an intervention. From this search, we (LX and CMS) discarded any studies both agreed were irrelevant based on title or abstract and read the remaining. We did a bibliographic search of the selected trials and relevant reviews.

Study selection

We included randomized placebo-controlled trials giving cardiovascular-related events by study arm, because a report may focus on a particular aspect of the trial [17,18] and not report all events that have occurred [17-19]. We excluded trials that only gave treatment-related events in the testosterone arm because these might not include full reporting of events in the placebo arm. Initially, we intended to exclude trials that only reported withdrawals as potentially less comprehensive than reporting of adverse events [18,19], however this turned out to be a very fine distinction, so we included any trial reporting cardiovascular-related events by study arm.

We included any randomized controlled trial (RCT) of testosterone, but not other androgens, compared with placebo, including a comparison against a background of other treatments, because men likely to be taking testosterone may also be in treatment for other conditions. We excluded trials of less than twelve weeks’ duration to assess long-term rather than acute effects of testosterone therapy.

We checked for duplication based on overlapping authorship, study description, number of participants and participant characteristics. When duplication occurred we used the study with the most comprehensive description of adverse events.

Outcome

The primary outcome was composite cardiovascular-related events; because we anticipated too few events for robust assessment by cardiovascular event type; and a system-wide composite outcome may be most suitable for adverse events [20]. Cardiovascular-related events were defined as anything reported as such by the authors, that is, events reported as cardiac disorders, cardiovascular complaints, cardiovascular events, vascular disorders, cardiac or cardiovascular, or where the event description fell within the International Statistical Classification of Disease (ICD) version 10 chapter IX (I00 to I99). Most trials only reported serious adverse events, but a few also reported a wider range of events, so we also examined the effect of testosterone therapy by seriousness. Seriousness was based on the US Department of Agriculture definition of serious adverse events and the type of cardiovascular event generally considered serious [21]. Serious cardiovascular events were defined as cardiovascular-related events which the authors described as serious adverse events or where the outcome was death, life-threatening, hospitalization, involved permanent damage or required medical/surgical intervention, or was one of the following types of cardiovascular event: myocardial infarction, unstable angina, coronary revascularization, coronary artery disease, arrhythmias, transient ischemic attacks, stroke or congestive heart failure but not deep vein thrombosis.

Data extraction and quality assessment

A statistician (GF) extracted the number of participants randomized and cardiovascular-related events by trial arm. Event classification was checked by a physician (LX). A second statistician (BJC) checked the information extracted. Where trials reported cardiovascular-related events without giving the study arm, we contacted the authors twice by email to ask for cardiovascular-related events by study arm.

The reviewers (LX and CMS) independently used an established tool to evaluate the quality of each trial [22], focusing on the quality of reporting of cardiovascular-related adverse events. First, we reported whether cardiovascular-related events were individually listed in a table by study arm, because these are easier to identify unambiguously. Second, we reported whether the type and severity of cardiovascular-related events reported was either pre-specified or identified before the allocation was revealed, because issues have been expressed about the reporting of adverse events [23,24]. Cardiovascular-related events vary in severity making the selection criteria and categorization crucial to an outcome assessed from adverse events.

Sensitivity analysis

We initially planned only to assess whether the effects of testosterone on cardiovascular-related events varied with average baseline testosterone, because we did not expect sufficient trials for sub-group analysis by type of testosterone product or by type of cardiovascular-related event. However, the reporting of adverse events may be open to interpretation [23], and may not be comprehensive [25]. Given potential lack of clarity as to the selection of the cardiovascular-related adverse events reported, we also examined whether the effect of testosterone therapy varied with funding source. Finally, we also considered cardiovascular-related death as an outcome.

Data synthesis and analysis

We used the number of participants randomized as the denominator and included all cardiovascular-related events from the start. We used funnel plots and ‘trim and fill’ to assess publication bias, that is, missing trials. We used I2 to assess heterogeneity between trials, using fixed effects models where there was low heterogeneity (I2 <30%), otherwise using random effects models. We obtained the pooled odds ratio, using the ‘metabin’ function of the ‘meta’ package in R 2.14.1 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria). We used meta-analysis regression, with inverse variance weighting, to assess whether the effects of testosterone therapy varied with baseline testosterone or funding source, using the ‘rma’ function of the ‘metafor’ package in R 2.14.1. Initial analysis showed the pooled odds ratio was similar using a Peto or a Mantel-Haenszel estimate; we used inverse variance weighting for consistency with the meta-regression.

This study is an analysis of published data, which does not require ethics committee approval.

Results

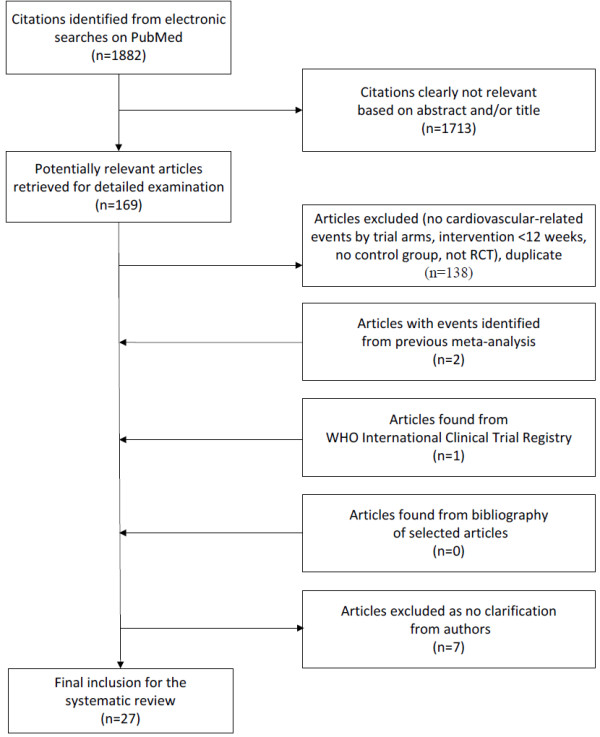

The initial search yielded 1,882 papers, of which 169 were selected for full text scrutiny. Of these 169 papers, 31 concerned different placebo-controlled randomized trials among men of testosterone therapy of 12+ weeks reporting cardiovascular-related events by study arm. We found one additional recent trial from the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform [26]. We did not find any additional such trials from a bibliographic search of these 32 papers or from eight reviews [27-34]. Two additional trials [35,36] selected for full text scrutiny had cardiovascular-related events shown in a plot from one previous meta-analysis [13], but not the other meta-analyses [14,15] or in the relevant publications [35-37]. The search did not find one small non-randomized trial [38] included in two previous meta-analyses [13,15]. The search found one additional trial [39] potentially relevant to the earlier meta-analyses [13,14], two additional trials [40,41] potentially relevant to the most recent meta-analysis [15] and 11 subsequent trials. We sought clarification concerning events by study arm for 10 trials as set out in Additional file 2. Six authors never responded [37,40,42-45], three responded but did not provide any relevant information [36,46,47] and one provided information [48]. We included this later trial [48], one of the others that gave cardiovascular deaths, but not other cardiovascular-related events, by study arm [46] and one that gave vascular events, but not all cardiovascular-related events by study arm [44]. Figure 1 shows the search strategy resulting in 27 placebo-controlled randomized trials.

Figure 1.

Selection process for the placebo-controlled randomized trials of the effects of testosterone therapy on cardiovascular-related events.

Table 1 shows the 27 trials over 25 years of 2,994 mostly middle-aged or older men (1,733 testosterone and 1,261 placebo) with low testosterone and/or chronic diseases, who experienced 180 cardiovascular-related events. Most of the trials were in Western settings. Thirteen trials were supported by the pharmaceutical industry. Two trials were stopped early [49,50], one because of adverse events among the men allocated to testosterone [50] and one because ‘it would not be feasible to demonstrate - in the foreseeable future - a beneficial effect of testosterone [on mortality] by continuing the study’ [49].

Table 1.

Characteristics of placebo-controlled randomized trials giving the effects of testosterone therapy on cardiovascular-related events among men

|

Author and publication year |

Study |

Participants |

Industry funding |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setting | Duration | Dose | Cardiovascular-related events based on | Age range | Number | Health status | Initial T (nmol/L) | ||

| Copenhagen Study Group

[49] 1986 |

Denmark |

About 16 monthsa |

200 mg/8 h micronized T, PO |

Deaths |

24 to 79 |

221 |

alcoholic cirrhosis |

about 20 |

None given |

| Marin

[39] 1993 |

Denmark |

9 months |

T gel 125 mg/day |

Withdrawals |

40 to 65 |

21 |

Obese, low T |

15.3 |

Funded by Besins Iscovesco |

| Hall

[51] 1996 |

UK |

9 months |

T enanthate 250 mg /month, IM |

Withdrawals |

34 to 79 |

35 |

Rheumatoid arthritis |

16.1 |

Funded by Schering Healthcare |

| Sih

[52] 1997 |

US |

12 weeks |

T cypionate IM every 14 to 17 days |

Withdrawals |

51 to 79 |

32 |

T<60 ng/dl |

9.2 |

None given |

| English

[53] 2000 |

UK |

12 weeks |

Transdermal T 5 mg/day |

Withdrawals and safety data |

Mean 62 |

50 |

Coronary artery disease |

12.9 |

Patches given by Smith Kline Beecham |

| Snyder

[19] 2001 |

US |

36 months |

Transdermal T 6 mg/day |

Clinically apparent from hospital records |

65+ |

108 |

Men with T one SD <475 ng/dl |

12.7 |

Patches given by ALZA Corporation |

| Amory

[54] 2004 |

US |

36 months |

T enanthate 200 mg/2 weeks, IM |

Serious adverse cardiovascular events |

65 to 83 |

48 |

TT <350 ng/dl |

10 |

None given |

| Kenny

[55] 2004 |

US |

12 weeks |

T enanthate 200 mg/3 weeks, IM |

General description |

73 to 87 |

11 |

Cognitive decline, bioavailable T <128 ng/dl |

14.1 |

None |

| Svartberg

[56] 2004 |

Norway |

26 weeks |

T enanthate 250 mg/month, IM |

General description |

Mean 66 |

29 |

COPD |

21.1 |

None |

| Brockenbrough

[57] 2006 |

US |

6 months |

Transdermal T gel 10 g/day |

Side effects and adverse events |

Mean 56 |

40 |

Dialysis and TT <300 ng/dl |

7.3 |

Supported by Auxilium Pharmaceuticals |

| Malkin

[58] 2006 |

UK |

12 months |

Transdermal T patch 5 mg/day |

Serious adverse events |

Mean 64 |

76 |

Heart failure |

13.0 |

Medication given by Watson Pharmaceuticals |

| Merza

[59] 2006 |

UK |

6 months |

Transdermal T patch 5 mg/day |

Withdrawals |

40+ |

39 |

TT <10 nmol/L |

8.0 |

Supported by Ferring Pharmaceuticals Ltd |

| Nair

[60] 2006 |

US |

24 months |

Transdermal T patch 5 mg/day |

Adverse events |

60+ |

62 |

DHEA<1.57 μg/ml, bioavailable T <103 ng/dl |

13.7 |

Supported by The Endocrine Society |

| Emmelot-Vonk

[61] 2008 |

Netherlands |

6 months |

TU 160 mg/day, PO |

Adverse events |

60 to 80 |

237 |

TT<13.7 nmol/L |

10.7 |

Medication given by Organon NV |

| Svartberg

[41] 2008 |

Norway |

52 weeks |

TU 1000 mg, MI at 0, 6, 16, 28 and 40 weeks |

Deaths |

60 to 80 |

38 |

TT≤11.0 nmol/L |

8.3 |

Grant from Bayer Schering Pharma AG |

| Caminiti

[62] 2009 |

Italy |

12 weeks |

TU 1000 mg MI for 0, 6 and 12 weeks |

General description of events |

66 to 76 |

70 |

Heart failure |

7.0 |

None given |

| Chapman

[48] 2009 |

Australia |

1 year |

TU 80 mg orally twice a day |

Hospitalizations |

65+ |

23 |

Undernourished |

18.8 |

Organon provided funding |

| Legros

[46] 2009 |

Europe |

1 year |

TU 80, 160 and 240 mg orally per day |

Safety assessments |

50+ |

316 |

Free T<0.26 nmol/L |

12.8 |

Funded by Schering-Plough |

| Aversa

[63] 2010 |

Italy |

24 months |

TU 1,000 mg (every 12 weeks) |

Safety aspects |

45 to 65 |

50 |

MS and/or T2DM TT<3.0 ng/ml |

8.5 |

None given |

| Basaria

[50] 2010 |

US |

About 6 monthsa |

Transdermal T gel 100 mg/day |

Cardiovascular-related events |

65+ |

209 |

Frial, TT 100 to 350 ng/dl |

8.4 |

Medication given by Auxilium Pharmaceuticals |

| Srinivas-Shankar

[64] 2010 |

US |

6 months |

Transdermal T gel 50 mg/day |

Serious adverse events and withdrawals |

65+ |

274 |

TT≤12 nmol/L (345 ng/dl) |

11.0 |

Supported by Bayer Schering Pharma |

| Jones

[65] 2011 |

Europe |

12 months |

T gel 60 mg/day |

Cardiovascular events |

37 to 88 |

220 |

Hypogonadal with type 2 diabetes and/or MetS, |

9.4 |

Supported by ProStrakan |

| Ho 2011

[66] |

Malaysia |

1 year |

TU 1000 mg MI for 0, 6, 18, 30 and 42 weeks |

Withdrawals |

40+ |

120 |

T<12 nmol/L, |

9.0 |

Supported by Bayer Schering Pharma |

| Kaufman

[44] 2011 |

US |

182 days |

1.62% T gel 2.5 mg/day |

Safety aspects |

45 to 64 |

274 |

Hypogonadal, T<300 ng/dl |

9.8 |

Funded by Abbott. |

| Kalinchenko

[67] 2010 |

Russia |

30 weeks |

TU 1,000 mg MI for 0, 6, 18 and 30 weeks |

Withdrawal |

35 to 70 |

184 |

T<350 ng/dl |

7.0 |

Supported by Bayer Schering Pharma |

| Hoyos

[68] 2012 |

Australia |

18 weeks |

TU 1000 mg MI at 0, 6 and 12 weeks |

Adverse events |

18+, mean 49 |

67 |

Obese men with obstructive sleep apnea |

13.3 |

Supported by Bayer Schering Pharma |

| Spitzer [26] 2012 | US | 14 weeks | 1% T gel 10 g/day | Adverse events | 40 to 70 | 140 | Erectile dysfunction low T and a sexual partner | 12.3 | none |

atrial stopped early so duration varies. IM= intramuscularly; P, placebo; PO, orally; T= testosterone; TT= total testosterone; TU= testosterone undecanoate.

Quality assessment

The quality assessment (see Additional file 3) shows that two trials provided a table with a comprehensive list of cardiovascular-related events by study arm and eight trials provided a summary table of cardiovascular-related events by study arm. For 17 trials cardiovascular-related events were surmised from withdrawals and/or adverse events as given in Additional file 4, including one where the cardiovascular-related events were surmised from a P-value [65]. The type and severity of adverse events to be reported was pre-specified in one trial [61]. In the two trials terminated early the adverse events motivated termination and were identified before treatment allocation was known [49,50]. Otherwise it was sometimes unclear whether the definition or classification was made by masked assessors.

Data synthesis

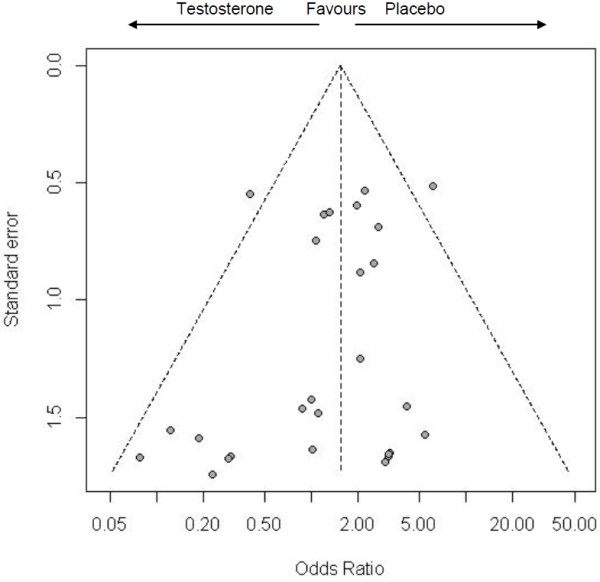

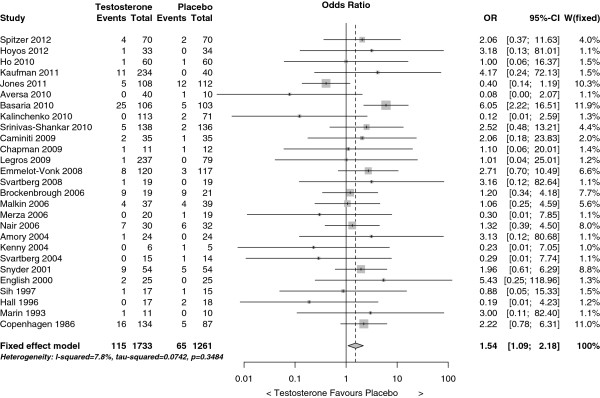

The funnel plot (Figure 2) shows several small studies (on the left hand side) where testosterone reduced cardiovascular-related events, however, there were no similar small studies where testosterone increased cardiovascular-related events. The forest plot (Figure 3) shows that the trials were homogeneous (I2 = 7.8%). Testosterone increased the risk of a cardiovascular-related event in a fixed effect model, odds ratio (OR) 1.54, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.09 to 2.18. Trim and fill revised the OR to 1.69 (95% CI 1.21 to 2.38). When the analysis was restricted to serious events, whose categorization is shown in Additional file 4, the estimate was very similar (OR 1.61 (95% CI 1.01 to 2.56)) and was revised to 2.01 (95% CI 1.30 to 3.14) by trim and fill.

Figure 2.

Funnel plot of placebo-controlled randomized trials examining the effects of testosterone therapy on cardiovascular-related events.

Figure 3.

Forest plots of placebo-controlled randomized trials examining the pooled effect of testosterone therapy on cardiovascular-related events.

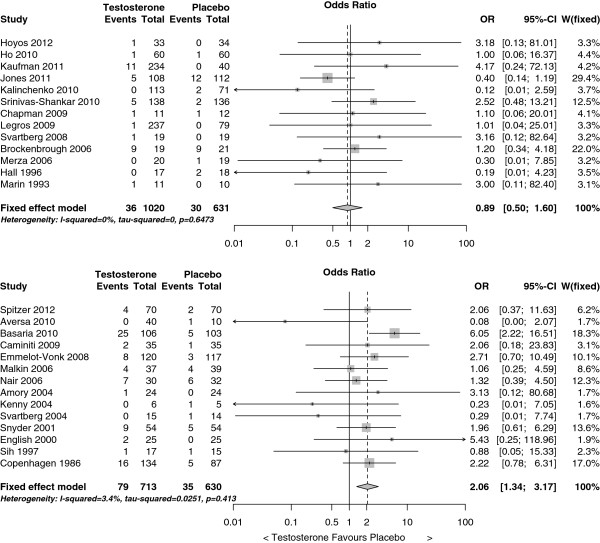

Sensitivity analysis

The cardiovascular-related event rate was lower in trials funded by the pharmaceutical industry (4% (66/1,651)) than in other trials (8% (114/1,343)). In a meta-regression model, risk of cardiovascular-related events on testosterone therapy varied with the source of funding (P-value for interaction 0.03) but not with baseline testosterone (P-value for interaction 0.70). In trials funded by the pharmaceutical industry testosterone had no effect on cardiovascular-related events, but in the other trials testosterone therapy substantially increased the risk of a cardiovascular-related event (Figure 4). Finally, 33 cardiovascular-related deaths were identified (22 testosterone arm and 11 placebo arm), for which the odds ratio was similar 1.42 (95% CI 0.70 to 2.89) to the estimate for all cardiovascular-related events, and was revised to 1.57 (95% CI 0.78 to 3.13) by trim and fill.

Figure 4.

Forest plots of placebo-controlled randomized trials examining the pooled effects of testosterone therapy on cardiovascular-related events by source of funding: upper panel funded by the pharmaceutical industry and lower panel not funded by the pharmaceutical industry.

Discussion

This updated meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials, with a much larger number of participants than previous meta-analyses [13-15], adds to the previous findings by showing that testosterone therapy increases cardiovascular-related events among men. The risk of testosterone therapy was particularly marked in trials not funded by the pharmaceutical industry. The risks of cardiovascular-related events were similar by baseline testosterone.

Several possible explanations exist for our findings. First, not all trials of testosterone therapy reported all cardiovascular-related events by study arm [36,46]. Trials favoring testosterone may be unpublished. However, the funnel plot (Figure 2) and ‘trim and fill’ suggested trials favoring the placebo may be missing. Second, endogenous and exogenous testosterone may have different effects, with endogenous testosterone being protective, consistent with the observational evidence [1,2] and with testosterone declining with age when cardiovascular disease increases with age. However, a recent Mendelian randomization study, using genetic variants as an instrumental variable for endogenous testosterone, did not corroborate protective effects of endogenous testosterone on cardiovascular disease risk factors [69]. Another possibility is that serum testosterone is not a good indicator of androgen activity [70], as has long been suggested [71] and recently substantiated by the effective use of anti-androgens in prostate cancer at castrate levels of serum testosterone [72,73]. Third, endogenous testosterone may be beneficial, but other metabolites of exogenous testosterone, raised by testosterone therapy, such as estrogens or dihydrotestosterone, could mediate cardiovascular-related events. Exogenous estrogens do not protect men against cardiovascular disease [74]. However, higher free testosterone rather than higher estradiol appeared to mediate the cardiovascular events in a recent trial of testosterone therapy [75]. Few trials have examined the effects of dihydrotestosterone administration and have usually focused on prostate rather than cardiovascular effects [76-78]. The interplay of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone is complex and challenging to disentangle in RCTs [79]. Nevertheless, exogenous testosterone lowers HDL-cholesterol [15] and raises hemoglobin, hematocrit and thromboxane [15,80], all of which might contribute to cardiovascular disease. Thromboxane promotes clotting and blood vessel constriction. Natural experiments suggest that lower lifetime endogenous androgens are associated with a relatively lower risk of death from ischemic heart disease, based on legally castrated men [81] and men with Klinefelter’s syndrome [82]. Similarly, a meta-analysis of RCTs of androgen deprivation therapy found a non-significantly lower risk of cardiovascular mortality among men allocated to androgen deprivation [83], despite bias to the null by the competing risk of death from prostate cancer.

Our findings are consistent with the three previous meta-analyses [13-15], which all indicated a non-significantly higher risk of testosterone therapy for a composite cardiovascular outcome of the events considered, despite discrepancies in some studies [13,14]. This meta-analysis based on many more trials (27), many more men (2,994) and correspondingly more events (180) produced a similar, but more precise estimate, with the confidence interval no longer including no effect. The difference between the estimates by funding source is consistent with other observations [84,85] and could be due to different reporting of adverse events in industry funded trials. Differences by funding source could also be due to differences between trials. Industry funded trials reported fewer cardiovascular-related events, which reduces power although it should not affect the direction of effect. Industry funded trials tended to be in younger men. It is possible, although unusual, for the effects of treatment to be ‘crossed’ by age [86].

From a clinical perspective the issue is ensuring that the benefits of testosterone therapy outweigh the potential risks. Almost a decade after the IOM’s report [12] the efficacy of testosterone therapy for health outcomes where treatments are not already available remains uncertain. Testosterone compared to placebo could be beneficial for glucose metabolism [65], depression [87,88], sexual dysfunction [26,89], bone density [90] and HIV wasting syndrome [91,92], although whether testosterone is better than established treatments for these conditions has not been clearly established. Cardiovascular disease is common in typical users of testosterone therapy, that is, older men. The 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event for US men aged 65 to 69 years is about 28% [93]. Assuming the increased risk of cardiovascular-related events seen here with testosterone therapy would give a number needed to harm of at most 90 per year of testosterone therapy. As such, further research might focus on obtaining evidence without interventions, for example by confirming that the observed negative associations of serum testosterone with specific cardiovascular diseases extends to other androgen biomarkers, such as androgen glucuronides [94], and to other study designs less open to biases, such as Mendelian randomization. Moreover, a gene in the steroidogenesis pathway (CYP17A1) is reliably associated with coronary artery disease [95]. Establishing if CYP17A1 acts, if at all, by raising or lowering androgens would also bring clarity. Finally, consideration could be given to whether further trials should be of agents that raise or lower testosterone.

Strengths and limitations

Despite providing a meta-analysis of all known placebo-controlled randomized trials, limitations exist. First, the reporting of adverse events may be open to conflicts of interest [24]. The funnel plot and analysis by funding source are consistent with that possibility. A very large market is at stake [9]. Second, in a trial of a therapy, such as testosterone, which may change how men feel or their sex drive, some accidental unmasking may have occurred. Few trials assessed or reported this possibility. Third, some men in the testosterone arm stopped treatment because of increased prostate specific antigen or polycythemia, which would bias towards the null. Fourth, RCTs are not always tagged as such and could be missed [96]. However, we searched broadly and found several potentially eligible trials that had not been included in previous meta-analyses. Fifth, our study cannot include on-going trials, such as the Testosterone Supplementation and Exercise in Elderly Men trial (NCT00112151) and The Testosterone Trial (NCT00799617). However, these trials are not designed to assess the effect of testosterone on cardiovascular events and will take time to complete. If new trials show testosterone therapy to be strongly protective against cardiovascular disease, it would be against the general run of evidence to date making interpretation uncertain because of heterogeneity [97]. Sixth, the abstractors were not blinded. Seventh, most trials only reported fairly serious cardiovascular-related events, but the severity varied between trials, although for RCTs the reporting of events should be comparable within trials, and the events reported are more or less severe symptoms of cardiovascular disease on the pathway to cardiovascular mortality. An analysis restricted to events which could be identified as serious gave a similar estimate, but was limited by relying on events the authors had chosen to describe in detail by study arm and was revised upwards by trim and fill. Arguably, the standard definitions of event seriousness, including hospitalization, do not apply to frail older men, because they may be particularly prone to hospitalization. On the other hand, frail older people may also be most affected by any decrement to their already poor health, so hospitalization may represent a particularly significant event. Notably, an estimate based solely on deaths also had a similar point estimate, although the confidence interval included no effect because of low power. Eighth, two larger trials were terminated early [49,50] which reduces power and could affect the estimates. However, the terminations took place towards the end of the planned trials and did not specifically concern cardiovascular-related events. Nevertheless, early terminations may have slightly increased the estimate and widened the confidence intervals. However, the interpretation would, most likely, have been similar. Ninth, although meta-analyses are a mainstay of evidence-based medicine they may be less reliable than large RCTs. Meta-analysis may overstate the benefits of treatment [98] however, they are less prone to overstate the harms [98]. Subsequent large RCTs rarely reverse the direction of effect from meta-analysis [99]. Tenth, given the lack of detailed cardiovascular-event reporting secondary analysis by type of cardiovascular event was not possible. Such sub-group analysis would undoubtedly be etiologically valuable. However, from a public health perspective the issue is identifying side-effects, where a composite outcome relating to a particular system (here the cardiovascular system) has been recommended [20]. Finally, the difference observed by source of funding could just be chance variation; however, testosterone therapy increased the risk of cardiovascular-related events overall.

Conclusions

Appropriately prescribed testosterone is undoubtedly beneficial. However, caution needs to be exercised to ensure that the associated health benefits of testosterone therapy outweigh the potential increased risk of cardiovascular-related events, particularly in older men where cardiovascular disease is common.

Abbreviations

CI: confidence interval; CYP17A1: cytochrome P450 17A1; IOM: Institute of Medicine; ICD: International Statistical Classification of Disease; OR: odds ratio; PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; RCT: randomized controlled trial; WHO: World Health Organization.

Systematic review reference number CRD42011001815.

Competing interests

All authors declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; BJC has received research funding from MedImmune Inc., and consults for Crucell MV; no other relationships or activities exist that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Authors’ contributions

LX carried out the systematic search and drafted the manuscript. GF and BJC did the data extraction and analysis; they also reviewed the manuscript critically. CMS originated the idea, carried out the systematic search and helped draft the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. LX is the guarantor. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Trials where authors contacted for additional information and responses.[13,35-37,40,42-48,100].

Quality assessment of the selected placebo-controlled RCTs of the effects of testosterone therapy on cardiovascular-related events (CRE) [19],[26],[39],[41],[44],[46],[48]-[68].

Description of cardiovascular-related events in the selected placebo-controlled RCTs [19],[26],[39],[41],[44],[46],[48]-[67],[101].

Contributor Information

Lin Xu, Email: linxu@hku.hk.

Guy Freeman, Email: gfreeman@hku.hk.

Benjamin J Cowling, Email: bcowling@hku.hk.

C Mary Schooling, Email: mschooli@hunter.cuny.edu.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steffie Woolhandler, David Himmelstein and Heidi Jones for their support.

References

- Araujo AB, Dixon JM, Suarez EA, Murad MH, Guey LT, Wittert GA. Clinical review: endogenous testosterone and mortality in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3007–3019. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruige JB, Mahmoud AM, De Bacquer D, Kaufman JM. Endogenous testosterone and cardiovascular disease in healthy men: a meta-analysis. Heart. 2011;97:870–875. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.210757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorius G, Spasevska S, Idan A, Turner L, Forbes E, Zamojska A, Allan CA, Ly LP, Conway AJ, McLachlan RI, Handelsman DJ. Serum testosterone, dihydrotestosterone and estradiol concentrations in older men self-reporting very good health: the healthy man study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012;77:755–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine GN, D’Amico AV, Berger P, Clark PE, Eckel RH, Keating NL, Milani RV, Sagalowsky AI, Smith MR, Zakai N. Androgen-deprivation therapy in prostate cancer and cardiovascular risk: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and American Urological Association: endorsed by the American Society for Radiation Oncology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:194–201. doi: 10.3322/caac.20061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TH. Testosterone deficiency: a risk factor for cardiovascular disease? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traish AM, Saad F, Feeley RJ, Guay A. The dark side of testosterone deficiency: III. Cardiovascular disease. J Androl. 2009;30:477–494. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.007245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggertson L. Brouhaha erupts over testosterone-testing advertising campaign. CMAJ. 2011;183:E1161–E1162. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgentaler A. Testosterone for Life. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sexual dysfunction as the last bastion of urological drug commercialisation within the pharmaceutical industry. BJU Int. 2011;107:1845–1846. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handelsmann DJ. Pharmacoepidemiology of testosterone prescribing in Australia, 1992–2010. Med J Aust. 2012;196:642–645. doi: 10.5694/mja11.11277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan EH, Pattman S, Pearce S, Quinton R. Many men are receiving unnecessary testosterone prescriptions. BMJ. 2012;345:e5469. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Assessing the Need for Clinical Trials of Testosterone Replacement Therapy. TESTOSTERONE AND AGING Clinical Research Directions. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calof OM, Singh AB, Lee ML, Kenny AM, Urban RJ, Tenover JL, Bhasin S. Adverse events associated with testosterone replacement in middle-aged and older men: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:1451–1457. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.11.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad RM, Kennedy CC, Caples SM, Tracz MJ, Bolona ER, Sideras K, Uraga MV, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Testosterone and cardiovascular risk in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:29–39. doi: 10.4065/82.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Balsells MM, Murad MH, Lane M, Lampropulos JF, Albuquerque F, Mullan RJ, Agrwal N, Elamin MB, Gallegos-Orozco JF, Wang AT, Erwin PJ, Bhasin S, Montori VM. Clinical review 1: adverse effects of testosterone therapy in adult men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2560–2575. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooling C, Xu L, Freeman G, Cowling B. Testosterone and cardiovasclar related events in men: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PROSPERO 2011:CRD42011001815 http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42011001815.

- Snyder PJ, Peachey H, Hannoush P, Berlin JA, Loh L, Lenrow DA, Holmes JH, Dlewati A, Santanna J, Rosen CJ, Strom BL. Effect of testosterone treatment on body composition and muscle strength in men over 65 years of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:2647–2653. doi: 10.1210/jc.84.8.2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder PJ, Peachey H, Hannoush P, Berlin JA, Loh L, Holmes JH, Dlewati A, Staley J, Santanna J, Kapoor SC, Attie MF, Haddad JG Jr, Strom BL. Effect of testosterone treatment on bone mineral density in men over 65 years of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1966–1972. doi: 10.1210/jc.84.6.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder PJ, Peachey H, Berlin JA, Rader D, Usher D, Loh L, Hannoush P, Dlewati A, Holmes JH, Santanna J, Strom BL. Effect of transdermal testosterone treatment on serum lipid and apolipoprotein levels in men more than 65 years of age. Am J Med. 2001;111:255–260. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00813-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugwell P, Judd MG, Fries JF, Singh G, Wells GA. Powering our way to the elusive side effect: a composite outcome ‘basket’ of predefined designated endpoints in each organ system should be included in all controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:785–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Loke YK, Spangler JG, Furberg CD. Risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events associated with varenicline: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2011;183:1359–1366. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen AP, de Vet HC, de Bie RA, Kessels AG, Boers M, Bouter LM, Knipschild PG. The Delphi list: a criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doshi P, Jones M, Jefferson T. Rethinking credible evidence synthesis. BMJ. 2012;344:d7898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7898.:d7898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis JP. Adverse events in randomized trials: neglected, restricted, distorted, and silenced. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1737–1739. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitrou I, Boutron I, Ahmad N, Ravaud P. Reporting of safety results in published reports of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1756–1761. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer M, Basaria S, Travison TG, Davda MN, Paley A, Cohen B, Mazer NA, Knapp PE, Hanka S, Lakshman KM, Ulloor J, Zhang A, Orwoll K, Eder R, Collins L, Mohammed N, Rosen RC, DeRogatis L, Bhasin S. Effect of testosterone replacement on response to sildenafil citrate in men with erectile dysfunction: a parallel, randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:681–691. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-10-201211200-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona G, Rastrelli G, Monami M, Guay A, Buvat J, Sforza A, Forti G, Mannucci E, Maggi M. Hypogonadism as a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality in men: a meta-analytic study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165:687–701. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattabiani C, Basaria S, Ceda GP, Luci M, Vignali A, Lauretani F, Valenti G, Volpi R, Maggio M. Relationship between testosterone deficiency and cardiovascular risk and mortality in adult men. J Endocrinol Invest. 2012;35:104–120. doi: 10.3275/8061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson CC 3rd, Rosano G. Exogenous testosterone, cardiovascular events, and cardiovascular risk factors in elderly men: a review of trial data. J Sex Med. 2012;9:54–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullett NP, Hebbar G, Ziegler TR. Update on clinical trials of growth factors and anabolic steroids in cachexia and wasting. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1143S–1147S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28608E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain J. Testosterone and the aging male: to treat or not to treat? Maturitas. 2010;66:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren D, Siemens DR, Izard J, Black A, Morales A. Clinical practice experience with testosterone treatment in men with testosterone deficiency syndrome. BJU Int. 2008;102:1142–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause W, Mueller U, Mazur A. Testosterone supplementation in the aging male: which questions have been answered? Aging Male. 2005;8:31–38. doi: 10.1080/13685530500048872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman JM, Vermeulen A. The decline of androgen levels in elderly men and its clinical and therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:833–876. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny AM, Prestwood KM, Gruman CA, Fabregas G, Biskup B, Mansoor G. Effects of transdermal testosterone on lipids and vascular reactivity in older men with low bioavailable testosterone levels. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M460–M465. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.7.M460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford BA, Liu PY, Kean MT, Bleasel JF, Handelsman DJ. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of androgen effects on muscle and bone in men requiring long-term systemic glucocorticoid treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3167–3176. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny AM, Prestwood KM, Gruman CA, Marcello KM, Raisz LG. Effects of transdermal testosterone on bone and muscle in older men with low bioavailable testosterone levels. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M266–M272. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.5.M266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JE, Perry HM 3rd, Kaiser FE, Kraenzle D, Jensen J, Houston K, Mattammal M, Perry HM Jr. Effects of testosterone replacement therapy in old hypogonadal males: a preliminary study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:149–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb02049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin P, Holmang S, Gustafsson C, Jonsson L, Kvist H, Elander A, Eldh J, Sjostrom L, Holm G, Bjorntorp P. Androgen treatment of abdominally obese men. Obes Res. 1993;1:245–251. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1993.tb00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan DH, Roberson PK, Johnson LE, Bishara O, Evans WJ, Smith ES, Price JA. Effects of muscle strength training and testosterone in frail elderly males. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:1664–1672. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000181840.54860.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svartberg J, Agledahl I, Figenschau Y, Sildnes T, Waterloo K, Jorde R. Testosterone treatment in elderly men with subnormal testosterone levels improves body composition and BMD in the hip. Int J Impot Res. 2008;20:378–387. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2008.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidle C, Schwartz S, Jacoby K, Sebree T, Smith T, Bachand R. AA2500 testosterone gel normalizes androgen levels in aging males with improvements in body composition and sexual function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2673–2681. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny AM, Kleppinger A, Annis K, Rathier M, Browner B, Judge JO, McGee D. Effects of transdermal testosterone on bone and muscle in older men with low bioavailable testosterone levels, low bone mass, and physical frailty. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1134–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02865.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman JM, Miller MG, Garwin JL, Fitzpatrick S, McWhirter C, Brennan JJ. Efficacy and safety study of 1.62% testosterone gel for the treatment of hypogonadal men. J Sex Med. 2011;8:2079–2089. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen L, Hojlund K, Hougaard DM, Brixen K, Andersen M. Testosterone therapy increased muscle mass and lipid oxidation in aging men. Age (Dordr) 2012;34:145–156. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9213-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legros JJ, Meuleman EJ, Elbers JM, Geurts TB, Kaspers MJ, Bouloux PM. Oral testosterone replacement in symptomatic late-onset hypogonadism: effects on rating scales and general safety in a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160:821–831. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh PJ, Jones RD, West JN, Jones TH, Channer KS. Testosterone treatment for men with chronic heart failure. Heart. 2004;90:446–447. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.014639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman IM, Visvanathan R, Hammond AJ, Morley JE, Field JB, Tai K, Belobrajdic DP, Chen RY, Horowitz M. Effect of testosterone and a nutritional supplement, alone and in combination, on hospital admissions in undernourished older men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:880–889. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testosterone treatment of men with alcoholic cirrhosis: a double-blind study. The Copenhagen Study Group for Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 1986;6:807–813. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840060502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basaria S, Coviello AD, Travison TG, Storer TW, Farwell WR, Jette AM, Eder R, Tennstedt S, Ulloor J, Zhang A, Choong K, Lakshman KM, Mazer NA, Miciek R, Krasnoff J, Elmi A, Knapp PE, Brooks B, Appleman E, Aggarwal S, Bhasin G, Hede-Brierley L, Bhatia A, Collins L, LeBrasseur N, Fiore LD, Bhasin S. Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:109–122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GM, Larbre JP, Spector TD, Perry LA, Da Silva JA. A randomized trial of testosterone therapy in males with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:568–573. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.6.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sih R, Morley JE, Kaiser FE, Perry HM 3rd, Patrick P, Ross C. Testosterone replacement in older hypogonadal men: a 12-month randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1661–1667. doi: 10.1210/jc.82.6.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English KM, Steeds RP, Jones TH, Diver MJ, Channer KS. Low-dose transdermal testosterone therapy improves angina threshold in men with chronic stable angina: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Circulation. 2000;102:1906–1911. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.16.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amory JK, Watts NB, Easley KA, Sutton PR, Anawalt BD, Matsumoto AM, Bremner WJ, Tenover JL. Exogenous testosterone or testosterone with finasteride increases bone mineral density in older men with low serum testosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:503–510. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny AM, Fabregas G, Song C, Biskup B, Bellantonio S. Effects of testosterone on behavior, depression, and cognitive function in older men with mild cognitive loss. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:75–78. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.1.M75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svartberg J, Aasebo U, Hjalmarsen A, Sundsfjord J, Jorde R. Testosterone treatment improves body composition and sexual function in men with COPD, in a 6-month randomized controlled trial. Respir Med. 2004;98:906–913. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockenbrough AT, Dittrich MO, Page ST, Smith T, Stivelman JC, Bremner WJ. Transdermal androgen therapy to augment EPO in the treatment of anemia of chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:251–262. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkin CJ, Pugh PJ, West JN, van Beek EJ, Jones TH, Channer KS. Testosterone therapy in men with moderate severity heart failure: a double-blind randomized placebo controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:57–64. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merza Z, Blumsohn A, Mah PM, Meads DM, McKenna SP, Wylie K, Eastell R, Wu F, Ross RJ. Double-blind placebo-controlled study of testosterone patch therapy on bone turnover in men with borderline hypogonadism. Int J Androl. 2006;29:381–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair KS, Rizza RA, O’Brien P, Dhatariya K, Short KR, Nehra A, Vittone JL, Klee GG, Basu A, Basu R, Cobelli C, Toffolo G, Dalla MC, Tindall DJ, Melton LJ 3rd, Smith GE, Khosla S, Jensen MD. DHEA in elderly women and DHEA or testosterone in elderly men. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1647–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmelot-Vonk MH, Verhaar HJ, Nakhai Pour HR, Aleman A, Lock TM, Bosch JL, Grobbee DE, van der Schouw YT. Effect of testosterone supplementation on functional mobility, cognition, and other parameters in older men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:39–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caminiti G, Volterrani M, Iellamo F, Marazzi G, Massaro R, Miceli M, Mammi C, Piepoli M, Fini M, Rosano GM. Effect of long-acting testosterone treatment on functional exercise capacity, skeletal muscle performance, insulin resistance, and baroreflex sensitivity in elderly patients with chronic heart failure a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:919–927. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aversa A, Bruzziches R, Francomano D, Rosano G, Isidori AM, Lenzi A, Spera G. Effects of testosterone undecanoate on cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in middle-aged men with late-onset hypogonadism and metabolic syndrome: results from a 24-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Sex Med. 2010;7:3495–3503. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas-Shankar U, Roberts SA, Connolly MJ, O’Connell MD, Adams JE, Oldham JA, Wu FC. Effects of testosterone on muscle strength, physical function, body composition, and quality of life in intermediate-frail and frail elderly men: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:639–650. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TH, Arver S, Behre HM, Buvat J, Meuleman E, Moncada I, Morales AM, Volterrani M, Yellowlees A, Howell JD, Channer KS. Testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men with type 2 diabetes and/or metabolic syndrome (the TIMES2 study) Diabetes Care. 2011;34:828–837. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CC, Tong SF, Low WY, Ng CJ, Khoo EM, Lee VK, Zainuddin ZM, Tan HM. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on the effect of long-acting testosterone treatment as assessed by the Aging Male Symptoms scale. BJU Int. 2012;110:260–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinchenko SY, Tishova YA, Mskhalaya GJ, Gooren LJ, Giltay EJ, Saad F. Effects of testosterone supplementation on markers of the metabolic syndrome and inflammation in hypogonadal men with the metabolic syndrome: the double-blinded placebo-controlled Moscow study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;73:602–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyos CM, Yee BJ, Phillips CL, Machan EA, Grunstein RR, Liu PY. Body compositional and cardiometabolic effects of testosterone therapy in obese men with severe obstructive sleep apnoea: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167:531–541. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haring R, Teumer A, Volker U, Dorr M, Nauck M, Biffar R, Volzke H, Baumeister SE, Wallaschofski H. Mendelian randomization suggests non-causal associations of testosterone with cardiometabolic risk factors and mortality. Andrology. 2013;1:17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2012.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie F, Cusan L, Gomez JL, Martel C, Berube R, Belanger P, Belanger A, Vandenput L, Mellstrom D, Ohlsson C. Comparable amounts of sex steroids are made outside the gonads in men and women: strong lesson for hormone therapy of prostate and breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;113:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie F. Intracrinology. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1991;78:C113–C118. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(91)90116-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fizazi K, Scher HI, Molina A, Logothetis CJ, Chi KN, Jones RJ, Staffurth JN, North S, Vogelzang NJ, Saad F, Mainwaring P, Harland S, Goodman OB Jr, Sternberg CN, Li JH, Kheoh T, Haqq CM, de Bono JS. Abiraterone acetate for treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final overall survival analysis of the COU-AA-301 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:983–992. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70379-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, Taplin ME, Sternberg CN, Miller K, De WR, Mulders P, Chi KN, Shore ND, Armstrong AJ, Flaig TW, Flechon A, Mainwaring P, Fleming M, Hainsworth JD, Hirmand M, Selby B, Seely L, de Bono JS. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Coronary Drug Project. Findings leading to discontinuation of the 2.5-mg day estrogen group. The Coronary Drug Project Research Group. JAMA. 1973;226:652–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basaria S, Davda MN, Travison TG, Ulloor J, Singh R, Bhasin S. Risk factors associated with cardiovascular events during testosterone administration in older men with mobility limitation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:153–160. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idan A, Griffiths KA, Harwood DT, Seibel MJ, Turner L, Conway AJ, Handelsman DJ. Long-term effects of dihydrotestosterone treatment on prostate growth in healthy, middle-aged men without prostate disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:621–632. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-10-201011160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunelius P, Lukkarinen O, Hannuksela ML, Itkonen O, Tapanainen JS. The effects of transdermal dihydrotestosterone in the aging male: a prospective, randomized, double blind study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1467–1472. doi: 10.1210/jc.87.4.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly LP, Jimenez M, Zhuang TN, Celermajer DS, Conway AJ, Handelsman DJ. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of transdermal dihydrotestosterone gel on muscular strength, mobility, and quality of life in older men with partial androgen deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4078–4088. doi: 10.1210/jc.86.9.4078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhasin S, Travison TG, Storer TW, Lakshman K, Kaushik M, Mazer NA, Ngyuen AH, Davda MN, Jara H, Aakil A, Anderson S, Knapp PE, Hanka S, Mohammed N, Daou P, Miciek R, Ulloor J, Zhang A, Brooks B, Orwoll K, Hede-Brierley L, Eder R, Elmi A, Bhasin G, Collins L, Singh R, Basaria S. Effect of testosterone supplementation with and without a dual 5alpha-reductase inhibitor on fat-free mass in men with suppressed testosterone production: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:931–939. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi AA, Mathur R, Halushka PV. Testosterone increases human platelet thromboxane A2 receptor density and aggregation responses. Circulation. 1995;91:2742–2747. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.91.11.2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyben FE, Graugaard C, Vaeth M. All-cause mortality and mortality of myocardial infarction for 989 legally castrated men. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20:863–869. doi: 10.1007/s10654-005-2150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow AJ, Higgins CD, Schoemaker MJ, Wright AF, Jacobs PA. Mortality in patients with Klinefelter syndrome in Britain: a cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6516–6522. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PL, Je Y, Schutz FA, Hoffman KE, Hu JC, Parekh A, Beckman JA, Choueiri TK. Association of androgen deprivation therapy with cardiovascular death in patients with prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA. 2011;306:2359–2366. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari M, Busse JW, Jackowski D, Montori VM, Schunemann H, Sprague S, Mears D, Schemitsch EH, Heels-Ansdell D, Devereaux PJ. Association between industry funding and statistically significant pro-industry findings in medical and surgical randomized trials. CMAJ. 2004;170:477–480. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluud LL. Bias in clinical intervention research. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:493–501. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitti D. Commentary: hormone replacement therapy and coronary heart disease: four lessons. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:461–463. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrouf FA, Artz S, Griffith J, Sirbu C, Kommor M. Testosterone and depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15:289–305. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000358315.88931.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamlian NT, Cole MG. Androgen treatment of depressive symptoms in older men: a systematic review of feasibility and effectiveness. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51:295–299. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolona ER, Uraga MV, Haddad RM, Tracz MJ, Sideras K, Kennedy CC, Caples SM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Testosterone use in men with sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:20–28. doi: 10.4065/82.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracz MJ, Sideras K, Bolona ER, Haddad RM, Kennedy CC, Uraga MV, Caples SM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Testosterone use in men and its effects on bone health. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2011–2016. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong A, Edmonds P. Testosterone therapy in HIV wasting syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:692–699. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns K, Beddall MJ, Corrin RC. Anabolic steroids for the treatment of weight loss in HIV-infected individuals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4:CD005483. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, Kannel WB. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke A, Guallar E, Rohrmann S, Nelson WG, Rifai N, Kanarek N, Feinleib M, Michos ED, Dobs A, Platz EA. Sex steroid hormone concentrations and risk of death in US men. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:583–592. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deloukas P, Kanoni S, Willenborg C, Farrall M, Assimes TL, Thompson JR, Ingelsson E, Saleheen D, Erdmann J, Goldstein BA, Stirrups K, Konig IR, Cazier JB, Johansson A, Hall AS, Lee JY, Willer CJ, Chambers JC, Esko T, Folkersen L, Goel A, Grundberg E, Havulinna AS, Ho WK, Hopewell JC, Eriksson N, Kleber ME, Kristiansson K, Lundmark P, Lyytikainen LP. Large-scale association analysis identifies new risk loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2012;45:25–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland LS, Robinson KA, Dickersin K. Understanding why evidence from randomised clinical trials may not be retrieved from Medline: comparison of indexed and non-indexed records. BMJ. 2012;344:d7501. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira ML, Herbert RD, Crowther MJ, Verhagen A, Sutton AJ. When is a further clinical trial justified? BMJ. 2012;345:e5913. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira TV, Ioannidis JP. Statistically significant meta-analyses of clinical trials have modest credibility and inflated effects. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:1060–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeLorier J, Gregoire G, Benhaddad A, Lapierre J, Derderian F. Discrepancies between meta-analyses and subsequent large randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:536–542. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708213370806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny AM, Bellantonio S, Gruman CA, Acosta RD, Prestwood KM. Effects of transdermal testosterone on cognitive function and health perception in older men with low bioavailable testosterone levels. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M321–M325. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.5.M321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin P, Oden B, Bjorntorp P. Assimilation and mobilization of triglycerides in subcutaneous abdominal and femoral adipose tissue in vivo in men: effects of androgens. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:239–243. doi: 10.1210/jc.80.1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Trials where authors contacted for additional information and responses.[13,35-37,40,42-48,100].

Quality assessment of the selected placebo-controlled RCTs of the effects of testosterone therapy on cardiovascular-related events (CRE) [19],[26],[39],[41],[44],[46],[48]-[68].

Description of cardiovascular-related events in the selected placebo-controlled RCTs [19],[26],[39],[41],[44],[46],[48]-[67],[101].