Abstract

Background

Locally harvested wild edible plants (WEPs) provide food as well as cash income for indigenous people and are of great importance in ensuring global food security. Some also play a significant role in maintaining the productivity and stability of traditional agro-ecosystems. Shangri-la region of Yunnan Province, SW China, is regarded as a biodiversity hotspot. People living there have accumulated traditional knowledge about plants. However, with economic development, WEPs are threatened and the associated traditional knowledge is in danger of being lost. Therefore, ethnobotanical surveys were conducted throughout this area to investigate and document the wild edible plants traditionally used by local Tibetan people.

Methods

Twenty-nine villages were selected to carry out the field investigations. Information was collected using direct observation, semi-structured interviews, individual discussions, key informant interviews, focus group discussions, questionnaires and participatory rural appraisal (PRA).

Results

Information about 168 wild edible plant species in 116 genera of 62 families was recorded and specimens were collected. Most species were edible greens (80 species) or fruits (78). These WEPs are sources for local people, especially those living in remote rural areas, to obtain mineral elements and vitamins. More than half of the species (70%) have multiple use(s) besides food value. Some are crop wild relatives that could be used for crop improvement. Several also have potential values for further commercial exploitation. However, the utilization of WEPs and related knowledge are eroding rapidly, especially in the areas with convenient transportation and booming tourism.

Conclusion

Wild food plants species are abundant and diverse in Shangri-la region. They provide food and nutrients to local people and could also be a source of cash income. However, both WEPs and their associated indigenous knowledge are facing various threats. Thus, conservation and sustainable utilization of these plants in this area are of the utmost importance. Documentation of these species may provide basic information for conservation, possibly further exploitation, and will preserve local traditional knowledge.

Keywords: Wild edible plants, Traditional knowledge, Biodiversity, Ethnobotany, Shangri-la region

Background

Wild edible plants (WEPs) refer to species that are harvested or collected from their wild natural habitats and used as food for human consumption [1-3]. They provide staple food for indigenous people, serve as supplementary food for non-indigenous people and are one of the primary sources of cash income for poor communities [4-6]. WEPs play an important role in ensuring food security and improve the nutrition in the diets of many people in developing countries [1,5]. They are potential sources of species for domestication and provide valuable genetic traits for developing new crops through breeding and selection [7,8].

Although domesticated plants are the main source of food and income for people in rural areas, they are not able to meet the annual food requirements [9-11]. Thus, the collection and consumption of wild edible plants has been “a way of life” to supplement dietary requirements for many rural populations throughout the world [5,12]. However, due to social change and acculturation processes, indigenous knowledge (or traditional knowledge) about the use of wild edible species is declining and even vanishing with modernization and increasing contacts with western lifestyles [13]. Meanwhile, the loss of traditional knowledge has also been recognized as one of the major factors that have negative effects on the conservation of biological diversity [14]. Thus, it is becoming urgent to document and revitalize traditional knowledge of WEPs to preserve genetic and cultural diversity [12,15,16]. China is renowned for its wide use of wild harvested resources in the human diet, and many studies have focused on wild edible plants [17-28]. These ethnobotanical surveys not only play an important role in conserving traditional knowledge associated with WEPs, but also contribute to nutritional analysis of the most widely used species [1,13]. Nutritional analyses may provide significant information for the utilization of those species that have the best nutritional values, thus helping to maintain dietary diversity and improve local food security [1,2,15].

Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Yunnan Province, commonly known as the Shangri-la region, belongs to the world-famous area called Three Parallel Rivers (Nujiang River, Lancang River and Jinsha River). It is the core of the eastern Himalayas and is regarded as a biodiversity hotspot [29]. Because of its complex topography and high diversity of climates, abundant plant and animal species are distributed in this area [30,31]. Although Tibetans account for about 32.36% of the total population of the whole prefecture and have a relatively well-preserved and distinct cultural identity, there are also Lisu, Han, Naxi, Yi as well as Bai populations, among whom mutual cultural influences have existed for a long time [30,31]. Furthermore, the diet of local Tibetan people differs somewhat from that of Tibetans in Xizang Autonomous Region. People living in the Tibetan Plateau have a limited range of food choices. The staple traditional diet includes Tsampa (made from hull-less barley), yak meat, mutton, buttered tea, sweet tea, barley wine and yogurt [32]. They seldom eat vegetables or fruits. On the other hand, because plant resources in Diqing Prefecture are more plentiful, and local Tibetans are influenced by other nationalities, they not only cultivate various crops, but also collect wild edible plants as supplementary food. These WEPs provide various microelements, and are also an important feature of local agrobiodiversity in which Tibetans have traditionally lived. However, the ecology of Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture is very fragile, and agrobiodiversity is being rapidly lost due to many natural and human caused factors [33-35]. Many precious plant resources that may have potential for future sustainable development are vanishing before they have been discovered. The reduction of plant diversity also leads to the extinction of the associated indigenous knowledge [36]. Thus, documentation and evaluation of edible plants and relevant local knowledge is urgently needed. This work may guide proper conservation and sustainable utilization of those wild food plants and related indigenous knowledge.

Although there are several ethnobotanical studies concerning wild food plants used by ethnic minorities, such as Mongolians [18,19], Miao in Hunan Province [21] and various ethnic groups in Yunnan Province [5,17,26-28], to our knowledge, information on WEPs of the Shangri-la region used by Tibetans has not previously been documented. In order to fill this gap, ethnobotanical surveys were conducted throughout the prefecture. Scientific and local names, plant parts used, modes of preparation, seasonality patterns in collection and use, and commercialization possibilities of the WEPs are presented in this paper.

Methods

Study area

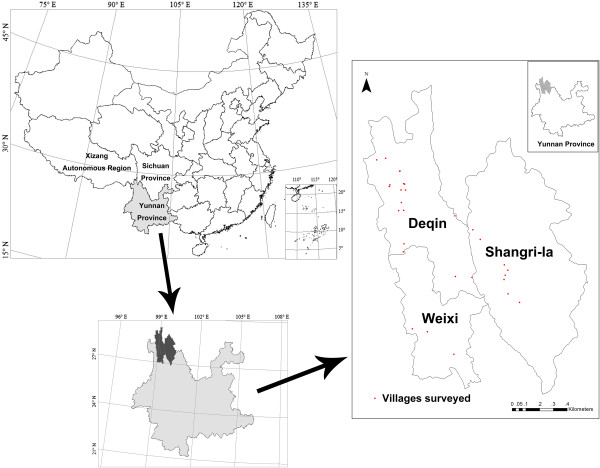

The study was carried out in Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, northwest Yunnan, situated in the south of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of the eastern Himalayas, at the junction of Yunnan, Tibet and Sichuan Provinces (between 98°35’-100°19’ E and 26°52’-29°16’ N) (Figure 1). Three counties, Shangri-la, Deqin and Weixi are administered by the prefecture, with a total area of 23,870 square kilometers and a population of about 400,000. The terrain is higher in the north and lower in the south. The lowest altitude, 1,480 m is at the junction of the Biyu and Lancang Rivers in Weixi County, and the highest altitude, 6,740 m is Kawagebo Peak of the Meili Snow Mountains. The climate of Diqing is divided into five zones: 1) northern subtropical and warm temperate (below 2500 m); 2) temperate (2500–3000 m); 3) cold temperate (3000–4000 m); 4) frigid (4000–5000 m); and 5) glacier (above 5000 m). Abundant plant resources are distributed in this area because of its unique geographical location and climate diversity [31].

Figure 1.

Location of the area covered in an investigation into the wild edible plants used by Tibetans in the Shangri-la region, Yunnan, China.

Field survey and data collection

Prior to our field work, relevant literature was consulted to obtain information on the topography, climate, and local culture of Diqing Prefecture, this was helpful in choosing the specific study sites [31]. Field studies were carried out during three visits in March, July and August, 2012. After considering the terrain and climate condition, 29 villages belonging to three counties (8 in Shangri-la, 3 in Weixi and 18 in Deqin) and located in high mountains as well as lower river valleys were randomly selected to carry out ethnobotanical investigation (Table 1). Two-hundred and eighty-two randomly selected households (eight to ten people per village) were surveyed. Ethnobotanical data were collected through different interview methods (participatory rural appraisal (PRA), direct observation, semi-structured interviews, key informant interviews, individual discussions, focus group discussions and questionnaires) [37-40].

Table 1.

Villages surveyed in investigations of wild edible plants used by Tibetans in Shangri-la region, Yunnan Province, China

| No. | Name of village | Latitude (north) | Longitude (east) | Altitude(m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Laza Village, Shangri-la County |

27°45’39.6” |

99°40’22.8” |

3320 |

| 2 |

Jiefang Village, Shangri-la County |

27°51’46.8” |

99°41’56.4” |

3280 |

| 3 |

Nishi Village, Shangri-la County |

27°47’21.8” |

99°40’59.5” |

3290 |

| 4 |

Kaisong Village, Shangri-la County |

27°53’49.6” |

99°38’21.5” |

3270 |

| 5 |

Dala Village, Shangri-la County |

27°31’12” |

99°57’36” |

3370 |

| 6 |

Xiaozhongdian Village, Shangri-la County |

27°34’12” |

99°47’59” |

3260 |

| 7 |

Xingfu Village, Shangri-la County |

28°8’27.6” |

99°25’58.8” |

2230 |

| 8 |

Nixi Village, Shangri-la County |

28°4’1.2” |

99°29’34.8” |

3170 |

| 9 |

Laohao Village, Weixi County |

27°10’54.1” |

99°17’20.4” |

2260 |

| 10 |

Gongyuan Village, Weixi County |

27°21’50.35” |

99°5’11.45” |

1690 |

| 11 |

Biluo Village, Weixi County |

27°25’22.8” |

99°1’58.8” |

2630 |

| 12 |

Feilaisi Village, Deqin County |

28°26’31.2” |

98°52’44.4” |

3390 |

| 13 |

Wunongding Village, Deqin County |

28°26’56.4” |

98°54’46.8’ |

3530 |

| 14 |

Mingyong Village, Deqin County |

28°28’8.4” |

98°47’42” |

2270 |

| 15 |

Adunzi Village, Deqin County |

28°29’13.6” |

98°54’38.9” |

3290 |

| 16 |

Gusong Village, Deqin County |

28°29’37.7” |

98°54’10.1” |

3590 |

| 17 |

Adong Village, Deqin County |

28°45’46.8” |

98°39’14.4” |

2690 |

| 18 |

Hongpo Village, Deqin County |

28°17’2.4” |

98°54’18” |

2810 |

| 19 |

Guonian Village, Deqin County |

28°17’16.71” |

98°51’49.61” |

2130 |

| 20 |

Jiulongding Village, Deqin County |

28°20’42” |

98°53’13.2” |

2570 |

| 21 |

Sinong Village, Deqin County |

28°29’9.18’ |

98°47’33.42’ |

2320 |

| 22 |

Badong Village, Deqin County |

27°57’39.6” |

98°54’0” |

2240 |

| 23 |

Cizhong Village, Deqin County |

28°01’16.44’ |

98°54’16.14’ |

1970 |

| 24 |

Gongka Village, Deqin County |

28°35’27.6” |

98°52’12” |

3080 |

| 25 |

Jiunong Village, Deqin County |

28°43’28.77” |

98°41’4.76” |

3160 |

| 26 |

Luwa Village, Deqin County |

28°40’30” |

98°41’38.4” |

2290 |

| 27 |

Xiaruo Village, Deqin County |

27°48’3.77” |

99°18’5.11” |

2040 |

| 28 |

Tuoding Village, Deqin County |

27°46’10.9’ |

99°25’37.2’ |

1940 |

| 29 | Benzilan Village, Deqin County | 28°14’36.83” | 99°18’7.43” | 2150 |

During our survey, the local Tibetan pronunciations, parts used, collection period and preparation methods plants were recorded. Because local Tibetan pronunciations differ from the formal Tibetan pronunciation of Xizang Autonomous Region, and the names of some species were even pronounced the same as in Mandarin Chinese, we recorded the names phonetically exactly as they were spoken to us. Most Tibetans in Diqing Prefecture, especially the official workers, students and traders can speak basic Mandarin, therefore our interviews were in Mandarin and did not use interpreters.

Specimens were examined and identified by the authors and other taxonomists and will be deposited in the Herbarium of the Minzu University of China (Beijing).

Results and discussion

Wild food plant diversity and frequently utilized species

The study area is floristically rich and has a large number of useful WEP species. The 168 species documented include angiosperms (153 spp.), gymnosperms (4), pteridophytes (4), algae (2) and lichens (5) (Table 2), of which 41.1% are endemic to China and 11.9% endemic to northwestern Yunnan Province. Details of utilization are given in Table 3 (plants mentioned only by one informant are not documented in this list). The average number of species mentioned per informant is around ca. 8 species. Plants belonging to 62 families and 116 genera are distributed into different life forms, with herbs (43.5%) and shrubs (26.8%) having the most species, similar to a survey conducted in Yunnan Province [17] and another in Hunan Province [21]. The majority of food plants belong to the Rosaceae (34 species), Liliaceae (9), Brassicaceae (9), Araliaceae (6) and Berberidaceae (6). The genera represented by the highest number of species are Rubus (8 species), followed by Maianthemum (6), Berberis (4), Cornus (4), Lindera (4) and Pyrus (4).

Table 2.

Taxonomic distribution of wild edible plants used by Tibetans in Shangri-la region, Yunnan Province, China

| Plant group | Number of species | Number of genera | Number of families |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angiosperm |

153 |

101 |

47 |

| Gymnosperm |

4 |

4 |

4 |

| Pteridophyte |

4 |

4 |

4 |

| Algae |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| Lichen |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Total | 168 | 116 | 62 |

Table 3.

Wild edible plants used by the Tibetans in Shangri-la region, Yunnan Province, China

| Latin name | Local name | Family name | Distribution | Parts used | Local use (edible only) | Collection period | Additional local use(s) | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Actinidia arguta (Siebold et Zucc.) Planch. ex Miq. |

Zhemenkoubu |

Actinidiaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

ripe fruits eaten fresh. |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as hedge plants. |

*** |

|

Actinidia pilosula (Finet et Gagnep.) Stapf ex Hand.-Mazz. |

Zhemenkoubu |

Actinidiaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

ripe fruits eaten fresh. |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as hedge plants. |

** |

|

Actinidia venosa Rehder |

Zhemenkoubu |

Actinidiaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

ripe fruits eaten fresh. |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as hedge plants. |

** |

|

Adenophora khasiana (Hook. f. et Thomson) Collett et Hemsl. |

Zheibamiedu |

Campanulaceae |

Weixi and Deqin |

Roots |

stewed with meat and eaten as tonic. |

Jul-Sept |

Flowers and stems used for weisang. Aerial parts used as fodder. Roots used to treat cough and clearing heat. |

*** |

|

Alectoria sulcata Nyl. |

Shuhua |

Usneaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Whole plant |

stir-fried |

Jul-Sep |

|

* |

|

Allium hookeri Thwaites var. muliense Airy-Shaw |

Rijiucai |

Liliaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Aerial parts |

stir-fried or added to soups |

May-Aug |

|

*** |

|

Allium ovalifolium Hand.-Mazz. |

Rijiucai |

Liliaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Aerial parts |

stir-fried or added to soups |

May-Aug |

|

***** |

|

Allium trifurcatum (F. T. Wang et T. Tang) J. M. Xu |

Rijiucai |

Liliaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Aerial parts |

stir-fried or added to soups |

May-Aug |

|

**** |

|

Amaranthus caudatus L. |

Yani |

Amaranthaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried or added to soups |

Jun-Jul |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

*** |

|

Amaranthus hypochondriacus L. |

Yani |

Amaranthaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried or added to soups |

Jun-Jul |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

*** |

|

Amygdalus mira (Koehne) Ricker |

Yemaotao; Kamu |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh. |

Jul-Aug |

Seeds used to relieve a cough and cure injuries. |

*** |

|

Anemone rivularis Buch.-Ham. ex DC. |

Huzhangcao |

Ranunculaceae |

Weixi |

Roots |

stewed with meat and eaten as tonic |

Jun-Sept |

Roots used to treat bronchitis. Whole plant used as ornamental. |

* |

|

Aralia caesia Hand.-Mazz. |

Shutoucai |

Araliaceae |

Shangri-la |

Young leaves and leaf buds |

stir-fried or eaten fresh |

Apr-May |

|

**** |

|

Aralia chinensis L. |

Gege |

Araliaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young leaves and leaf buds |

stir-fried or eaten fresh |

Apr-May |

Bark used for weisang |

***** |

|

Arctium lappa L. |

Baomujicigen |

Asteraceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Roots |

stewed with meat and eaten as tonic. |

Jun-Aug |

Fruits, leaves and roots used to relieve fever, and treat measles, dysentery and gastropathy. |

*** |

|

Arisaema erubescens (Wall.) Schott |

Reduo |

Araceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young leaves |

stir-fried |

Jun-Jul |

Tubers used to relieve cough and treat hemoptysis and pneumonia. |

** |

|

Aristolochia delavayi Franch. |

Ricaoko |

Aristolochiaceae |

Shangri-la |

Whole plants |

stir-fried and used as spice |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as stomachic tonic. |

*** |

|

Armeniaca mume Siebold |

Kangjue |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh. |

Aug |

Used as rootstock for Armeniaca vulgaris. |

* |

|

Arundinaria faberi Rendle |

Sunzi |

Poaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

New shoots |

boiled or stir-fried |

Jul-Aug |

Aerial parts used as fodder and to make bamboo wares. |

***** |

|

Berberis amoena Dunn |

Qiesi |

Berberidaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems, leaves and fruits |

eaten fresh |

May-Sep |

Whole plants used as fence and hedge plants. |

*** |

|

Berberis jamesiana Forrest et W. W. Sm. |

Qiesi |

Berberidaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems, leaves and fruits |

eaten fresh |

May-Sep |

Whole plants used as fence and hedge plants. |

*** |

|

Berberis pruinosa Franch. |

Qiesi |

Berberidaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems, leaves and fruits |

eaten fresh |

May-Sep |

Whole plants used as fence and hedge plants. |

*** |

|

Berberis weisiensis C. Y. Wu ex S. Y. Bao |

Qiesi |

Berberidaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems, leaves and fruits |

eaten fresh |

May-Sep |

Whole plants used as fence and hedge plants. |

** |

|

Berchemia hirtella Tsai et K. M. Feng |

Zhila |

Rhamnaceae |

Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sep |

|

** |

|

Berchemia hirtella Tsai et K. M. Feng |

Zhila |

Rhamnaceae |

Deqin |

Young leaves |

used for making tea |

Apr-Jun |

|

** |

|

Berchemia sinica C. K. Schneid. |

Zhila |

Rhamnaceae |

Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sep |

|

** |

|

Berchemia sinica C. K. Schneid. |

Zhila |

Rhamnaceae |

Deqin |

Young leaves |

used for making tea |

Apr-Jun |

|

** |

|

Boehmeria penduliflora Wedd. ex Long |

Sejia |

Urticaceae |

Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

boiled or stir-fried |

Jun-Jul |

|

* |

|

Boehmeria tricuspis (Hance) Makino |

Sejia |

Urticaceae |

Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried |

Jun-Jul |

|

* |

|

Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) L'Hér. ex Vent. |

|

Moraceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Sep-Oct |

Leaves used as fodder. Bark used for papermaking. |

* |

|

Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medik. |

Zijisuona |

Brassicaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Aerial part |

stir-fried |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

** |

|

Cardamine yunnanensis Franch. |

Lijisuona |

Brassicaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Aerial part |

stir-fried |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

** |

|

Cephalotaxus fortunei Hook. var. alpina H. L. Li |

Miyou |

Cephalotaxaceae |

Weixi, Deqin |

Seeds |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

Sep-Oct |

Plants used as fuel-wood. Seeds used to expel parasite. |

* |

|

Cerasus conadenia (Koehne) T. T. Yu et C. L. Li |

Xumumiedu |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Jul-Aug |

Flowers and leaves used for weisang |

*** |

|

Cerasus tomentosa (Thunb.) Wall. |

Nuosi |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Jul-Sept |

|

** |

|

Chaenomeles speciosa (Sweet) Nakai |

Suomugua |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

stewed with meat as spice and used to prepare local wine |

Sept-Oct |

|

*** |

|

Chenopodium album L. |

Hui |

Chenopodiaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried |

Jun-Jul |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

*** |

|

Cinnamomum glanduliferum (Wall.) Meisner |

Xiangzhangzi |

Lauraceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

stir-fried and used as spices |

Aug-Sept |

Fruits used to treat stomachache. |

* |

|

Cirsium japonicum (Thunb.) Fisch. ex DC. |

Baimaci |

Asteraceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Roots |

stewed with meat and eaten as tonic |

Jun-Aug |

Young stems and leaves used as fodder. |

*** |

|

Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. var. handeliana (Nannf.) L. T. Shen |

Dangshen |

Campanulaceae |

Deqin and Weixi |

Roots |

stewed with meat and eaten as tonic |

Jul-Sept |

Aerial parts used as fodder. Roots used to invigorate the spleen. |

*** |

|

Coriaria nepalensis Wall. |

Masen |

Coriariaceae |

Weixi |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

May-Jun |

|

* |

|

Cornus capitata Wall. |

Jisuo; Jisuziguo |

Cornaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Fruits, stems and leaves used as veterinary medicine. |

*** |

|

Cornus macrophylla Wall. |

Dengtaishu |

Cornaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Seeds |

used for making vegetable oil. |

Aug-Sept |

Plants used as fuel-wood. |

** |

|

Cornus schindleri Wangerin |

Saisaizi |

Cornaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

seeds |

used for making vegetable oil |

Aug-Sept |

Plants used as fuel-wood. |

** |

|

Cornus ulotricha C. K. Schneid. et Wangerin |

Dengtaishu |

Cornaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

seeds |

used for making vegetable oil |

Aug-Sept |

Plants used as fuel-wood. |

* |

|

Corylus chinensis Franch. |

Jilizi |

Betulaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

used for making pastries |

Sept-Oct |

Wood used for construction or furniture. |

** |

|

Corylus yunnanensis (Franch.) Camus |

Shanbaiguo |

Betulaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

used for making pastries |

Sept-Oct |

Woods used for construction or furniture. |

* |

|

Cotinus coggygria Scop. var. glaucophylla C. Y. Wu |

Jiade |

Anacardiaceae |

Shangri-la |

Young leaves |

boiled or stir-fried |

May-Jun |

Whole plants used as ornamental. |

* |

|

Crataegus chungtienensis W. W. Sm. |

Lubu |

Rosaceae |

Weixi and Shangri-la |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Sept |

Whole plants used as fence and hedge plants. |

*** |

|

Crataegus oresbia W. W. Sm. |

Lubu |

Rosaceae |

Weixi and Shangri-la |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as fence and hedge plants. |

*** |

|

Cynanchum forrestii Schltr. |

Babeda |

Asclepiadaceae |

Deqin and Weixi |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Oct |

Roots stewed with meat and eaten to treat rheumatism. |

* |

|

Davidia involucrata Baill. var. vilmoriniana (Dode) Wangerin |

Labizi |

Nyssaceae |

Weixi |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Sept-Oct |

Whole plant used as ornamental. |

* |

|

Debregeasia orientalis C. J. Chen |

Jiaojia |

Urticaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh and used to make local wine |

Jun-Aug |

Roots used to treat rheumatoid arthritis and broken bones. |

* |

|

Decaisnea insignis (Griff.) Hook. f. et Thomson |

Xianli |

Lardizabalaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh and used to make local wine |

Jul-Aug |

Roots and fruits used to clearing heat. |

*** |

|

Dioscorea melanophyma Prain et Burkill |

Huangshayue |

Dioscoreaceae |

Weixi |

Tubers |

boiled or stir-fried |

Jun-Jul |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

** |

|

Diospyros lotus L. |

Tazhi |

Ebenaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Sept-Oct |

|

*** |

|

Duchesnea indica (Andrews) Focke |

Dihongpao |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Jun-Jul |

|

* |

|

Elaeagnus multiflora Thunb. |

Cibie |

Elaeagnaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Jun-Jul |

|

** |

|

Elaeagnus umbellata Thunb. |

Yangnaiguo |

Elaeagnaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Jul-Aug |

|

** |

|

Eriobotrya salwinensis Hand.-Mazz. |

|

Rosaceae |

Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Jun-Aug |

Plants used as fuel-wood. |

* |

|

Eutrema deltoideum (Hook. f. et Thomson) O. E. Schulz |

Limo |

Brassicaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

** |

|

Eutrema heterophyllum (W. W. Sm.) H. Hara |

Limo |

Brassicaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

** |

|

Eutrema himalaicum Hook. f. et Thomson |

Limo |

Brassicaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

** |

|

Fagopyrum dibotrys (D. Don) H. Hara |

Wanao |

Polygonaceae |

Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried |

Jun-Aug |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

* |

|

Fargesia melanostachys (Hand.-Mazz.) T. P. Yi |

Sunzi |

Poaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

New shoots |

boiled or stir-fried |

May-Aug |

Aerial parts used as fodder and to make bamboo wares. |

***** |

|

Ficus pumila L. |

Dongshili |

Moraceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

used for making bean jelly |

Jul-Aug |

Leaves used as fodder. |

* |

|

Ficus sarmentosa Buch.-Ham. ex Sm. |

dongshili |

Moraceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

used for making bean jelly |

Jul-Aug |

Leaves used as fodder. |

* |

|

Foeniculum vulgare Mill. |

Asi |

Apiaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

May-Jul |

|

** |

|

Fragaria moupinensis (Franch.) Cardot |

Gasuo |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh. |

Jun-Jul |

Whole plants used as fodder. |

** |

|

Galinsoga parviflora Cav. |

Nawabijia |

Asteraceae |

Deqin and Weixi |

Young stems and leaves |

boiled or stir-fried |

Jun-Aug |

Whole plants used as fodder. |

* |

|

Ginkgo biloba L. |

Baiguo |

Ginkgoaceae |

Deqin, Weixi |

Seeds |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

Sep-Oct |

Seeds used to treat asthma. |

* |

|

Gnaphalium affine D. Don |

Qingmincai |

Asteraceae |

Weixi |

Young leaves |

grounded with sticky rice to make rice cake. |

Apr-May |

Leaves used to treat cuts and gun shot wounds. |

* |

|

Herminium lanceum (Thunb. ex Sw.) Vuijk |

Lianxiongde |

Orchidaceae |

Shangri-la |

Whole plant |

stewed with meat and eaten as tonic. |

Aug-Sep |

Whole plant used as fodder. |

* |

|

Hippophae rhamnoides L. subsp. yunnanensis Rousi |

Xiju |

Elaeagnaceae |

Deqin. Shangri-la |

Fruits |

eaten fresh or used to make beverage and wine. |

Aug-Oct |

Fruits used to treat cough and invigorate the circulation of blood. |

***** |

|

Houttuynia cordata Thunb. |

Zhergen |

Saururaceae |

Weixi, Shangri-la |

Leaves and roots |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

Jun-Jul |

|

*** |

|

Juglans regia L. |

Daiga |

Juglandaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Seeds |

eaten fresh or stir-fried, and used for making vegetable oil. |

Aug-Sept |

Plants used as fuel-wood. |

*** |

|

Kalopanax septemlobus (Thunb.) Koidz. |

Cilaobao |

Araliaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

May-Jun |

|

** |

|

Lethariella cladonioides (Nyl.) Krog |

Gangge |

Parmeliaceae |

Deqin |

Whole plant |

used for making tea, wine and beverage |

Aug-Oct |

Used to tranquilize mind and clearing heat. |

* |

|

Leycesteria formosa Wall. |

Sezha |

Caprifoliaceae |

Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh. |

Aug-Oct |

|

* |

|

Ligusticum daucoides (Franch.) Franch. |

Riqincai |

Apiaceae |

Shangri-la |

Whole plants |

stir-fried or added to soups |

Apr-May |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

**** |

|

Lindera kariensis W. W. Sm. |

Rihujiao |

Lauraceae |

Weixi, Deqin |

Fruits |

used as spices |

Jul-Sept |

|

** |

|

Lindera nacusua (D. Don) Merr. |

Rihujiao |

Lauraceae |

Weixi |

Fruits |

used as spices |

Jul-Sept |

|

** |

|

Lindera obtusiloba Blume var. heterophylla (Meisn.) H. P. Tsui |

Rihujiao |

Lauraceae |

Weixi |

Fruits |

used as spices |

Jul-Sept |

|

* |

|

Lindera reflexa Hemsl. |

Rihujiao |

Lauraceae |

Weixi |

Fruits |

used as spices |

Jul-Sept |

|

* |

|

Lobaria sp. |

Qingwapi |

Stictaceae |

Shangri-la and Weixi |

Aerial part |

eaten fresh |

Jul-Sept |

Whole plant used to treat dyspepsia. |

* |

|

Lycopus lucidus Turcz. ex Benth. |

Ganluo |

Lamiaceae |

Shangri-la |

Young stems and leaves |

eaten fresh or stir-fried or used for making pickle |

Jul-Aug |

|

** |

|

Mahonia duclouxiana Gagnep. |

Jisa |

Berberidaceae |

Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh. |

Aug-Sep |

Whole plants used as hedge plants. |

* |

|

Maianthemum atropurpureum (Franch.) LaFrankie |

Zhuyecai; Nibai |

Liliaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young shoots and leaves |

stir-fried or added to soups |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

***** |

|

Maianthemum forrestii (W. W. Smith) LaFrankie |

Zhuyecai; Nibai |

Liliaceae |

Shangri-la and Weixi |

Young shoots and leaves |

stir-fried or added to soups |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

**** |

|

Maianthemum henryi (Baker) LaFrankie |

Zhuyecai; Nibai |

Liliaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young shoots and leaves |

stir-fried or added to soups |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

**** |

|

Maianthemum oleraceum (Baker) LaFrankie |

Zhuyecai; Nibai |

Liliaceae |

Weixi, Shangri-la |

Young shoots and leaves |

stir-fried or added to soups |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

*** |

|

Maianthemum purpureum (Wallich) LaFrankie |

Zhuyecai; Nibai |

Liliaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young shoots and leaves |

stir-fried or added to soups |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

***** |

|

Maianthemum tatsienense (Franct.) LaFrankie |

Zhuyecai; Nibai |

Liliaceae |

Shangri-la |

Young shoots and leaves |

stir-fried or added to soups |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

**** |

|

Malus rockii Rehder |

Tangli |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Sept |

Plants used as fuel-wood, and rootstock for Malus pumila. Whole plants used as fence. |

*** |

|

Malus spectabilis (Ait.) Borkh. |

Haitangguo |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Fruits decoction used to treat dark urine. |

** |

|

Malva verticillata L. |

Jiangba |

Malvaceae |

Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried |

Jun-Aug |

Leaves, stems and seeds used as fodder. Whole plant used as ornamental. |

* |

|

Matteuccia struthiopteris (L.) Tadaro |

Huangguaxiang |

Onocleaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Immature fronds |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

May-Jun |

|

**** |

|

Medicago lupulina L. |

Mocuo |

Fabaceae |

Deqin, Shangri-la |

Young stems and leaves |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

Jun-Jul |

Leaves, stems, flowers and seeds used as fodder. |

* |

|

Megacarpaea delavayi Franch. |

Yuose |

Brassicaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

** |

|

Megacarpaea polyandra Benth. ex Madden |

Yuose |

Brassicaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

** |

|

Mentha canadensis L. |

Qiubi |

Lamiaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young leaves |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

Jun-Aug |

|

** |

|

Nostoc sphaerioides Kützing |

Shuimuer |

Nostocaceae |

Shangri-la |

Whole plant |

eaten fresh or added to soups |

Jun-Jul |

Whole plant used to treat burns and scalds. |

* |

|

Metapanax delavayi (Franch.) J. Wen et Frodin |

|

Araliaceae |

Deqin, Weixi |

Young leaves |

used for making tea |

Apr-May |

Whole plants used as hedge plants. |

* |

|

Ophioglossum reticulatum L. |

Yimuyidun |

Ophioglossaceae |

Shangri-la |

Immature fronds |

stir-fried or added to soups |

Jul-Aug |

Whole plants used to treat impotence and lumbago. |

* |

|

Opuntia monacantha (Willd.) Haw. |

Xianrenguo |

Cactaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sep |

Tubers and fruits used as fodder. Whole plants used as fence and hedge plants. |

*** |

|

Oreorchis indica (Lindl.) Hook. f. |

Xiabaji |

Orchidaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Pseudobulbs |

boiled or stir-fried |

Jun-Aug |

Whole plants used as fodder. Pseudobulbs used to stop bleeding and detumescence. |

* |

|

Osmunda japonica Thunb. |

Shuijuecai |

Osmundaceae |

Weixi |

Immature fronds |

stir-fried |

May-Jun |

|

*** |

|

Osteomeles schwerinae C. K. Schneid. |

Sele |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Leaves and fruits used as fodder. |

** |

|

Panax japonicus (T. Nees) C. A. Meyer var. major (Burkill) C. Y. Wu et K. M. Feng |

Gedeqi |

Araliaceae |

Shangri-la |

Young stems and leaves |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

May-Jun |

Whole plants used as fodder. Roots used to stop bleeding. |

*** |

|

Panax japonicus (T. Nees) C. A. Meyer var. major (Burkill) C. Y. Wu et K. M. Feng |

Gedeqi |

Araliaceae |

Shangri-la |

Rhizomes |

stewed with meat and eaten as tonic. |

Jul-Aug |

Whole plants used as fodder. Rhizomes used to stop bleeding. |

*** |

|

Pentapanax henryi Harms |

|

Araliaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

Apr-May |

|

** |

|

Photinia glomerata Rehder et E. H. Wilson |

Chongsi |

Rosaceae |

Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Sept |

|

* |

|

Phyllanthus emblica L. |

Ganlan |

Euphorbiaceae |

Shangri-la |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Jul-Sept |

Barks used to extract tannin. |

*** |

|

Phytolacca acinosa Roxb. |

Tuoqiong |

Phytolaccaceae |

Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

Jul-Aug |

Roots used to promote diuresis. |

* |

|

Pinellia pedatisecta Schott |

Luoa |

Araceae |

Deqin |

Young leaves |

stir-fried |

Jun-Jul |

Corms used to treat vomit and http://reducehttp://phlegm. |

* |

|

Pinus armandii Franch. |

Seitu; Songzi |

Pinaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Seeds |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

Sept-Oct |

Leaves and stems used for weisang. Needles used as fodder. Plants used as fuel-wood. |

** |

|

Pistacia weinmanniifolia J. Poiss. ex Franch. |

Li |

Anacardiaceae |

Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Leaves and stems used for weisang. Leaves and fruits used as fodder. |

**** |

|

Plantago asiatica L. |

Hamaye |

Plantaginaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Whole plants |

boiled or stir-fried |

Jun-Aug |

Leaves, stems, flowers and seeds used as fodder. |

*** |

|

Plantago major L. |

Hamaye |

Plantaginaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Whole plants |

boiled or stir-fried |

Jun-Aug |

Leaves, stems, flowers and seeds used as fodder. |

*** |

|

Potentilla anserina L. |

Chuomo |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Roots |

eaten fresh or boiled |

Jun-Sept |

Leaves, stems and fruits used as fodder. Roots used to control leukorrhea flow. |

*** |

|

Potentilla coriandrifolia D. Don var. dumosa Franch. |

Zumuyasha |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Roots |

eaten after boiling |

Jun-Sept |

Whole plants used as fodder. |

* |

|

Potentilla leuconota D. Don |

Pagu |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Roots |

eaten after boiling |

Jun-Sept |

Whole plants used as fodder. |

* |

|

Prasiola subareolata Skuja. |

Shihuacai |

Prasiolaceae |

Shangri-la |

Whole plants |

eaten fresh or added to soups |

Jun-Jul |

|

* |

|

Prinsepia utilis Royle |

Qingciguo |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Seeds |

used for making vegetable oil |

Jul-Aug |

|

*** |

|

Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn var. latiusclum (Desv.) Underw. ex A. Heller |

Zhila |

Pteridaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Immature fronds |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

May-Jul |

Whole plant used to treat rheumatism or for clearing heat. |

**** |

|

Pyracantha fortuneana (Maxim.) H. L. Li |

Sare |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Sept-Oct |

|

* |

|

Pyrus betulifolia Bunge |

Reli |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Oct |

|

* |

|

Pyrus calleryana Decne. |

Xialie |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Oct |

|

* |

|

Pyrus pashia Buch.-Ham. ex D. Don |

Suilun |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Oct |

|

** |

|

Pyrus pseudopashia T. T. Yu |

Suilun |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

|

** |

|

Ramalina fastigiata (Pers.) Ach. |

Shuhua |

Ramalinaceae |

Whole plant |

Whole plant |

stir-fried |

Jul-Sept |

|

* |

|

Rheum likiangense Sam. |

Mojue |

Polygonaceae |

Shangri-la and Deqin |

Young leaves |

eaten fresh |

Jun-Aug |

Roots used to remove blood stasis. |

* |

|

Ribes alpestre Wall. ex Decne. |

Suanmiguoguo |

Saxifragaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh and used to prepare local wine |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as fence and hedge plants. |

*** |

|

Ribes moupinense Franch. |

Hiangshen |

Saxifragaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh and used to prepare local wine |

Jul-Oct |

Leaves, stems and fruits used for weisang. Whole plants used as fence and hedge plants. |

*** |

|

Ribes glaciale Wall. |

Niangxu |

Saxifragaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Leaves and stems used for weisang. Whole plants used as fence and hedge plants. |

*** |

|

Rosa omeiensis Rolfe |

Xuwabala |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Jul-Sept |

Whole plants used as fence and ornamental. |

*** |

|

Rosa praelucens Byhouwer |

Xielermiedu |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Sept-Oct |

Flowers used for weisang. Whole plant used as ornamental. |

*** |

|

Rosa soulieana Crép. |

Xuwabala |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as fence and ornamental. |

** |

|

Rubus assamensis Focke |

Hongpai; Yongde |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as fence. |

** |

|

Rubus fockeanus Kurz |

Hongpai; Yongde |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as fence. |

* |

|

Rubus niveus Thunb. |

Hongpai; Yongde |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as fence. |

** |

|

Rubus pectinellus Maxim. |

Jiaoxumu |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Leaves and stems used for weisang. Whole plants used as fence. |

*** |

|

Rubus pentagonus Wall. ex Focke |

Hongpai; Yongde |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as fence. |

** |

|

Rubus polyodontus Hand.-Mazz. |

Hongpai; Yongde |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as fence. |

* |

|

Rubus rubrisetulosus Cardot |

Hongpai; Yongde |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as fence. |

** |

|

Rubus stans Focke |

Hongpai; Yongde |

Rosaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as fence. |

** |

|

Sageretia thea (Osbeck) M. C. Johnst. |

Luozi |

Rhamnaceae |

Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Apr-May |

|

* |

|

Sambucus chinensis Lindl. |

Debangqiongjie |

Caprifoliaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Jul-Sept |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

*** |

|

Schisandra rubriflora (Franch.) Rehder et E. H. Wilson |

Wuweizi |

Schisandraceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh and used to prepare local wine |

Aug-Oct |

Fruits used as antidiarrheic and for invigorating kidney. Whole plant used as ornamental. |

*** |

|

Sinopodophyllum hexandrum (Royle) T. S. Ying |

Agabule |

Berberidaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Jul-Sept |

Roots, stems and leaves used to clear heat. Seeds used to cure antenatal pain and help expelling placenta. Whole plant used as ornamental. |

** |

|

Spiranthes sinensis (Pers.) Ames |

Xiaobaiji |

Orchidaceae |

Shangri-la |

Whole plant |

stewed with meat and eaten as tonic |

Aug-Sept |

Whole plants used as fodder. |

* |

|

Stachys kouyangensis (Vaniot) Dunn var. franchetiana (H. Lév.) C. Y. Wu |

Riganlu |

Lamiaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Tubers |

boiled or stir-fried |

Jun-Sept |

Whole plants used as fodder. |

* |

|

Taraxacum mongolicum Hand.-Mazz. |

Yongma |

Asteraceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Whole plants |

boiled or stir-fried |

Jun-Aug |

Whole plants used as fodder. |

*** |

|

Taxillus chinensis (DC.) Danser |

Yawakeqi |

Loranthaceae |

Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Oct |

|

** |

|

Taxillus thibetensis (Lecomte) Danser |

Yawakeqi |

Loranthaceae |

Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Oct |

|

*** |

|

Thamnolia vermicularis Ach. |

Xiare |

Thamnoliaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Whole plant |

used for making tea, wine and beverage |

Aug-Oct |

Used to tranquilize mind and clear heat. |

* |

|

Thlaspi arvense L. |

Manlancai |

Brassicaceae |

Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried or used for making pickle |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

** |

|

Thlaspi arvense L. |

Manlancai |

Brassicaceae |

Weixi and Deqin |

Seeds |

used for making vegetable oil |

Jul-Aug |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

** |

|

Thlaspi yunnanense Franch. |

Manlancai |

Brassicaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried or used for making pickle. |

May-Jun |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

** |

|

Thlaspi yunnanense Franch. |

Manlancai |

Brassicaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Seeds |

used for making vegetable oil |

Jul-Aug |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

** |

|

Tibetia himalaica (Baker) H. P. Tsui |

|

Fabaceae |

Deqin, Shangri-la |

Roots |

eaten fresh |

Jun-Aug |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

* |

|

Toona sinensis (Juss.) Roem. |

|

Meliaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Leaf buds |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

May-Jun |

|

** |

|

Torreya fargesii Franch. var. yunnanensis (C. Y. Cheng et L. K. Fu) N. Kang |

Shasongguo |

Taxaceae |

Weixi, Shangri-la |

seeds |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

Sept-Oct |

Leaves and stems used for weisang. Plants used as fuel-wood. |

* |

|

Toxicodendron succedaneum (L.) Kuntze |

Si |

Anacardiaceae |

Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

used for making vegetable oil |

Jul-Sept |

Wax is extracted from fruits to use in varnish and polish. |

* |

|

Toxicodendron vernicifluum (Stokes) F. A. Barkley |

Si |

Anacardiaceae |

Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

used for making vegetable oil |

Jul-Sept |

Wax is extracted from fruits for using in varnish and polish. |

* |

|

Triosteum himalayanum Wall. |

Sachi |

Caprifoliaceae |

Shangri-la |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Aug-Sept |

Aerial parts used as fodder. |

* |

|

Typhonium diversifolium Wall. ex Schott |

Banxia |

Araceae |

Shangri-la |

Young leaves |

used for making pickle |

Jul-Aug |

|

** |

|

Urtica fissa E. Pritz. |

Yanglala |

Urticaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried |

Jun-Jul |

|

** |

|

Urtica mairei H. Lév. |

Yanglala |

Urticaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

stir-fried |

Jun-Jul |

|

** |

|

Viburnum betulifolium Batalin |

Ruosi |

Caprifoliaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh and used to prepare local tonic wine |

Aug-Sept |

|

* |

|

Viburnum kansuense Batalin |

Ruosi |

Caprifoliaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh and used to prepare local tonic wine |

Aug-Sept |

|

* |

|

Vitis betulifolia Diels et Gilg |

Geng |

Vitaceae |

Weixi and Deqin |

Fruits |

eaten fresh |

Jul-Oct |

Leaves used as fodder. |

** |

|

Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim. |

Yemu |

Rutaceae |

Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin |

Young stems and leaves |

eaten fresh or stir-fried |

Apr-May |

|

**** |

| Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim. | Yemu | Rutaceae | Shangri-la, Weixi and Deqin | Fruits | used as spices | Jul-Sept | ***** |

Frequency: ***** > 75% of respondents; **** > 50% of respondents; *** > 1/4 of respondents; ** > 1/8 of respondents; * < 1/8 of respondents, but at least 2 respondents.

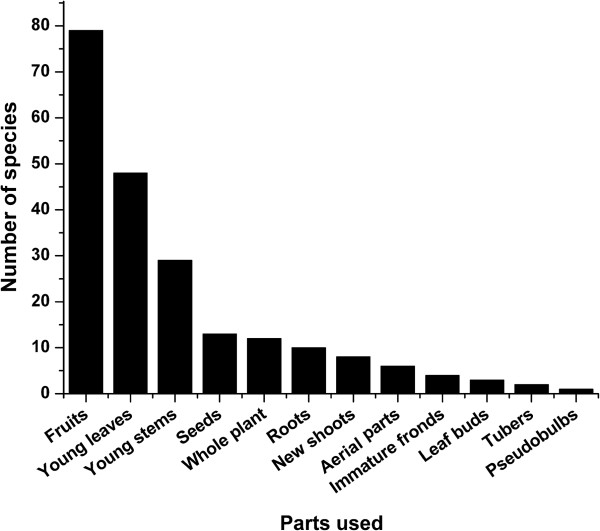

The most frequently used parts are fruits, young leaves and stems (Figure 2). This result is similar to other investigations, such as a study of the Shuhi people in the Hengduan Mountains (southwest China) [24], studies in Xishuangbanna, southern Yunnan (China) [26,28] and surveys among Inner Mongolian herdsmen [18]. The preference for wild collected leafy vegetables and fruits over underground plant parts seems to be common among diverse ethnic groups in China and the Himalayan area, and might be due to the ease of collecting above ground parts [24]. Collection period varies from April to August (for young leaves and stems) and July to October (for fruits and seeds). Most plant parts are collected in summer and autumn (Table 3). These plants are often dried in the sun after collection and stored (a very common preserving technique [22]) until winter. Most uses are specific to a particular plant part (such as young leaf, new shoot or ripe fruit), although in a few cases a single plant part has different uses, e.g., seeds of Juglans regia are eaten fresh or used to make vegetable oil. More than one plant part is used for about 7% of the species. For example, young leaves and stems of Panax japonicus var. major are used as a vegetable, while rhizomes are stewed with meat and eaten as a tonic. Leaves of Thlaspi yunnanense are used as a vegetable, while vegetable oil is made from the seeds. Young leaves, stems and fruits of Berberis amoena, B. jamesiana, B. pruinosa and B. eisiensis are eaten fresh. Young stems and leaves of Zanthoxylum bungeanum are boiled or stir-fried, and the fruits as a condiment. Fruits of Berchemia hirtella and B. sinica are eaten fresh and the young leaves to make tea. In total, vegetable (41.9%) is the most used category followed by fruit (40.8%) (Table 4). Ripe fruits are often eaten fresh, green leafy vegetative parts (e.g., young leaves and stems) are usually boiled or stir-fried, less commonly they are eaten fresh as salad or added to soups. All these plants are used as ingredients for the hot pot, since Tibetans in this region like hot pot very much.

Figure 2.

Use frequency of wild edible plant parts of species used by Tibetans in the Shangri-la region, Yunnan, China.

Table 4.

Specific edible uses of wild edible plants used by Tibetans in Shangri-la region, Yunnan, China

| Specific use | Number of plants |

|---|---|

| vegetable |

80 |

| fruit |

78 |

| wine |

11 |

| vegetable oil |

9 |

| spice |

8 |

| tea |

5 |

| Total | 191 |

These wild edible plants play an important role in providing local Tibetans with various vital nutrition elements, such as vitamins and minerals needed to maintain health and promote immunity against disease. For example, butter rice with ginseng fruits is a famous and traditional Tibetan dish. Ginseng fruits are the roots of Potentilla anserina, a perennial herb, and was reported to have low fat, high dietary fiber, all essential amino acids, various mineral elements and vitamins [41]. Other wild vegetables and fruits frequently used by local Tibetans include Maianthemum atropurpureum, Allium ovalifolium, Aralia chinensis, Hippophae rhamnoides subsp. yunnanensis and Amygdalus mira, which are all mentioned by nearly every respondent.

Multiple uses of wild edible plants

In addition to edible use, 71.4% of the reported wild edible plants (120 species) have additional uses (Tables 3 and 5). Such species are common in rural areas and are important to local people [12,42]. They not only balance the nutritional value of starchy diets (compensating for lack of several vitamins, proteins and minerals), but may also provide pharmacologically active compounds. The multiple uses attest to the importance of these plants for subsistence and as a part of local cultural heritage [12]. Thirty-one species (18.5%) are also used as medicine, most are herbs (19 species) or trees (6 species). These medicinal plants are used to treat gastropathy, cough, fever, rheumatism, dysentery, fractures, dyspepsia, hemoptysis, and asthma. For a few species, the same part is not only used as food, but is also used for medicinal purposes. For example, the roots of Anemone rivularis are stewed with meat and eaten as tonic by local people, and the decoction of them are used to treat bronchitis.

Table 5.

Types of multiple uses for edible wild plants utilized by Tibetans in Shangri-la region, Yunnan, China

| Kind of usage | Number of species | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Edible |

168 |

100.0 |

| Fodder |

52 |

31.0 |

| Medicinal |

31 |

18.5 |

| Fence |

22 |

13.1 |

| Ornamental |

11 |

6.5 |

|

Weisanga |

10 |

6.0 |

| Fuel-wood |

9 |

5.4 |

| Construction | 4 | 2.4 |

aThe religious rite of burning offerings for smoke, which plays an important role in local Tibetan’s daily life.

WEPs can provide resources for future exploitation of new health foods. As living standards improve, there is a globally increased demand for healthy and safe food [21]. Compared to conventional, cultivated vegetables, wild food plants require less care, are not affected by pesticide pollution, and are a rich source of micronutrients.

However destructive harvesting is a significant concern and in the present study this was documented to occur in at least 21 species used for medicine, the underground parts (root, tuber and corm) of fourteen species and the whole plant of seven species. This manner of harvest may have a serious consequence from both the survival of plants and from an ecological point of view [43]. The conservation and sustainable utilization of species with multiple uses should be taken into consideration.

Fifty-two species (31%) were used as fodder. For example Potentilla coriandrifolia var. dumosa is regarded as high-quality forage at high altitude (3500–4300 m). Further study of its nutrient composition can be done in order to understand the rationale for its usage and development potential.

Ten species have cultural significance in a religious rite named weisang, during which specific plants are burned for smoke. These are Adenophora khasiana, Aralia chinensis, Cerasus conadenia, Pinus armandii, Pistacia weinmanniifolia, Ribes moupinense, Ribes glaciale, Rosa praelucens, Rubus pectinellus and Torreya fargesii var. yunnanensis. This rite plays an important role in Tibetans’ daily life, and it is said that the fragrance in the smoke can not only make the mountain god pleased, but also wash dirty things away from people. Tibetans pray for good harvest, good fortune, happiness and prosperity in this manner.

“Most preferred” species and their commercial potential

Besides food value, the recorded species provide the possibility to supplement household income of rural people with limited cash income opportunities [44]. In our survey, the most preferred plants (mentioned by more than 50% of respondents) include Maianthemum, Allium, Aralia, Arundinaria faberi, Fargesia melanostachys, Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusclum, Matteuccia struthiopteris, Zanthoxylum bungeanum, Ligusticum daucoides, Hippophae rhamnoides subsp. yunnanensis and Pistacia weinmanniifolia. All these plants are collected from remote mountains by local people and traded in local markets, which provides the possibility to increase the income of rural people with low cash income.

Maianthemum species (zhuyecai or “bamboo-leaved vegetable”) are the most frequently mentioned wild vegetable. In Diqing Prefecture, the leaves of six species are eaten (M. atropurpureum, M. forrestii, M. henryi, M. oleraceum, M. purpureum and M. tatsienense). They are added to soups, stir-fried with bacon or eaten raw as salad. Several studies have focused on the nutritional analysis of zhuyecai and found they contained higher amount of protein, essential amino acids, vitamin C and mineral elements compared with some common vegetables [45-47]. Although local people do not use them as medicine, Maianthemum species were reported for medicinal use since ancient times. For instance, M. japonica and M. henryi are employed to treat kidney diseases, activate blood circulation and alleviate pain [44,48]. M. atropurpurea contains a variety of steroidal saponins and nucleosides which may possess anti-tumor activities [49-51]. Three new steroidal saponins having cytotoxic properties against human cancer cells were isolated from M. japonica[52]. Zhuyecai also has commercial value. In the market the price varied from 12 CNY (Chinese yuan) to 40 CNY (ca. 1 USD = 6.5 CNY) per kilogram (fresh weight) from April to June, an important source of cash income. And in restaurants, one dish (prepared from about 500 g) costs 18–38 CNY during another season.

Another renowned edible plant, shutoucai, includes two species, Aralia caesia and A. chinensis. Leaf buds and young leaves are edible and are collected from April to May. Researchers have reported that the tender shoots of A. chinensis contain many oleanolic acids and seven essential amino acids [53]. One local company intends to exploit this wild vegetable commercially. Hippophae rhamnoides subsp. yunnanensis, endemic to the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, has both food and medicinal values. Its fruits are eaten fresh or used to make beverage and wine, and also used to treat cough and invigorate the circulation of blood.

In the present study, we found that taste is the first criterion for all types of food plants, in agreement with other surveys [54]. However, taste itself is not strong enough to construct a reliable priority list for future conservation, domestication and exploitation. Further detailed nutrition analysis and phytochemical investigation should be undertaken to comprehensively evaluate food and medicinal value of these “most preferred” plants, which could provide scientific and important information.

It is generally believed that local people are more likely to support and participate in conservation initiatives if they can receive direct benefits from such efforts [55]. If managed sustainably, these plants could be a good means of income generation for rural communities. Market surveys, value chain analyses and the risk of overexploitation should be assessed thoroughly [13,56]. Maianthemum populations (zhuyecai) are becoming rare in Shangri-la County although there were rich resources 20 years ago. Uprooting and harvesting the entire plant during collection were observed and identified as causes of decline for Sinopodophyllum hexandrum, Aristolochia delavayi, Megacarpaea delavayi and Codonopsis pilosula var. handeliana. Because few people in this area are aware of sustainable harvesting, the conservation and proper utilization of these species should be taught.

Crop wild relatives for genetic improvement and crop production

Crop wild relatives (CWRs) are species that are closely related to crops including crop progenitors. These wild relatives of domesticated crops may provide genes having higher resistance to adverse circumstance that could prove particularly important in response to global climate change, which will undoubtedly alter the environmental conditions under which our crops grow and dramatically impact agriculture [4,57,58]. CWRs are also of great importance to maintain the productivity and stability of traditional agro-ecosystems [59,60]. Conservation of these species ensures that diverse genetic resources are preserved and could be used in the improvement of crops as a contribution to 21st century food security [4,7,8]. The main options for CWRs conservation are ex situ in gene banks and in situ in the natural or farmed environment [59,61,62]. It is widely recognized that in situ is necessary to conserve the full range of genetic diversity inherent in and between plant populations, with ex situ techniques as a backup [58]. Taxon inventory is the starting point for in situ conservation which provides the baseline data critical for biodiversity assessment and monitoring [63]. Some of the wild relatives of fruit, vegetable and spice crops documented in this study are species of Actinidia, Allium, Amaranthus, Amygdalus, Arctium, Armeniaca, Capsella, Cerasus, Crataegus, Dioscorea, Diospyros, Eriobotrya, Foeniculum, Fragaria, Hippophae, Juglans, Malus, Mentha, Pyrus, Toona, Vitis and Zanthoxylum. Take Amygdalus mira as an example. Due to its advantageous traits, such as high adaptability and longevity, resistance to disease and tolerance to drought and cold, it could be a genetic resource for peach improvement. Another case is Pyrus betulifolia, which is usually used as stock to graft various pear cultivars. It is drought resistant, cold tolerant and long living, making it a good candidate for providing useful genes to improve the quality of pears. Young leaves of Allium ovalifolium could be eaten as vegetables, and leaves are relatively larger than those of other Chinese chives. Thus, it might be used as a source for breeding new variety of chives. Two other species, Rosa omeiensis and R. praelucens have edible and ornamental uses and exhibit high cold tolerance. They may provide beneficial genes for future study and exploitation in developing new crops.

Issues of conservation

Wild edible plant species are threatened by various natural causes and human activities [4,34]. Extreme weather caused by global climate change, such as heavy snow and severe droughts, has resulted in the decrease and even loss of many wild food plant populations. Various human activities such as land use change, habitat destruction, over-harvesting and over-grazing, are major threats. In recent years, with the construction of roads, airports, reservoirs and other infrastructure, wild habitats for edible plants were severely impacted. Unsustainable harvesting of food plant species with good market price also contributes to a decrease of these plants.

Threats are not only limited to wild food plants themselves, the traditional knowledge associated with WEPs is also endangered. Therefore, systematic documentation of indigenous knowledge and biological resources is of great significance [55,64]. Along with economic development and increasing income, only a few people want to collect wild edible plants. The younger generation is becoming less interested in them, thus causing the loss of traditional knowledge. In Shangri-la County tourism is booming and local people eagerly want to serve as guides or drivers in tourist areas to pursue more money. With the convenience of transportation, residents can buy much more vegetables from the markets than ever before and do not need to collect wild species. However, in more remote rural communities where transportation is still inconvenient and people seldom go to the market, indigenous knowledge about WEPs is relatively intact. In Deqin County much land has been converted to grape cultivation to develop a wine industry and agricultural chemicals are used frequently, causing the decrease of various wild edible species, and even cultivation of the very important species, hull-less barley, Hordeum vulgare, the staple food of Tibetan communities [65,66] is threatened. During our survey we found that most people are reluctant to cultivate hull-less barley now because planting grapes can bring more cash income.

Conclusion

This paper is the first ethnobotanical study of wild food plants used by local Tibetans in Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. As plant resources in this area are rather plentiful, and under the influence of other ethnic groups, local Tibetans not only cultivate various crops, but also collect wild edible plants as food. Our survey showed the diversity of WEPs and related indigenous knowledge in this area.

Different parts of plants are used by local people, and the most frequently used parts were fruits, young leaves and stems. These plants have different specific food uses, with leafy vegetable uses being most frequent, followed by fruit uses. WEPs provide food and nutrients to local communities, such as essential amino acids, various vitamins and minerals which are needed to keep healthy and enhance immunity against diseases and infections.

If properly harvested, WEPs could be the source of cash income for local people with low cash income because they are enjoyed by local people very much and often traded in markets. Furthermore, with the increased demand for green, healthy and safe food in modern society, wild food resources have attracted global interest because they are pollution-free and contain numerous important micronutrients and pharmacologically active substances. In order to properly utilize the wild food resources, we have some suggestions: 1) properly exploit and improve conservation and management of wild food plants; 2) focus on scientific research on wild food resources; 3) protect the natural environment and habitat for wild food plants.

In addition to food value, more than 50% of recorded plants have medicinal, ornamental, and cultural and other uses that are important in local Tibetan culture. Furthermore, some are crop wild relatives and could provide useful genes for crop improvement, which may have significant consequence on global food security. However, along with the development of economy, these multi-valued resources are threatened by human activities and natural causes, and associated traditional knowledge is eroding rapidly. Therefore, sustainable management of these resources as well as conserving biodiversity is of the utmost importance.

In a word, our ethnobotanical surveys provide data and information basis for conservation and sustainable utilization of local wild edible plants, and also contribute to preserve cultural and genetic diversity in Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CLL designed the study. YJ, BL and JXZ performed the field survey. YJ drafted the manuscript, BL revised the manuscript. CLL revised and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yan Ju, Email: juyanmuc@163.com.

Jingxian Zhuo, Email: 339689934@qq.com.

Bo Liu, Email: liubo.leo@gmail.com.

Chunlin Long, Email: chunlinlong@hotmail.com.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the local people for their assistances in the field investigations and for sharing their valuable knowledge. Dr. Kendrick Marr from the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria, BC, Canada, kindly helped to edit the English and provided professional comments. We are very grateful to his assistances. Members of Ethnobotanical Laboratory at Minzu University of China, and Research Group of Ethnobotany at Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, participated in the field work and discussion. This research was funded by the National Science Foundation of China (31161140345), the Ministry of Education of China through its 111 and 985 projects (B08044, MUC98506-01000101 & MUC985-9), and the Asian COPE Program of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS/AP/109080).

References

- Lulekal E, Asfaw Z, Kelbessa E, Van Damme P. Wild edible plants in Ethiopia: a review on their potential to combat food insecurity. Africa Focus. 2011;24:71–121. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood VH. Ethnopharmacology, food production, nutrition and biodiversity conservation: towards a sustainable future for indigenous peoples. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal T. Evaluation of nutritional potential of wild edible plants, traditionally used by the tribal people of Meghalaya state in India. Amer J Plant Nutr Fertil Tech. 2012;2:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Uprety Y, Poudel R, Shrestha K, Rajbhandary S, Tiwari N, Shrestha U, Asselin H. Diversity of use and local knowledge of wild edible plant resources in Nepal. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2012;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani A, Langenberger G, Sauerborn J. A comparison of the wild food plant use knowledge of ethnic minorities in Naban River Watershed National Nature Reserve, Yunnan, SW China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2012;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez-Baceta G, Aceituno-Mata L, Tardío J, Reyes-García V, Pardo-de-Santayana M. Wild edible plants traditionally gathered in Gorbeialdea (Biscay, Basque Country) Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2012;59:1329–1347. doi: 10.1007/s10722-011-9760-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Lloyd BV, Schmidt M, Armstrong SJ, Barazani O, Engels J, Ge S, Hadas R, Hammer K, Kell SP, Kang D, Khoshbakht K, Li Y, Long CL, Lu BR, Ma KP, Nguyen VT, Qiu LJ, Wei W, Zhang ZW, Maxted N. Crop wild relatives-undervalued, underutilized and under threat? BioScience. 2011;61:559–565. doi: 10.1525/bio.2011.61.7.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A, Tomer AK, Bhandari DC, Pareek SK. Towards collection of wild relatives of crop plants in India. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2008;55:187–202. doi: 10.1007/s10722-007-9227-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Misra S, Maikhuri R, Kala C, Rao K, Saxena K. Wild leafy vegetables: A study of their subsistence dietetic support to the inhabitants of Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, India. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2008;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas P, Scarpa GF. Edible wild plants of the chorote Indians, Gran Chaco, Argentina. Bot J Linn Soc. 2007;153:73–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2007.00576.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi N, Kehlenbeck K, Maass BL. Traditional, neglected vegetables of Nepal: Their sustainable utilization for meeting human needs. 2007. pp. 1–10. (Conference on International Agricultural Research for Development, Tropentag).

- Shrestha PM, Dhillion SS. Diversity and traditional knowledge concerning wild food species in a locally managed forest in Nepal. Agroforest Syst. 2006;66:55–63. doi: 10.1007/s10457-005-6642-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Termote C, Van Damme P, Dhed’a Djailo B. Eating from the wild: Turumbu, Mbole and Bali traditional knowledge on non-cultivated edible plants, District Tshopo, DR Congo. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2011;58:585–618. doi: 10.1007/s10722-010-9602-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keller GB, Mndiga H, Maass BL. Diversity and genetic erosion of traditional vegetables in Tanzania from the farmer’s point of view. Plant Genet Resour Charact Util. 2005;3:400–413. doi: 10.1079/PGR200594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tardío J, Pardi-De-Santayana M, Morales R. Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants in Spain. Bot J Linn Soc. 2006;152:27–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2006.00549.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]