Abstract

Objective

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes involved in fatty acid metabolism (FADS1 FADS2 gene cluster) are associated with plasma lipid levels. We aimed to investigate whether these associations are already present early in life and compare the relative contribution of FADS SNPs vs traditional (non-genetic) factors as determinants of plasma lipid levels.

Methods

Information on infants’ plasma total cholesterol levels, genotypes of five FADS SNPs (rs174545, rs174546, rs174556, rs174561, and rs3834458), anthropometric data, maternal characteristics, and breastfeeding history was available for 521 2-year-old children from the KOALA Birth Cohort Study. For 295 of these 521 children, plasma HDLc and non-HDLc levels were also known. Multivariable linear regression analysis was used to study the associations of genetic and non-genetic determinants with cholesterol levels.

Results

All FADS SNPs were significantly associated with total cholesterol levels. Heterozygous and homozygous for the minor allele children had about 4% and 8% lower total cholesterol levels than major allele homozygotes. In addition, homozygous for the minor allele children had about 7% lower HDLc levels. This difference reached significance for the SNPs rs174546 and rs3834458. The associations went in the same direction for non-HDLc, but statistical significance was not reached. The percentage of total variance of total cholesterol levels explained by FADS SNPs was relatively low (lower than 3%) but of the same order as that explained by gender and the non-genetic determinants together.

Conclusions

FADS SNPs are associated with plasma total cholesterol and HDLc levels in preschool children. This brings a new piece of evidence to explain how blood lipid levels may track from childhood to adulthood. Moreover, the finding that these SNPs explain a similar amount of variance in total cholesterol levels as the non-genetic determinants studied reveals the potential importance of investigating the effects of genetic variations in early life.

Introduction

Elevated total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLc), and very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, and low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLc) levels early in life play a role in the development of adult atherosclerosis, one of the major risk factors of coronary artery disease [1]. This may be partly explained by the fact that plasma lipid levels track from childhood into adulthood [2]–[4], and correlate with the extent of fatty streaks in early life (early atherosclerotic lesions which may progress to advanced atherosclerotic lesions and coronary artery disease) [1], [5]. Therefore, the understanding and control of determinants of plasma lipid levels in childhood is of utmost importance. With such aim in mind, several studies have identified significant associations between maternal anthropometric characteristics and lifestyle [6], and children’s characteristics such as gender [7]–[9], anthropometric characteristic [7], [9], early diet [8], [10], [11], and breastfeeding [12], with children’s plasma lipid levels. Genetic determinants appear to be relevant as well. At least in adults, many single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), each with modest effects, have been found to explain part of the inter-individual variability in plasma lipid levels [13]–[16].

We and others demonstrated that SNPs in the genes coding for the fatty acid desaturases 5 and 6 (FADS1 FADS2 gene cluster) are associated with the proportions of the various polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in adults’ blood and tissues [17], [18] and in plasma phospholipids of 2-year-old infants [19]. As expected, FADS SNPs also showed associations with cardiovascular-related outcomes influenced by PUFAs such as the risk of type 2 diabetes [20], [21], coronary artery disease [22], myocardial infarction [23], and metabolic syndrome [24]. In addition, FADS SNPs were found to be associated with intermediate phenotypes such as serum or plasma lipid levels in adults and adolescents [13]–[16], [22], [23], [25]–[34]. Recently, Standl et al. showed that the associations between FADS SNPs and blood lipid levels are already present in 10-year-old children [35], which raises the question as to whether such associations can be detected even earlier in life.

In the present study we investigated: 1) whether FADS SNPs were associated with TC, HDLc, and non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (nHDLc) levels in 2-year old infants, and 2) the contribution of FADS SNPs in determining plasma lipid levels compared to traditional (non-genetic) determinants.

Methods

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Maastricht University/University Hospital Maastricht. All parents gave written informed consent.

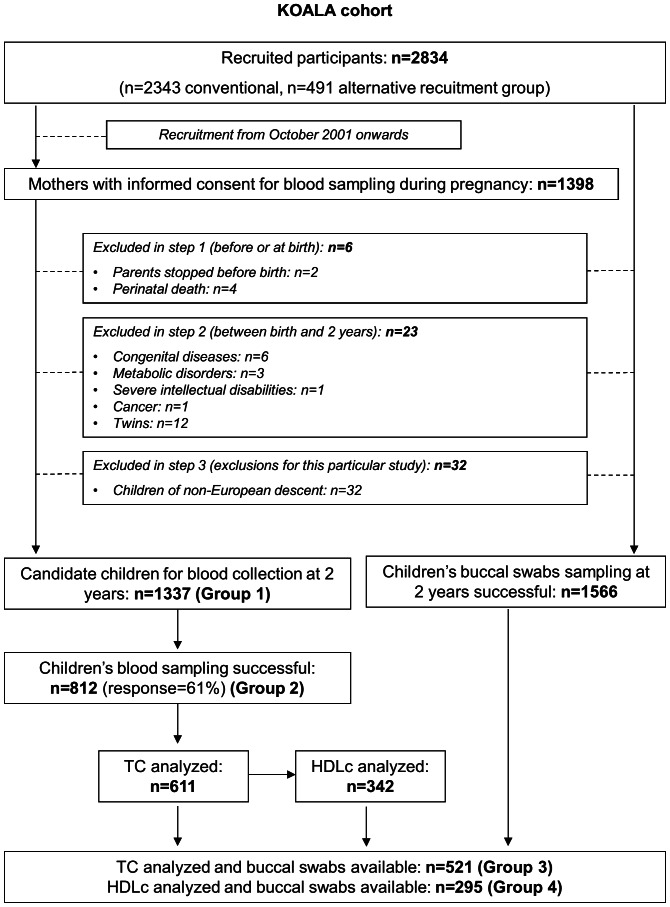

CohortThe details of the cohort have been described elsewhere [36]. In summary, the KOALA Birth Cohort Study is a prospective birth cohort in the center and South of the Netherlands. The recruitment of pregnant women started in 2000. Between 2000 and 2002, healthy pregnant women participating in the Pregnancy related Pelvic Girdle Pain Study (PPBS, n = 7526) [37] were invited to participate with their child in the KOALA study. Most women recruited by this means had a conventional lifestyle in terms of diet and child rearing practices. Additional pregnant women with alternative lifestyles were recruited from 2001 to 2002 through organic food shops, anthroposophic doctors and midwives, and Steiner schools. In total, 2834 women were recruited (n = 2343 conventional recruitment group; n = 491 alternative recruitment group) ( figure 1 ). Women recruited from 2001 onwards were asked to consent to blood sampling in pregnancy. When children were 2 years of age, parents were asked to consent to children’s collection of buccal swabs and, if maternal consent for blood collection in pregnancy was available, also to children’s blood sampling (eligible children after exclusions, n = 1337). Buccal swabs and blood were successfully collected in 1566 and 812 children, respectively. Due to limited volume of plasma available, TC and HDLc levels were determined in 611 and 342 children, respectively, out of the 812 with blood sampled.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the study design and participant selection.

Exclusion criteria were: withdrawal from the study before child’s birth, perinatal death, severe congenital diseases, metabolic disorders, severe intellectual disabilities, cancer, and twins. For this study, children of non-European ancestry were also excluded, as blood lipid metabolism may be affected by ethnicity [38] and the minor allele frequency of FADS SNPs differs between ethnic groups [39]. Children’s ancestry was assessed by using information about the country of birth of grandparents, collected through questionnaires filled out by both parents. Children were considered to be of European descent when at least three of their grandparents were born in countries of predominant European ancestry.

The final study population consisted of 521 children with TC analyzed and buccal swabs available, from which 295 children also had HDLc analyzed.

Plasma Lipids

Non-fasting blood samples were collected in EDTA-tubes by trained nurses, according to a standardized protocol, during a home visit to the child around age 2 years. After centrifugation, the EDTA-plasma was stored in cryovials at −80°C. TC and HDLc were analyzed on an autoanalyser (LX20 Pro, Beckman Coulter, Mijdrecht, The Netherlands) with two kits from Beckman Coulter: Enzymatic method, nr. CHOL 467825 for TC and HDLD kit, nr 650207 for HDLc. nHDLc was calculated as the difference between TC and HDLc.

DNA Isolation and SNP Genotyping

The DNA isolation and SNP selection and genotyping have been described in detail elsewhere [19]. In short, genomic DNA was extracted from buccal swabs using standard methods [40], and afterwards amplified by using REPLI-g UltraFast technology (Qiagen™) as reported before [41]. Five variants of the FADS1 FADS2 gene cluster (rs174545, rs174546, rs174556, rs174561, and rs3834458) were typed. These variants are associated with the proportions of PUFAs in serum and plasma phospholipids and erythrocytes’ membranes from adults [42]–[44] and children [19]. Additionally, the SNPs rs174545, rs174546, and rs174556 were estimated to tag up to 21 SNPs between basepair positions 61300075 and 61379716 of FADS1 FADS2, by using the Tagger tool (http://www.broad.mit.edu/mpg/tagger [45]) with HapMap release 21 data. Genotyping was performed with the iPLEX method (Sequenom, San Diego, CA, USA) by Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time Of Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS, Mass Array; Sequenom).

Maternal and Children’s Information

Information on potential non-genetic determinants of children’s plasma lipids and possible confounders was retrieved from obstetric reports and questionnaires filled out at different time points during pregnancy and the first two years of children’s life ( table 1 ). Maternal and children’s BMIs were calculated as kg/m2. In order to standardize children’s BMI for gender and actual age of measurement (which could slightly differ among children), measurements were converted to standard deviation scores (z-scores) using data from the Dutch reference population as the standard [46].

Table 1. Maternal and children’s non-genetic potential determinants of blood lipids, possible confounders, and data source.

| Maternal information | Source | |

| Determinants | Maternal age at delivery | Q*+obstetric report |

| Smoking habits during pregnancy | Q at 14 and 30 wk pregnancy | |

| Alcohol intake during pregnancy | Q at 14 and 30 wk pregnancy | |

| Weight and height before pregnancy | Q at 14 and 30 wk pregnancy | |

| Pregnancy weight gain | Q at 2 wk post-partum | |

| Parity before index pregnancy | Q at 30 wk pregnancy | |

| Confounders | Maternal education | Q at 14 wk pregnancy |

| Recruitment group | Recorded at the time of recruitment | |

| Children’s information | Source | |

| Determinants | Gender | Q+obstetric report |

| Gestational age at delivery | Q at 2 wk post-partum | |

| Birth weight | Obstetric report | |

| Weight and height at 2 years | Q at 2 years post-partum | |

| Breastfeeding duration | Q at 2 wk, 3, 6, 7, 12, and 22 mo post-partum | |

| Confounders | Age at blood collection | Recorded at the time of blood collection |

Q stands for “questionnaire”.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed with PASW Statistics 18. Agreement of the genotype frequencies with Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium expectations was tested by chi-square test. Normality of blood lipids was checked by means of histograms and Q-Q-plots.

Associations of genetic and non-genetic determinants with plasma lipid levels were examined in multivariable linear regression models ( table 2 ). The associations between FADS genotypes and plasma lipids were tested in model 1 assuming a co-dominant genetic model. Statistical significance was defined by a two-sided alpha level of 5%. Correction for multiple testing was performed by the method proposed by Nyholt [47]. In brief, this method takes into account the correlation pattern between the SNPs and reduces the number of variables in a set to the effective number of variables, which is an estimate of the number of independent tests. We divided the alpha level of 5% by the effective number of independent SNPs (1.26 in our case), yielding a significance threshold of 0.040 required to keep Type I error rate at 5%.

Table 2. Variables included in each of the seven examined linear regression models.

| Potential determinants of blood lipids included in the models | Regression models nr.* | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| FADS SNPs | x | x | |||||

| Gender | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Maternal alcohol intake during pregnancy | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Maternal age at delivery | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Parity before the index pregnancy | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Pregnancy weight gain | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Gestational age at delivery | x | x | x | x | |||

| Breastfeeding duration | x | x | x | ||||

| Birth weight | x | x | |||||

Recruitment group and age of blood collection were adjusted for in all models, and maternal education was adjusted for in models 2 to 7.

To test the associations of non-genetic determinants and gender with plasma lipid levels, we started with model 2 ( table 2 ) which included gender, maternal smoking and alcohol intake during pregnancy, maternal age at delivery, prepregnancy BMI, and parity. Subsequently, we built models 3, 4, 5, and 6 by successively adding the determinants pregnancy weight gain, gestational age at delivery, breastfeeding duration, and birth weight. This allowed us to check the absence of overadjustment bias in the final model 6. Such bias could exist when including in a model intermediate variables on a causal pathway from exposure to outcome [48] (e.g. if birth weight would mediate the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and children’s plasma lipid levels, the inclusion of the former in a model already including maternal smoking could bias the results). Finally, we built model 7, including both genetic and non-genetic determinants. As plasma lipid levels may be differently modulated in boys and girls, and some SNPs have been found to exert different effects according to gender [49], the genotype-gender interaction was also tested in this model.

For handling missing data in continuous determinants ( table 3 ), we first performed the Little’s Missing Completely at Random test [50], which showed that missing data did not deviate from the “missing completely at random” assumption. Secondly, we imputed missing values through the expectation maximization algorithm using information on maternal age, education, smoking during pregnancy, alcohol intake during pregnancy, gestational age, pre-pregnancy BMI, pregnancy weight gain, birth weight, and child’s gender. Missing values in categorical variables ( table 4 ) were coded as a new category. Cases with missing data for SNPs were excluded from the analyses involving that particular SNP.

Table 3. Representativeness of the study participants regarding continuous variables.

| Group 1 (n = 1337)* | Group 2 (n = 812)* | Group 3 (n = 521)* | Group 4 (n = 295)* | |||||||||

| n# | Mean | SD | n# | Mean | SD | n# | Mean | SD | n# | Mean | SD | |

| Maternal age at delivery (years) | 1320 | 32,54 | 3,80 | 807 | 32,80 | 3,82 | 516 | 32,90 | 3,81 | 292 | 32,82 | 3,62 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 1316 | 39,7 | 1,2 | 805 | 39,6 | 1,2 | 516 | 39,7 | 1,2 | 292 | 39,7 | 1,1 |

| Maternal pre-pregnancy height (cm) | 1336 | 170,01 | 6,37 | 812 | 170,01 | 6,40 | 521 | 170,15 | 6,36 | 295 | 170,08 | 6,02 |

| Maternal pre-pregnancy weight (kg) | 1332 | 67,68 | 11,65 | 809 | 67,95 | 11,53 | 519 | 68,32 | 11,26 | 293 | 68,09 | 10,59 |

| Maternal weight gain pregnancy (kg) | 1241 | 14,32 | 5,01 | 761 | 14,08 | 4,79 | 490 | 14,10 | 4,78 | 281 | 14,39 | 4,69 |

| Breastfeeding duration (months) | 1327 | 5,7 | 4,4 | 812 | 5,7 | 4,4 | 521 | 5,9 | 4,4 | 295 | 5,8 | 4,5 |

| Total cholesterol child (mmol/L) | NA | NA | NA | 611 | 3,80 | 0,63 | 521 | 3,80 | 0,62 | 295 | 3,85 | 0,62 |

| HDL cholesterol child (mmol/L) | NA | NA | NA | 342 | 1,01 | 0,22 | 295 | 1,01 | 0,22 | 295 | 1,01 | 0,22 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol child (mmol/L) | NA | NA | NA | 342 | 2,84 | 0,63 | 295 | 2,84 | 0,63 | 295 | 2,84 | 0,63 |

| Birth weight (g) | 1330 | 3556 | 476 | 812 | 3562 | 482 | 521 | 3579 | 456 | 295 | 3593 | 469 |

| Weight at 2 years (z-score) | 1169 | −0,13 | 0,96 | 765 | −0,16 | 0,95 | 497 | −0,14 | 0,94 | 276 | −0,05 | 0,93 |

| Length at 2 years (z-score) | 1161 | −0,12 | 1,07 | 758 | −0,14 | 1,06 | 494 | −0,08 | 1,05 | 277 | −0,01 | 1,02 |

| BMI at 2 years (z-score) | 1150 | −0,01 | 1,02 | 754 | −0,04 | 1,00 | 491 | −0,07 | 1,02 | 275 | −0,02 | 0,98 |

Groups agree with those defined in Figure 1: group 1 = children candidate for blood collection; group 2 = children with blood sampling successful; group 3 = children with total cholesterol analyzed and genotypes available; group 4 = children with total cholesterol and HDLc analyzed and genotypes available.

May differ from the total due to missing values.

Table 4. Representativeness of the study participants regarding categorical variables.

| Variable | Categories | Group 1 (n = 1337)* | Group 2 (n = 812)* | Group 3 (n = 521)* | Group 4 (n = 295)* | ||||

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | ||

| Sex | Boys | 679 | 50,8 | 424 | 52,2 | 261 | 50,1 | 147 | 49,8 |

| Girls | 658 | 49,2 | 388 | 47,8 | 260 | 49,9 | 148 | 50,2 | |

| Maternal education | Primary school or lower vocational | 41 | 3,1 | 27 | 3,4 | 19 | 3,7 | 8 | 2,7 |

| Secondary school or middle vocational | 561 | 42,9 | 337 | 42,1 | 208 | 40,5 | 132 | 45,4 | |

| Higher vocational, or university degreeor higher | 707 | 54,0 | 437 | 54,6 | 287 | 55,8 | 151 | 51,9 | |

| Missings | 28 | – | 11 | – | 7 | – | 4 | – | |

| Maternalsmoking at any | No | 1244 | 94,4 | 764 | 94,9 | 497 | 96,7 | 280 | 96,6 |

| time during pregnancy | Yes | 74 | 5,6 | 41 | 5,1 | 17 | 3,3 | 10 | 3,4 |

| Missings | 19 | – | 7 | – | 7 | – | 5 | – | |

| Alcohol intake during | No | 1072 | 81,2 | 654 | 81,0 | 431 | 83,5 | 238 | 81,5 |

| pregnancy | Yes | 248 | 18,8 | 153 | 19,0 | 85 | 16,5 | 54 | 18,5 |

| Missings | 17 | – | 5 | – | 5 | – | 3 | – | |

| Parity before index | 0 | 545 | 41,3 | 311 | 38,5 | 199 | 38,6 | 109 | 37,3 |

| Pregnancy | 1 | 562 | 42,6 | 366 | 45,4 | 232 | 45,0 | 133 | 45,5 |

| ≥2 | 213 | 16,1 | 130 | 16,1 | 85 | 16,5 | 50 | 17,1 | |

| Missings | 17 | – | 5 | – | 5 | – | 3 | – | |

Groups agree with those defined in Figure 1: group 1 = children candidate for blood collection; group 2 = children with blood sampling successful; group 3 = children with total cholesterol analyzed and genotypes available; group 4 = children with total cholesterol and HDLc analyzed and genotypes available.

Results

Children’s mean age at blood collection was 25.3 months (range = 22.6–30.6) and did not differ between boys and girls. As shown in tables 3 and 4 , the group with both TC and HDLc analyzed (group 4) virtually did not differ from that with only TC (group 3) with regard to any of the variables relevant for this study. The same was true when comparing group 3 and 4 with group 1 (candidates for blood collection) and 2 (children with successful blood sampling). Plasma lipid levels were normally distributed. Mean values (±SD) for TC, HDLc, and nHDLc of children at 2 years were 3.80 (±0.62), 1.01 (±0.22), and 2.84 (±0.63) mmol/L, respectively.

Associations between SNPs and Plasma Lipid Levels

SNPs characteristics and genotype and minor allele frequencies are shown in table 5 . All SNPs were in Hardy Weinberg equilibrium. According to the regression coefficients obtained in model 1 ( table 6 ), heterozygous children (Mm) for the SNP rs174545 had about 0.15 mmol/L lower TC than children homozygous for the major allele (MM), and homozygous for the minor allele children (mm) had 0.30 mmol/L lower TC than MM children. These differences were significant even after correction for multiple testing. The results for the other SNPs were highly consistent with those for rs174545, both in terms of magnitude and direction of the association. HDLc was lower in mm than in MM children (with a difference of about 0.09 mmol/L that reached significance for the SNPs rs174546 and rs3834458). Instead, HDLc levels of Mm children did not differ much from those of MM children. The possibility that the association between FADS SNPs and HDLc levels was better explained by a recessive compared to an additive genetic model was tested and confirmed post-hoc by a partial F-test (at α level = 0.05). nHDLc levels were also lower in carriers of the minor allele compared to MM children, but the differences did not reach statistical significance.

Table 5. Genotype frequencies, minor allele frequencies (MAF), and location of the studied single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

| SNP (major/minor allele) | MM | Mm | mm | MAF (%) | Location |

| rs174545 (C/G) | 233 | 224 | 58 | 33 | 3′ UTR FADS1 |

| rs174546 (C/T) | 234 | 223 | 59 | 33 | 3′ UTR FADS1 |

| rs174556 (C/T) | 248 | 220 | 50 | 31 | Intron FADS1 |

| rs174561 (T/C) | 251 | 218 | 51 | 31 | Intron FADS1 |

| rs3834458 (T/del) | 233 | 227 | 59 | 33 | Intergenic region FADS1-FADS2 |

“MM”, “Mm”, and “mm” stand for homozygous for the major allele, heterozygous, and homozygous for the minor allele children, respectively.

Children with missing data on a specific genotype were excluded from the analyses involving such genotype.

Table 6. Associations between FADS gene variants and total cholesterol, HDLc, and nHDLc (model 1 according to Table 2).

| Total cholesterol | HDLc | nHDLc | ||||||||||||||||

| n | R2 (%) | β | 95% CI | p | n | R2 (%) | β | 95% CI | p | n | R2 (%) | β | 95% CI | p | ||||

| rs174545 | 515 | 2.9 | 291 | 1.9 | 291 | 1.8 | ||||||||||||

| Mm vs MM | –.154 | –.267 | –.041 | .008 | –.004 | –.057 | .050 | .893 | –.089 | –.241 | .062 | .247 | ||||||

| mm vs MM | –.303 | –.480 | –.126 | .001 | –.092 | –.180 | –.003 | .042 | –.198 | –.449 | .053 | .122 | ||||||

| rs174546 | 516 | 2.7 | 293 | 1.9 | 293 | 1.8 | ||||||||||||

| Mm vs MM | –.156 | –.269 | –.042 | .007 | –.008 | –.062 | .045 | .760 | –.099 | –.252 | .053 | .201 | ||||||

| mm vs MM | –.286 | –.463 | –.110 | .002 | –.095 | –.183 | –.006 | .037 | –.197 | –.450 | .056 | .127 | ||||||

| rs174556 | 518 | 2.5 | 294 | 1.1 | 294 | 1.6 | ||||||||||||

| Mm vs MM | –.142 | –.255 | –.029 | .014 | –.007 | –.061 | .047 | .804 | –.068 | –.220 | .084 | .379 | ||||||

| mm vs MM | –.297 | –.486 | –.109 | .002 | –.072 | –.167 | .023 | .136 | –.247 | –.514 | .021 | .070 | ||||||

| rs174561 | 520 | 2.4 | 295 | 1.1 | 295 | 2.0 | ||||||||||||

| Mm vs MM | –.147 | –.259 | –.034 | .011 | –.011 | –.065 | .042 | .681 | –.076 | –.228 | .076 | .326 | ||||||

| mm vs MM | –.279 | –.466 | –.093 | .003 | –.074 | –.168 | .020 | .124 | –.251 | –.518 | .015 | .065 | ||||||

| rs3834458 | 519 | 2.6 | 295 | 1.8 | 295 | 1.7 | ||||||||||||

| Mm vs MM | –.151 | –.264 | –.038 | .009 | –.006 | –.060 | .047 | .818 | –.093 | –.244 | .059 | .231 | ||||||

| mm vs MM | –.289 | –.466 | –.112 | .001 | –.094 | –.183 | .005 | .038 | –.195 | –.448 | .057 | .129 | ||||||

n: number of children included in the analysis; R2: percentage of variance explained (unadjusted R2); β: regression coefficient from linear regression analysis indicating the difference in mmol/L between Mm and mm compared to MM (reference category), where MM, Mm, and mm stand for homozygous for the major allele, heterozygous, and homozygous for the minor allele children, respectively; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; p: p-value. Values in bold are statistically significant after correction for multiple testing (p-value<0.040). Analyses were adjusted for recruitment group and age of children’s blood collection.

Contribution of Genetic and Non-genetic Determinants

FADS genotypes explained 2.4–2.9% of the variance in TC levels, 1.1–1.9% of the variance in HDLc levels, and 1.6–2.0% of the variance in nHDLc ( Table 6 , model 1). Non-genetic determinants explained 3.5, 4.1, and 10.4% of the variance in TC, HDLc, and nHDLc levels, respectively ( Table 7 , model 6). Compared with boys, girls had 0.17 and 0.20 mmol/L higher TC and nHDLc, respectively. Parity was negatively associated with nHDLc, so that children from women with 2 or more children before the index pregnancy had 0.26 mmol/L lower nHDLc than children from primipara women. This association was independent from maternal age. Children in the highest quintile of breastfeeding duration (breastfed for >11 months) had lower nHDLc than those in the lowest quintile (breastfed for ≤1 month). Lastly, birth weight showed a positive association with nHDLc levels. The other determinants tested were not significantly associated with blood lipid levels. The inclusion of BMI z-scores at 2 years instead of birth weight in model 6 resulted in a positive association between BMI z-score and nHDLc (β = 0.081, 95% CI = 0.003, 0.158), as occurred with birth weight, and in a negative association with HDLc (β = −0.029, 95% CI = −0.057, 0.000).

Table 7. Associations between non-genetic maternal and infant’s characteristics and breastfeeding with total cholesterol, HDLc, and nHDLc (model 6 according to Table 2).

| Total cholesterol (n = 521) | HDLc (n = 295) | nHDLc (n = 295) | |||||||||||||

| R2 (%) | β | 95% CI | p | R2 (%) | β | 95% CI | p | R2 (%) | β | 95% CI | p | ||||

| Gender (girl vs boy) | 3.5 | .166 | .055 | .278 | .003 | 4.1 | .008 | –.047 | .062 | .785 | 10.4 | .204 | .055 | .354 | .008 |

| Maternal smoking (Y vs N) | .171 | –.142 | .483 | .283 | .042 | –.105 | .189 | .576 | .244 | –.160 | .648 | .235 | |||

| Maternal alcohol intake (Y vs N) | –.122 | –.276 | .033 | .123 | –.007 | –.077 | .063 | .851 | –.002 | –.194 | .190 | .982 | |||

| Maternal age (years) | .006 | –.010 | .022 | .449 | .002 | –.005 | .010 | .537 | .021 | –.001 | .042 | .061 | |||

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | –.002 | –.018 | .014 | .791 | .001 | –.008 | .009 | .861 | –.004 | –.028 | .020 | .731 | |||

| Parity before index pregnancy (1 vs 0) | –.092 | –.221 | .037 | .160 | –.008 | –.069 | .053 | .798 | –.143 | –.311 | .025 | .095 | |||

| Parity before index pregnancy (≥2 vs 0) | –.060 | –.237 | .116 | .503 | –.018 | –.102 | .066 | .674 | –.256 | –.486 | –.026 | .029 | |||

| Pregnancy weight gain (kg) | .004 | –.009 | .016 | .541 | .002 | –.004 | .008 | .524 | –.006 | –.023 | .010 | .441 | |||

| Gestational age (weeks) | .018 | –.035 | .071 | .496 | –.007 | –.033 | .019 | .613 | .000 | –.071 | .071 | .999 | |||

| Breastfeeding duration* (quintile 2 vs1) | –.066 | –.244 | .112 | .467 | –.020 | –.105 | .065 | .645 | –.212 | –.445 | .020 | .074 | |||

| Breastfeeding duration (quintile 3 vs1) | –.022 | –.192 | .148 | .799 | –.010 | –.093 | .073 | .817 | –.202 | –.429 | .025 | .081 | |||

| Breastfeeding duration (quintile 4 vs1) | –.068 | –.248 | .113 | .463 | –.002 | –.091 | .086 | .956 | –.052 | –.294 | .190 | .675 | |||

| Breastfeeding duration (quintile 5 vs1) | –.127 | –.322 | .068 | .202 | .047 | –.047 | .141 | .331 | –.362 | –.619 | –.104 | .006 | |||

| Birth weight (kg) | .022 | –.114 | .159 | .749 | .016 | –.049 | .081 | .627 | .210 | .032 | .388 | .021 | |||

R2: percentage of variance explained (unadjusted R2); β: regression coefficient from linear regression analysis adjusting for recruitment group, age of children’s blood collection, and maternal education; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; p: p-value. Values in bold are statistically significant (p-value<0.05).

Breastfeeding duration was divided into quintiles to correct for its skewed distribution and investigate the presence of dose-effects.

Results from model 7 (not shown) demonstrated that the regression coefficients for the genetic and non-genetic determinants were virtually the same as when the genetic and non-genetic determinants were tested in two separate models (i.e. models 1 and 6, respectively), suggesting that each set of determinants were independent from each other (i.e. no confounding). Moreover, the percentages of variances explained by model 7 were close to the sum of variances explained by genetic and non-genetic determinants separately (Table S1). No significant interaction between genotypes and gender was found.

Discussion

In the study presented here we show that the associations between FADS SNPs genotypes and TC and HDLc levels are already present in 2-year-old preschool children. In addition, we report that FADS SNPs and non-genetic factors determine cholesterol levels independently from each other and explain a similar amount of variance in TC levels.

Plasma lipid levels were of the same order as seen in other studies in 2–3 year-old infants, when all expressed in mmol/L [2], [7], [11], [38]. mm children had lower TC levels than children homozygous for the major allele (MM) ( table 6 ). HDLc and nHDLc concentrations were also lower in minor allele carriers than in MM children, but statistical significance was not reached in all cases. The fact that the results for all SNPs were very consistent regarding the direction and strength of the associations was expected, based on the relatively high linkage disequilibrium (LD) between the studied SNPs (r2≥0.85, D′≥0.99) [19]. The lack of significance for nHDLc could be due to the smaller sample size compared to TC, smaller effect sizes, or higher measurement error (as nHDLc values derive from those of TC and HDLc). Alternatively, it could be that an association with nHDLc is found only when taking diet into account. In this line, Lu et al. and Dumont et al. found that the association between carrying one or two minor alleles of the FADS SNP rs174546 and having lower nHDLc levels became significant only in subjects with high intake of n-3 PUFAs or alpha-linolenic acid, respectively [25], [34]. Unfortunately, we lacked information on infant’s diet and hence could not investigate this possibility.

Expressing the absolute differences in cholesterol levels among genotypes as percentages, heterozygous children (Mm) had about 4, 0.5, and 2.5% lower TC, HDLc, and nHDLc levels, respectively, than MM children. Differences between mm and MM children were about 8, 7, and 7% for TC, HDLc, and nHDLc, respectively. This information reveals two interesting points. First, the relative differences between genotype groups seem to be larger in our population of preschool children than in adults or adolescents. Three previous studies presented their data in a way that allowed us to calculate the differences between genotypes as percentage [25], [29], [34]; from these studies, differences between MM and mm subjects appear to be lower than 4% for either TC, HDLc, and nHDLc. The second observation is that, while the association between FADS SNPs and TC seems to agree with an additive genetic model (so that each copy of the minor allele results in an additive decrease in TC, from 4% in Mm to 8% in mm), the association with HDLc agrees better with a recessive model. In this case, MM and Mm children have similar levels of HDLc, and levels are lower only in the mm group. The hypothesis that may follow this observation and that warrants further research is that, from the three genotype groups, Mm subjects may have the lowest TC/HDLc ratio and therefore potentially lower cardiovascular risk.

The biological mechanisms explaining the associations between FADS SNPs and cholesterol levels are unknown so far. They are most probably related to the differences in fatty acids proportions in blood and tissues among genotypes. It has been hypothesized that lower percentages of long-chain PUFAs in subjects with the mm genotype may explain the lower HDLc levels as a result of lower activation of the peroxisome proliferator activator receptor alpha (which regulates the expression of genes directly involved in HDL production). The lower LDLc observed in other studies, in turn, could be explained by the higher percentages of linoleic acid in mm subjects, which could increase membrane fluidity, enhance LDL-receptor recycling, and ultimately lower LDLc levels [29].

Among the non-genetic determinants studied, gender, parity, breastfeeding, and birth weight showed significant associations with plasma cholesterol levels ( table 7 ). Girls had higher TC and nHDLc than boys, and children with higher birth weight had higher nHDLc. These results are in line with those reported for preschool children from the ALSPAC Study [7], where girls had higher TC/HDLc ratio than boys, and boys with higher birth weight had higher TC/HDLc ratio at 43 months of age. Although TC/HDLc ratio and nHDLc levels cannot be directly compared, both measures partly reflect LDLc levels. Results on gender agree with studies in older children as well [8], [9]. Women with higher parity (2 or more children before the index pregnancy) had children with lower nHDLc. Rona et al. showed an inverse association between parity and TC in 9-year old children [9]. Regarding breastfeeding, we found that longer breastfeeding duration (>11 months) was associated with lower nHDLc levels when compared to shorter duration (≤1 month). A systematic review of observational studies concluded that breastfed infants have higher plasma TC and LDLc levels than their formula-fed counterparts during the first year of life [12]. This may be explained by differences in the composition of breast milk and infant formulas, the former having higher content of cholesterol and saturated fatty acids, but lower PUFAs [51]. However, results obtained in preschool children are mixed: three studies found no association [38], [52], [53] while two studies reported associations with TC levels in opposite directions [7], [11]. Although it is possible that the elevation of cholesterol levels associated with breastfeeding is transient and weakens or vanishes after weaning, more studies are needed to draw definitive conclusions. Lastly, it is worth noticing the positive association between maternal smoking and children’s TC and nHDLc, which is in line with Bekkers et al., who found that 8-year-old children whose mothers smoked during pregnancy had about 0.15 units higher TC/HDLc than children from mothers who did not [6]. The low number of women in our study who smoked during pregnancy (3%) may have limited the power to detect a significant association. Still, the consistency between our results and those by Bekkers et al. suggests a true effect of maternal smoking on children’s blood cholesterol levels which warrants confirmation.

A limitation of our study is the lack of infant’s dietary information. Hence, we could not check the contribution of diet to plasma cholesterol levels nor investigate the presence of gene-diet interactions. While interactions between FADS SNPs and diet were found in two studies in adults and adolescents [25], [34], no significant interaction was found in a study of 10-year-old children [35].

The studied SNPs explained only a low percentage of variance in plasma lipid level. This was not surprising, considering that several common gene variants discovered through GWAS can also explain, in aggregate, a relatively low percentage of the total variance (about 10%) [13]. Still, it is remarkable that in our study one SNP alone is able to explain as much variance in TC as the non-genetic determinants studied, and to be associated with an 8% difference between genotype groups.

In conclusion, in this study we have shown that FADS SNPs are associated with TC and HDLc levels already in infants of 2 years of age, and that the studied SNPs explain about the same amount of variance in TC levels as traditional non-genetic determinants. With this, we provide a new piece of evidence to explain how blood lipid levels may track from childhood to adulthood and to gain insight into the mechanisms that define plasma lipid levels in childhood. We believe that further knowledge on the genetic determinants of plasma lipids will come from the study of other common and rare genetic variants, gene-gene, and gene-environment interactions.

Supporting Information

Comparison of the percentages of explained variance of total cholesterol (TC), HDL cholesterol (HDLc), and non-HDL cholesterol (nHDLc) by genetic and non-genetic determinants.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank all the parents and children participating in the KOALA Birth Cohort Study.

Funding Statement

Carolina Moltó-Puigmartí was supported by a postdoctoral grant from “Fundación Alfonso Martín Escudero” (Spain) http://www.fundame.org/. DNA collection was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO Spinoza award of Prof. D.S. Postma) http://www.nwo.nl/. Genotyping was supported partly by the Munich Center of Health Sciences (MCHEALTH) http://www.en.mc-health.uni-muenchen.de/index.html. Blood lipids determinations were funded by the Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sport, the Netherlands http://www.government.nl/ministries/vws (Kennisvraag 5.4.1a, 2006). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. NCEP Expert Panel on Blood Cholesterol Levels in Children (1992) Adolescents (1992) National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP): highlights of the report of the Expert Panel on Blood Cholesterol Levels in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 89: 495–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Freedman DS, Byers T, Sell K, Kuester S, Newell E, et al. (1992) Tracking of serum cholesterol levels in a multiracial sample of preschool children. Pediatrics 90: 80–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Srinivasan SR, Frontini MG, Xu J, Berenson GS (2006) Utility of childhood non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in predicting adult dyslipidemia and other cardiovascular risks: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics 118: 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Katzmarzyk PT, Perusse L, Malina RM, Bergeron J, Despres JP, et al. (2001) Stability of indicators of the metabolic syndrome from childhood and adolescence to young adulthood: the Quebec Family Study. J Clin Epidemiol 54: 190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McGill HC Jr, McMahan CA, Herderick EE, Malcom GT, Tracy RE, et al. (2000) Origin of atherosclerosis in childhood and adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr 72: 1307s–1315s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bekkers MB, Brunekreef B, Smit HA, Kerkhof M, Koppelman GH, et al. (2011) Early-life determinants of total and HDL cholesterol concentrations in 8-year-old children; the PIAMA birth cohort study. PLoS ONE 6: e25533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cowin I, Emmett P (2000) Cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations, birthweight and central obesity in pre-school children. ALSPAC Study Team. Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 24: 330–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. DeStefano F, Berg RL, Griese GG Jr (1995) Determinants of serum lipid and lipoprotein concentrations in children. Epidemiology 6: 446–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rona RJ, Qureshi S, Chinn S (1996) Factors related to total cholesterol and blood pressure in British 9 year olds. J Epidemiol Community Health 50: 512–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cowin IS, Emmett PM (2001) Associations between dietary intakes and blood cholesterol concentrations at 31 months. Eur J Clin Nutr 55: 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ward SD, Melin JR, Lloyd FP, Norton JA Jr, Christian JC (1980) Determinants of plasma cholesterol in children–a family study. Am J Clin Nutr 33: 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Owen CG, Whincup PH, Odoki K, Gilg JA, Cook DG (2002) Infant feeding and blood cholesterol: a study in adolescents and a systematic review. Pediatrics 110: 597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, et al. (2010) Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature 466: 707–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kathiresan S, Willer CJ, Peloso GM, Demissie S, Musunuru K, et al. (2009) Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nat Genet 41: 56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aulchenko YS, Ripatti S, Lindqvist I, Boomsma D, Heid IM, et al. (2009) Loci influencing lipid levels and coronary heart disease risk in 16 European population cohorts. Nat Genet 41: 47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sabatti C (2009) Service SK, Hartikainen AL, Pouta A, Ripatti S, et al (2009) Genome-wide association analysis of metabolic traits in a birth cohort from a founder population. Nat Genet 41: 35–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lattka E, Illig T, Koletzko B, Heinrich J (2010) Genetic variants of the FADS1 FADS2 gene cluster as related to essential fatty acid metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol 21: 64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moltó-Puigmartí C, Plat J, Mensink RP, Muller A, Jansen E, et al. (2010) FADS1 FADS2 gene variants modify the association between fish intake and the docosahexaenoic acid proportions in human milk. Am J Clin Nutr 91: 1368–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rzehak P, Thijs C, Standl M, Mommers M, Glaser C, et al. (2010) Variants of the FADS1 FADS2 gene cluster, blood levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids and eczema in children within the first 2 years of life. PLoS ONE 5: e13261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dupuis J, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I, Saxena R, Soranzo N, et al. (2010) New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet 42: 105–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kroger J, Zietemann V, Enzenbach C, Weikert C, Jansen EH, et al. (2011) Erythrocyte membrane phospholipid fatty acids, desaturase activity, and dietary fatty acids in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. Am J Clin Nutr 93: 127–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kwak JH, Paik JK, Kim OY, Jang Y, Lee S-H, et al. (2011) FADS gene polymorphisms in Koreans: Association with n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in serum phospholipids, lipid peroxides, and coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 214: 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hicks AA, Pramstaller PP, Johansson Ãs, Vitart V, Rudan I, et al. (2009) Genetic Determinants of Circulating Sphingolipid Concentrations in European Populations. PLoS Genet 5: e1000672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Truong H, DiBello JR, Ruiz-Narvaez E, Kraft P, Campos H, et al. (2009) Does genetic variation in the d6-desaturase promoter modify the association between alpha-linolenic acid and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome? Am J Clin Nutr 89: 920–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lu Y, Feskens EJ, Dolle ME, Imholz S, Verschuren WM, et al. (2010) Dietary n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake interacts with FADS1 genetic variation to affect total and HDL-cholesterol concentrations in the Doetinchem Cohort Study. Am J Clin Nutr 92: 258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stancakova A, Paananen J, Soininen P, Kangas AJ, Bonnycastle LL, et al. (2011) Effects of 34 risk loci for type 2 diabetes or hyperglycemia on lipoprotein subclasses and their composition in 6,580 nondiabetic Finnish men. Diabetes 60: 1608–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nakayama K, Bayasgalan T, Tazoe F, Yanagisawa Y, Gotoh T, et al. (2010) A single nucleotide polymorphism in the FADS1/FADS2 gene is associated with plasma lipid profiles in two genetically similar Asian ethnic groups with distinctive differences in lifestyle. Hum Genet 127: 685–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Waterworth DM, Ricketts SL, Song K, Chen L, Zhao JH, et al. (2010) Genetic Variants Influencing Circulating Lipid Levels and Risk of Coronary Artery Disease. Arterioscl Throm Vas 30: 2264–2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tanaka T, Shen J, Abecasis GR, Kisialiou A, Ordovas JM, et al. (2009) Genome-wide association study of plasma polyunsaturated fatty acids in the InCHIANTI Study. PLoS Genet 5: e1000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hellstrand S, Sonestedt E, Ericson U, Gullberg B, Wirfalt E, et al. (2012) Intake levels of dietary long-chain PUFAs modify the association between genetic variation in FADS and LDL-C. J Lipid Res 53: 1183–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gieger C, Geistlinger L, Altmaier E, Hrabe de Angelis M, Kronenberg F, et al. (2008) Genetics meets metabolomics: a genome-wide association study of metabolite profiles in human serum. PLoS Genet 4: e1000282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dumitrescu L, Carty CL, Taylor K, Schumacher FR, Hindorff LA, et al. (2011) Genetic determinants of lipid traits in diverse populations from the population architecture using genomics and epidemiology (PAGE) study. PLoS Genet 7: e1002138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chasman DI, Pare G, Mora S, Hopewell JC, Peloso G, et al. (2009) Forty-three loci associated with plasma lipoprotein size, concentration, and cholesterol content in genome-wide analysis. PLoS Genet 5: e1000730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dumont J, Huybrechts I, Spinneker A, Gottrand F, Grammatikaki E, et al. (2011) FADS1 genetic variability interacts with dietary alpha-linolenic acid intake to affect serum non-HDL-cholesterol concentrations in European adolescents. J Nutr 141: 1247–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Standl M, Lattka E, Stach B, Koletzko S, Bauer CP, et al. (2012) FADS1 FADS2 Gene Cluster, PUFA Intake and Blood Lipids in Children: Results from the GINIplus and LISAplus Studies. PLoS ONE 7: e37780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kummeling I, Thijs C, Penders J, Snijders BEP, Stelma F, et al. (2005) Etiology of atopy in infancy: The KOALA Birth Cohort Study. Pediat Allerg Imm-UK 16: 679–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bastiaanssen JM, de Bie RA, Bastiaenen CH, Heuts A, Kroese ME, et al. (2005) Etiology and prognosis of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain; design of a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 5: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Freedman DS, Lee SL, Byers T, Kuester S, Sell KI (1992) Serum cholesterol levels in a multiracial sample of 7,439 preschool children from Arizona. Prev Med 21: 162–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (dbSNP) website. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. (dbSNP Build ID: 136). Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/. Accessed 2012 March 5.

- 40.Sambrook J RD (2007) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Preparation of plasmid DNA by lysis with SDS.

- 41. Bottema RW, Reijmerink NE, Kerkhof M, Koppelman GH, Stelma FF, et al. (2008) Interleukin 13, CD14, pet and tobacco smoke influence atopy in three Dutch cohorts: the allergenic study. Eur Respir J 32: 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rzehak P, Heinrich J, Klopp N, Schaeffer L, Hoff S, et al. (2009) Evidence for an association between genetic variants of the fatty acid desaturase 1 fatty acid desaturase 2 (FADS1 FADS2) gene cluster and the fatty acid composition of erythrocyte membranes. Br J Nutr 101: 20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schaeffer L, Gohlke H, Muller M, Heid IM, Palmer LJ, et al. (2006) Common genetic variants of the FADS1 FADS2 gene cluster and their reconstructed haplotypes are associated with the fatty acid composition in phospholipids. Hum Mol Genet 15: 1745–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Malerba G, Schaeffer L, Xumerle L, Klopp N, Trabetti E, et al. (2008) SNPs of the FADS gene cluster are associated with polyunsaturated fatty acids in a cohort of patients with cardiovascular disease. Lipids 43: 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. de Bakker PI, Yelensky R, Pe’er I, Gabriel SB, Daly MJ, et al. (2005) Efficiency and power in genetic association studies. Nat Genet 37: 1217–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fredriks AM, van Buuren S, Wit JM, Verloove Vanhorick SP (2000) Body index measurements in 1996–7 compared with 1980. Arch Dis Child 82: 107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nyholt DR (2004) A simple correction for multiple testing for single-nucleotide polymorphisms in linkage disequilibrium with each other. Am J Hum Genet 74: 765–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW (2009) Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology 20: 488–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dedoussis GV, Theodoraki EV, Manios Y, Yiannakouris N, Panagiotakos D, et al. (2007) The Pro12Ala polymorphism in PPARgamma2 gene affects lipid parameters in Greek primary school children: A case of gene-to-gender interaction. Am J Med Sci 333: 10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Little RJA (1988) A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc 83: 1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kallio MJ, Salmenpera L, Siimes MA, Perheentupa J, Miettinen TA (1992) Exclusive breast-feeding and weaning: effect on serum cholesterol and lipoprotein concentrations in infants during the first year of life. Pediatrics 89: 663–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Friedman G, Goldberg SJ (1975) Concurrent and subsequent serum cholesterol of breast- and formula-fed infants. Am J Clin Nutr 28: 42–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mize CE, Uauy R (1991) Effect of early infancy dietary lipid composition on plasma lipoprotein cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein receptor activity. Ann N Y Acad Sci 623: 455–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Comparison of the percentages of explained variance of total cholesterol (TC), HDL cholesterol (HDLc), and non-HDL cholesterol (nHDLc) by genetic and non-genetic determinants.

(DOC)