Abstract

The epithelium of multicellular organisms possesses a well-defined architecture, referred to as polarity that coordinates the regulation of essential cell features. Polarity proteins are intimately linked to the protein complexes that make the tight, adherens and gap junctions; they contribute to the proper localization and assembly of these cell-cell junctions within cells and consequently to functional tissue organization. The establishment of cell-cell junctions and polarity are both implicated in the regulation of epithelial modifications in normal and cancer situations. Uncovering the mechanisms through which cell-cell junctions and epithelial polarization are established and how their interaction with the microenvironment direct cell and tissue organization has opened new venues for the development of cancer therapies. In this review, we focus on the breast epithelium to highlight how polarity and cell-cell junction proteins interact together in normal and cancerous contexts to regulate major cellular mechanisms such as migration. The impact of these proteins on epigenetic mechanisms responsible for resetting cells towards oncogenesis is discussed in light of increasing evidence that tissue polarity modulates chromatin function. Finally, we give an overview of recent breast cancer therapies that target proteins involved in cell-cell junctions.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Cell junction, Differentiation, Epigenetics, Mammary epithelial Cell, Polarity

1. Introduction

The epithelia constitute the majority of mammalian tissues, and are at the origin of 90% of human cancers. Epithelial differentiation and function depend on three major aspects: establishment of intercellular junctions and adhesion, basoapical polarity and proper mitotic spindle orientation (Dickinson et al., 2011). Cellular differentiation is characterized by a cell acquiring a defined structure that enables it to interact with other cells and with its microenvironment, including the stroma, hormones, growth factors and the extracellular matrix, to perform specific functions, as opposed to a stem cell that has no defined "identity" and can give rise to various cell types. To attain a wide range of functions such as protection, secretion and absorption, epithelial cells form highly organized tissues characterized by the tight regulation of polarity and cell-cell junction complexes. Epithelial cell polarity is defined as the asymmetrical distribution of cell junction and polarity proteins. It contributes to the polarization of the epithelial tissue, which is characterized by the coordination of cell behavior in a two-dimensional sheet and the establishment of asymmetry within thousands of epithelial cells. Importantly, the formation of junction complexes at cell-cell contacts, better known as cell junctions, determines the architecture of the epithelium by mediating adhesion of cells to one another in an orderly manner, with tight junctions at the apex of cells (i.e., at the opposite cellular pole compared to the cellular pole in contact with the extracellular matrix) determining the limit between apical polarity and basolateral polarity. Cell junctions also mediate communication by allowing the passage of signals and metabolites between neighboring cells. Polarity and cell junction proteins act in concert whereby the same proteins that control polarity dictate the allocation of cell junction proteins. In addition, both types of proteins are classified as signaling hubs that regulate signal transduction pathways involved in normal and cancer cell functions as we will discuss in the context of this review. On the other hand, tissue architecture, which depends on proper cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions involving a reciprocal exchange of mechanical and biochemical stimuli (Hansen and Bissell, 2000), is altered in the early stages of cancer. Therefore, research efforts to decipher the mechanisms through which cell junctions and polarity proteins contribute to the acquisition and maintenance of normal tissue architecture are paramount.

A- Breast Development and Cancer

Being one of very few organs that continue to develop and differentiate late during the lifespan of an individual, the mammary gland is a good model to study how changes in the interaction between cells and their environment, as well as modulations in tissue architecture, might lead to tumor development. The mouse has long emerged as a primary animal model for the human breast development because both species have a number of similarities at the level of the structure and function of their mammary glands. The mouse mammary gland is a specialized organ that begins developing at day 10 of gestation with the formation of the mammary line (Watson and Khaled, 2008). At embryonic day 16, ductal branching morphogenesis begins once the mammary sprout reaches the fat pad, hence giving rise to the rudimentary ductal tree present at birth (Hens and Wysolmerski, 2005). During puberty, a second round of rapid expansion of the ductal epithelial cells takes place concurrent with ductal lumen formation (Foley et al., 2001). The full differentiation of the mammary gland occurs upon pregnancy, during which extensive proliferation and sprouting of the mature milk-producing alveoli occurs (Hens and Wysolmerski, 2005). These morphogenetic events are accompanied by cellular differentiation processes that result in specialized types of cells such as epithelial cells that form the ductal network, with adipocytes that constitute the fat pad in which the ductal network is embedded, vascular endothelial cells that make up the blood vessels, stromal cells that include fibroblasts and a variety of immune cells. There are two main types of epithelia in the mammary gland: the luminal epithelium that forms ducts and the secretory alveoli, and the basal epithelium that consists essentially of myoepithelial cells. Both luminal and myoepithelial cells harbor mammary stem cells that endow extensive renewing capacities to the mammary gland during remodeling. Indeed, these stem cells have great implications for the understanding of the mammary gland physiology, and most importantly, provide a new insight to recognize a potential origin of breast cancer (Visvader and Lindeman, 2011). The differentiation of the mammary epithelium encompasses the attachment of epithelial cells to the basement membrane (a specialized form of extracellular matrix), thus creating the basal pole and the formation of the lumen apically by sealing cell-cell contacts with tight junctions, which overall defines the basoapical polarity axis. Perturbations in mammary epithelial cell adhesion, communication and polarity could bring about one of the most common types of cancers in women worldwide. Breast cancer has become the most frequent carcinoma and the second most common cause of cancer-related mortality in women. Since 1999, incidence rates of in situ breast cancers have continued to increase in women below 50 years of age and have become stable in women aged 50 and older (Breen et al., 2011). Given such rates of incidence and mortality, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms that ensure normal differentiation of the mammary gland is vital to unravel how breast cancer is initiated so that improved anticancer strategies can be devised. Normal differentiation at the tissue level requires establishment of a specific architecture, which is partly accomplished through cell junctions and polarity.

B- Cell Junctions and Polarity

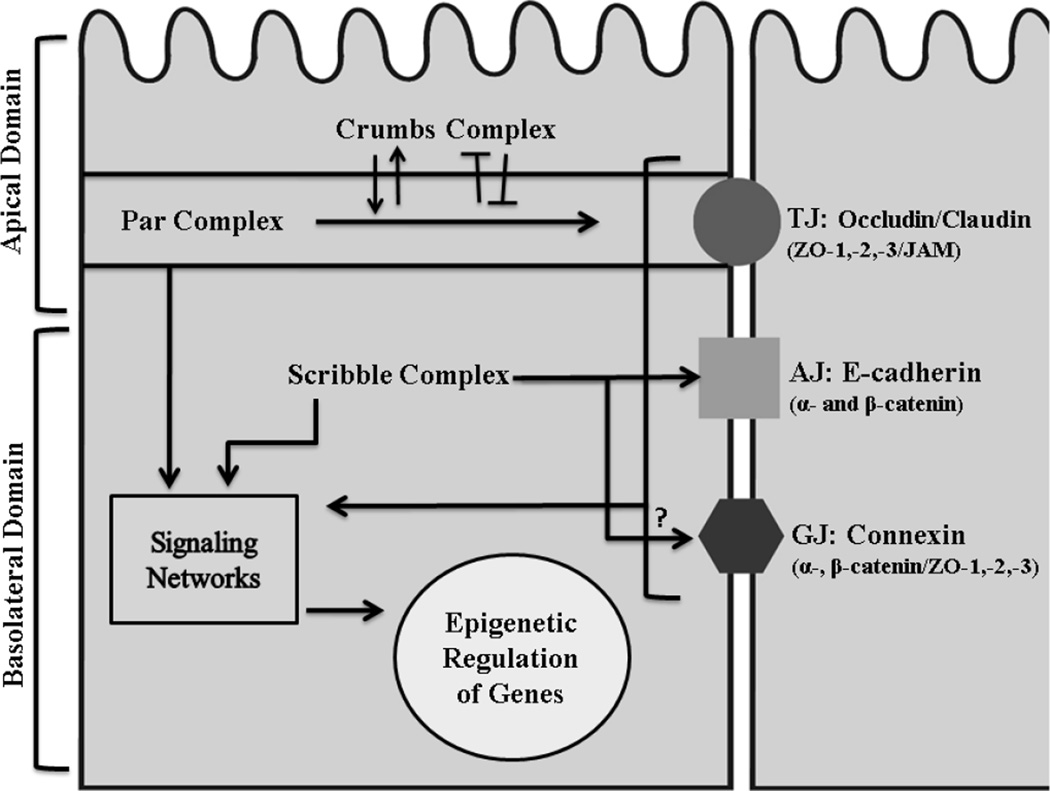

Cell junctions are classified into tight junctions (TJ), adherens junctions (AJ), and gap junctions (GJ) (Fig. 1). These junctions consist of transmembrane proteins with intracellular domains that interact with partner signaling molecules, and extracellular domains that mediate the communication between neighboring cells. Cell junction complexes are asymmetrically localized as a result of the formation of the basoapical axis, characteristic of the polarized epithelium (Nelson, 2003). Formation of a basoapical polarity axis not only regulates the localization of cell junctions, but also modifies gene expression patterns via the interaction of junction and polarity proteins with genome remodeling factors.

Figure 1. Epithelial cell junctions and polarity.

There is an asymmetric subcellular localization of polarity protein complexes (Crumbs, Par and Scribble) and of cell junctions (TJs, AJs and GJs) along the basoapical axis of normally polarized mammary epithelial cells. While the apical domain is specified by the Crumbs and the Par complexes, the basolateral domain is defined by Scribble proteins. Polarity proteins regulate the proper establishment of cell junction complexes that are made by transmembrane proteins (Occludin, Claudin and JAMs for TJ; Cadherins for AJ; Connexins for GJ) associated with various cytoplasmic partners (ZO proteins, catenins and other (Dbouk et al. 20090)). For example, proteins of the Par complex ensure the localization and maintenance of TJs at the apical side of the membrane. The Crumbs proteins regulate TJ formation through their reciprocal interaction with Par proteins; they can positively (arrow head) or negatively (blunt-end head) affect one another to guarantee the establishment of the apical domain of the cell. The basoapical domain is characterized by both AJs and GJs. Scribble proteins interact with AJs to allow their proper segregation away from the TJ; however, it is not yet clear how Scribble proteins regulate GJs. Both cell junctions and polarity proteins constitute new class of tumor suppressors that play integral roles in modulating signaling networks involved in cell differentiation that, in turn, will relay the epigenetic regulatory role of these proteins (Lelièvre, 2010).

Much of what is known about the mechanisms of basoapical polarity comes from studies in Drosophila melanogaster (Wodarz, 2005); these are being extended to mammals to define the pathways through which signals integrate and establish polarity during tissue morphogenesis (Macara, 2004). The investigation of polarity in drosophila has characterized a highly conserved set of proteins referred to as polarity proteins and classified them into three functional groups: Crumbs, Par and Scribble that will be highlighted in the context of this review (Fig. 1).

Interestingly, cell adhesion, cell communication and polarity have long been correlated with a normal phenotype of epithelial cells; however, an emerging body of evidence has revealed that tumor cells also tend to adhere and communicate among each other and with other cell types. It is now established that coordinated communication via cell-cell contacts as well as cell polarization characterize invasive tumors since both of these features are essential for the migration and metastasis of cancer cells (Bravo-Cordero et al., 2012). This information implies that multicellular organization associated with cell junction formation and polarity should not only be gained from the context of normal differentiation but also in oncogenesis (Scheel and Weinberg, 2012). Paradoxically, loss of tissue polarity is a precondition to tumorigenesis (Shin et al., 2006; Chandramouly et al., 2007). Therefore, the regulation of polarity is critical not only to normal differentiation but also to cancer initiation and progression. Further understanding of the biology of cell junction and polarity proteins and their associated pathways are essential for identifying potential biomarkers to improve detection and therapies of carcinomas.

Cell junctions have transcended their ascribed roles as structural cellular components

Although cell junction molecules serve to provide a structural continuum between cells, they are now perceived as signaling hubs integrating signals from the cell’s surrounding to modulate cell function and often gene expression (Giepmans and van Ijzendoorn, 2009; Dbouk et al., 2009). Cell junctions independently contribute to the maintenance of tissue morphology and homeostasis; nevertheless, they display overlapping localization and multiple interactions amongst each other.

We will present the cell junction complexes from the apical cellular pole to the basal cellular pole in the normal epithelium (Fig. 1). TJs are belt-like structures that control the diffusion of molecules into the intercellular space by forming selectively permeable barriers at the apical region of cells. As mentioned earlier, they are also major contributors to tissue polarity as they mark the boundaries between apical and basolateral membranes, hence preventing the movement of proteins and other macromolecules from one domain of the plasma membrane to another. TJs are composed of transmembrane components and cytoskeletal connectors. The membrane spanning proteins, i.e., occludins, claudins and junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs), interact through their cytoplasmic domains with zonula occludens (ZO) family of proteins (Chiba et al., 2008). The extracellular domains of occludin determine their localization to tight junctions and regulate the paracellular permeability barrier between cells. Claudins directly regulate the gate function by determining ion charge selectivity, permeability dependence on ion concentration and competition for movement of molecules (Wu et al., 1998). They are also known to recruit occludins to tight junctions (Martin and Jiang, 2009). These proteins interact with one another to form functional TJs where the extracellular domain of occludin interacts with both claudin and JAM, and disruption of such interactions inhibits reformation of TJs after calcium repletion (Nusrat et al., 2005). In addition, ZO-1 has been proposed to be a scaffolding protein between transmembrane and cytoplasmic proteins, and is a potential link between TJs and AJs (Utepbergenov et al., 2006). TJ proteins are not mere structural proteins; they also have the ability to modulate signaling pathways related to tissue homeostasis. Occludins interact with key proteins in signaling pathways involved in normal development and differentiation, which makes their expression and localization essential for normal epithelial differentiation. For example, occludins, through regulating TGF-β type I receptor localization, enable the TGF-β dependent TJ disassembly during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a phenomenon during which cells acquire mesenchymal features that enable them to leave the epithelium for the purpose of normal tissue development or cancer metastasis (Barrios-Rodiles et al., 2005). JAM proteins, on the other hand, regulate epithelial cell morphology and enhance β1-integrin expression through the control of Rap1 GTPase activity (Mandell et al., 2005), which contributes to the maintenance of cell attachment to the basement membrane, a contact often disrupted in cancer.

Located underneath TJs are junctions characterized by transmembrane cadherins that mediate calcium-dependent intercellular adhesion, and regulate cell signaling, transcription and organization of the actin cytoskeleton. Cadherins can be grouped into two main families: classical cadherins that form AJs and encompass epithelial, neuronal and placental cadherins (referred to as E-cadherin, N-cadherin and P-cadherin, respectively), and nonclassical desmosomal cadherins that form desmosomes, which mediate firm cellular adhesion and anchorage of intermediate filament cytoskeleton to the membrane. AJs, which are basolateral, are the first cell junctions that form between two contacting cells during cell junction biogenesis. AJ formation has been suggested to be a prerequisite for the initiation and stabilization of other intercellular junctions, including TJs, desmosomal junctions and GJs (Capaldo and Macara, 2007). The core of AJs is the interaction between cadherins, namely E-cadherin, and the catenins family (α-catenin, β-catenin and p120 catenin). When intercellular contacts form, cadherins aggregate and spread laterally to enhance the contact (Ehrlich et al., 2002). E-cadherin is involved in the regulation of epithelial cell growth and differentiation by activating MAPK pathway, as shown with a nontumorigenic keratinocyte cell line, HaCat (Pece and Gutkind, 2000). It also acts as a negative regulator of Wnt signaling pathways that are highly implicated in cell proliferation, differentiation, gene transcription and cell adhesion. Indeed, by binding to β-catenin at the cell surface, E-cadherin sequesters this protein from the nucleus, thus preventing its pro-proliferative potential (Wijnhoven et al., 2000).

Also located at epithelial cell-cell contacts and often found to be spread underneath the TJs along the remainder of the lateral cell membranes are GJs (Guttman and Finlay, 2009). They form clusters of intercellular channels with numerous functions including rapid transmission of action potentials, and diffusion of metabolites, nutrients, second messengers such as calcium ions, 1,4,5-inositol-trisphosphate (IP3) and cyclic nucleotides, that ultimately affects gene transcription, proliferation and apoptosis. GJ channels are formed upon the pairing of two apposing connexons, which are composed of six transmembrane proteins called connexins (Cxs). Functional GJs were reported in the murine mammary gland (Talhouk et al., 2005, 2008) and in human non-neoplastic mammary luminal epithelial cells (Lelièvre, unpublished data). The spatial and temporal expression of connexins and their role in murine mammary gland development has been extensively studied (reviewed by El-Sabban et al., 2003; McLachlan et al., 2007). In addition to Cx26 and Cx43 normally observed in the human mammary gland, Cx32 and the recently identified Cx30 were also expressed in the murine mammary gland (Talhouk et al., 2005). The intracellular C-terminal domain of Cxs interacts with proteins from other junction complexes namely occludins, claudins, ZO-1, ZO-2, cadherins and catenins, affecting their metabolism and function. These findings highlight a GJ-independent role of Cxs that is mediated through their C-termini (Herveet al., 2004; Dbouk et al., 2009). For example, C-termini of both Cx43 and Cx26 were reported to form a complex with ZO-1 and β-catenin at the membrane of mammary epithelial murine cells, hence contributing to the differentiated state of these cells as shown by the production of β-casein, a milk precursor (Talhouk et al., 2008).

The integrity of the basoapical polarity axis relies on both polarity protein complexes and cell junctions components

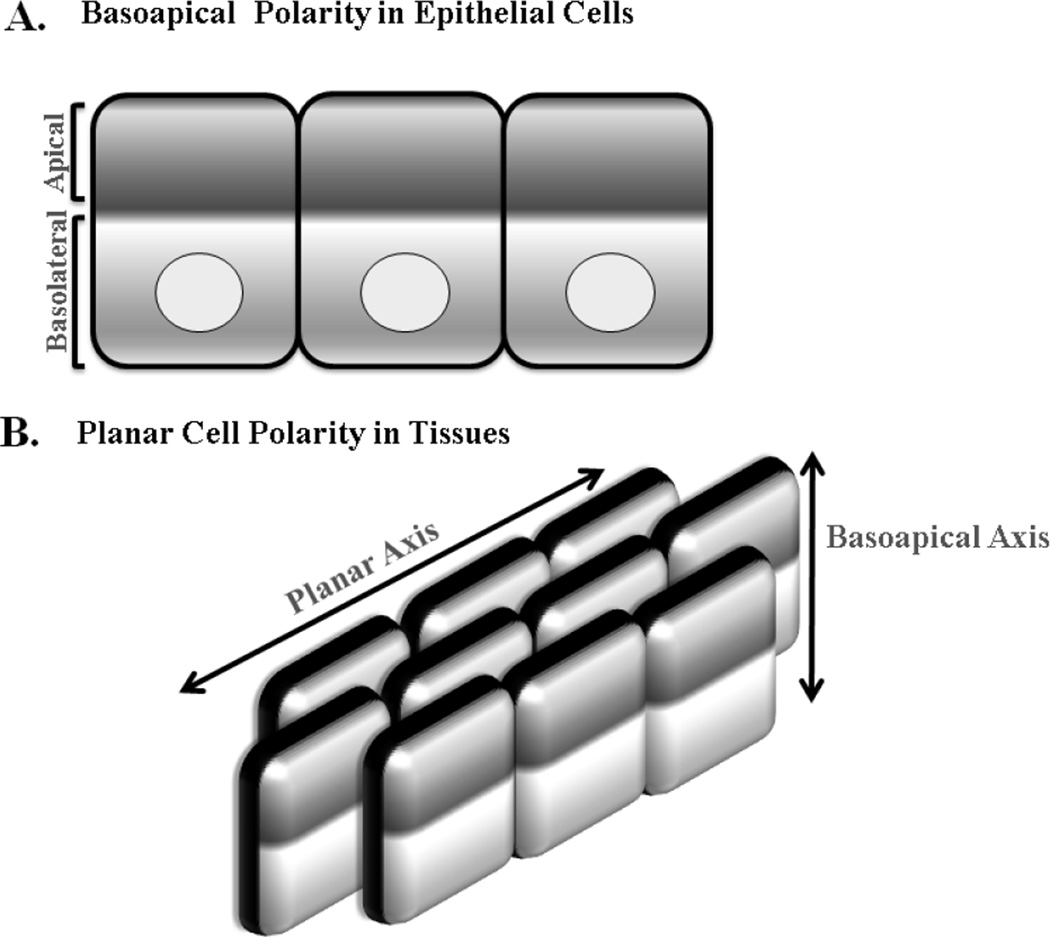

As described above, polarity in the normal epithelium is referred to as basoapical polarity for which cell junctions and polarity proteins are asymmetrically localized between the apex and the base (against the basement membrane) of the cell (Fig. 2A). This is very different from: 1- planar cell polarity in tissues which requires the establishment of asymmetry within cells even if they are very far apart (Fig. 2B) and 2- front-back polarity for which cytoskeletal and membranous proteins redistribute for the purpose of cellular migration and division. Functional analyses have revealed a highly conserved set of proteins (the polarity proteins) for basoapical tissue polarity that are classified into three groups: Crumbs (Crumbs/PALS/PATJ) and Par (Par3/Par6/aPKC/Cdc42) which are apical, and Scribble (Scrib/Dlg/Lgl) which is basolateral (Dow et al., 2007). These proteins interact and affect each other's localization. Upon initiation of basoapical polarity, Par3 is transported to the apical side of the cell marking the first event before the formation of cell junctions. Following apical localization of Par3, de novo cell-cell contacts are generated through the enrichment of E-cadherin, JAM-A, ZO-1 and nectin, a cellular adhesion molecule, at the membrane (Ebnet, 2008). These contacts activate Rac1 which, in turn, inhibits RhoA to allow the formation and expansion of the cell junction complex (Nakagawa et al., 2001).

Figure 2. Cell versus Tissue Polarity.

Epithelia display two types of polarity. A. Basoapical polarity which is defined by the asymmetrical compartmentalization of epithelial cells into apical and basal domains along their cross-sectional axis where the apical surface faces the lumen of a tissue and the basal surface is at cell-cell contacts. The color gradient indicates the asymmetric localization of cellular proteins required for the segregation of the apical and basolateral domains (basoapical axis) of the epithelial cell. B. In addition to the polarity of individual cells, planar polarity is determined by a set of proteins that regulate the orientation of groups of cells within a tissue. Epithelial cells within the tissue coordinate across a two-dimensional sheet that is perpendicular to the basoapical axis. This property of tissue structure is attained by the asymmetry within epithelial cells located hundreds of cells apart.

In light of the literature on Drosophila that brought the first evidence of apical polarity proteins acting as tumor suppressors and the role of cell junctions in the control of epithelial homeostasis, it is essential to envision how the relationship between cell junction and polarity proteins might be implicated in oncogenesis. As discussed below, these two families of proteins influence steps that are essential in both the normal and cancerous development of the breast epithelium by acting as signaling regulators and possibly, by modifying the epigenetic control of genes implicated in tumor initiation.

2. Crosstalk between Cell Junctions and Polarity Proteins

Given that both cell contacts and polarity should be secured for normal differentiation, understanding how they affect each other is essential. Much of our knowledge of how both, cell junction and polarity proteins, affect each other originate from studies in cancer models, rather than in the normal context, where the in vitro manipulations that might restore their localization and/or expression enable us to understand their biology in the normal context. The most studied junctions in relation to polarity proteins have been the TJs; however, evidence is accumulating in support of a regulatory role of polarity proteins in the establishment of AJs and GJs as well.

A- Tight Junctions and Polarity

The role of TJs in regulating signal transduction pathways involved in tissue homeostasis suggests that the disorganization of these junctions could facilitate cancer initiation. TJs maintenance is intimately correlated with one of the early polarity pathways activated during differentiation, known as the Par3/Par6/aPKC complex. This complex localizes to TJs at the membrane through Par3. The interaction of Par3 with the TJ is accomplished through the direct association with JAM, eventually leading to the recruitment of the Par3/Par6/aPKC complex (Bradfield et al., 2007; Ebnet et al., 2004; Weber et al., 2007). The complex then activates Cdc42, a Rho family GTPase, which subsequently activates aPKC leading to the maturation of TJs. When over-expressed, Par6 was found to disrupt the localization of Par3 at cell-cell adhesion resulting in the mislocalization of ZO-1, a tight junction core protein (Ebnet et al., 2004; Shin et al., 2006). Furthermore, Par3 over-expression led to enhanced TJ function as assessed by the development of transepithelial electrical resistance and the TJ-localization of ZO-1 in Madin-Darby Canine Kidney Epithelial Cells (MDCK) (Yamanaka et al., 2003). A member of the Par complex, aPKC inactivates Lgl which induces the disassembly of the Par3/Par6/aPKC complex, hence controlling the dynamics and maturation of TJs during epithelial tissue remodeling (Betschinger et al., 2003). Furthermore, the Par6/TGFβ polarity pathway is essential for the cytoskeletal reorganization that contributes to TJ formation and remodeling. Indeed, inhibition of Par6 induced the reversion of the EMT phenotype in breast cancer cells in which ZO-1 apical localization had been restored (Viloria-Petit et al., 2009). The Crumbs complex of proteins also has an impact on TJs. It was shown that induced expression of Crb3 polarity protein in a nonneoplastic human mammary epithelial cell line, MCF-10A, that had lost the ability to form TJs, induced these cells to form TJs (Fogg et al., 2005). These data shed light on a fundamental role played by polarity proteins in cancer as being critical regulators of TJ formation and maintenance.

B- Adherens Junctions and Polarity

AJs are the most studied junctions in the context of breast cancer. Recent data have provided some insights on the role of polarity proteins in the modulation of AJs mainly through the regulation of E-cadherin. Specifically, Scrib stabilizes the coupling between E-cadherin and catenins and its depletion disrupts E-cadherin mediated cell-cell adhesion (Qin et al., 2005). In addition, Dlg has been observed to colocalize with E-cadherin and its knock-down in Caco2 human epithelial colorectal adenocarcinoma cells prevented E-cadherin from properly localizing to cell junctions (Laprise et al., 2004). The localization of E-cadherin is also regulated by members of other polarity groups, like PALS1, since the loss of PALS1 in MDCK cells disrupted the formation of AJs (Wang et al., 2007). Interestingly, there is a reciprocal effect of E-cadherin on polarity proteins. In particular, Scrib was shown to be recruited at cell–cell junctions in an E-cadherin-dependent manner in MDCK cells; moreover, when E-cadherin expression was lost in Caco-2 cells, Scrib was mislocalizaed (Navarro et al., 2005). Given the apparent interaction between E-cadherin and polarity proteins; deciphering the mechanisms governing this interaction could provide a better understanding of AJs formation and maintenance.

C- Gap Junctions and Polarity

Connexins contribute to the communication of small molecules between cells during embryogenesis, tissue development and cancer. There are few studies that shed light on the interaction between GJs and polarity. The association of Cxs with TJ core protein ZO-1 seems to contribute to the organization of GJs, either directly or indirectly, through the recruitment of partner proteins involved in various downstream signaling pathways. ZO-1 has been reported to associate with Cx36, 45, 35, 31.9, 46, 47 and 50 (Li et al., 2004, Nielsen et al., 2002; Kausalya et al., 2001; Nielsen et al., 2001, Li et al., 2004; Nielsen et al., 2003). Therefore, it is possible to envision that ZO-1 provides a platform for the localization of Cxs to GJs (Giepmans and Mooelnaar, 1998). In addition, GJs affect TJs proteins as shown by the up-regulation in occludin, claudin-1 and ZO-1 protein levels induced upon transfection of Cx32 into mouse hepatocytes (Kojima et al., 2002). Similarly, over-expression of Cx26 in human airway epithelial cells was associated with elevated levels of claudin-14 (Morita et al., 2004). A direct interaction between polarity proteins and Cxs was recently revealed through Drebrin, a developmentally regulated brain protein. Drebrin is an actin-binding protein involved in mediating cell polarity and maintaining the different plasma membrane domains. The interaction between Cx43 and Drebrin enhances the stability of Cx43 at the membrane since Drebrin's depletion leads to the inhibition of GJ function and Cx43 degradation in Vero cells that are derived from kidney epithelial cells (Butkevich et al., 2004). From the above, it is evident that Cxs are not solely structural proteins of the connexon at the membrane; their coordinated interactions with TJ, AJ and polarity proteins during epithelial differentiation ought to be further scrutinized.

3. Cell Junctions and Polarity in Oncogenesis

Cell junction and polarity proteins are major determinants of differentiation since they mediate communication and establishment of the proper cell architecture; therefore, their disruption is thought to play a key role during tumorigenesis which makes them potential targets for cancer therapy. Hoevel et al. (2004) reported decreased levels of claudins 1, 4, and 6 in two- and three-dimensional cultures of MDA-MB-361, human brain metastatic breast cancer cells, while Osanai et al. (2007) reported that silencing endogenous claudin-6 in MCF7 breast cancer cells increased resistance to oxidant induced apoptosis and promoted anchorage independent growth. On the other hand, over-expression of claudin-1 in MDA-MB-361 cells resulted in enhanced apoptosis and limited proliferative potential (Hoevel et al., 2004). Similar to claudins, lower occludin protein expression was reported in MCF7 cells (Osanai et al., 2007) and was associated with the progression of human endometrial, colorectal and lung carcinomas (Tobioka et al., 2004a,b; Tounaga et al., 2004). Core TJ proteins, like ZO-1 and ZO-2, were also observed to be down-regulated or even lost in breast cancer (Chlenski et al., 2000; Martin et al., 2004). Not only the levels of these proteins were down-regulated, but the membranous delocalization of ZO-1 was also associated with the loss of human mammary epithelial cells' differentiation (Polette et al., 2005). TJ proteins are also differentially modulated in different types of cancer. For example, claudin up-regulation seems to be a major event in breast cancer where the mRNA and protein levels of claudin-3 and −4 were found to be elevated (Soini, 2005; Lanigan et al., 2009). While claudin-7 expression was reported to be highly induced in both primary and metastatic breast tumors (Erin et al., 2009; Sauer et al., 2005), it was down-regulated in other cancers such as head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (Al Moustafa et al., 2002).

Similar to TJ proteins, AJ proteins are also implicated in oncogenesis. E-cadherin's down-regulation was correlated with increased invasiveness of highly invasive epithelial tumor cells of mouse mammary gland origin, which implies an invasion-suppressive property of the gene encoding it, CDH1 (Vleminckx et al., 1991). Clinically, E-cadherin has been reported to be greatly diminished in lobular breast carcinomas and infiltrating luminal and ductal carcinomas (Caldiera et al., 2006). Evidence suggests that AJs proteins such as E-cadherin could also be involved in later stages of oncogenesis by supporting the invasion-metastasis cascade via the regulation of signal transduction pathways that promote cancer progression. Interestingly, in normal human mammary epithelial cells, E-cadherin loss was shown to up-regulate the transcription levels of EMT markers such as Twist and ZEB-1, which are known to be E-cadherin's own repressors. Thus, the loss of E-cadherin enhances metastasis via the up-regulation of its repressors which, in turn, ensures E-cadherin's repression and stabilizes the EMT phenotype during later stages of mammary carcinogenesis (Onder et al., 2008). Catenins are also commonly deregulated in tumors (Cowinet al., 2005). The association of p120-catenin with E-cadherin has been proposed to stabilize AJs at the plasma membrane during the formation of cell–cell contacts. Furthermore, E-cadherin recruits β-catenin from the cytoplasm to the cell membrane and thus, limits its cytoplasmic availability and subsequent translocation to the nucleus where it can inappropriately activate cancer promoting genes (Adamsky et al., 2003).

As for GJ proteins, neoplastic cells are generally known to display decreased levels of Cx expression and/or gap junction intercellular communication (GJIC) which facilitates their release from the controlling regime of the surrounding tissue by preventing direct cell-cell communication, leading to tumor promotion. Consequently, over-expressing Cxs in cancer cells could reduce their tumorigenic potential. For example, Cx43 over-expression in the MDA-MB-231 invasive breast cancer cell line, led to reduced angiogenesis (Qin et al., 2002). In another study, Cx43 over-expression in MDA-MB-231 cells resulted in partial reversion of tumor phenotype with altered three dimensional growth morphology, decreased proliferation rate in 3D culture, and reduced invasiveness. This was accompanied by assembly of GJ complexes at the membrane that kept β-catenin away from the cell nucleus. In 2D cultures of these cells Cx43 overexpression failed to assemble at the membrane, β-catenin maintained a nuclear distribution and cell proliferation was not affected, suggesting a context dependent effect of Cx43 on cell’s phenotype (Talhouk et al., submitted). In an interesting contrast, metastatic cancer cells are often characterized by high levels of Cxs and enhanced gap junctional coupling when they interact with endothelial cells and other cells at the secondary tumor site (Ito et al., 2000). Cx26 and Cx43 expression was elevated in more than 50% of the invasive breast carcinomas, as compared to normal tissue samples. Phosphorylated Cx43, which correlates with the loss of GJ plaques and disruption of intercellular communication, was strongly up-regulated in myoepithelial cells and in situ and invasive breast carcinoma cells (Laird et al., 1995). Interestingly, despite Cxs’ up-regulation in some breast cancers, these proteins remain cytoplasmically localized and do not reach their normal location at the plasma membrane of epithelial cells (reviewed by McLachlan et al., 2007).

Alterations in cell junction proteins are implicated in different stages of progression for several types of cancer. These types of modifications are also associated with other diseases. Disruptions in TJ have been implicated in the pathogenesis of acute and chronic neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s (Zipser et al., 2007), multiple sclerosis (Minagar and Alexander, 2003), stroke (Mark and Davis, 2002), Parkinson’s disease (Kortekaas et al., 2005), and other (Hamdan et al. 2012). In addition, human dilated and ischemic cardiomyopathy has been correlated with a down-regulation of ZO-1 and Cx43 proteins (Laing et al., 2007; Kostin, 2007). The paradox of having a particular protein either up- or down-regulated depending on the stage of oncogenesis indicates that cell junction proteins are not simply down-regulated or misrepresented in cancer. Instead, they appear to be tightly regulated during oncogenesis to support initiation, progression and metastasis. In light of these observations, the possibility that cell junction proteins may act either as tumor suppressors or cancer enhancers depending on the stage of the neoplasia should be highly considered (Lelièvre, 2010; El-Saghir et al., 2011).

The intimate link between cell junctions and polarity proteins is evident; therefore, it is likely that the localization and/or expression of polarity proteins could also be altered during oncogenesis. The modulation of polarity proteins in mammary epithelial cells affects the formation of basoapical polarity and deregulates cellular adhesion leading to breast cancer initiation. For example, Par6 has been shown to be up-regulated in breast cancer-derived cell lines, precancerous breast lesions and advanced primary human breast cancers, and it is able to promote tumor initiation through its interaction with Cdc42 and aPKC (Nolan et al., 2008). On the other hand, loss or mislocalization of Scrib along with the activation of c-myc oncogene blocks apoptosis and induces mammary tumor formation in mouse mammary fat pads (Zhan et al., 2008). A member of the Scribble family, Lgl1, was observed to be down-regulated in breast carcinomas (Grifoni et al., 2004). These data indicate that changes in the levels of expression and/or localization of cell junctions and polarity proteins vary depending on the stage, type and grade of cancer.

Given the above evidence of the impact of the modifications in cell junction and polarity proteins on cancer progression, a number of studies are focusing now on unveiling the mechanisms that govern the deregulation of these proteins, and consequently, the disruption of their downstream signaling pathways in cancer. It is critical to consider the dual roles that these proteins play in differentiation and tumorigenesis, Indeed cancer cells could be utilizing the cell junctions and polarity proteins involved during normal differentiation but in a deregulated manner. This possibility is illustrated by collective cell migration.

4. Cell Junctions and Polarity Proteins: Regulators of Collective Cell Migration

There are two major modes of cell migration in development and cancer. Single cell migration comprises cell polarization, protrusion, attachment, proteolytic degradation of tissue components, actomyosin contraction and, finally, sliding of the cell rear. The migration of single cells allows them to initiate normal tissue development, form secondary tumor growth in oncogenesis and reach infection sites in immune reactions (Ridley et al., 2003). The other mode of cell migration is collective migration which remains mechanistically unclear. Collective cell migration is inclusive of multicellular streaming, expansive growth and tissue folding. These different subtypes of cell migration are defined by a combination of parameters such as cellular morphology, cell–cell adhesion and coordinated cell–cell signaling (Friedl et al., 2012). Whereas the fundamental principles of single cell migration are retained in collective cell movement, cells remain coupled by cell junctions at the leading edge as well as in lateral regions and within the sheet of migrating cells (Friedl at el., 2004). During normal mammary gland development, collectively migrating cells possess intact cell junctions between the leading and the inner cells of the migrating sheet (Teddy and Kulesa, 2004). If these junctions are loosened, cells disperse and migrate individually. In oncogenesis, cancer cells tend to migrate collectively rather than as single cells, notably during EMT (Friedl and Wolf, 2003; Guarino, 2007). For the progression of cancer, cells seem to benefit from collectively migrating compared to dissemination as individual cells. As a collective unit, cancer cells can release more promigratory and matrix protease factors that facilitate their migration. A large mass of heterogeneous cells would also efficiently survive in a hostile environment and better induce the formation of blood vessels enabling them to metastasize (Fidler, 1973).

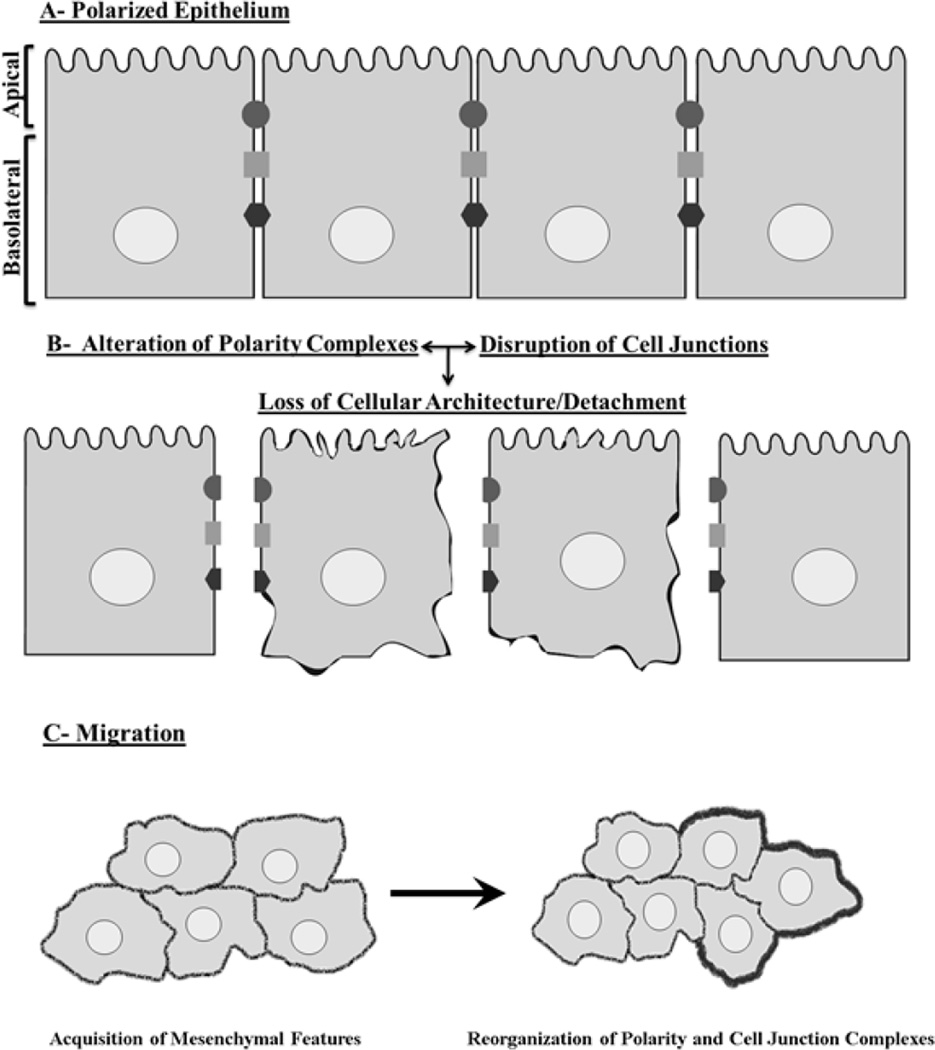

For migration, polarized epithelial cells have to detach from their surroundings following cell junctions’ disassembly and disruption of polarity (Fig. 3A and 3B) (Ridley et al., 2003). This will facilitate the uncontrolled proliferation and multilayering of these cells along with the acquisition of mesenchymal features that enhance their tumorigenecity (Fig. 3C). Throughout migration, they are physically and functionally connected via the maintenance of intact cell junctions (Friedl, 2004; Carmona-Fontaine et al., 2008). Interestingly, invasive tumors are characterized by an abundant expression of cell junction proteins such as N-, E-cadherin and TJ proteins that form complexes at the cell membrane. GJs are more concentrated in tumor cells as compared to normal cells. For example, over-expression of Cx43 in HeLa cells, enhanced communication between cells and increased collective invasiveness (Graeber and Hulser, 1998). Thus, stabilizing cell adhesion and enhancing communication between migrating cells seems to induce a shift from single to collective migration; conversely disrupting cell adhesion disturbs collective migration and disperses the mass into single cells. Although collective cell migration in cancer is a well-documented phenomenon (Friedl et al., 2012), many of the mechanisms that induce the shift from single to collective migration remain insufficiently defined, particularly the role of cell junction proteins and intercellular communication.

Figure 3. Junctions and polarity: Shields against breast cancer.

A. Before cancer initiation, cell junctions as in TJ, AJ, and GJ (black circle, grey square and black hexagon respectively) and polarity proteins are properly expressed and localized. B. Their disruption leads to the loss of cellular architecture and marks the detachment of epithelial cells from each other within the tissue. C. This induces the formation of multilayers of epithelial cells that have acquired mesenchymal features. At this stage, cells need to rearrange their cell junction and polarity proteins to facilitate their collective migration, extravasation and invasion (Friedl, 2004). Throughout collective migration, cells are physically and functionally connected via the maintenance of intact cell junctions and they display a coordinated polarization of the leading edge of the migrating sheet (indicated by the dark thick line) of cells to encompass the increasing volume of the cell mass and the coordinated retraction at the rear end of the group (Friedl and Gillmour ,2009). These dramatic changes in cellular polarity, communication, tissue architecture, gene expression and migratory potential ultimately lead to enhanced cancer progression.

A central property of collective migration of both normal and cancer cells is polarization which is different from the basoapical polarity of epithelial tissues. Coordinated polarization is established by the leading edge of the migrating sheet of cells where cytoskeletal and membrane bound proteins rearrange to accommodate the increasing volume of the cell mass and facilitate the coordinated retraction at the rear end of the group (Fig. 3C) (Friedl and Gilmour, 2009). Migrating cells tend to orient themselves in response to cues from their microenvironment and generate the front-rear axis (Ridley et al., 2003). This phenomenon is regulated by small G-proteins namely Cdc42, Rac and Rho that induce cytoskeletal re-arrangement. For example, following wounding, Cdc42 binds to Par6 and promotes aPKC activation via phosphorylation thereby modifying the polarized organization of microtubules and cell reorientation to enable migration (Pinheiro and Montell, 2004). In cancer, the down-regulation of polarity proteins disturbs the directionality of invasive cancer cells and induces random cell migration (Humbert et al., 2006). Interestingly, the up-regulation of both PKCz and PKCi was reported to perturb directed migration in some types of cancers such as ovarian and human non-small cell lung cancer, which in turn, decreased the cancer aggressiveness (Eder et al., 2005; Regala et al., 2005). A recent report revealed the importance of polarity proteins, Par3 and Par6, in the collective migration of cancer cells. Both were found to bind to Depletion of Discoidin Domain Receptor 1 (DDR1) at cell-cell contacts in epidermal carcinoma. The DDR1-Par3/Par6 cell-polarity complex acted by localizing RhoE to cell–cell contacts hence antagonized ROCK-driven actomyosin contractility, which enhanced the invasiveness of the cancer cells (Hidalgo-Carcedo et al., 2010). Clearly, cell junction formation and polarity are not only essential for a differentiated epithelial phenotype, they are also central coordinators of carcinogenesis as cancer cells need communication, adhesion and adequate repolarization to maintain cancer progression and promote metastasis. These functional alterations might be explained in part by the capacity of polarity proteins to induce epigenetic changes in genes that regulate phenotypes.

5. Cell Polarity and Epigenetics

The cellular architecture that results from the establishment of proper cell junctions and polarity is ultimately linked to the cell nucleus (Lelièvre, 2010), and impacts the expression of genes related to proliferation, differentiation and cellular homeostasis. It has been well established that the disruption of apical polarity and formation of more than one layer of epithelial cells, is an early event in cancer development. The loss of apical polarity is illustrated at the molecular level by the mislocalization of cell junctions and polarity proteins, and one of its early effects is the priming of cells to enter the cell cycle (Chandramouly et al., 2007). Studies have been initiated to explore the potential role of cell polarity proteins in the epigenetic control of gene expression. Here, we define epigenetics as the chromatin-based mechanisms that determine the level of gene transcription. The consequence of epigenetic regulation is the plethora of cell phenotypes present in an individual despite of a genetic code shared by all the cells in that individual (Katto and Mahlknecht, 2011). Epigenetic modifications can be induced via signaling pathways emanating from cell membrane bound receptors or via the release of epigenetic modifiers normally trapped at cell junctions (Lelièvre, 2010).

Par proteins have been correlated with epigenetic modifications. For example, Par6 has been reported to activate the ras-MAPK pathway in oncogene-transformed fibroblasts, leading to an increased phosphorylation of histones H1 and H3; consequently, the chromatin microenvironment of cancer promoting genes such as c-myc and c-fos, acquired a more relaxed structure leading to their over-expression (Dunn et al., 2005). Scrib was shown to modify LPP, a zyxin-related protein, which then translocated to the nucleus where it activated genes encoding proteases implicated in breast cancer metastasis (Petit et al., 2000; Guo et al., 2006). Dlg is another member of the scribble family that influences the epigenome. It forms a complex with tumor suppressor adenomatous polyposis coli enabling G0/G1 to S cell cycle transition blockage via an association with euchromatin and a change in the accessibility of polymerases to target genes (Ishidate et al., 2000). TJs, the guardians of apical polarity, also possess proteins that can interact with the epigenome. Core TJs proteins ZO-1 and ZO-2 have been documented to translocate to the cell nucleus. Specifically, upon loss of apical polarity the presence of these proteins in the nucleus has been linked to oncogenic effects. ZO-1 has an indirect epigenetic effect as well, via ZONAB, a y-box protein ZO-1 nucleic acid binding protein. When ZO-1 was down-regulated by RNA interference, ZONAB became free to enter the nucleus and induce the transcription of histone 4 and high mobility group I protein, consequently affecting the epigenetic makeup of cancer related genes such as c-jun, c-myc, PCNA and cyclin D1 (Sourisseau et al., 2006). Interestingly, it was recently reported that breast tumors (known for their lack of apical polarity) displayed high levels of nuclear ZONAB (Sharp et al., 2008). Another report indicated that ZO-2 was involved in the repression of cell cycle genes such as cyclin D1 via the recruitment of histone deacetylase 1 at its gene promoter region (Huerta et al., 2007).

The role of these polarity proteins in mediating epigenetic changes is dependent on cell junctions. When the cell contacts are in place, polarity proteins favor tumor suppression by maintaining the local chromatin environment in a state permissive for the silencing of oncogenes and the activation of tumor suppressors. If cell junctions are shuffled and modulated as it is the case in cancer cells, downstream effectors of cell junctions and polarity proteins propagate aberrant signals to the nucleus and favor the inappropriate transcription of oncogenes and the silencing of tumor suppressors, consequently promoting modifications necessary for cancer development.

6. Cell Junctions Proteins as Potential Targets for Therapy

Cancer therapy is to a great extent complicated by drug resistance that results from multiple mechanisms such as increased drug efflux, modified drug metabolism, mutations in drug targets and activation of downstream signal transduction pathways. This is partly prompted by epigenetics that brings about a heterogeneous population of cancer cells, which further complicates therapy (Wilting and Dannenberg, 2012). Given that cellular adhesion can either promote or prevent cancerous behavior by modulating gene expression, cell junction proteins are potentially effective targets for cancer therapy. Despite the regulatory influences that junctions display in normal morphogenesis and cancer development, there is a paucity of drugs targeting junction proteins on the market. Studies are ongoing to examine the effectiveness of potential drugs targeting cell junction proteins, such as that of GJs and TJs, in cancer therapy. Claudin-3 and −4 were found to be up-regulated in neoplasia and to induce cell sensitivity to Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin. The ability of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin to lyse cells over-expressing claudin-3 and −4 makes it a potentially effective treatment of preneoplastic lesions such as ductal carcinoma in situ and locally advanced breast carcinoma that are known to have elevated levels of claudins (Kominsky et al., 2004). Claudins-3 and −4 over-expressed in breast cancer could also be targeted by antibodies that would mark claudin-3 and −4 over-expressing cancer cells for clearance by the immune system (Offner et al., 2005). In addition, monoclonal antibody KM3900 (IgG2a) against claudin-4 significantly inhibited xenograft tumor growth from human ovarian and pancreatic cancer cell lines in SCID mice indicating a potentially promising therapy against both ovarian and pancreatic cancers (Suzuki et al., 2009). Coexpression of thymidine kinase and E-cadherin genes have been linked to improved cytotoxicity of ganciclovir, a synthetic guanine derivative active against cytomegalovirus, in pancreatic tumor xenografts, thus enhancing thymidine kinase/ganciclovir therapy (Garcia-Rodríguez et al., 2011). Connexins are also considered new potential targets in anticancer therapy. A recent patent by Nojima et al. (2010) was released for a multimeric oleamide derivative which displays Cx26 inhibiting activity and exhibits high cancer metastasis inhibitory potentials in melanoma cells. The combination of tamoxifen and retinoic acid, which are synthetic retinoids, enhanced GJIC with a concomitant localization of Cx26 and Cx43 at cell-cell contacts in MCF-7 cells; moreover, this phenomenon correlated with an inhibition of proliferation, accumulation of cells primarily in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle, increase in E-cadherin levels and a reduction of telomerase activity leading to a partial reversion of the tumor phenotype (Saez et al., 2003). Furthermore, it was demonstrated that combinational treatment of T47D breast cancer cells with tamoxifen and PQ1 increased tamoxifen efficacy. PQ1, a substituted quinoline and a gap junction activator, increased GJIC and consequently facilitated the intercellular passage and rapid action of tamoxifen, which in turn, decreased cancer cell proliferation and colony growth (Gakhar et al., 2010).

Despite the anti-cancer effects discussed above, introducing therapeutic agents against cell junction proteins might present some adverse tumor promoting effects. This is due to the fact that these drugs can induce drug resistance, apoptosis resistance and survival-signaling. Drug resistance is associated with the fact that some of the targeted cancer cells are not proliferating or have failed to establish cell adhesion and communication with neighboring cancer cells or with the ECM, which renders the drug ineffective (Tsuruo et al., 2005). It will be critical to take into account the specificity of the cancer type and tumor heterogeneity to improve targeted treatments. A full understanding of the tumor dynamics as well as the development of more effective therapeutic agents will require a detailed analysis of how cell junctions and polarity proteins are modulated in relation to the genetic predisposition of the patient.

7. Conclusion

There is an immense body of knowledge demonstrating that cues from the cellular microenvironment including growth factors, hormones, cell-cell or cell-extracellular matrix interactions are essential for proper function of the mammary gland. These signals modulate polarity pathways that, in turn, ensure the formation and maintenance of cell junctions during epithelial morphogenesis. Even though cell junction and polarity proteins are considered as tumor suppressor genes, they have also been shown to play tumor promoting roles depending on the stage of cancer progression. A possible explanation for their dual role is the involvement of these proteins in the epigenetic control of the expression of genes involved in cell proliferation, differentiation and migration. The molecular mechanisms through which cell junction and polarity proteins execute their effects in the normal and the carcinogenic contexts are yet to be scrutinized as both groups of proteins could serve as effective targets for drug therapy in a number of carcinomas, including breast cancer. The fact that cell junction and polarity proteins are intertwined and regulate key signaling pathways for the control of tissue homeostasis makes the development of therapies targeted toward these proteins a tremendous challenge since tumor promoting effects might be difficult to avoid.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Elia El-Habre for critical reading of the manuscript. We wish to acknowledge the American University of Beirut Research Board and the Lebanese National Council for Scientific Research (to RST and DB); the Purdue Center for Cancer Research and the National Institutes of Health (award # CA112017 to SAL) and the UNESCO-L'ORÉAL International Fellowship for Women in Science-2012 (to DB).

Abbreviations

- AJ

Adherens Junction

- Cx

Connexin

- EMT

Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition

- GJ

Gap Junction

- GJIC

Gap Junction Intercellular Communication

- JAM

Junctional Adhesion Molecule

- MDCK

Madin-Darby Canine idney Epithelial Cells

- TJ

Tight Junction

- ZO

Zonula occludens

- ZONAB

ZO-1 Nucleic Acid Binding Protein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adamsky K, Arnold K, Sabanay H, Peles E. Junctional protein MAGI-3 interacts with receptor tyrosine phosphatase beta (RPTP beta) and tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins. Journal of Cell Science. 2003;116:1279–1289. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Moustafa AE, Alaoui-Jamali MA, Batist G, Hernandez-Perez M, Serruya C, Alpert L, et al. Identification of genes associated with head and neck carcinogenesis by cDNA microarray comparison between matched primary normal epithelial and squamous carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:2634–2640. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios-Rodiles M, Brown KR, Ozdamar B, Bose R, Liu Z, Donovan RS, et al. High throughput mapping of a dynamic signaling network in mammalian cells. Science. 2005;307:1621–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.1105776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betschinger J, Mechtler K, Knoblich JA. The Par complex directs asymmetric cell division by phosphorylating the cytoskeletal protein Lgl. Nature. 2003;422:326–330. doi: 10.1038/nature01486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradfield PF, Nourshargh S, Aurrand-Lions M, Imhof BA. JAM family and related proteins in leukocyte migration (Vestweber series) Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2007;27:2104–2112. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.147694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Cordero JJ, Hodgson L, Condeelis J. Directed cell invasion and migration during metastasis. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2012;24:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen N, Gentleman JF, Schiller JS. Update on mammography trends: comparisons of rates in 2000, 2005, and 2008. Cancer. 2011;117:2209–2218. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butkevich E, Hülsmann S, Wenzel D, Shirao T, Duden R, Majoul I. Drebrin is a novel connexin-43 binding partner that links gap junctions to the submembrane cytoskeleton. Current Biology. 2004;14:650–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira JR, Prando EC, Quevedo FC, Neto FA, Rainho CA, Rogatto SA. CDH1promoter hypermethylation and E-cadherin protein expression in infiltrating breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldo CT, Macara IG. Depletion of E-cadherin disrupts establishment but not maintenance of cell junctions in Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cells. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2010;18:189–200. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona-Fontaine C, Matthews CK, Kuriyama S, Moreno M, Dunn GA, Parsons M, et al. Contact inhibition of locomotion in vivo controls neural crest directional migration. Nature. 2008;456:957–961. doi: 10.1038/nature07441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandramouly G, Abad P, Knowles D, Lelièvre S. The control of tissue architecture over nuclear organization is crucial for epithelial cell fate. Journal of Cell Science. 2007;120:1596–1606. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba H, Osanai M, Murata M, Kojima T, Sawada N. Transmembrane proteins of tight junctions. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2008;1778:588–600. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chlenski A, Ketels KV, Korovaitseva GI, Talamonti MS, Oyasu R, Scarpelli DG. Organization and expression of the human zo-2 gene (tjp-2) in normal and euplastic tissues. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2000;1493:319–324. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(00)00185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowing P, Rowland's TM, Hat sell SJ. Catherin's and catena's in breast cancer. Current Opinions in Cell Biology. 2005;17:499–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dbouk HA, Mroue RM, El-Sabban ME, Talhouk RS. Connexins: a myriad of functions extending beyond assembly of gap junction channels. Cell Communication and Signaling. 2009;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson DJ, Nelson WJ, Weis WI. A polarized epithelium organized by beta and alpha-catenin predates cadherin and metazoan origins. Science. 2011;331:1336–1339. doi: 10.1126/science.1199633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow LE, Elsum IA, King CL, Kinross KM, Richardson HE, Humbert PO. Loss of human Scribble cooperates with H-Ras to promote cell invasion through deregulation of MAPK signaling. Oncogene. 2008;27:5988–6001. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KL, Espino PS, Drobic B, He S, Davie JR. The Ras-MAPK signal transduction pathway, cancer and chromatin remodeling. Biochemical Cell Biology. 2005;83:1–14. doi: 10.1139/o04-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebnet K. Organization of multiprotein complexes at cell-cell junctions. Histochemical Cell Biology. 2008;130:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0418-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eder AM, Sui X, Rosen DG, Nolden LK, Cheng KW, Lahad JP, et al. Atypical PKCiota contributes to poor prognosis through loss of apical-basal polarity and cyclin E overexpression in ovarian cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2005;102:12519–12524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505641102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebnet K, Suzuki A, Ohno S, Vestweber D. Junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs): more molecules with dual functions? Journal of Cell Science. 2004;117:19–29. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich JS, Hansen MD, Nelson WJ. Spatio-temporal regulation of Rac1 localization and lamellipodia dynamics during epithelial cell–cell adhesion. Developmental Cell. 2002;3:259–270. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sabban ME, Abi-Mosleh LF, Talhouk RS. Developmental regulation of gap junctions and their role in mammary epithelial cell differentiation. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2003;8:463–473. doi: 10.1023/B:JOMG.0000017432.04930.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Saghir JA, El-Habre ET, El-Sabban ME, Talhouk RS. Connexins: a junctional crossroad to breast cancer. International Journal of Developmental Biology. 2011;55:773–780. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.113372je. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erin N, Wang N, Xin P, Bui V, Weisz J, Barkan GA, et al. Altered gene expression in breast cancer liver metastases. International Journal of Cancer. 1973;124:1503–1516. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler IJ. The relationship of embolic homogeneity, number, size and viability to the incidence of experimental metastasis. European Journal of Cancer. 1973;9:223–237. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2964(73)80022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogg VC, Liu CJ, Margolis B. Multiple regions of Crumbs3 are required for tight junction formation in MCF10A cells. Journal of Cell Science. 2005;118:2859–2869. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley J, Dann P, Hong J, Cosgrove J, Dreyer B, Rimm D, et al. Parathyroid hormone-related protein maintains mammary epithelial fate and triggers nipple skin differentiation during embryonic breast development. Development. 2001;128:513–525. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P. Prespecification and plasticity: shifting mechanisms of cell migration. Current Opinions in Cell Biology. 2004;16:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, Gilmour D. Collective cell migration in morphogenesis, regeneration and cancer. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2009;10:445–457. doi: 10.1038/nrm2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, Hegerfeldt Y, Tusch M. Collective cell migration in morphogenesis and cancer. International Journal of Developmental Biology. 2004;48:441–449. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041821pf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, Locker J, Sahai E, Segall JE. Classifying collective cancer cell invasion. Nature Cell Biology. 2012;14:777–783. doi: 10.1038/ncb2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, Wolf K. Tumour-cell invasion and migration: diversity and escape mechanisms. Nature Review Cancer. 2003;3:362–374. doi: 10.1038/nrc1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gakhar G, Hua DH, Nguyen TA. Combinational treatment of gap junctional activator and tamoxifen in breast cancer cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2010;21:77–88. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328333d557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rodríguez L, Abate-Daga D, Rojas A, González JR, Fillat C. E-cadherin contributes to the bystander effect of TK/GCV suicide therapy and enhances its antitumoral activity in pancreatic cancer models. Gene Therapy. 2011;18:73–81. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassama-Diagne A, Yu W, terBeest M, Martin-Belmonte F, Kierbel A, Engel J, et al. Phosphatidylinositol-3, 4, 5- trisphosphate regulates the formation of the basolateral plasma membrane in epithelial cells. Nature Cell Biology. 2006;8:963–970. doi: 10.1038/ncb1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giepmans BN, Moolenaar WH. The gap junction protein connexin43 interacts with the second PDZ domain of the zona occludens-1 protein. Current Biology. 1998;8:931–934. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giepmans BN, Ijzendoorn SC. Epithelial cell-cell junctions and plasma membrane domains. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1788:820–831. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeber SH, Hülser DF. Connexin transfection induces invasive properties in HeLa cells. Experimental Cell Research. 1998;243:142–149. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grifoni D, Garoia F, Schimanski CC, Schmitz G, Laurenti E, Galle PR, et al. The human protein Hugl-1 substitutes for Drosophila lethal giant larvae tumour suppressor function in vivo. Oncogene. 2004;23:8688–8694. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarino M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumour invasion. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2007;39:2153–2160. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B, Sallis RE, Greenall A, Petit MM, Jansen E, Young L, et al. The LIM domain protein LPP is a coactivator for the ETS domain transcription factor PEA3. Molecular Cell Biology. 2006;26:4529–4538. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01667-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman JA, Finlay BB. Tight junctions as targets of infectious agents. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2009;1788:832–841. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan R, Yehia M, Talhouk RS, El-Sabban ME. Pathophysiology of Gap Junctions in the Brain. In Gap Junctions in the Brain. Chapter 3, pages 31–46. In: Ekrem Dere., editor. Gap Junctions in the Brain; Physiological and Pathological Roles. 2012. p. 301. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen RK, Bissell MJ. Tissue architecture and breast cancer: the role of extracellular matrix and steroid hormones. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2000;7:95–113. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0070095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hens JR, Wysolmerski JJ. Key stages of mammary gland development: molecular mechanisms involved in the formation of the embryonic mammary gland. Breast Cancer Research. 2005;7:220–224. doi: 10.1186/bcr1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herve JC, Bourmeyster N, Sarrouilhe D. Diversity in protein-protein interactions of connexins: Emerging roles. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2004;1662:22–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Carcedo C, Hooper S, Chaudhry SI, Williamson P, Harrington K, Leitinger B, et al. Collective cell migration requires suppression of actomyosin at cell-cell contacts mediated by DDR1 and the cell polarity regulators Par3 and Par6. Nature Cell Biology. 2011;13:49–58. doi: 10.1038/ncb2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoevel T, Macek R, Swisshelm K, Kubbies M. Reexpression of the TJ protein CLDN1 induces apoptosis in breast tumor spheroids. International Journal of Cancer. 2004;108:374–383. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta M, Munoz R, Tapia R, Soto-Reyes E, Ramirez L, Recillas-Targa F, et al. Cyclin D1 is transcriptionally downregulated by ZO-2 via an E box and the transcription factor c-Myc. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2007;18:4826–4836. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbert PO, Dow LE, Russell SM. The Scribble and Par complexes in polarity and migration: friends or foes? Trends in Cell Biology. 2006;16:622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishidate T, Matsumine A, Toyoshima K, Akiyama T. The APChDLG complex negatively regulates cell cycle progression from the G0/G1 to S phase. Oncogene. 2000;19:365–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito A, Katoh F, Kataoka TR, Okada M, Tsubota N, Asada H, et al. A role for heterologous gap junctions between melanoma and endothelial cells in metastasis. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;105:1189–1197. doi: 10.1172/JCI8257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kausalya PJ, Reichert M, Hunziker W. Connexin45 directly binds to ZO-1 andlocalizes to the tight junction region in epithelial MDCK cells. FEBS Letters. 2001;505:92–96. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02786-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katto J, Mahlknecht U. Epigenetic regulation of cellular adhesion in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1414–1418. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima T, Spray DC, Kokai Y, Chiba H, Mochizuki Y, Sawada N. Cx32 formation and/or Cx32-mediated intercellular communication induces expression and function of tight junctions in hepatocytic cell line. Experimental Cell Research. 2002;276:40–51. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kominsky SL, Vali M, Korz D, Gabig TG, Weitzman SA, Argani P, et al. Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin elicits rapid and specific cytolysis of breast carcinoma cells mediated through tight junction proteins claudin 3 and 4. American Journal of Pathology. 2004;164:1627–1633. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63721-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortekaas R, Leenders KL, van Oostrom JC, Vaalburg W, Bart J, Willemsen AT, et al. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction in parkinsonian midbrain in vivo. Annals of Neurology. 2005;57:176–179. doi: 10.1002/ana.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostin S. Zonula occludens-1 and connexin 43 expression in the failing human heart. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2007;11:892–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00063.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing JG, Saffitz JE, Steinberg TH, Yamada KA. Diminished zonula occludens-1 expression in the failing human heart. Cardiovascular Pathology. 2007;16:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird DW, Castillo M, Kasprzak L. Gap junction turnover, intracellular trafficking, and phosphorylation of connexin43 in brefeldin A-treated rat mammary tumor cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1995;131:1193–1203. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.5.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanigan F, McKiernan E, Brennan DJ, Hegarty S, Millikan RC, McBryan J, et al. Increased claudin-4 expression is associated with poor prognosis and high tumour grade in breast cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2009;124:2088–2097. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laprise P, Viel A, Rivard N. Human homolog of disc-large is required for adherens junction assembly and differentiation of human intestinal epithelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:10157–10166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309843200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelièvre SA. Tissue Polarity-Dependent Control of Mammary Epithelial Homeostasis and Cancer Development: an Epigenetic Perspective. Chemistry. 2010;279:10157–10166. doi: 10.1007/s10911-010-9168-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Ionescu AV, Lynn BD, Lu S, Kamasawa N, Morita M, et al. Connexin47, connexin29 and connexin32 coexpression in oligodendrocytes and Cx47 association with zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) in mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2004;126:611–630. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Olson C, Lu S, Kamasawa N, Yasumura T, Rash JE, et al. Neuronal connexin36 association with zonula occludens-1 protein (ZO-1) in mouse brain and interaction with the first PDZ domain of ZO-1. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;19:2132–2146. doi: 10.1111/j.l460-9568.2004.03283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macara IG. Parsing the polarity code. Nature Review Molecular Cell Biology. 2004;5:220–231. doi: 10.1038/nrm1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell KJ, Babbin BA, Nusrat A, Parkos CA. Junctional adhesion molecule 1 regulates epithelial cell morphology through effects on β1 integrins and Rap1 activity. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:11665–11674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412650200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark KS, Davis TP. Cerebral microvascular changes in permeability and tight junctions induced by hypoxia-reoxygenation. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2002;282:1485–1494. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00645.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TA, Jiang WG. Loss of tight junction barrier function and its role in cancer metastasis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1788:872–891. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TA, Watkins G, Mansel RE, et al. Loss of tight junction plaque molecules in breast cancer tissues is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2004;40:2717–2725. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Belmonte F, Gassama A, Datta A, Yu W, Rescher U, Gerke V, et al. PTEN-mediated segregation of phosphoinositides at the apical membrane controls epithelial morphogenesis through Cdc42. Cell. 2007;128:383–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan E, Shao Q, Laird DW. Connexins and gap junctions in mammary gland development and breast cancer progression. Journal of Membrane Biology. 2007;218:107–121. doi: 10.1007/s00232-007-9052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minagar A, Alexander JS. Blood-brain barrier disruption in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis. 2003;9:540–549. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms965oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery E, Mamelak AJ, Gibson M, Maitra A, Sheikh S, Amr SS, et al. Overexpression of claudin proteins in esophageal adenocarcinoma and its precursor lesions. Applied Immunohistochemistry & Molecular Morphology. 2006;14:24–30. doi: 10.1097/01.pai.0000151933.04800.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita H, Katsuno T, Hoshimoto A, Hirano N, Saito Y, Suzuki Y. Connexin 26- mediated gap junctional intercellular communication suppresses paracellular permeability of human intestinal epithelial cell monolayers. Experimental Cell Research. 2004;298:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M, Fukata M, Yamaga M, Itoh N, Kaibuchi K. Recruitment and activation of Rac1 by the formation of Ecadherin- mediated cell-cell adhesion sites. Journal of Cell Science. 2001;114:1829–1838. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.10.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro C, Nola S, Audebert S, Santoni MJ, Arsanto JP, Ginestier C, et al. Junctional recruitment of mammalian Scribble relies on E-cadherin engagement. Oncogene. 2005;24:4330–4339. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson WJ. Adaptation of core mechanisms to generate cell polarity. Nature. 2003;422:766–774. doi: 10.1038/nature01602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen PA, Baruch A, Giepmans BN, Kumar NM. Characterization of the association of connexins and ZO-1 in the lens. Cell Communication and Adhesion. 2001;8:213–217. doi: 10.3109/15419060109080726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen PA, Baruch A, Shestopalov VI, Giepmans BN, Dunia I, Benedetti EL, et al. Lens connexins alpha3Cx46 and alpha8Cx50 interact with zonula occludens protein-1 (ZO-1) Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2003;14:2470–2481. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen PA, Beahm DL, Giepmans BN, Baruch A, Hall JE, Kumar NM. Molecular cloning, functional expression, and tissue distribution of a novel human gap junction forming protein, connexin-31.9.Interaction with zonula occludens protein-1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:38272–38283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nojima H, Ohba Y, Kita Y. Oleamide derivatives are prototypical anti-metastasis drugs that act by inhibiting Connexin 26. Current Drug Safety. 2010;2:204–211. doi: 10.2174/157488607781668837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan ME, Aranda V, Lee S, Lakshmi B, Basu S, Allred DC, et al. The polarity protein Par6 induces cell proliferation and is overexpressed in breast cancer. Cancer Research. 2008;68:8201–8209. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusrat A, Brown GT, Tom J, Drake A, Bui TT, Quan C, et al. Multiple protein interactions involving proposed extracellular loop domains of the tight junction protein occludin. Molecular biology of the Cell. 2005;16:1725–1734. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offner S, Hekele A, Teichmann U, Weinberger S, Gross S, Kufer P, et al. Epithelial tight junction proteins as potential antibody targets for pancarcinoma therapy. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2005;5:431–445. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0613-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onder TT, Gupta PB, Mani SA, Yang J, Lander ES, Weinberg RA. Loss of E-Cadherin Promotes Metastasis via Multiple Downstream Transcriptional Pathways. Cancer Research. 2008;68:3645–3654. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osanai M, Murata M, Nishikiori N, Chiba H, Sawada N. Epigenetic silencing of claudine-6 promotes anchorage independent growth of breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Research. 2007;98:1557–1562. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pece S, Gutkind JS. Signaling from E-cadherins to the MAPK Pathway by the Recruitment and Activation of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptors upon Cell-Cell Contact Formation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:41227–41233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006578200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit MM, Fradelizi J, Golsteyn RM, Ayoubi TA, Menichi B, Louvard D, et al. LPP, an actin cytoskeleton protein related to zyxin, harbors a nuclear export signal and transcriptional activation capacity. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2000;11:17–29. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro EM, Montell DJ. Requirement for Par-6 and Bazooka in Drosophila border cell migration. Development. 2004;131:5243–5251. doi: 10.1242/dev.01412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polette M, Gilles C, Nawrocki-Raby B, Lohi J, Hunziker W, Foidart JM, et al. Membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase expression is regulated by zonula occludens-1 in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2005;65:7691–7698. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H, Shao Q, Curtis H, Galipeau J, Belliveau DJ, Wang T, et al. Retroviral delivery of connexin genes to human breast tumor cells inhibits in vivo tumor growth by a mechanism that is independent of significant gap junctional intercellular communication. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:29132–29138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]