Abstract

Introduction

The aim of the study was to assess the role of patient counselling, nurse assistance and effects of biochemical examinations in adherence of women with postmenopausal osteoporosis to alendronate 70 administration over 12 months of therapy.

Material and methods

Compliance and persistence to alendronate 70 therapy were assessed in a prospective study of 123 postmenopausal women, followed up for one year. The patients were divided into 4 groups (controls, counselled group, biochemical group and nurse assisted group) with monitoring every 6 months; in the nurse assisted group, additional phone contacts were made after 3 and 9 months of treatment. After 12 months, compliance and persistence were analysed. The medication possession ratio (MPR) was regarded as optimal when its value exceeded 80%.

Results

The compliance to alendronate 70 therapy was 54.03% in the control group and the mean persistence with medication was 197 days. The MPR above 80% was observed in 37.5%, and, after 1 year, 43.75% of patients were found persistent with the therapy. In the remaining groups, both compliance and persistence were higher but not statistically significantly, compared to the control group. Neither patient's age, education, diet, nor physical activity influenced the compliance with prescribed therapy. The most common reason to discontinue therapy was either its side effects or smoking.

Conclusions

The obtained results suggest that better adherence with medical recommendations is observed in patients who receive additional attention, e.g. counselling, biochemical tests or nursing care. The critical elements for therapy discontinuation were side effects and smoking.

Keywords: alendronate, adherence, persistence, reasons for therapy discontinuation

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a major public health problem, especially in the older group of women in many countries, including Poland [1]. Currently available treatment options increase bone mineral density (BMD) and decrease fracture risk [2–7]. In order to obtain the desired medication benefit, treated patients should maintain optimal compliance and persistence with their osteoporosis therapy [8–12]. There are some negative consequences of poor adherence, which is a sum of compliance to and persistence with prescribed treatment [11, 13–16].

It has been shown that more than 50% of people affected by chronic diseases, including osteoporosis, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia, discontinue treatment during the first year of its administration [17]. This problem increases with the time of follow-up. It has been observed that 13% of women treated with daily oral alendronate did not even start the therapy and 20% of patients discontinued the treatment of weekly alendronate during the first 4 months and 17% within 6 months [18, 19].

Previous retrospective studies of large databases have provided much evidence for poor adherence to recommended osteoporosis therapies. While persistence with daily bisphosphonate therapy has been observed in 25% to 35% of patients during the 1st year of its administration, the persistence with weekly bisphosphonate treatment ranges between 35% and 45% [14].

This problem concerns not only bisphosphonates but also other osteoporosis therapies [14]. Bocuzzi et al. [20] presented results of a 1-year study, involving a cohort of 10,566 women, showing that their adherence was higher with two bisphosphonates, daily alendronate (60.7%) and daily risedronate (58.4%), while lower adherence was observed with raloxifene (53.9%). The persistence rate was, however, poor for all the agents (daily alendronate – 23%, daily risedronate – 19.4% and raloxifene – 16.2%). Other authors have observed somewhat better adherence in the following three examined countries [21]: the United States – 32%, UK – 40%, and France – 44% Women on daily alendronate persisted with the treatment for 185 days in the United States, 208 in the United Kingdom and 155 in France [21]. The persistence curves for osteoporosis treatment showed a rapid decrease within the first 3 months of starting therapy [18–20]. Similarly, a retrospective study of postmenopausal women on daily alendronate, calcitonin, hormone replacement therapy (HRT), raloxifene or risedronate showed their compliance below 66% during a 60-day period [22], which resulted in suboptimal outcomes regarding bone mineral density [23].

Poor treatment adherence considerably increases the risk of fracture(s), with the associated financial burden, generated by osteoporosis therapy. It is then worth searching for some non-pharmaceutical interventions for adherence improvement.

The aim of this study was to assess the effects of counselling, nurse assistance (better monitoring of therapy), and biochemical examinations on the adherence of women with postmenopausal osteoporosis to recommended alendronate 70 administration protocol over the period of 12 months, monitored in 6-month intervals.

Material and methods

Compliance to and persistence with alendronate 70 therapy were assessed in a prospective study of 123 postmenopausal women (aged 46 to 89 years), all of them followed up for 1 year. All the participating women were either antiresorptive drug-naïve or had, at least, a 1-year break in therapy before the study onset. Each of the women was informed about osteoporosis and signed a consent form to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria comprised bone mineral density ≤ –2.5 SD in hip or spine and/or osteoporotic fracture(s), either diagnosed or in history.

The exclusion criteria included: (1) current treatment with bisphosphonates or their use for the past 12 months; (2) chronic medication affecting bone turnover, including: glucocorticoids, antiepileptic drugs, aromatase inhibitors, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, and chemotherapy; (3) endocrine disorders significantly affecting the processes of bone resorption and formation, including: hyperparathyroidism, active hyperthyroidism, hyperprolactinaemia and hypogonadism; (4) chronic renal failure; (5) malabsorption; (6) active cancer or other chronic systemic diseases, which may significantly affect bone metabolism; (7) no written consent to participate in the study.

The patients were divided into 4 groups (controls, counselled group, biochemical group and nurse assisted group) with monitoring in 6-month intervals; in the nurse assisted group, an additional phone contact was made after 3 and 9 months of treatment to improve monitoring. During the phone call the compliance was checked and the patients were reminded of proper drug intake. In the counselled group, the patients were educated and interviewed for 1/2 h about osteoporosis, diagnostic methods, treatment and preventive behaviour, using auxiliary materials. In the biochemical group, the patients were informed about serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase and of urinary calcium and phosphorus concentration levels and diurnal excretion rates. The baseline characteristics of the patients in each group are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the patients in all studied groups

| Parameter | Control group | Nurse assisted group | Counselled group | Biochemical group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD [years] | 68.7 ±10.05 | 67.83 ±10.67 | 67.9 ±10.09 | 63.03 ±10.03 |

| BMI, mean ± SD [kg/m2] | 28.24 ±4.6 | 27.74 ±3.81 | 28.29 ±4.49 | 25.63 ±3.07 |

| Neck BMD, mean ± SD [g/cm2] | 0.653 ±0.056 | 0.667 ±0.072 | 0.639 ±0.067 | 0.642 ±0.087 |

| Neck T-score, mean ± SD | −2.86 ±0.451 | −2.75 ±0.608 | −2.96 ±0.571 | −2.96/0.643 |

| L2-L4 BMD, mean ± SD [g/cm2] | 0.799 ±0.13 | 0.818 ±0.148 | 0.769 ±0.433 | 0.784 ±0.129 |

| L2-L4 T-score, mean ± SD | −1.9 ±0.81 | −1.7 ±0.91 | −1.5 ±0.89 | −2.0 ±0.8 |

| Vertebral fractures [%/n] | 13/4 | 6/2 | 41/12 | 19/6 |

| Hip fractures [%/n] | 0/0 | 0.03/1 | 0/0 | 0.03/1 |

| Forearm fractures [%/n] | 28.1/9 | 45.1/14 | 44.8/13 | 1.29/4 |

| Smoking [%/n] | 20/6 | 10/4 | 10/2 | 20/5 |

| Glucocorticoids [%/n] | 12.5/4 | 9.7/3 | 17.2/5 | 0.03/1 |

The outcome measures after 12 months of the study included: (1) compliance; (2) persistence and (3) refill rates. Persistence was defined as the time in days from the date of bisphosphonate prescription to the run-out date in the treatment period. Patients were defined as “persistent” until a gap of > 90 days was reached between the end of one prescribed drug series and the date of subsequent prescription or until the patient switched to another bisphosphonate or had a refill gap > 30 days between the end of one prescription series and the beginning of the subsequent one. The refill compliance was defined as the medication possession ratio (MPR), measured during follow-up (the number of days with applied therapy within the 12-month follow-up period, divided by the length of follow-up, namely 365 days); 80% was regarded as an optimal value.

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics were collected for baseline characteristics, including age, the number of used drugs, education, monthly income, physical activity, residence location (urban or rural), or the number of persons in the family. The primary analysis included comparisons of compliance, persistence and the time period to therapy discontinuation among the four examined groups, using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests. The MPRs were categorized into two kinds for each group: MPR ≥ 80% and < 80%. In order to compare good compliance and persistence among the groups, the χ2 test was used. A sub-analysis was performed for patients who were above 65 years of age. A Cox proportional hazards analysis was used to assess the impact of age, the number of used drugs, education, monthly income, physical activity, residence location (urban or rural), number of persons in family, spine or hip fracture(s), body mass index (BMI), fracture history in family, smoking and therapy side effects. The time to discontinuation of alendronate 70 was analysed using a Kaplan-Meier plot with a log-rank test.

Results

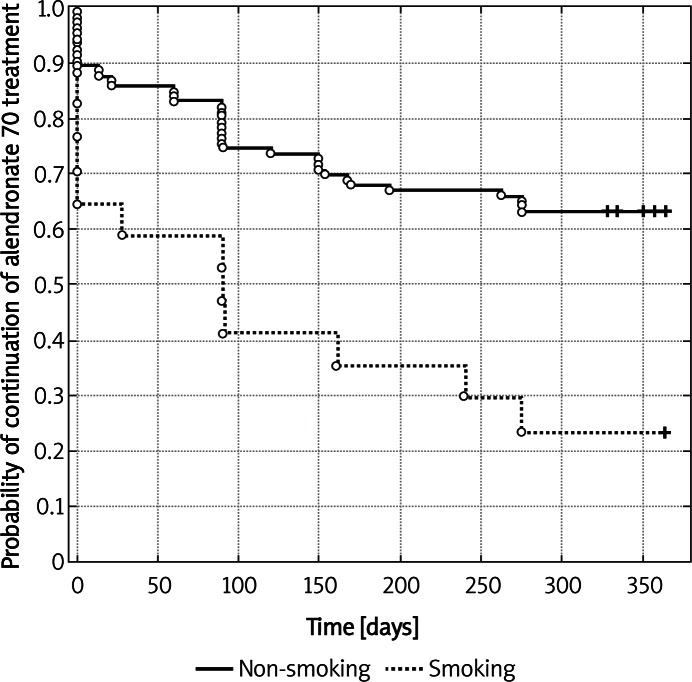

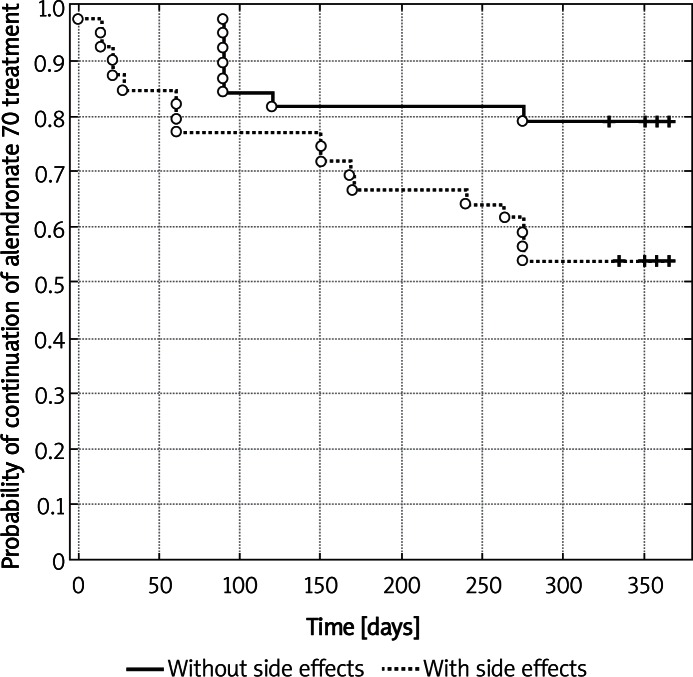

During the study period, the compliance rate to alendronate 70 therapy in the control group was 54.03% and the mean persistence period with the medication was 197 days. The time period to discontinuation longer than 30 days was 185.43 days (see Table II). The MPR above 80% after 1 year was observed in 37.5%, and 43.75% patients were persistent with their therapy. In the group of educated patients, both compliance and persistence were higher but not statistically significantly, compared to the control group (75.7% and 276.17 days, respectively and the time to discontinuation was 269.79 days). In that group of patients, MPR above 80% was observed in 65.52% and 68.97% of women were persistent with the therapy until the end of the study. Similarly, patients in the group with biochemical results revealed better outcomes compared to the control group (68.29%, 249.2 days, MPR > 80% – 64.52%, 64.52% of persistent patients). In the nurse assisted group, there were 2 additional phone calls after 3 and 9 months and the results were also better than in the control group (71.18%, 259.71 days, MPR > 80% – 61.29% and the percent of persistent women was 61.29%). Although the application of additional motivating factors did not bring any statistically significant differences among the groups, it seems that proper counselling, carried out by a doctor, and nurse assistance played a significant role. Regarding all the examined groups, age ≤ 65 years and > 65 years did not affect either compliance or persistence with therapy (Table III). Using the multivariate Cox proportional hazard model, the reasons for discontinuation of treatment, observed in the reported study, were adverse effects of the applied agent and smoking (Table IV; Figures 1 and 2). Table V shows the main reasons for therapy discontinuation in the examined groups.

Table II.

Compliance, persistence and time to therapy discontinuation in the examined groups: control group, counselling group, biochemical group, nurse assisted group

| Group | Compliance > 80% [%] | Percent of days during 1 year [%] | Persistence (number of days ± SEM) | Persistence (%) –% of patients staying 1 year in therapy [%] | Time to therapy discontinuation over 30 days (number of days ± SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 32) | 37.5 ±8.7 | 54.03 ±7.36 | 197 ±26.91 | 43.75 ±8.9 | 185.43 ±27.03 |

| Counselling (n = 29) | 65.52 ±9.0 | 75.71 ±7.00 | 269.72 ±26.95 | 68.97 ±8.7 | 269.79 ±26.25 |

| Biochemical (n = 31) | 64.51 ±8.7 | 68.29 ±7.95 | 249.19 ±29.04 | 64.51 ±8.7 | 249.19 ±29.04 |

| Nurse assistance (n = 31) | 61.29 ±9.0 | 71.18 ±6.87 | 259.71 ±25.10 | 61.29 ±6.82 | 259.71 ±25.10 |

Results presented as mean ± SEM

Table III.

Comparison of compliance and persistence in the group of older patients > 65 years of age and younger women ≤ 65 years of age

| Age [years] | Variables | N | Mean | SEM | Value of p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| > 65 | Percent of days during 1 year (% ± SEM) (compliance [%]) | 55 | 69.83 | 5.55 | NS |

| ≤ 65 | 68 | 64.82 | 4.95 | ||

| > 65 | Persistence (number of days ± SEM) | 55 | 254.87 | 20.26 | NS |

| ≤ 65 | 68 | 236.35 | 18.12 | ||

| > 65 | Time to discontinuation over 30 days | 55 | 248.14 | 20.68 | NS |

| ≤ 65 | 68 | 233.62 | 18.24 |

NS – not significant

Table IV.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazard model (95% confidence interval), predicting time to alendronate therapy discontinuation

| Parameter | Hazard ratio | Value of p |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.01 | NS |

| Number of drugs used daily | 0.99 | NS |

| Monthly income | 0.92 | NS |

| Physical activity | 0.98 | NS |

| Education | 1.10 | NS |

| Place of living | 0.98 | NS |

| Number of persons in family | 1.02 | NS |

| Spine fracture | 0.99 | NS |

| Forearm fracture | 0.81 | NS |

| Other fracture | 1.34 | NS |

| Fracture in family | 1.28 | NS |

| BMI | 1.04 | NS |

| Fracture during treatment | 1.73 | NS |

| Smoking | 2.84 | < 0.01** |

| Side effects | 1.97 | < 0.05* |

NS – not significant,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier's probability of alendronate 70 treatment continuation in the group of patients smoking and non-smoking (p = 0.0018 – log-rank test)

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier's probability of alendronate 70 treatment continuation in the group of patients with and without side effects (p = 0.0174 – log-rank test)

Table V.

Reasons for therapy discontinuation in the examined groups

| Reasons for therapy discontinuation | Control (n = 32) [%] | Counselling (n = 29) [%] | Biochemical tests (n = 31) [%] | Nurse assistance (n = 31) [%] | In all groups together (n/%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of extension and loss of contact | 9.4 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 3.2 | 8/11.6 |

| Side effects | 18.8 | 10.3 | 16.1 | 14/20.3 | |

| Hospitalizations | 6.3 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 4/5.8 | |

| Not to receive treatment at all | 15.6 | 19.4 | 6.5 | 13/18.8 | |

| Failure to prolong the drugs | 9.4 | 10.3 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 10/14.5 |

| Change to another bisphosphonate | 9.4 | 6.9 | 19.4 | 9.7 | 14/20.3 |

| Other diseases | 3.1 | 3.4 | 2/2.9 | ||

| Change to another therapy | 3.2 | 3.2 | 2/2.9 | ||

| Loss of interest | 6.5 | 2/2.9 |

Facilitation of patient contacts with physician, continuous access to prescribed medication and frequent visits considerably improve patients’ adherence to prescribed recommendations.

Discussion

Osteoporosis is a chronic disease, demanding long-term clinical observations and strict adherence to medication regimens. Uncontrolled therapy discontinuation is associated with increased fracture risk, decrease of bone mineral density and increased costs of treatment and care. Currently, some emphasis is placed on finding additional ways to improve compliance to prescribed therapy.

Most of the hitherto presented results concerns the analysis of retrospective studies. It has been shown that the persistence with weekly bisphosphonate treatment ranges between 35% and 45% [14].

As suggested [24], retrospective studies have led to a better understanding of the factors affecting medication adherence and their association with improved treatment outcomes. However, these data do not provide any information about patient choices and preferences which can also affect their compliance and persistence behaviours. While recent evidence suggests the importance of dosing regimen and of the route of administration, other data show that the efficacy and safety of treatment remain the most important determinants. Detailed information on treatment options, side effects and outcomes may have a beneficial impact on medication-taking behaviour. Counselling provided by healthcare professionals (physicians or nurses), as well as subsequent therapy monitoring, may play a crucial role in the management of factors responsible for poor adherence with osteoporosis therapies.

Following our previous studies, non-drug factors were included in the present, prospective observation to analyse whether they were able to improve patient adherence to alendronate 70 therapy. The goal of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of introduced counselling, nurse assistance and presentation of biochemical parameters to treated patients for their adherence to alendronate 70 treatment.

In our previous study, the compliance to daily alendronate therapy was assessed for 6 or 18 months in clinical practice of postmenopausal osteoporosis [11]. Based on a retrospective study of medical records at our Outpatient Clinic, as well as of data from telephone interviews with patients, the overall compliance rate of postmenopausal patients with the daily alendronate regimen was assessed. After 1.5 years of observation, 20.4% of the patients and, after 0.5 year, 8.5% of the patients discontinued their treatment due to intolerance (especially gastrointestinal side effects) (47.8%), health problems unrelated to osteoporosis (8.7%), inconvenience with the daily regimen (13.1%), the costs of therapy (4.3%) and clinical improvement below expectations (26.1%). It is worth mentioning that in both observation periods (1.5 and 0.5 year), almost the same percentage of patients withdrew from their consultations at our Outpatient Clinic (15.6% and 14.4%, respectively). Telephone interviews with the patients who ceased attending the Outpatient Clinic at the Regional Centre of Menopause and Osteoporosis revealed that more than 50% of them discontinued the treatment.

In our previous prospective study, we analysed the adherence to alendronate 70 therapy of 153 post-menopausal women, followed up for 1 year with monitoring frequency of every 2 months [12]. Unexpectedly, the adherence to therapy of all the study participants was high during the entire study period, the patients remaining compliant after a year in 95.08 ±1.39% of cases, and the mean persistence with medication was 347.05 ±5.07 days. In the group of patients who interrupted treatment, the mean persistence was 212.44 days. One of the study participants did not start the treatment, and two others discontinued the therapy within 30-60 days from the study onset. Facilitated contacts with the doctor, continuous access to prescribed treatment and frequent visits significantly improved patient compliance. The common reasons for discontinuation were side effects of the administered therapy, while age, but not education, affected the rate of compliance with therapy.

In the reported 1-year observation study, the compliance to alendronate 70 therapy in the control group was 54.03% and the mean persistence with medication was 197 days. The MPR above 80% was observed in 37.5% and, after 1 year, 43.75% of patients were persistent. This is in agreement with those reports where persistence scores are far from optimistic. For example, medication persistence was demonstrated in only 39.0% of the patients receiving daily alendronate therapy at month 12 of the study period [25]. In a questionnaire study of women with osteoporosis on daily risedronate, one in four failed to comply correctly with dosing instructions, despite counselling [26]. Using a telephone interview survey in a subsequent study, it was reported that, within 13 months of observation, 56% of the women with osteoporosis were non-compliant with daily alendronate [27].

In the group of patients who were counselled during each consultation, both compliance and persistence were higher, but not statistically significantly (75.7% and 276.17 days, respectively), compared to the control group (54.03% and 193.88 days). In the counselled group, MPR above 80% was observed in 65.52% and 68.97% persisted with the therapy until the end of the study, while those parameters were also higher compared to those in the control group (MPR > 80% was 37.5%, and persistence 43.75%). It has been shown by other authors [28] that special education programmes increased the knowledge of treated patients about osteoporosis and their adherence to pharmacological therapy was significantly higher in the counselled group (92%) compared to the control group (80%) after 2 years of observation. On the other hand, that educational intervention did not significantly improve medication compliance or persistence with osteoporosis drugs in post hoc analysis of randomized control trials after 10 months of observation, even if the number of patients was higher [29].

Similarly, patients in the group with presentation of biochemical results were statistically non-significantly better in their persistence with therapy compared to the control group (the biochemical group: 68.29%, 249.2 days, MPR > 80% – 64.52%, the percent of persistent patients 64.52%). In the nurse assisted group, where 2 additional phone calls were made after 3 and 9 months, the results were not statistically significantly better than in the control group (the nurse assisted group: 71.18%, 259.71 days, MPR > 80% – 61.29% and the percent of persistent women was 61.29%).

Data from our previous retrospective study showed that, after 18 months of observation, 79.6% of patients and, after 6 months, 91.5% of patients continued their treatment [11]. It is worth mentioning that in both observation periods, almost the same percentage of patients stopped attending our Outpatient Clinic (15.6% and 14.4%, respectively). Telephone interviews with those patients revealed that more than 50% discontinued treatment. In our previous analysis, the main reasons for discontinuation of weekly alendronate treatment included side effects, especially from the gastrointestinal tract (61.10%), infections (16.67%), fractures (5.56%), 1 person did not even start therapy (5.56%) and other causes (11.11%), being similar to the results of other authors [23, 30].

Among the patients completing one of the studies, the percentages of high compliance patients were: 80% (raloxifene), 79% (daily alendronate), 65% (weekly alendronate) and 76% (risedronate). Discontinuation due to side effects was the highest for weekly alendronate (7.0%), followed by daily alendronate (6.4%), raloxifene (3.8%) and risedronate (3.4%). The discontinuation rate was higher for patients with a history of surgical menopause, advanced age and a lack of knowledge about medical prevention of osteoporosis [31].

Unexpectedly, in our previous prospective study, in which patients were monitored every 2 months, the compliance with alendronate 70 therapy was very high [12]. An analysis of 7 visits during 1 year demonstrated patient compliance in 95.08% of cases, while the mean persistence with medication was 347.05 days. In the group of patients who interrupted treatment, the mean persistence period was 212.44 days. The main reasons for therapy discontinuation included side effects, infections and hospitalizations.

The results of the above-mentioned paper were compared to the prospective work of a Canadian group [32]. The Canadian Database of Osteoporosis and Osteopenia (CANDOO), an observational database, designed to capture clinical data, was searched for patients who started therapy with etidronate or alendronate for women and men and hormone replacement therapy for women. After 1 year, 90.3% of those patients were still taking etidronate, compared with 77.6% on daily alendronate and 80.1% of patients on HRT, which decreased to 44.5% after 6 years. Reginster and Lecart [33] suggest that the persistence rates in the CANDOO study were high because the study took place in a hospital environment, where the patients initially signed consent and were verbally encouraged to continue treatment. Our observations, published in 2011 [12], were similar to the prospective CANDOO study but additional monitoring every 2 months might improve the results.

Good adherence to osteoporosis treatment is very important for the effectiveness of administered medications. Among almost 1000 respondents – patients with osteoporosis – the effectiveness was ranked as the most important determinant of preference (79%), compared with the time on the market (14%), dosing procedure (4%) and dosing frequency (3%). The incorporation of patient preferences into the medication decision-making process could enhance patient compliance and clinical outcomes [34]. This latter opinion is very important, as it has been shown that compliance rates below 66% in drug treatment result in sub-optimal improvement in bone density [23]. On the other hand, better compliance in actual practice may significantly decrease osteoporosis-related fracture risks (16% during 2 years) [35]. It has been observed that anti-fracture effectiveness, associated with high adherence to oral bisphosphonates, varied substantially by age and fracture type [36]. Caro et al. [37] found that poorly compliant patients were significantly more often hospitalized (53.4%) compared to compliant ones (42.6%), leading to a 14% increase in medical service costs.

Claxton et al. [38] suggest that the prescribed number of doses per day is inversely related to compliance. In other words, less frequent dosing regimens resulted in better compliance across a variety of therapeutic classes. This is reflected in osteoporosis therapy. Postmenopausal women prescribed a weekly regimen of bisphosphonates demonstrated significantly higher compliance rates than daily regimen patients, and they also persisted longer with prescribed treatment. However, compliance and persistence rates were suboptimal for both regimens [21, 39].

Osteoporosis is a chronic disease which needs long-term clinical monitoring and strict adherence to therapeutic recommendations. Analysing our observations and the results of others, we suggest that the main reasons for discontinuation of treatment are not only digestive incidents but also problems with obtaining prescriptions within the first 3 months of treatment, dissatisfaction with therapy results and poor monitoring. In our opinion, effective communication with patients, together with properly oriented counselling, additional nurse assistance and more frequent contacts with doctors, as well as presentation of results of additional biochemical tests, may greatly improve the adherence to osteoporosis treatment modalities. Determining the levels of additional, especially new bone metabolism markers, e.g. osteoprotegerin and RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear κB ligand), may contribute to improved compliance and persistence in the patients. However, there are no conclusive data on the relationship of these compounds with the effectiveness of different forms of therapy [40, 41] or fragility fractures [42].

Our study shows that monitoring, even by phone, is very helpful both for compliance and persistence scores. Variation in adherence to medical treatment of osteoporosis may also depend on other factors – individual patient's convictions, patient's social and economic background, physical predispositions or health problems, age, as observed by others or smoking – which is presented in our study. Compliance could be improved by patient's preference of treatment regimen. It is of utmost importance to inform patients about diagnostic results and the long-term treatment plan, highlighting the role of persistence with therapy and compliance with dosing recommendations [43]. Adherence to drug administration regimens in the therapy of osteoporosis improves BMD, and reduces femoral neck and spine fracture risks, while also decreasing the costs of inpatient therapy. Some data suggest that psychobehavioural interventions may help improve patient motivation [8]. An interesting research option seems to be teriparatide because of the proven strong anabolic effect, high anti-fracture efficacy [44], and higher quality of life vs. alendronate in other studies [45]. However, the high drug price can significantly reduce compliance.

In conclusion, good adherence to medical recommendations by patients treated for osteoporosis with alendronate 70 depends on the degree of attention provided to treated patients by treatment providers, including the frequency of monitoring visits and enquiry contacts, counselling of patients and biochemical parameter assays with treated patients being informed of the results. The critical aspects for treatment discontinuation include therapy-induced adverse effects and smoking.

Acknowledgments

The study was sponsored by the Scientific Polpharma Foundation (Medical University Grant No. 501-91-269).

References

- 1.Jaworski M, Lorenc RS. Risk of hip fracture in Poland. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13:CR206–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cranney A, Guyatt G, Griffith L, Wells G, Tugwell P, Rosen C. Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. IX: Summary of meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:570–8. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-9002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cranney A, Tugwell P, Zytaruk N, et al. Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. IV. Meta-analysis of raloxifene for the prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:524–8. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cranney A, Wells G, Willan A, et al. Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. II. Meta-analysis of alendronate for the treatment of postmenopausal women. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:508–16. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cranney A, Papaioannou A, Zytaruk N, et al. Parathyroid hormone for the treatment of osteoporosis: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2006;175:52–9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papadimitropoulos E, Wells G, Shea B, et al. Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. VIII: Meta-analysis of the efficacy of vitamin D treatment in preventing osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:560–9. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-8002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shea B, Wells G, Cranney A, et al. Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. VII. Meta-analysis of calcium supplementation for the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:552–9. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-7002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman SL, Schousboe JT, Gold DT. Oral bisphosphonate compliance and persistence: a matter of choice? Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:21–7. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1274-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gold DT. Medication adherence: a challenge for patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis and other chronic illnesses. J Manag Care Pharm. 2006;12(6 Suppl A):S20–5. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2006.12.S6-A.S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold DT, Martin BC, Frytak JR, Amonkar MM, Cosman F. A claims database analysis of persistence with alendronate therapy and fracture risk in post-menopausal women with osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:585–94. doi: 10.1185/030079906X167615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sewerynek E, Dabrowska K, Skowronska-Jozwiak E, Zygmunt A, Lewinski A. Compliance with alendronate 10 treatment in elderly women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endokrynol Pol. 2009;60:76–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sewerynek E, Malkowski B, Karzewnik E, et al. Alendronate 70 therapy in elderly women with post-menopausal osteoporosis: the problem of compliance. Endokrynol Pol. 2011;62:24–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold DT, Safi W, Trinh H. Patient preference and adherence: comparative US studies between two bisphosphonates, weekly risedronate and monthly ibandronate. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:2383–91. doi: 10.1185/030079906X154042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM. A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1023–31. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sewerynek E. Wpływ współpracy lekarza z pacjentem na efektywność leczenia osteoporozy. Terapia. 2006;3:43–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sewerynek E. Czynniki wpływąjace na przestrzeganie zasad terapii i efektywność leczenia osteoporozy - rola współpracy lekarza z pacjentem. Medycyna po Dyplomie. 2008;3(Suppl):39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lombas C. Compliance with alendronate treatment in an osteoporosis clinic. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;15:S529–M406. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandeira F, Kayath M, Marques-Neto J, et al. Patients’ clinical features and compliance associated with raloxifene or alendronate after a six-month observational Brazilian Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(Suppl. 2):352–79. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Negri AL. Short-term compliance with alendronate 70 mg in patients with osteoporosis: the ECMO Trial. Bone. 2003;23(Suppl):P487. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bocuzzi SJ, Foltz SH, Omar MA, Kahler KH, Gutierrez B. Adherence and persistence associated with pharmacological treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis Int. 2005;16(Suppl 3):S24. Abstract P129. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cramer JA, Lynch NO, Gaudin AF, Walker M, Cowell W. The effect of dosing frequency on compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy in postmenopausal women: a comparison of studies in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1686–94. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solomon DH, Avorn J, Katz JN, et al. Compliance with osteoporosis medications. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2414–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.20.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yood RA, Emani S, Reed JI, Lewis BE, Charpentier M, Lydick E. Compliance with pharmacologic therapy for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:965–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gold DT. Understanding patient compliance and persistence with osteoporosis therapy. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:249–55. doi: 10.2165/11586880-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ettinger MP, Gallagher R, MacCosbe PE. Medication persistence with weekly versus daily doses of orally administered bisphosphonates. Endocr Pract. 2006;12:522–8. doi: 10.4158/EP.12.5.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamilton B, McCoy K, Taggart H. Tolerability and compliance with risedronate in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:259–62. doi: 10.1007/s00198-002-1370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ettinger B, Pressman A, Schein J, Chan J, Silver P, Connolly N. Alendronate use among 812 women: prevalence of gastrointestinal complaints, non-compliance with patients instructions and discontinuation. J Managed Care Pharm. 1998;4:488–92. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen D, Ryg J, Nielsen W, Knold B, Nissen N, Brixen K. Patient education in groups increases knowledge of osteoporosis and adherence to treatment: a two-year randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shu AD, Stedman MR, Polinski JM, et al. Adherence to osteoporosis medications after patient and physician brief education: post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:417–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Napiórkowska L, Franek E. Systematyczność i wytrwałość w zażywaniu leków w trakcie wieloletniego leczenia osteoporozy. Twój Magazyn Medyczny. 2006;2:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ringe JD, Christodoulakos GE, Mellstrom D, et al. Patient compliance with alendronate, risedronate and raloxifene for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2677–87. doi: 10.1185/03007x226357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papaioannou A, Ioannidis G, Adachi JD, et al. Adherence to bisphosphonates and hormone replacement therapy in a tertiary care setting of patients in the CANDOO database. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:808–13. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1431-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reginster JY, Lecart MP. Treatment of osteoporosis with bisphosphonates: do compliance and persistence matter? Business Briefing. Long-term Healthcare. 2004:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss TW, McHorney CA. Osteoporosis medication profile preference: results from the PREFER-US study. Health Expect. 2007;10:211–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caro JJ, Ishak KJ, Huybrechts KF, Raggio G, Naujoks C. The impact of compliance with osteoporosis therapy on fracture rates in actual practice. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:1003–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1652-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Cheng H, Lyles K, Saag KG, Delzell E. Benefit of adherence with bisphosphonates depends on age and fracture type: results from an analysis of 101,038 new bisphosphonate users. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1435–41. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caro JJ, Ishak KJ, Krista F, et al. Clinical and economic impact of adherence to osteoporosis medication. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(Suppl 7) Abstract PL6. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1296–310. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cramer JA, Amonkar MM, Hebborn A, Altman R. Compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate dosing regimens among women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1453–60. doi: 10.1185/030079905X61875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi HJ, Im JA, Kim SH. Changes in bone markers after once-weekly low-dose alendronate in postmenopausal women with moderate bone loss. Maturitas. 2008;20:170–6. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dobnig H, Hofbauer LC, Viereck V, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Fahrleitner-Pammer A. Changes in the RANK ligand/ osteoprotegerin system are correlated to changes in bone mineral density in bisphosphonate-treated osteoporotic patients. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:693–703. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sypniewska G, Sobanska I, Pater A, Kedziora-Kornatowska K, Nowacki W. Does serum osteoprotegerin level relate to fragility fracture in elderly women with low vitamin D status? Med Sci Monit. 2010;16:CR96–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emkey RD, Ettinger M. Improving compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy for osteoporosis. Am J Med. 2006;119(4 Suppl 1):S18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vestergaard P, Jorgensen NR, Mosekilde L, Schwarz P. Effects of parathyroid hormone alone or in combination with antiresorptive therapy on bone mineral density and fracture risk; a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:45–57. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panico A, Lupoli GA, Marciello F, et al. Teriparatide vs. alendronate as a treatment for osteoporosis: changes in biochemical markers of bone turnover, BMD and quality of life. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17:CR442–8. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]