Abstract

During the last decade, the field of human genome research has gone through a phase of rapid discovery that has provided scientists and physicians with a wide variety of research tools that are applicable to important medical issues. We describe a case of familial Huntington disease (HD), where the proband at risk preferred not to know his disease status but wanted to know the status in his unborn child. Once we found the father to be negative, the case raised an important ethical question regarding the management of this as well as future pregnancies. This paper discusses the arguments for and against the right not to know of one’s carrier status, as well as professional obligations in the context of withholding unwanted information that may have direct implications not only for the patient himself but also for other family members. HD has been the gold standard for many other adult onset genetic diseases in terms of carrier testing guidelines. Hence, we feel it is time to revisit the issue of prenatal testing for HD and consider updating the current recommendations regarding the patient’s right to “genetic ignorance”, the right not to know genetic information.

Keywords: Huntington Disease, prenatal testing, guidelines, ethics

The past decade has lead to incredible advances in the field of human genome research. Continued improvements in technology, along with the decreasing costs of gene sequencing have provided scientists and physicians with a wide variety of research tools that are directly applicable to important medical issues, and it is likely that the continued advances will soon result in the clinical application of these technologies. It is expected that microarray-based targeted sequencing will soon be employed in clinics to predict the risk of disease in an individual and his offspring, or to select drugs and other therapies that would best treat the individual’s condition. While the majority of individuals and their healthcare providers are likely to find that such large-scale testing is informative, others might be faced with distressing or unwanted information.

For many conditions, choosing not to know a medical diagnosis or information about genetic susceptibility to disease only has implications for the individual being tested; however, for some diseases and in certain situations this choice may interfere with appropriate medical management and could present a risk to other family members or future offspring. While communicating an individual’s ‘unwanted’ results would violate the autonomy of the individual being tested, not communicating the results could compromise patient care, place others at risk for significant harm, and potentially create conflicts for physicians that challenge their professional integrity. Healthcare providers should have some latitude in doing what they think is best, but should not be left to wander in the wilderness when faced with such ethical vexations. Therefore, it is important for professional societies to develop guidelines to assist physicians and genetic counselors in responsibly balancing an individual’s desire for genetic ignorance with the interests of family members and the professional obligations of health care providers.

To illustrate various aspects of such conundrums, we present a case of Huntington disease (HD), where the proband does not wish to know his own disease status but wants to know the status of his fetus. Testing indicated that neither the father nor his fetus were at risk for HD. This case raised important ethical questions regarding the appropriate management of future pregnancies. HD has been the gold-standard for ethical consideration of presymptomatic testing for genetic diseases in terms of testing guidelines. We feel it is time to consider revisiting the issue of prenatal testing for HD and update the existing recommendations. Beginning with this specific problem will allow professional societies to develop models for dealing with unwanted information as we enter the era of large-scale clinical sequencing.

Hypothetical Case scenario

To avoid violation of patient’s privacy, we present a hypothetical case scenario based upon our interactions with multiple patients.

A 34-year-old woman came to our prenatal clinic for genetic counseling. She was in her 12th week of gestation and had recently found out that her husband’s father has HD. After receiving genetic counseling, she and her husband sought to have prenatal testing on the fetus. The diagnostic laboratory performing the prenatal testing requires concomitant testing on both parents. This is done to provide the most accurate result as quickly as possible (in cases where the fetus’ alleles appear to be the same size, parental results are important in the interpretation as they may exclude a large deletion, failure of allele amplification and uniparental disomy). Results from the husband revealed that he was not at risk of developing HD and, as expected, the fetus was also found not to be at risk of developing HD. Three years later the couple returned for prenatal consultation, seeking pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (including in vitro fertilization) for future pregnancies. The couple still did not want to know the husband’s HD test result.

The case described raises the important ethical question: Is there a right to genetic ignorance (right not to know) in the context of prenatal testing for HD when it puts others at risk from unnecessary medical procedures?

Background

The disease

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant, adult-onset, neurodegenerative disease for which there is no cure. Clinical features include an involuntary movement disorder, cognitive decline, personality changes and psychiatric disease. The mean age of onset is 40 years, after which symptoms progress slowly with death occurring around 15 years after the onset of the disease.

In March 1993 the Huntington-gene, located on chromosome 4p16.3, was isolated and found to contain an expanded and unstable trinucleotide repeat (CAG) in individuals with HD. The identification of the gene resulted in the ability to perform a predictive DNA-test in asymptomatic persons with family history of HD 1,2.

Available testing

Pre-symptomatic predictive testing and prenatal testing is performed by direct mutation analysis or by linkage analysis. Direct mutation analysis is precise but requires concomitant testing of the affected or at-risk parents to ensure accurate interpretation of the results. Linkage analysis using samples from the fetus and an affected relative, other than the at-risk parent, is possible. If the fetus has not inherited either of the chromosome 4 homologs seen in the affected relative, then the parent’s status need not be disclosed; however, if the fetus carries one of the chromosome 4s from the affected relative, the fetus may or may not actually be affected and the parent will not know whether he or she is affected. Linkage cannot determine which homolog in the affected relative harbors the mutation. Therefore, if one were to use linkage analysis from a single affected individual to decide about termination of a pregnancy, then half of those terminated fetuses would be unaffected. Linkage analysis is no longer available in United States, according to Genetests; a laboratory Sweden is currently the only reported lab performing linkage analysis for HD (Genetests- Feb- 2009).

Desire for predictive testing

Given the technical feasibility of predictive testing in HD, and the severity of the disorder, it might be expected that predictive diagnosis would be frequently requested. However, only 3–21% of the at-risk population have received predictive testing in Sweden, Canada, England, and the United States, with the highest percentage of testing being performed in the U.S. 3. Non-participants have expressed anxiety about negative consequences of genetic testing, such as depression, fear of HD, inability to cope with results, and fear of discrimination 3. Depression is typical in HD and suicide is estimated to be about five to ten times higher than that of the general population (about 5–10%). Although no significant difference in neuropsychological functioning was found between mutation positive and mutation negative asymptomatic carriers prior to testing 4, after receiving results, those who tested positive had increased risk of major depressive disorders compared to both the general population and to those who tested negative 5. Supporting studies suggest that the incidence of suicide is highest in the prediagnostic phase, decreases for those who have recently been diagnosed, and increases again in later stages of the illness when independence diminishes 2,6. These studies emphasize the significant fear of test results experienced by the HD population and yet the benefit effect of a negative result on ones’ quality of life.

The current guidelines

In 1994, guidelines for predictive testing in HD were published in the Journal of Medical Genetics 7. The recommendations were drawn up by a committee consisting of representatives of both the International Huntington Association and the World Federation of Neurology research group on HD involuntary movements. The first recommendations were adopted by both organizations at their respective meetings in Vancouver in 1989 and were published in the Journal of Neurological Sciences the same year and in the Journal of Medical Genetics in 1990. These Guidelines were revised in 1994 to incorporate the recent discovery and availability of trinucelotide repeat testing. The current guidelines recommend prenatal testing only if both parents agree to the test, the parents intend to terminate the pregnancy if the fetus is a carrier of the gene defect, and the at-risk parent has been tested. The guidelines do recognize the right of genetic ignorance and allow for exclusion testing to preserve that right, but also point out that this may result in the termination of pregnancies with a 50% at-risk fetus. (Text box 1). Although PGD was available at the time the guidelines were written, it was not yet used for HD clinically (1998). Thus, no recommendations were made regarding PGD for HD.

Text Box 1. Specific Recommendations from Professional Organization- 1994 Summary.

-

It is essential that prenatal testing for the HD mutation should only be performed if the parent has already been tested. For a possible exception see exclusion testing.

It is highly desirable that both parents should agree to a prenatal test.

-

The couple requesting prenatal testing must be clearly informed that if they intend to complete the pregnancy if the fetus is a carrier of the gene defect, there is no valid reason for performing the test.

Testing a fetus carries with it a small additional risk of miscarriage and, possibly, of congenital abnormality.

-

Test centers may still perform an exclusion test for a future pregnancy if a 50% at-risk person specifically requests it. For this test the person at risk, partner, parents, and fetus are tested only with adjoining DNA probes.

The purpose of the exclusion test, which was frequently performed before the gene defect itself had been found, was to permit a 50% at-risk person to exclude the possibility of affected children without changing his/her 50% at-risk status. This does include the termination of pregnancies of a 50% at-risk fetus and continuation of pregnancies of a low-risk fetus only 7.

PGD for HD

For at-risk persons who may not want to know their genetic status and wish to create a family without gamete donation or adoption, two different options are available; exclusion tests performed either prenatally or as part of PGD, and non-disclosure PGD 8. The major difference between the two methods is that with exclusion testing performed prenatally there is a risk of aborting a normal fetus, while with PGD only healthy embryos are transferred. Abortion by itself has unpleasant sequellae and can be emotionally difficult for patients. For some asymptomatic HD carriers who find out at older age that they are negative, it can be devastating to realize that they have aborted an unaffected child9. In addition, proceeding with PGD is a desired option when termination conflicts with religious beliefs or if the couple has to go through IVF because of infertility issues8. Disadvantages of PGD include low success rate, especially with a dominant disease reducing the potential number of healthy embryos by half, the high cost, and the safety of the mother who has to go through IVF. Also, as with any lab procedure, there is the risk of misdiagnosis.

As with predictive testing for HD, there is low utilization of PGD for HD. The very act of testing for HD, whether prenatally or through PGD, can be controversial because HD is a late-onset disorder. Is it ever justified to abort a fetus that could have 3–4 decades of life before becoming ill? On the other hand, should carrier parents have the right to have children when the disease is inevitable and eventually results in a significant loss of competence? In the UK, it is a legal requirement to take into account the welfare of any child born as a result of assisted conception before offering treatment 8.

Performing a nondisclosure PGD, meaning without revealing the result to the parents, raises additional concerns9. Besides the difficulties of keeping the test result a secret, especially in large centers, the physician may be forced to engage in deception, thereby violating her professional integrity. For example, if all embryos are affected, the doctor may be compelled to conduct a mock embryo transfer in order to maintain the deception8. This not only undermines the professional virtues of honesty and fidelity, it constitutes fraud in the performance of a “sham” procedure.

Ethical considerations

The right not to know

Respect for autonomy is a core ethical principle in medicine. It establishes a right to relevant medical information, but it does not create an obligation to be informed. The “right not to know” diagnostic or risk assessment information is firmly established in medicine, medical ethics, and especially in genetics 10. It is only restricted in limited circumstances (e.g., in some jurisdictions individuals can be criminally prosecuted for HIV transmission if they know they are at-risk, refuse to be tested, and engage in risky behavior 11). In the context of prenatal genetic testing for autosomal dominant diseases like HD, the right not to know is naturally limited by the fact that a positive result for the fetus means that the at-risk parent is positive as well.

The parents should be informed of this limitation prior to testing and should be prepared to receive a positive test result. Only if the fetus is negative will the at-risk parent be able to assert his or her right to genetic ignorance. If the parent’s test result is negative, as it was in the case described above, then prenatal testing and/or PGD for future pregnancies is not medically indicated and could result in potential harm to the spouse (mother) and/or fetus.

Withholding a negative test result from the parent respects his autonomy and allows him to decide what information he would like to have regarding his future health status. At the same time, it limits the ability of the individual to make informed decisions about prenatal testing and/or PGD for future pregnancies. Some worry that disclosure of unwanted information will cause psychosocial harm to the individual. However, given that the incidence of suicide in this population is highest prior to diagnostic testing, disclosure may actually reduce the risk of harm to the individual.

Since the patient in this case is negative for HD, one may assume that he would be thrilled to have this information so it might as well be provided. However, if a testing center only informs those who are negative then they are by omission also informing those who are positive. International access to the internet has created new ways for patients to connect with one another and share information about testing centers, physicians, new treatments, etc. The HD community is very tightly connected and it is likely that news of a testing center’s practice of informing those who are negative of their test result will spread fast. If this is adopted as policy, then the right not to know will be violated de facto.

Professional Obligations

Health care professionals have a fiduciary obligation to protect and promote the health-related interests of their patients. The concept of a physician as fiduciary dates back to the eighteenth century 12 and is the basis of contemporary notions of professionalism in medicine 13. As fiduciaries, physicians and other health care professionals are expected to be competent, to use their competence or expertise primarily for the benefit of their patients, and to promote medicine as a public trust 12.

A clinical and ethical team in Australia recently reported a hypothetical case where the father was at risk for HD and did not want to know his genetic status while his pregnant wife wanted to proceed with prenatal testing, clarifying that she intended to abort the fetus if found to be HD positive14. There, the ethical discussion related to the right of the pregnant mother to receive prenatal testing versus the right of the father to maintain his genetic ignorance. Under Australian law, decisions about prenatal testing can be made solely by the mother; paternal consent, or even knowledge, is not required. The law is concerned only with the bodily integrity of the mother, on whom the test is performed. While the legal team felt the adverse effect of genetic information on other family members is not a good reason to withhold information that might benefit the patient, the clinical team felt they should make every effort to obtain informed consent from the male partner and if he refused, they should not proceed with the testing. The main recommendation of this paper was that the law in the UK and Australia regarding prenatal diagnosis may need to be reconsidered and clarified.

In the US, the pregnant woman is traditionally considered the only patient; however, in the past several years we have seen a shift toward a more family-centered approach, where physicians and other health care providers consider not only the pregnant woman, but also her partner, and to some extent the unborn child, to be patients to whom they owe fiduciary obligations 15. The couple is encouraged to make joint decisions about prenatal testing and possible termination of the pregnancy. If a physician knows that a particular procedure (including invasive diagnostic testing) that carries some risk to the patient is not medically indicated (i.e., it carries no prospect of medical benefit), then it would arguably be a violation of professional integrity to perform that procedure. In the case described above, there is arguably only minimal prospect of psychological benefit by performing a prenatal test or by providing IVF with PGD for future pregnancies. That benefit is uncertain, and it, together with the appeal to respect for the patient’s autonomy, must be balanced against the prospect of harm to the mother and/or fetus and the potential violation of professional integrity if the test or procedure is performed.

Practical considerations for prenatal testing in HD disease

Genetic tests are often used differently for different disorders making the process of ordering and interpreting them not trivial. They differ in their detection rate, methodology, specificity and sensitivity and may be used differently in different situations 16. Prenatal genetic tests are even more complex to perform and interpret and carry additional risk to the fetus. Thus, the following are issues to consider before ordering prenatal genetic tests in general and in HD specifically:

Was the diagnosis of HD in the family member confirmed? In order to reduce the risk of performing an unnecessary test on the parent and the fetus, it is crucial to confirm the diagnosis of HD in the family. Most genetic tests are most informative if a clinically affected member is tested first before using the test to predict genetic status for a clinically unaffected family member. Unfortunately, in the U.S., our fragmented health care system often prevents testing the proband due to financial and logistical concerns. This is particularly true in time-sensitive situations, such as testing of a pregnancy.

Which test to order? There are multiple methodologies for diagnosing a specific condition. When one considers prenatal testing, the procedure and type of cells have implications on the result’s interpretations.

How to interpret the results? In HD there is the category of intermediate alleles that have the potential to expand into the disease range within one generation 17.

How to deliver the results? According to the guidelines set up by the international Huntington Association counseling of the highest standards should be available in each country and provided by a specialized genetic counseling unit 7. The key professionals in the counseling process are a geneticist, a psychologist, a neurologist and a genetic counselor. In some countries a nurse specializes in genetic counseling while in the U. S. genetic counselors are trained in Master degree programs accredited by the American Board of Genetic Counseling 3.

In summary, as a general policy it is not feasible to reveal unwanted genetic test results only to those patients who test negative because it is likely that this policy will become well-known and those who are not informed of their result will gather that they are positive. Further, as fiduciaries, physicians are obligated to use their expertise for the benefit of the patient and should refrain from performing unnecessary procedures that have no prospect of benefit and may result in harm to the patient and/or his family. We are aware of the danger for increased abortions as a consequence since the majority of the HD pre-tested population fear diagnosis tremendously and do not want to know their disease status. Taking all this into account, there is a true need to update recommended guidelines by a joint committee of geneticists, neurologists, and legal and ethical experts.

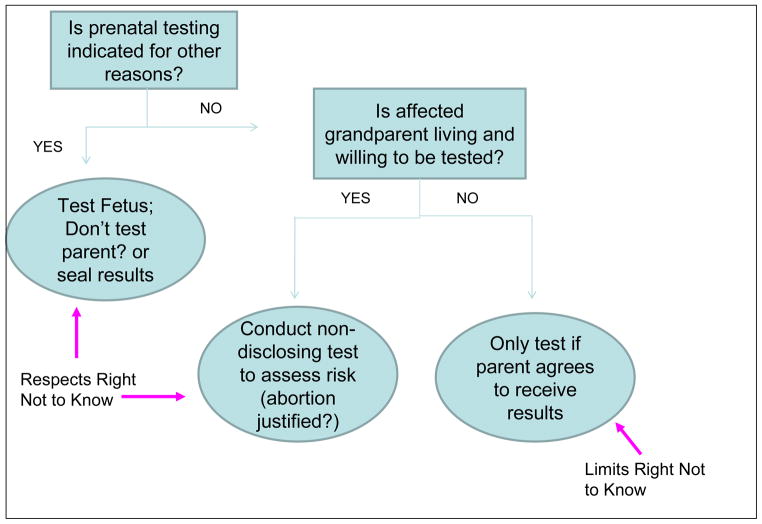

Scheme 1.

Ethical Considerations in Decision Making Flow diagram for prenatal HD Diagnosis

Text Box 2. Recommended Management Strategy.

-

Pre-test counseling

Emphasize limitations on the ability of a parent not to know in cases where fetus has the mutation

Explain risks and benefits of testing fetus & at risk parent

-

Elicit reasons for not wanting to know

Correct false assumptions/misinformation

Respectful persuasion with offer of psychological counseling

Explain and justify limits of right not to know

Obtain informed consent to test fetus (and parent if appropriate) and to inform of results (if appropriate)

Provide post-test counseling and support

-

Second pregnancy:

If you know the parent is negative and neither prenatal testing nor IVF/PGD are indicated for other reasons, refrain from unnecessary medical procedures, such as PGD

Unnecessary procedure with increased risk = medically inappropriate and violation of professional integrity

Pragmatic problem: only telling those who are negative = implicitly telling everyone

Acknowledgments

A.E. is supported by the NUCDF foundation and Children’s National Medical Center; A. M. is supported by the Greenwall Foundation Faculty Scholars Program in Bioethics and NIH/NHGRI R01 HG004333.

References

- 1.Greenamyre JT. Huntington’s disease--making connections. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):518–520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr067022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker FO. Huntington’s disease. Lancet. 2007;369(9557):218–228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robins Wahlin TB. To know or not to know: a review of behaviour and suicidal ideation in preclinical Huntington’s disease. Patient education and counseling. 2007;65(3):279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campodonico JR, Codori AM, Brandt J. Neuropsychological stability over two years in asymptomatic carriers of the Huntington’s disease mutation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;61(6):621–624. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.6.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Codori AM, Slavney PR, Rosenblatt A, Brandt J. Prevalence of major depression one year after predictive testing for Huntington’s disease. Genetic testing. 2004;8(2):114–119. doi: 10.1089/gte.2004.8.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paulsen JS, Hoth KF, Nehl C, Stierman L. Critical periods of suicide risk in Huntington’s disease. The American journal of psychiatry. 2005;162(4):725–731. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guidelines for the molecular genetics predictive test in Huntington’s disease. International Huntington Association (IHA) and the World Federation of Neurology (WFN) Research Group on Huntington’s Chorea. Neurology. 1994;44(8):1533–1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braude PR, De Wert GM, Evers-Kiebooms G, Pettigrew RA, Geraedts JP. Non-disclosure preimplantation genetic diagnosis for Huntington’s disease: practical and ethical dilemmas. Prenatal diagnosis. 1998;18(13):1422–1426. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0223(199812)18:13<1422::aid-pd499>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moutou C, Gardes N, Viville S. New tools for preimplantation genetic diagnosis of Huntington’s disease and their clinical applications. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12(12):1007–1014. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takala T. The right to genetic ignorance confirmed. Bioethics. 1999;13(3–4):288–293. doi: 10.1111/1467-8519.00157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burris S, Cameron E. The case against criminalization of HIV transmission. Jama. 2008;300(5):578–581. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCullough LB. Getting back to the fundamentals of clinical ethics. The Journal of medicine and philosophy. 2006;31(1):1–6. doi: 10.1080/03605310500499120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physicians’ charter. The Medical journal of Australia. 2002;177(5):263–265. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tassicker R, Savulescu J, Skene L, Marshall P, Fitzgerald L, Delatycki MB. Prenatal diagnosis requests for Huntington’s disease when the father is at risk and does not want to know his genetic status: clinical, legal, and ethical viewpoints. BMJ (Clinical research ed. 2003;326(7384):331–333. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7384.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleischman AR, Chervenak FA, McCullough LB. The physician’s moral obligations to the pregnant woman, the fetus, and the child. Semin Perinatol. 1998;22(3):184–188. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(98)80033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ensenauer RE, Michels VV, Reinke SS. Genetic testing: practical, ethical, and counseling considerations. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2005;80(1):63–73. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)62960-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Semaka A, Creighton S, Warby S, Hayden MR. Predictive testing for Huntington disease: interpretation and significance of intermediate alleles. Clin Genet. 2006;70(4):283–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]