Abstract

PURPOSE

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is important in fibrotic responses, formation of cancer stem cells and acquisition of a metastatic phenotype. Zeb1 represses epithelial specification genes to enforce epithelial-mesenchymal phenotypic boundaries during development, and it is one of several E-box-binding repressors whose overexpression triggers EMT. Our purpose was to investigate the potential role for Zeb1 in the EMT leading to dedifferentiation of retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells.

METHODS

Real time PCR was used to examine mRNA expression during RPE dedifferentiation in primary cultures of RPE cells from Zeb1(+/−) mice and following knockdown of Zeb1 by lentivirus shRNA. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation was used to detect Zeb1 a gene promoters in vivo.

RESULTS

Zeb1 is overexpressed during RPE dedifferentiation. Heterozygous mutation or shRNA knockdown to prevent this overexpression eliminates the onset of proliferation and the EMT which characterizes RPE dedifferentiation. One role of Zeb1 in this process is to bind directly to the Mitf promoter and repress its transcription. We link Zeb1 expression to cell-cell contact, and demonstrate that forcing dedifferentiated RPE cells to adopt cell-cell only contacts via sphere formation reverses overexpression of Zeb1 and reprograms RPE cells back to a normal phenotype.

CONCLUSION

Overexpression of the EMT transcription factor Zeb1 has an important role in RPE dedifferentiation via its regulation of Mitf and other epithelial specification genes. Expression of Zeb1, and in turn RPE dedifferentiation, is linked to cell-cell contact, and these contacts can be utilized to diminish Zeb1 expression and reprogram dedifferentiated RPE cells.

Introduction

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) early in embryogenesis is responsible for delamination of neural crest cells from the neural tube, and defining the ectodermal-mesodermal boundary required for gastrulation.1–3. Later in gestation, EMT is important in kidney and heart development. However, EMT is also central to pathologic fibrotic responses. And, it is a hallmark of carcinomas, where loss of cell-cell contacts, tight junctions and polarity, and onset of extracellular matrix degradation contribute to a proliferative, motile fibroblastic phenotype which facilitates metastasis.2, 3 Additionally, a similar EMT-like process also appears important in transition to metastatic melanoma, where loss of E-cadherin facilitates the release of melanocytes from their adhesion to keratinocytes.4 Furthermore, recent studies demonstrate that EMT is responsible for inducing the CD44 high/CD24 low expression pattern associated with formation of epithelial cancer stem cells.5

The phenotypic changes seen in EMT result at least in part from repression of epithelial specification genes by a set of related transcriptional repressors, including Snail (Snai) and zinc finger E-box binding homeodomain (Zeb) family members (Zeb1, also known as TCF8, delta-EF1, ZFHX1A and Zfhep and Zeb2, also know as smad interacting protein 1) (reviewed in 6). These EMT transcription factors bind overlapping sets of E-box promoter elements to repress epithelial specification genes such as E-cadherin.7–12

The EMT transcription factors become overexpressed in cancer and in fibrotic responses, and overexpression of any one of them appears sufficient to initiate EMT and cause the CD44 high/CD24 low pattern which precipitates cancer stem cell formation.5 Several of these factors have been shown to regulate normal epithelial-mesenchymal balance during development. Snai1 is required to establish the ectodermal/mesodermal boundary early in development, which is important for gastrulation (reviewed in 10). Snai1 mutants are characterized by expansion of E-cadherin expression and loss of the ectodermal/mesodermal boundary leading to failure of gastrulation. Later in gestation, Zeb1 appears to perform an analogous role in repression of epithelial specification genes to establish epithelial/mesenchymal phenotypic boundaries.13 In Zeb1 mutants, mesenchymal progenitors in the craniofacial region and skeleton and neural progenitors in the CNS ectopically express epithelial markers including E-cadherin and cytokeratins, and they show proliferative defects.13 Accordingly, late stage mutant embryos have severe craniofacial defects, skeletal curvatures, shortened limbs and digits, and a subset of the embryos has a severe neural phenotype, with failure of neural tube closure at both cranial and caudal ends leading to exencephaly.14 While Zeb1 heterozygous mice are viable, they show defective smooth muscle cell (mesenchymal) differentiation in response to vascular injury, leading to increased neointima formation.15 No defect in smooth muscle formation was evident in heterozygous mice prior to vascular injury, implying that this decrease in Zeb1 dosage is only crucial in response to injury. However, it has been demonstrated recently that heterozygous mutation of Zeb1 is responsible for posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (in both humans and mutant mice), which is characterized by a pathologic epithelial transition of the corneal endothelium, leading to corneal dysfunction.16–18 Thus in some tissues, decreasing the level of Zeb1 by heterozygous mutation appears sufficient to drive an epithelial-like transition in the absence of injury.

It is unclear how EMT transcription factors become induced in fibrotic responses or cancer to trigger EMT. Zeb1, for example, is not normally expressed in differentiated epithelium.13 Here, we examine EMT in retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells as a clinically relevant model of this fibrotic transition. The RPE forms a monolayer adjacent to photoreceptors in the retina, and these cells are essential for photoreceptor viability. RPE cells are normally contact-inhibited and thus nonproliferative in vivo. However upon retinal detachment, RPE cells can be dislodged into the vitreous where they bind the detached retina, initiate proliferation, undergo EMT and lose their pigment synthesis program. The resulting fibroblastic cells bound to the retina contract the retina preventing its reattachment. This condition is known as proliferative viteroretinopathy and it is the major complication in retinal reattachment surgery.19–22 It appears that the initiation of proliferation and inhibition of the pigment synthesis program in RPE cells is triggered by loss of cell-cell contact. If RPE cells are destroyed focally by laser treatment or by surgical debridement, cells on either side of the area of RPE loss initiate proliferation to fill in the gap.23 However, these proliferating cells are unable to initiate pigment synthesis and acquire a normal RPE phenotype, and they remain unpigmented after the gap is filled. Likewise, while sheets of RPE cells retain epithelial morphology and remain non-proliferative and pigmented in primary culture, disassociated cells in primary culture initiate proliferation and undergo EMT losing their pigment synthesis program.19, 20, 24

Here, we show that Zeb1 becomes overexpressed when RPE cells lose cell-cell contact, and this overexpression coincides with initiation of proliferation, EMT and loss of the pigment synthesis program. Heterozygous mutation of Zeb1 or shRNA knockdown to prevent this overexpression eliminated ectopic proliferation, EMT and loss of the pigment synthesis program. We link Zeb1 overexpression to repression of the pigment cell-specifying transcription factor, Mitf, which not only activates pigment cell-specific genes, but also prevents cell proliferation via activation of genes encoding cyclin dependent kinase (cdk) inhibitors.25, 26 Finally, we show that Zeb1 overexpression resulting from loss of cell-cell contact can be reversed by forcing cells to adopt cell-cell only contacts via sphere formation, and this reprograms the cells reversing the EMT and restoring the pigment synthesis program and a quiescent state.

Materials and Methods

Primary cell culture

Mouse RPE tissue was isolated from wild-type and Zeb1 heterozygous mice14 as described previously,44 and primary cultures were maintained in 10% fetal bovine serum and DMEM at 5% CO2. Cells were passaged 1:2 using trypsin/EDTA once they became confluent. All animals were handled according to the regulations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and all procedures adhered to the tenets of the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Sphere formation and Feeder layer preparation

For sphere formation, cells were scraped from tissue culture plates and transferred to nonadherent plates. For re-attachment, spheres were transferred to tissue culture plates or petri dishes containing feeder layer cells. Feeder layers were created by irradiating the SNL fibroblast cell line with 6,000 rads, to arrest cell proliferation, and subsequently plating the irradiated cells on tissue culture or petri dishes. Feeder layers remained viable and non-proliferative for more than a month in culture.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Sciences, Maryland, USA). cDNA was synthesized using the Invitrogen RT kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). SYBR Green real-time PCR was performed using Mx3000P Real-Time PCR System (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX) as described.37 The sequence and annealing temperature of PCR primers is shown in Supplementary Table 1. Three independent samples were analyzed for each condition and/or cell type, and each sample was compared in at least 3 independent RT-PCR amplifications.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays

ChIP assays were based on the UpState protocol (http://www.upstate.com/misc/protocol) using formaldehyde to crosslink genomic DNA.13 Polyclonal antiserum for Zeb1 and histone 3 were used for immunoprecipitation.13 Equal amounts of anti-IgG or pre-immune serum were used as controls. ChIP PCR reactions were similar to those described above for real-time PCR using primer sets (Supplementary Table 1) to amplify Mitf A and H promoters, and the GAPDH control promoter.

Lentivirus shRNA

The shRNA oligomers used for Zeb1 and Zeb2 silencing were described previously.15 Controls were performed for these sequences previously.15 Furthermore, the Zeb2 sequence differs in only 5 out of the 19 nucleotides, thus it serves as a control for the Zeb1 sequence. We first cloned the shRNA into a CMV-GFP lentiviral vector where its expression was driven by the mouse U6 promoter. Briefly, the shRNA construct was generated by synthesizing an 83-mer oligonucleotide containing: (i) a 19-nucleotide sense strand and a 19-nucleotide antisense strand, separated by a nine-nucleotide loop (TTCAAGAGA); (ii) a stretch of five adenines as a template for the Pol III promoter termination signal; (iii) 21 nucleotides complimentary to the 3′ end of the Pol III U6 promoter; and (iv) a 5′ end containing a unique XbaI restriction site. The long oligonucleotide was used together with a sp6 oligonucleotide (5′-ATTTAGGTGACACTATAGAAT-3′) to PCR-amplify a fragment containing the entire U6 promoter plus shRNA sequences; the resulting product was digested with XbaI and SpeI ligated into the NheI of the lentivirus vector, and the insert was sequenced to ensure that no errors occurred during the PCR or cloning steps. The detailed procedure is published elsewhere.45, 46 Lentiviral particles were produced by a four-plasmid transfection system as described.46 Briefly, 293T cells were transfected with the lentiviral vector and packaging plasmids, and the supernatants, containing recombinant pseudolentiviral particles, were collected from culture dishes on the second and third days after transfection. RPE cells were transduced with these lentiviral particles expressing shRNAs targeting Zeb1. A transduction efficiency of near 100% was achieved based on GFP-positive cells.

Cell images

Photographs of cells were taken using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted microscope and an AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Images were saved as JPEG files, which were directly imported to PowerPoint for assembly into figures.

Results

Dedifferentiation of RPE cells

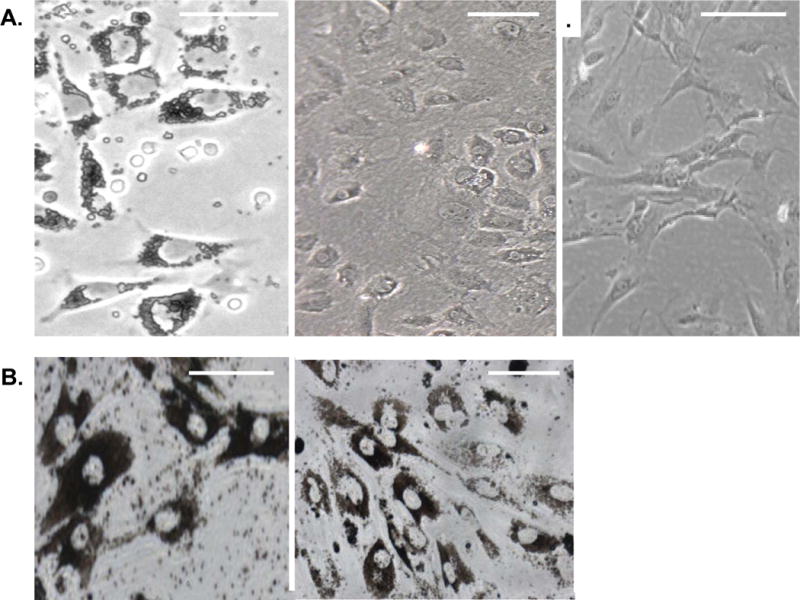

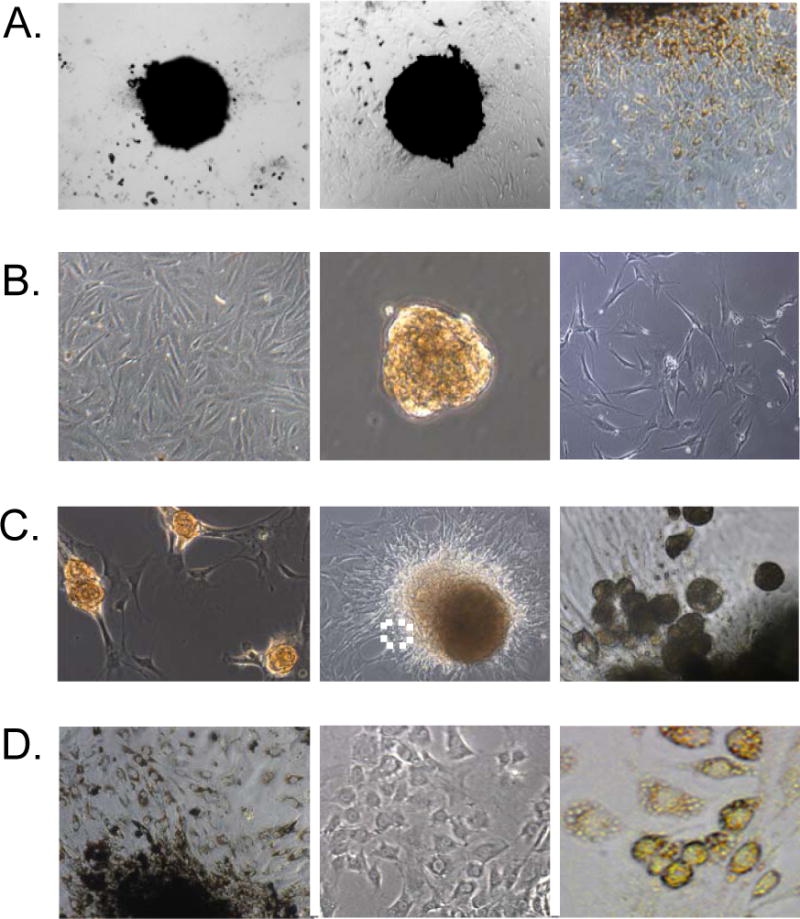

As noted above, RPE cells can be displaced into the vitreous as a result of retinal detachment. This displacement causes loss of normal cell-cell contacts leads to a dedifferentiation process characterized by ectopic proliferation on the detached retina, EMT and loss of the pigment synthesis program. Loss of cell-cell contacts can also be triggered in situ by focal destruction of RPE cells, or by placing disassociated RPE cells into primary culture, and these processes also lead to onset of proliferation, loss of epithelial morphology and loss of the pigment synthesis program.19, 20, 24Fig. 1A (left) shows disassociated RPE cells at day one in primary culture. The cells are initially pigmented and they exhibit epithelial morphology. However, after three passages, they lost pigment; however, many of them retained epithelial morphology (Fig. 1A, middle). However by passage 6, all of the cells lost epithelial morphology and became fibroblastic in appearance (Fig. 1A, right). Thus, loss of pigment occurs initially in the cultured cells, followed by transition to fibroblastic morphology.

Figure 1. Zeb1 mutation prevents dedi1fferentiation of RPE cells in culture.

A. Wild-type mouse RPE cells on day one in primary culture are shown on the left. Note the epithelial morphology and pigmentation. RPE cells at passage 3 in primary culture are shown in the middle. Note the loss of pigment. RPE cells at passage 6 in primary culture are shown on the right. Note the lack of pigment and the fibroblastic morphology. B. Zeb1 heterozygous RPE cells at day one in culture are shown on the left. Note the high level of pigment. Zeb1 mutant RPE cells after one month in culture are shown on the right. Scale bars are 25 microns.

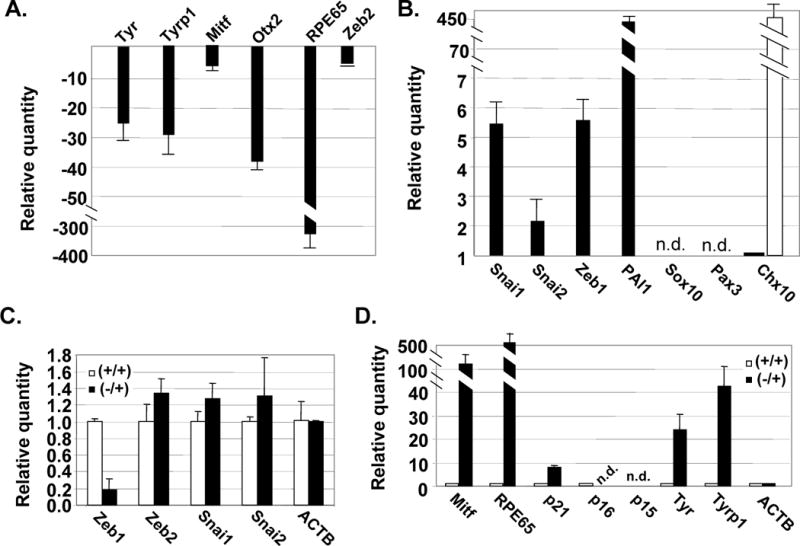

Downregulation of mRNA for Mitf and its target genes in dedifferentiated RPE cells

Next, we used real time PCR to compare mRNA expression in RPE tissue and dedifferentiated RPE cells in culture at passage 3. Notably, there was downregulation of Mitf mRNA in the dedifferentiated cells, which was also associated with downregulation of important Mitf target genes such as RPE65, and components of the pigment synthesis pathway, Tyr and Tyrp1 (Fig. 2A). Mitf cooperates with Otx2 in RPE cells to activate transcription, and both transcription factors are required for RPE formation in vivo.11, 25, 26 As with Mitf, we found that Otx2 mRNA was also downregulated in the dedifferentiated cells (Fig. 2A). Additionally, there was induction of PAI1 mRNA, a classic mesenchymal gene induced during EMT, which regulates extracellular matrix degradation and thus cell motility (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Effects of Zeb1 on mRNA expression in RPE cells in culture.

A. mRNA levels were compared by real time PCR in RPE tissue and RPE cells after 3 passages in culture. Genes repressed in cultured RPE cells. B. Genes induced in cultured RPE cells. The open bar indicates the relative level of Chx10 mRNA in newborn mouse retina. mRNA levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA (ACTB); n.d., not detected. C. Real time PCR analysis of the effects of heterozygous Zeb1 mutation on expression of Zeb1 mRNA and mRNAs for other EMT transcription factors. Wild-type (+/+) and Zeb1 heterozygous (+/−) cells at passage 1 were compared. D. Wild-type and Zeb1 mutant RPE cell RNA was isolated after 3 weeks in culture (passage 3 for the wild-type cells), and mRNA levels were compared using real time PCR. Fold differences are shown.

Chx10 is required to repress Mitf in forming retinal cells.28, 29 Therefore, we asked whether induction of Chx10 might be responsible for repressing Mitf in dedifferentiated RPE cells. However, we only detected a low level of Chx10 mRNA in RPE tissue, and this level did not increase in RPE cells in culture (Fig. 2B, solid bar). As a positive control, we did detect abundant Chx10 mRNA in the newborn mouse retina (Fig. 2B, open bar). Sox10 and Pax3 cooperate to induce Mitf expression in melanocytes;21, 37 however, we did not detect Sox10 or Pax3 mRNA in RPE tissue or cultured cells (Fig. 2B). Therefore, we conclude that neither induction of Chx10 nor loss of Sox10 or Pax3 is responsible for downregulation of Mitf mRNA in dedifferentiating RPE cells.

Overexpression of Zeb1 and Snai1 mRNA in dedifferentiating RPE cells

Because dedifferentiation of RPE cells has hallmarks of an EMT, we hypothesized that EMT transcription factors such as Zeb and Snai might be induced during the process. Real time PCR was used to compare the level of mRNA expression for Zeb and Snai family members in RPE tissue and dedifferentiated RPE cells in culture. Both Zeb1 and Snai1 mRNAs were overexpressed in dedifferentiated RPE cells (Fig. 2B). However, mRNA for Zeb2 was not induced, and Snai2 mRNA was only modestly induced. Because overexpression of Zeb1 or Snai has been shown to drive EMT in cancer (reviewed in 6), we hypothesized that this overexpression may contribute to the EMT-like dedifferentiation of RPE cells.

RPE cells from Zeb1 heterozygous mice do not undergo dedifferentiation or ectopic proliferation

Heterozygous mutation of Zeb1 led to ~5-fold reduction in mRNA (Fig. 2C) (such a >50% reduction with heterozygous mutation suggests that Zeb1 may be autoregulatory). Thus, Zeb1 overexpression in dedifferentiated wild-type RPE cells (Fig. 2B) is largely offset by heterozygous mutation (Fig. 2C). We noted that the Zeb1 heterozygous RPE cells were highly pigmented at day one in culture (Fig. 1A, left), and in contrast to cells from wild-type litter mates, the mutant cells did not lose pigment, nor did they transition to fibroblastic morphology (Fig. 1B). Thus, heterozygous mutation of Zeb1 appears to prevent dedifferentiation of the RPE cells. As a control, Zeb1 heterozygous mutation did not lead to a significant change in expression of other related EMT factors such as Snai1, Snai2, or Zeb2 (Fig. 2C).

A key event in RPE dedifferentiation is the onset of proliferation in the normally quiescent cells.22 This ectopic proliferation along with EMT contributes to the failure in surgical retinal reattachment in proliferative viteorretinopathy patients. Wild-type RPE cells immediately began to proliferate in culture with a doubling time at passage one of 28±5 hrs (Supplemental Fig. 1). And, this proliferative capacity did not diminish by passage eight (doubling time 24±4 hrs), when the cells had acquired fibroblastic morphology (as seen in Fig. 1A, right). By contrast, the number of Zeb1 mutant RPE cells remained stable for at least a month in culture. It is of note that the same cells were counted each day, and there was no evidence of Zeb1 mutant cell loss during this time in culture. Thus in addition to dedifferentiation, mutation of Zeb1 also prevents ectopic proliferation of RPE cells in culture.

Zeb1 mutation prevents repression of Mitf and Mitf target genes in cultured RPE cells

We compared expression of mRNAs for Mitf and its target genes in wild-type and Zeb1 heterozygous RPE cells in culture. Mitf and its target gene mRNAs were not downregulated in the mutant RPE cells, even after one month in culture (Fig. 2D). In fact, the level of Mitf mRNA in the heterozygous cells was higher than in normal RPE tissue (Fig. 2A and D; note that in these figures both normal RPE tissue and Zeb1 heterozygous RPE cells are compare to the same RPE cells at passage 3). Thus, heterozygous mutation of Zeb1 is sufficient to prevent downregulation of Mitf and Mitf target genes in RPE cells, even after prolonged culture.

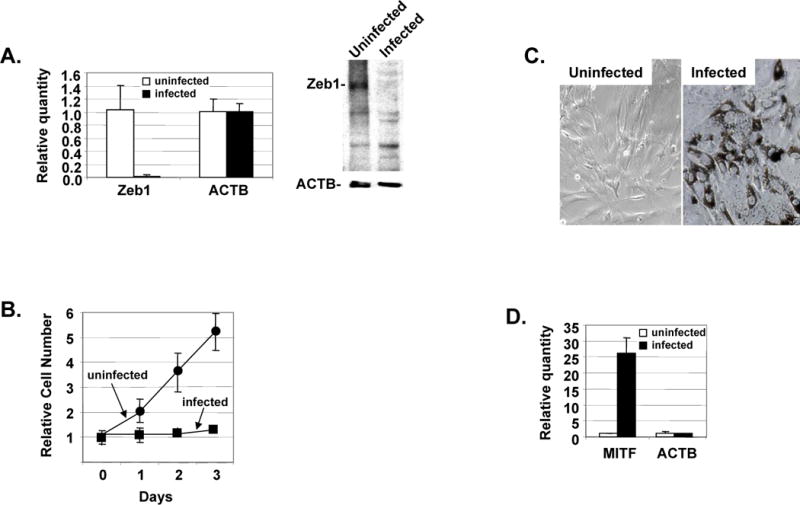

Lentivirus shRNA knockdown of Zeb1 prevents ectopic proliferation, loss of the pigment synthesis program, and repression of Mitf mRNA in RPE cells

shRNA knockdown of Zeb1 has been described previously.15 We created a lentivirus for knockdown of Zeb1 expression based on this previously described construct. RPE cells were transfected with the lentivirus and infection efficiency was assessed by GFP expression. Nearly 100% of the cells were infected, and Zeb1 mRNA and protein expression were effectively silenced (Fig. 3A). As with heterozygous mutation of Zeb1, lentivirus infection prevented proliferation of the RPE cells and the cells retained pigment after 4 weeks in culture, whereas uninfected cells had lost pigment and transitioned to a fibroblastic morphology (Fig. 3B–C). Accordingly, Mitf mRNA expression was maintained at a high level with Zeb1 knockdown (Fig. 3D). These results provide additional evidence that Zeb1 expression is linked to repression of Mitf, proliferation of RPE cells, and their EMT in culture. As a control for these experiments, the closely related Zeb2 family member was also knocked down by lentivirus shRNA. This led to a loss of Zeb2 mRNA and protein expression; however in contrast to knockdown of Zeb1, this knockdown of Zeb2 did not block proliferation (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Figure 3. shRNA knockdown of Zeb1 prevents proliferation and EMT of RPE cells in culture and it prevents repression of Mitf mRNA.

A. Real time PCR on the left shows Zeb1 Mrna levels were diminished in RPE cells one week after infection. A Western blot is show on the right demonstrating that Zeb1 protein expression was also diminished one week after infection of RPE cells. B. One week following infection, proliferation of infected and corresponding control uninfected cells was compared by counting cell number in culture dishes. C. Pigmentation and epithelial morphology is maintained in RPE cells for four weeks following infection (left). Uninfected cells which have lost pigment and undergone EMT are shown as a control. Mitf mRNA is still maintained at a high level four weeks after infection of RPE cells in culture. Fold differences as determined by real time PCR analysis are shown on the right.

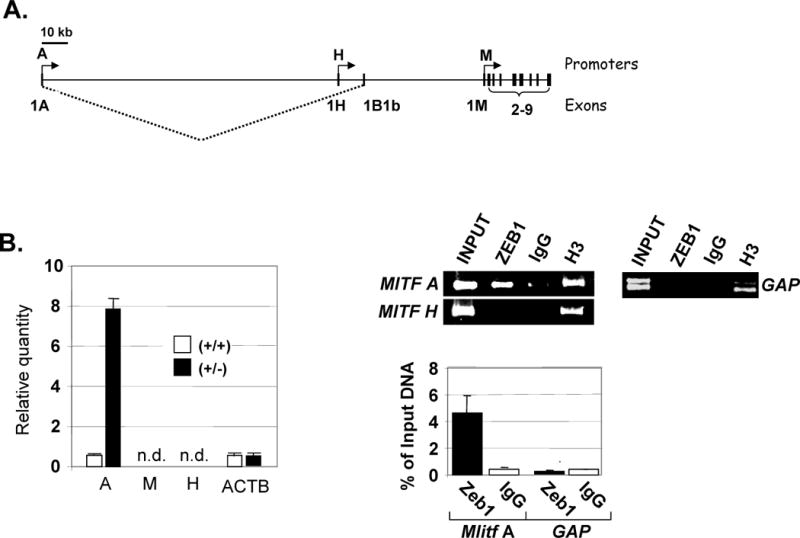

Zeb1 binds to and represses the Mitf A promoter

Mitf can be transcribed from multiple promoters, including M which is melanocyte-specific, H which is utilized in the heart, and A which is more widely utilized in cells, including RPE (32 and refs. therein). Real time PCR primers were designed to specifically amplify transcripts arising from the unique first exon transcribed from the three promoters (Fig. 4A; Supplemental Table 1). A low level of Mitf A promoter transcripts was evident in wild-type RPE cells at passage 3, but the level of these transcripts was high in Zeb1 heterozygous RPE cells (even after one month in culture) (Fig. 4B, left) (as occurred with total Mitf mRNA, Fig. 2D). These results suggest that transcripts arising from the Mitf A promoter are repressed by Zeb1 overexpression in the wild-type cells. We did not detect transcripts from the H and M promoters in either the wild-type or mutant RPE cells (Fig. 4B, left), suggesting that under these conditions the A promoter is primarily being utilized to transcribe Mitf.

Figure 4. Zeb1 binds to and represses the Mitf A promoter in vivo.

A. Diagram showing the genomic structure and transcripts arising from the Mitf A, H and M promoters. Note that a unique first exon is used by each promoter. B. Real time PCR analysis comparing the level of transcripts arising from each of the three Mitf exons, as in Fig. 2D, is shown on the left. ChIP assays were used to examine binding of Zeb1 and histone H3 to the Mitf A and H promoters. Gel electrophoresis of products is shown following real time PCR amplification on the top right and real time PCR quantitation of PCR products in shown on the bottom right. Results are presented as fold differences and as a percentage of input DNA in the precipitation. Gapdh (GAP) is a promoter control. See Supplemental Table 1 for PCR primers.

We wondered whether Zeb1-dependent repression of the Mitf A promoter in dedifferentiated RPE cells might be a direct effect of Zeb1 binding. Inspection of promoter sequences revealed potential Zeb1 E-box binding sites in the A promoter, but not the H promoter (results not shown). To determine whether Zeb1 was bound to these promoters in vivo, primers were designed to amplify a region approximately 700 bp upstream of each promoter. Chromatin was crosslinked to bound proteins and sheared to an average size of 1 kb, allowing detection of binding at least 1 kb upstream and downstream of the primer sites. This chromatin was then precipitated with anti-Zeb1 antibody, or as a negative control, with preimmune sera (IgG). As a positive control, chromatin was precipitated with an antibody to histone H3, which is ubiquitously present. Real time PCR was used to quantify the precipitated promoter fragments bound to Zeb1, and results were normalized to input DNA prior to immunoprecipitation. We found that Zeb1 was bound to the Mitf A promoter, but not the H promoter (Fig. 4B, right). Both promoters were bound by the positive control, histone H3. As an additional negative control, we did not detect Zeb1 binding to the Gapdh promoter (histone H3 was also evident at this promoter) (Fig. 4B, right).

Induction of p21CDKN1a in Zeb1 mutant RPE cells

In addition to its role in transactivation of genes important for RPE specification, Mitf also inhibits cell proliferation. This is due to its transactivation of cyclin dependent kinase (cdk) inhibitors, p21CDKN1a and p16INK4a.25, 26 These inhibitors block cdk2 and cdk4/6 activity, respectively.33, 34 Each of these cdks can drive proliferation, at least in part, through hyperphosphorylation and inactivation of the cell cycle inhibitory retinoblastoma protein (Rb). Because Mitf mRNA does not diminish in the Zeb1 mutant RPE cells in culture, we hypothesized that p21CDKN1a and p16INK4a mRNAs would be elevated in the mutant RPE cells, correlating with their lack of proliferation. Therefore, we used real time PCR to compare the level of p21CDKN1a and p16INK4a mRNA in wild-type and Zeb1 mutant RPE cells in culture. We did not detect p16INK4a mRNA in either the wild-type or Zeb1 mutant RPE cells, nor did we detect mRNA for p15INK4b, which also inhibits cdk4/6 (Fig. 2D). However, we did detect an increased level of p21CDKN1a mRNA in the mutant cells (Fig. 2D). This level of p21CDKN1a mRNA induction was similar to that seen in response to p53 activation during senescence of mouse embryo fibroblasts.35

Sphere formation reprograms dedifferentiated RPE cells back to a differentiated phenotype

We noticed that, on primary culture, RPE cells formed clusters of highly pigmented cells on tissue culture plates (Fig. 5A, left; Supplemental Fig. 2). Cells in the central regions of these clusters retained pigment and epithelial morphology and were non-proliferative, whereas at the periphery of these clusters, a monolayer of proliferating cells appeared; these proliferating cells migrated away from the original cluster, lost pigment, and acquired fibroblastic morphology (Fig. 5A, middle and right; Supplemental Fig. 2). With time, the central cluster became progressively smaller, finally giving way to dedifferentiated cells which could be maintained in culture for more than 10 passages. These observations suggested that dedifferentiation may be initiated by the loss of cell-cell contacts as cells at the periphery migrated away from neighboring cells. Indeed, the importance of confluency in maintaining RPE differentiation in culture has been suggested previously.36

Figure 5. Sphere formation reprograms dedifferentiated RPE cells back to a differentiated phenotype.

A. A cluster of wild-type RPE cells at day one in culture is shown on the left. Wild-type RPE cells after one week in culture are shown in the middle. Note the appearance of non-pigmented cells with fibroblastic morphology at the edge of the pigmented cells. A higher power view of the edge of the pigmented cells after one week in culture is shown on the right. B. Wild-type RPE cells at passage 8 are shown on the left. Passage 8 RPE cells at day one as spheres in suspension culture are shown in the middle, and feeder layer cells are shown on the right. C. RPE spheres bound to the feeder layer are shown on the left. RPE cells from spheres are shown in the middle migrating onto the feeder layer (day 3). A higher power view of the boxed region from the middle panel is shown on the right. D. RPE cells from spheres after migration onto the feeder layer (day 7) are shown on the left. RPE cells from spheres that migrated from the feeder layer onto the surrounding culture dish (day 7) are shown in the middle. And, RPE cells from spheres bound to feeder layer cells on petri dishes are shown on the right after one month in culture.

We then wondered whether dedifferentiated RPE cells in monolayer culture could be reprogrammed to a differentiated phenotype by re-establishing cell-cell contacts. To test this possibility, we forced dedifferentiated cells to establish cell-cell only contacts through sphere formation. Dedifferentiated RPE cells (Fig. 5B, left) at passage 8 in monolayer culture were scraped from culture dishes and placed in suspension in non-adherent dishes. The cells immediately formed spheres, which remained viable in culture for weeks (Fig. 5B, middle). The efficiency of sphere formation was high, with most cells forming spheres. It is of note that if cells were trypsinized and placed in suspension, they did not efficiently form spheres and the single cells rapidly (within hours) underwent apoptosis (known as anoikis when epithelial cells in suspension undergo apoptosis; 13) (results not shown). We noticed that the cells became pigmented within a day after sphere formation (Fig. 5B, middle), demonstrating that pigment synthesis was restored.

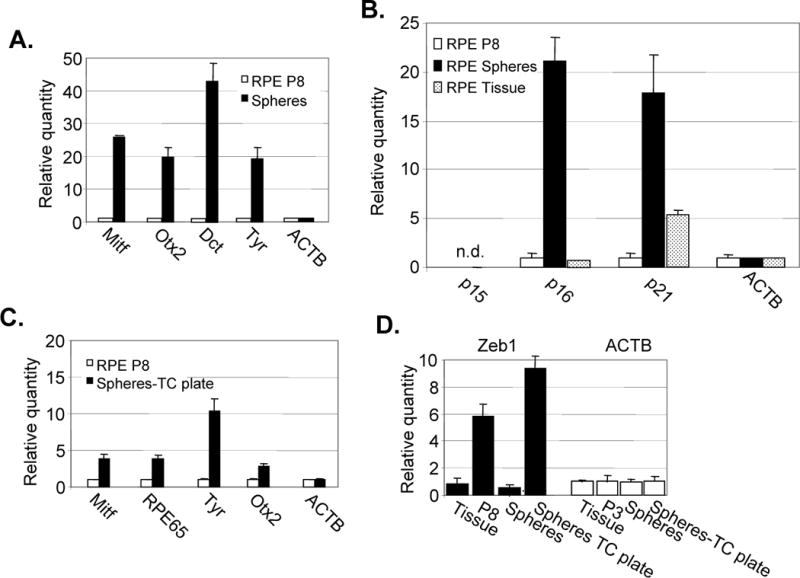

Real time PCR was used to compare expression of mRNAs in dedifferentiated RPE cells at passage 8 in monolayer culture to cells from the same culture, but which had undergone two additional days of sphere formation. Sphere formation led to re-expression of Mitf mRNA and upregulation of mRNAs for Mitf target genes including RPE65 and genes involved in pigment synthesis (Fig. 6A). Additionally, we found re-expression of Otx2 mRNA. Indeed, expression of these mRNAs in spheres was induced to a level similar to that seen in RPE tissue (Fig. 2A and 6A; note that expression in RPE tissue and RPE spheres is compared to passage 3 RPE cells in both figures). Thus, sphere formation effectively restores RPE-specific gene expression in the dedifferentiated cells.

Figure 6. Sphere formation represses Zeb1 and induces genes important for RPE specification and cell cycle arrest.

A. Real time PCR analysis comparing mRNA expression in RPE cells at passage 8 (P8). before and after two days of sphere formation. B. Real time PCR showing the effects of sphere formation on expression of cdk inhibitor mRNAs. “n.d.”, not detected. C. Real time PCR showing diminished expression of RPE genes in cells from spheres that migrated back onto a tissue culture plate for one week (Sphere-TC plate). (see Fig. 5D, middle above). D. Real time PCR comparing the effects of RPE cell culture, sphere formation and migration of cells from spheres back onto a tissue culture dish (Sphere-TC plate, as in panel C above) on Zeb1 mRNA levels. Fold differences in mRNA levels are shown by real time PCR.

RPE cells in vivo are quiescent (Supplemental Fig. 1), and as noted above, Mitf can maintain cell cycle arrest though induction of the cdk inhibitors, p16INK4a and p21CDKN1a.6, 26 Therefore, we asked whether the induction of Mitf mRNA seen on sphere formation coincided with induction of mRNA for these two cdk inhibitors. Indeed, we found that mRNAs for both p16INK4a and p21CDKN1a were induced with sphere formation (Fig. 6B). And consistent with induction of these cdk inhibitors, cells in spheres were not proliferative (Supplemental Fig. 4).

Cells from RPE spheres can reform monolayers and again undergo dedifferentiation

We wondered whether reprogrammed RPE cells in spheres would migrate from the spheres to reform a monolayer. However, the spheres did not attach efficiently to tissue culture dishes, therefore we plated them on a feeder layer of embryo fibroblasts that had been irradiated to block their proliferation (as is used for culture of embryonic stem cells) (Fig. 5B, right). The spheres attached efficiently to the feeder layer (Fig. 5C, left), and cells begin migrating from the spheres onto the feeder layer (Fig. 5C, middle and right). The RPE cells initially migrating from the spheres were round and highly pigmented; however, as they attached to the feeder layer the cells took on an epithelial morphology and they maintained pigmentation (Fig. 5C, middle and right; Fig. 5D, left). However after a week in culture, cells began to migrate from the feeder layer onto the surrounding culture dish, and as this occurred, the cells became proliferative and lost pigment (Fig. 5D, middle). At this point, the cells resembled cells in monolayer culture at passage 3 (Fig. 1A, middle). Subsequently, the cells transitioned to a fibroblastic morphology (appearing like cells in Fig. 1A, right; results not shown). These results suggested that the cells from the spheres were again undergoing dedifferentiation as they migrated onto the tissue culture dish. Consistent with this notion, real time PCR analysis revealed a diminished level of mRNAs for Mitf and Otx2 (compare Fig. 6A and C).

Forcing reprogrammed RPE cells from spheres to maintain association with the feeder layer prevents dedifferentiation

We wondered whether reprogrammed RPE cells derived from spheres would maintain a differentiated phenotype if they were forced to remain adherent to feeder layer cells (e.g., if they were prevented from migrating onto the surrounding culture dish). We noticed that while the SNL cell line used to derive feeder layer cells could adhere to petri dishes, cells from RPE spheres could not (they would only attach to tissue culture dishes). Therefore, we allowed RPE spheres to adhere to feeder layers plated on petri dishes. Cells from the spheres migrated onto the feeder layer, but they did not subsequently migrate onto the petri dish. Under these conditions where cell-cell contact with the feeder layer was forcibly maintained, the cells from RPE spheres remained viable and pigmented as a non-poliferative monolayer for more than a month in culture (Fig. 5D, right).

Zeb1 expression is regulated during RPE dedifferentiation and reprogramming

Above, we showed that Zeb1 is overexpressed as RPE cells initiate proliferation and undergo dedifferentiation in culture, and heterozygous mutation of Zeb1 to prevent this overexpression eliminated proliferation and dedifferentiation of the RPE cells. Therefore, we wondered whether Zeb1 expression was downregulated during sphere formation (which restores an RPE-like differentiated, non-proliferative phenotype). We compared the level of Zeb1 mRNA in RPE tissue, dedifferentiated cells in monolayer culture, dedifferentiated cells induced to form spheres, and monolayer cells derived from the spheres which had migrated onto culture dishes, lost pigmentation and begun proliferation (cells resembling those in Fig. 5D, middle). We found that sphere formation repressed Zeb1 mRNA, and that its level was re-induced as cells from the spheres re-formed a monolayer on tissue culture plates and again lost pigment (Fig. 6D). Thus, the level of Zeb1 mRNA is inversely correlated with RPE differentiation.

Discussion

Overexpression of Zeb1 during RPE cell dedifferentiation appears to directly repress the Mitf A promoter. Concomitant with this repression, there is downregulation of Mitf target genes including genes involved in pigment synthesis, RPE65, and the cdk inhibitor p21CDKN1a. Thus, Zeb1-mediated repression of Mitf could conceivably account for both the EMT and ectopic proliferation seen in dedifferentiating RPE cells. However, Zeb1 overexpression also repressed expression of Otx2 (which is required along with Mitf for RPE formation in vivo), and Zeb1 is known to repress epithelial specification genes involved in cell-cell contact (E-cadherin), tight junction formation (the Pals1 family) and polarity (Crumbs3 and Hugl2) in non-pigmented epithelial cells.6, 8 Repression of these genes is thought to facilitate the characteristic transition from epithelial to fibroblastic morphology seen in EMT. Taken together, these results imply that Zeb1 overexpression may have effects beyond repression of Mitf. For example, mutation of Zeb1 leads to alterations in epithelial vs. mesenchymal phenotypic balance in non-pigmented cells in vivo,18 and in mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) Zeb1 mutation leads to induction of epithelial specification genes such as E-cadherin and to epithelial morphology in the fibroblasts. Mitf mRNA is not induced in the mutant MEFs, and the mutant cells do not become pigmented13 (Supplemental Fig. 5). Thus, Zeb1’s role in regulating epithelial vs. mesenchymal balance appears separable from its repression of Mitf and its role in pigment cell differentiation. And, we suggest that its repression of Mitf and inhibition of RPE differentiation only become evident when it is overexpressed.

Interestingly, Zeb1 mutation inhibits cell proliferation in MEFs and at sites of developmental defects in non-pigmented cells in vivo.13 These proliferative defects are associated with induction of cdk inhibitors, but not with a change in Mitf expression (Supplemental Fig. 5). Zeb1 can bind directly to the p21CDKN1a promoter,37 and Mitf can also bind to this promoter in vivo,25 thus ectopic proliferation and repression of p21CDKN1a seen with Zeb1 overexpression in dedifferentiating RPE cells may be due to both direct repression by Zeb1 as well as downregulation of the transcriptional activator, Mitf. While overexpression of a repressor and downregulation of a transactivator would provide for efficient repression of p21CDKN1a, coordinate regulation by Zeb1 and Mitf may prove even more complex. It is of note that both Zeb1 and Mitf are E box binding proteins which bind to variations of the core sequence CANNTG. Mitf can bind to CATGTG, CACGTG, and CAGCTG,38, 39 whereas Zeb1 binds efficiently to CACCTG (40, 41). However, Zeb1 also binds to the CACGTG sequence bound by Mitf (41). Further, the E-box sites in the p21CDKN1a promoter contain the sequence CAGCTG, and both Mitf and Zeb1 have been shown to bind these sites in vivo,13, 25 Thus, it is possible that overexpression of Zeb1, coupled with downregulation of Mitf, allows Zeb1 to compete effectively with Mitf for binding to common E-boxes, not only on the p21CDKN1a promoter, but on the promoters of other Mitf target genes. In this regard, it is of note that E-boxes in the Tyr promoter contain the same CAGCTG sequence.39

We demonstrate here that Zeb1 expression is repressed by cell-cell contact, and its induction in RPE cells which have lost cell-cell contact triggers proliferation as well as loss of epithelial morphology and pigment synthesis. Cell contact inhibition is mediated by the cell cycle control pathway consisting of the Rb family and their E2F transcription factor binding partners (reviewed in 14). Indeed, mutation or inhibition of the Rb family eliminates cell contact inhibition.42 E2F binds directly to the Zeb1 gene promoter, and an Rb-E2F complex represses transcription of Zeb1.37 Therefore, it is likely that Zeb1 is repressed upon cell-cell contact by the Rb family-E2F complexes which form to mediate the cell cycle arrest leading to contact inhibition. Consistent with this notion, Zeb1 expression in vivo in the developing mouse embryo is closely linked to cell proliferation.18, 43

Our results link cell-cell contact to proliferation, EMT and maintenance of the pigment synthesis program in RPE cells. These processes in RPE cells are all regulated by Zeb1 expression, which in turn is controlled by cell-cell contact. Finally this ectopic proliferation, EMT and the loss of the pigment synthesis program can all be reversed by forcing dedifferentiated cells to adopt cell-cell only contacts through sphere formation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Higashi for Zeb1 mutant mice, and Diego Montoya-Durango for assistance with chromatin preparation. These studies were supported in part by NIH Grants (P20 RR018733, EY015636, and EY017869), Research to Prevent Blindness, and The Commonwealth of Kentucky Research Challenge.

References

- 1.Cheung M, Chaboissier MC, Mynett A, Hisrt E, Shedl A, Briscoe J. The transcriptional control of trunk neural crest induction, survival and delamination. Dev Cell. 2005;8:179–92. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay ED. An overview of epithelio-mesenchymal transformation. Acta Anat. 1995;154:8–20. doi: 10.1159/000147748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and pathologies. Curr Opion Cell Biol. 2003;15:740–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alonso SR, Tracey L, Ortiz P, Perez-Gomez B, Palacious J, Pollan M, Linares J, Serran S, Saez-Castillo AI, Sanchez L, Pajares R, Sanchez-Aquilera A, Artiga MJ, Piris MA, Rodriguez-Peralto JL. A high-throughput study in melanoma identifies epithelial-mesenchymal transition as a major determinant of metastasis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3450–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mani S, Guo W, Liao M-J, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shititsin M, Campbell LL, Polylak K, Brisken C, Yang J, Weinberg RA. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progresion: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–28. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chinnadurai G. CtBP an unconventional transcriptional corepressor in development and oncogenesis. Mol Cell. 2002;9:213–24. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00443-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eger A, Aigner K, Sonderegger S, Dampier B, Oehler S, Schreiber M, Berx G, Cano A, Beug A, Foisner R. DeltaEf1 is a transcriptional repressor of e-cadherin and regulates epithelial plasticity in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:2375–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frisch SM, Screaton RA. Anoikis mechanisms. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:555–62. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemavathy K, Ashraf SL, Ip YT. Snail/slug family of repressors, slowly going into the fast lane of development and cancer. Gene. 2005;257:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00371-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murisier F, Guichard S, Beermann F. The tyrosinase enhancer is activated by sox10 and Mitf in mouse melanocytes. Pigment Cell Res. 2007;20:173–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2007.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Postigo AA, Dean DC. ZEB represses transcription through interaction with the corepressor CtBP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6683–6688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, El-Naggar S, Darling DS, Higashi Y, Dean DC. Zeb1 links epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cellular senescence. Development. 2008a;135:579–88. doi: 10.1242/dev.007047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takagi T, Moribe H, Kondoh H, Higashi Y. DeltaEF1: a zinc finger and homeodomain transcription factor, is required for skeleton patterning in multiple lineages. Development. 1998;125:21–31. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishimura G, Manabe I, Tsushima K, Fujiu K, Oishi Y, Imai Y, Maemura K, Miyagishi M, Higashi Y, Kondoh H, Nagai R. Delta EF1 regulates TGF-beta signaling in vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation. Dev Cell. 2006;11:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krafchak CM, Pawar H, Moroi SE, Kijek TG, Krafchak CM, Othman MI, Vollrath D, Ellner VM, Richards JE. Mutations in TCF8 cause posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy and ectopic expression of COL4A3 by corneal endothelial cells. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:694–708. doi: 10.1086/497348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liskova P, Tuft SJ, Gwilliam R, Ebenezer ND, Jirsova K, Prescott Q, Martincova R, Pretorius M, Sinclair N, Boase DL, Jeffrey MJ, Deloukas P, Hardcastle AJ, Filipec M, Bhattacharya SS. Novel mutations in the ZEB1 gene identified in Czech and British patients with posterior polymophous corneal dystrophy. Hum Mut. 2007;28:638. doi: 10.1002/humu.9495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Peng X, Tan J, Darling DS, Kaplan HJ, Dean DC. Zeb1 mutant mice as a model of posterior corneal dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008b;49:1843–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abe T, Sato M, Tamai M. Dedifferentiation of the retinal pigment epithelium compared to the proliferative membranes of proliferative viteroretinopathy. Curr Eye Res. 1998;17:1103–9. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.17.12.1103.5126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alge CS, Suppmann S, Priglinger SG, Neubauer S, May CA, Hauk S, Weigelussen UU, Ueffing M, Kampik A. Comparative proteome analysis of native differentiated and cultured dedifferentiated human RPE cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3629–41. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiscott P, Sheridan C, Magee RM, Grierson I. Matrix and the retinal pigment epithelium in proliferative retinal disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:167–90. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Del Priore LV, Hornbeck R, Kaplan HJ, Jones Z, Valentino TL, Mosinger-Oglivie J, Swinn M. Debridement of the pig retinal pigment epithelium in vivo. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:939–944. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100070113034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee SC, Kwon OW, Seong GJ, Kim SH, Ahn JE, Kay ED. Epitheliomesenchymal transdifferentiation of cultured RPE cells. Ophthalmic Res. 2001;33:80–6. doi: 10.1159/000055648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carreira S, Goodall J, Aksan I, La Rocca SA, Galibert MD, Denat L, Larue L, Goding CR. Mitf cooperates with Rb1 and activates p21Cip1 expression to regulate cell cycle progression. Nature. 2005;433:764–9. doi: 10.1038/nature03269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loercher AE, Tank EM, Delston RB, Harbour JW. Mitf links differentiation with cell cycle arrest in melanocytes by transcriptional activation of INK4a. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:35–45. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bharti K, Nguyen M-T, Skuntz S, Bertuzzi S, Arnheiter H. The other pigmented cells: specification and development of the pigmented epithelium of the vertebrate eye. Pigment Cell Res. 2006;19:380–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2006.00318.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horsford DJ, Nguyen MT, Sellar GC, Kothary R, Arnheiter H, McInnes RR. Chx10 repression of Mitf is required for the maintenance of mammalian neuroretinal identity. Development. 2005;132:177–87. doi: 10.1242/dev.01571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowan S, Chen CM, Young TL, Fisher DE, Cepko CL. Transdifferentiation of the retina into pigmented cells in ocular retardation mice defines a new function of the homeodomain gene Chx10. Development. 2004;131:5139–52. doi: 10.1242/dev.01300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee M, Goodall J, Verastegui C, Ballotti R, Goding CR. Direct regulation of the microphthalmia promoter by sox10 links Waardenburg-Shah syndrome WS4.-associated hypopigmentation and deafness to WS2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37978–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potterf SB, Furumura M, Dunn KJ, Arnheiter H, Pavan WJ. Transcription factor heirarchy in Waardenburg syndrome: regulation of Mitf expression by Sox10 and Pax3. Hum Genet. 2000;107:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s004390000328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sagi T, Sonnenblick A, Yannay-Cohen N, Kay G, Nechushtan H, Razin E. Microphthalmia transcription factor isoforms in mast cells and the heart. Molec Cell Biol. 2007;27:3911–19. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01455-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harbour JW, Dean DC. The Rb/E2F pathway: expanding roles and emerging paradigms. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:2393–409. doi: 10.1101/gad.813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowe SW, Sherr CJ. Tumor suppression by INK4a-Arf, progress and puzzles. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:77–83. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sekido R, Murai K, Funahashi J, Kamachi Y, Fujisawa-Sehara A, Nabeshima Y, Kondoh H. The delta-crystallin enhancer-binding protein delta EF1 is a repressor of E2-box-mediated gene activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5692–700. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.5692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maminishkis A, Chen S, Jalickee S, Banzon T, Shi G, Wang FE, Ehalt T, Hammer JA, Miller SS. Confluent monolayers of cultured human fetal retinal pigment epithelium exhibit morphology and physiology of native tissue. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3612–24. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y, Constatino ME, Montoya-Durango D, Higashi Y, Darling DS, Dean DC. The zinc finger transcription factor, ZFHX1A, is linked to cell proliferation by Rb/E2F1. Biochem J. 2007;408:79–85. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aksan I, Goding CG. Targeting the microphthalmia basic helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper transcription factor to a subset of E-box elements in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6930–8. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.6930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez-Morales JR, Signore M, Acampora D, Simeone A, Bovolenta P. Otx genes are required for tissue specification in the developing eye. Development. 2001;128:2019–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.11.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Postigo AA, Dean DC. Differential expression and function of members of the zfh-1 family of zinc finger/homeodomain repressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6391–6396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sears R, Leone G, Degregori J, Nevins JR. Ras enhances Myc protein stability. Mol Cell. 1999;3:169–79. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang HS, Postigo AP, Dean DC. Active transcriptional repression by the Rb-E2F complex mediates G1 arrest triggered by p16INK4a, TGF-beta, and contact inhibition. Cell. 1999;97:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80714-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Darling D, Stearman RP, Qi Y, Qiu MS, Feller JP. Expression of Zfhep/deltaEf1 protein in palate, neural progenitors and differentiated neurons. Gene Expr Patterns. 2003;3:709–17. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00147-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Enzmann V, Row BW, Yamauchi Y, Kheirandish L, Gozal D, Kaplan HJ, McCall MA. Behavioral and anatomical abnormalities in a sodium iodate-induced model of retinal pigment epithelium degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:441–8. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singer O, Marr RA, Rockenstein E, Crews L, Coufal NG, Gage FH, Verma IM, Masliah E. Targeting BACE1 with siRNAs ameliorates Alzheimer disease neuropathology in a transgenic model. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1343–1349. doi: 10.1038/nn1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tiscornia G, Singer O, Verma IM. Design and cloning of lentiviral vectors expressing small interfering RNAs. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:234–240. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.