Abstract

We recently identified a pivotal role for the host type I interferon (IFN) pathway in immuno-surveillance against de novo mouse glioma development, especially through the regulation of immature myeloid cells (IMCs) in the glioma microenvironment. Using these data, we identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in human IFN genes that dictate altered prognosis of patients with glioma. One of these SNPs (rs12553612) is located in the promoter of IFNA8, whose promoter activity is influenced by rs12553612. Conversely, recent epidemiologic data show that chronic usage of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs lowers the risk of glioma. We translated these findings back to our de novo glioma model and found that cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition enhances anti-glioma immuno-surveillance by reducing glioma-associated IMCs. Taken together, these findings suggest that alterations in myeloid cell function condition the brain for glioma development. Finally, we have begun applying novel immunotherapeutic approaches to patients with low-grade glioma with the aim of preventing malignant transformation. Future research will hopefully better integrate epidemiological, immunobiological, and translational techniques to develop novel preventive approaches for malignant gliomas.

Keywords: interferon, glioma, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, single nucleotide polymorphism

Inflammation-related genetic and immunologic factors in glioma development

Glioma accounts for approximately 40% of all primary brain tumors and are responsible for roughly 13,000 cancer-related deaths in the United States each year.1 World Health Organization (WHO) grade IV glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and most malignant of the glial tumors, with a median survival of 15 months. Other common types of malignant glioma are WHO grade III anaplastic glioma, including anaplastic astrocytoma, which has a median survival of 24–36 months. WHO grade II low-grade gliomas (LGGs) are slow-growing primary brain tumors with infiltrative growth characteristics in the brain, and therefore have an extremely high risk of progression following treatment with surgery, or surgery followed by radiation therapy (RT).2–10 There is no curative treatment because these tumors grow aggressively and invasively in the central nervous system (CNS). More than 50% of these patients eventually recur with aggressive WHO grade III or IV high-grade gliomas (HGGs),6,7,11,12 and most LGG patients eventually die of the disease.

Predicting which populations are at risk for glioma is difficult: established risk factors (exposure to ionizing radiation, rare mutations of penetrant genes, and family history) account for only a small proportion of brain tumors.13 Recent reports suggest the involvement of inflammation-related genetic and immunologic factors in gliomagenesis,14–26 including studies by our group.18,27–32 Interestingly, independent studies by multiple groups have reported similar observations as summarized below: (1) A history of asthma and allergies as well as higher immunoglobulin E levels has been associated with a protective effect against glioma development and prognosis.18,19,21,22,24,25 SNPs that increase asthma risk also seem to be associated with reduced risk of glioma.16 Downregulation of the majority of allergy- and inflammation-related genes is associated with more aggressive GBM progression.14 Among populations reporting a history of asthma or allergies with asthma, regular long-term use of antihistamine is significantly associated with an increase in the risk for glioma;28,29 (2) SNPs in interleukin-4 receptor-α (IL-4Rα) are associated with altered glioma risk and prognosis;15,27 and (3) chronic use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is associated with reduced glioma risk.17,28,29 Although these data point to a role for immunologic and genetic factors in gliomagenesis, the relationship among these factors, and the biological mechanisms underlying these observations, warrant further study.

Integration of mechanistic and epidemiological studies

Our goal is to fill an important gap in our mechanistic understanding of factors that influence the risk and prognosis of glioma identified through epidemiologic studies; and translate these findings to the clinic through preclinical mouse and genomic studies as well as early phase clinical trials. To this end, we are working to integrate state-of-the-art human epidemiology, cell biology, and novel mouse glioma models in a thematic, hypothesis-driven manner.

Type I IFNs in immunological responses against glioma: preclinical mouse studies

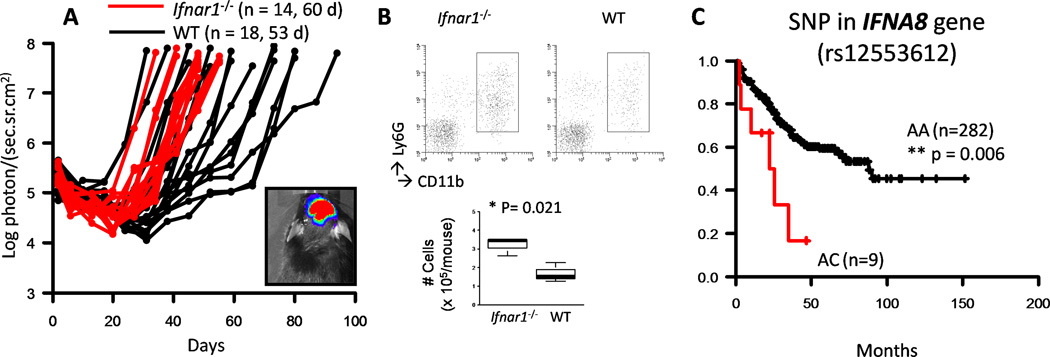

We have long been interested in the role of type I IFNs in immunological responses against glioma.33–36 Using a novel de novo mouse glioma model,37 we investigated the role of the type I IFN pathway in glioma development by inducing de novo gliomas in interferon (IFN)-α receptor1–deficient (Ifnαr1−/−) mice. This study identified a pivotal role for the host IFN-α pathway in protecting against glioma development (Fig. 1A), especially through the downregulation of IMCs (Fig. 1B), which most likely include myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), in the glioma microenvironment.30 Based on these data, we evaluated and identified SNPs in human IFNA genes associated with the prognosis of patients with glioma.30 One of these SNPs, rs12553612, is located in the IFNA8 promoter and is associated with better overall survival of glioma patients with the AA-genotype compared with patients with the AC-genotype (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Effects of IFN-α gene alterations on glioma development in mice and humans. (A, B), Gliomas were induced in C57BL/6 background Ifnar1−/− (red lines) or wild-type (WT; black lines) neonatal mice by intraventricular transfection of plasmids: pT2/C-Luc//PGK-SB1.a3 (0.2 µg), pT/CAG-NRas (0.4 µg), and pT/shp53 (0.4 µg). (A) Tumor growth was monitored. (B) The mice bearing SB-induced tumors were sacrificed at days 50–60, and brain infiltrating leukocytes (BILs) were isolated based on similar tumor size observed by bioluminescence imaging (BLI). BILs obtained from three mice in a given group were pooled and evaluated by flow cytometry for CD11b+Ly6G+ IMCs. Absolute IMC numbers in three independent experiments are depicted in the bottom panels. P values are based on Student's t-test. (C) Overall survival was evaluated among 291 glioma patients with WHO grade 2–3 gliomas by genotype for SNPs in IFNA8 rs12553612. Patients with AC genotype (red line) exhibited a significantly shorter survival than those with the AA genotype (black line). Reproduced, with permission, from Fujita et al.30

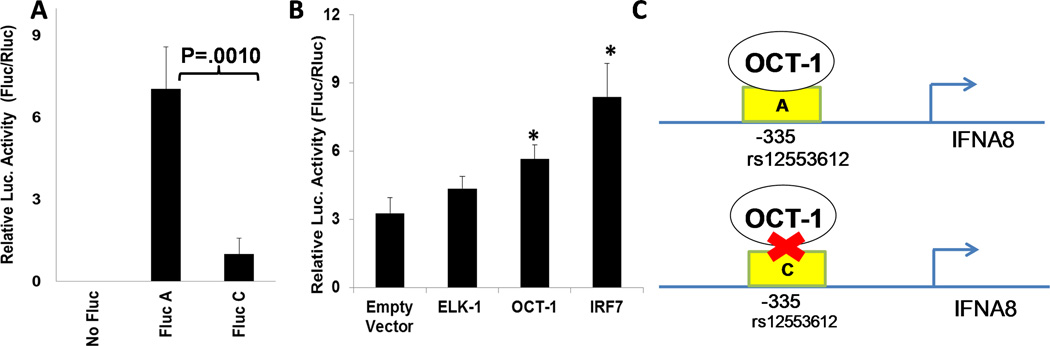

We subsequently hypothesized that the A-allele allows for enhanced IFNA8 promoter activity compared with the C-allele. We performed reporter assays in the human monocyte–derived THP-1 cell line, which demonstrated superior promoter activity of the A-allele compared with the C-allele (Fig. 2A).38 We then used electrophoretic mobility shift assays to demonstrate that the A-genotype specifically binds to more nuclear proteins than the C-genotype, including the transcription factor Oct-1.38 When we co-transfected plasmids encoding Oct-1 and the reporter constructs, we observed that Oct-1 enhanced the promoter activity with the A- but not the C-allele (Fig. 2B; shown only for the A-allele).38 Taken together, our data demonstrate that the A-allele in the rs12553612 SNP, which is associated with better patient survival, allows for IFNA8 transcription via Oct-1 binding, absent in patients with the C allele (Fig. 2C),38 and suggests a molecular mechanism for IFNA8-mediated immune-surveillance of glioma progression.

Figure 2.

Interferon (IFN)-A8 promoter activity with the A-genotype at −335 is superior to that with the C-genotype. (A) THP-1 cells (1×105) were co-transfected with 0.02 µg of pGL4 vector encoding Renilla luciferase (Rluc) as internal control and 0.18 µg of pGL4 vector encoding Firefly luciferase downstream of IFNA8 promoter with A- or C-genotype (A-Fluc and C-Fluc). Twenty-four hours after the co-transfection, luc activity was measured from triplicate cell-lysates, and relative luciferase was calculated (Fluc/Rluc). (B) THP-1 cells were transfected with the A-genotype Fluc-reporter plasmid and the internal control Rluc plasmid as well as an expression plasmid encoding ELK-1, OCT-1, or IRF-7 as a positive control. Relative luciferase was calculated as Fluc/Rluc. Results are from one of two experiments with similar results. *Indicates that the values were statistically different (P < 0.05) from the control samples with the empty vector by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. Error bars indicate standard deviation among triplicate sample. OCT-1 transfection did not enhance the activity of the C-genotype Fluc-reporter (shown in the full paper). (C) Schematic demonstrating the OCT-1 binding ability to the IFNA8 promoter region containing the rs12553612 SNP. Reproduced, with permission, from Kohanbash et al.38

COX-2 blockade suppresses gliomagenesis: inhibition of immature myeloid cells

Epidemiological findings led to the discovery of key mechanisms and insights contributing to the development of therapeutic and prophylactic strategies. Specifically, based on epidemiological observations28,29 that chronic use of NSAIDs is associated with reduced risk of glioma,17,28,29 we translated these findings back to a novel de novo glioma model37 and found that cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibition enhances anti-glioma immuno-surveillance by reducing glioma-associated myeloid cells.39 COX-2 and its product prostaglandin E (PGE)2 are known to promote tumor growth and immune escape of tumors through a variety of mechanisms, including the differentiation of Gr-1+ CD11b+ immunosuppressive IMCs from bone marrow stem cells.40 Furthermore, PGE2 produced by the tumor induces arginase 1 and cationic amino acid transporter (CAT)-2B in IMCs, both of which deplete arginine from the tumor microenvironment and impair T cell function.41,42 Data from the de novo glioma model demonstrate that treatment with the COX-2 inhibitors acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) or celecoxib inhibited systemic PGE2 production and delayed glioma development.39 ASA treatment also reduced monocyte chemoattracting protein-1, also known as CCL2 (C-C motif ligand 2), in the glioma as well as the number of IMCs in both bone marrow and the glioma. Both ASA-treated and Cox2−/− mice demonstrated a reduction in IMCs and their CCL2-mediated accumulation in the glioma. Conversely, Cox2−/− mice and ASA-treated wild-type mice displayed enhanced expression of CXCL10 (C-X-C motif chemokine 10) and tumor-infiltration of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs).39

Although these findings suggest that COX-2 inhibition may be applied to the prevention of gliomas, the use of COX-2 inhibitors, such as celecoxib, to prevent glioma may not be justifiable in the general population due to the increased risk of cardiovascular sequelae43 and gastrointestinal hemorrhage.44 However, their use may be justified in populations with a high risk for development of malignant glioma, such as in patients with LGGs, given their extremely high risk for progression to HGGs. Indeed, the use of celecoxib has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Adminstration (FDA) for the prevention of colon cancer in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. In HGG patients, the use of COX-2 inhibitors has been investigated in combination with retinoids,45 chemotherapy,46 and irinotecan,47 regimens that were well-tolerated. Although these studies show only modest therapeutic activity in HGG patients, their results provide a basis on which to evaluate the use of COX-2 inhibitors in patients with LGGs, especially in combination with active immunotherapy approaches, such as vaccines, as discussed in more detail in the following section.

Perspective

We next aim to identify new genetic risk and prognostic factors that are supported by an in-depth understanding of their biological mechanisms gained through bench and clinical studies conducted in parallel. Such discoveries could lead to the development and rapid translation of more proactive and personalized treatments (e.g., prophylactic vaccines and/or use of NSAIDs in high-risk populations and/or patients). Further, this work could advance understanding of the immune-response characteristics of specific patient groups (e.g., patients with the AC-genotype in the SNP rs12553612 may have suboptimal IFN-α responses), thus allowing selection of more appropriate treatment options for each patient.

Although we still know very little about glioma risk factors, as discussed earlier, we have identified patients with WHO grade II LGGs as a population with a premalignant condition at extremely high risk (>50%) for recurrence as HGGs,11,12,48,49 and in whom we can test novel preventive therapeutics. Immunotherapeutic modalities, such as vaccines, may offer safe and effective treatment options for these patients due to the slower growth rate of LGGs (in contrast to HGGs), which should allow sufficient time for multiple immunizations, and hence high levels of anti-glioma immunity. Because patients with LGGs are likely not to be as immuno-compromised as patients with HGGs, they may exhibit greater immunological response to and benefit from the vaccines. Further, the generally mild toxicity of vaccines may help maintain a higher quality of life than is experienced with current cancer therapy. Indeed, based on encouraging data from a phase I vaccine trial targeting multiple glioma-associated antigen (GAA) epitopes in patients with recurrent HGGs,50 we initiated a pilot study of subcutaneous vaccinations with synthetic peptides for GAA epitopes emulsified in Montanide-ISA-51 every three weeks for eight courses as well as intramuscular administration of poly-ICLC51,52 in human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2+ patients with LGGs. Primary endpoints were safety and CD8+ T cell responses against vaccine-targeted GAAs, assessed by enzyme-linked immuno-SPOT (ELISPOT) assays. Treatment response was evaluated clinically and by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). GAAs for these peptides are IL-13Rα2,53,54 EphA2,55 Wilms’ tumor gene product 1 (WT1),56,57 and Survivin.58,59 As these GAAs are expressed in both LGGs and HGGs,55,57,58,60–63 the regimen used in our pilot study offers both immunotherapeutic and immunoprophylactic potential to reduce the risk of tumor recurrence. Therapeutically, this approach could suppress the expansion of indolently growing neoplastic LGG cells. Prophylactically, it could prevent the growth of glioma cells that undergo anaplastic transformation. A pan-HLA-DR tetanus toxoid peptide (TetA830) was included to enhance the general helper CD4+ T cell response. To date, 23 patients have been enrolled, and no dose-limiting toxicity has been encountered, except for one case with Grade 3 fever. The preliminary results demonstrate that the regimen in these patients is well tolerated and induces a robust type-1 anti-GAA T cell response. As the time course for LGG patients to recur with HGGs is highly variable and can exceed 10 years, typical funding mechanisms do not support the conclusive evaluation of the efficacy of preventing an LGG to HGG transition. However, due to the challenge of evaluating clinical responses in LGG patients, biomarkers of LGGs are actively being sought. For example, mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenases 1 and 2 (IDH1 and IDH2) have been shown to be present in most LGGs,64 and are associated with the accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate (2HG) in the tumor, which can be assessed quantitatively by magnetic resonance spectroscopy,65 and may thus prove to be a valuable diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in the near future. We will actively incorporate newly available biomarkers that can accurately predict disease progression or recurrence in our future studies. Furthermore, the ultimate success of our vaccine approach will benefit from the blockade of immunosuppressing mechanisms, such as IMCs and MDSCs. It is intriguing to evaluate whether modulation of myeloid cells by clinically available agents, such as celecoxib, will potentiate the effects of glioma vaccines, thereby inhibiting the progression of LGG to HGG.

The studies discussed above provide unique and privileged opportunities for cooperative synergy and the real-time exchange of data from epidemiologic studies to animal and human studies. In particular, our collective research, conducted in parallel and collaboratively, has identified a critical role for inflammation-mediators, such as myeloid cells, in glioma development. These data30,38,39 demonstrate how epidemiology studies can be driven by preclinical data in highly clinically relevant mouse models (biology-driven epidemiology), and how molecular biology can validate epidemiological findings and delineate the underlying novel mechanisms that could inform the development of therapeutic and/or preventive strategies (epidemiology-driven biology).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants from the National Institutes of Health (K07CA131505, R01CA119215, R01CA070917, R01NS055140, P01NS40923, P01CA132714, and U24AI082673) and the Musella Foundation for Brain Tumor Research and Information. The authors thank Michelle L. Kienholz for her critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

Hideho Okada is an inventor of the HLA-A2–binding CTL epitope peptide derived from IL-13Rα2, which has been exclusively licensed to Stemline Therapeutics, Inc. (US Application Serial # 11/231,618), and also serves on the Advisory Board of Stemline Therapeutics, Inc. Hideho Okada has completed all COI management plans according to University of Pittsburgh COI policies. Data related to the use of this invention were not evaluated or interpreted by Hideho Okada alone, but by the entire research team collaboratively.

References

- 1.CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2004–2008, Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karim AB, Maat B, Hatlevoll R, et al. A randomized trial on dose-response in radiation therapy of low-grade cerebral glioma: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Study 22844. Int.J.Radiat.Oncol Biol.Phys. 1996;36:549–556. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van den Bent MJ, Afra D, De WO, et al. Long-term efficacy of early versus delayed radiotherapy for low-grade astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma in adults: the EORTC 22845 randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366:985–990. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karim AB, Afra D, Cornu P, et al. Randomized trial on the efficacy of radiotherapy for cerebral low-grade glioma in the adult: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Study 22845 with the Medical Research Council study BRO4: an interim analysis. Int.J.Radiat.Oncol Biol.Phys. 2002;52:316–324. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw E, Arusell R, Scheithauer B, et al. Prospective randomized trial of low- versus high-dose radiation therapy in adults with supratentorial low-grade glioma: initial report of a North Central Cancer Treatment Group/Radiation Therapy Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. J.Clin.Oncol. 2002;20:2267–2276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw EG, Berkey B, Coons SW, et al. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Protocol 9802: Radiation Therapy Alone Versus RT + PCV Chemotherapy in Adult Low Grade Glioma. Neuro-Oncol. 2006;8:489. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw EG, Berkey B, Coons SW, et al. Update of an RTOG Prospective Study of Observation in Completely Resected Adult Low-Grade Glioma. Neuro-Oncol. 2006;8:452. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papagikos MA, Shaw EG, Stieber VW. Lessons learned from randomised clinical trials in adult low grade glioma. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:240–244. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pignatti F, van den BM, Curran D, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in adult patients with cerebral low-grade glioma. J.Clin.Oncol. 2002;20:2076–2084. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw EG, Berkey B, Coons SW, et al. Recurrence following neurosurgeon-determined gross total resection of adult supratentorial low-grade glioma: Results of a prospective clinical trial. J Neurosurg. 2008;109:835–841. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/109/11/0835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown PD, Shaw EG, Gunderson LL, et al. Clinical Radiation Oncology. Philadelphia PA: Churchill-Livingstone; 2006. Low-Grade Gliomas; pp. 493–514. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanai N, Chang S, Berger MS. Low-grade gliomas in adults. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2011;115:948–965. doi: 10.3171/2011.7.JNS101238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher JL, Schwartzbaum JA, Wrensch M, et al. Epidemiology of brain tumors. Neurol.Clin. 2007;25:867–890. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2007.07.002. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartzbaum JA, Huang K, Lawler S, et al. Allergy and inflammatory transcriptome is predominantly negatively correlated with CD133 expression in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology. 2010;12:320–327. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartzbaum JA, Ahlbom A, Lonn S, et al. An international case-control study of interleukin-4Ralpha, interleukin-13, and cyclooxygenase-2 polymorphisms and glioblastoma risk. Cancer Epidemiol.Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2448–2454. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartzbaum J, Ahlbom A, Malmer B, et al. Polymorphisms associated with asthma are inversely related to glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6459–6465. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sivak-Sears NR, Schwartzbaum JA, Miike R, et al. Case-control study of use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and glioblastoma multiforme. Am. J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1131–1139. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarthy BJ, Rankin KM, Aldape K, et al. Risk factors for oligodendroglial tumors: A pooled international study. Neuro-Oncology. 2011;13:242–250. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoemaker MJ, Swerdlow AJ, Hepworth SJ, et al. History of allergies and risk of glioma in adults. Int.J Cancer. 2006;119:2165–2172. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brenner AV, Butler MA, Wang SS, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in selected cytokine genes and risk of adult glioma. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2543–2547. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brenner AV, Linet MS, Fine HA, et al. History of allergies and autoimmune diseases and risk of brain tumors in adults. Int.J Cancer. 2002;99:252–259. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linos E, Raine T, Alonso A, et al. Atopy and Risk of Brain Tumors: A Meta-analysis. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2007;99:1544–1550. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiemels JL, Wiencke JK, Kelsey KT, et al. Allergy-related polymorphisms influence glioma status and serum IgE levels. Cancer Epidemiol.Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1229–1235. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiemels JL, Wiencke JK, Sison JD, et al. History of allergies among adults with glioma and controls. Int.J Cancer. 2002;98:609–615. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wrensch M, Wiencke JK, Wiemels J, et al. Serum IgE, tumor epidermal growth factor receptor expression, and inherited polymorphisms associated with glioma survival. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4531–4541. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartzbaum JA, Fisher JL, Aldape KD, et al. Epidemiology and molecular pathology of glioma. Nat Clin Pract Neuro. 2006;2:494–503. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheurer ME, Amirian E, Cao Y, et al. Polymorphisms in the interleukin-4 receptor gene are associated with better survival in patients with glioblastoma. Clin.Cancer Res. 2008;14:6640–6646. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheurer ME, Amirian ES, Davlin SL, et al. Effects of antihistamine and anti-inflammatory medication use on risk of specific glioma histologies. International Journal of Cancer. 2011;129:2290–2296. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheurer ME, El-Zein R, Thompson PA, et al. Long-term anti-inflammatory and antihistamine medication use and adult glioma risk. Cancer Epidemiol.Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1277–1281. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujita M, Scheurer ME, Decker SA, et al. Role of Type 1 IFNs in Antiglioma Immunosurveillance—Using Mouse Studies to Guide Examination of Novel Prognostic Markers in Humans. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16:3409–3419. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartzbaum JA, Xiao Y, Liu Y, et al. Inherited variation in immune genes and pathways and glioblastoma risk. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1770–1777. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amirian E, Liu Y, Scheurer ME, et al. Genetic variants in inflammation pathway genes and asthma in glioma susceptibility. Neuro-Oncology. 2010;12:444–452. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakahara N, Pollack IF, Storkus WJ, et al. Effective induction of antiglioma cytotoxic T cells by coadministration of interferon-beta gene vector and dendritic cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2003;10:549–558. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsugawa T, Kuwashima N, Sato H, et al. Sequential delivery of interferon- gene and DCs to intracranial gliomas promotes an effective anti-tumor response. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1551–1558. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuwashima N, Nishimura F, Eguchi J, et al. Delivery of Dendritic Cells Engineered to Secrete IFN-{alpha} into Central Nervous System Tumors Enhances the Efficacy of Peripheral Tumor Cell Vaccines: Dependence on Apoptotic Pathways. J.Immunol. 2005;175:2730–2740. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishimura F, Dusak JE, Eguchi J, et al. Adoptive transfer of Type 1 CTL mediates effective anti-central nervous system tumor response: critical roles of IFN-inducible protein-10. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4478–4487. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiesner SM, Decker SA, Larson JD, et al. De novo induction of genetically engineered brain tumors in mice using plasmid DNA. Cancer Res. 2009;69:431–439. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kohanbash G, Ishikawa E, Fujita M, et al. Differential activity of interferon-α8 promoter is regulated by Oct-1 and a SNP that dictates prognosis of glioma. OncoImmunology. 2012;1:487–492. doi: 10.4161/onci.19964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujita M, Kohanbash G, Fellows-Mayle W, et al. COX-2 blockade suppresses gliomagenesis by inhibiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2664–2674. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sinha P, Clements VK, Fulton AM, et al. Prostaglandin E2 promotes tumor progression by inducing myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4507–4513. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ochoa AC, Zea AH, Hernandez C, et al. Arginase, prostaglandins, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma. Clin.Cancer Res. 2007;13:721s–726s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodriguez PC, Ochoa AC. Arginine regulation by myeloid derived suppressor cells and tolerance in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:180–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solomon SD, Wittes J, Finn PV, et al. Cardiovascular risk of celecoxib in 6 randomized placebo-controlled trials: the cross trial safety analysis. Circulation. 2008;117:2104–2113. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.764530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fidler MJ, Argiris A, Patel JD, et al. The potential predictive value of cyclooxygenase-2 expression and increased risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with erlotinib and celecoxib. Clin.Cancer Res. 2008;14:2088–2094. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giglio P, Levin V. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in glioma therapy. J Ther. 2004;11:141–143. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hau P, Kunz-Schughart L, Bogdahn U, et al. Low-dose chemotherapy in combination with COX-2 inhibitors and PPAR-gamma agonists in recurrent high-grade gliomas - a phase II study. Oncology. 2007;73:21–25. doi: 10.1159/000120028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reardon DA, Quinn JA, Vredenburgh J, et al. Phase II trial of irinotecan plus celecoxib in adults with recurrent malignant glioma. Cancer. 2005;103:329–338. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baumert BG, Stupp R. Low-grade glioma: a challenge in therapeutic options: the role of radiotherapy. Annals of Oncology. 2008;19:vii217–vii222. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ashby LS, Shapiro WR. Low-grade Glioma: Supratentorial Astrocytoma, Oligodendroglioma, and Oligoastrocytoma in Adults. Curr.Neurol.Neurosci.Rep. 2004;4:211–217. doi: 10.1007/s11910-004-0041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okada H, Kalinski P, Ueda R, et al. Induction of CD8+ T-Cell Responses Against Novel Glioma-Associated Antigen Peptides and Clinical Activity by Vaccinations With {alpha}-Type 1 Polarized Dendritic Cells and Polyinosinic-Polycytidylic Acid Stabilized by Lysine and Carboxymethylcellulose in Patients With Recurrent Malignant Glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:330–336. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.7744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu X, Fallert-Junecko B, Fujita M, et al. Poly-ICLC promotes the infiltration of effector T cells into intracranial gliomas via induction of CXCL10 in IFN-α and IFN-γ dependent manners. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2010;59:1401–1409. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0876-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu X, Nishimura F, Sasaki K, et al. Toll like receptor-3 ligand poly-ICLC promotes the efficacy of peripheral vaccinations with tumor antigen-derived peptide epitopes in murine CNS tumor models. J.Transl.Med. 2007;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eguchi J, Hatano M, Nishimura F, et al. Identification of interleukin-13 receptor alpha2 peptide analogues capable of inducing improved antiglioma CTL responses. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5883–5891. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Okano F, Storkus WJ, Chambers WH, et al. Identification of a novel HLA-A*0201 restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope in a human glioma associated antigen, interleukin-13 receptor 2 chain. Clin.Cancer Res. 2002;8:2851–2855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hatano M, Eguchi J, Tatsumi T, et al. EphA2 as a Glioma-Associated Antigen: A Novel Target for Glioma Vaccines. Neoplasia. 2005;7:717–722. doi: 10.1593/neo.05277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Al Qudaihi G, Lehe C, Negash M, et al. Enhancement of lytic activity of leukemic cells by CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes generated against a WT1 peptide analogue. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2009;50:260–269. doi: 10.1080/10428190802578478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakahara Y, Okamoto H, Mineta T, et al. Expression of the Wilms' tumor gene product WT1 in glioblastomas and medulloblastomas. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2004;21:113–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02482185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Uematsu M, Ohsawa I, Aokage T, et al. Prognostic significance of the immunohistochemical index of survivin in glioma: a comparative study with the MIB-1 index. J.Neurooncol. 2005;72:231–238. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-2353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andersen MH, Pedersen LO, Becker JC, et al. Identification of a cytotoxic T lymphocyte response to the apoptosis inhibitor protein survivin in cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2001;61:869–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ciesielski M, Kozbor D, Castanaro C, et al. Therapeutic effect of a T helper cell supported CTL response induced by a survivin peptide vaccine against murine cerebral glioma. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2008;57:1827–1835. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0510-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Debinski W, Gibo DM. Molecular expression analysis of restrictive receptor for interleukin 13, a brain tumor-associated cancer/testis antigen. Mol.Med. 2000;6:440–449. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Debinski W, Gibo DM, Hulet SW, et al. Receptor for interleukin 13 is a marker and therapeutic target for human high-grade gliomas. Clin.Cancer Res. 1999;5:985–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wykosky J, Gibo DM, Stanton C, et al. EphA2 as a novel molecular marker and target in glioblastoma multiforme. Mol.Cancer Res. 2005;3:541–551. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 Mutations in Gliomas. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360:765–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi C, Ganji SK, DeBerardinis RJ, et al. 2-hydroxyglutarate detection by magnetic resonance spectroscopy in IDH-mutated patients with gliomas. Nat Med. 2012;18:624–629. doi: 10.1038/nm.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]