Abstract

Introduction

In a cytological analysis of endometriotic lesions neither granulocytes nor cytotoxic T-cells appear in an appreciable number. Based on this observation we aimed to know, whether programmed cell death plays an essential role in the destruction of dystopic endometrium. Disturbances of the physiological mechanisms of apoptosis, a persistence of endometrial tissue could explain the disease. Another aspect of this consideration is the proliferation competence of the dystopic mucous membrane.

Methods

Endometriotic lesions of 15 patients were examined through a combined measurement of apoptosis activity with the TUNEL technique (terminal deoxyribosyltransferase mediated dUTP Nick End Labeling) and the proliferation activity (with the help of the Ki-67-Antigens using the monoclonal antibody Ki-S5).

Results

Twelve out of 15 women studied showed a positive apoptotic activity of 3-47% with a proliferation activity of 2-25% of epithelial cells. Therefore we concluded that the persistence of dystopic endometrium requires proliferative epithelial cells from middle to lower endometrial layers.

Conclusion

A dystopia misalignment of the epithelia of the upper layers of the functionalism can be rapidly eliminated by apoptotic procedures.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Endometriosis, TUNEL Assay

Introduction

Endometriosis is a multifactorial complex disease characterized by the ectopic presence of endometrial glands and stroma. It can be presented as peritoneal disease, endometriotic ovarian cysts, and/or deeply infiltrating rectovaginal endometriosis and is associated with pelvic pain, adhesion formation, and infertility. Endometriosis occurs in 30%–40% of women with infertility and is a progressive disease in 40%–50% of reproductive-aged women (Sampson 1921; Halme et al. 1984; Agic et al. 2009).

The theory that has gained most supportive evidence for the pathogenesis of endometriosis is Sampson’s theory (Sampson 1921) of retrograde menstruation. Retrograde menstruation has been reported in 83% of baboons and in 70%–90% of women with spontaneous endometriosis (Blumenkrantz et al. 1981; D`Hooghe et al. 1996). The existence of endometrial cells in the peritoneal fluid has been reported in 59%–79% of women during menses or during the early follicular phase (Koninckx et al. 1980; Kruitwagen et al. 1991). According to Sampson’s hypothesis (Sampson 1921), menstrual debris, refluxed into the peritoneal cavity, contains viable endometrial cells that can implant and develop into endometriotic lesions (Cleophas et al. 2006).

Halme (1989) and other investigators have shown that macrophages present in the peritoneal cavity are potent producers of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6 and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Bauer et al. 1989; Cleophas et al. 2006; Harada et al. 1997; Mettler et al. 2004; Riese et al. 2004; Salmassi et al. 2008; Surrey and Halme 1990). They also have suggested that growth factors are involved in the control of implantation and the growth of endometrial cells outside the uterus.

Recent studies have suggested that abnormalities in the regulation of specific genes are involved in the development and in the pathogenesis of endometriosis (Kao et al. 2003; Mettler et al. 2007; Ota et al. 2000; Sharpe- Timms et al. 1998; Tsudo et al. 2000).

Endometrium is divided into the superficialis or functionalis layer, which undergoes cyclic shedding, and the basalis layer, which is permanent. Endometrial tissue from the functionalis is subjected to a proliferative process highly regulated by hormones throughout the menstrual cycle. At the time of menstruation, it becomes necrotic and hypoxic and is shed. In addition, apoptosis seems to be an important biologic process involved in the cyclic remodelling of the endometrium (Be`liard et al. 2004; Hopwood and Levison 1976). It is well known that menstrual fragments are composed of both necrotic and living cells (Keetel and Stein 1951; Bartosik et al. 1986)

Cytologically endometriosis lesions show few granulocytes and cytotoxic T cells. Due to this observation, we posed the question of whether programmed cell death processes with a regular destruction of the dystopian endometrium plays an essential role in this disease. Disturbances of these physiological apoptosis mechanisms could induce the persistence of the endometrial tissue and support endometriosis. Another aspect of this consideration is the proliferation competence of the dystopic mucous membrane. While the upper functional layers have no significant proliferative activity, epithelial cells from deeper endometrial layers show a considerable ability to proliferate. In order to analyze quantitatively these relationships in 15 endoscopic excised endometriosis nodules, the frequency of the apoptotic mucosa membrane epithelia cells were determined with the help of the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labelling (TUNEL) technology in this study.

The proliferation activity was determined with help of the Ki-67-Antigens under employment of the monoclonal antibody Ki-S5. This protein is expressed in all cell cycle phases S, G2, M and G1, but not in G0 (Kreipe et al. 1993; Rudolph et al. 1993; Salmassi et al. 2000).

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

Samples of ectopic endometrium (endometriosis, n = 15) and eutopic endometrium (n=3) were obtained from patients undergoing laparoscopy for the treatment of endometrioma and diagnostic hysteroscopy, respectively.

The patients ranged in age from 25-40 years and none of them received hormonal treatment prior to their surgery. For the investigation of apoptosis and proliferation, these samples were processed as follows:

-

Cryostat sections were prepared and stained with hematoxilin-eosin.

Eectopicendometrium were subjected to histopathological assessment which confirmed their site of origin, i.e. proliferative endometrium and endometrioma cyst wall, respectively.

The tissue samples were placed in a fresh 4% paraformaldehyde solution in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4. To provoke a homogenous coloring, larger tissue samples were cut into smaller pieces with a sterile scalpel. The specimens were shaken on ice for 20 hours, then embedded in paraffin and stored at –20°C until further examination.

Apoptosis (TUNEL technique)

Apoptosis was assessed with the principle of terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labelling (TUNEL) to detect fragmented DNA in apoptotic cells.

Sections were treated according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (OncorApop Tag, Heidelberg) by the methods of Gavrieli et al. (1992), Labat-Moleur et al. (1998) and Negoescu et al. (1996). Briefly, sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, permeabilized in proteinase K, and treated with terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase incubation buffer at 37°C for 60 minutes. Sections were then treated with peroxidase-labeledantidigoxigenin antibody, followed by 3`-3 diaminobenzidinecolor reaction. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Immunohistochemical detection of Ki-67 antigen

Paraffin cuts of the endometriosis samples were deparaffined with xylene and rehydrated with decreasing ethanol concentrations of 100-70%. The unmasking of the epitopes was carried out by boiling the sections in a steam pressure pot for 2.5 min in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6) according to the methods from Shi et al. 1991 and Kreipe et al. 1993.

The deparaffined sections were incubated 45 min at RT, incubated in a moist chamber with the monoclonal antibody Ki-S5. After washing four times with a Tris buffer (pH 7.5), the sections incubated with 1:20 diluted rabbit anti-mouse antibody (Z259, DAKO, Hamburg) in 10% human serum albumin in Tris buffer (TBS) for 30 min. They were then washed 4x in TBS and incubated with alkaline phosphatise anti alkaline phosphatise (APAAP) complex at a dilution of 1:50 in TBS (DAKO, Hamburg, D0651) for 30 min. After washing four times with TBS, the development of the Ki-67 positive nuclei was occurred, by a new fuchsin-diazo-color reaction. Then, a nuclear counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin.

Results

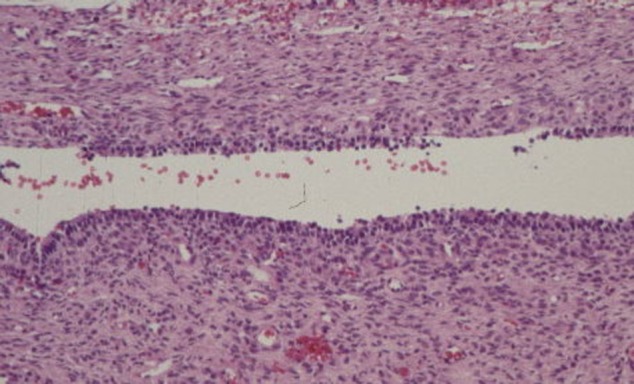

Figure 1 shows a histological (HE staining) image of an endometriosis lesion from a 32 years old patient who was on her 8th cycle day. The subepithelialstroma tissue contains hardly neutrophil granulocytes or lymphocytes.

Fig. 1 .

Histological representation of an endometriosis lesion (HE staining).

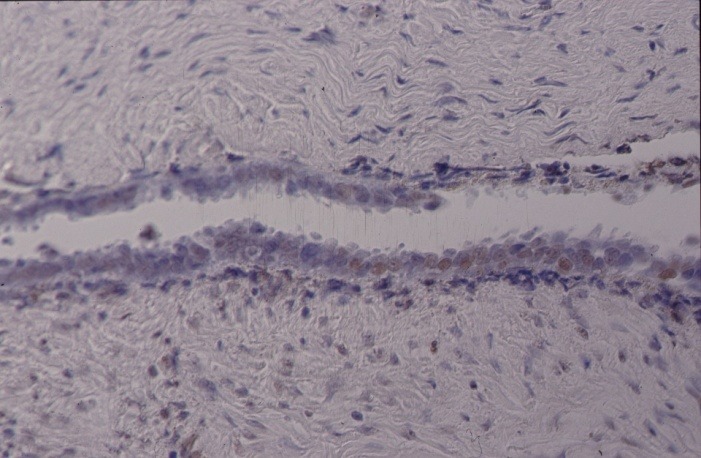

Detection of apoptosis in paraffin sections by the TUNEL technique:

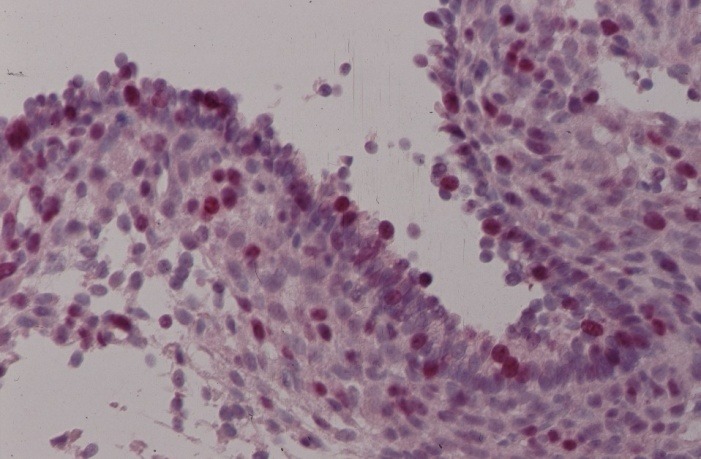

With TUNEL technology apoptotic cells can be observed. The brown staining in Figure 2A and B shows apoptosis in epithelial cell nuclei of endometriosis lesions from 27 and 32 years old patients.

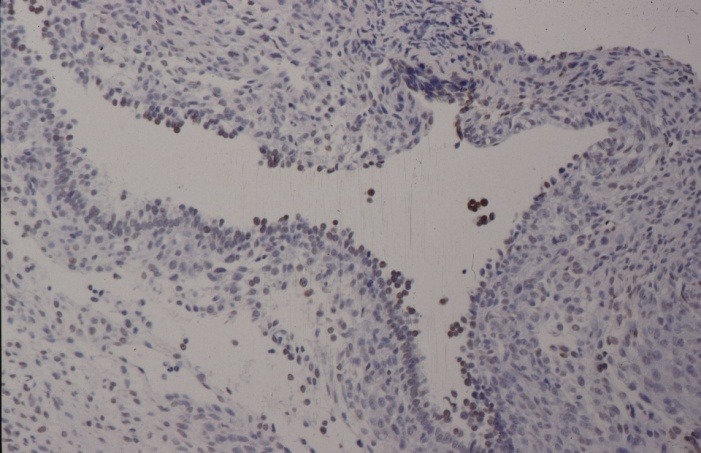

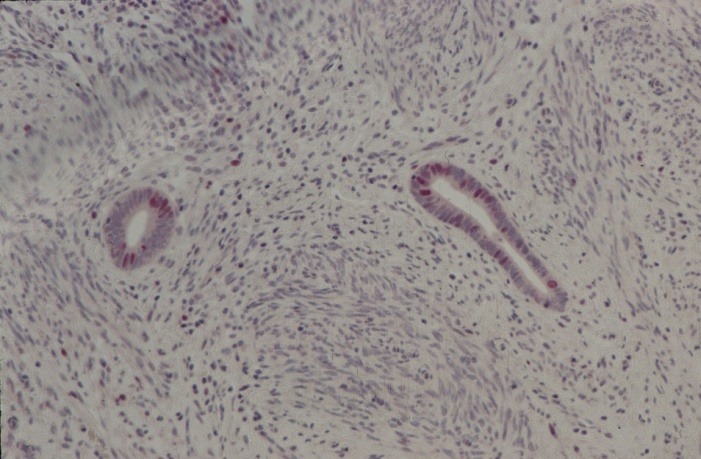

Immunohistochemical detection of the proliferation marker Ki-S5-antigen:

With proliferation markers, which recognize the Ki-67-Antigen by Ki-S5-Antibody, proliferating cells which are in the cycle could be selectively represented. The red staining of epithelial cell nuclei in Figure 3a and b shows the proliferation of endometrial lesions of 27 and 32 years old patients.

Table 1 shows the frequency of apoptotic and proliferated epithelial cells in endometriosis and normal Endometrium.

Table 1. The frequency of apoptotic and proliferated epithelial cells in endometriosis and normal Endometrium.

| Apoptosis | Proliferation | |

| Endometriosis (n=15) Frequency | 12/15 (+) 3-47% | 13/15 (+) 2-25% |

| Endometrium (n=3) Frequency | 1% | 26% |

Fig. 2. Detection of fragmented DNA in apoptotic cells by using terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labelling technique. The brown coloration of cell nuclei characterized the apoptotic cells in ectopic endometrium from 27 (A) and 32 (B) years old patients.

a.

b.

Discussion

Endometriosis cases, examined in this study, concern female patients who suffer a chronic Endometrioses. I.e., here it concerned the women who cannot eliminate regularly and effectively the dystopia Endometrium mucosa. The investigations show that the proliferation activity was simultaneously accompanied by an apoptosis activity. Possibly the procedures of proliferation and Apoptosis go hand in hand, so that none of the mechanisms is able to win the prevailing. Endometriosis persists without increasing actively in size. Accordingly the apoptotic activity remains high, while the Endometrioses lesions cannot be eliminated completely.

Watanabe et al. (Watanabe et al. 1997) and some other authors (Agic et al. 2009; El-Ghobashy et al. 2007; Harada et al. 1996; Jones et al. 1998; McLaren et al. 1997; Meresman et al. 2000; Suganuma et al.1997) were consistent with our results and found the Bcl2 and Fas expression in eutopic and ectopic human endometrium. The results also allow as a conclusion that any significant disruption of the apoptotic ability, such as point mutation, in the pro-apoptotic genes with 'loss of function' cannot be counted. In consideration of the relatively high frequency of apoptosis might the persistence of the dystopian mucous membrane led back often remarkable proliferative capacity of dystopian epithelia. On the other hand it is known that the upper functional layers of the endometrium do not exhibit proliferations' activity, because they have short telomeres and telomerase activity cannot develop. In comparison, epithelial cells of the deeper layers because of the high telomerase activity have a sufficiently extended telomere length in order to develop a higher proliferative activity (Kyo et al. 1999; Tanaka et al. 1998; Yokoyama et al. 1998).

Fig. 3. Immunohistochemical presentation of proliferating epithelial cells with the monoclonal Ki-S5-Antibody (red staining of nuclei) using alkaline phosphatase anti-alkaline phosphatase (APAAP) reaction. 4µm cryostat section ectopic endometrium: (A) for a 27 years old female patient and (B) for a 32 years old patient.

A.

B.

Conclusion

The results suggest the following hypothesis inaugurate endometriosis development:

Under the dystopian endometrial mucous membrane particles found solely surface epithelium, prevail apoptosis and dystopia tissue rapidly eliminated. Dystopian endometrium particles contain also epithelia from deeper layers, so proliferative processes of the apoptotic activity can counteract. The dystopia endometrium persisted and becomes the basis of Adenoma, proliferative endometriosis disease.

Ethical Issues

None to be declared.

Conflict of interests

Authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Agic A, Djalali S, Diedrich K and Hornung D . 2009 Apoptosis in Endometriosis. GynecolObstet Invest, 68, 217-223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartosik D, Jacobs SL and Kelly LJ . Endometrial tissue in peritoneal fluid 1986FertilSteril, 46, 796–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer J, Bauer TM, Kalb T, Taga T, Lengyel G and T. Hirano et al. 1989. Regulation of interleukin 6 receptor expression in human monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. Comparison with the expression in human hepatocytes, J Exp Med, 170 , 1537–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Be´liard A, Noe¨ A and Foidart JM . 2004Reduction of apoptosis and proliferation inEndometriosis. Fertil and Steril, 82(1), 80-85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenkrantz MJ, Gallaagher N, Bashore RA and Tenckhoff H . 1981 Retrograde menstruation in women undergoing chronic peritoneal dialysis. Obstet Gynecol, 142, 890-895 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleophas M, Kyama M, Overbergh L, Debrock S, Valckxc D, Vander Perrea S, Meuleman C, Mihalyi M, Mwenda JM, Mathieu C and D’Hooghe TM . 2006Increased peritoneal and endometrial gene expression of biologically relevant cytokines and growth factors during the menstrual phase in women with endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility, 85(6), 1667-1675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Hooghe TM, Bambra CS, Raeymaekers BM and Koninckx PR . 1996 Increased incidence and recurrence of retrograde menstruation in baboons with spontaneous endometriosis. Hum Reprod, 11, 2022-2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ghobashy AA, Shaaban AM, Innes J, Prime W, Herrington CS . 2007 Differential expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and apoptosis-related proteins in endocervical lesions. Eur J Cancer, 43, 2011-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrieli Y, Sherman Y and Ben-Sasson SA . 1992 Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J Cell Biol, 119(3), 493-501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halme J, Hammond MG, Hulka JF, Raj S and Talbert LM . 1984 Increased activation of pelvic macrophages in infertile women with endometriosis . ObstetGynecol, 64, 151-154 [Google Scholar]

- Halme J . 1989 Release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha by human peritoneal macrophages in vivo and in vitro. Am J ObstetGynecol, 161, 1718-1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada M, Suganuma N, Furuhashi M, Nagasaka T, Nakashima N, Kikkawa F, Tomoda Y and Furui K . 1996 Detection of apoptosis in human endometriotic tissues. Mol Hum Reprod, 2(5), 307-315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada T, Yoshioka H, Yoshida S, Iwabe T, Onohara Y and Tanikawa M . 1997 Increased interleukin-6 levels in peritoneal fluid of infertile patients with active endometriosis. Am J ObstetGynecol, 176, 593-597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood D and Levison DA . Atrophy and apoptosis in the cyclical humanendometrium. 1976J Pathol, 119, 159-166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RK, Searle RF and Bulmer JN . 1998 Apoptosis and bcl-2 expression in normal human endometrium, endometriosis and adenomyosis. Hum Reprod, 13(12), 3496-3502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao LC, Germeyer A, Tulac S, Lobo S, Yang JP, Taylor RN, Osteen K, Lessey BA and Giudice LC . 2003 Expression Profiling of Endometrium from Women with Endometriosis Reveals Candidate Genes for Disease-Based Implantation Failure and Infertility. Endocrinology, 144, 2870-2881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keetel WC and Stein RJ . The viability of the cast-off menstrual endometrium . 1951Am J ObstetGynecol, 61, 440-442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koninckx PR, De Moor and Brosens IA . 1980 Diagnosis of the luteinized unruptured follicle syndrome by steroid hormone assays on peritoneal fluid. Br J ObstetGynaecol, 87, 929-934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreipe H, Wacker HH, Heidebrecht HJ, Haas K, Hauberg M, Tiemann M and Parwaresch R . 1993Determination of the growth fraction in non-Hodgkin's lymphomas by monoclonal antibody Ki-S5 directed against a formalin-resistant epitope of the Ki-67 antigen. Am J Pathol, 142(6), 1689-1694 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruitwagen RF, Poels LG, Willemsen WN, de Ronde IJ, Jap PH and Roll R . 1991 Endometrial epithelial cells in peritoneal fluid during the early follicular phase. FertilSteril, 55, 297-303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyo S, Kanaya T, Takakura M, Tanaka M and Inoue M . 1999 Human telomerase reverse transcriptase as a critical determinant of telomerase activity in normal and malignant endometrial tissues. Int J Cancer, 80(1), 60-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labat-Moleur F, Guillermet C, Lorimier P, Robert C, Lantuejoul S, Brambilla E and Negoescu A . 1998 TUNEL apoptotic cell detection in tissue sections: critical evaluation and improvement. J HistochemCytochem, 46(3), 327-334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren J, Prentice A, Charnock-Jones DS, Sharkey AM and Smith SK . 1997 Immunolocalization of the apoptosis regulating proteins Bcl-2 and Bax in human endometrium and isolated peritoneal fluid macrophages in endometriosis. Hum Reprod, 12(1), 146-152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meresman GF, Vighi S, Buquet RA, Contreras-Ortiz O, Tesone M andRumi LS. 2000Apoptosis and expression of Bcl-2 and Bax in eutopic endometrium from women with endometriosis. FertilSteril, 74, 760-766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mettler L, Schmutzler AG, Koch K, Schollmeyer T and Salmassi A . 2004 Identification of the M-CSF receptor in endometriosis by immunohistochemistry and RT-PCR. Am J ReprodImmunol, 52, 298-305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mettler L, Salmassi A, Schollmeyer T, Schmutzler AG, Püngel F and Jonat W . 2007Comparison of c-DNA microarray analysis of gene expression between eutopic endometrium and ectopic endometrium (endometriosis) . J Assist Reprod Genet, 24(6), 249-258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negoescu A, Lorimier P, Labat-Moleur F, Drouet C, Robert C, Guillermet C, Brambilla C and Brambilla E . 1996 In situ apoptotic cell labeling by the TUNEL method: improvement and evaluation on cell preparations. J HistochemCytochem, 44(9), 959-968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota H, Igarashi S, Kato N and Tanaka T . 2000 Aberrant expression of glutathione peroxidase in eutopic and ectopic endometrium in endometriosis and adenomyosis. FertilSteril, 74, 313-318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riese J, Niedobitek G, Lisner R, Jung A, Hohenberger W and Haupt W . 2004 Expression of interleukin-6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 by peritoneal sub-mesothelial cells during abdominal operations. J Pathol, 202, 34-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph P, Lappe T, Kreipe H, Parwaresch MR and Schmidt D. 1993. Determination of proliferation activity of prostate cancers by means of nuclear proliferation-associated formalin resistant Ki-S5 antigens, VerhDtschGesPathol, 77, 98-102. [PubMed]

- Salmassi A, Hauberg M, Koch K and Mettler L . 2000Apoptose-Resistenz bei Endometriose, pmi Verlag AG, Editor:L. Mettler, 144-152

- Salmassi A, Acil Y, Schmutzler AG, Koch K, Jonat W and Mettler L . 2008 Differential interleukin-6 messenger ribonucleic acid expression and its distribution pattern in eutopic and ectopic endometrium. FertilSteril, 89, 1578-1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson JA . 1921 Peritoneal endometriosis due to menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J ObstetGynecol , 14, 422-469 [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe-Timms K, Piva M, Ricke EA, Surewicz K, Zhang YL and Zimmer RL . 1998Endometriotic lesions synthesize and secrete a haptoglobin-like protein. BiolReprod, 58, 988-994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi SR, Key ME and Kalra KL . 1991 Antigen retrieval in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues: an enhancement method for immunohistochemical staining based on microwave oven heating of tissue sections. J HistochemCytochem, 39(6), 741-748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suganuma N, Harada M, Furuhashi M, Nawa A and Kikkawa F . 1997 Apoptosis in human endometrial and endometriotic tissues. Horm Res, 48Suppl 3, 42-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surrey ES and Halme J . 1990 Effect of peritoneal fluid from endometriosis patients on endometrial stromal cell proliferation in vitro. ObstetGynecol, 76, 792-797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Kyo S, Takakura M, Kanaya T, Sagawa T, Yamashita K, Okada Y, Hiyama E and Inoue M . 1998 Expression of telomerase activity in human endometrium is localized to epithelial glandular cells and regulated in a menstrual phase-dependent manner correlated with cell proliferation. Am J Pathol, 153(6), 1985-1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsudo T, Harada T, Iwabe T, Tanikawa M, Nagano Y, Ito M, Taniguchi F and Terakawa N . 2000 Altered gene expression and secretion of interleukin-6 in stromal cells derived from endometriotic tissues. Fertil Steril, 73, 205-211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama Y, Takahashi Y, Shinohara A, Lian Z, Xiaoyun W, Niwa K, de Rondeand Tamaya T . 1998 Telomerase activity is found in the epithelial cells but not in the stromal cells in human endometrial cell culture. Mol Hum Reprod, 4(10), 985-989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Kanzaki H, Narukawa S, Inoue T, Katsuragawa H, Kaneko Y and Mori T . 1997 Bcl-2 and Fas expression in eutopic and ectopic human endometrium during the menstrual cycle in relation to endometrial cell apoptosis. Am J ObstetGynecol, 176(2), 360-368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]