Abstract

Attachment theory provides a useful framework for predicting marital infidelity. However, most research has examined the association between attachment and infidelity in unmarried individuals, and we are aware of no research that has examined the role of partner attachment in predicting infidelity. In contrast to research showing that attachment anxiety is unrelated to infidelity among dating couples, 2 longitudinal studies of 207 newlywed marriages demonstrated that own and partner attachment anxiety interacted to predict marital infidelity, such that spouses were more likely to perpetrate infidelity when either they or their partner was high (vs. low) in attachment anxiety. Further, and also in contrast to research on dating couples, own attachment avoidance was unrelated to infidelity whereas partner attachment avoidance was negatively associated with infidelity indicating that spouses were less likely to perpetrate infidelity when their partner was high (vs. low) in attachment avoidance. These effects emerged controlling for marital satisfaction, sexual frequency, and personality, did not differ across husbands and wives, and did not differ across the two studies, with the exception that the negative association between partner attachment avoidance and own infidelity only emerged in one of the two studies. These findings offer a more complete understanding of the implications of attachment insecurity for marital infidelity and suggest that studies of unmarried individuals may not provide complete insights into the implications of various psychological traits and processes for marriage.

Keywords: Adult attachment, Infidelity, Marriage, Romantic relationships, Dating Relationships

Although marital relationships can be the source of some of life’s most enjoyable experiences, they are also the source of one of life’s most painful experiences—infidelity. Estimates suggest that over 25% of married men and 20% of married women engage in extra-marital sex over the course of their relationships (Atkins, Baucom, & Jacobson, 2001; Greeley, 1994; Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994; Wiederman, 1997). Such infidelities can have serious negative consequences for those involved. Not only may infidelity lead to relationship distress and thus decreased relationship satisfaction in both partners (Sănchez Sosa, Hernández Guzmán, & Romero, 1997; Spanier & Margolis, 1983), it is also a strong predictor of divorce (Amato & Rogers, 1997; Betzig, 1989). Further, the victims and perpetrators of infidelity also frequently experience negative intrapersonal outcomes, such as decreased self-esteem (Shackelford, 2001), increased risk of mental health problems (e.g., Allen et al., 2005; Cano & O’Leary, 2000), guilt (Spanier & Margolis, 1983), and depression (Beach, Jouriles, & O’Leary, 1985). Identifying psychological characteristics that may be associated with a risk of perpetrating infidelity may help interventions to better target such individuals.

Attachment theory (e.g., Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003) provides one useful framework for addressing this goal. According to that theory, intimates develop mental representations of the availability of close others that lead to strong cognitive and behavioral patterns of responding to those others. Whereas those who develop a secure attachment style tend to believe close others are available to them and behave accordingly, those who develop an insecure attachment style, i.e., attachment anxiety or attachment avoidance, tend to believe close others are less available to them and behave accordingly. Intimates who develop high levels of attachment anxiety are uncertain of the availability of close others and cope by seeking reassurance from and clinging to the partner (Brennan & Shaver, 1995; Feeney & Noller, 1990). Intimates who develop high levels of attachment avoidance, in contrast, doubt the availability of close others and cope by avoiding behaviors that promote intimacy (Brennan & Shaver, 1995; Campbell, Simpson, Kashy, & Rholes, 2001; Pistole, 1993; Simpson, Rholes, & Nelligan, 1992; Gentzler & Kerns, 2004).

Both types of insecurity may be associated with marital infidelity. Individuals high in attachment anxiety tend to feel that their needs for intimacy are not being met in their current relationships (for review, see Shaver & Mikulincer, in press) and use sex to meet their unmet needs (Birnbaum, Reis, Mikulincer, Gillath, & Orpaz, 2006). Accordingly, they may be more likely than individuals low in attachment anxiety to seek intimacy with another partner through infidelity. Individuals high in attachment avoidance tend to be chronically less committed to their relationships (DeWall et al., 2011) and have more permissive sexual attitudes (Brennan & Shaver, 1995; Gentzler & Kerns, 2004; Hazan, Zeifman, & Middleton, 1994). Given that both tendencies are associated with infidelity (Drigotas, Safstrom, & Gentilia, 1999; Smith, 1994), avoidantly-attached individuals may be more likely to engage in infidelity as well.

We are aware of three published reports describing a total of 10 studies that have addressed the role of attachment in predicting infidelity. DeWall and colleagues (2011) described eight studies indicating that attachment avoidance, but not attachment anxiety, was associated with (a) a greater interest in alternatives and/or (b) infidelity; Bogaert and Sadava (2002) demonstrated that attachment anxiety was positively associated with infidelity, particularly in women; and Allen and Baucom (2004) reported that (a) attachment avoidance was positively associated with the number of extra-dyadic partners reported by male undergraduates, (b) attachment anxiety was positively associated with the number of extra-dyadic partners reported by female undergraduates, and (c) attachment avoidance trended toward being associated with the number of extra-dyadic partners reported by married individuals.

Nevertheless, several qualities of these studies limit conclusions regarding the role of attachment insecurity in predicting infidelity in marriage. Most notably, although attachment processes may operate differently in marriage than in dating relationships, only 3 of the 10 studies involved a substantial number of married spouses. One way in which married partners differ from partners in dating relationships is that married partners tend to be more committed to their relationships (e.g., Stanley & Markman, 1992). Such differences may emerge because married partners are more likely to engage in behaviors that lead to greater commitment (e.g., make a public declaration of faithfulness, have children together, share financial obligations) (see Rusbult, 1980) and/or because greater levels of commitment lead to the decision to marry in the first place. Given that commitment to the relationship involves a transformation of motivation, whereby intimates focus less on their own self-interests, such as extra-dyadic sex, to benefit their relationships (Rusbult, Olsen, Davis, & Hannon, 2001), married individuals may be more motivated to abstain from infidelity in order to protect the relationship than are unmarried individuals. Indeed, more committed individuals are more likely to derogate attractive alternatives than are less committed individuals (e.g., Johnson & Rusbult, 1989; Lydon, Meana, Sepinwall, Richards, & Mayman, 1999; Miller & Maner, 2010). Accordingly, the psychological characteristics of those who commit infidelity in marriage may be different than the psychological characteristics of those who commit infidelity in dating relationships. Unfortunately, the three studies that examined the implications of attachment insecurity and infidelity among married people were inconclusive. DeWall and colleagues (2011) described one study (Study 6) that was comprised of both married community spouses and dating undergraduates and revealed a significant positive association between attachment avoidance and interest in alternative partners and no association between attachment anxiety and interest in alternative partners. However, (a) DeWall et al. did not report whether either association differed across married and dating couples and (b) interest in alternatives is not the same as infidelity, particularly in highly committed relationships like marriage. In contrast, Bogaert and Sadava (2002) reported a significant positive association between attachment anxiety and infidelity but no association between attachment avoidance and infidelity using a community sample of people who were in a committed relationship, engaged, or married. However, (a) Bogaert and Sadava did not report how many people were married versus unmarried or whether their results varied across married and unmarried people and (b) their infidelity variable did not distinguish between perpetrators of infidelity and the partners of such perpetrators. Finally, the positive association that Allen and Baucom (2004) reported between attachment avoidance and the number of extra-dyadic involvements in their sample of married participants did not reach statistical significance.

A second limitation of the existing research is that none of these studies controlled for numerous third variables that may explain the link between attachment and infidelity. For example, marital satisfaction is negatively associated with attachment insecurity (Feeney, Noller, & Callan, 1994; Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Klohnen & Bera, 1998) and infidelity (Glass & Wright, 1985; Wiggins & Lederer, 1984); yet satisfaction was not controlled in the studies reported by either Allen and Baucom (2004) or Bogaert and Sadava (2002). Further, attachment anxiety and avoidance are associated with variations in sexual frequency (Bogaert & Sadava, 2002), which in turn may be related to infidelity through its effects on marital and sexual satisfaction (Liu, 2000; Thompson, 1983). Yet, none of the studies controlled for sexual frequency. Finally, attachment insecurity is associated with various other individual differences in personality that are also associated with attachment and infidelity. For example, agreeableness is negatively associated with attachment insecurity (Shaver & Brennan, 1992) and low levels of agreeableness are associated with an increased likelihood of infidelity (Schmitt, 2004). Likewise, neuroticism is positively associated with attachment insecurity (Shaver & Brennan, 1992), and individuals who engage in infidelity are more likely to perceive higher levels of neuroticism in their partners (Orzeck & Lung, 2005). Additionally, attachment insecurity is negatively associated with conscientiousness, extraversion, and openness to experience (Mickelson, Kessler, & Shaver, 1997; Shaver & Brennan, 1992), traits that may be associated with infidelity as well. Nevertheless, none of the studies controlled for these other individual differences.

A third limitation of the existing research is that none of the studies examined the role of the partner’s attachment insecurity in predicting marital infidelity. The fact that anxiously-attached intimates tend to seek constant reassurance and cling to their partners may lead such partners to seek out alternative relationships. Indeed, individuals with anxiously-attached partners tend to report less commitment to their relationships (Simpson, 1990), which, as noted earlier, is positively associated with the likelihood of infidelity (Drigotas et al, 1999). Likewise, the fact that avoidantly-attached intimates tend to avoid behaviors that promote intimacy may lead their partners to seek intimacy in other relationships. Indeed, individuals with avoidantly-attached partners tend to view those partners as less caring and supportive (Kane et al., 2007), a response that is positively associated with the likelihood of infidelity (Barta & Kiene, 2005).

Finally, no studies have reported the interactive effects of own and partner attachment insecurity in predicting marital infidelity. Shoda and colleagues (Shoda, Tiernan, & Mischel, 2002; Zayas, Shoda, & Ayduk, 2002) proposed a cognitive-affective processing system whereby individual differences in one’s partner determine the effects of one’s own individual differences on interpersonal behavior. Accordingly, the extent to which one’s own attachment insecurity predicts infidelity may depend on one’s partner’s attachment insecurity. Several effects are possible. It may be that insecurity in either partner is enough to increase the likelihood of infidelity, such that spouses will demonstrate an increased likelihood of infidelity if either they or their partner are high in either form of attachment insecurity. Alternatively, it is possible that security in either partner is sufficient to decrease the likelihood of infidelity, such that spouses will only demonstrate an increased likelihood of infidelity if they and their partner are both high in attachment insecurity. Finally, the particular combinations of insecurity might matter, such that people high in attachment anxiety may be particularly likely to perpetrate infidelity if their partner is high in attachment avoidance or particularly unlikely to perpetrate infidelity if their partner is also high in attachment anxiety.

Overview of the current study

We used data from two extant longitudinal data sets to examine the role of attachment insecurity in predicting infidelity. These studies addressed the aforementioned limitations of previous studies in several ways. First, whereas previous research has examined infidelity in dating relationships, the current studies used two samples of newlywed couples to identify how attachment insecurity affects infidelity in marriage. Although newlyweds may tend to perpetrate infidelity less frequently on average, leading to a rather conservative test of our hypotheses, they may be more similar to people in dating relationships than are couples in more-established marriages on variables other than commitment (e.g., age, income), allowing us to more directly compare the effects of attachment on infidelity in marriage versus dating relationships. Second, given that third variables, such as personality, sexual frequency, and marital satisfaction, may account for the association between attachment and infidelity, the current studies controlled for these variables. Finally, given that both data sets contained reports from both members of the couple, they allowed us to examine the unaddressed role of partners’ attachment insecurity, both as a main effect and as a moderator of own attachment insecurity, in predicting own infidelity. Both studies used virtually identical methods and thus are described simultaneously.

We made the following predictions. Given that people high in anxious attachment may be more likely to have unmet needs for intimacy that they try to fulfill with extramarital sex, we predicted that attachment anxiety would be positively associated with engaging in infidelity. Additionally, given that avoidantly-attached individuals tend to be less committed to their relationships on average, which has been shown to predict infidelity in unmarried individuals, we also predicted that attachment avoidance would also be positively associated with engaging in infidelity. Finally, given that anxiously- and avoidantly-attached individuals tend to behave in ways that may lead their partners to seek out alternative relationships, we also predicted that partner attachment anxiety and partner attachment avoidance would also be positively associated with engaging in infidelity. We also conducted exploratory analyses to test the interactive effects of own and partner attachment on infidelity, but made no strong predictions regarding which of the numerous potential patterns would emerge.

Method

Participants

Participants in Study 1 were 72 newlywed couples recruited from northern Ohio; participants in Study 2 were 135 newlywed couples recruited from eastern Tennessee. All participants were recruited through advertisements placed in community newspapers and bridal shops and through invitations sent to eligible couples who had applied for marriage licenses in counties near the studies' locations. Couples who responded were screened in a telephone interview to ensure they met the following eligibility criteria: (a) They had been married for less than 6 months, (b) neither partner had been previously married, (c) they were at least 18 years of age, and (d) they spoke English and had completed at least 10 years of education (to ensure comprehension of the questionnaires). Additionally, Study 2 added the criteria that couples did not already have children and that wives were not older than 35 years (because a larger aim of Study 2 was to examine the transition to parenthood).

Husbands in Study 1 were 24.9 (SD = 4.4) years old and had completed 14.2 (SD = 2.5) years of education; husbands in Study 2 were 25.9 (SD = 4.6) years old and had completed 15.7 (SD = 2.4) years of education. Wives in Study 1 were 23.5 (SD = 3.8) years old and had completed 14.7 (SD = 2.2) years of education; wives in Study 2 were 24.2 (SD = 1.88) years old and had completed 15.9 (SD = 2.2) years of education. The median income, combined across spouses, was between $30K and $40K in each study. The majority of participants were Caucasian (> 90%; in Study 1, 4% were African American and 3% identified as "other"; in Study 2, 4% were African American, 2% were Asian, and 2% identified as "other").

Procedure

In both studies, participants were mailed a packet of questionnaires to complete at home and bring with them to a laboratory session where they completed a consent form approved by the local human subjects review board and participated in a variety of tasks beyond the scope of the current analyses. The packet contained self-report measures of attachment insecurity, marital satisfaction, frequency of sexual intercourse, and the Big Five personality traits. To ensure that participants felt comfortable disclosing sensitive information, we (a) instructed them to complete their questionnaires independently of one another and not to discuss the questionnaires with one another, (b) included separate sealable envelopes in which they were to place their completed questionnaires so their partners were not able to easily view their responses, and (c) informed them that we would not share their responses with their partners. Every 6 to 8 months subsequent to the initial assessment, participants were again mailed a packet of questionnaires that contained the same measures of sexual frequency and marital satisfaction, as well as a measure of infidelity. We again employed the same tactics to ensure that participants felt comfortable reporting sensitive information. These follow-up procedures were used six times and spanned the first 3.5 years of marriage in Study 1 and the first 4.5 years of marriage in Study 2. Participants in Study 1 were paid $60 and participants in Study 2 were paid $80 for participating in the first phase of data collection; participants in both studies were paid $50 for participating in each of the six subsequent phases, except for the sixth phase in Study 2 for which participants were paid $80 because it resembled the first phase. Fifty-two percent of participants completed six or more waves and 36% of participants completed all waves. Given that people who were less likely to complete all waves of data collection had fewer opportunities to report an infidelity, and given that such people may also be higher or lower in attachment insecurity, we controlled for whether or not people completed all waves of measurement and examined whether or not that variable moderated any key effects. As we report, this variable did not moderate any of the effects.

Measures

Infidelity

Two items assessed whether or not each individual perpetrated infidelity during the course of each study. The first asked participants to indicate whether or not they “had a romantic affair/infidelity” in the past 6 months. The second asked participants to indicate whether or not they “found out [their] partner had been unfaithful” in the past 6 months. Participants answered each question approximately every 6 months for the duration of each study. A total of 22 spouses and/or their partners reported an infidelity. Although this estimate is low compared to other estimates (Atkins et al. 2001; Greeley, 1994; Laumann et al., 1994; Wiederman, 1997), such other estimates tend to span longer than five years and were based on samples that include more-established marriages. Four of these infidelities were reported by both members of the couple, 7 were reported by the spouse who perpetrated the infidelity, and 11 were reported by the partner of the spouse who perpetrated the infidelity. The correlation between partners’ reports of infidelity was r = .35 (p < .01). This relatively low agreement may have emerged because (a) partners were not aware of an individual’s infidelity, (b) one member of the couple was more reluctant than the other to admit an infidelity, or (c) the items were worded differently for each partner (i.e., “infidelity” versus “unfaithful.”). Nevertheless given that our hypotheses addressed the probability of an individual’s own infidelity perpetration, not whether an infidelity occurred in the couple, and not the frequency of, change in, or the timing of infidelity, we created a variable from all of the assessments in an attempt to best indicate whether or not each individual perpetrated an infidelity. Specifically, each individual member of the couple was coded with a 1 if (a) that individual reported engaging in infidelity or (b) that individual’s partner reported that the individual was unfaithful, and a 0 otherwise.

Attachment insecurity

Attachment insecurity was assessed at baseline in both studies using the Experiences in Close Relationships scale (ECR; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998). The ECR is a continuous measure of attachment insecurity that identifies the extent to which a person is characterized by two dimensions: Attachment Anxiety and Attachment Avoidance. The Attachment Anxiety subscale is comprised of 18 statements that describe the degree of concern intimates have about losing or being unable to become sufficiently close to a partner and the Attachment Avoidance subscale is comprised of 18 statements that describe the extent to which partners attempt to maintain distance from a partner. Participants were asked to rate how much they agreed or disagreed with these statements on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = disagree strongly, 7 = agree strongly). Appropriate items were reversed and all items were averaged, with higher scores indicating greater attachment insecurity. Internal consistency was high in both studies (Study 1: α = .91 for husbands’ attachment anxiety, .92 for wives’ attachment anxiety, .92 for husbands’ attachment avoidance, and .94 for wives’ attachment avoidance; Study 2: α = .91 for husbands’ attachment anxiety, .90 for wives’ attachment anxiety, .91 for husbands’ attachment avoidance, and .88 for wives’ attachment avoidance).

Marital satisfaction

Global marital satisfaction was measured at each assessment in both studies using the Quality Marriage Index (QMI; Norton, 1983). The QMI contains six items that ask spouses to report the extent of their agreement with general statements about their marriage. Sample items include “we have a good marriage” and “my relationship with my partner makes me happy.” Five items ask participants to respond according to a 7-point scale, whereas one item asks participants to respond according to a 10-point scale. Thus, scores could range from 6 to 45, with higher scores reflecting greater marital satisfaction. Internal consistency was high for both studies (α was at least .85 for both husbands and wives at all assessments in both studies). The average of each spouse’s reports across all phases was controlled in the primary analyses.

Sexual frequency

Sexual frequency was assessed at each wave of data collection by asking both members of the couple to provide a numerical estimate of the number of times they had engaged in sexual intercourse with their marital partner over the past 6 months— the length of time since the previous assessment. Given that this item asked about the sexual frequency with one's partner, a couple-level variable, and given that the average of both partners' reports of the same behavior are likely to be a more valid estimate of that behavior than either partner’s self-reports alone, we used the average of both partners’ reports as a covariate in all analyses (correlations between husbands’ and wives’ reports ranged from .30 to .69 in Study 1 and .57 to .95 in Study 2). Results were not different if individual-level sexual frequency was used instead.

Big Five personality traits

Given our desire to control for other individual differences that may be associated with attachment insecurity and infidelity, and given that the five-factor model of personality theoretically captures all dispositional qualities of personality (Goldberg, 1993), we assessed these five dimensions (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism) at baseline using the Big Five Personality Inventory-Short (Goldberg et al., 2006). This measure requires individuals to report their agreement with 50 items (10 items per subscale) that assess each of the Big Five personality traits using a 5-point Likert-type response scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Internal consistency was high in both studies (Study 1: husbands’ α = .76 for openness, .77 for conscientiousness, .81 for extraversion, .61 for agreeableness, and .81 for neuroticism; wives’ α = .79 for openness, .71 for conscientiousness, .90 for extraversion, .72 for agreeableness, and .87 for neuroticism. Study 2: husbands’ α = .66 for openness, .74 for conscientiousness, .91 for extraversion, .74 for agreeableness, and .86 for neuroticism; wives’ α = .81 for openness, .73 for conscientiousness, .90 for extraversion, .67 for agreeableness, and .86 for neuroticism). Individuals’ own scores on each of these five subscales were controlled in all primary analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics and preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics for the independent variables for both studies are presented in Table 1. Spouses reported relatively high levels of satisfaction and sexual frequency across each study, on average. Also, husbands and wives reported being relatively securely attached, on average. Husbands and wives did not differ in their mean levels of attachment anxiety in either Study 1, t(71) = 0.87, p = .39, or Study 2, t(134) = .44, p = .66, but husbands reported significantly more attachment avoidance than did wives in both Study 1, t(71) = 2.14, p < .05, and Study 2, t(134) = 2.87, p < .01. The couples in Study 1 were less educated (for husbands, t(205) = 4.38, p < .01; for wives, t(204) = 3.63, p < .01) and earned less money annually, t(196) = 4.45, p < .01 than couples in Study 2. To control these and any other differences between participants and aspects of the two studies, we controlled for study in all primary analyses.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Independent Variables

| Husbands | Wives | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | N | M | SD | N | M | SD |

| Own attachment anxiety | ||||||

| Study 1 | 72 | 2.14 | 0.97 | 72 | 2.02 | 0.85 |

| Study 2 | 135 | 2.04 | 0.95 | 135 | 2.00 | 0.98 |

| Own attachment avoidance | ||||||

| Study 1 | 72 | 2.06 | 0.88 | 72 | 1.82 | 0.68 |

| Study 2 | 135 | 2.04 | 0.89 | 135 | 1.78 | 0.83 |

| Marital satisfaction | ||||||

| Study 1 | 72 | 40.49 | 4.66 | 72 | 40.34 | 4.30 |

| Study 2 | 135 | 40.55 | 4.00 | 135 | 40.53 | 4.71 |

| Sexual frequency | ||||||

| Study 1 | 70 | 36.94 | 27.65 | 70 | 42.16 | 30.74 |

| Study 2 | 133 | 53.96 | 48.31 | 134 | 52.90 | 39.24 |

| Neuroticism | ||||||

| Study 1 | 72 | 23.71 | 8.28 | 72 | 30.24 | 7.65 |

| Study 2 | 135 | 24.66 | 7.16 | 135 | 29.57 | 7.33 |

| Openness | ||||||

| Study 1 | 72 | 37.53 | 5.31 | 72 | 36.68 | 5.73 |

| Study 2 | 135 | 38.84 | 5.56 | 135 | 38.14 | 5.65 |

| Extraversion | ||||||

| Study 1 | 72 | 32.94 | 7.10 | 72 | 34.03 | 8.16 |

| Study 2 | 135 | 34.27 | 8.16 | 135 | 33.66 | 7.95 |

| Agreeableness | ||||||

| Study 1 | 72 | 37.68 | 5.10 | 72 | 43.40 | 4.78 |

| Study 2 | 135 | 37.81 | 5.98 | 135 | 42.50 | 4.96 |

| Conscientiousness | ||||||

| Study 1 | 72 | 34.76 | 5.58 | 72 | 36.78 | 6.55 |

| Study 2 | 135 | 35.35 | 6.48 | 135 | 36.38 | 6.68 |

Correlations between the variables are presented in Table 2. As can be seen, husbands' and wives' reports of attachment anxiety were positively associated with their reports of attachment avoidance and neuroticism and negatively associated with marital satisfaction, openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, and agreeableness. Husbands' reports of attachment avoidance were positively associated with neuroticism and negatively associated with marital satisfaction, openness, conscientiousness, extraversion and agreeableness. Wives' reports of attachment avoidance were positively associated with neuroticism and negatively associated with marital satisfaction, sexual frequency, extraversion, and agreeableness.

Table 2.

Correlations among Independent Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Attachment anxiety | .35** | .50** | −.25** | −.08 | −.17* | −.21** | −.16* | −.16* | .42** |

| 2. Attachment avoidance | .51** | .26** | −.29** | −.24** | −.09 | −.02 | −.22** | −.22** | .15* |

| 3. Marital satisfaction | −.17* | −.16* | .39** | .12 | .14 | .14* | .19** | .08 | −.15* |

| 4. Sexual frequency | −.06 | .03 | .19** | .76** | −.13 | −.13 | −.06 | −.09 | −.07 |

| 5. Openness | −.17* | −.13* | .14* | −.05 | .14* | .17* | .24** | .24** | −.18* |

| 6. Conscientiousness | −.32** | −.23** | .32** | .08 | .24** | .03 | .12 | .10 | −.22** |

| 7. Extraversion | −.15* | −.18* | −.00 | .03 | .21** | .09 | −.21** | .32** | −.11 |

| 8. Agreeableness | −.20** | −.26** | .04 | .03 | .35** | .16* | .42** | .06 | −.12 |

| 9. Neuroticism | .44** | .31** | −.21** | .04 | −.21** | −.25** | −.29** | −.34** | .02 |

Note. Correlations are presented above the diagonal for wives and below the diagonal for husbands; correlations between husbands and wives appear on the diagonal in bold.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Does own or partner attachment insecurity predict infidelity?

Given that we were examining the implications of both own and partner attachment insecurity for own perpetration of infidelity, and given that husbands and wives’ reports are not independent, we addressed our hypotheses using a 2-level actor–partner interdependence model (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006) using the Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) 6.08 computer program to account for the non-independence of husbands and wives’ data. In the first level of the model, we regressed our code of own infidelity (0 = no, 1 = yes) onto own Baseline reports of attachment anxiety, own Baseline reports of attachment avoidance, partner Baseline reports of attachment anxiety, partner Baseline reports of attachment avoidance, own Baseline reports of the Big Five personality traits, the average of own reports of marital satisfaction across all waves, participant sex, and a dummy-code for attrition (0 = completed all waves, 1 = did not complete all waves). Given that the average of each couple’s sexual frequency across all waves and a dummy code for study were couple-level variables, we entered both as controls on the level-2 intercept. Because our hypotheses addressed the implications of absolute-levels of attachment insecurity, rather than variations of attachment insecurity within each couple, all variables were grand-centered around the sample mean. The level-2 intercept was allowed to vary randomly across couples. Because the dependent variable was binary, we specified a Bernoulli outcome distribution.

Results of this analysis are presented in Table 3. As can be seen, consistent with expectations, but in contrast to previous research on dating couples (DeWall et al., 2011), own attachment anxiety was positively associated with own infidelity, indicating that partners with higher levels of attachment anxiety were more likely to engage in an infidelity. Specifically, people who scored one point higher than the mean on the attachment anxiety subscale were more than twice as likely to perpetrate infidelity as people who scored at the mean on the scale. A test of the Attachment Anxiety X Participant Sex interaction indicated this effect did not differ across husbands and wives, B = −0.08, SE = 0.47, t(393) = −0.18, p = .86; a test of the Attachment Anxiety X Study interaction indicated it did not differ across the two studies, B = −0.06, SE = 0.37, t(393) = −0.12, p = .87; and a test of the Attachment Anxiety X Attrition interaction indicated it did not differ across the attrition dummy-code, B = 0.34, SE = 0.42, t(393) = 0.82, p = .41. Also, this effect remained significant when partner attachment anxiety and avoidance were not controlled, B = 0.54, SE = 0.20, t(399) = 2.74, p < .01.

Table 3.

Effects of Own Attachment Anxiety, Own Attachment Avoidance, Partner Attachment Anxiety, and Partner Attachment Avoidance on Likelihood of Infidelity

| B | SE | t | p | Odds ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (0 = Study 1, 1 = Study 2) |

−0.89* | 0.38 | −2.33 | .02 | 0.41 |

| Attrition (0 = completed all waves, 1 = did not complete all waves) |

0.72 | 0.40 | 1.78 | .08 | 2.06 |

| Gender (0 = husband, 1 = wife) |

0.15 | 0.36 | 0.41 | .68 | 1.16 |

| Frequency of sex | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.56 | .58 | 1.00 |

| Marital satisfaction | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.78 | .44 | 1.02 |

| Neuroticism | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.37 | .71 | 0.99 |

| Openness | −0.07* | 0.03 | −2.34 | .02 | 0.93 |

| Extraversion | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.71 | .09 | 0.96 |

| Agreeableness | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.62 | .54 | 1.02 |

| Conscientiousness | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.70 | .48 | 0.98 |

| Own attachment anxiety | 0.74** | 0.22 | 3.34 | .00 | 2.10 |

| Own attachment avoidance | −0.15 | 0.25 | −0.57 | .57 | 0.86 |

| Partner attachment anxiety | 0.44* | 0.21 | 2.14 | .03 | 1.56 |

| Partner attachment avoidance | −0.80* | 0.32 | −2.51 | .01 | 0.45 |

Note.

= p < .05,

= p < .01.

In contrast to expectations, however, and also in contrast to what has been found in research on dating relationships (DeWall et al., 2011), own attachment avoidance was unrelated to own infidelity. This null effect did not differ across husbands and wives, B = −0.46, SE = 0.40, t(393) = −1.14, p = .25, the two studies, B = 0.62, SE = 0.44, t(393) = 1.40, p = .16, or the attrition dummy-code, B = 0.47, SE = 0.53, t(393) = 0.89, p = .37, and remained non-significant when partner attachment anxiety and avoidance were not controlled, B = 0.03, SE = 0.24, t(399) = 0.11, p = .91. Notably, low power cannot explain why attachment avoidance was not positively associated with own infidelity because the direction of the non-significant effect was negative.

Consistent with expectations, partner’s attachment anxiety was positively associated with own infidelity, indicating that individuals with partners who were high in attachment anxiety were more likely to engage in infidelity. Specifically, people who had partners who scored one point higher than the mean on the attachment anxiety subscale were more than one and a half times as likely to perpetrate infidelity as people who had partners that scored at the mean on the scale. This effect did not differ across husbands and wives, B = 0.19, SE = 0.58, t(393) = 0.33, p = .75, the two studies, B = −0.02, SE = 0.40, t(393) = −0.05, p = .96, or the attrition dummy-code, B = −0.48, SE = 0.60, t(393) = −0.80, p = .42.

In contrast to expectations, partner’s attachment avoidance was negatively associated with own infidelity, indicating that spouses with partners who were high in attachment avoidance were less likely to engage in infidelity. Specifically, people who had partners who scored one point higher than the mean on the attachment avoidance subscale were .45 times less likely to perpetrate infidelity as people who had partners that scored at the mean on the scale. This effect did not differ across husbands and wives, B = .57, SE = 0.76, t(393) = 0.75, p = .46 or the attrition dummy-code, B = −0.98, SE = 0.82, t(393) = −1.19, p = .24, but did differ across the two studies, B = −2.00, SE = 0.57, t(393) = −3.50, p < .01. Specifically, partner attachment avoidance was negatively associated with infidelity in Study 1, B = −2.26, SE = 0.44, t(393) = −5.09, p < .01, but not in Study 2, B = −.26, SE= 0.39, t(393) = −0.67, p = .50.

Do partners’ levels of attachment insecurity interact to predict infidelity?

To test whether partner attachment insecurity moderated either association between own insecurity and own infidelity, we estimated a new two-level model that regressed reports of own infidelity onto all covariates, mean-centered versions of all four attachment insecurity scores, and all four possible interactions (formed by multiplying together the mean-centered values of the variables involved in the interaction)—i.e., the Own Attachment Anxiety X Partner Attachment Anxiety interaction, the Own Attachment Anxiety X Partner Attachment Avoidance interaction, the Own Attachment Avoidance X Partner Attachment Anxiety interaction, and the Own Attachment Avoidance X Partner Attachment Avoidance interaction.

Results appear in Table 4, where the main effects and covariates are omitted to avoid redundancy with Table 3. As can be seen, only the Own Attachment Anxiety X Partner Attachment Anxiety interaction was significant. This interaction did not differ across husbands and wives, B = −0.20, SE = 0.31, t(385) = −0.66, p = .51, the two studies, B = −0.45, SE = 0.68, t(385) = −0.67, p = .51, or the attrition dummy-code, B = −0.66, SE = 0.57, t(385) = −1.15, p = .25.

Table 4.

Interactive Effects of Own Attachment Anxiety, Own Attachment Avoidance, Partner Attachment Anxiety, and Partner Attachment Avoidance on Likelihood of Infidelity

| B | SE | t | p | Odds ratio |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Own attachment anxiety X Partner attachment anxiety | −.95** | 0.25 | −3.77 | .00 | 0.38 |

| Own attachment anxiety X Partner attachment avoidance | .16 | 0.19 | 0.88 | .38 | 1.18 |

| Own attachment avoidance X Partner attachment anxiety | −.13 | 0.13 | −0.96 | .34 | 0.88 |

| Own attachment avoidance X Partner attachment avoidance | .10 | 0.31 | 0.33 | .74 | 1.11 |

Note.

= p < .01.

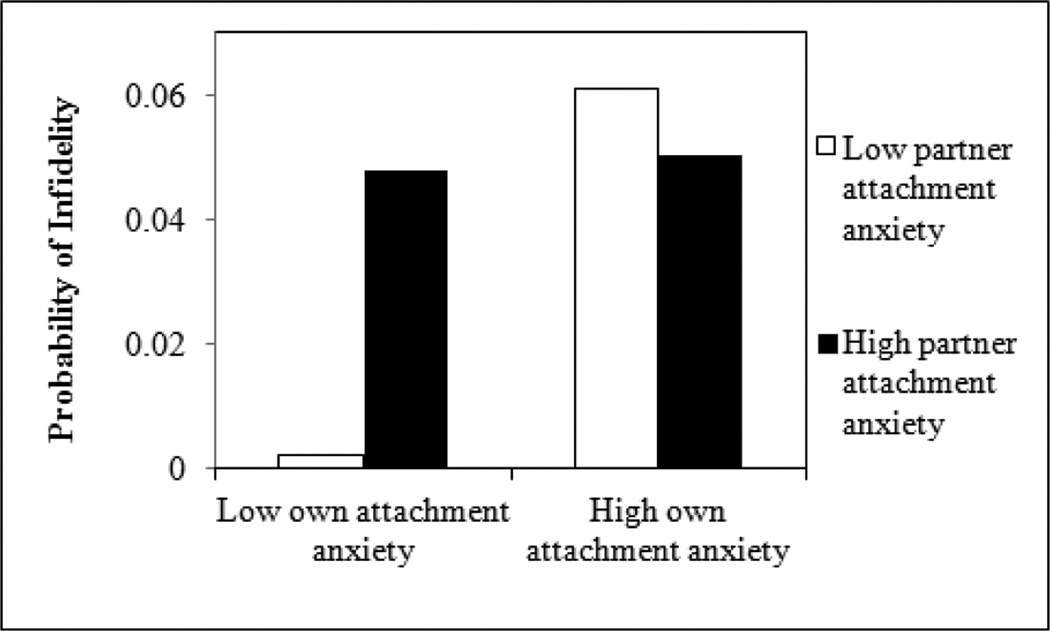

To view the nature of the interaction, we plotted the likelihood of own infidelity for spouses and partners one standard deviation above and below the mean on attachment anxiety. As can be seen in Figure 1, the only combination of partners that did not appear to have an increased probability of infidelity was the one in which relatively less anxious spouses where married to relatively less anxious partners. Indeed, simple slopes analyses confirmed that own attachment anxiety was positively associated with infidelity even when partners were relatively low in attachment anxiety, B = 1.83, SE = 0.36, t(393) = 5.05, p < .01, and partner attachment anxiety was positively associated with infidelity even when spouses were relatively low in attachment anxiety, B = 1.69, SE = 0.34, t(393) = 4.93, p < .01. This interaction qualifies the main effect of own attachment anxiety described earlier by indicating that low levels of own anxiety are only associated with a lower probability of infidelity for people whose partners are also lower in attachment anxiety.

Figure 1.

Interactive Effect of Own Attachment Anxiety and Partner Attachment Anxiety on Likelihood of Infidelity.

Discussion

Rationale and Summary of Results

Prior research addressing the association between attachment insecurity and infidelity has (a) tended to examine people in dating relationships and (b) ignored the role of partner attachment insecurity. The two studies described here examined the implications of own and partner attachment insecurity for infidelity in two samples of married couples and the results differed from the results obtained in prior research on dating individuals in two important ways. First, whereas prior research suggests avoidantly-attached individuals in dating relationships are more likely to engage in infidelity (DeWall et al., 2011), avoidant attachment was unrelated to infidelity in these studies of marriage. The fact that this effect was not significantly positive cannot be explained by lack of power because the direction of the non-significant effect was negative. Second, whereas prior research suggests that anxious attachment is unrelated to infidelity in dating relationships (e.g., DeWall et al., 2011), anxiously attached individuals were more likely to engage in infidelity in these marriages. Further, a significant Own Attachment Anxiety X Partner Attachment Anxiety interaction qualified this main effect, indicating that either partner being high in attachment anxiety appears to be sufficient to increase the odds of infidelity. Finally, intimates with avoidantly-attached partners were less likely to engage in infidelity in Study 1 regardless of own insecurity. None of these effects differed across men and women, and only the effect of partner avoidance differed across the two studies.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

These findings have important theoretical and practical implications. Regarding theory, they provide a more complete picture of the role of attachment anxiety in predicting marital infidelity. For example, consistent with dyadic models of personality (Shoda et al., 2002; Zayas et al., 2002), these findings demonstrate that the implications of one’s own attachment anxiety for infidelity appear to depend on the partner’s level of attachment anxiety, such that attachment anxiety in either member of the couple increases the likelihood that either spouse will perpetrate an infidelity. It may be that both own and partner attachment anxiety predict infidelity for the same reason, e.g., perhaps anxiety in either partner simply provides enough of a threat to intimacy to motivate spouses to seek out alternative partners. Alternatively, own and partner attachment anxiety may lead to infidelity for different reasons. Future research may benefit by identifying the mechanisms responsible for this interactive association.

Additionally, these findings raise important questions regarding the role of attachment avoidance in predicting marital infidelity. In contrast to research on dating couples in which own attachment avoidance was positively associated with infidelity, own attachment avoidance was unassociated with infidelity in these two studies of marriage. Further, partner attachment avoidance was negatively associated with infidelity in Study 1. Given that both findings were unexpected, and given that the negative association between partner attachment and infidelity did not replicate in Study 2, future research may benefit by attempting to replicate and explain both associations. In line with recent research by Lemay and Dudley (2011), partner avoidant attachment may be negatively associated with infidelity because spouses with an avoidantly-attached partner may be particularly careful not to disrupt their relationships.

Finally, these findings suggest that it may be important to study married spouses, rather than dating partners, to best understand the implications of various psychological traits and processes for marital relationships. As noted previously, one important difference between dating and marital relationships is that married individuals demonstrate higher levels of commitment, and existing research demonstrates that commitment moderates the associations between interpersonal processes (Amodio & Showers, 2005; Frye, McNulty, & Karney, 2008; Miller & Maner, 2010). For example, Miller and Maner (2010) reported that whereas cues to a woman’s fertility were positively associated with ratings of her attractiveness among relatively uncommitted men, those same cues were negatively associated with attractiveness among relatively committed men. Commitment may similarly moderate the effects of attachment insecurity on infidelity. Indeed, whereas DeWall and colleagues (2011) demonstrated that people in dating relationships, who tend to be less committed on average, perpetrate infidelities to avoid intimacy, Allen and Baucom (2004) demonstrated that married individuals, who tend to be more committed on average, perpetrate infidelities to increase intimacy. Accordingly, it makes sense that infidelity in a dating relationship is more likely among those high in attachment avoidance whereas infidelity in marital relationships is more likely among those high in attachment anxiety. In other words, not only may commitment mediate the effects of attachment insecurity on infidelity, as demonstrated by DeWall and colleagues (2011), commitment may moderate the effects of attachment on infidelity.

Regarding practice, the current findings suggest several avenues for improving the effectiveness of interventions to reduce infidelity. First, these results highlight the potential benefits of assuaging intimates’ attachment-related concerns. Indeed, interventions such as attachment-based family therapy (Shpigel, Diamond, & Diamond, 2012) and attachment-focused group intervention (Kilmann et al., 1999) have been effective at reducing attachment anxiety and thus may help prevent infidelity among anxiously-attached intimates. Second, given that partners’ attachment insecurity was associated with engagement in infidelity, practitioners may benefit from teaching their clients to be responsive to their partner’s attachment-related concerns. Indeed, intimates report reduced attachment insecurity when they are with responsive partners than when they are with unresponsive partners (e.g., Whiffen, 2005; see also Little, McNulty, & Russell, 2010) and thus being responsive may help prevent infidelity in these relationships.

Strengths, Limitations, and Directions for Future Research

Our confidence in these results is enhanced by several strengths of the research. First, with the exception of the negative association between partner attachment avoidance and infidelity, the effects reported here did not differ across two independent studies, providing confidence that they were not spurious due to the low number of infidelities in each study. Second, whereas other studies have collapsed across married and dating individuals (e.g., Allen & Baucom, 2004; DeWall et al., 2011), potentially obscuring the different implications of attachment infidelity in each type of relationship, our samples consisted of only married couples. Third, helping to minimize the problems associated with retrospective reports, both studies used a prospective design in which spouses first reported on attachment and then reported on the perpetration of infidelity. Finally, both studies controlled for several potential confounds— the frequency of sexual intercourse in the marriage, marital satisfaction, and personality.

Nevertheless, several factors limit the interpretations and generalizations of these results until they can be replicated and extended in future research. First, although these studies were longitudinal and controlled several individual difference variables, the results are nevertheless correlational and thus causal conclusions should be drawn with caution. Second, given that our samples consisted of newlywed couples married less than five years, caution should be used when generalizing these findings to lengthier marriages. Given the effects of attachment insecurity on infidelity appear to differ across married and unmarried people, future research may benefit from examining whether they also differ across couples in marriages of different lengths as well. Third, the definition of infidelity was open to participants’ interpretation and the items assessing infidelity were worded differently for own compared to partner reports of infidelity. As such, our measure of infidelity may have added error variance that limited our ability to detect some effects, such as any effects of own avoidant attachment. Fourth, although the samples were diverse in some important ways (e.g., education obtained, income), they were homogenous in other regards (e.g., age, ethnicity, religion). Ethnicity, in particular, may play an important role given that previous findings indicate that African Americans and Hispanic Americans report greater marital infidelity (e.g., Allen et al., 2005; Amato & Rogers, 1997; Greeley, 1994). Future research may benefit by examining whether ethnicity, or any differences associated with it, moderates the results that emerged here.

Conclusion

Prior research on unmarried couples demonstrates that own attachment anxiety is unassociated with infidelity whereas own attachment avoidance is positively associated with infidelity. Consistent with the idea that certain processes may differ across more versus less committed relationships, these two studies of married couples, in contrast, indicate that own and partner attachment anxiety interact to positively predict marital infidelity, whereas own attachment avoidance is unrelated to marital infidelity. Researchers should be cautious in assuming that samples of dating couples inform our theoretical understanding of marriage and vice versa.

Acknowledgments

Preparation for this article was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-I246794 awarded to V. Michelle Russell and the National Institute of Child Health and Development Grant RHD058314 awarded to James K. McNulty.

References

- Allen ES, Atkins DC, Baucom DH, Snyder DK, Gordon KC, Glass SP. Intrapersonal, interpersonal, and contextual factors in engaging in and responding to extramarital involvement. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005;12:101–130. [Google Scholar]

- Allen ES, Baucom DH. Adult attachment and patterns of extradyadic involvement. Family Process. 2004;43:467–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Rogers SJ. A longitudinal study of marital problems and subsequent divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59:612–624. [Google Scholar]

- Amodio DM, Showers CJ. “Similarity breeds liking” revisited: The moderating role of commitment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2005;22:817–836. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Baucom DH, Jacobson NS. Understanding infidelity: Correlates in a national random sample. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:735–749. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barta WD, Kiene SM. Motivations for infidelity in heterosexual dating couples: The role of gender, personality differences, and sociosexual orientation. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2005;22:339–360. [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Jouriles EN, O’Leary DK. Extramarital sex: Impact on depression and commitment in couples seeking marital therapy. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 1985;11:99–108. doi: 10.1080/00926238508406075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betzig L. Causes of conjugal dissolution: A cross-cultural study. Current Anthropology. 1989;30:654–676. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum GE, Reis HT, Mikulincer M, Gillath O, Orpaz A. When sex is more than just sex: Attachment orientations, sexual experience, and relationship quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:929–943. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogaert AF, Sadava S. Adult attachment and sexual behavior. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Shaver PR. Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York: Guilford; 1998. pp. 394–428. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Simpson JA, Kashy DA, Rholes WS. Attachment orientations, dependence, and behavior in a stressful situation: An application of the actor-partner interdependence model. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2001;18:821–843. [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, O’Leary KD. Infidelity and separations precipitate major depressive episodes and symptoms of nonspecific depression and anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:774–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWall CN, Lambert NM, Slotter EB, Pond RS, Deckman T, Finkel EJ, Luchies LB, Fincham FD. So far away from one’s partner, yet so close to romantic alternatives: Avoidant attachment, interest in alternatives, and infidelity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101:1302–1316. doi: 10.1037/a0025497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drigotas S, Safstrom C, Gentilia T. An investment model prediction of dating infidelity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:509–524. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney JA, Noller P. Attachment styles as a predictor of adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:281–291. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney JA, Noller P, Callan VJ. Attachment style, communication and satisfaction in the early years of marriage. In: Bartholomew K, Perlman D, editors. Advances in personal relationships: Vol. 5. Attachment processes in adulthood. London: Jessica Kingsley; 1994. pp. 269–308. [Google Scholar]

- Frye NE, McNulty JK, Karney BR. When are How do constraints on leaving a marriage related to negative behavior within the marriage affect behavior within the marriage? Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:153–161. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentzler AL, Kerns KA. Associations between insecure attachment and sexual experiences. Personal Relationships. 2004;11:249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Glass SP, Wright TL. Sex differences in type of extramarital involvement and marital dissatisfaction. Sex Roles. 1985;12:1101–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist. 1993;48:26–34. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR, Johnson JA, Eber HW, Hogan R, Ashton MC, Cloninger CR, Gough HC. The International Personality Item Pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Greeley A. Marital infidelity. Society. 1994;31:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Zeifman D, Middleton K. Adult romantic attachment, affection, and sex. Paper presented at the 7th International Conference on Personal Relationships; Groningen, Netherlands. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DJ, Rusbult CE. Resisting temptation: Devaluation of alternative partners as a means of maintaining commitment in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:967–980. [Google Scholar]

- Kane HS, Jaremka LM, Guichard AC, Ford MB, Collins NL, Feeney BC. Feeling supported and feeling satisfied: How one partner’s attachment style predicts the other partner’s relationship experiences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24:535–555. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kilmann PR, Laughlin JE, Carranza LV, Downer JT, Major S, Parnell MM. Effects of an attachment-focused group preventive intervention on insecure women. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 1999;3:138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Klohnen EC, Bera S. Behavioral and experiential patterns of avoidantly and securely attached women across adulthood: A 31-year longitudinal perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:211–223. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.1.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S. The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lemay EP, Dudley KL. Caution: Fragile! Regulating the interpersonal security of chronically insecure partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100:681–702. doi: 10.1037/a0021655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little KC, McNulty JK, Russell VM. Sex buffers intimates against the negative implications of attachment insecurity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:484–498. doi: 10.1177/0146167209352494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. A theory of marital sexual life. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:363–374. [Google Scholar]

- Lydon JE, Meana M, Sepinwall D, Richards N, Mayman S. The commitment calibration hypothesis: When do people devalue attractive alternatives? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25:152–161. [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson KD, Kessler RC, Shaver PR. Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:1092–1106. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. New York: Academic Press; 2003. pp. 53–152. [Google Scholar]

- Miller SL, Maner JK. Evolution and relationship maintenance: Fertility cues lead committed men to devalue relationship alternative. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;46:1081–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Norton R. Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1983;45:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Orzeck T, Lung E. Big-five personality differences of cheaters and non-cheaters. Current Psychology: Developmental, Learning, Personality, Social. 2005;24:274–286. [Google Scholar]

- Pistole CM. Attachment relationships: Self-disclosure and trust. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 1993;15:94–106. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE. Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1980;16:172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Olsen N, Davis JL, Hannon P. Commitment and relationship maintenance mechanisms. In: Harvey JH, Wenzel A, editors. Close romantic relationships: Maintenance and enhancement. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 87–113. [Google Scholar]

- Sănchez Sosa JJ, Hernández Guzmán L, Romero ML. Psychosocial predictors of marital breakup: An exploratory study in Mexican couples and former couples. Archivos Hispanoamericanos de Sexologia. 1997;3:125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt D. The big-five related to risky sexual behavior across 10 world regions: Differential personality associations of sexual promiscuity and relationship infidelity. European Journal of Personality. 2004;18:301–319. [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford TK. Self-esteem in marriage. e: An evolutionary psychological analysis. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:371–390. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Brennan KA. Attachment styles and the “big five” personality traits: Their connections with each other and with romantic relationship outcomes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18:536–545. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Mikulincer M. The role of attachment security in adolescent and adult close relationships. In: Simpson JA, Campbell L, editors. Oxford handbook of close relationships. New York: Oxford University Press; (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Shoda Y, Tiernan SL, Mischel W. Personality as a dynamical system: Emergence of stability and distinctiveness from intra- and interpersonal interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6:316–325. [Google Scholar]

- Shpigel MS, Diamond GM, Diamond GS. Changes in parenting behaviors, attachment, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation in attachment-based family therapy for depressive and suicidal adolescents. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2012;38:271–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2012.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA. Influence of attachment styles on romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:971–980. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Nelligan JS. Support seeking and support giving within couples in an anxiety-provoking situation: The role of attachment styles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:434–446. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW. Attitudes toward sexual permissiveness: Trends, correlates, and behavioral connections. In: Rossi AS, editor. Sexuality across the life course. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1994. pp. 63–97. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB, Margolis RL. Marital separation and extramarital sexual behavior. The Journal of Sex Research. 1983;19:23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Assessing commitment in personal relationships. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54:595–608. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AP. Extramarital sex: A review of the research literature. Journal of Sex Research. 1983;19:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Whiffen VE. The role of partner characteristics in attachment insecurity and depressive symptoms. Personal Relationships. 2005;12:407–423. [Google Scholar]

- Wiederman MW. Extramarital sex: Prevalence and correlates in a national survey. Journal of Sex Research. 1997;34:167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JD, Lederer DA. Differential antecedents of infidelity in marriage. American Mental Health Counselors Association Journal. 1984;6:152–161. [Google Scholar]

- Zayas V, Shoda Y, Ayduk ON. Personality in context: An interpersonal systems perspective. Journal of Personality. 2002;70:851–900. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.05026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]